CAREGIVING

HHS Should Clarify When Youth May Qualify for Support Services

Report to Congressional Addressees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106947. For more information, contact Kathryn A. Larin at LarinK@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106947, a report to congressional addressees

HHS Should Clarify When Youth May Qualify for Support Services

Why GAO Did This Study

Family caregivers provide informal, often unpaid, care to family members in their homes and communities. Research estimates that 3 to 5 million minors may be caregivers. Yet little is known about these children, referred to as caregiving youth, who care for family members with functional limitations, a health condition, or a disability. GAO was asked to examine issues related to caregiving youth.

This report addresses (1) information on caregiving youth in the U.S.; (2) how federal caregiver support programs address caregiving youth needs; and (3) how England, a recognized leader in supporting caregiving youth, supports those youth through policy and programs.

GAO reviewed relevant federal laws, federal regulations, and documents. GAO surveyed a non-generalizable sample of former caregiving youth ages 18 to 25 and obtained useable responses from 43 respondents. GAO analyzed or reviewed the results of school-based surveys of caregiving youth in three states where data were collected—Rhode Island, Colorado, and Florida. GAO reviewed scholarly, peer-reviewed literature on caregiving youth. GAO interviewed officials from HHS, VA, and the Department of Education; stakeholders in England; and representatives from 16 organizations selected for their work on caregiving topics or certain health conditions.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that HHS clarify information on its website related to program eligibility. HHS concurred with our recommendation.

What GAO Found

National data on individuals who care for family members can provide insights into the population of caregivers, but the surveys GAO identified do not allow for accurate estimates of minors who provide informal, often unpaid care to family members (caregiving youth). However, three state-level surveys GAO identified that collected data on caregiving youth showed that middle school students and racial and ethnic minorities played a larger role providing care for a family member compared to other students. According to selected studies, a GAO survey of 43 former caregiving youth and interviews with five of those youth, caregiving youth experience some positive effects from caregiving, but also face several challenges. For example, some respondents to a GAO survey reported experiencing stress and anxiety because of concerns about their family member’s health condition.

Key federal programs that support family caregivers focus on adults and not on caregiving youth. Under the three federal caregiver support programs administered by the Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Veterans Affairs (VA), officials told GAO that family caregivers must be adults to receive supports such as counseling, referrals, and respite care. However, according to a 2024 federal register notice issued by HHS, states and service providers may determine when family caregivers younger than age 18 could be eligible to receive supports under at least one federal caregiver support program. States and service providers may be unaware of any flexibilities because the HHS website does not include this information. One of HHS’s objectives in its 2022–2026 Strategic Plan is to support high-quality services for older adults and people with disabilities, and their caregivers. The plan states that to achieve this objective, HHS leverages resources to better address the needs of all caregivers across the age spectrum. Without complete information from HHS on eligible caregivers, states and service providers may not be aware that they have flexibility to provide services to certain family caregivers under 18.

England established a national policy in 2014 that calls for local governments to take reasonable steps to identify and assess the needs of caregiving youth in their area, according to stakeholders GAO interviewed. Local governments implement this policy by coordinating with municipal agencies, charities, and schools. Some English schools, for example, provide lunchtime groups for caregiving youth and use school bulletins to raise awareness about the population.

Abbreviations

ATUS American Time Use Survey

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

RAISE Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage Family Caregivers Act

VA Department of Veterans Affairs

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 14, 2025

Congressional Addressees

Family caregivers provide informal, often unpaid, care to help relatives in their homes and communities. Research estimates that 3 to 5 million minors may be serving as caregivers for a family member.[1] However, little is known about these children, referred to as caregiving youth, who care for family members with functional limitations due to aging, a health condition, or a disability.[2]

Caregiving youth provide a range of assistance based on a family member’s age, needs, and functionality, including walking, bathing, feeding, transportation, administering medication, and emotional support. Anecdotal evidence suggests that balancing these tasks can leave caregiving youth with long-term mental, physical, and emotional health challenges and possibly affect their overall academic achievement and future earnings.

You asked us to examine issues related to caregiving youth in the U.S. and the federal role in addressing their needs. You also expressed an interest in other countries’ efforts to support caregiving youth. Additionally, House Report 117–403 includes a provision for GAO to study caregiving youth. This report examines (1) information on caregiving youth in the U.S.; (2) how federal caregiver support programs address the needs of caregiving youth; and (3) how England, a recognized leader in supporting caregiving youth, supports those youth through policy and programs.[3]

To understand what is known about caregiving youth in the U.S., we conducted a literature search to identify scholarly, peer-reviewed research, published since 2013, that identified the prevalence, characteristics, and experiences of caregiving youth in the U.S. We identified four peer-reviewed studies that met our criteria for inclusion.[4] In addition, we reviewed national surveys capturing information on caregiving to determine whether they have information on the prevalence and characteristics of caregiving youth and former caregiving youth populations in the U.S. We identified three surveys that met the following criteria: (1) surveyed a national population; (2) collected data since 2013; and (3) included relevant elements for capturing caregiving, such as variables that categorized respondents as caregivers. We also identified three states that conducted school-based surveys that captured information about caregiving youth—Colorado, Florida, and Rhode Island. We reviewed the results of surveys conducted in Colorado (2023) and Florida (2024) and analyzed 2023 data from “SurveyWorks,” a school-based survey of middle and high school students administered by the Rhode Island Department of Education.[5]

Finally, we surveyed a non-generalizable sample of former caregiving youth (ages 18 to 25) between March and April 2024 about their experiences providing care as a youth. We received a total of 87 survey responses, 43 of which were considered eligible for analysis based on the current age of the respondent, the age of the respondent when they provided care, and the completion of all the survey questions. In reporting survey results, we used the following qualifiers to characterize responses from respondents: nearly all (40–43); many (26–39); some (10–25); and few (1–9). In addition, we interviewed five survey respondents to obtain additional details about their caregiving experiences. Findings from our survey and interviews with respondents were gathered for illustrative purposes only and are not generalizable to all caregiving youth in the U.S.

To examine how federal caregiving support programs address the needs of caregiving youth, we reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations, and related documents. We also interviewed officials from several agencies within the Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS), Veterans Affairs (VA), and Education.[6] We assessed HHS’s efforts to support family caregivers against the agency’s goals and objectives as stated in its Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years 2022 through 2026.[7] We also assessed HHS’s efforts to externally communicate quality information to achieve its objectives against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[8]

To supplement information gathered for these objectives, we interviewed researchers who have studied caregiving youth and officials from 16 nongovernmental stakeholder organizations selected for their work on caregiving, caregiving youth, or certain health conditions, such as the American Association of Caregiving Youth, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the American Cancer Society.

To describe how England supports caregiving youth through policy and programs, we conducted a site visit to England to attend the International Young Carers Conference in April 2024.[9] Following the conference, we interviewed researchers, policy advocates, and practitioners from England to learn about their efforts to address the needs of caregiving youth. In addition, we interviewed officials from national nonprofit organizations, England’s Departments for Education and of Health and Social Care, and local government leaders who provide caregiving youth access to services. See appendix I for more detailed information about our methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Caregiving youth—like all family caregivers—provide various types of assistance to family members with functional limitations due to aging, a health condition, or a disability. The types of assistance youth may provide depend on the specific needs of their family member(s). See figure 1 for examples of assistance youth may provide while caring for family members.

