CHILD NUTRITION PROGRAMS

USDA Could Enhance Its Management and Oversight of State Administrative Expense Funds

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106977. For more information, contact Kathryn A. Larin at larink@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106977, a report to congressional requesters

USDA Could Enhance Its Management and Oversight of State Administrative Expense Funds

Why GAO Did This Study

USDA’s child nutrition programs serve billion of meals annually to help ensure that children in low-income families have access to nutritious foods at schools and other settings. SAE funds are states’ primary source of federal funds to support administrative costs for five child nutrition programs. Congress appropriated about $492 million to USDA for SAE in fiscal year 2024. States must contribute a minimum amount to SAE funding each year, which totals to about $9 million.

GAO was asked to review issues related to the use of SAE funds for child nutrition programs. This report examines (1) recent trends in SAE funds states received and how they used the funds, (2) challenges selected states faced in using the funds and USDA’s efforts to address the challenges, and (3) the extent to which USDA monitors states’ use of the funds to achieve agency goals.

GAO analyzed data on SAE funding amounts from fiscal years 2019 through 2024. GAO interviewed officials from a non-generalizable sample of four states and conducted site visits to two of them. States were selected for variation in geographic location and SAE funding amounts, among other things. GAO also interviewed USDA officials and four nonprofit organizations that work on child nutrition issues.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations to USDA, including to identify changes that would help improve SAE allocations and processes, and to update its guidance on SAE requirements. USDA generally concurred with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

Each year, in accordance with a funding formula established in federal law, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) allocates State Administrative Expense (SAE) funds to states to support their administration of child nutrition programs, including the school meal programs. States primarily spend SAE funds on salaries of staff administering these programs and other expenses. SAE funding was generally stable during the period GAO analyzed, before increasing in fiscal year 2024. That increase was due to schools serving more meals and receiving a higher rate for meal reimbursements in fiscal year 2022, according to USDA. The number and rate of reimbursement for meals served in certain child nutrition programs from 2 years earlier are key inputs in the funding formula.

All four selected states identified challenges related to the SAE funding formula and managing spending restrictions, among others. Officials from all selected states said the SAE funding formula does not fully account for factors that may increase administrative costs, such as state demographics. For example, states with rural districts may need to spend more on travel and logistics to conduct required oversight. States also face challenges effectively spending SAE funds due to uncertainty regarding the total amount they will receive over the year and the short window to spend additional funds, according to officials from all selected states and three USDA regional offices. USDA has taken some steps to give states more flexibility and resources but has not fully addressed several of the identified challenges. By identifying changes that would help improve SAE allocations and processes, including regulatory or statutory options, USDA could better assist states in using SAE funds to administer child nutrition programs.

USDA monitors states’ use of SAE funds and compliance with grant requirements, but its oversight has gaps. For example, its main SAE instruction manual was last updated in 1988 and includes references to outdated policies and procedures. USDA officials said they have not updated the guidance because of several competing priorities, such as implementing a new federal program during the pandemic. Without updated SAE guidance, USDA may miss opportunities to assist states and ensure compliance with grant requirements.

Abbreviations

|

COVID-19 |

Coronavirus disease 2019 |

|

FMR |

financial management reviews |

|

FNS |

Food and Nutrition Service |

|

FTE |

full-time equivalent |

|

IT |

information technology |

|

ME |

management evaluations |

|

nTIG |

Non-Competitive Technology Innovation Grant |

|

SAE |

State Administrative Expense |

|

Summer EBT |

Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer Program for Children |

|

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 29, 2025

The Honorable Tim Walberg

Chairman

The Honorable Robert C. “Bobby” Scott

Ranking Member

Committee on Education and Workforce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Virginia Foxx

House of Representatives

In 2024, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported that 17.9 percent of households (6.5 million) with children under age 18 were food insecure at some time during 2023, which means that they faced difficulty at times providing enough food for all household members.[1] USDA’s eight child nutrition programs help ensure that children in low-income families do not go hungry and have access to nutritious foods at schools and in other settings.

The Child Nutrition Act of 1966, as amended, authorizes USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) to allocate State Administrative Expense (SAE) funds to state agencies that administer the following five child nutrition programs: (1) National School Lunch Program, (2) Special Milk Program, (3) School Breakfast Program, (4) Child and Adult Care Food Program, and (5) Food Distribution Program, also known as the USDA Foods in Schools program.[2] The largest three programs (the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs and Child and Adult Care Food Program) served nearly 9 billion meals in fiscal year 2023, supported by more than $26 billion in federal spending.[3]

Congress annually appropriates SAE funds to USDA, and FNS allocates most of these funds to more than 80 state agencies in 54 states and territories.[4] In fiscal year 2024, Congress appropriated about $492 million to USDA for allocation to state agencies. Federal law also requires states to contribute funding for the administration of these child nutrition programs.[5] FNS refers to this requirement as the state funding requirement.

You asked us to review issues related to the use of SAE funds to administer child nutrition programs. This report examines (1) trends in the amount of SAE funds that USDA made available to states in recent years and how states used the funds, (2) challenges selected states faced in using SAE funds, and the assistance USDA has provided to address these challenges, and (3) the extent to which USDA monitors states’ use of SAE funds to achieve agency goals.

For all objectives, we reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations, and agency documents including guidance, internal memoranda, and reports related to SAE policies and procedures. We interviewed FNS officials, including from all seven FNS regional offices. We also interviewed state agency child nutrition program officials from a non-generalizable sample of four states: California, Oklahoma, Virginia, and Wyoming. We selected these states because they provided variation in federal and state funding amounts for SAE, uses of SAE funds including for professional development activities, and the number of agencies and full-time equivalents that administer the child nutrition programs in each state. We also selected states in different FNS regions for geographic diversity. To obtain perspectives beyond our selected states, we also interviewed representatives from four nonprofit organizations that work on child nutrition issues and that could provide a range of perspectives on those issues.[6]

To examine recent trends in SAE funding and states’ use of these funds for our first objective, we analyzed FNS data on amounts provided to states and state funding requirement contributions, from fiscal years 2019 through 2024.[7] Additionally, we analyzed state agencies’ planned expenditures and activities from the 41 SAE plans FNS approved in fiscal year 2023, the most recently approved plans available at the time of our review.[8] We determined these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of describing general trends in SAE funding and uses by reviewing related documentation, interviewing knowledgeable FNS officials, and performing electronic data testing. We conducted site visits in two of our selected states (California and Oklahoma), where we observed in-person SAE-funded training for local nutrition personnel to obtain illustrative examples of states’ use of SAE funds.

For our second objective, we interviewed officials in our selected states about the challenges they faced using SAE funds to conduct required administrative activities. We also obtained their views on FNS guidance on SAE grant processes and requirements, among other topics. We compared the challenges our selected states identified against those identified in a 2020 FNS study commissioned to examine the effectiveness of the SAE funding formula.[9] We assessed the extent to which FNS has taken steps to address the challenges our selected states identified, such as issuing or revising guidance and regulations since 2020, and obtained selected states’ perspectives on those actions.

For our third objective examining the extent to which USDA monitors states’ use of SAE funds to achieve agency goals, we analyzed compliance reviews that FNS conducted. Specifically, we analyzed management evaluations FNS conducted during fiscal year 2023 that assessed how state agencies used SAE funds. We also analyzed financial management reviews FNS conducted in our four selected states from fiscal years 2019 through 2023. For the management evaluations and financial management reviews, we identified findings and observations related to the use of SAE funds and determined the status of any required corrective actions.

