ELECTRIC VEHICLE INFRASTRUCTURE

Improved Performance Management Needs to Be Part of Any Related Federal Efforts

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Elizabeth Repko at repkoe@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106992, a report to congressional committees

ELECTRIC VEHICLE INFRASTRUCTURE

Improved Performance Management Needs to Be Part of Any Related Federal Efforts

Why GAO Did This Study

States, localities, and private entities are working to build a nationwide network of publicly accessible electric vehicle chargers. DOE, DOT, and the Joint Office have supported the building of this network through the NEVI and CFI programs created under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) in 2021. Related actions starting in 2025 are ongoing. These include an executive order to pause the disbursement of certain IIJA funds, DOT’s initiation of a review of NEVI and CFI activities in alignment with current policies and priorities, and staff reductions at the Joint Office.

The Explanatory Statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 includes a provision for GAO to assess federal efforts related to electric vehicle charging infrastructure. This report evaluates federal agencies’ collaboration practices, the Joint Office’s assessment of its activities, and FHWA’s assessment of federal programs supporting charging infrastructure, among other objectives.

GAO reviewed relevant statutes and regulations; analyzed agency documents; compared agency efforts with leading practices; and interviewed agency officials and 23 stakeholders, such as state DOTs. Most of GAO’s work was completed by January 2025 and does not assess changes since then.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations, including that the Joint Office and DOT fully implement a performance management framework. The Joint Office and DOT did not take a position on GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

The number of electric vehicles in the U.S. has increased in recent years, but according to the Congressional Research Service the limited network of chargers presents a barrier to their adoption. The Department of Energy (DOE), Department of Transportation (DOT), and Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (Joint Office) have collaborated extensively to advance electric vehicle charging infrastructure. For example, DOE and DOT documented in 2021 how they would align their resources and expertise in establishing the Joint Office to facilitate an interagency approach to supporting charging infrastructure.

The Joint Office has played a key role in coordinating efforts to advance a nationwide electric vehicle charging network, such as by providing technical assistance to state DOTs. Most stakeholders GAO interviewed in 2023 and 2024 (16 of 23) found the Joint Office’s efforts to be helpful. The Joint Office has taken some steps to assess its activities, but GAO found it generally has not defined performance goals with measurable targets and time frames for its activities. Fully implementing a performance management framework that defines and assesses progress could better position the Joint Office to support DOE, DOT, and others involved in building the electric vehicle charging network. As of May 2025, the Joint Office was reviewing its efforts. Its future activities would benefit from finding ways to better use performance information to set priorities.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), within DOT, administers two programs that support public electric vehicle charging infrastructure: the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program (NEVI) and the Charging and Fueling Infrastructure Discretionary Grant Program (CFI). As of April 2025, 384 NEVI- and CFI-funded chargers were open to the public. FHWA has identified long-term outcomes for the programs and collected some performance information, such as tracking the number of chargers. However, FHWA has not fully defined performance goals for some of the main purposes of NEVI, including improving access to electric vehicle chargers. Further, FHWA has not defined any performance goals for CFI that would enable it to assess progress in the near term. Fully implementing a performance management framework for the programs could help FHWA better achieve results and inform the public and Congress of the effectiveness of federal investments. As of May 2025, FHWA was reviewing NEVI and CFI activities. Improved performance management can help better convey the effectiveness of federal investments.

Abbreviations

|

AFC |

alternative fuel corridor |

|

CFI |

Charging and Fueling

Infrastructure Discretionary |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

EV-ChART |

Electric Vehicle Charging Analytics and Reporting Tool |

|

FAST Act |

Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act |

|

FHWA |

Federal Highway Administration |

|

GPRA |

Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

Joint Office |

Joint Office of Energy and Transportation |

|

MOU |

memorandum of understanding |

|

NEVI |

National Electric

Vehicle Infrastructure Formula |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 22, 2025

The Honorable Cindy Hyde-Smith

Chair

The Honorable Kirsten Gillibrand

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development,

and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Steve Womack

Chairman

The Honorable James E. Clyburn

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development,

and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The number of electric vehicles in use in the United States has increased in recent years, with the Department of Energy (DOE) estimating that about 3.5 million of the nation’s 287 million vehicles in 2023 were electric vehicles.[1] However, the Congressional Research Service has found that one barrier to the public’s adoption of electric vehicles is the limited network of electric vehicle charging stations.[2] According to DOE’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory, about 1.2 million publicly accessible charging ports (i.e., the individual charger that provides power to charge one vehicle at a time) will be needed in 2030 to support the projected growth.[3] As of May 2025, there were approximately 219,000 publicly accessible electric vehicle charging ports throughout the United States.[4]

Federal efforts to support the development and deployment of electric vehicle charging infrastructure span multiple federal entities, including DOE, the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), and the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (Joint Office)—created in 2021 under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)—and is staffed by both DOE and DOT. Under the IIJA, the Joint Office was created to study, plan, coordinate, and implement issues of joint concern related to electric vehicle charging infrastructure. For example, the Joint Office is tasked with providing technical assistance related to deploying, operating, and maintaining zero-emission charging and refueling infrastructure. This infrastructure includes public electric vehicle chargers.

The Joint Office provides such technical assistance for FHWA’s National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program (NEVI) and Charging and Fueling Infrastructure Discretionary Grant Program (CFI). These programs provide funding in part to support the deployment of public electric vehicle charging infrastructure. The IIJA authorized and appropriated $7.5 billion in funding for these programs combined for fiscal years 2022 through 2026.[5] Congress has expressed concern over the pace at which charging ports have been built under the NEVI and CFI programs, which had built a total of 384 charging ports as of April 2025.

Related actions may affect federal efforts supporting electric vehicle charging infrastructure. On January 20, 2025, the Trump administration issued an executive order to pause the disbursement of certain funds appropriated through the IIJA, specifically identifying NEVI and CFI.[6] The executive order also directed agencies to review their processes, policies, and programs for issuing grants and other financial disbursements under the IIJA for consistency with the law and executive order. FHWA officials told us in March 2025 that, as a result of this executive order and related agency actions, most of FHWA’s NEVI and CFI activities were under review while it and other relevant agencies determine whether these efforts align with the administration’s policies and priorities. Officials did not provide a time frame of their review process. As of May 2025, these reviews were ongoing and their outcomes unknown.

In addition, on February 6, 2025, FHWA issued a letter to state DOT directors rescinding the current and prior versions of NEVI Formula Program Guidance.[7] In this letter, FHWA stated that it aimed to have updated draft NEVI Formula Program Guidance published and available for comment in spring 2025. As of early July 2025, FHWA had not published the draft updated NEVI Formula Program Guidance.[8] Further, the Joint Office has undergone staffing changes since the beginning of 2025, including a significant reduction in its workforce. Additionally, according to a White House fact sheet, the President’s fiscal year 2026 budget cancels $6 billion in IIJA funds for electric vehicle charger programs.

The Explanatory Statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 includes a provision for GAO to assess the Joint Office’s work, FHWA’s efforts to designate national corridors for electric vehicle charging and alternative fueling stations, and any opportunities to improve coordination among federal agencies in implementing electric vehicle infrastructure investments under the IIJA.[9] In this report, we (1) evaluate the extent to which federal agencies’ efforts to advance electric vehicle charging infrastructure have aligned with leading practices for collaboration; (2) identify the challenges states and other stakeholders have faced in implementing federal electric vehicle charging infrastructure programs, and actions the Joint Office has taken to support stakeholders; (3) evaluate the extent to which the Joint Office’s assessment of its activities has aligned with key performance management practices; and (4) evaluate the extent to which FHWA’s assessment of federal programs supporting public electric vehicle charging infrastructure has aligned with key performance management practices.

