OLDER WORKERS

Employment Rates Rebounded and Personal Finances Remained Steady Following Pandemic

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Kris Nguyen at nguyentt@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106962, a report to congressional committees

Employment Rates Rebounded and Personal Finances Remained Steady Following Pandemic

Why GAO Did This Study

The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant nationwide economic disruptions. Older adults, particularly those close to or already in retirement, may have faced a greater financial burden because they did not have sufficient time to rebuild retirement savings.

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to monitor federal efforts in response to the pandemic. This report describes: (1) how trends in older workers’ employment status and duration varied from 2017-2023 and demographic differences among worker subpopulations; (2) how older workers’ personal finances, including Social Security benefit claiming rates, changed; and (3) what policy options experts identified that could enhance the outcomes of discouraged or unemployed older workers.

GAO used Current Population Survey monthly data from 2017 to 2023 to analyze labor force participation rates and employment trends for older and younger workers. Using the most recent data available, GAO examined retirement account balances and total assets held by older households using Survey of Consumer Finances data and analyzed claims for retirement benefits using Social Security Administration administrative data. GAO also sent a written questionnaire to 32 experts, asking them to identify policies likely to help discouraged or unemployed older workers.

GAO did not make recommendations in this report.

What GAO Found

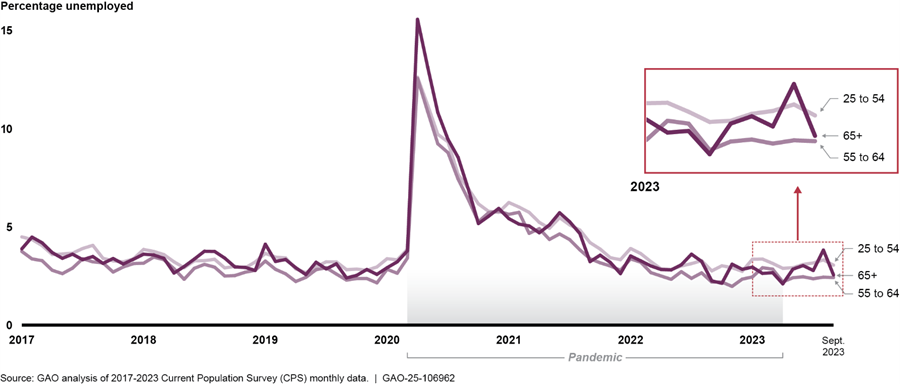

Across demographic groups, labor market outcomes for older workers were generally resilient in the COVID-19 pandemic’s wake, with older workers’ employment outcomes returning to pre-pandemic levels after an initial spike in unemployment. The unemployment rate for workers aged 55–64 peaked at 12.6 percent in April 2020 and had returned to its pre-pandemic level of 2.2 percent by April 2023, according to GAO’s analysis of Current Population Survey data from 2017 to 2023. Further, older workers were more likely to report that they were unemployed because they had lost their job or been laid off, and they were also more likely to have exited the labor force by retiring. Younger workers (aged 25–54) were more likely to report that they were unemployed because a temporary job had ended or because they left a job. GAO found that existing differences by demographic group generally persisted, such as more highly educated older workers having higher labor force participation.

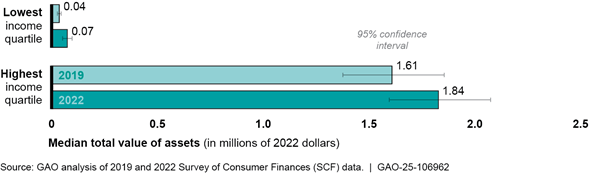

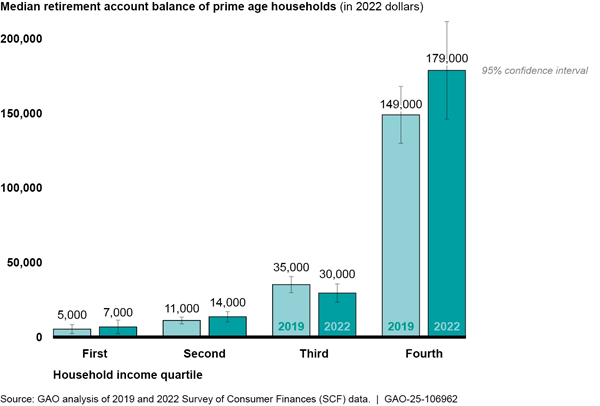

During the pandemic, older workers’ personal finances generally remained relatively steady. The rate of Social Security retirement benefit claims by workers who were near the full retirement age decreased during the first 3 months of the pandemic, according to GAO’s analysis of Social Security Administration data. In late 2020, the rate of benefit claiming for those near full retirement age increased, eventually exceeding pre-pandemic levels, according to GAO’s analysis. The prevalence of households aged 55 or over that had retirement accounts, and the value of those accounts, held relatively steady between 2019 and 2022, according to GAO’s analysis of Survey of Consumer Finances data. However, differences persisted in the value of assets held by income quartile (see figure), as well as by some demographic groups, including differences by education, race, and gender.

The 25 experts who responded to GAO’s written questionnaire generally favored policy options that could most effectively boost older workers’ employability. Among the options favored by 12 or more experts was a policy option suggesting that the Department of Labor identify and report on the legal, regulatory, logistical, or other barriers to the employment of older workers. Experts also favored a policy option that the Department of Labor offer targeted support, such as improving the agency’s existing job-search assistance programs for older job seekers.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 13, 2025

Congressional Committees

The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant economic disruptions, including widespread unemployment, temporary business closures, and other reductions in economic activity during the resulting national emergency that lasted from March 2020 to April 2023.[1] In April 2020, 1 month after the emergency began, the percentage of the U.S. population that was employed reached the lowest level ever measured, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). While the pandemic affected all age groups, older adults (age 55 and older), particularly those who are close to or already in retirement, may have faced a greater burden because they may have had insufficient time to rebuild retirement savings and may have experienced increased medical costs. As our previous work has shown, while older workers are less likely to be unemployed than workers in younger age groups, they are also less likely to find other employment when they lose a job.[2]

We are conducting this work in response to a provision in the CARES Act to monitor and oversee the federal government’s efforts to prepare for, respond to, and recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.[3] This report addresses the following: (1) How did trends in older workers’ employment status vary from 2017 to 2023, and to what extent were there demographic differences among worker subpopulations? (2) How did older workers’ personal finances, including their Social Security benefit claiming rates, change, if at all, during the pandemic? (3) What policy options did experts identify as likely to enhance the employment outcomes of discouraged or unemployed older workers?

To identify trends in older workers’ employment status, including any demographic differences among worker subpopulations, we analyzed monthly data from 2017 through 2023 from BLS’s Current Population Survey (CPS). To compare these trends across age groups, we organized the data using the following age groupings: people aged 25 to 54, who are defined by BLS as the prime working-age population; people aged 55 to 64, who are the older working population that is nearing full retirement age; and people aged 65 and older, who are more likely to be retired or retiring soon (see text box).

|

Age Groups in This Report Unless otherwise indicated, we use the following age groupings in this report: Prime-age workforce: Workers aged 25 to 54 Older workers: Workers aged 55 to 64 Oldest workers: Workers aged 65 and older |

Source: GAO. I GAO‑25‑106962

We also analyzed data from the 2008, 2010, 2020, and 2022 Displaced Worker,

Employee Tenure, and Occupational Mobility Supplements (Displaced Worker

Supplement) to the Current Population Survey, to estimate the extent to which

displaced workers reentered the workforce, remained unemployed, or retired, among

other things.[4]

To examine how older workers’ personal finances, including their Social Security benefit claiming rates, changed during the pandemic, we obtained and analyzed Social Security Administration (SSA) administrative data from 2018 to 2023—the most recent available at the time of our analysis. We determined the number and estimated the rate of claims, by claimant age, at which individuals opted to claim Social Security retirement or disability benefits. We compared the results of our retirement benefit claiming rates with information we analyzed on Unemployment Insurance claim data during the same period.

In addition, we analyzed Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) data from 2019 and 2022 to estimate retirement account participation and balances, asset holdings, and other financial information for households.[5] For comparison purposes, we analyzed older households based on their household income and divided them into four income quartiles, with the first quartile representing households with the lowest income level and the fourth quartile representing those with the highest income level during those years. We analyzed SCF data to estimate the retirement account prevalence and median balances for older households (55 and older) with a positive retirement account balance. We also analyzed differences among demographic groups in assets held by older households (aged 55 to 64) and oldest households (aged 65 and older) by their income quartiles across income, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, and gender. All dollar values are adjusted for inflation to 2022 dollars.

For each dataset referenced above, we conducted a data reliability assessment of selected variables by conducting electronic data tests for completeness and accuracy, reviewing documentation such as codebooks on the dataset, and interviewing knowledgeable agency officials. Unless otherwise noted, we found each of these datasets to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

To provide information on policy options that experts identified as likely to enhance the employment outcomes of discouraged or unemployed older workers, we developed a written questionnaire describing 30 policy options focused on improving employment outcomes for older workers.[6] We identified these policy options in our prior work, from a recent National Academy of Social Insurance report, and through discussions with knowledgeable researchers.[7] We excluded policy options that address SSA or its benefit programs, any federal agency other than the Department of Labor (DOL), the federal-state Unemployment Insurance program, and any other state-level options. We also excluded policy options aimed at addressing attitudinal challenges among employers, such as employers’ opinions about age discrimination or employer-held stereotypes that older adults are difficult to train or less productive than younger workers. Attitudinal challenges among employers’ opinions may include age discrimination or employer-held stereotypes that diminish older job seekers’ prospects; certain actions are prohibited under federal law, but we did not attempt to assess the extent to which these actions are prevalent in the workforce or identify potential remedies in this report.[8]

We distributed this questionnaire to 32 experts from think tanks, universities, and nonprofits, and we received responses from 25 of them.[9] We asked the respondents to rank the policy options from not effective to highly effective. The sum of rankings reflects the opinions of the experts, and no empirical testing was done to verify whether any individual policy option would be effective. We supplemented our data analysis with semi-structured interviews of seven policy experts who we selected to provide a range of perspectives and experiences. We selected the seven experts we interviewed as a subset of the 25 who responded to our questionnaire.

For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

How Employment and Unemployment Are Measured

DOL’s BLS works with the Census Bureau to produce the CPS.[10] The CPS is the primary source of federal government statistics on the labor force, including employment and unemployment in the United States. The basic monthly survey collects information on employment (e.g., employment status, occupation, and industry) and demographic characteristics to assess the health of the labor market and overall economy.

