VETERANS’ COMMUNITY CARE

VA Needs Improved Oversight of Behavioral Health Medical Records and Provider Training

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

VA Needs Improved Oversight of Behavioral Health Medical Records and Provider Training

Highlights of GAO-25-106910, a report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact Sharon M. Silas at silass@gao.gov.

Why This Matters

Increasingly, veterans seeking health care have been referred by Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers to community providers outside VA. The quality of the care those veterans receive can be affected by how successfully community and VA providers exchange medical records, as well as community providers’ ability to understand the unique needs of veterans.

GAO Key Takeaways

Veterans used over 350,000 referrals to receive behavioral health services (e.g., psychotherapy for depression) from community providers in fiscal years 2021 through 2023. Many veterans who were cared for by community providers later returned to VA medical centers for further care. To coordinate this care, community providers must send medical documentation (e.g., diagnoses, prescriptions, progress notes) to VA after the veteran’s initial and final visits for each referral.

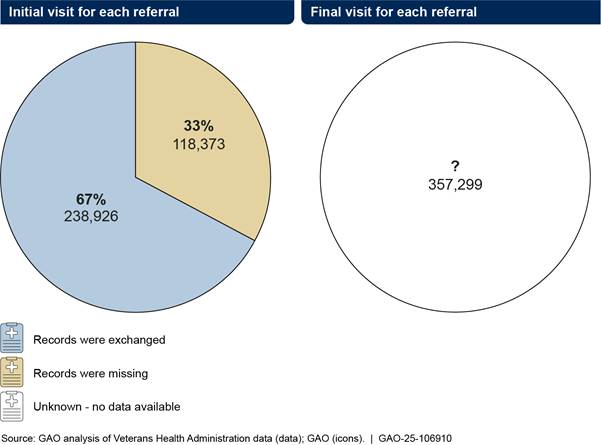

VA does not monitor whether these medical record exchanges are completed across all medical centers. But we found that 33 percent of these referrals were missing records for initial visits, when we reviewed the data that VA has readily available. Further, no such data are available for final visits, so the extent to which those exchanges are completed is unknown.

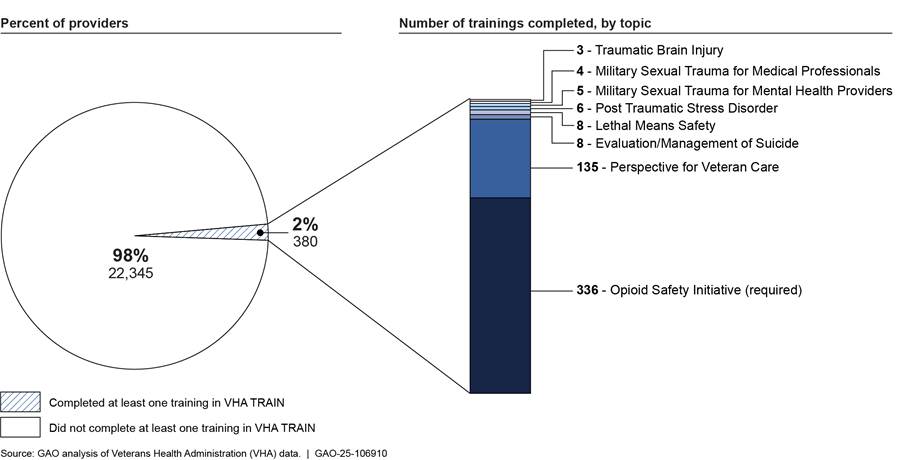

Likewise, VA is not monitoring the extent to which community providers complete any of eight core trainings on opioid safety, suicide prevention, and other veteran-centric topics. We found that about 2 percent of the community providers with a behavioral health referral from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 had completed one or more of these trainings.

How GAO Did This Study

We analyzed VA data on its behavioral health referrals from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 and community providers’ completion of core trainings. We reviewed VA’s medical record exchange guidance, and interviewed VA officials, staff from five VA medical centers, and representatives from three veteran service organizations.

What GAO Recommends

We are making five recommendations to VA, including for it to establish goals and performance measures and monitor the extent to which medical documentation exchanges and core community provider trainings have been completed.

VA concurred with one recommendation and concurred in principle with the other four recommendations, as discussed in the report.

Abbreviations

|

IVC |

Integrated Veteran Care |

|

TRAIN |

Training Finder Real-time Affiliate Integrated Network |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

|

VHA |

Veterans Health Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 5, 2025

The Honorable Jerry Moran

Chairman

The Honorable Richard Blumenthal

Ranking Member

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Bost

Chairman

The Honorable Mark Takano

Ranking Member

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

House of Representatives

Providing access to high-quality health care for behavioral health conditions—both mental health and substance use disorders—is a top priority of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).[1] VA operates the nation’s largest health care system through its Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and serves about 9 million veterans annually. Eligible veterans have received care from private sector community providers through various programs since 1945. In June 2019, VA began implementing the most recent program—the Veterans Community Care Program, which expanded veterans’ eligibility to receive services from community providers. Such services include psychotherapy to treat conditions such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder and other behavioral health care.

According to VHA, in recent years an increasing number of veterans have received health care services under the community care program. For example, the number of veterans who received services under the program increased from about 1.1 million in 2014 to about 2.8 million in 2023. When receiving community care, veterans rely on VA medical center staff and community providers to coordinate and maintain continuity of care. To do this, VA requires providers at a VA medical center and in the community to exchange certain medical documentation so that all of a veteran’s providers have similar information about a veteran—such as their diagnoses, past and ongoing treatments, and progress. According to VHA officials, this coordination is especially important so that all of a veteran’s providers can be well positioned to make sound decisions about the veteran’s care, especially when a veteran receives care from a community provider and then returns to the VA medical center to continue receiving appropriate care from a VA provider. For example, a veteran may experience changes to their diagnoses or may have positive or negative experiences with certain treatments while under a community provider’s care, which can last months or longer. Having this information can help the veteran’s VA provider determine whether the veteran should continue treatment that appears to be going well or avoid duplicating a previously attempted treatment that was deemed ineffective.

However, VA’s Office of Inspector General reported in 2024 that VA providers have raised concerns that the inability with or delay in obtaining medical documentation from community providers contributes to inefficient patient care and can negatively affect patient outcomes.[2] For instance, if a veteran returns to the VA medical center for further care, but the community provider has not submitted information about attempted treatments and any notes about their effectiveness, this gap poses a disruption to the continuity of that veteran’s care and a risk to the veteran’s safety.

According to VHA, to help ensure these veterans receive high-quality care, community providers should demonstrate military cultural competency. VHA defines military cultural competency as the ability to understand and appreciate military culture and tailor clinical practices based on that understanding. According to VHA, by demonstrating military cultural competency and understanding the influence of military culture on health-related behaviors (e.g., how stigmas associated with certain conditions may affect whether veterans seek care, how to refrain from making general assumptions about military experience), community providers will be better positioned to treat veterans’ unique behavioral and physical health care needs resulting from past military service, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. As such, VHA has developed required and recommended trainings for community providers so that they may be knowledgeable about certain behavioral and physical health conditions that are more prevalent among veterans as compared to the general population.

The Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019 included a provision for us to examine VA’s efforts for integrating community based mental health care into the VHA, including coordination between VHA and community providers.[3] In this report we

1. describe what VA data show about behavioral health referrals to community care for veterans from fiscal years 2021 through 2023;

2. describe challenges affecting the medical documentation exchange processes and steps VHA is taking to mitigate those challenges;

3. evaluate the extent to which VHA provides guidance for and monitors medical documentation exchange for behavioral health referrals between VHA and community providers; and

4. evaluate the extent to which VHA monitors and communicates information about community providers’ completion of military cultural competency and other trainings.