To evaluate the extent to which federal entities—specifically, DOE, DOT, FHWA, and the Joint Office—have collaborated to advance electric vehicle charging infrastructure, we reviewed the agencies’ efforts to provide technical assistance, implement NEVI and CFI, and other activities for alignment with leading collaboration practices identified in our prior work.[10]

To identify challenges states and other stakeholders have faced in implementing federal electric vehicle charging infrastructure programs, we interviewed a selection of 23 national and regional organizations, state DOTs, CFI grant recipients, and private sector entities. We selected these stakeholders based on the proportion of the state population in urban areas, the number of certain high-power electric vehicle charging ports on designated highways (known as alternative fuel corridors (AFC)), and other criteria.[11] The views of interviewees are illustrative and not generalizable to all entities involved in grant programs for federal electric vehicle charging infrastructure. We conducted these stakeholder interviews in 2023 and 2024, before the Trump administration issued the previously mentioned executive order and related actions were taken by executive agencies affected by the order. To identify actions the Joint Office has taken to support stakeholders in deploying electric vehicle charging infrastructure, we reviewed Joint Office publications and reports and other publications.

To evaluate the extent to which the Joint Office has assessed the effectiveness of its activities, we compared documented performance goals that the Joint Office provided to us with key performance management practices developed in our prior work on evidence-based policymaking: defining desired outcomes, collecting performance information, and using performance information.[12]

To evaluate the extent to which FHWA has assessed the progress of federal programs supporting public electric vehicle charging infrastructure, specifically NEVI and CFI, we compared FHWA’s actions with the same key performance management steps and practices identified above.[13]

For all our research objectives, we reviewed relevant statutes, regulations, and documents. We also interviewed officials from DOE, DOT, FHWA, and the Joint Office. For more information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We completed the majority of our audit work prior to January 2025. We confirmed this information with the agencies in March 2025. To the extent practicable, we have included references to the developments since January 2025 described above in this report. However, because these changes were still ongoing as of May 2025, this report does not assess them.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Types and Costs of Electric Vehicle Chargers

Different types of electric vehicle charging equipment provide varying power levels at different costs. Three general types of electric vehicle charging equipment (designated by levels) are expected to dominate the charging infrastructure from 2025 to 2035, according to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine:[14]

· Level 1 charging ports are the simplest of the three charger types, as they are common residential 120-volt outlets.

· Level 2 chargers require higher-power electrical service, similar to a typical clothes dryer (240 volts).

· Level 3—commonly referred to as “DC fast charging”—rely on even higher-power electrical service (e.g., 480 volts) and are not available for use in private homes.[15]

Level 1 charging ports provide the smallest driving range per time charged and Level 3 the greatest. For example, with one hour of charging, a Level 1 charging port provides approximately 5 miles of driving range, a Level 2 charger 25 miles, and a DC fast charger 100 to 200 or more miles. Currently, Level 2 chargers are the most common type of charger installed in public settings, according to DOE data.

Lower-power charging equipment (Levels 1 and 2) can be more readily installed at a wide range of facilities—homes, businesses, and public facilities—at a relatively low cost compared with DC fast chargers. For example, Level 1 chargers may cost about $600 to $800 per charging port to purchase and between $400 and $900 per charging port to install.[16] Level 2 chargers may cost about $900 to $3,000 per charging port to purchase and between about $700 and $4,000 per charging port to install.[17] The fastest DC fast charger can cost over $140,000 per charging port to purchase and more than $39,000 per charging port to install, when between three and five charging ports are installed.[18] According to DOT officials, the costs of purchasing and installing public electric vehicle charging equipment can vary significantly depending on the location; whether connections to electricity supply are needed; construction costs; and other factors.

Distribution of and Access to Public Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure

Currently, most electric vehicle owners rely on home charging, and this method is likely to predominate in the near future, according to DOE estimates.[19] Workplace charging, in which drivers charge their vehicles during work shifts, is also increasingly common.[20] Vehicles parked at a workplace, like vehicles parked at home, tend to sit idle for hours at a time, allowing them the time needed to recharge. In prior work, we reported that as the number of electric vehicles on the road increases, many retail establishments, places of business, and other public venues are starting to see value in providing chargers to their customers, employees, and visitors.[21]

Public chargers—charging equipment that is in a public location and available to anyone—enable drivers to recharge their electric vehicles when other forms of charging are unavailable or inconvenient, or when a trip exceeds a vehicle’s range (usually from around 110 to 300 miles). Public chargers also help serve electric vehicle drivers who live in types of homes, such as apartments, that may not readily accommodate charging equipment, and drivers who cannot afford to install such equipment at home.[22]

Public chargers are currently limited in number. According to DOE, as of May 2025, there were approximately 219,000 publicly available individual charging ports at 77,000 electric vehicle charging stations in the country.[23] Most of these ports (162,000) are Level 2 charging ports, with fewer DC fast chargers (56,000) and Level 1 charging ports (800).[24] These charging stations may be located at different kinds of facilities (e.g., shopping malls, hotels, and apartment complexes) and owned by a range of entities (e.g., private firms, municipalities, utilities, and automakers).

According to the Congressional Research Service, the United States has a limited network of publicly available charging stations.[25] Following enactment of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act) in 2015, states have nominated and FHWA has designated AFCs to help guide the placement of some of these chargers.[26] According to FHWA, 92 percent of the nation’s Interstate System is designated as an AFC. Current public electric vehicle charging stations are not distributed equally across the nation. For example, according to a 2024 Pew Research Center report, 60 percent of urban residents live within one mile of a public charger, compared with 41 percent of suburban and 17 percent of rural residents.[27]

Roles in Developing Public Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure

Multiple stakeholders are involved in building public electric vehicle charging infrastructure. For example, state and local government agencies—including state departments of transportation, energy, and environment—develop plans and designs for public electric vehicle charging stations. Private sector entities—such as some utilities, companies that manufacture charging equipment, and site owners—are involved in constructing and operating the charging stations.

Federal agencies also play a role in supporting the development of electric vehicle charging infrastructure. DOE—through the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy’s Vehicle Technologies Office and the National Laboratories—conducts research on charging infrastructure, including a 2023 report estimating the future demand for electric vehicle charging infrastructure in the United States.[28] DOE also manages data collection related to charging infrastructure; DOE’s Alternative Fueling Station Locator includes a map of public electric vehicle charging stations throughout the nation. FHWA is responsible for administering the NEVI and CFI programs. Accordingly, it issues relevant regulations and program guidance, reviews and approves state NEVI plans, reviews CFI program grant applications, and provides technical support to state DOTs.