We assessed the extent to which FNS’s seven regional offices ensured that state agencies submitted timely responses on their planned corrective actions, in accordance with FNS’s guidance. We also assessed the time frames within which states took action to address compliance findings and the regional offices validated those actions. We compared FNS’s guidance and monitoring efforts with federal internal control standards relevant to performing monitoring activities and addressing risks to achieving the program’s objectives.[10] We also assessed these efforts against FNS’s fiscal year 2024 priorities of ensuring its programs are implemented with integrity and improving program results and performance, which were in place when we conducted our work.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Background

The use of SAE funds is authorized under the Child Nutrition Act of 1966, as amended. Congress began appropriating these funds in 1969 to supplement state resources used to administer child nutrition programs. In addition to the five primary programs (the National School Lunch Program, Special Milk Program, School Breakfast Program, Child and Adult Care Food Program, and USDA Foods in Schools program), state agencies may use their SAE funds to support allowable costs related to administering the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program and Summer Food Service Program, according to FNS.[11] State agencies may also use their SAE funds to support Farm to School activities that help bring locally or regionally produced foods into school cafeterias, among other activities.[12] While SAE funds are the primary source of federal administrative funds for child nutrition programs, state agencies also receive separate funds from other federal sources to support administrative costs for the Summer Food Service Program and may retain a portion of the total funds they receive for administrative costs related to the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program.[13]

Since 1977, FNS has used a funding formula to annually allocate SAE funds to state agencies. Prior to calculating each state agency’s initial SAE allocation, the FNS National Office must determine the total amount of SAE funding available for allocation.[14] The SAE funding formula, which was last revised in the 1990s, consists of two types of funding: non-discretionary and discretionary.[15] According to FNS, each state agency’s initial SAE allocation is based on the programs it administers. If more than one state agency administers child nutrition programs in a state, FNS allocates SAE funding to the relevant state agency for each program.

According to FNS, non-discretionary funds are the largest component of the SAE funding formula. These funds are based on prior federal spending in each state for the school meal programs and Child and Adult Care Food Program, which reflects the number and rate of reimbursement for meals served from 2 years earlier. For the school meal programs, a state agency’s non-discretionary allocation cannot be less than $200,000, which is annually adjusted for inflation (currently about $203,500).[16] For the Child and Adult Care Food Program, a state agency’s non-discretionary allocation is calculated using a graduated formula, which means that as the program’s size increases, the funding level incrementally increases.[17] States also receive discretionary funds, a portion of which are distributed in equal amounts to states that administer specific programs, including the Child and Adult Care Food Program and USDA Foods in Schools program. The discretionary funds are also partially divided proportionally based on the number of meals the program served in each state, among other things.[18]

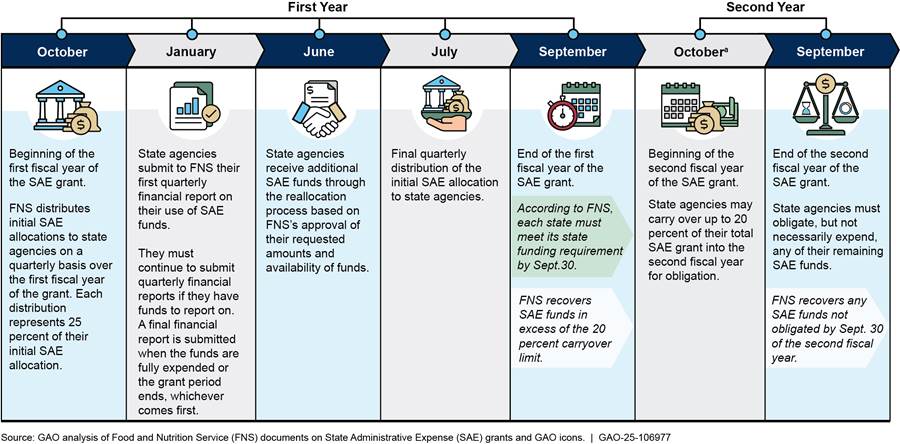

State agencies have 2 fiscal years to obligate their SAE funds for expenses that support the state-level administration of eligible child nutrition programs, including salaries of state officials (see fig.1). State agencies can carry over up to 20 percent of their total SAE allocation—initial allocation plus any reallocation and transfers funds—into a second fiscal year if they are not able to use all their funds in the first fiscal year.[19] In addition, state agencies must exclude SAE funds from state-imposed budget restrictions and limitations such as hiring freezes.[20]

· Reallocation funds. State agencies can request additional SAE funds above their initial SAE allocation each fiscal year through a process called reallocation.[21] SAE reallocation funds generally come from appropriated funds FNS did not initially allocate to state agencies, as well as funds that FNS recovered from state agencies at the end of the first grant year because they were not obligated or expended during the fiscal year, according to FNS.

· Transfer funds. A state agency may transfer SAE funds to another agency within the same state that is eligible to receive SAE funds when the agency has excess funds.

aEach October, state agencies receive another SAE grant for the new fiscal year.

State agencies are statutorily required to submit an initial SAE plan to FNS for approval and amend their plans when substantive changes occur related to their planned use of SAE funds.[22] FNS requires each state agency’s SAE plan include a budget and description of activities to document how it plans to use its SAE funds.

Administrative Funding Has Generally Been Stable, and

States Use These Funds to Pay for Staff and Other Expenses

Administrative Funding Has Generally Been Stable, and

States Use These Funds to Pay for Staff and Other Expenses

SAE Allocations Have Been Stable

Since 2019, Except for Pandemic-Related Increases

SAE Allocations Have Been Stable

Since 2019, Except for Pandemic-Related Increases

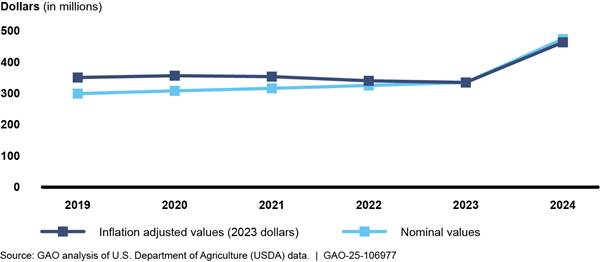

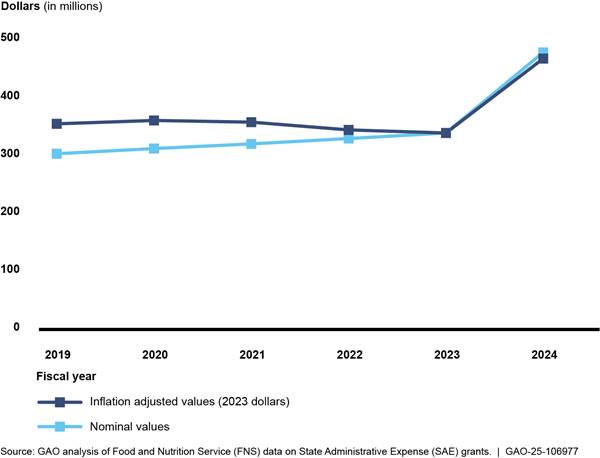

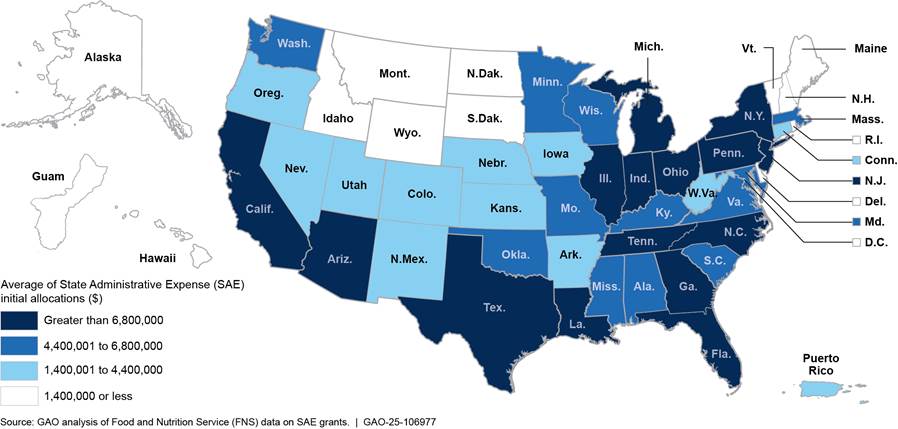

Total initial SAE allocation amounts from FNS were generally stable from fiscal years 2019 through 2023, before increasing in fiscal year 2024 (see fig. 2).[23] Funding remained stable during most of this period because FNS used program activity data from before the COVID-19 pandemic to calculate states’ allocations in fiscal years 2022 and 2023.[24] This helped ensure states’ funding did not significantly decrease due to changes in how they served meals during the first 2 years of the pandemic.[25] As previously noted, federal program spending in each state, which largely reflects the number and rate of reimbursement for meals served in certain child nutrition programs from 2 years earlier, is a key input to the SAE funding formula. Funding grew by about 30 percent in fiscal year 2024 in response to increased program spending in fiscal year 2022, which was due to schools serving more meals and receiving a higher rate of reimbursement for them, according to FNS.[26]

