ILLICIT FINANCE

Treasury Should Monitor Partnerships and Trusts for Future Risks

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106955. For more information, contact Michael E. Clements at (202) 512-8678 or clementsm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106955, a report to congressional committees

Treasury Should Monitor Partnerships and Trusts for Future Risks

Why GAO Did This Study

Illicit actors can use companies and other legal entities to launder criminal proceeds. Entities such as partnerships and trusts offer a degree of anonymity because they can be created without naming the people who benefit from their activities.

The Corporate Transparency Act includes a provision for GAO to review beneficial ownership information requirements for partnerships and trusts. This report describes state requirements for registering partnerships and trusts and collecting beneficial ownership information. It also addresses views of federal law enforcement officials on the benefits of beneficial ownership information for law enforcement, and the illicit use of partnerships and trusts in the financial system and the risks they present.

GAO reviewed registration statutes and documents for the 50 states and the District of Columbia, reports from federal agencies and international organizations, and data from Treasury (FinCEN), the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Department of Homeland Security, and Internal Revenue Service. GAO also conducted a survey of state officials (45 responses), and interviewed federal agency officials, representatives of associations for secretaries of state, trust and business lawyers, and illicit finance experts.

GAO recommends that Treasury use SAR data to periodically analyze the risk of illicit activity related to partnerships and trusts. Treasury agreed with the recommendation.

What GAO Found

States have jurisdiction over formation and reporting requirements for partnerships and trusts operating within their borders. Partnerships and trusts can be used for a range of business purposes, although trusts are more typically used for wealth management. States collect limited information from these entities. They require registration and ownership information only from certain types of partnerships and trusts, and the required information varies by state and entity type. For example, most states do not require general partnerships to register with the state, but generally require other types—such as limited partnerships—to register and provide some partner information.

Law enforcement officials told GAO that some investigations were halted by the inability to determine the beneficial owners of businesses using existing methods. A beneficial owner is an individual who owns 25 percent of an entity or exercises substantial control over its activities. In January 2025, federal law will require certain companies created by filing a document with the secretary of state to submit beneficial ownership information to the Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) registry. The registry is likely to benefit law enforcement investigations, according to Treasury and law enforcement officials. But law enforcement officials said they still may face barriers obtaining information on certain trusts and partnerships not covered under the reporting requirement.

Partnerships and trusts represented a small percentage of entities named in suspicious activity reports (SAR) during 2019–2023, according to GAO’s analysis of available data. SARs are reports that financial institutions must file with FinCEN if they identify potential criminal activity.

The Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 requires FinCEN to periodically report on threat patterns and trends from SARs. Treasury used SAR data in a 2022 report on financial activity of Russian oligarchs. However, it does not periodically analyze SARs for trends in illicit activity related to partnerships and trusts. Treasury stated in 2024 risk assessments that trusts can be misused for tax evasion and fraud, and little is known about them. Although few of these entities have been named in SARs, agency officials and experts told GAO that criminals could exploit registry gaps by creating entities not required to report ownership information. Illicit finance experts have noted this may have happened in the United Kingdom when it began requiring certain ownership information in 2016. By leveraging SAR data, Treasury would be better positioned to promptly identify any increase in illicit activity and target its efforts.

No table of contents entries found.

Abbreviations

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

FBI |

Federal Bureau of Investigation |

|

FinCEN |

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network |

|

HSI |

Homeland Security Investigations |

|

IRS-CI |

Internal Revenue Service-Criminal Investigations Division |

|

LLC |

limited liability company |

|

LLP |

limited liability partnership |

|

LLLP |

limited liability limited partnership |

|

SAR |

suspicious activity report |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 19, 2024

Congressional Committees

Illicit actors often create various types of business entities to launder the proceeds of their crimes because the entities offer a degree of anonymity.[1] Some entities can be created without revealing the identities of their “beneficial owners”—the people who own them or control their activities. The lack of regulation and transparency surrounding these entities makes them attractive to illicit actors, allowing them to conceal their activities or launder money.[2]

To prevent the use of business entities to evade anti-money laundering laws and regulations or conceal other illegal activities, the Corporate Transparency Act was enacted on January 1, 2021, as part of the National Defense Authorization Act.[3] It requires certain business entities to report information about their beneficial owners to the Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) by January 1, 2025.[4]

The Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 includes a provision for us to review state requirements for forming or registering trusts and partnerships and how beneficial ownership information affects law enforcement investigations of illicit finance.[5] This report addresses

1. state requirements for forming and registering partnerships, and the beneficial ownership information on partnerships that states collect;

2. state requirements for forming and registering trusts, and the beneficial ownership information on trusts that states collect;

3. views of federal law enforcement officials on how beneficial ownership information for trusts and partnerships may affect law enforcement investigations of illicit finance; and

4. use of trusts and partnerships for illicit finance in the United States and other industrialized countries, including potential future risks.

For the first and second objectives, we reviewed documentation about registration requirements and collection of ownership information for partnerships and trusts from the websites of secretaries of state (or similar offices) for the 50 states and the District of Columbia.[6] We reviewed relevant laws related to creation and registration requirements for partnerships and trusts.[7] We also sent a web-based survey to secretaries of state (or similar offices) for all 50 states and the District of Columbia on their requirements for forming and registering partnerships and trusts. Forty-four states and the District of Columbia provided responses.[8] In addition, we interviewed officials from Treasury, including, and attorneys with expertise in trust and estate law and business law.[9]

For the third and fourth objectives, we reviewed Treasury risk assessments and strategies related to money laundering and terrorist financing, literature related to the use of entities for illicit finance, and congressional testimony on the use of shell companies in illicit finance. We also interviewed representatives of three state financial regulatory agencies (selected because their trust industries have been implicated in illicit finance) and five financial institutions within those states (selected because they provide trustee services).

For the fourth objective, we reviewed FinCEN data from 2019–2023 on the number of suspicious activity reports (SAR) that involved corporations, limited liability companies, partnerships, trusts, and trust companies. We reviewed similar data on the number of investigations involving these entities from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and Internal Revenue Service-Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI). To obtain these data, we asked agencies to conduct certain keyword searches on their relevant databases.[10] We also reviewed the Financial Action Task Force’s most recent Mutual Evaluation Reports, which include information on beneficial ownership registries, for all 38 member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

In addition, we interviewed officials from (1) the Department of Justice (DOJ), including in the Office for U.S. Attorneys and FBI; (2) Immigration and Customs Enforcement and HSI in DHS; and (3) IRS-CI for perspectives on the usefulness of beneficial ownership information in law enforcement investigations and the use of trusts and partnerships in illicit finance. We also interviewed representatives of two organizations with expertise in illicit finance (Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency Coalition and Transparency International). For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

States historically have had jurisdiction over the formation of and reporting requirements for legal entities typically formed for a business purpose within their boundaries.[11] Statutes and regulatory requirements for formation and registration vary from state to state. Secretaries of state or similar offices generally are responsible for overseeing business formation and registration. States also have jurisdiction over legal arrangements, such as trusts. We discuss state requirements for formation and registration in more detail later in this report.

Types of Legal Entities and Legal Arrangements

Legal entities can take many forms, including the following:

· Corporation: A corporation is a legal entity that acts as a separate and distinct entity from its owners, directors, and officers and has legal rights.[12] A corporation generally offers directors and officers protection from liability for the company’s debts and other obligations. A corporation can be closely held—with one or a small group of shareholders—or publicly held.

· Limited liability company: A limited liability company (LLC) is a type of legal entity that generally offers its owners protection from liability for the company’s debts and other obligations. It may have only one member and be managed by its members or by hired managers.

· Sole proprietorship: A sole proprietorship is an unincorporated business operated by one individual who owns all assets and is responsible for all liabilities. There is no legal distinction between the business and the individual owner-operator of the business.

· Partnership: A partnership is an association of two or more individuals or entities who jointly own and conduct a business and agree to share the profits and losses of the business.

· In a limited liability partnership (LLP), partners are generally protected from the debts, obligations, and liabilities of the partnership. In most states, this liability shield applies regardless of the law giving rise to the claim against the LLP.

· A limited partnership consists of one or more limited partners, who contribute capital to and share in the profits of the partnership but who are responsible for the company’s debts only up to the amount of their contribution, and one or more general partners who control the business and are generally jointly and severally liable for its debts.

· In a limited liability limited partnership, in most circumstances both general and limited partners are not responsible for the partnership’s debts and obligations.

· Trust: A trust is a traditional legal arrangement created when a person known as a settlor or grantor places assets under the control of a trustee for the benefit of one or more individuals (each generally known as a beneficiary) or for a specified purpose. Most trusts are formed under common law.[13] Trusts range from completely passive holders of valuable assets to active business entities. They generally can be divided into two broad categories: personal trusts and business trusts.[14]

· Personal common law trusts, typically used for estate planning and wealth management, are private legal arrangements formed without any state filing (that is, registration).

