OFFSHORE WIND ENERGY

Actions Needed to Address Gaps in Interior’s Oversight of Development

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Frank Rusco at ruscof@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106998, a report to congressional requesters

Actions Needed to Address Gaps in Interior’s Oversight of Development

Why GAO Did This Study

Offshore wind energy development in the U.S. is expanding. There are active wind farms and construction in the Atlantic and planned development off the Pacific coast and in the Gulf of Mexico. BOEM and BSEE are responsible for permitting and oversight of offshore wind projects. Numerous other federal agencies provide input throughout the process. As of January 2025, BOEM had granted 39 offshore wind leases to commercial developers, but on January 20, 2025, the President issued a memorandum that, among other things, prohibits agencies from new leasing, permits, or approvals for offshore wind projects pending a review of federal wind leasing and permitting practices. As the pace of offshore wind development has accelerated, state and local communities, Tribes, and non-government entities could experience the potential effects of offshore wind development.

GAO was asked to review offshore wind development in federal waters. This report examines (1) what is known about the potential impacts of offshore wind energy development, and (2) what mechanisms BOEM, in coordination with other agencies, has in place to oversee offshore wind energy development and to what extent they address potential impacts.

To examine potential impacts, GAO contracted with the National Academies to identify a panel of 23 experts to include diverse participant backgrounds and cover a range of potential impact categories. These include impacts to emissions, marine life and ecosystems, and maritime navigation and safety. Information obtained through expert interviews formed the basis of GAO’s findings on the potential impacts of offshore wind energy development.

GAO reviewed agency documentation related to federal management of potential offshore wind development impacts from lead agencies BOEM and BSEE, as well as coordinating agencies. These included project documents, memorandums of understanding between BOEM and federal partners, and studies. In addition, GAO reviewed studies and published research findings identified through a literature search, as well as prior GAO work, including a July 2024 Technology Assessment on approaches to address environmental effects of wind energy (GAO-24-106687).

To gather perspectives on potential impacts and federal oversight, GAO interviewed representatives from 22 Tribes and tribal organizations and multiple stakeholders from states, research institutes, fisheries, and industry, among others. GAO also interviewed officials from lead and coordinating agencies about potential impacts and their role in overseeing the offshore wind development and leasing process. To further examine mitigation of offshore wind impacts and discuss BOEM and BSEE oversight, GAO conducted two site visits to offshore projects with ongoing construction and operations activities.

What GAO Found

Offshore wind energy development has various potential positive and negative impacts in several areas. These include climate and public health, marine life and ecosystems, fishing industry, economic and community, tribal resources, defense and radar systems, and maritime navigation and safety impacts. However, because it is early in U.S. deployment of commercial offshore wind projects, the extent of some impacts is unknown. Moreover, uncertainty exists about long-term and cumulative effects, and the extent of impacts will vary depending on the location, size, and type of offshore wind infrastructure. Because of the lack of definitive research related to some impacts, GAO convened a panel of 23 experts with assistance from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) to identify and evaluate what is known about the potential impacts of offshore wind development.

Among such impacts, development and operation of offshore wind energy facilities could affect marine life and ecosystems, including through acoustic disturbance and changes to marine habitats. Wind development could bring jobs and investment to communities. At the same time, it could disrupt commercial fishing to varying degrees. Turbines could also affect radar system performance, alter search and rescue methods, and alter historic and cultural landscapes.

The Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) oversee offshore wind energy development. This is conducted through a multi-year permitting process that includes coordination with other agencies and stakeholders to identify and mitigate potential impacts.

However, Tribes have raised concerns regarding BOEM’s consultation with them. During initial planning of wind energy areas and when establishing wind lease areas, BOEM has taken steps to incorporate tribal input but has not consistently engaged in meaningful consultation with Tribes. BOEM documents indicate that it received tribal officials’ concerns but do not consistently demonstrate efforts to consider or address these concerns. BOEM officials acknowledged room for improvement and released a strategy for tribal engagement in December 2024. However, its implementation plan remains unclear. Clearly demonstrating and routinely reporting on its progress would help ensure that BOEM is adequately considering tribal concerns and building trust with Tribes. Also, nearly all tribal officials that GAO interviewed said that they do not have sufficient capacity to adequately review documents or meaningfully consult with government officials and developers. Agency officials stated that consultation has been hindered by limitations in BOEM’s statutory authority to provide support for tribal capacity building. Without a change to BOEM’s authority, tribal input and Indigenous knowledge may not be sufficiently incorporated into decisions.

BOEM has taken steps to inform fisheries stakeholders about its process and efforts to incorporate their input when establishing a lease area for offshore wind projects. However, stakeholders remain concerned that BOEM has not adequately considered or addressed the concerns of the commercial fishing industry and fisheries management councils at that stage of the permitting process. BOEM considers competing uses of the areas under consideration for development, including commercial fishing.

While BOEM has met with fishing industry representatives during the process, fishery stakeholders said they viewed BOEM’s responses to input as unclear or insufficient. Moreover, it is not clear how BOEM ensures that these stakeholders are consistently included in the process and informed of BOEM’s efforts to incorporate input from the industry when establishing lease areas. As a result, development of offshore wind energy could proceed without BOEM showing how it fully considers impacts to fisheries and how it will ensure developers address impacts to the fishing industry.

In addition, opportunities exist for BOEM and BSEE to improve enforcement of lessees’ community engagement. Lessees are to create community communication and engagement plans, but BOEM and BSEE have not established guidance for these plans. BOEM and BSEE also do not have a plan to monitor implementation and have not clarified their roles and responsibilities for monitoring implementation and enforcement. Without doing so, the agencies cannot ensure that they are fulfilling their oversight responsibilities or that lessees are effectively engaging with—and mitigating impacts to—affected communities.

Finally, BOEM and BSEE have not taken steps to ensure that they have the resources in place for effective oversight of offshore wind development. Specifically, neither agency has a physical presence in the North Atlantic region where offshore wind construction is underway. BOEM and BSEE officials stated that they are building capacity to oversee development. However, neither agency has taken the necessary steps to establish a physical office for that region, as they have done in the Pacific and the area formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico. Doing so will help ensure that BOEM and BSEE have the resources in place to oversee development in the region and effectively address potential impacts, engage with stakeholders, and oversee implementation of lease requirements.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Congress consider amending language in legislation to address BOEM’s limitations to providing adequate support for tribal capacity-building.

GAO is also making five recommendations to BOEM and BSEE, including that they address gaps in oversight related to (1) tribal consultation and incorporation of Indigenous knowledge; (2) consideration of input from the fishing industry; (3) guidance for communication and engagement plans; and (4) resources for oversight in the North Atlantic region. Interior agreed with all five recommendations.

For more information, contact Frank Rusco at (202) 512-3841 or ruscof@gao.gov

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

BOEM |

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management |

|

BSEE |

Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement |

|

COP |

construction and operations plan |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

EIS |

environmental impact statement |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

NEPA |

National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 |

|

NOAA |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

|

NOAA Fisheries |

NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service |

|

SEER |

U.S. Offshore Wind Synthesis of Environmental Effects Research |

|

UME |

unusual mortality event |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 10, 2025

Congressional Requesters

As the U.S. seeks to develop more renewable sources of energy, offshore wind energy development in the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf has expanded, including active wind farms and construction in the Atlantic and planned development off the Pacific coast and in the area formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico.[1] While the ability to harness offshore wind energy in the U.S. is in the early stages compared with European and some Asian countries, the federal government and 13 states have set goals to deploy offshore wind energy.[2] Specifically, as of May 2024, eight states had set procurement mandates for offshore wind capacity by 2040, and five additional states had set formal planning targets.[3] Legislation advancing renewable energy continues to be a significant trend, with many states working to meet specific goals for renewable energy or emissions reductions.[4] Greenhouse gas emissions contribute to climate change, which numerous studies have shown poses environmental and economic risks.

The Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), in coordination with the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), is the federal entity that oversees offshore wind energy development in federal waters, including the permitting of offshore wind projects.[5] These agencies are to engage other federal agencies, such as the Army Corps of Engineers, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, the United States Coast Guard, the Department of Defense (DOD), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and other federal agencies. In addition, they are to engage with Tribes and stakeholders, such as state and local governments and non-government entities through a complex, multi-year process for offshore wind projects.

As of January 2025, BOEM had granted 39 offshore wind leases to commercial developers on the Outer Continental Shelf. One lease has a fully operational project, four leases have projects under construction, and 11 more leases have projects in various stages of permitting review prior to construction (see table 1).[6]

Table 1: Operational and Planned Offshore Wind Projects for Leases Awarded by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), as of January 2025

|

Project |

Location |

Projected capacity in megawatts |

Status |

|

South Fork Wind |

35 miles east of Montauk Point, NY |

132 |

Operation |

|

Vineyard Wind 1 |

14 miles off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard, MA |

800 |

Under construction |

|

Sunrise Wind |

30 miles off the coast of Montauk, NY |

924-1034 |

Under construction |

|

Coastal Virginia Offshore Winda |

27 miles off the coast of Virginia Beach, VA |

2,500-3,000 |

Under construction |

|

Revolution Wind |

15 miles off the coast of RI |

704-880 |

Under construction |

|

New England Wind 1 |

30 miles south of Barnstable, MA |

791 |

Construction authorized |

|

New England Wind 2 (Commonwealth Wind) |

30 miles south of Barnstable, MA |

1,080 |

Construction authorized |

|

Southcoast Wind Energy |

20 miles south of Nantucket, MA |

2,400 |

Construction authorized |

|

Atlantic Shores South |

10-20 miles off the coast near Atlantic City, NJ |

1,510 |

Construction authorized |

|

Empire Wind 1 & 2 |

20 miles off the coast of Long Island, NY |

2,076 |

Construction authorized |

|

Maryland Offshore Wind |

12 miles off the coast of Ocean City, MD |

2,000 |

Construction authorized |

|

Vineyard Northeast |

29 miles from Nantucket, MA |

2,600 |

Permitting |

|

Vineyard Mid-Atlantic |

24 miles off the coast of Fire Island, NY |

2,000+ |

Permitting |

|

Atlantic Shores North |

10-20 miles off the coast near Atlantic City, NJ |

– |

Permitting |

|

Skipjack Wind |

15 miles off the coast of DE |

966 |

Permitting |

|

Kitty Hawk North & Southb |

27 miles off the coast of Corolla, NC |

– |

Permitting |

Legend: – = information not available as of January 2025

Source: GAO analysis of industry and BOEM information. | GAO‑25‑106998

Notes: This table includes offshore wind leases with projects that have submitted construction and operations plans. It does not include offshore wind leases with projects that are currently paused, including Beacon Wind (20 miles south of Nantucket, MA) and Ocean Wind 1 (15 miles southeast of Atlantic City, NJ). In addition to leases in federal waters, there is one operational offshore wind project, Block Island Wind Farm, in Rhode Island state waters. It generates approximately 30 megawatts per year.

aThe Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project is distinct from the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind Pilot, which consists of two turbines and generates 12 megawatts.

bPlans were announced in July 2024 to sell Kitty Hawk North, but as of January 2025, there have been no plans released detailing expected power generation or power purchasing agreements.

You asked us to review offshore wind energy development in federal waters. This report examines (1) what is known about the potential impacts of offshore wind energy development and (2) the mechanisms BOEM, in coordination with other agencies, has in place to oversee offshore wind energy development and to what extent they address potential impacts on Tribes and other stakeholders.

To examine both objectives, we reviewed agency documentation related to federal management of potential offshore wind development impacts. We interviewed representatives from a nongeneralizable sample of seven offshore wind developers and industries that may be affected by development, such as maritime shipping, renewable energy development, and undersea transmission cables. In addition, we interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of eight fisheries stakeholders.[7] We also interviewed officials from three state offices, representatives of three scientific research organizations, and four stakeholders from other industries that may be impacted by offshore wind development, such as maritime shipping, renewable energy development, and undersea transmission cables. We also spoke with representatives from 18 Tribes and four tribal organizations from the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. We reviewed agency documentation on tribal consultations and information provided by Tribes about potential offshore wind development impacts and federal consultation practices.[8]

We conducted site visits to the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind pilot project turbines and offshore construction area and the Vineyard Wind staging area in New Bedford, Massachusetts, to examine offshore wind construction and operations activities. We selected these sites to visit because they have ongoing offshore projects performing construction and operations activities. We also interviewed port authority officials, fishermen, and other stakeholders in New Bedford about offshore wind impacts to port operations and BOEM and BSEE oversight.

To examine what is known about the potential impacts of offshore wind energy development, we reviewed scientific literature identified through a literature search conducted by a GAO librarian. We contracted with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to identify a panel of 23 experts to interview about a range of potential impacts. We worked with the National Academies to identify a panel of experts to include diverse participant backgrounds such as academia, think tanks, advocacy groups, and organizations such as fishing industry and maritime shipping and security groups. The information we obtained through our expert interviews formed the basis of our findings on the potential impacts of offshore wind development. In consultation with our research methodologists, we developed a semi-structured question set we used in each expert interview and conducted content analysis to identify potential impacts and knowledge gaps the experts identified. Not all experts could speak to every impact, and thus we note how many made certain statements throughout the report. In most cases, we relied on expert testimony to describe impacts; however, in some cases, we relied on work we identified through our literature review to illustrate a point.

To examine the mechanisms BOEM, in coordination with other agencies, has in place to oversee offshore wind energy development, we reviewed agency documentation and interviewed agency officials about agencies’ roles and responsibilities and their oversight of offshore wind development planning, construction, and operations. Appendix I provides additional details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to April 2025, in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

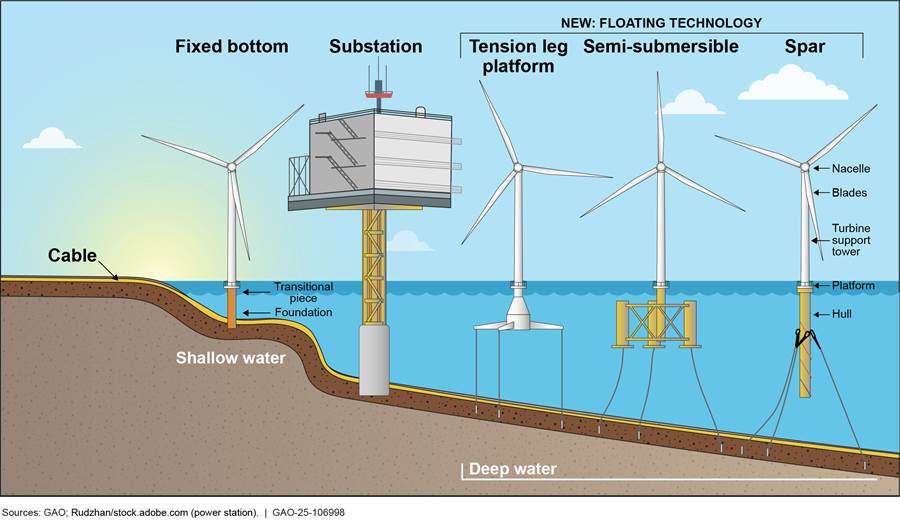

Wind turbines generate electricity by turning blades around a rotor, spinning a generator to create electricity. Electricity generation depends on wind speed and blade length. Power generated from offshore wind turbines is transmitted to shore through cables laid along the seafloor or buried. Power may be converted at offshore substations and then transmitted to onshore substations where it can be distributed to homes and businesses.

