HEALTH CARE TRANSPARENCY

CMS Needs More Information on Hospital Pricing Data Completeness and Accuracy

Report to the Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives

October 2024

GAO-25-106995

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106995. For more information, contact Leslie V. Gordon at (202) 512-7114 or GordonLV@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106995, a report to the Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives

October 2024

Health Care Transparency

CMS Needs More Information on Hospital Pricing Data Completeness and Accuracy

Why GAO Did This Study

Rising prices for hospital services have contributed to a nearly 50 percent increase in private health plan spending from 2012 through 2022. In response to a statutory requirement intended to help lower costs, CMS began requiring hospitals to post their prices in 2021. In 2024, CMS updated its requirements to address some challenges with using the pricing data.

GAO was asked to review CMS’s implementation of hospital price transparency requirements. In this report, GAO (1) describes users’ experiences with hospital pricing data prior to CMS’s 2024 updates; (2) describes the 2024 updated requirements; and (3) examines CMS’s enforcement of the requirements.

GAO reviewed relevant laws and regulations; CMS documentation; relevant studies; and comments on CMS’s updated 2024 requirements. GAO analyzed CMS enforcement actions taken against hospitals from 2021 through 2023. GAO also interviewed officials from CMS, the American Hospital Association, and 16 stakeholder organizations representing data users, including health plans, patients, and researchers. GAO selected these stakeholders based on their knowledge of hospital pricing data use, among other factors.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making one recommendation for CMS to assess whether hospital pricing data are sufficiently complete and accurate to be usable, and to implement any additional enforcement activities as needed. The Department of Health and Human Services agreed with the recommendation.

What GAO Found

In 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented a statutory requirement for hospitals to publicly post their prices. Hospitals have historically provided limited pricing information. By making them post a file with prices on their websites, CMS intends to make information available that could be used to help increase competition and thereby lower prices. For example, pricing data could help health plans negotiate prices more effectively.

Various challenges have limited the usability of hospital pricing data, according to 16 selected stakeholders representing users of the data, such as health plans and researchers. Describing experiences prior to CMS’s 2024 updates to the requirements, stakeholders told GAO that inconsistent file formats, complex pricing, and perceived incomplete and inaccurate data have impeded price comparisons across hospitals and prevented large-scale, systematic data use.

CMS updated price transparency requirements for 2024 to address some of the challenges with using hospital pricing data. For example, CMS required hospitals to post pricing data using a standardized file format as of July 1, 2024. CMS also required hospitals to affirm the completeness and accuracy of their data.

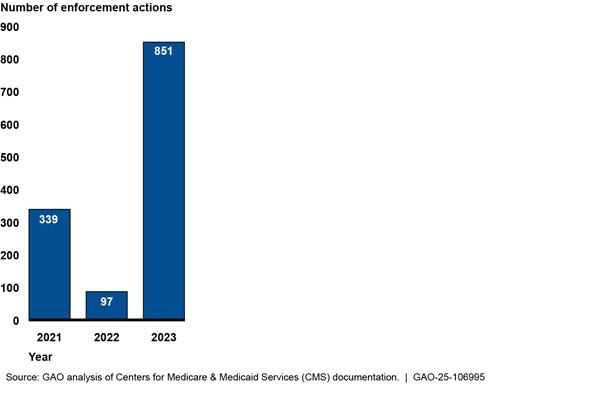

CMS checks whether hospitals have included information for the required data points and takes enforcement actions against hospitals that do not comply, such as issuing warning notices detailing compliance deficiencies to be corrected. CMS initiated 1,287 enforcement actions from 2021 through 2023, with 851 of the actions initiated in 2023. As part of these enforcement actions, CMS issued over $4 million in civil monetary penalties to 14 hospitals that did not take timely corrective action.

However, CMS does not have assurance that pricing data hospitals report are sufficiently complete and accurate, and CMS has not assessed such risks to determine if additional enforcement actions are needed. Without an assessment, CMS does not know whether the data are usable to help increase competition. While CMS officials stated that they do not have the resources to check the accuracy and completeness of all hospital pricing data, the agency has cost-effective enforcement options it could consider, if needed, such as using risk-based or random sampling.

Abbreviations

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

October 2, 2024

The Honorable Cathy McMorris Rodgers

Chair

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

Health care prices—including prices for hospital services—are higher and have been rising more quickly, on average, for private health plans compared to the prices paid by public health insurance programs in the U.S., according to the Congressional Budget Office. The growth in prices has been a key driver of increased health care expenditures in the U.S., raising spending on hospital services, the premiums paid by employers and individuals for private health care coverage, and federal subsidies for private health care coverage.[1] From 2012 through 2022, private health plan expenditures increased by nearly 50 percent, from $878 billion to $1,290 billion, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).[2]

These rising prices also affect most Americans. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2022, about 217 million people—or around 66 percent of individuals in the U.S.—had health care coverage through private health plans.[3] About 180 million of these people received their coverage through a health plan offered by their employer, and most of the remaining individuals purchased coverage directly from health plans. In addition, about 26 million individuals were without health insurance in 2022. Another study has indicated that hospital prices for individuals without health insurance are, on average, generally comparable to the prices for private health plans.[4]

Hospitals have historically provided limited information on their prices, and had previously considered the prices that they negotiate with private health plans as proprietary.[5] However, in response to the high and increasing prices of hospital services, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act required hospitals to make their “standard charges”—which we refer to as prices or pricing information—available to the public.[6] It also required the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to develop requirements for enforcing hospital compliance.[7] CMS—a federal agency within HHS—began requiring hospitals to make the prices for their services publicly available on their websites beginning January 1, 2021.[8]

Specifically, CMS requires hospitals to post on their websites (1) a comprehensive machine-readable file listing the prices for all of their items and services, including health plan-specific negotiated prices, and (2) a patient-friendly list of prices for “shoppable” services that a patient can schedule in advance, such as a colonoscopy.[9] By requiring hospitals to report their prices, CMS intends to make information available to various users—including health plans, employers, and patients—that could facilitate increased market competition and thereby help lower prices for hospital services.

Since CMS implemented hospital price transparency requirements in 2021, various stakeholders have raised questions about the usability of hospital pricing data. In addition, CMS and others have raised concerns with hospital noncompliance with hospital price transparency requirements, including identifying hospitals that have not posted their prices at all, or have not posted all required prices. In a 2023 journal article, CMS officials estimated that in February 2021, 27 percent of hospitals were in full compliance with both the machine-readable file and shoppable services requirements, and that 70 percent were in full compliance in November 2022.[10] In response to stakeholder feedback, CMS issued a final rule in November 2023 that implemented a number of updated requirements in 2024.[11]

You asked us to review CMS’s implementation of hospital price transparency requirements. In this report we

1. describe users’ experiences with hospital pricing data prior to CMS’s updates to price transparency requirements in 2024;

2. describe the 2024 updates made by CMS to hospital price transparency requirements and compliance processes; and

3. examine CMS’s enforcement of hospital price transparency requirements.