With staff from both DOE and DOT, the Joint Office supports DOE, FHWA, and others—including state and local governments and private sector entities—that are directly involved in building electric vehicle charging infrastructure. For example, to support FHWA in administering NEVI, the Joint Office reviews state NEVI plans and provides its assessments to FHWA for consideration. The Joint Office also answers technical questions posed by the numerous stakeholders involved in building charging infrastructure. The Joint Office does so by, for example, hosting webinars, publishing help sheets and best practices, and convening meetings of stakeholders. As authorized under the IIJA, the staffing and programs of the Joint Office are funded with a $300 million set-aside from the appropriated funding for NEVI for fiscal year 2022, which is available until expended.[29]

As part of its support of NEVI and CFI, the Joint Office developed a data collection platform known as the Electric Vehicle Charging Analytics and Reporting Tool (EV-ChART). States and other direct recipients of NEVI grant funding or any Title 23 funds used to construct public electric vehicle chargers, such as CFI grant funding, must submit data for operational electric vehicle charging stations to the Joint Office, via EV-ChART, on a one-time and regular basis.[30] Such data include any error codes associated with an unsuccessful charging session, the energy dispensed to electric vehicles per charging session by port, and the reliability or “uptime” of each station’s charging ports.

Federal Grant Programs That Support Public Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure

The NEVI and CFI programs provide funding, in part, to support the deployment of public electric vehicle charging infrastructure. As noted above, the Trump administration issued an executive order on January 20, 2025, to pause the disbursement of certain funds appropriated through the IIJA, specifically identifying NEVI and CFI.[31] FHWA officials told us in March 2025 that, as a result of this executive order and related agency actions, most of FHWA’s NEVI and CFI activities were under review while it and other relevant agencies determine whether these efforts align with the administration’s policies and priorities. As of May 2025, these reviews were ongoing and their outcomes unknown.

National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program. The IIJA appropriated $1 billion annually in funding for fiscal years 2022 through 2026 for NEVI.[32] Using a formula set in statute, FHWA distributes NEVI grant funding to states, in part to deploy electric vehicle charging infrastructure located along AFCs.[33] However, states may use their NEVI grants for eligible projects on any public road or in other publicly accessible locations, provided certain conditions are met.[34]

The IIJA required the Secretary of Transportation to issue guidance for states and localities to strategically deploy electric vehicle charging infrastructure under NEVI.[35] FHWA developed this guidance in response to this requirement and last updated it in June 2024, but rescinded it in February 2025.[36] The guidance included criteria that a state had to meet for FHWA to certify that the state’s AFC was fully built, after which the state could use its NEVI funds on an eligible project on any public road or publicly accessible location, such as public schools and parks. For example, electric vehicle charging stations along designated AFCs were required to be located no more than 50 miles apart and within one mile of the designated roadway.[37]

The guidance also specified the information states were to include in their state NEVI plans.[38] This information included how the state would coordinate with other entities; the vision and goals of the state’s NEVI efforts; and whether the state intended to contract with private entities for projects to install, operate, or maintain electric vehicle charging infrastructure funded under NEVI. The guidance stated that the Joint Office and FHWA would work together to review the plans submitted by each state and that FHWA would approve them.

The IIJA also required the Secretary of Transportation to develop minimum standards and requirements related to NEVI-funded projects.[39] In response to this requirement, FHWA published a February 2023 final rule, which became effective in March 2023, establishing regulations that contain such minimum standards and requirements.[40] Under these regulations, electric vehicle charging stations located along and designed to serve users of designated AFCs must have at least four DC fast charging ports—as opposed to Level 1 or Level 2 chargers—and be capable of simultaneously charging at least four electric vehicles.

As of April 2025, 300 NEVI-funded public charging ports were operating across 68 stations in 16 states.[41] See figure 1 for an example of a NEVI-funded public charging station. One state (Rhode Island) had fully built its AFCs, giving the state the ability to install NEVI-funded charging infrastructure at other public locations.

Figure 1: Charging Station Funded by the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Program in Richmond, Kentucky

Charging and Fueling Infrastructure Discretionary Grant Program. The IIJA authorized $2.5 billion in total for fiscal years 2022 through 2026 for CFI.[42] The statutory purpose of the program is to provide grants to eligible entities to strategically deploy publicly accessible electric vehicle charging infrastructure, as well as other alternative fueling infrastructure—specifically hydrogen, propane, and natural gas fueling—along AFCs or in certain other accessible locations.[43] Unlike NEVI, which is a formula grant program under which all eligible recipients receive grant funding, CFI is a discretionary grant program under which eligible recipients must apply for grants. FHWA awards CFI grants based on a competitive process. Depending on the CFI grant category, grant recipients may use their CFI funding to construct publicly accessible electric vehicle charging and other alternative fueling infrastructure.[44] For electric vehicle charging infrastructure specifically, CFI grant recipients can use their grant funds to build either DC fast chargers or Level 2 chargers.

As of January 2025, FHWA had announced a total of almost $1.8 billion to 147 CFI grants. According to the Joint Office, as of March 2025, CFI grant recipients had opened 84 CFI-funded public charging ports across two stations in two states.

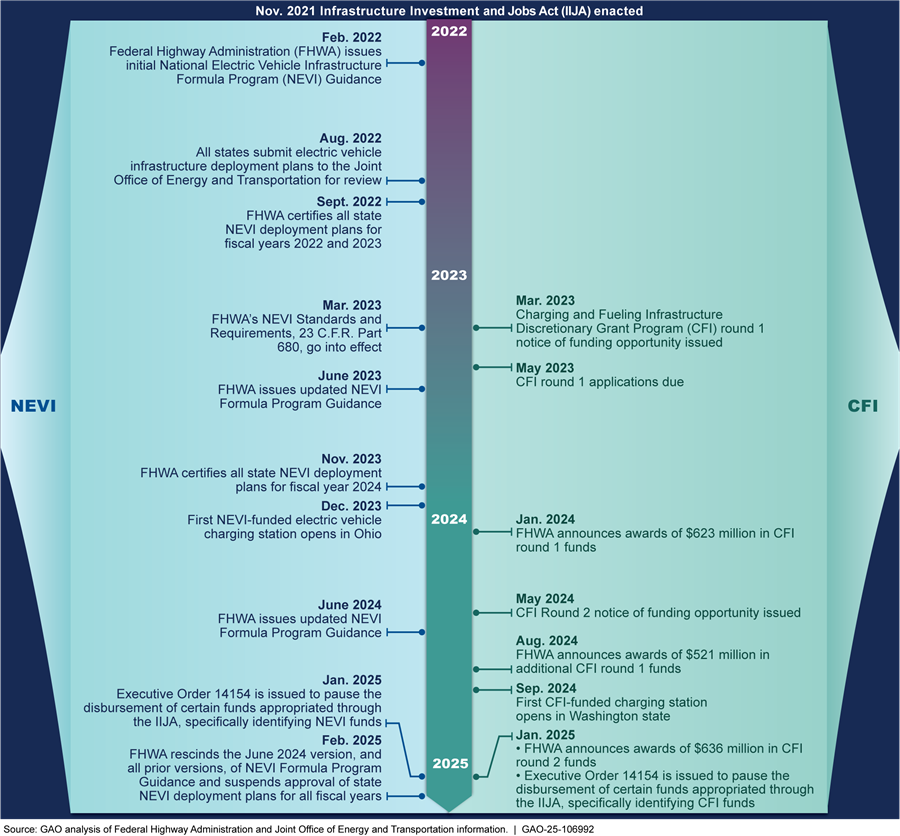

Figure 2 outlines key dates related to establishing and implementing the NEVI and CFI programs.

