HEALTH INSURANCE

Enhanced Data Matching Could Help Prevent Duplicate Benefits and Yield Substantial Savings

Report to the

Chairman

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Chairman, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, House of Representatives.

For more information, contact: M. Hannah Padilla at padillah@gao.gov or Seto J. Bagdoyan at bagdoyans@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

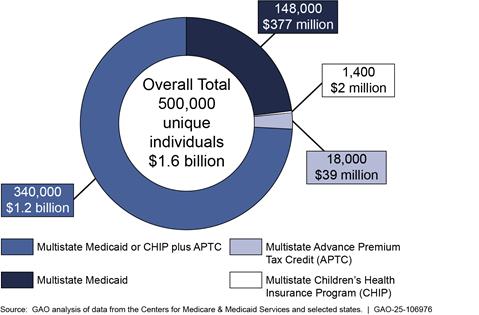

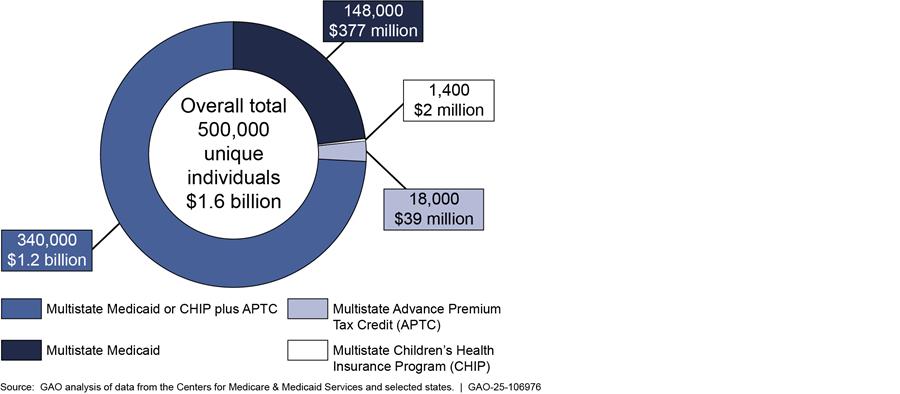

For fiscal year 2023, the federal government and six selected states—California, Georgia, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas—paid health insurance entities at least $1.6 billion in potential overpayments or fraud for duplicate health care coverage or benefits. The payments were made on behalf of approximately 500,000 individuals who were simultaneously enrolled across multiple states in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) or receiving an advance premium tax credit (APTC) across multiple states. These payments were made on behalf of individuals to managed care organizations in the form of capitated payments for Medicaid and CHIP or to health insurance issuers through APTC.

The $1.6 billion in potential overpayments identified in GAO’s analyses may be relatively small compared to the total enrollment numbers, outlays, and expenditures. However, they represent a significant amount of potential overpayments largely stemming from six selected states in GAO’s review. It is also likely that the counts and dollar figures GAO identified were partially attributable to COVID-19-related continuous enrollment conditions for Medicaid and some CHIP enrollees. Specifically, as a condition for receiving temporarily enhanced federal funding during the pandemic, states were required to keep Medicaid and some CHIP beneficiaries continuously enrolled unless an individual requested voluntary termination of eligibility, or the individual ceased to be a resident of the state. Nonetheless, the conditions did not prevent states from disenrolling individuals who were confirmed to no longer be state residents, and duplication of Medicaid, CHIP, or APTC benefits across states for individuals should not have occurred.

Note: Individual counts may overlap between categories. The overall total reflects aggregated values after removing duplicate individuals across programs and states. Due to rounding, individual counts and dollar amounts may vary slightly from the totals.

Why GAO Did This Study

Federally funded health care programs are susceptible to significant improper payments, including fraud. For example, for fiscal year 2024, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) estimated $4.9 billion in improper Medicaid payments for ineligible individuals. HHS’s CMS oversees three principal health care programs generally available for eligible persons under 65 years of age: Medicaid, CHIP, and the health insurance marketplaces, through which eligible individuals can purchase health insurance.

To help pay for marketplace health insurance, federal law provides for a premium tax credit to individuals who meet certain income and other eligibility requirements. Individuals can choose to have the marketplace compute an estimated credit that is paid directly to their issuers on their behalf, known as APTC, which lowers their monthly premium payments. However, individuals are generally not eligible for APTC if they qualify for Medicaid or CHIP. Further, individuals should not be simultaneously enrolled in any of these programs in multiple states.

GAO was asked to review issues related to duplicate health care coverage payments in Medicaid, CHIP, and APTC. This report (1) describes instances of payments made for duplicate Medicaid and CHIP coverage in selected states and potentially ineligible APTC benefits nationwide and (2) examines the extent to which CMS and states have designed processes to identify and prevent duplicate cross-state health care coverage in these programs.

GAO conducted data matching of enrollment and payment data to identify duplicate payments made for Medicaid or CHIP in six selected states and APTC benefits nationwide. Among other

Marketplaces’ processes to identify and prevent simultaneous cross-state health care coverage or benefits are limited.

· Marketplaces do not have sufficient processes to identify and prevent simultaneous cross-state APTC benefits—such as preventing duplicate Social Security numbers from being used on multiple marketplace health plans simultaneously. Without designing sufficient processes to identify and prevent duplicate cross-state enrollment within the marketplaces, there is an increased risk that APTC benefits will be improperly paid to multiple health insurance issuers on behalf of the same individual.

· Additionally, marketplaces do not have processes to identify individuals receiving simultaneous cross-state Medicaid or CHIP coverage. Moreover, none of the marketplaces submit qualified health plan enrollment data, including APTC information, to the Public Assistance Reporting Information System (PARIS)—a data-matching service used to identify duplicate cross-state payments—or another data-matching system. Requiring marketplaces to submit such data would enable the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and state agencies to use the data to identify enrollee matches between APTC and CHIP or Medicaid, which could then be resolved to verify eligibility or terminate benefits, as appropriate.

Most states Medicaid and CHIP agencies reported that they submit Medicaid and CHIP enrollment data to PARIS for data matching. However, the enrollment populations and frequency of interstate data matching varied among states for both Medicaid and CHIP.

Some states exclude categories of enrollees from their submission, and some do not submit quarterly because it is not required. Until state Medicaid and CHIP agencies are required to submit enrollment data to PARIS or another data-matching system for interstate data matching on a frequent recurring basis, state Medicaid and CHIP agencies will continue to face greater risk of being unaware of potential instances of duplicate cross-state Medicaid and CHIP enrollment.

factors, states were selected based on average monthly CHIP and Medicaid enrollment by state, number of individuals receiving APTC by state, state migration trends, and proximity to one another. GAO also conducted three nationwide surveys of state Medicaid agencies, state CHIP agencies, and state-based marketplaces.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to CMS. One recommendation is that CMS design or modify controls to help detect and prevent duplicate Social Security numbers from being used on multiple marketplace policies receiving APTC benefiits. Additionally, GAO is recommending that CMS require marketplaces and Medicaid and CHIP agencies to (1) submit all enrollment data to PARIS, or another data-matching system, for interstate matching on a frequently recurring basis and (2) resolve all matches to verify eligiblity or terminate coverage as appropriate. HHS neither agreed nor disagreed with these recommendations.

