MARITIME CARGO SECURITY

Additional Efforts Needed to Assess the Effectiveness of DHS’s Approach

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106953. For more information, contact Heather MacLeod at (202) 512-8777 or macleodh@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106953, a report to congressional committees

Additional Efforts Needed to Assess the Effectiveness of DHS's Approach

Why GAO Did This Study

The U.S. economy depends on the quick and efficient flow of millions of tons of cargo each day throughout the global supply chain. However, U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo shipments are vulnerable to criminal activity or terrorist attacks that could disrupt operations and limit global economic growth and productivity.

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for GAO to assess federal efforts to secure U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo from national security-related risks. This report addresses (1) how DHS secures these vessels and cargo from supply chain risks, (2) the extent that DHS used selected leading collaboration practices, and (3) the extent that DHS assessed its approach.

GAO reviewed agency policies, procedures, and collaboration efforts and government-wide strategy documents, and assessed DHS collaboration efforts against five relevant leading practices identified in prior GAO work. GAO also interviewed Coast Guard and CBP officials from 16 field locations at a non-generalizable sample of eight U.S. seaports selected for varying volumes of cargo and diversity of geographic regions.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that the Coast Guard, with sector partners, develop objective, measurable, and quantifiable performance goals and measures and use this performance information to assess progress towards the goals and effectiveness of the layered approach to securing vessels and maritime cargo on an ongoing basis. DHS concurred with our recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) uses a layered maritime security approach to identify potentially high-risk, U.S.-bound vessels and cargo shipments. Within DHS, the U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) are the lead agencies that manage programs that screen, target, and examine these vessels and shipments. Both agencies conduct these activities before vessels and cargo depart foreign seaports, in transit, and upon their arrival at U.S. seaports. For example, both agencies have intelligence programs to screen and target these vessels and cargo across the supply chain.

GAO found that Coast Guard and CBP at the 16 selected field units generally followed five selected leading practices for interagency collaboration in their efforts to secure U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo from national security risks. For example, officials from all selected field units we interviewed reported leveraging resources and information to collaborate with their counterpart. Specifically, Coast Guard officials at one location said they leveraged the staff of other federal agencies, such as CBP, to help with vessel boardings due to their own staffing challenges.

GAO also found that DHS had not fully assessed the effectiveness of its approach for securing vessels and maritime cargo. The Coast Guard and Transportation Systems Sector partners—including federal agencies, state, local, and tribal governments, and nongovernmental organizations—identified a strategic goal with activities relevant to securing vessels and maritime cargo. However, they have not developed objective, measurable, and quantifiable performance goals and performance measures to fully assess progress towards this goal. Doing so would better position the agency and its partners to regularly use performance information to assess the effectiveness of their approach and help inform decisions, such as determining how to best allocate resources.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CBP |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

|

CSI |

Container Security Initiative |

|

DHS |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security |

|

ICE |

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

|

NTC |

National Targeting Center |

|

ReCoM |

Regional Coordinating Mechanism |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 21, 2025

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The U.S. economy depends on the quick and efficient flow of millions of tons of cargo each day throughout the global supply chain. According to the Department of Transportation, the majority of U.S. cargo arrives by ocean vessel, and in 2023, ocean vessels continued to transport the majority of U.S.-international cargo, valued at $2.1 trillion.[1]

However, U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo shipments can present significant security concerns, as individuals and criminal organizations have exploited vulnerabilities in the maritime supply chain by using cargo to smuggle narcotics, stowaways, and other contraband.[2] For example, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the U.S. Coast Guard seized 20,000 pounds of dried khat, a controlled substance, from a shipping container at the Port of Seattle in 2022. Further, there is a risk that terrorists could use maritime cargo shipments to transport a weapon of mass destruction or other terrorist contraband into the U.S. Such criminal activity or terrorist attacks using maritime cargo shipments could cause disruptions to the supply chain and limit global economic growth and productivity.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is the primary department responsible for securing U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo, and for protecting the U.S. from vessel-related national security risks or threats posed, such as risks posed by terrorism or weapons of mass destruction. We have reported previously on various aspects of these DHS programs and efforts related to maritime security—including targeting and examining high-risk cargo and vessels—such as Coast Guard’s International Port Security Program and CBP’s Container Security Initiative and Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism.[3] We have made recommendations to enhance the effectiveness of these programs, as discussed throughout the report.

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for GAO to assess federal efforts to secure U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo from national security related risks.[4] This report addresses:

1. How DHS secures U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo from supply chain risks;

2. The extent to which DHS used selected leading collaboration practices when securing U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo; and

3. The extent to which DHS has assessed the effectiveness of its approach for securing U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo.

To address our first objective, we focused on Coast Guard and CBP programs for securing U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo from risks from their departure from a foreign seaport to their arrival at a U.S. seaport.[5] Specifically, we reviewed Coast Guard and CBP policies, procedures, and other relevant documentation to determine the relevant authorities, and program roles and responsibilities for each identified program or office. These documents included Coast Guard’s Marine Safety: Port State Control (2021) and CBP’s Seaport Cargo Processing Guidelines (2022).[6] We also conducted interviews with relevant DHS officials about the primary headquarters and field programs and offices with responsibility for securing vessels and maritime cargo from supply chain risks.

To address our second objective, we assessed DHS’s collaborative efforts against five of eight leading practices for collaboration: (1) define common outcomes; (2) clarify roles and responsibilities; (3) include relevant participants; (4) leverage resources and information; and (5) develop and update written guidance and agreements.[7] Specifically, we reviewed DHS, Coast Guard, and CBP documentation to identify the use of selected leading collaboration practices in written guidance. This documentation included national- and field-level policies and procedures—such as local Regional Coordinating Mechanism (ReCoM) charters.[8] These documents can include information that describes methods and mechanisms for interagency collaboration and information sharing, or that is designed to guide or set goals for collaboration on securing vessels and maritime cargo.[9]

Further, to assess DHS’s collaborative efforts, we interviewed or received written responses from Coast Guard and CBP officials representing 16 field units located across a non-generalizable selection of eight U.S. seaports.[10] We selected the sample of eight U.S. seaports where Coast Guard and CBP field units are located and that included varying volumes of cargo and a diversity of geographic regions—the Great Lakes, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, and Gulf of Mexico—to obtain a range of perspectives.

While the information we obtained from Coast Guard and CBP officials at selected U.S. seaports are not generalizable to all seaports and field units, it provided valuable insights into their policies, procedures, and collaboration practices. We conducted site visits to the Port of Los Angeles-Long Beach, California; and the Port of Miami, Florida to tour Coast Guard and CBP facilities, observe their operations, and interview relevant officials regarding their collaboration. We chose these seaport locations due to their large port size and high volume of cargo, among other factors. We also visited CBP’s National Targeting Center in Sterling, Virginia to tour the facility and observe Coast Guard and CBP joint cargo- and vessel-targeting operations using various systems, including CBP’s Automated Targeting System.[11] Additional information on this analysis and the seaport locations of officials we interviewed is included in appendix I.

To address our third objective, we reviewed federal government-wide strategy documents, such as the 2015 Transportation Systems Sector-Specific Plan and the 2018 Transportation Systems Sector Activities Progress Report.[12] We did so to determine DHS and the Coast Guard’s goals to support the transportation sector and efforts to assess its approach for securing U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo. To determine the Coast Guard’s progress on achieving the goals laid out in this plan and any associated performance measures, we interviewed officials from Coast Guard’s Office of Port and Facility Compliance, the office responsible for ensuring the goals are completed.

To determine the extent to which the Coast Guard has assessed DHS’s approach for securing U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo, we compared the actions the Coast Guard took against the goals laid out in the 2015 sector-specific plan.[13] We also assessed the extent to which the Coast Guard’s efforts to assess the effectiveness of its layered maritime security approach against leading practices for performance management, including selected key attributes for such goals and measures identified in our prior work.[14] We further evaluated the Coast Guard’s efforts for assessing its layered approach using the National Infrastructure Protection Plan’s Critical Infrastructure Risk Management Framework.[15]

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Coast Guard and CBP Roles and Responsibilities

Within DHS, the Coast Guard and CBP are the primary components responsible for securing U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo. For example:

· The Coast Guard has primary responsibility for safeguarding the maritime interests of the U.S. The Coast Guard is also responsible for safety and security of vessels and maritime facilities. In this capacity, among other efforts, the Coast Guard conducts port facility and commercial vessel inspections, leads the coordination of maritime information sharing efforts, and promotes domain awareness in the maritime environment.

