TRANSIT WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

Actions to Support Transition to Zero-Emission Buses

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-106921

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106921. For more information, contact Andrew Von Ah at (202) 512-2834 or vonaha@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106921, a report to congressional committees

November 2024

Transit workforce development

Actions to Support Transition to Zero-Emission Buses

Why GAO Did This Study

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act made about $5.6 billion available for the Low or No Emission Grant Program for fiscal years 2022 through 2026 to help transit agencies purchase low- and zero-emission buses, and for related purposes. The successful deployment of zero-emission buses—battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell electric buses—depends in part on transit agencies having skilled workers to operate and maintain these buses.

House Report 117-402 includes a provision for GAO to review workforce development needs as transit agencies transition to zero-emission vehicles. This report describes: (1) the status of transit agencies' transition to zero-emission bus fleets and any challenges they may face meeting transition goals; (2) skill- and workforce-development needs of transit agencies and actions selected agencies are taking to address any workforce gaps; and (3) FTA actions to assist transit agencies in preparing their workforces for zero-emission buses.

GAO analyzed FTA data on the nationwide bus fleet as of 2022—the most recent available data—and reviewed applicable statutes, regulations, and agency documents. GAO interviewed 18 transit stakeholders and officials at 10 selected transit agencies to obtain views on zero-emission buses and workforce development needs. GAO selected transit agencies based on factors including agency location and fleet makeup. GAO also interviewed officials at eight transit entities in the Netherlands and United Kingdom about their workforce transitions, as they have high numbers of zero-emission buses in operation.

What GAO Found

The transit industry is working to address climate change by lowering greenhouse gas emissions, in part by transitioning to zero-emission buses. According to Federal Transit Administration (FTA) data, zero-emission buses comprised 2 percent of the bus fleet for large urban transit agencies nationwide in fiscal year 2022 (2,061 zero-emission buses). FTA projects that zero-emission buses or other vehicles in operation will more than triple by fiscal year 2030 (to 7,700). However, officials from FTA and 10 selected transit agencies GAO interviewed generally agreed that several key challenges need to be addressed in the near term, particularly the limited supply of new zero-emission buses. FTA is working with the industry to address bus supply and manufacturing issues, encouraging actions to reduce bus costs and earlier payments on bus orders.

Transit agency officials GAO met with said that while workforce issues related to the transition are not an immediate priority, they are taking steps to provide training specific to zero-emission buses, as needed, and to address the ongoing shortage of frontline workers. Transitioning to zero-emission buses will most significantly change the traditional mechanic role, making it more of a technician role that requires the use of electronic equipment to diagnose and address engine error codes, according to FTA officials. All 10 selected transit agencies collaborated with bus manufacturers to design training materials and deliver training to their mechanics. However, these transit agencies said their specific future workforce needs are uncertain, in part, because of unpredictable bus delivery timeframes. They said they plan to continue their existing recruitment and retention strategies, such as partnering with community colleges and offering apprenticeships to address current workforce shortages.

FTA is leading several activities to help transit agencies prepare their workforces for zero-emission buses. For example, in 2021, FTA established the Transit Workforce Center to provide direct technical assistance to transit agencies on various workforce issues, including apprenticeships, training, and recruitment.

Abbreviations

|

AC Transit |

Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District |

|

APTA |

American Public Transportation Association |

|

ASE |

National Institute for

Automotive Service |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

FTA |

Federal Transit Administration |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

Joint Office |

Joint Office of Energy and Transportation |

|

Los Angeles Metro |

Los Angeles County Metropolitan

Transportation |

|

MTA |

Metropolitan Transportation Authority |

|

NEN |

Royal Netherlands Standardization Institute |

|

NTI |

National Transit Institute |

|

SunLine |

SunLine Transit Agency |

|

TWC |

Transit Workforce Center |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 18, 2024

The Honorable Brian Schatz

Chair

The Honorable Cindy Hyde-Smith

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development,

and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Steve Womack

Chairman

The Honorable Mike Quigley

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development,

and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The transit industry, like other U.S. industries, is working to address climate change by lowering greenhouse gas emissions. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. transportation sector accounted for about 28 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2022—the largest portion of emissions of any sector.[1] According to the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), public transportation plays an important role in reducing fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change. Moreover, the transit industry aims to further reduce greenhouse gas emissions by transitioning from diesel-powered to low- or zero-emission buses.

Within the Department of Transportation (DOT), FTA also supports transit industry efforts in several ways, as it administers grant funding to eligible recipients, including states and localities, that may be used to support this transition. For example, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) authorized and appropriated about $5.6 billion for fiscal years 2022 through 2026 for the Low or No Emission Grant Program for transit agencies and other eligible recipients to implement projects related to low- or no-emission vehicles, including the acquisition or leasing of these vehicles.[2] Under this FTA program, recipients generally must use 5 percent of their funding related to zero-emission vehicles or associated infrastructure for workforce development and training.[3]

The successful deployment of zero-emission buses—which include battery electric buses and hydrogen fuel cell electric buses—depends, in part, on transit agencies having skilled and qualified workers to operate and maintain them. According to a 2023 American Public Transportation Association (APTA) report, many transit agencies face ongoing shortages of frontline and skilled workers.[4] In addition, a 2021 FTA report on transit training needs identified changing bus technologies as a challenge for transit agencies, including training on battery electric buses that requires a different set of skills than diesel or gasoline engine vehicles.[5] In August 2023, FTA published the National Transit Workforce Development Strategic Plan 2023 to 2028, identifying the agency’s workforce development goals. In addition to FTA, the Department of Labor and the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (Joint Office) also have programs to support the transit workforce.

House Report 117-402 includes a provision for GAO to review workforce development needs as transit agencies transition to zero-emission vehicles.[6] This report describes (1) the status of transit agencies’ transition to low- and zero-emission bus fleets and any challenges they may face meeting transition goals over the next decade; (2) skill- and workforce-development needs of transit agencies and actions selected transit agencies are taking to address workforce gaps; and (3) actions taken by FTA to assist transit agencies in preparing their workforces for zero-emission buses.

To describe the status of transit agencies’ transition to zero-emission vehicles, we analyzed data from FTA’s 2023 National Transit Database on the nationwide bus fleet—reported by large urban transit agencies at the end of fiscal year 2022—which were the most current data available at the time of our review.[7] To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed information published by FTA about how these data are validated and requested additional information from the agency specifically about using these data to describe the status of the transition to zero-emission buses. We determined the data in the National Transit Database to be sufficiently reliable for our purposes.

We also interviewed 18 transit industry stakeholders, such as APTA and the Community Transportation Association of America, to collect information on the transition to zero-emission buses, including uncertainties and challenges. We identified these stakeholders through our prior work on transit workforce development, as well as recommendations from other stakeholders.[8] We also reviewed applicable statutes and regulations.

Finally, we interviewed and obtained data from 10 selected transit agencies about their experiences operating low- or zero-emission buses, plans to increase the number of such buses in their respective fleets over the next 10 years, and current or anticipated challenges.[9] The information provided by the 10 selected transit agencies is not generalizable to all transit agencies. To obtain a range of perspectives from agencies that have begun to transition to zero-emission buses, we selected these transit agencies based on factors to reflect a range of locations, service-area population sizes, and fleet makeup, including the types of zero-emission buses they had. For the purposes of our report, we focused on zero-emission buses rather than low-emission buses because zero-emission buses generally use newer technologies and may pose greater workforce challenges to agencies adopting them. We generally did not include trolleybuses, which use more established technology, in the scope of our work, except where noted.

To identify the skill and workforce development needs for transit agencies to transition to zero-emission buses, we reviewed transit industry reports and documents. We also interviewed our 18 transit stakeholders, which include technical assistance providers, transit unions, and bus manufacturers, as well as our 10 selected transit agencies on training efforts and any relevant industry standards. We also reviewed fleet transition plans that our selected agencies submitted to FTA as part of their applications for Low or No Emission Grant funding.

Finally, we obtained information from and interviewed eight selected transit stakeholders in Amsterdam, the Netherlands and London, United Kingdom about their workforce transitions and any lessons learned during their transition. The information we obtained is not generalizable to all transit stakeholders in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. We selected these transit stakeholders because the transit systems in these cities are further along in their transition to zero-emission fleets, with high numbers of such buses in operation.