Key federal programs provide information and assistance to family caregivers. HHS’s National Family Caregiver Support Program provides formula grants to states, the District of Columbia, and territories to fund services that help family and older relative caregivers.[10] VA’s Caregiver Support Program, administered by the VHA and comprised of two separate programs, promotes the health and well-being of family caregivers who care for the nation’s veterans, through education, resources, support, and services.[11]

HHS, in consultation with the leadership of other relevant federal agencies, is required to oversee the development of a national strategy to recognize and support family caregivers.[12] To carry out this effort, HHS convened the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage (RAISE) Act Family Caregiving Advisory Council in 2019 to explore and document the challenges family caregivers face. In addition, HHS led an advisory council on supporting kin and grandparents raising grandchildren, which it also convened as part of its efforts to establish the national strategy and ensure the strategy was broadly inclusive of all caregiving populations. Each advisory council was charged with providing actionable recommendations for supporting their corresponding caregiving populations through the national strategy.

Little Is Known About Caregiving Youth Nationwide,

but Selected Data Provide Some Insights into the Population

National Surveys Do Not Fully Capture Information on Caregiving Youth, but Some State Data Provide Insight into Their Numbers and Characteristics

Three national surveys collect some data on individuals providing care for family members, including the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, and the National Study of Caregiving.[13] None of these national surveys, however, are designed to provide information on the number of caregiving youth nationwide, and therefore, they may underestimate the population. For example, two of these surveys capture a limited share of youth (i.e., aged 15 to 17) or only include caregivers of Medicare recipients. Even so, these national surveys can shed some light on the population of caregiving youth. For instance, one recent study that relied on ATUS data estimated that between 364,000 to 2.81 million youth were providing care for an adult.[14] For additional information about all three national surveys, including their limitations in capturing information on caregiving youth, see appendix II.

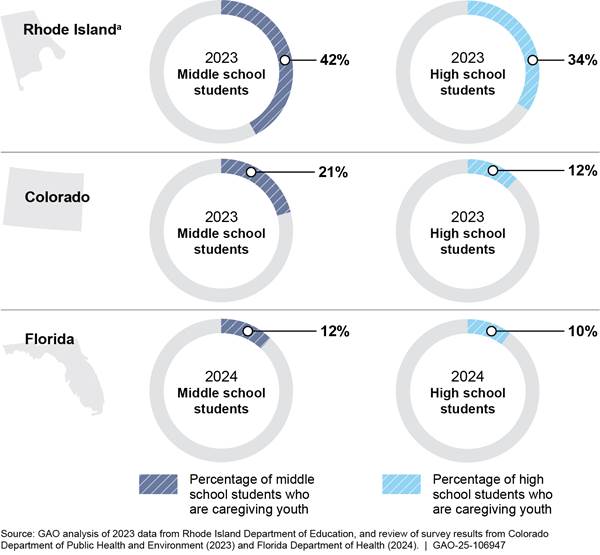

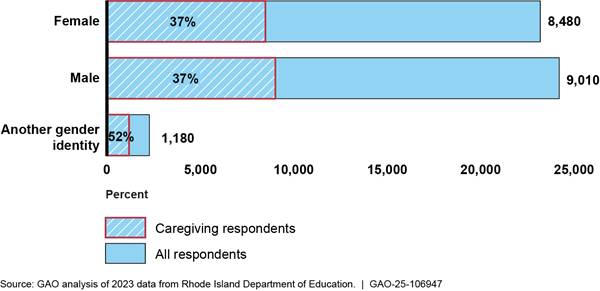

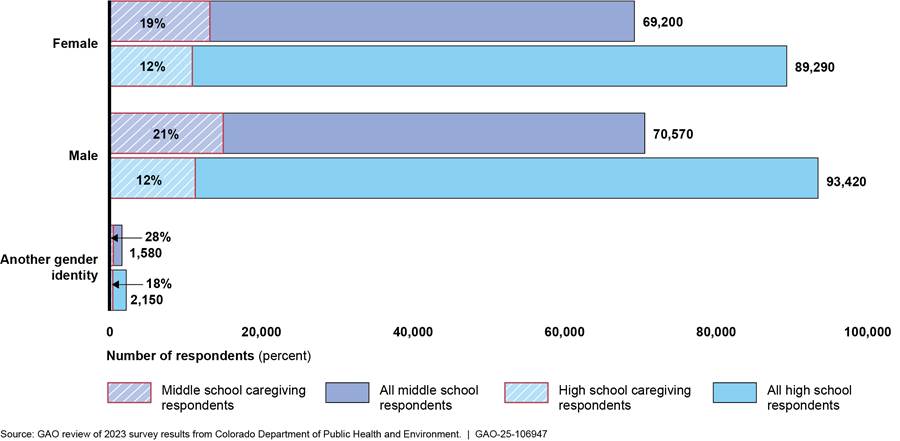

In the absence of national prevalence data on caregiving youth, we found three states that have collected data on caregiving youth. These data provide some insight into aspects of the prevalence and characteristics of caregiving youth in these states. Specifically, Rhode Island, Colorado, and Florida have conducted school-based surveys of middle and high school students to collect information on the prevalence of caregiving or the amount of time youth spent caring for family members.[15] Our analysis of data from Rhode Island and reviews of survey results from Colorado and Florida provide information on the age, race and ethnicity, and gender of caregiving youth in these states, as well as the amount of time they spent providing care for family members.[16]

Overall, we found that across the three states, a greater proportion of middle school students were providing care for a family member compared to high school students in the year the surveys were administered (see fig. 2).[17]

Figure 2: Prevalence of Caregiving Among Surveyed Middle and High School Students, by Selected States from Year of Most Recent Available Data

aThe Rhode Island survey used a broader definition of caregiving youth to include youth babysitting for siblings, compared to Colorado and Florida. The use of a broader definition may contribute to the higher percentages of surveyed middle and high school students in Rhode Island providing care for a family member compared to the percentages of surveyed students providing care in Colorado and Florida.

Generally, across the three states, non-White students played a larger caregiving role than White students. For example, most caregiving youth in Rhode Island (67 percent) were non-White students. There were also greater proportions of caregiving youth among non-White middle and high school students surveyed in Rhode Island and Colorado, although this was not the case for students in Florida.[18] In addition, non-White students spent more time caregiving relative to White students in Florida.

Generally, male and female students were caregivers to a similar extent across all three states. For example, caregiving youth were nearly evenly split between male and female students in Rhode Island. In addition, the proportions of male and female students that were caregiving youth were similar in each of the three states. However, male students spent more time caregiving relative to female students in Florida. For more detailed information about the characteristics of caregiving youth from these state surveys, see appendix III.

Caregiving Youth Reported Experiencing Some Positive Effects, but Also Several Challenges and a Need for Supports

Youth experienced some positive effects from providing care for family members but also reported several challenges and a need for supports, according to our analysis of state survey data, peer-reviewed studies, our non-generalizable survey data, and information from our interviews with former caregiving youth and stakeholder organizations. See figure 3 for examples of the effects caregiving youth reported experiencing and supports they reported needing.

Figure 3: Examples of Effects Caregiving Youth Reported Experiencing and Supports They Reported Needing

Some former caregiving youth we surveyed reported that providing care positively contributed to their development. For example, these survey respondents reported that caring for a family member taught them empathy, patience, and resilience, as well as responsibility, time management, and problem-solving skills. Former caregiving youth also reported that providing care strengthened their family relationships or influenced their career path. For example, one respondent reported that their caregiving experience led to an interest in becoming an advocate for people who were in a similar situation. Likewise, another respondent told us that their role as a caregiver exposed them to social work as a career.

|

Selected quotes on positive effects of providing care for a family member. “[Providing care] helped me develop skills such as resourcefulness, problem solving, resilience, and more. It also helped me develop a strong will and sense of empathy for others.” “I have a close relationship with my brother. I can understand him and his emotions….I realize we still have deep understanding even though he can’t communicate in ‘normal’ ways, and I can have a conversation with him without words.” “There are things that I see need to be done that I never would have noticed without caring. It changed my career path from theater to social work. I wouldn’t have found that career path without caring for my grandma.” Source: Former caregiving youth respondents to a GAO survey. | GAO-25-106947 |

At the same time, former caregiving youth said they experienced challenges with their mental and physical health, peer relationships, and education while providing care for a family member. They also identified needed supports—from counseling to school accommodations—that they either accessed while providing care or believed could have assisted them with those challenges.