Abbreviations

|

ACF |

Administration for Children and Families |

|

APTC |

advance premium tax credit |

|

CHIP |

Children’s Health Insurance Program |

|

CMA |

computer matching agreement |

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

DMDC |

Defense Manpower Data Center |

|

DNP |

Do Not Pay |

|

DOB |

date of birth |

|

EVS |

Enumeration Verification System |

|

FRDAA |

Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

Hub |

Federal Data Services Hub |

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

MCO |

managed care organization |

|

NCOA |

National Change of Address Records |

|

OBBBA OMB |

One Big Beautiful Bill Act Office of Management and Budget |

|

PARIS |

Public Assistance Reporting Information System |

|

PIIA |

Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 |

|

SSA |

Social Security Administration |

|

SSI |

Supplemental Security Income |

|

SSN |

Social Security number |

|

VA |

Veterans Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 25, 2025

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

Dear Mr. Chairman:

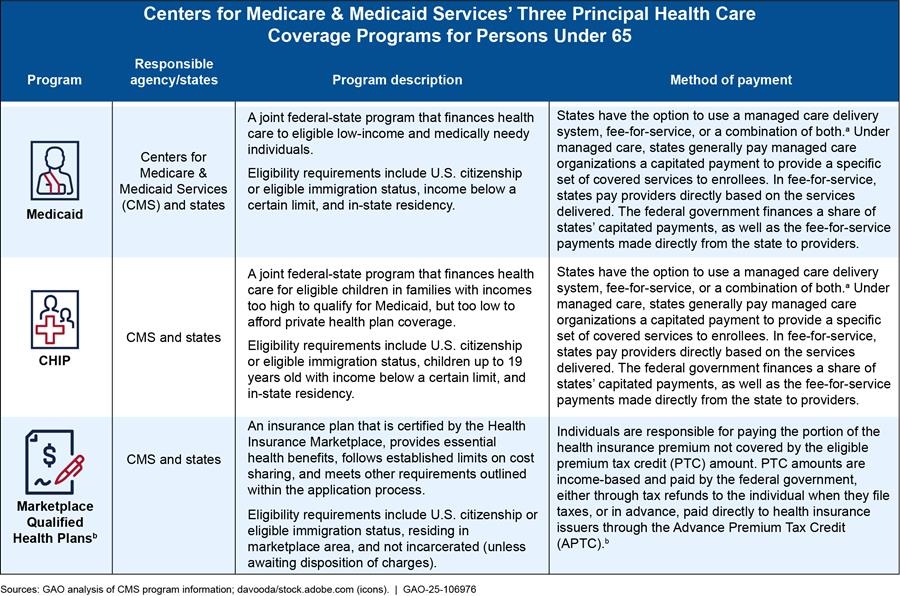

The federal government funds health care coverage through various programs managed by the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are the primary government-sponsored health insurance programs for persons under 65 years of age.[1]

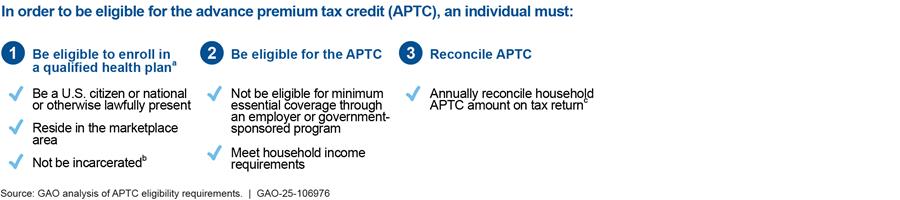

Additionally, in the United States, one option for purchasing health insurance is through health exchanges. These exchanges, commonly called health insurance marketplaces, are discussed in more detail in the background section of this report.[2] To help pay for marketplace health insurance, federal law provides for a premium tax credit to individuals who meet certain income and other eligibility requirements.[3] Individuals can choose to have the marketplace compute an estimated credit that is paid directly to their health insurance issuers on their behalf, known as an advance premium tax credit (APTC), which lowers their monthly premium payments.[4] Alternatively, they can choose to get all the benefit of the credit when they file their tax return for the year.[5]

Federal and state outlays for Medicaid, CHIP, and APTC totaled about $1 trillion for fiscal year 2023. In addition to their size and related expenditures, the complexities of these programs—such as the variation in states’ design and implementation of the programs[6]—pose challenges to CMS oversight and present opportunities for improper payments, including fraud.[7]

Improper payments in CMS programs have been regularly and widely reported, involving billions of dollars. For example, in its fiscal year 2024 financial report, HHS reported approximately $31 billion of estimated improper payments in the Medicaid program, of which HHS estimated $4.9 billion were made for individuals who were not eligible for the Medicaid program or services provided. Since 2003, we have designated Medicaid as a high-risk program due to its size; complexity; and vulnerability to fraud, waste, and abuse.[8] As of January 2025, we had 65 open recommendations to CMS related to strengthening Medicaid program integrity.

Individuals are generally not eligible for APTC if they qualify for minimum essential coverage through a government-sponsored program, such as Medicaid or CHIP.[9] Further, for Medicaid, CHIP, and marketplace plan coverage, state residency is part of the eligibility criteria.[10] Therefore, individuals should not be simultaneously enrolled in any of these programs, and therefore receiving duplicate health care coverage or benefits, in multiple states.[11] You asked us to review issues related to the identification of duplicate health care coverage and potential overpayments in Medicaid, CHIP, and APTC.[12]

This report describes instances of potential overpayments made for duplicate cross-state health care coverage or benefits, if any, on behalf of individuals enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP managed care in selected states; a marketplace plan while receiving APTC benefits in any state; and Medicaid or CHIP managed care in selected states while receiving APTC in any state. Additionally, this report examines the extent to which CMS and states have designed processes to identify and prevent duplicate cross-state health care coverage or benefits in the Medicaid, CHIP, and APTC programs.[13]

We selected six states for our review: California, Georgia, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas. To select the states, we considered the following factors, among others: average monthly enrollment by state for Medicaid and CHIP for calendar year 2022, the number of marketplace consumers receiving APTC in each state for the 2022 open enrollment period, state migration inflow and outflow for calendar year 2021, states’ adoption of Medicaid expansion as of 2023, and the proximity of states to one another.

To address our first objective, we obtained managed care enrollment and payment data for Medicaid and CHIP from each of the six selected states for fiscal year 2023.[14] We also obtained marketplace enrollment and payment data from fiscal year 2023, including APTC information, from CMS. We conducted data matching to identify instances of potential improper capitation payments or APTC payments made (1) for duplicate Medicaid or CHIP coverage across the six selected states, (2) on behalf of individuals enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP in any of the six selected states while simultaneously receiving APTC in any state at the same time, and (3) for duplicate APTC payments in any state.[15]

For the purposes of our report, a match refers to an individual record in one state or program that shares the same Social Security number (SSN) and date of birth (DOB) with a record in another state or program. Although SSNs are unique to individuals, we also used DOB to minimize potential false positives and increase confidence that matched records across different programs or states referred to the same individual.

A match alone does not indicate duplicate health care coverage. To identify duplicate health care coverage, we analyzed the data to identify overlapping enrollment and benefit payments—specifically, simultaneous capitation payments or APTC benefits—made on behalf of the same individual across multiple states or programs during the same months. In other words, a duplicate match identifies an individual who appears in multiple datasets, while duplicate health care coverage reflects what benefits may have been received simultaneously, potentially indicating eligibility issues or improper payments.

In reviewing potential duplicate Medicaid and CHIP health care coverage across the six selected states, we applied a 3-month buffer to account for individuals who may have moved from one state to another but remained temporarily enrolled in both due to administrative processing. This was in part necessary given the continuous enrollment condition associated with states receiving additional federal funding during the COVID-19 pandemic, which is discussed later in this report. We also applied a 3-month buffer to our analysis of individuals enrolled in a qualified health plan receiving APTC benefits while enrolled in any of the selected states’ CHIP or Medicaid program. This buffer is intended to only account for individuals who may have moved from one state to another but remained enrolled in both states for at least 3 or more months and reflects typical state disenrollment timelines, according to agency officials. Moreover, it helps avoid overstating duplication caused by normal transitions.

The buffer also highlights patterns that fall outside the 3-month window, which may signal patterns inconsistent with legitimate program use, such as fraud or program misuse.[16] For example, extended multi-state enrollment across states may warrant further review for improper payments or fraudulent activity, such as intentional misrepresentation of residency or simultaneous benefit claims.

We did not apply the buffer to our analysis of cross-state APTC, wherein an individual is enrolled in a qualified health plan with APTC benefits being paid on their behalf in any two or more states. Any simultaneous coverage across states in the same month is inconsistent with program rules and more likely to reflect an eligibility or payment error.[17] Accordingly, we counted all instances of simultaneous APTC coverage in our analysis regardless of duration.

We also compared data with published enrollment totals, interviewed knowledgeable agency and state program officials, analyzed selected data fields within the provided datasets, and processed records with missing or potentially invalid SSNs through the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) Enumeration Verification System (EVS).[18] We used EVS to help determine whether matched records across states belonged to the same individual or to different individuals who may have shared similar or incorrect identifiers, such as SSNs, DOBs, or last names. Based on our reliability assessment results, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of matching and identifying potential overpayments for individuals receiving duplicate coverage or benefits. Our results are not generalizable to all states or the federal and state marketplaces, but they provided valuable insights into the magnitude of potential duplicate coverage or benefits.

