INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Agencies Should Improve Oversight of Reciprocal Defense Procurement Agreements

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106936. For more information, contact Tatiana Winger at (202) 512-4128 or WingerT@gao.gov, or William Russell at (202) 512-4841 or russellw@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106936, a report to congressional requesters

Agencies Should Improve Oversight of Reciprocal Defense Procurement Agreements

Why GAO Did This Study

The Department of Defense (DOD) has entered into RDP Agreements with 28 partner countries. The agreements are intended to create more favorable conditions for defense procurement. DOD is responsible for entering into and assessing RDP Agreements, including considering the effect of existing or proposed agreements on U.S. industry. The Department of Commerce and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) also have roles for evaluating the effects on U.S industry.

GAO was asked to review RDP Agreements and how they are initiated, monitored, and assessed. This report examines (1) the provisions of RDP Agreements and how the agreements vary, (2) the degree to which U.S. agencies have developed and followed processes to initiate and renew RDP Agreements, and (3) the extent to which U.S. agencies have assessed and monitored the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. industry. GAO reviewed the 28 RDPs and analyzed additional documents and data from DOD and Commerce. GAO interviewed officials from these agencies, a U.S. defense industry association, and an association of RDP officials from several partner countries.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations, including that DOD and OMB improve oversight of RDP Agreements to better assess and monitor the effects of RDP Agreements and that Commerce address weaknesses in its methodology. DOD and Commerce concurred, and OMB partially concurred with GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

Every year the U.S. engages in billions of dollars in defense trade with countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan. To facilitate this trade, DOD and 28 partner countries have signed Reciprocal Defense Procurement (RDP) Agreements, which include similar provisions to open opportunities and waive “buy national” laws. For the U.S., the Secretary of Defense waives the Buy American Act—which generally requires U.S. federal agencies to buy U.S. goods and services—for RDP partner countries. As a result, these agreements may have significant trade implications for defense markets. Most RDP Agreements have been in place for decades and include automatic extension provisions.

Since 2018, DOD has skipped important due diligence steps for entering into and renewing RDP Agreements. For example, for three agreements DOD did not solicit input from industry and for another agreement, DOD did not seek analysis from Commerce, as required. Industry input and Commerce’s analysis are important to determine if the agreements help or hurt U.S. industry.

U.S. agencies’ efforts to monitor and assess the economic effects of RDP Agreements are limited. DOD is required to monitor and assess the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. defense technology and industry and to solicit input from Commerce. However, the information and methods agencies rely on to evaluate the effects of RDP Agreements have limitations. Specifically,

· DOD has done little to monitor and assess the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base.

· Commerce’s methodology to assess RDP Agreements has several weaknesses. For instance, it does not cover the effects of RDP Agreements on services, even though 49 percent of the value of DOD procurements was for services in fiscal 2022.

· Further, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) had not developed a plan to facilitate its statutorily required reviews of RDP Agreements.

Unless U.S. agencies improve methods to assess proposed agreements and do more to monitor existing agreements, the U.S. government cannot be sure whether these and future agreements, such as those proposed for Brazil, India, and the Republic of Korea, achieve their purposes.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

BIS |

Bureau of Industry and Security |

|

DFARS |

Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DPCAP |

Office of Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy |

|

DSCA |

Defense Security Cooperation Agency |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulations |

|

GPA |

Agreement on Government Procurement |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

ITA |

International Trade Administration |

|

MDCA |

Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement |

|

MIAO |

Made in America Office |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

RDP |

Reciprocal Defense Procurement |

|

USTR |

United States Trade Representative |

|

WTO |

World Trade Organization |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 20, 2024

The Honorable John Garamendi

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Readiness

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Mike Braun

United States Senate

The Honorable Debbie Stabenow

United States Senate

The Department of Defense (DOD) is the largest U.S. federal agency purchaser of foreign goods, engaging in billions of dollars in annual defense trade with countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan. DOD has signed Reciprocal Defense Procurement (RDP) Agreements with 28 partner countries to help facilitate trade in defense items such as weapon systems and components.[1]

Under the terms of an RDP Agreement, DOD and an RDP partner country agree to waive “buy national” requirements, among other provisions. While U.S. federal agencies are generally required to buy U.S. goods and services under the Buy American Act, the Secretary of Defense waives this requirement for all 28 RDP partner countries.[2] As a result, RDP Agreements may have significant trade and economic implications for U.S. access to foreign defense markets as well as foreign access to the U.S. defense market.

Under the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1989, DOD is required to consider the effect of existing or proposed RDP Agreements on U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base.[3] DOD is also required to regularly solicit and consider comments and recommendations from the Department of Commerce on the commercial implications and potential effects on the international competitive position of U.S. industry.

The Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Made in America Office (MIAO), established in 2021, is statutorily required to review RDP Agreements to assess whether U.S. domestic entities will have equal and proportional access to RDP partner defense markets.[4] A May 2024 letter from Senator Stabenow and Representative Garamendi to the Made in America Director reiterated concerns that DOD may be entering into RDP Agreements without sufficient input from the U.S. industrial base.

You asked us to review RDP Agreements and how they are initiated, monitored, and assessed. This report examines (1) the provisions of RDP Agreements and how the agreements vary among RDP partner countries, (2) the degree to which U.S. agencies have developed and followed processes in place for the initiation and renewal of RDP Agreements, and (3) the extent to which U.S. agencies have monitored and assessed the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. industry.

In addressing these objectives, we reviewed all 28 RDP Agreements with RDP partner countries as of March 2024, as well as documents and data from DOD, the Department of Commerce, OMB, and the Department of State. For our first objective, we developed and used an assessment tool to identify key provisions contained in all 28 RDP Agreements. For our second objective, we reviewed and analyzed DOD documentation and policies as well as communications between DOD, Commerce, State, U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), and OMB on entering into or renewing RDP Agreements.[5] For our third objective, we reviewed and analyzed the data and methodologies that DOD, Commerce, and OMB use to assess and monitor RDP Agreements. For the three objectives, we interviewed DOD, Commerce, OMB, State, and USTR officials to obtain information on RDP Agreements, processes for entering into and renewing RDP Agreements, and the methodologies used to assess and monitor RDP Agreements. We also interviewed a U.S. defense industry association which represents both large defense prime contractors and small business defense contractors, as well as an association of foreign officials from several RDP partner countries to gather their perspectives on RDP Agreements. Appendix I contains a more detailed description of our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

According to DOD, the purpose of RDP Agreements is to enhance the U.S.’s mutual military readiness and promote standardization and interoperability of conventional defense equipment with allies and other friendly governments. RDP Agreements are intended to also create more favorable conditions for defense procurements between countries. Under these agreements, each country provides the other country certain defense procurement benefits on a reciprocal basis, consistent with national laws and regulations. RDP Agreements encourage RDP partner countries to strengthen their defense relationships with the U.S., improve U.S. access to critical resources, and provide valuable opportunities for U.S. defense companies in international markets, according to DOD.