· CBP is the lead federal agency responsible for ensuring cargo security and reducing the vulnerabilities associated with the global supply chain. This involves identifying and mitigating risks associated with maritime cargo shipments that pose a threat to national security, such as weapons of mass destruction and contraband (such as illegal weapons and narcotics). See figure 1 for an example of a vessel carrying containerized cargo.

Further, the President issued Presidential Policy Directive 21 in 2013, which established national policy on critical infrastructure security and resilience for the nation’s 16 critical infrastructure sectors and outlined federal roles and responsibilities for protecting them.[16] This directive assigned roles and responsibilities to DHS as one of two departments responsible for the Transportation Systems Sector.[17]

To implement the directive, DHS issued a revised 2013 National Infrastructure Protection Plan (the National Plan) and, later, the 2015 Transportation Systems Sector-Specific Plan to guide and integrate efforts to secure and strengthen the resilience of transportation infrastructure.[18] The sector-specific plan tailors the strategic guidance provided in the National Plan to the unique operating conditions and risk landscape of the nation’s varied transportation systems. Accordingly, the sector-specific plan comprises activities in support of four subsectors: aviation, maritime, surface, and postal and shipping. Within DHS, the Coast Guard is assigned as the executive agency responsible for carrying out this work for maritime subsector activities.[19]

The 2015 Transportation Systems Sector-Specific Plan also describes how the sector contributes to the overall security and resilience of the nation’s critical infrastructure and lays out goals to do so.[20] This includes one strategic goal related to maritime security and supply chain activities: enhance the all-hazards preparedness and resilience of the global transportation system to safeguard U.S. national interests. To achieve this goal, the sector-specific plan lays out five maritime activities.[21]

Vessel and Maritime Cargo Information Required to be Submitted to DHS Prior to Arrival

Coast Guard regulations require that, no later than 96 hours prior to a vessel’s entry into the U.S., the vessel’s owner or agent is required to submit a vessel Notice of Arrival to the Coast Guard’s National Vessel Movement Center. This notice is to contain information that the Coast Guard states it can use to determine whether a vessel is of interest or possibly high-risk.[22] For example, each Notice of Arrival must include the name of the vessel, the country the vessel is registered to, the names and dates of the last five foreign ports or places the vessel visited, and a general description of cargo.[23] Additionally, the notice must indicate if the vessel is carrying certain dangerous cargo—for example, explosives or poisonous materials—and the name and amount of such cargo carried, among other things.[24]

In addition, CBP regulations generally require that the vessel’s owner or agent submit electronic crew and passenger arrival lists to assess their risk no later than 96 hours prior to a vessel’s entry into the U.S.[25] Each arrival list must contain information such as the individual’s full name, date of birth, citizenship, status on board the vessel, and the vessel name and flag country. The Coast Guard transmits the Notice of Arrival information to CBP’s Advance Passenger Information System, which provides information about vessels on the required fields to be used in the arrival lists. Further, pursuant to the Trade Act of 2002, CBP must receive advance electronic cargo information 24 hours prior to the vessel loading in a foreign port.[26] According to CBP, this data enables CBP to perform automated targeting and risk analysis of cargo arriving in the U.S.

In January 2009, CBP implemented the Importer Security Filing and Additional Carrier Requirements, generally referred to as the Importer Security Filing rule.[27] CBP generally requires importers and vessel carriers to electronically submit advance cargo information, such as the country of origin, to CBP no later than 24 hours before cargo is loaded onto U.S.-bound vessels at foreign ports. Importer Security Filing importers are responsible for submitting the Importer Security Filing and required data elements for this filing differ depending on the cargo’s destination.[28] According to CBP, collection of the additional cargo information is intended to improve CBP’s ability to identify high-risk shipments and prevent the transportation of terrorist weapons and other contraband into the U.S.

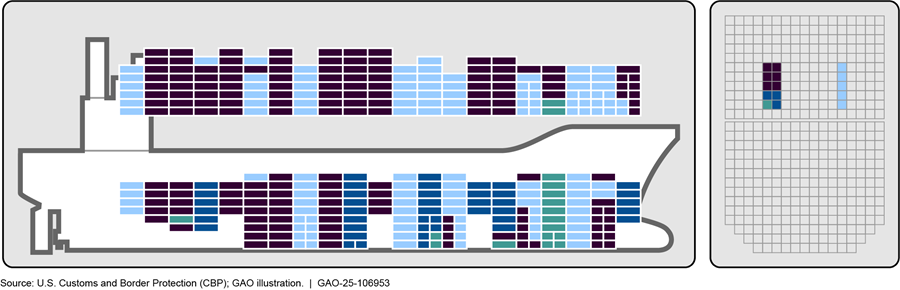

Additionally, for vessels transporting containerized cargo to the United States, CBP requires vessel carriers to submit vessel stow plans and container status messages if the carrier creates or collects a container status message in its equipment tracking system report that event.[29] Specifically, carriers create container status messages for events that are required to be reported, such as loading and discharging of vessels; as well as the status of containers, such as if they are empty or full.[30] A carrier is to submit container status messages to CBP no later than 24 hours after the message is entered into the carrier’s equipment tracking system.[31] Similarly, generally no later than 48 hours after departure from the last foreign port, vessel carriers transporting containers are to submit vessel stow plans to CBP.[32] Vessel stow plans are required to include the vessel’s name, the vessel operator, voyage number, the container operator, the stow position of each container on a vessel, hazardous material code (if applicable), and the port of discharge.[33] See figure 2 for an example of a vessel stow plan.

Note: The image above is a portion of information available through the vessel stow plan. The left portion of this figure provides CBP with a general idea of the total number, location, and origin of the containers (colors designate containers loaded at the same ports). The right portion of this figure represents a cross section of the vessel and shows the layout of containers for each level on the vessel. Other information accessible to CBP through the vessel stow plan includes, for example, last foreign port and departure date, destination port, and number of containers. CBP can also view information about containers individually or in groups, as well as information about all unmanifested containers or containers loaded at the same foreign port.

Leading Collaboration Practices

In prior work, we have identified eight leading practices to help agencies collaborate and coordinate their efforts.[34] For example, we found that effective interagency collaboration (among two or more federal entities) benefits from practices such as defining common outcomes and having clear roles and responsibilities. We also identified key considerations for collaborating entities to use when incorporating the practices. For example, to define common outcomes, participants in a collaboration can consider developing short- and long-term goals or outcomes. We selected five of the eight leading collaboration practices as relevant to the Coast Guard and CBP activities to secure U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo (see table 1).

Table 1: Selected Leading Collaboration Practices and Examples of Key Considerations Identified in Prior GAO Work

|

Leading practice |

Examples of key considerations |

|

Define common outcomes |

· Have the crosscutting challenges or opportunities been identified? · Have the short- and long-term outcomes been clearly defined? |

|

Clarify roles and responsibilities |

· Have the roles and responsibilities of the participants been clarified? |

|

Include relevant participants |

· Have all relevant participants been included? · Do the participants have the appropriate knowledge, skills, and abilities to contribute? |

|

Leverage resources and information |

· How will the collaboration be resourced through staffing? · Are methods, tools, or technologies to share relevant data and information being used? |

|

Develop and update written guidance and agreements |

· If appropriate, have agreements regarding the collaboration been documented? · Have ways to continually update or monitor written agreements been developed? |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑106953

DHS Secures Vessels and Cargo from Risks at Multiple Points in the Maritime Supply Chain

DHS uses a layered approach of interrelated programs to help secure the maritime supply chain without disrupting the flow of commerce into the U.S. Specifically, the Coast Guard and CBP manage several programs that screen, target, and examine potentially high-risk vessels and cargo at multiple points in the supply chain, such as before they depart foreign seaports, during their transit, and upon their arrival at U.S. seaports.