Health

Mental health. Caregiving youth were more likely to face emotional challenges (e.g., emotional distress and suicidal ideation) compared to their non-caregiving peers, according to the Florida survey results. In addition, Rhode Island survey results showed caregiving youth were more likely to experience ongoing sadness compared to their non-caregiving peers.[19] See app. III for additional information from our analysis and review of three state surveys.

Findings from our survey also suggest caregiving youth experience some negative emotional effects. Among former caregiving youth whom we surveyed, many respondents reported challenges with stress and anxiety and mental health.[20] For example, respondents reported that they were stressed or anxious because of their family member’s health condition or the challenges of providing care. During our interviews with five survey respondents, all cited having experiences with anxiety when providing care for their family member or delaying attention to their own health issues.

Physical health. According to the Florida survey results, older caregiving youth consumed an unbalanced or unhealthy diet.[21] In addition, three of the five respondents to our survey who we interviewed identified some effects of providing care on their physical health. For example, respondents spoke of delaying attention to their own physical health, experiencing headaches and weakness due to stress, and sustaining physical injuries resulting from struggles with their family member’s behavior.

|

Selected quotes on effects of providing care on health. “I would say that my anxiety started to grow in middle and high school. It happened when I started to understand the responsibility of caring for my sister [who has a disability]. When we were in public, there were times where she would act out and that would trigger my anxiety.” “I had to put some health issues I had on hold for a while. I was in a car accident when I was 11, and I am still dealing with the effects of that. I couldn’t do anything for that because of my mom’s illness. I had an x-ray a month ago to figure out a leg injury from that accident because caring for my mom delayed those appointments.” Source: Former caregiving youth respondents to a GAO survey. | GAO-25-106947 |

Peer relationships

Bullying. State survey data showed a relationship between providing care and bullying or physical conflict. For instance, our analysis of the Rhode Island survey data found that caregiving youth were more likely to be bullied at school within the past year and reported a greater likelihood of being bullied online.[22]

Difficulty maintaining friendships. Some former caregiving youth who responded to our survey reported that their relationships with friends or peers were strained by their caregiving responsibilities, with some saying it impacted them to some or a great extent. Three of the five former caregiving youth we interviewed told us they had difficulty maintaining friendships or felt isolated from peers.

|

Selected quotes on effects of providing care on relationships. “My friendships dwindled during that time because I wasn’t hanging out with anyone, so I don’t have any friendships that have lasted from that time. I felt isolated from all the other kids.” “My relationships with friends were most affected because it was hard for people to be comfortable around my brothers when they hadn’t grown up around [people] with disabilities. It’s difficult for people to understand.” Source: Former caregiving youth respondents to a GAO survey. | GAO-25-106947 |

Education

Grades and academic preparedness. According to the Florida survey results, caregiving youth reported having lower grades. Further, caregiving youth were less often prepared for class, according to our analysis of the Rhode Island survey data.

Three of the five respondents we interviewed cited difficulty completing school assignments on time, poor grades, or arriving late to class because of their caregiving responsibilities. One respondent told us that being late to class several times led to detention. In addition, officials we interviewed from five stakeholder organizations also said that caregiving youth struggle with balancing school and caregiving responsibilities and may experience school performance problems as a result.

School engagement and belonging. According to the Rhode Island survey results, girls who were providing care reported lower levels of school engagement (e.g., enjoyment and motivation toward school) compared to girls who were not involved in caregiving. These results also identified effects of providing care associated with lower levels of belonging (e.g., feelings that they are connected and respected). For example, girls who were providing care reported lower levels of belonging in school compared to girls who were not caregivers. In addition, our analysis of the Rhode Island survey data found that for caregiving youth, stress interfered with participation in school activities to a greater extent compared to non-caregiving youth. The survey data also indicated that caregiving youth were less likely to have a teacher or other adult at school to discuss a problem.

Many respondents in our survey also reported education-related challenges, such as a lack of recognition, understanding, or support from schools or teachers. In addition, some respondents reported difficulties with school engagement. For example, one respondent we interviewed said they chose not to join a sport or club after school because they felt guilty about activities that did not involve caring for their family member.

Postsecondary education choices. According to our analysis of the Rhode Island survey data, caregiving youth were less likely to think about attending a 2-year or 4-year college, or trade school. Two of the five respondents we interviewed said they chose a college closer to home because of their caregiving role. As one respondent explained, they picked a community college close to home to continue providing care for their sister who had a disability.

Supports Needed

Former caregiving youth identified a range of supports needed to help address some of these challenges. For instance, supports such as one-on-one or peer counseling are needed to address the mental health effects of providing care, according to the findings from one study and interviews with three of the five former caregiving youth and seven stakeholder organizations. In one small sample study, mental health support was among the most common types of support cited by 14- to 18-year olds as important in preparing them for caregiving.[23] In addition, former caregiving youth we interviewed reported that individual or peer counseling could have helped them while providing care. Some survey respondents reported accessing a counselor, social worker, or mental health professional while providing care. Others reported that these supports were needed. One former caregiving youth we interviewed told us that peer support would have been helpful while providing care for their grandparent with a health condition, stating: “I would go to the hospital and see these support groups for caregivers advertised, but they were always for adults and held during school hours.”

Training on caregiving responsibilities and respite care could also help support caregiving youth according to one study, our survey, and interviews with former caregiving youth. For instance, in the small sample study mentioned above, youth ages 14 to 18 with caregiving experience were more likely than those ages 19 to 24 to identify skills training from professionals or other informational resources about caregiving as important.[24] Former caregiving youth we surveyed also reported a need for training on caregiving or medical skills, such as medication management and personal care skills. In addition, a few reported that respite care or funding to hire additional help to care for a family member was a needed support.

Finally, former caregiving youth we surveyed reported that school accommodations would have helped with some of the effects from providing care. Four of the five respondents we interviewed said that flexible deadlines for school assignments or tailoring school accommodations to meet their specific needs would have been helpful. One respondent caring for a grandparent said, “I would have loved to get my homework in on time—nothing would have made me happier—but I couldn’t dedicate all my time to my education because I had more on my plate like caregiving.” Another respondent explained that while their school gave them testing and assignment accommodations because of their role providing care for a parent with a health condition, it was not as helpful as it could have been, stating, “I think it would have been better if it [the school accommodation] was a little more [centered around my specific needs]….The support became one more thing to manage (. . .) because it happened to me and not with me. I didn’t have a school counselor to work with me on this.”