To address the first objective, we analyzed systemwide data from VA’s Corporate Data Warehouse for all behavioral health referrals for those fiscal years.[4] We analyzed the data to determine the total number of behavioral health referrals made from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 (the most recent complete data available at the time of our review) and the number of veterans for whom referrals were made. We examined the data by categories of care (e.g., outpatient psychotherapy, outpatient psychiatry), and categories of diagnoses (e.g., anxiety and stress-related disorders, substance use disorders). We also examined the data by veteran socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., race, gender, geographic location) and active suicide or behavioral risk flag status.[5]

To address the second objective, we interviewed officials from VHA’s Office of Integrated Veteran Care (IVC), which administers the Veterans Community Care Program, and officials from other VHA program offices. We also interviewed representatives from VA’s two contractors who act as third-party administrators, responsible for maintaining regional networks of community providers under the Veterans Community Care Program. In addition, we conducted virtual site visits with five VA medical centers in April and May 2024, and spoke with facility leadership and community care staff and managers. We selected the sites based on geographic variation and the total number of behavioral health referrals made by each VA medical center provider to community providers from fiscal years 2021 through 2023, among other factors. We interviewed community care leaders from four of the five regional Veteran Integrated Service Networks in which those five VA medical centers are located.[6]

To address the third objective, we reviewed guidance that IVC provided to VA medical centers and other documentation from VHA (e.g., directives, memorandums) related to obtaining medical documentation from community providers. In addition, we interviewed staff at the five selected VA medical centers on their local processes and procedures related to collecting medical documentation from community providers. We evaluated IVC’s guidance and monitoring efforts against a VHA policy related to oversight responsibilities.[7] We also evaluated those oversights efforts against performance management steps identified in our prior work.[8] In addition, we evaluated IVC’s oversight efforts against federal internal control standards related to designing control activities.[9]

To address the fourth objective, we interviewed IVC officials and representatives from the third-party administrator contractors about their roles and responsibilities related to communicating information and monitoring community provider training. We also analyzed data from VHA’s Training Finder Real-time Affiliate Integrated Network (TRAIN). VHA TRAIN is a web-based platform where all community providers (including those that focus on delivering behavioral health services to veterans) can complete trainings. Specifically, we reviewed VHA TRAIN data to determine the number of community providers who had at least one behavioral health referral from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 (the most recent complete data at the time of our review) and had completed one or more of the eight core trainings that IVC requires or recommends for community providers.[10] In addition, for context, we interviewed representatives from three Veteran Service Organizations about the importance of community provider training completion from the veteran perspective.[11] We also interviewed 13 community providers from three external professional organizations to obtain information on their experiences participating in the Veterans Community Care Program and whether they were aware of and had completed core trainings.[12] We evaluated IVC’s communication and monitoring efforts against VHA policy, as well as performance management steps identified in our prior work.[13] We also evaluated IVC’s training outreach efforts against federal internal control standards related to communication information.[14]

See appendix I for more details on our scope and methodology.

To assess the reliability of data we used in all our analyses, we performed electronic testing to identify obvious errors or missing data. We also interviewed VHA officials knowledgeable about the data’s reliability and reviewed relevant documentation. Based on these steps, we determined that the data we used were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our audit objectives.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2023 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

VA’s Veterans Community Care Program

Eligible veterans can receive community care, including behavioral health and other services, through VA’s Veterans Community Care Program, which is overseen by IVC. Veterans may be eligible to receive such services for several reasons, including that the services are not available at a VA medical center.[15] Generally, before an eligible veteran can receive community care, the veteran’s provider at a VA medical center must first create a referral in the veteran’s electronic health record. Community care staff at the VA medical center then process the referral by sending it to a community provider, scheduling the veteran’s visit with the community care provider, confirming the visit took place, and closing the referral after such confirmation. The community provider and community care staff at the VA medical center are expected to further coordinate by exchanging medical documentation about the veteran and the care that has been delivered.

VHA’s Office of Integrated Veteran Care

As the principal office within VHA that oversees the Veterans Community Care Program (among other programs), IVC is responsible for ensuring veterans receive high-quality behavioral health care and other services from community providers. This oversight includes supporting care continuity, which is dependent on the exchange of veterans’ medical documentation between VA medical centers and community providers. Specifically, IVC is responsible for providing guidance to and monitoring the efforts of VA medical centers’ participating in the program. IVC also monitors the performance of the two third-party administrator contractors that maintain five regional community care networks of community providers. Specifically, two offices within IVC have key responsibilities overseeing the program:

· Office of Integrated External Networks. This IVC office is responsible for conducting oversight activities for the Veterans Community Care Program (among other programs), focusing on network adequacy, contract management, and performance. It is responsible for leading, developing, and administering IVC’s contracts with the two third-party administrator contractors.[16] The office is also responsible for monitoring, measuring, and reporting on performance to ensure providers deliver high-quality services for veterans.

· Office of Integrated Optimization. This IVC office collaborates with VA medical centers, Veterans Integrated Service Networks, and other VHA components to address challenges and opportunities for optimizing veterans’ access to health care within VA medical centers or through community care. It is responsible for developing and implementing access policies, processes, and improvements for direct and community care, including disseminating related guidance to VA medical centers.[17]

Medical Documentation Exchange

According to IVC officials, IVC’s Office of Integrated Optimization disseminates medical documentation exchange guidance to VA medical centers through its Community Care Field Guidebook (IVC Guidebook).[18] IVC’s Guidebook outlines processes, tools, and methods for medical documentation exchange between staff at VA medical centers and community providers, among other things. It identifies the types of information that community care staff at VA medical centers should include when sending referrals to community providers, such as the following:

· Authorized services and duration. Based on the veteran’s provisional diagnosis (as determined by a provider at the VA medical center), the referral should identify the associated category of care (e.g., outpatient individual psychotherapy, outpatient psychiatry, opioid treatment). It should also identify the various specific services (e.g., initial diagnostic evaluation, therapy sessions) and may include a recommended frequency of visits, that the community provider is authorized to deliver over a set duration of time not to exceed one year.[19] For example, a referral may identify outpatient individual psychotherapy as the category of care, authorizing services such as therapy sessions at a recommended frequency of one visit per week for a duration of 6 months.

· Suicide or behavioral health risk flags, if any. VA medical center staff should also ensure a suicide risk flag (indicating there is an acute suicide risk) or behavioral flag (indicating the veteran is considered a risk to others) is clearly visible in the veteran’s referral. The referral should also include contact information for designated staff at the VA medical center responsible for monitoring those risks for the veteran.[20]

Once behavioral health services for a veteran under a referral have been delivered by the community provider, community providers are required to submit medical documentation to the referring VA medical center that contains certain information, according to VA’s contracts with the two third-party administrator contractors. According to IVC officials, this is necessary to establish continuity of care—an important aspect of providing consistent and high-quality care. Specifically, for each referral, community providers are required to submit medical documentation, which should include the veteran’s and provider’s identifying information and, for outpatient referrals, clinical information such as diagnoses, treatment plans, medications prescribed, and progress notes. Community providers are required to submit this information at two specific points during the veteran’s outpatient care: (1) initial medical documentation within 30 days of the first visit, and (2) final medical documentation covering all additional visits within 30 days of the final visit.[21] Medical documentation for inpatient care is to be returned within 30 days and consist, at a minimum, of a discharge summary.