Companies developing offshore wind projects are deploying or planning to deploy two types of offshore wind turbines in the U.S.: fixed bottom and floating. Fixed bottom turbines—currently deployed—are generally suitable for shallow waters (less than 200 feet in depth), such as the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf and the area formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico. Floating turbines, for which the technology is under development, are better suited for deeper waters such as the Pacific and Gulf of Maine (see fig. 1).

Note: Fixed turbines are planned in shallow water less than 200 feet in depth. Floating turbines are planned in deeper water greater than 200 feet in depth.

Larger turbines are grouped together into wind farms, which provide electricity to the power grid. Offshore turbines—often taller than the Statue of Liberty—tend to be taller than onshore turbines and can capture powerful ocean winds. The average turbine height for offshore turbines in the U.S. was about 300 feet in 2016 and is projected to increase to about 500 feet by 2035.[9]

The Federal Role in Offshore Wind Energy Development

The Department of the Interior’s BOEM is the primary agency overseeing the siting, review, and approval of wind energy projects in federal waters.[10] According to BOEM, its mission is to facilitate the responsible development of renewable energy resources on the Outer Continental Shelf through conscientious planning, stakeholder engagement, comprehensive environmental analysis, and sound technical review. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 mandated the development and issuance of regulations for the Outer Continental Shelf Renewable Energy Program.[11] The resulting BOEM and BSEE regulatory framework establishes a process for environmental and technical review of proposed offshore wind projects through each stage of development.[12]

Each project is subject to review under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA).[13] Specifically, NEPA requires agencies to prepare a detailed statement of environmental effects.[14] Under the procedures applicable during the time of this review and as of March 2025, this has typically taken the form of an environmental impact statement (EIS).[15] But where it is unclear whether an EIS is required for a particular agency action or decision, or the impacts are known not to be significant, the agency may first or instead prepare an environmental assessment, a more concise analysis. As part of its evaluation, the agency must consider reasonable alternatives to the proposed action, including a no-action alternative, as well as appropriate measures to mitigate environmental effects. At various agency decision points in the offshore wind development process, BOEM may prepare an EIS, an environmental assessment, or other documentation to comply with NEPA. BOEM also consults with the NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries) under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 and the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976 (Essential Fish Habitat) and Fish and Wildlife Service under the Endangered Species Act of 1973.[16] BOEM also conducts consultations with Tribes and other affected parties pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.[17]

State and local governments generally provide primary approval for projects not on federal lands or outside of, but landward of, federal waters. Any wind energy project or facility associated with such a project to be constructed in state waters, including any cables that would be necessary to transmit power back to shore, is subject to applicable state regulation or requirements. The Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 encourages states to develop and implement coastal zone management programs and plans to balance protection of habitats and resources in coastal waters with other interests, and to coordinate with federal agencies.[18]

Other state and federal agencies have additional roles and authority in the offshore wind project approval process, including the Marine Mammal Commission, under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.[19] Furthermore, agencies may also contribute expertise and information to the process. For example, the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Wind Energy Technologies Office invests in activities that enable and accelerate innovations to advance onshore and offshore wind, while continuing to address market and other barriers to commercial deployment.

Federal agencies are to consult with Tribes on many infrastructure projects and other federal activities—commonly referred to as tribal consultation. Specifically, offshore wind development may involve various federal activities that trigger statutory and regulatory tribal consultation requirements, such as those under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended.[20] In addition, executive directives call for federal agencies to consult with federally recognized Tribes on activities that may have tribal implications.[21]

Offshore Wind Energy Development Has Both Positive and Negative Potential Impacts, and Research to Understand and Address Some Effects Is Ongoing

Offshore wind energy development has various positive and negative potential impacts in several areas. These include impacts on climate and public health, marine life and ecosystems, fishing industry, economic and community, tribal resources, defense and radar systems, and maritime navigation and safety (fig. 2). The extent of impacts will vary depending on the location, size, and type of offshore wind infrastructure. Also, developers can implement measures to avoid or mitigate potential impacts.[22] However, because technology and implementation are still developing, the extent of some impacts is unknown. In addition, uncertainty exists about long-term and cumulative effects, but research and monitoring activities are ongoing to better understand potential impacts.

Deployment of Offshore Wind Could Have Positive Climate and Public Health Benefits

Offshore wind energy deployment could have positive climate and public health impacts, according to experts we spoke with and documents we reviewed. Three experts told us that, to the extent that offshore wind replaces fossil fuel energy sources, deployment of offshore wind could reduce greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change. And two of the experts also said it could improve public health outcomes through improvements in air quality. According to an October 2024 analysis, deployment of the currently planned or proposed offshore wind farms in the Atlantic and Gulf coasts could reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 5 percent by 2035.[23] One expert we interviewed also told us that offshore wind can complement other renewable energy sources, such as solar, during periods of high energy demand. Another expert said that wind can enhance the benefits of electrified vehicles and homes by compounding emissions reductions.

Reducing reliance on fossil fuels by adopting resources like offshore wind could also reduce pollutants that affect public health.[24] Communities near fossil fuel power plants, including disadvantaged communities, would likely see the greatest health benefits from a transition to renewable energy sources, though smaller positive benefits would still be seen in large geographic regions, according to one expert we interviewed.[25] The expert added that disadvantaged communities may also experience some negative impacts from offshore wind energy development, such as environmental and health effects from increased emissions and pollution from onshore and near-shore construction, but those negative impacts are unlikely to cancel out the benefits of reduced fossil fuel use.[26]

Offshore Wind Development Could Have a Variety of Impacts on Marine Life and Ecosystems, but Research Is Ongoing

The development and operation of offshore wind energy facilities could have a variety of impacts on marine life and ecosystems. These include acoustic disturbance from survey and construction activities, changes to marine habitats from the installation of offshore wind structures, hydrodynamic and wind wake effects from wind turbine operations, and physical risks to marine life and birds from wind structures and new vessel activity, according to experts we spoke with and documents we reviewed (see table 2).

|

Impact |

Description |

|

Acoustic disturbance |

Construction and survey activities produce underwater noise that can disturb sensitive marine species. Offshore wind projects take measures to mitigate underwater noise, including the use of bubble curtains to dampen pile driving sound and pausing operations if protected species are sighted. |

|

Changes to marine habitat |

Installation of infrastructure, such as turbine foundations and transmission cables, introduces new structures and causes changes to the ocean floor that can alter marine habitat and affect the distribution, abundance, and composition of marine life in the area. These new structures can create artificial habitat that may benefit some species while displacing others and could affect bottom-dwelling species through disturbing the seabed. Artificial habitat effects of wind turbines are well documented, but research is ongoing to monitor and understand impacts on marine life. |

|

Hydrodynamic effects |

Operation of wind turbines can affect hydrodynamics and ocean processes such as currents and wind wakes, but little is known about regional effects of widescale deployment on ecosystems. |

|

Vessel disturbance |

Vessels can disturb some species and pose strike risks to large marine animals, but the increase in offshore wind vessels is projected to be small compared to the total volume of vessel traffic. Offshore wind vessels are required to take measures such as following speed restrictions and employing protected species observers. |

|

Entanglement risk |

Structures, such as mooring cables from floating wind turbines, could snag fishing gear and other marine debris and create entanglement risk to marine animals. Wind projects employ measures to minimize entanglement (e.g., mooring systems designed to detect entanglement), but there is uncertainty about the extent of the risk from floating turbines because of limited deployment.a |

|

Collision risk to birds and bats |

Turbine blades pose a collision risk to some sea birds, but little is known about offshore collision risk to bats. Research on collision risks and mitigation measures (e.g., lighting and curtailment) is ongoing. |

Source: GAO review of documents and expert testimony. | GAO‑25‑106998

aThere are no floating offshore wind projects operating or under construction currently in the U.S., but a pilot project is in development in the Gulf of Maine.

According to eight experts we interviewed, some potential impacts of offshore wind development to marine life and ecosystems are not well understood, but research and monitoring is ongoing or planned. In addition, seven experts said that because there are variations in species and ocean conditions, known impacts from existing wind farms may not apply to other offshore wind projects. They added that the extent of the impacts depends on many factors, such as the location, size, and type of offshore wind infrastructure.