To describe users’ experiences with hospital pricing data prior to CMS’s updates to price transparency requirements in 2024, we interviewed 16 stakeholder organizations that represent users of hospital pricing data or have relevant subject matter expertise on the use of hospital pricing data. These stakeholders included organizations representing insurers, employers, health benefit consultants, and patients; data vendors that have downloaded and aggregated hospital pricing data; and health care research organizations.[12] We selected these stakeholders on the basis of our review of relevant studies and articles; submission of comments on CMS’s 2024 proposed rule to update hospital price transparency requirements; participation in an expert panel on hospital price transparency; and a “snowball” methodology in which those we interviewed referred us to other relevant stakeholders.[13]

The views expressed by the stakeholders are not generalizable to other users, but provide insights into user experiences with hospital pricing data.[14] Further, we conducted these interviews prior to CMS’s implementation of a number of updated requirements in 2024 meant to address some of the challenges experienced by users of the data. To obtain hospital perspectives on hospital price transparency, we also interviewed officials from the American Hospital Association. In addition to interviews, we also reviewed relevant studies and articles and comments on CMS’s 2024 proposed rule on hospital price transparency to further our understanding of user experiences with hospital pricing data.

To describe 2024 updates made by CMS to hospital price transparency requirements and compliance processes, we reviewed relevant laws, CMS’s 2024 proposed and final rules for updating hospital price transparency requirements, and relevant agency documents, including guidance for hospital price transparency compliance. We interviewed CMS officials about the updates and how they may address usability concerns and further facilitate the use of hospital pricing data. We also reviewed public comments on CMS’s 2024 proposed rule for updating hospital price transparency requirements, and interviewed the relevant stakeholder organizations identified above to obtain their perspectives on the extent to which the updates would further facilitate the usability of hospital pricing data.

To examine CMS’s enforcement of hospital price transparency requirements, we reviewed CMS documentation on agency processes for identifying and prioritizing hospitals for compliance assessments and for determining hospital compliance, including agency manuals and compliance checklists. We also interviewed CMS officials regarding these processes. We reviewed CMS documentation as of May 2024—the most recent available at the time of our analysis—for enforcement actions initiated against hospitals for noncompliance in 2021 through 2023.[15] For this report, our count of initiated enforcement actions was based on the number of times that CMS initiated a group of related actions against a hospital. CMS counts enforcement actions differently, based on the number of notices and penalties issued.[16]

As part of our review of agency enforcement of hospital price transparency requirements, we assessed CMS activities to help ensure the completeness and accuracy of hospital pricing data in light of CMS’s goal to make information available that could help to increase competition and lower prices through price transparency. To do so, we compared CMS activities to federal internal control standards for responding to program risks.[17] In particular, we determined that the risk assessment component of internal control was significant to our objective, including the underlying principle that federal agencies should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving agency objectives. We also reviewed how other CMS programs respond to risks related to the completeness and accuracy of provider reported data.[18]

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to October 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Hospital Machine-Readable Pricing Data

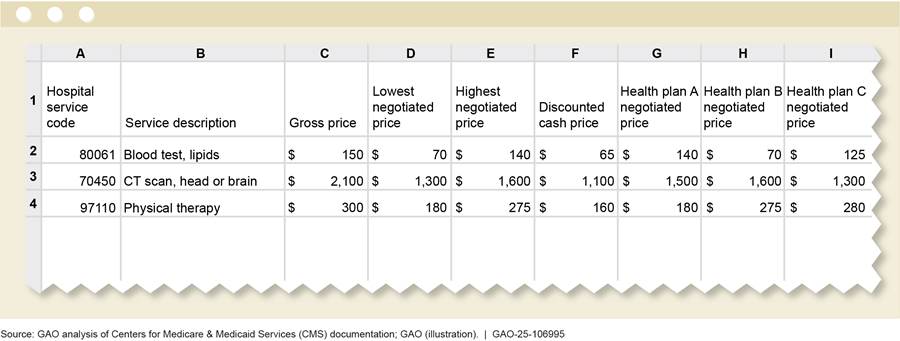

Since 2021, CMS has implemented a regulation that requires hospitals to annually post their prices in machine-readable files on their websites.[19] The machine-readable files are required to meet certain accessibility requirements, such as easy online access, and include certain data elements, including applicable billing codes and descriptions of the items and services covered by the prices. In addition, the machine-readable files must provide data on five types of prices for all applicable items and services provided by the hospital:

1. Gross price: the hospital’s list price, absent any discounts. Few health plans or patients pay the gross price, though it may serve as a reference price for discounts that are applied to generate other types of prices, such as discounted or negotiated prices.

2. Discounted cash price: the hospital’s price that applies to an individual who pays cash, such as self-paying patients without insurance.

3. Plan-specific negotiated price: the price that the hospital has negotiated with each contracted health plan.

4. The de-identified minimum negotiated price: the lowest price that a hospital has negotiated across all health plans.

5. The de-identified maximum negotiated price: the highest price that a hospital has negotiated across all health plans. The minimum and maximum negotiated prices may allow users to easily find the lowest and highest price that a hospital has negotiated for a particular service (see fig. 1 for an example of a machine-readable file).[20]

Note: The figure is a simplified version of a hospital machine-readable file for the purposes of this report, and does not include several required data elements, such as service setting (inpatient, outpatient, or both), and service code type (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes, etc.). Under statute and CMS regulations, hospitals are required to post their “standard charges.” We use the term “price” in this figure in lieu of “standard charges” for the sake of simplicity.

CMS requires hospitals to make their pricing data public in machine-readable files to make information available that could help increase market competition and lower prices through price transparency. Such data may better enable potential users—including insurers, employers, third-party administrators, and health care benefit consultants and data vendors—to provide better value health care coverage through increased market competition. See table 1 for the roles that these users play in offering health plans and how they may use hospital pricing data.[21]

|

User |

Role |

Potential use of hospital price transparency data |

|

Insurers |

Offer health plans to individuals or groups; the insurer collects premiums and helps pay for medical expenses. |

More effectively negotiate the prices for services with hospitals and develop better value provider networks.a |

|

Third-party administratorsb |

Provide health plan administration services to employers offering self-insured health plans, including developing provider networks and negotiating the prices for provider services, such as hospital services. |

More effectively negotiate the prices for services with hospitals and develop better value provider networks. |

|

Employers |

May purchase group health plan coverage from insurers, on behalf of employees, or may offer self-insured health plans for employees. |

Better advise or oversee the effectiveness of their health insurer or third-party administrator in negotiating prices and developing better value networks. |

|

Health care benefit consultants and data vendors |

Provide pricing data and analysis to insurers, third-party administrators, and employers. |

Help insurers, third-party administrators, and employers more effectively negotiate prices and develop provider networks. |

Source: GAO. I GAO‑25‑106995

Note: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services identified a number of other potential users of machine-readable file data, including researchers, policymakers, and IT firms that could use the data to develop price transparency tools, consumer apps, or integrate the data into electronic health record IT systems.

aHealth plans establish provider networks—hospitals, doctors, and other providers with which a plan contracts—to provide medical care to their enrollees.

bHealth insurance companies may also provide third-party administrator services for self-insured employer plans. While insured plans collect premiums and pay for beneficiary medical expenses, third-party administrators only offer administration services. Employers that use third-party administrators collect premiums from their employees and take on the responsibility of paying employees’ and dependents’ medical expenses.