According to FNS officials, total initial SAE allocations declined in fiscal year 2025, because the number of meals and rate of reimbursement returned to pre-pandemic levels. Specifically, FNS officials said they made available about $373 million in fiscal year 2025 for initial SAE allocations, which is $101 million less than the amount available in fiscal year 2024.[27]

Federal SAE allocation amounts are significantly larger than states’ required funding contributions, which have remained constant since 1977. The statute does not include a provision to adjust these amounts for inflation.[28] Annually, states’ collective required funding contributions of about $9 million equate to an average of about $173,000 per state, according to our analysis of FNS’s data on states’ required contributions.[29] Connecticut has the lowest required contribution (about $25,000) and its federal initial SAE allocation for fiscal year 2024 was about 176 times the size of its required share. Louisiana has the highest required contribution (about $759,000) and its federal initial SAE allocation amount for fiscal year 2024 was about 13 times its required share. According to FNS national officials, regional offices are responsible for ensuring that states meet the funding requirement and do not currently track the extent to which states are providing additional funding to support the administration of these programs.[30]

SAE Funds Available for

Reallocation Have Declined Since Fiscal Year 2023

SAE Funds Available for

Reallocation Have Declined Since Fiscal Year 2023

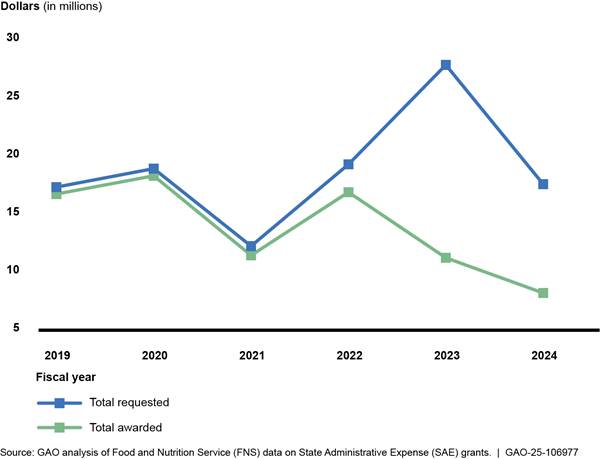

Many state agencies request reallocation funds each year, but recently FNS has been unable to provide all the funds requested. Specifically, state agencies each requested an average of about $521,000 annually from fiscal years 2019 through 2024.[31] FNS was generally able to provide most of the additional funding that state agencies requested until fiscal year 2023. Since then, FNS has been unable to fund more than half of the total amount requested because the total amount requested exceeded the funds available.

|

SAE Reallocation Funding Process Every spring, state agencies can request additional State Administrative Expense (SAE) funds through the reallocation process. These funds may be used for any allowable SAE expenses. However, each year, FNS prioritizes certain types of expenses when awarding reallocation funds. Timeline: March: State agencies submit a form to FNS regional offices with their requested amount and descriptions of planned expenses for the additional funds. All four selected states in our review requested reallocation funds from fiscal years 2019 through 2024 to pay for things like IT, professional development activities, staff salaries, and storage and distribution for the USDA Foods in Schools program. April – May: FNS notifies state agencies of their reallocations based on regional offices’ recommendations and available funds. In some cases, FNS provides information on other federal grants that may cover unmet funding needs like the Non-Competitive Technology Innovation Grant. April – September: State agencies must obligate (not necessarily expend) reallocation funds by the end of the fiscal year. Source: GAO analysis of Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) documents. | GAO‑25‑106977 |

As shown in figure 3, total requested amounts have generally grown since fiscal year 2019, but sharply declined in fiscal year 2024 when state agencies received larger initial SAE allocation amounts.[32]

At grant closeout, FNS recovered an average of about $232,000 per state agency of unused SAE funds from fiscal years 2019 through 2022, according to the most recent available data at the time of our review.[33] These recovered funds included obligated funds that state agencies were unable to spend by grant closeout. While the trend in the total amount recovered has varied, FNS generally recovered funds from fewer state agencies over this period. For example, FNS recovered funds from 28 state agencies in fiscal year 2022, compared to 36 state agencies in fiscal year 2019.[34] In fiscal year 2023, FNS updated SAE regulations to give state agencies an additional 120 days to spend SAE funds that were obligated by grant closeout. This regulatory change may help reduce the amount of unused SAE funds FNS recovers from state agencies in subsequent fiscal years.

State Agencies Primarily Use SAE

Funds for Staffing and “Other” Expenses

State Agencies Primarily Use SAE

Funds for Staffing and “Other” Expenses

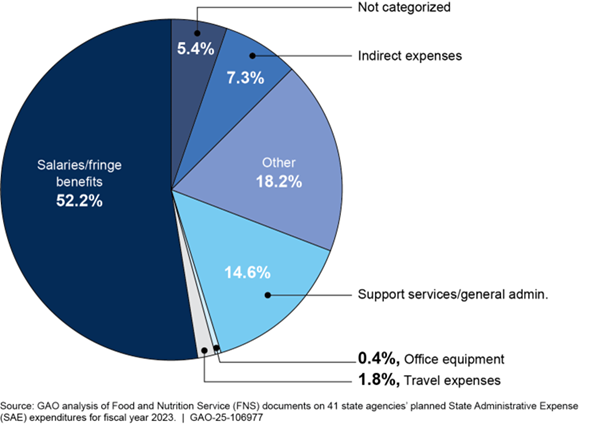

State agencies primarily spend SAE funds on salaries of staff administering their child nutrition programs and “other” expenses, including IT. Staff salaries and benefits (52 percent) and “other” (18 percent) were the top two budget categories (see fig. 4), based on our analysis of the 41 state agency SAE plans that FNS approved in fiscal year 2023.

Note: Figure values do not sum to 100 percent due to rounding. State agencies can vary in how they name budget categories in their SAE plans. In those instances, we identified the corresponding budget category from budget categories described in FNS National Office guidance on developing SAE plans, last updated in fiscal year 1997. The FNS National Office relies on the regional offices to help ensure that state agencies consistently report allowable costs in their SAE plans in accordance with 2 C.F.R. pt. 200.

Staff Salaries and Benefits

The 41 state agencies in our review planned to use SAE funds to pay for the salaries and benefits of more than 1,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff, in total, in fiscal year 2023.[35] For example, the Wyoming Department of Education expected to pay for about four FTEs with its SAE funds. Most of these FTEs would help local staff implement their child nutrition programs through trainings on program policies and would oversee local staff through administrative reviews, according to the plan.

“Other” Expenses

The “other” category of spending included a wide range of administrative expenses, including IT expenses such as computers, data processing systems, and contracts for software maintenance. For example, the Virginia Department of Health planned to spend about one-third of its “other” budget to contract with an external vendor to maintain software that helps process meal reimbursement claims and participation data, according to the agency’s plan. Although all seven FNS regional offices told us that IT systems are a primary expense, we were unable to calculate the overall planned spending for these systems because they were not itemized and reported in a single budget category.

