OPIOID USE DISORDER GRANTS

Opportunities Exist to Improve Data Collection, Share Information, and Ease Reporting Burden

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106944. For more information, contact Alyssa M. Hundrup at (202) 512-7114 or HundrupA@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106944, a report to congressional committees

Opportunities Exist to Improve Data Collection, Share Information, and Ease Reporting Burden

Why GAO Did This Study

The misuse of opioids has been a long-standing problem in the U.S., representing a serious risk to public health. Opioid-related overdoses accounted for about three-quarters of the estimated 96,801 drug overdose deaths in the 12-month period ending in June 2024. SAMHSA leads federal public health efforts to address the opioid crisis, including administering the Opioid Response grant programs.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for GAO to review the Opioid Response grant programs. In this report, GAO examines the allocation and use of grant funds, the information SAMHSA collects on grant subrecipients, and how SAMHSA has addressed any challenges with the use of the grant funds.

GAO reviewed relevant SAMHSA funding, allocation, and other documents, and interviewed SAMHSA officials. GAO also interviewed and reviewed information from 20 grant recipients (10 states, one territory, and nine Tribes or tribal consortia) selected to reflect variation in grant funding type (state or tribal) and amount changes, overdose deaths, and geography.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that SAMHSA (1) complete and implement a plan for reporting subrecipient information; (2) complete and implement a plan to share data about the use of grant funding; and (3) assess whether and how to reduce administrative challenges faced by Tribes and take appropriate actions. The Department of Health and Human Services concurred with our recommendations.

What GAO Found

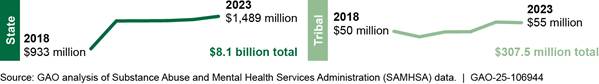

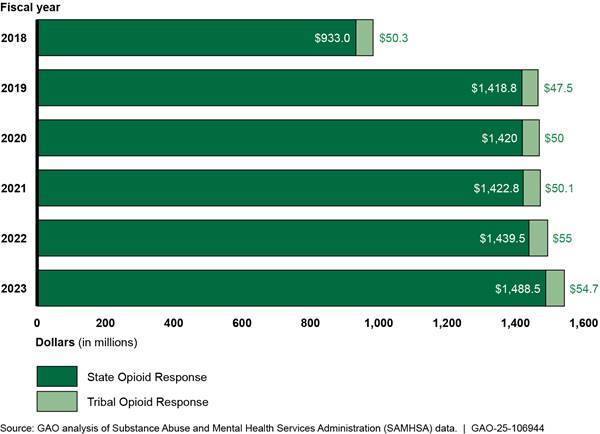

The Opioid Response grant programs—State Opioid Response (SOR) grants and Tribal Opioid Response (TOR) grants—help address the opioid crisis by funding prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery support services. SOR grants are available to states, D.C., and U.S. territories; TOR grants are available to federally recognized Tribes and tribal organizations. Since fiscal year 2018, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has awarded about $8.1 billion in SOR grants and $307.5 million in TOR grants nationwide. SAMHSA allocates funding based on factors such as overdose death rates, and recently revised its allocation to better ensure funding goes to recipients with the greatest need.

Selected SOR recipients reported using grant funding for a variety of services, adapted to support their specific needs. States generally supported treatment for opioid use disorders, and most provided services not covered by other payers, such as transportation. Selected TOR recipients reported using funds primarily to support prevention and harm reduction efforts, such as community education.

SAMHSA collects information on proposed subrecipients, which are organizations recipients anticipate will provide grant-funded services. However, proposed subrecipients are subject to change, and SAMHSA does not collect information about the actual subrecipients once awards are made. SAMHSA officials said that collecting such information could help with efforts to improve the programs. They are determining how to address a new statutory requirement to collect and report information on the “ultimate recipients” of the Opioid Response grants. As of October 2024, the agency had not completed, documented, or implemented a plan for doing so.

SAMHSA has taken steps to address some challenges raised by grant recipients, but other challenges remain. For example, some grant recipients reported challenges obtaining data on services and results of other grant recipients. Obtaining these data would help grant recipients have additional information to use to help improve the services they offer. SAMHSA developed a data sharing strategy but has not determined specific details and time frames. Implementing such a plan would better position SAMHSA to improve how funds are used.

In addition, five tribal recipients reported that grant-related administrative challenges contribute to some Tribes not participating or not making full use of TOR. Two executive orders direct agencies to address administrative burdens for Tribes to the extent practical and permitted by law. However, SAMHSA has not assessed whether there are permissible ways under the orders to help reduce such administrative burdens, which could help to allow additional Tribes to benefit from TOR funding.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

GPRA |

Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

IHS |

Indian Health Service |

|

SAMHSA |

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

|

SOR |

State Opioid Response |

|

TOR |

Tribal Opioid Response |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 17, 2024

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Chair

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Cathy McMorris Rodgers

Chair

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The misuse of opioids harms millions of Americans and contributes to thousands of deaths each year.[1] In 2023, an estimated 5.7 million Americans had an opioid use disorder in the previous year, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).[2] In addition, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show an estimated 96,801 drug overdose deaths occurred in the 12-month period ending in June 2024. Opioid-related deaths accounted for about three-quarters of the drug overdose deaths.[3]

In October 2017, the Acting Secretary of Health and Human Services first declared the opioid crisis to be a public health emergency due to the high rates of opioid use disorder and related deaths, and this emergency remains in effect as of September 2024.[4] SAMHSA, an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), leads the federal government’s public health efforts to address the opioid crisis and reduce overdose deaths. It does this by, among other things, administering grants to states, U.S. territories, Tribes, and tribal organizations.[5] SAMHSA’s Opioid Response grant funding—the State Opioid Response (SOR) and Tribal Opioid Response (TOR) grant programs—has been the agency’s primary source of opioid-related grant funding since the programs’ inception in 2018.[6]

SAMHSA’s Opioid Response grant funding aims to address the opioid crisis by increasing access to evidence-based treatment of opioid use disorder and supporting the continuum of prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery support services for opioid use disorder, stimulant use disorders, and co-occurring substance use disorders.[7] However, in adding the issue of drug misuse to our High Risk List in 2021 and 2023, we determined that federal agencies must implement a strategic national response to drug misuse and make progress toward reducing rates of drug misuse, overdose deaths, and the resulting harmful effects to society.[8]

Since fiscal year 2018, SAMHSA has awarded about $8.1 billion in SOR grants to states, D.C., and U.S. territories; and $307.5 million in TOR grants to Tribes and tribal organizations. Single state agencies—the entity in each state designated to manage substance use disorder services—and tribal offices are the primary recipients of Opioid Response grant awards.[9] These primary grant recipients may administer programs directly or distribute grant funds to subrecipients in the form of subcontracts and other sub-awards. For example, a state agency may make a sub-award to a local public health entity that provides prevention, harm reduction, treatment, or recovery support services, or distributes funds to other service providers.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for GAO to review and assess the Opioid Response grant programs.[10] This report

1. describes how SAMHSA allocates Opioid Response grant funds to grant recipients,

2. examines the information SAMHSA collects about Opioid Response grant subrecipients,

3. describes how selected grant recipients use Opioid Response grant funding, and

4. assesses how SAMHSA has addressed any challenges identified by selected grant recipients.