· Business trusts, which may or may not require a state registration, can be further subdivided between common law business trusts and statutory business trusts.[15]

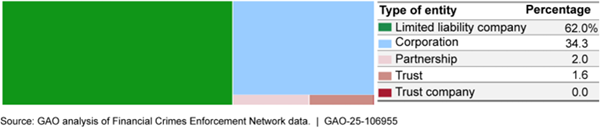

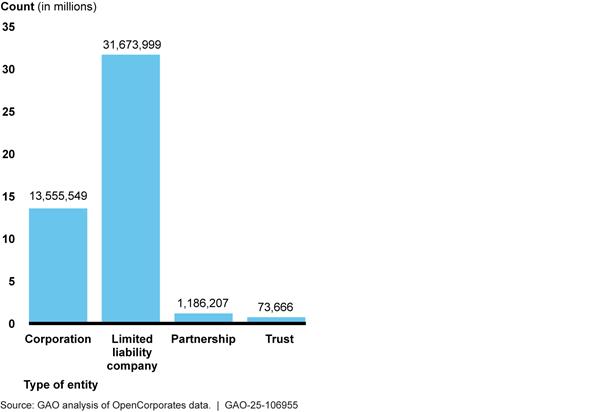

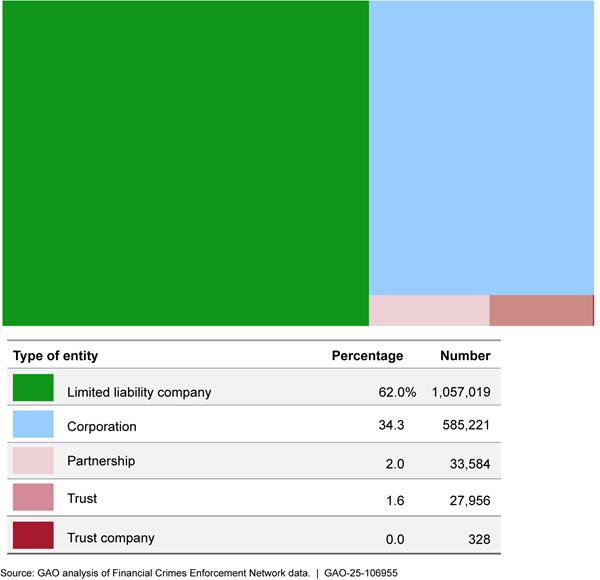

In the United States, corporations and LLCs far outnumber registered trusts and partnerships (see fig. 1). As discussed in this report, personal common law trusts and some types of business entities are not required to register with the state; therefore, the total number of these entities in the United States is unknown.

Note: We used data from OpenCorporates, a third-party aggregator of secretary of state information. Not all states make company status publicly available. We included active and unknown statuses in our analysis.

FinCEN and the Beneficial Ownership Reporting Rule

FinCEN’s mission includes safeguarding the financial system from illicit use, combatting money laundering and its related crimes, and collecting, analyzing, and disseminating financial intelligence. It is the primary federal agency responsible for implementing the Corporate Transparency Act, including rulemaking for several provisions (such as those related to beneficial ownership disclosure requirements).

In September 2022, FinCEN issued a final rule on requirements to report beneficial ownership information.[16] In accordance with the Corporate Transparency Act, the rule defines a beneficial owner as any individual who, directly or indirectly, exercises substantial control over a reporting company or owns or controls at least 25 percent of the ownership interests of a reporting company.

Reporting companies, as defined below, must submit to FinCEN the following information for every individual who is a beneficial owner: owner(s)’ name, date of birth, and address; a unique identifying number from an acceptable identification document; and the name of the jurisdiction that issued the identification document.[17]

· A domestic reporting company is any entity that is a corporation or an LLC or created by the filing of a document with the secretary of state or any similar office under the law of a state or Indian Tribe.

· A foreign reporting company is any entity that is a corporation or an LLC or formed under the law of a foreign country and registered to do business in any state or tribal jurisdiction by the filing of a document with a secretary of state or any similar office under the law of a state or Indian Tribe.

The rule specifically exempts 23 types of entities from reporting (they are not defined as reporting companies for the Corporate Transparency Act). Many of these entities already must report ownership information to a governmental authority under other statutes or regulations. These entities include, but are not limited to, publicly traded companies meeting specified requirements, many tax-exempt organizations, and certain large operating companies.[18]

FinCEN began accepting reports on January 1, 2024. A reporting company created or registered to do business before January 1, 2024, will have until January 1, 2025, to file its initial report.[19]

Role of the Financial Action Task Force

The Financial Action Task Force is a global organization that develops international standards to combat money laundering and terrorist financing. In 2012, it issued its standards, comprising recommendations and interpretive notes, and has regularly updated them since.[20] Additionally, it assesses more than 200 countries against its standards, including for transparency of beneficial ownership, to help those countries prevent illicit use of their financial systems.

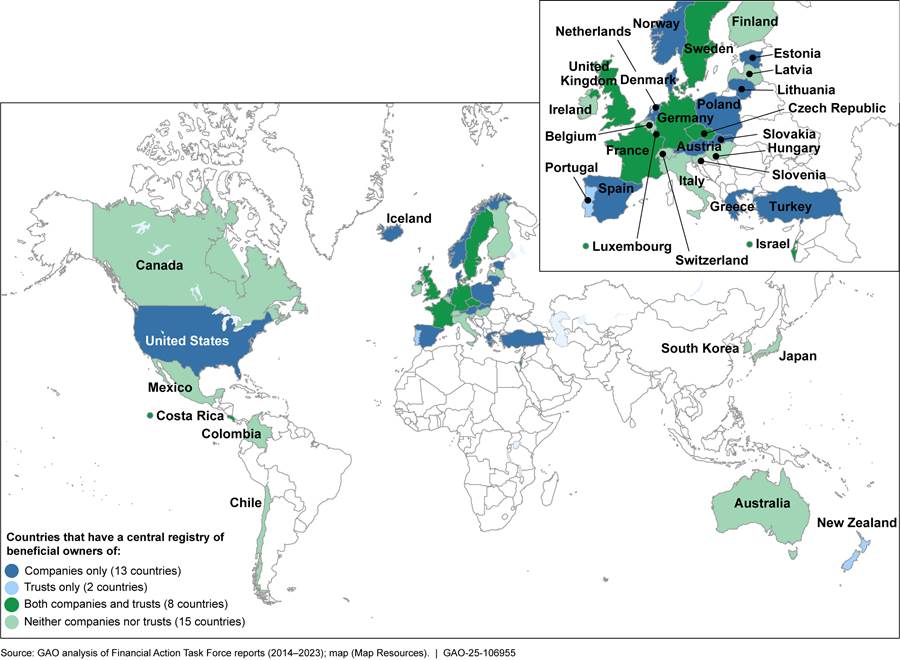

The Financial Action Task Force has recommended that countries ensure the availability of adequate, accurate, and up-to-date information on beneficial ownership of companies and trusts and allow rapid access by appropriate authorities. The task force noted that a central registry can be a tool for accessing this information. Figure 2 shows the countries with beneficial ownership registries as of September 2023.

Note: Trusts, as used here, include legal arrangements similar to trusts (such as the French fiducie). The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s beneficial ownership registry includes certain statutory trusts and business trusts, and existing trust registries in the United Kingdom and New Zealand include trusts that may generate income. We analyzed information from the 38 countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development because most have advanced economies similar to the United States.

States Require Most Types of Partnerships to Register and Provide Some Ownership Information

Few States Require Registration for General Partnerships, but Most States Do So for Other Types of Partnerships

As described earlier, partnerships range in types—general partnerships, limited liability partnerships, limited partnerships, and limited liability limited partnerships. Based on states’ survey responses and our review of registration documents from the 50 states and District of Columbia, states generally do not require general partnerships to register or provide ownership information, but most require limited and limited liability partnerships to register and report certain ownership information. Our review of state statutes indicates that jurisdictions that recognize limited liability limited partnerships generally require those partnerships to register as well. Registration or “filing” typically involves reporting information in documentation such as certificates or statements of qualification.