U.S. agencies have distinct responsibilities regarding RDP Agreements, several of which are statutory:

· Defense: DOD’s Office of Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy (DPCAP) manages RDP Agreement activities. Its responsibilities include fact finding on the feasibility of entering into an RDP Agreement with partner countries and negotiating and concluding new and renewed RDP Agreements. In addition, DPCAP coordinates with various stakeholders within DOD and across the federal government to receive input and approval when entering into or renewing an RDP Agreement. Within DOD, officials stated that the Office of International Cooperation is to ensure that RDP Agreements conform to federal standards and practices and provide approval to DPCAP to negotiate and conclude RDP Agreements. DOD is statutorily required to consider the effects of existing or proposed RDP Agreements on U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base.[6]

· Commerce: Within the Department of Commerce, officials stated that the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) is responsible for reviewing RDP Agreements to determine the commercial implications of an RDP Agreement and the potential effects of the agreement on the international competitive position of U.S. industry.[7] If Commerce has reason to believe that the RDP Agreement has, or threatens to have, a significant adverse effect on the international competitive position of U.S. industry, by statute, the Secretary may request an interagency review of the RDP Agreement.[8]

· State: Within the State Department, the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs/Office of Regional Security and Arms Transfers and the Office of the Legal Advisor review RDP Agreements to assess whether the agreements contain any elements that could raise policy or legal concerns.[9]

· Office of Management and Budget (OMB): OMB’s Made in America Office is statutorily required to review, among other things, RDP Agreements to assess whether domestic entities will have equal and proportional access to RDP partner defense markets.[10]

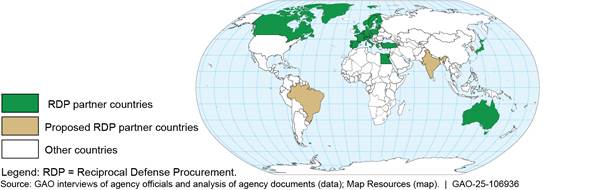

The United States has RDP agreements with 28 countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. These countries, with the exception of Egypt and Turkey, are parties to the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA) and, according to USTR officials, have transparent procedural obligations and reciprocity in market access with the United States.[11] In addition, according to DOD officials, as of November 2024 DOD was in preliminary discussions to negotiate RDP Agreements with India, Republic of Korea, and Brazil, which we refer to as proposed RDP partner countries.[12] India and Brazil are not parties to the WTO GPA. See Figure 1 for a map of current and proposed RDP partner countries.

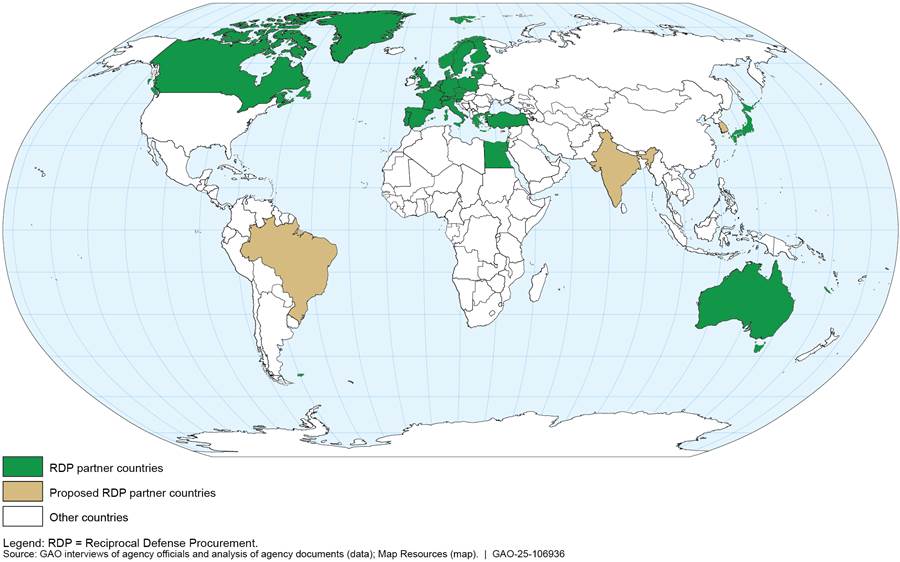

On average, between 2019 and 2023, the U.S. sold an estimated $9.7 billion

annually in defense items to the 28 RDP partner countries, while the U.S.

purchased an estimated average of $5.2 billion annually in defense items from

these 28 partner countries. These countries represented about 84 percent of

imports and half of total U.S. defense exports from 2019 through 2023 (see

figure 2). The top three countries accounted for about half of U.S. defense

item imports from RDP partner countries and about 40 percent of U.S. exports to

RDP partner countries.[13]

RDP Agreements are intended to mitigate restrictions related to international contracting. They provide both countries with increased access to each other’s defense markets and industrial bases. DOD estimates that it relies on over 200,000 contractors to produce advanced weapon systems, such as the F-35 fighter, CH-47F helicopter, and DDG 1000 destroyer, as well as to procure a variety of noncombat goods such as equipment, clothing, and textiles.[14] These contractors comprise the defense industrial base, which includes prime contractors, major subcontractors, and suppliers of parts, components, and raw materials. These contractors can be U.S.- or foreign-owned, with manufacturing facilities located domestically or outside the U.S.

RDP Agreements include provisions for both countries to waive buy-national requirements or other procurement regulations.[15] For the U.S., this means that the Secretary of Defense waives application of the Buy American Act, restrictions on DOD procurement of certain specialty metals, and the Balance of Payments Program. The Buy American Act generally requires federal agencies to procure domestic end products for public use.[16] The restrictions on DOD procurement of specialty metals applies to purchases directly by DOD or a prime contractor.[17] The Balance of Payments Program generally requires only domestic end products to be acquired for use outside the United States, and only domestic construction materials for construction performed outside the United States.[18] The Balance of Payments Program does not restrict the acquisition of services or petroleum products.

Most RDP Agreements Contain Similar Provisions and Extend Automatically

Through a review of all 28 RDP Agreements in place as of March 2024, we found that most agreements contain similar key provisions.[19] For example, all agreements include provisions related to removing barriers to trade, providing reciprocal treatment to industrial enterprises of the other country, or waiving “buy national” laws. In addition, most RDP Agreements have been in place for decades. Two-thirds of agreements include an automatic extension provision. In at least one case, DOD continues to waive the Buy American Act for an RDP partner country (Italy) whose RDP Agreement expired in May 2019.

Most RDP Agreements Contain Similar Key Provisions, With a Few Notable Variations

We found that all agreements include provisions related to removing barriers to trade, providing reciprocal treatment to industrial enterprises of the other country, or waiving “buy national” laws. For example, the RDP Agreement with Australia states that each government shall “accord industries of the other government treatment no less favorable in relation to procurement than that accorded to industries of its own country.” We also found that all agreements broadly identify the types of acquisitions covered. For example, the RDP Agreement with Finland states that the agreement covers the acquisition of defense capability by DOD and the Ministry of Defense of the Republic of Finland through a) research and development; b) procurements of supplies, including defense articles; and c) procurements of services, in support of defense articles.

A large majority of agreements have provisions on protecting proprietary rights and classified information and annually exchanging data on purchases made under the agreements.[20] For example, the RDP Agreement with Poland states that each party shall give full protection to proprietary rights and to any privileged, protected, export controlled, or classified data and information. Similarly, the RDP Agreement with Egypt states that a joint DOD-Egypt Ministry of Defense committee will provide an annual financial statement of the current status of procurement under the agreement, among other responsibilities.

Despite many similarities, there were some notable variations among RDP Agreements. For example, while 21 of 28 agreements have provisions identifying the types of acquisitions specifically not covered under the agreements, the remaining seven do not. A common category of procurement not covered under the RDP Agreements is construction or construction materials. Similarly, 21 of 28 agreements have provisions on both signatories aiming for long-term equitable balance or equitable opportunity in both countries’ purchases under the agreements. For example, the RDP Agreement with Japan states that each participant will facilitate defense procurement while aiming at a long-term equitable balance in their purchases. However, seven agreements (Australia, Canada, Egypt, Israel, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Turkey) do not have these provisions.

While none of the RDP Agreements prohibit offsets, 22 of 28 agreements include provisions agreeing to discuss measures to limit any adverse effects of offsets.[21] An example of this type of provision is in the RDP Agreement with France, which states that the governments will discuss measures to limit the adverse effects of offsets on the defense industrial base of each country. The RDP Agreements with Belgium, Canada, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Turkey do not contain these provisions.