To address our second objective, we reviewed federal statutes and their implementing regulations regarding eligibility requirements for the Medicaid, CHIP, and APTC programs; leading practices for managing fraud risks in federal programs; and CMS guidance for assessing key control activities and processes the states and CMS designed to identify and prevent duplicate cross-state health care coverage or benefits in Medicaid, CHIP, and APTC.[19] We conducted surveys of state Medicaid agencies, state CHIP agencies, and state-based marketplaces about their program structures, processes for determining and identifying changes in residency of applications, processes for identifying and preventing duplicate health care coverage or benefits, and barriers and potential improvements for identifying duplicate health care coverage or benefits.[20] Appendix I provides additional details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

CMS oversees three principal health care coverage programs generally available for eligible persons under 65 years of age: Medicaid, CHIP, and the health insurance marketplaces through which individuals can apply for APTC when enrolling in a qualified health plan.[21] See figure 1 for information about the three programs.

Figure 1: Summary of Selected Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Health Care Coverage Programs

Note: In certain instances, individuals aged 65 and over are eligible for and can be enrolled in Medicaid.

aMedicaid and CHIP managed care provide for the delivery of health benefits and additional services through contracted arrangements between state agencies and managed care organizations that accept a set (capitation) payment for these services, typically per enrollee per month. Capitation payments are fixed amounts of money paid to a managed care organization to cover health care services for a set period of time.

bEligible individuals may receive a PTC established to help pay for health care coverage. The PTC is refundable and advanceable so individuals may claim some or all of the tax credit immediately to lower monthly payments or apply it to their annual federal income tax returns. In cases where individuals accept APTC, CMS pays it to the health insurance issuers. Federal income tax return reconciliation is completed for the household of the individual receiving APTC.

Medicaid and CHIP

Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that finances health care for millions of Americans, including eligible low-income and medically needy individuals. Medicaid is administered by states according to federal requirements and is funded jointly by states and the federal government. In general, an individual must be a resident of a particular state to enroll in that state’s Medicaid program and therefore should not be enrolled in Medicaid in more than one state at the same time.[22]

CHIP is a federal-state program that finances health care for eligible children in families with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low to afford private health plan coverage. The states and the federal government jointly fund CHIP. States have three options for structuring their CHIP:

· operate CHIP separate from Medicaid,

· include CHIP-eligible populations in an expansion of their Medicaid program, or

· operate a combination of the two approaches.[23]

State Medicaid and CHIP agencies can enter into contractual agreements with managed care organizations (MCO) to provide a specific set of covered services for a fixed periodic payment, typically monthly, per enrollee. This is known as a capitation payment. State agencies make capitation payments to MCOs regardless of whether a beneficiary receives services during the period covered by the payment. MCOs are the most common method for delivering services for Medicaid and CHIP.

Qualified Health Plans and APTC

To qualify for a premium tax credit, individuals must be enrolled in a qualified health plan offered through a marketplace and meet certain criteria.[24] These tax credits can be paid in advance through an APTC. See figure 2 for APTC eligibility requirements.

aIn order to apply and qualify for the APTC, an individual must first be enrolled in a qualified health plan offered through the individual’s respective marketplace. The eligibility requirements shown above only reflect those that pertain to an individual applying during the open enrollment period, as there may be additional requirements during special enrollment periods.

bAn incarcerated individual who is awaiting disposition of charges is eligible for a qualified health plan.

cTax return reconciliation is completed for the household of the individual receiving advance payments toward insurance premiums.

States may elect to rely on the federally facilitated marketplace or operate their own health care marketplace.

· Federally facilitated marketplace: States can choose to have CMS operate their marketplaces on the federal platform—the federally facilitated marketplace. Consumers in states that operate on the federally facilitated marketplace apply for and enroll in coverage through Healthcare.gov. For plan years 2023 and 2024, there were 30 and 29 states, respectively, operating on the federally facilitated marketplace. Of our six selected states, Georgia, Tennessee, and Texas were operating on the federally facilitated marketplace for plan year 2023.[25]

· State-based marketplace: States can choose to operate, with HHS’s approval, state-based marketplaces using their own eligibility and enrollment platforms.[26] Those doing so are responsible for performing all marketplace functions. Consumers in these states apply for and enroll in coverage through marketplace websites established and maintained by the states. For plan years 2023 and 2024, there were 18 and 19 state-based marketplaces, respectively. Of our six selected states, California, New York, and Pennsylvania were operating their own state-based marketplace for plan year 2023.

· State-based marketplace on the federal platform: States can choose to operate their own marketplace to perform certain core functions while relying on the federal platform to perform eligibility and enrollment and associated functions. For plan years 2023 and 2024, there were three state-based marketplaces on the federal platform.

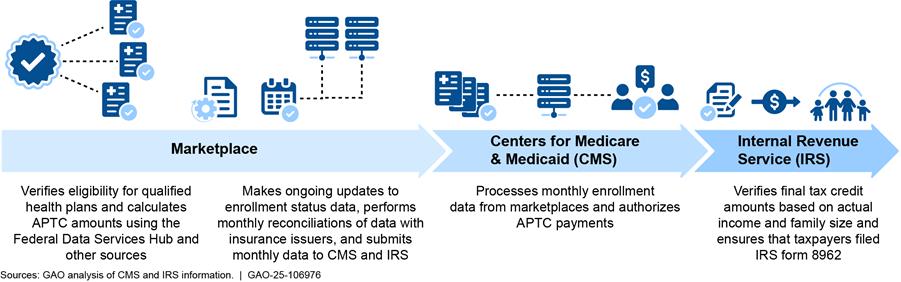

CMS is responsible for approving and overseeing the establishment of state-based marketplaces and maintaining the federally facilitated marketplace.

Marketplaces estimate the amount of the tax credit for which individuals are eligible based on their reported anticipated family sizes and household incomes for the year. Taxpayers who choose to have the credit paid through the APTC must reconcile on their federal income tax returns the amount of APTC paid to issuers on their behalf with the premium tax credit they were ultimately eligible for based on actual family sizes and incomes reported when those individuals file their federal income tax returns.[27]

During this reconciliation process, the taxpayer may be responsible for repaying the excess APTC amount paid to an issuer or may receive an additional tax credit.[28] However, federal law limits the amount of excess APTC overpayments that individuals must repay, based on their household incomes as a percentage of the federal poverty level and filing status. As a result, individuals may not have to repay the full amount of excess APTC payments made to issuers that may otherwise be due.

The Department of the Treasury’s Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is responsible for ensuring that individuals for whom the APTC benefits are paid to issuers comply with their tax-filing requirements, including reconciling their APTCs with their allowed premium tax credit on their federal income tax returns for the year of coverage.[29] IRS relies on marketplace determinations of eligibility for the premium tax credit regarding other minimum essential coverage, such as Medicaid or CHIP. According to IRS officials, during the tax filing process, IRS does not have information to determine if a taxpayer had overlapping coverage.

See figure 3 for a summary of roles and responsibilities for health care marketplaces.

Figure 3: Roles and Responsibilities for Operating the Advance Premium Tax Credit (APTC) in Marketplaces

Note: CMS operates the federally facilitated marketplace and oversees the state-based marketplaces. CMS is also responsible for processing the enrollment data from all marketplaces and coordinating with IRS for APTC payments. At reconciliation, taxpayers must report the amount of APTC received on their federal tax returns using IRS Form 8962, Premium Tax Credit.

Data Matching

Data matching is a process in which information from one source is compared with information from another, such as government or third-party databases, to identify any inconsistencies. State Medicaid and CHIP agencies and marketplaces use various data-matching services and tools, such as the Federal Data Services Hub (Hub), the Public Assistance Reporting Information System (PARIS), and periodic data matching, to help minimize duplicate payments.

Federal law requires marketplaces to verify certain application information to determine applicant eligibility for enrollment and, if applicable, the premium tax credit. A key factor in administering the credit effectively and efficiently is eligibility verification activities. Such activities reasonably assure that only qualified individuals receive the premium tax credit and any advance payments toward their insurance premiums through the APTC. As such, federal law requires that an electronic verification system or another CMS-approved method verifies certain applicant-submitted information, such as household income and family size.

The Hub

CMS developed the Hub, which is available to all marketplaces so that they may perform certain required eligibility verifications in an automated manner.[30] Marketplaces send applicant data to the Hub. The Hub then verifies individuals’ data against information in existing secure and trusted federal and state databases.