General partnerships. Most states do not require general partnerships to register after they are formed.[21] Our review of statutes from 51 jurisdictions found that general partnerships most often are formed under common law, which does not require filing a form with the secretary of state or similar office. Of the 45 states that responded to our survey, 12 indicated that general partnerships have the option to register. For example, according to the Kansas Secretary of State’s website, general partnerships in Kansas may choose to register if they want to create a public record of the partnership or ensure the enforcement of contracts and agreements.[22]

However, some states require general partnerships to register for specific purposes. For example, in their responses to our survey, Colorado and Missouri indicated that general partnerships are not required to file with the state unless they use a different trade name instead of the partners’ names to do business.[23]

Limited liability partnerships. According to our analyses of state statutes, each of the 50 jurisdictions that recognize limited liability partnerships (LLP) require them to register.[24] Under the Uniform Partnership Act (2013), a partnership that elects to become an LLP provides partners with limited liability protections, whereas partners would be jointly and severally liable for the obligations of a general partnership, partners of an LLP are generally only liable for their individual contributions to the partnership.[25] To become an LLP, a partnership must first agree to amend its partnership agreement and vote to approve the changes. Following approval, the partnership must file a statement of qualification with the secretary of state or similar office, which includes a statement that the partnership elects to become an LLP.[26]

Limited partnerships. In 50 of the 51 jurisdictions whose statutes we reviewed, limited partnerships must register by filing a certificate with the secretary of state or similar office.[27] According to the Uniform Limited Partnership Act (2013), a limited partnership is formed when at least two persons become partners, one of whom must be a general partner and another a limited partner, and a certificate of limited partnership is filed with the secretary of state or similar office.

Limited liability limited partnerships. Thirty-one of the 51 jurisdictions allow limited partnerships to form as, or later become, a limited liability limited partnership (LLLP) by registering with the secretary of state or similar office, based on our review of state statutes and states’ registration documents.[28] According to the Uniform Limited Partnership Act (2013), LLLPs provide general and limited partners with protection from the partnership’s debts and obligations.[29] These partnerships can only be formed by filing a document with the state. Some states provide limited partnerships the option to elect to be an LLLP on the certificate of limited partnership or another similar registration document. Other states require the partnership to register as or subsequently become an LLLP with a separate document.

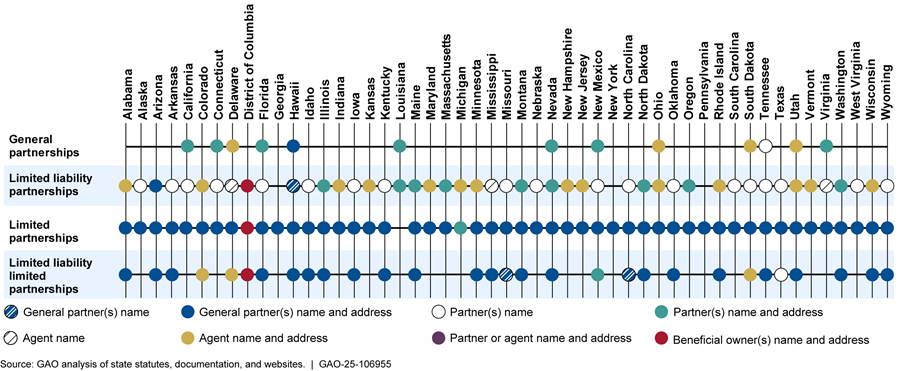

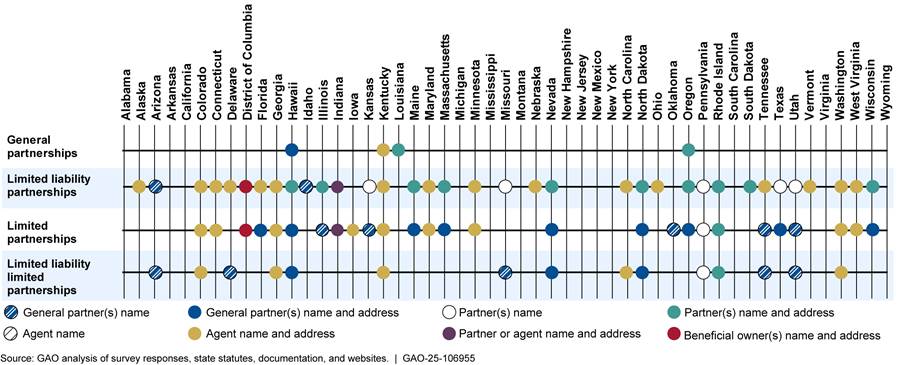

States Commonly Request Information on General Partners but Usually Do Not Specify the Beneficial Owners of Domestic Partnerships

On the basis of our review of registration documents, most states generally require the name and address of at least one general partner, who may be considered a beneficial owner, depending on the partner’s level of ownership or control within a domestic partnership.[30] According to the Uniform Limited Partnership Act (2013), a general partner may be a natural person (an individual) or a nonnatural person (a legal entity such as a limited liability company or similar corporate vehicle).[31] A general partner is a member of a partnership that shares in its profits as well as its liabilities. As discussed above, entities that can be created without revealing the beneficial owner can be attractive to illicit actors who want to conceal activities such as laundering money gained from corruption or other crimes. In some cases—rather than requiring the name of a beneficial owner explicitly—a state may require information for an agent instead, including registered agents that are authorized to accept service of process or other important legal and tax documents on behalf of a business.[32] See figure 3 for more details on information states collect from domestic partnership initial filings.

Figure 3: Ownership and Other Information States Require from Domestic Partnerships at Initial Filing

Notes: Initial filings are documents required to register or form the partnership in the state. Pennsylvania also registers domestic limited liability partnerships and limited liability limited partnerships but information on general partners, beneficial owners, or agents is not required at filing. Limited liability partnerships in Georgia are required to register with the clerk of the superior court of any county in which the LLP has an office, not with a state agency.

See figure 4 for more details on the information states collect from periodic filings (such as annual and biennial reports) of domestic partnerships.

Figure 4: Ownership and Other Information States Require from Domestic Partnerships for Periodic Filings

Note: Periodic filings refer to the regular submission of documents, such as annual and biennial reports, and associated fees. These filings serve to confirm the entity is still active and must be submitted at regular intervals after the initial creation or registration of the entity with the state.

Our review also indicates that, with one exception, the jurisdictions we reviewed do not explicitly request information about a partnership’s beneficial owner(s) on partnership registration and formation documents.[33] That is, 50 jurisdictions do not include the terms “beneficial owner” or “beneficial ownership information” in their documents.[34] The District of Columbia is the sole exception, explicitly requesting the name and address of each beneficial owner in its registration forms. However, our review of filing documents indicates that the District of Columbia’s definition of “beneficial ownership” diverges from the beneficial ownership information reporting rule in two ways. First, it allows legal entities, such as LLCs, to be considered beneficial owners, whereas the reporting rule only recognizes individuals. Second, the District of Columbia sets a 10 percent ownership threshold, whereas the reporting rule uses a 25 percent threshold.

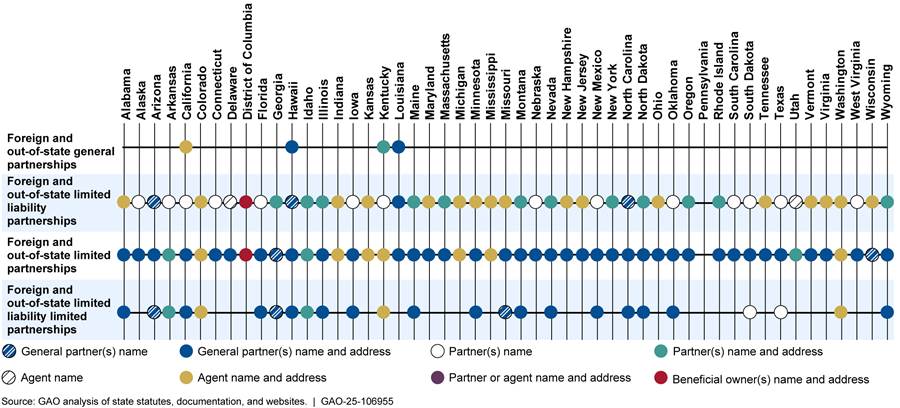

Foreign and Out-of-State Partnerships Have Limited Reporting and Registration Requirements

States generally require limited ownership information from foreign and out-of-state partnerships, according to our survey results and review of filing documents. Moreover, the information required, such as the name and address of a partner or agent, may not pertain to persons considered beneficial owners under the reporting rule.

For partnerships conducting business activities that require registration, most states require at least the name and address of a general partner for foreign and out-of-state limited partnerships and LLLPs. However, they do not specifically require the names of beneficial owners, with the exception of the District of Columbia (see fig. 5). As with domestic LLPs, for foreign and out-of-state LLPs, states generally collect information on a partner who is not necessarily a general partner, or on an agent.

Figure 5: Ownership and Other Information States Require from Foreign and Out-of-State Partnerships for Initial Filings

Note: Initial filings are documents required to register the foreign or out-of-state partnership in the state.

