IDENTITY VERIFICATION:

GSA Should Demonstrate Its Implementation of Policies for Testing Data Backups on Login.gov

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Marisol Cruz Cain at cruzcainm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107000, a report to congressional requesters

GSA Should Demonstrate Its Implementation of Policies for Testing Data Backups on Login.gov

Why GAO Did This Study

The risk of identity theft and fraud has been increasing, and data breaches at federal agencies and in the private sector have resulted in the compromise of millions of Americans’ personally identifiable information. The sensitive information obtained in those breaches could be used by malicious actors to commit identity fraud.

GAO was asked to examine how Login.gov compares to commercial solutions. This report, among other things: (1) compares Login.gov’s capabilities to selected commercially available solutions; (2) identifies reported agency spending on Login.gov and commercial solutions; and (3) evaluates the extent to which Login.gov and other selected solutions protect the sensitive data they collect and manage.

GAO reviewed the commercial solutions’ capabilities and compared them with Login.gov. GAO compared how much agencies spent on commercial solutions and Login.gov. GAO also analyzed and compared Login.gov and commercial vendors’ privacy practices with industry best practices.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making one recommendation to GSA to ensure that Login.gov demonstrates that it fully implemented the policy to test its data backups. GSA concurred with the recommendation.

What GAO Found

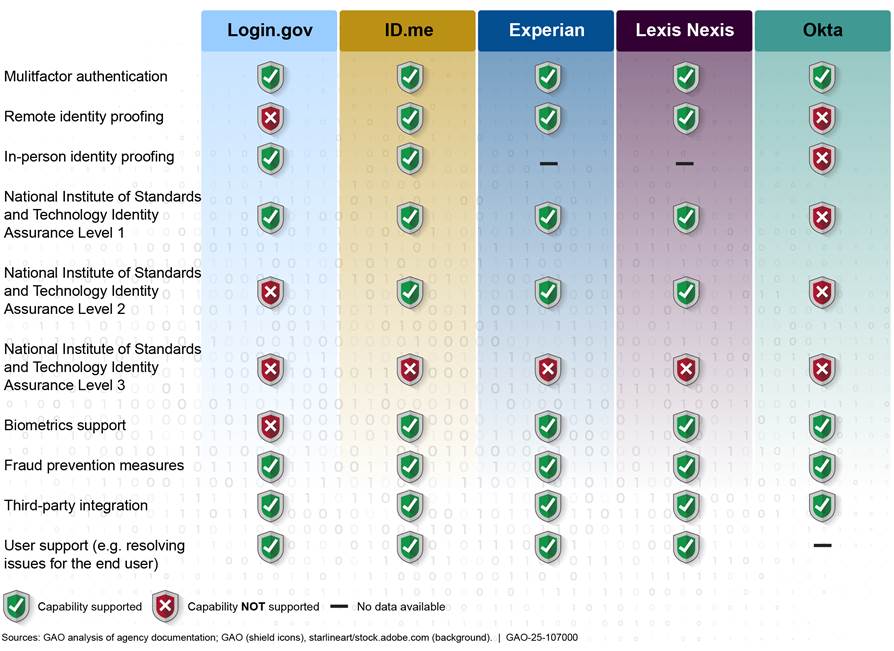

In 2017, the General Services Administration (GSA) launched Login.gov, which offers various capabilities. These include multi-factor authentication, identity-verification services, and fraud prevention measures. Authentication verifies the identity of a user, process, or device before allowing access to IT systems. Identity proofing verifies whether individuals are who they claim to be. However, from fiscal years 2020 to 2023, Login.gov offered fewer capabilities compared to commercial solutions (e.g. biometrics). For example, Login.gov did not provide identity proofing services in alignment with the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s standards until October 2024.

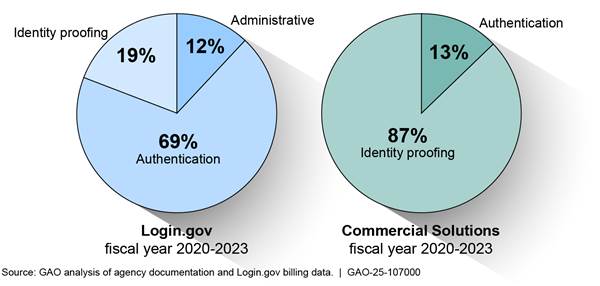

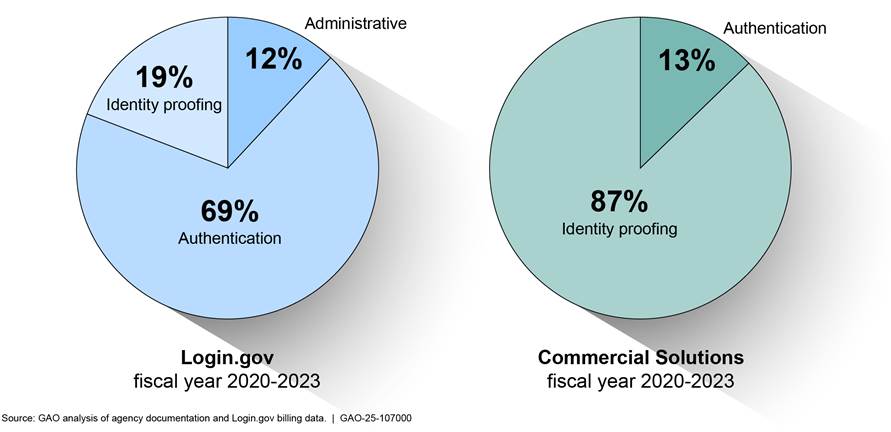

Between fiscal years 2020 and 2023, federal agencies reported spending approximately $209 million on commercial solutions while spending $32.5 million on Login.gov.

Agencies’ Login.gov and Commercial Solution Spending

for Fiscal Years 2020 to 2023

Note: For proprietary reasons, private vendors did not share detailed pricing information on their commercial solutions. As a result, we were not able to make a direct comparison.

Login.gov and selected commercial solutions largely implemented data protection categories in the “protect” function suggested by National Institute of Standards and Technology. Although Login.gov fully implemented four of five privacy practices, it did not fully implement policies and procedures for testing the integrity of its backup data.

According to GSA, the control was not fully implemented because Login.gov’s security engineering team was not fully staffed until January 2024. At the conclusion of GAO’s review, GSA reported that it had established a data protection policy; however, it has not yet demonstrated that the intended results of implementing this policy are being achieved.

Abbreviations

AAL authenticator assurance level

AAL1 authenticator assurance level 1

AAL2 authenticator assurance level 2

AAL3 authenticator assurance level 3

CFO Act Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990

FedRAMP Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program

FISMA Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014

GSA General Services Administration

IAL identity assurance level

IAL1 identity assurance level 1

IAL2 identity assurance level 2

IAL3 identity assurance level 3

IT information technology

NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology

OMB Office of Management and Budget

PII personally identifiable information

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 3, 2025

The Honorable Pete Sessions

Chairman

The Honorable Kweisi Mfume

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Government Operations

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

House of Representatives

The risk of identity theft and fraud has been increasing, and data breaches at federal agencies as well as in the private sector have resulted in the potential compromise of millions of Americans’ personally identifiable information (PII).[1] The sensitive information obtained in those breaches could be used by malicious actors to commit identity fraud for financial or other gain. For example, according to the Federal Trade Commission, there were more than 1 million reports of identity theft and fraud each year in 2022 and 2023. This included fraudulently receiving government benefits, tax fraud, wage-related fraud, and creating new credit card accounts, among other things.