Figure 2: Timeline of Selected Activities Related to the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program (NEVI) and the Charging and Fueling Infrastructure Discretionary Grant Program (CFI)

Federal Agencies Working on Charging Infrastructure Followed Leading Practices for Collaboration

We identified leading practices for interagency collaboration in our prior work, along with key considerations for collaborating agencies when implementing them.[45] Implementing these practices is critical to achieving important interagency outcomes and can help address crosscutting challenges, such as deploying electric vehicle chargers.

According to our analysis, the efforts of DOE, DOT (including FHWA), and the Joint Office to advance electric vehicle charging infrastructure have generally aligned with all eight of the leading practices for interagency collaboration. For example, in a December 2021 memorandum of understanding, DOE and DOT documented key areas of understanding in aligning their resources and expertise to establish the Joint Office, which would facilitate an interagency approach to supporting the deployment of electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Successfully following these collaboration practices—as DOE, DOT, and the Joint Office did—can help agencies address fragmented roles.[46]

We completed this assessment in March 2025 (see table 1), after the Trump administration issued an executive order in January 2025 directing agencies to review their processes, policies, and programs for issuing grants under the IIJA for consistency with the law and the executive order.[47] As of May 2025, the reviews related to NEVI and CFI were ongoing and their outcomes unknown. Further, the Joint Office has undergone staffing changes since the beginning of 2025. Joint Office officials told us that as of May 2025, the office had 17 staff—a reduction from about 50—and was currently led by an acting director who was also a DOE federal employee.[48] According to officials, the Joint Office’s work was continuing, and it was operating within DOE’s Vehicle Technologies Office, which helped to initially stand up the Joint Office. Our assessment does not take into account the outcomes of these ongoing reviews or staffing changes. Table 1 notes specific items under review that we considered in our assessment.

Table 1: Assessment of Federal Interagency Collaboration to Advance Public Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure

|

Leading practice |

Alignment of federal efforts with the practicea |

|

|

Define common outcomes: clearly define long- and short-term outcomes; reassess and update outcomes, as needed |

|

The Departments of Energy (DOE) and Transportation (DOT) developed a joint agency priority goal—with the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (Joint Office) as a co-leader—to support the increased deployment of publicly available electric vehicle charging ports to 310,000 by the end of 2025, which contributed to the longer-term outcome of a national network of at least 500,000 charging ports by 2030.b The agency priority goal was initially established in fiscal year 2022 and updated in fiscal year 2024. In March 2025, agency officials told us the agency priority goal remained in effect, but they were reviewing it in alignment with current policies and priorities. |

|

Ensure accountability: identify ways to monitor, assess, and communicate progress toward the short- and long-term outcomes |

|

DOE, DOT, and the Joint Office have monitored, assessed, and communicated progress toward the joint agency priority goal through DOE’s Alternative Fueling Station Locator, performance indicators, and quarterly reports. These entities issued the most recent agency priority goal report in January 2025, which covered the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2024. As noted above, the agency priority goal and related reports were under review at the time of our analysis. |

|

Bridge organizational cultures: develop strategies to build trust among participants; establish compatible policies and procedures to operate across agency boundaries |

|

Joint Office officials told us its staff split their in-office days between the DOE and DOT buildings, to give staff at each agency a greater sense of ownership over the Joint Office. Because DOE is the Joint Office’s host agency, the Joint Office has used DOE’s operating procedures. |

|

Identify and sustain leadership: identify a lead agency or individual; clearly identify and agree upon leadership roles and responsibilities; determine how leadership will be sustained over the long term |

|

The memorandum of understanding (MOU) between DOE and DOT regarding the Joint Office, initially signed in 2021 and updated in early January 2025, identifies the Joint Office Executive Director as responsible for leading the Joint Office, and the deputy secretaries of DOE and DOT as responsible for conducting oversight of the Joint Office.c By establishing and implementing its process to review and update the MOU, DOE, DOT, and Joint Office officials helped to sustain their collaboration over time. In March 2025, agency officials told us the MOU remained in effect, but they were reviewing it in alignment with current policies and priorities. |

|

Clarify roles and responsibilities: clarify roles and responsibilities of the participants; agree upon a process for making decisions |

|

In their MOU, DOE and DOT clearly define and agree on roles and responsibilities for key operational and oversight functions of the Joint Office. DOE, DOT—including the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)—and the Joint Office worked together to determine the Joint Office’s roles in the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program (NEVI) and the Charging and Fueling Infrastructure Discretionary Grant Program (CFI), which help fund electric vehicle charging or other alternative fueling infrastructure projects. According to Joint Office officials, the Joint Office has used its regular meetings with DOE and DOT leadership, FHWA, and other staff to make decisions and determine programmatic roles and responsibilities. |

|

Include relevant participants: include all relevant participants; participants have the appropriate knowledge, skills, and abilities to contribute |

|

The Joint Office has sought out staff and expertise that align with its responsibilities, including drawing staff from DOE’s National Laboratories and the Volpe Center—DOT’s fee-for-service innovation center—and hiring contractors with industry experience. |

|

Leverage resources and information: determine how to staff and fund the collaboration; use tools and technologies to share relevant data and information |

|

The Joint Office brought on staff from DOE and DOT and hired additional staff, including contractors with specific expertise. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act authorized the transfer of $300 million to the Joint Office for fiscal year 2022 for it to carry out its responsibilities. The Joint Office has leveraged tools and resources from DOE and DOT to support its technical assistance efforts. |

|

Develop and update written guidance and agreements: document agreements regarding the collaboration; develop ways to continually update or monitor written agreements |

|

DOE and DOT documented keys areas of understanding in establishing the Joint Office in the December 2021 MOU. Under the Biden administration, DOE and DOT entered into an updated MOU in January 2025, which maintained nearly all of the original MOU. As noted above, the MOU was under review at the time of our analysis. |

![]() Generally aligned

Generally aligned ![]() Partially aligned

Partially aligned ![]() Not

aligned

Not

aligned

Source: GAO analysis of DOE, DOT, FHWA, and Joint Office information. | GAO‑25‑106992

Note: We compared the interagency collaboration efforts of DOE, DOT, and the Joint Office to advance public electric vehicle charging infrastructure with leading collaboration practices that we identified in our prior work: GAO, Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges, GAO‑23‑105520 (Washington, D.C.: May 24, 2023). We also included their collaboration with FHWA, one of DOT’s operating administrations, because FHWA administers two of the grant programs that support the deployment of electric vehicle chargers: NEVI and CFI.

aWe assigned these ratings based on our review of (1) the memorandums of understanding and (2) the agency priority goal and related efforts. We completed the majority of our audit work prior to January 2025. We confirmed this information with the agencies in March 2025. In January 2025, the Trump administration issued an executive order directing agencies to review their processes, policies, and programs for issuing grants, including NEVI and CFI, and other financial disbursements under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act for consistency with the law and executive order. See Exec. Order 14154, Unleashing American Energy, 90 Fed. Reg. 8353 (Jan. 20, 2025). As of May 2025, the reviews related to NEVI and CFI were ongoing and their outcomes unknown. The Joint Office has also undergone staffing changes since the beginning of 2025. Our assessment does not take into account the outcomes of these ongoing reviews or staffing changes.

bThe agency priority goal included chargers funded by NEVI and CFI, as well as chargers funded entirely by other sources, such as private entities. As such, given that most growth in public chargers to date has occurred because of private investment, this goal reflected the overall end-state that federal efforts were aiming toward, and not necessarily the progress or investment of specific federal programs. Agency priority goals are part of a performance accountability structure established under the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 (GPRA) and amended by the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010. Among other things, agency priority goals must reflect the highest priorities of the agency, be informed by the federal government priority goals, and have ambitious targets that can be achieved within a 2-year period, as well as clearly defined quarterly milestones. See GPRA, Pub. L. No. 103‑62, 107 Stat. 285 (1993); GPRA Modernization Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111‑352, § 5, 124 Stat. 3866, 3874 (2011) (codified as amended at 31 U.S.C. § 1120(b)). These goals can provide agencies an opportunity to bring focus to mission areas where agencies need to drive significant progress and change.

cThe Executive Director of the Joint Office, hired in 2022, departed in February 2025. There has since been an acting Executive Director.