Moreover, changing ocean conditions due to climate change and other human activities are making it difficult to understand the potential effects of offshore wind development, according to five experts we spoke with and documents we reviewed. According to the Fifth National Climate Assessment, climate change is altering marine ecosystems and causing marine species to change their distribution, seasonal activities, and behaviors.[27] Three experts we interviewed also told us that climate change is rapidly altering marine species behavior and habitats, making it difficult to obtain baseline data on the ocean and species populations. One state official said lobster populations have already migrated away from state waters because of warming ocean temperatures.[28]

Additional detail on each of the potential impacts on marine life and ecosystems follows.

Acoustic Disturbance from Surveys and Construction

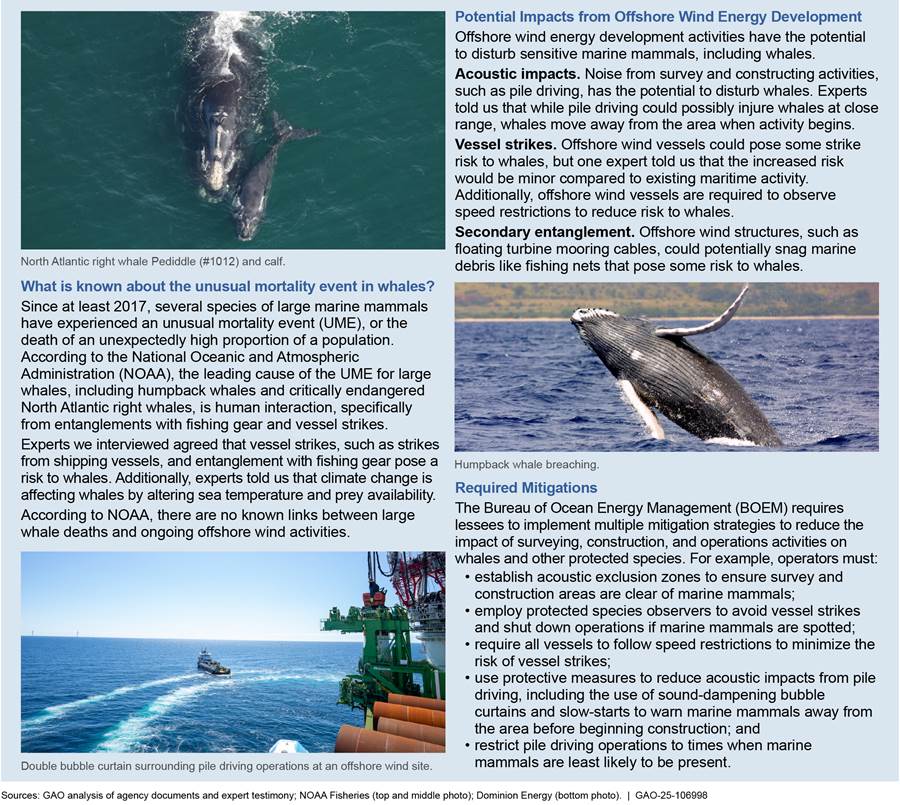

Offshore wind development has the potential to affect marine animals sensitive to underwater noise, such as whales. Such impacts can occur through activities such as sea floor mapping and construction, according to experts we spoke with and documents we reviewed. Offshore wind development activities produce varying levels of underwater noise throughout each phase of development and operation. Specifically,

· Developers explore potential wind generation sites using high resolution geophysical surveys, which may disturb sensitive species. BOEM determined that these surveys are unlikely to injure marine mammals, and two experts we interviewed said that surveys for oil and gas development on the Outer Continental Shelf has used more powerful survey acoustic tools without resulting in whale strandings.[29]

· Construction activities, such as pile driving fixed-bottom turbine pylons into the sea floor, can create intense undersea noise that could cause disturbance or potential injury to marine mammals.[30] Three experts told us that, while pile driving could cause auditory injury to marine mammals at short ranges, animals tend to move away from construction areas when activity begins.

· Consistent, low-intensity noise from the operation of turbines is similar to existing ambient sound in the ocean and has a very low probability of causing potential harm to fish and marine mammals, according to a 2023 BOEM-commissioned study.[31]

· Dismantling offshore wind turbines at the end of their operational period may result in moderate undersea noise for a limited period.[32] While no offshore wind farms in the U.S. have reached the end of their operational lifespan, BOEM will conduct an environmental assessment of any proposed decommissioning activities.

Offshore wind developers take measures to mitigate these impacts via long-term monitoring of noise as well as whale and fish vocalizations in the lease area before, during, and following construction. Additional monitoring and mitigation measures include (1) the use of bubble curtain technology to dampen pile-driving noise, (2) employing protected species observers and using acoustic monitoring technology to ensure construction areas are free of marine mammals, and (3) restricting construction activities to times when sensitive species are less likely to be in the area.

NOAA Fisheries does not anticipate any death or serious injury to whales from offshore wind related actions and has not recorded marine mammal deaths from offshore wind activities.[33] However, one expert we interviewed said there is some uncertainty about sound thresholds that marine mammals can endure before injury occurs because researchers cannot ethically test such conditions on marine mammals. Studies are ongoing on these acoustic effects. BOEM’s Center for Marine Acoustics supports research on underwater noise and promotes policies to address acoustic impacts of offshore wind activities.[34] NOAA Fisheries has also released new draft technical guidance for assessing noise impacts on marine mammals.[35] In addition, BOEM and NOAA are coordinating to evaluate and mitigate the potential impacts on the critically endangered North Atlantic right whales.[36]

Changes to Marine Habitats from Infrastructure

The installation of offshore wind infrastructure can affect marine habitats through changes to ocean and sea floor compositions. These changes may result in beneficial effects for some species while potentially displacing others, according to experts we spoke with and documents we reviewed. According to DOE’s U.S. Offshore Wind Synthesis of Environmental Effects Research (SEER) project, installation of offshore wind infrastructure is known to change the composition of the seabed and create structures that affect the behavior of marine life.[37] The increased levels of sediment during ocean construction may disrupt marine life for a limited time, but the introduction of structures and changes to the sea floor can create various positive long-term changes to marine habitat. For example, seven experts we interviewed told us that the insertion of the offshore wind structures can create new habitat that benefits some fish and other marine life, known as an artificial reef effect. Three experts said that this artificial reef effect has been demonstrated on multiple offshore wind projects, including several European offshore wind facilities as well as the Block Island Wind Project in Rhode Island.

However, two experts told us there is uncertainty about the extent to which new habitat created by offshore wind infrastructure increases fish productivity versus attracting existing species from other areas. Furthermore, although these changes can benefit some species, they may also displace existing marine life. One expert we interviewed said that seabed disturbance may disrupt scallop populations. Another expert pointed out that new habitats may also create favorable conditions for invasive species. According to DOE’s SEER report, infrastructure transported to installation sites may introduce invasive species.[38]

In addition to turbine structures, submerged power cables connecting offshore wind facilities with shoreside distribution networks have the potential to disrupt habitat and may affect the behavior of some sensitive species. The DOE’s SEER project reported that the burying of undersea power cables disturbs the seabed, potentially disrupting bottom-dwelling marine life and causing temporary changes to sediment and water composition. The SEER project also reported that some species may be sensitive to electromagnetic frequencies emitted by transmission cables, but it noted there is not conclusive evidence to suggest frequencies from offshore wind infrastructure will impact marine life.[39] One expert we interviewed said there are not significant electromagnetic impacts to marine life from a single cable, but more research is needed about potential cumulative impacts as the number of cables increases.

Offshore wind infrastructure also poses some risk of marine debris and pollution, which could include oil leaking from the turbine or debris from a structural failure. For example, following a blade failure off the coast of Massachusetts, fiberglass debris fell into the ocean and washed onshore in surrounding communities.