To reduce the threat of identity fraud, the General Services Administration’s (GSA) Technology Transformation Services division launched Login.gov in 2017.[2] The system was intended to provide federal agencies with a single sign-on platform to verify the identity of individuals seeking access to government websites. Login.gov uses a three-step process—the identity proofing process—that results in the verification of an individual’s identity. The process includes (1) the individual providing identifying information (e.g., name, address, date of birth, etc.); (2) the government agency validating whether the submitted information is genuine, often through a third-party organization; and (3) the agency verifying whether the individual is who they claim to be by matching the submitted information with other evidence, such as comparing a photo ID with the individual’s face. In 2021, GSA allocated about $187 million in technology modernization funds to increase Login.gov’s services, including strengthening its security and anti-fraud protections and improving ease of agency adoption.

However, Login.gov did not provide identity proofing services in alignment with the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) Digital Identity Guidelines until October 2024.[3] Prior to that time, Login.gov’s services did not include remotely verifying the user’s physical or biometric attributes. Verification, whether it is done in-person or remotely, is one of the requirements by NIST for higher assurance that the individual is who they claim to be. Due in part to the lack of this important functionality, several of the 24 Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act) agencies reported the need to use commercially available identity proofing solutions in addition to, or instead of, Login.gov.[4] For example, the Internal Revenue Service under the Department of the Treasury uses a third-party commercial identity proofing service called ID.me to verify the identity of users that are accessing their tax returns.

You asked us to examine how Login.gov compares to commercial solutions and how each solution protects sensitive data. This report (1) reviews Login.gov’s capabilities and pricing structure; (2) compares Login.gov’s capabilities to selected commercially available solutions; (3) identifies reported agency spending on Login.gov and commercial solutions; and (4) evaluates the extent to which Login.gov and other selected solutions protect the sensitive data they collect and manage.

To address our first objective, we reviewed documents that detailed Login.gov’s technical capabilities and its billing information. From these documents, we identified technical capabilities in the areas of authentication, identity proofing, technical features (i.e., biometrics[5], fraud prevention, and third-party vendor integration[6]), and support services. In addition to the technical capabilities, we requested and reviewed Login.gov’s pricing and billing information from fiscal years 2020 to 2023. We also interviewed Login.gov officials to gain a better understanding of the system’s technical capabilities and pricing models.

For our second objective, we relied on prior GAO work to identify what commercial solutions the 24 CFO Act agencies use for identity proofing.[7] We then analyzed information that detailed the technical capabilities of each of the solutions, such as documents that the vendors submitted as part of the contract solicitation process.[8] From these documents, we identified the solutions’ technical capabilities in the areas of authentication, identity proofing, technical features, and support services.[9] We interviewed the commercial solution vendors that the CFO Act agencies reported using regarding their technical capabilities.[10] Lastly, we compared the commercial solutions’ technical capabilities with those of Login.gov. The scope of our review was limited to fiscal years 2020 to 2023.

To address our third objective, we analyzed vendor billing and agency spending data reported by the agencies associated with the use of identity proofing solutions from fiscal years 2020 to 2023.[11] We interviewed the commercial solution vendors regarding their pricing models.[12] In addition, we compared the agencies’ spending information for commercial solutions with those of Login.gov.

For our fourth objective, we analyzed NIST’s Privacy Framework: A Tool for Improving Privacy through Enterprise Risk Management (Privacy Framework).[13] From this guidance, we identified the key practices for the “protect” function, which detail ways to protect sensitive data and prevent cybersecurity-related privacy incidents. We then requested information from Login.gov, Experian, ID.me, LexisNexis, and Okta regarding how the solutions protect PII. However, none of the commercial solution vendors provided the information, citing business sensitivity concerns. To address this, we requested the solutions’ Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) packages from GSA.[14] Through this process, we were able to obtain the privacy-related documents for ID.me and Okta, which the solutions had submitted to GSA to be FedRAMP certified. According to GSA, Experian and LexisNexis are not cloud service providers authorized under FedRAMP. As a result, we were unable to obtain any privacy-related documents for Experian and LexisNexis to conduct this analysis.

Next, we compared Login.gov and the two commercial solutions’ data protection policies and procedures and third-party assessment results to these key practices to determine if there were any gaps. We then interviewed Login.gov officials and the commercial solution vendors to corroborate and obtain additional information on their practices for protecting sensitive data. For more details on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

To ensure that users attempting to access government services, benefits, and other resources are who they claim to be, federal agencies are responsible for properly identifying and verifying the applicants’ identities. Identity proofing is the process that federal agencies and other entities use to verify that individuals are who they claim to be. This process to either remotely or physically verify identifying documents and evidence may include a combination of government and commercial data sources containing sensitive information and in-person interactions.[15]

Identity proofing may occur in-person or through a remote online process. In the case of in-person identity proofing, a trained professional verifies an individual’s identity by making a direct physical comparison of the individual’s physical features and other evidence (such as a driver’s license) with official records to verify the individual’s identity. Validating these credentials can be performed by checking electronic records in tandem with physical inspection.

Remote identity proofing is the process of conducting identity proofing entirely through an online exchange of information. When this method is used, the individual provides the information electronically or performs other electronically verifiable actions that demonstrate their identity (e.g., selfies, verification through a virtual meeting, etc.). Once the individual provides the required information electronically, a credential service provider verifies the information before issuing credentials to that person.

Once a user’s identity is verified and their credentials are issued, the user then can access government services, benefits, and other resources through the authentication process. According to NIST, authentication is the process of verifying the identity of a user, process, or device before allowing access to IT systems.[16] For example, multi-factor authentication requires a user to verify their identity by providing more than just a username and password, such as a code sent to their cellular device.

Federal Legislation and Guidance on Data Protection and Identity Proofing

Federal laws and guidance specify requirements for federal agencies to protect systems and data, including systems used or operated by a contractor or other organization on behalf of a federal agency.

· The Privacy Act of 1974 establishes agency responsibilities and protections for personal information accessed or held by federal agencies. For example, the Privacy Act places limitations on the collection, disclosure, dissemination, and use of personal information maintained in “systems of records,” or groups of records under the control of any agency from which information is retrieved by individual name or identifier.[17]

· The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-130 establishes general policy for the planning, budgeting, governance, acquisition, and management of federal information, personnel, equipment, funds, IT resources, and supporting infrastructure and services.[18] The appendices to this circular include responsibilities for protecting federal information resources and managing PII. For example, the circular requires agencies to ensure that terms and conditions in contracts and other agreements incorporate privacy requirements for the protection of federal information and to maintain an inventory of systems that create, collect, use, process, store, maintain, disseminate, disclose, or dispose of PII.

· OMB published a zero-trust strategy that requires agencies to adopt specific cybersecurity standards and objectives that are intended to form a starting point to implementing zero trust architecture.[19] The strategy’s requirements include integrating and enforcing multifactor authentication across applications involving authenticated access to systems by agency, staff, and partners.

· NIST’s privacy framework provides guidance to agencies on the selection and implementation of information security and privacy controls for systems.[20] Within the framework, functions organize foundational privacy activities at their highest level. The framework’s “protect” function outlines the development and implementation of appropriate data processing safeguards (see table 1).

