NAVAL REACTORS

Independent Analyses of Cost, Schedule, and Quality of Work Needed for Spent Fuel Handling Facility Project

A Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106997. For more information, contact Nathan Anderson at (202) 512-3841 or andersonn@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106997, a report to congressional committees

Independent Analyses of Cost, Schedule, and Quality of Work Needed for Spent Fuel Handling Facility Project

Why GAO Did This Study

Naval Reactors, jointly managed by the U.S. Navy and DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration, is constructing a new facility to replace and upgrade the handling and processing of naval spent fuel. Naval Reactors has experienced challenges completing the project, causing schedule delays and cost increases of more than $2 billion.

Senate Report 118-58 accompanying S. 2226, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, includes a provision for GAO to review the status of naval spent fuel and related facilities. This GAO report (1) describes Naval Reactors’ plans for managing spent fuel, (2) assesses the extent to which SFHP cost and schedule estimates exhibit key characteristics of reliable estimates, and (3) examines the extent to which Naval Reactors has analyzed the causes of SFHP cost and schedule increases, and quality assurance problems. GAO reviewed agency documents on spent fuel management and the SFHP; compared SFHP estimates with cost- and schedule-estimating best practices; and interviewed Naval Reactors and DOE officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations, including that Naval Reactors conduct an independent root cause analysis of SFHP cost increases and schedule delays. In their written comments, the National Nuclear Security Administration agreed with GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Office of Naval Reactors (Naval Reactors) plans to modernize its facilities for managing naval spent fuel at the Naval Reactors Facility at the Idaho National Laboratory. Naval Reactors plans to continue storing the spent fuel there until the Department of Energy (DOE) develops a repository for permanent disposal. However, as of August 2024, DOE has no formal plans for the development of an interim storage facility or a permanent repository for nuclear waste.

GAO reviewed the third baseline revision (the most recently completed) for the Naval Spent Fuel Handling Recapitalization Project (SFHP). GAO found that Naval Reactors’ cost and schedule estimates did not fully reflect the key characteristics of credible and comprehensive estimates. For example, Naval Reactors requires its major construction projects to follow Naval Reactors and DOE’s project management order. DOE requires cost estimates to use the best practices identified in GAO’s Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide. Naval Reactors did not conduct an independent cost estimate—a best practice. To validate the estimate, its contractor relied on several cross-checks on major cost elements completed by subcontractors external to the project. By following all best practices for credible and comprehensive cost estimates when developing its planned fourth baseline revision, Naval Reactors would have greater assurance that the estimated costs are realistic.

Naval Reactors has not conducted independent analyses of the underlying causes of SFHP cost increases and quality assurance problems that have led to the rebaselining. DOE’s project management order requires independent root cause analyses of project cost overruns, and of the quality of the work performed. However, while analyses were conducted by the contractor, they were not conducted by staff independent from project management and were thus not independent. Independent analyses of root causes could provide Naval Reactors with more objective and reliable information to oversee the project contractor and help prevent further project cost increases and delays.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

FMP |

Fluor Marine Propulsion LLC |

|

Naval Reactors |

Office of Naval Reactors |

|

NQA-1 |

Nuclear Quality Assurance-1 |

|

NRF |

Naval Reactors Facility |

|

SFHP |

Naval Spent Fuel Handling Recapitalization Project |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 12, 2024

Congressional Committees

U.S. Navy warships are deployed around the world to provide a credible forward presence, ready to respond on the scene wherever America’s interests are threatened. Nuclear propulsion plays an essential role in this, providing the mobility, flexibility, and endurance that today’s Navy requires to meet a growing number of missions. In doing so, nuclear powered warships generate spent fuel. If not properly managed, spent fuel can pose environmental, public health, and security risks.

The U.S. Navy and the Department of Energy’s (DOE) National Nuclear Security Administration jointly manage the Office of Naval Reactors (Naval Reactors), which implements the Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program.[1] Naval Reactors has cradle-to-grave responsibility for all naval nuclear propulsion matters, from designing naval nuclear propulsion systems to managing and properly disposing of the spent fuel generated by nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers.

To prepare spent fuel for disposal, Naval Reactors examines, processes, and stores the fuel at the Naval Reactors Facility (NRF) at the Idaho National Laboratory. In addition to naval spent fuel, DOE is responsible for disposing of highly radioactive waste from the nation’s nuclear weapons program and spent fuel from other noncommercial origins. DOE and the Navy are party to a 1995 settlement agreement with the State of Idaho that governs the acceptance, management, and removal of spent fuel and other forms of nuclear waste from Idaho (the Idaho Settlement Agreement). The Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 directed DOE to investigate sites for a federal geologic repository to permanently dispose of spent fuel and high-level nuclear waste.

The NRF plays a vital role in the Navy’s ability to properly maintain fleet readiness. However, parts of the NRF that Naval Reactors uses to process, examine, and manage spent fuel built in the 1950s are deteriorating or obsolete. Naval Reactors is currently executing the Naval Spent Fuel Handling Recapitalization Project (SFHP) at the Idaho National Laboratory to replace and enhance spent fuel management functions currently carried out at the NRF Expended Core Facility.

In September 2018, Naval Reactors began construction of the SFHP with an approved cost baseline of $1.7 billion and an estimated start of operations in Fiscal Year 2024. Since then, Naval Reactors has experienced challenges in executing the project, including rising costs for construction services and some construction work not meeting Naval Reactors nuclear facility quality assurance requirements. As a result, Naval Reactors has revised the cost and schedule baseline estimates for the facility several times (see table 1). In October 2022, Naval Reactors completed a third performance baseline revision that estimated the project would cost $3 billion and complete construction in Fiscal Year 2028. As of August 2024, Naval Reactors was developing new estimates for a fourth revision to the project’s performance baseline.

Table 1: Spent Fuel Handling Recapitalization Project (SFHP) Initial Cost and Schedule Baseline and Revisions

|

Performance baseline |

Date approved |

Estimated project cost |

Estimated project completion date |

|

Initial |

September 2018 |

$1.69 billion |

Third Quarter of Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 |

|

Revision 1 |

October 2019 |

$2.06 billion |

Third Quarter of FY 2026 |

|

Revision 2 |

July 2021 |

$2.33 billion |

Third Quarter of FY 2026 |

|

Revision 3 |

October 2022 |

$3 billion |

Fourth Quarter of FY 2028 |

|

Revision 4 |

Ongoing |

Ongoing |

Ongoing |

Source: GAO analysis of Naval Reactors documents and interviews with Naval Reactors officials. | GAO‑25‑106997

The report accompanying a Senate bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review issues related to managing and storing naval spent fuel.[2] Our review (1) describes Naval Reactors’ plans for managing its spent fuel, (2) assesses the extent to which cost and schedule estimates for the SFHP exhibit key characteristics of reliable estimates, and (3) examines the extent to which Naval Reactors has analyzed the underlying causes of the SFHP cost and schedule increases, and quality assurance problems.

To address these three objectives, we examined key documents and interviewed officials with Naval Reactors, DOE’s Offices of Environmental Management and Nuclear Energy, state officials with the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality that monitor compliance with the Idaho Settlement Agreement, and contractors responsible for handling naval spent fuel and managing and constructing spent fuel facilities.

To describe Naval Reactors’ plans for managing its spent fuel, we reviewed Naval Reactors’ NRF infrastructure plans and DOE offices’ planning documents regarding disposal of Naval Reactors’ spent fuel.

To determine the extent to which cost and schedule estimates for the SFHP exhibit key characteristics of reliable estimates, we assessed the cost and schedule estimates that Naval Reactors approved in October 2022 for the project’s third performance baseline revision. We selected the third performance baseline revision because it was the most-recently completed baseline revision at the time of our review (Naval Reactors was developing new estimates for a fourth revision during our audit work). We assessed the estimates against selected GAO best practices for cost and schedule estimating.[3] Specifically, we examined the comprehensive and credible characteristics of the estimates.

