HEAD START

Action Needed to Reduce Potential Risks to Children and Federal Funds in Programs under Interim Management

Report to Congressional Requesters

December 2024

GAO-25-106954

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106954. For more information, contact Jacqueline M. Nowicki at (202) 512-7215 or nowickij@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106954, a report to congressional requesters

December 2024

HEAD START

Action Needed to Reduce Potential Risks to Children and Federal Funds in Programs under Interim Management

Why GAO Did This Study

The Department of Health and Human Services’ OHS has used the same interim manager for nearly 25 years to temporarily run programs in communities that have lost their provider. GAO was asked to review OHS’s oversight of programs under interim management.

This report examines the extent to which OHS’s monitoring allows it to assess whether programs under interim management meet Head Start standards related to service quality, child safety, finances, and enrollment, among other things.

GAO compared OHS’s oversight to relevant federal laws, regulations, and OHS’s monitoring procedures; analyzed enrollment data from the 2017-2018 through 2022-2023 school years; and compared state licensing violations to OHS records. GAO interviewed OHS officials and interim manager representatives, visited three Head Start programs to interview staff who worked under interim management, and interviewed representatives of another four programs that exited interim management since 2018. GAO selected programs that varied in size and time under interim management.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making seven recommendations, including for OHS to update aspects of its monitoring of Head Start programs under interim management and enforce enrollment standards. HHS concurred with five recommendations and did not concur with two, citing variation in program monitoring. GAO clarified and continues to believe they are warranted, as discussed in the report.

What GAO Found

When a community loses its Head Start provider, the Office of Head Start (OHS) deploys its interim manager to temporarily operate this federally funded early childhood education program. Since 2000, OHS has placed more than 200 programs under interim management. As of September 2024, 18 of 1,600 Head Start programs nationwide were under interim management. However, GAO found that OHS skipped crucial monitoring steps and did not enforce certain standards for programs under interim management for at least the last 5 school years. For example, it did not monitor half of the 28 programs due for monitoring between January 2020 and June 2024—leaving it unaware of documented and potential child safety incidents and other concerns. Further, OHS had neither assessed classroom quality nor monitored finances for all programs under interim management—both of which are required under the Head Start Act. Lastly, OHS officials stated that they had never enforced enrollment standards or required Head Start funds to be returned for children not served. In the 2022-2023 school year, GAO found that fewer than half of the nearly 4,000 Head Start seats available in programs under interim management were filled.

Local staff from all three Head Start programs GAO visited shared concerns about their experiences during interim management, including unqualified staff, unsafe facilities, and poor fiscal stewardship (see fig). Staff at all three programs told GAO that unqualified staff were put in classrooms to teach. Staff at two programs said facility hazards, including mold, were not properly remediated. Staff at all three programs expressed concerns about fiscal management—from expensive and unnecessary equipment orders in one program to a lack of essential supplies, like diapers and wipes, in another.

OHS officials said they work closely with the interim manager to keep Head Start programs open under challenging circumstances. However, OHS has not consistently monitored programs under interim management or enforced enrollment standards for these programs. Without taking these required steps, OHS leaves children vulnerable to low quality services and jeopardizes their school readiness. Further, it exposes federal Head Start funds to potential waste.

Abbreviations

ACF Administration for Children and Families

CLASS® Classroom Assessment Scoring System®

COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

OHS Office of Head Start

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 19, 2024

The Honorable Virginia Foxx

Chairwoman

Committee on Education and the Workforce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Tom Cole

House of Representatives

The Honorable Richard Hudson

House of Representatives

Established in 1965, Head Start promotes school readiness by supporting the comprehensive development of children in poverty through education, nutrition, health, social, and related services. Head Start served nearly 800,000 children and families experiencing poverty in school year 2022-2023.[1] The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office of Head Start (OHS) administers Head Start and received $12 billion for the program in fiscal year 2024. As of December 2023, OHS reported providing grant funding to about 1,600 nonprofit, for profit, and governmental organizations (e.g., local school districts) to operate Head Start programs in communities nationwide.[2]

Occasionally, a grant recipient loses its ability to operate a Head Start program because OHS has suspended or terminated its grant for poor performance or the grant recipient has relinquished its grant voluntarily. In those instances, OHS contracts with an organization, known as an interim manager, to run the program temporarily while it seeks a new grant recipient in that community. Since 2000, OHS has used the same contractor to provide interim management services.

Federal law and regulations require OHS to ensure that Head Start programs, including those under interim management, comply with all Head Start requirements. However, in recent years, parents and Head Start staff have raised serious concerns about child safety and the quality of services provided by programs under interim management. You asked us to examine OHS’s oversight of these programs.

In this report, we examine the extent to which OHS monitoring allows it to assess whether programs under interim management meet Head Start standards regarding (1) the quality of services to children, families, and communities; (2) child safety; (3) fiscal management; (4) staffing and staff support; and (5) enrollment.

To address our objectives, we reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations, and agency documentation. This documentation included OHS monitoring reports from the 14 programs under interim management from January 2020 through June 2024, OHS’s 2022-2027 interim management contract, and OHS’s assessments of the contractor’s performance in 2023 and 2024.[3] We interviewed OHS officials who oversee interim management and representatives from the interim manager.[4] We assessed OHS’s oversight and monitoring practices for programs under interim management against Head Start Act requirements, Head Start program performance standards, and OHS monitoring procedures.

In addition, we conducted site visits to three of the 38 Head Start programs OHS’s interim manager operated from the 2018-2019 through 2022-2023 school years. We selected this timeframe to capture the experience of local staff at programs that were recently but no longer operated by the interim manager at the time of our review.[5] During our site visits, we interviewed local program staff who recently worked for the interim manager and representatives from the grant recipient that replaced the interim manager.[6] We also interviewed representatives from four additional grant recipients that replaced the interim manager after the programs transitioned out of interim management between the 2018-2019 and 2022-2023 school years. We selected programs for site visits and interviews to achieve variation in program size (i.e., the number of children served), length of time under interim management, and reason for interim management.

Additional audit steps are described below:

· To assess the extent to which OHS’s monitoring practices at the time of our review allowed it to assess whether programs under interim management met Head Start service quality standards, we reviewed state child care licensing reports that identified violations from 13 of 31 states in which the interim manager operated.[7] These reports covered the most recent 5-year period, from January 2019 through March 2024, which was the date of our initial outreach to states.