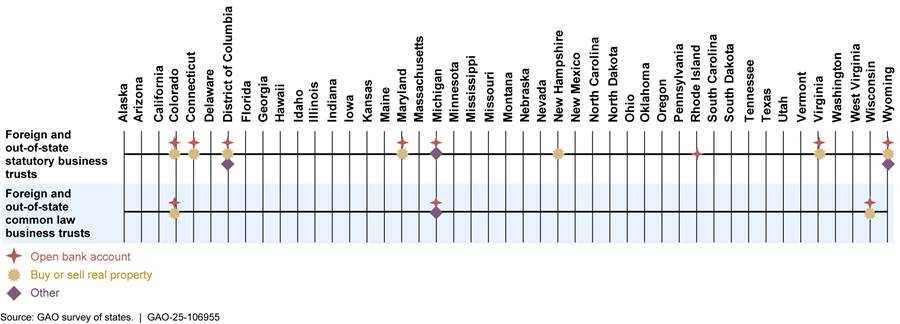

However, 25 of 45 survey respondents reported that their states allow foreign and out-of-state limited partnerships to conduct certain financial activities without registering because the states do not consider these activities to be engaging in business (see fig. 6).[35] Such activities may include opening bank accounts and buying and selling real property.

Figure 6: States in Which Unregistered Foreign and Out-of-State Partnerships Can Engage in Certain Financial Activities

Notes: We surveyed 50 states and the District of Columbia and received 45 responses. Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, and New York did not complete the survey. Such financial activities may include creating mortgages, collecting debts, enforcing debt collection, and engaging in interstate commerce.

Differences in State Laws Affect Which Partnerships Must Report Beneficial Ownership Information to FinCEN

According to FinCEN, states’ registration and filing practices are relevant in determining if an entity is created by filing with the state, and these practices may vary across jurisdictions. FinCEN stated it will consider issuing additional guidance as needed to resolve questions on whether filings under specific circumstances constitute the creation of a new entity. As previously discussed, domestic reporting companies must submit beneficial ownership information to FinCEN. Certain types of partnerships fall neatly into the Corporate Transparency Act’s definition of “reporting company,” but others do not because of varying interpretations of what constitutes “creation” of an entity.

General partnerships: States may require general partnerships to file a document, such as a statement of authority, to register to conduct business in the state; however, that requirement is only administrative. Because the actual formation of a general partnership is done under common law, and a court could find a partnership exists without a statement of authority, a general partnership would not be a reporting company under the Corporate Transparency Act. FinCEN noted in the preamble to the beneficial ownership information reporting rule that general partnerships typically are not reporting companies.

Limited liability partnerships: There may be variation in whether an LLP can be “formed” or “created” at the time of filing a document with the state, depending on the language in state law and the version of the Uniform Partnership Act (2013) adopted, if any. Some state provisions allow a partnership to form as or subsequently become an LLP by filing the proper statement of qualification.[36] Others simply state that a general partnership can become an LLP by filing a statement of qualification.[37] Business law experts we interviewed generally said that an LLP is still a type of general partnership and, therefore, would not be a reporting company.

On the one hand, a partnership cannot have the limited liability protections of an LLP without filing the appropriate document with a state government.[38] On the other hand, a partnership initially can be formed as a general partnership, and the partners can later vote to convert a general partnership into an LLP by registering with the state. Since it is unclear if converting a general partnership into an LLP meets the Corporate Transparency Act’s definition of creation, some LLPs may not be reporting companies.

Limited partnerships: In most states, limited partnerships would be considered reporting companies. To form, a partnership must submit a certificate of limited partnership or similar document to the state’s secretary of state or similar office.[39] Since the entity cannot exist without filing such a form, it would be considered a reporting company.

Limited liability limited partnerships: Similarly, LLLPs also would be considered reporting companies. LLLPs are akin to limited partnerships, but both the general and limited partners are generally only liable for their own contributions to the organization. While states that recognize LLLPs have varying rules for forming them, the process typically involves filing a document (such as a certificate of limited partnership) that either forms the LLLP or allows a limited partnership to become an LLLP.[40]

In either case, an LLLP could be considered a reporting company for the following two reasons. First, a form is required to create the entity, whether it is initially formed as an LLLP or subsequently becomes one. Second, even if a subsequent filing does not constitute “creation” of a new entity, the initial filing of a document as a limited partnership still would have been required, making it likely to be a reporting company under the Corporate Transparency Act.

States Generally Require Only Certain Types of Trusts to Register and Provide Ownership Information

States Do Not Require Common Law Trusts, Which Generally Are Used for Estate Planning, to Register

Common law trusts typically are used to manage a person’s assets, particularly for estate planning purposes, allowing them to bypass the probate process after the settlor’s (creator’s) death. These trusts are private legal arrangements generally formed without any state filing. They do not have beneficial owners as that term is used in the reporting rule. However, under the final rule, trustees, beneficiaries, grantors, or settlors may be deemed to own or control a reporting company held in trust and be determined to be beneficial owners of the reporting company.[41]

Some States Require Common Law Trusts Created to Hold Assets for Business Purposes to Register

Common law business trusts are unincorporated entities created for a business purpose. According to the Uniform Statutory Trust Entity Act (2013), these trusts are also known as “Massachusetts trusts,” or “Massachusetts business trusts.” These trusts are privately created by a document that defines how a trustee must hold and manage property for the benefit and profit of its beneficiaries.

|

Domestic Asset Protection Trusts Domestic asset protection trusts are generally created for asset protection and tax minimization. According to the American College of Trust and Estate Counsel, 20 states allowed these trusts as of August of 2022. They are not formed through state registration, and none of the jurisdictions that allow them and responded to our survey indicated any registration requirements. Unlike traditional common law trusts, domestic asset protection trusts allow the settlor (creator of the trust) to be a beneficiary. In some cases, they allow the settlor to maintain control of the assets. Assets may be shielded from bankruptcy proceedings. Because these trusts deviate from traditional trust law principles, some states have deemed them void and contrary to public policy interests, while other states permit them. Sources: GAO analysis of survey responses and American College of Trust and Estate Counsel and Treasury Office of Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes documents. | GAO‑25‑106955 |

Common law business trusts combine the benefits of a corporation with those of anonymous companies, offering greater flexibility and identity protection.[42] However, business lawyers we interviewed told us that these trusts are rare because they generally have very complex structures and are costly to establish. Our review of state statutes indicates that 18 of the 19 states that recognize domestic common law business trusts require them to register to transact business in the state but not necessarily to form as an entity.

Few States Recognize Statutory Business Trusts

Statutory business trusts are generally created to carry on a profit-making business that could have been carried on through another business entity, like a corporation.[43] According to the Uniform Statutory Trust Entity Act (2013), a statutory trust comes into existence through the filing of a certificate of trust with a public official (a secretary of state or similar office).

Our review of state statutes indicates that nine of the 51 jurisdictions recognize such trusts in statute and require registration by filing a certificate of trust or similar instrument with the secretary of state or similar office.[44]

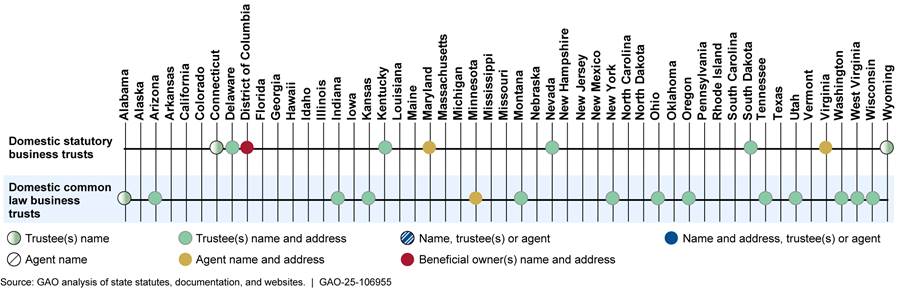

Some States Request Information on Trustees but Not about the Beneficial Owners of Domestic Business Trusts

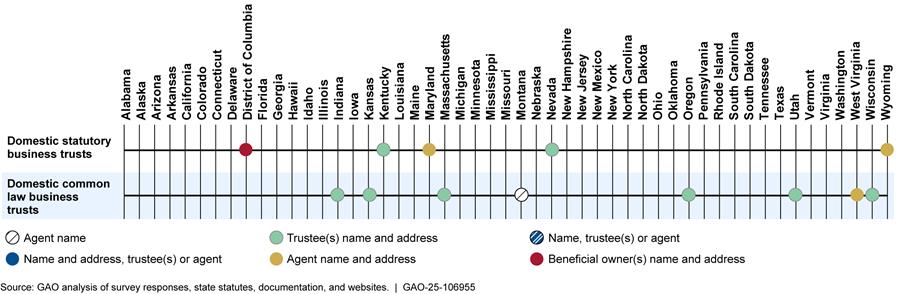

Our review of filing documentation indicates that some states collect the name and address of trustees of domestic business trusts in registration documents or periodic reports. Other states instead collect information on the agents, including registered agents that are authorized to accept service of process or other important legal and tax documents on behalf of a business (see fig. 7).[45] Depending on the level of ownership or control and whether the trust possesses ownership interests in a reporting company, parties associated with the trust may be considered beneficial owners.