Table 1: National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) Privacy Framework “Protect” Function and its Categories

|

Function |

Category |

|

Protect: Develop and implement appropriate data processing safeguards. |

Data protection policies, processes, and procedures: Security and privacy policies (e.g., purpose, scope, roles and responsibilities in the data processing ecosystem and management commitment), processes, and procedures are maintained and used to manage the protection of data. |

|

Identity management, authentication, and access control: Access to data and devices is limited to authorized individuals, processes, and devices, and is managed consistent with the assessed risk of unauthorized access. |

|

|

Data security: Data are managed consistent with the organization’s risk strategy to protect individuals’ privacy and maintain data confidentiality, integrity, and availability. |

|

|

Maintenance: System maintenance and repairs are performed consistent with policies, processes, and procedures. |

|

|

Protective technology: Technical security solutions are managed to ensure the security and resilience of systems/products/services and associated data, consistent with related policies, processes, procedures, and agreements. |

Source: GAO analysis of NIST’s Privacy Framework. | GAO‑25‑107000

In addition to laws and guidance focusing specifically on PII, agencies are subject to laws and guidance governing the protection of information and information systems. For example, the Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (FISMA) is intended to provide a comprehensive framework for ensuring the effectiveness of information security controls over information resources that support federal operations and assets, as well as the effective oversight of information security risks. FISMA requires each agency to develop, document, and implement an agency-wide information security program to provide risk-based protections for the information and information systems that support the operations and assets of the agency, including those provided or managed by another entity.

FISMA also assigns government-wide responsibilities to key agencies. For example, NIST is responsible for developing comprehensive information security standards and guidelines for federal agencies. The act also requires agencies to comply with these federal information standards and guidelines.

To fulfill its FISMA responsibilities, NIST issues technical guidelines on many different aspects of information security, including, in 2017, on authentication and identity proofing. Specifically, NIST issued guidelines that outline how to authenticate a user’s claimed identity.[21] The guidelines, among other things, define authenticator assurance levels (AAL) and methods. Specifically, AALs describe the degree of strength of authenticators (i.e. the stronger the authentication, the higher the AAL). Further, authentication methods such as passwords, tokens, and fingerprint scanning are assigned one of three AALs depending on the authentication requirements for federal systems (see table 2).

Table 2: Summary of the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) Authenticator Assurance Levels (AAL)

|

AAL Level |

Description |

Requirement |

|

AAL1 |

AAL1 provides some assurance that the claimant controls an authenticator used for the subscriber’s account. |

AAL1 requires either single-factor or multi-factor authentication. Factors could include memorized secrets (e.g. password) and physical authenticators (e.g. one-time password devices). |

|

AAL2 |

AAL2 provides high confidence that the claimant controls authenticator(s) used for the subscriber’s account. |

AAL2 requires two different authentication factors, either (1) a physical authenticator and a memorized secret, or (2) a physical authenticator and a biometric that is associated with it (e.g. fingerprint scanner). |

|

AAL3 |

AAL3 provides very high confidence that the claimant controls authenticator(s) used for the subscriber’s account. |

AAL3 requires a hardware-based authenticatora and an authenticator that provides verifier impersonationb resistance. Hardware-based authenticators are typically public key infrastructure-basedc tokens, such as Personal Identity Verification cards. |

Source: GAO summary of National Institute of Standards and Technology Information. | GAO‑25‑107000

aA hardware-based authenticator is a physical device (e.g. a USB key) used to verify a user’s identity by providing a unique code when plugged into a computer.

bAccording to NIST, verifier impersonation is where an attacker impersonates an entity that confirms the user’s identity, typically to capture information that can be used to gain access to the real verifier.

cAccording to NIST, a public key infrastructure is a framework that is established to issue, maintain, and revoke public cryptographic keys that are used to encrypt messages intended for a particular recipient.

NIST also issued guidelines in 2017 on identity proofing that outline technical requirements for resolving, validating, and verifying an identity based on evidence obtained from a remote applicant. This guidance defines identity assurance levels (IAL), which describe the degree of confidence that a user’s claimed identity is their real identity (see table 3). In addition, the guidance requires applications be assigned one of three IALs based on the sensitivity of information it holds, such as Social Security numbers, and the potential harm caused if an attacker makes a successful false claim of an identity to gain system access.

Table 3: Summary of the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Identity Assurance Levels (IAL)

|

IAL level |

Description |

Verification method |

|

IAL1 |

There is no requirement to link users to a specific real-life identity. Any information provided by users should be treated as self-asserted and is neither validated nor verified. |

No identity evidence is collected. |

|

IAL2 |

The evidence provided supports the real-world existence of users’ identities and verifies that users are appropriately associated with this real-world identity. This level introduces the need for either remote or physically present identity proofing. |

Evidence may include a passport or driver’s license, and supporting remote biometrics, such as a “selfie.”a |

|

IAL3 |

Physical presence is required for identity proofing. Identifying attributes must be verified by an authorized and trained credential service provider representative. |

Evidence may include a passport and driver’s license, as well as a physical or remote interaction supervised by a live operator. |

Source: GAO analysis of National Institute of Standards and Technology Information. | GAO‑25‑107000

aA “selfie” is a photograph one takes of oneself.

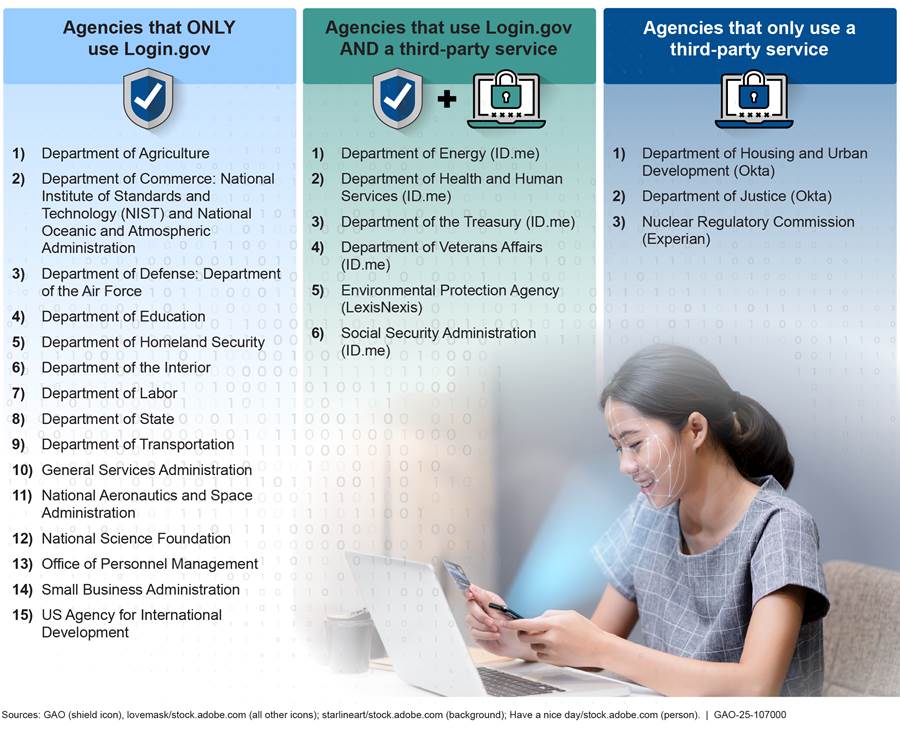

Federal Agencies Use a Variety of Solutions to Conduct Identity Proofing

Of the 24 CFO Act agencies, 15 reported using Login.gov for public-facing applications, six reported using Login.gov in conjunction with a commercial solution, and three reported not using Login.gov, opting instead to use a commercial solution (see figure 1). The commercial solutions that were used by the agencies were Experian, ID.me, LexisNexis, and Okta.[22]

Figure 1: Agencies’ Reported Use of Login.gov and Other Solutions for Public-Facing Applications as of October 2024

Notes: The names of any third-party services used are

provided in parentheses after the agency name. The third-party provider may

offer authentication only or identity proofing services.