To determine how SAMHSA allocates Opioid Response grant funds to grant recipients, we obtained and reviewed available documents relevant to SAMHSA’s allocation of funding (such as documents describing the SOR allocation methodology), and interviewed SAMHSA officials. In addition, we reviewed annual award amounts for individual SOR and TOR grant recipients for fiscal years 2018 through 2023, the most recent data at the time of our review. We also reviewed information in the fiscal year 2024 SOR and TOR notices of funding opportunities about the maximum amounts for which prospective grant recipients can apply, which are based on the respective allocation methodologies.

To examine the information SAMHSA collects about Opioid Response grant subrecipients, we reviewed relevant laws, regulations, policies, and documents (such as grant application guidance and template), and interviewed SAMHSA officials. We also interviewed officials from a non-generalizable sample of 10 states and one U.S. territory, selected to obtain variation in funding changes, population, overdose mortality, Medicaid expansion, and geography across the selected states.[11] We also interviewed officials from six Tribes and three tribal consortia (which we collectively refer to as tribal recipients), selected to account for frequency with which they applied for Opioid Response grant funding and their availability.[12] During these interviews, we asked about states’ and tribal recipients’ experiences collecting subrecipient information for the Opioid Response grants and their ability to submit that information to SAMHSA if requested, as applicable.[13]

We also obtained and reviewed grant applications and progress reports for the 11 selected states, and progress reports for the nine selected tribal recipients, as applicable, which describe the activities grant recipients planned to support and conducted using Opioid Response grant funding. For context, we also reviewed information related to subrecipient reporting for SAMHSA’s Substance Use Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services Block Grant, such as the authorizing statute and relevant SAMHSA information, and interviewed SAMHSA officials.[14] We compared what SAMHSA collects and shares about Opioid Response grant subrecipients to a relevant federal law and the block grant program.

To describe how selected grant recipients used Opioid Response grant funding, we interviewed officials from the selected states and tribal recipients, and reviewed grant applications and progress reports for the selected states and progress reports for selected tribal recipients, as applicable. We conducted interviews with national stakeholders, including the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors, the American Society of Addiction Medicine, and the National Indian Health Board, to learn more about the use of Opioid Response grant funds across the country.

To assess how SAMHSA addressed any challenges identified by selected grant recipients, we interviewed officials from the selected states and tribal recipients to learn about any challenges they encountered or were aware of when applying for or using the Opioid Response grant funding, as well as their perspectives on how the grant programs could be improved. We also reviewed selected states’ and tribal recipients’ progress reports, as applicable, for information on reported challenges. We conducted interviews with national stakeholders to obtain information on what challenges, if any, states and tribal recipients experienced when applying for or using Opioid Response grant funding.

We also conducted interviews with SAMHSA officials to learn about any steps the agency had taken or potential plans to address reported challenges, and reviewed documentation provided by SAMHSA. We assessed SAMHSA’s plans for addressing administrative challenges experienced by tribal recipients against two executive orders focused on that topic.[15] We also assessed SAMHSA’s efforts against federal standards for internal control for defining objectives.[16] An underlying principle of these control standards is that management should define objectives in specific terms that include who will achieve it, how it will be achieved, and the time frames for achievement.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

SAMHSA’s Opioid Response Grant Programs

Under SAMHSA’s Opioid Response grant programs, SOR and TOR, the agency may award grants to all 50 states, D.C., U.S. territories, federally recognized Tribes, and tribal organizations.[17] State agencies from each of the 50 states and D.C. have applied for and been awarded SOR funding for each funding opportunity issued by SAMHSA from fiscal years 2018 through 2022.[18] For TOR, the number of Tribes that applied for funding opportunities between 2018 and 2022 and received grant funding ranged from 30 to 134.[19] See figure 1 for the annual SOR and TOR grant award totals for fiscal years 2018 through 2023.

Figure 1: Fiscal Year Award

Totals for SAMHSA’s State and Tribal Opioid Response Grant Programs (dollars in

millions)

Note: These totals exclude awards made under the State

Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis grant program that ended in 2019.

Opioid Response grant recipients use funds primarily to support prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery services to address the opioid crisis. Starting in fiscal year 2020, grant recipients could also use grant funds to provide services to address stimulant misuse and use disorders, including those involving cocaine and methamphetamine. Examples of prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery support services provided using Opioid Response grant program funding include, but are not limited to, the following:

· Prevention services

· Training, such as for health care workers on the safe prescribing and dispensing of pain medication or for the community on the appropriate use of naloxone.

· Youth education to prevent misuse of opioids and stimulants.

· Strategic messaging, such as public service announcements on radio, television, and social media to increase community awareness on the harms of opioid and stimulant misuse.

· Harm reduction services

· Purchasing, distributing, and training for the opioid reversal medication, naloxone.

· Purchasing and distributing test strips used to detect the presence of fentanyl.

· Treatment services

· Assessing clients and referring them to the appropriate services for opioid- and stimulant-use disorders.

· Expansion of access to medications for opioid use disorder by, for example, increasing treatment locations and number of providers.

· Supporting contingency management programs for stimulant use disorder, which involves the use of tangible positive awards, such as gift cards, for not using stimulants.

· Cognitive behavioral therapy to help individuals learn to identify and correct problematic behaviors, help stop substance misuse, and address other co-occurring problems.

· Individual and group counseling services.

· Recovery support services

· Employment support, including job training and placement, and career counseling.

· Peer recovery support services through which peer support specialists combine experience of recovery with formal training and education to assist others in initiating and maintaining recovery.

· Housing, employment, and transportation assistance for people receiving treatment or recovery support services.

· Case management.

The grant award process begins when SAMHSA publicly announces the availability of grant funding through notices of funding opportunity through separate notices for the SOR and TOR grant programs. These notices provide information that prospective applicants (states or Tribes) need to know to apply for the grant. For example, notices describe the program, eligibility requirements, and application requirements.

When applying for Opioid Response grant funds, prospective grant recipients must complete a grant application that includes budget information, and a project narrative that describes how the grant recipient plans to use the funds to conduct approved activities, including pre-established performance goals and measurable objectives. For example, grant recipients are required to estimate the number of individuals to be served with grant-funded services.

After SAMHSA awards Opioid Response grants, the agency is responsible for monitoring the primary Opioid Response grant recipients. According to SAMHSA guidelines, the agency’s grants management staff are to work with and monitor the primary grant recipients on an ongoing basis to ensure they are complying with grant requirements and making progress on their pre-established goals. Specifically, agency staff are to monitor grant recipients through monthly phone calls and other ongoing communications, through reviews of performance and financial information reported by grant recipients, and through site visits when warranted. The primary grant recipients, in turn, are responsible for monitoring subrecipients, such as contractors and treatment providers.