Professional Development Expenses

Although not reported in a single budget category, 39 of the 41 state agencies also included planned activities for professional development, according to our review of their most recent SAE plans.[36]

· Conferences and other professional development opportunities for state-level staff. To support the professional development of state child nutrition staff, about half of state agencies (21) planned to spend SAE funds on conferences and professional memberships, and some (9) planned other professional development activities. For example, officials with the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services said they planned to attend the 2023 Virginia School Nutrition Association Conference to share program policy updates with school nutrition staff and host an exhibit on products available through the USDA Foods in Schools program that can be served in school meals.

· Required trainings for local child nutrition staff. Nearly all (38) state agencies indicated that SAE funds would cover training costs for local child nutrition staff, such as contracts with external organizations to deliver online trainings.

· Culinary trainings for local child nutrition staff. Nine state agencies included culinary trainings for local nutrition staff and six of these agencies planned to partner with external organizations to provide them.

|

Culinary Trainings Two Selected States Administer Using SAE Funds · Oklahoma Department of Education Cooking for Kids, led by professional chefs, is a training program for local nutrition staff who prepare meals served in schools and other settings. The state agency, in partnership with Oklahoma State University, administers this program using SAE funds. In summer 2024, this program scheduled 14 sessions of a 2-day, in-person training on knife skills, food safety, and other culinary skills across the state, according to agency officials. · Virginia Department of Education The state agency’s nutrition staff manage the Virginia Food for Virginia Kids program. Staff salaries are paid using SAE funds, and program activities are funded by other FNS nutrition grants. This program builds the capacity of Virginia schools to increase scratch cooking and serve more fresh, local, and student-inspired meals. The state agency partners with professional chefs to operate this program and has trained three cohorts of eight school food authorities each since 2022. Sources: GAO image of a culinary training conducted by Oklahoma; interviews with Oklahoma and Virginia agency officials; and GAO review of documents reporting planned State Administrative Expense (SAE) expenditures to the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS). | GAO‑25‑106977 |

FNS Has Not Fully Considered Options to Address States’

Challenges and Improve the SAE Funding Process

FNS Has Not Fully Considered Options to Address States’

Challenges and Improve the SAE Funding Process

Selected States Identified

Challenges Related to the Funding Formula, Prioritizing Spending, and Spending

Restrictions

Selected States Identified

Challenges Related to the Funding Formula, Prioritizing Spending, and Spending

Restrictions

Officials from the four selected states in our review identified various challenges they face in administering child nutrition programs with SAE funds. The challenges include those related to the funding formula for SAE allocations, needing to prioritize spending on essential activities, and managing spending restrictions. These challenges were also identified by FNS regional offices, nonprofit organizations that work on child nutrition issues, and a 2020 study completed for FNS.[37]

SAE Funding Formula

Officials from all four selected states and all four nonprofit organizations said the SAE funding formula FNS uses to calculate each state agency’s initial allocation does not fully account for factors that may affect their administrative costs. This is because the statutory formula is largely driven by the number and rate of reimbursement for meals served through certain child nutrition programs. Factors related to state demographics that may affect costs are not part of the formula. Further, other factors, such as costs specific to the USDA Foods in Schools program and the number of school food authorities in a state, are not part of the larger, non-discretionary component of the formula.[38] The 2020 FNS study identified similar state factors that may affect administrative costs and presented options for modifying the SAE funding formula to better account for these factors when FNS calculates each state agency’s initial allocation.

· State demographics. Officials from two of the four selected states said state demographics, such as population and geography, affect administrative costs. For example, according to officials from one state agency we interviewed, states with small populations receive less funding but may spend more per meal compared to states with larger populations. Additionally, states with rural districts may need to spend more on travel and logistics for activities such as administrative reviews. Officials from the other selected state said states with higher costs of living must allocate a greater portion of their SAE funds for staff salaries and benefits.

· Costs specific to the USDA Foods in Schools program. Officials from three of the four selected states said that the equipment and facilities needed for the USDA Foods in Schools program, such as trucks, trailers, and warehouse space, are expensive, and costs are increasing in their states.[39] For example, officials from one state agency said they operate two food distribution warehouses, and a recently renewed lease for one of those warehouses increased the rent by 300 percent. When expenses for the USDA Foods in Schools program cannot be fully covered by SAE funds, state agencies typically charge school food authorities fees to cover those costs. Further, some smaller state agencies relied on transfers from larger agencies to support the administration of this program.[40] For example, one small agency from a selected state received an annual transfer of SAE funds from a larger agency within the state that had excess SAE funds to help cover essential expenses for its USDA Foods in Schools program.

· Number of school food authorities. Officials from three of the four selected states explained that the number of school food authorities they oversee affects travel and personnel costs.[41] The number of school food authorities increases the workload for state agency staff who conduct administrative reviews and provide technical assistance and trainings to local nutrition staff. For example, officials from one state agency said they have one staff member to provide technical assistance to 361 schools, and that person must travel 500 miles to conduct oversight. As a result, officials said they do not have the capacity to provide adequate on-site technical assistance to local nutrition staff implementing the programs.

Prioritizing Spending

Officials from all four selected states and three of the four nonprofit organizations said state agencies must make tradeoffs with their initial allocations to cover essential administrative costs like technology, staffing, and professional development. In the 2020 FNS study, states also identified technology and staffing as major and growing budget categories.[42]

· Technology. All four selected states identified technology as a large cost category, and states faced challenges funding updates to their technology systems and other related expenses. To help states cover these costs, FNS has made additional funds available through the Non-Competitive Technology Innovation Grant (nTIG).[43] However, officials from one state agency said their nTIG funds did not cover the full cost of adding a new system for meal orders. Additionally, officials from another state agency told us recruiting IT staff is challenging because they cannot offer salaries that compete with the private sector.

· Staffing. All four selected states identified various staffing challenges, including having an insufficient number of individuals to complete the work or lacking the necessary expertise. For example, officials from one state agency said they must make tradeoffs on staff responsibilities to comply with program requirements. Such tradeoffs include staff providing less technical assistance to local nutrition staff to free up their time to perform required program oversight. Additionally, officials from another state agency told us staff have combined certain job functions like accounting and program administration.

· Professional development. Officials from three of the four selected states said they are judicious in deciding which professional development opportunities they attend and what resources are available to host trainings for local child nutrition staff because of competing funding priorities.

In addition, officials in all four selected states identified challenges related to covering additional administrative costs resulting from new federal requirements and policy initiatives, which the 2020 FNS study also found.[44] For example, state agencies said they must rely on current staff who are already balancing numerous administrative activities rather than hiring specialized staff members to implement new federal requirements. Officials from one state agency said they are not able to hire consultants to implement the new program integrity rules for the Child and Adult Care Food Program like larger states in their FNS region.[45]

After covering essential administrative costs, officials from all four selected states said they have minimal SAE funds left to improve program administration, such as pursuing more innovative uses of SAE funds. For example, officials from one state agency said they cannot offer innovative practices like culinary skills training or promoting the use of local foods in school meals, which could help improve implementation of their child nutrition programs. Officials from another state agency said they focus on essential administrative costs such as salaries first and special projects second.

Spending Restrictions

Officials from all four selected states, all four nonprofit organizations, and four of seven FNS regional offices described challenges with federal and state processes, and how they interact, which can restrict states’ ability to obligate and spend SAE funds. The 2020 FNS study also reported on states’ concerns regarding uncertainty about expected funding levels and shortened time frames for spending SAE reallocation funds.

· SAE initial allocation funds. Prior to fiscal year 2023, SAE initial allocation funds had to be obligated and spent by the end of the second grant year, which created a short timeline for state agencies to fully use these funds. In 2023, FNS amended its regulations to allow states to obligate, but not necessarily spend, funds by the end of the second grant year. Officials from one of the selected state agencies said their agency is typically delayed in obligating their initial SAE allocation, however, because the state legislature and agency leadership must authorize the obligation of federal funds, including SAE funds.