Coast Guard and CBP Programs Assess Risks of Terrorism Before Vessels and Cargo Depart Foreign Seaports

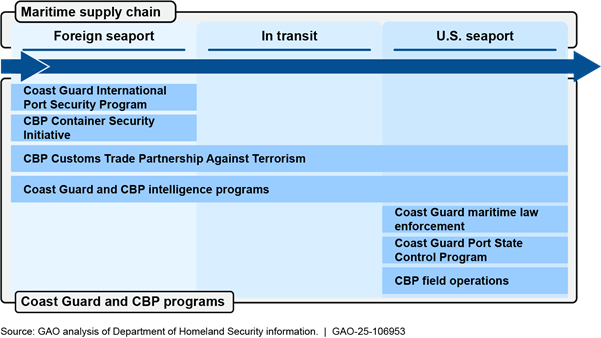

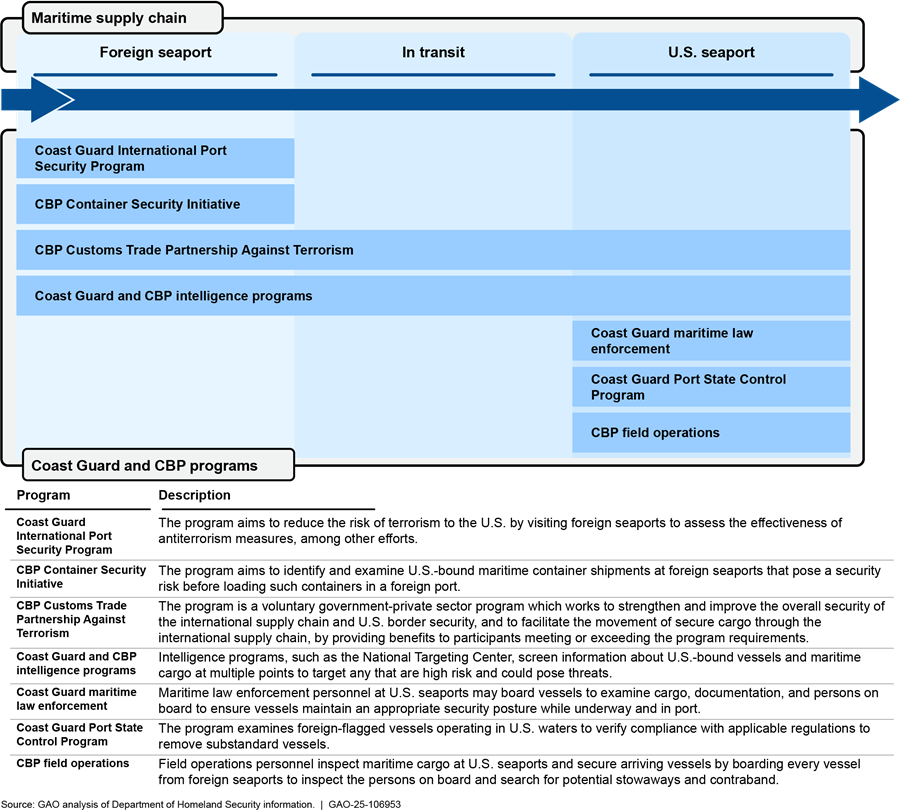

Through voluntary programs at foreign seaports, Coast Guard and CBP personnel assess seaport and vessel security measures and prescreen high-risk cargo to mitigate the risk of criminal activity and terrorism before vessels and maritime cargo depart from foreign seaports to arrive at U.S. seaports. Figure 3 shows key DHS security programs at various points in the maritime supply chain.

Figure 3: U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Programs to Secure U.S.-Bound Vessels and Cargo in the Maritime Supply Chain

Coast Guard International Port Security Program. The International Port Security Program aims to reduce the risk of terrorism to the U.S. and its marine transportation system by providing the Coast Guard with awareness of the global port security environment. The program carries out this work through efforts such as assessing the effectiveness of antiterrorism measures in foreign seaports against international standards and identifying ways for foreign governments and seaport facility operators to more fully implement these standards and measures.[35] The Coast Guard uses this program as an early warning indicator on potential risks posed to U.S. seaports by vessels transiting from foreign seaports that are not implementing effective antiterrorism measures.[36]

To assess the effectiveness of antiterrorism measures, program personnel visit the foreign seaports of countries that voluntarily participate in the program to observe physical security conditions, such as the seaport’s control of cargo and other material aboard vessels arriving at facilities.[37] Based on these observations, program officials determine whether the foreign seaport meets international standards, document their findings, and share this information with foreign government officials, DHS components, including CBP, and the public.[38] The Coast Guard reported that during fiscal years 2023 and 2024, Coast Guard program personnel visited 74 of its 123 maritime trading partners, as shown in figure 4 below.[39]

Figure 4: U.S. Coast Guard International Port Security Program Country Visits in Fiscal Years 2023 and 2024

Note: According to the Coast Guard, Coast Guard personnel visited Costa Rica in fiscal year 2024 and Nigeria in both fiscal years 2023 and 2024. In total, Coast Guard program personnel conducted 78 country visits in fiscal years 2023 and 2024.

In 2023, we found that while the Coast Guard documents its assessment results in various reports, it did not share its results with CBP, which CBP needs to review to carry out its work for its Container Security Initiative (CSI) program.[40] Specifically, CBP’s CSI program must assess the Coast Guard’s foreign port assessment findings, among other factors, when designating foreign seaports to participate in its efforts to examine high-risk maritime containers before their departure to the U.S., which is further discussed below. In April 2023, we recommended that the program share its findings with CBP and other relevant agencies with a vested interest. In June 2023, the Coast Guard shared its findings with CBP and established procedures to ensure it provided future findings to CBP and other relevant agencies that fully addressed this recommendation. By disseminating its findings to CBP and other relevant agencies, the Coast Guard program can better support CBP’s requirement to assess its foreign port assessments and support its policy for a whole of government approach for securing the U.S. supply chain.

Based on the program’s findings, the Coast Guard can set conditions of U.S. entry for vessels departing from those foreign seaports that the program determined are not implementing effective antiterrorism measures, such as requiring that each access point to the vessel is guarded while the vessel is in those foreign seaports. The program also can provide capacity building and technical assistance to foreign seaport officials to help improve seaport security and maritime governance. According to Coast Guard program guidance, at U.S. seaports, Coast Guard personnel are to consider International Port Security Program findings when screening incoming vessels and take certain actions, such as verifying that vessel operators implemented security measures at selected foreign seaports (discussed later in this report under the Coast Guard Port State Control Program).

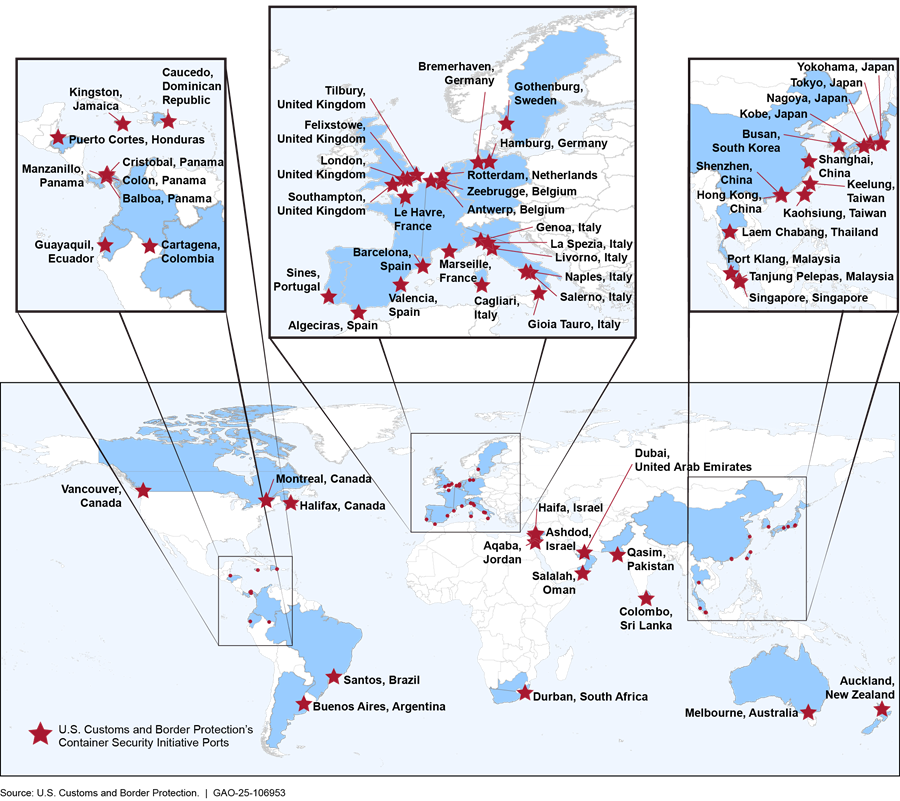

CBP Container Security Initiative (CSI) program. According to CBP, the CSI program aims to identify and examine U.S.-bound maritime container shipments that pose a security risk. CBP established CSI in January 2002 to address concerns (after the attacks on September 11, 2001) that terrorists could smuggle weapons of mass destruction or other contraband inside U.S.-bound containers.[41] As of September 2024, 61 seaports participated in the CSI program, as shown in figure 5 below. According to our prior work, these seaports collectively accounted for 72 percent of the cargo shipped to the U.S. by volume, as of April 2022.[42]