The prices that health plans pay hospitals for services generally are higher than the prices paid by public programs, such as Medicare, and can vary substantially across and within geographic areas, according to the Congressional Budget Office.[22] In certain instances, health plans may be able to negotiate relatively lower prices based on hospitals’ participation in provider networks.[23] However, certain hospitals may be able to negotiate more favorable prices with health plans when those hospitals are essential to develop a local provider network. While plans may try to negotiate lower prices by excluding or proposing to exclude certain hospitals from their networks, in many cases, their ability to do so may be limited depending on the plans’ and hospitals’ relative market power.[24]

With hospital pricing data being made public—specifically their negotiated prices with health plans—health plans may have greater ability to negotiate with hospitals and lower prices.[25] For example, health plans could use the pricing data to identify hospitals with lower prices to develop better value provider networks.[26] Additionally, health plans could use hospital pricing data to identify lower prices that have been negotiated by other health plans with specific hospitals, and then use the data as a basis for negotiating lower prices for themselves with those hospitals.[27]

Employers could also use hospital pricing data to better advise or oversee the effectiveness of their insurer or third-party administrator in negotiating prices and developing better value provider networks. The Congressional Budget Office has reported that health plans may have limited incentives to negotiate lower prices with hospitals, in part because they can often pass any increased prices on to employers and enrollees through increased premiums.[28] Further, employers have historically not been able to obtain data about the prices for hospital services negotiated on their behalf and therefore, could not assess the effectiveness of their health plans. With publicly available data on hospitals’ negotiated prices, employers could potentially use the data to more easily compare their plan’s negotiated prices against prices offered by competing plans, or push their plans to develop provider networks that steer their employees to better value hospitals, among other potential uses.

While making pricing information available could help increase competition, and thereby lower prices, a 2022 report by the Congressional Budget Office anticipated that increased health care price transparency would lead to “very small” price reductions. The report states that the high prices health plans pay for hospital and physician services result from several factors, primarily the relative market power of many health care providers.[29]

Shoppable Services Pricing Data

Patients have historically had limited access to hospital pricing information to comparison shop for services. In 2011 and 2014, we reported on the challenges patients face in obtaining and using health care pricing information.[30] However, since 2021, CMS has also required hospitals to post on their websites a patient-friendly display comprising at least 300 “shoppable” services—nonemergency services that can be planned in advance, such as colonoscopies or knee surgeries. Hospitals can satisfy this requirement by displaying prices for the shoppable services, or by offering an easily accessible online price estimator tool that provides patients with personalized, real-time estimates of their out-of-pocket costs.

By making hospital prices available to patients, CMS has indicated that it intends to better facilitate patients’ ability to comparison shop and choose better value hospitals for nonemergency services. Such comparison shopping could particularly benefit patients who are uninsured or who have high-deductible health plans, because they generally face higher out-of-pocket costs for higher priced services compared to those who are insured.[31] Further, if hospital comparison shopping by patients were to become more common, hospitals may be incentivized to lower their prices to attract patients.

Health Plan Price Transparency

In addition to establishing hospital price transparency requirements, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act also established price transparency requirements applicable to certain health plans.[32] For example, since January 2022, CMS has required certain health plans, such as group plans, to publicly disclose machine-readable files containing price information, such as the prices that they negotiate with health care providers in their networks, including hospitals and non-hospital providers.[33] In addition, since January 2023, certain plans have also been required to maintain an internet-based self-service tool that allows beneficiaries to obtain their out-of-pocket costs for items and services.[34]

Selected Stakeholders Identified Challenges Limiting Usability of Hospital Price Transparency Data Prior to CMS’s 2024 Requirements

Selected Stakeholders Cited Technical Challenges, Complex Pricing, and Perceived Incomplete and Inaccurate Data as Challenges to Using Data Prior to CMS’s 2024 Requirements

Stakeholders we interviewed generally reported three types of user challenges when accessing and using hospital pricing data to help lower health care costs prior to CMS’s updated requirements. These challenges include (1) technical challenges; (2) the complexity of hospital pricing data; and (3) missing, and perceived incomplete and inaccurate data.

Technical challenges with machine-readable files. According to many stakeholders we interviewed, technical challenges with files’ location, size, and formatting, and inconsistent reporting of data elements impeded the accessibility and usability of the hospital machine-readable files.[35] These technical challenges hindered the ability of users to compare prices across hospitals, according to stakeholders. For example:

· Location and size. Many stakeholders told us that hospital machine-readable files were not easy to locate online, and that, in their experience, hospitals have not always posted files on a publicly available website in an easily accessible manner. For example, one stakeholder noted that some hospitals have required additional steps to access and use them, such as using a password to download the files. When the files were available, some were large and unwieldy, and difficult to work with according to some stakeholders. For example, one stakeholder described how several hospitals’ files included repetitive data that made the file excessively large, which caused an incomplete file download.

· Formatting. Many stakeholders told us that users faced challenges locating prices for services and comparing them across hospital files due to a lack of a standard file format and structure. For example, one stakeholder said that each hospital may choose its own unique way to develop and populate the file (e.g., one hospital may populate columns, another may use rows), resulting in files that cannot be readily analyzed and compared across hospitals.

· Disparate reporting of data elements. Many stakeholders noted that hospitals have disparate ways of reporting the required data elements. These include how hospitals identify the health plans associated with their prices, or the items and services they provide. According to these stakeholders, the inconsistent reporting of data elements limited the ability to match services and prices across different hospitals. For example, one stakeholder said there was no consistency and standardization for text descriptions of hospital services, and sometimes hospitals did not include the billing codes, as required, which created challenges identifying and comparing services or prices across hospitals. Some stakeholders said that hospitals did not clearly identify which health plans were associated with plan-specific negotiated prices, rendering comparisons of health plans’ negotiated prices across different hospitals challenging.

Complexity of pricing data. Many stakeholders also reported challenges interpreting the data in the machine-readable files and comparing prices across hospitals due to the inherent complexity and variation in how hospitals price their services. For example, stakeholders noted the following:

· Hospitals establish their prices by using different units of service that are not always easily comparable. For example, some hospital prices may apply to an entire service episode—which may span multiple days of care, while other prices may represent per diem (daily) charges. In other cases, the prices may represent a base price for a procedure and related services are priced as additional line items.[36]

· Hospital prices for a service may lack contextual information that may affect the ultimate price of a service, such as the service setting (e.g., inpatient or outpatient), type of provider fee (e.g., hospital facility fee or professional fee), severity of patient condition, or patient health-related factors, such as age or comorbidities, according to some stakeholders.[37]

· Hospitals may develop their plan-specific negotiated prices using distinct and unique approaches, such as applying varying adjustment factors, or deriving a service price from a percentage of a reference price based on a formula or algorithm. For example, a plan-specific negotiated price for a service could be a percentage of the hospital’s total gross charges for certain services, rather than a set dollar amount that would apply to each patient.

Missing, and perceived incomplete and inaccurate data. Missing hospital pricing data in the machine-readable files has been a challenge to the usability of the data, according to many stakeholders; some stakeholders also noted perceived incomplete or inaccurate hospital pricing data in the machine-readable files. Many of them told us that, at first, some machine-readable files were missing from hospital websites as numerous hospitals did not comply with the requirement to post them, although some stakeholders observed subsequent improvements. Additionally, some stakeholders said hospitals’ posted files would sometimes contain cells left blank or prices marked “n/a” if the hospitals’ negotiated price for an item or service was not in a standardized dollar amount.[38] In other instances, hospitals did not include prices for all five required price types, or did not post prices for all services offered, or for all applicable health plans, according to some stakeholders.[39] In addition, these stakeholders cited concerns with prices they perceived to be clearly inaccurate, including services priced at very low or unusually high amounts, such as knee replacement procedures priced at over $1 million.