Most RDP Agreements Have Been in Place for Decades and Extend Automatically

The oldest RDP Agreement is with Canada and was originally signed and effective in 1956. Several other agreements originally became effective over 40 years ago, including the agreements with France, Germany, and Italy. The only new RDP Agreement in the past five years was signed and made effective with Lithuania in 2021.

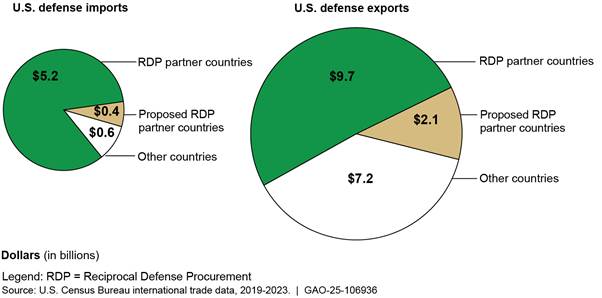

As shown in figure 3, 19 of 28 agreements include an automatic extension provision.[22] The 19 RDP Agreements with an automatic extension provision indicated that it would remain in force without having to be renewed, unless the parties terminate the agreement. According to DOD officials, an RDP agreement has never been terminated.

Figure 3: Reciprocal Defense Procurement (RDP) Agreements by Original and Most Recently Renewed Effective Dates and Inclusion of Automatic Extension Provisions

aItaly’s RDP Agreement expired in 2019.

bSpain’s RDP Agreement does not contain a provision on the duration of the agreement. Therefore, we have categorized the agreement as not containing an automatic extension.

cWhile the 1997 renewal of Greece’s RDP Agreement includes an automatic extension provision, it also states that the agreement will remain in force only for so long as the 1990 Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement (MDCA), or any successor agreement, remains in force. The 1990 MDCA is in force through May 2027 and will continue in force thereafter unless terminated by either party.

DOD Waives Buy American Act for RDP Partner Countries, Even If Agreement Has Expired

As discussed earlier, DOD waives application of the Buy American Act and the Balance of Payments Program for products acquired from the 28 RDP partner countries. The RDP partner country waivers are implemented through the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS).[23] The DFARS implements and supplements the Federal Acquisition Regulations which provides agencies with standardized acquisition policies and procedures for acquiring products and services.[24] According to DOD officials, DOD follows the regulations and policies in DFARS to acquire products and services from contractors in RDP partner countries.

When DOD waives the Buy American Act, the act’s restrictions are not applied to RDP partner countries. For example, in general DOD must add 50 percent to the prices of any low offers when the domestic offer price is not the low offer.[25] But with the restrictions of the Buy American Act waived, contractors in RDP partner countries avoid the 50-percent DOD-added price differential applied to their DOD offers and bids. Consequently, contractors in RDP partner countries may be in a better position to bid on and win DOD contracts than contractors in foreign countries without RDP Agreements. In addition, certain products are generally considered domestic under the Buy American Act if they are manufactured in the United States and the costs of components manufactured in the U.S. exceeds 65 percent.[26] When DOD waives these restrictions, U.S. defense contractors can source goods from RDP partner countries and have these goods considered U.S. domestic end products.

According to DOD officials, even if a partner country has an expired RDP Agreement, DOD can continue to waive the restrictions of the Buy American Act.[27] For example, based on our review of the agreement and according to DOD officials, the RDP Agreement with Italy expired in May 2019 and is no longer in force, with no new agreement or renewal. According to DOD officials, DOD has attempted to sign a new RDP Agreement with Italy but thus far has been unsuccessful. DOD has nonetheless continued to waive the Buy American Act with Italy.[28] DOD officials also noted that that Italy seems to be abiding by the spirit and intent established in the now-expired RDP Agreement, even though the Italian government is not required to do so.

DOD officials emphasized that removing a country from the list of RDP partner countries in DFARS could have significant negative effects on DOD. This is because many DOD contracts contain Buy American Act terms and conditions that are priced and performed with foreign approved suppliers. If any of those foreign approved suppliers were from a country removed from the list of RDP partner countries, it could jeopardize the performance and stability of any associated contracts. More broadly, according to DOD officials, removing a country from the list of RDP partner countries in DFARS could result in significant changes to cost, performance, and schedules of DOD contracts and could have severe national security implications.

DOD Does Not Have Written Policies and Procedures to Initiate and Renew RDP Agreements

DOD Does Not Have Written Policies and Procedures for Initiating and Renewing RDP Agreements

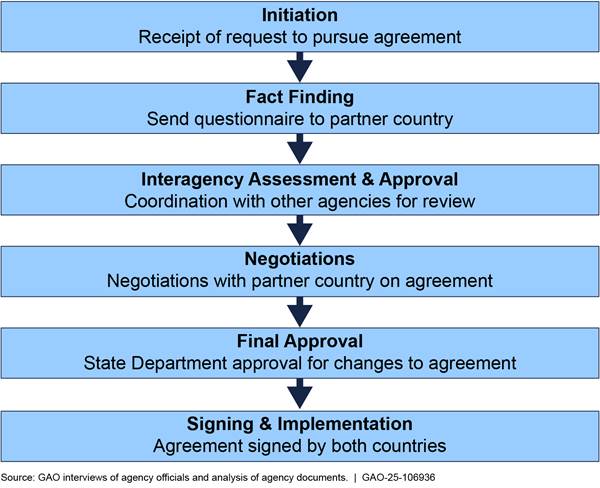

We found that DOD does not have written policies and procedures specific to initiating and renewing RDP Agreements. Instead, DOD’s DPCAP follows a general process for initiating and renewing RDP Agreements, which involves coordination both within and outside DOD. This general process involves several due diligence steps and roughly follows agencywide guidance on executing international agreements.[29] We determined that DOD’s general process follows six stages: initiation, fact finding, interagency assessment and approval, negotiations, final approval, and signing and implementation.[30] According to DOD, completing these stages typically takes one year. See figure 4.

Figure 4: Department of

Defense Stages to Initiate and Implement Reciprocal Defense Procurement

Agreements

In the initiation stage, DPCAP receives a request from DOD, the White House, or a potential partner country to pursue an RDP Agreement. In most cases, DPCAP coordinates with the National Security Council to ensure that an RDP Agreement with the potential partner country is consistent with the Administration’s policies and priorities. In the fact finding stage, DPCAP assesses the feasibility of an RDP Agreement with the potential partner country. DPCAP’s fact finding efforts include sending the partner country a questionnaire to seek information about the potential partner country’s acquisition process, posting a Federal Register Notice to request industry feedback, and estimating the 10-year balance of defense trade between the U.S. and the potential RDP partner country. DCPAP may also contact Commerce, USTR, or other DOD officials to better understand the potential RDP partner country’s procurement policies and practices. According to DOD and OMB officials, U.S. agencies are considering revisions to their approach for considering potential new proposed RDP countries. These revisions include soliciting more input from U.S. government stakeholder agencies prior to negotiations with foreign government officials.

If DPCAP determines that an RDP Agreement is feasible, DPCAP enters the interagency assessment and approval stage and requests approval by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Industrial Base Policy, International Cooperation. International Cooperation’s review involves coordination with other DOD stakeholders, State, and Commerce. After receiving International Cooperation’s approval, DPCAP enters into negotiations with the potential RDP partner country.

During negotiations of RDP Agreements since 2018, including renewals and initiated agreements, DPCAP’s objective has been to make the partner country comfortable with the language in a State-approved template RDP Agreement.[31] If DPCAP negotiates substantive changes to the template, DPCAP requests State’s approval of the changes. Since the RDP Agreement is considered an international agreement, DOD must coordinate with State to ensure the agreement complies with State’s governmentwide procedures on executing international agreements during the final approval stage. DPCAP produces a Determination and Findings Exception to the Buy American Act, which justifies exceptions to the Buy American Act under the RDP Agreement, for the Secretary of Defense. Lastly, to begin the signing and implementation stage, both countries sign the RDP Agreement, and the Secretary of Defense also signs the Determination and Findings Exception to the Buy American Act to complete the final approval stage. DPCAP submits the concluded RDP Agreement to State, which serves as the official repository for agreements with foreign nations. The RDP Agreement is then concluded, indicating that the U.S. and the new RDP partner country can conduct defense procurements that enhance their mutual military readiness.