Project Periods and Allocation of SOR and TOR Grant Funding

SAMHSA provides Opioid Response grant funding to primary grant recipients over multi-year project periods with awards made each year. Prior to fiscal year 2024, the project period for both SOR and TOR was 2 years, with an option to apply for an extension of up to 12 months. Starting in fiscal year 2024, SAMHSA increased the SOR and TOR project periods to 3 and 5 years, respectively, with an option for an additional extension of up to 12 months. Annual award amounts for a given project period may differ depending on available funding.[20]

Congressional appropriations determine the amount of Opioid Response grant funding available each year, and SAMHSA is responsible for allocating this funding among grant recipients. To do so, SAMHSA is to develop allocation methodologies that meet statutory requirements, such as requirements to give preference to grantees with relatively greater or demonstrated need in terms of opioid misuse or overdose deaths. Allocation requirements include the following:[21]

· SOR allocations must give preference to states whose populations have a prevalence of opioid misuse and use disorders or drug overdose deaths that is substantially higher relative to the populations of other states.

· SAMHSA must allocate a minimum of $4 million to each state and D.C., and $250,000 to each U.S. territory.

· Up to 15 percent of the money for states must be set aside and awarded to states with the highest age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths based on the ordinal ranking of states according to the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[22]

· SOR allocations must avoid a funding cliff between states with similar overdose death rates to prevent funding reductions when compared to prior year allocations.

· TOR grant funds must not be more than 5 percent of the available funding for Opioid Response grants.[23]

· TOR allocations must give preference to Tribes and tribal organizations serving populations with demonstrated need with respect to opioid misuse and use disorders or drug overdose deaths

Opioid Response Grant Recipient Reporting

SAMHSA collects or has access to several sources of financial and performance information for Opioid Response grant recipients, including the following:

· Performance Progress Reports. Grant recipients are to submit progress reports to SAMHSA mid-year and annually. According to the fiscal year 2024 notices of funding opportunities for SOR and TOR, these reports are to include the following information: (1) updates on key personnel, budget, or project changes (as applicable); (2) progress achieving goals and objectives and implementing evaluation activities; (3) progress implementing required activities, including accomplishments, challenges and barriers, and adjustments made to address these challenges; and (4) problems encountered serving the populations of focus and efforts to overcome them. SOR grant recipients are also to report on progress achieved in addressing the needs of underserved, diverse populations (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities, LGBTQI+, older adults), and implementation of targeted interventions to promote behavioral health equity.

· Client-level data. Grant recipients are to collect client-level data using the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) Client Outcome Measures Tool. These data include client demographics, information about their substance use, and details on services they receive. These data are to be collected for any clients who receive treatment or recovery services that are funded with Opioid Response grant funds. Data are to be collected at intake to SAMHSA-funded services, 6 months post intake, and discharge from the SAMHSA-funded services. According to the fiscal year 2024 SOR and TOR notices of funding opportunities, SAMHSA uses these data to ensure program goals and objectives are being met; to calculate the national outcome measures used to measure program effectiveness across all grant programs; and to show how programs are reducing disparities in behavioral health access, increasing client retention, expanding service use, and improving outcomes.

· Program-level data. Grant recipients are required to complete a program instrument in which they report quarterly data. The data submitted in these instruments include the quantity of naloxone purchased and distributed; the number of overdose reversals that occurred; the number of fentanyl test strips purchased and distributed; and the numbers of people who received prevention education for opioids and stimulants.

· Financial reports. Grant recipients are to submit various reports, including an annual federal financial report that includes cumulative totals, such as the total grant funds received from the federal government and the total amount spent by the grant recipient.

Other Grant Programs

SAMHSA also administers other grant programs that may address aspects of opioid use disorder. Some of these grant programs are focused specifically on opioid use disorders, while other grant programs may be used to address opioid use disorders, as well as other substance use disorders. See appendix I for a list of the 36 opioid-related grant programs that SAMHSA administered in fiscal year 2023.

SAMHSA Revised Allocation of Opioid Response Grant Funding to Better Account for State and Tribe Needs

Revised SOR Allocation Methodology

SAMHSA revised its funding allocation methodology for the fiscal year 2024 SOR grant award project period. Under its revised methodology, SAMHSA allocates funding to states based largely on measures of need, such as measures of drug overdose deaths and the number of people in a state who misused opioids. According to SAMHSA, this approach is similar to how SAMHSA previously allocated funding, with revisions in 2024 aiming to better account for state needs and to limit significant changes in funding from year to year.[24]

The revised SOR allocation methodology consists of a formula to calculate a base funding amount, a formula to calculate a set-aside allocation, and an adjustment parameter.[25] The set-aside funding accounts for 15 percent of total funding, and the base funding accounts for most of the remaining total funding (see fig. 2).

Revised base formula. Similar to the allocation methodology used prior to fiscal year 2024, the revised base formula reflects multiple measures of need. The revised base formula includes two components, according to SAMHSA documentation.

The first component measures an individual state’s needs in two ways. First, it includes a measure of drug overdose deaths, similar to the formula SAMHSA used before fiscal year 2024.[26] Second, it includes an “opioid misuse” measure. This new measure uses data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health to estimate the number of people in a state who reported misuse of opioids during the prior year. SAMHSA determined this new “opioid misuse” measure was more reliable based on available data than the previously used “unmet treatment need” measure.[27]

The base formula’s second component is the SOR Index. SAMHSA intends for this index to correct a bias that previously favored states with larger populations and to better reflect increased need or the impact of opioid misuse within a community. According to SAMHSA documentation, the index uses drug overdose death and opioid misuse rates to help prevent more money going to states simply based on those states having a larger population. In addition, the SOR Index includes a SOR Social Vulnerability Index measure that consists of community factors associated with opioid misuse, such as household characteristics, socioeconomic status, and transportation.[28]

Revised set-aside formula. SAMHSA uses a set-aside formula to allocate 15 percent of total funding among 25 states with the highest drug overdose death rates. The previous allocation methodology, used before fiscal year 2024, also included a set-aside formula, which allocated the set-aside funds among 10 states instead of 25 states. SAMHSA documentation stated it expanded the number of states for fiscal year 2024 to avoid excluding large numbers of states with similar drug overdose death rates. According to SAMHSA officials, the expanded number of states also helps to avoid large drops in funding, or funding cliffs, when states drop off the list of 25 states that receive set-aside funding.

New adjustment parameter. Once SAMHSA calculates the funding allocation for each state using the revised base and set-aside formulas, SAMHSA applies an adjustment parameter—new for fiscal year 2024—that limits funding decreases to no more than 5.52 percent and funding increases to no more than 50 percent from the state’s prior grant award. SAMHSA determined that states could absorb a funding decrease of 5.52 percent with minimal impact on services, based on the level of unspent funding in previous years.

According to SAMHSA officials, they developed the revised SOR allocation methodology—including the revised base and set-aside formulas and new adjustment parameter—through stakeholder meetings with HHS agencies that have similar types of grant programs, to learn about best practices and other considerations. The agency also conducted in-depth analyses of relevant data sources and measures.

SAMHSA officials said the revised SOR allocation methodology was approved by the Secretary of Health and Human Services. In addition, according to SAMHSA officials, SAMHSA notified congressional committees, as required—specifically, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions; the Senate Committee on Appropriations; the House Committee on Energy and Commerce; and the House Committee on Appropriations—on March 8, 2024.[29]

In the future, SAMHSA officials said they plan to assess how the revised SOR allocation methodology affects states’ efforts to use funding to address the opioid crisis and reduce overdose deaths. SAMHSA officials stated that any assessment of this change will take place sometime after the fiscal year 2024 grant project period ends in 2027.