Because of the usability challenges with the hospital pricing data, many stakeholders said that users have relied on data vendors that process, standardize, and aggregate hospital pricing data to make it more usable and meaningful. Some stakeholders we interviewed told us that data vendors employed coding techniques and other methodologies to process, clean, and standardize hospitals’ data in a format that allows comparison of prices across different hospitals. The data vendors we interviewed also told us that they used a variety of approaches to address some of the challenges associated with hospitals’ complex pricing structures. For example, representatives of one data vendor said they may use external data to help make prices across hospitals more comparable, such as using data on the average length of patient hospitalization for a given service to make per diem prices more comparable with prices that cover an entire episode of care.

Stakeholders Cited Limited Use of Hospital Data, but Said Future Improvements to Address Challenges Could Increase Use

Many stakeholders we spoke with told us that the usability challenges associated with hospital machine-readable files prior to the 2024 requirements have so far prevented large-scale, systematic use of the data to compare hospital prices and to help negotiate lower prices for hospital services. However, some stakeholders cited anecdotes of hospital pricing data being used in a limited, ad hoc manner by plans and employers trying to lower their health plan costs. For example, some of these stakeholders told us that some plans have used the data to identify instances in which their negotiated prices were significantly higher relative to other plans, and then used the data to help negotiate lower prices.

While the use of hospital price transparency data has been limited so far, many stakeholders we interviewed noted that they expect use to increase over time if the data usability challenges are overcome or addressed. Further, some stakeholders also noted that it will take health plans and employers time to figure out how to effectively use the pricing data as part of their price negotiations and their efforts to develop networks of health care providers.

Many stakeholders we spoke with also noted that they envision using hospital price transparency data in conjunction with other sources of data on plan-negotiated prices, such as insurer price transparency data. For example, two of the data vendors we interviewed use hospital and insurer data together, to complement and validate one another, and plan to comingle hospital and insurer data in developing aggregated negotiated price datasets.

Some stakeholders also noted that hospital pricing data may be used in litigation related to employer oversight of the effectiveness of their third-party administrators. For example, in one lawsuit, an employer compared hospital pricing data against a health plan’s claims data to allege that its third-party administrator did not pass along negotiated price discounts to the employer as it should have.[40] These stakeholders said that employers that do not use price transparency data as part of actively overseeing their third-party administrator may also leave themselves open to litigation from their employees for not ensuring that the third-party administrator is negotiating fair prices and properly administering the health plan.

Stakeholders Cited Limited Patient Interest in Hospital Shoppable Services Pricing Information

Patients rarely use hospital shoppable service pricing information or hospital online price estimators that can provide an estimate of an individual’s out-of-pocket costs, according to many stakeholders we interviewed. This assessment is consistent with findings from two studies we reviewed that found few patients shop online to research the price of a hospital service.[41] Some stakeholders told us patients rely on provider referrals for decision-making about hospital services or prioritize the expected quality of provider care rather than the prices for services. Patients may be particularly motivated to prioritize the expected quality of provider care over cost, for example, if they require treatment or surgery for a life-threatening or serious condition, according to one stakeholder.

Further, insured patients may not be price-sensitive to the total price of hospital services because of the structure of their health plan, according to some of these stakeholders. For example, patients often pay a set copayment amount for hospital services at hospitals in their plans’ network, regardless of the total price of the services, and would therefore have little incentive to use hospital shoppable service information, according to one stakeholder.[42] Another stakeholder said prices provided by hospitals do not necessarily account for patient health plan information such as deductibles and copayment amounts that affect out-of-pocket costs, or to what extent the patient has met their deductible. In addition, according to some stakeholders we interviewed and representatives of the American Hospital Association, price estimator websites run by patients’ insurers may be more effective in helping insured patients shop for services, because insurer websites generally include more precise estimates of out-of-pocket costs based on patients’ health plan benefits, and often provide estimates across multiple hospitals.

Although there was a general consensus among many stakeholders we interviewed that patients do not find shoppable services or online hospital price estimators meaningful, two stakeholders cited limited instances of patients using these sources of pricing information on an ad hoc basis. For example, representatives of a patient advocacy organization told us they use hospitals’ pricing information to help patients appeal and challenge large hospital bills. According to another stakeholder, uninsured patients, in particular, may benefit from using shoppable services information since their costs are not offset by insurance.

CMS Updated Hospital Price Transparency Requirements to Help Address Some Usability Concerns

As part of its 2024 final rule, CMS updated its hospital price transparency requirements to increase the usability of hospital pricing data.[43] Specifically, CMS made the following updates:

Standardization of hospital machine-readable files and data elements. Beginning July 1, 2024, CMS required hospitals to report hospital price data in new standardized CMS machine-readable file template layouts and to conform with other CMS-specified technical instructions. Prior to the use of these templates, hospitals could develop their pricing files without following specific standardized layouts. According to CMS, the agency expects the new standardized file template layouts will enhance user access of the machine-readable files and improve machine readability. CMS also requires hospitals to include an expanded set of standardized data elements to help create context for pricing data, to enhance and improve the meaningfulness of the data, and to make prices more comparable across hospitals. For example, a hospital must display whether a price applies to an inpatient or outpatient setting, or to both.[44]

CMS’s 2024 final rule also implemented a new requirement effective January 1, 2025, for situations in which a hospital’s plan-specific negotiated price cannot be expressed as a dollar amount—because it is established using a percentage or an algorithm, such as a price that is a percentage of the hospital’s total gross charges for certain services. In these situations, hospitals must report a new “estimated allowed amount” based on the average dollar amount that the hospital has historically received from a plan for the item or service, to help provide contextual information.[45] In its guidance related to the implementation of the rule, CMS provided technical instructions for hospitals to display this estimated allowed amount in a standardized manner, and also instructed hospitals to display plan-specific negotiated prices as a dollar amount whenever possible.[46]

CMS officials and some stakeholders told us they expect CMS’s new standard template layouts will help to address some of the usability challenges related to file formats, data elements, and incomplete machine-readable files. However, CMS officials and some stakeholders said they do not expect the updates to address all the usability challenges associated with the complexity of hospital prices, such as comparing prices for services in hospitals that use differing practices for bundling services or have differing units of service. CMS officials said they do not have the authority to regulate how hospitals establish their prices, and accordingly cannot easily address the challenge stemming from varied hospital practices for pricing items and services. However, CMS officials told us that the newly established estimated allowed amount may provide users with better information on prices established from a formula or algorithm.

Improved access to hospital machine-readable files. CMS’s new requirements include changes intended to improve access to hospital machine-readable files. In particular, CMS now requires hospitals to place a “footer” at the bottom of their home pages labeled “Price Transparency” that links directly to the web page hosting their machine-readable files.