In addition, the Displaced Worker Supplement is administered every 2 years as a supplement to the CPS. Displaced workers are wage and salary workers 20 years of age and older who lost or left a job because their plant or company closed or moved, there was insufficient work for them to do, or their position or shift was abolished (see text box). For example, for the 2022 Displaced Worker Supplement, people are identified as displaced if they lost or left their job for one of the specified reasons between January 2019 and December 2021.

|

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Definitions for Types of Unemployed and Underemployed Workers Unemployed workers: Jobless persons who are available to take a job and who have actively sought work in the past 4 weeks. An unemployed worker may or may not be a displaced worker. Displaced workers: Persons who lost or left jobs within the past 3 years for the following reasons: their plant or company closed or moved, there was insufficient work for them to do, their position or shift was abolished, or similar economic reasons. Displaced workers may be unemployed, employed, or not in the labor market at the time of the survey. Underutilized workers: Workers who are either marginally attached to the workforce or employed part-time for economic reasons. · Marginally attached workers: Workers who are not in the labor force, who want and are available for work, and who have actively searched for work in the past 12 months. They are not counted as unemployed because they had not actively searched for work in the prior 4 weeks. They include these subsets of workers: · Discouraged workers: A subset of the marginally attached workers who indicate that they have not searched for work in the prior 4 weeks for the specific reason that they believed no jobs were available for them. · Other people marginally attached to the labor force: Marginally attached workers who are available for work but are not looking for work due to some reason other than that they believed no jobs were available for them (discouraged). · Workers employed part-time for economic reasons: Workers who are counted as employed and are employed less than 35 hours per week and who want and are available for, but are unable to find, full-time work, as well as those individuals who prefer full-time work but who had their hours reduced by their employer because of business conditions. |

Source: BLS. | GAO‑25‑106962

Selected Sources of Retirement Income for Older Workers

Personal finances such as income from employer-sponsored retirement plans, private savings, and Social Security retirement benefits are important sources of retirement income for many older workers.

Private Pensions and Defined Contribution Retirement Accounts

Individuals in the United States are increasingly responsible for their retirement security because the nation has moved from a primarily defined benefit to a primarily defined contribution retirement account system over the last several decades. Defined benefit pension plans traditionally provide a benefit for the life of the participant based on a formula that typically takes into account factors such as a worker’s salary, years of service, and age at retirement. With defined contribution retirement accounts, participants must often decide whether to participate, how much to contribute, and how to invest their savings to balance risks and returns. Defined contribution retirement account savings include assets from workplace retirement plans, such as 401(k) plans, and from individual retirement accounts (IRA).

Social Security

Social Security is a fundamental source of income for millions of retirees and their families.[11] Social Security retirement benefits are paid under the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program administered by SSA.[12] To qualify for retirement benefits under the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance program, workers must typically have earned a minimum of 40 quarters of coverage over their lifetime.[13] To qualify for disability benefits, workers generally need fewer quarters of coverage, but they must have recent work activity. The level of retirement benefits that an individual will receive depends on factors such as their work and earnings history and the age at which the beneficiary chooses to begin receiving benefits. For the purposes of this report, we defined the claiming rate for benefits as the ratio of the number of workers filing a claim for SSA benefits to the estimated number of eligible workers in the same period.

Generally, individuals may begin receiving Social Security retirement benefits at age 62; however, the payments will be lower than if they wait to receive benefits at their full retirement age, which varies from 65 to 67, depending on the individual’s birth year.[14] In contrast, the monthly benefit is higher for workers who opt to delay receiving benefits beyond their full retirement age, up to age 70.

Social Security also provides benefits to eligible individuals who have qualifying disabilities and their eligible family members.

Unemployment Insurance

The federal-state Unemployment Insurance system helps certain unemployed workers, including unemployed older workers. The Unemployment Insurance system provides eligible unemployed individuals with temporary benefits that partially replace their lost wages. The Unemployment Insurance system includes a federal-state program that is generally funded through federal and state employer payroll taxes. States determine eligibility requirements and benefit amounts within federal parameters. Unemployment Insurance benefits are generally available to eligible unemployed workers for up to 26 weeks, or approximately 6 months. Extended benefits are sometimes made available to those who exhaust these benefits, as has occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic.[15]

We previously reported that during the pandemic, states were allowed to ease certain Unemployment Insurance program requirements to support unemployed workers. This also included the creation of temporary Unemployment Insurance programs that expanded eligibility and enhanced Unemployment Insurance benefits (see text box).

|

Types of Pandemic-Era Unemployment Insurance The CARES Act created three federally funded temporary Unemployment Insurance programs that expanded benefit eligibility and enhanced benefit amounts. These programs were amended by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, and the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. · Pandemic Unemployment Assistance authorized Unemployment Insurance benefits for individuals not otherwise eligible for Unemployment Insurance benefits, such as self-employed and certain gig-economy workers who were unable to work due to specified COVID-19-related reasons. · Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation generally authorized an additional weekly benefit for individuals who were eligible for weekly benefits under the regular Unemployment Insurance programs or the temporary CARES Act Unemployment Insurance programs. Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation generally authorized additional weeks of Unemployment Insurance benefits for those who had exhausted their regular Unemployment Insurance benefits. In addition, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, created the Mixed Earner Unemployment Compensation program, which was extended by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. · Mixed Earner Unemployment Compensation program, which was voluntary for states, authorized an additional weekly benefit for certain Unemployment Insurance claimants who received at least $5,000 of self-employment income in the most recent tax year prior to their application for Unemployment Insurance benefits. These pandemic-era Unemployment Insurance programs expired on September 6, 2021. Some states opted to terminate their Pandemic-Era Unemployment Insurance programs before the authorized dates. As we noted in our July 2024 report (GAO‑24‑107471), according to the Department of Labor, 20 states terminated participation in the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program between mid-June and late July 2021. For more information, see GAO‑22‑104438, GAO‑22‑104251, GAO‑22‑105162, and GAO‑24‑107471. |

Source: Department of Labor. | GAO‑25‑106962

Older Workers’ Employment Rebounded in the Wake of the Pandemic, but Differences Between Demographic Groups Persisted

Across demographic groups, labor market outcomes for older workers aged 55 and older generally remained resilient in the wake of the pandemic, with older workers’ employment outcomes returning to pre-pandemic levels after an initial spike in unemployment at the start of the pandemic. Existing differences among demographic groups by educational attainment and race and ethnicity preceding the pandemic generally persisted during and after the pandemic.

Unemployment Rates Spiked Higher for Older Workers than Prime-Age Workers Early in the Pandemic, and Some Older Workers Left the Labor Force

Estimated unemployment rates for workers of all ages, including those 55 and over, rose dramatically at the start of the pandemic. Although workers aged 55 and older experienced more pronounced increases in unemployment at the start of the pandemic compared to prime-age workers (aged 25 to 54), their employment outcomes were resilient. The unemployment rate for older workers (aged 55 to 64) increased from an estimated 2.2 percent in April 2019 to a peak of 12.6 percent in April 2020, and then decreased to 4.9 percent by April 2021, according to our analysis of Current Population Survey (CPS) monthly data (see fig. 1).[16] By April 2023, the unemployment rate for the oldest workers (aged 55 to 64) was an estimated 2.2 percent, rebounding to its pre-pandemic level.[17]

Notes: From January 2017 through March 2020 and from October 2020 to December 2023, these monthly estimates have a maximum margin of error at the 95 percent level of +/-0.3 percentage points for those aged 25 to 54, +/-0.6 percentage points for those aged 55 to 64, and +/-0.9 percent for those aged 65 and older. From April 2020 through September 2020, these monthly estimates have a maximum margin of error at the 95 percent level of +/-0.5 percentage points for those aged 25 to 54, +/-0.8 percentage points for those aged 55 to 64, and +/-1.4 percentage points for those aged 65 and older. We used CPS microdata to produce our estimates, and we did not adjust for seasonality. Our estimates may differ slightly from official Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates. See appendix II for estimates of the number of employed and associated margin of error, by annual quarter, from 2017 to September 2023.

Our analysis found that older workers faced different circumstances in unemployment. Before, during, and after the pandemic, unemployed older workers aged 55 to 64 as well as unemployed oldest workers aged 65 and older were more likely than prime-age workers aged 25 to 54 to report that the reason for their unemployment was that they lost their job or had been laid off. In contrast, prime-age workers aged 25 to 54 were more likely than older workers to report that the reason for their unemployment was that their temporary job had ended or they were a job leaver.[18]

The labor force participation rate is another way to assess the overall health of the economy.[19] We found that the labor force participation rate for all groups of workers we examined followed a relatively similar trajectory during the period from January 2017 through December 2023, with the exception of the participation rate for prime-age workers aged 25 to 54, who experienced a steeper downturn compared to older workers aged 55 to 64 or oldest workers 65 and older at the onset of the pandemic.[20] This is different from the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, when there was a greater contrast between how older workers fared compared to younger workers. As we reported in 2012, the labor force participation rate of workers aged 55 and older had increased throughout the 2007–2009 recession, whereas the labor force participation rates for younger workers stayed the same or decreased during this period.[21]

There are a variety of factors that could have influenced the employment recovery of older workers during the pandemic, including reentry into the workforce, retirement, and underutilization.

Unemployed re-entrants. Following the initial wave of departures from the workforce at the onset of the pandemic, a greater proportion of individuals aged 65 and older (approximately 39 percent) in the fourth quarter of 2022 reported that they were job re-entrants—meaning they were job seekers who had worked before, but not immediately prior to their job search—than those aged 55 to 64 (approximately 25 percent) or those aged 25 to 54 (approximately 30 percent), according to our analysis of CPS data.[22]

Exiting and retirement. Older workers exiting the labor force or retiring in the wake of the pandemic could have contributed to what appears to be a strong recovery, according to two experts we interviewed.[23] A December 2021 survey of individuals aged 50 and older who left their job reported that 21 percent of respondents said they had retired earlier than planned because of the pandemic.[24] In addition, a study of workers aged 55 to 79 and transitioning out of the workforce pre- and post-pandemic found that the likelihood of them leaving the labor force rose by 6.7 percentage points—a rate that was 43 percent greater than the pre-pandemic period.[25]