Additionally, officials from three of the seven FNS regional offices said their states face challenges effectively budgeting their initial SAE allocation funds because they are uncertain about the total amount they will receive each year. For example, officials from a selected state agency said that the agency has developed its own tool to estimate the amount it will receive from the non-discretionary portion of the formula. However, officials said the state agency still struggles to estimate the discretionary portion because it is complex and based on factors that are unknown to state agencies. To help address this uncertainty, in fiscal year 2024, FNS provided state agencies the projected change in their SAE allocations for fiscal year 2025. FNS officials said state agencies should be able to estimate their SAE funding amount without such projections from FNS in subsequent years because annual SAE funding levels have generally been consistent.

· SAE reallocation funds. Officials from a selected state agency said they face similar challenges spending reallocation funds. The state agency is unable to obligate reallocation funds until it receives the necessary approval from the state legislature, which creates delays in using these funds. Overall, SAE reallocation funds have less utility than initial allocations due to variability in the amount of funds that are made available each year for reallocation, according to officials from three of the seven FNS regional offices. FNS amended its guidance in 2020 to allow state agencies to use reallocation funds for any allowable expense, such as salaries. But officials from one state agency said they were reluctant to use SAE reallocation funds for salaries because there was no guarantee the agency would ultimately receive those funds.

· Carryover. Officials from two selected states said the 20-percent carryover limit for SAE funds can hinder a state agency’s ability to manage its funds over the 2-year grant period. Previously, state agencies were only permitted to carry over funds from their initial SAE allocation. While FNS updated its regulations in 2020 to allow state agencies to carry over 20 percent of their total SAE allocation (including reallocation funds) into the second grant year, officials from two selected state agencies said this change did not fully address their challenges. Specifically, they cited challenges related to needing to secure state approval to obligate SAE funds, as discussed previously, and other factors that make it difficult to obligate at least 80 percent of their initial allocation in the first year of the grant period.

FNS Has Taken Steps to Give

States More Flexibility and Resources but Has Not Fully Addressed Challenges

FNS Has Taken Steps to Give

States More Flexibility and Resources but Has Not Fully Addressed Challenges

As previously discussed, FNS has taken action to provide states additional flexibilities for using SAE funds and new federal grants to help support IT costs. However, we have identified several challenges that FNS has not fully addressed, including those related to the SAE formula not fully accounting for administrative costs, SAE reallocation funds, and SAE carryover restrictions (see table 1).

Table 1: Actions FNS Has Taken to Address Challenges Identified by Selected States, a Prior Study, and Stakeholders Related to Using SAE Funds

|

Challenge |

Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) actions to address challenge |

|

SAE initial allocations do not fully account for factors that influence administrative costs, such as state demographics. |

FNS commissioned a study in 2020 to assess the State Administrative Expense (SAE) funding formula. However, since this study, FNS officials told us they have not further evaluated options to modify the SAE funding formula because existing statutory provisions limit the options the agency can implement without congressional action. |

|

States’ limited SAE allocations often require them to prioritize essential administrative costs, including technology, over other expenses. |

FNS established additional federal grants, such as the Non-Competitive Technology Innovation Grant in 2020, but two selected state agencies described ongoing challenges related to covering these costs. |

|

Prior to fiscal year 2023, SAE initial allocations had to be obligated and spent by the end of the second grant year and some states were unable to estimate available funding. |

In 2023, FNS updated its regulations to require that state agencies obligate, not necessarily spend, SAE initial allocations by the end of the second grant year. In fiscal year 2024, FNS provided state agencies projected changes in their SAE allocations for the following fiscal year. Going forward, the agency noted that state agencies should be able to estimate their own SAE funding amount, as it will be relatively similar to the amount received in previous years. |

|

SAE reallocation funds have less utility than initial allocations due to variability in additional funding available and a shorter window to obligate and spend funds. |

In 2020, FNS amended its guidance to no longer require that SAE reallocation funds be prioritized for special one-time projects. However, all four selected states said they continued to experience challenges using reallocation funds because of variability in the amount of funding available each year. |

|

The amount that state agencies can carry over makes it difficult to manage SAE funds over the 2-year grant period. |

In 2020, FNS updated its regulations to allow state agencies to carry over 20 percent of their total SAE allocation into the second grant year. However, two selected state agencies described ongoing challenges related to obligating at least 80 percent of their initial allocation by the end of the grant period. |

Source: GAO analysis of FNS information and interviews with officials from four selected states and representatives from four nonprofit organizations. | GAO‑25‑106977

FNS’s fiscal year 2024 priorities include improving results and program performance through a culture of innovation, process analysis, and improvement. While FNS officials told us the SAE allocation process is complex and any changes would require the agency to carefully consider how any changes would affect all states, the agency has not identified whether further actions—including regulatory or statutory options—to change SAE allocations and processes would be beneficial for states. Without fully considering potential changes to improve SAE allocations and processes, state agencies may continue to experience challenges related to the use of SAE funds and administering their child nutrition programs, particularly as pandemic-related funding increases phase out.

FNS Monitors States’ Use of SAE Funds but States Have Not

Fully Addressed Some Compliance Findings and Guidance Remains Outdated

FNS Monitors States’ Use of SAE Funds but States Have Not

Fully Addressed Some Compliance Findings and Guidance Remains Outdated

FNS Monitoring Efforts Identified

Issues with States Updating SAE Plans as Required

FNS Monitoring Efforts Identified

Issues with States Updating SAE Plans as Required

FNS regional offices monitor how states use SAE funds in accordance with federal laws and regulations as part of their annual oversight process by conducting management evaluations (ME) and financial management reviews (FMR) of a selection of states each year. According to FNS officials, regional offices use a risk-based approach that considers factors such as time elapsed since the last review and overall meals served to prioritize their selections. While FNS’s National ME and FMR Guidance requires regional offices to conduct these reviews of child nutrition programs at least once every 5 years, agency officials explained that regions may conduct these reviews every 3 to 4 years (see sidebar).

|

Two FNS Compliance Reviews Monitor States’ Use of State SAE Funds · The agency’s Management Evaluation (ME) review guide includes a State Administrative Expense (SAE) funds module. This module assesses a state agency’s compliance in the following three areas: SAE plan and budget, SAE funds utilization, and SAE reallocation. · The Financial Management Review (FMR) review guide includes two modules to assess state agencies’ reporting and use of SAE funds. The first module assesses the extent to which the state agency completed its required financial status reports, including the FNS-777 SAE. The second module assesses if the state agency has (1) records to support allowable costs, (2) met the state funding requirement, and (3) complied with SAE carryover requirements. Source: Food Nutrition Service’s (FNS) Fiscal Year 2023 National ME and FMR Guidance. | GAO‑25‑106977 |

For MEs, the most common SAE-related finding in fiscal year 2023 was that state agencies did not submit an amended SAE plan to FNS for approval as required.[46] Specifically, FNS regional offices issued MEs to 20 state agencies that year, and eight of those agencies did not submit a plan when there was a substantial change from the most recently approved plan.[47] As a result, the eight state agencies were issued a finding related to not submitting an amended SAE plan reflecting the most current budget, activities, programs, and staffing levels. As of November 2024, seven of the eight state agencies had submitted an amended SAE plan as required and their findings were closed.[48] We also analyzed FMRs conducted in three of the four selected states from fiscal years 2019 through 2023; these reviews identified a range of findings related to SAE funds (see sidebar). See appendix II for a summary of MEs and FMRs we reviewed.

|

Financial Management Reviews (FMR) in Selected States · From fiscal years 2019 through 2023, three of the four selected states (California, Virginia, Wyoming) had FMRs conducted for their child nutrition programs. · Each of these FMRs resulted in at least one State Administrative Expense-related finding, nearly all of which were closed at the time of our review. · These findings ranged from untimely submissions of quarterly financial reports to deficiencies in procedures to ensure compliance with federal procurement requirements. Source: GAO analysis of FMRs that Food and Nutrition Service conducted in selected states. | GAO‑25‑106977 |

