WEAPON SYSTEMS ACQUISITION

DOD Needs Better Planning to Attain Benefits of Modular Open Systems

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106931. For more information, contact Shelby S. Oakley at (202) 512-4841 or OakleyS@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106931, a report to congressional committees

DOD Needs Better Planning to Attain Benefits of Modular Open Systems

Why GAO Did This Study

A MOSA enables weapon programs to better respond to changing threats by allowing them to replace components more easily. Further, a MOSA can help address concerns like high weapon system sustainment costs that GAO has reported on.

House and Senate reports include provisions for GAO to review DOD’s use of MOSAs. This report assesses the extent to which (1) programs implemented MOSAs and why; (2) programs and portfolios planned for MOSAs; (3) the military departments invested in necessary resources for MOSAs; and (4) DOD developed policy, regulations, and guidance for MOSAs.

GAO reviewed planning documents for 20 acquisition programs that started after relevant laws were passed in 2016. GAO selected the programs based on their acquisition approach and military service. GAO also reviewed policy and guidance documents and interviewed DOD and military department officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 14 recommendations to DOD, including that it develop a process to analyze MOSA costs and benefits; improve military department processes for ensuring quality MOSA planning documents and for coordinating MOSA implementation across programs; and address gaps in MOSA policy and guidance. DOD concurred with these recommendations.

What GAO Found

A modular open systems approach (MOSA) is a strategy that can help the Department of Defense (DOD) design weapon systems that take less time and money to sustain and upgrade. Recent legislation requires acquisition programs to implement a MOSA to the maximum extent practicable. GAO found that 14 of the 20 programs it reviewed reported implementing a MOSA to at least some extent. Other programs cited barriers to doing so, such as added cost and time to conduct related design work. While a MOSA has potential benefits, it may also require programs to conduct additional planning, such as to ensure they address cybersecurity aspects related to a MOSA.

However, none of the 20 programs GAO reviewed conducted a formal analysis of costs and benefits for a MOSA because DOD’s policy does not explicitly require one. As GAO reported in March 2020, program officials often focus on reducing acquisition time and costs. Unless required to consider the costs and benefits of a MOSA, officials may overlook long-term MOSA benefits.

Further, most programs did not address all key MOSA planning elements in acquisition documents, in part, because the military departments did not take effective steps to ensure they did so. As a result, programs may not be well-positioned to integrate a MOSA into key investment decisions early in the life of the program. Also, DOD’s process for coordinating MOSAs across portfolios does not ensure the level of collaboration needed to achieve potential benefits such as lower costs from using common components across programs.

The military departments are statutorily required to ensure availability of certain resources and expertise related to MOSA implementation. However, they have yet to assess their departments’ MOSA needs or determine how resources should be aligned across their respective departments. Until they do this, programs risk having insufficient resources and expertise to achieve the potential benefits of a MOSA.

DOD has updated some acquisition and engineering policies and is drafting regulations and guidance to address MOSAs. But gaps remain that could hinder MOSA implementation. For example, DOD policy does not address how MOSA requirements apply to programs using the middle tier of acquisition pathway—those intending to complete rapid prototyping or fielding in 5 years or less.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ACAT |

acquisition category |

|

CAPE |

Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

MDAP |

major defense acquisition program |

|

MOSA |

modular open systems approach |

|

MTA |

middle tier of acquisition |

|

NDAA |

National Defense Authorization Act |

|

OSD |

Office of the Secretary of Defense |

|

PEO |

program executive officer |

|

USD(A&S) |

Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment |

|

USD(R&E) |

Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 22, 2025

Congressional Committees

U.S. adversaries are fielding technically advanced weapons at an accelerating pace. At the same time, the Department of Defense (DOD) continues to struggle with fielding delays for new weapon systems, which results in these systems becoming less relevant as time elapses from when their original requirements were developed. DOD’s practice of frequently developing weapon systems that can only be updated or maintained by a single contractor further complicates the problem by limiting opportunities for the integration of cutting-edge technologies from new vendors or cost-saving competition to sustain weapon systems.

Legislation enacted over the past several years required DOD to change the way it buys and designs weapon systems by implementing a modular open systems approach (MOSA) to the maximum extent practicable.[1] A MOSA, which includes a modular design and standard interfaces, allows programs to easily replace components of a product. This approach allows the product to be competitively upgraded with new, improved components that can be made by a greater variety of suppliers. It may also help address concerns we have previously reported on about rising sustainment costs for programs like the F-35 and the Navy’s shipbuilding portfolio by increasing competition for sustainment among potential vendors.[2] Otherwise, these costs may limit DOD’s ability to afford the force structure it expects to need in future conflicts.

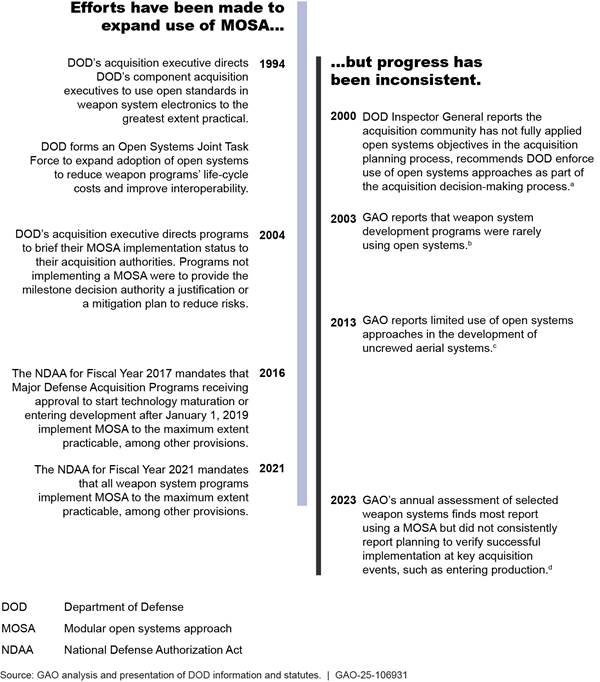

The benefits of designing weapon systems with a MOSA have been long established. DOD issued policy encouraging weapon system programs to use open systems specifications to acquire weapon systems electronics 30 years ago. However, we reported in 2023 that implementation of a MOSA in acquisition programs was inconsistent. We found that programs implementing a MOSA did not consistently plan to verify successful implementation of the approach before key points in the acquisition process, such as before beginning production.[3]

The House and Senate committee reports accompanying bills for the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2023 include provisions for GAO to review DOD’s use of MOSAs in developing weapon systems.[4] This report assesses the extent to which (1) selected acquisition programs reported implementing a MOSA and the factors contributing to those decisions, including the use of cost-benefit analysis; (2) DOD has planned for MOSA implementation at the program and portfolio levels; (3) the military departments have identified and invested in necessary resources to implement MOSA; and (4) DOD has developed policy, regulations, and guidance for MOSAs.

To assess the extent to which selected acquisition programs reported implementing MOSA and the factors contributing to those decisions, we reviewed acquisition documentation relevant to MOSAs and interviewed officials among 20 selected programs. These programs are following one of two acquisition pathways: (1) the major capability acquisition pathway, used by major defense acquisition programs (MDAP), and (2) the middle tier of acquisition (MTA) pathway. We selected programs for review based on the following criteria:

· MDAPs (9): We selected unclassified programs that entered technology or system development after January 1, 2019, the date after which the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2017 required all MDAPs obtaining approval to enter technology or system development to implement a MOSA to the maximum extent practicable.[5]

· MTA programs (11): We selected up to three of the most recently initiated programs currently using this pathway from each military service (Army, Air Force, Space Force, and Navy) that DOD reported in its annual submission to Congress in support of the President’s budget for fiscal year 2024.[6]

To assess the use of cost-benefit analysis to inform programs’ MOSA decisions, we reviewed available documentation related to cost-benefit analyses conducted by all 20 acquisition programs we reviewed. We assessed whether programs completed these analyses as recommended by best practices in cost estimating to help control life-cycle costs.[7] We also reviewed DOD policy to determine the extent to which programs and acquisition organizations are required to assess MOSA costs and benefits to inform decisions related to MOSA implementation.

To assess the extent to which DOD has planned for MOSA implementation at the program level, we collected and reviewed key planning documents for our selected programs. These documents include systems engineering plans, acquisition strategies, and requests for proposals. We assessed the extent to which these documents addressed MOSA provisions in law and DOD policy and guidance. To assess the effectiveness of DOD’s planning at the portfolio level, we obtained written responses from a subset of the organizations’ chief systems engineers responsible for our selected programs on the extent to which their offices have established formal MOSA coordination processes for their portfolios of responsibility. We compared these responses to leading practices for portfolio management.