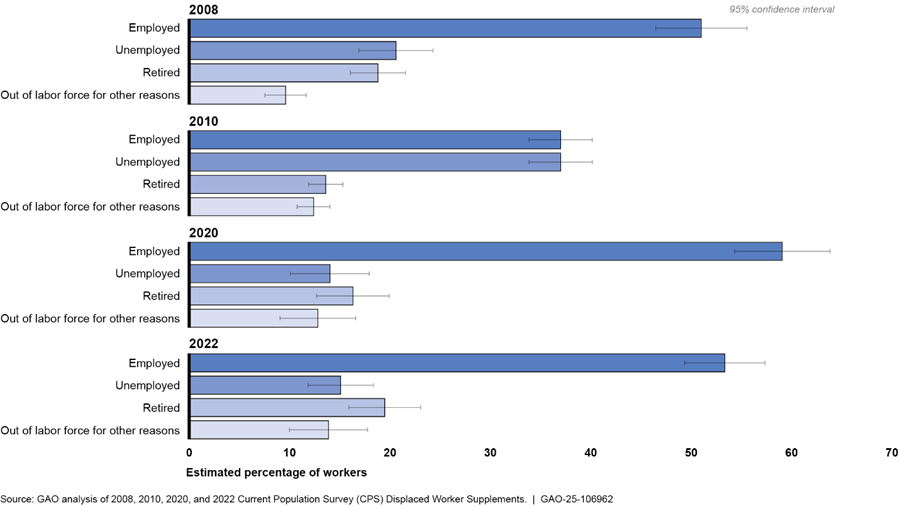

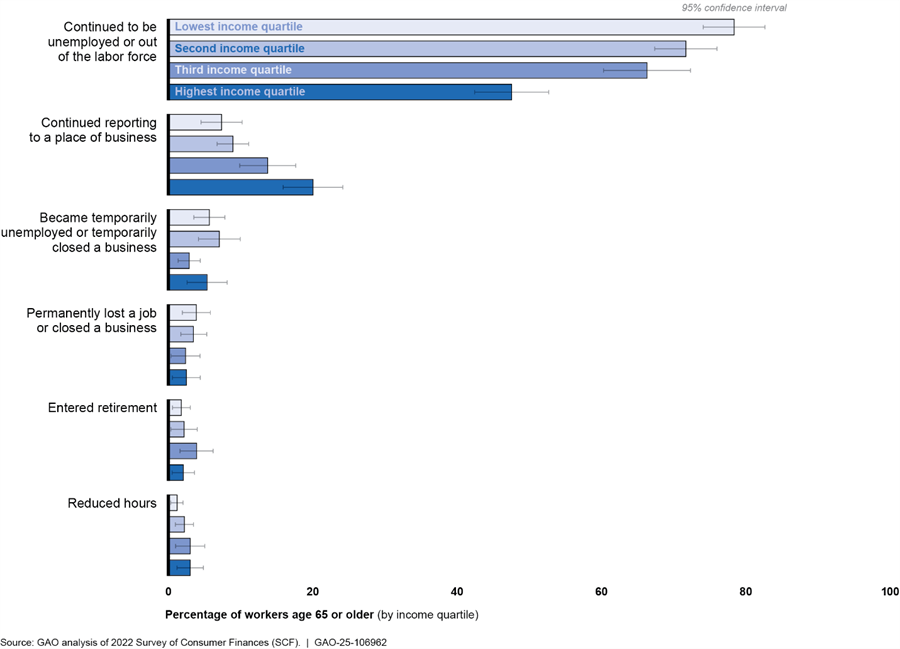

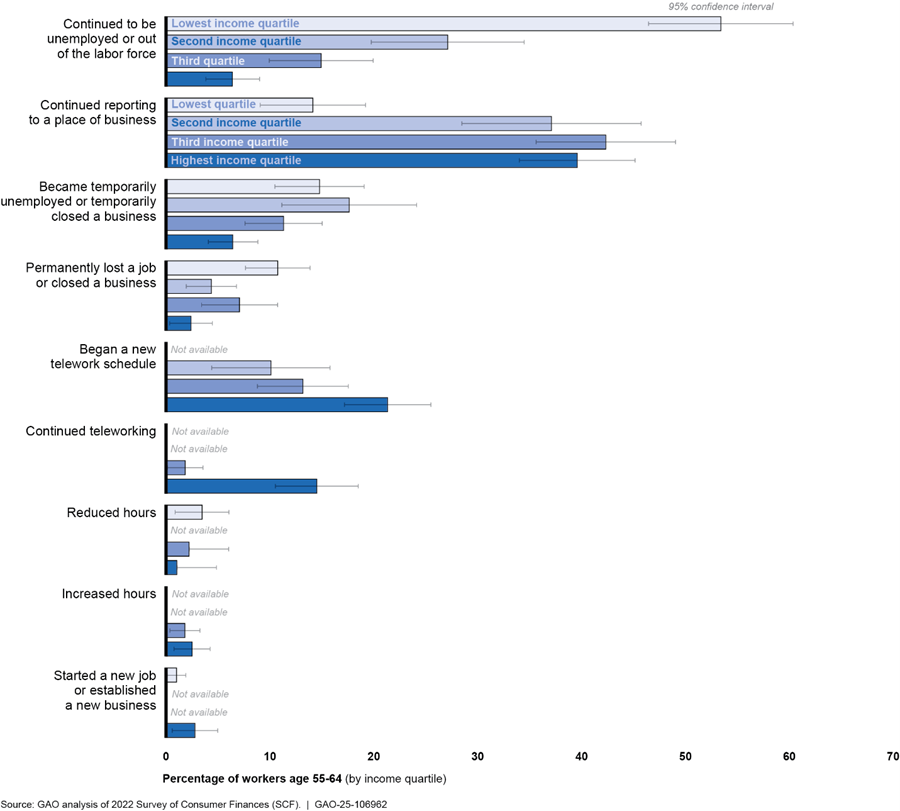

Our analysis of Displaced Worker Supplements found that a higher percentage of workers aged 55 and older who were displaced in the 3 years prior to January 2022 generally reported that they were retired versus the percentage of those displaced in 3 years prior to the January 2010 supplement.[26] The results are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Labor Force Status of Workers Aged 55 and Older Who Lost Their Jobs in the Past 3 Years due to Layoffs or Plant Closures, as of January 2008, 2010, 2020, and 2022

Notes: This figure shows the labor force status in January 2008 for workers displaced between January 2005 and December 2007, in January 2010 for workers displaced between January 2007 and December 2009, in January 2020 for workers displaced between January 2017 and December 2019, and in January 2022 for workers displaced between January 2019 and December 2021. Displaced workers are defined as wage and salary workers 20 years of age and older who lost or left jobs because their plant or company closed or moved, there was insufficient work for them to do, or their position or shift was eliminated. Due to CPS data limitations, our definition of “retired” includes only people who are no longer in the labor force. Therefore, this definition does not include retired persons who have part-time work. We note that the survey design results an overlap in reporting the time period in which workers may have been displaced. As such, the years 2007 and 2019 are represented twice in the figure. However, each wave of the Displaced Worker Supplement consists of an independent sample of distinct individuals.

Three experts told us in interviews that the continued aging of the U.S. baby boom generation—those born between 1946 and 1964—coincided with the increase in retirements during and after the onset of the pandemic. An analysis published in March 2023 found that “nearly all” of the decrease in the U.S. labor force participation rate since February 2020 could be explained by the aging of the U.S. population, which resulted in an increase in retirements during the period.[27]

Underutilization. An alternative measure, underutilization, shows that the number of underutilized older workers also increased substantially during the pandemic then returned to pre-pandemic levels around the third quarter of 2022.[28] An estimated 1.8 million older workers aged 55 to 64 and 800,000 oldest workers aged 65 and older were underutilized in the second quarter 2020, numbers that dropped to 1.0 million and 400,000, respectively, by the second quarter of 2021, according to our analysis of CPS data.[29] We found that the estimated number of older workers employed part-time for economic reasons was substantially larger than the number of marginally attached—including discouraged and other people marginally attached to the labor force—older workers throughout the time period.[30]

Nonetheless, the financial and emotional burdens of unemployment remain harsh for older workers, one expert told us. Workers aged 55 and older who lost their job in recent years were less likely to be reemployed and were more likely to earn less at their next job than younger workers, according to our analysis. Our analysis of Displaced Worker Supplements found that 41 percent of workers aged 55 and older who were displaced in the 3 years prior to January 2022 had not worked for pay since their previously held job compared to 22 percent for those aged 25 to 54 displaced during the same period.[31]

In addition, a greater share of older workers aged 55 and older who were displaced from their jobs during this period but successfully regained employment by January 2022 had lower earnings at the subsequent job compared to younger workers. An estimated 74 percent of reemployed displaced older workers had lower earnings (an earnings replacement rate of less than 100 percent) compared to 58 percent of reemployed individuals aged 25 to 54.[32]

Differences in Labor Force Participation by Educational Attainment and Race and Ethnicity Generally Persisted During and After the Pandemic

Across demographic groups, labor market trends generally remained resilient in the wake of the pandemic. We found that differences across demographic groups of older workers (including for those with higher educational attainment) persisted during and after the pandemic. In some cases, we found increases or decreases within a demographic group over time. We found greater labor force participation for Asian workers and reduced participation for leisure and hospitality workers after the pandemic.

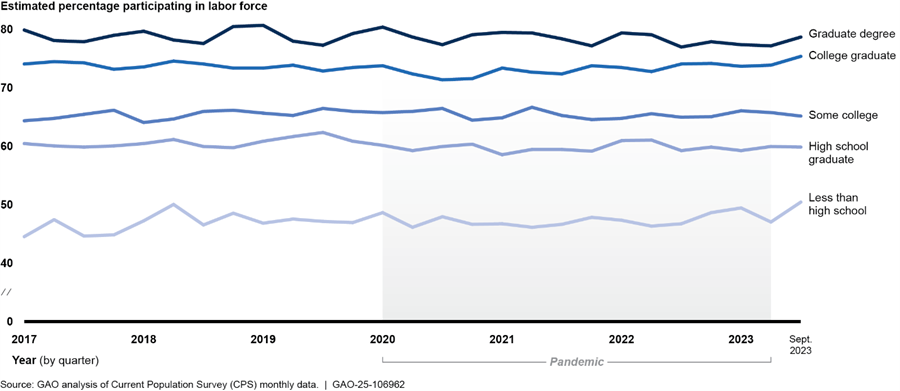

Educational attainment. For older workers aged 55 to 64, the overall proportion participating in the labor force remained relatively steady at an estimated 65 to 66 percent from January 2017 to September 2023.[33] However, as shown in figure 3, those with higher levels of educational attainment consistently participated at greater rates.

Figure 3: Labor Force Participation Rate of Workers Aged 55–64, by Educational Attainment, Quarterly 2017–2023

Notes: The maximum margins of error at the 95 percent confidence level are as follows: graduate degree, +/-1.9 percentage points; college graduate, +/-1.6 percentage points; some college, +/-1.6 percentage points; high school graduate, +/-1.5 percentage points; and less than high school, +/-2.8 percentage points. We used CPS microdata to produce our estimates, and we did not adjust for seasonality.

Five experts we interviewed told us that older workers with higher levels of educational attainment were likely to have higher levels of savings and household wealth and greater flexibility in terms of choosing whether to stay in the labor force or retire. One expert told us that older workers with lower levels of educational attainment were more likely to have reduced savings and household wealth, physically demanding jobs, and the need to remain in the labor force.

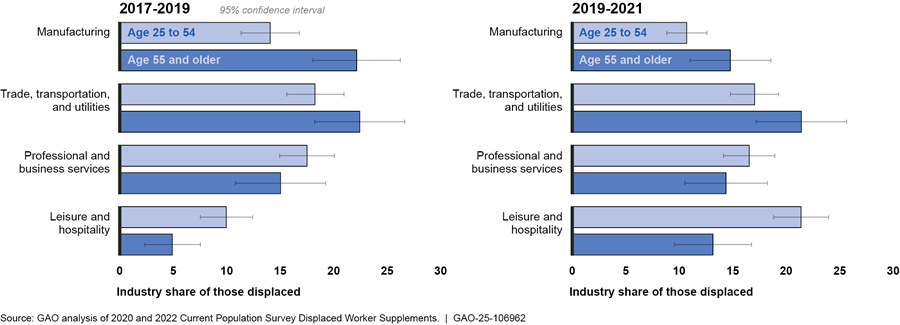

Industry. With respect to industries, our analysis shows that the largest share of displaced older workers aged 55 and older—about 20 percent—came from the trade, transportation, and utilities sector from 2019 to 2021.[34] However, the share of older worker displacements from the manufacturing sector moderately decreased between the 3-year periods of 2017 to 2019 and 2019 to 2021 from an estimated 22 percent to 14 percent. In addition, the share of displacements occurring in the leisure and hospitality industry moderately increased from an estimated 4 percent to 12 percent between those time periods.[35] See figure 4.

