FOREIGN SERVICE PROMOTIONS

State Should Improve Documentation and Consider Expanding Demographic Representation on Selection Boards

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-106956

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106956. For more information, contact Nagla'a El-Hodiri at (202) 512-7279 or elhodirin@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106956, a report to congressional committees

November 2024

Foreign Service Promotions

State Should Improve Documentation and Consider Expanding Demographic Representation on Selection Boards

Why GAO Did This Study

The Foreign Service promotion process shapes the face of U.S. diplomacy. State’s overarching goal is to make the promotion process fair, inclusive, and effective. However, a 2022 State survey found employees perceived a lack of fairness and objectivity in the promotion process.

The fiscal year 2023 National Defense Authorization Act includes a provision for GAO to conduct a comprehensive review of State’s promotion process. This report examines the extent to which State has (1) made changes to its promotion process since 2020 and documented its assessment of the usefulness of relevant leading practices and (2) followed its requirements for the composition of selection boards and ensured demographic diversity on these boards. GAO analyzed State data on the composition of employees from 2019 through 2023, reviewed State documents and a State-commissioned benchmark study on leading practices, and interviewed State officials. GAO also reviewed its nine leading practices on DEIA to identify the one that was relevant to State’s promotion process.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to State, including that it document the usefulness of the leading practices mentioned in the benchmark study for its reform initiative and consider how best to ensure that selection board member composition reflects the composition of the Foreign Service, including ethnicity and disability status. State agreed with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

In 2020, the Department of State launched an initiative to transform the Foreign Service promotion process to be more fair, inclusive, and effective. State commissioned a 2021 benchmark study that identified four leading practices to help guide its reform but did not document its assessment of their usefulness. State made changes such as introducing a scoring rubric for promotion panels (known as selection boards) to rate and provide feedback to candidates. GAO found that this change and one other reflected three of the four leading practices identified in the study. State’s written assessment of the usefulness of the leading practices, as described in federal internal control standards, could increase employee confidence in the promotion process and provide transparency on the rationale for changes made.

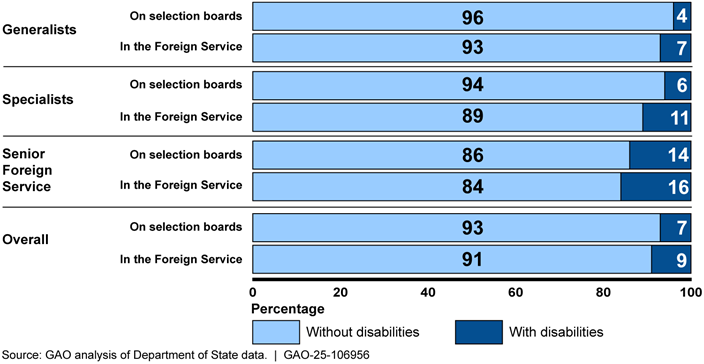

State has generally followed but not fully documented its seven broad requirements for the composition of selection boards. For example, State officials told GAO they have met the requirement to “include a substantial number of women” by assigning at least one woman to each selection board. However, they have not documented this definition of the requirement because they said they need flexibility. In addition, State has not expanded the demographic criteria for selection boards to ensure they reflect the composition of the Foreign Service, including ethnicity and disability status, as suggested by a GAO leading practice on diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA). From 2019 through 2023, selection boards generally included higher representation of women and historically disadvantaged racial groups, but lower representation of historically disadvantaged ethnic groups and people with disabilities, in comparison with the Foreign Service. By considering demographic representation across all selection boards, specifically for ethnicity and disability status, State would better position itself to include varied perspectives in assessing employees for promotion.

Note: Generalists implement U.S. foreign policy. Specialists support and maintain the functioning of overseas posts. Senior Foreign Service is the highest level of the Foreign Service.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

DEIA |

Diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility |

|

GTM |

Office of Performance Evaluation, Bureau of Global Talent Management |

|

GEMS |

Global Employment Management System |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 18, 2024

Congressional Committees

The Department of State’s Foreign Service promotion process shapes the face of U.S. diplomacy. State’s process follows an up-or-out principle, under which failure to gain promotion to a higher rank within a specified period leads to mandatory retirement for certain employees. The way State designs and implements this process affects all Foreign Service employees. State established an overarching goal to make the promotion process fair, inclusive, and effective. However, State’s 2022 Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility (DEIA) Climate Survey found employees perceived a lack of fairness and objectivity in the Foreign Service promotion process.

State has expressed a commitment to maintaining a workforce that reflects the diverse composition of the United States and has undertaken efforts to increase representation of diverse groups in the Foreign Service. Nonetheless, we reported in January 2020 that State’s Foreign Service promotion outcomes were generally lower for historically disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups than for non-Hispanic Whites.[1] In 2020, State launched a reform initiative to transform its current process into one that aims to be more data-driven, collaborative, and worthy of the Foreign Service’s confidence. To help guide this reform initiative, State commissioned a third party to conduct a benchmarking study that identified leading practices of comparable performance management and evaluation systems used by similar organizations.[2]

The fiscal year 2023 National Defense Authorization Act includes a provision for us to conduct a comprehensive review of the policies, personnel, organization, and processes related to promotions within State.[3] This report examines the extent to which State has (1) made changes to its Foreign Service promotion process since 2020 and documented its assessment of the usefulness of relevant leading practices and (2) followed its requirements for the composition of selection boards, which evaluate candidates for promotion, and ensured demographic diversity on these boards.

To examine the extent to which State has made changes to its Foreign Service promotion process since 2020 and documented its assessment of relevant leading practices, we reviewed State documents and interviewed State officials. We compared changes State made to its promotion process with the key considerations of the four leading practices in the benchmarking study. We also compared the extent to which State has documented its assessment of the usefulness of the four leading practices identified in this study with its proposed reform goals and federal internal control standards for developing and maintaining documentation to retain organizational knowledge and mitigate the risk of having that knowledge limited to a few personnel.[4]

To examine the extent to which State has followed its requirements for the composition of selection boards, we examined whether the boards’ composition followed State’s requirements as outlined in the Foreign Affairs Manual. We reviewed State documents and interviewed State officials to determine how State’s Bureau of Global Talent Management, which is responsible for administering the Foreign Service promotion process, defines these requirements for selection boards.[5] We compared State’s efforts to document its definitions with federal internal control standards for developing and maintaining documentation to retain organizational knowledge.[6] We analyzed State workforce data to compare the composition of selection boards with State requirements as defined by the bureau responsible for promotions.

We also reviewed our nine leading practices on DEIA to identify the one that was relevant to the promotion process and compared it with State’s requirements and the demographics of the Foreign Service.[7] We determined State’s workforce composition data to be sufficiently reliable for presenting summary statistics on the demographics of the Foreign Service and for summarizing the composition of selection boards. See appendix I for more information about our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of Foreign Service Promotions

The Foreign Service Act of 1980, the Foreign Affairs Manual, and guidelines known as procedural precepts govern State’s Foreign Service promotion process.[8] The Act outlines requirements for the Foreign Service, including for its promotion process. The manual establishes broad policies for promotions based on the Act. State annually prepares the procedural precepts, which establish the scope, organization, and responsibilities of the selection boards that evaluate candidates for promotion. Within State’s Bureau of Global Talent Management, the Office of Performance Evaluation (GTM) administers the Foreign Service performance management and promotion process.[9]

The Foreign Service Act requires, among other things, that selection boards rank employees of the Foreign Service on the basis of relative performance and allows the selection boards to make recommendations for promotion. Each selection board generally includes three to five Foreign Service employees and must include one member from the public. According to State officials, public members’ perspectives are different from those of Foreign Service members and serve as an additional safeguard over the integrity of the process. However, a 2022 report from State’s Office of Inspector General found that GTM did not demonstrate that it considered all Foreign Affairs Manual criteria when recruiting and selecting public members.[10] In response, GTM worked with a third-party contractor to select public members for the boards starting in 2023.