· To assess the extent to which OHS monitoring allowed it to assess whether programs under interim management met Head Start child safety standards, we compared records of significant child safety incidents that occurred during interim management in these 13 states to the incident records that OHS provided to us, from August 2019 (the earliest records OHS officials said they had access to) through March 2024, which was the date of our initial outreach to states.[8]

· To assess the extent to which OHS monitoring allowed it to assess whether programs under interim management complied with Head Start enrollment standards, we analyzed OHS monthly enrollment data for all Head Start programs, including those under interim management, from the 2017-18 through 2022-23 school years. Specifically, we compared the percentage of seats filled in Head Start programs under interim management to all other Head Start programs during this time period.[9] We also compared enrollment rates before, during, and after interim management for the 15 Head Start programs that entered interim management 6 months or more after our review period began, and that exited 6 months or more before our review period ended.[10] Finally, we compared the percentage of Head Start seats filled in programs under interim management to the percentage of Head Start grant dollars those programs spent from school years 2017-2018 through 2021-2022. We assessed the reliability of these data by comparing them to other public information, interviewing agency officials, and conducting electronic and manual data testing. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of assessing how the enrollment rates for Head Start programs under interim management compared to those of programs not under interim management and for describing Head Start grant expenditures for programs under interim management.[11]

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

When an existing grant recipient can no longer operate Head Start programming, the Head Start Act authorizes OHS to designate an interim manager to oversee and administer services until OHS is able to identify a new grant recipient from the community.[12] OHS uses an interim manager to administer Head Start services in a community after (1) the existing grant recipient voluntarily relinquishes its Head Start grant, (2) OHS issues a notice of suspension or terminates a grant recipient’s funding, or (3) OHS determines that there are no qualified applicants during an open grant competition in a community.[13]

Over the 6-year period from school years 2017-2018 through 2022-2023 school year, OHS put 33 Head Start and Early Head Start programs under interim management.[14] Most of these programs (26 of 33) entered interim management because the prior grant recipient relinquished its grant.[15]

National Interim Head Start Program Manager

OHS contracts with a third party, which it selects through a competitive process, to provide interim management services nationally.[16] OHS officials told us that, since 2000, OHS has held contract competitions about every 5 years and awarded the national interim management contract to the same entity after each competition.

According to the current contract, the interim manager must assume responsibility for day-to-day operations of each assigned Head Start grant until OHS identifies a replacement grant recipient for the program’s service area through an open competitive grants process. The contract also states that the interim manager must ensure that each program complies with Head Start standards for the duration of interim management. These standards include maintaining community partnerships, ensuring safety, and meeting state licensing requirements, among other things.

Representatives from the interim manager told us that when they assume responsibility for a new Head Start program, they:

· quickly hire local program staff, secure facilities, and obtain state child care licensing to operate facilities;

· assign their own staff, including a site manager and various content-area specialists, to guide local Head Start program staff and oversee their work;

· provide consultants, as needed, to conduct on-site training and provide technical assistance to local staff; and

· centralize administrative functions, including human resources, payroll and accounting, purchasing, and facilities management for all program they operate, among other functions.

Programs under Interim Management

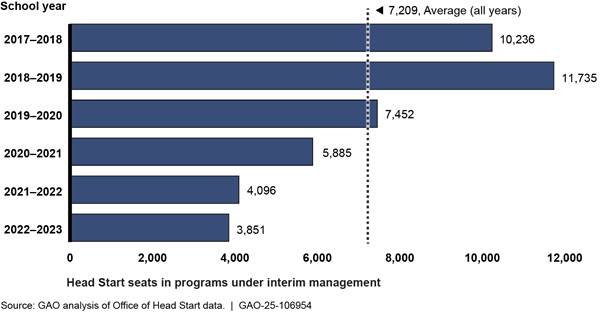

Since 2000, more than 200 Head Start programs across 45 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have been under interim management. In the 6 most recently completed school years at the time of our review (2017-2018 through 2022-2023), these programs offered between 3,851 and 11,735 Head Start seats nationwide (see fig. 1).[17] As of September 2024, there were 18 programs under interim management across 11 states, according to OHS officials.

Notes: Each Head Start and Early Head Start program under interim management is funded to serve a specified number of children per month (its funded enrollment). In this analysis, seats per school year is the sum of all programs’ average monthly funded enrollment from September through May. GAO excluded Migrant and Seasonal Head Start seats from this analysis because these programs do not necessarily follow a traditional school year. GAO also excluded Early Head Start Child Care Partnership program seats, which are offered through partner organizations.

Funding for Interim Management

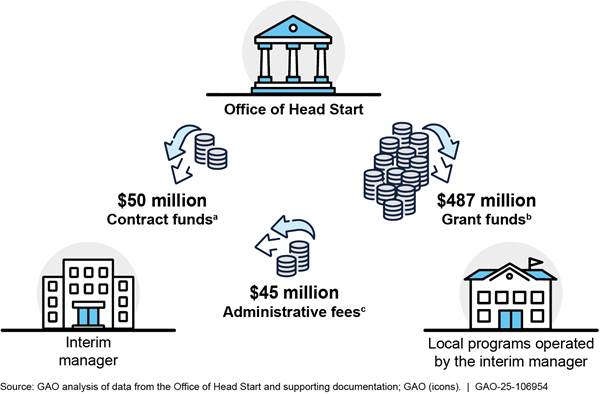

OHS provides two types of funding for interim management. First, it provides contract funds to support the interim manager’s central operations, including its central office staff, consultants, and travel expenses. OHS officials estimated that the interim manager used about $50 million in contract funds for these purposes under its most recently completed 5-year contract (September 2017 through May 2022).[18] Second, OHS provides grant funds for each individual Head Start program under interim management. These funds totaled about $487 million from October 2018 through September 2022. While most grant funds are used to support local program operations, the interim manager reported charging the programs it operated about $45 million in indirect service fees from July 2017 through June 2022 (see fig. 2).[19]

aOHS estimated that its interim manager spent about $50 million in contract funds during its most recent 5-year contract (September 2017 through May 2022) for interim management—the first of three functions included in that contract, which was valued at a total of about $77 million.

bGAO used OHS data to calculate the amount of grant funds, about $487 million, expended by programs under interim management over the 5 federal fiscal years (October 2017 through September 2022) corresponding most closely with the interim manager’s most recent 5-year contract.

cAudited financial statement disclosures indicate that the interim manager charged about $45 million for indirect services it provided to the Head Start programs it operated over its 5 fiscal years (July 2017 through June 2022) that corresponded most closely to its most recently completed 5-year contract. Indirect costs are costs incurred for a common or joint purpose benefitting more than one cost objective and not readily assignable to the cost objectives specifically benefitted. See 200 C.F.R 200.1

OHS Oversight of the Interim Manager

The Head Start Act requires OHS to conduct a full monitoring review of all Head Start programs, including those under interim management, at least once every 3 years.[20] It also requires a review of each new grant recipient immediately after the completion of its first year providing Head Start services.[21] Under law, these reviews must assess how programs (1) address community needs, (2) collaborate with community partners, (3) ensure classroom quality, (4) comply with fiscal requirements, and (5) comply with Head Start eligibility requirements, among other assessments.[22]

In addition, OHS formally reviews the interim manager’s performance under the national interim management contract each year, rating its performance in the areas of (1) quality; (2) schedule; (3) cost control; (4) management; and (5) regulatory compliance.[23] OHS’s two most recent performance reviews rated the interim manager’s performance as satisfactory, very good, or excellent in all performance areas.[24]

OHS Monitoring Has Not Been Adequate to Assess the Quality of Head Start Services during Interim Management

OHS Has Not Conducted Required Monitoring of all Head Start Programs under Interim Management to Ensure Service Quality

OHS has not monitored all Head Start programs under interim management, although the Head Start Act requires monitoring reviews, including risk-based assessments, for all Head Start programs at least once every three years.[25] When OHS conducts monitoring reviews, it assesses the quality of services provided to children and their families and communities. OHS officials and representatives from the interim manager told us that Head Start programs that enter interim management may be at high risk for poor performance due to the circumstances that necessitated interim management, such as multiple uncorrected deficiencies on prior monitoring reviews or financial distress. OHS officials told us that prior to January 2020 they conducted pared down versions of OHS’s typical monitoring protocol for a subset of programs under interim management.[26]

OHS officials told us that since January 2020, it has been standard practice to monitor all programs after 1 year under interim management. However, OHS data showed that they reviewed half of the programs meeting that criterion (14 of 28) from January 2020 through June 2024.[27] OHS officials told us the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted their monitoring for programs under interim management; however, OHS officials told us they conducted monitoring reviews for about 96 percent of other programs during the pandemic.