For annual SOR award amounts and year-to-year percentage changes, see appendix II, table 1.

Revised TOR Allocation Methodology

As it did with the SOR grant program, SAMHSA used a revised methodology to allocate TOR grants starting in fiscal year 2024. Under the current methodology, SAMHSA allocates funding based on population size and estimates of need, including drug overdose death rates (see fig. 3).

The revised methodology, like the methodology for previous years, uses Indian Health Service (IHS) user population estimates to allocate base award amounts.[30] For example, a Tribe or tribal organization with an IHS user population of 10,000 or less has a 2024 base award amount of $250,000; a Tribe or tribal organization with a user population of more than 40,000 has a base award amount of $1,750,000. According to SAMHSA officials, the base award amounts under the revised methodology are up to 10.5 percent lower compared to fiscal year 2022 grant program base award amounts. SAMHSA did not reduce base award amounts for tribal recipients with an IHS user population of 10,000 or less.

According to SAMHSA officials, the lower base award amounts allow for a new need-based supplement award. SAMHSA officials said they added the supplement award to address the legal requirement that the agency give preferences to Tribes and tribal organizations serving populations with demonstrated need with respect to opioid misuse and use disorders or drug overdose deaths.[31]

To calculate the supplement award, SAMHSA developed a formula that uses county-level drug overdose death counts and rates to develop a list of counties with the highest overdose mortality burden among American Indian and Alaskan Native populations.[32] SAMHSA officials said that by combining rates and counts, the formula addresses the needs of both smaller and larger Tribes. Tribes and tribal organizations that plan to serve one or more counties on the list are eligible for the supplement award in addition to the base award amount. According to SAMHSA officials, based on the number of fiscal year 2024 TOR awardees and the amount of funds available for the supplement, they anticipated awarding each grant recipient eligible for the supplement an additional 18 percent of their base award amount. For example, a Tribe or tribal organization receiving a 2024 base award amount of $250,000 would receive an additional $45,000.

According to SAMHSA officials, they developed the updated TOR allocation methodology taking into account feedback they received during consultation with Tribes in November 2023.[33] At these meetings, which included 191 participants, such as tribal leaders and other tribal partners, SAMHSA obtained input on how to update the TOR award allocation methodology to comply with statutory requirements. SAMHSA reported that during this consultation, there was some support for retaining the use of IHS user population estimates for purposes of allocating funds; however, other respondents noted that using these data could limit allocations for smaller Tribes that may have greater need.[34]

Among the selected tribal recipients we interviewed, officials from three said they thought the IHS user population was sufficient for calculating award amounts, and officials from one tribal recipient noted concerns about using these data because they may not reflect tribal members who might benefit from Opioid Response-funded activities. An official we interviewed from a national organization representing Tribes expressed concern about the use of IHS user population data to calculate award amounts due to potential inaccuracies in the data.

SAMHSA reported that there is no national data source that shows accurate and complete opioid use and opioid overdose rates for Tribal communities. In the absence of such data, SAMHSA officials continued using the IHS user populations for the base allocation in its TOR allocation methodology, while also using overdose death rates and counts to identify counties eligible for the need-based supplement award. SAMHSA reported that continuing to use the IHS user population data for the base amount would avoid large fluctuations in funding between grant cycles. SAMHSA officials told us that they expect to evaluate the effect of the need-based supplement formula, which relies on data that is more likely to change over time.

After its consultation with Tribes in 2023, SAMHSA officials said they presented the revised TOR allocation methodology to the Tribal Technical Advisory Committee in early 2024.[35] SAMHSA officials also notified Congress and briefed the Secretary of Health and Human Services regarding the revisions. SAMHSA officials said they plan to monitor TOR programmatic and fiscal data for any changes in trends that may be the result of the need-based supplement, such as the extent to which funding remains unspent at the end of the allowed project period, including any extensions.

For information on total TOR award amounts, see appendix II, table 2.

SAMHSA Collects Information on Proposed Subrecipients of Grants, but Not on the Actual Subrecipients

SAMHSA Collects Information from States and Tribes on Proposed Subrecipients of Grants

Since the Opioid Response grant funding began in 2018, SAMHSA has collected information about proposed subrecipients of the funds. Specifically, SAMHSA officials said they have collected information about proposed subrecipients as part of the application process to help them determine if the primary grant recipients’ proposed budgets are consistent with their proposed activities and grant program requirements. On the application, the prospective primary grant recipients are to list the name of each proposed subrecipient, including the funding amount and a description of services to be provided.

These proposals are subject to change. SAMHSA officials told us that primary grant recipients may make changes to proposed subrecipient organizations as they implement their programs, so the actual subrecipients, the amounts of funding they receive, and services they provide may differ from the grant application.[36] One grant recipient we interviewed told us they generally know which subrecipients will be receiving grant funds at the time of their application, but the subrecipient organizations may change over time, or, in some cases, the grant recipient may not have identified a specific subrecipient to propose at the time of the application. Another grant recipient said they do not provide specific names of all proposed subrecipients in their applications. For example, the application may identify the overall amount of funding for public health units without listing the names of proposed health units.

Rather than collecting information about the actual subrecipients or the specific services they provided, SAMHSA requires grant recipients to track funding of activities by subrecipient, and to be prepared to submit this information to SAMHSA upon request, according to SAMHSA officials. The officials told us the agency tries to limit grantee reporting to what is required by statute or is necessary for other purposes to help reduce grant recipients’ burden of collecting and submitting information.

Officials we interviewed from 10 of our 11 selected states and two selected tribal recipients who provide funding to subrecipients told us they collect and track subrecipient information for the Opioid Response grants, and that reporting such information to SAMHSA would not be difficult if it were requested. Officials from one other selected state said they collect this information, but reporting it to SAMHSA would be an administrative burden.

SAMHSA has Not Completed and Implemented a Plan to Collect and Report Actual Subrecipient Information

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, requires Opioid Response grant recipients to report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services “a description…of the ultimate recipients” of the Opioid Response grant funds.[37] In addition, HHS is required to submit a report to Congress with a summary of this and other required information no later than September 30, 2024, and every 2 years thereafter.[38]

However, as of October 2024, SAMHSA officials said they had not started collecting actual subrecipient information from Opioid Response grant recipients. SAMHSA officials told us that they are working to develop an implementation plan, but as of October 2024 had not yet completed or documented the plan.

Specifically, SAMHSA officials told us they are in the process of drafting an approach to collect information on ultimate recipients. Agency officials told us they anticipate that the new reporting requirements would be the same for SOR and TOR, and that SAMHSA would leverage existing Opioid Response grant data collection efforts, as much as possible, to reduce any additional reporting burdens for grant recipients. However, they said collecting information would require additional work on the part of grant recipients and therefore they did not expect to start collecting this information until at least fiscal year 2025.