Figure 5: U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s Container Security Initiative Ports as of September 2024

CSI personnel target and examine high-risk, U.S.-bound containers as early as possible in their movement through the global supply chain. To do so, the CSI program stations personnel at participating foreign seaports to work with their counterparts to target and examine such containers before they are loaded onto vessels at their respective seaports.[43] CSI personnel work with the host country’s government to mitigate high-risk container shipments, which may include resolving discrepancies in shipment information and requesting their foreign counterparts to scan cargo containers’ contents with radiation detection or imaging equipment. If these scans indicate the potential presence of weapons of mass destruction or other contraband, CSI personnel are to request that the host government physically examine the shipment. If the host government declines, CSI personnel can issue a “do not load” order to prevent the shipment from being loaded onto a U.S.-bound vessel. Alternatively, they can flag the shipment for further examination upon arrival at a U.S. seaport, which is discussed in more detail below.

CBP Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism Program. In November 2001, CBP established the Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism Program as part of its efforts to facilitate the free flow of goods, while ensuring that the cargo containers do not pose a threat of terrorism.[44] This voluntary, incentives-based program works with private entities in the global trade community, such as importers and carriers, to improve their security practices and the security practices of their business partners. In 2017, we reported that the program faced challenges in meeting its security validation responsibilities because of problems with the functionality of the program’s data management system and limitations in the agency’s ability to determine the extent to which program members were receiving benefits because of data problems.[45] We recommended, among other things, that CBP develop standardized guidance for field offices regarding the tracking of information on security validations and CBP has taken actions to fully close these recommendations.

Entities that join the program commit to improving the security of their supply chains, such as through implementing proper container seal practices, and agree to provide CBP with information on their specific supply chain security measures.[46] In addition, the entities agree to allow CBP to validate, among other things, that their security practices meet or exceed CBP’s minimum security requirements. In return for their participation in the program, members receive benefits such as fewer CBP examinations at U.S. ports.[47]

CBP personnel from the Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism program determine applicants’ eligibility by reviewing their compliance with customs laws and any history of violations, among other things, and certify members if their security measures meet minimum standards. Within 1 year of certification, the program is to validate these security measures through a site visit to the member and, if the member is an importer, at least one foreign supply chain partner’s site. Once members are validated, the program is to review their eligibility status, among other things, on an annual basis and revalidate their security measures every 4 years.

Coast Guard and CBP Intelligence Programs Screen and Target Vessels and Cargo En Route to U.S. Seaports

Coast Guard and CBP intelligence programs located across the U.S. screen information about U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo while they are en route to identify and target any that are high risk and could pose threats.[48] When appropriate, these programs alert seaport personnel to take further action.

CBP National Targeting Center (NTC). Established in 2001 and based in Sterling, Virginia, the NTC is staffed by CBP and Coast Guard personnel, among other federal agencies.[49] The center conducts risk-based screening of maritime cargo, vessels, and people attempting to enter the U.S.[50] Within the NTC, the cargo division focuses on screening and targeting efforts to identify potentially high-risk cargo shipments. For example, Coast Guard personnel in the cargo division told us they often find unmanifested container shipments and alert U.S. port personnel for further action because they are unaware of the content inside those containers. While the focus of personnel at foreign and U.S. seaports is on assessing shipments transiting from or to their respective seaports, personnel in the cargo division assess shipments for security risks from a national perspective, and alert seaport personnel for further action. For example, if personnel in the cargo division have specific intelligence regarding an attempt to smuggle a weapon of mass destruction in a container, the division can identify whether any shipments destined for the U.S. match the intelligence information, regardless of the seaport of arrival.

Cargo division personnel also serve as a resource for other targeting units stationed at foreign and U.S. seaports due to the NTC’s access to research tools, such as classified databases, that may not be available to field personnel. For example, CSI personnel stationed at the NTC’s cargo division support CSI teams stationed at foreign seaports by researching leads provided by foreign-based CSI teams and conducting remote targeting for high volume ports.[51] Similarly, Coast Guard personnel at U.S. seaports can request additional intelligence information from NTC personnel for screening operations, such as background checks of persons on board a vessel.

Coast Guard Maritime Intelligence Fusion Centers—Atlantic and Pacific. The Coast Guard’s Maritime Intelligence Fusion Centers are in two locations: the Atlantic center in Dam Neck, Virginia and the Pacific center in Alameda, California. These centers serve as hubs for maritime intelligence sharing and analysis at the operational and tactical level in their area of operation. According to the Coast Guard, the centers are responsible for screening U.S.-bound vessels from foreign seaports, tracking vessels from all over the world, and providing actionable intelligence to Coast Guard commanders in the field.

Domestic intelligence and targeting units. At or near U.S. seaports, Coast Guard and CBP personnel within intelligence and targeting units review advance information related to U.S.-bound vessels, maritime cargo, and persons on board a vessel destined for seaports within their respective region to identify potential security risks. For example, Coast Guard personnel advise unit commanders on all intelligence information related to potential risks to integrate them into Coast Guard missions, such as vessel boardings and inspections. Similarly, CBP personnel target potentially high-risk cargo shipments and flag them for further examination at a U.S. seaport. According to CBP officials, CBP targeting personnel at U.S. seaports are intended to augment the NTC’s assessments as an added layer of security screening to ensure vessel and cargo risks are not missed.

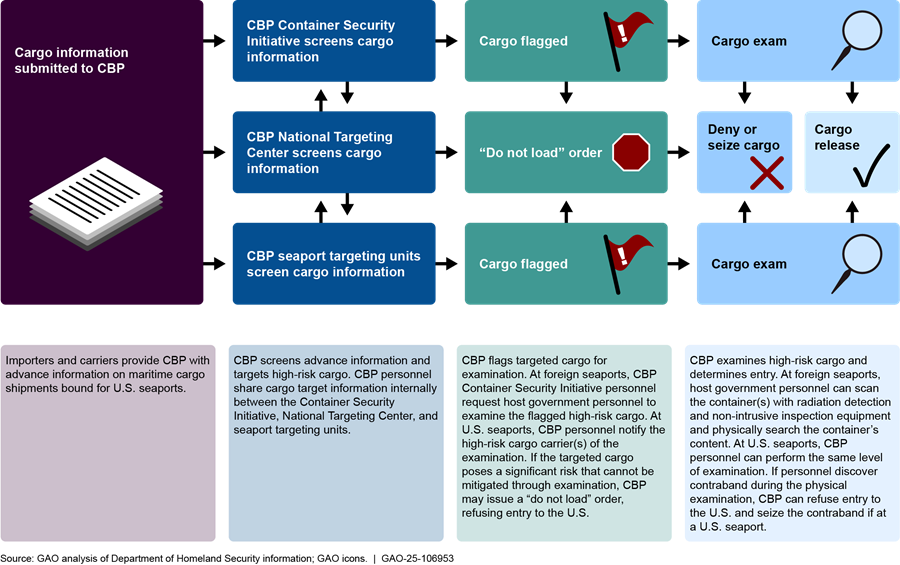

Additionally, CBP personnel may target a shipment with risks that cannot be mitigated through other means, including examining the shipment at a CSI port overseas or obtaining additional information about the shipment from importers and carriers. In such cases, personnel may seek approval for a “do not load” order from the NTC’s cargo division before a shipment is loaded onto a U.S.-bound vessel. Once a shipment is loaded onto a vessel, personnel continue to review shipment data and use other sources, such as public records. Using these data and information, CBP personnel will assess whether the shipment could pose a risk and, as appropriate, may target the shipment for examination upon arrival at a U.S. seaport. See figure 6 for an overview of the key steps CBP personnel may take to screen and target high-risk maritime cargo bound for the U.S.