Figure 4: Industries of Workers Who Lost Their Jobs due to Plant Closures or Layoffs, by Time Period and Age Group

Notes: The Displaced Worker, Employee Tenure, and Occupational Mobility Supplement (Displaced Worker Supplement) is administered every 2 years as a supplement to the Current Population Survey. Displaced workers are wage and salary workers 20 years of age and older who lost or left jobs because their plant or company closed or moved, there was insufficient work for them to do, or their position or shift was abolished. For example, for the 2022 Displaced Worker Supplement, people are identified as displaced if they lost or left their job for one of the specified reasons between January 2019 and December 2021. We note that the survey design results in an overlap in the reporting time period in which workers may have been displaced. As such, those displaced in 2019 were included in the January 2020 and January 2022 issued Displaced Worker Supplements. However, each wave of the Displaced Worker Supplement consists of an independent sample of distinct individuals.

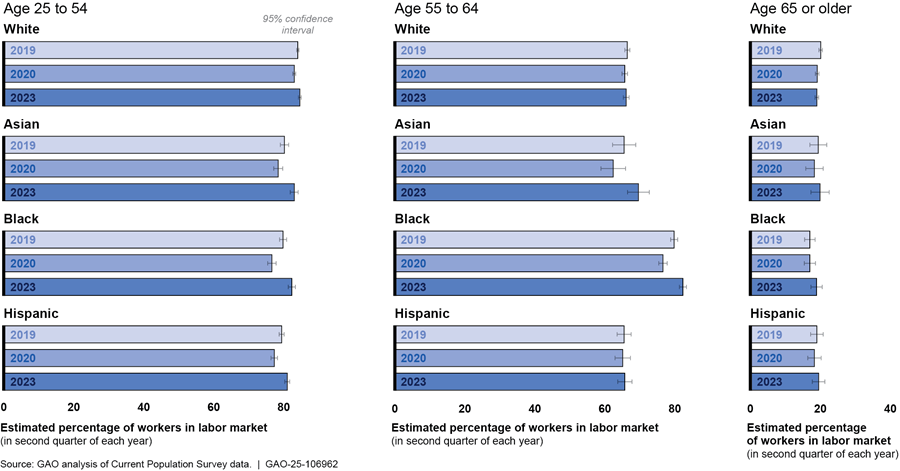

Race and ethnicity. The workforce participation of Asian individuals aged 55 to 64 increased slightly between March 2020 and March 2023, 3 years after the onset of the pandemic, while the workforce participation of White, Black, and Hispanic workers aged 55 to 64 and all race and ethnic groups aged 65 and older remained relatively steady, according to our estimates (see fig. 5).[36] See appendix II for detailed information on the estimated labor force participation rate by race and ethnic group by annual quarter.

Figure 5: Estimated Labor Force Participation Rate, by Race and Ethnicity and Age Group, Second Annual Quarter of Selected Years

Note: We used CPS microdata to produce our estimates, and we did not adjust for seasonality. We compare quarterly estimates from the second quarter of 2019 to provide pre-pandemic estimates; the second quarter of 2020 to account for the pandemic onset; and the second quarter of 2023, which is the quarterly estimate closest to the review period end of September 2023 that maintains second quarter seasonality.

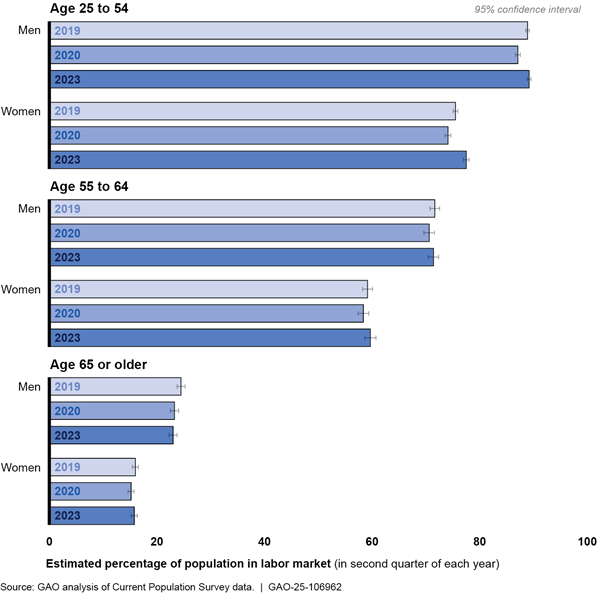

Gender. Men participated in the workforce at higher rates than women across all age groups from January 2017 to September 2023, as shown in figure 6. We did not observe any differences in labor force participation rates for older men or women during the pandemic.[37] See appendix II for detailed information on the estimated labor force participation rate by gender by annual quarter.

Figure 6: Estimated Labor Force Participation Rate, by Gender and Age Group, Second Annual Quarter of Selected Years

Note: We used CPS microdata to produce our estimates, and we did not adjust for seasonality. We compare quarterly estimates from the second quarter of 2019 to provide pre-pandemic estimates; the second quarter of 2020 to account for the pandemic onset; and the second quarter of 2023, which is the quarterly estimate closest to the review period end of September 2023 that maintains second quarter seasonality.

After Initial Decline, Higher Rate of Workers Near Full Retirement Age Claimed Social Security, and Demographic Differences in Older Workers’ Finances Persisted

Early in the pandemic, retirement benefit claims for older workers nearing full retirement age declined. However, rates of retirement benefit claiming for those near full retirement age increased 6 months after the President declared a national emergency. Older workers’ finances held steady during the pandemic, with their estimated median account balances holding steady between 2019 and 2022. Finally, differences in asset holdings among economic and demographic groups persisted during and after the pandemic. Specifically, we found that among other things, the median total value of assets was consistently higher for higher-income, more highly educated, Asian, White, and male-led older households during the periods reviewed.

During Early Pandemic, Retirement Claiming Rates Decreased Slightly for Most Older Workers, but After 6 Months, Claims Increased for Those Near Full Retirement Age

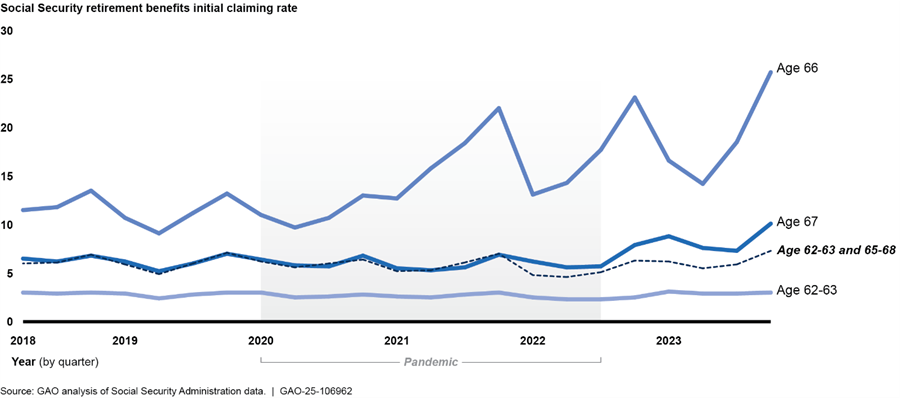

Our analysis of Social Security administrative data indicates that during the pandemic, the rate of fully insured workers who were near the full retirement age and claiming retirement benefits decreased during the first 3 months of the pandemic. In late 2020, 6 months after the President declared a national emergency, the rate of claiming around full retirement age increased, eventually exceeding pre-pandemic levels.[38]

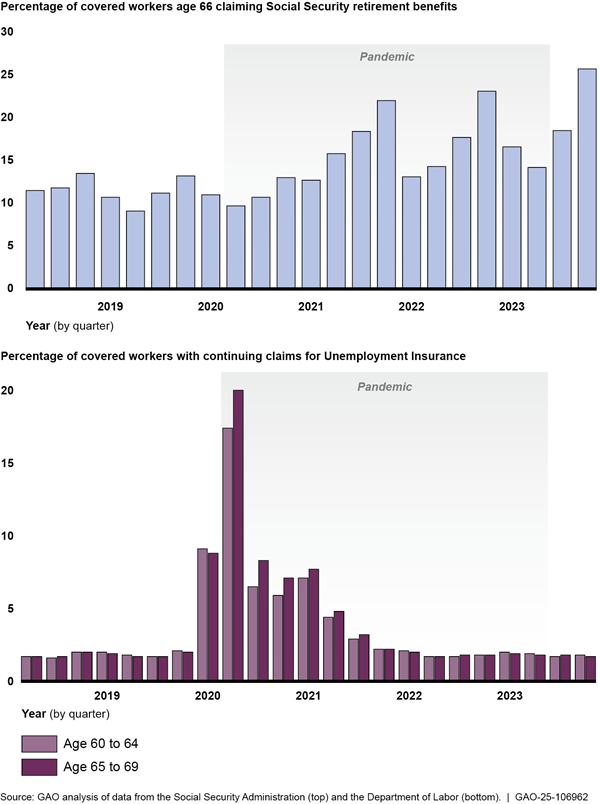

Our analysis of Social Security retirement benefit claiming rates from 2018 to 2023 found that rates decreased during the initial months of the pandemic for most ages. However, claiming rates increased for those near full retirement age in the fourth quarter of 2020, which corresponded with the time when some individuals’ regular unemployment insurance benefits would have been expected to expire.[39] More specifically, as shown in figure 7, at the beginning of the pandemic, claiming rates for retirement benefits slowed for those aged 66 during the initial months of the pandemic, while claiming rates did not generally vary for the 62 to 63 age group.

Figure 7: Percentage of Eligible Fully Insured Workers Claiming Social Security Benefits, by Age, Quarterly 2018–2023

Notes: The quarterly claiming rate is ratio of the number of workers filing a claim for Social Security benefits to the estimated number of eligible workers in the same age group and in the same quarter. Rates are based on the age at which insured workers file their initial claim. As such, “advance filers”—individuals who may file up to 4 months in advance of their requested month and year to begin claiming retirement benefits—may be included at an earlier age than when they begin to receive benefits. We exclude age 64 rates because they would include Medicare-only claimants, who are included in the count of initial claim filings and are not filing for a retirement benefit. According to Social Security Administration officials, these claimants register for Medicare elsewhere, and that information is then sent to the Social Security Administration so it may prepare to issue retirement benefits to that individual, should that individual later choose to start claiming retirement benefits.

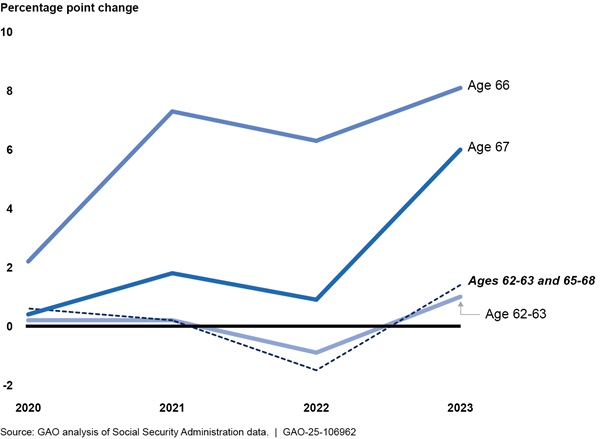

However, about 6 months after the pandemic national emergency was declared, the Social Security retirement benefit claiming rates started increasing for those near or at the full retirement age (age 66) during the fourth quarter of 2020, as shown in figure 7.[40] The annual rates for initial retirement benefit claims for the age 66 group—those who are at or near full retirement age—remained high during the pandemic, while the claiming rates for those younger than the full retirement age (e.g., ages 62 to 63) generally fell during the first 3 years of the pandemic then increased slightly in 2023.[41] We found that the rate at which workers aged 66 filed for Social Security retirement benefits increased more than 7 percentage points from 2019 to 2021, as shown in figure 8.