Selection boards automatically consider all Foreign Service employees for promotion between 1 and 4 years after their last promotion, depending on their level, until they seek a promotion into the highest level of the Foreign Service. Those employees who wish to be considered for promotion into the highest level, known as the Senior Foreign Service, must elect to be considered by the selection boards.

GTM convenes about 20 selection boards per year to evaluate the performance of over 10,000 generalists, specialists, and Senior Foreign Service employees, according to State data. Selection boards make recommendations for promotion. They can also make recommendations to the Performance Standards Boards for possible mandatory retirement from the Foreign Service because of poor performance.[11] This evaluation process, which we refer to as the Foreign Service promotion process, results in about 1,400 promotions per year, according to State data. The number of candidate performance files each board reviewed has varied by board and year. For example, in 2023 each board reviewed between 150 and 583 files, according to GTM officials. Collectively, GTM convened 101 selection boards that assessed over 51,000 candidates for promotion between 2019 and 2023.

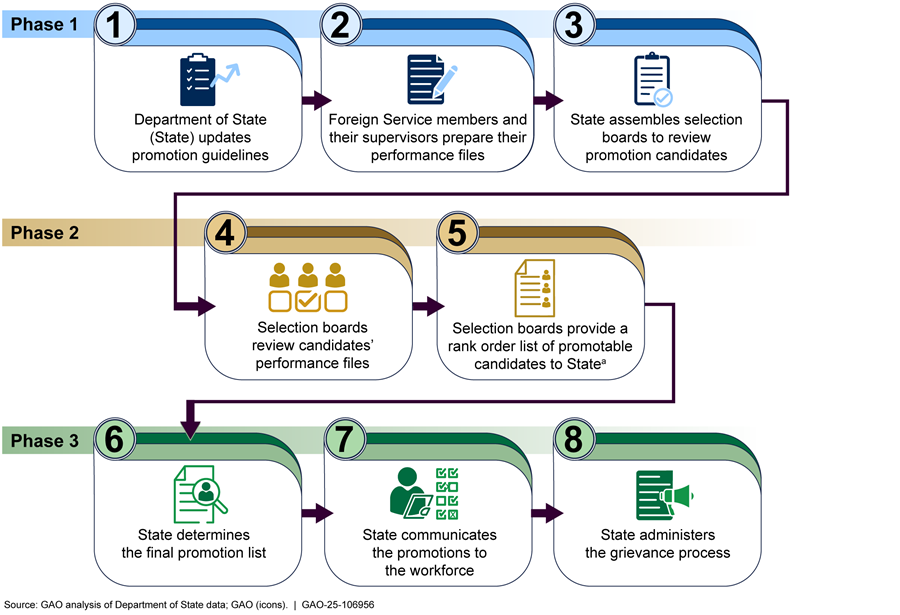

Promotion Process

As shown in figure 1, the process has three key phases. In phase one, GTM updates its promotion guidelines, Foreign Service employees prepare their performance files, and GTM assembles selection boards. In phase two, selection boards review candidates for promotion. In phase three, State determines the final promotion list, communicates the results to the workforce, and administers the grievance process.[12]

Figure 1: Foreign Service Promotion Process

Note: The Office of Performance Evaluation in State’s Bureau of Global Talent Management administers the Foreign Service performance management and promotion process.

aIn phase 2, selection boards also provide State an alphabetical list of mid-ranked candidates and an alphabetical list of low-ranked candidates.

Phase 1. Before the selection boards convene, State takes the following steps.

State, in negotiation with the American Foreign Service Association, periodically updates its promotion guidelines.[13] State updates the procedural precepts each year and the core precepts about every 3 years. The procedural precepts cover areas such as the conditions for eligibility for promotion, guidance for boards on evaluating candidates, and information that boards are required to submit following their decisions. The core precepts define specific skills and accomplishments expected at different levels and for various specialties within the Foreign Service. These precepts are the decision criteria for promotion, providing the guidelines by which selection boards evaluate candidates for promotion.

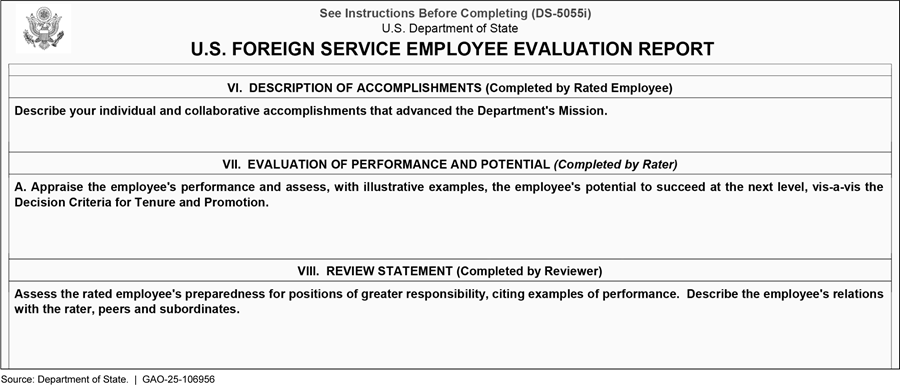

Foreign Service employees and their supervisors draft employee evaluation reports, including narratives. In the narratives, supervisors appraise employees’ potential to perform successfully at the next higher level on the basis of their observations over the rating period and cite specific examples of the employees’ work in support of their appraisals. Figure 2 shows the sections of the template that are relevant to promotion. Procedural precepts direct selection boards to base their promotion decisions on the reports and other evaluation materials, such as awards and disciplinary letters.

Figure 2: Template for the Employee Evaluation Report Used by Selection Boards in Making Foreign Service Promotion Decisions

GTM solicits volunteers from the Foreign Service to serve on selection boards. It applies the requirements from the Foreign Affairs Manual in assigning employees to selection boards. It also assigns members of the public with related experience or interest to each selection board. State announces the finalized board members in a department-wide cable.

The Director General of the Foreign Service and the Director of Global Talent (Director General) determines the number of promotion opportunities that will be available for each career track and level in the current year. GTM sends these numbers to the American Foreign Service Association. GTM holds the number of opportunities in confidence so that they do not affect the deliberations of the boards in the following phase.

Phase 2. Selection boards take the following actions during their deliberations.

Selection board members individually review each candidate’s folder with instructions to place the greatest emphasis on the (1) 5 most recent years of evaluative material or (2) evaluative material since the candidate’s most recent promotion (if the candidate has less than 5 years of such material because of a recent promotion). Selection boards deliberate and sort candidates into three categories—promotable, mid-rank, and low-rank. After deliberation, the selection boards provide GTM (1) a rank order list of candidates recommended for promotion, (2) an alphabetical list of mid-ranked candidates (who are generally not reviewed again for promotion by that board), and (3) an alphabetical list of low-ranked candidates. Selection boards can refer low-ranked employees directly to the Performance Standards Boards.[14]

Phase 3. Using the results from the selection boards, State takes the following steps.

After receiving the selection boards’ official reports, GTM applies the “cutoff” line on selection boards’ rank order list of employees recommended for promotion on the basis of the previously calculated and approved number of promotion opportunities. GTM then vets each candidate above the “cutoff” line with other State offices and determines which candidates, if any, should be temporarily removed from the list on the basis of misconduct charges in their files or ongoing investigations.[15] The Under Secretary for Management approves the promotions of candidates in the Foreign Service. The Under Secretary transmits the list of members recommended for promotion into and within the Senior Foreign Service to the Secretary of State for recommendation to the President. These promotions require the confirmation of the Senate and appointment by the President. State communicates the promotion decisions to the workforce through cables.

Foreign Service employees can grieve procedural violations, prohibited personnel practices, and inaccurate evaluative materials in the promotion process to GTM’s Grievance Staff, according to GTM officials. However, employees cannot grieve the outcome of the promotion process.[16] Foreign Service personnel are encouraged to first attempt to resolve concerns about their employee evaluation reports with their supervisor at the post or bureau level.