HHS’s Website Does Not Include Information About When Youth May Receive Caregiver Support Services, and National Strategy Actions Focus Primarily on Adults

HHS’s Website Omits Information About State Flexibilities That May Allow Certain Individuals Under Age 18 to Receive Support Services

Federal programs support the important role family caregivers play in the nation by providing services to assist them. However, regulation and policy implementing these federal programs generally focus on services for adults rather than youth. For example, HHS’s National Family Caregiver Support Program provides services to adults or other individuals who are informal caregivers to older individuals, or individuals with certain chronic diseases or disorders, and older relative caregivers caring for children, or individuals with disabilities.[25] And VA’s Caregiver Support Program restricts eligibility to those aged 18 and over who are either a family member who provides care for, or a non-family member who will live full time with, a veteran.[26] These programs provide a range of services including support groups and training for caregivers (see table 1).

|

HHS’s National Family Caregiver Support Program |

|

|

Selected eligibility requirements |

Examples of supports |

|

Support services shall be provided to family caregivers and older relative caregivers. A “family caregiver” is an adult family member, or another individual, who is an informal provider of in-home and community care to an older individual or to an individual with Alzheimer’s disease or a related disorder with neurological and organic brain dysfunction. An “older relative caregiver” is a caregiver who is age 55 or older and who lives with, is the informal provider of in-home and community care to, and is the primary caregiver for a child or an individual with a disability. |

Provides (1) information to caregivers about available services; (2) assistance to caregivers in gaining access to the services (3) individual counseling, organization of support groups, and caregiver training; (4) respite care; and (5) supplemental services, on a limited basis. |

|

VA’s Veterans Health Administration Program of General Caregiver Support Services |

|

|

Selected eligibility requirements |

Examples of supports |

|

A general caregiver is a person, 18 years of age or older, who is not a primary or secondary family caregiver and provides personal care services to a veteran enrolled in the VA healthcare system, even if the individual does not reside with the veteran. |

Provides peer support mentoring, skills training, coaching, telephone support, online programs, and referrals to available resources. |

|

VA’s Veterans Health Administration Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers |

|

|

Selected eligibility requirements |

Examples of supports |

|

A family caregiver must (1) be at least 18 years of age; (2) be either the eligible veteran’s spouse, son, daughter, parent, stepfamily member, or extended family member; or someone who lives with the eligible veteran full-time or will do so if designated as a family caregiver. |

Offers enhanced clinical support and services for caregivers of eligible veterans who have a serious injury (including serious illness) and require in-person personal care services among other requirements. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) information about these programs. | GAO‑25‑106947

Although federal statute and regulation primarily provide for services under the National Family Caregiver Support Program to adult family members who are informal providers of care, caregivers younger than age 18 may also be eligible to receive services in certain circumstances. For example, in its February 2024 Federal Register notice implementing program regulations, HHS reported receiving one public comment suggesting individuals of working age who are not adults be included in the definition of family caregivers.[27] In its response to this comment, HHS noted that states and service providers may choose how to define an “adult” for the purposes of determining a family caregiver or may consider individuals of working age who are not adults as “other individuals,” as long as they comply with other federal and state requirements.[28] HHS officials told us that there may be instances under which a caregiver of working age but younger than 18 is defined as an adult under state law.

HHS’s website describes the population of caregivers eligible to receive services as those adult family members or “other informal caregivers ages 18 and older.” Its website does not specify that states and service providers may choose how to define an adult for the purposes of determining program eligibility. As such, states and service providers may not be aware of their ability to determine who is eligible to receive family caregiver support services. According to HHS officials, the regulations did not specify age requirements for family caregivers because the agency allows states and service providers to define an adult in this context. In response to our review, these officials stated that they will update the description of eligible program participants on its website to avoid potential confusion. However, the officials did not provide a timeframe for when the website would be updated with clarifying information.

One of HHS’s objectives in its 2022-2026 Strategic Plan is to support high-quality services and resources for older adults and people with disabilities, and their caregivers, to support increased independence and quality of life.[29] Among the strategies in HHS’s strategic plan that the agency indicates it will use to achieve this objective is supporting activities to better understand and address the needs of all caregivers across the age and disability spectrum. HHS also states that the agency will leverage technical assistance and resources to address the needs of older adult, kinship families, non-kinship, and minor caregivers at all levels. Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should externally communicate the necessary quality information so that external parties can help the entity achieve its objectives and address related risks.[30] Without clarifying its website language regarding the ages of all eligible caregivers, HHS may not be able to effectively meet its strategic objective, and states and service providers may not be aware of their ability to define who is eligible to receive family caregiver support services and respond to the needs of all eligible family caregivers.

|

Federal Programs for Certain At-Risk Youth Populations are Not Designed to Support Caregiving Youth Two federal programs, one under the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and one under the Department of Education, focus on helping at-risk youth populations, who, like caregiving youth, may face barriers to mental-health wellbeing or education. · Title IV-E Kinship Navigator Programs. Helps “kin” or relative caregivers, such as grandparents, learn about and access information and referral services to meet their own needs and the needs of the children they are raising when parents can no longer care for their children. According to officials from HHS’s Children’s Bureau, while some program resources could inadvertently assist some caregiving youth, it is not the stated purpose of the program. As such, the agency does not collect data that would identify these youth.

· Education for Homeless Children and Youths Program. Focuses on improving enrollment, attendance, and school success among the homeless student population. Education officials told us that while there may be overlap between the homeless student and caregiving youth populations, the agency does not collect data on who caregiving youth are or what they need. Source: GAO analysis of HHS and Department of Education information about these programs. | GAO-25-106947 |

Federal Actions to Implement a National Strategy to Support Family Caregivers Primarily Focus on Adults

The National Strategy to Support Family Caregivers (the strategy) includes youth in its definition of family caregivers and suggests ways government, nonprofit, and private sector stakeholders can recognize and support this population.[31] Overseen by HHS and jointly developed in 2022 by two legislatively-mandated advisory councils, the strategy defined family caregivers broadly to include “people of all ages, from youth to grandparents.”[32] The strategy suggested actions that stakeholders at every level may adopt, though actions taken by stakeholders are voluntary, according to HHS officials. These actions include training professionals to use the broadest definition of family caregivers, prioritizing research for unserved caregiving populations, and making available respite programs that meet the unique needs of caregiving youth.

HHS and other federal agencies identified actions in support of the strategy that have primarily focused on adult caregivers. For example, two reports on federal implementation of the strategy identified over 350 actions that federal agencies will take or have taken.[33] In these reports, federal agencies’ actions generally focus on adults rather than youth. According to HHS officials, the RAISE Family Caregivers Act directed federal agencies to identify actions to better recognize and support those caregivers that are served under existing federal programs. As discussed earlier, individuals eligible to receive services under the three federal caregiver support programs primarily focus on adult caregivers. HHS officials told us the agency’s work mainly consists of providing resources and technical assistance to federal, state, or local stakeholders to assist them with aspects of the strategy they want to carry out.[34] For example, with regard to youth, HHS officials told us the agency supported the National Academy for State Health Policy who worked with the American Association of Caregiving Youth to develop a guide for organizations on how to address the needs of caregiving youth.[35]

While VA’s Caregiver Support Program focuses on providing services to adult caregivers, VA has taken some steps in response to the strategy to support research on caregiving youth within the VA system. Specifically, in collaboration with other researchers, the VA’s veteran and caregiving research center developed a framework for conducting research on caregiving youth to better understand the contexts of family caregiving and the role of caregiving youth.[36] In addition, the agency held several presentations in 2024 about the importance of this research. According to VA officials, this investment in research on providing care for veterans and its impact on youth and family systems will help set the stage for future VA policy and actions.

England’s National Policy Was Informed by Research and Supports Caregiving Youth Through Coordinated Efforts Across Government and Other Organizations

England’s national government established a policy in 2014 that called for local governments to take reasonable steps to identify and conduct a needs assessment for caregiving youth in their area, according to key stakeholders we interviewed in England.[37] Local governments then address those needs or direct caregiving youth to other organizations that can.