According to DOD officials, renewals follow the same steps as initiations, with a few minor differences. First, DPCAP reaches out to RDP partner country officials about two years before the RDP Agreement expires. Second, DPCAP does not coordinate with USTR officials, unless DOD determines there is a specific issue requiring USTR’s expertise. USTR officials stated that DPCAP has never reached out to USTR to express DPCAP’s intent to renew an agreement or seek USTR’s expertise on renewal. Finally, DPCAP officials told us that the original Determination and Findings Exceptions to the Buy American Act remains in effect for the renewal.

DOD Did Not Solicit Industry Input for Recent RDP Agreements

Since 1988, DOD has been statutorily required to consider the effects of existing or proposed RDP Agreements on the U.S. defense technology and industrial base.[32] To consider the effects of renewed and proposed RDP Agreements, DPCAP officials told us that they solicit public comments in the Federal Register. However, DPCAP could not provide documentation that it posted a Federal Register Notice for three out of the four agreements renewed since 2019, nor did our search of the Federal Register website identify any notices, for three RDP Agreement renewals:[33]

· Luxembourg (2020)

· Czech Republic (2022)

· Poland (2023)

As a result of not posting them, DOD did not afford the defense industry the opportunity to provide comments on these proposed RDP Agreements using its stated method.

Further, while DOD Instruction 5530.03, “International Agreements” and the Guide to DOD International Acquisition and Exportability Practices establish DOD-wide guidance for DOD to approve, initiate, and conclude international agreements, DOD does not have written policies and procedures specific to initiating and renewing RDP Agreements. Instead, DOD officials rely on their experience executing RDP Agreements to guide the steps they follow to initiate and renew RDP Agreements. According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, U.S. agencies should establish policies and procedures that meet objectives and respond to risks and review those policies and procedures periodically.[34]

The absence of established written policies and procedures specific to initiating and renewing RDP Agreements may have contributed to DOD not soliciting industry input using the Federal Register for three of the recent agreements. Without this input, DOD missed opportunities to collect firsthand information from U.S. defense industrial base suppliers that would help assess the potential effect on U.S. industry for these agreements.

DOD Did Not Always Coordinate with Commerce, As Required, For Renewing RDP Agreements

DOD is statutorily required to regularly solicit and consider comments and recommendations from Commerce on the commercial implications of an RDP agreement and the potential effects of the agreement on the international competitive position of U.S. industry.[35] DOD officials stated that during the initiation and renewal process, International Cooperation is responsible for coordinating with Commerce on its review. Once International Cooperation completes coordination with the required stakeholders, International Cooperation authorizes DPCAP to negotiate the terms of the RDP Agreement and ultimately conclude the agreement.

DOD’s Office of International Cooperation generally provides Commerce 15 to 21 days to complete its review of an RDP Agreement, including for a renewal of an RDP Agreement. If Commerce does not respond to DOD within the deadline, DOD considers the RDP Agreement approved. However, according to Commerce officials, Commerce can request more time if needed.

However, we found that DOD did not follow DPCAP’s typical steps coordinating with Commerce or soliciting industry input before renewing RDP Agreements for four out of five recent agreements. For example, DPCAP and International Cooperation have no record of coordination with Commerce on the 2018 renewal of the Finland RDP Agreement and Commerce found no record that it reviewed the agreement when it was up for renewal. According to Commerce records, Commerce’s last review of Finland’s RDP Agreement was in 2007.

Soliciting and receiving Commerce’s analysis is important to help DOD determine the benefits and risks of the RDP Agreements. The absence of established written policies and procedures for Commerce and DOD specific to initiating and renewing RDP Agreements may have contributed to DOD not coordinating with Commerce on its review. In lieu of established policies and procedures, DPCAP officials rely on their experience to guide the steps they followed to initiate and renew RDP Agreements. But without written policies and procedures specific to RDP Agreements, DOD and Commerce are unable to ensure that the required coordination and review were completed for all RDP Agreements. Without these reviews, DOD has missed opportunities to collect information to determine whether these agreements will help or hurt U.S. industry.

Agencies Do Little to Assess and Monitor Effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. Industry

While DOD is responsible for RDP Agreements, DOD’s efforts to assess and monitor the effects of proposed or existing RDP Agreements are limited. Instead, DOD relies primarily on Commerce, but Commerce’s methodology to assess the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. industry has several weaknesses. Further, DOD has not asked Commerce to monitor RDP Agreements and Commerce does not have guidance to determine if it should seek an interagency review of the RDP Agreement to determine if the commercial interests on the United States are being served. Finally, at the time of our review OMB’s Made in America Office had not established a plan on how it will conduct required reviews of RDP Agreements.

DOD Efforts to Assess and Monitor RDP Agreements Are Limited

DOD Has Only Conducted Assessments for Some RDP Agreements

Of the 28 RDP Agreements we reviewed, we found that DOD only conducted assessments of the effects on the U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base for RDP Agreements when they were originally signed and when they were renewed. Specifically:

· 11 of the 28 RDP Agreements were originally signed and became effective after the 1988 requirement that DOD consider the effects of existing or proposed RDP Agreements on the U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base was enacted.[36] In contrast, 17 of 28 RDP Agreements predate the 1988 requirement.

· 19 of the 28 RDP Agreements have automatic extension provisions and DOD would not have assessed these agreements since they were last renewed or originally signed. For example, the RDP Agreement with Germany was originally signed and became effective in 1978 and renewed in 1991 with automatic extension provisions; DOD would not have assessed this agreement since 1991. In addition, the agreements with Turkey, Belgium, and Portugal, were originally signed and effective over 40 years ago and have automatic extension provisions and were never renewed.

As a result, for some RDP Agreements, DOD might not ever have assessed, or not assessed for a long time, the effects of the RDP Agreement on the U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base.

DOD Receives Few Public Comments

As mentioned previously, to consider the effects of renewed and proposed RDP Agreements on U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base, DPCAP officials said that they request input from U.S. industry by seeking public comments via Federal Register Notices. For example, DOD asks that U.S. firms that have participated or attempted to participate in procurements by the partner’s Ministry of National Defense inform DOD if the procurements were conducted with transparency, integrity, fairness, and in accordance with published procedures, and if not, the nature of the problems encountered. DOD also asks industry about the degree of reciprocity that exists between the United States and the partner country when it comes to the openness of defense procurement to offers of products from the other country. DOD officials characterized this input as one of the most effective tools available to ensure that domestic entities have equal and proportional access to partner country defense markets.

Between 2018 and 2024, DOD published Federal Register Notices for five partners—Japan, Lithuania, Brazil, India, and Republic of Korea. We obtained and reviewed all 13 public comment letters that DPCAP officials received in response. Twelve of the 13 comments were for the three proposed RDP Agreements with Brazil, Republic of Korea, and India, and the remaining one related to renewal of Japan’s RDP Agreement.[37] Of the 13 comments received, six were in favor of the agreement and the other seven were opposed. These comments described potential negative effects of an RDP Agreement. Table 1 provides additional detail.