OHS data show that seven of the 14 programs under interim management it monitored did not comply with one or more federal Head Start performance standards. Four of these programs did not comply with standards related to (1) the quality of services to children and (2) family and community engagement.[28] By not monitoring all Head Start programs after one year of interim management, in line with its standard practices, OHS likely missed important information typically gathered to assess the quality of services offered to children and their families and communities, leaving OHS vulnerable to unidentified service quality concerns. Through our analysis of OHS documents, state child care licensing reports, and interviews with local staff, we identified various issues related to (1) the quality of services to children and (2) family and community engagement.

Quality of Services to Children

According to OHS’s monitoring protocols, OHS assesses the quality of services provided to children by reviewing how the program maintains qualified and competent staff and prepares children for school, among other things. OHS found that four of the 14 programs under interim management it monitored did not comply with one or more child service quality requirements—resulting in eight total areas of noncompliance across these programs. For example, it found that one program did not implement a required staff coaching strategy, and another did not implement a systematic approach to staff training and professional development. Further, it found that one program did not have appropriate school readiness goals for children, and that another did not use data on children’s strengths and needs to support individualized learning.

We also reviewed monitoring and inspection reports from state child care licensing agencies in 13 states in which OHS’s interim manager operated at least one program during the most recent 5-year period available at the time of our review (January 2019 through March 2024).[29] Agencies in 8 of the 13 states found that staff in programs under interim management did not meet minimum qualifications or had not passed background checks. In 5 of these 8 states, agencies found that programs under interim management did not complete or had not documented required background checks for staff.[30] Five state agencies also found that staff were not trained in CPR-First Aid, disease prevention, emergency preparedness, or other required areas.[31] Two state agencies found that center directors were not certified in early childhood education, as was required in those states.[32] Finally, two state agencies found that teachers were not properly trained in entry-level child care.[33]

Representatives from the interim manager told us that they made every effort to ensure that staff met minimum Head Start and state qualification requirements and acknowledged that state child care licensing reviews had identified some administrative errors. They also acknowledged the possibility that, while they expected staff to follow policies and procedures and took steps to mitigate the risk of errors and noncompliance, staff members may have been delinquent at times in completing required trainings or maintaining required credentials.[34] They also told us that they have strengthened their hiring protocols, including putting safeguards in place in their hiring software, to minimize the risk of hiring someone before completing all required background checks.

Local management at all three Head Start programs we visited including one of the 14 programs monitored under interim management, shared concerns about the quality of educational services provided to children, in large part because of unqualified staff. For example, managers at each program said unqualified staff were put in classrooms to teach children.[35] Staff at one program noted that non-teaching staff were routinely sent into classrooms to substitute teach.[36] In addition, staff from another program told us the local program director had no background in early childhood education, as required by that state’s childcare licensing standards and did not recognize or respond appropriately to concerning behavior by some teaching staff as a result.[37]

Representatives from the interim manager said that at one program we visited, they sought approval for and obtained waivers from OHS to rehire teachers who would not otherwise meet minimum Head Start educational requirements.[38] They also stated that when they determine that a staff person does not meet minimum qualifications, they may demote, terminate, or place the staff person on a professional development plan to obtain the required qualification.

Representatives from five of seven new grant recipients we spoke to told us they were unable to rehire some staff who worked for the interim manager because they were unqualified or had to move them into different positions for which they were qualified. Representatives from one program said local staff whose education credential requirements had been waived under interim management were surprised that they could not simply be given another waiver during the hiring process.

Family and Community Engagement

According to OHS’s monitoring protocols, OHS assesses required family and community engagement services by reviewing how programs set and work toward family-driven goals and build community partnerships that meet family needs, among other things.[39] OHS identified an area of noncompliance related to family and community engagement in one of the 14 programs it monitored during interim management. Specifically, OHS found that the program had not offered individualized family services to over half of families at this program, as required.[40]

Local management at one program we visited—which was not among the 14 that OHS monitored—also told us they did not work with families to set and achieve individualized goals when their program was under interim management because the interim manager’s staff instructed them to prioritize other activities.[41] Local staff said they were later told to make something up quickly so that their reports for OHS appeared to meet requirements.[42] Local staff said that this approach prevented them from helping families address their individual challenges.

Local management from two programs we visited also expressed concerns about damaged community relationships during interim management. For example, they said their program’s relationship with a school district deteriorated after a Head Start classroom the district hosted rent-free sat empty for a year with no communication from the interim manager.[43] Staff from the same program told us the interim manager took months to acknowledge and return forms needed to accept a state grant award that funded a classroom in a local school district. As a result, they said that the classroom operated at partial capacity for two months, when it was intended to be a full-year program.[44]

Moreover, representatives from four of the seven new grant recipients we spoke to stated that they had to work to rebuild relationships with the community and local partners after interim management. Representatives from one program said some families lost access to services because community partners had left the program. Representatives from another program told us they were still working to restore community faith in Head Start to educate their children.

Representatives from the interim manager described their family engagement processes as establishing trusting relationships with parents. They further noted that respecting parents’ decisions to enter the family goal setting process on their own timeline can delay establishing family goals and described positive family engagement experiences at two programs we visited. They also said that they want to do everything possible to make the next grant recipient successful, and they understand that community partnerships are very important.

OHS Has Not Assessed Classroom Quality in Programs Under Interim Management

Although the Head Start Act requires OHS to assess the quality of Head Start classrooms using a valid and reliable research-based observational instrument that assesses classroom quality—a separate process from regular onsite monitoring—OHS officials said they had never conducted this type of assessment for any program under interim management.[45] OHS officials said they conducted these assessments—known as Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS)® assessments—for all other grant recipients during each 5-year grant cycle, typically after the first year. CLASS® assessments evaluate the quality of classroom organization and emotional and instructional support that teachers provide to children. As a part of these reviews, OHS assesses teacher-child interactions, which are closely linked to positive child development and academic achievement, according to OHS guidance.