Reform Initiative

In 2020, GTM launched its Foreign Service Performance Management Reform Initiative.[17] This reform initiative seeks to

· ensure the department develops, evaluates, and promotes employees in a fair, inclusive, and effective manner; and

· have a data-driven, collaborative, and sustained effort that assesses the strengths and shortcomings of the performance management and promotion process to transform it into one more worthy of the Foreign Service’s confidence.

State Made Changes to Its Promotion Process but Did Not Document Its Assessment of the Usefulness of Its Commissioned Study of Leading Practices

State Has Made Several Changes to Improve Its Promotion Process since 2020

As part of its updates to the performance management and promotion process, GTM made changes that generally aligned with its 2020 Performance Management Reform Initiative goal to promote employees in a fair, inclusive, and effective manner. These included the following changes to the employee evaluation report, core precepts, and procedural precepts that govern the selection boards.

Employee evaluation report: In 2022, GTM prohibited raters and reviewers from making any statements recommending or advising against the promotion of a particular employee in an evaluation report. Prior to the change, raters could recommend candidates for immediate promotion and without providing concrete examples of candidates’ ability to perform at the next level. Instead, GTM now directs raters and reviewers to clearly illustrate the extent to which the rated employee has demonstrated the potential to perform successfully at the next level. According to the Director General, though this change represents a significant cultural shift, it is intended to reduce disagreement among employees, raters, and reviewers regarding recommendation statements.

Core precepts: In 2022, GTM announced five new Foreign Service core precepts that integrate elements of earlier core precepts, reflect the competencies determined to be the most critical, and include competencies in which potential to be promoted must be demonstrated. The precepts took effect for the 2022–2023 promotion cycle, replacing the previous ones. The new core precepts integrate some of the elements of the earlier core precepts. (See table 1.) GTM, in collaboration with the American Foreign Service Association, reviews the core precepts every 3 years. According to GTM, the new precepts are more concise, easier to use, and more reflective of the skills necessary to confront the challenges of the 21st century. As part of the reform effort, GTM added a new core precept on DEIA. The new DEIA precept addresses how employees demonstrate inclusivity and respect in relations with colleagues and others. The DEIA precept combines elements from the previous core precepts on interpersonal skills, leadership, communication, and management, according to officials. To better facilitate selection board reviews, employees are encouraged to write directly to each of the individual core precepts in their evaluation report narratives.[18]

Table 1: Comparison of Core Precepts State Used to Evaluate Foreign Service Employees’ Performance, 2018–2021 versus 2022–2025 Rating Cycles

|

2018–2021 |

2022–2025 |

||

|

Core precepts |

Definition |

Core precepts |

Definition |

|

Communication and foreign language skills |

Effectively communicates orally and in writing, actively listens, engages in public outreach, and builds foreign language skills. |

Communication |

Effectively writes, speaks, and negotiates. Instills trust, includes differing viewpoints, and communicates respectfully. |

|

Interpersonal skills |

Maintains professional standards, effectively negotiates, and displays perceptiveness and adaptability in the workplace. |

Diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility |

Demonstrates inclusivity and respect in relations with colleagues. |

|

Leadership skills |

Develops innovative and technical solutions, effectively makes decisions, and fosters teamwork. Open to differing views, contributes to community and public service, and upholds institutional values. |

Leadership |

Advances innovative ideas and solutions. Fosters an organizational culture of strategic risk taking that furthers department objectives. Manages conflict constructively. Exhibits professionalism, respect, and fairness to others. |

|

Managerial skills |

Effectively manages operations and resources. Improves performance and promotes professional development. Achieves customer service goals. Safeguards people, information, and resources. Supports equal employment opportunities. Uses crisis management skills. |

Management |

Effectively manages operations and achieves customer service goals. Develops and shares best practices to eliminate redundancies. Safeguards people, information, and resources. |

|

Substantive knowledge |

Understands how job relates to organizational goals and U.S. policy objectives and understands interagency cooperation. Develops technical skills, knowledge of foreign cultures and deepens professional expertise. |

Substantive and technical expertis

|

Develops technical skills, maintains foreign language skills, and deepens professional expertise to achieve mission and department goal. Bases decisions on data-driven analysis, uses trainings to develop skills. |

|

Intellectual skills |

Gathers and analyze key information, uses critical thinking skills, engages in professional development, and uses trainings to improve leadership and management. |

||

Source: GAO analysis of Department of State documents. | GAO‑25‑106956

Procedural precepts: In 2023, GTM also made changes to the selection boards’ procedural precepts as part of its annual updates to the promotion process. First, State issued new guidance that removed instructions for boards to consider assignment patterns, such as long-term training or detail assignments outside of a candidate’s direct responsibilities, when assessing an employee’s promotability. GTM officials said that prior to this change, selection boards tended to make promotion decisions on the basis of assignment patterns, including whether employees served at hardship posts where conditions differ substantially from those in the United States.[19] According to the new guidance and officials, boards should now weigh the impact of employees’ work and their ability to serve at the next level in accordance with the core precepts, regardless of the conditions of prior posts. GTM officials explained that serving at a hardship post, by itself, may not demonstrate that an employee’s work was impactful; thus, it is no longer the basis of promotion decisions.

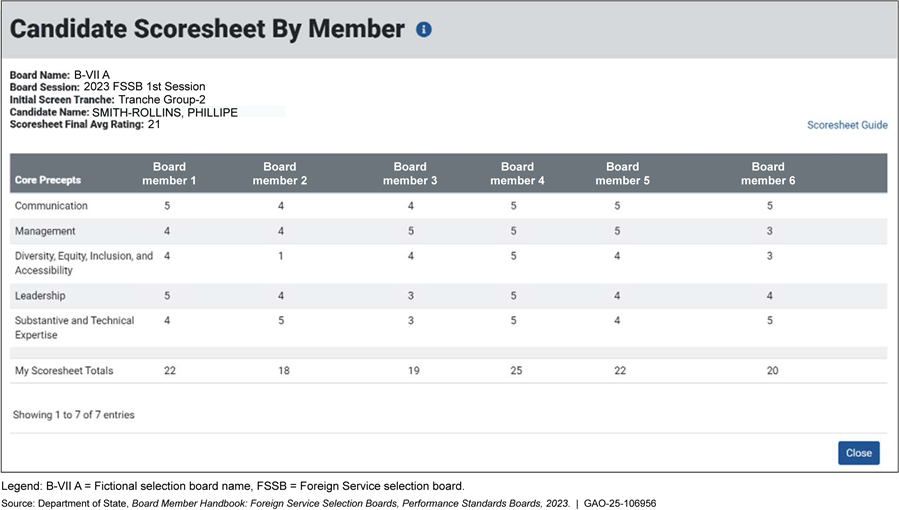

Second, State developed and implemented a rating tool, or scoring rubric, for selection board deliberations. According to GTM officials, the scoring rubric rates candidates against the core precepts, strengthens transparency in the promotion process, and provides feedback to candidates on how they scored in each of the core precepts. After reviewing candidates’ files, selection board members individually assign each candidate a score of one to five for each of the core precepts (see fig. 3). Selection boards weigh each of the core precepts equally. Previously, selection board members individually ranked each candidate using a rating scale of one through 10 and placed candidates into one of three categories—(1) recommended for promotion, (2) mid-rank, and (3) low-rank—without documenting or sharing how they assessed a candidate’s performance in each core precept. Selection board members now use the scoring rubric to rate candidates against the core precepts and provide average scores to the candidates.

Figure 3: Example of Candidate Scoring Rubric Used by Foreign Service Selection Boards, Introduced in 2023

Note: The information in this figure is intended solely to illustrate how boards use the scoring rubric or scoresheet to rate candidates for promotion. This scoresheet is an illustrative example. It does not refer to an actual selection board or candidate.

In December 2023, GTM used the new scoring rubric to provide additional feedback to candidates on promotions. Previously, GTM provided candidates with a scorecard showing their ranking compared with other candidates. Incorporating the results from the new scoring rubric, GTM provided the candidates’ average score across reviewers for each core precept and a comparison of the candidates with each other and with the promoted group.