Hydrodynamic Effects from Turbine Operations

Offshore wind could have effects on wind currents and ocean circulation that could affect marine life, but there is uncertainty about the extent of these effects, according to two experts we spoke to and documents we reviewed. According to a National Academies study, wind turbines create localized hydrodynamic effects—such as changes in water temperature, turbulence, and nutrient availability.[40] However, two experts told us that regional effects of wind farms on ocean circulation patterns are difficult to quantify because of the lack of data and other natural and anthropogenic factors, such as warming waters due to climate change. Furthermore, two West Coast fisheries stakeholders and a representative from one Tribe told us they are concerned that changes to upwelling could impact other marine species and fisheries along the Pacific coast.[41] NOAA Fisheries has set a research priority of understanding oceanographic effects, including upwelling.[42]

Vessel Traffic Impacts on Marine Life

Vessel traffic associated with offshore wind construction and operations could have impacts on marine life. These include disturbance of marine species from vessel noise and some risk of vessel strikes on large marine animals, such as whales, according to experts we spoke with and documents we reviewed. Four experts told us that vessel activity during offshore wind development and operations poses some risk of vessel strikes. However, a study of planned offshore wind traffic found that the increase in offshore wind vessel activity is projected to be small compared to the total volume of vessel traffic anticipated over time.[43] According to NOAA Fisheries—the agency responsible for tracking vessel strikes—there are no known links between offshore wind energy development and large whale deaths.[44] Furthermore, vessels involved in offshore wind activities take measures to minimize strike risk, such as observing speed restrictions and employing observers to monitor and report marine mammal activity.[45]

Entanglement Risk

Offshore wind development may also pose some risk of entanglement with offshore wind infrastructure and other marine debris, according to experts we interviewed and documents we reviewed. According to DOE’s SEER project, the likelihood of marine life becoming directly entangled with offshore wind cable systems is low, but there is a greater risk of secondary entanglement—entanglement with debris such as fishing nets snagged on offshore wind structures.[46] One expert we interviewed said that floating wind structures pose an entanglement risk because of the length of the mooring cables needed to anchor turbines to the ocean floor. Wind project developers employ some measures to mitigate entanglement risk, such as using mooring systems designed to avoid entanglement and monitoring and reporting any entanglements. That said, the SEER project stated that little is known about secondary entanglement risks of floating wind mooring cables because limited offshore wind development has occurred.[47] Currently, floating wind farms are not operational in U.S. waters, but a pilot project is under development in the Gulf of Maine.

Collision Risk to Birds and Bats from Turbines

Offshore wind turbines may pose risks to bird and bat populations in the offshore environment, according to experts we interviewed and documents we reviewed. According to DOE’s SEER project, sea birds are at risk of colliding with offshore wind turbine blades, though activity may vary at certain times of the day or year, such as during seasonal migration. Species that roost on artificial structures or prey on marine life around turbine structures are at greater risk of collision. Furthermore, the project found that many species at risk of collision are in decline because of existing stresses, such as the effects of climate change and human activity. Similarly, some bat species may be at risk of collision with wind turbine blades, but less is known about offshore collision risk to bats. While onshore wind turbines pose a known collision risk for bats, it remains unclear whether offshore wind development poses a significant risk, according to DOE’s SEER project and one expert we interviewed.[48]

There is some research on bird collision risk around European offshore wind farms, but data on bird and bat collision risk in the U.S. are limited because of the limited deployment of offshore wind projects as well as challenges monitoring and collecting affected animals in an offshore environment.[49] Developers can implement mitigation measures to minimize impacts to birds and bats. These measures include installation of devices to deter birds from perching on wind turbines and developing monitoring plans to enhance understanding of bird and bat impacts.

Offshore Wind Development Could Have Negative Impacts on the Fishing Industry and Fisheries Management

Offshore wind development could have negative impacts on the fishing industry. These impacts include restricting access to fishing grounds and preventing fishery surveys in areas of development, according to experts and fisheries stakeholders we spoke with and documents we reviewed. For example, offshore wind development could impede or prevent access to certain fishing grounds and impact the livelihood and safety of commercial fishermen. For example, fishing near offshore wind turbines would not be possible for scallopers, according to four fisheries stakeholders familiar with the scallop industry. Scallopers use fishing gear that could become entangled with transmission cables or structures installed to cover and protect seabed cables. The loss of access to fishing grounds could result in a loss of income for commercial fishermen in certain areas.[50] However, recreational fishermen may benefit from increased and more varied fish stocks around wind turbines in some areas.[51] One expert and three fisheries stakeholders we spoke with from different geographic regions said recreational fishermen were optimistic about fishing opportunities near the new wind turbine structures.

In addition, fishermen were concerned that fishing around offshore wind turbines may not be allowed or safe, according to six fisheries stakeholders. However, as of December 2024, according to BOEM documentation, the Coast Guard had not implemented or announced restrictions on fishing activities around offshore wind turbines in operation on the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf.[52] Four fisheries stakeholders told us that there are also concerns about insurance for commercial fishermen, including that the cost of insurance could increase or that it could be denied to vessels that operate near offshore wind turbines. One fisheries stakeholder noted that floating offshore wind turbines could pose additional risks, and that even some recreational fishing vessels may be barred from floating offshore wind arrays because their fishing gear could become tangled on the turbine mooring cables.

Moreover, offshore wind development could also affect the quality of data used to manage fisheries by making data collection in lease areas difficult or impossible, according to four fisheries stakeholders. Specifically, NOAA monitors species abundance data using bottom trawling gear that inform fisheries management policies and the levels of fish that fishermen can harvest. If accurate data are not available, fishery management council officials told us they would likely implement more conservative policies, limiting the number of fish that can be harvested. This could lead to reduced income for fishermen and could also lead to increased fish stocks since fishermen would not be allowed to harvest as many fish.

The primary planned mitigation strategy for commercial fisheries is compensation from offshore wind developers. The Fisheries Mitigation Project—organized by 11 East Coast states—seeks to provide a regional framework to compensate commercial fishermen for economic losses due to offshore wind energy development.[53] Seven fisheries stakeholders expressed concern about how compensation would work, including worries that the Fisheries Mitigation Project could not support fishermen over the lifetime of offshore wind projects and that it may be difficult to prove that fishermen worked in the areas before construction. The Fisheries Mitigation Project is still in development, and procedures for applying for compensation have not been established.

Offshore Wind Development May Have Various Economic Development and Community Impacts

Economic development. The development and operation of offshore wind energy facilities could result in economic and community development, including creating jobs and investments in ports and communities, according to experts we interviewed and documents we reviewed. For example, multiple port modernization projects are underway in Massachusetts.[54] In addition, the offshore wind industry could create thousands of jobs to support manufacturing and development, according to federal and state reports we reviewed.[55] However, the number of net jobs created may vary by project and location, and the net benefits to local economies could be negligible in some cases, depending on the extent of potential loss of jobs in the fishing industry. While some fishing operations are mitigating income loss by working for offshore wind energy developers (e.g., providing safety perimeters during turbine construction), it is difficult to know the extent of offshore wind’s overall economic impact on the communities. For example, cities like New Bedford, Massachusetts, have onshore industries and infrastructure that support seafood harvesting, including ice suppliers and seafood processors, that could be impacted.

Cultural and community impacts. Offshore wind development may affect communities in other ways. For example, fishing communities may see cultural shifts if commercial fishing becomes less economically viable due to offshore wind projects, according to officials we interviewed and documents we reviewed. Communities that have developed around the fishing industry, with multi-generational ties to fishing, may be displaced, according to one representative of a coastal community. Furthermore, some members of coastal communities have also raised concerns about potential impacts to some cultural sites, such as viewsheds and shipwrecks located in wind lease areas or along transmission cable routes. Representatives of coastal communities and those charged with historic preservation duties also said that historic districts or houses with views of the coastal horizons could be impacted by offshore wind installations. The presence of wind farms could diminish the integrity of historic properties whose key characteristics include associated views of the ocean or a maritime environment, according to officials from the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. Some developers plan to compensate communities affected by impacts to viewsheds through community development funds, according to developer documents.

