REGULATORY FLEXIBILITY ACT

Improved Policies for Analysis and Training Could Enhance Compliance

Committee on Small Business,

House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106950. For more information, contact Jill Naamane at naamanej@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106950, a report to the Chairman of the Committee on Small Business, House of Representatives

Improved Policies for Analysis and Training Could Enhance Compliance

Why GAO Did This Study

RFA was enacted in 1980 in response to concerns about the effect of federal regulations on small entities. SBA’s Office of Advocacy provides RFA compliance training to federal agencies.

GAO was asked to review agencies’ implementation of RFA. This report examines CMS’s, Energy’s, EPA’s, and SBA’s RFA analyses for 2022–2023 rules and the extent to which Advocacy has provided RFA training, among other objectives.

GAO selected these agencies because they published the greatest numbers of significant final rules and RFA analyses in fiscal years 2022 and 2023. Collectively, they published 30 percent of significant final rules and 36 percent of analyses. GAO reviewed all 55 proposed rules these agencies certified and all 20 rules that contained initial and final regulatory flexibility analyses. GAO compared these rules and agency policies for conducting RFA analyses against RFA requirements and key practices recommended by Advocacy, OMB, and GAO. GAO also reviewed Advocacy’s training activities.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations, including that CMS’s, Energy’s, and EPA’s policies and procedures be revised to more fully incorporate recommended elements; SBA develop RFA compliance procedures; and Advocacy establish procedures for RFA compliance training. Advocacy and HHS agreed, SBA partially agreed, and Energy and EPA neither agreed nor disagreed. GAO maintains that its recommendations should be addressed.

What GAO Found

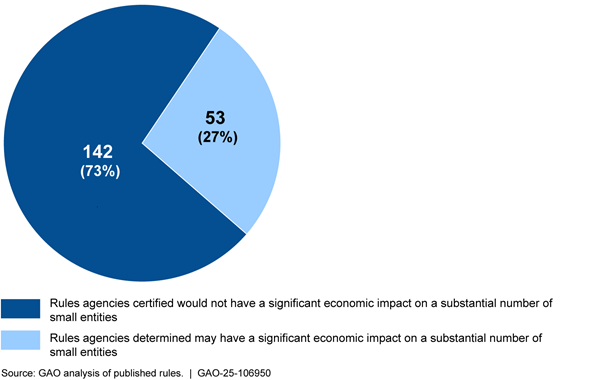

To comply with the Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA), agencies generally must conduct regulatory flexibility analysis when promulgating a new rule. This analysis assesses the rule’s potential impact on small entities and explores alternatives for minimizing the rule’s economic impact. Alternatively, agencies may certify that a rule would not have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities, and that such analysis is therefore not needed. GAO found that in fiscal years 2022 and 2023, federal agencies published 195 significant final rules (e.g., those with a large annual effect on the economy) that were subject to RFA requirements. Agencies certified in 142 instances (73 percent) that the proposed rule would not have a significant impact on a substantial number of small entities.

GAO also found that analyses conducted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Department of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Small Business Administration (SBA) generally met statutory requirements. However, the analyses were sometimes inconsistent with recommendations from SBA’s Office of Advocacy and key practices from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and GAO for conducting regulatory and economic analysis. For example:

· Certifications. The certifications GAO reviewed generally met statutory requirements, such as providing a statement of factual basis to support the certification. However, GAO found that several of the analyses supporting the certifications did not include information recommended by Advocacy, such as the rule’s potential benefits for small entities or the thresholds used for determining “significant impact” or “substantial number.”

· Regulatory flexibility analyses. The initial and final regulatory flexibility analyses that GAO reviewed generally met statutory requirements, such as describing and estimating the number of affected small entities. However, the analyses were sometimes inconsistent with recommended practices from Advocacy, OMB, and GAO. For example, some did not disclose their data sources, and none considered the indirect costs of the rule.

Fully incorporating Advocacy guidance and other recommended elements into RFA policies and procedures could help CMS (within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)), Energy, and EPA enhance their ability to analyze a rule’s economic impact on small entities. Additionally, SBA does not have policies and procedures specific to RFA requirements. Developing such procedures could improve the agency’s ability to ensure consistent compliance.

Advocacy is charged with providing training to agencies on RFA compliance, but it has not trained 87 of 181 rulemaking agencies since its training program began in 2003. Further, in fiscal years 2019–2023, 26 of the 41 agencies that Advocacy identified as having deficiencies in their RFA analyses did not receive training. Advocacy does not have formal policies and procedures for its RFA training program, such as methods for identifying all rulemaking agencies or targeting those in need of training. By establishing training policies and procedures, Advocacy could better equip agencies to comply with RFA requirements.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CMS CFPB |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Consumer Financial Protection Bureau |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

OMB OSHA |

Office of Management and Budget Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

|

RFA |

Regulatory Flexibility Act |

|

SBA SBREFA |

Small Business Administration Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 10, 2025

The Honorable Roger Williams

Chairman

Committee on Small Business

House of Representatives

Dear Mr. Chairman:

Federal agencies publish thousands of regulations each year, with 3,088 final rules published in fiscal year 2023, according to the Federal Register. The Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) was enacted more than 4 decades ago in response to concerns about the effect federal regulations can have on small entities, such as small businesses, small governmental jurisdictions, and certain small not-for-profit organizations. For example, regulations can disproportionately affect small entities because they have fewer resources and personnel to comply with new requirements.

RFA requires rulemaking agencies to conduct a regulatory flexibility analysis, which assesses a rule’s potential impact on small entities and considers significant alternatives that may reduce that burden.[1] Alternatively, agencies may certify that a rule would not have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities, and that a regulatory flexibility analysis is therefore not required.

We have previously found that uncertainties about and varying agency interpretations of RFA requirements limit the act’s application and effectiveness.[2] Members of Congress and small businesses have raised questions about how agencies are evaluating the impact of their rulemaking on small entities.

You asked us to review agencies’ implementation of RFA. This report examines the extent to which

1. significant rules published in fiscal years 2022 and 2023 included required RFA analysis or were certified as not having a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities,

2. selected agencies followed RFA requirements and related guidance in certifying their rules,

3. selected agencies followed RFA requirements and related guidance in performing required RFA analysis,

4. selected agencies’ policies and procedures are consistent with RFA and related guidance, and

5. the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Office of Advocacy has provided agencies with required compliance training.

For our first objective, we analyzed all 283 final rules that were deemed significant under Executive Order 12866 and published in the Federal Register in fiscal years 2022 and 2023.[3] For the 195 rules with a proposed rulemaking, we analyzed the proposed and final rule notices to quantify how many rules included a regulatory flexibility analysis or a certification that analysis was not required.[4]

For the second, third, and fourth objectives, we selected for review four agencies that were among those with the greatest number of significant final rules and regulatory flexibility analyses, among other criteria. We selected the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Department of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and SBA. Collectively, these four agencies published 30 percent of the significant final rules and conducted 36 percent of the regulatory flexibility analyses.

For the second objective, we selected all 55 final rules certified by these agencies in fiscal years 2022 and 2023. We reviewed the Federal Register notices and rule dockets for their corresponding proposed rules.[5] We examined the extent to which the rule notices were consistent with RFA requirements, the Office of Advocacy’s guide on complying with RFA, and other key practices for rulemaking.[6]

For the third objective, we reviewed Federal Register notices and related documents from the rule dockets for all 20 significant rules for which the selected agencies performed an initial and final regulatory flexibility analysis. We compared agencies’ analyses against RFA requirements, the Office of Advocacy’s guide on complying with RFA, and other key practices for rulemaking.