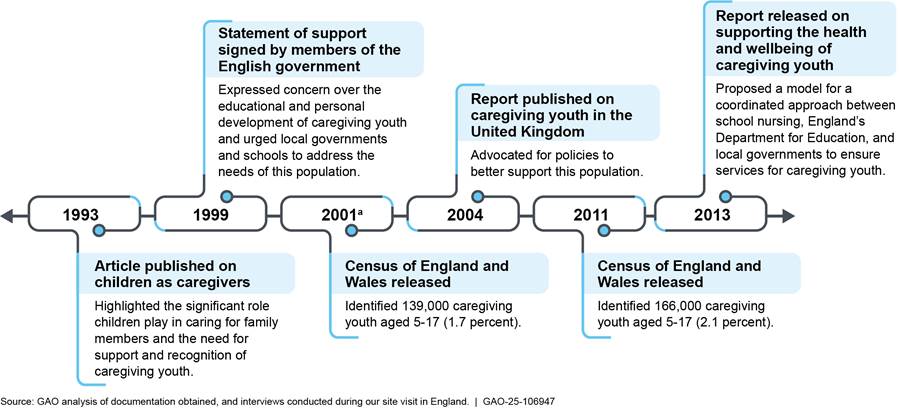

Research promoted awareness about caregiving youth in England and played a role in prompting England’s policy response. Stakeholders we interviewed told us that they and some government agencies published several articles and reports during the 2 decades that preceded the national policy, highlighting caregiving youth as a vulnerable population that needs to be recognized and supported. Before the national policy was passed, members of the national government signed a statement in support of caregiving youth, urging local government leaders and schools to do more to raise awareness about and assist this population (see fig. 4). In addition, one stakeholder noted that in 2001 the national government began tracking the number of caregiving youth nationwide through England’s census. According to stakeholders we interviewed, these efforts, combined with youth involvement in promoting awareness about their caregiving experiences, helped build support for a national policy.

Figure 4. Selected Research and Events Stakeholders Identified as Informing England’s National Policy to Support Caregiving Youth

aThe year caregiving youth were counted on the Census for the first time.

England’s national government allows its local governments some flexibility in implementing the national policy while also specifying broad requirements. For example, according to both national and local government leaders we interviewed, local governments can use different assessments to evaluate the needs of caregiving youth, but any assessments must capture the type and amount of care that youth provide and the effects it has on their wellbeing, education, and development. Stakeholders told us that individuals who conduct needs assessments of caregiving youth—often a social worker or school nurse—are trained and have sufficient knowledge and skills to do so.

Local governments in England coordinate with their own municipal agencies, charities, and schools to implement the national caregiving youth policy. For example, officials from one local government said they identify and assist caregiving youth through their municipal adult or children’s services agency. This provides staff with multiple ways to identify caregiving youth and the ability to support them and the adults they care for. Other local governments coordinate with charities to implement the national caregiving youth policy. Two charity leaders we interviewed said they provide a variety of services to caregiving youth on behalf of the local government, such as opportunities to socialize with peers, respite care to provide youth a break from their caregiving responsibilities, and counseling.

Local governments in England may also rely on schools to assist them in implementing the national caregiving youth policy. For instance, one local government official we spoke with said some schools designate a “young champion,” a person specifically charged to coordinate support for caregiving youth, assess their needs, or refer them to the local government on behalf of the school. According to documents provided by officials we interviewed at a national nonprofit organization, some schools provide lunchtime groups for caregiving youth and use school bulletins to raise awareness about caregiving youth more broadly.

Research continues to influence England’s national policy and advance public knowledge about caregiving youth. For example, two university researchers we interviewed told us about efforts to analyze public data sets to learn about the prevalence of caregiving youth, their demographics, and how the population has changed since the COVID-19 pandemic. These same researchers recently contributed to a report, commissioned by a nationally elected official, that called for a national plan to support caregiving youth. In 2022, an agency independent of government gathered information about the wellbeing and future goals of over 6,000 caregiving youth through a national survey and shared the results with caregiving youth projects across England.[38] In addition, according to an official with England’s Department for Education, the agency began collecting data in 2023 through its annual school survey of students to understand and address problems of absenteeism, which could lead to poor achievement rates among vulnerable students, including caregiving youth.

Conclusions

Family caregivers serve a critical role in our nation by providing care to their family members to help them remain healthy and in their homes and communities. Children and youth who serve as family caregivers face unique challenges balancing caregiving tasks with their own health, development, education, and wellbeing. Existing HHS and VA family caregiver support programs have primarily focused on providing assistance to adult caregivers, such as counseling, training, and respite care. However, when information on HHS’s website does not fully describe who is potentially eligible for services, such as working age individuals who are under 18, states and service providers may not be aware of their ability to support additional family caregivers under age 18 and provide them with needed assistance.

Recommendation for Executive Action

We are making the following recommendation to HHS:

The Secretary of HHS should clarify the participant eligibility requirements for the National Family Caregiver Support program on its website, including any flexibilities for states and service providers in defining “adult” for the purposes of eligibility. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to HHS, VA, and the Department of Education for review and comment. The Department of Education provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. VA did not provide comments. HHS concurred with our recommendation and provided written comments. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix IV, HHS said that the agency updated its website to correctly reflect eligibility for the National Family Caregiver Support Program. However, the agency’s website update did not include information that clarifies flexibilities that states and service providers may have to define “adult” in this context for the purposes of eligibility, as was suggested in the “note” section of its agency comments response letter. We believe adding information about any such flexibilities to HHS’s website will help ensure that states and service providers are aware of their ability to determine who is eligible to receive family caregiver support services.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, and the Secretary of Education. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have questions concerning this report, please contact me at LarinK@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Kathryn A. Larin

Director, Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues

List of Addressees

The Honorable Robert C. “Bobby” Scott

Ranking Member

Committee on Education and the Workforce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito

Chair

The Honorable Tammy Baldwin

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Robert Aderholt

Chairman

The Honorable Rosa DeLauro

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable Lois Frankel

House of Representatives

Our report examines (1) information on caregiving youth in the U.S.; (2) how federal caregiver support programs address the needs of caregiving youth; and (3) how England, a recognized leader in supporting caregiving youth, supports those youth through policy and programs. This appendix provides additional information on the methods we used to answer these objectives.

Review of National Data Sets

To address the first objective, we reviewed national surveys to determine whether they have information on the prevalence and characteristics of caregiving youth or former caregiving youth populations in the U.S. We identified these surveys through a literature search, a review of relevant federal agency datasets, and suggestions from federal agencies, including Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Education.

To assess whether these surveys captured information that would shed light on the prevalence of caregiving youth, we reviewed survey documentation, including questionnaires and data codebooks. We identified three surveys that met the following criteria: (1) surveyed a national population; (2) collected data since 2013; and (3) captured relevant elements on caregiving, such as variables that categorized respondents as caregivers. In addition, we conducted keyword searches of survey documentation for “care,” “assist,” “help,” and “support” to help identify variables related to caregiving. When a survey included adult respondents, we assessed whether the survey collected information that would identify respondents as former caregiving youth, such as respondents’ age and the duration of their caregiver role.

We found three annual surveys that captured caregiving youth or former caregiving youth: the American Time Use Survey, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, and the National Study of Caregiving.[39] To further understand the extent to which these surveys captured caregiving youth and former caregiving youth populations, we reviewed their survey design, how the data was manipulated after it was collected, and relevant data elements. See appendix II for more information about these three surveys.

Selected State Survey Data

Through interviews with stakeholder organizations, we identified three states that collected data on caregiving youth through surveys. While the results from these selected state surveys are not necessarily representative of all states, they serve as examples of the experiences of caregiving youth in the U.S.

Rhode Island

As part of our effort to gather information on the prevalence, characteristics, and experiences of caregiving youth, we analyzed 2023 survey data from the Rhode Island Department of Education’s (RIDE) “SurveyWorks,” the most recent available data during the time of our review. Each year, RIDE administers SurveyWorks to primary and secondary school students across Rhode Island to help inform classroom practice and school improvement. The survey includes variables on school-related outcomes, such as how often students are prepared for class, as well as students’ demographics (e.g., race). The survey defines caregiving as “taking care of anyone in your family, such as siblings, parents, and/or grandparents.” This definition also includes babysitting activities, which was not included in the scope of our review. The survey distinguishes caregivers by whether they care for a family member “part of the day” or “most of the day.”