According to Department of Justice officials, the agency does not use any

identity proofing solutions to conduct authentication or identity proofing for

public facing applications.

According to National Aeronautics and Space Administration officials, Login.gov is used for one public facing application.

According to Department of Defense officials, U.S. Air Force is the only component that uses Login.gov at the Department of Defense. Also, according to Department of Commerce officials, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Institute of Standards and Technology are the only components at the Department of Commerce that uses Login.gov.

According to data reported by the CFO Act agencies, more users utilized Login.gov’s services compared to the commercial identity proofing solutions. For example, about 190 million users utilized Login.gov compared to approximately 60 million users that utilized the four commercial solutions combined from fiscal years 2020 to 2023. In particular, the agencies that provide wide-reaching services for most of the general public (e.g., health insurance, Social Security, etc.) reported the greatest number of users of Login.gov. For example:

· The Social Security Administration uses Login.gov for multiple applications, including its MySocialSecurity portal, which allows users to access the Social Security system and perform actions such as reviewing direct deposit information and reporting wages. Approximately 42 million users reportedly used Login.gov for these services.

· The Department of Homeland Security uses Login.gov for Customs and Border Protection programs, which allows users to log in and access transportation security services such as TSA PreCheck® and Global Entry.[23] Approximately 25 million users reportedly used Login.gov for these services.

The nine agencies that reported using a commercial solution in addition to, or in place of, Login.gov did so for two main reasons. Specifically, six agencies and departments required solutions that provided transactions at the NIST IAL2 level of assurance (i.e., ID.me or LexisNexis) that Login.gov had not yet provided.[24] For example, the Internal Revenue Service requires IAL2 compliant solutions to authenticate taxpayers before granting them access to applications that collect and use sensitive data (e.g., tax account information, biometric identifiers, passport numbers, etc.). In addition, seven agencies reported that commercial solutions were more cost-effective. For example, the agencies reported that Login.gov’s services were more expensive compared to commercial alternatives. Further, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission reported using Experian because the agency performs identity proofing only about 200 times a year and this option was deemed cost effective for the agency.

GAO Previously Made Recommendations Regarding Login.gov

In October 2024, we reported that GSA had taken steps to align Login.gov with NIST digital identity guidelines, including (1) completing a pilot on in-person identity proofing in March 2024 and (2) beginning a separate pilot on remote identity proofing.[25] However, GSA had not ensured that Login.gov fully aligns with federal guidelines for identity verification. Specifically, the remote identity proofing pilot was not yet available because GSA has not established an expected completion date for the pilot. Accordingly, we made three recommendations to GSA, which included (1) addressing Login.gov’s technical challenges that its customer agencies identified within agreed-upon time frames, (2) establishing a completion date for the remote identity proofing pilot program, and (3) ensuring that Login.gov develops and documents a plan for lessons learned for Login,gov’s remote identity proofing pilot program. As of March 2025, GAO closed the recommendation that Login.gov had completed its remote identity-proofing pilot and began offering this service to all users as implemented. However, the agency has yet to fully address Login.gov’s technical challenges and has not yet developed and documented a plan for lessons learned.

Login.gov Offered Various Capabilities and Two Pricing Structures

During fiscal years 2020 to 2023, Login.gov provided various capabilities to its partner agencies, including multi-factor authentication, identity proofing services, and fraud prevention measures.[26] In addition, Login.gov established two pricing models—enterprise and transactional—that its customer agencies could select, depending on which model may have been the most cost-effective for their needs.

Login.gov Provided a Variety of Capabilities

During fiscal years 2020 to 2023, Login.gov offered a variety of capabilities based on the customer agencies’ identity proofing and authentication needs. For example, Login.gov offered:

· Multifactor authentication. Login.gov asked users for an email address and password to access their Login.gov account. In addition, the system required additional information, such as a security key or an authentication application to validate the user’s identity. According to NIST, the use of at least two different authentication factors provides a high assurance that the user should have access to a system and/or asset.

|

According to the National Institute of Standards and

Technology, the following evidence are required at each identity assurance

level (IAL): · IAL1: There is no requirement to link users to a specific real-life identity. Any information provided by users should be treated as self-asserted and is neither validated nor verified.

· IAL2: The evidence provided supports the real-world existence of users’ identities and verifies that users are appropriately associated with this real-world identity. This level introduces the need for either remote or physically present identity proofing.

· IAL3: Physical presence is required for identity proofing. Identifying attributes must be verified by an authorized and trained credential service provider. Source: GAO summary of National Institute of Standards and Technology information. | GAO‑25‑107000 |

· NIST IAL 1 capabilities. Login.gov allowed the user to self-assert their personal information (e.g., first and last names, date of birth, etc.) to create their Login.gov account. According to NIST, there is no requirement to verify the identity of the user under the IAL 1 level.

· NIST IAL 2 Capabilities. Login.gov offered the user the ability to upload an image of the front and back of their unexpired state-issued identification (ID) card. The system then verified the users’ PII through a series of checks (e.g., checking for tampered IDs, ensuring that driver’s license data matches the issuing state’s records, etc.). However, Login.gov did not fully offer IAL 2 capabilities since it lacked remote verification. According to NIST, this capability provides assurance that the claimed identity exists.

· In-person identity proofing. Login.gov offered users the option to have identity proofing done in-person at a U.S. Post Office. If the user selected this option, they received a barcode after entering identifying information from their state-issued ID card, such as name, address, and ID number. Once the user presented the barcode at a U.S. Post Office for verification, the clerk completed the identity proofing process by verifying the full name and address on the state-issued ID and comparing the photo on the ID to the person present. According to NIST, in-person identity proofing provides assurance that the user is who they are claiming to be.

· Fraud prevention measures. Login.gov used fraud detection and mitigation tools to monitor and prevent fraud. For example, these tools monitored users through behavioral biometrics during the identity proofing process to determine if a fraudulent participant was involved during this process.[27]

· Third-party integration. Login.gov integrated with various LexisNexis solutions to conduct identity proofing. In addition, Login.gov integrated with the Driver’s License Data Verification Service offered by the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, which was to verify that the submitted PII from the user’s driver’s license matched the data from the user’s state.

· User support. Login.gov provided contact center services, which answered inquiries through email and phone support. For example, users could access Login.gov’s contact website to report any issues with their account (e.g., password reset, account lockout, errors during account creation, etc.) by submitting a ticket. In addition, Login.gov published a service number, which operated 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

More recently, in October 2024, Login.gov was deemed IAL2 compliant by a third-party assessor due to the addition of biometrics support capabilities that allowed it to offer remote identity proofing.[28] Specifically, Login.gov gained the ability to perform remote identity proofing by confirming that a live “selfie” taken by a user matched the photo on an ID, such as a driver’s license, provided by the user. As previously mentioned, IAL2 provides a higher assurance that a user is who they are claiming to be by requiring evidence that supports the claimed identity (e.g. biometrics).

Login.gov Established Two Pricing Models

Login.gov has established two pricing models since its launch, which determined how much federal agencies were to be charged for Login.gov’s services. Prior to fiscal year 2021, Login.gov charged its customers solely based on the total number of users that used the system. In and after fiscal year 2021, Login.gov offered enterprise and transactional pricing models, which allowed its customer agencies to select the most cost-effective model for their needs. For example, it might have been cost effective for a large customer agency with a significant number of users to select the enterprise pricing model, which charged based on tiers of the number of monthly active users. Conversely, it might have been cost-effective for an agency with a small number of users to select the transactional pricing model, which charged a fee for every transaction (e.g., authentication or identity proofing).