PARIS

Operated by HHS’s Administration for Children and Families (ACF), PARIS is a federal-state partnered data-matching service that assesses whether recipients of public assistance receive duplicate benefits, such as health care coverage, in two or more states.[31] Federal regulations require that all state Medicaid eligibility determination systems must conduct data matching through PARIS.[32] PARIS interstate matching provides state Medicaid agencies with a method to submit their data to be compared with data from other state Medicaid agencies and ACF’s federal partners. State Medicaid and CHIP agencies then receive match results to assist in detecting and preventing duplicative and improper payments.

Once a state agency receives PARIS interstate results that suggest an individual is obtaining benefits in multiple states, the agency is expected to determine whether the individual retains continued eligibility for benefits in that state.[33] State agencies may use local benefit office staff, fraud investigators, or both to review and resolve PARIS interstate matches.

PARIS matching services are typically available to agencies on a quarterly basis (February, May, August, and November). Although state agencies are not required to participate in each quarterly opportunity to match participants, ACF has established August as the prioritized required match.[34] ACF did not facilitate the May 2024, and delayed the August 2024, quarterly data matches due to an expired memorandum of agreement and change in technical service provider (see app. II for additional details).

Periodic Data Matching

To ensure individuals remain eligible for APTC, the marketplaces generally must conduct periodic data matching at least twice a year with their respective state Medicaid and CHIP agencies.[35] These actions are designed to determine whether consumers are improperly receiving APTC benefits while simultaneously enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP within their own state.

COVID-19 Pandemic Conditions

Typically, states are required to redetermine the eligibility of Medicaid and CHIP enrollees once every 12 months and disenroll those who were no longer eligible.[36] States are also required to maintain timeliness and performance standards for determining eligibility in the event of a change in enrollees’ circumstances, such as residency.[37] Federal regulations require states to promptly redetermine eligibility when they receive reliable information about changes in enrollee circumstances.[38] Receiving Medicaid in another state typically represents a potential change in an enrollee’s circumstances, which requires the state to contact the enrollee and attempt to verify state residency before termination.[39]

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act provided additional federal funding to states during the COVID-19 pandemic.[40] As a condition for receiving this temporarily enhanced federal funding, the law required states to keep Medicaid beneficiaries continuously enrolled unless an individual requested voluntary termination of eligibility, or the individual ceased to be a resident of the state.[41] Medicaid enrollment increased more than 30 percent (22.4 million individuals) from February 2020 through February 2023, which was during the COVID-19 pandemic. This provision also helped maintain enrollment in CHIP in states that operate CHIP as an expansion of Medicaid.[42]

During the pandemic, CMS instructed states not to disenroll beneficiaries based on their failure to respond to a request for additional information from the state Medicaid agency. For example, if a state requested additional information to confirm an individual’s current state of residence and the individual failed to respond, the state was not permitted to terminate the individual’s Medicaid eligibility. The only exception was for individuals receiving benefits in more than one state that a state had identified by using PARIS. In these instances, the state could consider the individual as no longer being a resident of the state provided the state took reasonable measures to determine state residency prior to termination.[43]

Since the continuous enrollment condition ended in March 2023, states have been transitioning from the continuous enrollment period to an unwinding period requiring states to resume full eligibility redeterminations, including disenrollments. The unwinding period was originally set to expire on July 31, 2024; however, CMS granted states authority to restore timely processing of all renewals, including allowing states to complete work on all unwinding-related renewals, by December 31, 2025.[44]

Fraud Risk Management

GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework provides a comprehensive set of leading practices for agency managers to develop or enhance existing efforts to combat fraud in a strategic, risk-based manner.[45] As required under the Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 (FRDAA) and its successor the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 (PIIA), the leading practices in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework are incorporated into the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) guidelines for agency controls.[46] OMB Circular A-123 guidelines directed agencies to adhere to the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices as part of their efforts to effectively design, implement, and operate an internal control system that addresses fraud risks.[47] Among the leading practices identified in the framework is the use of data analytics. This includes the use of data matching to verify key information for eligibility determinations and to identify potential fraud or improper payments.

Duplicate Health Care Coverage Resulted in Potential Overpayments or Fraud of at Least $1.6 Billion in Fiscal Year 2023

Our analysis of fiscal year 2023 managed care enrollment and payment data for Medicaid and CHIP for six selected states and nationwide marketplace APTC data found that health insurance entities, such as MCOs, received over $1.6 billion in potential overpayments or fraud from duplicate health care coverage or benefits.[48] As shown in figure 4, payments were made on behalf of about 500,000 individuals who were simultaneously enrolled in

1. Medicaid in two or more selected states,

2. CHIP in two or more selected states,

3. a qualified health plan with APTC benefits being paid on their behalf in any two or more states, or

4. a qualified health plan in any state with APTC benefits being paid on their behalf while simultaneously enrolled in any of the selected states’ CHIP or Medicaid programs.

Figure 4: Duplicate Health Coverage Identified Using Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Data for Six Selected States and Nationwide Advance Premium Tax Credit Data from October 1, 2022, through September 30, 2023

Note: Individual counts may overlap between categories. The overall total reflects aggregated values after removing duplicate individuals across programs and states. Due to rounding, individual counts and dollar amounts may vary slightly from the totals.

We identified the duplicate health care coverage and associated potential overpayments through our analysis of approximately 32.6 million unique SSNs associated with Medicaid totaling nearly $181 billion in capitation payments in fiscal year 2023 and approximately 2.1 million unique SSNs associated with CHIP totaling nearly $3.3 billion in capitation payments across the six selected states. In addition, our analysis included approximately 12 million unique SSNs with associated APTC benefits totaling nearly $62.6 billion through the federally facilitated marketplace and 5.1 million unique SSNs with about $29.4 billion in APTC benefits through the state-based marketplaces.

Some individuals may have moved between states during the time of our review and would require time to report the change or for the state to identify and process the change. To account for this possibility, only individuals with at least 3 consecutive months of simultaneous enrollment were considered to be duplicates for our Medicaid and CHIP matches. We did not apply the 3-month buffer in our analysis of multistate APTC benefits where individuals are enrolled in a qualified health plan with APTC benefits being paid on their behalf in any two or more states.

Our findings related to Medicaid and CHIP coverage are limited to the six selected states and are not projectable nationally. Our findings related to APTC benefits consider all nationwide marketplace enrollments (including all state-based marketplaces and the federally facilitated marketplace). However, given the extent of duplication in our findings for our six selected states and the marketplaces, it is possible that similar duplication is occurring in other states not included in our review. Several factors support this likelihood: people move between states, not all states consistently participate in data-matching efforts like PARIS interstate matching, and variations of enrollment and disenrollment systems and practices exist by state.

Additionally, certain COVID-19 pandemic-related conditions, such as the continuous enrollment condition, contributed to an increase in enrollments during our review period. This condition also likely contributed to an increase in the number of individuals with duplicate health coverage during our 2023 review period. As previously mentioned, to receive enhanced federal funding, states were generally required to keep enrollees continuously enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP Medicaid-expansion programs for a period during the COVID-19 pandemic. There were certain exceptions to the continuous enrollment condition, such as if the individual ceased to be a state resident.[49]

As a result, when people moved to other states during the continuous enrollment period and specifically during our fiscal year 2023 review period, they may have remained enrolled in their original states. State officials told us that they had to take affirmative steps to verify changes in residency and be certain before terminating anyone’s coverage. These processes to determine if someone could be disenrolled would often take several months. As discussed later in this report, we also identified potential control weaknesses that may increase the risk of not identifying and preventing duplicate coverage during normal operations.

Six Selected States Made Hundreds of Millions in Capitation Payments on Behalf of Individuals Simultaneously Enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP

After applying our 3-month buffer, we identified over 149,000 individuals simultaneously enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP in multiple selected states during fiscal year 2023. Specifically, approximately 148,000 individuals enrolled in Medicaid and over 1,400 enrolled in CHIP were simultaneously enrolled for at least 3 consecutive months in at least two of the six states we reviewed. The data we analyzed for the six selected states included approximately 32.6 million unique SSNs enrolled in Medicaid and 2.1 million unique SSNs enrolled in CHIP.