Figure 8: Change in the Annual Claiming Rate for Social Security Retirement Benefits, by Age, Since 2019

Notes: Rates are based on the age at which insured workers file their initial claim. As such, “advance filers”—individuals who may file up to 4 months in advance of their requested month and year to begin claiming retirement benefits—may be included at an earlier age than when they begin to receive benefits. We exclude age 64 rates because they would include Medicare-only claimants, who are included in the count of initial claim filings and are not filing for a retirement benefit. According to Social Security Administration officials, these claimants register for Medicare elsewhere, and that information is then sent to the Social Security Administration so it may prepare to issue retirement benefits to that individual, should that individual later choose to start claiming retirement benefits.

A comparison of the trends in figure 9 suggests that for workers near the full retirement age, the rate of initial claims for Social Security retirement benefits began increasing 6 months after the national emergency was declared.[42] Five experts we interviewed told us that because the value of the pandemic-era unemployment benefits may have been generous, some individuals may have delayed retirement until after their unemployment benefits ran out. One expert stated that because the pandemic-era unemployment insurance benefits were generous for some, there was less incentive to work or claim Social Security retirement benefits.[43] See figure 9.

Figure 9: Percentage of Eligible Workers Near Full Retirement Age Claiming Social Security Retirement Benefits and Distribution of Continued Claims for Regular Unemployment Insurance, Quarterly 2018–2023

Notes: The quarterly claiming rate is the ratio of the number of workers filing a claim for Social Security benefits to the estimated number of eligible workers in the same age group and in the same quarter. We identified the number of Unemployment Insurance claimants by analyzing data from the Department of Labor’s (DOL) Characteristics of the Unemployed Insured (ETA 203) publication, which provides information on Unemployment Insurance continued claims. Continued claims represent the number of people who have already filed an initial claim for regular, non-pandemic-related Unemployment Insurance and who have experienced a week of unemployment then filed a continued claim to claim benefits for that week of unemployment. Because of DOL data limitations, we were unable to identify the number of or trend information for claimants by age for pandemic-related Unemployment Insurance benefits.

Figure 9 shows that the rate for older workers’ continued claims for Unemployment Insurance surged at the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020.[44] Their continued claiming rates dropped to pre-pandemic levels around the time that standard Unemployment Insurance would be expected to terminate but for the pandemic-era Unemployment Insurance programs. Moreover, some individuals may have chosen or needed to continue working while receiving Social Security retirement benefits.

In addition, as we previously noted, several experts told us that the continued aging of the U.S. baby boom generation—those born between 1946 and 1964—coincided with the increase in retirements during and after the onset of the pandemic. Social Security Administration Office of the Chief Actuary officials said that since the mid-1990s, there has been a gradual shift from claimants tending to retire at ages 62 or 63 to instead retiring at ages 66 or 67. These officials also told us that there is a concentration of people who want to start their retirement benefits at the full retirement age so they can receive full retirement benefits. Accordingly, there has been a reduction in the number of individuals claiming at ages before full retirement age.

In addition to Social Security retirement benefits, the Social Security Administration provides Disability Insurance benefits to those with a sufficient work history who are unable to work due to a long-term disability. We analyzed administrative data from January 2018 to December 2023 regarding Disability Insurance claims for four age groups of individuals and found that the claiming rate for Disability Insurance benefits declined for all of these age groups at the beginning of the pandemic.[45] Except for the age 65 to 66 group, the Disability Insurance claiming rates generally remained level or continued to decline until 2023 when they increased relative to their 2022 level. The claiming rate for individuals aged 65 to 66 remained approximately the same through 2023.

Estimated Percentage of Older Households with Retirement Accounts and Median Account Balances Held Steady Between 2019 and 2022

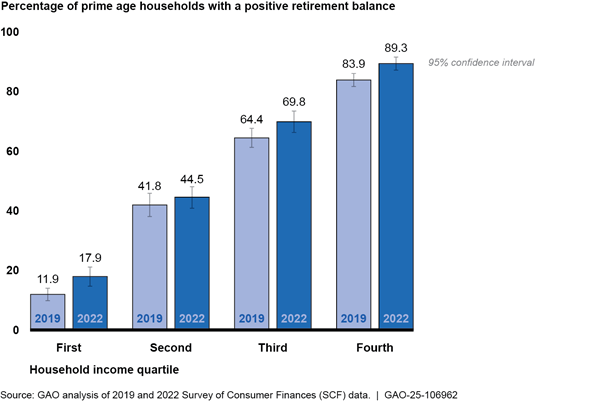

Overall, older households’ personal finances remained resilient during the pandemic. A variety of indicators suggests that older workers’ retirement savings generally held steady during the pandemic, including the percentage of households aged 55 or over with retirement accounts, the value of those accounts, and the extent to which such households took out hardship withdrawals from those accounts.[46]

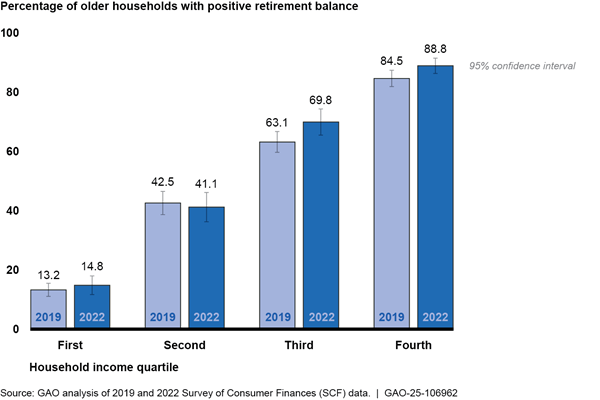

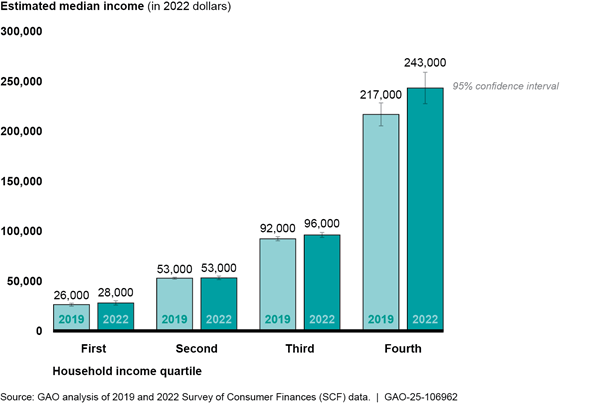

Retirement account prevalence. According to our analysis of the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) data, the percentage of older households (aged 55 and older) from higher income quartiles had consistently higher account prevalence rates in both 2019 and 2022. However, we did not observe any statistically significant increases or decreases for any income quartile from 2019 to 2022.[47] See figure 10.[48]

Figure 10: Estimated Percentage of Older Households (Aged 55 and Older) with a Retirement Account by Income Quartile, 2019 and 2022

Several experts told us that median savings rates and retirement savings have been generally increasing for older account holders since 2019. Also, two experts we interviewed told us they found that automatic enrollment has helped workers save more for retirement. A recent statutory provision requiring new workplace retirement plans to automatically enroll eligible employees may continue this trend.[49] In addition, research by Vanguard, one of the largest retirement record keepers, has also found that the overall participation rate of older workers was higher for employers that had adopted automatic enrollment. Vanguard also found that median retirement savings were higher for older workers in retirement plans with automatic enrollment than those with voluntary enrollment.[50]

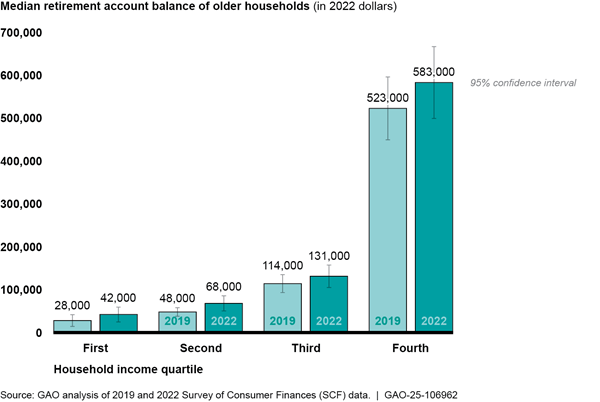

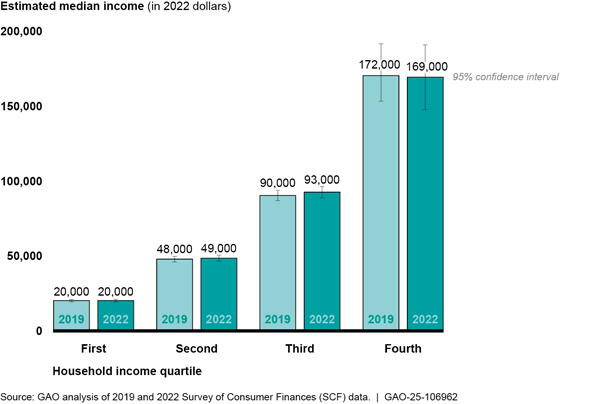

Account balances. According to our analysis of SCF data, among older households who had a positive retirement account balance, the estimated median balances in those accounts held steady between 2019 and 2022, as shown in Figure 11.[51]

Figure 11: Estimated Median Retirement Account Balance of Older Households (Aged 55 and Older) by Income Quartile, 2019 and 2022

However, two large record keepers reported balance increases during our study’s review period, from 2017 to 2024.[52]

In a 2024 study, researchers found that the risk of households aged 50 to 59 being unable to maintain their pre-retirement standard of living declined between 2019 and 2022 due to rising asset values (e.g., in housing, retirement plan savings, and investment accounts), according to their analysis of SCF data.[53] Similarly, several experts we interviewed told us that the rise in median total value of assets held by older households from 2019 to 2022 was driven in part by an increase in home values.

Hardship withdrawals. Two large record keepers found that hardship withdrawals remained relatively unchanged among older account holders aged 55 and older with retirement accounts between 2021 and 2022.[54] Vanguard found that 1.6 percent of its defined contribution account holders aged 55 to 64 took a hardship withdrawal in 2022 compared to 1.2 percent of account holders in that age group in 2021. For the oldest account holders aged 65 and older, only 0.2 percent took a hardship withdrawal in 2022 compared to 0.1 percent in 2021. Similarly, Fidelity reported that among its retirement account holders aged 55 to 59 years old, 3.8 percent took out hardship withdrawal distributions in 2022 compared to 3.0 percent in 2021.