Login.gov Pricing Structure Prior to Fiscal Year 2021

Prior to fiscal year 2021, Login.gov adopted a pricing structure that was solely based on the total number of users that used the Login.gov system at each customer agency (see table 4). Login.gov determined the total number of users by counting each user that used the Login.gov system. For example, if the same user accessed Login.gov at multiple agencies, the user would count as one for each agency.

|

User Volume Range |

Yearly Price |

Price per User |

|

|

0 |

100,000 |

$30,000 |

$0.30 |

|

100,001 |

250,000 |

$72,000 |

$0.29 |

|

250,001 |

500,000 |

$138,000 |

$0.28 |

|

500,001 |

1,000,000 |

$264,000 |

$0.26 |

|

1,000,001 |

2,000,000 |

$506,250 |

$0.25 |

|

2,000,001 |

3,000,000 |

$735,000 |

$0.25 |

|

3,000,001 |

4,000,000 |

$945,000 |

$0.24 |

|

4,000,001 |

5,000,000 |

$1,138,500 |

$0.23 |

|

5,000,001 |

6,000,000 |

$1,311,000 |

$0.22 |

|

6,000,001 |

7,000,000 |

$1,476,000 |

$0.21 |

|

7,000,001 |

8,000,000 |

$1,612,500 |

$0.20 |

|

8,000,001 |

9,000,000 |

$1,755,000 |

$0.20 |

|

9,000,001 |

10,000,000 |

$1,883,250 |

$0.19 |

|

10,000,001 |

12,500,000 |

$2,310,000 |

$0.18 |

|

12,500,001 |

15,000,000 |

$2,610,000 |

$0.17 |

|

15,000,001 |

17,500,000 |

$2,925,000 |

$0.17 |

|

17,500,001 |

20,000,000 |

$3,022,500 |

$0.15 |

|

20,000,001 |

22,500,000 |

$3,120,000 |

$0.14 |

|

22,500,001 |

25,000,000 |

$3,217,500 |

$0.13 |

|

25,000,001 |

27,500,000 |

$3,315,000 |

$0.12 |

|

27,500,001 |

30,000,000 |

$3,412,500 |

$0.11 |

Source: Login.gov documentation. | GAO‑25‑107000

Login.gov Pricing Structure Between Fiscal Years 2021 - 2024

Login.gov established a pricing structure—that included enterprise and transactional pricing models—that customer agencies could select based on their needs. These needs may have included providing high numbers of transactions for services to the general public (e.g., taxes, health insurance, Social Security, etc.). Alternatively, agencies could select a pricing model that was more cost-effective for low numbers of transactions for services to the public.

· Enterprise Pricing Model. Login.gov’s enterprise pricing model charged a fee based on the agencies’ level of monthly active users.[29] See table 5 for a breakdown of the cost model.

|

Monthly Active User Tier |

Monthly Price |

|

0 – 124,999 |

$5,000 |

|

125,000 – 249,999 |

$10,000 |

|

250,000 – 499,999 |

$19,000 |

|

500,000 – 999,999 |

$37,000 |

|

1,000,000 – 1,999,999 |

$109,000 |

|

2,000,000 – 2,999,999 |

$216,000 |

|

3,000,000 – 3,999,999 |

$358,000 |

|

4,000,000 – 4,999,999 |

$534,000 |

|

5,000,000 – 5,999,999 |

$745,000 |

|

6,000,000 – 6,999,999 |

$991,000 |

|

7,000,000 – 7,999,999 |

$1,271,000 |

|

8,000,000 – 8,999,999 |

$1,586,000 |

|

9,000,000 – 9,999,999 |

$1,936,000 |

|

10,000,000 – 10,999,999 |

$2,321,000 |

Source: Login.gov documentation. | GAO‑25‑107000

· Transactional Pricing Model. The transactional pricing model charged a fee for every transaction (e.g., authentication or identity proofing). See table 6 for Login.gov’s services and prices.

|

Service |

Fee |

Price |

Description |

|

Authentication only |

Authentication fee |

$0.075 per successful authentication |

An authentication transaction is defined as a successful log-in attempt by a user. Every authentication is counted for usage calculations. |

|

Authentication platform fee |

$35,000 per year |

A platform fee includes basic operational and technical support. Operational support includes managing business operations and reporting (e.g., number of users and authentication, monthly charges, etc.). Technical support includes support specific to application integration. |

|

|

Authentication and identity proofing |

Active identity verified user |

$5 per user |

A user is considered “active” if they successfully log in with multifactor authentication. A verified user is one who has successfully completed the identity proofing process. |

|

Authentication fee |

$0.075 per successful authentication |

An authentication transaction is defined as a successful log-in attempt by a user. Every authentication is counted for usage calculations. |

|

|

Identity proofing platform fee |

$50,000 per year |

A platform fee includes basic operational and technical support. Operational support includes managing business operations and reporting. Technical support includes support specific to application integration. |

|

|

Consulting services |

Consulting fee |

$275 per hour |

A consulting fee covers consultation beyond the included 10 hours of onboarding support. This includes user support for the customer agencies’ users through its contact center, which primarily answers inquiries through email and will escalate to phone support as needed. |

|

Technical services |

Additional fee |

$275 per hour |

An additional fee for technical support, which costs $275 per hour, includes services, such as integrating other applications with Login.gov, and must be agreed upon and specified in an interagency agreement. |

Source: GAO analysis of Login.gov documentation. | GAO‑25‑107000

Note: Authentication is the process of verifying the identity of a user, process, or device before allowing access to IT systems. Identity proofing is a process to verify whether the user is really who they claim to be.

More recently, in July 2024, Login.gov established a new pricing structure affecting both the enterprise and transactional cost models (see appendix III). Specifically, agencies are to be charged a fee based on the level of monthly active users for Login.gov’s authentication services. According to GSA, customer agencies may see price reductions, as much as 70 percent for identity proofing services and 20 percent for authentication services with this new pricing structure. However, GSA officials noted that the amount may vary depending on the customers’ usage.

Most Commercial Solutions Offered More Capabilities than Login.gov

During fiscal years 2020 to 2023, contractual documentation showed that commercial identity proofing solutions offered more capabilities than Login.gov. Most notably, commercial solutions offered the ability to verify that people are who they claim to be at a higher assurance level, as well as the ability to perform remote proofing. For example, ID.me, Experian, and LexisNexis offered remote identity proofing and IAL2 capabilities, while Login.gov did not.[30] See figure 2 for the capabilities that each solution offered during the period of our review.[31]

Note: On October 9, 2024, GSA published a press release announcing certification of IAL2 compliance for both remote and in-person identity verification offerings. We confirmed this information with GSA and the third-party certifier

The capabilities identified in this report do not constitute an exhaustive list of what is offered by Login.gov and commercial solutions. The specific offerings for each of the capabilities may vary.

For the fiscal years 2020 to 2023 period, most of the commercial solutions reviewed offered more capabilities than Login.gov. Specifically:

· Multifactor authentication. As previously mentioned, multifactor authentication requires more than one factor to verify a user’s identity. Specifically, these would include something you know (e.g. password/personal identification number); something you have (e.g., cryptographic identification device, or token); or something you are (e.g. biometric).[32] Using at least two different authentication factors provides a high assurance that the user should have access to a system or asset. All five vendors offered multifactor authentication, which included factors such as a security key, a code generator application, and codes sent by text message or phone call to verify a user’s identity.

|

According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the identify-proofing process involves three steps:

· Resolution: This step starts the identity resolution process by having users provide identifying information, such as driver’s license information, typically through a web-based application form.