Figure 7: Ownership and Other Information Required for Initial Filings by States That Register Domestic Business Trusts

Notes: Initial filings are documents required to register or form the trust in the state. Information is required only by the states that recognize domestic business trusts. Nine jurisdictions recognize domestic statutory business trusts. Nineteen jurisdictions recognize domestic common law business trusts. Florida, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina register domestic common law business trusts, but information on trustees, beneficial owners, or agents is not required at filing. North Carolina recognizes common law business trusts but does not require them to register.

A few states also require domestic business trusts to file periodic reports (see figure 8).

Figure 8: Ownership and Other Information Required for Periodic Filings by States That Register Domestic Business Trusts

Notes: Information is required only by the states that recognize domestic business trusts and require periodic filings. Nine jurisdictions recognize domestic statutory business trusts. Nineteen jurisdictions recognize domestic common law business trusts. Periodic filings are any documents (such as annual reports) and related fees that confirm the entity is still active, amend information related to the entity, or do both, and that must be regularly filed after the trust is created or registered with the state. Virginia requires business trusts to pay an annual registration fee to transact business in the state. This fee is paid online and does not require any ownership information to be reported.

With one exception, the jurisdictions we reviewed do not explicitly request information about a trust’s beneficial owner(s) in trust registration and formation documents.[46] That is, 50 jurisdictions do not include the terms “beneficial owner” or “beneficial ownership information” in their documents. The District of Columbia is the sole exception, explicitly requesting beneficial ownership information for domestic business trusts. As noted earlier, the District of Columbia’s definition of beneficial owner differs from FinCEN’s.[47]

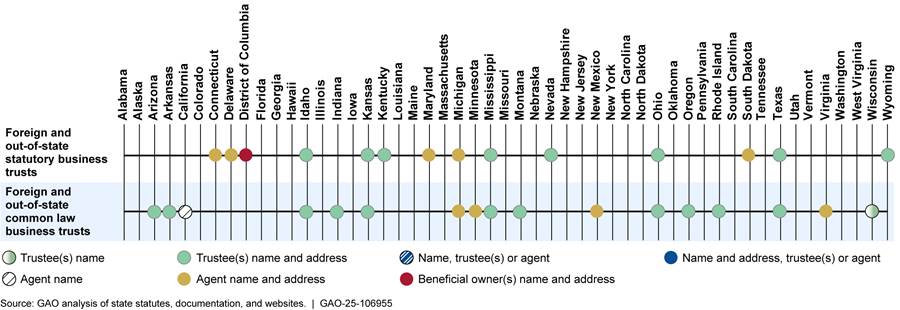

States Require Some Ownership Information for Foreign and Out-of-State Business Trusts

Our survey results and review of filing documents indicate that states generally require limited ownership information from foreign and out-of-state business trusts.

According to our review of initial filing documents and state statutes, 17 states require the name and address of a trustee(s) or an agent from foreign and out-of-state common law business trusts. Fourteen states require similar information from foreign and out-of-state statutory business trusts. The required information (such as trustee or agent name) may not correspond to beneficial owners as defined in the reporting rule. Only the District of Columbia requires the name and address of a beneficial owner. No jurisdiction requires any additional ownership information from other types of foreign and out-of-state trusts. See figure 9 for more information.

Figure 9: Information States Require from Foreign and Out-of-State Business Trusts for Initial Filings

Notes: Initial filings are documents required to register the foreign or out-of-state business trust in the state. Information is required only by the states that recognize such trusts and require them to register before conducting business in the state. Pennsylvania also registers foreign and out-of-state common law business trusts but information on trustees, beneficial owners, or agents is not required at filing. Foreign and out-of-state business trusts may be classified as statutory or common law based on the types of entities recognized in the state in which they want to do business. This classification may differ from how the entity is classified in the state in which it was formed. Colorado, Massachusetts, South Carolina, and Tennessee’s statutes do not address filing requirements for foreign and out-of-state business trusts; however, these states reported in their survey responses that they allow such trusts to register to conduct business in the state.

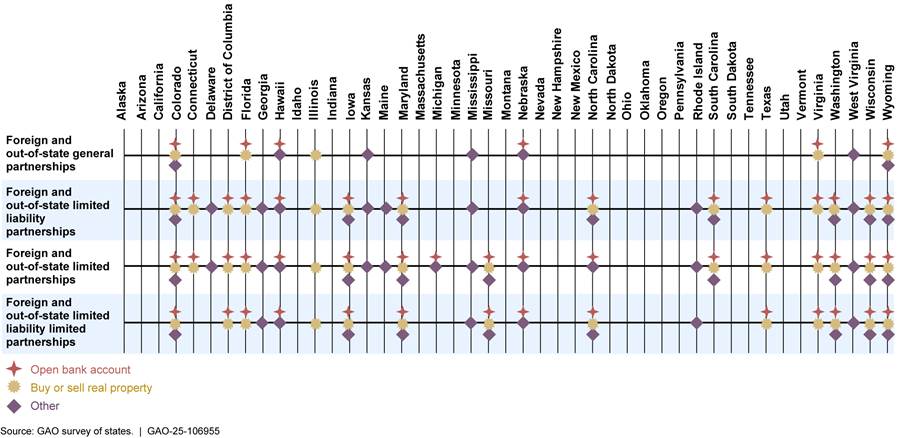

Ten of our 45 survey respondents reported that their states allow foreign and out-of-state business trusts to engage in certain financial activities (including opening bank accounts and purchasing and selling real property) without having to register because the states do not consider these activities conducting business.[48] See figure 10 for more information.

Figure 10: States in Which Unregistered Foreign and Out-of-State Business Trusts Can Engage in Certain Financial Activities

Notes: We conducted a survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia and received 45 responses. Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, and New York did not complete the survey. Such financial activities may include creating mortgages, collecting debt, enforcing debt collection, and engaging in interstate commerce.

Treatment of Domestic Business Trusts as Reporting Companies May Vary Depending on State Laws Governing Their Creation

Trusts established for business purposes may have different treatment under the beneficial ownership information reporting rule, depending upon the state laws governing their creation.

Statutory business trusts. In the nine states that provide a framework for statutory business trusts, a document—such as a certificate of trust—must be filed with the secretary of state to create the trust.[49] Therefore, these trusts would be considered reporting companies under the reporting rule.[50]

Common law business trusts. In contrast, common law business trusts may be required to register with the state and may need to file paperwork to conduct certain business activities. However, these trusts are formed by executing a valid trust instrument, similar to how a private individual would create a personal common law trust. Therefore, they may not be considered reporting companies for purposes of the reporting rule.

Law Enforcement Reports That Beneficial Ownership Information Aids Investigations, but Faces Challenges Obtaining It for Trusts

Law enforcement investigations are likely to benefit from the FinCEN beneficial ownership information registry, according to agency assessments, Congressional testimony, and federal law enforcement officials. The registry’s transparency and timely access it will provide to information will help address existing challenges in identifying beneficial owners, which have sometimes halted federal investigations, according to Treasury and law enforcement officials.[51]

The 2024 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment and law enforcement officials stated that access to the registry would improve agencies’ ability to investigate illicit finance by increasing corporate transparency and making it harder for criminals to conceal their activities behind layers of anonymous legal entities.[52] DOJ officials stated that beneficial ownership information also would aid efforts to fight transnational crime. For example, they said a registry will allow U.S. law enforcement officials to share beneficial ownership information with foreign law enforcement officials pursuing criminal cases involving U.S. entities.

The registry also is expected to provide timely access to such information, an advantage over existing methods. Law enforcement agencies employ a range of methods to gather information on beneficial ownership. These include summonses, subpoenas, search warrants, and interviews as well as banking records, state databases, and information from state authorities, according to law enforcement agencies. Although these methods seek to balance law enforcement needs with individual privacy rights, they can be time- and resource-intensive. Moreover, some methods, such as search warrants and wiretaps, require court involvement and authorization. In 2019 Congressional testimony, an FBI official cited several cases that were delayed or prolonged because of difficulties in obtaining beneficial ownership information on shell companies.[53] These cases involved sanctions evasion, foreign political corruption, human and drug trafficking, and fraud.