For the fourth objective, we reviewed internal agency policies and procedures for conducting initial and final regulatory flexibility analyses or certifying that such analyses were not required. We also interviewed agency officials regarding their policies and procedures for RFA compliance. We assessed these policies and procedures against RFA requirements, Executive Order 13272 requirements, the Office of Advocacy’s guide on complying with RFA, and other key practices for rulemaking.[7]

For the fifth objective, we analyzed SBA’s Office of Advocacy annual reports for fiscal years 2019 to 2023 (the five most recent reports available) to determine how frequently RFA training was provided and to which agencies. We also interviewed Advocacy officials about their training and compared their training efforts against Executive Order 13272 requirements and federal internal control standards.[8] We also compared Advocacy’s training performance measure against key practices to help effectively implement federal evidence-building and performance-management activities.[9] For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Regulatory Flexibility Act

The uniform application of regulations can disproportionately affect smaller entities, as they often have smaller staffs and fewer resources to comply with new rules and absorb increased compliance costs. RFA was enacted in 1980 in part to address this disparity. The act requires that federal agencies analyze the impact of proposed and final regulations on small entities.[10] When the agency does not certify that a proposed rule will not, if promulgated, have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities, it must prepare a regulatory flexibility analysis that describes the impact of the rule on small entities and any significant alternatives that would minimize this impact while achieving the rule’s objectives.

RFA does not seek preferential treatment for small entities, nor does it require agencies to adopt regulations that impose the least burden on small entities. Rather, it requires agencies to use an analytical process that identifies barriers to small business competitiveness.

RFA’s requirements only apply to rules that are subject to notice-and-comment rulemaking under section 553 of the Administrative Procedure Act or another law.[11] Not all rulemaking includes a notice of proposed rulemaking. Agencies often publish final rules without such a notice, citing “good cause” (e.g., the rule pertains to a technical correction) and other statutory exceptions, according to our prior work.[12]

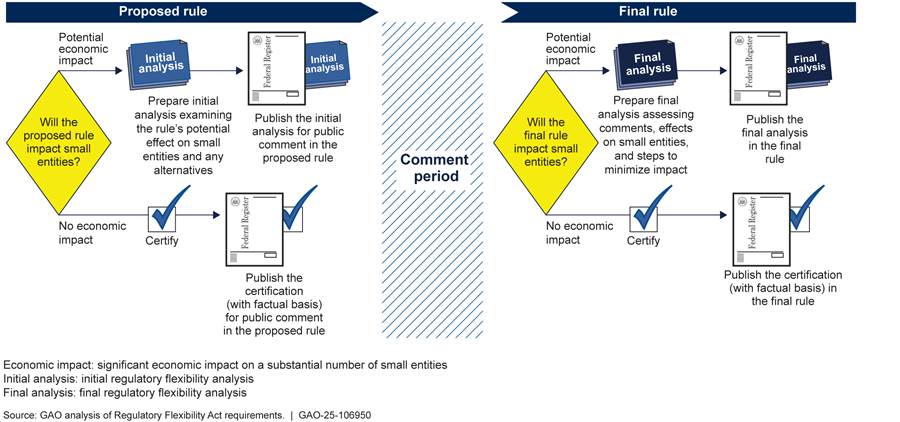

For every proposed rule, RFA requires agencies to prepare an initial regulatory flexibility analysis, unless the agency head certifies that the proposed regulation would not have a “significant” economic impact on a “substantial” number of small entities (see fig. 1). The act does not define either of these terms, however, and we have previously found that compliance with RFA varies because agencies interpret them differently.[13] These initial regulatory flexibility analyses must describe the rule’s potential impact on small entities. The analyses must also describe any significant alternatives to the rule that would minimize the impact on small entities while achieving its goals. RFA requires that agencies publish their initial regulatory flexibility analysis, or a summary, in the Federal Register with the proposed rule.

Following a period for public comment on the proposed rule, RFA requires agencies to conduct a similar analysis when they promulgate the final rule—the final regulatory flexibility analysis. This analysis must address significant issues raised in comments received on the initial regulatory flexibility analysis. It also must include a description of the steps the agency took to minimize the rule’s significant economic impact on small entities. Agencies then must publish the final analysis, or a summary, with the final rule.

If the head of the agency certifies in the Federal Register that the proposed or final rule would not have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities, the agency does not have to conduct the initial or final analysis. This certification can be made in lieu of the analysis at either the proposed or final rule stage, or at both stages.[14]

The Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996 amended RFA in response to concerns by the small business community that federal regulations were too numerous, complex, and expensive to implement.[15] The act requires agencies to include a statement providing a factual basis for certifying that regulatory flexibility analysis is not required, among other changes.[16]

Executive Orders on Regulatory Review

Executive Order 12866, Regulatory Planning and Review, requires agencies to submit draft or proposed significant regulatory actions for review to the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs before they are published in the Federal Register.[17] Under the order, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs has up to 90 days (which can be extended) to review a rule. This review, known as the interagency review process, helps to promote interagency review of draft proposed and final regulatory actions to avoid inconsistent, incompatible, or duplicative policies.

For significant rules, Executive Order 12866 requires agencies to complete a regulatory impact analysis. The order deems rules to be significant based on specific criteria, such as having a large annual effect on the economy as defined by the order.[18] This regulatory impact analysis evaluates the costs and benefits anticipated from the regulatory action. OMB’s Circular A-4 provides guidance on developing this analysis.[19] To reduce duplication and overlap, agencies may use other required regulatory analyses, such as the regulatory impact analysis, to satisfy RFA requirements, provided the analyses address impacts on small entities.[20]

Executive Order 13272, Proper Consideration of Small Entities in Agency Rulemaking, requires agencies to develop and publish policies and procedures for complying with RFA.[21] It also requires agencies to engage with SBA’s Office of Advocacy during the interagency review process. If a draft regulation might have a significant impact on a substantial number of small entities, the agency must notify Advocacy.[22]

SBA’s Office of Advocacy

Advocacy is generally recognized as an independent office within SBA whose role is to serve as the independent voice for small businesses within the federal government.[23] RFA designates certain responsibilities to SBA’s Chief Counsel for Advocacy, including monitoring and reporting on agency compliance with RFA and providing information to agencies on such compliance.[24] To fulfill these responsibilities, Advocacy publishes annual reports evaluating agency compliance with RFA and Executive Order 13272. Advocacy also publishes a step-by-step guide for agency officials on complying with RFA.[25] In addition, Executive Order 13272 requires the Office of Advocacy to provide training to agencies on RFA compliance.[26] Advocacy also reviews federal rules for their impact on small businesses. Advocacy can submit formal comment letters to agencies regarding RFA compliance during a rule’s notice and comment period.

The Majority of Significant Rules Were Certified, and the Rest Included Analyses as Required

Federal Agencies Certified That Most Rules Would Not Have a Significant Impact on a Substantial Number of Small Entities

Most of the significant rules published by federal agencies in fiscal years 2022 and 2023 were subject to RFA requirements, according to our review.[27] According to our analysis, for 195 of 283 significant final rules (69 percent), agencies published a notice of proposed rulemaking and were required to comply with RFA’s requirements.[28] This result is consistent with our prior analysis of rulemaking government-wide, which found that about 65 percent of major rules published from 2003 through 2010 had a proposed rule.[29]

Of the 195 rules subject to RFA requirements, agencies certified in 142 instances (73 percent) that the proposed rule would not have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities (see fig. 2). In nearly all cases where agencies certified the proposed rule, they also certified the final rule.[30]

Figure 2: Percentage of Significant Proposed Rules in Which the Agency Certified No Significant Economic Impact, Fiscal Years 2022–2023

Note: We reviewed final significant rules published during fiscal years 2022 and 2023 that had a proposed rule (i.e., were subject to Regulatory Flexibility Act requirements). Some of the corresponding proposed rules may have been certified prior to this time frame.

Although agencies are not required to conduct further analysis if they certify the proposed rule, agencies chose to do so for 11 rules. For example:

· The Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security certified that a proposed rule amending the export control list would not have a significant impact on small entities.[31] The agency nevertheless conducted an analysis to consider alternatives that could accomplish the rule’s objectives while minimizing its impact on small entities.

· The Federal Aviation Administration certified a proposed rule that expanded implementation of an airport safety management system, but it requested comments on potential compliance costs specific to small entities.[32] After receiving feedback from many commenters about additional burdens on small airports, the agency conducted a final regulatory flexibility analysis. As a result, it changed the final rule to reduce the number of small airports affected.