To examine the extent to which Naval Reactors has analyzed the underlying causes of the SFHP cost increases and quality assurance problems, we reviewed Naval Reactors and SFHP contractor documents and interviewed Naval Reactors officials to identify actions taken by Naval Reactors and contractors. We also reviewed SFHP quality assurance audit reports completed between April 2018 and February 2024.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 through December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

U.S. Nuclear Fleet

The U.S. Navy has operated nuclear-powered submarines since 1955 (when the USS Nautilus started operations) and has operated nuclear-powered aircraft carriers since 1961 (when the USS Enterprise started operations).[4] Currently, the U.S. Navy operates 78 nuclear powered vessels, which represents over 40 percent of the U.S. Navy’s major warships. According to U.S. Navy documents, 11 of these are aircraft carriers, 49 are fast-attack submarines, 14 are nuclear ballistic missile submarines, and four are former ballistic missile submarines converted to carry conventional cruise missiles.

The U.S Navy is in the process of transitioning to new ship classes in all three categories. For example, the Navy is in the process of replacing the Los Angeles-class attack submarines— which first entered service in the 1970s—with Virginia-class submarines. The Virginia-class has many advanced and upgraded capabilities, including a reactor plant designed to last the entire 33-year planned life of the ship without refueling.

Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program

Naval Reactors’ Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program has several key responsibilities that support its mission, according to U.S. Navy and Naval Reactors documents. These responsibilities include: (1) managing the Naval Nuclear Laboratory complex that conducts research and development to support designing and testing reactors; (2) overseeing the contractors responsible for designing, procuring, and building propulsion plant equipment; (3) supporting the shipyards that build, overhaul, and service the propulsion plants of nuclear-powered vessels; (4) supporting the Navy facilities and support ships that allow nuclear-powered vessels to remain deployed in the field; and (5) managing the nuclear power schools and Naval Reactors training facilities that train sailors in how to operate reactors in the field.[5]

Idaho Settlement Agreement

The 1995 Idaho Settlement Agreement and its 2008 addendum commit the Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program to ship naval spent fuel out of Idaho for disposal and contain provisions for managing naval spent fuel and accepting new shipments.[6] Specifically, the agreements include the following provisions.

· DOE and the Navy are to move naval spent fuel from storage in pools of water to dry storage, and later to move most of the naval spent fuel out of Idaho.

· Naval spent fuel that arrived at the Idaho National Laboratory before 2026 must generally leave the state by 2035.

· The Navy can maintain a limited amount of naval spent fuel at the Idaho National Laboratory after 2035, subject to certain limitations.[7]

· The Navy may ship a running average of no more than 20 shipments per year of naval spent fuel to the Idaho National Laboratory.

· The state of Idaho can administer a penalty of $60,000 per day to the Navy if it fails to move naval spent fuel from wet storage to dry storage within the time constraints specified in the 2008 addendum.[8]

Spent Fuel Management Process

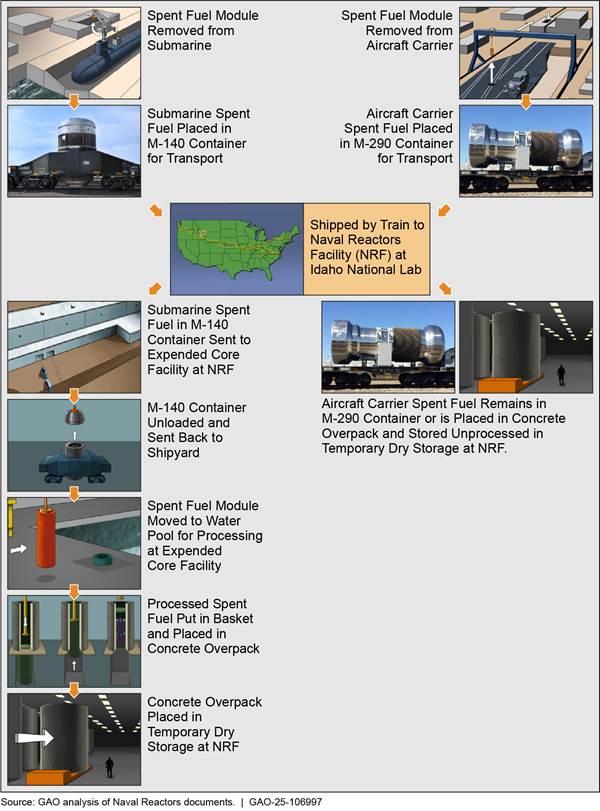

The process for managing naval spent fuel starts with removal of the fuel, which occurs when warships are refueled or defueled. In either case, spent fuel is removed from vessels at one of four public and private Navy shipyards and shipped by rail to the NRF at the Idaho National Laboratory.[9] For the journey, spent fuel is transported in one of two types of specially designed, rugged rail shipping containers: the M-140 container for submarine fuel or the larger M-290 containers for aircraft carrier fuel (see Fig. 1).

Once shipping containers arrive at NRF, the spent fuel modules are removed from the containers and processed and examined in a water pool at the NRF’s Expended Core Facility. Once the spent fuel is processed and examined in the Expended Core Facility, the spent fuel is then placed into stainless steel canisters, that are then placed into large concrete overpacks to provide radiation shielding.[10] Overpacks are then moved into temporary dry storage at the NRF Overpack Construction and Storage Facility.

Prior to 2016, Naval Reactors would disassemble the longer fuel modules used in aircraft carriers inside a water-filled barge that was placed next to the ship from which the fuel was extracted, according to a 2018 Institute for Defense Analysis report. These disassembled modules could be placed in the same M-140 shipping containers used for the submarine spent fuel. This process was terminated due to the age of the water-filled barge and the increased efficiency of the M-290 container system in servicing multiple aircraft carrier types.

Since 2016, Naval Reactors has managed the longer aircraft carrier spent fuel modules by loading them fully assembled into the longer M-290 shipping containers for transport to the NRF. The Expended Core Facility, however, does not contain the required features to unload M-290 shipping containers. As a result, Naval Reactors has implemented a contingency plan to manage aircraft carrier spent fuel at the NRF. With this plan, Naval Reactors currently stores the unprocessed aircraft carrier spent fuel in temporary dry storage at the NRF until a facility exists in which the aircraft carrier spent fuel can be unloaded. See figure 2 for a description of the spent fuel handling process.

Naval Reactors’ Contractor Oversight Structure and Project Management Requirements

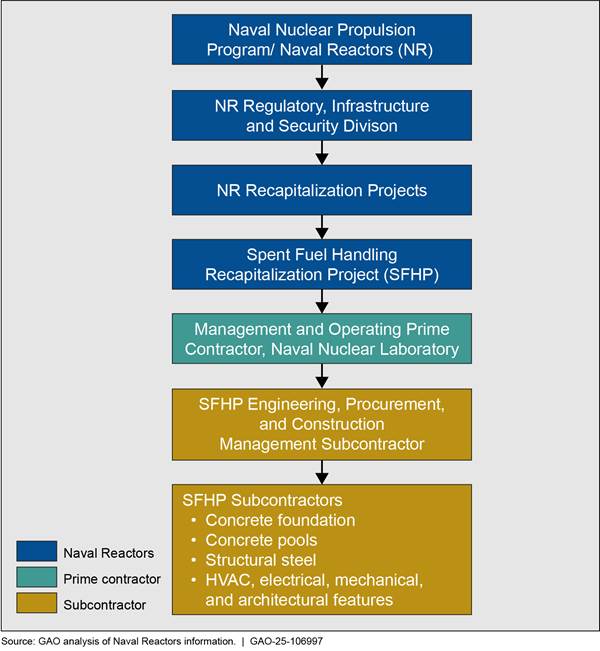

Naval Reactors is responsible for overseeing the contractors and subcontractors that manage and operate major capital asset construction projects at the Naval Nuclear Laboratory complex, including the SFHP, according to Naval Reactors reports.[11] Specifically,

· Naval Reactors’ Recapitalization Projects Program within its Regulatory, Infrastructure and Security Division is responsible for overseeing the contractor who designed and is constructing the SFHP. A Naval Reactors federal project manager oversees the project. The SFHP is one of several projects managed by this program, which also includes the Naval Examination Acquisition Project.