Offshore Wind Development Could Negatively Affect Tribal Resources, Including Sacred Sites and Established Fishing Grounds

Offshore wind development, including the installation of infrastructure such as turbines and undersea cables, have the potential to disturb submerged sacred sites, restrict access to established tribal fishing grounds, and alter viewsheds with cultural and religious importance, according to tribal officials we spoke with and documents we reviewed.

Impacts to Sacred Tribal Sites and Viewsheds

Submerged archaeological sites, which include sacred tribal sites and may contain tribal artifacts and human remains, can be disturbed or damaged when offshore wind developers conduct seabed surveys or lay cables, according to several representatives from Tribes and tribal organizations. Thousands of years ago, ancestral lands extended into what is now the ocean, such as in the Heceta Banks, Oregon, and Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, areas. Development such as cable landings could also affect onshore archaeological sites of tribal significance.

Offshore wind development could also change viewsheds with religious and cultural importance by disrupting historically uninterrupted horizons. The sunrise and sunset have important religious or cultural meaning to several Tribes on the East and West Coasts, according to representatives from several Tribes. For example, one tribal official told us that the lights from offshore wind turbines may disrupt traditional prayer and dance ceremonies.

Restricted Access to Tribal Fishing Grounds

Offshore wind energy development can also affect tribal access to established fishing grounds, according to many tribal representatives we spoke with. On the West Coast, several Tribes have treaties that guarantee access to established (usual and accustomed) fishing grounds in the Pacific Ocean. There are currently no leased or proposed wind energy areas that overlap with these established fishing grounds, but, according to one tribal official, offshore wind activities in other areas of the Pacific could affect spawning or migration of the fish harvested from the established fishing grounds. One expert also told us that displaced fishermen from offshore wind areas might relocate to established tribal fishing grounds, causing overcrowding.

Moreover, because offshore wind development poses potential risks to marine life, it could also pose risks to Tribes’ ability to fulfill their ocean stewardship responsibilities. As stewards and co-stewards of the ocean, some Tribes on the East and West coasts are responsible for protecting the environment and wildlife, according to representatives from several Tribes.[56]

Offshore Wind May Have Impacts on Defense and Radar Systems

Wind turbines can reduce the performance of radar systems used for defense and maritime navigation and safety in several ways. These include reducing detection sensitivity, obscuring potential targets, and generating false targets, according to a DOE report.[57] In addition, offshore wind energy development may affect larger military exercises by obstructing flight and surface and subsurface vessel movement, according to DOD officials.

Wind turbines are constructed predominantly of steel that has a high electromagnetic reflectivity, according to a 2022 National Academies report.[58] As a result, the turbines and rotating blades can make it hard to see targets on different radar systems, including high-frequency and marine vessel radar.[59] The breadth and magnitude of the potential impacts to radar systems will not be fully known until more offshore wind structures are built in U.S. waters, according to one expert. Several factors influence the extent to which radar systems are affected by offshore wind turbines. According to two experts we interviewed, the position, height and spacing of offshore wind turbines can affect how much interference occurs, including whether a wind farm is in the line of sight between a radar system and the targeted region.

Some mitigation strategies exist, or are under development, to address radar interference. For example, DOD can request the exclusion of areas from consideration for wind energy activities if the agency identifies critical impacts that cannot be mitigated. DOD also has agreements with lessees to temporarily curtail operations if needed. In addition, NOAA and researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute are developing software to reduce interference. There is also ongoing research on radar software and systems and infill radar, or smaller radar systems placed within an offshore wind farm, to further mitigate impacts, according to one expert.

Offshore Wind Turbines Could Have a Variety of Impacts on Maritime Navigation and Safety

Offshore wind arrays constructed close to existing shipping lanes may increase the risk of vessels colliding with offshore wind infrastructure or other vessels, according to experts we interviewed and documents we reviewed. For example, one expert told us that large shipping vessels may have trouble avoiding turbines in the event of a mechanical failure due to the wide turning radius—a large shipping vessel may need up to 2 nautical miles to properly maneuver. The expert also said that wind turbines may obscure smaller vessels on radar, and when smaller vessels emerge from an offshore wind farm, a large shipping vessel may not have enough time to avoid a collision. In addition, two fisheries stakeholders expressed concerns that turbines could affect search and rescue operations in or around turbines. For example, aircraft conducting search and rescue missions may not be able to fly as low to the water because of turbine heights, according to Coast Guard officials. However, one Coast Guard official told us that offshore wind turbines, similar to radio towers, are one of many factors considered when planning for search and rescue. Coast Guard officials also said wind turbines may affect the accuracy of water current models used to predict vessel or person movement, but they are working on new models to address this challenge. Some of these navigation and safety impacts can be mitigated by limits on construction and siting, such as ensuring minimum distances between shipping lanes and wind turbines.

BOEM’s Oversight of Offshore Wind Development Includes Coordination with Agencies, Tribes, and Stakeholders to Address Impacts, but Opportunities for Improvement Exist

BOEM—and later in the process BSEE—oversees offshore wind energy development through a multi-year permitting process, including coordination with other federal agencies and stakeholders to identify lease areas and obtain information to identify and mitigate potential impacts. However, several gaps exist in BOEM’s process for ensuring adequate consultation with Tribes and engagement with fisheries. In addition, opportunities exist for BOEM and BSEE to improve enforcement of community engagement, increase capacity, and establish data sharing requirements.

BOEM’s Permitting Process Includes Coordination with Multiple Agencies and Stakeholders to Identify and Mitigate Potential Impacts

Throughout the offshore wind permitting process, BOEM obtains input from multiple federal agencies, state governments, Tribes, and other stakeholders to identify and mitigate potential impacts of offshore wind energy projects.[60] BOEM’s process also requires lessees to report on monitoring of impacts, mitigation strategies, and plans for stakeholder engagement.

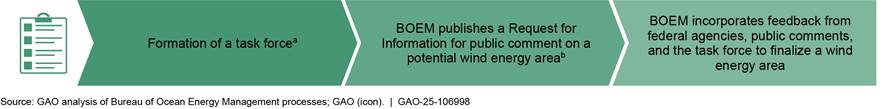

Planning and Analysis. The Planning and Analysis phase of the offshore wind energy permitting process, as outlined in figure 4, typically begins with BOEM forming a task force, either at the request of a state governor or at BOEM’s discretion. BOEM then publishes a Request for Information for public comment on the potential lease area to inform its definition of a final wind energy area.

Figure 4: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) Offshore Wind Energy Permitting Process—Planning and Analysis Phase

aA task force may be composed of representatives invited from federal agencies, as well as those of affected states, federally recognized Tribes, and local governments. State agency representatives can include, but are not limited to, officials from public utilities, environmental protection agencies, port authorities, and state historic preservation offices.

bBOEM requests information through public comments, including information on existing uses of the proposed areas; potentially affected archaeological sites; geological conditions; and other socioeconomic, biological, and environmental information for the proposed area. BOEM also issues a Call for Nominations to the public to gauge developer interest and a Notice of Intent to Conduct an Environmental Assessment, on which the public may also comment.