Agencies Conducted Regulatory Flexibility Analyses When Required

Federal agencies completed regulatory flexibility analyses when required. Specifically, agencies determined that 53 proposed rules may have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities, and they conducted an initial regulatory flexibility analysis as required for all of them.

For 49 of the 53 rules where agencies conducted an initial regulatory flexibility analysis, they also conducted a final regulatory flexibility analysis. For the other four rules, the agency certified that the final rule would not have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities instead of conducting a final regulatory flexibility analysis.

Certifications by Selected Agencies Generally Met Statutory Requirements but Sometimes Did Not Align with Relevant Guidance

Our review of the 55 proposed rules that CMS, Energy, EPA, and SBA certified found that the certifications generally met RFA statutory requirements.[33] However, the analysis for many of these certifications did not include key elements recommended by Advocacy, OMB, and GAO.[34] In addition, in some cases, the basis for the certification, certification language, or some of the key certification elements were unclear.

Over Half of Certifications Concluded That the Proposed Rule Would Impact Some Small Entities but Not Significantly

In 32 of the 55 certifications we reviewed, the agencies determined that the proposed rule would affect some small entities or have some economic impact on small entities, but not a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities (see table 1). For example, EPA found that a proposed rule on asbestos reporting requirements would affect 14 small businesses that process asbestos, with 12 of them experiencing a cost impact of less than 1 percent of annual revenue.[35]

Table 1: Basis for Regulatory Flexibility Act Certifications in Selected Agencies’ Proposed Rules, Fiscal Years 2022–2023

|

Agency |

Rule impacts small entities but not a substantial number, or has some economic impact but not significanta |

Rule does not impact small entitiesb |

Rule does not have economic impactc |

Rule has beneficial impactd |

Total certifications |

|

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

13 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

21 |

|

Department of Energy |

0 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

6 |

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

12 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

21 |

|

Small Business Administration |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

|

Total |

32 |

10 |

8 |

5 |

55 |

Source: GAO analysis of published rules. | GAO‑25‑106950

Note: We reviewed final significant rules published during fiscal years 2022 and 2023. Some of the corresponding proposed rules may have been certified prior to this time frame.

aAgency determined that the proposed rule would affect some small entities or have some economic impact on small entities, but the impact would not be significant or substantial.

bAgency determined that the proposed rule would not impact small entities. This category includes rules that would impact entities that exceeded Small Business Administration size standards.

cAgency determined that the proposed rule does not have any economic impact. This category includes rules that do not impose requirements on regulated entities.

dAgency determined that the proposed rule has beneficial impact on small entities. This category includes rules that increase revenue to small entities.

In 10 of 55 proposed rule notices, the agency concluded that the rule would not impact small entities. This was typically because the rule regulated entities that exceeded SBA size standards or fell outside RFA’s definition of small entities. For example, CMS concluded that a proposed rule revising Medicare enrollment and eligibility would impose costs on the federal government and states rather than small entities.[36] In a few instances, the agency conducted some analysis to determine whether small entities would be affected. For example, EPA determined that one proposed rule amending recommendations for site remediation would affect 46 firms, none of which were small according to SBA size standards.[37]

In eight of 55 proposed rule notices, the agency concluded the rule would have no economic impact. These rules generally did not impose standards or requirements on regulated entities or pertained to the internal processes of the agency. For example, Energy found that a proposed rule revising a waiver process would not impose any new requirements on manufacturers, including small entities.[38]

Agencies can include supporting analysis in a certification, which can help small entities understand why the agency made the certification and enable them to comment effectively. The degree to which agencies included additional analysis to support a certification of no economic impact varied by agency and by rule. For example, for a proposed rule that reinstated prior standards for dishwashers and washing machines, Energy collected data from its compliance certification database to determine the number of small entities affected.[39] In contrast, for a different rule that would change definitions of general service lamps, Energy also certified its findings but did not include additional analysis in the proposed rule, such as quantifying the number of small entities.[40]

The agencies found that the remaining five of the 55 rules would have a beneficial impact on small entities because they reduced regulatory burden or had a positive net impact on revenue. For example, CMS found for one proposed rule that updating payment rates for inpatient psychiatric facilities would increase facility Medicare revenues by about 1.5 percent.[41]

The extent to which EPA included additional analysis to support a certification of beneficial impact varied by rule. For example, in a proposed rule on heavy-duty test procedures, EPA stated that the rule would have a beneficial impact by reducing testing burdens and adjusting other compliance provisions.[42] The agency did not include any analysis of the number of small entities affected or the cost impacts of these adjustments to small entities. In contrast, in a different proposed rule, EPA found that establishing an exemption for pesticides created through biotechnology would relieve regulatory burden, and it estimated the percentage of affected entities that were small and the potential cost savings per product to support that finding.[43]

Certifications Generally Met Statutory Requirements

Certifications we reviewed from the four selected agencies generally met RFA statutory requirements. As shown in table 2, nearly all certifications were published by the agency head or a designated official.[44] Agencies generally used the appropriate language to certify that the proposed rule would not have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities. Additionally, all of the proposed rules included a statement providing the factual basis or reasoning for the certification. Compliance with these statutory requirements helps make clear to affected small entities that the agency is certifying the proposed rule.

Table 2: Extent to Which RFA Requirements Were Met Among 55 Certifications from Selected Agencies, Fiscal Years 2022–2023

|

|

Rules with required element (out of 55) |

|

Certification statement came from head of agencya |

53 |

|

Certification stated that the rule “will not have a significant impact on a substantial number of small entities” |

52 |

|

Certification included a statement providing the factual basis for certifying the rule |

55 |

Source: GAO analysis of published rules and Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) requirements. | GAO‑25‑106950

Note: The selected agencies were the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Energy, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Small Business Administration. We reviewed final rules published during fiscal years 2022 and 2023. Some of the corresponding proposed rules may have been certified prior to this time frame.

aTwo EPA notices were signed by officials other than the head of agency. EPA told us that it has a standing delegation of authority for signature authority on proposed or final rule certifications. However, the two notices did not include information regarding this delegation of signing authority.

In six rules, CMS and SBA used unclear certification language that made it difficult to determine whether they were certifying the rule. For example, CMS took two different approaches in two similar situations. In one rule notice, the Secretary of Health and Human Services found that the proposed rule would have a “positive revenue impact” on a substantial number of small entities, and the agency conducted a certification analysis and certified the proposed rule as not having a significant economic impact.[45] In another rule notice, the Secretary found a “significant positive revenue impact,” and the agency conducted an initial regulatory flexibility analysis in lieu of certifying the proposed rule.[46] We had to consult with CMS officials to determine whether the agency intended to certify the rule.

In one SBA rule, the SBA Administrator stated that the agency did “not believe the impact would be significant.”[47] The rule did not mention the extent to which the rule may affect small entities or whether SBA was certifying the rule. We had to consult with SBA officials to determine that SBA had intended the language to signal that it was certifying the rule. This lack of clarity could pose a challenge for small entities, which may struggle to understand the agency’s intention.

Certifications Were Sometimes Inconsistent with the Office of Advocacy’s Guide and Other Key Practices

Agency certifications we reviewed sometimes were inconsistent with Advocacy’s guide and GAO and OMB key practices for rulemaking, according to our review of 37 certifications by CMS, EPA, and SBA.[48] Our analysis excluded the 10 certifications where agencies determined the proposed rule would not impact small entities and the eight certifications where agencies determined the proposed rule would have no economic impact.

Analyzing Impacts

The certifications we reviewed were sometimes inconsistent with Advocacy’s guide and other key practices for analyzing economic impacts and ensuring transparency.[49] Advocacy’s guide describes key elements that agencies should include in their analysis when certifying proposed rules. Including these elements helps agencies to obtain meaningful public comment regarding the rule’s impact on small entities. The elements include

· a description and estimate of the number of small entities affected by the rule;

· a description and estimate of the economic impacts on small entities, including costs, benefits, and indirect impacts; and

· criteria for determining “significant economic impact” and “substantial number,” such as percentage of revenue or percentage of small businesses affected.

However, the agencies’ certification analyses sometimes did not include these elements, as discussed below.