To assess the extent to which the military departments identified and invested in necessary resources to implement MOSA, we requested plans from the military departments related to funding MOSA implementation. We also met with acquisition officials at the program office, military department, and Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) levels to obtain their perspectives on the necessary resources to implement MOSAs. We also discussed how the military departments had assessed and planned to meet these resource needs. We compared the military departments’ efforts to plan for MOSA-related resources to our past work on planning to achieve organizational goals.

To assess DOD’s progress in developing MOSA policy, regulations, and guidance, we collected and reviewed OSD and military department policy and guidance documents and documents related to relevant regulations. We assessed whether military departments issued guidance that addresses legal requirements, including addressing how MOSA is to be documented in acquisition program documentation, considerations regarding MOSA at acquisition milestones, and related topics. We also met with officials responsible for these documents.

Appendix I provides additional information on our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

MOSA Definition

A MOSA for weapon systems includes a combination of engineering and business practices in which weapons systems are designed with modular components that are linked by clearly defined system interfaces. The components can be acquired from independent vendors.[8] Modern weapon systems consist of a major system platform—like an aircraft—that is composed of major system components like engines and optical sensors.[9] The connections between the platform’s components are referred to as interfaces.

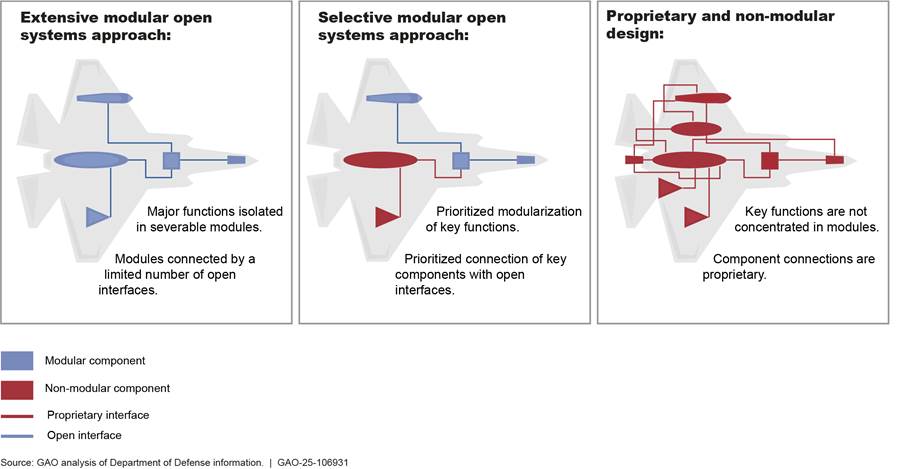

Systems designed with a MOSA use a modular design for their components and connect these components via open interfaces.

· A modular system design isolates functions in individual component modules. This design makes the system easier to develop, maintain, and modify because components can be changed without majorly affecting the remainder of the system.

· MOSA systems use widely supported standards for the key interfaces, or connections between the components. Interface standards specify the physical, power, data, and other connections between components. All interfaces in a system do not need to use open standards for a system to be considered “open,” as it can be costly and impractical to manage hundreds or thousands of interfaces within a system. Rather, programs should identify open standards at key interfaces between the modules that are likely to change, may frequently fail or need to be replaced, or are needed for interoperability.

When open standards are not available, programs pursuing a MOSA can obtain appropriate data rights to their components’ interfaces. Doing so could enable the government to competitively award contracts for modification and sustainment of weapon systems. Figure 1 illustrates a range of MOSA approaches that a program could select for a notional system.

Potential Benefits of a MOSA

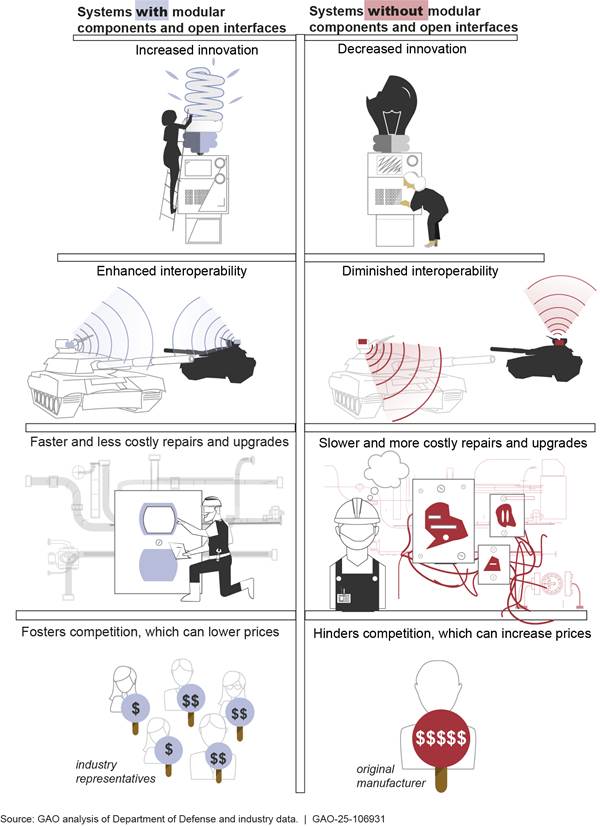

An open system enables DOD to acquire warfighting capabilities with more flexibility and opportunities for competition by allowing independent suppliers to build components that can plug into the existing system through the open connections. We have previously reported on the benefits of a MOSA for weapons programs. These include the potential to reduce operating and sustainment costs—which account for approximately 70 percent of a weapon system’s total life-cycle cost.[10] For example, in a 2021 review of DOD’s efforts to develop new, alternative navigation technologies, we found that DOD was leveraging a common MOSA to standardize the common elements across the individual military services’ reference architectures.[11] Figure 2 illustrates potential benefits associated with a MOSA as opposed to systems that do not use modular components or open interfaces.

Figure 2: Potential Benefits of a Modular Open Systems Approach versus a System Not Using Such an Approach

Acquisition program officials noted there are some potential disadvantages to pursuing a MOSA. For example, publicly available open interfaces may help adversaries identify and exploit cyber vulnerabilities. Thus, using a MOSA may require additional planning to ensure cybersecurity needs are addressed. Further, a 2023 DOD survey found responding programs noted that a MOSA was costly to implement on pre-existing systems because it would require additional engineering costs to modify the design and acquire interface data rights.

Many consumer products, including U.S. appliances, personal computers, and smartphones, are considered open systems because they use widely available hardware and software standards at key interfaces. For example, U.S. appliances are designed to use a particular wall socket standard, so that they can plug into any power outlet without consumers needing to worry about which brand of product is compatible in their homes. This gives customers more choices to best meet their needs and helps keep prices low by fostering market competition.

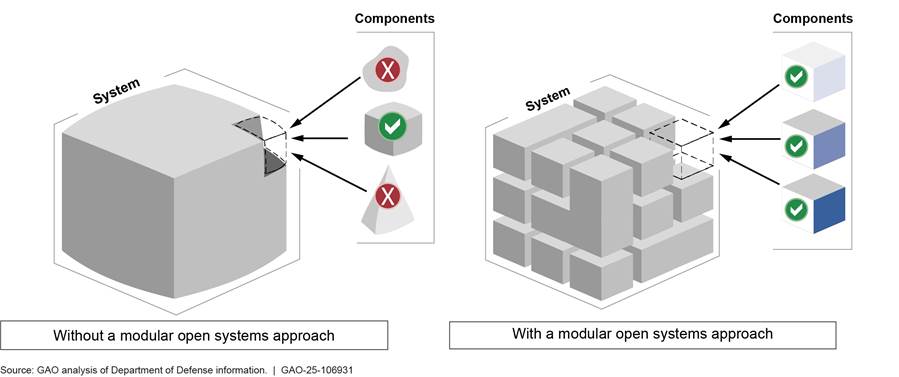

Similarly, a MOSA can allow DOD weapon system programs to gain efficiencies from competition. Although a MOSA can require more planning and investment in the weapons system development phase, it is intended to enable programs to incorporate new components from additional contractors. These benefits apply both for technology upgrades and to facilitate opportunities for competition for sustainment activities. Figure 3 illustrates how key components in a MOSA can allow a wider variety of components to meet mission needs.