Community providers can submit medical documentation through a variety of methods, including VHA’s electronic HealthShare Referral Manager.[22] While VA does not require community providers to use the HealthShare Referral Manager, it is IVC’s preferred method for medical documentation exchange because it provides a secure platform for VA medical center staff and community providers to electronically share information with each other, which can reduce the time needed to process a referral. Other methods include secure email, electronic fax, traditional fax, or U.S. mail. Once VA medical center staff receive medical documentation from community providers, VA medical center staff are able to attach the documentation to the relevant referral in the patient’s electronic health record, which creates an alert to inform the ordering provider.

IVC Training for Community Providers

According to IVC officials, in September 2021, IVC identified eight core trainings for community providers to help them deliver high-quality care. According to VHA, these trainings are intended to provide insight on the unique experiences and exposures that veterans may encounter. IVC currently requires that all community providers complete one of the trainings—an opioid safety initiative training.[23] In addition, IVC recommends that all community providers complete seven trainings. These include trainings on military cultural competency, lethal means safety, suicide prevention, and other veteran-centric topics related to traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, and military sexual trauma. For additional information on the eight core trainings, see appendix II.

Almost 225,000 Veterans Used Behavioral Health Referrals from VA Medical Centers from Fiscal Years 2021 Through 2023, with Just Over Half for Psychotherapy Services

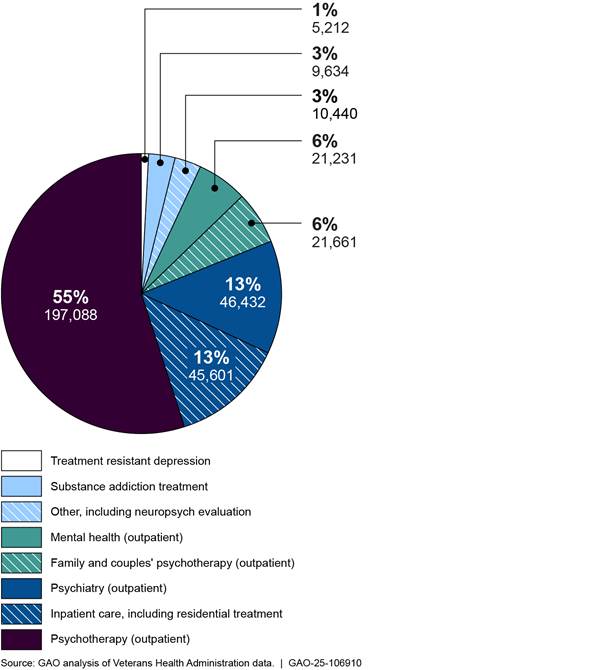

From fiscal years 2021 through 2023, 224,741 veterans used a total of 357,299 referrals to receive behavioral health services from community providers.[24] On average a veteran used 1.6 referrals during this period.[25] More than half of these 357,299 behavioral health referrals (about 55 percent) were for the outpatient psychotherapy care, which can include specific services such as counseling and therapy sessions. The remaining 45 percent of referrals were for care categories that include outpatient psychiatry, which can include services such as medication treatment; outpatient family and couples’ psychotherapy; and inpatient care, including mental health residential treatment; and other categories of care (see fig. 1). The 357,299 referrals resulted in about 4 million total visits to community providers over those 3 years.

Figure 1. Behavioral Health Care Referrals to Community Providers by Category of Care, Fiscal Years 2021 Through 2023

Notes: The data in this figure reflect the proportion of categories of care included in the 357,299 referrals (completed by 224,741 veterans). The referrals were made by Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) medical center staff to community providers from fiscal years 2021 through 2023. Each referral includes one category of care (e.g., outpatient individual psychotherapy) that indicates the specific services (e.g., counseling and therapy sessions) that the community provider is authorized to provide over a set duration of time (e.g., 6 or 12 months).

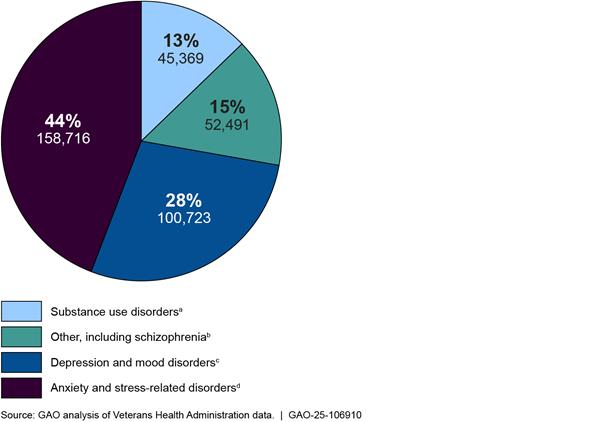

About 44 percent of the 357,299 behavioral health referrals to community providers were for veterans diagnosed with anxiety and stress-related disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder. The remaining 56 percent of referrals were for veterans with depression or mood disorders, other mental health disorders such as schizophrenia, and substance use disorders (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Behavioral Health Care Referrals to Community Providers by Diagnoses, Fiscal Years 2021 Through 2023

Notes: The data in this figure reflect the proportion of veterans’ diagnosis categories included in the 357,299 referrals (completed by 224,741 veterans). The referrals were made by staff at Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) medical centers to community providers from fiscal years 2021 through 2023. These categories are based on provisional diagnoses, as determined by the veterans’ providers at the VA medical center. According to the Veterans Health Administration’s Corporate Data Warehouse officials, community care providers also submit their diagnosis with claims paperwork, which is often (but not always) the same as the VA provider’s provisional diagnosis. The diagnosis categories are based on the individual conditions listed in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, which is a standardized system used to code diseases and reason for visits in all health care settings.

aThis category includes substance use disorders such as alcohol, opioid, or cocaine dependence (codes F10-F19).

bThis category includes all other diagnoses, such as schizophrenia, as well as relationship problems with a spouse or partner (codes Z63, F1-9, F50-99).

cThis category includes depression and mood disorders such as bipolar disorder (codes F30-F39).

dThis category includes anxiety and stress-related disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder and adjustment disorder (codes F40-F49).

As noted earlier, 224,741 individual veterans used behavioral health referrals to community providers from fiscal years 2021 through 2023. The majority of these veterans reside in urban areas (about 72 percent). In terms of demographics, most veterans were white (about 63 percent), non-Hispanic (about 80 percent), male (about 77 percent), and had an average age of 50 years.

A small proportion of veterans had an active suicide or behavioral risk flag at the time the VA medical center made a referral for the veteran to receive behavioral health services from a community provider.[26] Specifically, 8,094 (about 4 percent) of the 224,741 veterans who received behavioral health referrals from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 had an active suicide risk flag when the referral was made. Less than 1 percent of the 224,741 veterans had an active behavioral health flag at the time referral was made.

The majority of veterans who participated in the Veterans Community Care Program from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 maintained a connection with a VA medical center. About 71 percent (160,497) of the 224,741 veterans subsequently returned to a VA medical center for behavioral health services and about 90 percent of the veterans have a VA primary care provider.