Description and estimate of small entities affected. Of the 37 certifications we reviewed, 35 described the small entities affected by the rule, while two EPA certifications did not.[50] Advocacy’s guide says that, at a minimum, agencies should describe the small entities affected by the rule. In addition, 31 of the 37 certifications provided a quantitative estimate of the number of small entities affected by the rule. One CMS proposed rule said that 75 percent of affected entities were small but did not mention how many entities in total were affected.[51] Three EPA certifications did not provide such estimates. According to EPA officials, these rules were intended to relieve regulatory burden, and the agency generally does not conduct further analysis on rules with beneficial impact. However, Advocacy’s guide states that agencies should examine all rules that may have a significant economic impact on small entities, regardless of whether that impact is positive or negative.

In the two other certifications, the agencies could not estimate the number of small entities that would be affected by the proposed rule because data were not available. For example, in one rule, SBA quantified the total number of lenders affected but could not determine the size of the lenders, as it did not collect financial statements from the parent companies.[52] In the second rule, EPA faced several data limitations, including the absence of a nationwide dataset of Clean Water Act certification reviews.[53] Instead, EPA conducted an in-depth qualitative analysis to assess the rule’s impact on small entities. Advocacy’s guide suggests options when quantitative data are unavailable, including conducting qualitative analysis or explaining the data limitations and requesting public comments.

Description and estimate of the impacts on small entities. Each of the three agencies conducted at least one certification analysis that did not describe or estimate impacts on small entities. Specifically, two of 37 certifications did not describe the cost impacts on small entities, and five of 37 did not include a quantitative estimate of the cost impact on small entities. For example, one EPA rule notice did not describe or quantify the economic impact because the rule relieved regulatory burden.[54]

CMS rules we reviewed often used the broader regulatory impact analysis to estimate economic impacts on small entities because the agency stated that most hospitals and other providers were small. RFA allows agencies to use these broader analyses to satisfy RFA requirements, provided they specifically address impacts on small entities.[55] However, we found that the extent to which CMS’s regulatory impact analyses focused on small entities varied across the rules we reviewed. For example:

· In one proposed rule, CMS estimated that 515 independent dialysis facilities and 378 hospital-based dialysis facilities were small. CMS estimated the economic impacts on these facilities in both the regulatory impact analysis and RFA sections.[56]

· In another proposed rule, CMS estimated that 77 of 479 health insurance issuers were small, but the regulatory impact analysis did not differentiate between impacts on small versus large insurers.[57]

· In a different proposed rule, CMS stated that most ambulatory surgical centers and community mental health centers were small entities. The regulatory impact analysis provided the total number of ambulatory surgical centers and community mental health centers, but did not specify how many of these entities were small. The analysis discussed the economic impacts of the rule but did not clarify whether these impacts would be felt by all affected entities, regardless of size.[58]

One of the objectives of the certification analysis is to encourage agencies to consider how a rule might affect small entities differently, such as whether the rule would place small entities at a competitive disadvantage.

Consideration of beneficial impacts. Of the 37 certifications, 11 from CMS and EPA did not examine the beneficial impacts on small entities.[59] This is contrary to Advocacy’s guide, which emphasizes consideration of both beneficial and adverse impacts in an analysis.[60] The guide states that the term “significant” is neutral with respect to whether the rule’s impact is beneficial or harmful to small entities, meaning agencies should consider beneficial impacts in their RFA analysis. The guide also states that analyzing beneficial impacts lends credibility to the agency’s choice of alternatives.

Consideration of indirect impacts. We found that 30 of 37 certifications by CMS, EPA, and SBA did not examine the proposed rule’s indirect impact on small entities.[61] Although RFA does not require it, Advocacy’s guide recommends that agencies consider indirect impacts on small entities.[62] For example, the guide states that an agency should examine potential effects on small entities that conduct business with entities directly regulated by the rule. In one proposed rule that did consider indirect impacts, EPA noted in supporting documents that proposed changes to the Clean Water Act’s water quality certification review process could delay federal licensing or permitting for small businesses’ infrastructure projects.[63]

Criteria for determining “significant economic impact” and “substantial number.” Each of the three agencies conducted at least one certification analysis that did not include the thresholds used to determine whether the rule impacted a substantial number of small entities or had a significant economic impact. Specifically, 27 of 37 certifications did not describe thresholds for determining a “substantial number” of small entities. Thirteen of 37 did not describe thresholds for “significant economic impact.”[64]

While RFA does not provide set criteria, Advocacy’s guide states that agencies should discuss the criteria used for determining that a rule does not significantly impact a substantial number of small entities. The guide suggests criteria to consider when determining “significant impact” or “substantial number.” For example, the rule’s impact could be significant if the cost of the proposed regulation eliminates more than 10 percent of the businesses’ profits or exceeds 1 percent of the entities’ gross revenue in a particular sector. The rule could affect a substantial number of small entities if it will have a significant economic impact on 25 percent of small entities in the sector.

Documenting Analysis

The certifications we reviewed were sometimes inconsistent with Advocacy’s guide or key practices from OMB and GAO for documenting an analysis. Advocacy’s guide recommends that certification analysis disclose assumptions and describe the data sources used in the economic analysis.[65] Similarly, OMB and GAO guidance emphasizes that agencies should ensure transparency by describing and justifying the analytical choices, assumptions, and data used.[66]

Certifications we reviewed generally included a justification for the certification. However, some did not disclose assumptions or describe data sources:

· Disclosing assumptions. Of the 37 certifications, four by CMS and EPA did not disclose the assumptions used in the analysis.[67]

· Describing data sources. Each of the three agencies conducted at least one certification analysis that did not disclose the data sources used for determining the number of small entities affected or the economic impacts. Specifically, seven of 37 rules did not identify the data sources used to determine the number of small entities affected by the rule.[68] Nine of 37 rules did not identify the data sources used to analyze economic impact.[69]

Ensuring Transparency

Guidance from Advocacy, OMB, and GAO emphasizes the importance of transparency in rulemaking to ensure that small entities and the public can comment effectively on the impacts of proposed rules. Advocacy’s guide stresses that analyses should enable small entities to easily identify relevant information.[70] As noted previously, guidance from both OMB and GAO similarly stresses that transparency requires agencies to include key elements in their analysis to help the public assess agency choices and understand the economic effects of the rule.[71]

However, we found that for the 37 certifications we reviewed, it was sometimes difficult to locate RFA information. For example:

· EPA provided a quantitative cost estimate for 13 rules, but for six of these, the estimates were found in supporting documents, not in the rule notice itself.[72] Readers were directed to the rule docket, which can contain hundreds of documents and be difficult to search. In addition, once readers located the correct document, they would still need to search for information specific to RFA.

· A CMS proposed rule stated that hospitals, ambulatory surgical centers, and community mental health centers would be considered small entities, but the economic impacts for each type of provider were located across different sections.[73] Therefore, to identify all the relevant information on small entities, readers would have to review the entire 342-page rule notice.

RFA requires certifications and the accompanying statements of factual basis to be published in the Federal Register concurrent with the notice of proposed rulemaking or final rule, but it does not prohibit agencies from including any supporting analysis in the rule docket.[74] However, Advocacy officials told us the certification analysis should be prominently placed in the RFA section of the rule notice for easy access by small entities. They also discourage agencies from referring readers to other documents for details and stress that the analysis should be clear enough for small entities to easily identify whether a rule applies to them.

Not including recommended elements—such as criteria for determining “significant” and “substantial” and data sources—could limit agencies’ ability to understand a rule’s impact on small entities and limit small entities’ ability to offer informed comments in response. In reviewing the selected agencies’ policies and procedures for RFA compliance, we found that they were missing some elements recommended by Advocacy, OMB, and GAO. We discuss the agencies’ policies and procedures in detail later in this report.

Selected Agencies Generally Met Requirements for RFA Analyses but Often Did Not Consider Indirect and Beneficial Impacts

The RFA-required analyses we reviewed for CMS, Energy, and SBA generally met statutory requirements.[75] However, they often did not include indirect and beneficial impacts on small entities, as recommended by Advocacy.[76] It was also difficult to find the required information for some rules.