FNS regional offices vary in how they ensure state agencies submit amended SAE plans for approval when substantial changes occur. FNS officials said that, while the regional offices encourage state agencies to submit SAE plans annually, they rely on MEs and the SAE reallocation process to monitor the accuracy of SAE plans. The Mid-Atlantic Regional Office is the only regional office that requires state agencies to annually submit SAE plans for approval, according to FNS. This prevents the regional office from having to assess whether the states’ plans are up to date as part of an ME, according to FNS national officials, and allows regional office staff to annually communicate any expectations they have about a state agency’s planned SAE expenses. Officials from two of the seven regional offices said requiring state agencies to annually submit SAE plans for approval would help improve their oversight of SAE funds. Previously, state agencies were required to submit annual plans to FNS for approval, but Congress revised this requirement in 1996.[49]

FNS’s fiscal year 2024 priorities include ensuring its programs are implemented with integrity and improving program results and performance. FNS national officials said they rely on the regional offices to develop procedures to help ensure state agencies update their SAE plans as required. However, as noted previously, regional offices vary in their requirements for state agencies to submit SAE plans and recent compliance findings indicated that states have not always submitted updated plans when required. By better communicating its expectations for submitting SAE plans, or working with Congress to consider whether the frequency with which the plans are submitted needs to be revised, FNS would have greater assurance that approved plans reflect state agencies’ current plans and activities and thus, improve oversight.

Half of Compliance Reports Had

Findings That Remained Open for at Least a Year

Half of Compliance Reports Had

Findings That Remained Open for at Least a Year

We found that state agencies did not provide timely corrective action responses to regional offices in 40 percent (eight) of the 20 MEs and FMRs issued that assessed the use of SAE funds and had open findings as of October 2024.[50] FNS’s National ME and FMR guidance establishes procedures for monitoring and tracking corrective action responses. According to this guidance, state agencies must submit a corrective action response for each finding within 60 days of the report date and regional offices must update the status of corrective actions at least monthly in the system of record and include relevant documentation.[51]

In addition, we found that 11 of the 20 reports had findings that remained open for at least 1 year. The length of time findings remained open ranged from 1 year in three FNS regions to 7 years in one FNS region. Regional offices are primarily responsible for determining if a state agency’s time frames for taking corrective action are reasonable. However, there is no minimum time frame or goal for regional offices to validate that a state agency has taken corrective action to close an open finding, according to FNS’s guidance. According to FNS national officials, there is no minimum time frame because milestones are specific to the circumstances of each finding. For example, some findings may require changes to state procurement rules or changes to state accounting systems. In addition, there may be extenuating circumstances that impact state agencies’ ability to implement corrective actions in a timely manner, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to FNS national officials, regional offices provide technical assistance to help state agencies address extenuating circumstances. In addition, the FNS National Office can provide policy clarifications or help regional offices provide technical assistance to state agencies on complex policy issues. Finally, to encourage timely follow-up on findings, the FNS National Office provides regional offices with a monthly report of open findings that have not been updated in the system of record within the last year.

As part of its quality assurance efforts for MEs and FMRs, the FNS National Office also identified issues with the extent to which regional offices were monitoring state agencies’ corrective action responses and remediating open findings.[52] Of the seven regional offices reviewed during fiscal year 2023, five did not always adequately monitor state agencies’ corrective action responses or fully document related follow-up actions in the system of record, according to the MEs and FMRs that FNS selected for quality assurance review. This review represented 10 FNS program areas, including the child nutrition programs.[53] Each regional office is responsible for taking corrective action on the findings that result from the quality assurance review.

FNS’s fiscal year’s 2024 priorities include ensuring its programs are implemented with integrity and improving program results and performance. Federal internal control standards also require agencies to remediate monitoring deficiencies in a timely manner.[54] Although FNS officials noted that there may be reasons outside of regional offices’ control that findings remain open for longer periods, we have highlighted strategies in our past work that agencies can use when faced with such a challenge. These strategies include using data on external factors to adjust for their effect on the goal or setting different goals for different populations for which the agency has different expectations.[55] For example, FNS could set a goal or target for state agencies to complete follow-up actions on a certain percentage of findings, and for regional offices to validate those actions, within a specified time frame (e.g., a year). Without establishing goals or other targets that help ensure state agencies are taking corrective action in a timely manner, FNS cannot be sure that its compliance reviews will improve results and program performance.

FNS Has Not Updated SAE Guidance

FNS Has Not Updated SAE Guidance

Two key FNS guidance documents related to SAE funds have been in place for about 30 years or more. First, FNS’s primary SAE guidance—an instruction manual last updated in 1988—outlines basic guidelines for SAE funds, including allowable costs, but refers to outdated policies and procedures. For example, this manual refers to a form that states no longer use to report on the status of their SAE funds.[56] Second, FNS has additional guidance on developing SAE plans, including a suggested template with fields to describe budget and activity categories for states to use, that was last updated in fiscal year 1997.

As a result of outdated SAE guidance, we found that state agencies may not be consistently reporting certain costs in their SAE plans in accordance with the current cost principles for federal awards.[57] In the 41 recently approved SAE plans we reviewed, state agencies used different cost categories to report IT-related costs, including “other” and “support services/general administration,” which are cost categories provided in FNS’s 1997 guidance.[58] FNS national officials said they rely on the regional offices to help ensure state agencies consistently report all allowable SAE costs in accordance with federal regulations when developing their SAE plans.

FNS officials acknowledged that SAE guidance requires some updates. FNS circulated draft guidance in 2019 that updated its SAE plan guidance and template to regional offices for feedback.[59] However, FNS officials said the agency ultimately did not finalize updates to its SAE guidance and cited several competing priorities, including becoming responsible for the implementation of non-congregate meals and Summer EBT during the pandemic.[60]

Officials from one FNS regional office said new SAE guidance and standardized templates would be extremely helpful when providing technical assistance to state agencies and reviewing SAE plans for approval. Officials in two of the four selected states also agreed that it would be helpful for FNS to update its SAE plan guidance such as developing a standardized spreadsheet-based template and providing current guidance on budget requirements. In one selected state, officials worked with their FNS regional office to modify various cost categories in the SAE plan template that FNS provides to ensure their reported information is accurate.

FNS’s fiscal year 2024 priorities include ensuring its programs are implemented with integrity and improving program results and performance. Without updated SAE guidance, FNS cannot ensure its regional offices are consistently assisting state agencies with SAE grant reporting requirements, which can create challenges for states trying to meet those requirements.

Conclusions

Conclusions

The Child Nutrition Act of 1966, as amended, authorized FNS to provide SAE funds to states for child nutrition programs. The amount of funding allocated to each state agency is based on the SAE funding formula, which was last revised in the 1990s. Current trends and challenges identified by state agencies suggest that, overall, states are not able to use their SAE funds effectively for various reasons. Given that federal SAE funding is more limited in fiscal year 2025 as pandemic-related funding increases have phased out, it is important that FNS review how it can improve the effectiveness of SAE allocations and processes and determine whether changes are warranted.

In addition, while states are required to submit SAE plans to FNS for approval when substantial changes occur, eight of the 20 state agencies that received MEs during fiscal year 2023 did not do so. As a result, FNS lacks assurance that states’ SAE plans reflect their current plans and activities. This lack of visibility over states’ use of SAE funds makes it difficult for FNS regional offices to identify in a timely manner, for example, the types of expenses that are increasing or changing over time and help states address any challenges.

Further, FNS relies on its compliance reviews to monitor states’ use of SAE funds retrospectively and requires states to address findings that result from these reviews. Yet, FNS has not established an expected goal or target for states to take corrective action within a specified time frame. In addition, given variation across regional offices in the timeliness of their follow-up activities, some states may continue to be slow and uneven in taking corrective actions. Additional efforts to improve the timeliness of these activities could help FNS ensure its compliance reviews improve results and program performance.