VHA and Selected VA Medical Center Staff Reported Medical Documentation Exchange Is Labor Intensive and Time-Consuming; VHA and Staff Taking Steps to Mitigate

According to IVC officials, it is important for all health care professionals involved in a veteran’s care to have access to the same, comprehensive, and up to date medical information. However, IVC officials told us that obtaining medical documentation from community providers is a key challenge because current medical documentation exchange processes are labor intensive and time-consuming for both VA medical center staff and community providers. Specifically, IVC officials told us that VA medical center staff often have to make repeated attempts to try to obtain documentation from community providers and may not ultimately be successful in retrieving it despite making multiple attempts. Furthermore, IVC officials said VA medical center staff often have to search multiple places when community providers do submit medical documentation because community providers vary in their submission methods (e.g., electronic fax, HealthShare Referral Manager, email).

According to IVC officials, the labor intensive and time-consuming process of obtaining medical documentation from community providers can be especially challenging for community care programs at VA medical centers that have insufficient staffing. Community care staff we spoke with from four selected VA medical centers elaborated on how insufficient staffing can affect or delay the extent to which they are able to include medical documentation in veterans’ electronic health records. For example, community care staff from three of those VA medical centers said they are not always able to make attempts to retrieve medical documentation from community providers due to staff limitations or a high volume of referrals to community care. Community care staff from two VA medical centers we spoke with noted they generally prioritize scheduling appointments or confirming that veterans attended their initial appointments, over requesting medical documentation because they want to ensure that veterans receive the care they need as quickly as possible.

VA medical center staff we spoke with from three VA medical centers told us that the labor intensive and time-consuming process for medical documentation exchange can also be especially challenging for community providers’ practices that have limited staff or are experiencing other staffing issues. For example, staff said community providers that have small or individual practices with limited or no support staff may not be able to submit medical documentation as quickly as larger practices with administrative staff or answer phone calls from VA medical center staff requesting documentation, particularly while seeing patients.[27] Two community care providers we spoke with agreed that medical documentation exchange is time-consuming, noting that their staff spend a significant amount of time managing documentation exchange.

IVC officials and community care staff from some VA medical centers told us they are currently planning to or are in the process of working on multiple efforts to help alleviate the labor intensive and time-consuming process of medical documentation exchange. These efforts include the following:

· Increasing use of the HealthShare Referral Manager. IVC officials and VA medical center staff we spoke with said that they continue to encourage community providers to use the HealthShare Referral Manager to exchange medical documentation to help reduce the time spent on processing referrals and increase the efficiency of scheduling appointments and sending medical documentation. Medical center staff from four VA medical centers told us that while most community providers currently use electronic fax, they would prefer them to instead use the HealthShare Referral Manager because it keeps documentation in one place and prevents them from having to manage and track the use of multiple methods. Staff said they generally receive medical documentation more quickly from community providers who use it compared to those who do not, requiring less follow up by staff. (See text box.) As such, staff from two VA medical center told us they try to encourage community providers to use the HealthShare Referral Manager by explaining its benefits and offering training and assistance to community providers who are willing to sign up for it. Likewise, IVC officials told us they established a goal around 2021 to try to increase community providers’ usage of the HealthShare Referral Manager by 800 each month. Officials told us they exceeded that goal by adding an average of 1,922 community providers each month between January 31, 2024, and January 31, 2025 (based on a 12-month rolling average).

|

Use of HealthShare Referral Manager Among Community Providers In our prior work, we recommended that the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Veterans Health Administration (VHA) conduct a review of community provider enrollment and use of the HealthShare Referral Manager and if determined appropriate, establish a requirement for community providers to use it. VA agreed with our recommendation and provided updated numbers showing that it had increased the number of community providers using the HealthShare Referral Manager. However, IVC officials reported that they decided not to require community providers to use the HealthShare Referral Manager because some community providers prefer other methods and IVC does not want to limit the number of community providers participating in the Veterans Community Care Program. In the absence of a requirement, officials said they would continue to encourage community providers’ use through training and outreach efforts. |

Source: GAO, Veterans Community Care Program: Improvements Needed to Help Ensure Timely Access to Care, GAO‑20‑643 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 28, 2020). | GAO‑25‑106910

· Updating process to improve efficiency. IVC officials said they are exploring different approaches (such as standardizing processes and automation tools used for incorporating medical documentation from community providers into VHA’s electronic health record system) to make the overall process more efficient and capture data nationally that are currently not available.

· Educating providers. Representatives from the two third-party administrator contractors told us they educate community providers on their responsibility to submit medical documentation to VA medical center staff at the beginning and end of the veteran’s care. For example, these representatives said they include information about medical documentation requirements in provider handbooks and other outreach materials, and the contractors also provide reeducation efforts as needed. IVC officials told us that medical documentation return has been at the forefront of IVC’s planning for upcoming contracts and IVC intends to strengthen requirements related to medical documentation exchange with community providers, which may help alleviate some challenges VA medical center staff have in obtaining medical documentation, particularly for those community care programs with insufficient staff.

We will continue to monitor IVC and VA medical center efforts to help alleviate the labor intensive and time-consuming process of medical documentation exchange.

VHA Does Not Provide Guidance for Obtaining All Required Medical Documentation, and VHA Does Not Monitor Exchange; Referrals Have Significant Amount of Missing Documentation

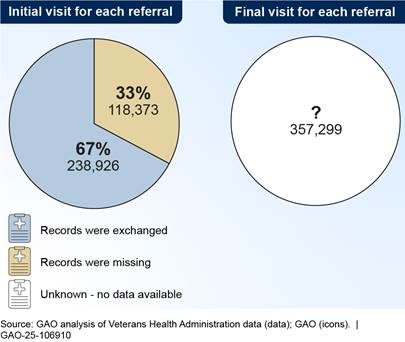

VHA’s IVC provides guidance to VA medical center staff instructing them to obtain initial medical documentation, which community providers are required to provide within 30 days of a veteran’s first visit. However, IVC does not provide similar guidance for obtaining final medical documentation, which providers are required to submit after delivering all services to a veteran for a referral. IVC officials told us that IVC does not monitor the extent to which medical documentation from community providers is available or missing across VA medical centers. We found that missing documentation is prevalent. About a third of all behavioral health referrals from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 were missing initial medical documentation and no data were available for final documentation.

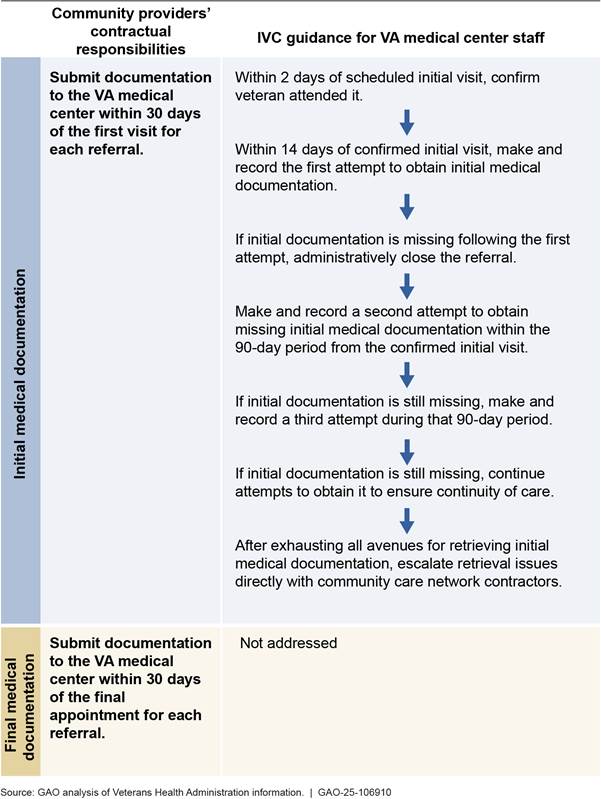

VHA’s IVC Provides Guidance for VA Medical Centers for Obtaining Initial, but Not Final, Medical Documentation Exchange with Community Providers for Behavioral Health Referrals

According to IVC’s Guidebook, community care staff at VA medical centers should make every effort to work with community providers to ensure staff receive medical documentation and upload it into veterans’ health records. As previously described, community providers are required to submit initial medical documentation within 30 days of a veteran’s first visit, and final medical documentation covering all additional visits within 30 days of a veteran’s final visit. IVC’s Guidebook states that in some cases, community providers will automatically send medical documentation to VA medical center staff after a visit has occurred. The Guidebook notes that while this practice is ideal, community care staff will generally need to contact community providers to obtain the information.