To describe FTA and other federal agencies’ actions to assist transit agencies in preparing their workforces, we reviewed documents and interviewed officials from FTA and other federal agencies, as well as FTA’s technical assistance partners involved in workforce development, including the Transit Workforce Center. We also reviewed applicable statutes. See appendix I for more information about our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

According to FTA, there are nearly 3,000 transit agencies in the U.S., of which about 500 are large urban agencies that provide bus service. There are also a variety of bus propulsion types that transit agencies may choose as they transition away from diesel- and gasoline-powered buses, representing a mix of existing and new low- and zero-emission technology. Low-emission buses, which have been in operation in many locations for a number of years, include hybrid-electric buses, as well as buses operating with compressed natural gas, propane, and other alternative fuels. In the 2010s, bus manufacturers began to offer, and some transit agencies began using, battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell electric buses, referred to as zero-emission buses.

Zero-emission buses are generally substantially more expensive than diesel buses. For example, based on a 2023 contracted price list between one U.S. manufacturer and Washington State, base prices for a 40-foot battery electric bus and hydrogen fuel cell electric bus were approximately $1 million and $1.3 million, respectively, compared to approximately $560,000 for a diesel bus. These estimates are for the bus alone and do not include costs for the supporting infrastructure that transit agencies need to power these buses. Supporting infrastructure includes various types of electrical charging equipment, such as en-route chargers, overhead charging stations, or plug-in chargers, as illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1: Examples of Charging Infrastructure for Battery Electric Bus Propulsion Include En-Route Chargers, Overhead Charging Stations, and Plug-In Chargers

Transit agencies can use FTA grant funding for eligible projects, which for some grant programs includes the purchase of zero-emission buses and related facilities and equipment.[10] For example, the IIJA continued the Buses and Bus Facilities Formula and Competitive Grant Programs. These programs’ funding may be used by transit agencies to purchase buses—which may include low- and zero-emission buses—and related equipment, as well as to construct related facilities, and for other purposes. It also continued the Low or No Emission Grant Program, which is a competitive grant program.[11] The IIJA authorized almost $2 billion for the Buses and Bus Facilities Competitive Grant Program, and authorized and appropriated approximately $5.6 billion for the Low or No Emission Grant Program, for fiscal years 2022 through 2026.[12] While both the competitive and formula Buses and Bus Facilities Grant programs may fund eligible projects related to buses of all propulsion types, the Low or No Emission Grant Program only funds eligible projects related to low- or zero-emission vehicles, which include zero-emission buses.[13]

As of July 2024, FTA awarded almost $5 billion under the Low or No Emission Grant Program and the Buses and Bus Facilities Competitive Grant Program, which totals about two-thirds of the approximately $7.6 billion of funding that IIJA authorized and appropriated for these programs for fiscal years 2022 through 2026.[14] FTA’s 117 fiscal year 2024 awards include funding for 1,149 total buses, of which 466 are zero-emission buses, 454 are low-emission buses, and 229 are conventional (diesel) buses.[15] Transit agencies have 4 fiscal years to obligate funding received through these programs, a time period which, according to FTA, begins with the fiscal year in which the awards are announced.[16]

Applicants for these two programs’ grants are required to submit a zero-emission fleet transition plan, if their proposed projects relate to zero-emission vehicles.[17] These plans are to include information about the transit agency’s fleet transition and to examine the impact of the fleet transition on the applicant’s current workforce. Such an examination is to include identifying skill gaps and the training and retraining needs of existing transit workers to operate and maintain zero-emission vehicles and related infrastructure. In addition, applicants must identify in their application how they would use 5 percent of their total requested grant amount for transit workforce development and training.[18]

As we and others have previously reported, transit agencies have faced frontline transit worker shortages for a number of years.[19] In 2023, APTA issued a Transit Workforce Shortage Synthesis Report, which found that this shortage stemmed from factors such as agencies’ aging workforce and high retirement rates, as well as increased competition for drivers and mechanics.[20] In addition, APTA reported that the COVID-19 pandemic caused transit ridership to plummet, which contributed to ongoing financial challenges for many transit agencies. These financial and workforce challenges have extended beyond the pandemic, and in 2023, APTA reported that more than half of transit agencies it surveyed, especially larger ones, are facing severe fiscal constraints and budget shortfalls.

In 2019, we examined transit agencies’ workforce development efforts, including FTA’s role in supporting those efforts, and made three recommendations to FTA to help the agency more effectively leverage its resources to address future transit workforce needs and measure the effectiveness of its efforts.[21] FTA has implemented all three recommendations. For example, in response to our recommendation that FTA develop a strategy outlining how the agency will address future transit workforce needs, FTA issued a strategic plan in 2023.[22] The plan includes goals for worker safety, workforce investment, and recruitment. While the plan is not specific to the zero-emission bus transition, it identifies some key performance efforts for developing the workers needed for zero-emission technologies, such as developing and disseminating training resources for zero-emission technologies. We discuss FTA efforts to develop the zero-emission bus workforce later in the report.

Executive Order 14008, issued in 2021, established a policy to put the U.S. on a path to achieving net-zero emissions economy-wide by 2050.[23] However, countries and cities in Europe and in other parts of the world have set targets to move away from the use of diesel and gasoline buses specifically. For example, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation’s Briefing on the Rapid Deployment of Zero-Emission Buses in Europe from 2022, the Netherlands has one of the most ambitious national fleet transition goals in the world, and the country’s policy requires all new bus purchases to be fully zero-emission by 2025 onward and to completely transition bus fleets to zero-emission buses by 2030.[24] Similarly, the briefing states that London set a goal for a fully zero-emission bus fleet by 2034. In 2024, Transport for London stated that London had 1,397 battery electric buses and 20 hydrogen fuel cell electric buses, which comprised 16 percent of the overall fleet.

Agencies’ Transition to Zero-Emission Buses Has Been Limited to Date, and Selected Agencies Cited Several Transition Challenges

Zero-Emission Buses Make Up 2 Percent of the Nation’s Transit Fleet, and FTA Estimates Use Will Increase by 2030

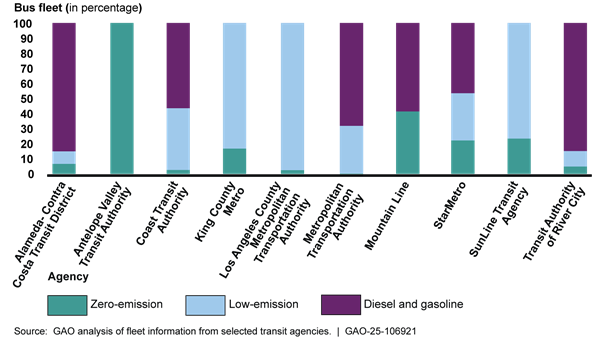

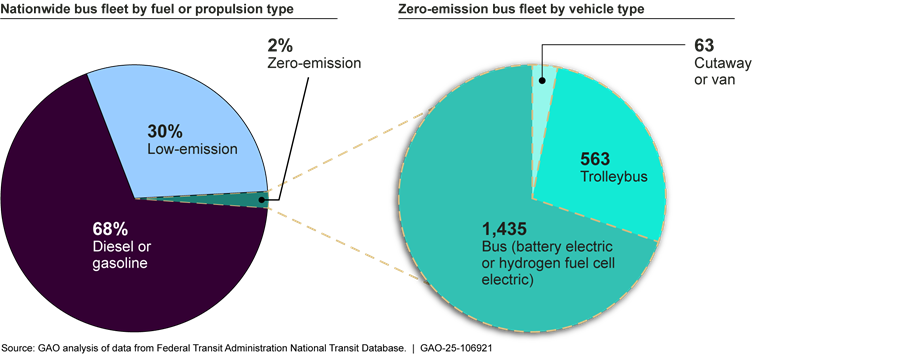

According to FTA data, zero-emission buses comprised 2 percent of the bus fleet available for operation at the end of fiscal year 2022 (2,061 of 90,252 buses) by large urban transit agencies nationwide.[25] Those buses included 1,498 battery electric or hydrogen fuel cell electric buses and cutaways or vans, as well as 563 trolleybuses powered from fixed overhead lines.[26] Low-emission buses accounted for substantially more of the fleet in 2022, comprising 30 percent. Diesel and gasoline buses constituted the majority of the bus fleet operated by large urban transit agencies, accounting for 68 percent (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Composition of the Bus Fleet Operated by 483 Large Urban Transit Agencies, Fiscal Year End 2022

Note: The “bus” category includes buses, articulated buses, over-the-road buses (e.g., motorcoaches), and double-decker buses as identified in the National Transit Database. Cutaways are vehicles in which a bus body is mounted on the chassis of a van or truck.