· Validation: The authenticity and accuracy of users’ personally identifiable information is compared to an authoritative source such as a motor vehicle database.

· Verification: Users take a “selfie” of themselves to match the license picture provided in the resolution step. Source: GAO summary of NIST information. | GAO‑25‑107000 |

· Remote identity proofing. Remote identity proofing by a credential service provider verifying a user’s information and physical attributes face-to-face (e.g., through a video call) can provide assurance that the user is who they are claiming to be. Users can complete the proofing process (i.e. resolution, validation, and verification) by using their own hardware and without physically meeting in person with a credential service provider. ID.me, Experian, and LexisNexis offered this capability while Login.gov did not during the period of our review. For example, ID.me offered a video call-based service, where an individual would virtually meet with an employee who remotely verified that the user’s claimed identity was legitimate by reviewing the submitted documents and interviewing the user.

· In-person identity proofing. As previously mentioned, in-person identity proofing can provide assurance that the user is who they claim to be by having a credential service provider verify a user’s information and physical attributes in-person. This capability is intended to allow users to complete the identity proofing process at a physical location with a credential service provider. Login.gov and ID.me offered this capability. For example, ID.me offered users the ability to verify their identities physically with a technician. Users could walk into or make an appointment at a retail location to which they would bring two to three required documents (e.g., state-issued driver’s license, U.S. passport, etc.). Once at the retail location, a technician would verify that the documents were valid and that the documents belonged to the user. The user would also take a selfie and submit photos of the documents, after which a document reviewer would validate them.

· NIST IAL1 capabilities. As previously discussed, IAL1 does not include any requirements to verify the identity of a user. Login.gov, ID.me, Experian, and LexisNexis offered services that allowed users to self-assert their identities. For example, LexisNexis processed self-asserted user input (e.g., first and last names, date of birth, home address, social security number, etc.) to create user accounts. In addition, the vendors could provide confidence scores and risk indicators that could be interpreted to judge whether the user-provided data matched who they claimed to be.

|

According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology

(NIST), the following are required at each identity assurance level (IAL)

level: · IAL1: There is no requirement to link users to a specific real-life identity. Any information provided by users should be treated as self-asserted and is neither validated nor verified.

· IAL2: The evidence provided supports the real-world existence of users’ identities and verifies that users are appropriately associated with this real-world identity. This level introduces the need for either remote or physically present identity proofing.

· IAL3: Physical presence is required for identity proofing. Identifying attributes must be verified by an authorized and trained credential service provider. Source: GAO summary of NIST information. | GAO‑25‑107000 |

· NIST IAL2 capabilities. As previously mentioned, IAL2 provides a higher assurance that a user is who they are claiming to be, by requiring evidence that supports the claimed identity. ID.me, Experian, and LexisNexis offered this capability while Login.gov did not during fiscal years 2020 to 2023. For example, once a user submitted their data and documents, Experian conducted a series of checks, including identity and document verification and biometric facial recognition to assess the risk that the user was not who they were claiming to be.

· Biometrics support. Using physiological characteristics such as fingerprints or facial features can further reduce the risk of fraud when identity proofing a user. All the commercial solutions offered biometric support while Login.gov did not during the period of our review. For example, ID.me, Experian, and LexisNexis could use facial recognition technology to compare a facial image, such as a “selfie” with a photo from a driver’s license or passport to complete the identity proofing process. ID.me could also collect fingerprints as part of its identity proofing process. Okta could use fingerprint or face scanning to authenticate users to their accounts.

· Fraud prevention measures. Fraud mitigation measures may help in preventing users with false identities from fraudulently obtaining federal benefits or sensitive information, which can harm citizens and damage the reputation of federal agencies. All the commercial solutions and Login.gov offered fraud prevention capabilities. For example, LexisNexis’s fraud detection and mitigation solutions were intended to detect fraudulent users and applicants using analytics and behavioral biometrics.[33] This process assigns a score based on the likelihood of fraud by the user during the identity proofing process.

· Third-party integration. Integrating third-party solutions to an existing environment can achieve benefits such as increased efficiency, improved scalability, and cost savings. For example, if a product lacks certain features, developers can save time by integrating a solution that includes the missing features with the existing product instead of developing the lacking capabilities. All commercial solutions and Login.gov allowed integrating their solution with third-party solutions. For example, ID.me allowed integration with other third-parties such as Google and Slack.[34]

· User support. This capability provides remediation when users are experiencing a disruption of services, such as when users are attempting to access government benefits. Login.gov, Experian, ID.me, and LexisNexis offered user support services. For example, the three commercial vendors provided a customer service option on their public websites, which users could access through multiple channels such as online ticket submission, live chat, or video chat.

Spending for Commercial Identity Proofing Solutions Was Greater than Login.gov Due to Capability Needs of Agencies

According to the spending data reported by the 24 CFO Act agencies for fiscal years 2020 to 2023, the agencies’ spending for commercial solutions was greater than Login.gov.[35] The agencies also reported that the higher spending for commercial solutions was due to the agencies needing technical capabilities that Login.gov did not offer during fiscal years 2020 to 2023. For example, a greater proportion of agencies’ spending for commercial solutions was for identity proofing because most commercial solutions offered more identity proofing capabilities (e.g., IAL2, biometrics, etc.).

The Need for Increased Identity Assurances Led to Higher Agency Spending on Commercial Solutions

During fiscal years 2020 to 2023, the 24 CFO Act agencies spent a total of approximately $241.6 million to purchase public-facing identity proofing solutions.[36] Specifically, during this period, the agencies paid about $209.1 million for commercial solutions compared to $32.5 million for Login.gov. See table 7 for agency spending on Login.gov and commercial solutions from fiscal year 2020 to fiscal year 2023.

Table 7: Agencies’ Reported Spending on Login.gov and Commercial Solutions for Public-facing Applications During Fiscal Years 2020 to 2023

|

Agency |

Login.gov |

Commercial Solution |

Total |

|

Department of Agriculture |

$132,569 |

|

$132,569 |

|

Department of Commerce |

$168,910 |

|

$168,910 |

|

Department of Defense |

$1,786,274 |

|

$1,786,274 |

|

Department of Education |

$84,983 |

|

$84,983 |

|

Department of Energya |

$366,552 |

$0 (ID.me) |

$366,552 |

|

Department of Health and Human Servicesb |

$548,601 |

|

$548,601 |

|

Department of Homeland Security |

$7,684,795 |

|

$7,684,795 |

|

Department of Housing and Urban Development |

$124,557 |

$1,980,897 (Okta) |

$2,105,454 |

|

Department of Justicec |

$0 |

|

$0 |

|

Department of Labor |

$273,042 |

|

$273,042 |

|

Department of State |

$56,048 |

|

$56,048 |

|

Department of the Interior |

$301,656 |

|

$301,656 |

|

Department of Transportation |

$1,831,062 |

|

$1,831,062 |

|

The Department of the Treasury |

$382,949 |

$146,663,007 (ID.me) |

$147,045,957 |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs |

$355,987 |

$46,660,998 (ID.me) |

$47,016,984 |

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

$144,873 |

$142,998 (LexisNexis) |

$287,871 |

|

General Services Administration |

$6,543,556 |

|

$6,543,556 |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

$117,803 |

|

$117,803 |

|

National Science Foundation |

$91,376 |

|

$91,376 |

|

Nuclear Regulatory Commission |

$0 |

$58,000 (Experian) |

$58,000 |

|

Office of Personnel Management |

$4,853,743 |

|

$4,853,743 |

|

Small Business Administration |

$3,841,243 |

|

$3,841,243 |

|

Social Security Administration |

$2,695,548 |

$13,548,024 (ID.me) |

$16,243,571 |

|

U.S. Agency for International Development |

$162,203 |

|

$162,203 |

|

All CFO Act Agencies |

$32,548,328 |

$209,053,924 |

$241,602,251 |

Source: GAO analysis of agency documentation and Login.gov billing data. | GAO‑25‑107000

The figures in this table do not include any funding from the Technology Modernization Fund. Agencies that use Okta reported that they use the solution solely for authentication.