CMS stated in the preamble to the final rule that making hospital machine-readable files more easily accessible would help potential users, such as data vendors developing tools that further assist the public in understanding the data and capturing it in a meaningful way for making informed health care decisions. Two stakeholders we spoke with were generally optimistic about the usability benefits of this updated requirement. For example, two data vendors we spoke with stated the requirement that hospitals publish their files at an easy-to-find location on their websites will allow organizations or individuals to locate hospital files quickly and make the files more available and easier to use with automated programs for collecting data at scale.

Accuracy and completeness affirmation statement. As part of CMS’s updated requirements, the agency now expressly requires hospitals to make a “good faith effort” to report accurate pricing data as of January 1, 2024, and to include an affirmation statement regarding the completeness and accuracy of pricing data as of July 1, 2024. CMS stated in the preamble to the final rule that the agency had received public comments and concerns regarding the accuracy and completeness of hospitals’ pricing data in their machine-readable files. For example, a hospital’s file may contain blank cells or cells containing “n/a,” which has caused confusion among potential users. CMS subsequently stated that when a hospital leaves a field blank or inserts “n/a,” an affirmation about the hospital’s file’s accuracy and completeness would help remove ambiguity about whether the blanks represent missing data or whether applicable services are not provided by the hospital.[47] CMS also noted that an affirmation would help streamline CMS assessments of hospital compliance.

Some stakeholders we spoke with stated they view this affirmation requirement as an initial step toward improving accuracy and completeness, but that an affirmation is not a robust enough control to better ensure hospitals provide complete and accurate data. Later in this report we discuss CMS’s enforcement actions, including those related to accuracy and completeness.

Additional capabilities to help ensure data completeness and accuracy. As part of the updated requirements to improve and enhance enforcement, as of January 1, 2024, CMS can require an authorized hospital official to certify the accuracy and completeness of pricing data in the hospital’s machine-readable file. CMS differentiates a certification from the more general affirmation statement because it would be signed by an authorized hospital executive as part of a specific CMS enforcement effort.[48] As such, CMS officials told us that it would help CMS resolve any specific questions related to a hospital’s prices for items and services.

In the updated regulations, CMS also identified additional activities the agency may use to monitor and assess hospital compliance, including by requiring hospitals to provide supporting documentation to validate the completeness and accuracy of their pricing data. For example, CMS officials told us that if CMS receives a credible complaint alleging that the hospital is not posting prices established by the hospital or that the prices are not accurate, CMS has authority to investigate the allegation and take an enforcement action against the hospital if the allegation proves to be true. Further, CMS noted in the preamble to the final rule the agency may require hospitals to submit documentation of their prices so that CMS can validate prices in the posted hospital pricing files.

CMS Has Taken Enforcement Actions but Does Not Have Assurance That Pricing Data Are Sufficiently Complete and Accurate

CMS Enforcement Prioritized Public Complaints to Identify Potential Noncompliance with Price Transparency Requirements

Prior to implementing CMS’s 2024 requirements, agency officials told us that they prioritized public complaints of noncompliance with hospital price transparency requirements to identify hospitals for review and potential enforcement action. While CMS also has the ability to self-initiate audits of hospital websites and reviews of hospital compliance, CMS officials told us that they believed prioritizing complaints was the most effective approach to target reviews on hospitals at higher risk for noncompliance.[49] According to CMS documentation, CMS’s enforcement followed these steps:

· Identification. CMS used public complaints submitted through CMS’s website to identify potential hospital noncompliance with price transparency requirements. CMS reviewed and scored the complaints to prioritize hospitals for review. CMS prioritized complaints of more serious potential deficiencies, such as hospitals that do not post machine-readable files, or those with multiple complaints.

· Reviews. Once a hospital was selected for review, CMS used checklists to verify hospital compliance with selected price transparency requirements. For example, CMS checked that hospital machine-readable files contained all five types of required prices for applicable items and services provided by the hospital, contained item and service billing codes and descriptions, and met certain accessibility criteria.

· Enforcement actions. When CMS identified deficiencies with hospital price transparency requirements, the agency generally issued a warning notice detailing the noncompliance and instructing the hospital to address the noncompliance within 90 days. If a hospital did not address the deficiencies in the warning notice, CMS issued a notice requiring the hospital to develop a corrective action plan.[50] Beginning in April 2023, CMS required hospitals to submit a corrective action plan within 45 days of CMS’s corrective action plan notice, and to address any noncompliance within 90 days of CMS’s notice.[51] If a hospital was identified as noncompliant or did not submit or comply with a corrective action request as required, CMS issued a civil monetary penalty of up to $5,500 a day depending on the hospital’s size. Once CMS determined that the hospital had taken corrective actions to address all identified deficiencies, CMS closed the enforcement action.

CMS officials told us in December 2023 that they will generally follow these same enforcement processes for the updates to hospital price transparency requirements taking effect in July 2024. In September 2024, CMS officials told us that the agency has updated certain enforcement processes based on the newly implemented transparency requirements. For example, CMS plans to use other approaches in addition to public complaints to identify hospitals for review.

CMS officials also expect the implementation of a standardized machine-readable file will allow for more efficient reviews, and potentially to allow for resource-saving automated reviews to check for compliance with price transparency requirements. According to CMS officials, prior to July 2024, the agency had to use a manual, resource-intensive process to review hospitals’ non-standardized files to check for compliance. CMS also anticipates that the use of standardized template layouts will enable hospitals to more easily comply with price transparency requirements, such as reporting all required data elements. Further, CMS has established a voluntary online validation tool that allows hospitals to check whether their machine-readable files comply with formatting and data specification requirements.[52]

CMS Has Initiated Enforcement Actions Against More than 1,200 Hospitals, with a Significant Increase in 2023

From 2021 through 2023, CMS conducted compliance reviews of 1,746 hospitals and initiated enforcement actions against 1,287, or 74 percent of reviewed hospitals, for noncompliance with hospital price transparency requirements.[53]

In addition, based on our analysis of CMS documentation, we found that that the number of initiated enforcement actions decreased from 2021 to 2022, but significantly increased in 2023, when the agency initiated 851 enforcement actions against hospitals. (See fig. 2). According to CMS officials, the number of initiated enforcement actions decreased from 2021 to 2022 because the agency focused on closing enforcement actions started in 2021 rather than on initiating new enforcement actions. CMS officials attributed the increase in initiated enforcement actions in 2023 to engaging a contractor to aid agency efforts and to implementing a new IT system that helped better track and automate certain review activities. From 2021 through 2023, CMS issued more than $4 million in civil monetary penalties to 14 hospitals that did not take timely corrective actions in response to CMS corrective action plan requests. CMS issued two of the civil monetary penalties in 2022, and 12 in 2023. (See app. I for additional information on enforcement actions by hospital characteristics).

Note: Our count of enforcement actions is based on the number of times that CMS initiated a group of related actions against a hospital. For example, we counted a single initiated enforcement action for a hospital that was issued a warning notice, then issued a corrective action plan request, and then issued a civil monetary penalty. CMS counts enforcement actions differently, based on the number of notices and penalties issued. For example, for a hospital that is issued a warning notice, then issued a corrective action plan request, and then issued a civil monetary penalty, CMS would count three enforcement actions.