For cases in which the community provider does not automatically send medical documentation to VA medical center staff following an initial visit, IVC’s Guidebook and a 2021 VHA memorandum describe the process that VA medical center staff should follow up to try to obtain it.[28] The process includes several steps, including VA medical center staff making and documenting at least three attempts to obtain medical documentation in VHA’s consult toolbox, which is the software that aids VA community care staff in managing community care referrals (see fig.3). In addition, community care staff should “administratively close” the referral in VHA’s consult toolbox if the first attempt to obtain initial medical documentation was unsuccessful. Administratively closing a referral indicates that the veteran attended the initial visit but additional attempts to obtain initial medical documentation are needed. According to the Guidebook, administratively closing referrals does not release VA medical center staff from their obligation to continue to try to obtain medical documentation, which is still needed to ensure continuity of care.[29] IVC officials told us that community care managers should use an administrative closure report to keep track of all administratively closed referrals for 90 days to help enable them to ensure that community care staff make additional attempts to obtain veterans’ initial medical documentation.

While IVC has established guidance for tracking initial medical documentation, IVC officials said it has not developed guidance instructing VA medical facility staff to also obtain final medical documentation and describing the process they should use to do so. As discussed earlier, final medical documentation should include important information (e.g., diagnoses, treatment plans, medications prescribed, progress notes) that covers all of a veteran’s visits with a community provider for behavioral health services authorized by a referral.

Figure 3: Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) Office of Integrated Veteran Care (IVC) Guidance for VA Medical Centers to Obtain Medical Documentation from Community Providers

Note: In April 2025, VA officials told us that VA is in the process of updating the guidance outlined in this figure.

According to IVC officials, IVC developed guidance for tracking initial medical documentation, in part, because the process is easier to implement and oversee compared to a process for tracking final medical documentation exchange. IVC officials noted that staffing resources in community care offices are limited, so IVC decided to focus on guidance for obtaining initial medical documentation, which contains important information that should be captured in veterans’ records such as recommendations on further testing or follow-up care.

Nevertheless, IVC officials acknowledged there is a gap in the guidance and that obtaining final medical documentation is important. They stated that having both initial and final medical documentation is necessary for ensuring continuity of care for veterans, which, in turn, is necessary for ensuring consistent and high-quality care. However, IVC officials said it is more challenging for VA medical center staff to obtain final medical documentation because referrals vary in duration of time and the number of visits authorized and staff may not be able to easily determine when the final visit occurred for each referral. However, given that each referral includes a start and end date, and authorized services cannot exceed one year, an inability to determine the specific date the final visit occurred does not preclude VA medical center staff from using the authorized end date for each referral, which is readily available, or another appropriate marker.

IVC’s lack of guidance for VA medical centers to track final medical documentation exchange does not align with IVC’s responsibilities as outlined in VHA policy. According to a VHA directive, principal offices (such as IVC) are responsible for providing oversight to their national programs (such as the Veterans Community Care Program), which includes providing guidance.[30] Further, federal standards for internal controls state that management should design control activities that support the achievement of objectives and address related risks.[31] Given IVC’s mission includes providing veterans access to high-quality behavioral health and other services from community providers, and the risks that missing final medical documentation can pose to veterans’ continuity of care, the lack of guidance for VA medical centers to obtain such documentation is inconsistent with these standards. In addition, according to IVC officials, disseminating guidance (including IVC’s Guidebook) to VA medical centers is a responsibility of IVC’s Office of Integrated Optimization.

Establishing guidance instructing VA staff to obtain final documentation from community providers and describing how they should do it will help ensure that the requirement is met and thereby help ensure continuity of care. While community care staff and managers we spoke with said that they generally try to make the required attempts to obtain initial medical documentation, they told us that they do not attempt to obtain final medical documentation because IVC has not provided guidance for them to do so. As discussed earlier, obtaining final medical documentation is important for veterans’ continuity of care, as this documentation may include important details for veterans returning to the VA medical center for care, such as medications prescribed. It can also comprise a significant portion of the overall medical documentation as compared to the initial documentation that would cover just the initial visit. For example, some referrals for behavioral health services related to the outpatient individual psychotherapy care category cover the number of visits the community provider deems clinically necessary over a 6 or 12-month period, which can result in several dozen visits. Among the 357,299 behavioral health referrals from fiscal years 2021 through 2023, about 76 percent of referrals authorized services over a period of either 6 or 12 months and accounted for about 85 percent of visits.

VHA’s IVC Does Not Monitor Whether Required Documentation Has Been Obtained; GAO Found Prevalent Documentation Gaps

IVC officials told us that IVC does not monitor the extent to which VA medical facilities have obtained initial or final medical documentation related to behavioral health referrals. In lieu of such monitoring, IVC relies on the success of various efforts to support medical documentation exchange. For example, IVC officials told us that IVC relies on VA medical centers to track medical documentation exchange for each veteran, and IVC’s role is limited to providing related guidance. Specifically, IVC officials said that IVC relies on VA medical center staff to follow its guidance for attempting to obtain veterans’ initial medical documentation from community providers for each behavioral health referral and for recording their attempts.

Additionally, as discussed earlier, IVC relies on the third-party administrator contractors to educate community providers on the providers’ responsibility to submit medical documentation after the initial and final visits to ensure providers’ awareness of this requirement. Representatives from the two third-party administrator contractors told us they provide education through their handbooks and other outreach materials in addition to making direct contact with providers for reeducation about medical documentation requirements.[32] IVC officials and community care staff from some VA medical centers told us that IVC also relies on other efforts such as increasing providers’ use of the HealthShare Referral Manager to help obtain medical documentation from community providers.

However, IVC officials said that IVC does not monitor medical documentation exchange systemwide. Specifically, IVC does not use relevant and readily available data in VA’s Corporate Data Warehouse—generated from VA medical centers’ tracking of initial medical documentation exchange—to monitor the extent to which such documentation has been obtained or is missing across all VA medical centers. These data include a range of information for each referral. For example, the data includes the date a referral was made, dates when staff attempted to obtain initial medical documentation, and the date when the community provider submitted initial medical documentation.[33]

Our analysis of data from VA’s Corporate Data Warehouse on all 357,299 behavioral health referrals from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 indicates that missing initial medical documentation is prevalent. Specifically, about 33 percent (118,373 of 357,299) of these referrals were missing initial medical documentation. Among the 118,373 referrals missing documentation around 80 percent (95,197) were for referrals authorizing 6 or 12 months of care. Further, we could not similarly analyze data for missing final medical documentation because such data (e.g., date of final visit, dates when staff attempted to obtain final medical documentation) do not exist because IVC does not provide guidance for VA medical centers to collect it. As such, IVC cannot assess the extent to which final medical documentation is available or missing systemwide.