Some transit industry stakeholders estimate greater levels of adoption of zero-emission buses than FTA, though these stakeholders generally rely on different—and broader—information than FTA’s count of the number of buses in the active transit fleet. For example, according to APTA data included in its June 2023 vehicle database, 1,514 battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell electric buses were active, have been built, or are on order.[27] Additionally, CALSTART, an advocacy group for zero-emission transportation, reported in February 2023 that approximately 5,480 zero-emission buses had been funded, ordered, or delivered based on information from award documents and press releases.

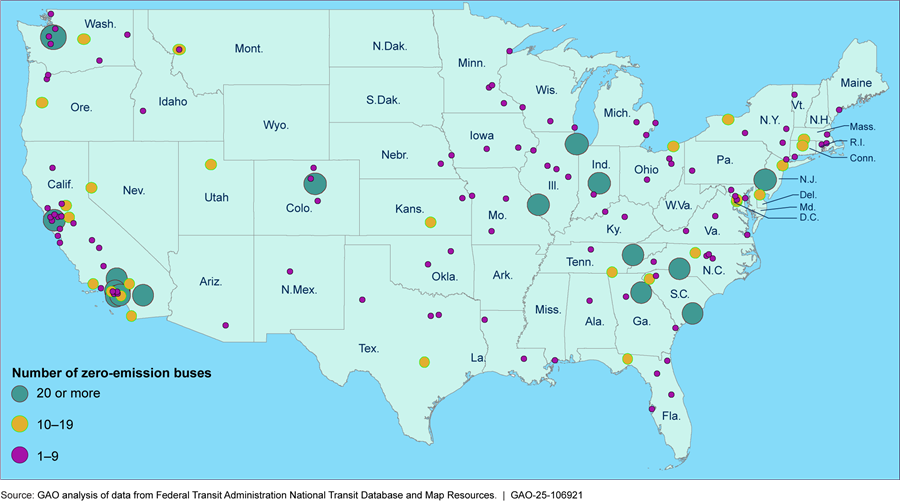

Transit agencies transitioning to zero-emission buses are generally planning to do so with battery electric buses and, to a lesser extent, hydrogen fuel cell electric buses, according to our analysis of FTA data. Focusing on these two types of zero-emission buses, we found that nearly a third (149 of 483) of large urban transit agencies nationwide had at least one zero-emission bus. Most of these agencies (103) had nine or fewer such buses, while 18 transit agencies had 20 or more buses. Of the 1,498 battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell electric buses operating nationwide, more than a third were operated by 36 transit agencies in California (562 buses).[28] California’s Innovative Clean Transit regulations require transit agencies within the state to set a goal to fully transition to a zero-emission bus fleet by 2040.[29] The regulations also provide that all new bus purchases by California transit agencies must be zero-emission buses, beginning in 2029.[30] Figure 3 identifies transit agencies nationwide with at least one active battery electric or hydrogen fuel cell electric bus in operation at the end of fiscal year 2022.

Figure 3: Large Urban Transit Agencies with Battery Electric or Hydrogen Fuel Cell Electric Buses, as of Fiscal Year End 2022

According to data provided by our selected transit agencies, zero-emission buses made up varying proportions of their fleets, ranging from one such bus (of 39) to operating a fully electric fleet. Figure 4 illustrates the proportion of the selected transit agencies’ bus fleet comprised of zero-emission buses, as well as buses operating with other fuel or propulsion types.

Note: Zero-emission buses include battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell electric buses for each of our selected agencies. King County Metro in Seattle, Washington also had 174 trolleybuses operating on fixed electric lines, which are included within the agency’s zero-emission buses. Four transit agencies provided 2024 fleet data: Antelope Valley Transit Authority (as of July 2024); Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (as of August 2024); SunLine Transit Agency (as of August 2024); and Mountain Line (as of September 2024). King County Metro provided fleet data as of October 2023. The five remaining transit agencies provided fleet data as of December 2022.

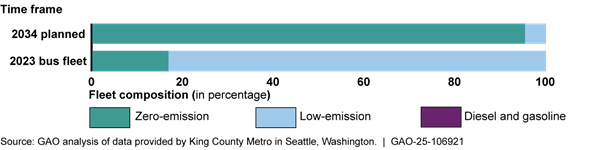

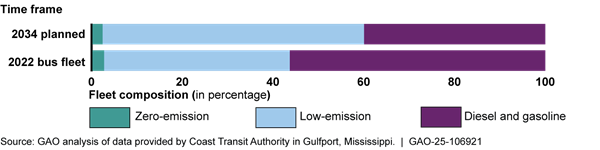

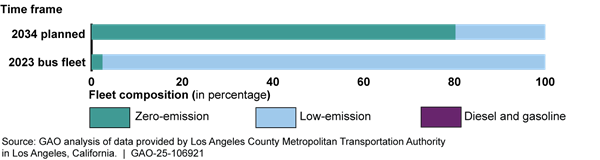

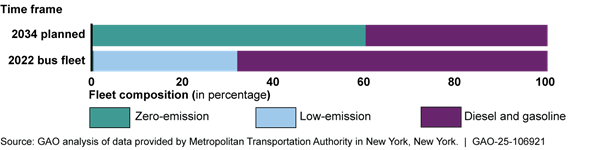

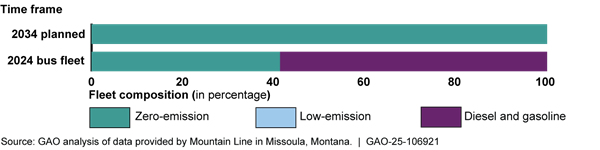

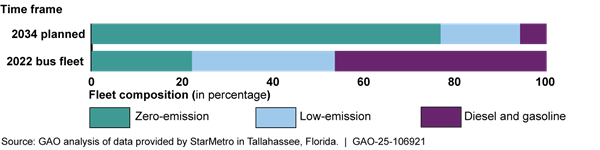

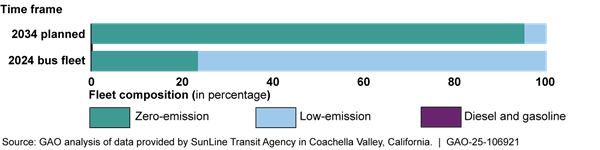

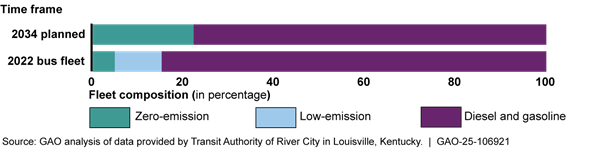

Based on fleet transition plans and information provided by our selected agencies, we found that each agency plans to adjust the composition of their bus fleet over the next decade to include additional zero-emission buses, but their approaches vary. For example:

· Four of our selected agencies are in California and are planning to fully transition their respective fleets to zero-emission by 2040 or before, which is the goal they were required to set under state law. Of these, one agency—Antelope Valley Transit Authority in Lancaster, California—currently operates a 121-bus, fully zero-emission fleet, which it plans to expand over the next decade. Antelope Valley Transit Authority officials stated that they were the first agency in the U.S. that had completed the transition to zero-emission buses.

· Four of our 10 selected agencies have also established goals for transitioning to a fully electric fleet by or before 2040. Of these, King County Metro in Seattle, Washington, and StarMetro in Tallahassee, Florida, aim to fully transition to zero-emission buses by 2035, for example. To achieve these goals, King County Metro plans to replace its largely low-emission fleet, while StarMetro plans to replace a mix of diesel or gasoline and low-emission buses. Mountain Line in Missoula, Montana, plans to gradually replace its existing fleet with zero-emission buses beginning in 2024 as they work toward their transition goal. Going forward, all the agency’s bus procurements will be battery electric, as its diesel and gasoline buses come to the end of their useful lives.

· Two of our 10 selected agencies plan to continue with a mixed fleet through 2034 and thereafter. Coast Transit Authority in Gulfport, Mississippi, for example, plans to focus on increasing the number of low-emission buses in the fleet—rather than zero-emission buses—while continuing to operate diesel buses for about a third of its fleet in 2034. According to Coast Transit Authority officials, this plan supports operational needs for emergency evacuation in the event of power outages during hurricanes.

For more information about the current fleet and planned transitions for our selected agencies, see appendix II.