SAMHSA is also determining how it will fulfill the requirement to report to Congress. For SAMHSA’s 2024 SOR report to Congress, agency officials plan to include information on how they plan to address the requirement. SAMHSA officials said that in the future, starting with the 2026 SOR report, they intend to include the data on SOR subrecipient information biennially in their reports to Congress. As of October 2024, SAMHSA had yet to determine the process for reporting subrecipient information to Congress for TOR.

Completing, documenting, and implementing a plan, and beginning to collect data on actual subrecipients, would provide information on program subrecipients that could be used by SAMHSA to improve the Opioid Response grant programs. It would also provide SAMHSA with the information it plans to report to Congress.

Collecting information on actual subrecipients also would be consistent with the approach SAMHSA uses for other grants. SAMHSA collects information on actual subrecipients for the Substance Use Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services Block Grant (referred hereafter as the block grant). Specifically, block grant recipients—which generally include state agencies that also receive State Opioid Response grants—are to submit annual reports that are to include information about all subrecipients that provided prevention activities, and treatment and recovery support services directly to clients.

SAMHSA officials said they collect this information to comply with legal requirements, including the requirement that grant recipients report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services a description of “the recipients of amounts provided in the grant.”[39] SAMHSA officials said they also collect this information to ensure compliance with other block grant requirements. For example, grant recipients are required to allocate a certain amount of funding for specific purposes. These funding allocations include a 20 percent set-aside for primary prevention and a 5 percent set-aside for early intervention services for individuals with HIV receiving substance use disorder treatment services in designated states.[40]

SAMHSA officials said they could use information about the actual subrecipients to manage and improve the Opioid Response grant programs. The officials said they hope the information will give them a better understanding of what subrecipients do with grant funds, how much money subrecipients are receiving, and what SAMHSA can do to better support states and Tribes. For example, SAMHSA officials said they use the information on actual subrecipients collected from block grant recipients to identify the treatment landscape within a state and any subrecipients that may be of concern. Officials said they could also use such information on Opioid Response grant subrecipients for program improvement, such as to identify any gaps in treatment and gain a better understanding of how services are provided to clients.

Selected States and Tribal Recipients Used Grant Funding for a Variety of Prevention, Harm Reduction, Treatment, and Recovery Services

Through progress reports submitted to SAMHSA and in our interviews, officials from our 11 selected states reported using Opioid Response grant funding to provide the continuum of prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery services. The nine selected tribal recipients described using their Opioid Response funding primarily to support prevention and harm reduction efforts.

Selected States Reported Using Opioid Response Funding for the Continuum of Services, Adapted to Specific State Needs

Selected states we reviewed reported that they generally used Opioid Response grant funding to support the continuum of services for opioid and stimulant-use disorders, which spans prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery services. Most state officials told us the Opioid Response funding is critical to their state’s ability to address the opioid crisis or to fill gaps in care. However, states adapted how they implemented these efforts to support their specific needs. For example, some state officials noted that the flexibility of the Opioid Response funding has allowed them to address substance misuse in a way that matches the needs of their communities, or it has allowed them to provide innovative programming they could not implement with other funding sources. Further, officials in most of the selected states described how the Opioid Response funding was helpful to fill gaps in care in cases when Medicaid and other payers did not cover certain services, such as recovery housing and transportation.

Prevention. All 11 selected states reported conducting a variety of opioid prevention efforts using Opioid Response funding. Such efforts included education or training for health care workers and law enforcement personnel—including education on the use of the overdose reversal drug naloxone—as well as media campaigns and other community education efforts. State officials described using the funds to support the development of education efforts and training courses aimed at pharmacists, emergency room physicians, and other health care providers on the risks of opioids, and how to prevent, identify, and treat opioid overdoses.

Harm reduction. Ten of the 11 selected states reported using Opioid Response funding for harm reduction efforts, primarily for the purchase and distribution of naloxone and fentanyl test strips. They used a variety of different methods to distribute these harm reduction products, including distributing the products through public health departments, pharmacies, emergency rooms, and the mail. One state used vending machines to make it easier for people to access the products.

Treatment. All 11 selected states described using Opioid Response funding to support treatment for opioid or stimulant use disorders; however, their exact approaches varied. Nine states provided both treatment for opioid use disorder (through medications for opioid use disorder) and treatment for stimulant use disorder (through contingency management). One state provided only treatment for opioid use disorder, and one state provided only treatment for stimulant use disorder, but also funded a call-in line that connected people to treatment options for opioid use disorder. Officials from this state reported that they did not use funding for medications for opioid use disorder because they were generally available in their state and covered through Medicaid or other payers. However, officials from a state that had not expanded Medicaid said their state relied on the Opioid Response funding to cover treatment services for the uninsured.

Officials from nine selected states described how they distributed funding to entities—such as opioid treatment facilities, hospitals, outpatient providers, or nonprofit organizations—to provide medications for opioid use disorder or contingency management. Two states described contracting with intermediaries, which then contracted with local entities to provide treatment. Two states described how their state implemented a “hub and spoke” model, using locations throughout the state to serve as a point of entry for people seeking treatment, and treatment sites within the community for individuals to receive ongoing treatment, monitoring, and support. In addition to directly funding treatment, two states described how they used Opioid Response funding to support housing for those in active treatment.

|

Officials from seven of our 11 selected states described using or planning to use Opioid Response funding to support mobile units. Mobile unit activities include distributing buprenorphine, a medication for opioid use disorder, in hard-to-reach communities; bringing recovery support services into communities; and providing certain health care and other support services to individuals with substance use disorders who lacked transportation or access to health care services. However, officials from the other four states noted that purchasing mobile units in their state was not feasible due to an inability to get approval to purchase mobile units, or mobile units not being cost effective due to the need to travel long distances to reach a relatively small number of people. |

Source: GAO analysis of information from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and interviews with state officials; GAO (icon). | GAO-25-106944

|

Services for Incarcerated Populations Nine of the 11 selected states in our review used Opioid Response funding to provide services to individuals who were incarcerated or recently released from a correctional facility. Such services included providing naloxone for reversing overdoses, or training on its use and providing treatment for opioid use disorder for those who had been recently incarcerated. States also described using Opioid Response funding to support reentry programs for people leaving correctional facilities, primarily in the form of peer support and housing assistance. |

Source: GAO analysis of

information from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

and interviews with state officials; GAO (icon). | GAO-25-106944

Recovery services. All selected states reported using Opioid Response funding to support services for people in recovery from opioid use disorder or stimulant use disorders. Nine states reported using grant funds to support recovery housing for individuals in recovery. States also reported providing various peer recovery services, including trained peer support counselors and employment support.

Selected Tribal Recipients Primarily Used Opioid Response Funding for Prevention and Harm Reduction Efforts

All nine of our selected tribal recipients reported using the Opioid Response funding primarily to support prevention and harm reduction efforts, and to a lesser extent, treatment services and recovery efforts. Four of the nine also used some of their Opioid Response funding to support treatment for opioid and stimulant use disorders. Some tribal officials specifically described the Opioid Response funding as being critical for addressing opioid and stimulant misuse in their communities. Some also said the funding’s flexibility allowed them to support culturally appropriate approaches to addressing substance use disorders in their communities. Some officials noted that this flexibility was important because there are not many funding opportunities available to Tribes specifically for opioid and stimulant use disorders.