Figure 6: Key Steps in U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Process for Screening and Targeting High-Risk Cargo Throughout the Maritime Supply Chain

Coast Guard and CBP Inspect Vessels and Maritime Cargo for Security Risks Upon Arrival at U.S. Seaports

At U.S. seaports, the Coast Guard and CBP may board targeted high-risk vessels or further examine high-risk maritime cargo at a seaport and offshore to (1) address security breaches, (2) examine documentation of cargo and persons onboard, and (3) examine vessels and cargo for safety concerns.

Coast Guard maritime law enforcement. At U.S. seaports, Coast Guard armed law enforcement personnel, known as boarding teams, may board arriving and departing vessels of interest to examine cargo, documentation, and persons on board, and to deter acts of terrorism and transportation security incidents.[52] According to Coast Guard officials, the purpose of security exams is to ensure vessels maintain an appropriate security posture while in transit and in port to prevent security threats to the vessel and port, among other things. For example, according to the Coast Guard’s Maritime Law Enforcement Manual, boarding teams are to investigate any law enforcement intelligence related to the vessel and crew and may include a search for contraband and stowaways onboard.[53] Coast Guard maritime law enforcement personnel can also escort certain high-risk vessels and enforce security zones to mitigate risk.[54] The Coast Guard uses classified policy and procedures to target vessels for security boardings.

Coast Guard Port State Control Program. After the Coast Guard’s boarding teams inspect vessels to ensure no security threat exists, the Port State Control Program examines arriving and departing foreign-flagged vessels operating in U.S. waters. According to Coast Guard policy, the examinations are intended to verify that these vessels comply with applicable international conventions, as well as federal statutes and regulations.[55] The goal of the program is to remove substandard vessels from U.S. waters to reduce deaths and injuries, loss of or damage to property or the marine environment, and disruptions to maritime commerce.[56] At U.S. seaports, program personnel conduct exams by doing a walk-through and visual assessment of a vessel’s certificates and operating systems, such as navigation equipment, among other things.[57]

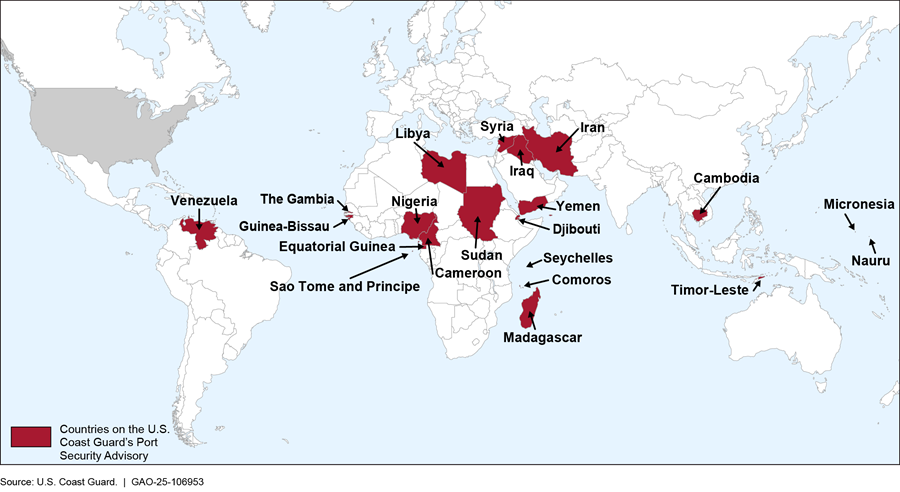

Additionally, according to the policy, Coast Guard personnel are to also verify that, if conditions of entry have been imposed, incoming vessels have implemented additional security measures at selected foreign seaports determined by the International Port Security Program to not have effective antiterrorism measures. Coast Guard personnel are to verify that vessels took appropriate action while in those selected foreign seaports by interviewing vessel crew and reviewing documentation, such as security company contracts or payment receipts, according to the policy. As of October 2024, Coast Guard personnel at U.S. seaports are to verify conditions of entry of U.S.-bound vessels departing from 21 countries, as shown in figure 7.[58]

Figure 7: Countries with Ports Not Maintaining Effective Antiterrorism Measures as Identified by the U.S. Coast Guard, as of October 2024

If personnel find discrepancies or security breaches on board an incoming vessel, the Coast Guard can take actions to safeguard the U.S. seaport, personnel, and the environment. According to the Coast Guard’s policy, the agency can take the following actions:

· Denial of entry/expulsion. The Coast Guard uses a denial of entry/expulsion when allowing a vessel to enter or remain in U.S. waters would create an unacceptable level of risk, or an immediate threat to the seaport, personnel, or the environment.

· Captain of the Port order. The Coast Guard uses these orders as a tool to protect the safety and security of the seaport. Under certain conditions, the Captain of the Port of a Coast Guard sector may issue this order to direct a variety actions, including controlling the vessel’s movement as it enters or departs a seaport. The Captain of the Port may also use this order to expel a vessel out of a seaport.

· Customs hold. Certain vessels intending to depart the U.S. for a foreign seaport must obtain a clearance from CBP.[59] If the Coast Guard suspects that a vessel has violated certain U.S. safety and pollution laws, according to the Coast Guard’s policy, the Coast Guard may request that CBP deny or withhold the required clearance from the vessel until the vessel’s responsible party takes corrective actions.

CBP field operations. Under CBP’s Office of Field Operations, field personnel are responsible for inspecting maritime cargo at 126 U.S. seaports. CBP has 20 field offices that oversee all U.S. port of entry operations within their designated areas of responsibility, which include 18 field offices responsible for cargo security operations at U.S. seaports. CBP Port Directors are responsible for managing the day-to-day cargo security operations for U.S. seaports within their geographic area of responsibility, which includes implementing national policy and maintaining the seaports’ cargo inspection program.

According to CBP officials, CBP field personnel at U.S. seaports secure arriving vessels by boarding every vessel from foreign seaports to inspect the persons on board and search for potential stowaways and contraband. For example, personnel search the vessel itself for contraband, including underwater inspections for parasitic devices. CBP field personnel may also search cargo on board, if needed, verify vessel certificates, and compliance with other CBP trade laws and regulations for declaration and safe keeping of merchandise on board, according to CBP officials.

CBP field personnel examine the arriving cargo flagged by their targeting teams to address potential threats.[60] Specifically, personnel at U.S. seaports that are part of CBP’s Anti-Terrorism Contraband Enforcement Teams may examine the cargo by, among other methods, scanning it with non-intrusive inspection equipment, such as mobile x-ray machines (see fig. 8). CBP personnel review the scans to detect anomalies that could indicate the presence of weapons of mass destruction or contraband.

Figure 8: A Shipping Container Passing Through U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s Non-Intrusive Inspection Screening Equipment at the Long Beach Container Terminal Within the Port of Long Beach

According to CBP guidance and officials, if CBP personnel detect an anomaly, the cargo or container may be transferred to a centralized examination station or similar location for further examination. At that point, CBP personnel will remove and physically examine the cargo or container’s contents. If personnel discover contraband during the physical examination, CBP seizes it; otherwise, CBP releases the cargo back into the flow of commerce.

DHS Generally Followed Selected Leading Collaboration Practices at U.S. Seaports

The Coast Guard and CBP at nearly all field units included in our review generally followed five selected leading collaboration practices identified in prior GAO work in their efforts to secure U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo from national security risks.[61] The five practices are (1) define common outcomes, (2) clarify roles and responsibilities, (3) include relevant participants, (4) leverage resources and information, and (5) develop and update written guidance and agreements.[62] While we have organized our findings on the selected leading collaboration practices individually in the following sections, they are interrelated and reinforce each other, and are not sequenced in any particular order.

Define common outcomes. According to expert views and our prior work, having a shared purpose can provide people with a reason to participate in the collaborative process.[63] Officials we interviewed from nearly all field units (15 of 16) identified common outcomes or missions with their counterpart.[64] For example, CBP officials from one field unit acknowledged that both the Coast Guard and CBP have roles in protecting the nation from terrorism, intercepting drug smuggling, and looking for stowaways on vessels. Coast Guard officials from another field unit said that both the Coast Guard and CBP share the mission of seaport safety and security. At another field unit, the Coast Guard established a group with other federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies—including CBP—to achieve the common goal of promoting safety and security, in addition to protecting life and property in the region.