To identify duplicate Medicaid or CHIP coverage, we compared enrollment and payment data across the six selected states using SSN and DOB as a composite unique identifier for each individual. If an individual with the same SSN and DOB appeared in one state’s dataset and another state’s dataset and capitation payments were made on their behalf in those states for at least 3 overlapping months, we considered this a case of duplicate health care coverage with potential overpayments.

For example, we identified 42,830 individuals in one of the six selected states that were simultaneously enrolled in at least one of the other five states for at least 3 consecutive months. These individuals represent the number of unique SSN and DOB combinations found in one state that also appeared in at least one of the other six selected states. We repeated this process for each of the six states. We did not determine which state, if any, made an improper capitation payment or was responsible for duplicate coverage, as this was outside the scope of our review.

To determine the overall total, we counted each SSN-DOB combination only once across all six states in order to avoid overcounting. As a result, our total reflects the number of unique individuals, based on the composite identifier of SSN and DOB, who appeared in enrollment or payment data from more than one state.

The six selected states and the federal government paid a minimum of $379 million in duplicate capitation payments to MCOs for individuals enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP coverage in more than one state. This represents at least $377 million in capitation payments associated with Medicaid enrollments and at least $2 million in capitation payments associated with CHIP enrollments. Though duplicate capitation payments represent a small percentage of total joint federal and state outlays to MCOs, the dollar amounts involved remain substantial. In the data we analyzed, joint capitation payments made by the six selected states and the federal government to MCOs totaled nearly $184 billion, of which approximately $181 billion was for Medicaid and nearly $3.3 billion was for CHIP.

In some instances, the potential improper payment amounts could be higher. When calculating the total potential improper capitation payments made to MCOs on behalf of individuals receiving health care coverage in multiple states, we used the state with the lowest total capitation payment amount because we did not determine which state’s payment was potentially improper as part of our review. For example, if a MCO in New York received a monthly capitation payment of $100 for an individual from May to July 2023 and a MCO in Pennsylvania also received monthly capitation payments of $150 for the same individual during the same 3 months, we used the lower capitation payment amount of $100 to calculate the potential overpayment. In this example, the potential improper payment is at least $300.

CMS Paid over $1 Billion in Tax Credits on Behalf of 340,000 Individuals Also Enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP in Selected States

Through our analyses, we found that CMS paid over $1 billion in APTC benefits to issuers on behalf of approximately 340,000 individuals who also had capitation payments made on their behalf for Medicaid or CHIP coverage in our six selected states, after applying a 3-month buffer. Being enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP indicates potential ineligibility for APTC due to simultaneous enrollment. Of the 340,000 individuals, about 318,000 individuals were enrolled in Medicaid managed care and about 21,000 individuals were enrolled in CHIP managed care. APTC benefit payments were made on behalf of these 340,000 individuals enrolled in marketplace coverage for at least 3 consecutive months during fiscal year 2023. Although these 340,000 individuals represent a small share of the over 32.6 million unique SSNs for Medicaid and over 2.1 million unique SSNs for CHIP that we reviewed, the associated APTC benefit payments highlight the potential impact of duplicate enrollment across programs and underscore the importance of effective data-matching controls.

We did not determine which program, if any, was responsible for improper payments or duplicate coverage in cases involving APTC. However, we treated APTC benefits as potentially improper, since individuals enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP are generally not eligible to receive APTC benefits.

For example, our analysis identified an individual with an SSN and DOB in the APTC dataset as enrolled in a qualified health plan in one state. The same SSN and DOB combination also appeared in another state’s Medicaid capitation file, which showed that the individual was enrolled in Medicaid managed care in another state during the same 3 or more months. We identified this overlap using our composite unique identifier (SSN and DOB) and flagged it as a potential case of duplicate coverage. Because Medicaid and APTC benefits are generally mutually exclusive, and the individual appeared to be enrolled in both programs in different states during the same 3 or more months, we considered this a potentially improper APTC payment. While certain exceptions may apply, simultaneous enrollment in Medicaid or CHIP and a qualified health plan with APTC generally indicates a potential eligibility issue.

The potential overpayments on behalf of individuals enrolled in duplicate coverage or benefits total more than $1 billion. Specifically, APTC benefits of about $1.1 billion were paid to issuers on behalf of individuals who simultaneously had capitation payments paid to MCOs for Medicaid coverage in one of our six selected states. Similarly, APTC benefits of about $109.6 million were paid to issuers on behalf of individuals who simultaneously had capitation payments paid to MCOs for CHIP coverage.[50] Since individuals eligible to receive certain types of minimum essential coverage, such as Medicaid and CHIP, are not eligible to receive APTC benefits, we used the APTC benefit amounts when calculating the total potential overpayment.[51]

While the potential overpayments we identified associated with individuals simultaneously enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP represent a small fraction of the total APTC benefits—$92 billion—these amounts remain substantial and warrant attention. Even limited instances of duplicate enrollment can result in significant costs and signal potential vulnerabilities in program oversight.

However, it is possible that in some cases an individual was enrolled but not eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, making the capitation payment to the managed care organization the overpayment instead. For example, an individual may have originally lived in one state where the individual was enrolled in Medicaid managed care. The individual subsequently moved to another state where the individual qualified for APTC and no longer qualified for Medicaid. If the original state did not disenroll the individual from Medicaid due to the move, then in this situation, the overpayment would be the Medicaid capitation payment because the individual was no longer eligible for Medicaid since the individual no longer lived in that state.

CMS Paid over $39 Million in Potentially Improper APTC Payments on Behalf of 18,000 Individuals with Simultaneous Marketplace Enrollment

Our analysis identified over 18,000 individuals enrolled in a qualified health plan in more than one state and receiving APTC for the costs of both plans at the same time. While the total APTC benefit amounts associated with these individuals were relatively small, these occurrences illustrate how duplicate enrollment across states can lead to improper payments and raise concerns about program oversight and eligibility verification. These individuals fall into three categories:

· Within the 32 states using federally facilitated marketplaces or operating state-based marketplaces using the federal platform as of October 31, 2023, we found approximately 5,600 individuals who simultaneously appeared in more than one state. These individuals had potential improper APTC benefits paid to issuers on their behalf of at least $13.5 million.

· Similarly, we found approximately 2,200 individuals simultaneously enrolled in more than one of the 19 state-based marketplaces as of as of October 31, 2023. These individuals had potential improper APTC benefits paid to issuers on their behalf of at least $6.4 million.

· We also compared the federally facilitated and state-based marketplaces and found that over 10,000 individuals had potential improper APTC benefits paid to issuers on their behalf of at least $19.1 million.

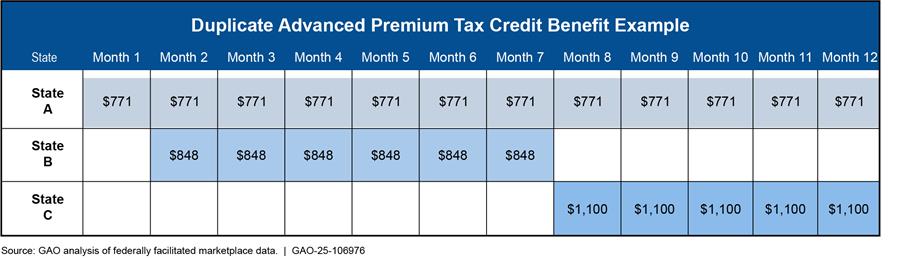

For the APTC scenarios listed above, we did not apply a 3-month buffer because any simultaneous enrollment across states in the same month is inconsistent with program rules and more likely to indicate a potential eligibility or payment issue. The overall potential improper APTC benefits paid to issuers on behalf of individuals in all three categories combined was at least $39.1 million, which does not account for any repayment of excess APTC that may have been collected from the reconciliation process at tax time. See figure 5 for an example of an individual that had APTC payments simultaneously made to issuers on the individual’s behalf in multiple states. In that example, one state paid $771 to an insurer for each of the 12 months, and for 5 of those months another state also paid $1,100 to an insurer on behalf of the same individual.

Figure 5: Illustrative Case of One Individual with Potentially Duplicate APTC Benefits Across Three States

For this analysis, we reviewed data from a single source. CMS data from both the federally facilitated marketplace and state-based marketplaces contained all the necessary information for our analysis. SSNs, which serve as unique identifiers, are essential for reconciling APTC benefits on individual federal income taxes.[52]

However, data matching can be affected by transposed digits; keying errors; or unreported name changes, such as those due to marriage or legal updates, that are not reflected in SSA records. When an individual provides an incorrect SSN or name, IRS may be unable to accurately identify them during the reconciliation process.[53] IRS officials told us it is not part of their process to identify APTC payments made on behalf of an individual who may have been ineligible due to being simultaneously enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP.