State Commissioned a Study on Leading Practices to Inform Its Reform Process but Did Not Document Its Assessment of the Usefulness of These Practices

GTM implemented some changes that align with performance management and promotion leading practices identified in its commissioned study on this topic. However, it did not document its assessment of the usefulness of these practices for achieving its reform goals. In 2021, the Director General tasked GTM to develop a benchmark of the best performance management processes used by public and private sector entities and “assess their utility for the Foreign Service.” In response, GTM commissioned a third party to conduct a benchmarking study of comparable performance management and evaluation systems.[20] This benchmarking study highlights four leading practices and related key considerations to help State modernize its performance management process and increase the transparency and fairness of its promotions. (See table 2.)

Table 2: Leading Performance Management Practices from a 2021 Benchmarking Study Commissioned by State

|

Leading practices |

Key considerations when integrating the promotion

process into the performance |

|

Integrate organizational strategy and workforce planning into promotion criteria |

Organizations can use various organizational and individual factors, such as organizational strategy, workforce planning, and job complexity, to provide boards with uniform criteria to inform promotion decisions. |

|

Use performance management to drive diversity, equity, and inclusiona |

Organizations can use performance management to drive diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to further organizational goals by (1) holding supervisors accountable, (2) neutralizing bias to the extent possible, and (3) training the workforce on unconscious bias. |

|

Leverage data to simplify and streamline the promotion decision process |

Promotion decisions can be laborious and complicated, but performance data can provide promotion boards with quick and accurate depictions of an employee. |

|

Differentiate measuring criteria for promotability from performance |

Separating performance management and promotion processes helps organizations distinguish the goals of performance management from promotion. Organizations use performance management to drive individual employee performance based on indicators and metrics for the employee’s current position. For promotion, organizations determine who should advance to the next level given past performance as well as indicators of future success and organizational capability needs. |

Source: GAO analysis of a benchmarking study commissioned by the Department of State and conducted by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited in 2021. | GAO‑25‑106956

Note: The benchmarking study assessed the leading practices of similar organizations with comparable performance management and evaluation systems and provided recommendations for State’s Foreign Service reform initiative. The study sought to capture innovative and alternative approaches to the Foreign Service performance management and promotion process. We edited the key considerations language for clarity and readability.

aThe benchmarking study focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion, which State has expanded to include accessibility.

State commissioned this benchmarking study to identify performance and

promotion leading practices but has not documented its assessment of their

usefulness. We compared changes State made to its Foreign Service promotion

process with the key considerations of the four leading practices in the

benchmarking study. We found that two changes—the new DEIA core precept and the

development of a scoring rubric—generally reflect some, but not all, key

considerations of three of these leading practices, as follows.

First, the new DEIA core precept reflects some, but not all, key considerations of two of the leading practices—(1) integrating organizational strategy and workforce planning into promotion criteria and (2) using performance management to drive diversity, equity, and inclusion.

· Integrating organizational strategy and workforce planning into promotion criteria. GTM officials said they developed the DEIA core precept, in part, to align with State’s 2022–2026 Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility Strategic Plan to formalize DEIA performance expectations for employees at all levels, and to address the 2022 DEIA Climate Survey results. According to GTM, DEIA must be woven into the fabric of the department, framed as a national security priority, and serve as a lens through which all Foreign Service work is viewed. However, the leading practice on integrating organizational strategy recommends that GTM use metrics to track employee development over time while taking workforce planning into account, and the new DEIA core precept does not include such metrics.

· Using performance management to drive diversity, equity, and inclusion. GTM officials said the DEIA core precept also aligns with the leading practice on using performance management to drive diversity, equity, and inclusion by directing supervisors to hold themselves and their teams accountable for demonstrating DEIA in their work. However, this leading practice also mentions neutralizing bias and training the workforce on unconscious bias, which the DEIA core precept does not reflect.[21]

Second, the development of a scoring rubric for boards to rate candidates by core precepts reflects some, but not all, key considerations of the leading practice on leveraging data to simplify and streamline the promotion process. The benchmarking study states that data should be the common standard across selection board deliberations, streamlining the process to be more efficient while maintaining equity and accuracy in board decisions. While GTM is adding data to the promotion process through the scoring rubric, it is not necessarily streamlining the process because the selection boards generate the data during their deliberations. This leading practice also suggests that raters should generate performance data such as rating scores for the selection boards. However, according to GTM officials, raters and reviewers do not include scoring data in the employee evaluation reports that selection boards review. While the Foreign Service Act requires the selection boards to be the body that ranks employees for promotion, raters and reviewers could introduce a bias to the boards if they provide scores to candidates, according to GTM officials.[22]

GTM did not make changes that reflect the leading practice to separate performance management and promotion processes. GTM did not do so because the current process works well and prevents redundancies, according to GTM officials.

Although GTM made changes to the promotion process that generally reflect some, but not all, key considerations of three of the four leading practices, it did not document its assessment of the usefulness of the leading practices and key considerations for reforming the Foreign Service performance management and promotion process. GTM did not do so because the benchmarking study was not intended to prescribe specific actions for State to implement, according to GTM officials.

Federal internal control standards state that management should develop and maintain documentation to provide a means to retain organizational knowledge and mitigate the risk of having that knowledge limited to a few personnel.[23] Given that the benchmarking study identified leading practices from similar organizations, a written assessment of the usefulness of these practices could be a reference for future changes. Such documentation could provide transparency into the rationale for changes made to the promotion process, increasing employee confidence in the process.

State Has Generally Followed but Not Fully Documented Requirements for Selection Boards and Has Not Expanded Representation of Selection Board Members

State Has Generally Followed Its Requirements for the Composition of Selection Boards but Has Not Fully Documented How It Defined Them

GTM has generally followed the seven requirements for the composition of Foreign Service selection boards outlined in the Foreign Affairs Manual as State defined them. However, GTM did not fully document its more detailed definition of two of these requirements. Table 3 describes the Foreign Affairs Manual’s requirements for selection boards, how GTM defined these requirements, and whether GTM met the goal of each requirement and documented its definition. See appendix II for additional details.

Table 3: Status of Meeting the Goal of and Documenting GTM’s Policy Requirements for 101 Foreign Service Selection Boards, 2019–2023

|

|

Requirement from the Foreign Affairs Manual |

Requirement as specifically defined by GTM officials |

Did GTM meet the goal of the requirement, as specifically defined? |

Did State document the requirement as defined by GTM officials? |

|

Selection board composition requirements |

All selection boards must include a substantial number of women. |

At least one woman on a selection board. |

✓ |

✗ |

|

All selection boards must include a substantial number of members of minority groups. |

At least one person from a historically disadvantaged racial or ethnic group. |

✗ |

✗ |

|

Selection board member requirements |

Each selection board member ideally, should not serve more frequently than once every 3 years, and must not serve for 2 consecutive years.a |

GTM tries to avoid assigning volunteers to serve more frequently than once every 3 years. |

✗ |

✓ |

|

GTM does not assign volunteers to serve on consecutive boards. |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Each selection board member must, so far as possible, have a rank at least one class higher than that of the employees under review and, ideally, have spent a year at that higher grade. |

GTM assigns volunteers to boards at least one level above the candidates under review, with one exception.b |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Each selection board member must, so far as possible, have the depth and breadth of experience necessary to evaluate the employees designated for consideration by the boards. |

GTM officials said they determine “depth and breadth of experience” by requiring members to be at least one level higher than that of the candidates they review. |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Each generalist board has one member from each of the five career tracks—Consular, Economic, Political, Management, and Public Diplomacy. |

✗ |

✓ |

||

|

Each specialist board must include two specialists and two generalists.c |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Selection board member requirements (cont.) |

Each selection board member must, so far as possible, have a reputation for unbiased judgment of personnel and for perceptive evaluation of performance. |

GTM requires all board members to take and pass training, including on the procedural precepts, the core precepts, and mitigating unconscious bias, at the beginning of each annual selection board cycle. Board members also attend a week of training that includes reviewing practice performance files. Board members are trained on how to assess files using good judgement. |