Clarify roles and responsibilities. Clarifying roles and responsibilities between agencies can be achieved by identifying and leveraging authorities, among other things.[65] Additionally, defined and agreed-upon roles and responsibilities can often help to overcome barriers when working across agency boundaries. Officials we interviewed from all 16 field units reported having clarified roles and responsibilities related to collaboration with their counterpart. For example, CBP officials at one field unit said CBP and the Coast Guard have overlapping authorities related to the enforcement of the Jones Act; CBP has provided training to the Coast Guard to help educate personnel, especially new ones, on CBP’s related roles and responsibilities.[66] Coast Guard officials from a field unit at the same location confirmed that CBP provided training related to the Jones Act and said more training would be helpful to further understand overlapping roles and responsibilities with CBP.

CBP officials at another field unit stated that there is a clear line of delineation of responsibilities between where the Coast Guard and CBP have jurisdiction over a vessel, which allows them to coordinate their activities. For example, officials stated that CBP has lead responsibilities when a vessel is dockside, while the Coast Guard has lead responsibilities when a vessel is enroute to a pier in the water. Coast Guard officials at another field unit also noted that they were knowledgeable of the delineation of responsibilities between both agencies, understanding that the Coast Guard focuses on regulating the vessel, the crew, and hazardous cargo, while CBP focuses on screening and managing all other cargo.

|

Example of Including Relevant Participants in the Field The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) established Joint Intelligence Operations Coordination Centers across the U.S. to coordinate operations between DHS components in the field. These centers can include staff from multiple DHS components. For example: In 2020, DHS established a Joint Intelligence Operations Coordination Center in South Florida to act as a unified control center in the area and coordinate operations between participating agencies. This center is staffed by personnel from multiple DHS components, including U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations, and the U.S. Coast Guard. According to officials we spoke with from this center, personnel hold calls twice a week with local partners and partners across Florida, all internal to DHS, to discuss upcoming operations or requests for information. Included in the calls are U.S. seaport-level personnel across Florida from the Coast Guard, CBP, and ICE Homeland Security Investigations, among others. Source: Department of Homeland Security. | GAO‑25‑106953 |

Include relevant participants. Collaborative efforts that include relevant participants provide a diverse group of perspectives.[67] This allows the group to consider an issue from all sides, which is important when solving complex problems. Officials we interviewed from nearly all field units (15 of 16) reported identifying and including relevant participants to collaborate with their counterpart. For example, Coast Guard and CBP officials at 12 field units said relevant participants are involved in their interagency collaborative mechanisms. At one location, Coast Guard officials said the relevant entities they work with are involved in their Regional Coordinating Mechanism (ReCoM)—a DHS interagency collaborative mechanism for resources and information sharing in the maritime domain. The ReCoM includes personnel representing CBP and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations, a DHS federal law enforcement agency responsible for conducting federal criminal investigations into the illegal movement of people, contraband, and weapons, among other responsibilities. Additionally, CBP officials at another location described a special unit that includes personnel from the Coast Guard, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, ICE Homeland Security Investigations, state police, and other federal agencies who work together to analyze vessel and cargo threats.

Leverage resources and information. To successfully address crosscutting challenges or opportunities, collaborating agencies must successfully leverage available staffing, funding, and technological resources.[68] Because crosscutting challenges and opportunities require coordination among multiple agencies, in many cases, no single organization or individual has the authority, resources, or skills necessary to address them. Officials we interviewed from all 16 field units reported leveraging resources and information to collaborate with their counterpart. For example, CBP officials at one location said they asked the Coast Guard to use its authority to order a vessel to keep out of their area’s waters due to security concerns, since CBP does not

|

Examples of Leveraging Resources and Information in the Field According to Department of Homeland Security operations reports, U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officials have worked together on joint operations in the field. These agencies leverage each other’s resources, such as staff. Examples of this include: · Night Crawler Operation. Led by Coast Guard Sector Miami in 2024, this joint effort—conducted with CBP and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Homeland Security Investigations—resulted in an unannounced operation at four regulated facilities to verify the facilities and vessels there complied with applicable requirements and regulations. · Multi Agency Strike Force Operation Oahu. Led by Coast Guard Sector Honolulu in 2022, this joint effort allowed agencies to work together to inspect and examine containers to better understand each participant’s roles, responsibilities, and authorities. Participants included the Coast Guard, CBP, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and local police.

Source: Department of Homeland Security and U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Kimberly Reaves. | GAO‑25‑106953 |

have this authority.[69] Coast Guard officials at another location stated that they enlisted the help of other agencies—such as CBP and ICE Homeland Security Investigations—for vessel boardings due to their staffing challenges. Officials stated that this acts as a force multiplier and allows the Coast Guard to accomplish more activities and ensure they are conducting operations legally and safely.

In our prior work on leading collaboration practices, we also reported that collaborative efforts can use pilot tests to learn and foster agencies’ willingness to participate.[70] By committing a limited number of resources in a smaller-scale approach to the crosscutting challenge or opportunity, groups can identify unanticipated consequences and implementation challenges, or gather information on program effectiveness. In May 2023, Coast Guard and CBP initiated a pilot program to allow selected Coast Guard personnel at seaports within nine Coast Guard sectors to gain direct access to one of CBP’s primary systems used to assess U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo for national security risks.[71] According to Coast Guard officials responsible for managing the pilot, the goal of the pilot program is to provide Coast Guard personnel at U.S. seaports with additional information for increased situational awareness. The pilot is also intended to create a new vessel screening process, which includes shifting duties within the Coast Guard, among other goals. As of May 2024, Coast Guard officials reported that the effort is still underway. The Coast Guard’s pilot program is consistent with the leading collaboration practice’s key consideration of having methods, tools, or technologies to share relevant data and information.

Develop and update written guidance and agreements. According to expert views, written guidance and agreements can be used as a framework outlining how a collaborative effort operates and how decisions will be made.[72] Officials from nearly all field units we interviewed (14 of 16) reported developing guidance to collaborate with their counterpart. For example, Coast Guard officials at one location said they developed a charter for their area’s ReCoM that identifies the participating agencies and their responsibilities. The agencies include CBP, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, ICE Homeland Security Investigations, the Transportation Security Administration, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, and several state agencies. CBP officials at another location said that their collaboration with the Coast Guard is guided by their mutually developed operating guidance for their local area maritime security committee—another DHS interagency collaborative mechanism that includes similar participants in the maritime domain.[73] This local operating guidance contains information on communication methods between CBP, the Coast Guard, and others.[74]

We reviewed ReCoM and area maritime security committee charters that cover a sample of selected field units at four of eight seaports in our review and found they generally incorporated several leading collaboration practices. For example, one area maritime security committee charter we reviewed contained information on common outcomes or objectives, clarified roles and responsibilities, and included relevant participants, among other leading collaboration practices. Similarly, one ReCoM charter we reviewed contained information on relevant participants, common outcomes, and information sharing methods. These charters support the components’ use of leading collaboration practices.[75]

We have also found that written guidance and agreements can be used to document and monitor the application of interagency collaboration practices and key considerations for implementation related to any collaborative effort.[76] Officials from six of the 14 field units who reported developing written guidance also said they use national-level guidance that DHS has developed to help facilitate collaboration in the field. For example, CBP officials from one location stated that they developed their ReCoM charter based on information in DHS’s Maritime Operations Coordination Plan—a strategic-level document that establishes cross-component collaboration in the maritime domain to target the threat of transnational terrorist and criminal acts along the coastal borders.[77]

|

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Updated Its Maritime Operations Coordination Plan in 2023 According to DHS officials, the department updated its Maritime Operations Coordination Plan in 2023 to improve component collaboration in the field through new guidance and support structures. The updated plan includes requirements for DHS to establish a functioning oversight and support structure to ensure department components in the field—including those within the Coast Guard and U.S. Customs and Border Protection—collaborate to execute the plan’s objectives. The objectives include preventing criminal acts in the maritime domain and obtaining needed resources. Based on our review of DHS documents, the department has taken steps to implement the new requirements. Specifically: · In August 2024, DHS finalized new guidance for components to establish an oversight and support structure. · In September 2024, DHS established a new support office responsible for facilitating the connection between oversight groups and the field components and for providing guidance. · In October 2024, DHS developed steps, including a timeline with milestones, to fully implement the updated plan by March 2025. DHS officials told us that the intended guidance and structure associated with the updated plan could make component collaboration in the field stronger and provide them needed resources to achieve their mission. |

Source: GAO analysis of DHS information. | GAO‑25‑106953

CBP officials at another location said they use a national-level memorandum of understanding with the Coast Guard to process high-risk crew members on board U.S.-bound vessels.