Officials from selected tribal recipients we interviewed described a range of prevention efforts supported by Opioid Response funding, including efforts to educate community members about opioids and stimulants and health care workers on the use of medications for opioid use disorder. Some tribal officials also described using their Opioid Response funding to purchase and distribute naloxone or fentanyl test strips. Further, five tribal recipients described how they used Opioid Response funding to support recovery efforts, including peer recovery support services and recovery housing for members of the Tribe transitioning out of treatment and back into their communities.

|

Cultural Practices Officials from seven tribal recipients in our review described using Opioid Response funding to support various cultural practices or services with the goal of preventing substance use disorders or assisting tribal members going through recovery. Some of these tribal officials described practices that included community gatherings and traditional healing programs. Some of these tribal officials stated that SAMHSA had been supportive of funding cultural practices using Opioid Response funding. |

Sources: GAO analysis of information from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and interviews with tribal officials; GAO (icon). | GAO-25-106944

SAMHSA Has Made Changes to Help Address Some Opioid Response Grant Challenges, but Does Not Have Plans or Time Frames to Address Others

SAMHSA has Made Changes to Help Address Challenges with Grant Periods, Data Collection, and Allowable Use of Funds

SAMHSA has made changes to the Opioid Response grant programs to help address challenges encountered by grant recipients. These include changes that address some of the challenges reported by our selected grant recipients and national stakeholders we interviewed.[41] The changes by SAMHSA include extending grant periods, revising its data collection tool, and addressing issues related to the allowable use of funds.

Grant Periods

Beginning with the fiscal year 2024 Opioid Response (SOR and TOR) grant programs, SAMHSA extended the grants’ project periods from 2 years to 3 years for SOR, and from 2 years to 5 years for TOR.[42] SAMHSA officials stated that the decision to extend the grant periods was based on feedback they received from states and Tribes about challenges they experienced because of the 2-year award period, such as not having enough time to expend all the funds. SAMHSA officials stated that they extended the SOR project period to 3 years instead of 5 years (as was done for the TOR grant) so they could assess the new method for calculating award amounts and update the underlying data used to calculate the award amounts. In addition, agency officials said they plan to assess the effect of lengthening the SOR and TOR project periods by, for example, reviewing performance measures and the level of unspent funds. However, officials stated that they need to wait to perform such assessments until the fiscal year 2024 grant project periods end in 2027 for SOR and 2029 for TOR.

These changes could help to address challenges experienced by state and tribal officials we interviewed who told us that they faced challenges because of the 2-year project period. Specifically, officials from 10 of the 11 selected states and eight of the nine selected tribal recipients said the original 2-year project period for the Opioid Response grants presented challenges, such as the need to request an additional optional extension of up to 12 months to finish spending the funds. Furthermore, most selected states and some selected tribal recipients described how federal funding delays, state procurement processes, and other delays shortened the time available for program activities, which added to the difficulty of spending funds in the available time. In addition, two national stakeholders we spoke to recommended that SAMHSA increase the project period beyond 2 years to address the difficulties encountered by states and Tribes.

Officials from some selected states and tribal recipients also noted that the 2-year project period made it challenging to staff programs funded by Opioid Response grants. For example, officials from one state said it was hard to recruit staff for jobs that may not be funded in a year. Generally, state and tribal officials, as well as one national organization that represents states, noted that a longer project period would help states and Tribes use these grant funds more effectively by allowing for adequate time to expend the funds.

If grant recipients do not spend funding within the 2-year project period, plus the available extension of up to 12 months, then the funding is to be returned to the U.S. Treasury after the grant is closed, according to SAMHSA officials. Our review of information for fiscal year 2020 SOR grantees found that the grantees spent about 95 percent of the funds by the end of the project period, including extensions. However, 13 states and U.S. territories did not spend anywhere from approximately 11 percent to 83 percent of their awarded grant funds by the end of the allowed project period, including extensions (see app. III).

Data Collection

Selected state and tribal officials also described challenges related to the collection of client-level data using SAMHSA’s GPRA Client Outcome Measures Tool.[43] Ten of the 11 selected states and five tribal recipients in our review described difficulty getting clients who received Opioid Response-funded services to participate in data collection due to the length and, for some, the sensitivity of the questions asked. SAMSHA has also received similar written feedback from other grant recipients.[44] In addition, one national stakeholder we spoke to said having to report the client-level data created a lot of burden for grant recipients.

According to SAMHSA officials, the average 6-month follow-up completion rate for collecting these client-level data was 37.4 percent for states and 31.8 percent for Tribes for the most recent reporting period available.[45] According to SAMHSA officials, the agency collects and considers feedback from states and Tribes on the GPRA tool, and they have revised the tool to help address concerns. For example, in 2022, SAMHSA removed several questions that grant recipients felt were not appropriate. SAMHSA shortened the tool by six questions (removed 48 questions and added 42 questions) and modified or removed questions considered potentially intrusive or culturally offensive. As of October 2024, SAMHSA is in the process of modifying this tool further in an effort to reduce burden.

Officials we interviewed from two selected states also noted that complete client-level data was not collected for clients who received services across project periods, resulting in a portion of data not being counted for a grant recipient’s reporting. This occurs when a client starts receiving services in one project period and then continues to receive services in a different project period. To help address this concern, SAMHSA developed instructions that provide a way for grant recipients to collect and count client-level data across grant project periods.

Allowable Use of Funds

States and tribal officials also described challenges with limitations on the allowable use of funds, which SAMHSA has taken steps to address. Most state and tribal officials we interviewed told us that limitations on the use of Opioid Response grant funding for certain efforts or activities was a challenge. For example, officials from one state and one tribal recipient cited the grant programs’ $3 limit, per person per day, for the purchase of food. Some tribal officials told us that the ability to provide food at community events is a sign of respect and care that helps encourage participation. Officials from two states described how being able to provide food to people seeking treatment encourages participation. In addition, one national stakeholder we spoke to also noted the need for more flexibility in the use of funding to provide food. In the 2024 funding announcements, SAMHSA increased the spending limit for food to $10 per person per day, which SAMHSA officials stated was to adjust for inflation and clarify the ability to use the funds to purchase food as part of the delivery of services. This change was scheduled to go into effect for the project period scheduled to start on September 30, 2024.

In addition, five state and tribal officials, as well as one national stakeholder, said that limits for contingency management efforts made it challenging for use as an effective treatment tool.[46] Specifically, the $75 limit, per person per year, is below the level supported by research, according to most of these state and tribal officials, as well as SAMHSA officials we interviewed. Officials from one state noted that they also were unsure if they could combine Opioid Response funding with other funding to reach an amount that would be more effective. SAMHSA officials told us that contingency management amounts can be supplemented with funding from other sources, and that they are waiting on clarification from HHS regarding increasing the $75 limit. To further address this matter, SAMHSA officials reported that they are working on an implementation guide for contingency management, which will include how to address issues related to financially supporting contingency management programs. The officials expected this guide will be available in late 2024 or early 2025.