Treasury officials, including from IRS-CI, may access beneficial ownership information filed with IRS when pursuing tax crimes. Trusts and partnerships must designate a “responsible party,” which is similar to a beneficial owner, if they apply for an Employer Identification Number from IRS. However, according to IRS officials, releasing this information to other law enforcement agencies to pursue other crimes, such as money laundering, requires a court order.

DOJ officials told us they consider it less challenging to obtain beneficial ownership on partnerships, because partners are usually identified during formation. As discussed previously, states generally require the name and address of partners, who could be considered beneficial owners since they may have control over the partnership.

But in many cases, even after the beneficial ownership registry is operational, law enforcement agencies still will face barriers when obtaining beneficial ownership information for trusts, according to a Treasury assessment, our analysis of state requirements, and interviews with law enforcement agency officials and attorneys with expertise in trust law. For example:

· Because most types of trusts are not formed through state filings, they will not provide trust beneficial ownership information to FinCEN.

· Identifying the trustee can be difficult because most trusts are not registered.

· The trustee may be a trust company or an individual, but individual trustees are not subject to Bank Secrecy Act provisions and implementing regulations. These include requirements to conduct due diligence and file SARs on clients (who may be the trust’s beneficial owners) when they suspect illicit activity.[54] In some cases, law enforcement may have access to this information on trusts if the trustee is a trust company. Trust companies are generally subject to Bank Secrecy Act requirements.

· Trustees may be attorneys who are bound by attorney-client privilege. Even if they collect beneficial ownership information, this may limit their ability to share it with law enforcement, a challenge IRS-CI officials told us they frequently face.

Officials of DOJ, FinCEN, an organization representing trust and estate attorneys, and two banks we interviewed all agreed that reporting beneficial ownership information to FinCEN will require “piercing” a trust. This means that if a company that must report its beneficial owners is owned by a trust, the beneficial owners of the trust may have to be reported as the beneficial owners of the reporting company.[55] DOJ officials told us they believed this additional transparency will help in the investigation of cases of illicit finance involving trusts.

Use of Trusts and Partnerships for Illicit Finance Has Appeared to Be Low but May Pose Future Risks

Use of Trusts and Partnerships in Illicit Finance in United States Has Appeared to Be Lower Than for Corporations and LLCs

Trusts and partnerships represented a very small percentage of companies reported or investigated for suspected illicit financial activities, according to our review of Treasury risk assessments, SARs, federal law enforcement agency data (2019–2023), and international organizations.

Assessments of Risk

U.S. agencies differed somewhat in their views of the level of risk that partnerships and trusts posed for illicit finance. Treasury and DOJ officials told us they did not consider partnerships to pose a significant illicit finance risk. IRS-CI and DHS officials stated that partnerships remained a concern.[56] However, Treasury and the Financial Action Task Force reported that trusts presented some risks for illicit finance. In its 2024 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment, Treasury stated that trusts were vulnerable to misuse, primarily for tax evasion and for fraud.[57] A 2018 report by the Financial Action Task Force and the Egmont Group stated that trusts may pose a risk because they provide anonymity and allow criminals to conceal true ownership.[58]

In addition, Treasury assessed the risks of trusts as part of its 2024 National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing.[59] It found that because trusts are private agreements, very little is known about them, which itself is a potential vulnerability. For instance, there is no uniform collection of information on

· the total number of trusts formed in the United States,

· the identities of the parties to them,

· the sources of funds used to create them, or

· the value of assets held by them.

|

Cases of Illicit Finance Using Foreign Trusts · In 2020, the chairman and chief executive officer of a private equity company admitted to evading millions of dollars in taxes using a trust domiciled in Belize together with a shell company in Nevis. He used the trust to conceal his beneficial ownership of the company. · Financier Low Taek Jho, known as Jho Low, and his associates allegedly diverted $4.5 billion in assets from the Malaysian state development fund 1MDB. The U.S. Department of Justice alleged in 2016 that some of those assets, including a jet and a Beverly Hills hotel, were transferred to the custody of trusts in New Zealand. Source: GAO analysis of Department of Justice and government of New Zealand documents. | GAO‑25‑106955 |

According to Treasury, the Financial Action Task Force, and the Egmont Group, the risks associated with trusts are somewhat mitigated by the difficulty and cost of establishing a trust, in contrast to the relative ease of establishing a company. Representatives of an organization of trust and estate attorneys noted that forming a trust requires significant legal advice, and attorneys are bound by professional ethics to withdraw from an engagement if they know their clients are using funds for illicit purposes. According to a Treasury risk assessment, the need for criminals to find an attorney willing to violate the law and professional ethics serves as a barrier to using trusts for illicit activities. However, it is also possible for trustees to be co-conspirators in the illicit activity.

Trusts and similar arrangements created outside the United States currently pose greater risks than domestic ones.[60] According to DOJ officials, the Financial Action Task Force, Egmont Group, and Treasury’s National Money Laundering Risk Assessment, foreign trusts posed a higher risk than domestic trusts. This is partly because U.S. law enforcement officials cannot access beneficial ownership information of foreign trusts without the help of foreign governments, which requires considerable time and resources.

However, U.S.-based trusts have been implicated in illicit finance cases. The 2024 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment highlights two examples:

· A Russian oligarch allegedly used a Delaware trust to evade sanctions and invest in public and private U.S. companies.[61]

· A former president of Peru employed a U.S.-based trust to hide the ownership of assets purchased with the proceeds of corruption and bribery.[62]

A Treasury assessment also considered U.S.-domiciled trusts as higher risk if they received foreign funds transfers to purchase U.S. investments or real estate. Two state banking regulators and a U.S.-based trust company we interviewed told us that in recent years, they have observed an increase in trust accounts opened by foreign clients.

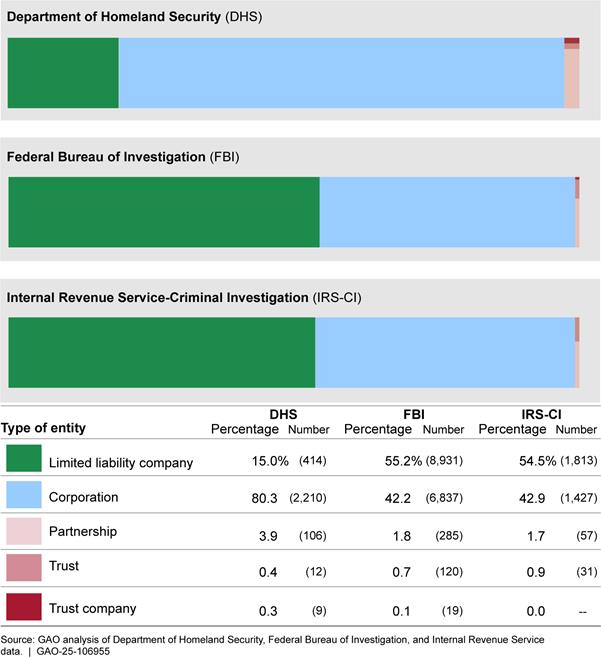

Share of SAR Reporting and Investigations by Company Type

During 2019–2023, trusts and partnerships were the subject of a relatively small percentage of SAR submissions to FinCEN and investigations by federal law enforcement entities (see figs. 11 and 12).[63] This analysis includes trust companies because they serve as professional trustees for trusts.[64] Less than 4 percent of corporate entities that were the subject of a SAR were trusts, trust companies, or partnerships.[65] However, DHS officials said that although few trusts or trust companies were named in a SAR or investigation, a single trust company could abuse any gaps in beneficial ownership reporting on behalf of its customers and launder significant assets.

Figure 11: Types of Entities Named in Suspicious Activity Reports Submitted to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, 2019–2023

Notes: One suspicious activity report can name multiple entities. Percentages do not sum to 100 due to rounding. A corporation is a legal entity that acts as a separate and distinct entity from its owners, directors, and officers and has legal rights. A limited liability company, like a corporation, offers its owners some protection from liability for the company’s debts. A partnership is an association of two or more individuals or entities who jointly own a business and agree to share in its profits and losses among the partners. Trusts are legal arrangements created when assets are placed under a trustee’s control for the benefit of one or more individuals or for a specified purpose. A trust company is a company that provides trustee services.

Similarly, few federal law enforcement investigations in that period involved trusts, trust companies, or partnerships (see fig. 12). From 2019 through 2023, less than 5 percent of entities investigated by FBI, IRS-CI, and DHS involved trusts or partnerships.

Notes: One investigation can involve multiple entities. Some percentages do not sum to 100 due to rounding. IRS does not report numbers below 10. A corporation is a legal entity that acts as a separate and distinct entity from its owners and has legal rights. A limited liability company, like a corporation, offers its owners some protection from liability for the company’s debts. A partnership is an association of two or more individuals who jointly own a business and agree to share in its profits and losses. Trusts are legal arrangements created when an individual places assets under a trustee’s control for the benefit of one or more individuals. A trust company is a company that provides trustee services.