✓ |

✓ |

|

GTM publishes the list of board members and instructions for promotion candidates to request recusal from being reviewed by a board member if the candidate believes that a board member may be unable to apply the promotion criteria fairly and without bias. GTM officials said that if they receive more than one request for recusal for one specific board member, they can replace that board member.d |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Five State offices vet potential board members to ensure there are no outstanding investigations or disciplinary letters in their file.e |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Each selection board member must, so far as possible, have a superior record of service. |

Five State offices vet potential board members to ensure there are no outstanding investigations or disciplinary letters in their file.e |

✓ |

✓ |

Legend:

GTM = Global Talent Management/Office of Performance Evaluation

✓ = Yes

✗ = No

Source: GAO analysis of Department of State data, documents, and interviews. | GAO‑25‑106956

Notes: Federal law and State’s Foreign Affairs Manual require each selection board to include a member of the public. GTM officials said they do not use public members to fulfill the other requirements of selection boards. Between 2019 and 2023, there were 101 boards, each generally composed of three to five members of the Foreign Service and one member of the public.

aWe verified compliance with requirements from 2019 through 2023, so we cannot report on compliance with this requirement for 2019 and 2020 board members who may have served in 2017 or 2018.

bState makes an exception to this requirement for selection boards for office management specialists because of the low number of employees in this position.

cIn 2024, GTM changed its interpretation of the requirement so that each specialist board must include specialists who have experience with the specialty under review.

dEmployees being reviewed by the selection board may email GTM a request for a board member to be recused with the reason they believe the board member cannot render an unbiased judgment. GTM officials said they would investigate these recusal requests before acting.

eThe Bureau of Diplomatic Security and Offices of Conduct Suitability and Discipline, Civil Rights and the Department of State Office of Inspector General vet the suitability of each volunteer. The Office of the Legal Advisor has vetted volunteers since 2021.

On the basis of GTM’s specific definitions of the Foreign Affairs Manual’s requirements

and our review of State data on the composition of each selection board, we

determined that the composition of 92 of the 101 selection boards convened from

2019 through 2023 followed the Foreign Affairs Manual’s requirements and

ideals as defined by GTM officials. GTM officials explained that nine boards

did not follow these requirements because GTM did not have enough appropriate

volunteers. Specifically:

· Two specialist boards did not meet the requirement to include a substantial number of members of historically disadvantaged racial or ethnic groups because they did not have enough volunteers from these groups, according to GTM officials.[24] GTM officials provide the list of volunteers to GTM’s Executive Office, which returns the list with an indication of whether the volunteer is (1) male or female and (2) in a historically disadvantaged racial or ethnic group.

· Two generalist boards also did not have full representation from each career track in 2020 and 2021. GTM officials told us that they prioritized meeting the representation requirements for women and historically disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups.

· Six boards did not meet State’s ideal of not having board members serve more frequently than once every 3 years.[25] GTM officials told us that they prioritized the other requirements and ensured they did not have any volunteers serving in 2 consecutive years.

GTM officials said that they have had difficulty soliciting enough volunteers to meet requirements, particularly higher-level specialists, given the limited number of employees in this group. GTM generally solicits volunteers through department-wide cables and contacts managers to assist in identifying additional volunteers to meet specific needs.

Federal internal control standards state that management should develop and maintain documentation to provide a means to retain organizational knowledge and mitigate the risk of having that knowledge limited to a few personnel.[26] However, GTM officials did not fully document how they specifically defined two of the seven requirements, relating to the number of women and minority group representatives on each board. GTM officials said they did not see a reason to document their definitions of the requirements because they need flexibility to have them change from year to year as they create the boards on the basis of their volunteer pool.

By documenting its more specific definitions of how it defines the Foreign Affairs Manual’s requirements for selection board members, GTM could refer to these definitions when composing future boards and revise as necessary. GTM could then better ensure that it designs the composition of selection boards with transparency, making progress toward achieving its goal to have a fair, inclusive, and effective promotion process.

State Has Not Expanded the Demographic Criteria for Selection Boards to Reflect the Composition of the Workforce, Including Ethnicity and Disability Status

Although State collects employee demographic information, GTM has not expanded the criteria for selection boards to more fully reflect the composition of the Foreign Service, including the ethnicity and disability status of employees. In accordance with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission regulations, State collects demographic information on all employees including sex, race, national origin, and disability.[27] State requests employees to self-identify their sex, race, national origin, and disability status.[28]

Our analysis shows that from 2019 through 2023, selection board members included higher representation of women and historically disadvantaged racial groups, but lower representation of Hispanics or Latinos and employees with disabilities, in comparison with the Foreign Service. Specifically:

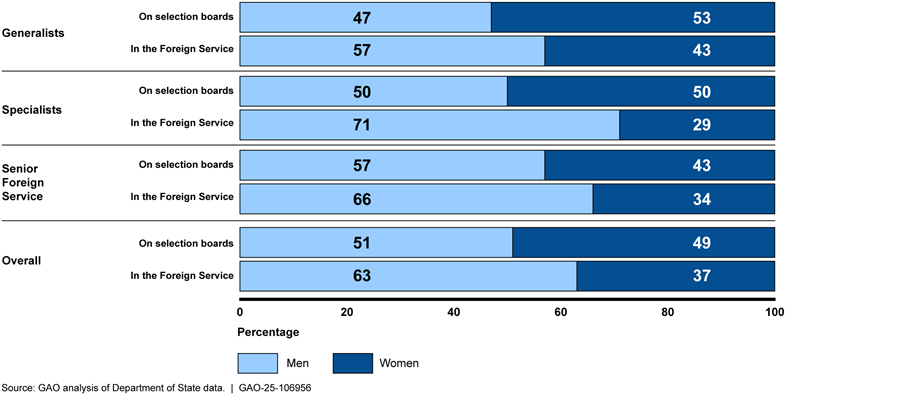

· Sex. The percentage of women serving on selection boards was higher than the percentage of women in the Foreign Service. Specifically, across all categories of employees (generalist, specialist, and Senior Foreign Service), on average, about 49 percent of selection board members were women, whereas 37 percent of the Foreign Service were women. For each employee category, women were represented on selection boards at higher percentages than women who worked in the Foreign Service, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Composition of Employees Serving on Foreign Service Selection Boards Compared with the Foreign Service Population by Sex, 2019–2023

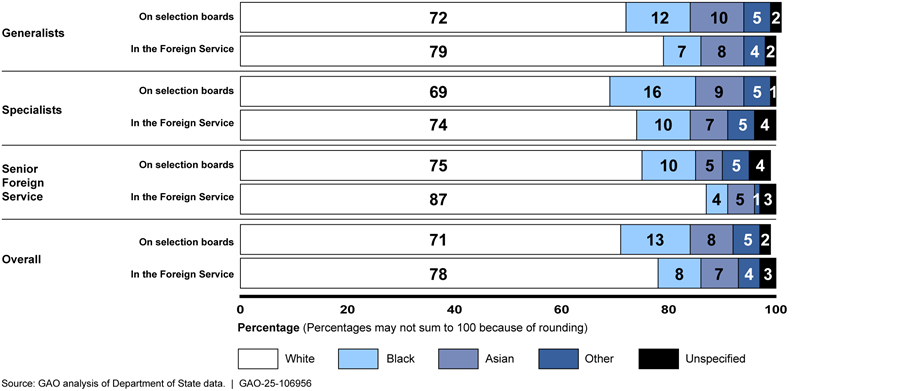

· Race. The percentage of employees from historically disadvantaged racial groups serving on selection boards was generally higher than the percentage of employees from historically disadvantaged racial groups in the Foreign Service. Specifically, across all categories of employees (generalist, specialist, and Senior Foreign Service), on average, about 27 percent of selection board members were from historically disadvantaged racial groups, whereas 20 percent of the Foreign Service were from historically disadvantaged racial groups.[29] For each employee category, employees from historically disadvantaged racial groups were generally represented on selection boards at higher percentages than employees from historically disadvantaged racial groups who worked in the Foreign Service, as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Composition of Employees Serving on Foreign Service Selection Boards Compared with the Foreign Service Population by Racial Group, 2019–2023

Note: In the “other” race category, we included American Indian, Native Hawaiian, and two or more races because we determined the size of the group was too small to ensure anonymity. Alaska Natives and other Pacific Islanders were not represented in State’s board member and workforce data. “Unspecified” includes individuals whose race is not identified. The Office of Personnel Management requests, but does not require, employees to provide information on their race.