Numbers are rounded to the nearest dollar.

aThe Department of Energy reported that their contract with ID.me started in fiscal year 2024, which was outside the scope of this review.

bThe Department of Health and Human Services did not report the requested data for this review.

cThe Department of Justice reported that they do not use any identity proofing solutions to conduct authentication or identity proofing for public-facing applications.

The majority of CFO Act agency spending on Login,gov was for authentication services, while the majority of spending on commercial solutions was for identity proofing services. In addition, the 24 CFO Act agencies spent approximately $3.9 million on fees associated with Login.gov’s administrative and other costs.[37] These fees included costs related to setting up the solutions, maintenance, and consulting fees. See figure 3 for a breakdown of the agencies’ spending on Login.gov and commercial solutions.

Note: For proprietary reasons, private vendors did not share detailed pricing information of their commercial solutions. As a result, we were not able to make a direct comparison.

The CFO Act agencies reported that their expenditures for commercial solutions were greater than Login.gov from fiscal years 2020 to 2023 due to the agencies needing technical capabilities (e.g., IAL2, biometrics, etc.) that the commercial solutions offered that Login.gov did not during that period. For example, Treasury needed to acquire IAL2 capabilities from ID.me that it required to deliver its services to the general public. Specifically, IRS processes federal tax return information (e.g., Social Security numbers, bank account numbers, and taxpayer identification numbers). Because of the sensitivity of the data, IRS requires a higher assurance that a user is who they are claiming to be. During the 2022 tax season, IRS verified over 500,000 users through IAL2 transactions for online services in a single day, with a peak of 4,282 transactions-per-second.

Similarly, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Social Security Administration spent $46.3 million and $10.9 million more, respectively, for ID.me’s services than they spent for Login.gov. This was due to the VA and the Social Security Administration needing to identity proof users from outside the United States, who may need to access veteran or social security benefits. In comparison, Login.gov requires a U.S. address to identity proof users.

Login.gov and Selected Identity Proofing Solution Vendors Largely Implemented Data Protection

As previously discussed, NIST recommended practices that organizations can implement to help improve privacy risk management activities. The Privacy Framework aims to support organizations by:

· taking privacy into account during the design and deployment of systems, products, and services that affect individuals’ privacy;

· communicating their privacy practices; and

· encouraging cross-organizational workforce collaboration among leadership, legal, and IT professionals.

According to NIST’s Privacy Framework, the “protect” function focuses primarily on data protection. Specifically, NIST describes the function as practices that address privacy and cybersecurity risk management and are intended to prevent cybersecurity-related privacy events.

Okta has fully implemented all the data protection categories in the “protect” function suggested by NIST. However, Login.gov and ID.me addressed some but not all of the five categories described.[38] See Table 8 for a description of each category and our assessment of whether Login.gov and other commercial solutions addressed the categories described for fiscal year 2023.[39]

Table 8: Extent to Which Identity Proofing Solution Vendors Aligned with the National Institute of Standards and Technology Data Protection Categories

|

Function |

Category |

Service Provider |

Rating |

|

Protect |

Data Security: Data are managed consistent with the organization’s risk strategy to protect individuals’ privacy and maintain data confidentiality, integrity, and availability |

Login.gov |

● |

|

ID.me |

◑ |

||

|

Okta |

● |

||

|

Data Protection Policies, Processes, and Procedures: Security and privacy policies, processes, and procedures are maintained and used to manage the protection of data. These should include items such as, purpose, scope, roles and responsibilities in the data processing ecosystem, and management commitment. |

Login.gov |

◑ |

|

|

ID.me |

● |

||

|

Okta |

● |

||

|

Identity Management, Authentication, and Access Control: Access to data and devices is limited to authorized individuals, processes, and devices, and is managed consistent with the assessed risk of unauthorized access. |

Login.gov |

● |

|

|

ID.me |

● |

||

|

Okta |

● |

||

|

Maintenance: System maintenance and repairs are performed consistent with policies, processes, and procedures. |

Login.gov |

● |

|

|

ID.me |

● |

||

|

Okta |

● |

||

|

Protective Technology: Technical security solutions are managed to ensure the security and resilience of systems/products/services and associated data, consistent with related policies, processes, procedures, and agreements. |

Login.gov |

● |

|

|

ID.me |

● |

||

|

Okta |

● |

Legend: ●=Addressed all elements of the practice. ◑= Addressed some, but not all, elements of the practice. ○= Did not address any elements of the practice.

Source: GAO analysis of vendor data. | GAO‑25‑107000

Each of the identity proofing solution vendors and Login.gov implemented various measures to protect the sensitive data that they process and maintain. For example:

· Data Security. Login.gov and Okta established protections for data-at-rest and in-transit. Specifically, the vendors implemented encryption, such as cryptographic mechanisms, to protect the confidentiality and integrity of sensitive data.

· Data Protection Policies, Processes, and Procedures. ID.me and Okta established processes for regular security control assessments to ensure that the security controls for protecting sensitive data were properly implemented. In addition, each vendor documented the results of the assessments and took appropriate steps to address any vulnerabilities.

· Identity Management, Authentication, and Access Control. Login.gov, ID.me, and Okta established policies and procedures to ensure that access to systems was limited to users that had a need to operate. For example, the vendors’ user credentials were issued only to authorized users and vendors implemented separation of duties and least privilege to prevent any unauthorized activity.

· Maintenance. Login.gov, ID.me, and Okta established system maintenance and repair procedures, which included scheduling, performing, and documenting any maintenance activities.

· Protective Technology. Login.gov, ID.me, and Okta implemented measures to ensure the availability of their systems through implementing power and network redundancies and establishing contingency plans that outlined recovery procedures in the event of service disruptions.

According to a 2024 FedRAMP third-party security assessment, ID.me did not fully address data security-related practices. Specifically, ID.me had implemented outdated encryption methods to protect its sensitive data. However, according to a 2025 assessment, ID.me had updated its encryption methods to fully address this practice.

However, Login.gov did not fully address the data protection practices that NIST recommends. Specifically, although Login.gov regularly backed up its data, it did not fully establish and implement policies and procedures regarding testing the backups. Data loss—whether through a ransomware attack, hardware failure, or accidental or intentional data destruction—can have catastrophic effects on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of any IT assets, services, and sensitive data. For example, if Login.gov’s backup data was not tested to ensure that its integrity was not compromised, then it could result in complete loss of data if a breach were to occur. By ensuring that data backups are maintained and testing that the integrity of the backups is not compromised, a vendor can reduce the impact of these data loss incidents.

According to GSA, the control was not fully documented and implemented because Login.gov’s security engineering team was not fully staffed until January 2024. At the conclusion of our review, GSA provided its updated policy for testing Login.gov’s backup data. However, it is not yet evident that the policy has been fully implemented or if it is achieving the intended results. Until GSA demonstrates that it has fully implemented its data protection policy to test data backups, Login.gov officials will have less assurance that they are consistently and effectively ensuring the integrity and availability of its data.