A MOSA can also enable DOD programs to achieve the kind of rapid product development demonstrated by leading commercial companies. In our 2023 report on the product development practices of leading companies, we found they use an iterative process to design, validate, and deliver complex products, such as combined networks of hardware and software—referred to as cyber-physical systems—with speed.[12] These companies focus on first delivering a minimal viable product, a product with the minimum capabilities needed for customers to recognize value and that can be followed by successive updates. Systems with modular designs and open interfaces will be better positioned to accept upgrades rapidly and affordably as part of future iterations.

History of MOSA Implementation at DOD

MOSA is not a new concept in DOD’s weapon system acquisition. However, multiple efforts in legislation and DOD policy over the past 30 years to expand the use of MOSA have yet to yield consistent implementation, as shown in figure 4.

aDepartment of Defense, Office of the Inspector General, Use of An Open Systems Approach for Weapon Systems, Report No. D-2000-149 (Arlington, Virginia: June 14, 2000).

bGAO, Best Practices: Setting Requirements Differently Could Reduce Weapon Systems’ Total Ownership Costs, GAO‑03‑57 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 11, 2003).

cGAO, Defense Acquisitions: DOD Efforts to Adopt Open Systems for Its Unmanned Aircraft Systems Have Progressed Slowly, GAO‑13‑651 (Washington, D.C.: July 31, 2013).

dGAO, Weapon Systems Annual Assessment: Programs Are Not Consistently Implementing Practices That Can Help Accelerate Acquisitions, GAO‑23‑106059 (Washington, D.C.: June 8, 2023).

For additional details on MOSA legislation, see appendix II.

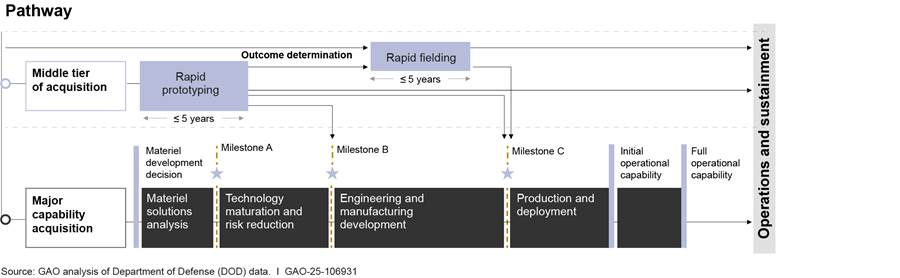

DOD Acquisition Pathways

DOD generally acquires its weapon systems through a management process known as the Defense Acquisition System, governed by the overarching principles and procedures described in DOD Directive 5000.01 and DOD Instruction 5000.02.[13] DOD Instruction 5000.02 establishes the Adaptive Acquisition Framework to manage DOD acquisition programs. The framework is composed of six acquisition pathways, each with processes, reviews, documentation requirements, and metrics that program managers can match to the characteristics and risk profile of the capability being acquired.[14] The two that are most relevant for this report are:

· Major capability acquisition: supports complex acquisitions, involving the phases of technology development, system development, and production;

· MTA: includes expedited paths for rapid prototyping and rapid fielding, each of which is to be completed within 5 years of the program start date.

Figure 5 shows the major capability acquisition and MTA pathways and associated decision points.

Major Capability Acquisition Pathway

Under DOD Instruction 5000.02, DOD’s major capability acquisition pathway is designed to support certain complex acquisitions such as MDAPs.[15] DOD Instruction 5000.85 established the policy and prescribed procedures that guide acquisition programs using this pathway. Within this pathway, programs generally proceed through four phases:

· technology maturation and risk reduction, starting with milestone A;

· engineering and manufacturing development, starting with milestone B;

· production and deployment, starting with milestone C; and

· operations and sustainment, generally starting after full operational capability is achieved.

In this report, we refer to these four phases as technology development, system development, production, and sustainment.

MTA Pathway

The NDAA for Fiscal Year 2016 required DOD to establish guidance for an alternative acquisition process, now referred to as the middle tier of acquisition, for programs intended to be completed in a period of 2 to 5 years.[16] In December 2019, DOD issued Instruction 5000.80, Operation of the Middle Tier of Acquisition. This instruction formally established the department’s MTA policy, assigned responsibilities, and prescribed procedures for the management of the MTA rapid prototyping and rapid fielding paths. The policy states that the MTA pathway is intended to deliver capabilities with a level of maturity that allows them to be rapidly prototyped within an acquisition program or fielded within 5 years of MTA program start. DOD Instruction 5000.80 also outlines the distinctions between the two MTA paths as described in statute:

· The rapid prototyping path’s objective is to field a prototype that meets defined requirements, which can be demonstrated in an operational environment and provide for residual operational capability within 5 years of the MTA program start date.[17]

· The rapid fielding path’s objective is to begin production of a new or upgraded system with minimal development within 6 months and complete fielding within 5 years of the MTA program start date.[18]

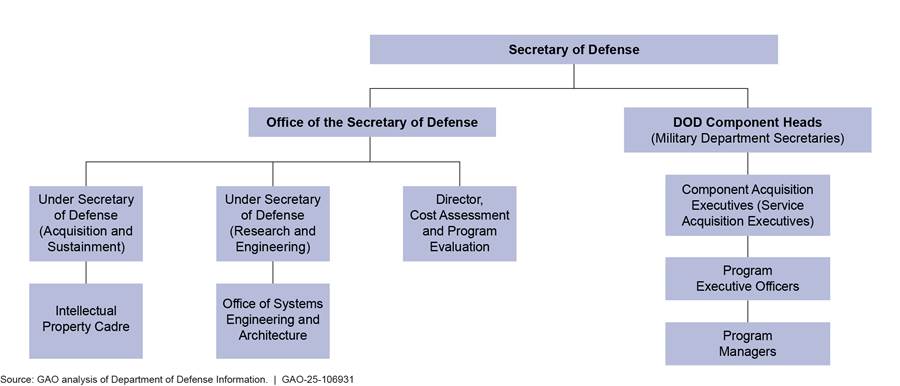

Organizations with Key Roles Pertaining to MOSA

Oversight of the department’s costliest weapon systems is shared between several entities within OSD and the military departments. Entities within OSD are responsible for overarching oversight of weapon systems across the department. This oversight includes developing policies and supervising all elements of DOD related to acquisition and sustainment; providing capabilities to enable reporting and data analysis; conducting or approving independent cost estimates and cost analyses; and overseeing operational and live fire tests and evaluations.

Regarding MOSA implementation, the following offices within OSD have key roles:

· The Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USD(R&E)) is generally responsible for developing MOSA policy and advancing workforce competency. Its efforts to date include the incorporation of MOSA in the November 2020 DOD Instruction 5000.88 and systems engineering guidebooks. USD R&E also chairs the Modular Open Systems Working Group. The working group, which includes MOSA subject matter experts from across OSD and the military departments, collaborates on MOSA promotion activities like new policy, guidance, and trainings.

· The Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (USD(A&S)) is generally responsible for issuing policy on the operation of the Defense Acquisition System, including the major capability acquisition and MTA pathways, and for overseeing acquisition programs for which it is the milestone decision authority.[19] Within this organization is the Intellectual Property Cadre, an organization of intellectual property acquisition and licensing experts, which provides oversight and coordination on all of DOD’s intellectual property acquisition and licensing policy and procedures. The cadre assists programs in developing their approaches to soliciting and negotiating contract provisions for necessary intellectual property.

· The Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) conducts or approves independent cost estimates, and cost analyses covering the life cycle of MDAPs, in support of milestone reviews, sustainment reviews, congressional certifications, and budget requests. CAPE also advises USD(A&S) on schedule, resource allocation, affordability, systems analysis, cost estimation, and the performance implications of proposed MTA programs; and establishes policies and prescribes procedures for MTA cost data and cost estimates, as appropriate.

The Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System—the process by which requirements for new performance capabilities shared jointly across military services are reviewed and validated—also has a role in shaping MOSAs. The manual for this process requires the authors of proposed requirements to briefly describe in the capability development document whether the system being designed plans to use a MOSA, including integration of capabilities developed within the system and plan for evolution of capabilities that will be added, removed, or replaced in future increments. It also states requirement authors should discuss how MOSA is being used to enable flexibility in critical technology areas.[20]

At the military department level, the component acquisition executives, also referred to as the service acquisition executives, are responsible for implementing DOD acquisition policy within their respective departments and serve as the milestone decision authority for most MDAPs. Service acquisition executives are also decision authorities for programs using the MTA pathway, with some exceptions. Marine Corps acquisition programs are under the authority of the Navy’s service acquisition executive. Space Force acquisition programs are under the authority of the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Space Acquisition and Integration.