Differences in Asset Holdings Among Economic and Demographic Groups Persisted During and After the Pandemic

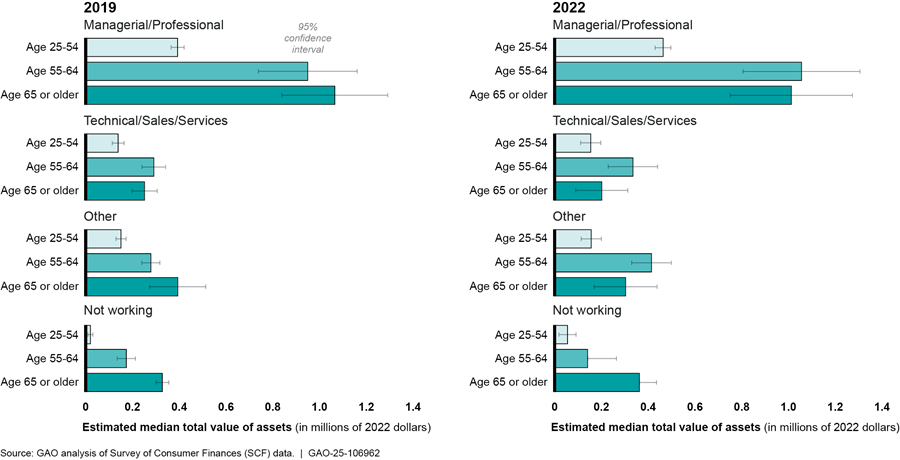

We identified differences among demographic groups of older workers using SCF data. We found that the median total value of assets was generally consistently higher for higher-income, more highly educated, Asian and White, and male-led older households during the periods reviewed.[55]

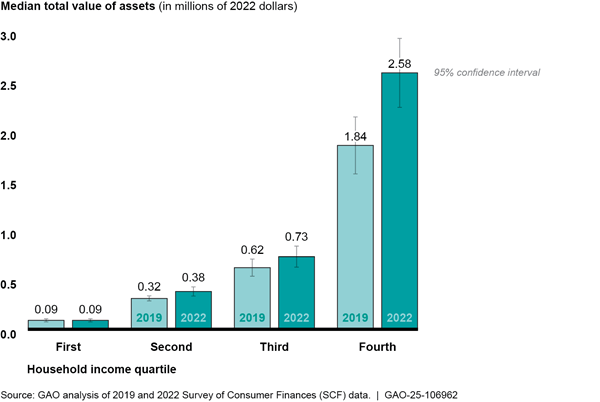

Income level. Among the oldest households (those aged 65 and older), those in the highest income quartile were estimated to hold higher total assets compared to the other three income quartiles, as shown in figure 12.[56] The highest income quartile had an estimated $1,844,000 median total value of assets in 2019 and $2,584,000 in 2022.[57] However, the 2019 and 2022 estimates for the total value of assets held by households in the three lower income quartiles were not statistically different.

Figure 12: Estimated Median Total Value of Assets Held by Oldest Households (Aged 65 and Older) by Income Quartiles, 2019 and 2022

Note: When measuring the asset holdings of a household, we used the total value of assets held by the household that takes into account all financial and nonfinancial assets, including the total value of the household’s retirement account holdings.

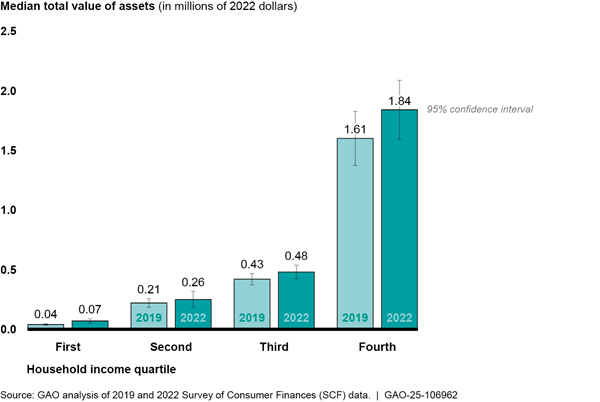

In addition, we found that among older households (aged 55 to 64), the highest income quartile held an estimated median value of assets of $1,609,000 in 2019 and $1,842,000 in 2022, as shown in figure 13.[58]

Figure 13: Estimated Median Total Value of Assets Held by Older Households (Aged 55–64) by Income Quartile, 2019 and 2022

Note: When measuring the asset holdings of a household, we used the total value of assets held by the household that takes into account all financial and nonfinancial assets, including the total value of the household’s retirement account holdings.

Several experts told us that the total value of assets increased for highest-income older workers because they had a larger initial allocation of assets, and they held more assets that appreciated at a higher rate in recent years, such as stocks. In comparison, these experts said, lower-income households usually have fewer assets, and their assets generally generate lower returns; in particular, a larger share of lower-income households’ assets are held in cash.

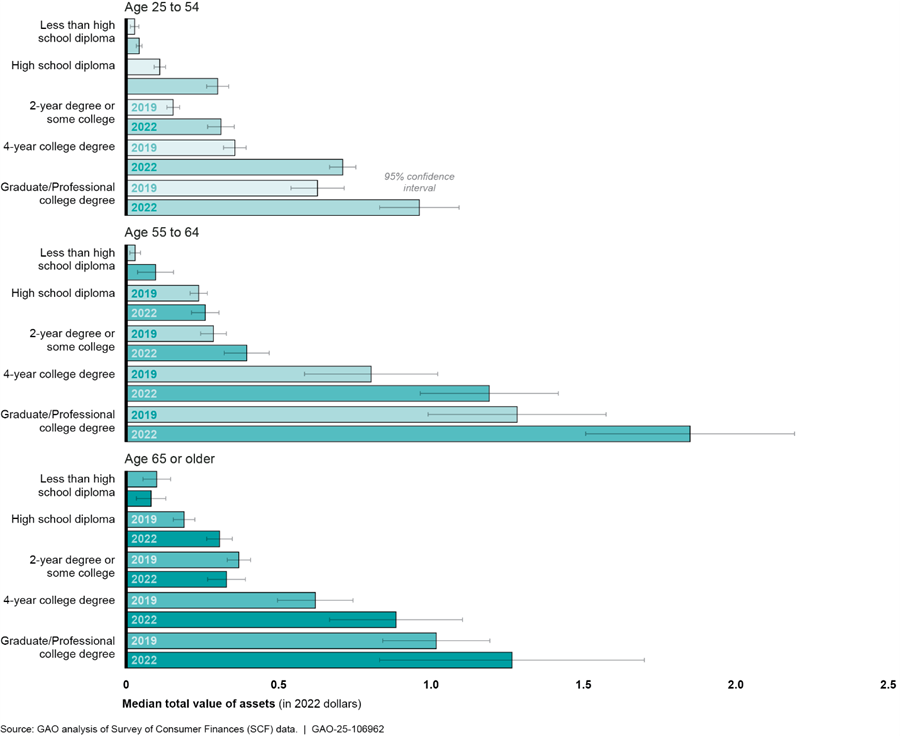

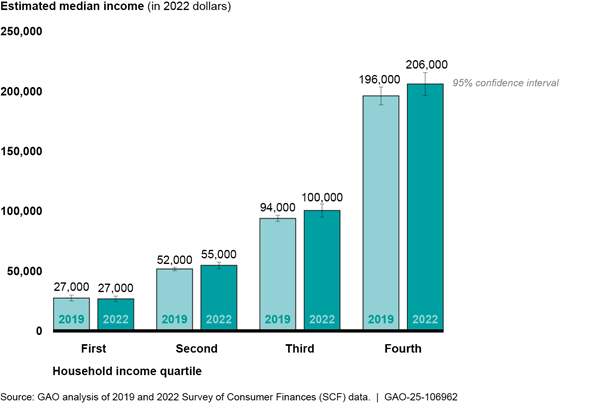

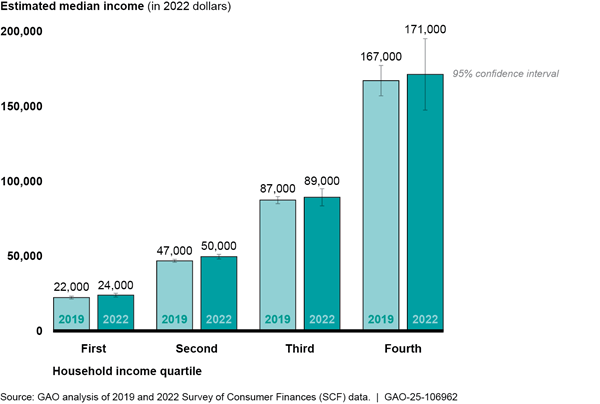

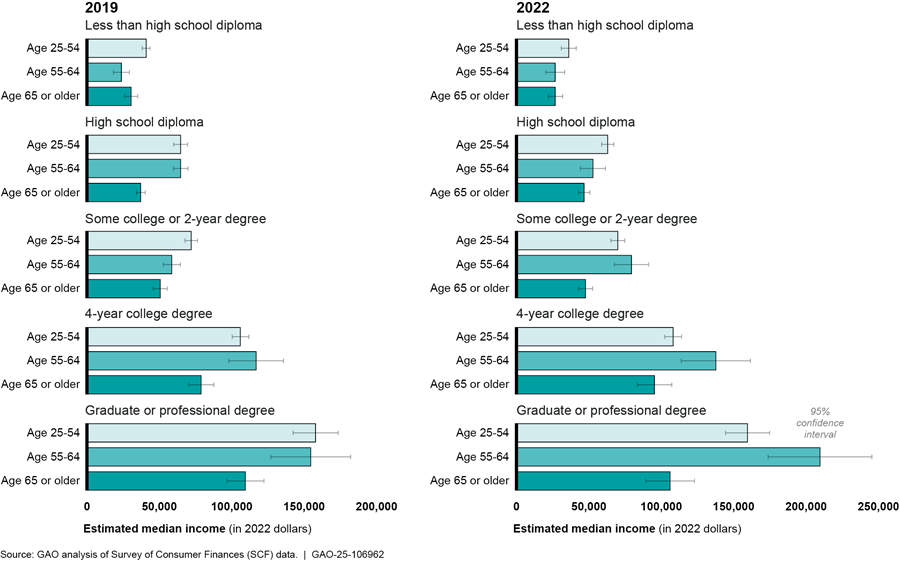

Educational attainment. We found that older households (aged 55 to 64) with the highest educational attainment (i.e., a graduate or professional degree) were estimated to have the highest median incomes and median total assets across all age groups, as shown in Figure 14.[59]

Figure 14: Estimated Median Total Value of Assets Held by Age Group and Educational Attainment, 2019 and 2022

Notes: For the purposes of this report, we used the head of household’s age and educational attainment as the household’s age and educational attainment. When measuring the asset holdings of a household, we used the total value of assets held by the household that takes into account all financial and nonfinancial assets, including the total value of the household’s retirement account holdings.

Several experts told us that highly educated older workers are more likely to have higher incomes, have access to and participate in retirement accounts, and acquire additional assets. They noted that this may not be the case for employees with lower levels of education who may have lower income levels and less ability to save for retirement, and we may see differences in assets held based on educational attainment. Several experts also suggested those who are aged 65 and older and are still in the labor force are mainly working in jobs that require higher educational attainment.