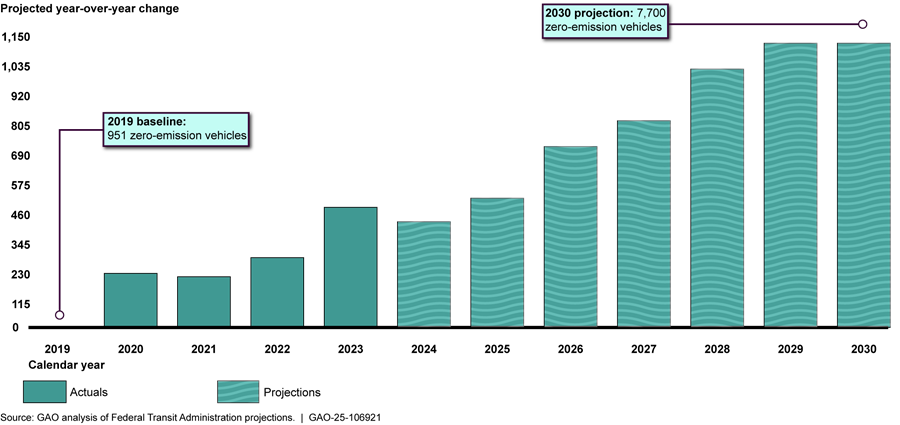

Nationwide, FTA officials told us that they expect the delivery of zero-emission buses to increase in the next few years as bus manufacturers respond to the increased orders placed by transit agencies with FTA grant funding awarded in fiscal years 2022 and 2023. FTA projects that by fiscal year 2030, transit agencies nationwide will have 7,700 zero-emission vehicles in operation—more than tripling the 2022 nationwide zero-emission fleet (see fig. 5).[31] FTA officials stated they are monitoring the production capacity of bus manufacturers and will revise projections as needed.

Figure 5: Federal Transit Administration’s Year-Over-Year Change Projections for the Nationwide Zero-Emission Fleet, Fiscal Years 2019–2030

Note: FTA’s projections are as of March 2024 for zero-emission vehicles, which include buses, cutaways, trolleybuses, and vans, as well as other zero-emission vehicles used for bus service such as automobiles and sport utility vehicles.

Bus Supply and Technology Challenges Could Jeopardize Transit Agencies’ Ability to Transition Their Fleet

APTA, FTA, and our selected transit agencies generally agree that transitioning fleets to zero-emission buses is a significant undertaking that will be further complicated by several key challenges that need to be addressed in the near term, particularly the limited supply of new zero-emission buses. According to APTA, as of February 2024, two major bus manufacturers in the U.S. market—Gillig and New Flyer—can produce 40-foot or 60-foot zero-emission buses that are eligible for federal funding.[32] According to transit industry news in 2023 and 2024, three other bus manufacturers left the U.S. market—ENC, Nova Bus, and Proterra.[33]

As a result of the limited supply of buses, some transit agency officials told us they are already experiencing long waiting periods from the time of procurement to bus delivery. Specifically, a few anticipate a 2-year lag for these buses, even if these manufacturers can increase their output.[34] Consequently, Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) officials in New York, for example, told us that they do not expect that the thousands of zero-emission buses their agency had planned for will be available in time to meet their 2040 goal of operating a fully electric fleet. Additionally, StarMetro officials expressed concern that the prices of buses may increase during the 2-year waiting period, decreasing the number of buses they can purchase, while the agency is already facing limited available funding for buses.

In communication with transit industry stakeholders, FTA has stated that bus and supply chain issues will delay the acquisition of new zero-emission buses and increase the cost of new buses and related equipment. In response, the agency has efforts underway to help address this challenge, including incentives to help contain bus costs and encouraging advance and progress payments on bus orders.[35] Specifically, FTA stated that in its selection of fiscal year 2024 projects for Buses and Bus Facilities (Competitive) and Low or No Emission Grant program awards, it prioritized applications that aim to help strengthen the financial health and stability of U.S. bus manufacturing such as by procuring standard model buses or using joint procurement. In February 2024, FTA also convened a high-level roundtable discussion on bus supply and manufacturing issues with transit stakeholders and held a webinar on bus procurement best practices to highlight some potential approaches to shorten production timeframes and to help maintain domestic manufacturing capacity.

In addition to the limited bus supply, transit agency officials we met with also identified other key challenges transit agencies will need to work through as they transition to zero-emission fleets. These challenges include (1) supply chain disruptions, (2) insufficient electrical infrastructure, (3) battery constraints affecting range, and (4) interoperability issues.

· Supply chain disruptions. Some transit agencies and manufacturers we met with said they have faced delays obtaining replacement parts for their current fleet or smaller zero-emission vehicles due to supply chain issues. Officials from Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District (AC Transit) in Oakland, California, for example, described long delays for replacement batteries, and an official from Mountain Line raised concerns about their ability to get parts for the Proterra buses in their fleet following the company’s bankruptcy. According to a representative from Forest River—a manufacturer of smaller transit vehicles, such as vans used for paratransit or passenger service or cutaway buses used as shuttle buses—electric vans are readily available for conversion into transit vans. However, the representative noted that there had been delays in the availability of the van chassis during the COVID-19 pandemic.

· Insufficient electrical infrastructure. Transit agencies need access to additional electrical supply to charge zero-emission buses for operation. According to an FTA guidebook, to supply this power, transit agencies should coordinate with local utilities and jurisdictions on the electrical permitting process and construction of additional electrical infrastructure and power sources.[36] The guidebook also described how such improvements can take time and resources, and agencies strive to coordinate these infrastructure upgrades and expansions with the arrival of the buses. Accordingly, King County Metro officials told us that the agency has had to plan 6 to 8 years in advance for the utility upgrades needed at its bus bases. Representatives from bus service companies in London and Amsterdam that are scaling up their fleet of battery electric buses told us that electrical grid capacity is their most significant constraint to further growth. They noted that this constraint is currently limiting the number of new electric buses they can bring into service. According to these representatives, this challenge is further exacerbated by utility customers across a number of industries competing for electrical upgrades.

· Battery constraints affecting range. According to officials from all 10 of our selected agencies, the driving range of battery electric buses is limited by the capacity of their batteries. An official with Mountain Line, for example, said that the range for the agency’s various brands of battery electric buses was about 110 miles—less than the 120 to 130 miles per charge that they had anticipated when procuring the buses. Officials with several agencies described having to recharge buses midday—called “opportunity charging”—or shorten planned routes in response to these range limitations. Weather can also affect battery range. Officials with SunLine Transit Agency (SunLine) serving Coachella Valley, California, said that their older electric buses are impacted by the area’s high temperatures. Similarly, MTA officials told us that bus batteries deplete by 50 percent when temperatures dropped from 70 to 30 degrees Fahrenheit, requiring them to adjust routes and schedules to allow for additional charging midday. A bus service provider in London told us they adjust service routes to handle diminished battery range on cold days. Given the limited number of zero-emission buses in the U.S. fleet, however, agencies may not have additional buses available to put into service under these circumstances.

· Interoperability issues. According to some transit officials we met with, as bus technologies have developed and continue to mature, interoperability issues arise due to the mix of different battery capacities and types of chargers. Such interoperability issues can complicate agencies’ transition plans. For example, according to an official from Mountain Line, different chargers from different manufacturers do not charge all buses. These chargers may also require some reprogramming by the manufacturer, according to Mountain Line. King County Metro officials similarly stated that their agency has several different battery electric bus models, and it is unclear whether older buses will be compatible with newer charging equipment and charge management software or between manufacturers. King County Metro is working to avoid future interoperability issues by adopting technology with certain charging standards.

While transit agencies we spoke with noted these challenges are top of mind in the near or intermediate term, they did not identify workforce concerns among these challenges. Rather, they noted that the above challenges may limit their ability to put larger numbers of federal funding-compliant zero-emission buses into service, thereby lessening the immediate need to address workforce issues. For example, King County Metro officials stated that the limited number of bus manufacturers and availability of battery electric buses in the next few years is their primary challenge, and that right now, it is relatively early to worry about future staffing. Nonetheless, King County Metro officials said that they are preparing for workforce issues related to transitioning to zero-emission buses. They said these issues will generally involve responding to existing workforce challenges—such as the shortage of transit agency staff—although new issues were also raised, as discussed below.