· Fluor Marine Propulsion LLC (FMP) has been responsible for the SFHP since 2018, when it took over as the management and operating contractor for Naval Reactors’ Naval Nuclear Laboratory complex, which includes the NRF in Idaho.[12]

· FMP has awarded subcontracts for completing construction of different parts of the SFHP. In particular, FMP awarded Jacobs the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction Management (construction management) subcontract and is responsible for construction of the SFHP.

See figure 3 outlining Naval Reactors’ SFHP contractor management structure.

Figure 3: Naval Reactors Spent Fuel Handling Recapitalization Project (SFHP) Contractor Management Structure

As a joint program of DOE and the Navy, Naval Reactors is not directly subject to the requirements contained in DOE Order 413.3B on project management and DOE Order 414.1D on quality assurance.[13] Instead, Naval Reactors has been granted “equivalencies” under these orders. Equivalencies “represent acceptable, alternative approaches to achieving the goal of a directive’s requirement.”[14] Naval Reactors documents its alternative approach in implementation bulletins.[15] Further, per the Naval Reactors implementation bulletin for DOE Order 413.3B, Program and Project Management for the Acquisition of Capital Assets, projects estimated to cost more than $750 million, such as the SFHP, must develop project-specific implementation plans for project management requirements that are consistent with the implementation bulletin and DOE Order 413.3B.

The stated goal of Order 413.3B is to deliver fully capable projects that meet safeguards and security, environmental, safety, and health requirements within the original performance baseline cost and schedule. The order requires projects develop and manage cost and schedule estimates to move past critical decisions, such as approval of a project’s performance baseline.[16] Under the order, cost estimates should be developed, maintained, and documented in a manner consistent with methods and the best practices identified in GAO’s Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide. Furthermore, a project’s Integrated Master Schedule should be developed, maintained, and documented in a manner consistent with methods and the best practices identified in GAO’s Schedule Assessment Guide.[17] Under the order, when it is determined that a project’s performance baseline scope, schedule, or cost will be breached, the relevant program office is to conduct an independent and objective root cause analysis to determine the underlying causes of the cost overruns, schedule delays, or performance shortcomings.[18] The Naval Reactors implementation bulletin for DOE Order 413.3B and the SFHP management implementation plan do not address these requirements.

The stated goal of DOE Order 414.1D is to ensure that products and services meet or exceed requirements and expectations regarding project quality assurance. The order requires that contracted projects plan and conduct independent assessments to measure item and service quality, measure the adequacy of work performance, and to promote improvement. In addition, the order requires all projects to follow appropriate standards for nuclear quality assurance, such as American Society of Mechanical Engineers Nuclear Quality Assurance-1 (NQA-1) requirements for Nuclear Facility Applications. NQA-1 requires that conditions adverse to quality to be identified promptly and corrected as soon as practicable. The Naval Reactors implementation bulletin for Order 414.1D provides guidance for major projects on the development of a quality assurance program and quality assurance oversight to implement the goals of the order. It also identifies additional Navy criteria for the development of quality assurance programs. The implementation bulletin and the additional criteria do not address the need for independent assessments of quality.

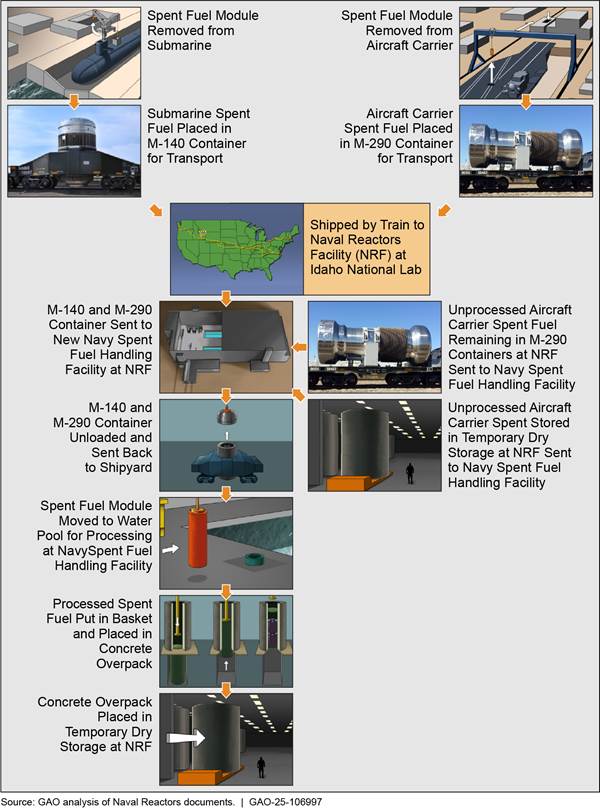

Naval Reactors Plans to Manage and Store Spent Fuel at the Idaho National Laboratory Facility Until DOE Develops a Permanent Geological Repository

Naval Reactors plans to modernize its facilities for managing naval nuclear fuel at the NRF in Idaho and plans to continue storing the fuel at NRF until DOE develops a repository for permanent disposal, according to Naval Reactors reports and officials. Specifically, Naval Reactors designed the SFHP to replace and improve the spent fuel processing and cooling functions of the Expended Core Facility by providing facilities equipped to process and package full-length aircraft carrier fuel, as well as improved space for processing and workflow, according to Naval Reactors officials we interviewed.

In addition to the SFHP, Naval Reactors has begun planning for a second facility—the Naval Examination Acquisition Project—to replace and enhance the NRF’s current facility used for detailed examinations of naval spent fuel and other propulsion plant components to ensure they are performing as designed. As of August 2024, Naval Reactors has completed an analysis that compares the risks, benefits, and costs of alternatives to complete the project, according to Naval Reactors officials. Naval Reactors expects to complete a conceptual design for the project in early 2025.

Current operations at the Expended Core Facility. A 2018 Institute for Defense Analysis report stated that the facility is over 65 years old, maintenance has become a greater issue, and because it can no longer fully support the Navy’s spent fuel management processing needs, significant bottlenecks in aircraft carrier spent fuel processing are occurring.[19] Furthermore, according to Naval Reactors officials, although the existing Expended Core Facility continues to be maintained and operated in a safe and environmentally responsible manner, it does not meet current standards (i.e., standards that were not applicable at the time of construction), and requires replacement.

Planned operations with the SFHP. According to Naval Reactors 2008 Mission Need Statement, the SFHP will recapitalize the NRF spent fuel management infrastructure with a facility that meets modern codes and standards for a nuclear facility. The facility is also designed to process spent fuel at a rate that supports the Navy’s reactor servicing schedules and complies with the Idaho Settlement Agreement. Figure 4 shows progress on the construction of the SFHP as of May 2024.

Figure 4: View of the Spent Fuel Handling Recapitalization Project (SFHP) Construction as of May 2024

When operational, the Spent Fuel Handling Facility will be used to process spent fuel from both Navy aircraft carriers and submarines, but will initially process only aircraft carrier spent fuel, according to Naval Reactors Project Execution Plan and Naval Reactors officials. Naval Reactors officials told us that until the Spent Fuel Handling Facility is operational, Naval Reactors plans to continue processing and cooling submarine spent fuel at the Expended Core Facility, and then place this fuel in dry storage at the NRF Overpack Construction and Storage Facility. According to Naval Reactors officials, because of delays completing the SFHP, the quantity of unprocessed aircraft carrier spent fuel stored at the NRF is growing. They estimate it will take until the early 2040s to complete processing this spent fuel. Figure 5 shows the plans for naval spent fuel management and processing once the Spent Fuel Handling Facility is operational.