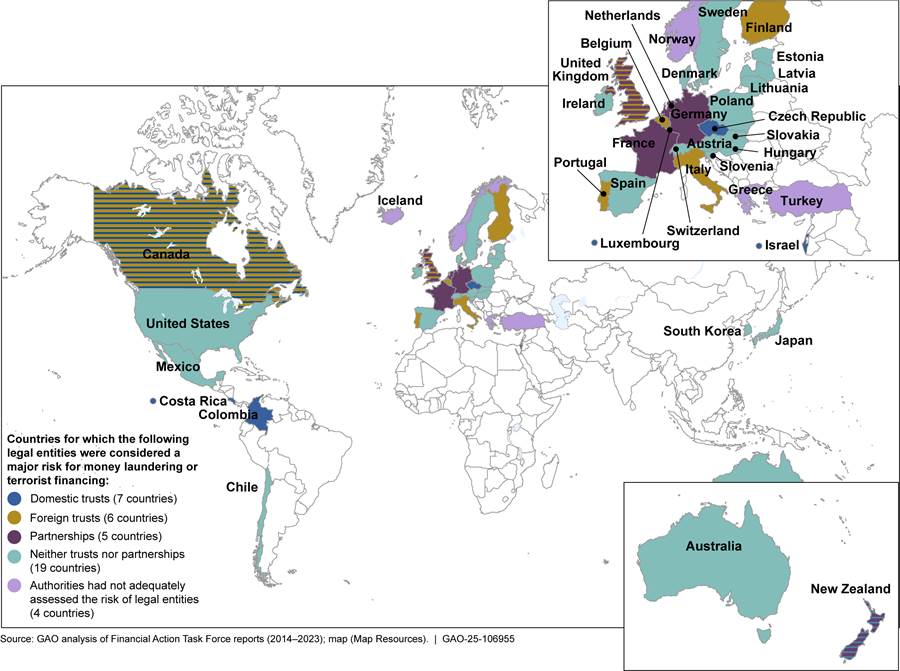

Trusts and Partnerships Generally Appeared to Pose a Greater Risk for Illicit Finance Abroad Than in the United States

Partnerships and trusts appeared to pose a greater risk for money laundering or terrorist financing in other countries than in the United States, according to our review of reports from international intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations.[66] Our analysis of Financial Action Task Force mutual evaluation reports from 2014 through 2023 showed that seven of 34 countries we reviewed considered domestic trusts (meaning trusts domiciled in their country) a major risk for money laundering or terrorist financing, and five considered partnerships a major risk (see fig. 13).[67] In six countries, foreign trusts were considered to pose a major risk. In contrast, in the United States, none of these entities were identified in the Task Force’s mutual evaluation reports as a major risk for money laundering or terrorist financing.

Figure 13: Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Posed by Trusts and Partnerships in Selected Countries

Note: Trusts, as used here, include legal arrangements such as the French fiducie that are similar to trusts. We analyzed information from the 38 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development because most have advanced economies similar to the United States. Four of the countries had not assessed the risk of trusts or partnerships.

Other quantitative reviews by intergovernmental organizations also show that trusts account for a small percentage of entities used in illicit finance globally, with partnerships being used even less frequently.

· A 2018 study by the Financial Action Task Force and the Egmont Group analyzed 106 large money laundering cases and found that at least one trust or similar legal arrangement was used in about 25 percent of them.[68] The study found that partnerships were involved in only a “very small number” of cases.

· A 2011 World Bank review of 150 grand corruption investigations found that 43 of the 817 entities identified (about 5 percent) were trusts, and nine (about 1 percent) were partnerships.[69] The study found that the United States, the Bahamas, Cayman Islands, and Jersey were principal domiciles for the trusts whose domiciles the study was able to identify.

However, a 2022 Transparency International UK report suggested that limited liability partnerships in the United Kingdom may have been used as conduits for illicit finance, perhaps because they do not require any natural persons to be partners.[70] As previously discussed, according to the Uniform Limited Partnership Act (2013), a general partner may be a natural person (an individual) or a nonnatural person (for instance, a company).

The creation of beneficial ownership information registries may introduce new or additional risks. Treasury, law enforcement agencies, and nongovernmental anticorruption organizations warn that criminals could exploit registry gaps in coverage by using trusts or partnerships that are not required to report beneficial ownership information to a registry. However, a Treasury assessment states that because trusts are rarely used in commercial transactions, the risk of criminal activity shifting to trusts may be limited.

|

Scottish Limited Partnerships and Irish Limited Partnerships Scottish limited partnerships and Irish limited partnerships were created by the United Kingdom’s Partnership Act of 1890 and Limited Partnerships Act of 1907. Both entities provide limited liability, meaning that the liability of most partners generally is limited to the amount of the partner’s contribution to the firm. Scottish limited partnerships have a legal existence distinct from their partners, but Irish limited partnerships do not. After Ireland became an independent country in 1922, Irish limited partnerships were no longer subject to UK law. Source: GAO analysis of United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland documents. | GAO-25-106955 |

The United Kingdom’s beneficial ownership information registry, implemented in 2016, may have caused some criminals to use entity types not included in the registry (see sidebar). According to a report by the nongovernmental anticorruption organization Transparency International UK and the investigative collective Bellingcat, the number of Scottish limited partnerships (initially not included in the registry) rose significantly after other companies in the UK were required to have at least one natural person as a director.[71] However, after Scottish limited partnerships were required to report to the registry in 2017, their numbers fell.[72] Meanwhile, the number of Irish limited partnerships, which are not subject to the law, rose significantly beginning in 2015.

Treasury Could Enhance Its Monitoring of Illicit Activities Involving Trusts and Partnerships

Treasury does not yet have a plan to periodically analyze SAR data for trends of increased illicit activity among trusts and partnerships. As discussed earlier, the proportions of trusts and partnerships identified in SARs and investigation data were relatively low in recent years. However, federal agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and our analysis of ownership reporting requirements at the federal and state levels have highlighted risks relating to the ability of illicit actors to use trusts and other entities to hide ownership information, and the potential for such risks to change over time in response to new reporting requirements.

A Treasury risk assessment has identified the lack of information about trusts in the United States to be a vulnerability, and stakeholders have expressed concerns that criminals may use trusts and partnerships to exploit regulatory gaps. The wide variety of trusts and partnerships creates challenges, because they do not all fall neatly into the FinCEN definition of “reporting company.” Some types of partnerships and trusts may not be considered reporting companies that are required to provide beneficial ownership information under the reporting rule because of the variation in state laws. Treasury officials told us that they recognized this complexity and are uncertain how it will affect beneficial ownership reporting when the requirement goes into effect.

Treasury has taken some actions to proactively address these risks. According to the 2024 National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing, Treasury conducted a baseline risk assessment on trusts using qualitative data, such as law enforcement interviews and case reviews. In addition, FinCEN issued a report in December 2022 and Treasury participated in issuing a 2023 advisory to financial institutions based on Bank Secrecy Act data. FinCEN’s 2022 report highlighted risks associated with certain trusts tied to Russian oligarchs, high-ranking officials, and sanctioned individuals.[73]

Treasury also analyzed foreign addresses commonly found in SARs and shared the results with law enforcement. This analysis may provide insight into the use of foreign trust and company service providers that may shield the identities of individuals engaged in illicit activity, according to Treasury officials.[74] In addition, Treasury used information from strategic analysis on SARs to inform its 2024 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment. For example, the 2024 assessment reported that the number of SARs related to check fraud increased by 23 percent from 2020 to 2021 and 94 percent from 2021 to 2022.

However, Treasury does not periodically analyze data, targeted specifically by entity type, such as the number of trusts and partnerships named in SARs, that could help monitor the identified risks. Treasury officials told us that the lack of data on the total number of these entities in the U.S. would be an analytical challenge and that there are limitations in easily identifying subject partnerships and trusts to facilitate this type of trend analysis. Notwithstanding this, Treasury officials told us such limitations would not prevent them from conducting analysis of the use of trusts and partnerships and that information from the new beneficial ownership database may also be useful when available.[75] Such information would allow Treasury to identify any changing patterns of criminal activity at an earlier stage and provide useful information for Congress that may inform public policy in a timely manner.

The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 states that the Director of FinCEN shall “determine emerging trends and methods in money laundering and other financial crimes.”[76] Congress reiterated the importance of this information in the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020, requiring FinCEN to periodically publish analytical information, based on SARs and other types of Bank Secrecy Act reports, on threat patterns, trends, and typologies for laundering money and financing terrorism.[77] FinCEN’s December 2022 report on trusts tied to Russian oligarchs is an example of reporting under this section.