RFA Analyses Generally Met Statutory Requirements

Initial Regulatory Flexibility Analysis

The 20 initial regulatory flexibility analyses we reviewed largely met RFA statutory requirements. For example, all 20 proposed rule notices described the need for the rule, the rule’s objectives and legal basis, and the type and number of affected small entities (see table 3). There were two requirements that several rules did not address: (1) describing the professional skills needed to comply with the rule and (2) identifying federal rules that duplicate, overlap, or conflict with the rule.

Table 3: RFA Requirements Included in 20 Initial Regulatory Flexibility Analyses from Selected Agencies, Fiscal Years 2022–2023

|

|

Rules with required element (out of 20) |

|

Description of need for the rule |

20 |

|

Statement of proposed rule’s objectives |

20 |

|

Statement of proposed rule’s legal basis |

20 |

|

Description of affected small entities |

20 |

|

Estimate of number of affected small entities |

20 |

|

Description of reporting, recordkeeping, and other compliance requirements |

19a |

|

Description of necessary professional skills |

15b |

|

Identification, to the extent practicable, of federal rules that may duplicate, overlap, or conflict with the proposed rule |

11 |

|

Description of alternatives to the proposed rule |

16c |

Source: GAO analysis of published rules and Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) requirements. | GAO‑25‑106950

Note: The selected agencies were the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Energy, and Small Business Administration. We reviewed final rules published during fiscal years 2022 and 2023. Some of the corresponding proposed rules may have been published prior to this time frame.

aFor the remaining rule, Energy officials said they updated their analysis in a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking to include compliance requirements. See 81 Fed. Reg. 39756 (June 17, 2016); 86 Fed. Reg. 47744 (Aug. 26, 2021).

bIn one rule notice, the agency said the rule did not have any compliance requirements.

cIn two rule notices, the agency said there were no alternatives considered. For one rule, Energy officials said they updated their analysis in a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking to include alternatives to the proposed rule. 81 Fed. Reg. 39756 (June 17, 2016); 86 Fed. Reg. 47744 (Aug. 26, 2021).

Final Regulatory Flexibility Analysis

Most of the 20 final regulatory flexibility analyses we reviewed met RFA statutory requirements. For example, all or nearly all of the analyses described the need for the rule, the rule’s objectives, and the affected small entities, and included the reasons for selecting the alternative adopted in the final rule (see table 4). Seven rule notices did not describe steps to minimize impact on small entities, including two in which the agency determined that the rule would have a positive economic impact on small entities and therefore did not seek to minimize the impact. In the other five notices, agencies generally considered alternatives and explained why they selected the alternative they chose. Five notices did not describe the professional skills needed to comply with the rule, including one that explained that because there were no compliance requirements, a description of professional skills was unnecessary.

Table 4: RFA Requirements Included in 20 Final Regulatory Flexibility Analyses from Selected Agencies, Fiscal Years 2022–2023

|

|

Rules with required element (out of 20) |

|

Description of need for the rule |

20 |

|

Description of rule’s objectives |

20 |

|

Description of issues raised in public comments on the initial regulatory flexibility analysis |

13a |

|

Response to any comments filed by the Small Business Administration’s Office of Advocacy |

n/ab |

|

Description of affected small entities |

20 |

|

Estimate of number of affected small entities |

19 |

|

Description of reporting, recordkeeping, and other compliance requirements |

20 |

|

Description of necessary professional skills |

15c |

|

Description of steps to minimize impact on small entities |

13d |

|

Description of reasons for selecting alternative adopted in final rule |

19e |

n/a = not applicable

Source: GAO analysis of published rules and Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) requirements. | GAO‑25‑106950

Note: The selected agencies were the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Energy, and Small Business Administration.

aIn three rule notices, the agency said it did not receive public comments on the initial regulatory flexibility analysis.

bOur analysis of Advocacy’s compliance reports found that Advocacy did not file comments on any of the rules in our review. Therefore, we consider all of the analyses to be compliant with this requirement.

cIn one rule notice, the agency said the rule had no compliance requirements.

dIn five rule notices, the agency generally considered alternatives and explained why it selected the alternative it chose. In two rule notices, the agency determined that the economic impacts were beneficial to small entities, so the agency would not seek to minimize the impact. Because the rule notices from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that met this requirement stated that most affected entities were small, the regulatory impact analysis considered alternatives that would minimize impact on all affected entities, not small entities specifically.

eIn one rule notice, the agency said there were no alternatives.

RFA Analyses Were Sometimes Inconsistent with Guidance and Key Practices

The 20 initial and final regulatory flexibility analyses we reviewed for CMS, Energy, and SBA sometimes did not contain elements recommended by Advocacy’s guide and key practices from OMB and GAO for conducting regulatory and economic analysis.[77]

Beneficial impacts. Three of the initial regulatory flexibility analyses by Energy and CMS did not describe beneficial impacts on small entities. As previously stated, Advocacy’s guide asserts that the term “significant” is neutral with respect to whether the rule’s impact is beneficial or harmful to small entities and therefore agencies should consider beneficial impacts in RFA analysis.

Indirect impacts. None of the 20 regulatory flexibility analyses we reviewed described indirect impacts on small entities. As previously stated, although RFA does not require agencies to describe indirect impacts, Advocacy’s guide encourages agencies to consider them.

Documentation. A few rules did not include data sources for estimating the number of affected entities or the compliance costs of the rule. For example, of the 19 final regulatory flexibility analyses that estimated the number of small entities subject to the rule, three CMS analyses did not include a data source. Similarly, two of the 13 final regulatory flexibility analyses estimating compliance costs did not include a data source. As previously noted, OMB and GAO guidance states that an economic analysis should clearly cite all data sources used.

Transparency. The clarity of information on economic impacts and affected small entities varied by agency. For example, CMS’s initial and final regulatory flexibility analysis often did not have clear information on small entity impacts. This was partly due to the variety of entities regulated in the Medicare payment system and the use of analyses from other sections of the rule notice to satisfy RFA requirements. In contrast, SBA and Energy’s analyses included all information on small entity impacts in the RFA section of the rule notice.

As stated previously, Advocacy officials recommend that agencies include the information relevant to small entities in the RFA section. Further, Advocacy’s guide states that the initial and final analyses should allow small entities to compare the impacts of regulatory alternatives on different sizes and types of entities affected by the rule to help them determine how alternatives will affect them. Additionally, OMB guidance states that results should be transparent and reproducible.

Not including recommended elements—such as analysis of indirect and beneficial impacts—could limit agencies’ and small entities’ ability to fully understand a rule’s impact. In reviewing the selected agencies’ policies and procedures for RFA compliance, we found that they were missing some elements recommended by Advocacy, OMB, and GAO. We discuss the agencies’ policies and procedures in the next section of this report.

Selected Agencies’ Policies and Procedures Do Not Include Recommended Elements from Advocacy and Other Key Practices

CMS, Energy, and EPA Have Developed Policies and Procedures for Complying with RFA Requirements, and SBA Has Not

Of the four agencies we selected for review, CMS, Energy, and EPA have policies and procedures specifically for complying with RFA posted publicly on their websites; SBA has not developed such policies and procedures.[78] Under Executive Order 13272, agencies are required to establish policies and procedures to promote compliance with RFA. This includes issuing written policies and procedures to ensure that agencies properly consider the potential impacts of rules during rulemaking. The order also states that agencies’ policies and procedures should be made publicly available, such as on the agency’s website.