We assessed the reliability of relevant variables by conducting electronic testing of the data for completeness and accuracy and interviewing knowledgeable officials about how the data were collected and maintained. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable to report on what is known about SurveyWorks respondents in Rhode Island who identified as caregiving youth.

We calculated and analyzed descriptive statistics to determine the characteristics of survey respondents in Rhode Island who identified as caregiving youth. Specifically, we calculated the percentage breakdown of caregiving youth across race and gender categories. We also calculated the proportions of students that were caregiving youth across middle and high school levels, race, and gender, and then compared these proportions between different groups, such as female versus male students, to determine whether caregiving was more prevalent in some groups compared to others.

We developed and estimated linear regression models to shed light on the challenges caregiving youth in Rhode Island face. These models estimated the association between providing care and various outcomes (e.g., how often students are prepared for class). The models controlled for students’ race, gender, grade level, and unobservable, school-varying factors (e.g., classroom rigor). The estimated associations reflected differences in outcomes between students who cared for a family member and those who did not. We only report on whether providing care was positively or negatively associated with an outcome. The models do not allow us to say whether an outcome is caused by caregiving because they do not capture factors that can influence an outcome, such as socioeconomic information.

The survey design presented a few limitations to what we could say about caregiving youth in Rhode Island. First, the survey is not representative of the entire youth population in Rhode Island. Second, the survey does not capture caregiving information from primary school students in Rhode Island.

Colorado

We also reported on the proportions of caregiving youth in different demographic categories using the results from the 2023 wave of the Healthy Kids Colorado Survey, the most recent available data during the time of our review. The survey, administered by Colorado’s Department of Public Health & Environment, was designed to obtain information on young people’s health and is representative of the state’s middle and high school students. The 2023 survey wave included a newly implemented question on caregiving, which identified caregivers as those who “care for someone in their family or household who is chronically ill, elderly, or disabled with activities they would have difficulty doing on their own one or more days per week.” Based on our review of documentation about the dataset, we determined that these data were sufficiently reliable to report on what is known about caregiving youth in Colorado.

Florida

We reported on the proportions of caregiving youth in different demographic categories using the 2024 results from the Florida Youth Tobacco Survey, administered by Florida’s Department of Health. This survey monitors and evaluates progress in Florida’s tobacco control program, and it is representative of the state’s population of middle and high school students. The survey’s definition of caregiving is similar to that used in the Healthy Kids Colorado Survey. Specifically, it captures the days per week students served as caregivers. We also reported the average time spent caregiving from a study that analyzed data from the 2019 round of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey for Florida. Department officials stated that Florida’s survey captured caregiving in the 2019 and 2021 rounds, but the state has since opted out of participating in this survey. Based on our review of documentation about these datasets, we determined that these data and studies that used these data were sufficiently reliable to report on what is known about caregiving youth in Florida.

GAO Survey of Former Caregiving Youth

To learn more about the experiences of caregiving youth in the U.S., we developed and administered a web-based, anonymous survey of a sample of young adults aged 18 to 25 who, while under the age of 18, cared for a family member with functional limitations due to aging, a health condition, or a disability. The survey was distributed through organizations that serve family caregivers that may have connections to caregiving youth and several social media outlets.

The survey included a total of 29 questions, comprised of a mix of closed- and open-ended questions. These questions asked respondents about their caregiving experiences, including tasks they performed, challenges they faced as a caregiver, and what additional types of support they believe could have addressed their needs. As part of the survey design process, we conducted four pretests to ensure the questions were clear and answerable, and we incorporated feedback, as appropriate. The survey was available to respondents between March and April 2024.

We received a total of 87 survey responses, 43 of which we considered eligible based on the current age of the respondent, the age of the respondent when they provided care, and the completion of all the survey questions. In reporting survey results, we used the following qualifiers to characterize responses from respondents—nearly all (40–43); many (26–39); some (10–25); and few (1–9).

Survey respondents were given the option to remain anonymous or to speak with GAO to expand on the challenges they faced or supports from which they could have benefited. GAO conducted semi-structured interviews with five of the 43 respondents. Findings from our survey and interviews with these respondents were gathered for illustrative purposes only and are not generalizable to all caregiving youth in the U.S.

Literature Search

To address the first objective, we conducted a literature search to identify studies published between 2013 and 2024 that discuss what is known about caregiving youth in the U.S. We performed keyword searches of databases, such as Scopus, MEDLINE, Social SciSearch, and CINAHL, using search terms such as “caregiving youth” and “parental illness.”

We made final study selections based on whether the research was peer reviewed and conducted with subjects from the U.S.[40] We also selected studies that defined caregiving youth as minors under the age of 18 who provide care for aging family members with functional limitations or family members with a health condition or a disability, which can include younger siblings.

We identified four studies that discussed caregiving youth in the U.S., the risks they are prone to, and policies or resources they identified as important. We conducted detailed reviews of these studies to assess the soundness of the reported methods and deemed them sufficient, credible, and methodologically sound for our purposes.

England Case Study

To address our third objective and gather information about how England supports caregiving youth through policy and programs, we conducted a site visit in England. We selected England based on literature we reviewed and our interviews with researchers who have knowledge of or otherwise studied caregiving youth. During our visit, we attended the April 2024 International Young Carers Conference in Manchester, England. Following the conference, we interviewed key stakeholders including researchers, practitioners, and policy advocates from England to learn more about their efforts to address the needs of caregiving youth. We also interviewed officials from the English Departments for Education and of Health and Social Care, national nonprofit organizations that provide support to caregiving youth, and local government leaders who connect caregiving youth with services. We did not conduct an independent legal analysis to verify information about the laws, regulations, or policies in England. Instead, we relied on interviews, appropriate secondary sources, and other sources to support our findings.

Interviews and Review of Documents

To inform our first and second objectives, we reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations, and documents, and interviewed officials from HHS’s Administration for Community Living, the Children’s Bureau (an office of the Administration for Children and Families), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) Veterans Health Administration; and the Department of Education’s Offices of Elementary and Secondary Education Programs, Special Education Programs, and Student Support and Accountability.

To obtain additional information on all our objectives, we interviewed researchers and representatives from 16 stakeholder organizations selected for their work on caregiving, caregiving youth, or certain health conditions. These organizations included the Alzheimer’s Association, ALS of Texas, ALS of Wisconsin, American Association of Caregiving Youth, AARP, American Cancer Society, California State University Shiley Institute for Palliative Care, Caregiver’s Guardian, Elizabeth Dole Foundation (Washington D.C. and San Diego County), Generations United, Hope Loves Company, National Alliance for Caregiving, National Alliance on Mental Illness, United Community Center, and USAging.

We also determined that the information and communication component of federal internal controls was significant to the evaluation of federal caregiver support programs for our second objective, along with the underlying principle that management should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[41] We assessed HHS’s efforts to externally communicate quality information to achieve its objectives against these internal control standards.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

We found three national surveys that collect some information on caregiving, although they are limited in capturing the prevalence and characteristics of caregiving youth or former caregiving youth nationwide:

1. American Time Use Survey (ATUS). The Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics ATUS annually collects information on how Americans spend their time across various activities, but the information collected only includes a subset of youth and may not capture all caregiving activities. Specifically, the ATUS collects information from respondents ages 15 and older, which excludes youth under the age of 15 who may also be providing care. In addition, because the ATUS records respondents’ activities on a randomly chosen day, it may not be representative of their typical routines, including caregiving activities for a family member on other days.[42]

2. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. The Centers for Disease Control’s system of surveys annually asks adults about health-related behaviors and conditions and includes questions on caregiving activities through state-administered surveys. However, the method for selecting survey respondents and type of data collected make it difficult to identify adults who were providing care in their youth. Specifically, the survey is designed to select respondents from households at random and, as a result, may overlook certain household members who were caregivers. Further, the survey uses ranges to collect information on respondent’s age and length of time in a caregiving role, which makes it difficult to accurately determine whether the respondent began their caregiving role in their youth. Unlike ranges, information on the respondent’s actual age and length of time in a caregiving role would allow users of the survey data to more accurately identify the age of the respondent when they began providing care for a family member.[43] In addition, states may choose whether to include questions on caregiving activities in their surveys. Therefore, these data may not fully capture caregiving throughout the U.S.