DHS Has Not Fully Assessed the Effectiveness of Its Approach for Securing Vessels and Maritime Cargo

The Coast Guard and Transportation Systems Sector partners are responsible for supporting the Sector’s mission to continuously improve the security and resilience posture of the nation’s transportation systems to ensure the safety and security of travelers and goods.[78] The 2015 Transportation Systems Sector-Specific Plan outlines four strategic goals—goals that outline broad, long-term outcomes to achieve—for how the sector contributes to the overall security and resilience of the Nation’s critical infrastructure.[79] The fourth strategic goal is to enhance the all-hazards preparedness and resilience of the global transportation system to safeguard U.S. national interests. To achieve this goal, the sector-specific plan identifies five activities related to the maritime subsector, to include a sector activity to identify, assess, and prioritize efforts to manage supply chain risk using layered defenses.[80]

|

Definitions of Strategic Goals, Performance Goals, and Performance Measures In prior work, GAO has identified key practices that help agencies achieve results and improve performance, including: · Strategic goals: outcome-oriented statements of aim or purpose. They articulate what the organization wants to achieve in the long-term to advance its mission and address relevant problems, needs, challenges, and opportunities. · Performance goals: specific results an agency expects the program to achieve in the near term. Our prior work indicates that it can be beneficial for performance goals to have specific targets and time frames that reflect strategic goals. · Performance measures: concrete, objective, observable conditions that permit the assessment of progress made towards the agency’s goals. Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑106953 |

According to DHS’s 2018 Transportation Systems Sector Activities Progress Report, between 2015 and 2018, the Coast Guard made varied progress on the maritime activities outlined in the Transportation Systems Sector-Specific Plan.[81] Additionally, in June 2024, Coast Guard officials provided GAO an update on its progress since 2018, stating that Coast Guard had completed three of the five activities outlined in the sector-specific plan. However, agency officials acknowledged that, as of June 2024, the agency has not documented any progress towards achieving the strategic goal since 2018. See table 2 for more information on this strategic goal, the associated maritime activities, and progress in completing these activities.

Table 2: Completion Status of Maritime Activities Associated with Sector Goal Four of the 2015 Transportation Systems Sector-Specific Plan, as Reported by Coast Guard Officials in June 2024

|

Sector goal four |

Activities to achieve goal |

Status |

|

Enhance the all-hazards preparedness and resilience of the global transportation system to safeguard U.S. national interests |

Identify, assess, and prioritize efforts to manage supply chain risk using layered defenses in a changing security and operational environment |

Complete |

|

Periodically assess supply chain security risks for all ports that ship cargo to the U.S. under the Cargo Security Initiative. |

Complete |

|

|

Formalize information sharing arrangements between Federal agencies focused on cargo arriving and departing the U.S., including law enforcement entities operating in the joint National Targeting Center for Cargo and those agencies, such as the Office of Naval Intelligence, focused on cargo moving between foreign ports. |

Complete |

|

|

Identify and address critical infrastructure supply chain cross-sector dependencies. |

Not complete – in progress |

|

|

Identify and use lessons learned from supply chain disruption events to inform policies and programs that enhance our Nation’s preparedness. |

Not complete – in progress |

Source: GAO review of U.S. Coast Guard information. | GAO‑25‑106953

|

Selected Leading Practices Related to Performance Goals and Measures According to leading practices we identified to assess the effectiveness of federal efforts, effective organizations establish performance goals and measures to help assess and manage program performance. For goals and measures to be useful for performance management, the practices indicate that they should reflect key attributes, which include being: · Objective. Performance goals and measures are reasonably free of significant bias or manipulation that would prevent them from providing an accurate assessment of performance. · Measurable. Performance goals and measures are able to demonstrate whether or not a specific level of performance can be tangibly demonstrated and independently verified. · Quantifiable. Performance goals and measures have a numerical or measurable value. Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑106953 |

Note: According to the Transportation Systems Sector Specific Plan, the sector’s fourth goal is to enhance the all-hazards preparedness and resilience of the global transportation system to safeguard U.S. national interests.

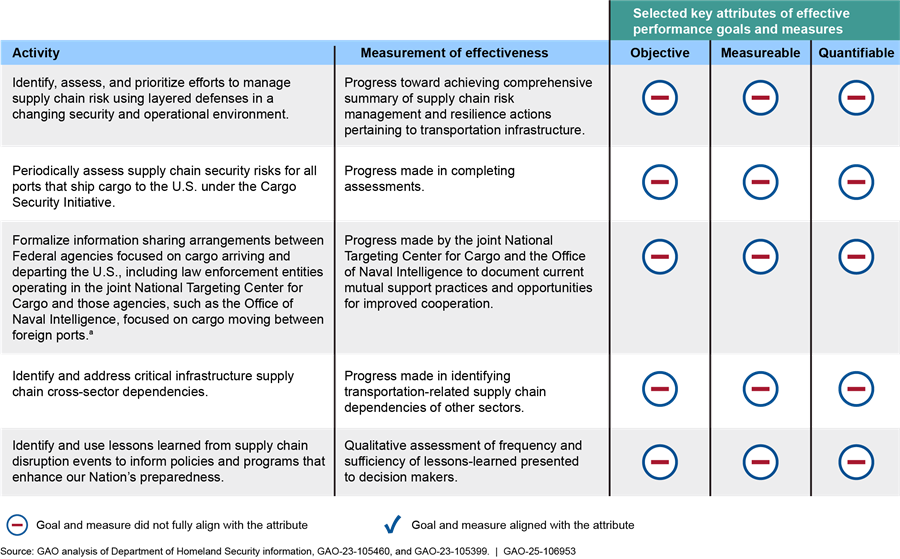

The Transportation Systems Sector-Specific Plan established a strategic goal and activities relevant to assessing DHS’s layered maritime security approach. However, the plan did not establish performance goals or associated performance measures that contain selected key attributes we have identified in prior work.[82] According to key practices we identified to assess the effectiveness of federal efforts, performance goals are target levels of performance to be accomplished within a timeframe and are generally expressed as tangible, measurable objectives. They can also be expressed as quantitative standards, values, or rates. Performance measures are concrete, objective, observable conditions that permit the assessment of progress made toward the agency’s goals.[83] Further, our prior works states that management should establish goals to communicate the results agencies seek to achieve to advance their mission, and to allow decision makers and stakeholders to assess performance by comparing planned and actual results.[84] Performance measurement also encompasses the ongoing monitoring and reporting of a program’s accomplishments and progress. Similarly, the National Infrastructure Protection Plan’s Critical Infrastructure Risk Management Framework recommends that organizations use metrics and other evaluation procedures to measure progress and assess the effectiveness of efforts to secure and strengthen the resilience of critical infrastructure. The framework further states that doing so informs the process of prioritizing and selecting the most effective and cost-efficient ways to manage risk.[85]

The sector-specific plan cites five activities with related actions the Coast Guard and sector partners could take to achieve the strategic goal (i.e., performance goals). Each activity includes a “measurement of effectiveness” to assess whether they are taking actions to achieve the activities (i.e., performance measures). However, these activities and measures are not objective, quantifiable, or measurable. See figure 9 for our assessment of each activity and their measures of effectiveness.

Figure 9: Sector Goal Four’s Associated Activities and Measurements of Effectiveness Compared with Selected Key Attributes of Effective Goals and Measures

Note: According to the Transportation Systems Sector Specific Plan, the sector’s fourth goal is to enhance the all-hazards preparedness and resilience of the global transportation system to safeguard U.S. national interests.

aThe National Targeting Center is staffed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection and Coast Guard personnel, among other federal agencies.

As noted above, all five activities and their corresponding measures of effectiveness are described in a qualitative manner but are not expressed in a measurable or quantifiable manner. For example, none of the activities or measures define a specific, numerical target.[86] For instance, the measure regarding progress made in identifying transportation-related supply chain dependencies of other sectors does not define any specific targets, conditions, or time frames. The lack of specific targets means it is also unclear whether the current goals and measures will be objective measures of progress. For instance, the activity calling to periodically assess supply chain risks for all ports that ship cargo to the U.S. under the Container Security Initiative is not objective because we do not know what specific supply chain risks the activity is referring to or what specific time periods the activity is evaluating. This could allow the Coast Guard and sector partners to present results in ways that look more or less favorable. Further, without formalized performance goals that have target levels of performance to be accomplished within a time frame and associated performance measures that would permit the assessment of progress made toward the agency’s goals, the Coast Guard and sector partners cannot assess the effectiveness of their approach for securing vessels and maritime cargo on an ongoing basis.