Below the milestone decision authority level, program executive officers (PEO) oversee portfolios of programs. According to DOD policy, a PEO is responsible for delivering an integrated suite of mission-effective capability to the warfighter. DOD policy further states that PEOs are expected to do this by balancing risk, cost, schedule, performance, interoperability, sustainability, and affordability.[21] Appendix III provides more detailed overviews of roles and responsibilities for DOD and military department officials in weapons systems acquisitions.

Oversight Process for MOSA Implementation

Military department acquisition and engineering officials oversee acquisition programs’ implementation of a MOSA through DOD’s established acquisition oversight processes, including milestone decision reviews for MDAPs and MTA program reviews.

MDAP milestone reviews: Milestone decision authorities are responsible for approving MDAPs’ acquisition strategies during milestone reviews.[22] These reviews are forums for a program to present its progress and risks to its milestone decision authority to decide whether the program is sufficiently prepared to enter the next phase of development. DOD policy states that the milestone decision authority will review the program’s approach to implementing MOSA to ensure that the program has addressed and implemented standardized interfaces, and arrangements for obtaining necessary intellectual property rights.[23] Milestone decision authorities are also required to ensure that requests for proposals for a program’s development or production phases describe the MOSA, among other things.

At the milestone review for entering the systems development phase, milestone decision authorities are responsible for determining in writing that programs implementing a MOSA incorporate clearly defined major system interfaces, consistent with widely supported and consensus-based standards if available and suitable, and that programs have arranged to obtain appropriate and necessary intellectual property rights with respect to these major system interfaces.[24] The milestone decision authorities are also required to review and determine whether any justification to not implement a MOSA is appropriate, and to determine in writing, for each program that does not use a MOSA, that the use of a MOSA is not practicable.[25]

MTA program reviews: MTA programs’ decision authorities review and approve programs’ entrance and exit from the pathway, using required documentation. Military department acquisition officials told us they use these reviews to assess MTA programs’ MOSA implementation.

As part of the review for entering the MTA pathway, programs that exceed the statutory major system cost threshold prepare and submit the following documents to their decision authorities for their review and approval:[26]

· Approved performance requirements for the system to be developed

· An acquisition strategy that includes security, schedule, and production risks, a cost estimate, and a test strategy or an assessment of test results, among other things

· A cost estimate for the MTA program

· A life-cycle sustainment plan for major systems seeking to initiate on the MTA rapid fielding pathway

Acquisition and engineering officials also oversee MOSA implementation through systems engineering reviews. According to DOD’s engineering instruction, these reviews are generally required for MDAPs unless waived by their systems engineering plan’s approval authority.[27] DOD’s MTA acquisition instruction states program managers will “tailor- in” reviews, assessments, and relevant documentation that results in an acquisition strategy customized to the unique characteristics and risks of their program.[28]

Program Decisions to Implement MOSA Largely Based on Near-Term Considerations

Most programs we reviewed reported implementing a MOSA to at least some extent, with variations in the types of openness and modularity each program pursued. However, programs generally did not conduct formal assessments of life-cycle costs and benefits associated with the decision to invest in a MOSA. As a result, programs’ perceptions of near-term cost and schedule challenges largely drove their decisions on whether to implement a MOSA in the absence of leadership direction above the program to do so.

Programs Reported Varying Degrees of MOSA Implementation

Fourteen of the 20 programs we reviewed—including five of the nine MDAPs and nine of the 11 MTA programs—reported implementing a MOSA. All six Army programs we reviewed reported using a MOSA, while at least half of the programs we assessed at each of the other military services reported using a MOSA. Statute requires programs to implement a MOSA to the maximum extent practicable, giving programs flexibility in determining whether and how a MOSA would meet their specific business and technical considerations. DOD officials told us that it is important for each program to make investment decisions about using a MOSA that meet the program’s life-cycle cost, schedule, and performance needs. Table 1 shows additional detail on programs’ reported MOSA implementation status by military service and program type.

|

MOSA implementation status reported by program |

Military service |

Program type |

Program name |

|

Not implementing a MOSA |

Air Force |

MDAP |

B-52 Commercial Engine Replacement Programa |

|

B-52 Radar Modernization Program |

|||

|

|

MTA |

Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile |

|

|

Navy |

MDAP |

Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile-Extended Range |

|

|

MTA |

Navy Conventional Prompt Strike |

||

|

Space Force |

MDAP |

Weather System Follow-on |

|

|

Implementing a MOSAb |

Air Force |

MDAP |

Mark 21 Reentry Vehicle |

|

MTA |

E-7A Rapid Prototyping |

||

|

Stand-in Attack Weapon |

|||

|

Army |

MDAP |

Future Long Range Assault Aircraft |

|

|

|

|

Improved Turbine Engine Program |

|

|

Precision Strike Missile |

|||

|

|

MTA |

Indirect Fire Protection Capability Increment 2 - Intercept |

|

|

Integrated Visual Augmentation System Rapid Fielding |

|||

|

|

|

Lower Tier Air and Missile Defense Sensor |

|

|

Navy |

MDAP |

Constellation Class Guided Missile Frigate |

|

|

|

MTA |

Hypersonic Air-Launched Offensive Anti-Surface Warfare Weapon System |

|

|

Space Force |

MTA |

Tranche 1 Tracking Layer Rapid Prototyping |

|

|

Tranche 1 Transport Layer |

|||

|

|

|

Tranche 2 Transport Layer |

Legend:

MDAP: Major Defense Acquisition Program

MTA: Middle Tier of Acquisition

MOSA: Modular open systems approach

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense documentation. | GAO‑25‑106931

aThe Air Force’s B-52 Commercial Engine Replacement Program initially planned to enter development in December 2023, but has since delayed that event until 2025. We are including it in our review to capture the Air Force’s MOSA planning for its newer programs.

bStatute requires programs to implement a MOSA to the maximum extent practicable, giving programs flexibility in determining whether and how a MOSA would meet their specific business and technical considerations.

Officials from the programs we reviewed that reported implementing a MOSA told us they selected varying degrees of modularity and openness to meet program priorities. For example, some programs’ MOSAs incorporated a comprehensive system design predicated on enabling competitive upgrades and sustainment. Others had a more limited implementation of MOSA focused on enabling interoperability with other systems. One program—which decided against implementing a MOSA—still invested in limited open system attributes for peripheral systems. Table 2 provides examples of MOSAs pursued by programs we reviewed.

Table 2: Examples of Modular Open Systems Approaches (MOSA) and Areas of Emphasis Reported by Weapon Programs GAO Reviewed

|

MOSA emphasis |

Program example |

|

Emphasis on reducing life-cycle costs |

The Army’s Future Long Range Assault Aircraft program reported that it used data on sustainment cost drivers from aircraft already in service to develop a MOSA that would reduce operating and upgrade costs over its service life. Specifically, the program developed an open architecture framework to guide the aircraft’s design in collaboration with industry groups and academia to ensure its systems would prioritize employing the most relevant and widely used open standards. This design approach maximized the potential pool of vendors and technologies available to meet the program’s needs. These design priorities were used to evaluate the quality of competing vendors’ offers to build the prototype aircraft. |

|

Emphasis on enabling interoperability with multiple systems |

The Army’s Improved Turbine Engine Program is developing a new aircraft engine. Program documentation states it is focused on ensuring the engine’s interfaces with the aircraft are defined by open standards or government-owned interface specifications, including engine control software. According to officials, this reduces the risk of encountering integration challenges due to proprietary interfaces when the engine is installed on aircraft built by different contractors. |

|

Emphasis on increasing competition for future upgrades |

Space Force officials told us they used a MOSA in the design of satellites in their Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture. This program involves constellations of large numbers of satellites in the Tranche 1 Tracking Layer Rapid Prototyping (providing warning and tracking capability) and the Tranche 1 and 2 Transport Layers (providing data communications) programs. Officials told us a MOSA enables them to reduce barriers to new companies competing for new iterations and capabilities as the constellations are refreshed over time. Officials stated that by using common communication interfaces and designing for a MOSA, Space Force expects replacing portions of these constellations to be less costly as improved technologies become available.a |

|

Invested in limited open system attributes for peripheral systems |

The Air Force’s B-52 Radar Modernization Program reported that its primary systems will not incorporate MOSA attributes. Program officials told us they considered adding MOSA attributes to the pre-existing proprietary system design to be cost-prohibitive for most parts of the system. However, officials stated that they did incorporate certain elements of openness by installing an information distribution system and visual displays that used open interfaces. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense documentation and interviews with program officials. | GAO‑25‑106931

aThe Senate report accompanying the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 included a provision for us to review DOD’s efforts to develop space-based optical communications capabilities. The Senate report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 include a provision for us to review DOD’s efforts to deploy overhead persistent infrared space-based architectures. As of October 2024, our work on both reviews is ongoing.