Naval Reactors plans for spent fuel disposal. Naval Reactors officials told us they currently manage 41 metric tons of spent fuel at the NRF. Most of this spent fuel is processed and packaged in 207 concrete overpacks loaded at the NRF Overpack Construction and Storage Facility awaiting shipment to a national repository for permanent disposal. According to Naval Reactors officials, the NRF Overpack Construction and Storage Facility has expanded three times to accommodate spent fuel overpacks. Furthermore, according to the officials, Naval Reactors is planning a further expansion of the facility between 2034 and 2036 at an estimated cost of $33 million to accommodate the storage of additional spent fuel overpacks. As discussed above, under the Idaho Settlement Agreement, the Navy and DOE have committed to shipping spent fuel out of the state.

Naval Reactors plans to move existing spent fuel stored at the NRF to a permanent geological repository in the future when such a repository is operational. However, as we have reported in prior work, DOE does not currently have plans for a permanent geological repository to dispose of the nation’s nuclear waste, including naval spent fuel.[20] For decades, DOE had planned to permanently dispose of DOE nuclear waste, including naval spent fuel, in a deep geological repository at Yucca Mountain in southwestern Nevada. However, in 2010, DOE announced that it no longer considered Yucca Mountain a workable option for disposal of the nation’s nuclear waste and terminated its efforts to license a repository there.[21]

DOE has directed the Office of Nuclear Energy to work with DOE elements to develop a conceptual framework for nuclear waste disposal, including Naval Reactors spent fuel, according to Office of Nuclear Energy officials. However, as of August 2024, the Office of Nuclear Energy has no formal plans or timelines for the development of an interim storage facility or a permanent disposal repository for nuclear waste. Naval Reactors officials told us that Naval Reactors continues to support DOE efforts to develop the plan and timeline for permanent disposal for nuclear waste.

Cost and Schedule Estimates for the SFHP Did Not Fully Reflect Key Characteristics of Reliable Estimates

Naval Reactors’ cost and schedule estimates for the SFHP’s third performance baseline did not fully reflect key characteristics of reliable estimates because Naval Reactors did not fully follow best practices in developing the estimates.[22] As discussed above, Naval Reactors requires that its major projects (i.e., those estimated to cost more than $750 million) adhere to project implementation plans that are consistent with DOE Order 413.3B.[23] According to the DOE order, a project should develop and maintain cost estimates and schedule estimates in a manner consistent with the best practices identified in GAO’s cost and schedule guides.[24] These best practices, if implemented, would result in estimates exhibiting the characteristics of reliable estimates.

We found that Naval Reactors did not fully follow best practices associated with comprehensive and credible cost estimates. With regard to schedule estimates, we found that Naval Reactors substantially followed best practices associated with a comprehensive schedule, but partially followed best practices associated with a credible schedule. See table 2 and below for a summary of our observations. We provide details of our analyses in Appendix II.

Table 2: Assessment of Naval Reactors’ Spent Fuel Handling Recapitalization Project (SFHP) Cost and Schedule Estimates for The Third Performance Baseline Revision Against Selected Characteristics of Reliable Estimates

|

Estimate |

Characteristic |

Overall Assessment |

|

Cost estimate |

Comprehensive |

Partially met |

|

Credible |

Partially met |

|

|

Schedule |

Comprehensive |

Substantially met |

|

Credible |

Partially met |

Source: GAO analysis of Naval Reactors cost and schedule data. | GAO‑25‑106997

Note: We determined the overall rating assessment for a characteristic by rating each individual best practice comprising that characteristic and assigning it a number: Not Met = 1, Minimally Met = 2, Partially Met =3, Substantially Met = 4, and Met = 5. Then, we took the average of the individual assessment ratings to determine the overall rating for each of the four characteristics. The resulting average becomes the Overall Assessment as follows: Not Met = 1.0 to 1.4, Minimally Met = 1.5 to 2.4, Partially Met = 2.5 to 3.4, Substantially Met = 3.5 to 4.4, and Met = 4.5 to 5.0. For the individual assessments, see Appendix II.

Cost Estimate Assessment

According to our analysis, Naval Reactors’ cost estimate for the third baseline revision partially met the characteristic of a comprehensive estimate. We found the following:

· The cost estimate for the third baseline revision was based on a product-oriented work breakdown structure with a detailed dictionary describing each element. However, the documentation of the cost estimate for the third baseline revision did not report cost using the work breakdown structure. Naval Reactors officials said that costs were reported using the work breakdown structure in the annual SFHP planning estimate, which is a separate document that was not part of the performance baseline revision process.

· The cost estimate for the third baseline revision did not include all potential costs over the project’s full life cycle, from inception through development, production, operations and maintenance, and disposal of the project. For example, while Naval Reactors provided a high-level discussion of its approach to operations and maintenance, it did not include these costs or government costs in the estimate. Naval Reactors officials said that the project manages life cycle costs in other ways, such as including them in the annual operations budgets for the NRF. According to the GAO Cost Guide, without fully accounting for life cycle costs, management will have difficulty successfully planning program resource requirements and making better informed decisions.[25]

· Naval Reactors had documentation for the cost-influencing ground rules and assumptions for the SFHP. However, the information was spread across multiple documents and models. This made it difficult to fully assess how specific ground rules or assumptions had an impact on cost estimate. Unless assumptions are documented in a consolidated manner with their sources and supporting historical data, decision-makers will not understand the level of certainty around the assumption or the cost estimate.

According to our analysis, Naval Reactors’ cost estimate for the third baseline revision partially met the characteristic of a credible estimate. We made the following observations:

· Naval Reactors’ cost estimate for the third baseline revision employed several cross-checks on major cost elements to validate them but did not conduct an independent cost estimate. In 2018, teams not directly associated with the project conducted a detailed evaluation of the SFHP cost estimates. While these evaluations were robust enough to serve as cross-checks, they were not conducted by an entity independent of the acquisition chain of command for the project. As a result, none of these evaluations can be considered formal independent cost estimates. Naval Reactors obtained an independent cost assessment from the Office of the Secretary of Defense’s Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation in 2018, this analysis was not updated for the third baseline revision or prior revisions. While no formal independent cost estimates or assessments have been conducted on the project since 2018, the project contractor has had cross-checks on major cost elements completed by subcontractors external to the project to support cost estimate validation. Having an independent cost estimate could provide Naval Reactors with additional insight into the program’s potential costs because an independent cost estimator would likely use different methods and have less organizational bias than an estimator associated with the program.

· Naval Reactors’ cost estimate for the third baseline revision did not include a project-wide sensitivity analysis, used to identify key elements that drive cost. Including a sensitivity analysis in developing cost estimates may allow Naval Reactors and stakeholders to better understand the factors that most affect the cost estimate.

· The risk and uncertainty analysis associated with Naval Reactors’ cost estimate for the third baseline revision used to determine the level of confidence in the estimate—was generally detailed. However, we found the risk and uncertainty assessment indicated that the project had estimated a low level of cost risk. A frequent cause of low estimated cost risk is reliance on subject matter experts rather than historical data to assess risks, as occurred in this estimate. According to the GAO Cost Guide, while using data collected from subject matter experts is a valid estimating approach in the absence of better data, it also has the potential to be biased and should be used sparingly.

Naval Reactors officials told us that to improve cost estimating as they complete their fourth performance baseline revision, they have directed contractors developing cost estimates to adhere to DOE’s cost estimating guidance. By fully following all best practices for developing comprehensive and credible cost estimates on the SFHP, including development of an independent cost estimate, Naval Reactors would provide greater assurance that the estimated costs for the fourth performance baseline revision—as well as any future performance baseline revisions—are reliable.