While the Coast Guard reported making progress on the maritime activities outlined in the sector-specific plan, officials acknowledged that the agency has not yet developed performance goals and related measures for these activities. Coast Guard officials stated that this was because they were waiting for an update to Presidential Policy Directive 21 before continuing work.[87] In April 2024, the President issued National Security Memorandum 22 to replace Presidential Policy Directive 21. National Security Memorandum 22 calls for designated sector risk management agencies, such as the Coast Guard, to identify the most significant critical infrastructure risks to their sector and develop or refresh an associated sector-specific risk management plan every 2 years. Further, the memorandum calls for agencies to develop objective performance goals and metrics to mitigate risks.[88] Officials stated that in response to this, the agency began to develop an updated sector risk assessment to inform the updates to its sector risk management plan, which will describe the sector’s goals and activities. They also noted that the agency is still early in the process of developing the new sector risk management plan, which is to be completed by January 2025. They said they planned to continue carrying out work for the five sector-specific activities identified in the 2015 plan, in addition to developing performance measures.

As previously discussed, organizations should establish performance goals and measures that are objective, measurable, and quantifiable. Additionally, organizations should use metrics and other evaluation procedures to measure progress and assess the effectiveness of efforts to secure and strengthen the resilience of critical infrastructure.[89] Coast Guard officials acknowledged that it has not yet developed such goals and measures. By updating the new sector risk management plan with performance goals and performance measures that are objective, quantifiable, and measurable, the Coast Guard and its Transportation Systems Sector partners will be better positioned to assess the effectiveness of their progress as required by National Security Memorandum 22. Using these performance goals and performance measures as a tool to assess the effectiveness of their approach on an ongoing basis would better position the agency and sector partners to monitor progress and determine how to best allocate resources to achieve the desired risk management posture for securing vessels and maritime cargo. Further, doing so would provide additional information that could help Congress oversee efforts the Coast Guard and sector partners are taking to accomplish their mission.

Conclusions

The secure transit of U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo is vital to the global supply chain and the U.S. economy. Criminal activity or terrorist attacks using cargo shipments could cause disruptions to the supply chain and limit global economic growth and productivity. Coast Guard and CBP at nearly all field units included in our review generally followed five selected leading collaboration practices in their efforts to secure U.S.-bound vessels and maritime cargo from national security risks. Additionally, the Coast Guard, the DHS agency assigned with responsibility for leading efforts to support the maritime domain under the Transportation Systems Sector Specific Plan, and sector partners have identified a strategic goal and activities relevant to assessing DHS’s layered maritime security approach.

However, the Coast Guard and sector partners have not developed objective, measurable, and quantifiable performance goals and associated measures that would allow the agency and its partners to effectively assess its approach on an ongoing basis. By developing and using such performance goals and measures to assess the effectiveness of its layered maritime security approach on an ongoing basis, the Coast Guard and sector partners will have a better understanding of the effectiveness of each activity in achieving their strategic goal. Further, Congress, the Coast Guard, and sector partners will be better positioned to oversee whether the agency is achieving its mission. Such assessments could help them make informed decisions about which maritime security efforts should be continued or expanded and where resources should be allocated and select the most effective ways to mitigate supply chain risks in the maritime domain.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making two recommendations to the Coast Guard. Specifically:

The Commandant of the Coast Guard, in coordination with Transportation Systems Sector partners, should develop objective, measurable, and quantifiable performance goals and associated performance measures. (Recommendation 1)

The Commandant of the Coast Guard, in coordination with Transportation Systems Sector partners, should use the performance information collected to assess progress toward strategic and performance goals and the overall effectiveness of the layered approach to securing vessels and maritime cargo on an ongoing basis. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DHS for review and comment. DHS provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix II. DHS concurred with our recommendations and described planned actions to address them. DHS also provided technical comments, we which incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Secretary of Homeland Security. In addition, the report is also available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-8777 or macleodh@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on

the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Heather MacLeod

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

To determine the extent to which the U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officials followed selected leading collaboration practices, we gathered information at the field-level by conducting semi-structured interviews with a non-generalizable sample of Coast Guard and CBP officials from 16 field units at eight selected U.S. seaports. Participating officials ranged from leadership—such as CBP Port Directors, Coast Guard sector department heads, and Coast Guard Captains of the Port—to front-line personnel responsible for specific operations at the seaports.[90] In addition to the semi-structured interviews, we obtained documents relevant to collaborative efforts—including documents specific to the individual seaport—and sent follow-up questions regarding collaboration efforts, when necessary.

We conducted in-person site visits to two of the eight U.S. seaports identified in our site selection—the Port of Los Angeles-Long Beach and the Port of Miami—to observe Coast Guard and CBP port-level operations and obtain information on any collaboration or information-sharing activities used by seaport-level officials to secure vessels and maritime cargo. See table 3 for a list of locations we selected to interview Coast Guard and CBP officials from the responsible field units.

Table 3: Location of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and U.S. Coast Guard Officials Interviewed

|

Location |

Agency area of responsibility |

|

Los Angeles, California |

Port of Los Angeles-Long Beach (CBP) and Sector Los Angeles-Long Beach (Coast Guard) |

|

Norfolk, Virginia |

Port of Norfolk-Newport News (CBP) and Sector Virginia (Coast Guard) |

|

Miami, Florida |

Port of Miami (CBP) and Sector Miami (Coast Guard) |

|

Duluth, Minnesota |

Port of Duluth-Superior (CBP) and Marine Safety Unit Duluth (Coast Guard) |

|

Honolulu, Hawaii |

Port of Honolulu (CBP) and Sector Honolulu (Coast Guard) |

|

Staten Island, New York and Newark, New Jersey |

Port of New York-New Jersey (CBP) and Sector New York (Coast Guard) |

|

Houston, Texas |

Port of Houston (CBP) and Sector Houston-Galveston (Coast Guard) |

|

Portsmouth, New Hampshire |

Port of Portsmouth (CBP) and Sector Northern New England (Coast Guard) |

Source: CBP and Coast Guard. | GAO‑25‑106953

To select the U.S. seaport locations, we collected and analyzed Coast Guard data on vessel inspections and examinations, and CBP Automated Commercial Environment data on cargo volume and source for calendar years 2019-2023. Using these data, we selected U.S. seaport locations to obtain variation in, among other things, port size based on total import volume, the primary type(s) of cargo (e.g., containerized and non-containerized), the percentage of cargo volume made up of imports from other countries, the number of Coast Guard vessel inspections and examinations, and a diversity of geographic regions. To assess the reliability of data used for site selection, we reviewed documentation on the systems such as user guides and data dictionaries, reviewed the data for obvious errors and omissions, and interviewed agency officials responsible for maintaining the data and relevant data systems. We determined the data were reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

We then analyzed responses of officials from 16 field units at eight U.S seaports by conducting a content analysis to see whether they followed selected leading collaboration practices.[91] We selected five of the eight leading collaboration practices because they were the most relevant to the researchable objective and agencies in our scope. The practices we selected were (1) define common outcomes; (2) clarify roles and responsibilities; (3) include relevant participants; (4) leverage resources and information; and (5) develop and update written guidance and agreements. Specifically, we reviewed Coast Guard and CBP officials’ responses at each seaport location and coded whether their responses indicated that they followed one or more of the five selected leading practices.

To improve the validity of results, responses of Coast Guard and CBP officials we interviewed from each seaport location were coded independently by two analysts, who then compared the coding results. In instances where the analysts had differing results for a leading practice, they discussed their reasoning and reached agreement on which codes were the most appropriate.

GAO Contact

Heather MacLeod, (202) 512-8777 or MacLeodH@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Hugh Paquette (Assistant Director), Ricki Gaber (Analyst-in-Charge), Kevin Gonzalez, Benjamin Schaefer, and Emily Thomas made key contributions to this report. Also contributing to this report were Lauri Barnes, Benjamin Crossley, Dominick Dale, Kaelin Kuhn, Ben Licht, Nancy Lueke, Amanda Miller, Mary Offutt-Reagin, Janet Temko-Blinder, and Sarah Veale.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149