OHS officials told us that they have not conducted CLASS® assessments for programs under interim management because interim management is intended to be short-term. However, we found that 64 of the 73 programs that entered and exited interim management between 2013 and 2023 were in that status for a year or more. Further, our analysis found that 15 of the 73 programs, about one in five, were under interim management for more than 3 years—longer than many children’s entire time in Head Start and within OHS’s stated typical timeframe for assessing classroom quality at other Head Start programs.[46]

During our site visits, local managers at two of the three programs we visited told us about classroom quality concerns that OHS may have identified if it had conducted CLASS® assessments for programs under interim management. They described classrooms that were unstructured and unpredictable, and staff who were unable to provide adequate emotional and instructional support to children.[47] For example, local managers told us these programs relied heavily on substitute teachers to staff classrooms during interim management, which affected children’s ability to form stable relationships with their teachers. In one program, staff said non-Spanish speaking substitute teachers were assigned to classrooms heavily populated with children from Spanish-speaking families. The former center director said the children did not know or recognize their teachers and often could not communicate with them.

Representatives from the interim manager said they provide training and technical assistance to local staff to ensure that children receive a quality education, and they incorporate appropriate practices to address language and cultural diversity in the programs they operate. They also said that they implemented coaching and training plans in the three programs we visited to assist teachers that were struggling to maintain positive learning environments and help strengthen school readiness. At two programs, they said they employed coaches who were certified CLASS® observers. In addition, representatives from the interim manager noted that workforce and staffing challenges exist across the early childhood education sector, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Without reviewing classroom quality itself at programs under interim management, as required by the Head Start Act, OHS may not be well positioned to identify and address classroom quality issues in a timely manner. Absent such assessments, any issues may persist without being identified throughout a child’s entire Head Start education. Poor classroom quality diminishes the program’s benefits for children and may hinder their school readiness.

OHS Has Not Adequately Assessed Compliance with Child Safety Incident Reporting and Facility Safety Standards at Programs under Interim Management

OHS Has Not Taken Adequate Steps to Verify the Completeness of Child Safety Incident Reporting in Programs under Interim Management

We found that OHS has not taken adequate steps to assess whether all significant child safety incidents were reported during interim management, as required by Head Start performance standards and OHS guidance.[48] Significant child safety incidents include those in which a child is left unsupervised, subjected to inappropriate discipline or potential abuse, injured, or released to an unauthorized adult. OHS guidance emphasizes that Head Start programs should not wait for local or state investigations to be completed before reporting to OHS. While OHS is responsible for ensuring that all programs comply with child safety reporting requirements, OHS staff who oversee the interim manager stated that they did not record incidents that the interim manager reported to OHS via email or phone until August 2023. These officials stated that before August 2023, each OHS regional office had its own tracking system for incidents reported by other Head Start programs.

While OHS officials stated that OHS updated its centralized data system to enable programs to submit incident reports directly, we found that OHS has taken limited steps to ensure that this reporting is complete.[49] Specifically, OHS officials said they may review a sample of publicly posted state licensing reports when conducting a formal monitoring review, such as those that have been conducted for some programs under interim management. However, officials said they would not request licensing reports in states where they were not public.

OHS’s limited verification practices may leave it unaware of state-cited child safety violations at programs under interim management, such as those we identified in our review of monitoring and licensing reports from 13 states. State licensing agencies we contacted provided records of 15 significant child safety violations at programs under interim management from August 2019 through March 2024. OHS officials identified nine of these 15 incidents in their emails and their newly centralized data system.[50] The other six incidents were unaccounted for in OHS’s records.[51]

Other gaps in OHS’s oversight of programs under interim management may also leave OHS vulnerable to lapses in child safety incident reporting. OHS officials told us that they have occasionally conducted informal non-monitoring visits to programs under interim management to observe how the programs are operating. However, officials told us that on these visits they sought feedback from local staff with their interim management supervisors present.[52] While OHS documentation indicates that local staff shared positive feedback, workers may be less likely to disclose concerns, including failure to report child safety incidents, in front of their supervisors.

Local staff at all three Head Start programs we visited told us they were prohibited from communicating directly with OHS or state licensing officials to share child safety and other concerns during interim management.[53] Local staff at two of the three programs said significant child safety incidents were not reported to OHS during interim management.[54] For example, one former center director described witnessing a teacher grab a child by the hood of their coat and slam them to the ground. The former center director told us that the interim program director instructed them to not report the incident or fire the teacher.[55] The former center director told us that after that incident, they invented reasons to visit that teacher’s classroom and peer through the window to ensure that children were safe.

Representatives from the interim manager told us that their handbook specifies that any staff member who has reasonable cause to know or suspect that a significant incident occurred has an individual responsibility to report the incident, or ensure a report is made. They also noted that it is possible that their staff or child care partners may not have fully complied with the interim manager’s policies and procedures for reporting known or suspected child safety incidents.[56] Similarly, OHS officials told us that, while they had procedures for programs to report incidents, it would be difficult to ensure that every single incident is reported.

However, OHS will be less able to ensure that children are safe while attending Head Start programs under interim management without more robust efforts to verify that all significant child safety incidents that occur at these programs are reported.

OHS Has Not Taken Adequate Steps to Assess Whether Facility Hazards are Identified and Addressed during Interim Management

We found that OHS has taken limited steps to assess whether Head Start facilities in programs under interim management were safe, as required by the Head Start Act and regulation.[57] OHS officials told us that they have relied on the interim manager to visually assess facilities when it begins operating a Head Start program.[58] Officials said that with OHS’s approval, the interim manager then completes repairs it determines are needed to meet state child care licensing requirements. After the initial visual assessment and any repairs, the interim manager is responsible for conducting ongoing assessments to ensure that facilities continue to meet state and federal health and safety standards during interim management, according to OHS officials. Officials said they become aware of needed repairs when the interim manager requests additional project funds, and they have granted those funds on numerous occasions. In general, OHS officials said they have relied on the interim manager to inform them of facility conditions and the status of improvement projects via monthly meetings.

OHS officials told us that the agency’s monitoring reviews presented an opportunity for them to directly assess the conditions of facilities that, according to representatives of the interim manager, are sometimes in disrepair when OHS assigns them to interim management.[59] However, OHS has not conducted an onsite assessment of the physical conditions of all facilities used by programs under interim management nor has it routinely reviewed state licensing reports related to these facilities.[60]

Local staff from two of the three Head Start programs we visited expressed concerns about facility conditions during interim management. For example, local staff told us that after the heating system broke at one Head Start center, plug-in heat lamps were hung from the wall with the electrical cords taped down and shelving units moved in front of the electrical outlets.[61] Local staff said that they unplugged the heaters overnight to prevent fires, and that this temporary solution violated state child care licensing standards. In another incident, local staff told us that after a teacher reported observing a child picking mold out from under peeling baseboards in a classroom, the baseboards were reaffixed using double-sided tape and the mold was not remediated.[62] Representatives from the new grant recipient told us they later had to replace an entire wall to remediate mold in that classroom, among many other costly renovations (see fig. 3). They told us they were still working to obtain a child care license for this center nearly a year and half later due to its extensive facility hazards.

A former local center director at a second program we visited told us the interim manager instructed her not to inform parents that environmental testing had revealed mold in two classrooms, even though children and staff had developed respiratory symptoms, and one child had a known allergy to mold.[63] The state licensing agency later cited the interim manager for failing to notify parents and the state of the mold and allergen exposure, among other issues.[64]

Representatives from the interim manager stated that they were committed to addressing all known facility hazards at programs that OHS assigned to interim management. They further noted that it was common for them to identify additional issues over time that were not apparent at their initial visual assessment—for example, plumbing, electrical, or heating system issues—and that they work to resolve issues as they arise.