Schedule Assessment

Naval Reactors manages three tiers of schedules that are updated monthly: (1) low-level, detailed construction schedules managed by subcontractors; (2) a master schedule that summarizes subcontractors’ efforts and integrates engineering and other construction follow-on effort; and (3) a high-level integrated master schedule that integrates the master schedule with government activities and other work scope such as facility start-up and transition of operations. Our schedule analysis mainly examined the second-tier schedule managed by Jacobs—the construction subcontractor—though we also examined the other schedule tiers as necessary.

According to our analysis, Naval Reactors’ schedule substantially met the characteristic of a comprehensive schedule. We found the following:

· Naval Reactors’ schedule estimate for the third baseline revision assigned resources to all activities. While limited resources were included in the second-tier schedule managed by Jacobs, resources were loaded on lower-level subcontractor schedules, as well as the top-level integrated master schedule. Program documentation provided guidance on estimating resources for discrete activities and resources were reviewed at each level of the three-tier schedule. However, we were not able to reconcile the total cost represented in the master schedule with the program’s estimated cost at completion.

· Naval Reactors’ second-tier schedule managed by Jacobs for the third baseline revision had activity durations that are reasonably short and consistent with the needs of effective planning. However, we found that level of effort activities—those related to the passage of time and that have no physical products or defined deliverables—were not well marked in the schedule. Jacobs should clearly mark levels of effort activities in the schedule because they can interfere with the validity of the critical path if they are not. According to Naval Reactors, Jacobs excluded their own activities from the critical path analysis, whether labeled as level-of-effort or not.

We found that Naval Reactors’ schedule estimate for the third baseline revision partially met the characteristics of a credible estimate. We found the following:

· Key dates were somewhat consistent across the three tiers of schedules. However, we found several dates were not consistent. For example, the three schedule tiers had different finish dates for structural steel fabrication and erection. The high-level integrated master schedule indicated that the structural steel fabrication and erection would be finished in February 2025. In contrast, the corresponding date in the mid-level master schedule was 6 months earlier in August 2024. Without traceability of dates through different levels of the schedule, there is little assurance that the representation of the schedule to different audiences is consistent and accurate. Naval Reactors officials told us that this will be corrected as part of the fourth baseline revision.

· Naval Reactors did not perform a schedule risk analysis for the third project performance baseline revision. Naval Reactors officials stated that they did not conduct this analysis because, at the time, the project mission delivery date was based on the needs of the fleet. As a result, officials managing the project were unclear how much room there would be for delay. However, Naval Reactors officials said they plan to conduct a schedule risk analysis for the fourth project performance baseline revision. A schedule risk analysis allows managers to determine the likelihood of the project meeting its completion date, and what risks are most likely to delay the program.

Naval Reactors officials told us they are making several changes related to cost and schedule estimating as they complete their fourth performance baseline revision. For example, to improve schedule reliability, Naval Reactors plans to implement a formal schedule risk analysis process for the development of the fourth project performance baseline revision of the SFHP. By fully following all best practices associated with developing credible schedules for the SFHP, Naval Reactors would provide greater assurances that the schedules for the fourth performance baseline revision—as well as any future performance baseline revisions—are reliable.

Naval Reactors Has Not Independently Analyzed the Root Causes of Cost Increases and Quality Assurance Problems on the SFHP

Naval Reactors revised the performance baseline of the SFHP four times in the last 6 years but has not conducted an independent analysis of the underlying causes of cost increases. Furthermore, Naval Reactors has not conducted an independent review of quality assurance problems on the project, including significant problems with the quality of work performed by contractors. Without identifying and correcting these root causes, it will be difficult for Naval Reactors to address current problems with the SFHP, which may lead to further cost increases, schedule delays, and quality assurance problems on the SFHP and future Naval Reactors construction projects.

Naval Reactors Has Not Independently Analyzed Root Causes of the Cost Increases and Schedule Delays on the SFHP

Naval Reactors has not independently analyzed the root causes of SFHP cost increases and schedule delays despite revising the performance baseline multiple times in the last 6 years. We found that Naval Reactors has instead relied on assessments by FMP—the prime contractor—to identify causes of cost increases and schedule delays. According to Naval Reactors officials, FMP used elements of its own organization that were outside of the project to support independent project reviews, such as performance baseline revisions assessments. However, these assessments are all signed by project management staff. Furthermore, as the project’s prime contractor, FMP is responsible for managing the project. FMP, therefore, is not in a position to independently and objectively identify root causes and potential corrective actions. Instead, that type of independent analysis could be conducted, for example, by an external independent contractor, or an independent office within Naval Reactors or DOE. Moreover, FMP’s assessments and contractor actions to address the causes of cost increases and schedule delays have not prevented significant further project cost increases and delays.

In the reports requesting approval for each project performance baseline revision, FMP identified the causes for schedule delays and cost increases. For each performance baseline revision, the causes include the following:

· Revision 1. In August 2019, FMP identified procurement challenges associated with 2019 record low unemployment combined with high demand for construction services as the primary causes for schedule delays and cost increases.[26] According to the report, these factors affected FMP’s ability to attract subcontractors for the project’s (1) concrete foundation and (2) structural steel and erection scopes of work.

· Revision 2. In May 2021, FMP and Naval Reactors identified challenges associated with the project, including (1) inefficiencies in the construction labor and supplies markets due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and (2) unexpected geologic conditions discovered during excavation that led to cost increases and schedule delays.[27]

· Revision 3. In September 2022, FMP identified additional causes for schedule delays and cost increases to the project. These included (1) poor concrete subcontractor performance, including work not meeting quality assurance requirements resulting in construction work stoppage, (2) delays due to terminating work scope from the poorly performing subcontractor’s contract and procuring a new subcontractor to complete this work scope, and (3) problems with construction sequencing that resulted from work not meeting quality assurance requirements.[28]

· Revision 4i. In July 2023, FMP identified two primary causes contributing to the need to develop a fourth project baseline revision. These included (1) construction delays due to the construction subcontractor not fully understanding the quality requirements for the facility’s foundation, resulting in concrete not meeting performance requirements and foundation defects requiring repair; and (2) project delays due to procurement challenges with the project’s last major construction subcontract that resulted in the inability to place this contract on the planned schedule.[29]

DOE’s Order 413.3B on project management requires an independent and objective root cause analysis of cost overruns, schedule delays, and performance shortcomings when a project’s performance baseline will be breached.[30] Further, as previously discussed, Naval Reactors requires its major projects (i.e., those estimated to cost more than $750 million) to have project implementation plans consistent with the Naval Reactors’ implementation bulletin on project management and DOE Order 413.3B.

Naval Reactors has not completed an independent root cause analysis because its current practice is to rely on project management staff with FMP to formally self-assess problems and identify corrective actions, while Naval Reactors performs its own internal oversight of the contractor. Such reviews could be completed by, for example (1) Naval Reactors or DOE offices not directly involved in the management of the project, as is the practice for DOE capital asset projects; (2) a project management contractor or owner’s agent not involved in the project; or (3) DOE’s Office of Project Management. Such independent reviews could provide Naval Reactors with independent and objective analysis determining the root causes of the SFHP cost increases and delays.

We also found that the SFHP implementation plan did not include a provision similar to the Order 413.3B requirement for an independent root cause analysis of baseline breaches. Updating Naval Reactors implementation bulletin for DOE Order 414.1D and the SFHP implementation plan to require independent root cause analysis of baseline breaches and ensuring the completion of independent and objective analysis of the root causes of persistent SFHP cost increases and schedule delays could provide Naval Reactors with more objective and reliable information to manage the project contractor and address the causes of cost increases and delays. Insights from such an analysis may also help Naval Reactors avoid similar cost and schedule challenges from recurring on future large construction projects as Naval Reactors continues to modernize facilities at Idaho National Laboratory.