SAMHSA Has Not Completed and Implemented a Plan to Share Data with Grant Recipients or the Public

SAMHSA officials told us that researchers, grant recipients, and others have expressed an interest in being able to access client-level data from the Opioid Response grant programs that they collect using SAMHSA’s GPRA Client Outcome Measures Tool. SAMHSA officials stated that grant recipients have expressed a desire to see more information from other recipients, such as client-level data, to better understand how they are doing compared to other grant recipients. Some state and tribal officials we interviewed also stated that having access to client-level data or other information from the SOR grant program would help them better understand how they were performing and whether their efforts could be improved.

To address the challenge of data availability, SAMHSA officials told us they are exploring how to make de-identified client-level data from the Opioid Response grant programs available via public use files, similar to how the agency makes data available for the block grant and their national survey.[47] This would allow grant recipients and others access to collected data, which could then be analyzed to provide insights on the use of opioid response grants. SAMHSA officials stated that they are exploring how to properly de-identify these data to protect client confidentiality when shared. SAMHSA officials also stated that they are working with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to better standardize data so that it can be effectively analyzed.

SAMHSA also developed a data strategy in 2023 that agency officials said is an effort to address the challenges with data sharing across all of SAMHSA’s grant programs, including challenges with data dissemination and access.[48] The strategy outlines actions across multiple goals, including a goal to strengthen access to, utilization of, and dissemination of SAMHSA data. The actions to achieve this goal include, among other things, exploring the development of access to discretionary grant data. The strategy notes that this action will help SAMHSA carry out plans to include discretionary grant data as part of its public or restricted-use files, with the goal of using these data sets to better inform policy and program development.

SAMHSA’s data strategy acknowledges the importance of enhancing access to and dissemination of data from SAMHSA’s grant programs, such as the Opioid Response grant programs. In addition, in our prior work we have found that it is important for organizations or people, such as grant recipients, to have access to evidence, such as programmatic data, to inform management decision-making.[49] Furthermore, we have noted the importance of defining what is to be achieved, who is to achieve it, how it will be achieved, and the time frames for achievement.

However, SAMHSA’s data strategy document does not include specific details on how the agency plans to achieve the goals and actions in the plan, including making data publicly available, nor does the strategy include time frames for doing so.[50] Without documentation of these details, it is not clear when or how such information will be available to grant recipients and others. Making client-level data available will be consistent with SAMHSA’s data strategy and will ultimately provide states, Tribes, and the public with better information about the use of SOR and TOR grant funds and the results being achieved throughout the country, which can be used to improve services offered.

SAMHSA Has Not Assessed Options for Implementing Executive Orders to Reduce Tribal Administrative Burden

Officials from five tribal recipients and two national stakeholders we interviewed stated that the Opioid Response grant’s administrative requirements were a barrier to Tribes’ ability to apply for and manage grant funding. Some tribal officials and national stakeholders stated that some Tribes, especially smaller Tribes, did not have the capacity and staff to go through the grant application process or described how the application process can be burdensome. Officials from three tribal recipients stated that the client-level data collection requirements of the Opioid Response grant present a challenge for Tribes; officials from two tribal recipients noted this difficulty resulted in grant recipients avoiding using the Opioid Response grant funds for activities that required client-level data collection.[51] These challenges are consistent with a Tribal Consultation that SAMHSA held in November 2023, during which Tribes noted difficulty meeting grant program reporting requirements.[52]

Some tribal officials stated that administrative requirements are one reason that some Tribes do not apply for Opioid Response grants or expend all their funds when they receive such a grant. According to SAMHSA data, of the eligible 574 federally recognized Tribes that could apply for Opioid Response funding, 92 Tribes applied for and received the grant funding for the 2020 TOR grant award period. Approximately 21 percent of the combined total award amount remained unspent at the end of the project period.[53]

Two executive orders address the issue of such administrative burdens encountered by Tribes when accessing federal grant programs. Executive Order 13175 directs federal agencies to consider applications by Tribes for waivers of certain requirements for federal programs, with a general view toward increasing opportunities for utilizing flexible policy approaches at the tribal level in cases where the waivers are consistent with the applicable policy objectives.[54] In addition, Executive Order 14112 directs federal agencies to take various actions to increase the accessibility, equity, flexibility, and utility of federal funding and support programs for Tribal Nations.[55] For example, the executive order directs agencies to proactively and systematically identify and address, where possible, any undue burdens that Tribal Nations face in accessing or effectively using federal funding and support programs. The executive order also directs agencies to design application and reporting criteria and processes in ways that reduce administrative burdens.

SAMHSA’s report from its November 2023 Tribal Consultation noted that the agency was undertaking ongoing efforts to reduce administrative burden on Tribes. However, according to SAMSHA officials, the agency has not yet assessed its options for reducing Tribes’ administrative burden under either executive order. Specifically, SAMSHA has not assessed whether certain administrative requirements could be waived under Executive Order 13175. Additionally, although SAMHSA is participating in agency working groups about how to implement Executive Order 14112, those efforts are focused on identifying gaps in Tribes’ access to federal funding rather than identifying ways to reduce administrative burden, according to SAMHSA officials. Without assessing its options to waive or adjust programmatic requirements under these executive orders, SAMHSA does not know if these executive orders could help reduce unnecessary administrative burden. As a result, Tribes may continue to experience administrative burdens when participating in or attempting to participate in the Opioid Response grant program, resulting in Tribes not being able to fully benefit from the availability of these funds.

Conclusions

Through its Opioid Response grant programs, SOR and TOR, SAMHSA is working to help address high rates of opioid use disorders and opioid-related overdose deaths, which have contributed to the public health crisis that has been persistent for many years. With these grants, states and Tribes have provided an array of prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery services. Since the grant programs began in 2018, SAMHSA has also adjusted the programs in response to a legal requirement and to grant recipients’ feedback about challenges they faced, such as by modifying how it allocates funding across recipients.

However, the agency has not completed, documented, or implemented a plan for collecting and reporting to Congress information about the program subrecipients that deliver opioid response services at the local level. Completing a plan for collecting and reporting this subrecipient information would help SAMHSA meet its legal requirement and provide important information that could be used to manage and improve the Opioid Response grant programs.

Additionally, states, Tribes, and others could benefit from access to program data or other information that shows how their Opioid Response efforts compare to other grant recipients. SAMHSA officials are exploring how to provide grant recipients access to data on program results; however, without documenting key details regarding what data to share, how to share it, or a time frame for doing so, it is unclear whether this effort will help states and Tribes obtain information necessary for improving the services they provide. By developing, documenting, and implementing such a plan, SAMHSA can ensure that information is available to help make improvements in how funds are used, ultimately helping those affected by the opioid crisis.