Since 2021, CMS has reduced the number of days needed to close enforcement actions—which occurs when CMS determines that hospitals have taken corrective actions on all identified deficiencies. For enforcement actions initiated in 2021 and closed as of May 2024, CMS took an average of 357 days to close the actions. The average number of days to close the actions decreased to 208 for enforcement actions initiated in 2022 and further decreased to 153 for those initiated in 2023.[54] CMS officials attributed the reduced number of days to efficiencies stemming from engaging its contractor for enforcement efforts and from its new IT system, along with establishing specific timeframes for hospitals to take corrective actions. CMS officials also stated that agency outreach efforts to educate hospitals have helped hospitals better understand price transparency requirements and more quickly take corrective actions.

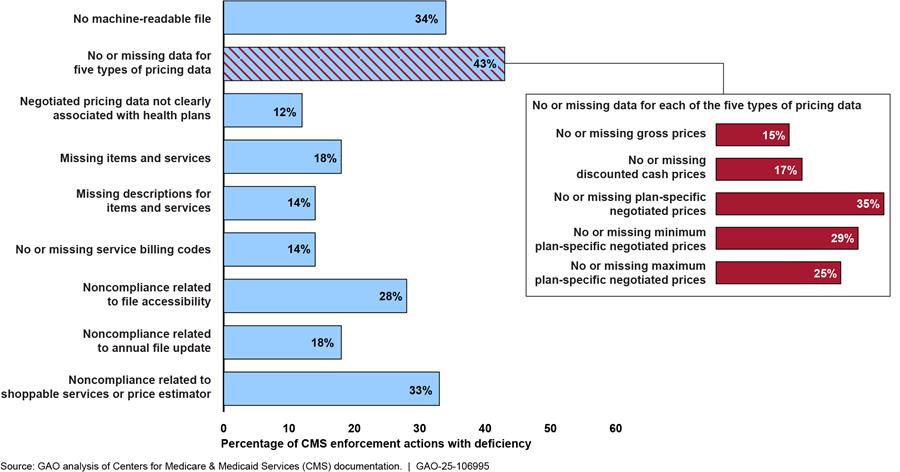

CMS took enforcement actions against hospitals for a range of deficiencies, including hospitals that were not compliant with multiple requirements. For example, some hospitals did not post pricing files at all. Of all CMS enforcement actions initiated from 2021 through 2023 and closed as of May 2024, about one third were taken against hospitals that had not posted a machine-readable file (see fig. 3). In other cases, hospitals posted prices that did not comply with price transparency requirements. More than 40 percent of the enforcement actions in this analysis were associated with hospitals that posted machine-readable files but did not fully provide data for all five types of required prices.[55] Of the hospitals that did not fully provide data for all five types of required prices, the most common deficiency was not posting all plan-specific negotiated prices. Specifically, 35 percent of the CMS enforcement actions were associated with hospitals whose files had no or missing plan-specific negotiated prices.[56]

Notes: This analysis is based on deficiencies cited in enforcement actions against hospitals that CMS initiated from 2021 through 2023 and closed as of May 2024.

Our count of enforcement actions is based on the number of times that CMS initiated a group of related actions against a hospital. For example, we counted a single initiated enforcement action for a hospital that was issued a warning notice, then issued a corrective action plan request, and then issued a civil monetary penalty. CMS counts enforcement actions differently, based on the number of notices and penalties issued. For example, for a hospital that is issued a warning notice, then issued a corrective action plan request, and then issued a civil monetary penalty, CMS would count three enforcement actions.

The reasons associated with hospital noncompliance represent the reasons detailed in the initial notice sent by CMS, in most cases a warning notice. Certain deficiencies may be mutually exclusive; for example, a hospital cited for not posting a machine-readable file would not be cited for deficiencies related to the content of a machine-readable file. In other cases, the reasons for hospital noncompliance may not be mutually exclusive and multiple instances of noncompliance may be cited in CMS enforcement actions. For example, a hospital may be cited for both (1) no or missing pricing data and (2) missing descriptions of items and services.

CMS Does Not Have Assurance That Pricing Data Are Sufficiently Complete and Accurate

CMS’s updates to hospital price transparency requirements are positive efforts toward ensuring the usability of such data. However, CMS does not have assurance that the data hospitals report are sufficiently complete and accurate. CMS officials told us they do not routinely review hospital files to confirm they are complete (i.e., that hospitals are reporting prices on all the services they provide and for all the health plans the hospitals contract with) or that the reported prices are accurate. CMS also does not determine whether any potential problems with completeness and accuracy are compromising the data’s usability.

CMS officials said that the agency is not required by statute to ensure the completeness and accuracy of hospital prices and, due to the amount of data, does not have the resources or capacity to conduct such routine checks on the completeness and accuracy of hospital pricing data. According to CMS officials, the agency’s approach to enforcement of hospital machine-readable files prioritizes ensuring that hospitals comply with basic reporting requirements, such as ensuring the files include data for all five of the required types of prices and corresponding item and service billing codes and descriptions. CMS officials stated that this enforcement approach represents the most effective use of agency resources.

CMS officials indicated that, prior to implementing the updated 2024 requirements, the agency would check hospital machine-readable files for completeness and accuracy, in limited circumstances. For example, as part of its reviews of hospital machine-readable files, CMS searches the files to check that they include prices for certain services, such as prices for certain supplies and procedures, and room and board charges. CMS officials told us that they would also review hospital machine-readable files for completeness and accuracy in response to credible complaints alleging potentially egregious issues as part of its enforcement of price transparency requirements.

In these cases, CMS officials told us that they would ask hospital representatives to clarify potentially incomplete or inaccurate data. For example, CMS would ask hospital officials for clarification regarding whether “n/a” or blank data cells represent services that are not offered or for which prices have not been established, or if the hospital is not reporting a price that should have been included.

According to CMS officials, prior to implementing the 2024 requirements the agency would also take enforcement actions, such as issuing warning notices to hospitals, to address egregiously inaccurate or incomplete pricing data—for example, files that contain an excessive proportion of “n/a” or blank cells. However, CMS officials noted that they have not issued any civil monetary penalties for incomplete or inaccurate data. To verify the accuracy of hospital-reported negotiated prices, CMS officials indicated that the agency would need to obtain documentation of hospital prices.[57] In addition, CMS does not necessarily have information on all the insurers that hospitals contract with, or all the items and services for which a given hospital may have prices.

The use of hospital price transparency data to achieve CMS’s goal to make information available that could help increase competition and lower prices depends on the completeness and accuracy of hospital pricing data, as CMS acknowledges in the 2024 final rule. In response to concerns about the completeness and accuracy of hospital machine-readable files, CMS’s updated 2024 requirements now expressly require hospitals to make a good faith effort to post accurate prices, affirm pricing accuracy in the machine-readable file beginning on July 1, 2024, and provide documentation to validate their pricing data upon CMS request. CMS officials told us the agency does not plan to update the agency’s enforcement activities, which will continue to focus on ensuring that hospital files include required reporting elements.

While the newly required hospital affirmations of completeness and accuracy are a positive step, the risk of incomplete or inaccurate hospital data can affect the usability of the data and compromise the goal of requiring such reporting. CMS has not assessed whether hospital price transparency machine-readable files are sufficiently complete and accurate to support program goals, and accordingly whether additional enforcement actions are needed. According to federal internal control standards, agencies should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving agency goals.[58] Incomplete or inaccurate hospital data pose such risks to CMS’s goal for hospital price transparency. Many of our selected stakeholders have cited incomplete and inaccurate data as a challenge to the usability of the data. Assessing whether the pricing data are sufficiently complete and accurate would help CMS determine if additional enforcement activities are needed to better ensure the usability of the data. Such an assessment could include, for example, soliciting stakeholder feedback on usability or conducting a study of hospital file completeness and accuracy.