CMS’s, Energy’s, and EPA’s policies and procedures for their rule writers restate RFA requirements when explaining how to complete the certification and regulatory flexibility analyses. Energy generally refers rule writers to Advocacy’s guide for these analyses instead of providing agency-specific guidance. CMS and EPA provide some additional detail on elements of RFA analyses that may require further interpretation. For example:

· CMS. CMS uses the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) policies and procedures, which highlight the need to consider compliance costs beyond just record-keeping and reporting in the initial regulatory flexibility analysis.[79] These may include expenses such as hiring additional personnel or revenue reductions. HHS also clearly defines criteria for determining “significant economic impact” and “substantial number of small entities” to support the certification analysis.[80]

· EPA. EPA’s policies and procedures for conducting regulatory flexibility analyses include guidance on describing and estimating the number of small entities impacted.[81] For example, the guidance emphasizes distinguishing among the small entities that are more and less susceptible to the proposed regulation’s economic impacts. In addition, EPA provides rule writers with factors to consider when setting thresholds for “significant” and “substantial” and provides examples of thresholds used in past analyses.[82]

In contrast, SBA has policies and procedures for conducting regulatory economic analysis but does not have separate policies and procedures specific to complying with RFA.[83] SBA officials told us they consider their regulatory economic analysis guidance to serve as their policies and procedures for RFA compliance. These more general policies and procedures include suggested thresholds for determining when to certify a rule, and they explain when regulatory flexibility analyses are required.[84]

However, these SBA policies and procedures do not describe the required and recommended elements of certification and regulatory flexibility analyses. They also do not explain how rule writers are expected to conduct such analyses. Without specific RFA policies and procedures for its rule writers, SBA is not adhering to Executive Order 13272 and cannot ensure consistent and complete compliance with RFA requirements in its rulemakings.

CMS, Energy, and EPA Policies and Procedures Do Not Include Certain Key Practices

Our review found that Energy’s policies and procedures for RFA compliance did not explain how rule writers should address certain statutory requirements and key elements recommended in Advocacy, OMB, and GAO guidance for conducting regulatory analyses (see table 5). We also found that CMS’s and EPA’s RFA policies did not incorporate some recommended elements.[85] This lack of specific policies and procedures to help rule writers implement requirements and recommended elements may have contributed to the weaknesses in analyses we identified earlier in this report. As previously stated, Advocacy’s guide helps agencies interpret and implement RFA requirements, OMB’s Circular A-4 provides information on benefit-cost analysis, and GAO’s guidance compiles the key methodological elements of a sound economic analysis.[86]

Table 5: Extent to Which Selected Agencies’ Policies and Procedures for Regulatory Flexibility Analysis Describe How to Address Statutory and Recommended Elements

|

|

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Servicesa |

Department of Energy |

Environmental Protection Agency |

||

|

Certification analysis elementb |

|||||

|

Estimate the number of affected small entities |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

||

|

Determine the size of the economic impacts |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

||

|

Describe why the number of entities or size of impacts justifies the certification |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

||

|

Initial regulatory flexibility analysis elementc |

|||||

|

Estimate the number of affected small entities |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Describe alternatives to the rule that minimize impacts on small entities |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

||

|

Describe reporting, recordkeeping, and other compliance requirements |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Final regulatory flexibility analysis elementc |

|||||

|

Estimate the number of affected small entities |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

||

|

Describe steps taken to minimize the rule’s impact on small entities |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

||

|

Describe reporting, recordkeeping, and other compliance requirements |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

||

|

Recommended elementsd |

|||||

|

Analyze indirect impacts |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

||

|

Analyze beneficial impacts |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

||

|

Document data sources |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

||

|

Ensure transparency |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

||

Legend: ✓ = yes; ✗ = no

Source: GAO analysis of agency policies and procedures. | GAO‑25‑106950

aThe Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services uses the Department of Health and Human Services’ policies and procedures.

bThese are elements that the Small Business Administration’s Office of Advocacy recommends including in the statement of factual basis that supports the certification.

cThese are statutory requirements.

dThese are recommended elements and key practices from Advocacy, Office of Management and Budget, and GAO guidance.

Examples of recommended practices for regulatory analysis that are not incorporated in agency RFA policies and procedures include the following:

· Certification analysis. Energy’s RFA policies and procedures do not explain how their rule writers should address key elements that Advocacy recommends including in the statement of factual basis supporting certification, such as how to estimate the number of affected entities. Energy’s policies and procedures do not provide thresholds to guide rule writers in defining “substantial” number and “significant” economic impact, although they do provide some factors from Advocacy’s guide to consider when making this assessment.

· Initial and final regulatory flexibility analysis. Energy does not have RFA policies and procedures for how its rule writers should address required elements of the final regulatory flexibility analysis, such as the steps taken by the agency to minimize the significant economic impact on small entities.

· Analyzing indirect and beneficial impacts. None of the three agencies—CMS, Energy, or EPA—has RFA policies and procedures that address analyzing indirect and beneficial impacts on small entities.[87]

· Documenting data sources. Energy does not have RFA policies and procedures for disclosing data sources used in analyses.[88]

· Ensuring transparency. None of the three agencies has policies and procedures for ensuring that RFA analyses clearly explain which small entities will be affected and what the rule’s impacts on them will be.[89] Moreover, CMS and Energy do not specify where this information should be located in the rule so that small entities can easily identify it. EPA has policies and procedures for where RFA-related information should be located in the rule notice, but it allows reference to additional details in the docket.

Furthermore, CMS’s, EPA’s, and Energy’s policies were published in 2003, 2006, and 2003, respectively—well before Advocacy updated its guide in 2012 and 2017.[90] According to Advocacy officials, a proper interpretation of Executive Order 13272 would lead agencies to update their policies to reflect changes in RFA that affect compliance, as well as advancements in technology, innovation, and the evolving concerns of small businesses. However, officials at the three agencies stated that they have no plans to update their policies and procedures.

Fully incorporating Advocacy, OMB, and GAO guidance into their policies and procedures would enhance the ability of CMS, Energy, and EPA to thoroughly analyze a rule’s economic impact on small entities and help these entities better understand how they will be affected.

Advocacy Has Not Provided RFA Training to Agencies Throughout Government, and Its Performance Goal Does Not Align with This Objective

Many Agencies Have Not Received RFA Training, and Advocacy Does Not Have Policies and Procedures for Its Training Program

Advocacy is mandated under Executive Order 13272 to provide RFA compliance training to agencies.[91] Advocacy offers agencies training that covers the various steps of applying RFA requirements, such as completing the regulatory flexibility analyses, and that can be tailored to an agency’s specific needs. Advocacy officials said that during the COVID-19 pandemic, they shifted from in-person to virtual training. They stated that Advocacy currently offers hybrid training that can be attended in-person or virtually. According to officials, Advocacy is updating its training program based on feedback it has received to include more examples.[92] To monitor their training activities, Advocacy staff stated that they track the date and location of each training session, which agencies are present, and how many staff attend.

Advocacy’s most recent annual report states that it has offered RFA compliance training to all rulemaking agencies since it began its training program in 2003.[93] However, officials said they do not maintain a comprehensive list of all rulemaking agencies, making it difficult to compare against their list of agencies trained. We used the list of rulemaking agencies compiled by the Administrative Conference of the United States and compared it with Advocacy’s list of trained agencies.[94]

Our analysis indicates significant gaps in Advocacy’s training efforts:

· Many agencies have not been trained since 2003. We found that as of fiscal year 2023, Advocacy had not provided training to 87 of the 181 rulemaking agencies.[95] Advocacy officials noted that the majority of agencies that had not received training do not issue regulations with which small entities must comply. However, Advocacy does not maintain a comprehensive list of rulemaking agencies and therefore cannot accurately determine which agencies issue regulations that affect small entities and which may need training.