Programs’ MOSA Implementation Decisions Were Not Informed by Formal Assessments of Life-cycle Costs and Benefits

None of the 20 selected programs we reviewed provided documentation of a cost-benefit analysis conducted to support their decisions about whether and to what extent to pursue a MOSA. For example, officials from three of the five selected programs that decided not to pursue a MOSA told us this decision was due to perceived costs. These officials, however, reported that their decision was not based on a formal analysis of the potential costs to implement a MOSA and the value of its potential benefits over the program’s life cycle.

DOD’s acquisition policy and guidance do not contain an explicit requirement to conduct a cost-benefit analysis of implementing a MOSA. DOD officials provided two documents that assessed the costs and long-term benefits of MOSA investments. However, the officials who provided us with the documents noted limitations with these analyses. Officials from the Army’s PEO Aviation told us they commissioned such an analysis from a consultant to show the potential to reuse parts across their portfolio of programs. The officials said the analysis generally supported cost savings but had not been validated. Officials from the Air Force provided us with an analysis conducted as part of a graduate program and said they refer generally to it when discussing positive return on investment for using a MOSA. Programs’ life-cycle outcomes—such as reduced sustainment costs and insertion of new technologies—are in part determined by decisions made early in the acquisition process. In our prior work on cost estimating, we found that cost-benefit analyses can support program decisions when it is important to take a long view of the future.[29] When those decisions are not based on both the estimated costs and estimated benefits of a MOSA, programs can miss opportunities for significant cost savings and flexibility to update capabilities to keep pace with threats over their life cycles.[30]

We previously found that programs reported acquisition cost and schedule concerns when deciding not to implement a MOSA.[31] Programs’ rationales for not implementing a MOSA in this review were consistent with our prior work; program officials generally told us they based their decisions on acquisition cost and schedule implications. For example, officials from programs we reviewed cited perceptions that a MOSA would increase development costs, lengthen development schedules, or not yield sufficient benefits. However, these perspectives focused largely on acquisition costs, which may account for only 30 percent of a system’s life-cycle costs.[32] Longer term sustainment and modernization costs—which MOSA is intended to mitigate—impose a much larger burden on DOD’s budget. Additionally, these perspectives do not account for the potential for a MOSA to accelerate fielding new capabilities to existing platforms, keeping them operationally relevant for longer periods of time. For example, a program using a MOSA would face less costly and time-intensive re-work to incorporate upgraded systems if the systems are built to the same open-interface standards. In two cases, officials told us significant leadership emphasis on implementing a MOSA pre-empted acquisition cost and schedule concerns.

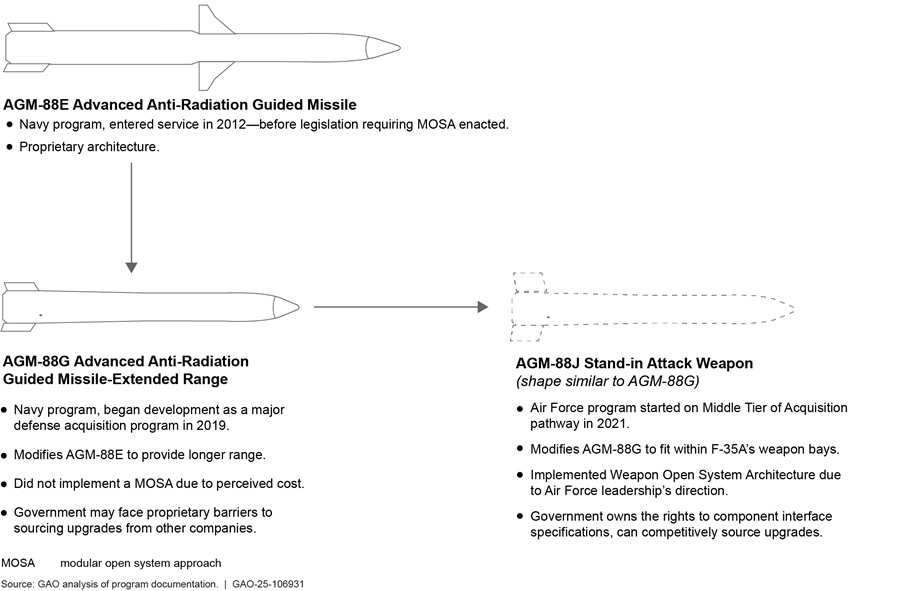

The Navy’s AGM-88G Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile-Extended Range (AARGM-ER) program and the Air Force’s Stand-in Attack Weapon (SiAW) program illustrate how perceptions of near-term cost and schedule barriers and the influence of leadership can affect program’s MOSA choices for similar programs. Officials from the AARGM-ER program told us it decided not to pursue a MOSA due to near-term cost and schedule concerns. However, Air Force officials told us that the service’s acquisition leadership directed the SiAW program, which is modifying the AARGM-ER’s design, to implement a MOSA. More specifically, both programs are adapting the Navy’s AGM-88E Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile (AARGM) to deliver new capabilities, but Navy and Air Force acquisition officials told us only SiAW requested and received funding to implement a MOSA, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: MOSA Development and Differences between Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile-Extended Range and Stand-in Attack Weapon

|

Leadership Influence on Programs’ Modular Open System Approach (MOSA) Decisions The Air Force’s requirement for its air-launched munition programs to use the Weapon Open Systems Architecture (WOSA) standard in their designs illustrates the influence of leadership priorities on program decisions related to a MOSA. WOSA is a standardized design process that requires systems to modularize the components needed to deliver the system’s functions and connect these modules with either open interface standards or interfaces for which the government owns the technical specifications. Air Force Weapons Directorate officials told us the Stand-in Attack Weapon program was required to use the WOSA standard. They added that implementing this standard is mandatory for all of the directorate’s new programs. Along with the technical standard for WOSA, Air Force officials told us they also created standardized contract language, tools for verifying the system’s interfaces will accept components built to the same standard, and model-based systems engineering assets. These features have the potential to reduce the burden on a program incorporating the standard into its design and contract documents. Air Force officials stated that these efforts have led to use of the WOSA standard beyond their service, with Navy weapon programs receiving bids from companies that proactively incorporate it. Greater WOSA use can reduce proprietary barriers in the broader marketspace for air-launched munitions. Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense documentation and interviews with Air Force officials. | GAO‑25‑106931 |

AARGM-ER program officials told us that munition programs like theirs do not typically consider a MOSA for sustainment cost reduction benefits, given that munitions are single-use. However, they noted that a MOSA has more value in enabling rapid upgrades as threats change or technology advances.

The AARGM-ER program entered development after January 2019 and therefore was required to implement a MOSA to the maximum extent practicable. The program decided it was not practicable to implement a MOSA. AARGM-ER officials told us the program’s funding was insufficient. However, program officials could not recall if there had been a business case analysis of a MOSA to inform this decision. Because the program did not obtain the data rights needed to implement a MOSA, future upgrades may take longer to complete. Further, having fewer vendors reduces opportunities for competition and could result in higher costs.

Conversely, Air Force officials told us that the SiAW program initially proposed establishing the program as an MTA effort that only repackaged the existing AARGM-ER systems within a physical shape that can fit within the F-35A’s weapon bays. Air Force acquisition leadership rejected this approach, noting that it would be more expensive and time-intensive to upgrade these missiles to keep pace with technology advances and changing threats over their service lives if each upgrade required extensive work to adapt the new components to the system’s proprietary design. Instead, program officials stated that the Air Force acquisition executive established a clear expectation that the system implement a modular design by obtaining necessary interface data rights specifically developed for air-launched munitions called Weapon Open System Architecture. They told us that, while they expect these modifications to add time and costs to the system’s development, they also expect the MOSA to significantly reduce time and costs for later modifications.

|

Future Long Range Assault Aircraft

|

Leadership direction at the portfolio level has also shaped programs’ MOSA decisions. For example, the Army’s Future Long Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) tilt-rotor aircraft program—an MDAP that began in 2020 as an MTA rapid prototyping effort— set objectives for its MOSA to enable faster fielding of innovations and greater affordability via competition. The program decided to implement a MOSA before there was a statutory requirement for MTA programs to do so.