Transit Agencies Will Need Newly Skilled Workers, and Selected Agencies Are Focused on Addressing Ongoing Staffing Shortages

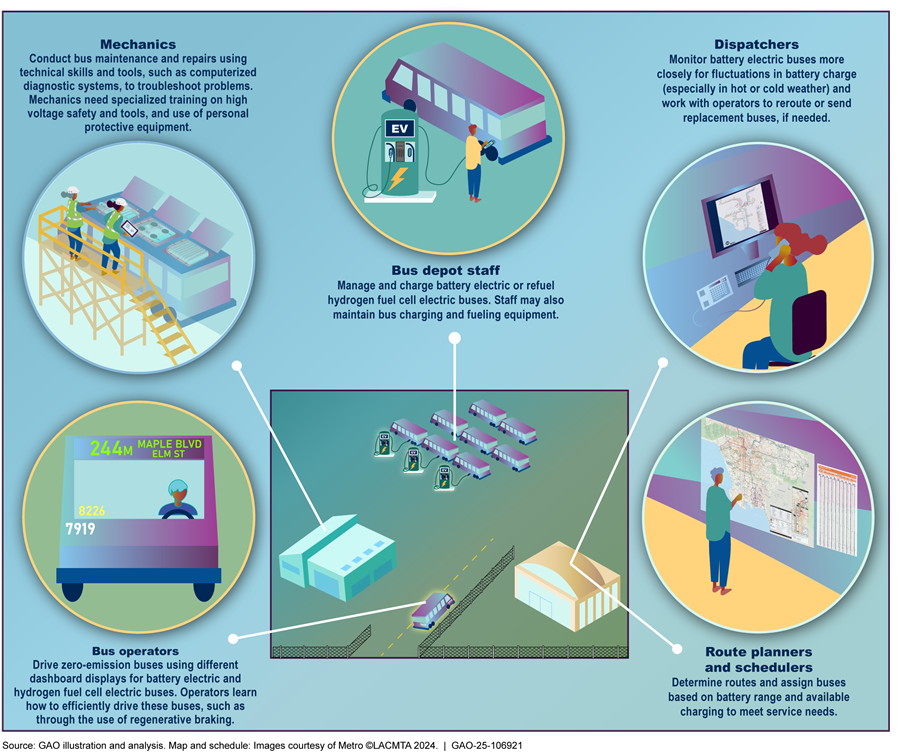

Industry Agrees on the Skills Mechanics Need, and Training Has Begun

While all aspects of a transit agency are involved in operating a zero-emission bus fleet, transitioning the fleet will most significantly change the mechanic role. All 10 of our selected transit agencies told us that their mechanics will need new skills and knowledge. A few examples of these skills include electric motor repair, computer literacy, and diagnostic troubleshooting. FTA officials, representatives from bus manufacturers, and officials with our selected transit agencies told us that the new skillset will change the bus maintenance role from that of a traditional mechanic—described to us as “turning the wrench” and changing fluids—to a technician role, using software and electronic equipment to diagnose and address bus engine error codes.

In addition to these skills, officials from nine of our selected transit agencies said mechanics and technicians will need to learn high-voltage safety procedures to protect employees from the new safety risks presented by battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell electric bus technology. For example, according to Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Los Angeles Metro) officials in California, high-voltage training typically includes the proper use of personal protective equipment and procedures to quickly and safely shut off power to equipment. Personal protective equipment includes insulated gloves, a helmet and face shield, and safety glasses (see fig. 6).

Figure 6: Personal Protective Equipment and Other Tools Used by Mechanics Who Maintain Zero-Emission Buses

Recently, industry stakeholders have developed guidance related to zero-emission bus maintenance training. This guidance includes recommended training materials, including guidance on developing the necessary electrical and safety skills and knowledge. For example:

· In October 2023, APTA published a recommended training practice for zero-emission bus maintenance, which provides agencies with guidance for developing training materials as well as specific recommended learning objectives.[37] For example, this guide recommends agencies split training into three levels with increasingly detailed information on high-voltage safety, zero-emission bus components, and how to perform repair tasks.

· In 2022, the International Transportation Learning Center published a report to help transit agencies obtain training from bus manufacturers.[38] The information in the report includes sample language that outlines the specific training topics and the length of time training should take as well as provides examples of the training aids, instruction manuals, and tools that should be included in the training materials purchased. The report also provides agencies with optional language to address the training needs of technicians who perform all warranty repairs on zero-emission buses.

However, there is no recognized certification that demonstrates mastery of zero-emission bus maintenance skills, according to FTA and transit industry groups.[39] Rather, it is up to individual transit agencies to determine the suitability of their staff to perform maintenance on these buses. For example, SunLine officials told us their maintenance training supervisors determine when mechanics have received sufficient training to work on zero-emission buses.

All 10 of the transit agencies we interviewed have training materials and collaborated with bus manufacturers to design and deliver training to their mechanics. While there are common training topics across agencies, each has tailored their training to the specific bus brands, types, and models that the transit agency operates.[40] For example, AC Transit officials told us they developed a 198-hour mechanics training course with bus manufacturers specific to their bus fleet. If transit agencies buy buses from different manufacturers, they generally need additional training, given differences among buses. For example, officials with Los Angeles Metro told us that their mechanics need more total hours of training to work on the various bus types within their fleet than they would if their fleet only had buses from a single manufacturer.

Training methods varied among our selected transit agencies.[41] Two of the transit agencies we interviewed sent a more experienced mechanic to the bus manufacturer to receive “train the trainer” training, and that mechanic subsequently trained other agency mechanics. Four other agencies brought manufacturers on-site to train their mechanics.[42] For example, AC Transit officials explained that their mechanics shadowed the manufacturer’s mechanics while they conducted repairs during the first year of the bus warranty. According to those transit agency officials, their own mechanics were able to make repairs during the second warranty year. Three of our selected agencies told us they use other training methods, including structured classroom training and the use of different tools and technology. Specifically, officials from Los Angeles Metro, Mountain Line, and AC Transit described plans to integrate training simulators into their training materials to better simulate repair work.

As transit agencies install supporting infrastructure and prepare to meet the service needs for their zero-emission buses, new skills and training are also needed for a range of positions across the agency. Our selected agencies said that additional training is needed for positions such as bus operators driving such buses, depot staff who use battery chargers, dispatchers who monitor bus charge and reroute buses to meet service needs, and route planners who configure bus routes to accommodate range limitations. For example, StarMetro officials told us they have integrated training on zero-emission buses into their 8-week training program for new bus operators. They also require all operators to take an annual 8-hour refresher training course. In addition, officials with MTA and Los Angeles Metro told us that all facilities staff—not just mechanics—will also need basic high-voltage safety awareness training. At Los Angeles Metro, this training is a 4-hour in-person class that informs the staff of guidelines for high-voltage equipment such as electric buses and the charging infrastructure. See figure 7 for transit agency positions involved in the transition to zero-emission buses.

Selected Transit Agencies Face Uncertainty Around Future Staffing Needs

While identifying training needs early on is helpful during the transition planning process, FTA officials stated that FTA does not expect that all transit agencies have fully developed workforce projections since many agencies are early in their transition to zero-emission buses. Selected transit agencies’ zero-emission fleet transition plans generally described the need for new skills for their mechanics and other staff and identified the need for training to provide these skills. However, these plans did not include detailed analyses of the agencies’ current and future workforce needs and skill gaps, though the plans varied in the level of detail provided. For example, the fleet transition plan for the Transit Authority of River City in Louisville, Kentucky, states the agency plans to use bus manufacturers to provide training focused on safety, but the plan does not discuss how this will address worker skills going forward. King County Metro provided more detail in its fleet transition plan, with descriptions of the positions that will need additional training as a result of the transition and specific training topics those positions will need. When asked about future mechanic staffing projections related to transition, most of our selected agencies provided us with estimates, while other agencies were unable to make such projections.

According to the transit agencies we met with, several factors make it difficult to determine their specific skill and workforce development needs as they continue to expand their zero-emission fleets. The factors that make it difficult to determine future needs include uncertainties around bus delivery timeframes, future maintenance needs, and the expiration of bus warranties.

· Unpredictable bus delivery timelines and infrastructure upgrades. Transit agency officials told us that it is too early to know how many staff will be needed to support a zero-emission fleet and when, particularly given the long lead time and uncertainty around bus deliveries, as previously described. They noted that the recent contraction in the bus manufacturing market has created further uncertainty and additional delays. For example, officials from the Transit Authority of River City told us they ordered six buses from Novabus before the manufacturer announced in June 2023 that it was ceasing U.S. operations, and subsequently the order was transferred to Gillig, with a new estimated delivery date of November 2025.