If CMS were to determine, based on an assessment, that additional enforcement related to pricing data completeness and accuracy are needed, CMS has options for cost-effective enforcement activities. While determining the completeness and accuracy of all hospitals’ data may not be feasible, CMS would have the ability to pursue enforcement approaches that do not involve a comprehensive review of all the data. For example, other CMS programs use risk-based and random sampling to review the accuracy of provider information to ensure program compliance with limited agency resources. Specifically, CMS’s Quality Payment Program and Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program randomly sample providers, and then review provider documentation for the sample, to verify provider-submitted quality and performance data.[59] The possibility of being selected for such a review can also encourage other hospitals to comply with program requirements.

In addition, if an assessment finds that additional enforcement actions are warranted, another potential strategy could involve comparing hospital-posted negotiated prices against publicly available prices posted by insurers. If CMS identified significant price discrepancies for certain hospitals, then the agency could prioritize these hospitals for further review.

If additional enforcement activities are needed to help better ensure completeness and accuracy, CMS’s updated requirements may create efficiencies that would better allow the agency to engage in such activities. For example, CMS officials told us their updated standardized machine-readable file requirement will allow for more efficient compliance reviews, and potential automation of file reviews.

Without additional information on the completeness and accuracy of hospital pricing data, CMS is not in position to determine whether additional enforcement activities are needed to help better ensure hospital pricing data are usable. Conducting an assessment to determine if the data are sufficiently complete and accurate, and implementing any additional enforcement activities as needed, could help CMS provide assurance that the data reported by hospitals are useful and will support CMS’s program goal to make information available that could promote competition and lower prices through price transparency.

Conclusions

CMS’s updated 2024 hospital price transparency requirements aim to mitigate some of the reported challenges with using pricing data that could help increase competition for hospital services. The agency’s updated requirements to standardize hospital machine-readable files and data elements likely will make it easier for employers, health plans, and others to access and analyze the information.

While CMS generally focuses its reviews of hospitals’ pricing data on ensuring that required data elements are reported, CMS has not assessed the extent to which reported pricing data are sufficiently complete and accurate or whether any related issues jeopardize the usability of the data and CMS’s goal. Stakeholders we interviewed reported perceived issues with the completeness and accuracy of the data.

While confirming the completeness and accuracy of all the hospital pricing data may not be practical, an assessment could help CMS determine if additional enforcement actions are needed to ensure the data’s usability. If CMS were to determine such additional actions are needed, CMS would also have cost-effective options, including the use of risk-based or random sampling. Moreover, CMS expects its 2024 updates to the reporting requirements will simplify and reduce the level of resources needed for the agency’s enforcement activities. Such gains in efficiency could help allow the agency to perform any needed additional enforcement activities to address these risks related to completeness and accuracy of the hospital pricing data. CMS’s assessment and additional enforcement actions, if needed, would help ensure hospital pricing data are usable and contribute to CMS’s goal to make information available that could promote competition and lower prices through price transparency.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Administrator of CMS should assess whether hospital price transparency machine-readable files are sufficiently complete and accurate to be usable for supporting CMS’s program goal and implement any additional cost-effective enforcement activities as needed. Such an assessment could include soliciting stakeholder feedback or conducting a study of hospital file completeness and accuracy. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. HHS provided written comments, which are reprinted in appendix II. HHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

HHS concurred with our recommendation and noted that CMS may conduct an assessment of the prevalence of inaccuracies and incompleteness of pricing data in hospitals’ machine-readable files.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, as well as other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7114 or GordonLV@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Leslie V. Gordon

Director, Health Care

We analyzed Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) documentation of 1,287 enforcement actions initiated against hospitals for noncompliance with hospital price transparency requirements from 2021 through 2023 by hospital characteristics. Our count of initiated enforcement actions was based on the number of times that CMS initiated a group of related actions against a hospital. CMS counts enforcement actions differently, based on the number of notices and penalties issued.[60]

We used hospital characteristic data from the Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level Data hospital dataset to examine CMS enforcement actions by hospital size and urban/rural designation. As part of CMS’s 2024 proposed rule updating hospital price transparency requirements, the agency used this database to estimate the number of hospitals subject to price transparency requirements.[61]

To assess the reliability of the dataset, we reviewed documentation, traced a random selection of hospital locations, and interviewed CMS officials on their use of the dataset. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for analyzing CMS enforcement actions by hospital characteristics.[62]

CMS initiated enforcement actions more frequently against large hospitals—those with 300 or more beds—relative to the overall proportion of such hospitals that are required to comply with price transparency requirements. While large hospitals comprised 14 percent of hospitals subject to transparency requirements, 31 percent of CMS’s enforcement actions were initiated against large hospitals during this timeframe. In contrast, CMS initiated enforcement actions less frequently against small hospitals—those with less than 100 beds—relative to their overall proportion of hospitals. CMS has used public complaints to identify potential hospital noncompliance with price transparency requirements, and CMS officials told us that the public may be more likely to submit complaints against large hospitals. (See table 2.)

|

Hospital size |

Percentage of enforcement actions |

Percentage of hospitals subject to price transparency requirementsa |

|

Less than 100 beds |

42 |

58 |

|

100-299 beds |

26 |

26 |

|

300 or more beds |

31 |

14 |

|

Not available |

1 |

2 |

Source: GAO analysis of Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level Data hospital dataset and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) documentation. I GAO‑25‑106995

Notes: This analysis is based on deficiencies cited in enforcement actions against hospitals that CMS initiated from 2021 through 2023 and closed as of May 2024.

Our count of enforcement actions is based on the number of times that CMS initiated a group of related actions against a hospital. For example, we counted a single initiated enforcement action for a hospital that was issued a warning notice, then issued a corrective action plan request, and then issued a civil monetary penalty. CMS counts enforcement actions differently, based on the number of notices and penalties issued. For example, for a hospital that is issued a warning notice, then issued a corrective action plan request, and then issued a civil monetary penalty, CMS would count three enforcement actions.

aThe Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level Data hospital dataset is a publicly available critical infrastructure dataset overseen by the Department of Homeland Security that includes data on hospitals licensed by the states. According to CMS officials, no single dataset identifies hospitals that are subject to price transparency requirements, but the Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level Data hospital dataset is generally reliable in identifying hospitals that are subject to the requirements. However, the dataset may overestimate the number of hospitals that may be subject to price transparency requirements because institutions licensed by states may have more than one location indicated in the dataset, according to CMS officials. The data also includes certain hospitals that are not required to report their prices under hospital price transparency requirements.