Tribal officials also identified challenges with administrative requirements related to applying for and using grant funds, especially for smaller Tribes. SAMHSA may have options for addressing these challenges, including granting waivers for some program requirements, but the agency has not assessed whether these options apply to the TOR grants. Without assessing its options for reducing the administrative burden in accordance with relevant executive orders, some Tribes that could benefit from the Opioid Response grant funding may not apply for or fully use the funds, missing out on the benefits these funds could bring to their communities.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making three recommendations to SAMHSA:

The Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use should complete and implement a documented plan for collecting and reporting information about Opioid Response grant subrecipients. (Recommendation 1)

The Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use should complete and implement a documented plan to share data or other information about the use of Opioid Response grant funding to allow grant recipients to compare their information with that of other grant recipients. (Recommendation 2)

The Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use should assess options for reducing the administrative burden faced by Tribes when applying for and using Tribal Opioid Response grant funding and make changes, as appropriate, in accordance with relevant executive orders. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix IV, HHS concurred with our three recommendations. HHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

Regarding our first recommendation, HHS provided information about how SAMHSA plans to collect information about Opioid Response grant subrecipients. Specifically, it stated that in October 2024, SAMHSA announced plans to collect expenditure information for each subrecipient through a subrecipient inventory table in its program instrument tool, which is undergoing review with the Office of Management and Budget.

For the second recommendation, HHS provided additional information about SAMHSA’s 2023-2026 Data Strategy. As described in our report, this strategy is an effort to address challenges with data sharing across all of SAMHSA’s grant programs, including enhancing access to and dissemination of data from the Opioid Response grants. HHS’s comments describe this strategy as a comprehensive roadmap for implementation and list several goals and actions to improve information sharing. However, as we state in our report, the strategy does not include specific details on how the agency plans to achieve these goals and actions, or time frames for doing so. The strategy also acknowledges the need to further explore how data could be shared and the need for additional planning. In response to the recommendation, HHS stated that SAMHSA will explore additional avenues for grantees, the public, and researchers to access grantee data on the use of Opioid Response grant funding.

For the third recommendation, HHS stated that SAMHSA is assessing options for reducing Tribes’ administrative burden using the most recent executive orders and Office of Management and Budget guidance.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7114 or HundrupA@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs can be found on the last page of this report. Major contributors to this report are listed in appendix V.

Alyssa M. Hundrup

Director, Health Care

According to Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) officials, the agency administered 36 opioid-related grant programs in fiscal year 2023. In some cases, these programs required clients supported by funding to have an opioid use disorder, but funds could also be used to provide care for co-existing substance-use disorders and related issues. In other cases, programs did not require clients supported by the funding to have an opioid use disorder, but funds could be used to address opioid use disorder. Below are the names of each grant program and a brief description of their purpose.

· Addiction Technology Transfer Centers. Support national and regional training activities for behavioral health practitioners to improve the quality of behavioral health service delivery, and providing a limited amount of intensive technical assistance to provider organizations to improve their processes and practices in the delivery of effective substance use disorder treatment and recovery services.

· Adult Reentry Program. Expand substance use disorder treatment and related recovery and reentry services to adults in the criminal justice system who are returning to their families and community following a period of incarceration.

· Building Communities of Recovery. Mobilize and connect community-based resources to increase the prevalence and quality of long-term recovery support for people with substance use disorders and co-occurring substance use and mental disorders.

· Comprehensive Opioid Recovery Centers. Establish or operate comprehensive treatment and recovery centers that provide outreach, treatment, harm reduction, and recovery support services to address the opioid epidemic and ensure access to all three Federal Drug Administration-approved opioid use disorder treatment medications.

· Emergency Department Alternatives to Opioids. Support development and implementation of alternatives to opioids for pain management in hospitals and emergency department settings, and reduce the likelihood of future opioid misuse.

· Enhancement and Expansion of Treatment and Recovery Services for Adolescents, Transitional Aged Youth, and their Families. Enhance and expand comprehensive treatment, early intervention, and recovery support services for adolescents and transitional aged youth with substance use disorders or co-occurring substance use and mental disorders, and their families or primary caregivers.

· First Responders – Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act. Support first responders and members of other key community sectors to administer drug or device approved for emergency reversal of known or suspected opioid overdose.

· Grants for the Benefit of Homeless Individuals. Provide comprehensive, coordinated, and evidence-based treatment and services for people, including youth, and families with substance use disorders or co-occurring mental health conditions and substance use disorders who are experiencing homelessness.

· Grants to Expand Substance Use Disorder Treatment Capacity in Adult and Family Treatment Drug Courts. Expand substance use disorder treatment and recovery support services in existing drug courts.

· Grants to Prevent Prescription Drug/Opioid Overdose-Related Deaths. Reduce the number of prescription drug and opioid overdose-related deaths and adverse events among people 18 years and older by training first responders and other key community sectors on prevention and implementing secondary prevention strategies, including the purchase and distribution of naloxone to first responders.

· Harm Reduction. Support community-based overdose prevention programs, syringe services programs, and other harm reduction services.

· Improving Access to Overdose Treatment. Expand access to naloxone and other approved overdose reversal medications for emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose.

· Medications for Opioid Use Disorder – Prescription Drug and Opioid Addiction. Provide resources directly to community-based organizations to help expand and enhance access to medications for opioid use disorder.

· Minority AIDS Initiative: Substance Use Disorder Treatment for Racial/Ethnic Minority Populations at High Risk for HIV/AIDS. Increase engagement in care for racial and ethnic medically underserved people with substance use disorders or co-occurring substance use disorders and mental health conditions who are at risk for or living with HIV.

· Minority AIDS Initiative: The Substance Use and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention Navigator Program for Racial/Ethnic Minorities. Provide substance use and HIV prevention services to racial and ethnic minority populations at high risk for substance use disorders and HIV infection.

· Preventing Youth Overdose: Treatment, Recovery, Education, Awareness, and Training. Improve local awareness among youth of risks associated with fentanyl; increase access to medications for opioid use disorder for youth screened for and diagnosed with opioid use disorder; and train health care providers, families, and school personnel on best practices for supporting youth at risk for or with opioid use disorder.

· Provider’s Clinical Support System – Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder. Provide training, guidance, and mentoring for health care professionals on the use of medications for alcohol use disorder.

· Provider’s Clinical Support System – Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Provide training, guidance, mentoring, and other support services on the use of medications for opioid use disorder for currently practicing health care and counseling professionals.

· Provider’s Clinical Support System – Universities. Fund health care professional schools to increase the number of students learning about substance use disorder and to increase the number of professionals able to treat substance use disorder.

· Recovery Community Services Program. Directly provide peer recovery support services to people with substance use disorders or co-occurring substance use and mental disorders, including those in recovery from these disorders.

· Recovery Community Services Program – Statewide Network. Strengthen community-based recovery organizations, their statewide networks of recovery stakeholders, and specialty and general health care systems as key partners in the delivery of state and local recovery support services through collaboration, systems improvement, public health messaging, and training conducted for or with key recovery groups.

· Rural Emergency Medical Services Training Grant. Recruit and train emergency medical services personnel in rural areas with a particular focus on addressing mental and substance use disorders.

· Rural Opioid Technical Assistance Regional Centers. Implement regional centers of excellence to develop and disseminate training and technical assistance addressing opioid and stimulant use disorders affecting rural communities.

· Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment. Implement screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment services for children, adolescents, or adults in primary care and community health settings to prevent and reduce the use of substances, and expand and enhance the continuum of care for substance use disorder services.

· Services Program for Residential Treatment for Pregnant and Postpartum Women. Provide comprehensive services for pregnant and postpartum women with substance use disorders and their dependent children across the continuum of residential settings that support and sustain recovery.