IVC officials said they are aware of challenges with documentation exchange and identified specific VA data fields we could use to assess the extent to which initial documentation was missing. However, IVC was not aware of the extent of missing initial documentation for behavioral health referrals because IVC had not conducted similar analyses. Figure 4 depicts the percentages of referrals with available or missing data based on our analysis.

Figure 4: Percentage of Behavioral Health Referrals to Community Providers That Veterans Used from Fiscal Years 2021 Through 2023 with Available or Missing Medical Documentation

Note: The data in this figure reflect 357,299 referrals that Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) medical center staff made to community providers and that veterans used to receive behavioral health services from fiscal years 2021 through 2023.

IVC does not monitor whether required initial and final medical documentation is obtained by VA medical centers across the system because it has not taken key performance management steps that would necessitate monitoring. Specifically, while IVC officials told us that IVC has prioritized ensuring network adequacy and other access to care issues, IVC has not prioritized monitoring medical documentation exchange. For instance, IVC has not established a goal for VA medical center staff to obtain veterans’ medical documentation from community providers after both initial visits and after a community care referral has been completed. In addition, IVC has not established related performance measures or benchmarks that would enable it to monitor progress toward such a goal—e.g., obtaining initial and final medical documentation from community providers for a certain proportion of referrals over a given time period.

IVC’s lack of monitoring is also inconsistent with key performance management steps described in our prior work. We have reported on the importance for federal programs to take key performance management steps that include establishing goals and performance measures and using related information to assess progress toward goals and inform decisions.[34] In this case, such steps would include IVC monitoring medical documentation exchange by setting related goals and performance measures and then using such information to inform programmatic decision-making, such as where to target improvement efforts.

Further, such monitoring would be consistent with the responsibilities outlined in VHA policy and IVC governance documentation. Specifically, according to a VHA directive, principal offices (such as IVC) are responsible for overseeing their national programs (such as the Veterans Community Care Program). VA’s Functional Organizational Manual indicates that IVC’s Office of Integrated External Networks is responsible for program oversight, with a focus on performance. This includes monitoring, measuring, and reporting on performance to ensure high-quality care for all veterans. IVC officials confirmed this office is responsible for overseeing performance through monitoring activities. Such activities would include monitoring the extent to which medical documentation from community providers is available or missing systemwide, given that community providers are required to submit documentation within 30 days of the first and final visits and its importance to veterans’ continuity of care.

According to VHA officials, this coordination is especially important so that all of a veteran’s providers can be well positioned to make sound decisions about the veteran’s care. By monitoring the exchange of medical documentation between VA medical centers and community providers, IVC would be better positioned to assess the extent to which missing medical documentation is posing a risk to veterans’ continuity of care. Further, it would allow IVC to fully quantify, describe, and address related challenges across all VA medical centers. For example, using goals and measures to monitor the medical documentation exchange would allow IVC to identify trends over time about the extent to which documentation is available at all VA medical centers.

Such information would further allow IVC to then examine data at the VA medical center level to determine whether certain factors—such as the categories of care, specific exchange method (e.g., electronic fax, the HealthShare Referral Manager), or insufficient staffing—are associated with missing information. For example, we found that only about 10 percent (2,229 of 22,725) of community providers with at least one behavioral health referral from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 used the HealthShare Referral Manager to send initial medical documentation to VA medical centers as compared to other methods. However, those that used the HealthShare Referral Manager had a lower percentage of referrals with missing documentation (about 31 percent) compared to providers that did not use it (about 69 percent). Additionally, community care staff we spoke with from one VA medical center told us that they tend to receive the least amount of information for psychotherapy referrals (which may require many visits over 6 to 12 months of care) compared to other categories of care. Further examining information to determine how these factors affect medical documentation exchange could help inform IVC’s programmatic decision-making and facilitate document exchange improvements such as developing or adjusting relevant guidance and targeting improvement efforts toward the challenges faced by the VA medical centers that are having more difficulties than others.

IVC’s lack of monitoring of the medical documentation exchange process poses a particular risk for the continuity of care for veterans who return to VA medical centers for behavioral health services after receiving them from community providers. As discussed earlier, about 71 percent (160,497 of the 224,741) veterans who received behavioral health services from community providers from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 returned to receive services from a VA provider. Among these 160,497 individuals, about 43 percent of them were missing initial medical documentation from at least one of their referrals. Community care staff from three selected VA medical centers and community care leadership from two Veterans Integrated Service Networks told us that it is a common goal for veterans to return to VA to ensure their continuity of care. Veterans Integrated Service Network officials further noted that receiving medical documentation from community providers is critical to avoid veterans experiencing any delays in follow-on care and to avoid duplicate testing or consults.

Only Two Percent of Community Providers Completed Core Trainings but VHA Does Not Monitor Completion nor Has It Clearly Communicated Training Information to Providers

VHA’s IVC Does Not Monitor the Extent to Which Community Providers Complete Required and Recommended Core Trainings

VHA’s IVC’s Office of Integrated External Networks—the VHA office responsible for overseeing performance through monitoring activities—does not monitor the extent to which community providers have completed the core trainings that IVC identified in September 2021. Specifically, IVC officials said that they have not used available data to determine the extent to which community providers have completed IVC’s one required opioid safety initiative training or the seven other recommended core trainings.[35]

According to officials from the Office of Integrated External Networks, their Provider Profile Management System Data Management Team receives a weekly report that provides a snapshot of community providers who completed a core training during the prior week, but IVC does not use such reports to monitor completion of required or recommended trainings. Specifically, IVC officials told us each weekly report is automatically populated with VHA TRAIN information from the prior week and includes the community provider names, emails, national provider identifier numbers, and course completion dates.[36] These officials said that the information on these weekly reports is then automatically uploaded into VHA’s Provider Profile Management System—VA’s master database of community providers that includes providers’ demographic information, the types of services they provide, and trainings completed.[37] According to IVC’s Provider Profile Management System standard operating procedures, the purpose of including information about completed trainings in that system is to help inform the scheduling process for VA medical center staff. As such, VA medical center staff could utilize the system to determine whether a community provider has completed trainings that would help ensure the provider’s understanding of IVC’s expectations for providing care to veterans.

According to IVC, it is important for community providers to complete the eight core trainings to help them deliver high-quality care for veterans. However, according to officials from IVC’s Office of Integrated External Networks, they do not analyze the weekly reports or access related underlying data from VHA TRAIN to monitor the extent to which all community providers have completed each of the required or recommended core trainings over time. Specifically, according to IVC officials, the weekly reports only list information about trainings that community providers completed during the prior week and thus cannot be used by IVC to monitor training completion over time. The information needed for such historical analyses (e.g., all community providers who completed or did not complete a required or recommended core training over a given time period) is only readily available in the VHA TRAIN system.

Our analysis of VHA TRAIN data found that community providers’ completion rates for the required and recommended core trainings have been low. Only 380 (about 2 percent) of the 22,725 community providers with a behavioral health referral from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 completed at least one of the eight core trainings in VHA TRAIN (see fig. 5).[38] The required opioid safety initiative training had the highest completion rate by community providers who had completed at least one training course (336 of 380). The recommended training on traumatic brain injury had the lowest completion rate (3 of 380). These 380 community providers had an average completion rate of only about 1.3 of the eight core trainings.