Army Aviation PEO officials told us this decision was driven by the PEO’s leadership team, which conducted an affordability analysis of its portfolio of programs. This analysis found the service could not afford its planned aviation force size without lowering sustainment costs. The sustainment costs for the portfolio were high, according to the analysis, in part because each proprietary system required unique components that were difficult to competitively source, limiting potential savings from economies of scale on larger orders for multiple programs. Army officials told us that they expect that FLRAA’s use of common interface standards as part of its MOSA will also lower acquisition costs for other programs in the same portfolio by enabling other Army aviation programs to reuse the same components. FLRAA also established the quality of a proposed MOSA as a criterion to assess competing vendors’ proposals for the system development contract.

However, officials from other programs we reviewed determined not to implement a MOSA due to near-term cost and schedule concerns or perceptions of limited benefit. While these decisions may have been logical program decisions based on concerns, without an analysis of estimated life-cycle cost and benefits of implementing a MOSA, it is difficult for program and acquisition officials to understand the full picture. For example:

|

B-52 Bomber Aircraft

|

· The Air Force’s B-52 Radar Modernization Program (RMP)—an MDAP that entered development in 2021 and is intended to fit a modern radar onto the almost 70-year-old bomber aircraft—initially planned to implement a MOSA but was deterred by concerns about costs. Program officials told us they initially anticipated that designing RMP’s components around a MOSA would reduce development time by enabling the program to leverage more existing components. They expected a MOSA would allow the radar to easily accept new technologies and adapt to new requirements through 2050 and beyond. Further, the program reported that over the life cycle of the radar system, the components designed using a MOSA would be more easily upgradeable as technology changed and new requirements emerged.

However, program officials told us they have since discontinued plans to incorporate a MOSA in the radar. They told us that after the program was directed to use a pre-existing radar to reduce development costs, they determined—based on informal analysis—that a MOSA was not practicable. This was due in part to the cost and time required to (1) modify a radar that was already in production and used on several other aircraft, and (2) test the new system. More specifically, program officials noted that reduced funding made the $40 million to $60 million cost estimated by the program to incorporate the planned MOSA unaffordable when weighed against the program’s other priorities. Additionally, they stated that implementing a MOSA would have challenged the program’s ability to integrate the new radar in time to meet the warfighter’s needs. However, test failures and other factors contributed to schedule delays totaling 10 months over the program’s schedule baseline.

|

Navy Conventional Prompt

Strike Hypersonic

|

· The Navy’s Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS) program’s rapid prototyping MTA effort—which is being developed in part with the Army—decided not to pursue a MOSA on its current development contract due to schedule pressure. Navy officials told us the prototyping effort was started in response to an urgent operational need to field a hypersonic weapon. They added that the potential to implement a MOSA was limited due to the omission of a MOSA from an earlier prototyping effort. The portion of the missile that achieves hypersonic flight was developed prior to the MTA program’s start and did not implement a MOSA. Navy officials told us that for that reason, they determined they would not be able to implement a MOSA within the time available for the MTA prototyping effort.

There was no statutory requirement for MTA programs to implement a MOSA to the maximum extent practicable when the contract was awarded in December 2018, and CPS program officials decided not to use a MOSA with the initial prototyping effort to meet the warfighter’s urgent requirement. However, if the hypersonic vehicle had been designed with a MOSA from the start, CPS may have been better positioned to enable rapid iterations and technological advances. CPS missiles are planned to be deployed on ground-based launchers, surface ships, and submarines, exposing the missiles to different combat environments that will likely require the program to incorporate different capabilities over its service life. While program officials told us they are considering a MOSA on later increments, doing so later in the program may require costly design rework to that may have been avoided if a MOSA was implemented from the start. Navy officials stated that they plan to incorporate aspects of a MOSA in later versions of the missile as part of their process for inserting new technologies.

|

Weather System Follow-On Satellite

|

· Program officials with the Space Force’s Weather System Follow-On program—an MDAP that entered system development in 2020, after the statutory requirement for MDAPs to use a MOSA to the maximum extent practicable took effect—told us they determined implementing a MOSA was not practicable. The program plans to launch two satellites and program officials told us they determined that it would be too costly to upgrade systems on a satellite after launch, therefore limiting the benefit that the program could achieve from a MOSA. However, USD(R&E) officials stated that a modular and open design would also enable other satellite programs to re-use components developed by this program, potentially reducing their development time and costs.

DOD officials we spoke with told us that there is no agreed-upon approach for assessing MOSA costs and benefits, but also shared examples of how it could be done. Specifically:

· Officials from CAPE—responsible for ensuring that DOD conducts accurate cost estimation and analyses—told us potential inputs into a MOSA cost-benefit analysis could include increased opportunities for competition—which could reduce sustainment costs—and quicker upgrades, which could keep a program in service longer. They also cited examples of upgrades to the Navy’s P-8A maritime patrol aircraft and submarine combat systems that achieved cost savings and greater flexibility from implementing an open systems approach.

· Officials from the offices of USD(A&S) and USD(R&E) told us they also were not aware of any widely accepted methods for estimating the costs and benefits of a MOSA. However, USD(R&E) officials told us that comparing the cost of replacing part of a fielded system with the development of a brand-new system is one example of how DOD could approach estimating the value of early investment in a MOSA.

In our prior work on evidence-based policymaking, we found that federal organizations should assess the extent to which existing evidence addresses key questions, and then identify and prioritize new evidence needed to manage efforts and assess results.[33] USD(A&S) and USD(R&E) officials said although estimating costs and benefits is an important aspect of managing MOSA efforts, they already have a significant volume of other work related to MOSA implementation, and as a result, have not prioritized developing a method. Similarly, CAPE officials told us they have not been directed to study how a MOSA affects sustainment costs. However, without developing a consistent method to compare MOSA costs and benefits over the life cycle to support early decision-making, DOD risks missing opportunities to field systems that are interoperable, adaptable to emerging threats, and less costly to sustain.

DOD Does Not Use Program- and Portfolio-Level Planning Effectively to Define and Support MOSA Objectives

Most Programs Did Not Address MOSA Planning Elements, Including Those Required by Statute or Policy

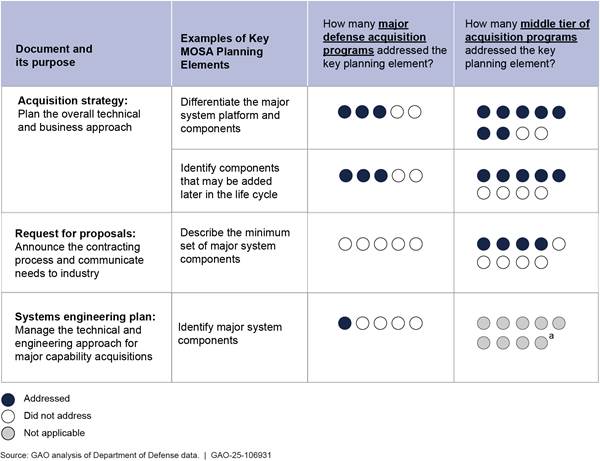

The 14 selected programs we reviewed that reported implementing a MOSA generally did not address all key MOSA planning elements, such as documenting which parts of the system will be designed as replaceable modules. Key planning elements that programs should address in their acquisition documents (including acquisition strategies, requests for proposals for the program’s development or production phases, and systems engineering plans) are defined in statute or DOD policy.[34] As a result of these statutory and policy provisions, programs may need to consider aspects of their MOSA from the early stages of development in planning documents like the acquisition strategy and systems engineering plan, which for MDAPs must be updated and reviewed for major milestones.

Key MOSA planning elements differ somewhat for each type of acquisition document. For example, in acquisition strategies, MDAPs are required to describe the MOSA and differentiate between major system platforms and major system components (modules that can be severed and changed over time). Programs are also required to explain how major system components might evolve in the future. Each module needs a boundary to keep it both part of and separate from the platform. If the program does not design around that boundary from the beginning, it will either incur increased costs and delays to rework the design or fail to achieve the program’s MOSA objectives. Figure 7 illustrates the number of the 14 programs implementing a MOSA that addressed key planning elements in their acquisition documents.