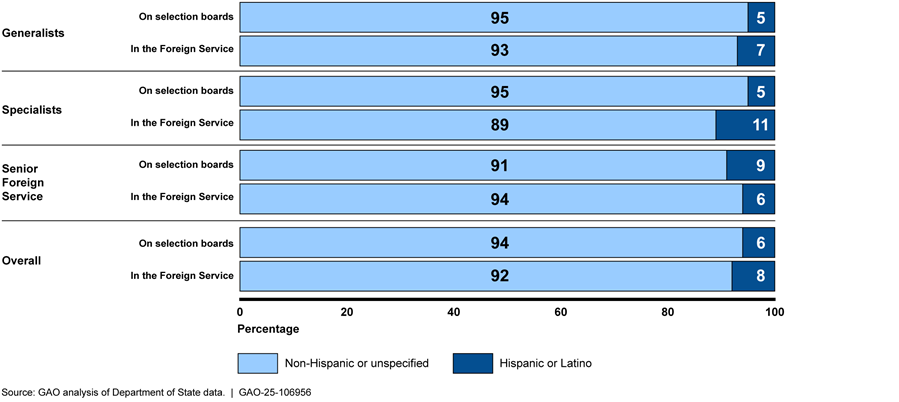

· Ethnicity.[30] For each employee category (generalist, specialist, and Senior Foreign Service), Hispanics or Latinos were generally represented on selection boards at lower percentages than Hispanics or Latinos who worked in the Foreign Service, as shown in figure 6. This gap was greatest among selection boards for specialists—on average, 5 percent of employees on specialist boards identified as Hispanic or Latino, whereas 11 percent of specialists in the Foreign Service identified as Hispanic or Latino. The reverse was true for Senior Foreign Service, where 9 percent of employees on such boards identified as Hispanic or Latino, whereas 6 percent of Senior Foreign Service officers identified as Hispanic or Latino.

Figure 6: Composition of Employees Serving on Foreign Service Selection Boards Compared with the Foreign Service Population by Ethnic Group, 2019–2023

Note: The Office of Personnel Management requests, but does not require, employees to provide information on their ethnicity.

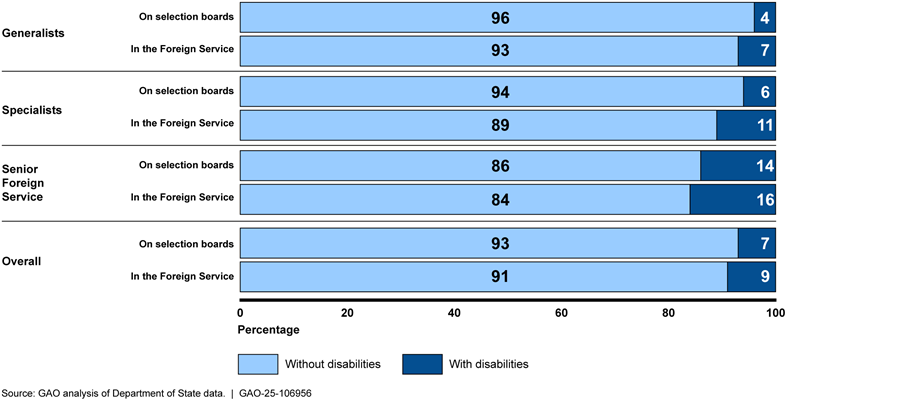

· Disability. The percentage of employees with disabilities serving on selection boards was lower than the percentage of employees with disabilities in the Foreign Service. Specifically, on average, about 7 percent of selection board members were identified as having disabilities, whereas 9 percent of the Foreign Service were identified as having disabilities. This gap was greatest among selection boards for specialists—6 percent of employees on specialist boards were identified as having disabilities, whereas 11 percent of specialists in the Foreign Service were identified as having disabilities. For each employee category (generalist, specialist, and Senior Foreign Service), employees with disabilities were represented on selection boards at lower percentages than employees with disabilities in the Foreign Service, as shown in figure 7.

Figure 7: Composition of Employees Serving on Foreign Service Selection Boards Compared with the Foreign Service Population by Disability Status, 2019–2023

Note: Employees can self-identify as having a disability, but disclosure is generally not required.

According to a leading practice for DEIA management, organizations can hold themselves accountable for DEIA progress by including performance evaluators (in this case, selection board members) from diverse backgrounds that reflect the overall demographic composition of the staff involved (in this case, the Foreign Service).[31] This practice allows varied perspectives in measuring employee performance and assessing employees for promotion and contributes to the perception of fairness throughout the organization.

GTM officials said they have focused on creating selection boards with at least one woman and at least one representative from a historically disadvantaged racial or ethnic group, rather than seeking selection board members that proportionally represent the demographics of the Foreign Service. Further, the officials said they have not considered disability status when determining selection board composition because employees are not required to self-identify such status. State collects information on employees who have disclosed their disability status and establishes specific numerical goals for increasing the participation of employees with specific disabilities.[32] However, considering how best to include demographic representation on selection boards, specifically for ethnicity and disability status, in relation to the Foreign Service would better position State to include varied perspectives in assessing employees for promotion and contribute to a perception of fairness. Doing so would also help advance State’s goal of a fair, inclusive, and effective process.

Conclusions

State has launched a reform initiative to transform the Foreign Service promotion process into one more worthy of confidence in how it develops and promotes its employees. GTM’s commissioned benchmarking study has helped guide some of the changes under this initiative, but GTM has not documented the usefulness of the study’s leading practices, which would help explain why State took certain actions but not others. Such a written assessment could help GTM retain institutional knowledge when considering any future changes to its promotion process.

State has established requirements for the composition of each selection board, but GTM has not consistently documented how it defines them from year to year. Documenting definitions could help GTM better ensure it is preserving institutional practices and understanding of prior decisions as the promotion process evolves. Doing so could also help GTM better ensure that it designs the composition of selection boards with transparency so that the department operates in a fair, inclusive, and effective manner.

State has worked toward its commitment to increase representation of diverse groups in the Foreign Service but has not sought demographic representation of selection board members compared with the workforce. Considering how best to ensure selection board members are more representative of the Foreign Service, particularly with regard to ethnicity and disability status, could allow the department to include more varied perspectives and increase the perception of fairness in its promotion process.

Recommendations

We are making three recommendations to State:

The Secretary of State should ensure that the Director General of the Foreign Service and Director of Global Talent documents its assessment of the usefulness of the leading practices identified in the benchmarking study for its reform initiative. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of State should ensure that the Director General of the Foreign Service and Director of Global Talent documents how GTM specifically defines the established requirements for selection board members. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of State should ensure that the Director General of the Foreign Service and Director of Global Talent consider how best to make certain that selection board member composition better reflects the Foreign Service, including ethnicity and disability status. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to State for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix III, State agreed with our three recommendations and outlined steps it would take to address them. With regard to recommendation 1, State said it would document its written assessment of the usefulness of the leading practices identified in the benchmarking study and use it to inform future changes to the promotion process. With regard to recommendation 2, State said it is taking steps to document in the Foreign Affairs Manual how it defines the established requirements for its selection board members. With regard to recommendation 3, State said it would continue to explore strategies to best reflect demographic representation of the workforce on selection boards and noted various actions it planned to take. State also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Secretary of State. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff members have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7279 or elhodirin@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Nagla’a El-Hodiri

Director, International Affairs and Trade

List of Committees

The Honorable Benjamin Cardin

Chairman

Committee on Foreign Relations

United States Senate

The Honorable James E. Risch

Ranking Member

Committee on Foreign Relations

United States Senate

The Honorable Michael McCaul

Chairman

Committee on Foreign Affairs

House of Representatives

The Honorable Gregory Meeks

Ranking Member

Committee on Foreign Affairs

House of Representatives

The Office of Performance Evaluation in the Department of State’s Bureau of Global Talent Management (GTM) administers the Foreign Service performance management and promotion process. This report examines the extent to which State has (1) made changes to its Foreign Service promotion process since 2020 and documented its assessment of the usefulness of relevant leading practices and (2) followed its requirements for the composition of selection boards and ensured demographic diversity on these boards.