Table 1: Summary of All Public Comments DOD Received on Reciprocal Defense Procurement (RDP) Agreements Between 2018 and 2024

|

Country |

Date Federal Register Notice was Posted |

Comments Received |

In Favor of Agreement |

Opposed to Agreement |

|

|

Japan (renewed) |

March 2021 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Lithuania (new) |

November 2021 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Brazil (proposed) |

September 2023 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

India (proposed) |

October 2023 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

Republic of Korea (proposed) |

February 2024 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Total |

|

13 |

6 |

7 |

|

Source: Federal Register Notices and Department of Defense

documentation. | GAO‑25‑106936

Note: DOD signed RDP agreements with Luxembourg in 2020,

the Czech Republic in 2022, and Poland in 2023, but did not request public

comment via Federal Register Notices.

Whether in favor or opposed, seven of the 13 comments either did not provide the requested information or were not from U.S. industry representatives. As a result, they provided only limited insight about the potential effects of the agreements on U.S. industry. In addition, as stated previously, DOD did not publish Federal Register Notices for three countries—Luxembourg, the Czech Republic, and Poland. As a result, in those instances U.S. industry had no opportunity to comment.

DOD Estimates of Defense Trade with RDP Countries Have Limitations

DPCAP officials said they estimate the annual balance of trade between the U.S. and RDP partner countries to assess and monitor the effects of RDP Agreements. According to DPCAP, this estimate is how they attempt to ensure domestic entities have equal and proportional access to RDP partner defense markets, which is a key goal of the agreements.

DPCAP annually estimates the balance of trade using three data sources. With this information, DPCAP populates a spreadsheet that contains aggregated values for DOD procurements, U.S. foreign military sales, and direct commercial sales, by year for each RDP partner country and proposed RDP partner country.[38] To estimate imports (what DOD buys from RDP partner countries), officials use data on DOD procurement extracted from USAspending.gov, which includes data from the Federal Procurement Data System. To estimate exports (what U.S. industry sells to RDP partner countries), DPCAP uses information from publicly available reports about direct commercial sales and foreign military sales to RDP partner countries.[39]

However, we identified limitations related to the accuracy and completeness of the data that DOD uses to estimate the balance of trade between the U.S. and RDP partner countries. For example, we identified errors in the fiscal year 2022 Historical Sales Book for Foreign Military Sales which resulted in the underreporting of foreign military sales to RDP partner countries by approximately $15 billion.[40] In another example, DOD uses data extracted from USAspending.gov without excluding grants, other foreign assistance, or construction contracts for their estimates. Grants and foreign assistance from the U.S. government, as well as construction contracts, are generally not covered under RDP Agreements.

DPCAP relies on publicly available data on defense trade because it generally does not receive procurement data from RDP partner countries. Twenty-four of the 28 RDP Agreements include a standard provision that the U.S. and its partner country are to exchange data about the value of RDP procurements on an annual basis. However, DPCAP officials told us that they usually do not request or receive any data, and the data they receive are not useful or in a comparable format.

Since 1988, DOD has been statutorily required to consider the effects of existing or proposed RDP Agreements on U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base.[41] Agencies benefit from standardized, documented policies and guidance to achieve objectives.[42] However, DOD does little to assess and monitor the actual effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base. Further, DPCAP officials stated that there are no DOD implementation policies, procedures or guidance. Without establishing policies, procedures, or guidance to assess and monitor the effects of RDP Agreements, the U.S. government may miss opportunities to help ensure that RDP Agreements are beneficial to the U.S. defense industry.

Commerce Conducts Limited Assessment and No Monitoring of RDP Agreements

Commerce’s Methodology to Assess the Effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. Industry Has Weaknesses

DOD relies on Commerce to assess the potential effects of RDP Agreements on the international competitive position of U.S. industry. However, we found that Commerce’s methodology for assessing the extent to which an RDP Agreement may affect the international competitive position of U.S. industry has several weaknesses. According to GAO’s Assessment Methodology for Economic Analysis, agencies need to use sound methodology to provide appropriate and accurate economic assessments.[43]

We analyzed assessments that Commerce’s BIS provided to DOD approving seven RDP agreements between 2018 and 2021 and found they did not include rigorous analysis or support.[44] For example, BIS documentation during this time frame stated that renewals of existing RDP Agreements are administrative in nature and BIS does not complete a full assessment in these cases.[45]

BIS issued RDP Agreement review guidance in October 2021 to make its review of RDP Agreements more robust.[46] In the guidance, BIS describes the steps it takes to conduct RDP Agreement reviews. These include an internet search of the potential RDP country’s defense industry and a review of DOD’s Foreign Entities report.[47] BIS assesses the potential effects of an RDP Agreement primarily by estimating the defense trade balance between the U.S. and the prospective RDP partner country, using Census defense trade data.[48] Since 2021, BIS has applied this methodology in its assessment of one RDP Agreement with Lithuania and determined that the agreement did not have, or threaten to have, a significant adverse effect on the international competitive position of U.S. industry.[49]

We found that the BIS methodology as set forth in the October 2021 guidance has several weaknesses which limit the quality of the information BIS provides to DOD. The weaknesses we identified include:

1. No comparisons between baseline and relevant alternatives: According to our assessment methodology for economic analysis, a methodology used to examine economic effects should consider establishing a baseline and then comparing it to all relevant alternatives.[50] However, the BIS methodology does not establish a baseline and compare it to relevant alternatives. To analyze the effect of an RDP Agreement, a reasonable methodology could include comparing the baseline of the U.S. defense industry without an RDP Agreement to the alternative scenario of a U.S. defense industry with an agreement. Additionally, the methodology does not consider differences, if any, in the “buy national” requirements between the U.S. and potential RDP partner countries prior to RDP Agreements, which is an important factor to consider in establishing the baseline. The effect on U.S. industry of entering into an agreement with a country which has “buy national” requirements is likely to be different than an agreement with a country with no similar requirements. For example, the DOD Determination and Findings document for the Czech Republic states that the Czech Republic did not have buy-national legislation equivalent to the Buy American Act when it entered into an RDP Agreement with the U.S. in 2012.

2. No empirical support for key assumptions or conclusions based on trade balance: BIS methodology specifies that if the U.S. sells more goods to the foreign partner than the foreign partner sells to the U.S., that is, if the U.S. has a trade surplus with the partner country, the data would indicate that signing an RDP Agreement and waiving the Buy American Act would likely be of more benefit to the U.S. than the RDP partner country. However, BIS provides no theoretical or empirical support for stating that signing an RDP Agreement will benefit the U.S. defense industry when the U.S. already has a trade surplus with the prospective partner country. Economic theory on the benefit of free trade does not conclude simply that exports are beneficial, and imports are harmful. Instead, the benefit of free trade is derived from more efficient allocation of resources and production. Sales for some businesses may decrease and the trade surplus with a partner country may shrink as the result of an agreement, but the agreement can still be beneficial overall. Researchers have used various methodologies to assess the effect of particular changes, such as lowering tariffs, on trade patterns. These methods help provide empirical evidence of the positive or negative impact of trade.[51] Additionally, benefits from the agreements are broader than increased U.S. exports. DOD’s November 2023 National Defense Industrial Strategy supports this perspective. The goals of the strategy include engaging allies and partners to expand global defense production, increasing supply chain resilience, diversifying the supplier base, and strengthening international defense production relationships.[52] Further, our analysis of Census trade statistics identified instances where a multi-year trade deficit exists for defense items between the U.S. and several RDP partner countries, such as Australia, France, Slovenia, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.[53] However, BIS officials said that because they have only applied this methodology once to date, for the RDP Agreement with Lithuania, they have no precedent to determine what conclusions or recommendations they would make and provide to DOD for countries the U.S. had trade deficits with.

3. No assessment based on market positions: The methodology does not differentiate companies based on their market positions. For example, it does not take into account whether the U.S. company is a supplier with many foreign competitors or a major defense contractor who sources from many smaller suppliers. While some U.S. companies may benefit from better access to foreign suppliers for intermediate goods when restrictions from the Buy American Act are waived, other U.S. companies may face more competition from foreign producers.