By periodically analyzing SAR data for the risk of illicit activity related to trusts and partnerships, Treasury would better equip itself and other law enforcement agencies to promptly identify changes in the use of trusts and partnerships and target its efforts to combat illicit finance relating to these types of entities.

Conclusions

The lack of transparency in beneficial ownership of corporate structures has enabled illicit actors to launder money with anonymity. The Corporate Transparency Act aims to combat this by requiring certain entities to submit beneficial ownership information to a FinCEN registry. But gaps in this regime exist, as certain partnerships and trusts are not subject to reporting requirements or may not be fully covered by them. Moreover, international research suggests that a beneficial ownership registry can introduce new risks, such as criminals exploiting regulatory gaps by using entity types not subject to the registry. This underscores the importance of FinCEN’s monitoring and analysis of the potentially illicit use of trusts and partnerships. Analysis related to trusts and partnerships using data from SARs could help determine the extent to which criminals may exploit gaps in reporting requirements and the beneficial ownership registry. These analyses could inform future assessments of money laundering and terrorist financing risks, strengthening the fight against illicit finance.

Recommendation for Executive Action

We are making the following recommendation to the Treasury:

The Secretary of the Treasury should ensure that the Director of FinCEN periodically analyzes SAR data for the risk of illicit activity related to trusts and partnerships and incorporates this analysis in future money laundering and terrorist financing risk assessments. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DHS, DOJ, IRS, and Treasury for review and comment. Treasury, DOJ, and DHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. IRS did not have any comments on the report. Treasury provided written comments that are reprinted in appendix II. In its written comments, which are summarized below, Treasury agreed with our recommendation and noted that the new beneficial ownership database may also provide insights on the risk of illicit activity related to partnerships and trusts. Treasury also provided examples of how it has taken some steps to combat illicit finance risks posed by partnerships and trusts, many of which we had already included in the draft report.

Treasury disagreed with two aspects of our findings. First, Treasury disagreed with our statement that FinCEN does not plan to monitor SAR data for potential signs of increased illicit activity among trusts and partnerships. Treasury stated, for example, that FinCEN regularly reviews SARs on case-specific matters for stakeholders that may involve trusts and partnerships and provided analytical support for development of a risk assessment on trusts. We recognize the efforts that FinCEN has taken to support law enforcement agencies and other officials in identifying illicit finance risks, as noted in our report. However, we emphasize that Treasury does not yet analyze data specific to trusts and partnerships in SARs on a periodic basis to monitor for trends and clarified this in the report.

Treasury also disagreed with our characterization of the reason that the agency does not have a plan to track trusts and partnerships. Specifically, Treasury disagreed that it does not plan to do so because the total number of trusts and partnerships was not known. Treasury also stated that its ongoing efforts have included a new regulation that will require real estate professionals to report, to FinCEN, beneficial ownership information on trusts used in certain residential real estate transactions beginning December 1, 2025. In response to these comments, we adjusted our report language to acknowledge Treasury’s current analytical limitations and the new reporting rule related to certain real estate transactions. In its written comments, Treasury stated that it agrees with the potential benefits and that it plans to consider trend analysis of partnerships and trusts in its ongoing work.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Attorney General, Secretary of Homeland Security, and Secretary of the Treasury. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at 202-512-8678, ClementsM@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Michael E. Clements, Director

Financial Markets and Community Investment

List of Committees

The Honorable Sherrod Brown

Chairman

The Honorable Tim Scott

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Richard J. Durbin

Chair

The Honorable Lindsay Graham

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Chairman

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Patrick McHenry

Chairman

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jim Jordan

Chairman

The Honorable Jerrold Nadler

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

House of Representatives

The Honorable Mark E. Green, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The objectives of this report were to examine (1) state requirements for forming and registering partnerships, and the beneficial ownership information on partnerships that states collect; (2) state requirements for forming and registering trusts, and the beneficial ownership information on trusts that states collect; (3) views of federal law enforcement officials on how beneficial ownership information for trusts and partnerships may affect law enforcement investigations of illicit finance; and (4) views and available data on the current and future use of trusts and partnerships for illicit finance in the United States and other industrialized countries, including potential future risks.

State Requirements for Forming and Registering Partnerships and Trusts

For the first and second objectives, we reviewed documentation about registration requirements and collection of beneficial ownership information for partnerships and trusts from the websites of secretaries of state (or similar offices) for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. We also reviewed these jurisdictions’ laws related to creation and registration requirements for partnerships and trusts and reviewed relevant Uniform Acts.[78] We reviewed the final beneficial ownership information reporting rule, as well as comment letters that organizations, members of Congress, states and Tribes submitted in response to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s (FinCEN) Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.[79]

In addition, we sent a web-based survey to the secretaries of state (or similar offices) in all 50 states and the District of Columbia to gather information on their requirements for forming and registering partnerships and trusts. We conducted five pretests of our draft questionnaire with officials at seven secretary of state offices. We selected those states for diversity in number of registered business trusts and partnerships and because they had submitted comment letters in response to FinCEN’s proposed rule. We used these pretests to help clarify and refine our questions, develop new questions, and identify any potentially biased questions, and we made revisions as needed.

We conducted the survey from April 1, 2024, through June 10, 2024. We followed up with nonrespondents via telephone and email. We received responses from 44 states and the District of Columbia. We used the survey responses to supplement our analysis of registration documents and state laws, as appropriate.

We also interviewed officials from the Department of the Treasury, including FinCEN. In addition, we interviewed representatives of associations for secretaries of state and two groups of attorneys with expertise in trust and estates law and business law, who were referred to us by the American College of Trust and Estate Counsel and the American Bar Association, respectively, to discuss entity formation and registration.

Views on Beneficial Ownership Information

For the third and fourth objectives, we reviewed Treasury risk assessments and strategies related to money laundering and terrorist financing. We also reviewed congressional testimony on the use of shell companies in illicit finance.

We conducted a literature search of peer-reviewed journals and reports by nongovernmental organizations published from 2013 through 2023. To identify an initial list, we worked with a research librarian to conduct keyword searches of databases such as Westlaw, ABI/Inform, and Scopus, using terms related to beneficial ownership in conjunction with terms related to trusts and partnerships. We then examined summary-level information about each publication and selected 61 articles that were germane to our study, which we reviewed.

We identified additional literature by searching for reports related to the use of trusts and partnerships in illicit finance published by relevant nongovernmental organizations. These organizations included those that submitted comments on FinCEN’s Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for the beneficial ownership information reporting rule, as well as others identified by GAO research or recommended by two nongovernmental organizations we interviewed. In addition, we interviewed representatives of three state financial regulatory agencies, selected because these three states have trust industries that have been implicated in illicit finance. Furthermore, we interviewed representatives of five financial institutions within the three selected states above, because they provide trustee services.

Data on Use of Trusts and Partnerships

For the fourth objective, we examined Treasury’s approach to assessing the risks of partnerships and trusts against requirements in the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 and Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 for determining trends in money laundering and other financial crimes. We reviewed FinCEN data from 2019–2023 on the number of suspicious activity reports (SAR) that involved subject entities of five types: corporations, limited liability companies, partnerships, trusts, and trust companies. We reviewed similar data on the number of investigations that involved a subject entity of these same five types from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), and Internal Revenue Service-Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI).[80] To obtain these data, we asked these agencies to conduct keyword searches on the subject entity field of relevant databases. We categorized entities as corporations, limited liability companies, trusts, partnerships, or trust companies based on keyword matches.

To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed agency documentation of these systems, interviewed agency officials responsible for the data, and compared results across agencies. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for illustrating the number of entities named in SAR submissions and investigations by law enforcement that were trusts and partnerships compared with other entity types.

We also analyzed the Financial Action Task Force’s most recent Mutual Evaluation Report, and any follow-up reports, for each of the 38 member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. From the reports, we determined which countries had (1) implemented a beneficial ownership registry for legal persons or legal arrangements, and (2) identified partnerships or trusts as being a major risk for money laundering or terrorist financing.

In addition to the interviews described above, we interviewed officials from (1) components within the Department of Justice, including FBI and the Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys; (2) the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement and HSI; and (3) IRS-CI. We discussed their perspectives on the usefulness of beneficial ownership information in law enforcement investigations and on the use of trusts and partnerships in illicit finance.[81] We also interviewed representatives of Transparency International and the Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency Coalition, two organizations with expertise in illicit finance.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Michael E. Clements, (202) 512-8678 or ClementsM@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contacts named above, Kay Kuhlman (Assistant Director), Meredith Graves (Analyst in Charge), Evelyn Calderon, Mariana Calderon, Caroline Christopher, Kristina Hammon, Daniel Horowitz, Jill Lacey, Matthew Levie, Alberto Lopez, Barbara Roesmann, and Jena Sinkfield made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.