To examine the extent to which State made changes to its Foreign Service promotion process and documented its assessment of relevant leading practices, we reviewed State’s core precepts; procedural precepts; relevant cables; Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) Climate survey results; and selection board handbooks. We reviewed changes since 2020 because GTM launched its Performance Management Reform Initiative in 2020. We also reviewed documents related to this initiative, including the benchmarking study State commissioned in 2020. This study identified relevant performance management and promotion leading practices of similar organizations to evaluate the Foreign Service performance management processes.[33]

We compared changes State made to its Foreign Service promotion process with the key considerations of the four leading practices in the benchmarking study. We also compared the extent to which GTM’s changes are consistent with the four leading practices identified in the benchmarking study. We compared GTM’s efforts with federal internal control standards on developing and maintaining documentation to retain organizational knowledge and mitigate the risk of having that knowledge limited to a few personnel.[34]

To examine the extent to which State has followed its requirements for the composition of selection boards, we reviewed the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended, the Foreign Affairs Manual, and cables to identify State’s requirements and determine how GTM defines the requirements for selection boards. We compared State’s efforts to document its definitions with federal internal control standards on developing and maintaining documentation to retain organizational knowledge.[35] We analyzed State’s personnel data from its Global Employment Management System (GEMS) database on selection board members from 2019 through 2023 to compare the composition of the selection boards with State’s requirements as defined by GTM. We reviewed data on selection board members’ sex, race, ethnicity, disability status, grade, and career track, and the year or years in which they served on the boards. We verified that the selection board members’ names and posts announced in cables matched the data State provided on selection board members in GEMS. We determined State’s workforce composition data to be sufficiently reliable for summarizing the composition of selection boards.[36]

We also reviewed our nine leading practices on DEIA to identify the one that was relevant to State’s promotion process and compared it with State’s requirements, including a leading practice on accountability.[37] This leading practice explains that one way that organizations can hold themselves accountable for progress on DEIA is by including performance evaluators (in this case, selection board members) of diverse backgrounds who reflect the overall demographic composition of the staff involved (in this case, State’s Foreign Service). Using demographic data from GEMS, we compared the composition of the selection boards with that of the Foreign Service. We also determined State’s workforce composition data to be sufficiently reliable for presenting summary statistics on the demographics of the Foreign Service. We analyzed the numbers and percentages of board members by sex, race, ethnicity, and disability status from 2019 through 2023. In addition, we analyzed these numbers and percentages by generalists, specialists, and Senior Foreign Service members.

For the purposes of our reporting objectives, the term “historically disadvantaged racial or ethnic groups” corresponds to instances where the racial or ethnic group is neither non-Hispanic White nor unspecified. The Hispanic or Latino group included Hispanics or Latinos of all races. The racial groups included White, Black, Asian, other, and unspecified. The “other” group included American Indian, Native Hawaiian, and two or more races.[38] We could not present historically disadvantaged racial or ethnic groups combined because of data limitations. For disability status, we included both targeted and non-targeted disabilities.[39]

For both objectives, we interviewed officials involved with State’s promotion process, including officials from GTM and State’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion. We also interviewed representatives from the American Foreign Service Association to obtain their perspectives on how State’s promotion process compares with the process of other agencies who have Foreign Service personnel. In addition, we interviewed officials from State’s Office of the Inspector General about their report on the selection boards’ public members.[40]

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Table 4: Status of Meeting the Goal of and Documenting GTM’s Policy Requirements for 101 Foreign Service Selection Boards, 2019–2023

|

|

Requirement from the Foreign Affairs Manual |

Requirement as specifically defined by GTM officials |

Did GTM meet the goal of the requirement, as

specifically defined, |

Did State document the requirement as defined by GTM officials, and where? |

|

Selection board composition requirements |

All selection boards must include a substantial number of women. |

At least one woman on a selection board. |

Yes. Women constituted about 49 percent of all board members. |

No. |

|

All selection boards must include a substantial number of members of minority groups. |

At least one person from a historically disadvantaged racial or ethnic group. |

No. Two boards did not include any people from historically disadvantaged racial or ethnic groups. |

No. |

|

|

Selection board member requirements |

Each selection board member ideally, should not serve more frequently than once every 3 years, and must not serve for 2 consecutive years.a |

GTM tries to avoid assigning volunteers to serve more frequently than once every 3 years. |

No. Six boards included people who had served more frequently than once every 3 years. |

Yes, in the Foreign Affairs Manual

|

|

GTM does not assign volunteers to serve on consecutive boards. |

Yes. Selection board members did not serve in consecutive years. |

Yes, in the Foreign Affairs Manual. |

||

|

Each selection board member must, so far as possible, have a rank at least one class higher than that of the employees under review and, ideally, have spent a year at that higher grade. |

GTM assigns volunteers to boards at least one level above the candidates under review, with one exception.b |

Yes. Selection board members were at least one level above the employees under review. |

Yes, in the Foreign Affairs Manual. |

|

|

Each selection board member must, so far as possible, have the depth and breadth of experience necessary to evaluate the employees designated for consideration by the boards. |

GTM officials said they determine “depth and breadth of experience” by requiring members to be at least one level higher than that of the candidates they review. |

Yes. Selection board members were at least one level above the employees under review. |

Yes, in department-wide cables. |

|

|

Each generalist board has one member from each of the five career tracks—Consular, Economic, Political, Management, and Public Diplomacy. |

No. Two generalist boards did not have full representation from each career track. |

Yes, in department-wide cables. |

||

|

Each specialist board must include two specialists and two generalists.c |

Yes. Each specialist board included two specialists and two generalists. |

Yes, in department-wide cables. |

||

|

Selection board member requirements (cont.) |

Each selection board member must, so far as possible, have a reputation for unbiased judgment of personnel and for perceptive evaluation of performance. |

GTM requires all board members to take and pass training including on the procedural precepts, the core precepts, and mitigating unconscious bias at the beginning of each annual selection board cycle. Board members also attend a week of training that includes reviewing practice performance files. Board members are trained on how to assess files using good judgement. |

Yes. Each selection board member met the requirement to pass the required classes, according to GTM officials

|

Yes, in department-wide cables and selection board training materials

|

|

GTM publishes the list of board members and instructions for promotion candidates to request recusal from being reviewed by a board member if the candidate believes that a board member may be unable to apply the promotion criteria fairly and without bias. GTM officials said that if they receive more than one request for recusal for one specific board member, they can replace that board member.d |

Yes. GTM officials said they have rarely replaced board members because they rarely received multiple requests to recuse any specific board member. |

Yes. Recusal request instructions are documented in cables

|

||

|

Five State offices vet potential board members to ensure there are no outstanding investigations or disciplinary letters in their file.e |

Yes. GTM officials said they vetted all selection board members and considered all raised concerns. |

Yes, in department-wide cables and an internal memo. |

||

|

Each selection board member must, so far as possible, have a superior record of service. |

Five State offices vet potential board members to ensure there are no outstanding investigations or disciplinary letters in their file.e |

Yes. GTM officials said they vetted all selection board members and considered all raised concerns. |

Yes, in department-wide cables and an internal memo. |

Legend: GTM = Global Talent Management/Office of Performance Evaluation.