4. No analysis of the service sector and certain goods: The methodology does not provide a complete picture of RDP procurement because the data BIS uses do not include services, only goods. This is significant because RDP agreements generally cover both services and goods, and in fiscal year 2022, 49 percent of the value of DOD procurements were for services.[54] Furthermore, purchases under RDP Agreements cover a broader range of goods than what is included in Census’ defense item end-use codes, which BIS uses for its analysis.[55] Analyzing the trade statistics only based on Census’ defense item end-use codes may not fully reflect the effect of the RDP agreements.

BIS officials stated that BIS does not coordinate its reviews of RDP Agreements with the other offices in Commerce that have relevant expertise, such as the International Trade Administration (ITA) officials at Commerce headquarters or Foreign Commercial Service officers at U.S. embassies in prospective RDP partner countries. Additionally, BIS does not consult with the Office of the Under Secretary for Economic Affairs, which is tasked with coordinating economic analysis needs within Commerce. According to BIS officials, BIS does not have the data or resources to assess the service sector nor the ability to do advanced economic modeling. BIS also noted that consulting with other divisions within Commerce would require more time than the 15 to 21 days DOD generally provided BIS to review proposed RDP Agreements. The challenges expressed by BIS make clear the need for DOD to coordinate with BIS and other offices in Commerce in developing and implementing policies, procedures, and guidance to properly assess the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base. Such policies and procedures could include identifying expertise required and establishing an appropriate deadline for Commerce to complete the assessment on which DOD currently relies.

According to DPCAP officials, DPCAP would benefit from more rigorous analysis from Commerce for a proposed RDP Agreement country. Internal control standards for federal agencies emphasize that agencies should use quality information to achieve the agency’s objectives.[56] Because Commerce has not provided thorough, complete, and quality information to assess the potential effects of RDP Agreements, DOD has executed RDP Agreements without being fully informed about whether RDP Agreements will achieve their stated goals or be beneficial to the U.S. defense industrial base.

Commerce Does Not Monitor RDP Agreements

In negotiating, renegotiating, and implementing RDP Agreements, DOD is statutorily required to regularly solicit and consider comments and recommendations from Commerce with respect to the commercial implications of RDP Agreements and the potential effects on the international competitive position of U.S. industry.[57] Commerce does not monitor RDP Agreements, nor has it conducted any assessment of the effects of existing RDP Agreements. However, BIS officials stated that they would be willing to be more involved in these efforts in the future. Commerce’s BIS officials stated that DOD is responsible for monitoring RDP Agreements and has not asked Commerce’s BIS to be involved in monitoring. However, as noted in the previous section, DOD does not have any specific implementation policies, procedures, or guidance, including how DOD should solicit Commerce’s input about RDP Agreements once they have been implemented.

In addition, Commerce has the authority to request an interagency review of the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. industry.[58] However, Commerce’s BIS officials stated that they have never deemed this necessary. Without monitoring the effects of RDP Agreements on the international competitive position of U.S. industry, it is unclear how Commerce would identify the need to request an interagency review. Further, BIS officials stated that they have no guidance or process for doing an interagency review because they have never conducted one before.

Because the U.S. government is currently considering signing RDP Agreements with three proposed RDP partner countries—Brazil, Republic of Korea, and India—DOD would benefit from regularly soliciting and considering comments and recommendations from Commerce with respect to the commercial implications of RDP Agreements.

OMB Had Not Established a Plan for Reviewing RDP Agreements

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) established MIAO within OMB in November 2021. The IIJA requires MIAO to review RDP Agreements to assess whether domestic entities will have equal and proportional access to RDP partner defense markets and report its findings to the Director of OMB, the Secretary of Defense, and the Secretary of State.[59] Outside of RDP Agreements, its responsibilities also include enforcing compliance with domestic preference statutes and reviewing agency waiver requests to domestic preference statutes. One of MIAO’s goals is to bring increased transparency to waivers to send clear demand signals to domestic producers.[60]

MIAO has yet to formally review any RDP Agreements that were entered into after November 15, 2021, as required. MIAO and DPCAP officials said that DOD did not request MIAO to review any RDP Agreements that have been entered into since the enactment of the IIJA prior to signing the agreements.[61] DPCAP officials have provided information to MIAO about RDP Agreements. This information included a description of how the RDP review process works and an estimate of the balance of trade between the U.S. and partner countries.[62] MIAO officials stated that they would work closely with DOD on future proposed RDP Agreements to ensure they provide domestic entities with equal and proportional access and that Made in America goals are considered. DOD is coordinating with the White House, including MIAO and the National Security Council, to update the interagency process to conduct RDP Agreement reviews, according to DPCAP and MIAO officials. These updates would apply to any potential future RDP Agreements. However, the changes to the interagency process have not been finalized, and a specific timeline has not yet been established.

At the time of our review, MIAO had not established a written plan on how it will carry out its review of RDP Agreements once the office is integrated into the interagency process. Issuing a written plan or guidance could help MIAO officials gain clarity on how they will assess whether domestic entities will have equal and proportional access to RDP partner defense markets and specify how MIAO will obtain information needed to do so. Without a written plan that explains how MIAO will assess RDP Agreements, MIAO risks not being able to effectively and consistently execute its responsibilities related to these agreements.

Conclusions

The U.S. has RDP Agreements with 28 partner countries, including countries such as Japan, Australia, Canada, the U.K., and Germany. Many of the agreements contain provisions that could be helpful for promoting the trade of defense items, such as provisions related to removing barriers to trade or waiving “buy national” laws. But DOD does not have written policies and procedures for initiating and renewing RDP Agreements, and, in practice, has not consistently executed steps in its general process for initiating and renewing RDP Agreements that are intended to ensure that the potential effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. industry and international competitiveness are properly considered. Specifically, since 2019, three out of four of RDP Agreements were renewed without input from industry and DOD did not coordinate with Commerce, as required, for one of five recent agreement renewals. DOD is required to assess and monitor RDP Agreements, but relies on Commerce, whose guidance for assessing effects has weaknesses. As a result, the U.S. government has entered into or renewed RDP Agreements on the basis of limited information about the effects of such agreements on U.S. industry.

DOD and Commerce need established policies and procedures to better monitor and assess RDP Agreements. Commerce could improve the quality of its assessment by addressing weaknesses in its methodology. Additionally, OMB had not established a written plan on how it will carry out its review of RDP Agreements. Unless DOD and Commerce establish appropriate policies and procedures, and do more to assess and monitor RDP Agreements, the U.S. government cannot be sure whether these agreements are achieving their purposes and helping or hurting U.S. industry.

Recommendations for Executive Action

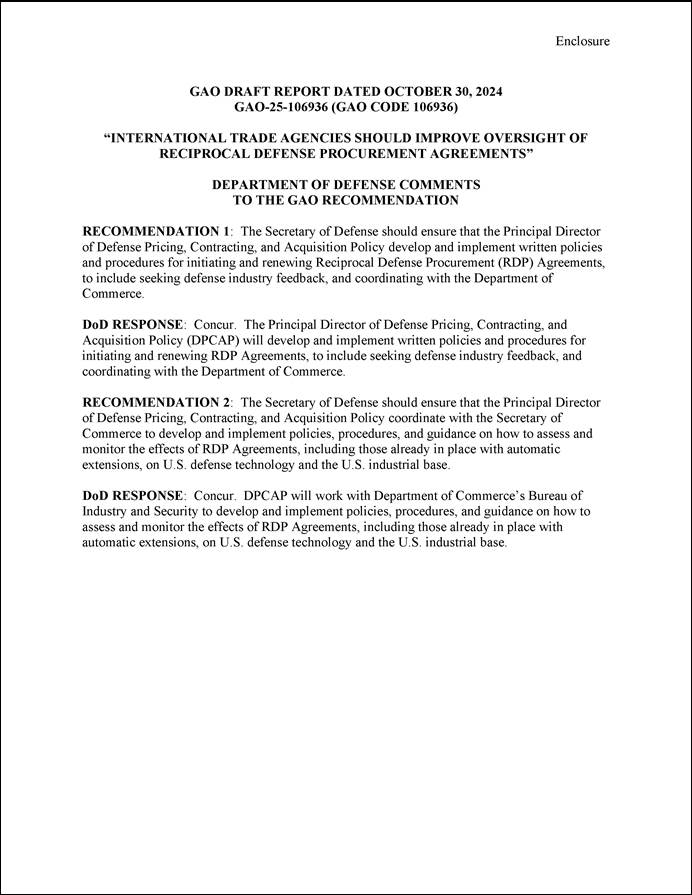

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Principal Director of Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy develops and implements written policies and procedures for initiating and renewing RDP Agreements, to include seeking defense industry feedback, and coordinating with the Department of Commerce.