Similar uncertainty exists with obtaining other bus components and infrastructure such as charging equipment, as well as the increased electrical capacity needed from utility companies, as discussed above. Five of the agencies we interviewed told us they struggled to coordinate the installation of electric charging infrastructure with their local utility company. For example, AC Transit officials stated that they had battery electric buses sit idle for 6 months while the local electric company upgraded the transit agency’s power grid to accommodate the newly installed chargers.

· Uncertain maintenance needs. Eight of our selected transit agencies said they were uncertain about how much maintenance—and how many mechanics—will be needed once new buses and equipment are in place. Moreover, these agencies added that the limited numbers of zero-emission buses they currently have in operation make it difficult to determine how scaling up will affect the number of mechanics ultimately needed. While information from DOT states that zero-emission buses can require less maintenance because they have fewer moving parts, three selected transit agencies provided differing views. For example, Los Angeles Metro officials stated there may be an increase in mechanics needed from the safety risk of handling high-voltage equipment.

Two bus companies we spoke with in Europe have had different experiences with the maintenance needed in their fleet transitions. For example, representatives from a London bus company, RATP Dev Transit London, told us that their company had decreased its number of mechanics because maintenance occurs less frequently. Specifically, while maintenance for diesel buses occurs every 4 weeks, it occurs every 6 weeks for battery electric buses. Because of this, RATP Dev Transit London is able to increase the ratio of mechanics to buses from one mechanic to every six diesel buses to one mechanic for every 10 battery electric buses. However, representatives from a bus company in Amsterdam, Arriva, told us that the size of their mechanic workforce has remained the same. The representatives added that company-wide, the transition to battery electric buses has required hiring more staff to fill a number of new positions that had not previously existed, such as a buyer for chargers. Additionally, Arriva had found that maintenance costs for battery electric buses are more expensive than for diesel buses.

· Uncertainty after warranty expires. Seven of our selected transit agencies transitioning to zero-emission buses have relied on some manufacturer warranty service to handle any maintenance issues beyond routine maintenance.[43] These transit agencies have identified staff with the skills needed to perform routine maintenance work to meet existing service needs. However, seven agencies do not yet have in-house experience performing unplanned maintenance given the existing warranties. Officials from two agencies told us they do not anticipate workforce skill gaps or training needs for the duration of their warranty period. Coast Transit Authority, for example, uses its own mechanics to conduct repairs on its battery electric bus, and has an extended warranty with the manufacturer, Gillig. Under that warranty, Gillig monitors the maintenance needs of the bus and notifies Coast Transit Authority when there is an issue and ships the new part with instructions for repair to the agency. Coast Transit Authority officials said they have not experienced issues with this approach because agency mechanics are sufficiently trained. However, as warranties expire and as agencies scale up their zero-emission bus fleets, gaps in agencies’ workforce capabilities could appear. For example, Los Angeles Metro officials said that they will need to recruit and train more mechanics to work on zero-emission buses because its current mechanic workforce does not have those skills.

Some transit agencies have reduced the need for training on zero-emission buses by contracting out maintenance services. For example, officials from Antelope Valley Transit Authority told us they do so rather than rely on agency mechanics. This has allowed them to shift the task of workforce development to their contractor. According to a representative from Transdev, an international transit contractor, other small agencies might choose to contract out maintenance—or even their entire transit workforce—because contractors can leverage their existing expertise to run the operation with fewer resources.

The transit agency officials we spoke with in London told us that private bus companies provide basic safety training and bus-specific training to their mechanics. They said they also rely on bus manufacturers for more complex maintenance issues that cannot be repaired by their own mechanics. These transit agency officials said they use a third-party contractor model to provide public bus services, which places the workforce development responsibility on contractors. According to Department for Transport officials in the United Kingdom, local governments generally oversee the provision of services by private bus companies that compete to win the bids for these services. For example, Transport for London officials said it contracts with a number of private bus companies, such as Go-Ahead London and RATP Dev Transit London, to provide zero-emission bus services to achieve the city’s goals to transition to a zero-emission bus fleet by 2034.

Selected Transit Agencies Are Continuing Recruiting Efforts to Address Ongoing Frontline Worker Shortages and Zero-Emission Transition Needs

As discussed earlier, transit agencies face longstanding shortages of frontline workers. Officials at seven of our selected agencies cited mechanic recruitment as an overall challenge, regardless of vehicle technology type. Further, the shortage of mechanics may increase as the competition for those with the necessary electric vehicle skills grows, according to half of the agencies we interviewed.

Generally, our selected transit agencies told us they plan to continue their existing recruitment and retention strategies to hire workers to operate and maintain their current bus fleets and will begin training them with skills specific to zero-emission buses, as needed. For example:

· Seven of our selected transit agencies are currently partnering or planning to partner with community colleges to recruit more mechanics. Other identified employment pipelines include high schools, career fairs, public advertisements, other transit agencies, and the automotive industry. Representatives from bus service companies in London told us they draw from an automotive trade school that provides some basic electrical and mechanical skills. These companies then train their mechanics, who can apply for various national certifications that demonstrate an understanding of electric vehicle safety, system repair and replacement, and diagnostics.

· Three agencies we met with fill workforce gaps for mechanics through internal promotions or by offering interested newer mechanics additional electrical safety or technical diagnostic training for zero-emission buses. For example, AC Transit officials said they offer the opportunity for employees with little to no experience to receive training to become a mechanic.

· Two of our selected transit agencies currently use an apprenticeship program, while another is exploring developing such a program. For example, King County Metro’s 2-year mechanic apprenticeship program includes paid, specialized on-the-job and classroom training. Upon completion, the apprentice is hired by King County Metro as a full-time mechanic. Also, officials from SunLine told us they are developing their own apprenticeship program.

|

Unions Can Play an Important Role in Worker Recruitment and Retention, According to Transit Officials According to transit agencies that we met with, unions can be important partners to transit agencies during the transition to zero-emission buses. Eight of the selected transit agencies we spoke with have unions. Transit agency officials cited various examples of the assistance unions have provided, including early input on potential training materials and help establishing apprenticeship programs and career ladders to retain and promote workers. For example, SunLine Transit Agency serving Coachella Valley, California, is working with its union and a community college to establish an apprenticeship program. AC Transit officials stated they work with their union partners on career ladders to address recruitment and retention of mechanics. Additionally, U.S. Department of Labor announced that a major transit union was awarded an Apprenticeship Building America program grant in July 2024 to focus on bus operator and mechanic apprenticeship programs for zero-emission buses. Source: GAO analysis of information from selected transit agencies and Department of Labor. │ GAO‑25‑106921 |

In addition, officials from seven of our selected transit agencies said they have focused on attracting new workers by highlighting their overall benefits packages, but retention and hiring remains difficult. Specifically, officials at these selected transit agencies told us they struggled to retain or attract mechanics with zero-emission bus skills. They noted that they were unable to compete with salaries offered by bus manufacturers, car manufacturing plants, and other private companies.

Recent FTA-Led Activities Aim to Assist Transit Agencies’ Preparation of Their Workforces for Zero-Emission Buses

FTA’s Transit Workforce Center Is a Resource for Transit Agencies

In 2021, FTA established the Transit Workforce Center (TWC) to provide direct technical assistance to transit agencies to advance workforce development. This center aims to assist agencies in addressing the ongoing national transit worker shortage broadly, as well as workforce issues related to the transition to zero-emission buses. According to FTA officials, the agency has awarded $12.5 million to the International Transportation Learning Center—a national transit workforce nonprofit organization—to support and manage the TWC under a cooperative agreement. In part, the International Transportation Learning Center’s TWC assists transit agencies to train and retain frontline transit workers and provides recruitment-focused activities through 2026.

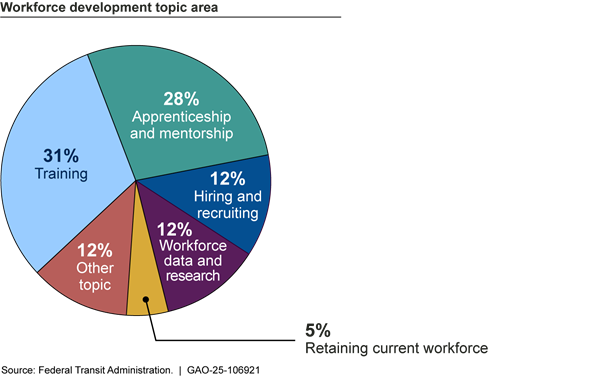

TWC provides technical assistance, workforce strategic planning, and targeted training development, which it tracks and reports to FTA on a quarterly basis. FTA officials stated that as of June 2024, TWC had resolved 570 targeted technical assistance requests from 361 transit locations (both from transit agencies and unions). As an example of the types of technical assistance requests received, FTA officials stated that in the third quarter of fiscal year 2024, TWC responded to 42 requests covering topic areas including apprenticeships, training, recruitment, and workforce retention (see fig. 8).