Without procedures to more fully assess whether facility hazards have been identified and addressed in Head Start programs under interim management, OHS will continue to have an incomplete picture of the interim manager’s performance in this area. OHS also may be unaware of instances where children are exposed to serious health and safety hazards in Head Start facilities during interim management.

OHS Has Not Monitored Fiscal Management of Head Start Programs under Interim Management, Leaving the Programs Vulnerable to Waste

OHS has not included fiscal management of grant funds in formal monitoring reviews for programs under interim management, despite requirements in the Head Start Act and in its own monitoring procedures.[65] OHS fulfills this requirement for all other Head Start programs through its formal monitoring by evaluating each grant recipient’s systems for maintaining financial records, safeguarding federal funds, and preventing theft, fraud, waste, and abuse.

OHS officials told us they did not need to assess the fiscal management of grant funds during monitoring visits to programs under interim management because the grant funds were administered at the interim manager’s central contract office and OHS assessed the interim manager’s performance as a contractor.[66] However, the interim manager’s fiscal management of grant funds is not included in OHS’s annual contract performance review, even though these functions are a core part of the interim manager’s contract responsibilities. Without fiscal monitoring, OHS has had little visibility into financial management practices in programs under interim management, hindering its ability to assess these programs’ performance and leaving them vulnerable to inefficient use or waste of taxpayer funds.

Local staff in all three Head Start programs we visited described concerns about fiscal practices during interim management. In one program, for example, staff described costly and potentially unnecessary equipment purchases, including at least 50 tablets that sat unused in boxes for the duration of interim management and playground canopies that did not shade intended areas, were not rated to withstand heavy snowfall, and later had to be removed for safety reasons.[67] At the same time, local staff at this program said trash sat uncollected at two centers for over a month due to what the interim manager described as a miscommunication.

At a second program we visited, local staff said the interim manager failed to effectively negotiate lease terms with the former Head Start grant recipient, agreeing to pay rent that was more than four times what the current grant recipient paid for classroom space in the local area. One local staff person described carefully scrutinizing invoices and urging the interim manager’s staff to contest charges. This staff person told us they insisted that the program solicit additional bids rather than accept the landlord’s quote for food service, which the staff person said ultimately saved the program nearly a million dollars per year.

Finally, in the third program we visited, local staff said that while the interim manager centrally handled all purchasing for the program, needed supplies often did not arrive in a timely manner. As a result, they said the program frequently ran out of diapers, baby wipes, soap, and other essentials. Staff said teachers purchased these items with their own money.[68] Further, several former teachers told us they were never repaid for some expenses despite filing multiple reimbursement claims.

Representatives from the interim manager told us that programs are often assigned to interim management because of financial mismanagement on the part of the prior grant recipient. Further, they said that interim management carries additional challenges, including negotiating leases for limited periods and renegotiating vendor agreements. They also said they maintained regular communication with OHS regarding potential rental costs, which may have differed from those of the previous operator. They further stated that they negotiated with landlords or identified alternative spaces when rental costs appeared to exceed market rates.

The Head Start Act and OHS monitoring procedures require OHS to monitor the fiscal management of grant funds for programs under interim management. The challenges that lead Head Start programs to interim management and that these programs may face during interim management further emphasize the need for OHS to conduct regular fiscal monitoring to guard against wasteful spending.

OHS Did Not Monitor Staff Support Practices in Programs under Interim Management, Leaving it Unaware of Concerns about Poor Work Environments

OHS did not assess staffing and staff support practices for programs under interim management up to and in fiscal year 2024, although its monitoring protocol for its most recent onsite monitoring reviews of Head Start programs called for an assessment of performance in this area. In guidance to Head Start grant recipients, OHS emphasized the importance of supporting the Head Start workforce, noting that Head Start staff who are under frequent stress due to a negative work environment may provide lower quality care to children. OHS began assessing how well programs support their staff (e.g., by establishing a positive work environment) through its onsite monitoring reviews in fiscal year 2024. However, we found that OHS omitted this assessment when it monitored programs under interim management.

When we raised this omission, OHS officials told us it was an error, and that they planned to include a review of staffing and staff supports in future fiscal year 2025 monitoring reviews. OHS officials also told us they sought feedback from staff during occasional non-monitoring visits to Head Start programs under interim management. However, they stated that they spoke with staff in front of interim management supervisors.[69]

Representatives from the interim manager told us that they were committed to a positive work environment and that they provided multiple avenues for staff to report concerns in the workplace. They said that they investigated reported allegations of discrimination, sexual harassment, bullying, or belittling of staff and took corrective action as appropriate. Further, they said that many local staff previously worked under the prior grant recipient, which may have had a different work culture. Representatives said that in some cases, communities and staff have been upset about OHS’s decision to place a program in interim management, which has harmed staff’s perception of the interim manager as an employer.

Local program staff told us they did not have the opportunity to provide independent feedback about the interim manager to OHS. In our own interviews without interim management supervisors present, local staff in all three Head Start programs we visited shared concerns about the work environment and support they received during interim management.

Workloads. Local staff from all three programs we visited told us they were required to work long hours during interim management, often covering other positions during the day and carrying out their regular duties at night and on the weekends. Staff from one program said they worked 12-hour days for weeks on end, while the interim manager’s consultants visited the program for about a week at a time. Local staff said that they would spend days educating new consultants about their program and state requirements one week and then repeat the exercise with new consultants the following week. Staff said this pattern led to extremely long work hours that took a toll on their well-being and their families.

Workplace culture. Staff from all three programs said the workplace was not supportive, and their jobs became more stressful during interim management. Staff in one program said they were routinely demeaned and belittled by the interim manager’s staff and consultants, who they said gossiped about their appearances and required them to valet their cars. One local staff person described being proselytized by the interim manager’s site supervisor. Another said a consultant repeatedly made inappropriate sexual comments to her. Finally, staff from two programs said the interim manager’s staff were hyper-focused on preparing them for a possible monitoring visit from OHS, with one saying that the interim manager’s supervisors required them to craft, revise, and memorize false or misleading scripts to recite in case of a monitoring visit.

Support Networks. Staff from all three programs said the interim manager’s staff forbade them from speaking with OHS officials and state child care licensing agency representatives. In one case, staff said they were forbidden to talk with their own community partners. Staff said this directive left them unable to relay safety and other concerns to regulators and deprived them of support networks that had been available to them prior to interim management. In all three programs we visited, local staff described feeling isolated, micromanaged, and treated poorly by the interim manager’s staff and consultants.

Representatives from the interim manager told us that they provided local staff with training and technical assistance from Head Start content area experts, including training on Head Start requirements and early childhood education. Further, they said that local staff had opportunities to engage in external training and development, including participating in state and regional training and technical assistance, as well as regional and national Head Start conferences.

In guidance to its Head Start grant recipients, OHS has stated that staff wellness is vital to child well-being, a key goal of the Head Start program. Without consistently assessing staff wellbeing in its monitoring reviews in a way that allows staff to speak freely, OHS will continue to risk being unaware of and unable to address any unhealthy work environment issues that may diminish program quality.