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Principal Director of Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy coordinates with the Secretary of Commerce to develop and implement policies, procedures, and guidance on how to assess and monitor the effects of RDP Agreements, including those already in place with automatic extensions, on U.S. defense technology and the U.S. industrial base.

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that the Bureau of Industry and Security, in consultation with other appropriate offices within Commerce, updates guidance to address weaknesses in its methodology assessing the potential effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. industry so that it is based on sound economic reasoning and rigorous methodology and leverages the expertise of other appropriate offices within Commerce.

The Office of Management and Budget should direct the Director of the Made in America Office to develop a written plan or guidance on how it will review RDP Agreements.

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report for review and comment to DOD, Commerce, State, USTR, and OMB. State and USTR did not provide comments. DOD and Commerce concurred and OMB partially concurred with our recommendations. In a response provided via email, the OMB liaison to GAO stated that OMB has recently developed an internal plan for the evaluation of RDP agreements; however, it does not intend to issue written guidance. While this is a promising first step, we continue to maintain that it is important for OMB to document a plan on how it will assess domestic entities’ equal and proportional access to RDP partner defense markets. DOD provided an official comment letter, which is reprinted in appendix II. Commerce and OMB provided technical comments on our draft, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretaries of Defense, Commerce, and State, the United States Trade Representative, and Director of the Office of Management and Budget. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Tatiana Winger at (202) 512-4128 or wingert@gao.gov or William Russell at 202-512-4841 or russellw@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Tatiana Winger

Acting Director, International Affairs and Trade

William Russell

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

This report examines (1) the provisions of Reciprocal Defense Procurement (RDP) Agreements and how the agreements vary among RDP partner countries, (2) the degree to which U.S. agencies have developed and followed processes in place for the initiation and renewal of RDP Agreements, and (3) the extent to which U.S. agencies have monitored and assessed the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. industry.

For the first objective, to identify the provisions of RDP Agreements and how the agreements vary among RDP partner countries, we reviewed documents from the Department of Defense (DOD) and the Department of State and interviewed DOD officials. We reviewed all 28 current RDP Agreements as of March 2024.[63] We accessed the RDP Agreements from DOD’s publicly available website (https://www.acq.osd.mil/asda/dpc/cp/ic/reciprocal‑procurement‑mou.html). For one RDP Agreement (Luxembourg), DOD emailed us the latest updated version of the agreement, which we then reviewed. To determine the key provisions of RDP Agreements, we reviewed and analyzed the contents of all 28 agreements and interviewed DOD officials to capture their perspectives on which were the key provisions. To identify which agreements contained key provisions and which did not, we developed an assessment tool that listed key provisions contained in RDP Agreements, such as removing barriers to trade, protecting classified information, and annually exchanging data on purchases made under the agreements. To analyze the contents of all 28 agreements and use the tool to record which RDP Agreements contained key provisions and which did not, we used a methodology wherein a GAO analyst produced an initial assessment of an RDP Agreement and second GAO analyst reviewed that assessment. After all initial assessments and reviews were completed, the GAO team of analysts discussed and resolved any discrepancies between the initial assessment and the review. Subsequently, GAO legal experts completed their own review of the assessments in the tool. We then revised assessments to resolve any discrepancies identified by the legal experts.

For the second objective, to examine the degree to which U.S. agencies have followed processes in place for the initiation and renewal of RDP Agreements, we first determined agency roles and responsibilities for initiating and renewing RDP Agreements. To determine those roles, we reviewed DOD’s Office of Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy (DPCAP) documents outlining the RDP Agreement process. We also reviewed DOD guidance such as DOD Instruction 5530.03 “International Agreements” and statutory requirements in 10 U.S.C. 4851. We interviewed DOD, State, Department of Commerce, U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) officials to get a better understanding of their roles and responsibilities. We also interviewed organizations outside federal government. We met with a U.S. defense industry association, the National Defense Industrial Association, which represents both large defense prime contractors and small business defense contractors. DOD officials identified the National Defense Industrial Association as the industrial defense association most likely to have information related to their members’ experience with RDP Agreements. We also met with officials representing five RDP partner countries to gather their perspectives on RDP Agreements. These officials are members of the Defense MOU Attachés Group. The mission of this organization is to promote reciprocal defense equipment cooperation and defense trade between the U.S. and member nations.

We reviewed guidance from DOD and State to determine the stages of the process to initiate and renew RDP Agreements. We reviewed documents such as DOD Instruction 5530.03 “International Agreements”, State’s Circular 175 (C‐175), and statutory requirements in 10 U.S.C. 4851 to learn about the processes that DOD typically follows for international agreements, which includes RDP Agreements. We also reviewed a document drafted by DPCAP officials as informal guidance on initiating and renewing RDP Agreements that was primarily developed by DPCAP to explain the process to initiate and renew RDP Agreements to other agency officials. We also interviewed officials from DOD, State, Commerce, USTR, and OMB to learn about initiating and renewing RDP Agreements as they move through the stages of the process that include other agencies. For example, officials at Commerce described the process for their review of RDP Agreements, including their concurrence practices.

To determine the extent to which agencies established and followed policies and procedures for initiating and renewing RDP Agreements, we reviewed and assessed DOD’s processes and the steps that U.S. agencies took to initiate and renew RDP Agreements. We reviewed DOD, Commerce, State, and general federal records; for example, we reviewed and analyzed Federal Register Notices to determine if DOD posted Federal Register Notices for the initiation and renewal of each RDP Agreement, as their process calls for. We also analyzed Commerce, State, and USTR records of review and their communications with DOD about the development and approval of RDP Agreements. In addition, we interviewed DOD, State, Commerce, and USTR officials regarding the steps they followed to initiate and renew RDP Agreements. In sum, we reviewed DOD’s processes and the steps that U.S. agencies took to initiate and renew RDP Agreements and compared them to Principles 10 and 12 of the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government. These principles state that U.S. agencies should establish policies and procedures that meet objectives and respond to risks and review those policies and procedures periodically.[64]

To analyze the extent to which U.S. agencies have monitored and assessed the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. industry, we reviewed documents, analyzed relevant data, and interviewed agency officials. We obtained and reviewed each of the 13 public comments DOD received in response to Federal Register notices regarding RDP Agreements between 2018 and April 2024. This includes the 5-year period from 2018-2022 as well as all the public comments in response to the most recent three Federal Register Notices for the three proposed RDP Agreements with Brazil, India, and the Republic of Korea, which as of November 2024 had not yet been signed.