Task force meetings provide BOEM and those invited representatives a forum to exchange information on a specific offshore wind project, according to BOEM guidance. For example, entities like DOD and NOAA Fisheries participate in such task forces and can identify and recommend areas to avoid based on national defense needs or the location of essential fish habitats, respectively. A task force can continue to provide feedback to BOEM throughout all phases of the permitting process. The public comment period is one of a few required points during the permitting process where the public, Tribes, and other affected stakeholders, such as fishing and shipping industry representatives, can provide feedback on potential impacts and concerns to BOEM. BOEM must respond to the submitted comments.[61]

Leasing. During the Leasing phase, BOEM reviews preliminary financial information from interested developers to review eligibility. BOEM then holds an auction to offer a commercial lease located in the identified wind energy area.[62] BOEM forwards the winning bid to the Department of Justice for an antitrust review and publishes the preliminary auction results on its website. Lessees sign lease agreements with BOEM, which can include stipulations like the development of communication and engagement plans for affected Tribes, communities, and stakeholders.[63]

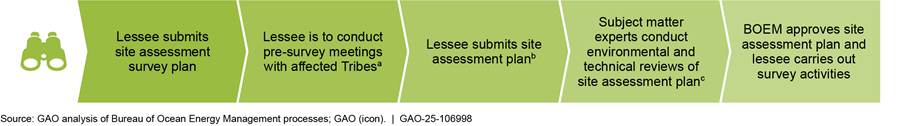

Site Assessment. The Site Assessment phase, as shown in figure 5, requires the winning lessee to submit a survey plan to BOEM that details the company’s plans and timelines to survey the lease area for environmental, technical, and other potential impacts.

Figure 5: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) Offshore Wind Energy Permitting Process—Site Assessment Phase

aBOEM provides guidance to lessees that recommends how to engage with stakeholders and Tribes. This pre-survey meeting is the only explicitly required meeting for lessees to conduct, according to BOEM’s internal procedures.

bSite assessment plans include initial surveys and research activities necessary to characterize a lease site.

cSubject matter experts, such as geologists and engineers, from BOEM and BSEE conduct technical reviews to evaluate the proposed survey technology and methodology.

BOEM conducts environmental reviews of the site assessment plan in accordance with various statutes. For example, NEPA requires federal agencies like BOEM to evaluate and report on the environmental impacts of a project such as an offshore wind project.[64] Agency subject matter experts, such as officials from NOAA Fisheries and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, consult on reviews of the plans for potential impacts from survey activities and proposed mitigations. In addition, BOEM requires, both through lease stipulations and as part of the approval process for site assessment and other plans, that offshore wind project developers take steps to mitigate potential adverse environmental impacts. For example, BOEM has directed lessees to establish “acoustic exclusion zones” for geophysical sound surveys, so that active survey areas are clear of marine mammals and sea turtles. BOEM may also require monitoring in conjunction with NOAA. Protected species observers, third party officials who report to both BOEM and NOAA, look for marine mammals so that the possibility of vessel strikes is minimized.

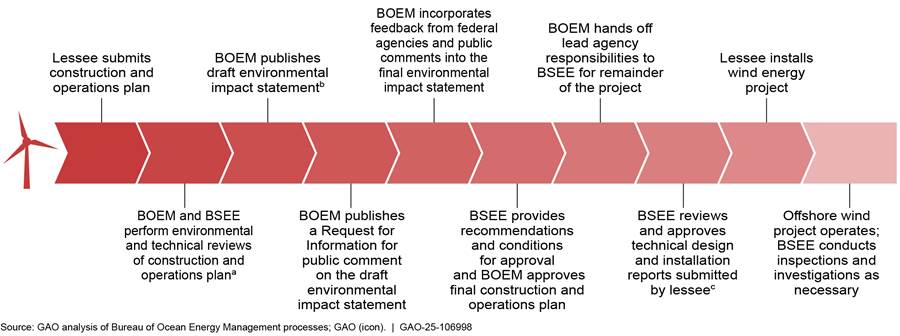

Construction and Operations. During the Construction and Operations phase, as shown in figure 6, BOEM and BSEE review a construction and operations plan (COP) submitted by the lessee. During this phase, BOEM and BSEE perform environmental and technical reviews.

Figure 6: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) Offshore Wind Energy Leasing Process—Construction and Operations Phase

aBOEM is the lead agency on environmental reviews, and BSEE leads some technical reviews. Technical reviews include data quality and site characterization analysis.

bBOEM and subject matter experts review, by law, the construction and operations plan (COP) to analyze environmental impacts from construction, operation, and decommission and the proposed mitigations.

cBSEE, along with BOEM, conducts a review of the fabrication design report and facility installation report to ensure consistency with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 requirements, consistency with the COP, and technical acceptability.

In accordance with NEPA, BOEM first publishes its environmental analysis in a draft EIS. Affected Tribes, stakeholders, and the public are invited to comment on the draft EIS. BOEM officials told us they incorporate this feedback as they deem appropriate into the final EIS.

BOEM officials told us the agency includes requirements in the COP approvals, such as revised communication and engagement plans. In addition, as part of the process for approvals of such plans, BOEM may direct lessees to implement mitigations during Construction and Operations. Table 3 includes examples of mitigations that BOEM may require of lessees, in coordination with other agencies.

|

Potential impact |

Mitigation |

|

Marine life and ecosystems |

|

|

Acoustic disturbance |

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) may require the lessee to · monitor operational noise and whale and fish vocalizations in the lease area before, during, and following construction; · submit a Marine Mammal and Sea Turtle Monitoring Plan for Pile Driving; · use bubble curtains to dampen pile driving sound; · pause operations if protected species are sighted; and · limit piledriving to months outside of likely whale migration. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Marine Fisheries Service released draft technical guidance on the effects of human-made sound on marine mammals that establishes noise thresholds such as for offshore survey and construction activities.a |

|

Vessel strike |

BOEM may require the lessee to submit a Vessel Strike Avoidance Plan and take several precautions to minimize strike risk to protected species, such as complying with speed restrictions and employing observers to monitor and report marine mammal activity. |

|

Entanglement risk |

BOEM may require that lessees monitor the risk of secondary entanglement from expected increases in fishing around fixed-bottom turbine foundations by annually surveying at least 10 of the turbines located closest to shore. |

|

Collision risk to birds and bats |

BOEM may require the lessee to install bird perching-deterrent devices on each turbine, where possible. Prior to or concurrent with offshore construction activities, BOEM may require the lessee to submit an Avian and Bat Post-Construction Monitoring Plan for BOEM, Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service review. |

|

Fishing industry |

In January 2025, BOEM finalized guidelines that provide recommendations to lessees on the mitigation of impacts to fishing, including compensation for losses to commercial and recreational fisheries.b |

|

Fishery surveys |

NOAA is coordinating with BOEM and lessees to deploy a northeast Atlantic regional survey mitigation strategy to address the potential impacts to its ability to conduct fisheries surveys within wind arrays.c |

|

Economic and community impacts |

BOEM has included bidding incentives for lessees to invest locally, which can include developing a local workforce. For example, one lessee was required, per the lease agreement, to provide approximately $20 million for local workforce training programs or developing a domestic supply chain (e.g., local assembly or manufacture of turbine components). |

|

Tribal resources |

Tribes may be invited to participate in task forces and therefore provide feedback to BOEM throughout the permitting process. Starting in 2022, with leases in the New York Bight and Carolina Long Bay, BOEM included stipulations that lessees develop a Native American Tribes Communications Plan. BOEM issued draft guidelines for these plans in February 2023 that include descriptions of the types of information and outreach lessees should conduct with Tribes. |

|

Defense and radar systems |

Early coordination between BOEM and the Department of Defense (DOD) has resulted in avoiding defense-critical areas. For example, in 2017, DOD provided a wind energy compatibility assessment in support of BOEM’s efforts to establish wind energy areas in the New York Bight. BOEM continued to work with DOD’s Military Aviation and Installation Assurance Siting Clearinghouse to deconflict existing and future activities identified by DOD, particularly the Department of the Navy training exercises. Prior to commencing construction, BOEM may require the lessee to establish a communications plan in coordination with the U.S. Fleet Forces Command and the Naval Air Warfare Center Aircraft Division concerning construction activities with the potential to impact military activities. Prior to operation, BOEM may require that the lessee notify various radar operators and users of radar data (e.g., NOAA, United States Coast Guard, and various DOD entities) to coordinate mitigation of adverse radar impacts. BOEM may also require that lessees submit documentation demonstrating how it will mitigate unacceptable interference with oceanographic high-frequency radar systems. |

|

Marine navigation and safety |

BOEM, in consultation with the Coast Guard, can prohibit construction within a certain distance of shipping lanes. In addition, BOEM may require lessees to provide a lighting, marking, and signaling plan for review by BOEM, BSEE, and the Coast Guard at least 120 days before installing turbine foundations. BOEM may also require lessees to coordinate on maritime safety and security issues, including notifying BSEE and the Coast Guard of any relevant events or incidents and providing the Coast Guard with environmental data, imagery, communications, and other information pertinent to search and rescue or marine pollution response. |