3. National Study of Caregiving. The University of Michigan and Johns Hopkins University’s study annually asks questions of family and other unpaid caregivers to older persons who experience limitations in carrying out daily activities, such as eating, bathing, or preparing hot meals.[44] However, the survey focuses on those individuals who care for Medicare recipients ages 65 and older. As such, former caregiving youth caring for family members under the age of 65 or younger siblings with a disability would not be captured.

Appendix III: Additional Data on Caregiving Youth from Surveys in Colorado, Florida, and Rhode Island

We analyzed data and reviewed the results from three state surveys of middle (grades 6 through 8) and high school (grades 9 through 12) students to describe what is known about the race, ethnicity, and gender of caregiving youth in these states, as well as the amount of time they spent providing care for family members.[45] We also describe the types of challenges caregiving youth in these states face, including with mental and physical health, peer relationships, school engagement and belonging, and postsecondary educational choices.

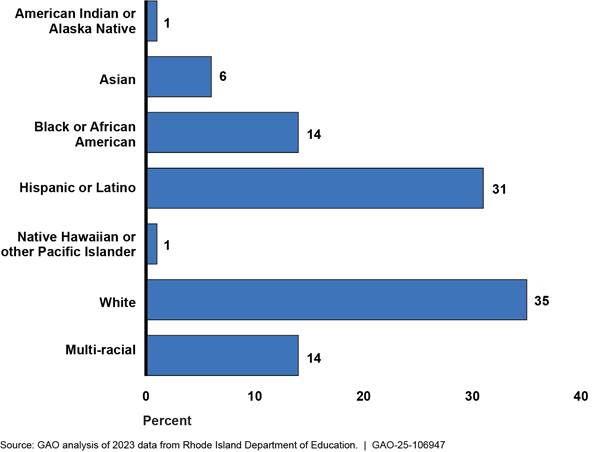

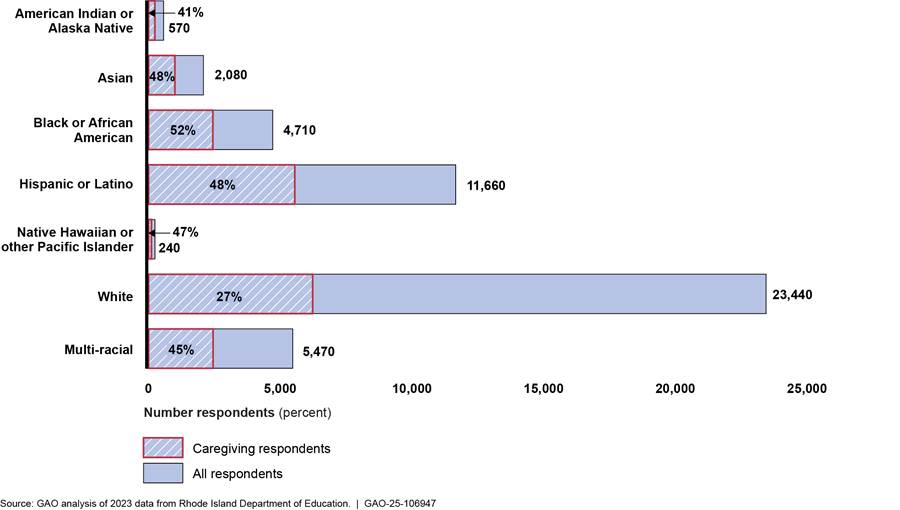

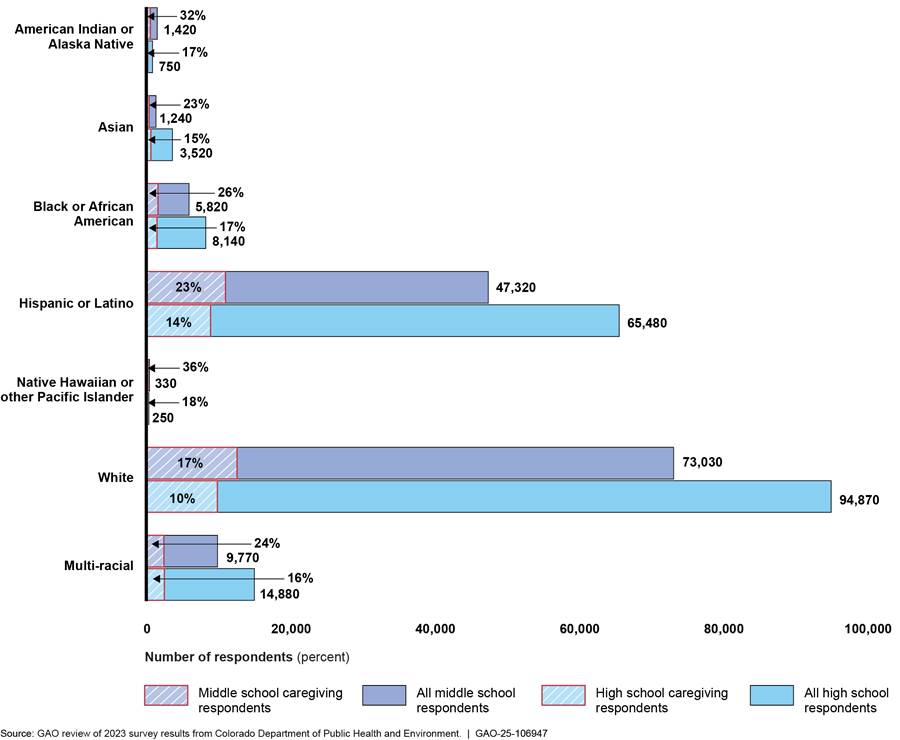

Caregiving youth by race and ethnicity. We found that non-White student groups made up the majority of caregiving youth surveyed in Rhode Island (see fig. 5).[46] Also, according to our analysis of the Rhode Island survey data and the survey results from Colorado, greater proportions of Black, Hispanic or Latino, and multi-racial middle and high school students were caregiving youth compared to the proportion for White students (see figs. 6 and 7).[47] On the other hand, we found no significant differences between the proportions of White, Black, and Hispanic students who were caregiving youth in Florida.[48]

Figure 5: Racial and Ethnic Composition of Middle and High School Students Surveyed in Rhode Island Who Were Caregiving Youth

Note: The Rhode Island survey used a broad definition of caregiving youth to include youth babysitting for siblings. Therefore, any variation in the proportion of students who babysit for siblings by different demographic characteristics, such as race and ethnicity or gender, may impact these results. The percentages shown are rounded to the nearest whole number and may not add up to 100.

Figure 6: Percentage of Middle and High School Students Surveyed in Rhode Island Who Were Caregiving Youth, by Race and Ethnicity

Note: The Rhode Island survey used a broad definition of caregiving youth to include youth babysitting for siblings. Therefore, any variation in the proportion of students who babysit for siblings by different demographic characteristics, such as race and ethnicity or gender, may impact these results. Respondent counts and percentages shown are to the nearest 10 and whole number, respectively.

Figure 7: Percentage of Middle and High School Students Surveyed in Colorado Who Were Caregiving Youth, by Race and Ethnicity

Note: Respondent counts and percentages shown are rounded to the nearest 10 and whole number, respectively. In addition, “Asian” students include two categories from the survey—those who are “East/Southeast Asian” and those who are “South Asian.”