OHS Has Not Enforced Head Start Enrollment Standards for Programs under Interim Management

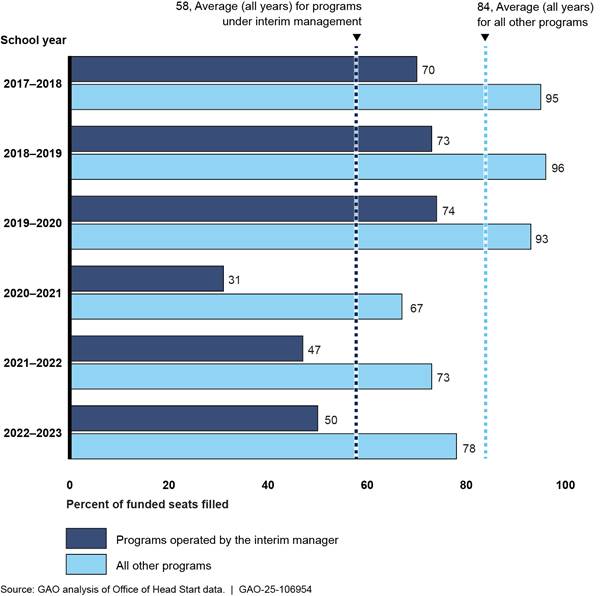

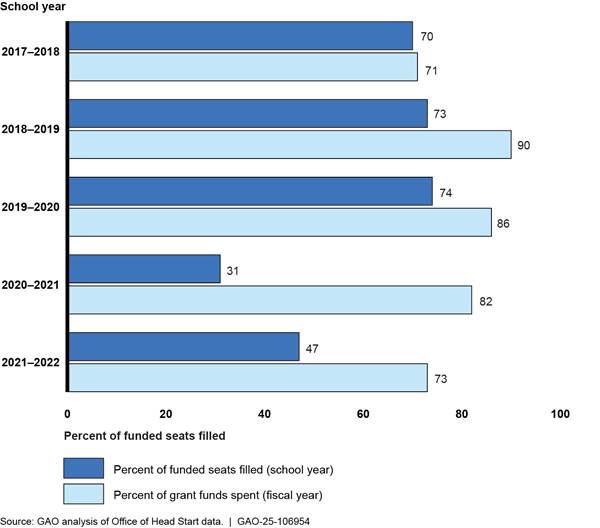

OHS officials told us that the agency has never enforced enrollment standards for programs under interim management, as it has for all other programs, despite consistently low enrollment.[70] The Head Start Act requires that all programs maintain full enrollment, without an exception for programs under interim management.[71] However, we found that, on average, these programs filled fewer Head Start seats than other programs, on average. Our analysis of OHS enrollment data shows that the interim manager filled between 19 and 36 percentage points fewer Head Start seats than all other programs over our 6-year review period (see fig. 4). For example, during the 2022-2023 school year, 50 percent of the nearly 4,000 Head Start seats in interim management sat empty compared to 22 percent for other programs.[72]

Note: Each Head Start and Early Head Start program is funded to serve a specified number of children (its funded enrollment). In this analysis, both for programs operated by the interim manager and for all other programs, the percentage of funded seats filled for each school year represents the average of all programs’ monthly actual enrollment divided by funded enrollment from September through May. GAO excluded Migrant and Seasonal Head Start seats from this analysis because these programs do not necessarily follow a traditional school year. GAO also excluded Early Head Start Child Care Partnership program seats, which are offered through partner organizations.

Further, while OHS can recapture, withhold, or reduce funding from programs that fail to improve enrollment, officials said they had never taken these actions with the interim manager.[73] OHS officials said they sometimes lowered enrollment targets for the interim manager without reducing its funding. OHS officials said they did so because they wanted to ensure that those funds were available to the next grant recipient. However, OHS officials also told us that the agency’s future grantmaking opportunities were not dependent on the amount of funding the interim manager received.

Representatives from the interim manager told us that during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, as in many Head Start programs, a lack of qualified applicants to fill program vacancies adversely affected their ability to achieve full enrollment in some programs. In addition, they said that increased remote and work from home positions lead to a decrease in the early childhood education workforce overall and that Head Start programs competed with public school districts for the same staff. Representatives from the interim manager stated that they have worked with OHS to reduce their funded enrollment in cases in which they were unable to meet full enrollment due to long-term staffing challenges. In these cases, representatives noted that they reallocated available funds toward staff recruitment and retention strategies, such as wage increases, or toward general program improvements. Further, they said that they have returned any remaining funds to OHS.

However, during the most recently completed interim management contract (September 2017 through May 2022), we found that the proportion of grant funds the interim manager spent exceeded the proportion of Head Start seats it filled. For example, in fiscal year 2022, the interim manager spent more than $45 million in Head Start grant funds, 72 percent of its total award, while it filled 47 percent of seats (see fig. 5).[74]

Note: Each Head Start and Early Head Start program is funded to serve a specified number of children (its funded enrollment). In this analysis, for both programs operated by the interim manager and for all other programs, the percentage of funded seats filled for each school year represents the average of all programs’ monthly actual enrollment divided by funded enrollment from September through May. GAO excluded Migrant and Seasonal Head Start seats from this analysis because programs do not necessarily follow a traditional school year. GAO also excluded Early Head Start Child Care Partnership programs, which are offered through partner organizations.

OHS officials told us that they had not held the interim manager accountable for low enrollment because it was not reasonable to expect normal enrollment levels to resume after an incident or situation that resulted in the interim manager’s deployment. Further, they noted that the interim manager operated Head Start programs with a history of low enrollment. Representatives from the interim manager told us that programs were often underenrolled, understaffed, and underfunded when they were assigned to interim management and that it worked to achieve full enrollment by targeting eligible families in the community.

However, local staff from all three programs we visited told us that they believed low enrollment while under interim management was, at least in part, a result of the interim manager’s actions. For instance, staff from one program told us that after the interim manager changed the program’s phone system to a cell phone carrier that had poor service in the program area, families could not reach local staff to enroll their children. In another program, staff said the school day was shortened to end at 2:30 pm, which was not practical for working families. Representatives from the interim manager told us that they collaborated with OHS to determine what changes to program structure would best prepare the program for long-term success.

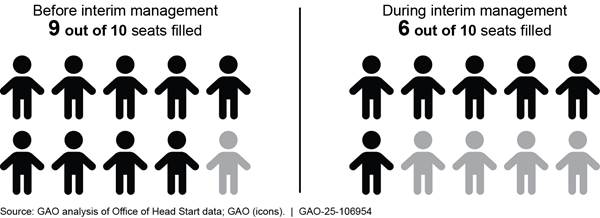

We found that enrollment fell during interim management in all 15 programs the interim manager operated within our review period (March 2018 to December 2022).[75] Among these programs, enrollment was an average of 32 percentage points lower under interim management compared to the preceding 6-month period (see fig. 6).[76] Five of these programs filled fewer than 40 percent of seats—less than half the average percentage of seats filled at other Head Start programs during the same period. Further, while enrollment fell across all Head Start programs during the COVID-19 pandemic, enrollment in these 15 programs fell further—and to lower absolute levels—than in all other programs.