Figure 7: Number of Programs That Reported Using a MOSA That Addressed Key MOSA Planning Elements in Acquisition Documents

Note: Key planning elements identified above are those defined in statute or Department of Defense (DOD) policy. While there is no statutory or DOD-wide requirement for middle tier of acquisition programs to document their modular open systems approach (MOSA) decisions in their planning documents, we assessed the extent to which the selected middle tier of acquisition programs documented two of the same aspects of their MOSA as an indicator for the quality of their MOSA planning. Programs we reviewed that reported not using a MOSA are not included in this figure.

aWe did not assess MOSA aspects of systems engineering plans for selected middle tier of acquisition programs because they are generally not required to complete these plans.

The following examples illustrate the range of how programs addressed MOSA planning elements in acquisition documents.

The Air Force’s E-7A Rapid Prototyping MTA program—which is modifying an existing airborne warning aircraft used by other countries to meet U.S. requirements—addressed key MOSA planning elements in its acquisition strategy and request for proposals.

|

E-7A

|

· Acquisition strategy: The program provided a list of subsystems and stated that the system will be compliant with Open Mission Systems, an Air Force standard.

· Request for proposals: E-7A was one of only four selected programs that addressed the minimum set of major system components in its request for proposals. The program specified the set of mission support components the contractor must develop, including their functional and physical attributes. For example, the program described some components that support multiple aircraft and others that are portable between single aircraft. However, by specifying the minimum set of major system components, the program increased the likelihood of realizing the potential benefits of using a MOSA.

· Systems engineering plan: Not applicable for MTA programs.

|

Precision Strike Missile

|

The Army’s Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) program—an MDAP that entered development in 2021—included key MOSA elements in two of its planning documents.

· Acquisition strategy: The program identified the components with which the system will be designed and potential capabilities to be added in the future. The program identified major system components like guidance, propulsion, and payload. In its acquisition strategy, the program states that designing major subsystems as severable components will enable an incremental development approach to continuously incorporate new technologies to support future capabilities.

· Request for proposals: The program did not include any MOSA elements in its request for proposals. However, contractor ultimately signed an agreement that included provisions requiring them to use a MOSA and identify potential future upgrades.

· Systems engineering plan: The program included a list of major system components in its systems engineering plan.

The Navy’s Constellation class guided missile frigate (FFG 62)—an MDAP that entered development in 2020 and is modifying the design of a frigate used by the French and Italian navies to meet the U.S. Navy’s requirements—did not include key MOSA elements in its planning documents.[35]

|

FFG 62 Constellation Class

Guided Missile

|

· Acquisition strategy: FFG 62 provided general language about the program’s MOSA principles but did not address planning elements for modularity.[36] Navy officials described FFG 62 as a large and complex system of systems, many of which will be developed by other program offices. However, the acquisition strategy does not describe the major components for which the FFG 62 program is responsible.

· Request for proposals: The request for proposals did not identify the minimum set of major system components as required. The program described general attributes its MOSA is intended to achieve, such as reusability and upgradeability in this document.

· Systems engineering plan: FFG 62 did not identify major system components as required in the systems engineering plan. The only information related to the MOSA is a statement that the program will require the contractor to conduct an analysis for incorporating MOSA attributes into systems based on information technology.

We found that the military departments generally did not assess whether programs incorporated the required MOSA planning elements in acquisition documentation. Service acquisition executives—the decision authorities for our selected programs—are responsible by law for reviewing acquisition strategies and requests for proposals, including key MOSA planning elements.[37] Further, DOD policy states that milestone decision authorities must review MDAPs using a MOSA at Milestone B to ensure that their interfaces are standardized and review a justification by the program if it will not use a MOSA.[38] Officials within the offices of the service acquisition executive at the military departments told us that while they review program documentation in advance of milestones or other key program events, they have limited capacity to review MOSA-specific elements in these documents. As a result, they defer to subordinates for their evaluation of programs’ MOSA plans.

Some program officials told us that they documented key MOSA decisions in other documentation, such as milestone briefing slides or model-based systems engineering software. However, requirements in statute and DOD policy to address MOSA in acquisition documents help keep decision authorities informed about MOSA planning decisions and communicate programs’ MOSA requirements to contractors. Without assessing whether programs have identified MOSA planning gaps in key acquisition documents, including as required by law and policy, decision authorities will have limited visibility into whether programs are positioned to achieve potential MOSA benefits such as flexibility in upgrades and more opportunities for competition during sustainment.

Inconsistent Portfolio-Level Planning Further Limits Potential MOSA Benefits

A MOSA has potential benefits when coordinated between programs in a portfolio. These benefits include helping to ensure interoperability between systems, facilitating cost savings through reuse of software and hardware, and enabling faster upgrades in the future. Nevertheless, only two of the nine PEOs overseeing a subset of our 20 selected programs reported that they have a formal process specifically intended to coordinate MOSA opportunities. Two PEOs reported that their offices have no formal process, and one reported that they coordinate for commercial off-the-shelf parts but not for a MOSA. The remaining four PEOs reported that the potential for a MOSA is considered as part of their existing program review processes but did not describe a formal portfolio coordination process. However, existing review processes typically address individual programs rather than portfolio-wide opportunities, so they are unlikely to be sufficient to ensure coordination of MOSA implementation across a portfolio of programs.

PEOs that do not have a process to ensure coordination on MOSA may be missing opportunities to achieve cost reductions and enable faster upgrades in the future. For example, officials in the Navy’s Air Combat Electronics office told us that implementing a coordinated MOSA can lead to cost savings. This office is a cross-cutting program office that interfaces with other Navy programs to develop avionic systems that are incorporated on different types of Navy aircraft. In some cases, they develop common capabilities for multiple programs. Officials from this program office told us that MOSAs can drive cost savings when programs buy common parts at the same time and achieve economies of scale. However, they said to sequence upgrades effectively, PEOs need to assess what programs need now and forecast for the future.

One example of a MOSA portfolio coordination process is the MOSA advisory board for the Army’s PEO Aviation. Army officials told us the board was established in 2022 and consists of representatives of a cross section of the PEO’s programs and functional areas like engineering and budget. The PEO told us the board meets monthly to review programs for components with the potential for reuse and to make investment recommendations to the PEO. This coordination effort could reduce the number of costly efforts to deliver the same capability.

The Project Management Institute, Inc., standard for portfolio management states that organizations should establish strategic objectives for their portfolios, to prioritize components of the portfolio, identify interdependencies between components, and allocate resources. The standard also states that organizations should evaluate their portfolio of programs on an ongoing basis to ensure benefits, risks, and resources are appropriately balanced.[39] Further, we have previously reported that developing processes for portfolio management is a leading portfolio management practice.[40] Until the military department PEOs develop processes to assess MOSA opportunities across their portfolios, they risk missing opportunities to better leverage resources across programs and identify MOSA investment priorities that best reflect portfolio-wide needs.

Military Departments Have Yet to Fully Identify and Prioritize Investments Needed for MOSA Implementation

The military departments have yet to fully identify and prioritize necessary investments for MOSA implementation at the enterprise level. The NDAA for Fiscal Year 2017—enacted in December 2016—required the secretaries of the military departments to ensure necessary budgetary resources and engineering expertise for MOSA implementation.[41] Acquisition officials at the Departments of the Air Force, Army, and Navy, however, stated they have yet to assess or align resources for MOSA implementation across their respective departments.

DOD and military department officials we spoke with described several categories of resources that facilitate MOSA implementation. These include repositories for MOSA data, access to open standards, subject matter expertise, and digital engineering tools. These officials stated that, in some instances, these activities have not been resourced to a degree needed to implement MOSA to the maximum extent practicable as required by statute:

· Repositories for storing and accessing shared MOSA files. The William M. (Mac) Thornberry NDAA for Fiscal Year 2021 required USD(A&S) to direct the appropriate DOD components to establish and maintain repositories for interfaces, syntax and properties, documentation, and other information.[42] Making MOSA-related files accessible to acquisition officials working on other programs helps ensure reuse of open standards, decrease development time, and preserve information that will be essential to sustain systems designed using a MOSA.

Military department officials told us that development of these repositories is in process. Navy officials said they have created a repository containing standards that they believe meets the minimum requirements of the law, although, in their view, the language of the law is vague regarding what is required to be in the repository. Air Force officials told us that although they have established an initial minimal repository in response to the legal requirement, they have faced challenges due to limited available funding. In the future, they would like to expand its capabilities to enable new programs to search for pre-existing components with open standards to use as the building blocks of their early system designs. Army officials told us they created a repository in response to the law, but it is maintained by staff at different PEOs and they are in the process of determining what additional information will be added to it in the future. USD(R&E) officials told us that without military department-level efforts to establish common formats for MOSA-related digital files in these repositories, there is a risk that programs will not be able to access and use data they need for future modernizations.