Stakeholders Cited Challenges to Implementing Federal Charging Infrastructure Programs, Which the Joint Office Has Sought to Address

Stakeholders we interviewed identified several challenges to implementing federal electric vehicle charging infrastructure programs. The Joint Office has helped stakeholders advance electric vehicle charging infrastructure through information-sharing and coordination activities. Most stakeholders we interviewed said that the Joint Office was helpful.

Stakeholders Described Planning, Cost, and Other Challenges to Implementing Federal Charging Infrastructure Programs

The 23 stakeholders we interviewed—which included national organizations, state DOTs, regional electric vehicle charging groups, CFI grant recipients, and private sector entities—identified several broad categories of challenges to implementing federal electric vehicle charging infrastructure programs. These challenges included addressing federal requirements, planning, building charging stations in areas with limited power service, covering costs, and coordinating with project partners.[49]

Addressing federal requirements. Eleven stakeholders we interviewed (one national organization, five state DOTs, three regional groups, one CFI grant recipient, and one private sector entity) identified challenges with addressing federal requirements under the NEVI or CFI programs. According to some interviewees, prior electric vehicle infrastructure funding mechanisms considered these projects as energy projects, and state energy offices rather than state DOTs historically led the projects. However, NEVI and CFI projects are treated like federal-aid highway projects—similar to constructing a new highway or rehabilitating a bridge.[50] Thus, NEVI and CFI projects must comply with applicable federal highway requirements, often referred to as “Title 23” requirements.[51] For example, Title 23 requires states to provide oversight of highway projects receiving federal funding. Officials at one state DOT told us it will be challenging for the state DOT to oversee NEVI or CFI projects given that they are built, owned, and operated by a private entity.

Some stakeholders told us they have needed additional time to fully understand how Title 23 requirements apply to installing electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Officials at one state DOT told us the contractors that install electric vehicle charging equipment are generally unfamiliar with Title 23 requirements and must spend a significant amount of time and effort learning them. According to the officials, state DOTs need to hire consultants with more expertise in electric vehicle charging infrastructure, particularly in the design and construction phases, to ensure that all relevant Title 23 requirements are satisfied. Additionally, officials from one state DOT said it had been challenging to identify a contracting method that adheres to both federal and state requirements, given that NEVI-funded chargers would not be owned or operated by the state but would be built with public funds.

Planning. Interviewees told us that they face challenges when planning to build electric vehicle charging stations under the NEVI and CFI programs, particularly related to supply chain constraints and implementing new project types. Six stakeholders we interviewed (three national organizations, two CFI grant recipients, and one private sector entity) told us that supply chain constraints can present challenges when planning for electric vehicle charging infrastructure, including by increasing the amount of time needed to build the infrastructure. For example, representatives from two national organizations told us that some of the equipment necessary to build an electric vehicle charging station, including transformers, can take up to 2 years to acquire, and that appropriate planning for these time frames is necessary.

Moreover, we heard from several stakeholders that building electric vehicle charging infrastructure is a relatively new type of project for state DOTs and that it involves multiple planning steps, such as determining future infrastructure needs and developing timelines for building stations. As such, state DOTs—including two we spoke with—needed to develop staff skills and expertise.

Building charging stations in areas with limited power service. Eight stakeholders we spoke with (five national organizations, one state DOT, one regional group, and one CFI grant recipient) cited challenges associated with identifying locations for electric vehicle charging infrastructure, particularly in rural areas that may not already have sufficient electric service. For example, some rural areas that might otherwise be promising locations for a NEVI station may not have a nearby power source. As such, transmission lines and other electrical equipment may need to be installed before the electric vehicle charging station can operate. Representatives of two national organizations and one private sector entity told us that providing new electric service to these areas can take several years, which slows down the pace of projects.

Covering costs. Four stakeholders we interviewed (two national organizations, one regional group, and one private sector entity) told us that the costs associated with building electric vehicle charging infrastructure can be challenging, in part because federal grant programs do not cover all the associated costs.[52] Representatives of a private sector entity and a regional group told us that building NEVI-funded chargers can be a significant financial investment for site owners and operators. The federal share for a NEVI-funded project is 80 percent of the project costs, and so the state must cover the remaining (i.e., nonfederal) share of 20 percent.[53] The federal share for a CFI-funded project may be up to 80 percent, and thus the nonfederal share must be at least 20 percent.[54] Project costs can include components needed to connect the charging station to the electricity source, signage, and information to users about how to use the charging station.

Further, some rural electric utilities have raised concerns regarding who bears the costs of charging stations, according to a national organization we interviewed. For example, if the selected project site does not have a nearby power supply, transmission lines and other electric utility equipment—which are generally not eligible project costs under NEVI or CFI, according to these organizations—will need to be installed before the electric vehicle charging station can operate.[55] Representatives of this national organization said the costs associated with building that electric infrastructure would be incorporated into rates paid by the utilities’ local customers, even though the primary users of charging stations would be travelers passing through the area.

Coordinating with project partners. Five stakeholders we interviewed (one national organization, one state DOT, two regional groups, and one private sector entity) identified challenges with ensuring the parties involved in implementing electric vehicle charging infrastructure—such as federal agencies, state agencies, and others—are coordinating with one another. For example, officials from a state DOT told us that when preparing their application for a CFI grant, they must coordinate with multiple state agencies to ensure each agency provides input based on its areas of expertise. Additionally, as noted above, state energy offices, rather than state DOTs, historically have led electric vehicle infrastructure projects. As state DOTs are now leading these projects, their staff, stakeholders told us, coordinate with state energy offices to learn how they developed electric vehicle charging stations.

The Joint Office Has Helped Stakeholders Advance Charging Infrastructure Through Information-Sharing and Coordination

The Joint Office has helped states, localities, and other stakeholders advance electric vehicle charging infrastructure through information-sharing and coordination activities. Most of the stakeholders we spoke with (four national organizations, all five state DOTs, all five regional electric vehicle charging groups, one CFI grant recipient, and one private sector entity) generally found that the Joint Office’s efforts to support stakeholders were helpful.

Information-sharing. The Joint Office has shared information with stakeholders on relevant topics in various ways, including by providing technical assistance, hosting webinars, posting information on the Joint Office’s website, and holding meetings. According to the Joint Office, from fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2024, the Joint Office received over 3,000 requests for technical assistance, including nearly 900 in fiscal year 2024.[56] These requests have come from various stakeholders, including private sector entities, state DOTs, and consumers. As of March 2025, the Joint Office told us that it had held nearly 40 webinars covering a variety of topics, such as engaging with utilities in rural areas and contracting methods. The Joint Office’s website includes links to recordings of these webinars, as well as to relevant publications produced by the Joint Office and others. We found that the Joint Office created or shared information related to several of the challenges we identified based on our interviews with stakeholders. For example, our review of the Joint Office’s website identified eight publications—including four produced by the Joint Office—on planning-related topics.