To assess the extent to which Commerce monitored and assessed the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. industry, we requested Commerce documentation of its analysis and approval of RDP Agreements. Commerce provided documentation for a total of 13 RDP Agreements that it reviewed and approved at the request of DOD since 2012.[65]

To evaluate the methodology Commerce used to assess the potential impact of RDP Agreements, we assessed Commerce’s analysis of each of the RDP Agreements that Commerce reviewed between 2018 and 2022 using one of the five elements in GAO’s Assessment Methodology for Economic Analysis, specifically, the methodology used to examine economic effects.[66] We evaluated whether Commerce’s methodology contained certain elements of an economic effect assessment, including a baseline and relevant alternatives. To assess Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security analysis of the trade balance between the U.S. and RDP countries, as well as its conclusions based on this analysis, we analyzed U.S. Census Bureau trade statistics on exports and imports with RDP partner countries and proposed RDP partner countries for 2019-2023.[67] We also used the Census Bureau trade statistics to calculate the trade balance and identify countries with which U.S. had a consistent defense trade deficit or surplus.

To analyze the extent to which DOD assessed and monitored the effects of RDP Agreements on U.S. industry, we evaluated the data and analysis that DOD used to track procurements. DOD used three sources of data: USAspending.gov data, Direct Commercial Sales reports, and Foreign Military Sales reports. We evaluated these data sources for fiscal years 2018-2022:

1. USAspending.gov: We found that the methodology DOD used to analyze this data to estimate RDP related procurement had some weaknesses. For example, USAspending.gov includes both financial assistance data from non-Federal Procurement Data System data sources and procurement data from the Federal Procurement Data System. It did not exclude grants and other financial assistance, and it also did not exclude construction contracts that are not covered under RDP Agreements.

2. State Department Directorate of Defense Trade Controls Section 655 report (Direct Commercial Sales data): We found that this data did not provide a reliable way to estimate RDP related Procurement by RDP partner countries because it does not include any data on goods and services that RDP partner countries procure from U.S. industry for military use that do not require an export license.

3. Department of Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) Historical Sales Book (Foreign Military Sales data): We identified errors in the fiscal year 2022 Historical Sales Book for Foreign Military Sales and brought them to the attention of DSCA officials.[68] These errors prevented us from obtaining a reliable estimate of the total value of foreign military sales to RDP partner countries. DSCA officials stated that they would correct the data in their fiscal year 2023 edition of the report. As of October 2024, DSCA had not provided us corrected data and has not published its fiscal year 2023 Foreign Military Sales Historical Sales Book. In addition, the DSCA official stated that DSCA changed its process to verify the data published in the FMS Historical Sales Book. However, DSCA did not provide evidence of this change or corrected data.

We determined that these data sources were not reliable specifically for the purposes of identifying and reporting on procurement related to RDP Agreements in our report. Specifically, during our audit, we identified some data reliability issues related to the accuracy and completeness of the data that DOD uses to assess and monitor RDP Agreements. These issues prevented us from accurately determining the total value, types of goods and services acquired, and other details to obtain a reliable estimate of procurement related to RDP Agreements. As a result of the issues identified, we determined that the data were not sufficiently reliable for us to present in this report. We shared some of the data reliability issues with DOD to improve their public reporting of foreign military sales and high-level analysis of defense trade with RDP partner countries. Because DOD officials told us that they did not conduct any formal economic analysis of RDP Agreements, we did not assess DOD’s analysis against GAO’s assessment methodology for Economic Analysis.

To assess the process, data, and methodology OMB’s Made in America Office (MIAO) used to review if domestic entities have equal and proportional access to the defense procurement markets of RDP partner countries, we requested documentation of any policies, guidance, recommendations, processes, reviews, analysis, or reports that MIAO had prepared related to its RDP-related roles and responsibilities.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Tatiana Winger, (202) 512-4128 or WingerT@gao.gov

William Russell, (202) 512-4841 or RussellW@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contacts named above, Kim Frankena (Assistant Director), Ian Ferguson (Analyst in Charge), Heather B. Miller, Bridget Jackson, Sam Kim, Ming Chen, Larissa Barrett, Bahareh Etemadian, Adam Cowles, Cheryl Andrew, Samantha Lalisan, Miranda Riemer, Pamela Davidson, Alec McQuilkin, and Suellen Foth made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Countries that have signed RDP Agreements with DOD are hereafter referred to as “RDP partner countries”.

[2]Buy American Act, Pub. L. No. 72-428, 47 Stat. 1520 (1933), codified as amended 41 U.S.C. §§ 8301-8305.

[3]Pub. L. No. 100-456, § 824, 102 Stat. 1918, 2019 (1988), as amended codified at 10 U.S.C. § 4851. For the purposes of this report, existing RDP Agreements include agreements which have been renewed as well as agreements with automatic extension provisions that remain in force without having to be renewed. DOD is also required to regularly solicit and consider comments and recommendations from the Department of Commerce regarding RDP Agreements’ commercial implications and their potential effects on the international competitive position of U.S. industry. 10 U.S.C. § 4851(a)(2).

[4]Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), Pub. L. No. 117-58, § 70923(d)(2), 135 Stat. 429, 1307 (2021).

[5]While USTR does not have a distinct responsibility regarding RDP Agreements, it is responsible for negotiating directly with foreign governments to create trade agreements and to resolve disputes. According to USTR, they also meet with foreign governments, business groups, U.S. legislators and U.S. public interest groups to gather input on trade issues and to discuss U.S. trade policy positions.

[6]10 U.S.C. § 4851(a).

[7]Specifically, DOD is tasked with regularly soliciting and considering comments and recommendations from Commerce. 10 U.S.C. § 4851(a)(2).

[8]10 U.S.C. § 4851(b).

[9]In an August 2018 Action Memo, State granted blanket authority for DOD to negotiate and conclude RDP Agreements under the condition that any substantive changes to the draft agreement text must be approved by State’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs/Office of Regional Security and Arms Transfers, the relevant regional bureau, and State’s Office of the Legal Advisor.

[10]Pub. L. No. 117-58, § 70923(d)(2).

[11]The U.S. and other countries have made commitments under the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA) that open government procurement to foreign suppliers, ensure that the process is conducted transparently, and provide foreign contractors with the same rights as domestic ones. The Agreement also contains general exceptions from GPA obligations. For example, countries typically exclude certain defense and national security-related purchases. For additional information, see: GAO, International Trade: Government Procurement Agreements Contain Similar Provisions, but Market Access Commitments Vary, GAO‑16‑727 (Washington D.C. September 27, 2016).

[12]As discussed later in this report, DOD seeks comments from industry on proposed RDP Agreements via notices in the Federal Register. For the purposes of this report, we included in our scope any proposed RDP partner country for which DOD had issued a Federal Register Notice requesting public comments as of July 2024.

[13]The top three countries for imports were United Kingdom, Canada, and Italy; the top three countries for exports were Japan, United Kingdom, and Israel.

[14]DOD estimates that the defense industrial base consists of over 200,000 companies. These companies enable research and development, as well as design, production, delivery, and maintenance of military weapon systems, components, or parts to meet U.S. military requirements. GAO, Defense Contractor Cybersecurity: Stakeholder Communication and Performance Goals Could Improve Certification Framework, GAO‑22‑104679 (Washington D.C.: December 8, 2021).

[15]For example, the RDP agreement with the Czech Republic states that when an industrial enterprise of the other country submits an offer that would be the low responsive and responsible offer but for the application of any buy-national requirements, both parties agree to waive the buy-national requirement. The Federal Acquisition Regulation describes the “responsiveness of bids” as whether a bid complies in all material respects with the invitation for bids. FAR § 14.301(a). Additionally, a responsible prospective contractor generally must have adequate financial resources, the ability to comply with the required or proposed delivery or performance schedule, have both a satisfactory performance record and a satisfactory integrity and business ethics record, and be otherwise qualified and eligible to receive the award under applicable laws and regulations, among other things. FAR § 9.104-1.

[16]41 U.S.C. § 8302(a).

[17]The specialty metals covered include steel with certain alloy contents, titanium and titanium alloys, and zirconium and zirconium base alloys. 10 U.S.C. § 4863.