Source: GAO analysis of Department of State data, documents, and interviews. | GAO‑25‑106956

Notes: Federal law and State’s Foreign Affairs Manual require each selection board to include a member of the public. GTM officials said they do not use public members to fulfill the other requirements of selection boards. Between 2019 and 2023, there were 101 boards, each generally composed of three to five members of the Foreign Service and one member of the public.

aWe verified compliance with requirements from 2019 through 2023, so we cannot report on compliance with this requirement for 2019 and 2020 board members who may have served in 2017 or 2018.

bState makes an exception to this requirement for selection boards for office management specialists because of the low number of employees in this position.

cIn 2024, GTM changed its interpretation of the requirement so that each specialist board must include specialists who have experience with the specialty under review.

dEmployees being reviewed by the selection board may email GTM a request for a board member to be recused with the reason they believe the board member cannot render an unbiased judgment. GTM officials said they would investigate these recusal requests before acting.

eThe Bureau of Diplomatic Security and Offices of Conduct Suitability and Discipline, Civil Rights, and Inspector General vet the suitability of each volunteer. The Office of the Legal Advisor has vetted volunteers since 2021.

GAO Contact

Nagla’a El-Hodiri (202) 512-7279 or elhodirin@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgements

In addition to the contact named above, Cheryl Goodman (Assistant Director), Alana Miller (Analyst-in-Charge), Abena Serwaa, Debbie Chung, Neil Doherty, Kara Marshall, and Peng Zhang made key contributions to this report. Ashley Alley, Shea Bader, Renee Caputo, Nicole Hewitt, Michael Murray, Gabriel Nelson, Moon Parks, Terry Richardson, and Miranda Riemer provided additional assistance.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]In this report, historically disadvantaged racial or ethnic groups include employees who identify in a group other than non-Hispanic White or unspecified. GAO, State Department: Additional Steps Are Needed to Identify Potential Barriers to Diversity, GAO‑20‑237 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 27, 2020).

[2]Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, “Performance Management (PM) Benchmarking” (unpublished PowerPoint presentation, Mar. 17, 2021).

[3]James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, Pub. L. No. 117-263, § 9213, 136 Stat. 2395, 3875 (2022).

[4]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014), Principle 3, Establish Structure, Responsibility, and Authority.

[5]Department of State, “Promotion of Members of the Foreign Service,” 3 Foreign Affairs Manual 2320 (December 2022).

[6]GAO‑14‑704G, Principle 3, Establish Structure, Responsibility, and Authority.

[7]GAO, Federal Workforce: Leading Practices Related to Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility, GAO‑24‑106684 (Washington, D.C.: June 2024). We identified this relevant leading practice on accountability from among nine leading practices identified in GAO‑24‑106684. This report identifies leading practices in the categories of (1) top leadership commitment, (2) DEIA as part of an organization’s strategic plan, (3) measurement, (4) accountability, (5) succession planning, (6) recruitment, (7) employee involvement, (8) DEIA training, and (9) communication.

[8]The Foreign Service Act of 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-465, § 602, 94 Stat. 2095 (Oct. 17, 1980), codified as amended at 22 U.S.C. § 4001 et seq. Department of State, 3 Foreign Affairs Manual 2320. According to the procedural precepts, the regulatory language in the procedural precepts is considered governing if it varies from that in the Foreign Affairs Manual or Foreign Affairs Handbooks.

[9]State considers performance management and promotion to be part of the same process. We refer to the Office of Performance Evaluation in State’s Bureau of Global Talent Management as GTM unless otherwise noted.

[10]This report focuses on Foreign Service employees who served on selection boards because State’s Inspector General reported on GTM’s process for selecting public members. Department of State, Office of the Inspector General, Review of the Recruitment and Selection Process for Public Members of Foreign Service Selection Boards, ESP-22-02 (Washington, D.C.: May 2022).

[11]Foreign Service generalists help formulate and implement U.S. foreign policy and are assigned to work in one of five career tracks: consular, economic, management, political, or public diplomacy. Foreign Service specialists support and maintain the functioning of overseas posts and serve in 25 different skill groups, filling positions such as security officer or information management specialist.

[12]We reported on this process in 2013, and it has largely remained the same. GAO, Foreign Affairs Management: State Department Has Strengthened Foreign Service Promotion Process Internal Controls, but Documentation Gaps Remain, GAO‑13‑654 (Washington, D.C.: July 2013).

[13]The American Foreign Service Association is the exclusive representative for the Foreign Service. It is the principal advocate for the long-term institutional wellbeing of the professional career Foreign Service and is responsible for safeguarding the interests of its members.

[14]The Performance Standards Boards determine whether employees should be separated from State for failure to meet the performance standards of their level.

[15]Candidates can be temporarily removed for various reasons, such as an ongoing investigation, or permanently removed because of a change in personnel status, such as retirement or resignation. See 3 Foreign Affairs Manual 2327–2328.

[16]Foreign Service employees filed fewer than 70 grievances related to or potentially related to promotions each year from 2019 through 2023, according to State. Foreign Service employees can also file complaints of discrimination based on race, sex, disability, and certain other characteristics with State’s Office of Civil Rights if they believe they were not selected for promotion on that basis. Employees filed fewer than 30 such complaints related to the promotion process each year from 2019 through 2022, according to State.

[17]GTM’s initiative reflects the Secretary of State’s Modernization of American Diplomacy initiative, which was launched in 2021. See Department of State, Secretary Antony J. Blinken on the Modernization of American Diplomacy (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 27, 2021). GTM tracked its progress in implementing changes that specifically supported the modernization initiative’s effort to build and retain a diverse, dynamic, and entrepreneurial workforce and equip and empower employees to succeed.

[18]GTM officials said they have systematically collected and implemented actions to address selection board and employee feedback. For example, after the 2022 board deliberations, board members recommended that GTM provide learning tools to assist employees when writing their narratives to demonstrate their performance under the core precepts. In response, GTM hosted a series of workshops and provided learning videos.

[19]Hardship posts might have conditions that threaten the health or well-being of an employee, such as unhealthy levels of pollution, high crime, or limited access to medical care.

[20]Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, Performance Management Benchmarking.

[21]According to GTM, the department offers trainings, such as on mitigating unconscious bias, to all employees to help advance DEIA.

[22]Section 601 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended, provides that promotion of Foreign Service employees shall be based on the recommendations and rankings of the selection boards. 22 U.S.C. § 4001(b).

[23]GAO‑14‑704G, Principle 3, Establish Structure, Responsibility, and Authority.

[24]The Foreign Service Act of 1980 and the Foreign Affairs Manual require each selection board to include a substantial number of “members of minority groups.” See 22 U.S.C. § 4002(b) and 3 FAM 226.1-1. GTM specifically referred to “members of minority groups” as members of historically disadvantaged racial or ethnic groups.

[25]One of the generalist boards in 2021 did not have full representation from each career track and had a board member who served more frequently than once every 3 years. We verified compliance with requirements from 2019 through 2023, so we cannot report on compliance with this requirement for 2019 and 2020 board members who may have served in 2017 or 2018.

[26]GAO‑14‑704G, Principle 3, Establish Structure, Responsibility, and Authority.

[27]29 C.F.R. § 1614.601.

[28]If an employee does not self-identify, State officials must identify the employee’s sex, race, and national origin on the basis of visual observation. Agencies must require employees hired through the Schedule A hiring authority for people with disabilities to provide proof of their disability (5 C.F.R. § 213.3102(u)).

[29]In this report, we refer to Black, Asian, and other non-White race groups across ethnicities as historically disadvantaged racial groups.

[30]In this report, we use the term ethnicity rather than national origin for consistency with State-reported data. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s guidance specifically includes ethnicity as a subset of national origin. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission defines national origin discrimination “broadly as including, but not limited to, the denial of equal employment opportunity because of an individual’s, or his or her ancestor’s, place of origin; or because an individual has the physical, cultural or linguistic characteristics of a national origin group.” 29 C.F.R. § 1606.1.

[32]Equal Employment Opportunity Commission regulations (29 C.F.R. § 1614.203(e)) and Management Directive 715 also require agencies to describe a plan to improve advancement of employees with disabilities.

[33]We reviewed other best practices related to promotion and determined that State’s benchmarking study contained the most relevant and comprehensive practices. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, “Performance Management (PM) Benchmarking” (unpublished PowerPoint presentation, Mar. 17, 2021).