Naval Reactors Has Not Conducted an Independent Analysis of Quality Assurance Problems on the SFHP

Naval Reactors has not conducted an independent analysis of quality assurance problems on the SFHP. The SFHP contractors have experienced persistent challenges managing quality on the project since April 2020, according to our review of project contractor audit reports. Most notably, the SFHP has experienced significant problems with the quality of work that resulted in an approximately 4-month work stoppage starting in February 2022, and project rework, according to contractor reports we examined and Naval Reactors officials we interviewed.

Specifically, according to contractor reports, the work done by the concrete foundation contractor did not meet Naval Reactors construction quality requirements. A February 2022 project audit report concluded that the project’s concrete foundation contractor failed to effectively implement their quality assurance program when performing activities affecting quality.[31] Later, in September 2022, FMP reported that the concrete contractor’s poor performance, including work not meeting quality assurance requirements, resulted in construction work stoppage and the need to revise the project performance baseline for the third time.[32] According to Naval Reactors officials, when the construction contractor quality assurance program discovered work that did not meet quality assurance requirements, the project followed requirements to correct and restore the foundation cracking to a condition that is compliant with all quality requirements. Figure 6 shows SFHP concrete foundation cracking.

We reviewed all SFHP quality assurance program audit reports completed from April 2018 through February 2024 and found that FMP has repeatedly identified corrective actions not addressed in a timely manner by subcontractors. For example:

· In April 2020, FMP reported that the construction subcontractor did not act in an urgent or timely fashion to implement corrective actions to address quality assurance deficiencies.

· In September 2023, more than 3 years later, FMP again reported that construction subcontractor quality assurance processes were ineffective and lacked the urgency and commitment to correct problems promptly. For example, FMP reported the time it took subcontractors to complete corrective actions exceeded time frames established in corrective actions plans. In many cases time frames for corrective actions were exceeded by 1 year and, in some cases 2 years. In addition, FMP reported that some quality assurance problems recurred, which indicates an ineffective evaluation and understanding of the problem.

As discussed above, DOE’s Order 414.1D on quality assurance requires projects to (1) conduct independent assessments of contractor projects to measure service quality and adequacy of work performance and to promote improvement, and (2) requires projects to adhere to standards that in turn require projects to correct quality problems, identify their causes, and plan to prevent their recurrence. Naval Reactors is not bound by DOE’s order but requires its projects to develop a quality assurance program and conduct quality assurance oversight to implement the goals of DOE Order 414.1D.[33]

Naval Reactors officials told us that they rely on FMP to conduct routine safety and quality audits of the construction subcontractor as part of FMP’s management and oversight of the project. This is similar to Naval Reactors reliance on FMP to analyze performance baseline breaches, as discussed previously. In addition, according to Naval Reactors officials, the construction management subcontractor provides primary oversight of the construction subcontractors. Officials told us that FMP and the construction contractors’ quality assurance programs are independent, consistent with the definition of independence established by one of the project’s governing quality assurance standards; (American Society of Mechanical Engineers NQA-1). However, this standard requires “freedom from line management for the group performing independent assessments,” which, as explained below, the FMP audits did not have.

In addition, the FMP and construction contractor safety and quality audits are not fully independent under the definition established by DOE Order 414.1D, which requires assessments that are done by individuals within a company to be independent from the work or process being evaluated. Specifically, the audits were conducted by individuals in a company division that ultimately answers to project management, and who may not be in a position to objectively assess the project’s quality assurance program. Naval Reactors officials told us they do intrusive oversight of the contactor and subcontractors instead of using external entities to provide independent analysis. However, by using independent Naval Reactors or DOE offices not directly involved in the project to conduct non-routine assessments of the project’s quality assurance program, as is the practice for DOE capital asset projects, Naval Reactors management may have greater insight into the effectiveness of the project’s quality assurance program. Such assessments could identify weaknesses in the project’s quality assurance program that have led to work not meeting quality requirements, work stoppages, and rework.

Neither the Naval Reactors quality assurance requirements document (Implementation Bulletin Number 414.1D—86) nor the SFHP’s quality assurance plan included a provision instructing projects to complete independent assessments to measure the adequacy of work performance, and to promote improvement. However, one of the project’s governing quality assurance requirements, American Society of Mechanical Engineers NQA-1, states that regular scheduled audits should be supplemented by additional audits when a systematic independent assessment of program effectiveness is considered desirable and when it is suspected that quality is in jeopardy due to deficiencies in the quality assurance program.[34] Requiring independent assessment of the SFHP’s quality assurance program would provide Naval Reactors with greater assurance that its contractors are effectively overseeing the quality of work on the project and that underlying causes of prior quality assurance problems have been identified to prevent their recurrence.

Conclusions

Naval Reactors’ SFHP will be essential for efficiently managing the U.S. Navy’s spent fuel. The project has experienced significant cost growth and schedule delays. Naval Reactors manages the project’s prime contractor using a combination of Naval Reactors and DOE requirements. However, Naval Reactors’ cost and schedule estimates for its third performance baseline revision did not fully reflect selected best practices explicitly required to be applied by DOE requirements. By directing project contractors to develop cost estimates and schedules for the SFHP and future Naval Reactors projects that are consistent with best practices, Naval Reactors will have greater assurance that it can successfully achieve its plans and avoid persistent cost increases and delays.

Naval Reactors SFHP’s prime contractor identified certain causes of cost increases and schedule delays to the project but has not prevented further significant increases. Ensuring an independent root cause analysis of the SFHP’s cost increases and requiring such analyses in Naval Reactors implementation plans for future major projects would provide Naval Reactors with more reliable information to oversee construction project contractors and help avoid such issues going forward.

The project has also encountered significant quality assurance problems that have resulted in the need for project rework, cost increases, and delays. Naval Reactors has relied on project contractors to complete assessments and correct quality assurance problems. Requiring and directing Naval Reactors to conduct independent assessments of project quality assurance may give Naval Reactors greater assurance that its contractors are effectively overseeing the quality of work on projects and identify underlying causes of quality assurance problems to prevent their recurrence.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following six recommendations to the National Nuclear Security Administration’s Office of Naval Reactors:

The Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors should ensure that cost estimates for the SFHP adhere to GAO best practices for comprehensive and credible cost estimates, including ensuring the completion of an independent cost estimate. (Recommendation 1)

The Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors should ensure that schedules for the SFHP adhere to GAO best practices for credible schedules, including ensuring the completion of schedule risk analysis. (Recommendation 2)

The Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors should ensure completion of an independent and objective analysis of the root causes of the SFHP cost increases and delays. (Recommendation 3)

The Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors should update its Order 413.3B Implementation Bulletin to require implementation plans for major projects include a provision that triggers an independent and objective analysis of the root causes of cost increases when a breach of project performance baseline occurs. (Recommendation 4)

The Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors should ensure completion of an independent assessment of the SFHP quality assurance program. (Recommendation 5)

The Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors should update its Order 414.1D—86 Implementation Bulletin to require that a major construction project’s quality assurance plan include provisions for periodic independent assessments of the project to measure item and service quality, measure the adequacy of work performance, and promote improvement. (Recommendation 6)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to the National Nuclear Security Administration for review and comment.

In its comments, reproduced in Appendix III, the National Nuclear Security Administration agreed with the report’s six recommendations. The agency also provided technical and general comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

In its written comments, the National Nuclear Security Administration stated that it acknowledges the significant challenges SFHP has faced with cost and schedule growth and the contribution of factors such as poor construction subcontractor performance to these challenges. The agency stated that Naval Reactors has and will continue to pursue root causes and improvements in these areas to ensure SFHP is delivered as efficiently as possible. Further it stated that Naval Reactors will integrate the feedback from our review into its management processes, as appropriate, to ensure cost estimating, scheduling, and causal analysis processes best position the agency to resolve the significant issues SFHP faces and completion of the project.

We are encouraged by the National Nuclear Security Administration’s stated commitment to continuous improvement, and we look forward to the agency implementing our recommendations. We believe that action beyond that described by the agency may be required to implement two of the recommendations. Specifically, in response to our third and fifth recommendations that the National Nuclear Security Administration ensure completion of an independent and objective analysis of the root causes of the SFHP cost increases and delays and completion of an independent assessment of the SFHF project quality assurance program, the agency stated that it has already completed these recommendations. We disagree.