· Enterprise licenses for standards. DOD officials told us the department is required in some cases to pay in order to gain access to commercially-developed open standards used on DOD weapon systems. OSD and military department acquisition officials stated there is currently no military department-level process for providing programs with access and licenses for using MOSA standards. They stated that providing licenses at the military department level, rather than requiring programs to obtain separate licenses, would particularly benefit smaller programs, as a relatively larger portion of their funding would be needed to address licensing issues than for a larger program. Many open standards are developed by consortia of private companies and require a licensing fee to access these standards. These acquisition officials stated that in such cases, it is more efficient to pay the fee once at the enterprise level, rather than paying each time a program decides to implement a standard.

· MOSA expertise. Some offices within DOD have had difficulty funding positions for MOSA subject matter experts. For example, Air Force Materiel Command officials stated that they had requested funding to hire MOSA subject matter experts to provide direct assistance to programs regarding MOSA. They said the funding request was rejected for inclusion in DOD’s budget request when their request reached the OSD level. They stated that this was due to MOSA being a lower priority compared to other needs. Additionally, while offices such as USD(R&E) may serve as a source of expertise to help military departments implement MOSA effectively, USD(R&E) officials stated they do not have available staffing to review specific program-level MOSA efforts or provide substantial technical assistance at the program level. Furthermore, the Air Force’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2025 called for eliminating all future funding for Department of the Air Force Technical Architectures—in favor of other unstated Air Force priorities. Air Force budget documentation from March 2024 stated this effort was to shape the technical architecture of the entire Air Force and Space Force and foster modular architectures across programs. The documentation further noted that without these architectures, the Air Force would continue to acquire singular systems instead of modular, open system-of-systems capabilities.

· Digital engineering tools. The military departments have begun planning efforts to provide digital engineering tools needed for MOSA, such as model-based systems engineering software. DOD officials said model-based systems engineering helps programs document key MOSA decisions, use templates to easily implement consensus-based standards, and continuously evaluate the design process in real time.

Officials from all the military departments told us they each have at least one effort to facilitate MOSA using model-based systems engineering. However, these efforts are still underway, and funding for these tools is not universally available within DOD. For example, Navy officials told us that they can only procure digital design tools if program office funds are available. Additionally, military department officials stated that if programs use tools that are not common to the rest of DOD, then data generated by those tools are not useable by other programs, so they would prefer to use a common set of tools.

We previously reported in July 2023 that DOD officials stated many benefits of engineering tools are realized or enhanced and that costs—such as licensing—are reduced through widespread usage and implementing them collectively, rather than individually. We also reported that DOD had not enabled the adoption of modern engineering tools across all programs and recommended that DOD establish an overarching plan—which identifies associated resources—to do so. DOD officials estimated this plan would be finalized in December 2024.

Additionally, OSD and military department officials stated that not all MOSA efforts at the program level have adequate prioritization to receive funding, even when there is no technical barrier to implementing MOSA. As discussed earlier, military department secretaries are legally required to ensure necessary resources are provided to develop a MOSA.[43] Currently, acquisition programs individually request resources during the budget process. DOD officials stated that some programs, such as AARGM-ER, have faced difficulties in obtaining available funding, which is sometimes due to funds being devoted to higher priorities. These difficulties may occur particularly when there is no corresponding validated MOSA requirement that funding decision-makers understand enables the delivery of new capabilities. Air Force Materiel Command officials also stated that officials at programs working with pre-existing systems have limited funds and must prioritize satisfying the requirements specified in capability requirements documents. While MOSA implementation may help reduce weapon systems costs in the longer term, USD(R&E) officials stated that program offices trying to field systems are focused on containing short-term costs more so than long-term costs.

In 2019, the military department secretaries indicated in a joint memorandum that MOSA is a warfighting imperative.[44] However, officials at all three military departments told us they have yet to develop department-level plans that identify their goals and prioritize resources for MOSA investments. The 2019 memorandum directed that MOSA standards be included in all requirements, programming, and development activities for future weapon system modification and new start development programs to the maximum extent practicable.

Furthermore, the 2022 National Defense Strategy also highlighted the importance of open systems to the nation’s military needs.[45] The strategy noted how the existing DOD acquisition process was too slow and not incentivized to design open systems that can rapidly incorporate cutting-edge technologies. The National Defense Strategy noted that this situation creates problems such as obsolete equipment, poor interoperability, and cost ineffectiveness.

Currently, DOD pursues MOSA adoption through individual program efforts overseen on a program-by-program basis, rather than using enterprise-wide plans addressing MOSA as an organizational priority as called for by the joint memorandum and the National Defense Strategy. Our prior work on evidence-based policymaking highlighted the importance of government organizations developing a plan to achieve organizational objectives, as well as defining the desired outcomes and aligning the resources needed.[46] Until the military departments develop department-level plans that identify their goals and prioritize resources for MOSA investments, they will not be well-positioned to ensure that they are providing the necessary resources and engineering expertise required to implement MOSAs.

DOD Has Gaps in MOSA Policy, Regulations, and Guidance

DOD has updated some acquisition and engineering policies and is drafting statutorily required regulations and guidance at the OSD level to address MOSA. However, gaps in policy, regulations, and guidance remain at the OSD and military department level. First, DOD’s policy for programs using the MTA pathway does not address how MOSA requirements apply to programs using this pathway. Second, drafting and issuance of required MOSA regulations and guidance at the OSD level is ongoing. Lastly, while the Army has developed detailed MOSA implementation guidance for its acquisition programs, the development of military department-level guidance has yet to be completed at the departments of the Air Force and Navy.

OSD Policy for MTA Programs Does Not Address MOSA Implementation

USD(R&E), USD(A&S), and CAPE have updated engineering and acquisition policies to implement MOSA, including for the major capability acquisition pathway (used by MDAPs) and the software acquisition pathway.

· Engineering of Defense Systems, DOD Instruction 5000.88 (Nov.18, 2020): USD(R&E) engineering policy describes various requirements for programs where a MOSA is concerned. These include a policy requirement for major capability acquisition programs to address MOSA in systems engineering plans and to comply with statutory requirements for MOSA implementation to the maximum extent practicable.

· Intellectual Property Acquisition and Licensing, DOD Instruction 5010.44 (Oct. 16, 2019): USD(A&S) intellectual property policy requires military departments to ensure intellectual property deliverables and associated license rights are acquired and managed as necessary to support the use of modular open systems approaches in accordance with the law.

· Major Capability Acquisition, DOD Instruction 5000.85 (Nov. 4, 2021): USD(A&S) policy on major capability acquisitions states that program managers are responsible for evaluating and implementing a MOSA to the maximum extent feasible and cost effective. In general, the acquisition strategy must address MOSA and milestone decision authorities must ensure that, for programs implementing MOSA, their programs’ development and production requests for proposal describe the MOSA.

· Operation of the Software Acquisition Pathway, DOD Instruction 5000.87 (Oct. 2, 2020): USD(A&S) policy on the software acquisition pathway requires programs using this pathway to use a MOSA as part of their use of modern, iterative software development approaches to support future capabilities.

· Analysis of Alternatives, DOD Instruction 5000.84 (Aug. 4, 2020): CAPE policy regarding how programs are to conduct an analysis of alternatives requires that consideration of the use of MOSA be included in the study guidance for these analyses.

However, these updates do not address how MOSA-related requirements apply to programs using the MTA pathway The requirement to implement MOSA to the maximum extent practicable for MDAPs was included in the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2017. It was extended to all program types (including MTA programs) by the William M. (Mac) Thornberry NDAA for Fiscal Year 2021.

DOD has yet to provide pathway-specific policy for MTA programs on implementing MOSA to the maximum extent practicable.[47] Our prior work has shown that DOD is increasingly leveraging the MTA pathway to develop and field critical capabilities.[48] While DOD updated its instruction for MTA programs in November 2024, the updated policy does not specifically address MOSA. A USD(A&S) official told us in September 2024 that MOSA would not be addressed in the update because its inclusion was raised too late in the process. As an alternative, USD(A&S) plans to address MOSA in the Adaptive Acquisition Framework Document Identification Tool hosted by the Defense Acquisition University, which it planned to establish in the updated instruction as having the same authority as the MTA pathway instruction.