Finally, officials from two of the four selected states and others have expressed concerns about outdated SAE guidance. While FNS has acknowledged that updating this guidance has been overtaken by other priorities within the agency, additional efforts could help increase FNS’s assurance that regional offices are consistently assisting state agencies with SAE grant reporting requirements.

Recommendations

Recommendations

We are making the following four recommendations to USDA:

The Secretary of Agriculture should direct the Food and Nutrition Service to identify changes that would help improve SAE allocations and processes and determine how it could implement those changes, including by pursuing any regulatory changes or requesting any necessary statutory authority. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Agriculture should direct the Food and Nutrition Service to identify specific steps it can take to help ensure the agency has current information on states’ planned budgets and activities for using SAE funds, such as better communicating expectations for submission of SAE plans or working with Congress to consider whether the frequency with which these are submitted needs to be revised. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Agriculture should ensure the Food and Nutrition Service establishes timeliness goals or other targets to ensure states take corrective action on SAE compliance review findings in a timely manner. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Agriculture should ensure the Food and Nutrition Service updates its SAE guidance to reflect current SAE grant requirements and is useful to state agency personnel responsible for compliance. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to USDA for review and comment. USDA provided comments by email stating that the agency generally concurs with all four recommendations and observing that the recommendations align with the agency’s guiding principles and priorities of executing programs with integrity and accountability. USDA plans to provide more detailed responses on its actions to address the recommendations within 180 days. In particular, USDA noted that efforts are already underway to address the first recommendation, including reviewing and taking actions consistent with the 2020 study the agency commissioned to assess the SAE funding formula and present a series of options to potentially improve SAE allocations and procedures. USDA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committee, the Secretary of the Agriculture, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at larink@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Kathryn A. Larin, Director

Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues

|

State |

State funding requirementa |

Initial SAE allocation, fiscal year 2024 (nominal dollars) |

Ratio of state’s initial SAE allocation, fiscal year 2024, to state funding requirementb |

||

|

Nominal amount (1977 dollars) |

Inflation adjusted amount (2023 dollars) |

Ratio using nominal amounts |

Ratio using inflation adjusted amounts |

||

|

AK |

44,590 |

176,631 |

1,205,525 |

27.0 |

6.8 |

|

AL |

134,390 |

532,350 |

8,255,948 |

61.4 |

15.5 |

|

AR |

181,340 |

718,330 |

5,321,679 |

29.3 |

7.4 |

|

AZ |

84,965 |

336,566 |

9,547,678 |

112.4 |

28.4 |

|

CA |

666,272 |

2,639,258 |

54,960,918 |

82.5 |

20.8 |

|

CO |

65,732 |

260,380 |

5,905,983 |

89.8 |

22.7 |

|

CT |

25,138 |

99,577 |

4,432,545 |

176.3 |

44.5 |

|

DC |

108,345 |

429,180 |

2,176,209 |

20.1 |

5.1 |

|

DE |

169,911 |

673,057 |

1,730,029 |

10.2 |

2.6 |

|

FL |

133,394 |

528,405 |

30,108,671 |

225.7 |

57.0 |

|

GA |

275,423 |

1,091,014 |

18,158,089 |

65.9 |

16.6 |

|

GU |

86,424 |

342,346 |

400,822 |

4.6 |

1.2 |

|

HI |

185,843 |

736,167 |

1,440,193 |

7.7 |

2.0 |

|

IA |

148,914 |

589,883 |

5,157,318 |

34.6 |

8.7 |

|

ID |

54,969 |

217,745 |

2,055,304 |

37.4 |

9.4 |

|

IL |

221,414 |

877,072 |

15,825,352 |

71.5 |

18.0 |

|

IN |

279,609 |

1,107,596 |

9,855,410 |

35.2 |

8.9 |

|

KS |

121,793 |

482,450 |

3,963,549 |

32.5 |

8.2 |

|

KY |

271,050 |

1,073,692 |

7,173,457 |

26.5 |

6.7 |

|

LA |

758,838 |

3,005,933 |

9,706,841 |

12.8 |

3.2 |

|

MA |

439,019 |

1,739,056 |

8,416,558 |

19.2 |

4.8 |

|

MD |

225,563 |

893,507 |

9,767,213 |

43.3 |

10.9 |

|

ME |

111,358 |

441,115 |

1,613,323 |

14.5 |

3.7 |

|

MI |

186,907 |

740,382 |

11,377,612 |

60.9 |

15.4 |

|

MN |

162,627 |

644,203 |

11,677,436 |

71.8 |

18.1 |

|

MO |

151,024 |

598,241 |

10,093,933 |

66.8 |

16.9 |

|

MS |

169,192 |

670,209 |

5,498,601 |

32.5 |

8.2 |

|

MT |

67,276 |

266,496 |

1,454,185 |

21.6 |

5.5 |

|

NC |

359,383 |

1,423,599 |

12,609,610 |

35.1 |

8.9 |

|

ND |

72,591 |

287,550 |

1,523,549 |

21.0 |

5.3 |

|

NE |

41,176 |

163,108 |

3,550,874 |

86.2 |

21.8 |

|

NH |

27,491 |

108,898 |

1,322,906 |

48.1 |

12.1 |

|

NJ |

127,441 |

504,823 |

12,690,385 |

99.6 |

25.1 |

|

NM |

52,500 |

207,965 |

3,519,503 |

67.0 |

16.9 |

|

NV |

62,435 |

247,320 |

3,326,778 |

53.3 |

13.5 |

|

NY |

392,997 |

1,556,752 |

26,312,190 |

67.0 |

16.9 |

|

OH |

232,238 |

919,949 |

14,859,785 |

64.0 |

16.2 |

|

OK |

359,893 |

1,425,620 |

6,720,863 |

18.7 |

4.7 |

|

OR |

86,165 |

341,320 |

4,039,599 |

46.9 |

11.8 |

|

PA |

35,221 |

139,519 |

14,650,146 |

415.9 |

105.0 |

|

PR |

123,696 |

489,989 |

2,383,432 |

19.3 |

4.9 |

|

RI |

150,000 |

594,185 |

1,316,568 |

8.8 |

2.2 |

|

SC |

104,804 |

415,153 |

6,885,651 |

65.7 |

16.6 |

|

SD |

101,556 |

402,287 |

1,469,588 |

14.5 |

3.7 |

|

TN |

134,100 |

531,201 |

9,882,797 |

73.7 |

18.6 |

|

TX |

199,102 |

788,689 |

55,385,194 |

278.2 |

70.2 |

|

UT |

178,569 |

707,353 |

4,658,725 |

26.1 |

6.6 |

|

VA |

173,492 |

687,242 |

10,544,465 |

60.8 |

15.3 |

|

VT |

50,692 |

200,803 |

901,952 |

17.8 |

4.5 |

|

WA |

109,239 |

432,721 |

7,382,859 |

67.6 |

17.1 |

|

WI |

287,112 |

1,137,317 |

7,050,986 |

24.6 |

6.2 |

|

WV |

163,066 |

645,942 |

2,686,360 |

16.5 |

4.2 |

|

WY |

30,512 |

120,865 |

856,234 |

28.1 |

7.1 |

|

Total |

9,186,791 |

36,391,012 |

473,811,380 |

51.6 |

13.0 |

Source: GAO analysis of Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) data on State Administrative Expense (SAE) grants. | GAO‑25‑106977

aWe excluded the U.S. Virgin Islands because it does not need to comply with the SAE state funding requirement. In accordance with 42 U.S.C. 1776(f), SAE funding shall be made only to states that agree to maintain a state level of funding for administrative costs not less than the amount expended or obligated in fiscal year 1977; the U.S. Virgin Islands did not provide funding for administrative costs in fiscal year 1977. Under the statute, the SAE state funding requirement is not adjusted for inflation. In addition to the SAE state funding requirement, in accordance with 7 C.F.R. 210.17, states must also support school meal programs through a state revenue matching requirement, which shall not be less than 30 percent of the general cash assistance received by the state during school year 1980-81. States provide these funds to eligible school food authorities to cover all or some of the food, labor, and other administrative costs associated with these programs. According to FNS, state funds provided to support the state funding requirement may not be counted toward this requirement. Finally, some states may contribute funds beyond the state funding and state revenue matching requirements, but FNS does not track this information.

bFiscal year 2024 initial SAE allocations were higher due to factors related to the pandemic, such as temporary increases in meal reimbursement rates. However, federal SAE allocation amounts have historically been significantly larger than states’ required funding contributions. For example, the share of total federal SAE allocations for fiscal year 2023 was about 36 times the total state required funding contributions.

Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) issued eight management evaluation reports to state agencies in fiscal year 2023 with a State Administrative Expense (SAE)-related finding.

Table 3: Summary of Selected FNS Fiscal Year 2023 Management Evaluation Reports, as of November 2024

|

State agency |

FNS regional office |

Finding related to submitting an amended SAE plana |

SAE observationb |

SAE noteworthy initiative |

SAE plan finding closed |

|

Arkansas Department of Education |

Southwest |

✔ |

✖ |

✖ |

✔ |

|

Hawaii Department of Education |

Western |

✔ |

✖ |

✖ |

✔ |

|

Maine Department of Education |

Northeast |

✔ |

✖ |

✖ |

✔ |

|

New Hampshire Education Department |

Northeast |

✔ |

✖ |

✖ |

✔ |

|

South Carolina Department of Education |

Southeast |

✔ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

|

Tennessee Department of Education |

Southeast |

✔ |

✖ |

✖ |

✔ |

|

Texas Department of Agriculture |

Southwest |

✔ |

✖ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction |

Western |

✔ |

✖ |

✖ |

✔ |

Legend:ü = Identified X = Not identified

Source: GAO analysis of Food Nutrition Service (FNS) documentation. | GAO‑25‑106977

a7 C.F.R. 235.5(c) requires state agencies to submit an amended State Administrative Expense (SAE) plan to their FNS regional office for approval when substantive changes occur.

bAccording to FNS, state agencies are only required to identify corrective actions for findings, not observations.

From fiscal years 2019 through 2023, three of the four selected states (California, Virginia, Wyoming) had financial management reviews (FMR) conducted for their child nutrition programs. Each of these FMRs resulted in at least one SAE-related finding, nearly all of which were closed at the time of our review.

|

State agency |

FNS regional office |

Fiscal year |

Number of findings |

Number of observations |

At least one State Administrative Expense-related finding |

Findings closed |

|

California Department of Education |

Western |

2020 |

4 |

1 |

✔ |

✖ |

|

Virginia Department of Education |

Mid-Atlantic |

2019 |

1 |

0 |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Virginia Department of Education |

Mid-Atlantic |

2022 |

2 |

1 |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Virginia Department of Health |

Mid-Atlantic |

2021 |

4 |

0 |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Wyoming Department of Education |

Mountain Plains |

2019 |

3 |

2 |

✔ |

✔ |

Legend:ü = Identified X = Not identified

Source: GAO analysis of Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) documentation. | GAO‑25‑106977

Note: According to FNS, state agencies are only required

to identify corrective actions for findings, not observations.

GAO Contact

GAO Contact

Kathryn A. Larin, larink@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Rachael Chamberlin (Assistant Director), Brian Egger (Analyst in Charge), Joey Carroll, Adam Darr, Noelle Du Bois, John Mingus, Afsana Oreen, Rhiannon Patterson, Patricia Powell, James Rebbe, Miranda Richard, Ronni Schwartz, Joy Solmonson, and Curtia Taylor made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports

and Testimony

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports

and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste,

and Abuse in Federal Programs

To Report Fraud, Waste,

and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

General Inquiries

[1]Matthew P. Rabbitt, Madeline Reed-Jones, Laura J. Hales, and Michael Burke, “Household Food Security in the United States in 2023.” Economic Research Report No. 337, U.S. Department of Agriculture. (Washington, D.C.: September 2024).

[2]See 42 U.S.C. § 1776(a), 7 C.F.R. § 235.1. For the Child and Adult Care Food Program, SAE funds support the administration of both the child and adult care components. According to FNS, the Food Distribution Program is also referred to as USDA Foods in Schools.

[3]These figures exclude the Special Milk Program and the USDA Foods in Schools program.

[4]States may change which state agencies administer their child nutrition programs; therefore, the total number of state agencies that receive SAE funds may vary each year. For example, FNS allocated SAE funds to 83 state agencies in fiscal year 2024 and 84 state agencies in fiscal year 2023.

[5]42 U.S.C. § 1776(f). The state funding requirement applies to the state as a whole and includes all the state agencies administering child nutrition programs. According to FNS, SAE funds should supplement, not supplant, state funding resources.

[6]Specifically, we interviewed representatives from the (1) American Commodity Distribution Association, (2) Child and Adult Care Food Program National Professional Association, (3) Food Research & Action Center, and (4) School Nutrition Association.

[7]As of fiscal year 2024, FNS allocates SAE funds to state agencies in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. American Samoa and Northern Mariana Islands do not receive SAE funds and are therefore excluded from our analysis. In addition, because only states as defined under statute are eligible to receive SAE funds, and because tribal governments are not included in that definition, they are not eligible to receive funds. For reporting purposes, we use the term “states” to refer to states, the District of Columbia, and territories. We also analyzed the most recent FNS data on carryovers and transfers of SAE funds by state agencies, from fiscal years 2019 through 2023. We also included available FNS information on fiscal year 2025 SAE funding amounts for additional context.

[8]While FNS provided us a copy of each state agency’s most recently approved SAE plan, over a third of these 84 SAE plans had been approved by FNS more than 3 years ago. To ensure our analysis accurately reflected each state agency’s most current SAE activities, we analyzed the SAE plans that were approved by FNS during fiscal year 2023. FNS’s review of SAE plans submitted for approval in fiscal year 2024 was ongoing at the time of our review.

[9]Melissa Rothstein, Vivian Gabor, Chris Manglitz, and Shaima Bereznitsky, Assessing the Child Nutrition State Administrative Expense Formula (Rockville, Maryland: Westat, 2020). We reviewed this 2020 study, which examines the effectiveness of the formula used for allocations of SAE funds, identifies and examines factors that influence state agency spending, and presents a series of options for consideration. The study analyzed interviews with 12 purposively selected states and input from 37 stakeholders who provided public comment, among other things. Although we found the study was well-designed and implemented, we identified several limitations. For example, the study did not include an economic analysis of the options considered, such as a cost-benefit analysis, and did not define criteria for the level of funding that would be considered “sufficient.” Nevertheless, we found the study was sufficiently reliable for the purposes of describing SAE-related challenges identified from its qualitative analyses.

[10]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

[11]According to FNS, state agencies were able to use SAE funds to support the new Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer Program for Children (Summer EBT) during fiscal year 2023, but they can no longer do so because separate administrative funds were made available for the program.

[12]In fiscal year 2025, Congress appropriated $17 million to support such activities through Farm to School Grants and state agencies are among the eligible recipients for these grants.

[13]States also receive separate funds to support the oversight of the Child and Adult Care Food Program, which are known as “CACFP audit funds.”

[14]In accordance with 42 U.S.C. § 1776(a)(1)(A), the total amount available nationwide for allocation to state agencies is an amount that is not less than 1.5 percent of the federal funds expended for the National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, Special Milk Program, and Child and Adult Care Food Program during the second preceding fiscal year. While there is no federal reimbursement for USDA Foods in Schools, the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 allows SAE funds to be used by state agencies administering the program, and the program is reflected in the allocations state agencies receive, according to FNS.