As stated in our report, to fully implement our recommendations, Naval Reactors should complete an independent and objective analysis of the root causes of the SFHP cost increases and delays and complete an independent assessment of the SFHF project quality assurance program. Assessments completed to date have been conducted or signed by project management staff or those who answer to project management staff. Independent analyses could be conducted, for example, by independent contractor staff, an external independent contractor, or an independent office within Naval Reactors or DOE, as is the practice for DOE capital asset projects. Such assessments would provide Naval Reactors management with objective analysis of the root causes of the project cost increases and delays and provide greater insight into the effectiveness of the project’s quality assurance program, ensuring that is not subjected to the potential influence of the contractor tasked with performing the work.

We are sending copies of the report to the appropriate congressional committees, Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors, the National Nuclear Security Administration Administrator, the Secretary of Energy, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-3841 or andersonn@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made significant contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Nathan J. Anderson

Director, Natural Resource and Environment

List of Committees

The Honorable Jack Reed

Chairman

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Patty Murray

Chair

The Honorable John Kennedy

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Chuck Fleischmann

Chairman

The Honorable Marcy Kaptur

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The objectives of this report are to (1) describe the Office of Naval Reactors’ (Naval Reactors) plans for managing its spent fuel, (2) assess the extent to which cost and schedule estimates for the Spent Fuel Handling Recapitalization Project (SFHP) exhibit key characteristics of reliable estimates, and (3) examine the extent to which Naval Reactors has analyzed the underlying causes of the SFHP cost and schedule increases and quality assurance problems.

To address these three objectives, we obtained documentation and interviewed officials with Naval Reactors, the Department of Energy (DOE), Naval Reactors contractors, and state officials with the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality that monitor compliance with the Idaho Settlement Agreement. Specifically, we interviewed Naval Reactors officials at both the Naval Reactors’ headquarters and the Naval Reactors Facility (NRF) at Idaho National Laboratory. We interviewed Naval Reactors officials within the Regulatory, Infrastructure & Security Division, and the Naval Reactors’ Government Affairs Division. Interviews with DOE officials included officials from the Office of Environmental Management, Nuclear Energy, and Office of Inspector General, Idaho Falls Audit Group. Interviews with Naval Reactors contractors included representatives from Fluor Marine Propulsion LLC, (FMP) which is the prime contractor overseeing the SFHP and, from Jacobs, which is the construction management subcontractor and is responsible for construction of the project.

To describe Naval Reactors and DOE plans for managing its spent fuel, we reviewed planning documents to identify the interim and long-term plans for the management and disposal of Naval Reactors’ spent fuel. Specifically, we reviewed Naval Reactors Idaho National Laboratory Naval Reactors Facility Integrated 10 Year Mission Plan and Long-Rang (30 Year) Mission Plan and briefing updates provided by Naval Reactors and contractor officials on these plans. In addition, we reviewed DOE’s April 2023 Consent Based Siting Process Plan—Federal Consolidated Interim Storage of Spent Nuclear Fuel provided by DOE’s Office of Nuclear Energy.

To assess the extent to which cost and schedule estimates for the new spent fuel facility project exhibit key characteristics of reliable estimates, we reviewed Naval Reactors reports and planning documents that describe the SFHP, including the history of performance baseline cost and schedule revisions for the project. During our review, Naval Reactors was managing the project against the project’s third performance baseline approved in September 2022 but had initiated development of a new, fourth performance baseline cost and schedule estimates. Because Naval Reactors was in the middle of developing new cost and schedule estimates for its fourth performance baseline revision during our engagement, we performed an assessment of cost and schedule estimates for the third performance baseline revision. We performed this assessment against selected best practices for cost estimation and schedule development published in the GAO Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide and the GAO Schedule Assessment Guide. While our analysis focused on the third performance baseline revision, it was sometimes necessary to examine documents from the original cost estimate and the prior cost baseline revisions for context.

Specifically, we assessed the cost and schedule estimates against the comprehensive and credible characteristics in the best practices guides. For the cost estimate analysis, this allowed us to assess the extent to which the project estimates were based on an adequate technical baseline and the approach taken to risk and uncertainty analysis. Similarly, for our analysis of the schedule, this allowed us to assess the extent to which the project schedule included the entire scope of the project and assess the approach taken to risk and uncertainty analysis. For our assessment of selected best practices, we applied the following scoring system: “Fully met” means that Naval Reactors provided complete evidence that satisfies the entire best practice criterion; “substantially met” means that Naval Reactors provided evidence that satisfies a large portion of the best practice criterion; “partially met” that Naval Reactors provided evidence that satisfies about half of the best practice criterion; “minimally met” that Naval Reactors provided evidence that satisfies a small portion of the best practice criterion; and “not met” that Naval Reactors provided no evidence that satisfies the best practice criterion. We determined the overall rating for a characteristic by rating each individual best practices comprising that characteristic and assigning it a number: Not Met = 1, Minimally Met = 2, Partially Met =3, Substantially Met = 4, and Met = 5. Then, we took the average of the individual assessment ratings to determine the overall rating for each of the four characteristics. The resulting average becomes the Overall Assessment as follows: Not Met = 1.0 to 1.4, Minimally Met = 1.5 to 2.4, Partially Met = 2.5 to 3.4, Substantially Met = 3.5 to 4.4, and Met = 4.5 to 5.0.

To determine the extent to which Naval Reactors has analyzed the underlying causes of the SFHP cost increases and quality assurance problems, we examined Naval Reactors and project contractor documents and interviewed Naval Reactors officials. This included examining actions taken by Naval Reactors and FMP to identify the scope and cause of performance baseline cost and schedule breaches and the quality assurance problems with the project. Specifically, to assess the causes of cost increases, we reviewed FMP’s reports requesting approval for each project performance baseline revision. These documents discussed causes identified by the contractor that led to cost increases and schedule delays. In addition, we reviewed Naval Reactors project management requirements and compared them to DOE Order 413.3B on project management of capital asset projects. We also visited the Idaho National Laboratory’s NRF to observe construction progress of the project and interviewed Naval Reactors and contractor officials responsible for managing the project. We also reviewed Naval Reactors contractor project quality assurance audit reports completed from April 2018 through February 2024 to understand the type and extent of quality assurance problems occurring on the project and Naval Reactors or its contractor’s analysis of the underlying causes.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 through December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our recommendations.

Appendix II: GAO Assessments of Naval Reactors Cost and Schedule Estimates for the Spent Fuel Handling Facility Project

We assessed the Office of Naval Reactors (Naval Reactors) cost and schedule estimates approved in September 2022 as part of the third performance baseline revision for the Naval Spent Fuel Recapitalization Handling Project (SFHP).[35] We compared these elements to selected best practices from GAO’s Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide and GAO’s Schedule Assessment Guide.[36] Tables 3 and 4 detail the results of our assessments.

SFHP Project Cost Estimates Compared to GAO Best Practices

Table 3 details our assessment of the Naval Reactors cost estimate used to develop the third performance baseline revision for the SFHP compared to selected best practices for project cost estimates published in GAO’s Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide.[37] We assessed the comprehensive characteristic because if a cost estimate is not complete, then it may not fully meet the other characteristics of a reliable cost estimate. We also assessed the credible characteristic because if an estimate is not credible, then it will not account for the elements that represent the most risk to the program. Because Naval Reactors was developing new estimates for a fourth revision to the project’s performance baseline during our audit work, we chose to conduct an abridged analyses for cost estimates and did not assess the well-documented and accurate characteristics.

According to our assessment, the Naval Reactors cost estimate for the third SFHP performance baseline revision partially met both the comprehensive and credible characteristics of a reliable estimate (see table 3).