From 2021 through 2023, CMS took enforcement actions against urban and rural hospitals at rates similar to the overall proportion of such hospitals that are subject to price transparency requirements. (See table 3.) We used the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Area Health Resources File to determine whether hospitals were located in a metropolitan area—an area that has at least one urbanized area of 50,000 people. We then categorized hospitals in metropolitan areas as urban and categorized hospitals that were not in metropolitan areas as rural.

|

Urban or rural designation |

Percentage of enforcement actions |

Percentage of hospitals subject to price transparency requirementsa |

|

Urban |

78 |

71 |

|

Rural |

22 |

29 |

Source: GAO analysis of Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level Data hospital dataset, Health Resources and Services Administration’s Area Health Resources File, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) documentation. I GAO‑25‑106995

Notes: This analysis is based on deficiencies cited in enforcement actions against hospitals that CMS initiated from 2021 through 2023 and closed as of May 2024.

Our count of enforcement actions is based on the number of times that CMS initiated a group of related actions against a hospital. For example, we counted a single initiated enforcement action for a hospital that was issued a warning notice, then issued a corrective action plan request, and then issued a civil monetary penalty. CMS counts enforcement actions differently, based on the number of notices and penalties issued. For example, for a hospital that is issued a warning notice, then issued a corrective action plan request, and then issued a civil monetary penalty, CMS would count three enforcement actions.

We used the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Area Health Resources File to determine whether hospitals were located in a metropolitan area—an area that has at least one urbanized area of 50,000 people. We then categorized hospitals in metropolitan areas as urban and categorized hospitals that were not in metropolitan areas as rural.

aThe Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level Data hospital dataset is a publicly available critical infrastructure dataset overseen by the Department of Homeland Security that includes data on hospitals licensed by the states. According to CMS officials, no single dataset identifies hospitals that are subject to price transparency requirements, but the Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level Data hospital dataset is generally reliable in identifying hospitals that are subject to the requirements. However, the dataset may overestimate the number of hospitals that may be subject to price transparency requirements because institutions licensed by states may have more than one location indicated in the dataset, according to CMS officials. The data also includes certain hospitals that are not required to report their prices under hospital price transparency requirements.

GAO Contact

Leslie V. Gordon at (202) 512-7114 or GordonLV@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Will Simerl (Assistant Director), Michael Erhardt (Analyst-in-Charge), Laura Elsberg, Joy Grossman, Eric Peterson, Jennifer Rudisill, Marie Suding, and Roxanna Sun made key contributions to this report.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]According to the Congressional Budget Office, rising prices—rather than the growth in the per person use of health care services—has been the key driver behind increased health care costs in the U.S. See Congressional Budget Office, The Prices That Commercial Health Insurers and Medicare Pay for Hospitals’ and Physicians’ Services (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 2022); and Policy Approaches to Reduce What Commercial Insurers Pay for Hospitals’ and Physicians’ Services (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2022).

The federal government subsidizes premiums for eligible individuals who purchase certain health coverage through the health insurance marketplaces and also forgoes certain federal tax revenues for employee health benefits.

[2]CMS, National Health Expenditure Accounts, accessed July 24, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/data‑research/statistics‑trends‑and‑reports/national‑health‑expenditure‑data/historical.

[3]See Katherine Keisler-Starkey, Lisa Bunch, and Rachel Lindstrom, Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2022, U.S. Census Bureau, (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2023). The U.S. Census Bureau’s health care coverage data is not mutually exclusive and may count more than one source of coverage, such as an individual with Medicare and secondary private plan coverage. KFF (formerly Kaiser Family Foundation) also provided an estimate of health insurance coverage, using Census data and sorting individuals into one category of health coverage. KFF estimated that 55 percent of the population had coverage through private health plans in 2022. See KFF, “Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population,” accessed July 19, 2024, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/.

[4]This study focused on individuals without insurance paying cash for hospital services. See Yang Wang et. al, “The Relationships Among Cash Prices, Negotiated Rates, And Chargemaster Prices For Shoppable Hospital Services,” Health Affairs, (Apr. 2023).

[5]Throughout this report, we refer to private health plans as “health plans.”

[6]Pub. L. No. 111-148, §§ 1001(5), 10101(f), 124 Stat. 119, 137, 887 (2010) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 300gg-18(e) (“Bringing down the cost of health care coverage”)).

Under statute and CMS regulations, hospitals are required to post their “standard charges.” Under hospital price transparency regulations, a “standard charge” is the regular rate established by the hospital that applies to a group of paying patients. See 45 C.F.R. § 180.20 (2023). For purposes of this report, we use the term “price” or “pricing information” in lieu of “standard charge” for the sake of simplicity.

[7]See 42 U.S.C. § 300gg-18(b)(3).

[8]See 84 Fed. Reg. 65,524 (Nov. 27, 2019) (codified as amended at 45 C.F.R. pt. 180). Institutions licensed or approved as hospitals by states, the District of Columbia, or U.S. territories are subject to CMS’s price transparency requirements. In July 2023, CMS estimated that the requirements applied to 7,098 hospitals.

Before issuing regulations, CMS had previously reminded hospitals in 2014 of their need to comply with price transparency statutory requirements. Specifically, CMS issued guidance that encouraged hospitals to either publish their prices or publicize their policies for requesting pricing information.

[9]See 45 C.F.R. § 180.40 (2023).

[10]Meena Seshamani and Douglas Jacobs, “Hospital Price Transparency: Progress and Commitment to Achieving Its Potential,” Health Affairs Forefront (Feb. 14, 2023), accessed Aug. 3, 2023, https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/hospital-price-transparency-progress-and-commitment-achieving-its-potential.

Other studies have assessed hospital price transparency compliance among hospitals. For example, see Turquoise Health, Price Transparency Impact Report, Q1 2023 (San Diego, Calif.: Apr. 18, 2023). As of September 2024, the HHS Office of Inspector General also had ongoing work examining hospital compliance with price transparency requirements.

[11]CMS issued its calendar year 2024 proposed rule in July 2023 and its corresponding calendar year 2024 final rule in November 2023. See 88 Fed. Reg. 49,552 (proposed July 31, 2023); 88 Fed. Reg. 81,540 (Nov. 22, 2023). We refer to the proposed rule as the 2024 proposed rule and the final rule as the 2024 final rule.

[12]We interviewed representatives from the following 16 stakeholder organizations: AHIP (formerly America’s Health Insurance Plans), Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, Brown University Center for Advancing Health Policy through Research, Business Group on Health, Employee Benefit Research Institute, Families USA, FireLight Health, Georgetown Center on Health Insurance Reforms, Handl Health, Health Care Cost Institute, Health Transformation Alliance, KFF (formerly Kaiser Family Foundation), National Alliance of Health Care Purchasers, Patient Rights Advocate, Society of Professional Benefit Administrators, and Turquoise Health. In this report we generally refer to these organizations collectively as “stakeholders.”

[13]CMS requested its Alliance to Modernize Healthcare Federally Funded Research and Development Center, operated by MITRE, generate suggestions to improve and identify best practices for displaying hospital pricing data. To do so, the Alliance to Modernize Healthcare Federally Funded Research and Development Center convened industry experts from hospitals, industry, and academia for an independent technical expert panel The panel published its findings and recommendations in a 2022 report. See MITRE, Hospital Price Transparency Machine-Readable File Technical Expert Panel Report and MITRE Recommendations to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, (McLean, Va: Nov. 2022).

[14]Our interviews included 16 stakeholder organizations that represent users of hospital pricing data or have relevant subject matter expertise on the use of hospital pricing data. For the purposes of summarizing stakeholder statements in this report, “many” represents at least nine stakeholders, and “some” represents three to eight stakeholders.