Further, the Joint Office has met with staff from each state DOT to provide feedback on their annual NEVI plans. Officials from four state DOTs we spoke with said that the Joint Office’s comments on their NEVI plans were helpful and addressed the officials’ questions. For example, officials from one state DOT told us the Joint Office recommended that the state’s NEVI plan include more information on public engagement to better respond to NEVI plan requirements. In addition, Joint Office officials told us they have facilitated regional meetings with states to allow state officials to share information with one another.

Coordination. The Joint Office has played a coordinating role for the multiple entities involved in implementing electric vehicle charging infrastructure. For example, the Joint Office worked with an industry standards-setting body that developed an open standard for electric vehicle charging hardware. This new standard helps ensure that any electric vehicle can work with any charger, allowing for the electric vehicle charging network to be interoperable.[57]

In addition, the Joint Office entered into a memorandum of understanding in February 2022 with two national organizations representing state transportation and energy departments: the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials and the National Association of State Energy Officials, respectively. Through this effort, the Joint Office helped convene meetings of federal, state, and local government stakeholders. According to the Joint Office, the meetings improved discussions among stakeholders and helped ensure they made electric vehicle charging infrastructure investments in a strategic, coordinated, and efficient manner.

The Joint Office Has Not Fully Implemented a Performance Management Framework to Assess Its Activities

The Joint Office has established some elements of a performance management framework. However, we found that it does not have fully defined performance goals for its activities and, consequently, is generally unable to use the performance information it collects to assess progress toward goals. According to officials in March 2025, the Joint Office was reviewing its performance management efforts in alignment with current policies and priorities.

Performance management involves measuring the performance of an organization or program in relation to pre-established goals. In our prior work, we identified three key performance management practices that provide a framework to help federal leaders and employees build and use evidence to assess their activities.[58] When effectively implemented, these practices are helpful at any organizational level, such as an individual program or office. The three performance management practices are:

· Define desired outcomes. Organizations establish long-term strategic goals and related objectives to set a general direction for their activities. Additionally, organizations establish one or more performance goals—including a quantitative target and time frame against which performance can be measured—to define the results an effort is expected to achieve in the near term.

· Collect performance information. Organizations identify relevant sources of performance information, collect that information, and determine the need for additional information.

· Use performance information. Organizations use performance information to assess their progress toward goals (i.e., comparing results to planned targets) and inform management decisions, such as plans to expand effective approaches or address performance gaps.

We found that the Joint Office’s efforts to implement a performance management framework generally aligned with one, and partially aligned with two, of these key performance management practices (see table 2). We completed this assessment in March 2025, after the Trump administration issued an executive order in January 2025 directing agencies to review their processes, policies, and programs for issuing grants under the IIJA for consistency with the law and executive order.[59] As of May 2025, the reviews related to NEVI and CFI were ongoing and their outcomes unknown. Further, the Joint Office has undergone staffing changes since the beginning of 2025. Our assessment does not take into account the outcomes of these ongoing reviews or staffing changes.

Table 2: Assessment of Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (Joint Office) Efforts to Implement a Performance Management Framework

|

Performance management |

Alignment of Joint Office |

|

Define desired outcomes |

|

|

Collect performance information |

|

|

Use performance information |

|

![]() Generally aligned

Generally aligned ![]() Partially aligned

Partially aligned

![]() Not

aligned

Not

aligned

Source: GAO analysis of Joint Office information. | GAO‑25‑106992

Note: To assess the Joint Office’s efforts to implement a performance management framework, we compared the Joint Office’s efforts with key performance management practices that we identified in our prior work: GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2023).

aWe assigned these ratings based on our review of (1) the agency priority goal, (2) the Joint Office’s priorities, and (3) the Joint Office’s strategic plan. We completed the majority of our audit work prior to January 2025. We confirmed this information with the agencies in March 2025. In January 2025, the Trump administration issued an executive order directing agencies to review their processes, policies, and programs for issuing grants—including the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program (NEVI) and the Charging and Fueling Infrastructure Discretionary Grant Program (CFI)—and other financial disbursements under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act for consistency with the law and executive order. See Exec. Order 14154, Unleashing American Energy, 90 Fed. Reg. 8353 (Jan. 20, 2025). As of May 2025, the reviews related to NEVI and CFI were ongoing and their outcomes unknown. The Joint Office has also undergone staffing changes since the beginning of 2025. Our assessment does not take into account the outcomes of these ongoing reviews or staffing changes.

Define desired outcomes. As discussed above, DOE and DOT developed a joint agency priority goal—with the Joint Office as a co-leader—to increase publicly available electric vehicle charging ports. They initially established the goal in fiscal year 2022 and updated it in fiscal year 2024. Joint Office officials we spoke with and documentation we reviewed demonstrated that this goal has served as the Joint Office’s long-term strategic goal.[60]

However, the Joint Office does not have fully defined performance goals to monitor its own near-term efforts, as called for by key performance management practices. While the Joint Office cited some performance goals, they do not all include measurable targets and time frames, which are important characteristics of effective performance goals. Measurable targets might include quantifiable information, such as the number of technical assistance products the Joint Office should produce to assist in expanding the electric vehicle charging network. Time frames may include, for example, “by end of the calendar year” or “within 6 months.” Further, as of May 2025, all the Joint Office’s performance goals—and associated documentation—were being reviewed for alignment with the Trump administration’s policies and priorities and, according to Joint Office officials, were subject to change.

Joint Office officials told us that three separate products contain what they consider to be the Joint Office’s performance goals:

· Agency priority goal progress reports. The Joint Office—with support from DOE and DOT—produced quarterly update reports of the agency priority goal. The most recent agency priority goal report was issued in January 2025 and covered the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2024. Joint Office officials said they viewed the key indicators included in the agency priority goal reports—such as increasing the number of states using EV-ChART from 0 to 52—as performance goals. These performance indicators include measurable targets, but most do not clearly include time frames for completion.

· Joint Office priorities. In fiscal years 2023, 2024, and 2025, the Joint Office established “priorities,” which it considers to be performance goals to guide its efforts.[61] The priorities cover various tasks related to the Joint Office’s operations and activities, including providing technical assistance, staffing, and communicating with stakeholders. These priorities generally do not include measurable targets or time frames. Further, Joint Office officials told us that the Joint Office’s priorities were being reviewed in alignment with current policies and priorities.

· Draft strategic plan. The Joint Office provided us with a draft strategic plan document in December 2024. Based on our review, this strategic plan more fully defines the desired outcomes of the Joint Office’s activities. Joint Office officials told us in March 2025 that the strategic plan was not finalized or in effect but that it did inform some of the office’s activities.

Collect performance information. We found that the Joint Office had sources of information related to what it told us were its performance goals, in alignment with this key practice. For example, Joint Office officials told us they collect information on the Joint Office’s activities—such as feedback on technical assistance and publications—during regular meetings with officials from states and other stakeholders. Additionally, according to Joint Office officials, the Joint Office determines what topics to cover in its information-sharing activities based on the challenges that stakeholders have told them about. These officials told us that they also collect a variety of other types of performance information, such as the number of operating NEVI and CFI ports using the Alternative Fueling Station Locator and the uptime of NEVI- and CFI-funded operating charging ports via EV-ChART.