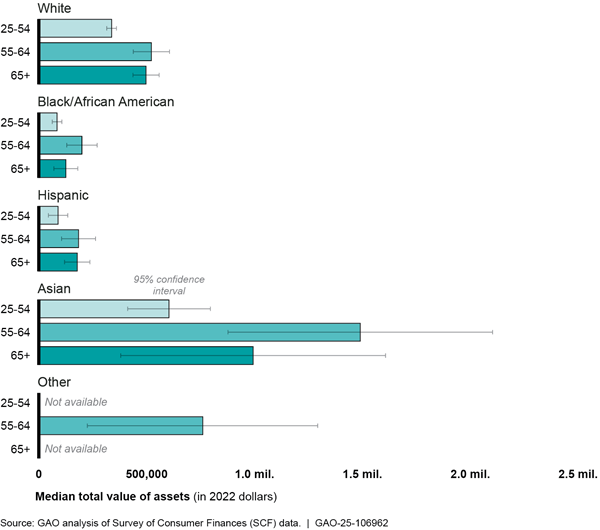

Race. Our analysis identified differences across racial groups in the assets held by both older households (aged 55 to 64) and oldest households (aged 65 and older) in 2022.[60] Among all racial groups that year, Asian households held the highest estimated median value of total assets across all age groups, as shown in figure 15.[61]

Figure 15: Estimated Median Total Value of Assets Held by Household by Age Group and Race and Ethnicity, 2022

Notes: We are not reporting estimates reported as “not available” because they are statistically indistinguishable from 0 due to high sampling error. When measuring the asset holdings of a household, we used the total value of assets held by the household that takes into account all financial and nonfinancial assets, including the total value of the household’s retirement account holdings. The SCF’s Other category includes Alaska Native American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, other races, and all respondents reporting more than one racial identification. In 2019, Asians were listed under the Other race category in the SCF.

In addition, we found that older Black/African American and Latino households aged 55 and older held less in retirement savings compared to older White households across all age groups in both 2019 and 2022, according to our analysis of SCF data.

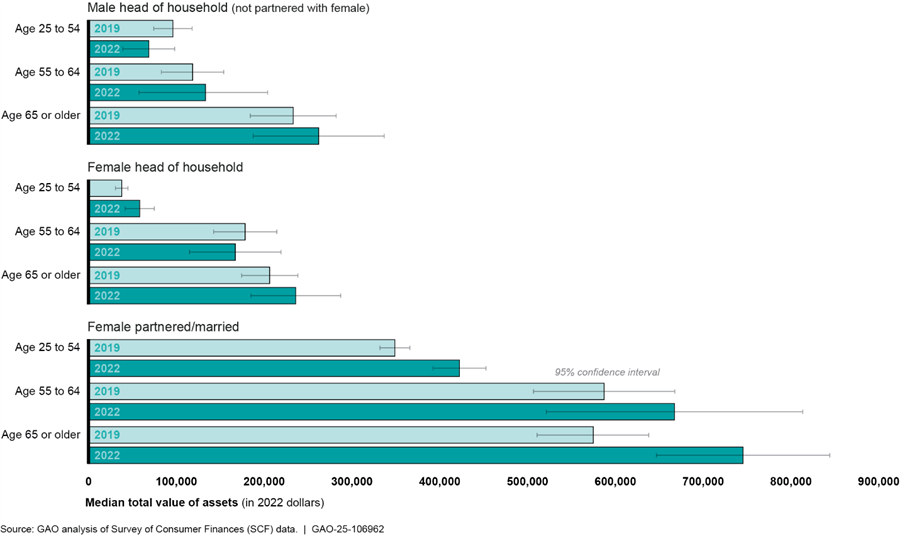

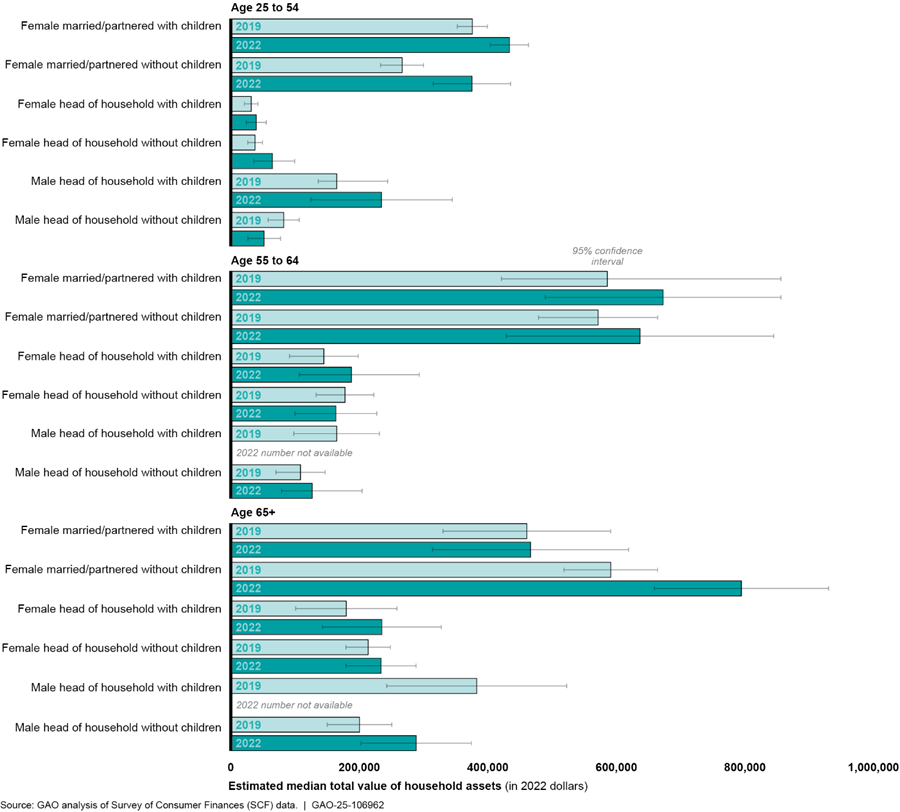

Gender. We observed differences in the value of assets by household composition across all age groups and genders, as shown in figure 16.[62] More specifically, we looked at the total value of assets held by three groups:

· female head of household—this includes single women and women with same-sex spouses or partners,

· households in which a woman is married or partnered to a male head of household, and

· male head of household—this includes single men and men with same-sex spouses or partners.

Figure 16: Estimated Median Total Value of Assets Held by Households by Gender and Age Group, 2019 and 2022

Notes: We estimated the total value of assets held by gender and age of the head of household. The SCF defines gender as male and female. For male heads of households (not partnered with females), this includes men that are single and married/partnered in same-sex couples. For female heads of households, this includes women that are single and married/partnered in same-sex couples. When measuring the asset holdings of a household, we used the total value of assets held by the household that takes into account all financial and nonfinancial assets, including the total value of their retirement account holdings.

Experts Favored Options to Boost Older Workers’ Employability but Cited Some Concerns

To understand more about how to improve employment outcomes for discouraged or unemployed older workers, we sent a written questionnaire to 32 experts on this topic. We asked the experts to rank the policies on a range of effectiveness and identify any specific limitations of each policy.[63]

Options Generally Aimed at Boosting Older Workers’ Employability Favored Most Often

Experts most often favored policy options that could most effectively boost older workers’ employability.[64] Of the 25 responses we received, experts ranked five of the 30 policy options as highly or moderately effective at enhancing employment outcomes for older workers.[65] The most favored policy option was a proposal that Congress remove the requirement that Medicare generally be the secondary payer for workers 65 and older who are covered by an employer health plan.[66]

Table 1 lists the five policy options for improving older workers’ employment outcomes that were ranked as highly or moderately effective by 12 or more experts, the reasons they cited for each policy option’s potential effectiveness, and the potential limitations of each policy option they identified. In addition, several experts who provided comments in our written questionnaire cautioned that a policy option’s effectiveness may be limited to the extent that it does not address other underlying challenges faced by unemployed older workers, such as age- or disability-related discrimination. Further, we previously reported that the effectiveness of certain policy options could be limited if an older worker’s unemployment is caused by structural rather than cyclical issues.[67] GAO did not develop or endorse any of these policy options.

Table 1: Policy Options to Improve Employment Outcomes for Older Workers Ranked as Highly or Moderately Effective by Selected Experts, and Selected Potential Limitations

|

Policy description |

Selected reason(s) experts supported policy |

Selected potential limitations identified by experts |

|

Policies to encourage employers to hire and/or retain older workers |

||

|

Congress removes the requirement that Medicare generally be the secondary payer for workers 65+ who are covered by an employer health plan.a |

Health insurance and other health-related costs are a major expense for employers, who can perceive cost as a disadvantage of hiring older adults because they may need expensive health care. Making Medicare the primary payer could alleviate the cost burden to employers offering health care coverage, which could increase demand for workers who are 65 and older. |

Workers aged 55–64 who are ineligible for Medicare could still face potential discrimination from employers who may avoid hiring them due to the perception that their health care costs more. This policy would also not specifically assist workers who do not have employer-based health insurance, including low-wage earners, and part-time workers, among other groups of workers. This policy could increase Medicare costs, and it is unclear to what extent most policymakers and taxpayers would be willing to support such increases. |

|

Reduce the cost of employing older workers by allowing employers to opt out of paying Social Security payroll tax once a worker has accumulated 35 years of covered earnings. |

This policy could reduce the employer’s cost of

hiring and employing older workers, and this could lead employers to hire

older workers more often. |

Without changes in other policies, this policy would not likely help those with weak labor force attachment, such as those who experience frequent unemployment spells or may not have accumulated 35 years of work experience or both. This could potentially reduce future benefits for older workers who had already accumulated 35 years of work experience and wanted to continued working. |

|

Policies to reduce older workers’ barriers to finding employment |

||

|

Congress enacts a wage insurance program to temporarily compensate older Americans who accepted new full-time jobs that pay less than their previous jobs within 27 weeks of filling for Unemployment Insurance. |

This could help older workers as they transition to new employment, especially those working in states that have lower minimum wages. |

None provided. |

|

Policies for Department of Labor (DOL) initiatives that could enhance older workers’ employment |

||

|

DOL identifies legal, regulatory, logistical, or other barriers to the employment of older workers and reports on approaches for reducing those barriers and any associated regulatory changes. |

This could help DOL better understand the barriers to employment older workers are facing. This could lead to more federal policymakers’ attention on age barriers and increase their efforts to find solutions. |

There is a lack of expertise on potential age discrimination and related barriers. Except for DOL’s Senior Community Service Employment Program, there is little federal funding and dedicated programs or support for older workers. |

|

DOL develops new or improves existing job search assistance programs to support older Americans. |

Targeted support for older job seekers could help reduce the problem of long-term unemployment that disproportionally affects older job seekers, especially if offered early in their job search. Currently, there are few, if any, services that target older workers. |

This policy should be coupled with evaluation of existing or new federal programs. To implement them, there would need to be funding for the local workforce services programs to support staff training and likely hire additional staff. |

Source: GAO analysis of experts’ responses to GAO’s questionnaire. I GAO‑25‑106962

These policy options were selected as highly or moderately effective by 12 or more experts from a list of 30 policy options. We selected most of our policy options presented in our prior work (GAO‑12‑445) and from a September 2023 National Academy of Social Insurance panel report to identify policy options that experts proposed to enhance the employment outcomes of older workers. We also identified policy options through discussions with experts, who are active in researching the issue. GAO did not develop or endorse any of these policy options.

aIf an employer with fewer than 20 full- and/or part-time employees sponsors or contributes to a single-employer Group Health Plan, the Medicare Secondary Payer rules applicable to individuals entitled to Medicare on the basis of age do not apply to such individuals.