Note: GAO analyzed enrollment data for 15 programs that entered and exited interim management between March 2018 and December 2022 because it enabled us to examine enrollment 6 months before, the entire time in, and the 6 months after interim management using enrollment data provided by OHS. GAO excluded Migrant and Seasonal Head Start seats from this analysis because these programs do not necessarily follow a traditional school year. GAO also excluded Early Head Start Child Care Partnership program seats, which are offered through partner organizations.

In addition, our analysis of OHS enrollment data found that low enrollment continued to be a challenge for programs after they transitioned out of interim management. We found that 14 out of these 15 programs had lower enrollment in the 6 months following interim management than during the 6 months prior to interim management. Among these programs, enrollment declined by an average of 36 percentage points between the 6 months before interim management and the 6 months after interim management.

Representatives from two of the seven post-interim management programs we interviewed told us that they were formally cited by OHS for failing to reach full enrollment in the months following their exit from interim management. Representatives from one of these programs told us they could not obtain child care licenses for the buildings it operated due to the condition in which the interim manager had left them. As a result, they could not enroll children to fill the seats in those facilities.

Fully enrolling Head Start programs is essential to achieving Head Start’s goal to prepare vulnerable children for kindergarten. Further, not enforcing enrollment standards—even if it is out of concern that achieving full enrollment may be too difficult, as OHS officials have stated—is inconsistent with the requirements in the Head Start Act. Failing to do so has resulted in reduced numbers of children receiving Head Start services in programs under interim management relative to other Head Start programs.

Conclusions

Head Start provides early childhood education services to children experiencing poverty nationwide. OHS’s interim management program is intended to provide crucial stability to minimize the disruption that children would experience were a Head Start program to permanently close. However, by not consistently monitoring or enforcing all Head Start standards for programs under interim management, OHS has not detected and addressed potentially significant risks—both to children and to Head Start funds. Such risks can carry significant consequences. Children may be harmed, community partnerships may be broken, and trust in the Head Start program may be eroded. Without improved oversight in the areas we reviewed—service quality, child and facility safety, finances, staff supports, and enrollment—OHS lacks reasonable assurance that programs under interim management are achieving Head Start’s goal of educating and preparing eligible children for success in school and life.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following seven recommendations to HHS.

The Secretary of HHS should ensure that OHS conducts formal monitoring reviews for all programs under interim management at the end of the first year, per its stated goal. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of HHS should ensure that OHS assesses the quality of classrooms at programs under interim management at least once every three-year period, as required by the Head Start Act. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of HHS should ensure that OHS updates its monitoring procedures to better ensure that programs under interim management report all child health and safety incidents, as required by the Head Start program performance standards. For example, OHS could obtain incident reports from state licensing agencies, seek feedback from local staff, or obtain other information to verify completeness of incident reporting. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of HHS should ensure that OHS develops written procedures to better ensure that programs under interim management adequately identify and address safety hazards in their Head Start facilities. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of HHS should ensure that OHS includes fiscal monitoring in its routine onsite monitoring reviews of programs under interim management for longer than 1 year. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of HHS should ensure that OHS includes an assessment of staffing and staff supports in routine onsite monitoring reviews of programs under interim management for longer than 1 year. (Recommendation 6)

The Secretary of HHS should ensure that OHS enforces enrollment standards for programs under interim management. (Recommendation 7)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

HHS provided written comments on a draft of this report, which are reproduced in Appendix I. In its comments, HHS concurred with five of the recommendations and did not concur with two of the draft report’s recommendations. HHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

HHS described various actions that it planned to take to implement the five recommendations with which it concurred (Recommendations 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7). Specifically, the agency stated that it intended to make the following efforts:

· Conduct formal monitoring reviews for programs that have been under interim management for 12 months;

· Ensure that programs that have been under interim management for 3 years receive a CLASS® assessment;

· Reinforce with its interim manager the requirement to comply with child safety incident reporting requirements;

· Strengthen and formalize standard operating procedures for programs under interim management to leverage information from a variety of sources to assess facility conditions; and

· Develop an approach to enforcing Head Start enrollment standards in programs under interim management.

HHS did not concur with the draft report’s fifth recommendation that HHS ensure that OHS includes fiscal monitoring in its routine monitoring reviews of programs under interim management for longer than one year consistent with its procedures for all other Head Start programs. In response to the draft report’s recommendation, HHS stated that OHS conducts two types of monitoring reviews for all other Head Start programs: onsite reviews (known as Focus Area 2 reviews) and offsite reviews (known as Focus Area 1 reviews.) While HHS stated that it plans to add a customized review of fiscal infrastructure to its onsite monitoring protocol for programs under interim management, HHS noted that OHS does not conduct offsite reviews for programs under interim management. We agree that, as originally worded, the draft report’s recommendation could be interpreted to suggest that OHS should begin conducting offsite monitoring reviews for programs under interim management. We have modified the recommendation to specifically refer to onsite reviews.

Regarding the draft report’s sixth recommendation that HHS ensure that OHS include an assessment of staffing and staff supports in routine monitoring reviews of programs under interim management for longer than one year, consistent with its procedures for all other Head Start programs, HHS similarly stated that the differences between interim and other programs call for different approaches to monitoring. HHS included a section on staffing and staff support-related performance areas in its onsite monitoring protocols for fiscal year 2024 for all programs not under interim management. However, it did not do so for programs under interim management. The draft report’s recommendation was intended to apply the monitoring protocols related to staffing and staff supports to programs under interim management starting in fiscal year 2025. In its written response, HHS indicated that it plans to do so. However, we have modified the recommendation to specifically refer to onsite reviews.

Additionally, HHS stated that the GAO draft report does not fully reflect all the data, documents, and evidence provided to GAO during the engagement, and provided one example. Specifically, HHS noted that a sentence in the conclusions section described the risks posed to federal funds by not monitoring or enforcing Head Start standards for programs under interim management, when earlier in the draft we recognized that some monitoring of these programs took place. We have clarified this sentence in the final report to note that HHS did not consistently monitor or enforce all Head Start standards for all programs under interim management. HHS also asserted that the draft report mischaracterized Head Start requirements. The draft report described Head Start requirements as stated in law and regulation; as such, we did not make any changes in the final report.

Lastly, in its written comments, HHS stated that programs spend 12 to 18 months under interim management on average, and that it is rare for programs to be under interim management for 3 or more years. Our analysis of the 21 programs that entered interim management in the last 6 school years but were no longer under interim management as of March 2024 found that programs spent an average of 21 months under interim management. When we included 12 additional programs that were still under interim management as of March 2024 in our analysis, we found that almost half (16 of 33) had been under interim management for at least 18 months and a third (11 of 33) had been under interim management for at least 24 months.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7215 or nowickij@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Jacqueline M. Nowicki, Director

Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues

GAO Contact

Jacqueline M. Nowicki, (202) 512-7215 or nowickij@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Ellen Phelps Ranen (Assistant Director), Miranda Richard (Analyst in Charge), Kayla Good, and Kassandra Vaught made key contributions to this report. Also contributing to this report were Mindy Bowman, Breanne Cave, Jebraune Chambers, Linda Keefer, David Lin, John Mingus, Jessica Orr, James Rebbe, Almeta Spencer, Curtia Taylor, and Adam Wendel.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Head Start includes Head Start preschool for children ages 3 to school age; Early Head Start for infants, toddlers, and pregnant women; American Indian and Alaska Native Head Start; and Migrant and Seasonal Head Start.