Figure 5: Community Providers with at Least One Behavioral Health Referral from Fiscal Years 2021 Through 2023 That Completed One Required and Seven Recommended Core Trainings

Note: In September 2021, the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) Office of Integrated Veteran Care (IVC) identified eight core trainings related to the unique veteran experiences and exposures that can help equip community providers with the knowledge needed to successfully provide care to veterans. The data in figure reflect the proportion of community providers who completed these trainings during fiscal years 2021 through 2023 as captured in VHA Training Finder Real-time Affiliate Integrated Network (TRAIN). This is a web-based platform through which VHA provides training courses to community providers and others. IVC currently requires all community providers to complete opioid safety initiative training. IVC recommends that community providers also complete seven other trainings on topics related to military cultural competency, lethal means safety, suicide prevention, traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, and military sexual trauma.

When we discussed our analysis of VHA TRAIN data with IVC officials, they said they were unaware of the low completion rates. They told us that any tracking of community provider training completion would be the responsibility of the two third-party administrator contractors. However, both contractors told us that while they promote and encourage community providers to complete trainings, they do not track whether each community provider has completed any of the core trainings or conduct analyses of such data for monitoring training completion across their networks. They noted that they are not contractually obligated to do this.[39] Further, the contractors said they do not have access to information in VHA TRAIN or receive such information on providers training completion from IVC.

As noted, IVC officials told us that they are not currently tracking community provider completion of required or recommended core trainings. They said that the required opioid safety initiative training is a priority and IVC is examining data related to community provider completion of it.[40] However, they did not provide additional information or documentation related to establishing a related monitoring effort. IVC officials also noted that they do not have plans to monitor any of the recommended core trainings. They stated that IVC does not monitor completion of the eight core trainings because IVC focused its oversight efforts on competing priorities such as ensuring community provider network adequacy and timely scheduling of appointments.

According to IVC, community providers who do not complete opioid safety initiative training within 180 days of enrolling in a regional network are not supposed to receive any new referrals until they complete the training. As noted above, while only 336 (about 2 percent) of the 22,745 community providers with at least one behavioral health referral from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 completed the opioid safety initiative training. However, IVC officials told us they have not taken action to halt new referrals for community providers that did not complete the required opioid safety initiative training. According to IVC officials, enforcing completion of required training could be problematic in ensuring network adequacy—that is, that each regional network is adequate in size, scope, and capacity to ensure that veterans receive timely access to care. They noted that terminating providers for not completing required trainings could put network adequacy at risk. However, IVC has thus far not determined how it or the third-party administrator contractors could increase completion rates across all core trainings.

IVC has not taken key performance management steps that would necessitate such monitoring. Specifically, IVC has not established goals and related performance measures that IVC’s Office of Integrated External Networks could use in conjunction with available VHA TRAIN data to monitor the extent of core training completion among all community providers over time and ensure they are properly equipped to provide high-quality behavioral health services to veterans. For example, according to IVC officials, IVC has not set goals (e.g., ensuring all community providers complete the required training and increasing the number of community providers who complete the recommended core trainings) and related performance measures (e.g., how quickly they expect providers to meet these goals).

IVC’s lack of monitoring is also inconsistent with key performance management steps described in our prior work. As noted above, key performance management steps include establishing goals and performance measures and using related information to assess progress toward goals and inform decisions.[41] In this case, such steps would include IVC monitoring the extent to which community providers are completing training by setting goals and performance measures and using such information to inform related decisions, such as identifying and addressing any challenges related to community providers’ completion of the eight core trainings.

Such monitoring would be consistent with the responsibilities outlined in VA policy and IVC governance documentation. As noted above, principal offices (such as IVC) are responsible for overseeing their national programs (such as the Veterans Community Care Program). According to VA’s Functional Organizational Manual, IVC’s Office of Integrated External Networks is responsible for program oversight, with a focus on performance. This includes monitoring, measuring, and reporting on performance to ensure high-quality care for all veterans. Further, as IVC officials confirmed this office is specifically responsible for overseeing performance through monitoring activities. Such activities would include monitoring community providers’ training completion. According to IVC’s Standard Operating Procedures for entering training information into the Provider Profile Management System, one indicator of community providers’ commitment to providing high-quality care to veterans is their completion of core trainings.

While monitoring the total number of community providers who are completing the eight core trainings would be useful to ensuring the training program’s effectiveness, there is no office within IVC that is accessing this information to evaluate it. Without monitoring core training completion, IVC is unable to assess the extent to which a lack of training is posing a risk to quality of care for veterans. Without assessing this risk, IVC is not well positioned to quantify, describe, or address potential challenges associated with providers’ completion of training. For example, by not analyzing the numbers and types of providers who did not complete a given core training, IVC is not well positioned to know which trainings are completed least frequently and examine related challenges. Thus, IVC does not have the information it needs to better target its outreach efforts, or those of its contractors, to help increase completion rates for those trainings. In addition, improving the number of community providers who complete core trainings would, in turn, help IVC better ensure that community providers understand and meet the unique needs of the veteran population, such as the need to treat post-traumatic stress disorders and other serious health conditions that often result from past military service.

VHA’s IVC Has Not Clearly Communicated Information Regarding Core Trainings to Community Providers

VHA’s IVC and its third-party administrator contractors use several mechanisms to provide community providers with information about required and recommended core trainings and other topics. According to IVC officials, IVC communicates directly with community providers through its monthly provider advisor newsletter, which covers a range of topics that are important for all community providers. In addition, representatives from IVC’s third-party administrator contractors told us they communicate with community providers through several mechanisms, including newsletters, fax blasts, provider manuals, and website advertising.

However, in their outreach efforts IVC and its third-party administrator contractors’ have not clearly or consistently communicated essential information about the eight core trainings, including whether they are required or recommended. Specifically, we reviewed nine of IVC’s monthly provider advisor newsletters between January 2023 and January 2025 and found that IVC provided a link and general description for no more than two of the eight core trainings in each of those newsletters.[42] Also, none of the newsletters stated that all community providers are required to complete the opioid safety initiative training. In addition, we reviewed the third-party administrator contractors’ community provider handbooks, which they use to help administer their contracts with community providers. We found similar issues.[43] For example, as of February 2025, one contractor’s handbook references only three of the eight core trainings (opioid safety initiative, military culture, and lethal means safety) and identified just one (military culture) as being recommended by IVC. The other contractor’s handbook is also unclear as it lists the required opioid safety initiative training as being both recommended and required.

Unclear communications from IVC and its contractors to community providers regarding training may affect providers’ awareness of these trainings and contribute to providers’ low training completion rates. For example, we spoke with 13 community providers who are members of three behavioral health service organizations and only three of the 13 providers told us they were aware of and had taken the required opioid safety initiative training. In addition, four of these community providers told us that they know VA has high-quality trainings available, but they are difficult to find given the abundance of information available. They said that knowing which trainings they should take can be confusing because the trainings do not identify specific target audiences (e.g., community providers, family members) they are intended for. However, all of the community providers agreed that training related to veteran-centric issues is important for treating veterans.

IVC has focused its oversight efforts on competing priorities (e.g., ensuring network adequacy) and therefore, it has not taken steps to ensure that information about the need to complete core trainings is clearly communicated to community providers in either its or the contractors’ outreach efforts. However, IVC could take steps to communicate such information more clearly. For example, IVC could provide links to all of the core trainings in its monthly provider advisor newsletter and clearly emphasize the importance of completing required and recommended trainings. IVC could also take additional oversight measures with the third-party administrator contractors by reviewing information about core trainings that the third-party administrator contractors include in their outreach materials to community providers and requesting that the contractors also take specific actions to communicate information about the importance of completing the core trainings.