In addition, an SSN incorrectly used to receive APTC benefits in multiple states simultaneously could indicate a number of possible program integrity issues: (1) overpayments to issuers on behalf of an individual, (2) data reliability issues with marketplace data,[54] and (3) potential risk of synthetic identity fraud.[55] For example, an individual could be enrolled twice in a marketplace using the same SSN but two different addresses.[56] Such a scenario could result in the marketplace overpaying APTC benefits to issuers on behalf of the individual. Similarly, an individual or multiple individuals could potentially enroll using different addresses with the same SSN, either fraudulently or erroneously, resulting in the marketplace potentially overpaying APTC benefits to issuers on behalf of one or both individuals using the same SSN. Moreover, these types of scenarios could cause additional challenges reconciling APTC benefit amounts for the individual whose SSN was incorrectly used and cause potential problems in processing the federal income tax return.

We used SSA’s EVS to verify names and SSNs by matching the personally identifiable information for all individuals in our datasets against SSA records, allowing us to identify discrepancies or potential data quality issues. Specifically, for the approximately 18,000 individuals receiving APTCs for enrollment in qualified health plans in multiple states within the marketplaces, we used SSA’s EVS to identify whether the SSN, name, and DOB matched SSA’s records. We reviewed 12 million unique SSNs for the federally facilitated marketplace and 5.1 million for the state-based marketplaces. We found that out of the approximately 18,000 individuals, about

· 14,000 were validated by SSA records, meaning the same identity was used in multiple states simultaneously;

· 1,800 had a different unique SSN in SSA’s records, meaning that the SSN on file with the marketplace was incorrect;[57] and

· 2,200 either did not have a unique SSN or were not found in SSA records, which could indicate data issues or potentially fictitious identity information.

Continuous Enrollment and Temporary Program Flexibilities During COVID-19 Affected Programs’ Effectiveness in Detecting and Preventing Duplicate Health Care Coverage

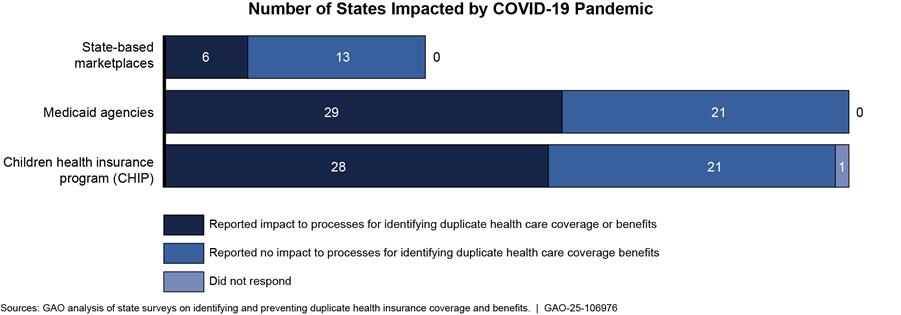

While our analysis identified instances of duplicate enrollment and potential improper payments, understanding the broader program environment during the review period is critical. In particular, continuous enrollment conditions and temporary program flexibilities implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected states’ and programs’ abilities to detect and prevent duplicate health care coverage. According to our nationwide survey of Medicaid and CHIP agencies, as indicated in figure 6, most state Medicaid and CHIP agencies reported that the continuous enrollment condition and CMS-approved temporary flexibilities the states employed during the COVID-19 pandemic affected their processes to prevent duplicate coverage. In addition, six of the 19 state-based marketplaces also reported that the COVID-19 pandemic affected their ability to identify duplicate health care coverage.

Figure 6: Survey Results on States’ Ability to Identify Duplicate Health Care Coverage During the Pandemic

Note: We received a total of 50 submissions for the Medicaid and CHIP surveys (49 states and the District of Columbia). One state did not complete the Medicaid or CHIP survey. All 19 state-based marketplaces completed the survey for a response rate of 100 percent. One state CHIP agency did not provide an answer to the survey question for this figure.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act included a continuous enrollment condition that provided a temporary 6.2 percent increase in Medicaid funding to states that continued coverage for current enrollees.[58] To receive this additional funding, federal law generally required states to keep enrollees continuously enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP expansion programs unless an individual requested voluntary termination of eligibility or the individual ceased to be a resident of the state.[59]

Per our survey, state agencies and marketplaces reported various changes to their processes for identifying and preventing duplicate health care coverage due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, some state-based marketplaces and Medicaid and CHIP agencies reported pausing their review processes altogether, including periodic data matching or participating in PARIS interstate matching. According to CMS officials, for the federally facilitated marketplace, CMS paused checks to identify simultaneous Medicaid or CHIP enrollment. Other pandemic-related changes reported by the states that affected their ability to prevent duplicate health care coverage included

· suspending actions on PARIS match results during the pandemic;

· requiring states to make several contact attempts before reducing or terminating eligibility of individuals, while still providing hearing rights; and

· suspending actions to terminate coverage for failure to provide verification information.

Medicaid and CHIP Agencies and Marketplaces Have Varying Processes for Detecting Cross-State Enrollment but Could Enhance Data-Matching Efforts

State Medicaid and CHIP agencies and marketplaces have varying processes—such as coordinating with MCOs and using optional data sources—for verifying and detecting changes in residency. The state-based marketplaces do not have processes to identify and prevent simultaneous cross-state health care coverage or benefits. Additionally, the enrollment populations in submitted data, and frequency of interstate data matching, varied among states for both Medicaid and CHIP.

State Medicaid and CHIP Agencies Reported Various Coordination Efforts with MCOs to Detect Changes in Residency

CMS regulations require state Medicaid and CHIP agencies to have contractual agreements requiring MCOs to promptly notify the state when they receive information about changes in an enrolled individual’s residence.[60] As shown in table 1, state Medicaid and CHIP agencies we surveyed generally responded that their MCOs have contractual requirements to report such changes to the state agency. In addition, although CMS guidance does not direct state Medicaid and CHIP agencies to review the use of services by beneficiaries enrolled in managed care, some state agencies reported having processes to conduct such reviews to identify enrolled individuals who may no longer live in the state. For example, state Medicaid and CHIP agencies reported some of the following activities:

· reviewing enrollee use as part of their quarterly PARIS reconciliation process;

· receiving reports from MCOs participating in Medicaid and CHIP on excessive out-of-state usage of medical services and sending information requests to the households for explanation; and

· identifying managed care enrollees for whom no claims have been submitted in 2 years, comparing those enrollees to PARIS match results, and reaching out to applicable individuals to determine appropriate eligibility.

Table 1: Survey Results of State Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP) and Medicaid Agencies’ Requirements for and Coordination with Managed Care Organizations (MCO)

|

State-reported control activities with MCOs to detect changes in residency |

State CHIP agencies with managed care (41 states) |

State Medicaid agencies with managed care (42 states) |

|

Contractual requirements for MCOs to report changes in addresses of beneficiariesa |

40b |

42 |

|

Review of beneficiaries’ continued use of managed care services |

13 |

13 |

Source: GAO analysis of state surveys on identifying and preventing duplicate health care coverage and benefits. | GAO‑25‑106976

Note: Table totals may be greater than the number of state agencies because certain states reported that they have both control activities to detect changes in residency. We received a total of 50 submissions for the Medicaid and CHIP surveys (49 states and the District of Columbia). One state did not complete the Medicaid or CHIP survey. Of the 50 Medicaid and CHIP agencies that completed the survey, 42 and 41, respectively, indicated that they contract with MCOs to deliver coverage.

aOne state specified that for both Medicaid and CHIP, it only has contractual requirements for MCOs to notify the state when they receive information about changes in an enrollee’s circumstances for specific situations, such as dual enrollment in Medicare, Medicaid, or a specialized health plan. For reporting purposes, this state is included in the total counts for Medicaid and CHIP agencies.

bOne state CHIP agency did not indicate whether it had contractual requirements for MCOs to report changes in address of beneficiaries.