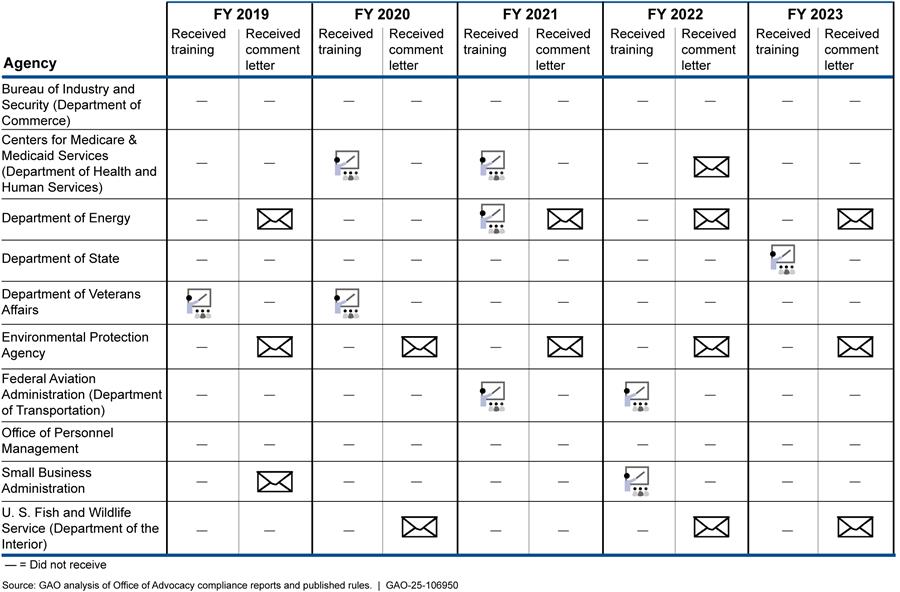

· Agencies may go an extended period without training. Even if agencies have received training, many have not been trained in recent years, including some that have published many significant rules. Our analysis found that from fiscal years 2019 through 2023, 150 of the 181 rulemaking agencies did not receive training. Among the 10 agencies that published the greatest numbers of significant rules in fiscal years 2022 and 2023, four did not receive training from fiscal years 2019 through 2023: EPA, the Bureau of Industry and Security, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Office of Personnel Management (see fig. 3). Advocacy officials noted that Executive Order 13272 does not require agencies to be trained at a certain frequency.

Figure 3: Office of Advocacy Comment Letters and Training Received by 10 Agencies That Published the Greatest Numbers of Significant Rules in Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023

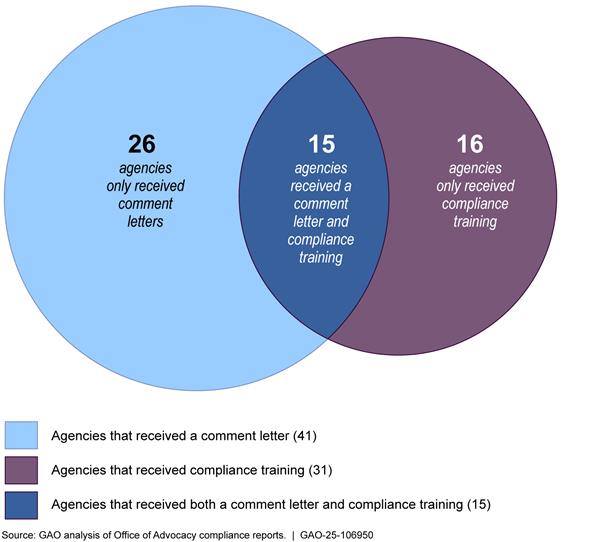

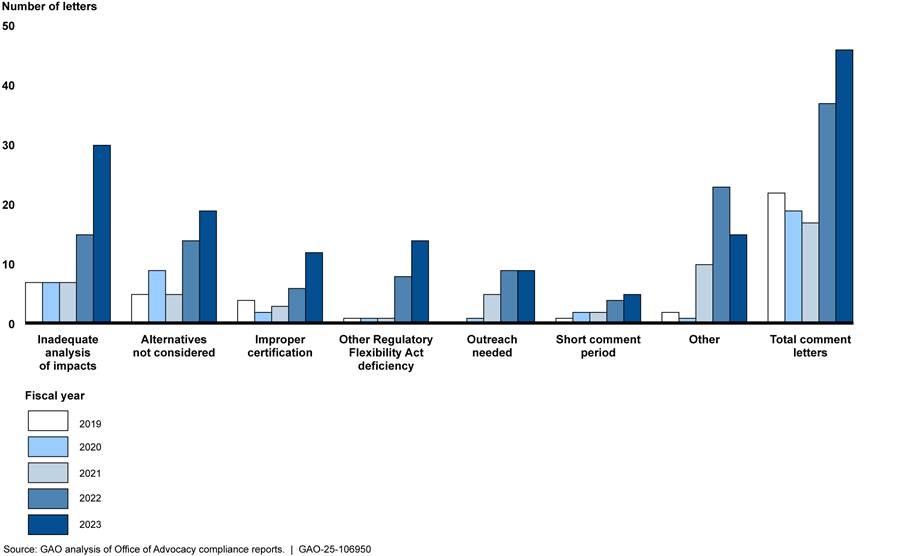

· Training efforts may not target agencies that need training most. Advocacy sends comment letters to agencies with identified RFA compliance issues, but there does not appear to be a relationship between these agencies and those receiving training.[96] From fiscal years 2019 through 2023, Advocacy identified 41 agencies with deficiencies in their RFA analyses, but 26 of these agencies did not receive any training during this period (see fig. 4). Some agencies have received multiple letters across several years without receiving training. Notably, EPA received 35 comment letters from the Office of Advocacy on RFA compliance during this period.[97] (See app. IV for further information on agencies that received training or comment letters from Advocacy.)

Figure 4: Agencies That Received Comment Letters or Compliance Training from the Office of Advocacy Related to the Regulatory Flexibility Act, Fiscal Years 2019–2023

Advocacy officials said they rely on informal methods to identify agencies that need training. They said their attorneys monitor staff turnover and gauge agencies’ understanding of RFA during the interagency review process.[98] If attorneys believe training is necessary, they will extend an offer. However, Advocacy does not have formal procedures to track staff turnover or document agencies that may need additional training.

Federal internal control standards state that management should implement control activities through policies.[99] Policies may be further defined through procedures, which may include, for example, the timing of a control activity or any follow-up corrective actions when deficiencies are identified.

Advocacy does not have formal policies and procedures for implementing its mandate to provide RFA training to agencies. For example, Advocacy does not have procedures for identifying all agencies involved in rulemaking. In addition, it has no established policies on how regularly agencies should receive training. Further, Advocacy does not have formal procedures for prioritizing agencies that may need training due to identified issues.

This informal approach to agency training may lead to gaps in RFA compliance. According to Advocacy’s 2023 annual compliance report, a lack of training can result in inadequate analysis of impacts on small entities and increased litigation risk.[100] Developing formal policies and procedures for providing RFA compliance training would enable Advocacy to systematically track training to rulemaking agencies and help ensure these agencies receive regular and refresher training as needed. This would help Advocacy provide training throughout government and better position agencies to comply with RFA.

Advocacy’s Performance Goal Does Not Promote Training Throughout Government

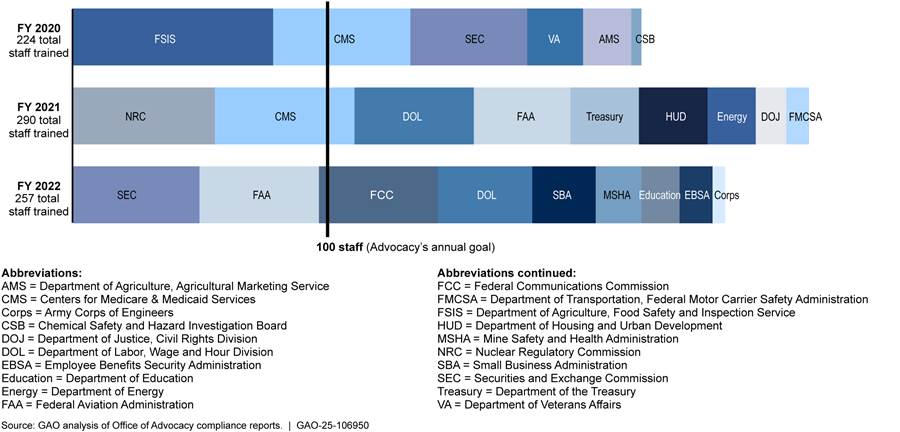

To address its mandate under Executive Order 13272, Advocacy has a strategic objective of providing RFA compliance training to rulemaking officials throughout government. To achieve this objective, Advocacy set a performance goal to train at least 100 officials each fiscal year.[101] Advocacy officials stated that they have met this goal every year since the training program began in 2003. Our review of Advocacy’s RFA compliance reports for fiscal years 2019 through 2023 confirmed this, showing that Advocacy trained over 100 officials each year through about eight to 10 trainings per fiscal year.