Use performance information. The Joint Office’s efforts to use performance information have focused on the long-term agency priority goal to increase publicly available electric vehicle charging ports. For example, the Joint Office—with support from DOE and DOT—produced quarterly update reports of the agency priority goal to measure progress in achieving that goal, such as the current and targeted number of publicly available electric vehicle charging ports. As noted above, the most recent agency priority goal report was issued in January 2025 and covered the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2024. The Joint Office also produced quarterly reports for the Secretaries of Energy and Transportation that discuss overall progress in deploying a national charging network and achieving the agency priority goal.

However, the Joint Office is generally unable to use the information it collects to assess progress because it has not fully defined its performance goals with measurable targets and time frames. Joint Office officials told us they had not initially developed fully defined performance goals that would enable them to assess their activities because they needed to begin operations soon after the enactment of the IIJA. In doing so, the Joint Office focused on providing support for electric vehicle charging programs, hiring staff, and taking other actions to form the office.

Fully implementing a performance management framework could enable the Joint Office to better use performance information to set priorities, assess progress, and inform decisions about its activities. As the Joint Office moves forward with the review of its efforts, finding ways to better use performance information would also enable it to better support any related federal efforts to build electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

FHWA Has Not Fully Implemented a Performance Management Framework for Its Charging Infrastructure Programs

We found that FHWA, in administering NEVI and CFI, has identified long-term outcomes for the programs but has not fully defined performance goals that would enable it to assess progress in the near term, as called for by key performance management practices (see table 3).[62] FHWA, in coordination with DOE and the Joint Office, has collected information that could allow it to measure the progress of the programs and has taken steps to assess progress, but not fully in relation to performance goals. As noted above, implementing these key performance management practices can help agencies achieve results.[63] We completed this assessment in March 2025, after the Trump administration issued an executive order in January 2025 directing agencies to review their processes, policies, and programs for issuing grants under the IIJA for consistency with the law and executive order.[64] As of May 2025, the reviews related to NEVI and CFI were ongoing and their outcomes unknown. Further, the Joint Office has undergone staffing changes since the beginning of 2025. Our assessment does not take into account the outcomes of these ongoing reviews or staffing changes.

Table 3: Assessment of Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Efforts to Implement a Performance Management Framework for Federal Electric Vehicle Charging Programs

|

Performance management key practice |

Alignment of FHWA efforts with the practicea |

|

|

National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program (NEVI) |

Charging and Fueling Infrastructure Discretionary Grant Program (CFI) |

|

|

Define desired outcomes |

|

|

|

Collect performance information |

|

|

|

Use performance information |

|

|

![]() Generally aligned

Generally aligned ![]() Partially aligned

Partially aligned ![]() Not

aligned

Not

aligned

Source: GAO analysis of FHWA, Department of Energy (DOE), and Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (Joint Office) information. | GAO‑25‑106992

Note: We assessed FHWA’s efforts to define desired outcomes, collect performance information, and use performance information to assess the progress of NEVI and CFI. FHWA administers both grant programs and coordinates with DOE and the Joint Office on these activities. We identified these key performance management practices in our prior work: GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2023). The key practices for performance management generally align with requirements for federal grant programs, which require agencies to establish program goals and objectives and measure the recipient’s performance to show achievement of program goals and objectives, share lessons learned, improve program outcomes, and foster the adoption of promising practices. 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.202, 200.301.

aWe assigned these ratings based on our review of the agency priority goal and related efforts, and other agency documents. We completed the majority of our audit work prior to January 2025. We confirmed this information with the agencies in March 2025. In January 2025, the Trump administration issued an executive order directing agencies to review their processes, policies, and programs for issuing grants, including NEVI and CFI, and other financial disbursements under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act for consistency with the law and executive order. See Exec. Order 14154, Unleashing American Energy, 90 Fed. Reg. 8353 (Jan. 20, 2025). As of May 2025, the reviews related to NEVI and CFI were ongoing and their outcomes unknown. The Joint Office has also undergone staffing changes since the beginning of 2025. Our assessment does not take into account the outcomes of these ongoing reviews or staffing changes.

Define desired outcomes. FHWA has identified long-term outcomes and performance goals for NEVI but does not have goals that measure progress toward some intended outcomes of the program. FHWA officials told us the IIJA defined long-term outcomes of NEVI, and FHWA guidance included additional information about the intended outcomes of the program. The statutory purpose of NEVI is to provide funding to strategically deploy electric vehicle charging infrastructure and establish an interconnected national network to facilitate data collection, reliability, and access.[65] In its final rule establishing its regulations containing the NEVI Standards and Requirements, FHWA stated that this purpose was satisfied by creating a convenient, affordable, reliable, and equitable network of chargers throughout the country.[66] Consistent with the purpose of the program, the regulations require NEVI funding recipients to submit quarterly data on charging station use times, reliability (i.e., uptime), and the duration of any outages, which funding recipients submit via EV-ChART.[67] In the 2024 NEVI Formula Program Guidance that FHWA has since rescinded, FHWA also stated that NEVI funding was in part to help make electric vehicle chargers accessible to all Americans and that states should prioritize access to chargers in rural, disadvantaged, and underserved communities.[68]

FHWA officials said they have managed the performance of NEVI through the DOE-DOT joint agency priority goal on increasing the number and availability of public electric vehicle chargers, although the goal is currently under review. Based on our analysis, the fiscal year 2024 progress reports for the agency priority goal identified some performance indicators and milestones associated with NEVI that serve as near-term performance goals, including a quantitative target and anticipated completion date. For example, these reports identified the following goals related to building out a national charger network: 25 states with awarded NEVI contracts/agreements and 15 states with at least one operational NEVI-funded station by the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2024.

However, we found that the performance indicators in the agency priority goal reports—which FHWA considers to be performance goals—do not fully measure progress toward the program’s purpose established under the IIJA. The fiscal year 2024 progress reports identified performance indicators related to data collection (52 states using EV-ChART)—an effort in which FHWA coordinates with the Joint Office—and reliability (reducing the percentage of unavailable charger ports to less than 1.7 percent).[69] However, neither of these performance indicators clearly state a time frame for completion, and the reliability indicator applies to public chargers broadly, not just NEVI-funded chargers. Therefore, these indicators do not serve as near-term performance goals for NEVI. In addition, FHWA has not established performance goals that would measure the progress of NEVI in facilitating access to electric vehicle chargers, one of the statutory purposes of NEVI. Facilitating access could include improving access to chargers in rural areas or underserved communities. As such, there is no benchmark against which FHWA can compare progress in fulfilling these purposes.

For CFI, FHWA has defined long-term outcomes but has not defined performance goals. FHWA officials told us CFI’s long-term outcomes are established in the IIJA and in CFI’s funding announcement. The statutory purpose of CFI is to strategically deploy publicly accessible electric vehicle charging infrastructure, among other alternative fueling infrastructure, along AFCs or in certain other locations that will be accessible to all drivers of electric vehicles and other alternative fuel vehicles.[70] The CFI funding announcement identified six other long-term outcomes of the program, such as lowering transportation costs and reducing vehicle-related emissions.