IVC’s unclear communication regarding its core trainings is inconsistent with the federal internal control standard for information and communication, which states that management should communicate quality information externally so that external parties can help the agency achieve its objectives.[44] In this case, communicating quality information to achieve objectives means that IVC should take steps to ensure that it and its contractors are clearly communicating accurate and complete information to community providers about the importance of completing core trainings.

By not clearly communicating the importance of completing military cultural competency and other core trainings, IVC has missed an opportunity to ensure that its community providers are better equipped to provide quality care to veterans given that the trainings cover behavioral health risks commonly found in the veteran population. For example, three of the eight core trainings cover suicide prevention efforts, which is VA’s stated top clinical priority given the increased risk of suicide among veterans compared to that of the general population.[45] These trainings aim to educate providers on, for instance, how to work with their veterans to facilitate lethal mean safety during high-risk periods, while emphasizing veteran autonomy and the need to work with each veteran’s values and preferences. Clearly communicating information about the trainings would increase providers’ likelihood of completing the required and recommended trainings and, in turn, increase the effectiveness of providers’ treatment efforts when providing services to veterans at risk of suicide or who have behavioral health needs that are addressed by the other core trainings.

Conclusions

With nearly three-fourths of veterans returning to VA medical centers for behavioral health services after seeing a community provider for such services, ensuring that VA medical centers and community providers exchange medical documentation is critical to avoiding risks to the veterans’ continuity of care.

IVC does not know the extent to which medical documentation (either initial or final) from community providers is available or missing systemwide because IVC has not established goals and measures that would necessitate monitoring efforts, and data are incomplete in the absence of guidance for tracking final medical documentation. Given the data showing missing initial medical documentation for about one-third of behavioral health referrals and given the lack of data that would illuminate the extent of missing final medical documentation, it is critical for IVC to take action to monitor the medical documentation exchange from community providers. Such action is becoming more imperative as the use of community care has grown in recent years and some VA medical center community care programs have insufficient staffing, which can impede their ability to obtain documentation from community providers. By establishing an expectation that VA medical centers track final medical documentation and by establishing goals and measures for monitoring medical documentation exchange, IVC will be better positioned to help address these issues.

It is also important that community providers have military cultural competency, which the core trainings required and recommended by IVC are intended to convey. Without setting goals for providers’ completion of this training and monitoring progress toward those goals, IVC cannot determine how to improve upon the low number of providers who complete core training. Such measurement and clear communication about training would help IVC better ensure that community providers are taking the training and are thereby more equipped to meet the unique needs of the veteran population.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following five recommendations to VHA:

The VHA Under Secretary for Health should ensure that IVC develops guidance for VA medical centers’ efforts in obtaining final medical documentation after all visits provided to a veteran under each referral have been completed. (Recommendation 1)

The VHA Under Secretary for Health should ensure that IVC establishes goals and related performance measures for VA medical centers in obtaining initial and final medical documentation from community providers. (Recommendation 2)

The VHA Under Secretary for Health should ensure that IVC establishes a process for regularly using performance information for VA medical centers in obtaining initial and final medical documentation from community providers to assess its progress toward established goals. (Recommendation 3)

The VHA Under Secretary for Health should ensure that IVC establishes and monitors goals and related performance measures for community providers’ completion of core trainings and ensures that community providers complete the required training course. (Recommendation 4)

The VHA Undersecretary for Health should direct IVC to take steps to ensure that it and its contractors communicate clear and accurate information to community providers regarding IVC’s core trainings, including whether training is recommended or required. (Recommendation 5)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to VA for review and comment. VA provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix III. VA concurred in principle with our three recommendations regarding medical documentation exchange and described actions it would take to address them. For our first recommendation, VA noted that ensuring seamless coordination of care is essential to providing veterans with the highest quality of health care and that obtaining complete medical documentation after all visits have been completed enhances the continuity and effectiveness of such care. VA also noted that while it has identified challenges in determining when the final appointment is complete, VA will explore options for developing guidance for obtaining medical documentation after veterans complete all visits under each referral. VA stated that actions to address our second and third recommendations will be based on actions associated with the first recommendation, but it will continue taking existing and general actions to improve the success of obtaining medical documentation from community providers. VA estimated that actions to address our first three recommendations would be completed by March 2026.

VA concurred in principle with our fourth recommendation. VA said that VHA acknowledges the importance of veterans receiving exceptional care from community providers and that completion of required training is vital and an important aspect of quality care assurance. VA said that IVC will continue to work with the third-party administrator contractors to explore opportunities to improve compliance with required training and will strongly encourage community providers to complete additional recommended core trainings.

VA concurred with our final recommendation and said that VHA will take steps to ensure that IVC and the third-party administrator contractors communicate clear and accurate information to community providers regarding IVC’s core trainings, including whether training is recommended or required. VA estimated that actions to address our fourth and fifth recommendations would be completed by September 2025. VA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated, as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at SilasS@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Sharon M. Silas

Director, Health Care

This report (1) describes what the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) data show about behavioral health referrals to community care for veterans from fiscal years 2021 through 2023, (2) describes challenges affecting the medical documentation exchange processes and steps VA’s Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is taking to mitigate those challenges, (3) evaluates the extent to which VHA provides guidance for and monitors medical documentation exchange for behavioral health referrals between VHA and community providers, and (4) evaluates the extent to which VHA monitors and communicates information about community providers’ completion of military cultural competency and other trainings.

To describe what VA data show about behavioral health referrals to community care for veterans from fiscal years 2021 through 2023 (the most recent complete data available at the time of our review), we analyzed systemwide data from VA’s Corporate Data Warehouse for all behavioral health referrals for those fiscal years. We analyzed the data to determine the total number of behavioral health referrals made during this time period and the number of veterans for whom referrals were made. We examined the data by categories of care (e.g., outpatient psychotherapy, outpatient psychiatry), and categories of diagnoses (e.g., anxiety and stress-related disorders, substance abuse disorders). We also examined the data by veteran socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., race, gender, geographic location) and active suicide or behavioral risk flag status.

To describe challenges affecting the medical documentation exchange process and steps VHA is taking to mitigate those challenges, we interviewed officials from VHA’s Office of Integrated Veteran Care (IVC) and relevant VHA program offices. We also interviewed representatives from VA’s two third-party administrator contractors that manage regional networks of community providers. In addition, we also interviewed representatives from three Veteran Service Organizations about any challenges veterans may have experienced related to community care for context.[46] We reviewed guidance that IVC provides to VA medical centers, documentation from VHA (e.g., directives), and VA Office of Inspector General reports for contextual information about this process. In addition, we reviewed relevant requirements in VA’s community care network contracts for additional context.

Further, we conducted virtual site visits in April and May 2024 with five VA medical centers. We selected the centers based on, among other factors, facility complexity-level, geographic variation, and total number of behavioral health referrals made by each VA medical center to community providers from fiscal years 2021 through 2023.[47] At each of these, we interviewed leadership, community care staff, and managers about their experiences related to medical documentation exchange processes, including in coordinating with community providers and community care network contractors. We also reviewed documentation that the VA medical centers provided us (e.g., standard operating procedures, facility-specific reports on behavioral health referrals to community providers) related to medical documentation exchange processes to understand their local processes, for context. In addition, we interviewed 14 community care leaders and other officials from four of the five regional Veteran Integrated Service Networks in which those five VA medical centers are located.[48] The information we obtained from these virtual site visits is not generalizable to other VA medical centers or Veterans Integrated Service Networks, but rather provide illustrative examples of local and regional challenges related to medical documentation exchange processes.