Experts Identified Four Common Themes Across Policy Options

When responding to the written questionnaire and in interviews, experts stated concerns in at least one of four key themes concerning how to improve employment for older workers.

Reducing cost burdens. Three experts told us in interviews that employers view older workers as more expensive to hire.[68] Some experts favored policy options that would lower the cost of hiring and employing older workers. For example, four experts said in written comments or in interviews that the policy option that allowed employers to opt out of paying Social Security payroll tax once a worker has accumulated 35 years of covered earnings could reduce the cost of employing older workers. However, six experts who provided written or oral comments cautioned that this policy option could substantially increase the federal government’s costs.

Providing health care coverage. Four experts we interviewed told us that health care is a key concern for employers because they often pay a large share of the company’s insurance premiums and may need to pay more to provide health care to older workers.[69] Four experts we interviewed also said the perception that older workers’ health care benefits cost more can lead some employers to consciously or subconsciously rule out hiring them, thus creating a barrier on the demand side. Seven experts told us in written comments or interviews that the policy option for Congress to remove the requirement that Medicare generally be the secondary payer for workers aged 65 and older who are covered by an employer health plan could reduce health care costs for employers and thus encourage them to hire and or retain older workers.[70] This could enhance employment outcomes of older workers. However, four experts who provided written comments said that this could increase Medicare’s program costs and may not help older workers who are not eligible for Medicare.[71]

Providing targeted support services for older job seekers. Three experts expressed their concerns in interviews that there are insufficient targeted support services for older job seekers. For example, one expert we interviewed told us that they found older job seekers are not getting the same treatment as younger workers in Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act programs or at American Job Centers.[72] Six experts also told us in their written comments or in interviews that more federal grant funding is needed for targeted services to support older job seekers, such as expanding eligibility or funding for the Senior Community Service Employment Program.[73] In addition, three experts told us in interviews that these federal efforts could help further support older workers, especially marginally attached workers who are historically overlooked by employers and may face additional barriers to employment. These marginally attached workers may include older workers who lack updated skills or older workers that cannot access certain jobs. Furthermore, three experts said in our written questionnaire that increasing supportive services that target older job seekers and workers could directly benefit older workers by enhancing their employment outcomes.

Providing age- and disability-related workplace accommodations and other flexibilities for older workers. Four experts said in written comments or in interviews that unemployment and low labor force participation among older workers are caused, in part, by employers’ failure to provide workplace accommodations to older workers with disabilities. Three experts that provided comments in our written questionnaire also told us that existing structural barriers—such as potential age and disability discrimination in the workplace—are a continued challenge for older workers and were not addressed in our list of policy options in the written questionnaire.

Various experts we spoke with discussed that workplace flexibilities had increased in recent years and supported increasing federal efforts to better support and understand this area of work in relation to older workers. Three experts said they supported expanding workplace flexibilities for older workers, such as independent contracting and gig work, in their comments provided to our written questionnaire or in interviews. Three experts told us in interviews that these types of workplace flexibilities can allow individuals to work when and how they want. This can be particularly appealing to some older workers who may have physical limitations that make it harder for them to serve in traditional full-time positions or who may prefer to have more flexibility over their time and daily schedules, these experts said. Two experts also told us in interviews that the increasing use of flexible work arrangements can encourage older workers to remain in or return to the workforce.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the Department of Labor, and the Social Security Administration for their review and comment. We received technical comments from the Department of Labor and the Social Security Administration, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Chair of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the Secretary of Labor, the Commissioner of the Social Security Administration, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at nguyentt@gao.gov.

Tranchau (Kris) T. Nguyen, Director

Education, Workforce, and Income Security

List of Committees

The Honorable Susan Collins

Chair

The Honorable Patty Murray

Vice Chair

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Crapo

Chairman

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Tom Cole

Chairman

The Honorable Rosa L. DeLauro

Ranking Member

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Mark E. Green, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Gerald E. Connolly

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jason Smith

Chairman

The Honorable Richard Neal

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

This report examines the following: (1) How did trends in older workers’ employment status vary from 2017 to 2023, and to what extent were there demographic differences among worker subpopulations? (2) How did older workers’ personal finances, including their Social Security benefit claiming rates change, if at all, during the pandemic? and (3) What policy options did experts identify as likely to enhance the employment outcomes of discouraged or unemployed older workers?

Analyzing Employment Trends in Older Workers

To identify trends in older workers’ employment status, including any demographic differences among worker subpopulations, we analyzed monthly data from 2017 through 2023 from the Current Population Survey (CPS) produced by the Department of Labor (DOL) Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).[74] We also analyzed data from CPS’s 2008, 2010, 2020, and 2022 Displaced Worker, Employee Tenure, and Occupational Mobility Supplements (Displaced Worker Supplement).

We selected CPS because it is nationally representative; contains large sample sizes, as well as demographic and industry information; and is the primary source of labor force statistics for the United States. The survey is based on a sample of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population in the United States. About 42,000 households are interviewed monthly based on area of residence to represent individual states and the country as a whole.[75] We used CPS monthly data, rather than its yearly Annual Social and Economic Supplement, because it allowed us to analyze discrete monthly effects of the pandemic that occurred from March 2020 to April 2023.

We also produced quarterly annual summary statistics to identify aggregate trends. To compare these trends across age groups, we separately analyzed the following age groupings: people aged 25 to 54, who are defined by BLS as the prime working-age population; people aged 55 to 64, who represent the older working population that is nearing full retirement age; and people aged 65 and older, who are more likely to be retired or retiring soon.

Similarly, we analyzed the 2008, 2010, 2020, and 2022 Displaced Worker Supplements to the Current Population Survey, because this supplement contains data on the employment and earnings status of displaced workers before and after their job losses.[76] The Displaced Worker Supplement identifies people as displaced if they lost or left their job because of a plant closure or layoff, there was insufficient work for them to do, or their position or shift was abolished during the 3 years prior to the January issuance of the biannual supplement.[77] Displaced workers are defined as those workers who have lost a job in the past 3 years; however, they may be unemployed, employed, or not in the labor market at the time of the survey.

For all of our estimates using CPS data, including the Displaced Worker Supplements, we estimated the standard errors and constructed the confidence intervals taking into account the survey’s dual-frame sample design in order to estimate the sampling variance for these estimates.[78] We used CPS microdata to produce our estimates, and we did not adjust for seasonality.

To assess the reliability of the 2017–2023 CPS monthly data, as well as the 2008, 2010, 2020, and 2022 Displaced Worker Supplements, we (1) reviewed relevant documentation, including GAO’s previous analyses of CPS monthly data and Displaced Worker Supplement data; (2) interviewed (through email exchanges) officials or researchers with expertise who use these data to answer technical questions and obtain their perspectives on any data discrepancies or errors we found; and (3) conducted electronic tests to identify missing data, outliers, and errors. To the extent possible, we compared our estimates with published reports using CPS data, such as BLS reports.

We recognize that there are certain limitations with the data and, accordingly, any estimates we produced using the data. As a mixed-panel dataset, CPS compares cross-sections of workers at different points in time—over a 16-month period, respondents are asked to complete the survey for 4 months, then are not surveyed for 8 months, and then are asked to complete the survey for another 4 months. Any time trends may be subject to composition bias unless additional methodologies are implemented to control for this (e.g., matching respondents over time). We determined that the data for the variables we used were sufficiently reliable to produce statistically reliable estimates—including those used to produce estimates regarding the trends in employment and unemployment, duration of unemployment and identify any differences in employment or employment characteristics, such as sector and industry employed—for demographic subpopulations of workers aged 25 to 54, 55 to 64, and 65 and older.

We compared our results with other expert studies and previous GAO work, especially our October 2011 and April 2012 reports.[79]

Analyzing How Older Workers’ Personal Finances Changed

To examine how older workers’ personal finances, including their Social Security benefit claiming rates, changed during the pandemic, we obtained and analyzed Social Security Administration (SSA) data, DOL Unemployment Insurance data, and the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) data; interviewed experts; and reviewed and analyzed other key information and studies regarding older workers’ personal finances before and after the pandemic.

SSA claiming rates. To identify trends in SSA claiming rates, we estimated claiming rates before and during the pandemic from 2018 to 2023. We then compared the claiming rates during the pandemic to the pre-pandemic rates. We also analyzed DOL Unemployment Insurance data for the same time period to help us understand any correspondence with SSA benefits claiming during the pandemic.

We obtained and analyzed individual SSA Old Age Insurance (retirement benefits) and Disability Insurance claimants’ biographic and demographic information (e.g., date of birth and zip code) from 2018 through 2023 from SSA’s Modernized Claims System. The Modernized Claims System is a non-public data repository with information for SSA retirement and Disability Insurance benefit claims.

We reviewed recent GAO work on SSA retirement, Disability Insurance, and Supplemental Security Income benefits. We conducted additional analyses of administrative data provided by SSA to GAO for a November 2022 report.[80] We obtained additional administrative data from SSA for retirement benefit and Disability Insurance benefit claims and used these data to analyze individual claiming behavior for retirement and Disability Insurance benefits.[81] In particular, we analyzed the data to determine the number of older workers claiming retirement and Disability Insurance benefits, by claimant age, on a quarterly basis from 2018 to 2023.[82]

We requested additional data regarding the estimated number of individuals fully insured for SSA retirement benefits and disability insured for Disability Insurance benefits, by claimant age, from 2018 through 2023 from SSA’s Office of the Chief Actuary.[83] These data, along with the number of claimants by age, allowed us to estimate the percentage of eligible workers claiming Social Security retirement or Disability Insurance benefits at various ages. We excluded retirement claiming rates at age 64 because they included many claims for Medicare benefits only (i.e., they did not include a claim for retirement income benefits). To identify any trends in how Social Security retirement benefit claiming rates might have corresponded with the termination of Unemployment Insurance benefits, we compared our analyses of Social Security retirement benefit claiming rates with information we obtained and analyzed from DOL’s Employment and Training Administration’s Characteristics of the Insured Unemployed reports from 2018 to 2023.[84]

With respect to Disability Insurance benefits, we analyzed administrative data from 2018 to 2023 that we obtained from SSA’s Modernized Claims System regarding individual claimants and analyzed for those claimants aged 55 to 59, 60 to 61, 62 to 64, and 65 to 66. We chose these age categories to isolate and better estimate the extent to which individuals nearing the full retirement age began claiming benefits compared to younger individuals.

To assess the reliability of SSA-supplied administrative data, we (1) reviewed relevant documentation, including GAO’s previous analyses of SSA Modernized Claims System data; (2) interviewed officials with expertise on these data to answer technical questions and obtained their perspectives on any data discrepancies or errors we found; and (3) conducted electronic tests to identify missing data, outliers, and errors. To the extent possible, we compared our estimates with published reports using these or similar SSA data, such as expert studies. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable to examine the extent to which the pandemic may have influenced eligible workers’ decisions to claim Social Security benefits.

To assess the reliability of DOL’s Unemployment Insurance data, we reviewed relevant documentation; interviewed DOL officials with expertise on these data; and conducted electronic tests to identify missing data, outliers, and errors. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable to determine the extent to which individuals of selected ages claimed Unemployment Insurance from 2018 through 2023.