Figure 8: The Transit Workforce Center’s Technical Assistance in the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2024

While FTA officials told us they direct to TWC all transit agency requests for support related to workforce development, TWC representatives indicated that they have some capacity limitations. Specifically, because of the center’s size and budget, they said they do not have the capacity and resources to individually help each transit agency address their specific workforce gaps and training needs. They noted that TWC receives more requests for assistance than their 15-member staff can handle. Nonetheless, the representatives noted that by posting guidance and resources on the TWC website, transit agencies can access and adapt these resources to suit their agency’s needs. According to FTA officials, TWC’s online resource center, which can be filtered by topic such as zero-emission buses, contains 324 resources and had been viewed by 2,551 users in the third quarter of fiscal year 2024.

In the last 2 years, TWC created resources including case studies, training materials, and research reports, some of which are specific to zero-emission workforce needs. For example, in November 2023, TWC released its Battery Electric Bus Familiarization Course, a 2-day course for technicians that provides an overview of electrical safety and battery-charging technologies. According to TWC representatives, they offered this course in May 2024 and plan to offer additional trainings of the course, which is also publicly available for download and may be edited by transit agencies for customized content and training. TWC representatives stated that they worked with five transit agencies to pilot this course and are focused on disseminating it to other agencies via TWC’s website or at transit conferences. Additionally, TWC created a transit frontline worker recruitment toolkit, established a peer network to share information on apprenticeship programs, and built a transit workforce data dashboard.

FTA Is Supporting Multi-Pronged Efforts to Implement Strategic Workforce Plan Goals

While not all specific to zero-emission buses, FTA has a number of additional efforts underway to improve transit agencies’ ability to develop the diverse transit workforce needed today and in the future.[44] For example, FTA officials told us they are actively supporting transit agencies with (1) funding, (2) technical assistance centers, (3) research, and (4) consideration of standards. FTA is also coordinating with other federal agencies to support zero-emission technology deployment. These efforts collectively aim to address workforce challenges faced by transit agencies.

· Funding. FTA has provided workforce development funding directly to transit agencies, which officials estimated at $43 million in 2022, $49 million in 2023, and $41 million in 2024. These amounts account for the 5 percent of grants related to zero-emission vehicle or associated infrastructure projects that recipients must use for workforce development and training under the agency’s Low or No Emission Grant Program and Buses and Bus Facilities Competitive Grant Program. As previously mentioned, recipients must obligate these programs’ grants, which include these workforce development funds, within 4 fiscal years, which, according to FTA, begins with the fiscal year in which the award was announced. The workforce development funding must be used to carry out the activities outlined in the workforce section of their zero-emission transition plans. Eligible activities include developing apprenticeships, on-the-job training, and instructional training for transit operations and maintenance jobs. Selected transit agency officials we spoke with plan to use some of these funds for training. For example, AC Transit will use part of its fiscal year 2024 Low or No Emission Grant Program funding for a workforce development program to help train staff on zero-emission bus technologies. According to FTA officials, workforce development funds are included in transit agencies’ grant budgets, which FTA monitors as part of its normal oversight procedures.

· Technical assistance centers. According to officials, FTA has funded its technical assistance centers—including TWC—with a total of approximately $30 million to provide training, conduct research, and work directly with transit agencies on workforce development. TWC and the National Transit Institute (NTI) provide workforce development assistance for transit agencies. NTI develops and conducts education programs for transit employees, and, until recently, NTI trainings had been focused on transit administrators rather than frontline workers. According to FTA officials, NTI’s partnership with TWC in offering the Battery Electric Bus Familiarization Course in May 2024 trained an initial class of about 12 technicians. An NTI representative told us that they had not previously offered any training specific to zero-emission buses, though they plan to develop new courses in response to demand from transit agencies and FTA.

· Research. FTA sponsored several relevant studies on workforce development and zero-emission buses, including a guidebook and best practices published in 2023 on the deployment of battery electric buses, procurement and maintenance, and safety.[45] FTA also supported additional transit industry research efforts in 2023. For example, FTA participated in APTA’s development of zero-emission bus maintenance training standards and the Transit Cooperative Research Program’s study on bus operator workforce management.[46]

· Consideration of standards. FTA also entered into a cooperative agreement with APTA in August 2023 to lead a multi-organizational team to consider various topics, including voluntary safety, interoperability, and data integration standards for zero-emission buses. According to FTA officials, the U.S. transit industry has not historically required standards or certifications for its workforce and maintenance, preferring to rely on voluntary standards. According to these officials, there are no current plans to make standards required for transit agencies. FTA officials stated that the agency would not propose a mandatory federal safety standard unless there were injury or accident data or other evidence that demonstrated a need for such a standard.

We found that safety standards varied for workers on zero-emission buses in the Netherlands and United Kingdom. According to representatives for a bus company, the Netherlands has a certification for working safely on electric vehicles that is part of the training for workers maintaining battery electric buses.[47] Representatives from all four of the bus and bus maintenance companies in the Netherlands that we spoke with told us that they ensure their workers have this certification, which demonstrates compliance with national occupational health and safety regulations. Representatives from two companies explained that separate training companies can be contracted to provide the training and certification. By contrast, London transit officials and representatives from two bus companies operating in the United Kingdom told us their country does not have required worker training standards for zero-emission buses. London transportation officials stated that neither they nor the national government have workforce standards specific to zero-emission buses, beyond compliance with general labor laws. They noted that it is up to individual bus companies contracted to provide transit bus services to determine their workforce training.

In addition to directly supporting the transit agencies through these efforts, FTA coordinates with other federal agencies to support the deployment of zero-emission vehicle technology. For example, FTA partners with the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (Joint Office) to offer technical assistance to transit agencies that are planning for a transition to zero-emission buses.[48] Specifically, for the Joint Office’s Clean Bus Planning Awards program, FTA officials stated that TWC will be providing the workforce technical assistance while the Joint Office leads the rest of the transition planning support.

FTA officials told us they also coordinate with the Department of Labor to promote transit workforce opportunities and plan to continue doing so. These efforts, like those of our selected transit agencies, focus on addressing broader transit workforce shortages rather than efforts specific to zero-emission buses. FTA refers transit agencies to resources to support workforce training programs, such as through the Department of Labor’s Building Pathways to Infrastructure Jobs Grant Program.[49] FTA officials stated that TWC will host at least five regional meetings with the Department of Labor and other stakeholders in fiscal year 2024 through 2025 to build partnerships to support the transit workforce.

FTA officials also told us that they are working to align their current workforce development efforts with the goals in the National Transit Workforce Development Strategic Plan 2023-2028. For example, FTA aligned TWC’s efforts in developing a toolkit for workforce recruitment campaigns with the strategic plan’s recruitment and outreach goal. Additionally, according to FTA officials, technical assistance provided through the Joint Office will also satisfy deliverables and count toward metrics in the strategic plan. FTA officials stated they are determining the next steps and timeframes for reviewing implementation progress toward the workforce strategic plan, as it is new, while also working to expand and create new efforts to address plan goals. Officials added that they have developed an implementation tracker and are monitoring progress toward key objectives.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Transportation and Labor for review and comment. The Departments of Transportation and Labor provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation, the Secretary of Labor, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-2834 or vonaha@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Andrew Von Ah

Director, Physical Infrastructure

House Report 117-402, incorporated by reference into the Explanatory Statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 includes a provision for GAO to review workforce development needs as transit agencies transition to zero-emission vehicles.[50] This report describes (1) the status of transit agencies’ transition to low- and zero-emission bus fleets and any challenges they may face meeting transition goals over the next decade; (2) skill- and workforce-development needs of transit agencies and actions selected transit agencies are taking to address workforce gaps; and (3) actions taken by the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) to assist transit agencies in preparing their workforces for zero-emission buses.