Marketplaces and State Medicaid and CHIP Agencies Use Various Optional Mechanisms to Verify Residency and Changes to Residency

Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP regulations grant flexibilities in the verification process for certain eligibility criteria. The flexibilities are designed to minimize administrative costs and burdens on marketplaces, state Medicaid and CHIP agencies, and applicants. For example, all marketplaces may accept self-attestation as proof of residency requirements or opt to perform additional levels of verification, based on the state’s discretion.[61] As such, according to CMS officials, the federally facilitated marketplace does not use any additional data sources to help verify residencies of individuals.

However, per our survey, some state agencies and marketplaces reported taking additional steps to help verify residency eligibility requirements. Specifically, some state agencies and marketplaces reported using various external data sources, such as LexisNexis, state motor-vehicle agency records, the National Change of Address Records service (NCOA), and returned mail services to verify residency of individuals.[62]

Use of such data sources and frequency of verification varied among the state agencies and marketplaces. NCOA was the most frequently reported data source used by state agencies and marketplaces to verify residency. Table 2 provides the number of state agencies and marketplaces that reported using optional data sources to verify self-attested information to determine whether applicants meet the state residency requirement during initial eligibility determinations.

Table 2: Survey Results of State Agencies’ and Marketplaces’ Use of Optional Data Sources to Verify Applicant Residency When Determining Initial Eligibility

|

|

LexisNexis |

State motor-vehicle agency records |

National Change of Address records |

Returned mail services |

Other |

Nonea |

|

State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) agencies |

2 |

8 |

10 |

3 |

3 |

32 |

|

State Medicaid agencies |

2 |

8 |

10 |

3 |

4 |

34 |

|

State-based marketplacesb |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

12 |

Source: GAO analysis of state surveys on identifying and preventing duplicate health care coverage and benefits. | GAO‑25‑106976

Note: We received a total of 50 submissions for the Medicaid and CHIP surveys (49 states and the District of Columbia). One state did not complete the Medicaid or CHIP survey. All 19 state-based marketplaces completed the survey for a response rate of 100 percent. Table totals may be greater than the number of state agencies because certain states reported that they use multiple data sources to verify applicant residency when determining eligibility.

aThis column reflects the number of state agencies or marketplaces that did not report using any optional data sources. Two state CHIP agencies and two state-based marketplaces did not respond to this question.

bThe Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported that it does not use any optional data sources to verify residency when determining initial eligibility for the federally facilitated marketplace.

Table 3 provides the number of state agencies and marketplaces that reported in our survey using optional data sources to verify self-attested information in determining changes in residency after enrollment in the health care program.

Table 3: Survey Results of State Agencies’ and Marketplaces’ Use of Optional Data Sources to Identify Post-Enrollment Changes in Residency

|

Agency/marketplace |

Frequency |

LexisNexis |

State motor-vehicle agency records |

National Change of Address records |

Returned mail services |

Other |

Nonea |

|

State CHIP agencies |

Periodic data matching |

3 |

3 |

11 |

3 |

4 |

33 |

|

Annual review |

0 |

5 |

11 |

2 |

2 |

32 |

|

|

Other (ad hoc) |

3 |

3 |

10 |

8 |

8 |

24 |

|

|

State Medicaid agencies |

Periodic data matching |

3 |

5 |

13 |

2 |

5 |

34 |

|

Annual review |

1 |

6 |

13 |

5 |

3 |

31 |

|

|

Other (ad hoc) |

2 |

3 |

13 |

10 |

10 |

24 |

|

|

State-based marketplacesb |

Periodic data matching |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

16 |

|

Annual review |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

15 |

|

|

Other (ad hoc) |

0 |

1 |

6 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Source: GAO analysis of state surveys on identifying and preventing duplicate health care coverage and benefits. | GAO‑25‑106976

Note: We received a total of 50 submissions for the Medicaid and CHIP surveys (49 states and the District of Columbia). One state did not complete the Medicaid or CHIP survey. All 19 state-based marketplaces completed the survey for a response rate of 100 percent. Periodic data matching refers to checks that occur at least twice a year to determine if individuals are still eligible for their enrolled qualifying health care coverage. During annual review, state agencies and marketplaces determine if individuals are still eligible for their enrolled qualifying health care coverage. States also perform verification during various other instances (other (ad hoc)). Certain states reported that they use multiple data sources to verify applicant residency when determining eligibility.

aThis column reflects the number of state agencies or marketplaces that did not report using any optional data sources. Two state CHIP agencies and two state-based marketplaces did not respond to this question.

bThe Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported that it does not use any optional data sources to identify changes in residency for the federally facilitated marketplace.

CMS Guidance Is Limited on Marketplaces’ Processes to Identify and Prevent Simultaneous Cross-State Health Care Coverage and Benefits

Marketplaces’ Processes to Identify Duplicate Cross-State APTC Benefits Are Limited

CMS does not specifically require marketplaces to identify individuals receiving APTC benefits outside of their states. Per the results of our 2024 survey, state-based marketplaces do not have processes to prevent duplicate APTC benefits by identifying individuals enrolled in a qualified health plan receiving APTC benefits outside of their state.[63]

CMS officials indicated that since 2014, the federally facilitated marketplace has conducted a monthly check, post-enrollment, to identify when consumers have duplicate cross-state qualified health plan enrollment through the federally facilitated marketplace. CMS officials told us they are developing a similar process to identify duplicate enrollments within state-based marketplaces. This report will include duplicate enrollments that exist between the federally facilitated and state-based marketplaces. Additionally, CMS officials indicated that they have distributed reports to states and plan to distribute enhanced regular reporting beginning in 2026.

Although CMS indicated it has a monthly check to identify duplicate enrollment in the federally facilitated marketplace, we found approximately 5,600 individuals in fiscal year 2023 who appeared to have qualified health plan coverage for which they were receiving APTC benefits in more than one state within the federally facilitated marketplace. We provided CMS with a nongeneralizable sample of six different SSNs that we identified as associated with potentially improper APTC payments made to issuers on behalf of individuals with duplicate enrollments through the federally facilitated marketplace. Each SSN matched to multiple states and had APTC benefits paid on its behalf during the same time frame.

We provided CMS the list of the six SSNs to verify whether each SSN appearing in multiple states belonged to the same individual. CMS officials stated that though their data showed SSNs in multiple states, their system’s logic determined that each instance was a distinct individual due to data differences in additional fields, such as DOB, last name, or address. For example, based on CMS’s explanation, Katherine Johnson in California and Catherine Johnson in New York would be considered different people even if their SSN and DOB matched.

However, SSNs should be unique to individuals and according to marketplace regulations, individuals must reside in the marketplace service area to be eligible to enroll in a qualified health plan and have APTC benefits paid to issuers on their behalf.[64] Therefore, we disagree with CMS’s assessment that these instances were distinct individuals and view CMS’s system’s logic as a potential system issue that may overlook duplicate enrollments and lead to potential overpayments.[65] Further as our data analysis shows, at least $39.1 million in APTC payments were made on behalf of approximately 18,000 individuals simultaneously enrolled in marketplace coverage in more than one state. As previously mentioned, the federally facilitated marketplace relies on self-attestation and does not use additional data sources to help verify residencies of individuals. Additionally, most of the state-based marketplaces we surveyed reported that they rely exclusively on self-attestation as proof of residency requirements.

A leading practice in the Fraud Risk Framework is to conduct data matching to verify key information for eligibility determinations. Along with verifying initial eligibility, data matching can identify changes in key information that could affect continued eligibility in programs that provide ongoing benefits. While CMS conducts some data matching for the federally facilitated marketplace, it has not ensured that the process is sufficient to identify and prevent duplicate cross-state qualified health plan enrollment. Without CMS designing and documenting in policies and procedures a sufficient process, or modifying its current one, there is an increased risk that APTCs will be improperly paid to multiple issuers on behalf of the same individuals. For example, such a process could include controls to detect and prevent duplicate SSNs from being used on multiple qualified health plans simultaneously.

In addition, duplicate SSNs that are the result of erroneous SSN data can also affect federal income tax compliance. As noted earlier, if applicants choose to have all or some of their premium tax credit paid in advance, they must reconcile the amount of APTC with the tax credit for which they ultimately qualified based on actual reported income and family size. According to IRS officials, IRS relies on the SSN data to identify taxpayers as part of the reconciliation process. If IRS does not receive valid SSNs from the marketplaces, the key back-end control intended by the tax reconciliation process will be hampered. If IRS is unable to reconcile APTC subsidies, its ability to recover overpayments of the tax credits is limited.