Table 3: Assessment of Office of Naval Reactors Spent Fuel Handling Recapitalization Project (SFHP) Cost Estimates for the October 2022 Third Performance Baseline Revision Compared to GAO Best Practices

|

Best practice characteristic and overall assessment |

Best practice |

Detailed assessmenta |

|

Comprehensive: Partially met |

The cost estimate includes all life cycle costs. |

Partially met. Naval Reactors approved a Total Project Cost for Spent Fuel Handling Project (SFHP) Performance Baseline Revision 3 of $3 billion. The project execution plan identifies elements that are in-scope and out of scope. However, the plan did not provide a cost estimate that included all life cycle costs of the project. For example, although the project execution plan defined the operation and maintenance of the facility throughout its life as an out-of-scope cost, there was no indication of where these costs were accounted. Naval Reactors provided a document that contained additional information related to life cycle costs on the project, but it did not provide insight into estimated operations and maintenance costs, or the ground rules, assumptions, methodologies, and data used to estimate them. Naval Reactors provided a document that indicated a unified cost model exists and captures the total project estimate. However, all the values are hard-coded into the model. As a result, they do not provide adequate insight into the methodology used to develop the estimates. Naval Reactors officials said that the project accounts for life cycle costs in other ways, though they did not provide documentation for how the life cycle costs are accounted for. |

|

The cost estimate is based on a technical baseline description that completely defines the program, reflects the current schedule, and is technically reasonable. |

Partially met. Naval Reactors provided documentation of a technical baseline description. However, this information is not in one unified place. Furthermore, the scope of the project specifically excludes several elements that are typically part of a technical baseline – such as training and logistics. Without explicit documentation of the basis of a program’s cost estimates, it will be difficult to update the estimate and provide a verifiable link to a new cost baseline as key assumptions change during the program’s life. |

|

|

The cost estimate is based on a work breakdown structure that is product-oriented, traceable to the statement of work, and at an appropriate level of detail to ensure that cost elements are neither omitted nor double-counted. |

Substantially met. Naval Reactors’ work breakdown structure is a product-oriented structure with an associated, detailed dictionary for each element. The documentation of the third performance baseline revision did not report cost using the work breakdown structure. Costs were reported in the annual SFHP planning estimate, which is separate from the performance baseline revision process. |

|

|

The cost estimate documents all cost-influencing ground rules and assumptions. |

Partially met. Naval Reactors has documentation for the project’s cost estimate ground rules and assumptions. However, the information is incomplete and spread across multiple documents. |

|

|

Credible: Partially met |

The cost estimate includes a sensitivity analysis that identifies a range of possible costs based on varying major assumptions, parameters, and data inputs. |

Minimally met. Naval Reactors representatives we interviewed said that a project wide sensitivity analysis had not been performed since the 2019-2020 time frame at the latest. We found that Naval Reactors conducted a sensitivity study for the third performance baseline revision related to the potential impact of different rates of inflation on the estimated total project cost. However, the specific impact of this inflation sensitivity analysis was wrapped into the risk and uncertainty analysis and was not separately documented. |

|

The cost estimate includes a risk and uncertainty analysis that quantifies the imperfectly understood risks and identifies the effects of changing key cost driver assumptions and factors. |

Partially met. The SFHP has employed cost risk and uncertainty analysis since the original estimate and has used that analysis to drive the estimated total project cost. We found that the project cost risk and uncertainty analysis was generally detailed and based on Monte Carlo simulations. However, the risk ranges, cost impacts, and cost factors were largely based on subject matter expert judgement and not historical, quantitative data on either this project or similar projects. While data collected from subject matter experts is a valid estimating approach in the absence of better data, it also has the potential to be biased and should be used sparingly. |

|

|

The cost estimate employs cross-checks—or alternate methodologies—on major cost elements to validate results. |

Substantially met. In 2018, the program performed a detailed milestone cost review to approve the project to begin construction. Three teams of contractor personnel working separately from one another derived the estimate. While these efforts were not independent of the project and thus cannot be considered formal independent cost estimates, they can serve as cross-checks of the overall project estimate. |

|

|

The cost estimate is compared to an independent cost estimate that is conducted by a group outside the acquiring organization to determine whether other estimating methods produce similar results. |

Partially met. In September 2018, the Institute for Defense Analyses completed a detailed review of the project cost and schedule. According to project officials, this analysis was not a bottoms-up development of an independent cost estimate but was similar to an independent cost assessment. However, project officials did not provide an independent cost estimate for the third performance baseline cost estimate nor for the prior baseline cost estimates Without an independent cost estimate, decisionmakers will lack certain insights into a program’s potential costs. Independent cost estimates frequently use different methods, are less burdened with organizational bias, and tend to be more conservative by forecasting higher costs than the program office. |

Source: GAO analysis of Naval Reactors cost data. | GAO‑25‑106997

aFor our assessment of selected best practices, we applied the following scoring system: “fully met” means that Naval Reactors provided complete evidence that satisfies the entire best practice criterion; “substantially met” means that Naval Reactors provided evidence that satisfies a large portion of the best practice criterion; “partially met” that Naval Reactors provided evidence that satisfies about half of the best practice criterion; “minimally met” that Naval Reactors provided evidence that satisfies a small portion of the best practice criterion; and “not met” that Naval Reactors provided no evidence that satisfies the best practice criterion.

We determined the overall rating for a characteristic by rating each individual best practices comprising that characteristic and assigning it a number: Not Met = 1, Minimally Met = 2, Partially Met = 3, Substantially Met = 4, and Met = 5. Then, we took the average of the individual assessment ratings to determine the overall rating for each of the four characteristics. The resulting average becomes the Overall Assessment as follows: Not Met = 1.0 to 1.4, Minimally Met = 1.5 to 2.4, Partially Met = 2.5 to 3.4, Substantially Met = 3.5 to 4.4, and Met = 4.5 to 5.0.

SFHP Schedule Compared to GAO Best Practices

Table 4 details our assessment of the Naval Reactors schedule (i.e., the project’s integrated master schedule) used to develop the third performance baseline revision for the SFHP compared to selected best practices for project schedule published in GAO’s Schedule Assessment Guide.[38] Like the cost estimate assessment, we assessed the comprehensive and credible characteristics for the schedule. According to our assessment, the Naval Reactors schedule for the third SFHP performance baseline revision substantially met the comprehensive characteristic of a reliable schedule, but partially met the credible characteristic of a reliable schedule.

Naval Reactors manages and updates three tiers of schedules monthly: (1) low-level, detailed construction schedules managed by subcontractors; (2) a master schedule that summarizes subcontractor’s efforts and integrates engineering and other construction follow-on effort; and (3) a high-level integrated master schedule that integrates the master schedule with government activities and other construction work such as facility start-up and transition of operations. Our schedule analysis mainly examined the second-tier schedule managed by Jacobs, though it also examined the other schedule tiers as necessary.

Table 4: Assessment of Office of Naval Reactors Spent Fuel Handling Facility Recapitalization Project (SFHP) Schedule Estimates for the October 2022 Third Performance Revision Compared to GAO Best Practices

|

Best practice characteristic and overall assessment |

Best practice |

Detailed assessmenta |

|

Comprehensive: Substantially met |

Fully met. The success of a program depends in part on having an integrated and reliable master schedule that defines when and how long work will occur and how each activity relates to the others. Naval Reactors has an integrated master schedule for managing the entire program, and defines the schedule at an appropriate level to ensure effective management. |

|

|

Assigning resources to all activities |

Substantially met. While limited resources are included in the second-tier schedule managed by Jacobs, resources are loaded on lower-level subcontractor schedules, as well as the top-level integrated master schedule. Furthermore, program documentation provides guidance on estimating resources for discrete activities and resources are reviewed at each level of the three-tier schedule. However, we were not able to reconcile the total cost represented in the master schedule with the program’s estimated cost at completion. |

|

|

Establishing the durations of all activities |