However, FHWA has not defined near-term performance goals for CFI that would allow it to measure progress toward achieving the long-term outcomes. When asked about performance goals for CFI, FHWA officials told us the goals for CFI were rolled into the agency priority goal and related milestones and reporting. However, based on our review, the agency priority goal reports did not identify measurable targets specific to CFI. Moreover, the agency priority goal aggregates all public electric vehicle chargers, regardless of funding source, so it does not serve as a clear measure of CFI’s progress.

Collect performance information. FHWA, in coordination with DOE and the Joint Office, has collected performance information for NEVI in alignment with this key practice. FHWA officials identified the agency priority goal and related reports as the primary means by which FHWA tracked the progress of NEVI. As such, officials said they collected performance information for NEVI. We found that the agency priority goal progress reports included some performance information on the status of NEVI, such as the number of states with operational NEVI stations and the number of states using EV-ChART. Those reports use data collected via the Alternative Fueling Station Locator, which is updated on an ongoing basis and tracks the number and location of operational NEVI-funded chargers. Also, the Joint Office collects data, including reliability data, on NEVI-funded chargers via EV-ChART. FHWA officials also told us the Joint Office monitors several metrics for NEVI progress, including the contract status for each state.

FHWA, in coordination with DOE and the Joint Office, has used similar methods to collect performance information for CFI. FHWA officials told us they used the agency priority goal reports to track the progress of CFI, including by noting how many grant agreements have been completed. Similarly, the Alternative Fueling Station Locator tracks the number and location of operational CFI-funded chargers. The Joint Office also collects data from CFI recipients via EV-ChART.

Use performance information. FHWA, in coordination with DOE and the Joint Office, has taken actions to assess the progress of NEVI, but not fully in relation to defined performance goals. In December 2024, FHWA officials identified the fiscal year 2024 agency priority goal as the primary means by which it has assessed the progress of NEVI. The progress reports for the agency priority goal—the most recent of which was issued in January 2025 and covered the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2024—included a narrative providing an update on NEVI activities and the status of various milestones. The reports also note the updated values of various performance indicators. In addition, Joint Office officials told us that they have begun using EV-ChART data to assess NEVI progress and made some summary data publicly available on their website. In addition, the Joint Office produced two annual NEVI reports that provided an overview of NEVI progress, including discussing states’ NEVI plans and the status of the charging network.[71] However, without fully defined performance goals for the purposes of NEVI established under the IIJA, FHWA, in coordination with DOE and the Joint Office, has not been able to measure progress in fulfilling those purposes, such as facilitating access to electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

Similarly, FHWA, in coordination with DOE and the Joint Office, has taken actions to assess the progress of CFI, although not in relation to defined performance goals. FHWA officials stated that they used the agency priority goal reports to assess the progress of CFI. These reports included a narrative describing recent CFI activities (e.g., status of the CFI grant agreements) and multiple milestones associated with CFI (e.g., announcement of CFI awards). In addition, Joint Office officials told us that they have started analyzing data from CFI funding recipients collected via EV-ChART. However, without defined performance goals, FHWA is not fully able to compare the progress of CFI with desired results in the near term.

While FHWA, along with DOE and the Joint Office, has focused on the agency priority goal and related reporting, it has not fully defined performance goals for NEVI and CFI. Without doing so, FHWA might be limited in its ability to assess the progress of these federal programs toward desired results and long-term outcomes. Assessing progress is particularly important because these federal investments are intended to achieve specific outcomes—such as improving access to chargers—and not just to increase the number of chargers in the country. Assessing progress toward performance goals could also help FHWA, along with DOE and the Joint Office, determine any additional steps they may need to take to achieve further progress. Moreover, as the entities review these programs, implementing a performance management framework could help better inform the public and decision-makers, including Congress, of the effectiveness of federal investments.

Conclusions

With the number of electric vehicles on the road continuing to grow, DOE, DOT, FHWA, and the Joint Office have collaborated to provide support for building the national electric vehicle charging network through grant programs like NEVI and CFI. These programs’ activities were under review as of May 2025. Fully implementing performance management frameworks that define and assess progress toward performance goals would help the Joint Office and FHWA better understand the results of their efforts and determine any additional steps needed to achieve desired outcomes. Moreover, performance goals and assessments would help FHWA establish expectations for federal programs supporting public electric vehicle charging infrastructure and demonstrate results to help Congress and the public better understand these investments.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of three recommendations, including one to the Joint Office and two to DOT. Specifically:

The Executive Director of the Joint Office should fully implement a performance management framework that defines and assesses progress toward performance goals. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Transportation should direct the FHWA Administrator to fully implement a performance management framework for NEVI that defines and assesses progress toward performance goals. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Transportation should direct the FHWA Administrator to fully implement a performance management framework for CFI that defines and assesses progress toward performance goals. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOE, the Joint Office, and DOT for review and comment. The Director of the Office of Financial and Audit Management at DOE—responding for both DOE and the Joint Office—and the Director of Audit Relations and Program Improvement at DOT each provided an email responding to our draft report. In the emails, DOE, the Joint Office, and DOT did not take a position on our recommendations. DOT provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation, the Executive Director of the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation, the Secretary of Energy, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at RepkoE@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Elizabeth Repko

Director, Physical Infrastructure

For this report, we (1) evaluated the extent to which federal agencies’ efforts to advance electric vehicle charging infrastructure have aligned with leading practices for collaboration; (2) identified the challenges states and other stakeholders have faced in implementing federal electric vehicle charging infrastructure programs, and actions the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (Joint Office) has taken to support stakeholders; (3) evaluated the extent to which the Joint Office’s assessment of its activities has aligned with key performance management practices; and (4) evaluated the extent to which the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) assessment of federal programs supporting public electric vehicle charging infrastructure has aligned with key performance management practices.

To evaluate the extent to which federal agencies—specifically, the Department of Energy (DOE), Department of Transportation (DOT), FHWA, and the Joint Office—have collaborated to advance electric vehicle charging infrastructure, we reviewed the agencies’ collaboration efforts for alignment with leading collaboration practices identified in our prior work.[72] We reviewed relevant documentation and interviewed officials from DOE, DOT, FHWA, and the Joint Office on their efforts to provide technical assistance and implement the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program (NEVI) and Charging and Fueling Infrastructure Discretionary Grant Program (CFI), among other joint activities.

For the analysis, we used a three-point scale to determine whether the federal entities’ efforts generally aligned, partially aligned, or were not aligned with the leading practices. For those leading practices where evidence described federal actions that reflected elements of the practice to a large or full extent, we determined the activities generally aligned with the leading practice. For those leading practices where evidence described federal actions that reflected some, but not all, elements of the practice, we determined the activities partially aligned with the leading practice. For those leading practices where evidence demonstrated that federal actions did not reflect, or minimally reflected, elements of the practice, we determined the activities were not aligned with the leading practice.

To identify challenges states and other stakeholders have faced in implementing federal electric vehicle charging infrastructure programs, we interviewed eight national organizations, five regional electric vehicle charging groups, five state DOTs, three CFI grant recipients, and two private sector entities. See below for a list of the entities we interviewed for this report. We conducted these stakeholder interviews in 2023 and 2024, before issuance of (1) the January 2025 executive order pausing the disbursement of funds appropriated through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and (2) the February 2025 FHWA letter to state DOT directors rescinding the current and prior versions of NEVI guidance.[73]