Marketplaces Do Not Have Processes to Identify Simultaneous Cross-State Medicaid and CHIP Coverage

Per our 2024 survey and discussions with CMS officials, both the federally facilitated and state-based marketplaces have processes to determine whether applicants are eligible for or enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP coverage within their respective states. Such coverage would exclude applicants from APTC eligibility.[66] For example, some states have integrated eligibility and enrollment systems for the marketplace, CHIP, and Medicaid agencies. These systems permit an automatic determination of eligibility for all these programs when an applicant first applies for coverage. According to CMS officials, the federally facilitated marketplace checks within the state for enrollment in minimum essential health coverage—such as Medicaid and CHIP—at initial application for a qualified health plan through the marketplace and twice yearly via the periodic data-matching process.

However, CMS and state-based marketplaces indicated that they do not have a process for the federally facilitated or state-based marketplaces, respectively, to identify individuals receiving Medicaid or CHIP coverage outside of the states in which individuals are enrolled in a qualified health plan. Further, per our 2024 survey results and discussions with CMS, none of the marketplaces, including the federally facilitated marketplace, submit qualified health plan enrollment data, including APTC information, to PARIS for interstate matching to help identify concurrent cross-state Medicaid or CHIP enrollment, which would make individuals ineligible for APTC. The surveyed state-based marketplaces reported that they do not submit information to PARIS for reasons such as limited resources and a lack of requirement to do so.

According to CMS officials, marketplaces can choose to use PARIS, but CMS has not made its use mandatory. CMS officials stated that APTC data in PARIS may not be compatible with the intent of PARIS because it is an advance payment of a federal tax credit, and PARIS is primarily used for public assistance programs. Additionally, CMS believes existing trusted and approved data sources, such as those available via the Hub, are a more cost-effective way to meet programmatic needs under current technology and resource constraints. However, the Hub does not include data to identify cross-state Medicaid or CHIP coverage.

In 2017, we recommended that CMS assess and document the feasibility of approaches for identifying individuals enrolled in the federally facilitated marketplace while simultaneously being enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP coverage in states outside of the states where they attest to residing.[67] In response, to close our recommendation, CMS performed a 2019 feasibility study of expanding its Hub data-matching process. CMS determined such an expansion of the process was not feasible due to (1) time needed to conduct such a cross-state match and (2) CMS’s belief that the Medicaid and CHIP enrollment match rate for consumers in states where they did not attest to residing would be no higher—and, more likely, much lower—than the current low match rate for within-state data matching.

Although CMS believes the cross-state matches would be lower than within-state matches, we found that $1.2 billion in potentially improper APTC payments were made to issuers on behalf of over 340,000 marketplace enrollees who also were enrolled in cross-state Medicaid or CHIP coverage for fiscal year 2023. While some of this could have been related to the continuous enrollment provision applicable to Medicaid and CHIP Medicaid expansion programs resulting from the pandemic, individuals enrolled in these programs should not also have had APTC payments made on their behalf, even under the revised rules during the pandemic. Additionally, the expansion of the Hub verification process may not be feasible for doing a cross-state match, but additional means of data matching, such as via PARIS or another data-matching system, could be used to identify and help prevent cross-state Medicaid or CHIP coverage.

Potential improper payments associated with duplicate coverage could be reduced with additional control activities. For example, requiring marketplaces to submit qualified health plan enrollment data, including APTC information, to the PARIS interstate match, or another data-matching system, would enable marketplaces to identify matches between APTC and CHIP or Medicaid and terminate benefits as appropriate.

Along with verifying initial eligibility, data matching can enable programs that provide ongoing benefits to identify changes in key information that could affect continued eligibility, such as residency. Without a requirement for all marketplace qualified health plan enrollment data, including APTC information, to be submitted to PARIS, or another data-matching system, for interstate matching on a frequently recurring basis, such as quarterly, marketplaces have limited ability to identify APTC beneficiaries simultaneously receiving cross-state Medicaid coverage, CHIP coverage, or APTC benefits. This can result in APTCs being improperly paid to issuers on behalf of individuals who may already be enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP in another state. It can also result in improper continuation of hundreds of millions in Medicaid or CHIP capitation payments being made to MCOs on behalf of individuals who have moved to different states.

CMS Guidance Is Limited on Submission of Medicaid or CHIP Enrollment Data to PARIS

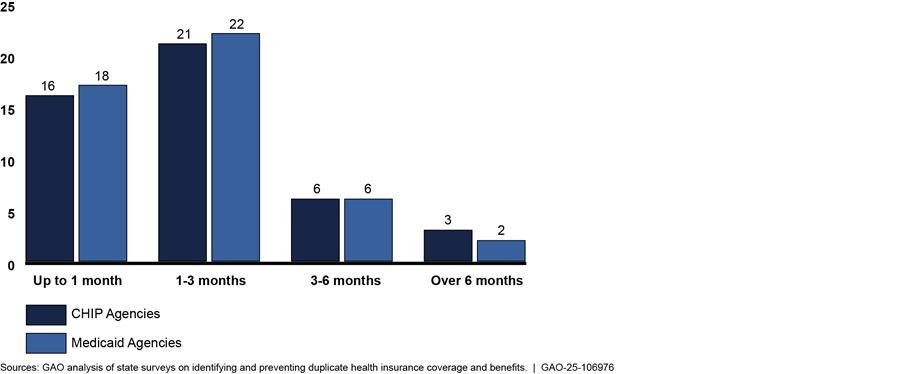

The results of our 2024 survey of state Medicaid and CHIP agencies indicated that all state Medicaid agencies and most state CHIP agencies submitted enrollment data for PARIS interstate matching during fiscal year 2023. However, the frequency of matching in fiscal year 2023, which was the focus of our analyses, varied among states for both Medicaid and CHIP.

Specifically, although most state agencies reported that they submitted Medicaid and CHIP enrollment data for all four quarters in fiscal year 2023, two state CHIP agencies and three state Medicaid agencies reported that they did not submit enrollment data for at least one quarter in fiscal year 2023. Of our six selected states, all six reported submitting Medicaid enrollment data for all four quarters. Of the six, five reported submitting CHIP enrollment data for all four quarters, and one state reported it does not use the PARIS match for its CHIP program.

In their survey responses, states reported that they did not submit Medicaid or CHIP enrollment data for each available PARIS interstate match due to submission barriers, such as limited resources, technical difficulties, and a lack of a requirement to do so. Without all state program enrollment data consistently being included in the PARIS interstate match, match results provided to the state agencies may not have sufficient information to identify duplicate cross-state Medicaid or CHIP enrollment and take appropriate action to prevent improper payments. Table 4 provides the frequency of data submissions for PARIS matching in fiscal year 2023.

Table 4: Survey Results of State Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Agencies’ Public Assistance Reporting Information System (PARIS) Submission

|

|

Reported having a process to submit enrollment data to PARIS |

Reported submitting enrollment data for all four quarters in fiscal year (FY) 2023 |

Reported submitting enrollment data at least once during FY 2023 (but not for all four quarters) |

Did not report submitting enrollment data for any quarter in FY 2023 |

|

State Medicaid agencies |

50a |

46 |

3 |

0 |

|

State CHIP agencies |

48b |

43 |

2 |

2 |

Source: GAO analysis of state surveys on identifying and preventing duplicate health care coverage and benefits. | GAO‑25‑106976

Note: We received a total of 50 submissions for the Medicaid and CHIP surveys (49 states and the District of Columbia). One state did not complete the Medicaid or CHIP survey. According to federal regulations, all state Medicaid eligibility determination systems must conduct data matching through PARIS; however, there is not a similar requirement for state CHIP agencies. Federal regulations for Medicaid agencies do not include PARIS reporting requirements that specify how frequently states are to submit enrollment data for the PARIS interstate match such as during each available PARIS quarterly service match.

aAlthough 50 state Medicaid agencies indicated that they have a process to submit Medicaid enrollment data to PARIS, one state did not indicate the quarters in fiscal year 2023 for which it submitted data to PARIS.

bOne state CHIP agency did not respond, and one reported not having a process. Although 48 state CHIP agencies indicated that they have a process to submit CHIP enrollment data to PARIS, one state did not indicate the quarters in fiscal year 2023 for which it submitted data to PARIS.