Source: GAO review of lease documents and expert testimony. | GAO‑25‑106998

aNational Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, 2024 Updated Guidance for Assessing the Effects of Anthropogenic Sound on Marine Mammal Hearing—Underwater and In-Air Criteria for Onset of Auditory Injury and Temporary Threshold Shifts (Washington D.C.: October 2024).

bBOEM, Guidelines for Providing Information for Mitigating Impacts to Commercial and For-Hire Recreational Fisheries on the Outer Continental Shelf Pursuant to 30 CFR Part 585 (Washington, D.C.: January 2025).

cNOAA officials told us they are currently developing regional strategies to mitigate impacts on surveys for the southern Atlantic and the area formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico, as well as for the Pacific coast.

Following BOEM’s approval of the COP, BOEM hands off lead agency duties to BSEE. During Construction and Operations, BSEE oversees the implementation and maintenance of safety management plans developed by the lessee. BSEE also monitors the lessee’s management and evaluation of structural integrity and critical safety systems to ensure that the facilities are responsibly maintained for the operational life of the lease. The agency may conduct scheduled and unscheduled inspections to determine whether the lessee is in compliance with laws, regulations, and the terms and conditions of the lease, among other things. BSEE may also conduct investigations if an incident (such as a fire), injury, or fatality occurs. The agency may also take enforcement action, such as issuing noncompliance notices, cessation orders, suspension of operations, and certain lease suspensions, if necessary.

|

Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) Blade Failure Investigation In July 2024, a blade failure on one turbine at the Vineyard Wind project—under construction about 15 miles off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts—caused one of three turbine blades to break off. Debris, consisting primarily of foam insulation and fiberglass pieces, washed up on local beaches. Local communities expressed concern about the potential impacts of the debris to the environment, marine life, and human health. BSEE sent a team to investigate the incident, according to officials. BSEE called for Vineyard Wind to cease power production and construction and conduct a risk analysis for personnel working in the area. One month following the failure, BSEE allowed Vineyard Wind to resume installation of turbine towers and nacelles and subsequently called for an analysis of the environmental harm caused by the blade failure. Vineyard Wind conducted debris removal following the blade failure, which the manufacturer attributed to a manufacturing flaw. As of January 2025, BSEE’s investigation is ongoing, and an after-investigation report should be publicly available within 1 year of the incident, according to BSEE officials. |

Source: GAO analysis of BSEE information. | GAO‑25‑106998

Decommissioning. During the Decommissioning phase, BSEE reviews and approves the decommissioning application. This should include, by law, a review of potential environmental impacts resulting from decommissioning activities. BSEE would, as necessary, conduct oversight and take enforcement action, as well as verify that the site has been cleared.

BOEM Has Taken Steps to Address Gaps in Its Tribal Engagement, but Concerns Remain About Meaningful Consultation and Capacity Building

During initial planning of wind energy areas and when establishing wind lease areas, BOEM has taken steps to incorporate tribal input but has not consistently engaged in meaningful consultation, according to Tribes. Furthermore, consultation between BOEM and Tribes on wind development has been limited by Tribes’ capacity issues and limitations in BOEM and BSEE’s statutory ability to provide adequate support for capacity building.

Inconsistent Tribal Consultation

BOEM has not consistently engaged in meaningful consultation with Tribes during the offshore wind energy development process as called for in directives and guidance for tribal consultation. Representatives from most of the Tribes and tribal organizations we spoke with stated they have given input to BOEM at various points in the process, but their input was not addressed. Moreover, BOEM has not consistently demonstrated whether and how it has incorporated tribal feedback into its decisions. For example, in earlier tribal consultation reports, BOEM detailed how it invited many Tribes to consult, but did not describe how, if at all, it incorporated comments from Tribes or what constituted formal and informal consultation, as required. Furthermore, according to one expert and nearly all the Tribes we spoke to, shortcomings in BOEM’s consultation efforts included challenges with the following.

· Timing of coordination. In some cases, tribal representatives told us that coordination occurred after BOEM had made decisions about where it established wind energy areas, too late for BOEM to incorporate input from Tribes. For example, one tribal official told us BOEM did not contact their Tribe until after the relevant lease was awarded. Representatives from many Tribes told us that BOEM is treating consultation as a “box-checking exercise,” and it was not clear how, if at all, their comments would affect the lease location or terms and conditions. In some cases, tribal representatives told us that BOEM’s outreach was limited to notifying Tribes via letter or email and presenting information at public meetings. BOEM officials told us that Tribes have not always had the opportunity to give feedback on wind energy area identification due to tight time frames.

· Incorporation of tribal feedback. Many tribal representatives told us that BOEM is not adequately incorporating feedback from consultations and outreach about culturally significant sites into its decisions. Specifically, some tribal representatives stated that, when identifying leasing areas, BOEM focused on physical artifacts assessed by archaeologists and technicians that may not be familiar with tribal traditions and oral history related to certain offshore areas. Moreover, some tribal representatives raised concerns that lessees were not qualified to take appropriate care when surveying submerged lands during Site Assessment. BOEM annual tribal consultation reports indicated they received tribal officials’ concerns, but BOEM project documentation does not consistently reflect whether the agency took efforts to consider or address these concerns.[65]

· Recognition of impacts to fishing areas, including some areas protected by treaty. Several tribal representatives told us that BOEM has not adequately addressed their concerns about impacts to their established fishing areas, some of which are protected by treaties and require co-management by the Tribes and federal government. Representatives from one Tribe warned of the possibility of their territorial fishing grounds becoming overcrowded, as boats that have been excluded from lease areas with floating wind turbines could move into their fishing grounds. Others said they raised concerns to BOEM but have seen no response or efforts to use tribal expertise through co-management of fishing grounds.[66]

Multiple sources of guidance and directives exist to guide BOEM’s consultation with Tribes (see table 4).

|

Source of guidance or directives |

Key language |

|

Executive Order 13175a |

Each agency shall have an accountable process to ensure meaningful and timely input by tribal officials in the development of regulatory policies that have tribal implications. |

|

Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966b |

Federal agencies must consult with designated representatives of Indian Tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations when agency-assisted “undertakings” may affect historic properties—including those to which Tribes attach religious or cultural significance—prior to the approval of the expenditure of federal funds or issuance of any licenses.c |

|

Guidance for Federal Departments and Agencies on Indigenous Knowledge, Executive Office of the Presidentd |

Indigenous knowledge is a valid form of evidence for inclusion in federal policy, research, and decision making. |

|

Joint Interior and USDA Secretarial Order on Fulfilling the Trust Responsibility to Indian Tribes in the Stewardship of Federal Lands and Waters (Order 3403)e |

The departments will consider tribal expertise or Indigenous knowledge as part of federal decision-making relating to federal lands, particularly concerning management of resources subject to reserved tribal treaty rights and subsistence uses. The departments will endeavor to engage in co-stewardship where federal lands or waters, including wildlife and its habitat, are located within or adjacent to a federally recognized Indian Tribe’s reservation, where federally recognized Indian Tribes have subsistence or other rights or interests in non-adjacent federal lands or waters, or where requested by a federally recognized Indian Tribe. |

|

Interior Departmental Manual: Intergovernmental Relations, Part 512f |