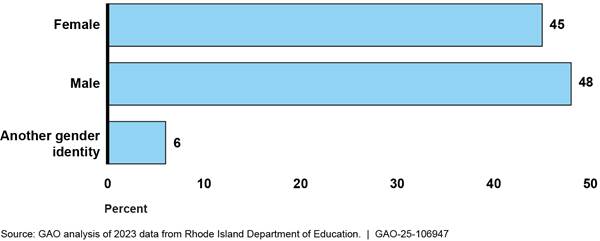

Caregiving youth by gender. We found that caregiving youth were nearly evenly split between male and female students in Rhode Island, according to our analysis of data from this state (see fig. 8).[49] We also found comparable percentages of the shares of male and female students who were caregiving youth in each of the three states, according to our analysis of the Rhode Island survey data and the survey results from Florida and Colorado (see figs. 9 and 10 for survey results from Rhode Island and Colorado).[50]

Figure 8: Gender Composition of Middle and High School Students Surveyed in Rhode Island Who Were Caregiving Youth

Note: The Rhode Island survey used a broad definition of caregiving youth to include youth babysitting for siblings. Therefore, any variation in the proportion of students who babysit for siblings by different demographic characteristics, such as race and ethnicity or gender, may impact these results. The percentages shown are rounded them to the nearest whole number and may not add up to 100.

Figure 9: Percentage of Middle and High School Students Surveyed in Rhode Island Who Were Caregiving Youth, by Gender

Note: The Rhode Island survey used a broad definition of caregiving youth to include youth babysitting for siblings. Therefore, any variation in the proportion of students who babysit for siblings by different demographic characteristics, such as race and ethnicity or gender, may impact these results. Respondent counts and percentages shown are rounded to the nearest 10 and whole number, respectively.

Figure 10: Percentage of Middle and High School Students Surveyed in Colorado Who Were Caregiving Youth, by Gender

Note: Respondent counts and percentages shown are rounded to the nearest 10 and whole number, respectively.

Amount of time spent providing care. According to the survey results from Florida, the amount of time spent providing care was higher among Black and Hispanic or Latino students and male students in this state relative to White students and female students.[51]

Effects of providing care on youth. Results from the Rhode Island and Florida surveys showed some differences in the effects of providing care on youth based on the time spent providing care, and in some cases, by race and ethnicity. For example:

· Mental and physical health. Among caregiving youth in Rhode Island, survey results showed that those providing care for part of the day were more likely to have felt sad or hopeless for 2 or more weeks during the past year if they were White compared to if they were Black. However, the survey results found no differences in sadness when looking at time spent caregiving among youth of different ages. Specifically, providing care for part and most of the day was linked to a greater risk of experiencing sadness among both older and younger students.

According to the survey results from Florida, caregiving youth were likely to experience insufficient sleep if they were White, but not if they were Black.

· Peer relationships. In our analysis of the survey data from Rhode Island, we found differences in the relationship between providing care and bullying based on time spent providing care for a family member. For example, youth who were providing care most of the day were more likely to be bullied at school in the past year compared to youth who were providing care part of the day. Likewise, the survey results from Florida found that caregiving youth experienced higher levels of peer difficulties, such as bullying or physical conflict, with Asian youth experiencing greater peer difficulties compared to White youth.

· School engagement and belonging. In our analysis of the survey data from Rhode Island, we found some differences in the relationship between providing care and experiencing stress that interfered with school activities, based on the amount of time spent providing care for a family member. Specifically, stress interfered with participation in school activities to a greater extent for youth providing care for most of the day compared to youth providing care for part of the day.

· Postsecondary education choices. According to our analysis of the survey data from Rhode Island, we found some differences in the relationship between the amount of time spent providing care for a family member and thinking about future education. Specifically, youth providing care for most of the day were less likely to think about attending a 2-year or 4-year college, or trade school, compared to youth providing care for part of the day.

GAO Contact

Kathryn A. Larin, LarinK@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact above, Nora Boretti (Assistant Director), Claudine Pauselli (Analyst in Charge), Christina Cuthbertson, Lincoln Dow, and Trevor Osaki made key contributions to this report. Also contributing to this report were Gina Hoover, Aaron Olszewski, Jay Palmer, Lindsay Shapray, Joy Solmonson, Curtia Taylor, and Seyda Wentworth.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP Family Caregiving, 2020 Report: Caregiving in the U.S., May 2020. Family members can include parent, guardian, grandparent, or other relative.

[2]For the purposes of this report, we refer to caregiving youth as those individuals under the age of 18 who provide care for family members with functional limitations due to aging, a health condition, or a disability. Caregiving youth who provide babysitting care for younger siblings are not included in the scope of this review.

[3]We identified England as a leader in addressing caregiving youth based on our review of literature on caregiving youth and interviews with researchers who have knowledge of or otherwise studied caregiving youth.

[4]We conducted detailed reviews of these studies to assess the reported methods and deemed them sufficient, credible, and methodologically sound for our purposes.

[5]SurveyWorks data from 2023 was the most recent available during the time of our review. We determined that these data, along with the survey results from Colorado and Florida, were sufficiently reliable to report information on what is known about caregiving youth in these states by conducting electronic testing or reviewing relevant documentation, among other steps. Unlike the surveys from Colorado and Florida, Rhode Island’s survey is not generalizable to the entire youth population in that state.

[6]Within HHS, these agencies included the Administration for Community Living (ACL), the Children’s Bureau, an office of the Administration for Children and Families, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Within VA, the agency included was the Veterans Health Administration. Within the Department of Education, these agencies included the Offices of Elementary and Secondary Education and Special Education Programs.

[7]HHS Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years 2022 through 2026, Goal 3: Strengthen Social Wellbeing, Equity and Economic Resilience, Objective 3.3. As of February 2025, HHS’s website stated that an updated strategic plan is forthcoming. See https://www.hhs.gov/about/strategic-plan/2022-2026/index.html, accessed February 18, 2025.

[8]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

[9]In England, caregiving youth are referred to as “young carers.” For the purposes of this review, we generally refer to youth providing care to family members in England and the United States as “caregiving youth” unless we are referring to the title of a program or event in England.

[10]Older Americans Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-73, tit. III, pt. E, as added by Pub. L. No. 106-501, tit. III, § 316, 114 Stat. 2226, 2253 (2000) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. §§ 3030s – 3030s-2). HHS’s Administration for Community Living (ACL) administered the program during our review. In March 2025, HHS announced a restructuring of the department and its programs, including ACL and its programs.

[11]The programs are the Program of General Caregiver Support Services (PGCSS) and the Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC). See 38 U.S.C. § 1720G.

[12]Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act of 2017, Pub. L. No. 115-119, 132 Stat. 23 (2018). See also Supporting Grandparents Raising Grandchildren Act, Pub. L. No. 115-196, 132 Stat. 1511 (2018).

[13]The Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics administers the American Time Use Survey. HHS’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administers the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. The National Study of Caregiving is funded by the National Institute on Aging and led by two universities.

[14]Katherine E.M. Miller, Joanna L. Hart, Mateo Useche Rosania, and Norma B. Coe, “Youth Caregivers of Adults in the United States: Prevalence and the Association Between Caregiving and Education,” Demography, vol. 61, no. 3 (2024): 829-847. These estimates captured some young adults (i.e., aged 18) and non-family members. They are also based on different definitions of caregiving, which included providing different amounts of assistance with activities of daily living (e.g., bathing or assisting with medication) or instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., shopping or managing finances) or providing care for an adult with a condition related to aging. In addition, according to our interview with the authors of this study, survey data needed to be averaged across 7 years (i.e., 2013-2019) to ensure a large enough sample size for the estimates.