[2]The Head Start Act refers to these organizations as agencies. We refer to them as grant recipients throughout this report.

[3]OHS officials told us they did not have records of assessments of contract performance prior to 2023.

[4]We also interviewed officials from the U.S. Department of the Interior, which manages some contracting functions on OHS’s behalf. In addition, we interviewed officials from the National Head Start Association.

[5]We did not visit programs that were actively under interim management.

[6]During all three site visits, we conducted group interviews with staff who had held local program management positions with the interim manager, such as program directors, assistant program directors, education managers, and family services managers. We also interviewed individual local staff members, such as teachers and maintenance workers who had worked for the interim manager. At two of the three programs, we interviewed parents whose children had attended Head Start programs during interim management.

[7]State childcare licensing agencies are responsible for inspecting child care programs, such as Head Start programs, to ensure that they meet state standards. We contacted 28 of the 31 licensing agencies for states in which OHS’s interim manager operated at least one Head Start program between January 2019 and March 2024 to request documentation of inspection results that identified violations of state child care licensing requirements or that resulted in corrective actions against programs under interim management. Of these, 13 state agencies provided such requested documentation. Five agencies told us that they did not have a record of licensing violations or corrective actions against programs under interim management. We did not pursue documentation from four state agencies that may have required a fee to complete records requests. Finally, six state agencies did not respond to our request during our audit timeframes. The remaining three state agencies did not have publicly available contact information.

[8]OHS officials told us that they did not have access to records of significant child health and safety incidents from prior to August 2019, due to staff turnover at the agency.

[9]OHS provides Head Start funding based on the number of children a grant recipient intends to serve. Throughout this report, we refer to this funded enrollment level as the program’s number of seats. OHS did not provide monthly enrollment data for June through August because most programs are closed, or partially closed, during the summer months. Thus, we analyzed enrollment data from September through May for each school year in our review period.

[10]We included programs that entered and exited interim management between March 2018 and November 2022 in this analysis. This approach ensured that the 6 months before interim management, the entire time under interim management, and the 6 months after interim management fell within our scope of school years 2017-2018 through 2022-2023.

[11]We assessed OHS’s oversight of Head Start programs under interim management. We did not independently assess whether the interim manager complied with Head Start performance standards or other federal or state legal requirements. In addition, statements made by local officials presented in this report are not intended to imply contractual noncompliance or noncompliance with federal or state legal requirements. During our audit, we obtained documentation of various events that occurred in some Head Start programs under interim management and referred the issues to the HHS Office of the Inspector General for further review. The HHS Office of the Inspector General responded that they shared this information with OHS for awareness and any follow-up action deemed appropriate.

[12]42 U.S.C. § 9836(a)(2).

[13]The period for a Head Start grant is 5 years. Under the Head Start Act, Head Start grant recipients may receive automatic renewal of their grant at the end of that period. Head Start program performance standards state that a Head Start grant recipient must compete for its next 5-year grant award whenever OHS determines that one of seven conditions existed during the current project period (e.g., two or more performance deficiencies; failure to establish and take steps to achieve school readiness goals; or debarment from receiving federal or state funds by another federal or state agency). See 45 C.F.R. § 1304.11. In cases in which these open competitions do not identify a grant recipient for the area, OHS may place the area under interim management.

[14]For the purposes of our analysis, we did not include Migrant and Seasonal Head Start and Early Head Start Child Care Partnership programs because these programs have different requirements than traditional Head Start and Early Head Start programs.

[15]According to OHS officials, in many cases, grant recipients relinquish their grant to avoid having it terminated.

[16]In response to OHS’s most recent solicitation, two entities bid for the contract in 2022. When awarding the contract to the existing interim manager, OHS cited the organization’s understanding of the contract requirements, its more than 20 years of experience, and OHS’s assessment that its risk of unsuccessful performance was very low.

[17]Each Head Start and Early Head Start program under interim management is funded to serve a specified number of children (its funded enrollment).

[18]The 2017-2022 contract had a value of about $77 million. The interim management contractor provides other Head Start-related services, such as consulting outside its interim management role. The current contract, which began in 2022 and ends in 2027, has a value of about $75 million.

[19]Indirect costs are costs incurred for a common or joint purpose benefitting more than one cost objective and not readily assignable to the cost objectives specifically benefitted. See 200 C.F.R § 200.1. OHS officials stated that indirect service fees charged by the interim manager aligned with OMB guidance and ACF grants policy.

[20]42 U.S.C. § 9836a(c)(1)(A).

[21]42 U.S.C. § 9836a(c)(1)(B).

[22]42 U.S.C. § 9836a(c)(2).

[23]According to OHS’s plan to monitor contract quality, OHS representatives meet regularly with the interim manager; review progress reports, invoices, and deliverables; conduct periodic site visits; and hold semi-annual quality assurance meetings with agency leadership, among other monitoring obligations.

[24]If the interim manager fails to meet the required service or performance levels established in the contract, OHS assigns a negative rating for the review period. OHS officials told us that they had never assigned a negative rating for the interim manager’s performance.

[25]The Head Start Act requires that HHS conduct a full review, including the use of a risk-based assessment approach, of each Head Start program at least once during each 3-year period and a review of each newly designated Head Start agency immediately after the completion of the first year such agency carries out a Head Start program. 42 U.S.C. § 9836a(c)(1)(A), (B). There is no exception in the Head Start Act for programs under interim management.

[26]OHS officials said these narrower reviews were focused on child health and safety, classroom operations, and Head Start service delivery. OHS officials provided documentation of one such review the agency conducted in 2010.

[27]OHS officials told us that of the 14 programs that it did not monitor, five were prioritized for transition to long-term grant recipients.

[28]When OHS identifies an area of noncompliance with federal requirements in a Head Start program it monitors, the program must correct the noncompliance within a specified period, typically 120 days.

[29]In March 2024, we contacted state child care licensing agencies in 28 states where the interim manager operated at least one Head Start program since calendar year 2019 to request monitoring or inspection reports and documentation of any state child care licensing violations or corrective actions required of programs under interim management. Thirteen states provided documentation in response to our request.

[30]Before hire, programs must conduct an interview, verify references, conduct a sex offender registry check and obtain one of the following: (1) state or tribal criminal history check including fingerprinting, or (2) FBI criminal history records, including fingerprinting. Programs have 90 days after hire to obtain whichever check they did not complete prior to hire (1 or 2) and a child abuse and neglect state registry check, if available. See 45 C.F.R. § 1302.90(b).

[31]In addition to being required by state child care licensing, these health and safety trainings are required for all Head Start staff who have regular contact with children. See 45 C.F.R. § 1302.47(b)(4)(i).