This report builds on our 2019 report on the sufficiency of the transit workforce, including FTA’s role in supporting transit agencies’ efforts to develop their workforces. At that time, we made recommendations for FTA to improve its strategic planning, and FTA has since implemented all three of our recommendations.[51]

To address all three objectives, we interviewed officials from FTA within the Department of Transportation (DOT), the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation, the Department of Labor, and 18 transit stakeholders listed in table 1. We interviewed these stakeholders on the transition to zero-emission buses, including uncertainties and challenges. We identified these stakeholders through our prior work on transit workforce development, as well as recommendations from other stakeholders.

|

Amalgamated Transit Union (transit union) |

|

American Public Transportation Association (transit association) |

|

BYD Motors (bus manufacturer) |

|

California Transit Training Consortium (technical assistance provider) |

|

CALSTART (technical assistance provider) |

|

Center for Transportation and the Environment (technical assistance provider) |

|

Community Transportation Association of America (transit association) |

|

ENC (bus manufacturer) |

|

Forest River, Inc. (bus manufacturer) |

|

Gillig (bus manufacturer) |

|

International Association of Public Transport (transit association) |

|

International Transportation Learning Center / Transit Workforce Center (technical assistance provider) |

|

National Center for Applied Transit Technology (technical assistance provider) |

|

National Institute for Automotive Service Excellence (certification provider) |

|

National Transit Institute (technical assistance provider) |

|

New Flyer (bus manufacturer) |

|

Transdev (bus contractor) |

|

Transport Workers Union of America (transit union) |

Source: GAO. │ GAO‑25‑106921

To describe the status of transit agencies’ transition to zero-emission vehicles, we reviewed applicable statutes and regulations and analyzed data on the active nationwide bus fleet from FTA’s 2023 National Transit Database—reported by transit agencies at the end of their 2022 fiscal year—which were the most current data available at the time of our review.[52] To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed information published by FTA about how these data are validated and requested additional information from the agency specifically about using these data to describe the status of the transition to zero-emission buses. We determined the data in the National Transit Database to be sufficiently reliable for our purposes of describing the number of zero-emission buses operated by large urban transit agencies.

For the purposes of this report, we focused on zero-emission buses rather than low-emission buses because zero-emission buses generally use newer technologies and may pose greater workforce challenges to agencies adopting them. Also, we defined “transit buses” as (1) buses, including articulated buses, buses, over-the-road buses, and double-decker buses; (2) trolleybuses operating on fixed overhead lines; and (3) cutaways (i.e., a bus body mounted on the chassis of a van or light-duty truck) and vans, both of which are commonly used by rural transit agencies or for paratransit service. We excluded non-bus transit vehicles such as school buses, minivans, sport utility vehicles, and automobiles because our primary interest is on the workforce needed for zero-emission bus technology. Moreover, to describe the transition to zero-emission buses, we focused on battery electric buses and hydrogen fuel cell electric buses, because these newer technologies require a significant change in worker skillsets and operations for transit agencies. For that reason, we did not focus on trolleybuses, which are operated by five agencies nationwide using more established technology.

To provide illustrative examples, we interviewed and obtained data from 10 selected transit agencies about their experiences operating low- or zero-emission buses, plans to increase the number of such buses in their respective fleets over the next 10 years, and current or anticipated challenges. The information provided by the 10 selected transit agencies is not generalizable to all transit agencies. We selected from among the population of transit agencies that had received grants under the Low or No Emission Grant Program (49 U.S.C. 5339(c)) and the Bus and Bus Facilities Competitive Grant Program (49 U.S.C. 5339(b)) for fiscal years 2022 and 2023. We also selected Antelope Valley Transit Authority in Lancaster, California, because it had already completed the transition to zero-emission buses. As an additional selection factor, we considered transit agencies that were highlighted to us as leading the transition to zero-emission buses by transit stakeholders we spoke with. We also considered the location of agencies to reflect a range of those from various states and service-area population sizes to capture a range of perspectives. Finally, we also considered the propulsion technology type, to include transit agencies that operate battery electric buses and hydrogen fuel cell electric buses, as well as one agency transitioning to low-emission technology. Given our selection criteria, we did not include agencies that do not have plans to transition to low- or zero-emission buses. Table 2 lists the 10 selected transit agencies we interviewed.

|

Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District; Oakland, California |

|

Antelope Valley Transit Authority; Lancaster, California |

|

Coast Transit Authority; Gulfport, Mississippi |

|

King County Metro; Seattle, Washington |

|

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority; Los Angeles, California |

|

Metropolitan Transportation Authority; New York, New York |

|

Mountain Line; Missoula, Montana |

|

StarMetro; Tallahassee, Florida |

|

SunLine Transit Agency; Coachella Valley, California |

|

Transit Authority of River City; Louisville, Kentucky |

Source: GAO. │ GAO‑25‑106921

To describe how our selected agencies plan to transition their fleet, we reviewed transition documentation, such as the agencies’ bus fleet transition plans that they submitted to FTA as part of their applications for Low or No Emission Grant funding. We also interviewed representatives from these agencies for perspectives on the transition, including any uncertainties and challenges, and obtained data on the composition of their current bus fleet and projected growth of zero- and low-emission buses over the next 10 years.

To identify the skill and workforce development needs of transit agencies transitioning to zero-emission buses, we reviewed applicable statutes and transit industry reports and documents, including reports from the American Public Transportation Association (APTA), and interviewed transit stakeholders such as technical assistance providers, transit unions, bus manufacturers (listed in table 1), and our 10 selected transit agencies on training materials created by these agencies and bus manufacturers. We also interviewed these selected transit agencies about actions they are taking to address gaps in the skill and workforce development needs.

To help inform our research on public transportation providers that are substantially farther along in their zero-emission bus transition with high numbers of such buses in operation, we identified and interviewed transit stakeholders in Amsterdam, the Netherlands and London, United Kingdom, on their workforce transitions and lessons learned. The information we obtained is not generalizable to all transit stakeholders in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Because the transit systems in these cities are further along in their transition to zero-emission fleets, their perspectives provide additional insight into the transition process. Table 3 lists the transit entities we interviewed from the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

|

Arriva Netherlands |

|

|

|

GVB |

|

|

Schiphol Infrastructure |

|

|

Transdev The Netherlands |

|

United Kingdom |

Go-Ahead London |

|

|

RATP Dev Transit London |

|

|

Transport for London |

|

|

United Kingdom Department for Transport |

Source: GAO. │ GAO‑25‑106921

To describe FTA’s and other federal agencies’ actions to assist transit agencies in preparing their workforces, we reviewed applicable statutes and documents and interviewed officials from FTA and other federal agencies, as well as FTA’s technical assistance partners involved in workforce development, including the Transit Workforce Center. For example, to describe the status of efforts to address zero-emission bus transition goals, we reviewed FTA’s National Transit Workforce Strategic Plan 2023 to 2028, and interviewed FTA officials on their progress implementing the Plan.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Our review of plans developed by our 10 selected transit agencies and information provided by agency officials found that each agency plans to adjust their fleets over the next decade to increase the number of low- or zero-emission buses, but their approaches and timelines for completing their transitions vary.

Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District in Oakland, California

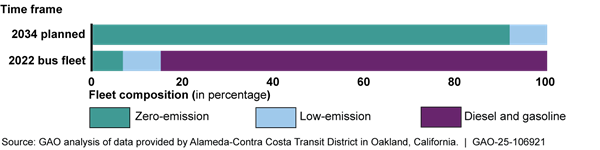

Since 2020, Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District (AC Transit) has committed to fully transitioning its bus fleet to zero-emissions by 2040. According to agency data from the end of 2022, AC Transit has 636 buses, of which 35 buses are hydrogen fuel cell electric and 7 buses are battery electric. AC Transit also has 53 low-emission hybrid buses, but according to the data provided, the agency will not be purchasing any additional hybrid buses. By 2034, AC Transit plans to operate 413 hydrogen fuel cell electric buses and 178 battery electric buses, comprising most of its bus fleet (see fig. 9).

According to the AC Transit fleet transition plan, the agency is deploying both hydrogen fuel cell electric buses and battery electric buses as it continues to evaluate the most reliable long-term operational range, financial efficiency, and sustainability of the two technologies. Additionally, the plan states that operating both technologies offers AC Transit some resiliency advantages during electricity outages or when hydrogen fuel may be unavailable. The plan noted that both propulsion technologies can have scale-up challenges, and the mix of buses will be adjusted as technology advances.

Figure 9: Composition of Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District’s Current and Planned Bus Fleet by Fuel or Propulsion Type, as of December 2022

Antelope Valley Transit Authority in Lancaster, California