However, meeting this goal does not necessarily indicate comprehensive coverage across multiple agencies, as a single agency may send a large number of staff to a training session. For example, during each of the fiscal years 2020–2022, certain individual agencies brought at least 50 staff members to a single training, accounting for half of Advocacy’s annual goal.[102] As shown in figure 5, Advocacy could have met its goal by training as few as two agencies in some years.

Figure 5: Number of Staff Attending Office of Advocacy Compliance Trainings, by Agency, Fiscal Years 2020–2022

Because Advocacy’s performance goal focuses on the total number of staff trained, it does not measure the extent to which training is comprehensive across government agencies. As previously discussed, no staff from 150 rulemaking agencies received training in the last 5 years. At the same time, eight of the 31 agencies that did receive training were trained multiple times, with some receiving training 2 years in a row across the 5-year period (see app. IV for more information).

In our previous work, we identified key practices for agency performance management activities.[103] One such practice is developing performance goals that link to the agency’s strategic goals and objectives and that address important dimensions of program performance. Advocacy’s performance goal of training 100 officials a year is not clearly aligned with its strategic objective of training rulemaking officials throughout government because those officials could be concentrated at a few agencies. By developing a performance goal that better links to its strategic objective, Advocacy could better ensure that it is providing RFA training across rulemaking agencies and complying with Executive Order 13272.

Conclusions

The Regulatory Flexibility Act plays an important role in ensuring that federal agencies consider and seek to minimize the impact of their regulations on small businesses. However, we identified opportunities for selected agencies to enhance implementation in the following areas:

· Establishing policies. SBA largely complied with RFA statutory requirements, but it has not established specific policies and procedures for implementing RFA. As a result, it is not adhering to Executive Order 13272 and cannot ensure consistent and thorough adherence to RFA requirements in its rulemakings.

· Aligning policies with key practices. CMS, Energy, and EPA generally complied with RFA statutory requirements, but we identified instances where their analyses did not align with Advocacy’s guide and other key practices for rulemaking. By more fully incorporating Advocacy, OMB, and GAO guidance—and instructions for addressing statutory requirements, in the case of Energy—into their policies and procedures, the agencies could more consistently and effectively meet RFA objectives.

· Ensuring comprehensive training throughout government. SBA’s Office of Advocacy does not have formal policies or procedures for providing RFA compliance training. As a result, it cannot effectively identify agencies that are most in need of training or have not received it for an extended period. Establishing formal policies and procedures for such training would better ensure that all agencies receive regular and refresher training as needed. Advocacy could further ensure comprehensive training by developing a performance goal more directly tied to its strategic objective of training officials throughout the government.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of six recommendations, including one to SBA, one to HHS, one to Energy, one to EPA, and two to SBA’s Office of Advocacy:

The Administrator of SBA should develop and implement policies and procedures for complying with the Regulatory Flexibility Act. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should revise HHS’s Regulatory Flexibility Act policies and procedures to more fully incorporate elements recommended by the Office of Advocacy, OMB, and GAO for conducting certification and regulatory flexibility analyses, such as considering beneficial and indirect impacts on small entities. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Energy should revise Energy’s Regulatory Flexibility Act policies and procedures to incorporate statutory requirements and elements recommended by the Office of Advocacy, OMB, and GAO for conducting certification and regulatory flexibility analyses, such as considering beneficial and indirect impacts on small entities. (Recommendation 3)

The Administrator of EPA should revise EPA’s Regulatory Flexibility Act policies and procedures to more fully incorporate elements recommended by the Office of Advocacy, OMB, and GAO for conducting certification and regulatory flexibility analyses, such as considering beneficial and indirect impacts on small entities. (Recommendation 4)

The Chief Counsel of the Office of Advocacy should develop and implement policies and procedures for providing training to agencies on Regulatory Flexibility Act compliance, including mechanisms to identify agencies most in need of training and agencies that have not received it for an extended period. (Recommendation 5)

The Chief Counsel of the Office of Advocacy should develop one or more performance goals that more clearly link with its strategic objective of training rulemaking officials throughout the government. (Recommendation 6)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to Energy, EPA, HHS, SBA, and SBA’s Office of Advocacy for review and comment. Each agency provided written comments, which are reprinted in appendixes V–X. Energy and EPA provided additional comments via email, as well as technical comments that we incorporated as appropriate.

Energy. Energy neither agreed nor disagreed with our recommendation that it update its policies and procedures, stating it would review the requirements and recommendations identified in our report and assess whether additional guidance would be beneficial.

In its letter and in an email from an Audit Resolution Specialist, Energy provided additional comments on our findings:

· Energy stated in its letter that our report did not correctly characterize the department’s guidance relating to the consideration of small entities. In its emailed comments, which provided more clarification, Energy stated that its policies and procedures explicitly address RFA statutory requirements and provide guidance for analyzing the elements of an initial regulatory flexibility analysis, including using SBA’s size standards to determine the small entities affected by the proposed rule. Further, Energy stated that its policies and procedures address all the other statutory and recommended elements we identified. As we stated in the report, Energy’s policies and procedures restate RFA requirements for the certification and regulatory flexibility analyses. We added language to the report to clarify that policies and procedures should assist rule writers in implementing requirements, not just restate them.

We reevaluated Energy’s policies and procedures for conducting initial regulatory flexibility analyses and determined they provide some information that can help rule writers estimate the number of affected small entities and describe compliance requirements. We did not, however, find additional evidence of policies and procedures that help rule writers implement the other statutory requirements and recommended elements we identify in the report, such as conducting final regulatory flexibility analyses or analyzing indirect impacts. We maintain that incorporating Advocacy, OMB, and GAO guidance into its policies and procedures would enhance Energy’s ability to thoroughly analyze a rule’s economic impact on small entities.

· Energy stated in its letter and emailed comments that our report inaccurately characterized the RFA analysis for specific rules and the department’s process for identifying benefits to small entities. While we do not believe our characterization was inaccurate, we added additional context about analysis that Energy cited and conducted. In addition, Energy stated in its emailed comments that while the initial and final regulatory flexibility analyses of certain rules did not call out beneficial impacts specific to small entities, they did discuss beneficial impacts in general. However, the focus of RFA is beneficial impacts to small entities specifically. We reviewed the evidence Energy cited and revised the report accordingly where we determined that there was some consideration of benefits for small entities.

EPA. EPA neither agreed nor disagreed with our recommendation that it update its policies and procedures, stating that it plans to update its RFA guidance when resources allow. As part of that update, EPA said it would consider guidance from other agencies and expects to focus on RFA-related analyses addressing statutory requirements.

In its letter and via an email from an Office of Policy GAO Liaison, EPA provided additional comments on our findings:

· EPA stated that analytical elements we identified as absent from the agency’s RFA analyses were included elsewhere in the broader regulatory analyses. However, as noted in our methodology, we reviewed the entire rule notice and supporting documentation for information relevant to small entities. We described an element as absent if the element was not mentioned in the rule’s RFA section, the broader regulatory analysis, or the supporting documentation.

· EPA said it interprets “significant economic impact” to refer to adverse economic impacts, not beneficial impacts, and “substantial number of small entities” to refer only to small entities directly regulated by the proposed rule. It said Advocacy’s guide notes court decisions that support this interpretation.[104] Thus, EPA stated that RFA does not require a certification analysis for rules with significant beneficial or indirect impacts on small entities.

We acknowledge differing agency interpretations in the report, but Advocacy’s guide maintains that agencies can analyze beneficial impacts with minimal effort. While RFA does not require indirect impact analysis, Advocacy considers it good public policy to do so. As our recommendation states, we believe EPA should revise its policies and procedures to be consistent with elements in Advocacy’s guide.

· EPA questioned our use of OMB and GAO guidance when assessing RFA analysis. As noted in our report, while not specific to RFA, both reinforce principles in Advocacy’s guide, such as the importance of documentation and transparency. We believe using the OMB and GAO guidance in conjunction with Advocacy’s guide is appropriate for evaluating how agencies consider impacts on small entities in rulemaking.