Conclusions

Login.gov and the commercial solutions process and maintain PII for millions of users each year. Accordingly, it is critical for the agencies to protect the sensitive information that they are entrusted with to prevent identity fraud and theft. Although the identity proofing solutions used by the CFO Act agencies addressed most of NIST’s data protection practices, Login.gov has not demonstrated that it fully documented and implemented its policies and procedures regarding testing its data backups. Addressing this gap will be an important step towards ensuring that the integrity and availability of that data will be protected, as well as the continuity of access to important government services that have a significant impact on the everyday lives of U.S. citizens.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Administrator of the General Services Administration should direct GSA’s Technology Transformation Services division to ensure that Login.gov demonstrates that it fully implemented the policy to test its data backups.

Agency Comments, Third-Party Views, and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft for review and comment to GSA, the agency to which we made a recommendation, as well as to the other 23 CFO agencies included in our review. We also provided relevant sections of the draft report to third parties, including Experian, ID.me, LexisNexis, and Okta.

GSA provided written comments—reprinted in appendix II—and agreed with our recommendation. The Acting Administrator stated that Login.gov is committed to upholding industry best practices in data privacy and cybersecurity, and has implemented robust data policies, including those around testing data backups. The Acting Administrator added that the agency will continue to build on this foundation and ensure there is a standardized mechanism to demonstrate its policy implementation. GSA also suggested a change to the title of the report to better reflect the findings, as well as technical comments, all of which we incorporated as appropriate.

We received emails from 21 agencies noting that they had no comments. Specifically, we received emails from the:

· Department of Agriculture’s Office of the Chief Information Officer’s Agency Audit Liaison,

· Department of Education’s Office of the Secretary’s Executive Secretariat,

· Department of Energy’s Office of Financial and Audit Management,

· Department of Health and Human Services’ Audit Liaison,

· Department of Homeland Security’s Departmental GAO-OIG Liaison Office,

· Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Audit Liaison Officer,

· Department of the Interior’s Audit Management Division,

· Department of Justice’s Audit Liaison Specialist,

· Department of Labor’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy,

· Department of State’s Bureau of the Comptroller and Global Financial Services,

· Department of Transportation’s Audit Relations and Program Improvement Office,

· Department of the Treasury’s Office of the Chief Information Officer,

· Environmental Protection Agency’s Audit Follow-up Coordinator,

· National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Audit Liaison Representative,

· National Science Foundation’s GAO Liaison,

· Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s Executive Technical Assistant,

· Office of Personnel Management’s Audit Liaison,

· Small Business Administration’s Director of the Office of Strategic Management and Enterprise Integrity,

· Social Security Administration’s Chief of Staff,

· United States Agency for International Development’s Office of the Chief Financial Officer, and

· Department of Veterans Affairs’ Congressional Relations Officer.

The two remaining agencies, the Departments of Defense and Commerce, provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We also received technical comments from two of the third-party entities, ID.me and LexisNexis, which we incorporated as appropriate. Experian and Okta did not provide comments.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the heads of the agencies in our review, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Marisol Cruz Cain at CruzCainM@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Marisol Cruz Cain

Director, Information Technology and Cybersecurity

Our objectives were to (1) examine Login.gov’s capabilities and pricing structure; (2) compare Login.gov’s capabilities to selected commercially available solutions; (3) identify reported agency spending on Login.gov and commercial solutions; and (4) evaluate the extent to which Login.gov and other selected solutions protect the sensitive data they collect and manage. The scope of our review was limited to fiscal years 2020 to 2023.

To address our first objective, we analyzed documents that detailed Login.gov’s capabilities and pricing structure, such as its privacy impact assessment, technical documentation (e.g., identity proofing process charts and system security plan), as well as pricing models from fiscal years 2020 to 2023. From these documents, we identified the capabilities of Login.gov in the areas of authentication, identity proofing, technical features (i.e., biometrics, fraud prevention, and third-party vendor integration), and support services. We also determined how much Login.gov charged its customer agencies for these services from its billing records from fiscal years 2020 to 2023. Specifically, we analyzed how much each customer agency was charged, what types of services they received, and determined the billing trends. We also interviewed Login.gov officials regarding its pricing structure and capabilities.

To address our second objective, we relied on prior GAO work to identify which solutions the 24 Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act) agencies use for identity proofing.[40] We then analyzed documents that detailed the capabilities of each of the commercial solutions, such as documents that the vendors submitted as a part of the contract solicitation process. These documents included system security plans and privacy policies that the vendors submitted to receive their Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program certification from the General Services Administration (GSA). From these documents, we identified the capabilities of the commercial solutions in the areas of authentication, identity proofing, technical features (i.e., biometrics, fraud prevention, and third-party vendor integration), and support services and compared them with Login.gov.[41] We also interviewed the third-party identity proofing solution vendors that the CFO Act agencies reported as using, regarding the capabilities their solutions offer.

For our third objective, we analyzed vendor billing and agency spending data reported by Login.gov and the CFO Act agencies associated with the use of identity proofing solutions from fiscal years 2020 to 2023.[42] We also interviewed the third-party identity proofing solution vendors regarding their pricing models. In addition, we compared the agencies’ spending information for commercial solutions with those of Login.gov. The scope of our review was limited to fiscal years 2020 to 2023 because Login.gov’s pricing structure prior to fiscal year 2020 (in which Login.gov charged its customers solely based on the total number of users that used the system) was not directly comparable to agencies who used commercial solutions.

To determine the reliability and accuracy of the data, we reviewed answers to 10 data reliability questions that addressed the internal controls of the system used to collect the data. For example, we asked questions to determine whether the system had procedures in place to consistently and accurately capture data, access controls over the data, and system changes. In addition, to verify that the data did not include obvious errors, such as missing data fields or unexplained outliers, our analysis was confirmed by a second analyst. Through these steps, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for our purposes.

For our fourth objective, we reviewed the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Privacy Framework: A Tool for Improving Privacy through Enterprise Risk Management guidance to identity privacy outcomes that were related to data protection. We specifically chose the privacy categories under the “protect” function so that we could compare the identity proofing solution vendors’ privacy and data protection policies and procedures to industry best practices for protecting sensitive data. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the “protect” function categories include privacy and cybersecurity risk management steps to help prevent cybersecurity-related privacy events. We then requested information from Login.gov, Experian, ID.me, LexisNexis, and Okta regarding how the solutions protect personally identifiable information. However, all four private solutions either did not respond to our request or cited business sensitivity concerns as their basis for not providing the information. To address this, we requested the solutions’ Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) packages from GSA. Through this process, we were able to obtain the privacy related documents for ID.me and Okta, which the solutions had submitted to GSA to be FedRAMP certified. These documents included system security plans, privacy policies and procedures, and third-party security control assessments.[43] According to GSA, Experian and LexisNexis are not cloud service providers authorized under FedRAMP. As a result, we were unable to obtain any privacy-related documents for Experian and LexisNexis to conduct this analysis.

We then compared each vendor’s policies and procedures and third-party assessment results to the Privacy Framework categories to assess the extent to which the vendors have established programs for ensuring privacy protections in accordance with these practices. To do so, we collected and analyzed the service providers’ documentation, including policies and procedures and third-party control assessments. For each practice we determined if the agency met, partially met, or did not meet each best practice based on the information collected. We considered a practice to be met if the evidence provided addressed all elements of the practice, partially met if it addressed one or more element, and not met if the evidence did not address any of the elements. After an initial determination, a second analyst reviewed the assessment for concurrence on the ratings and evidence used to support them. In cases where two analysts reached different assessments, they discussed the analysis to resolve any differences. We then interviewed Login.gov officials and the four third-party identity proofing solution vendors that the CFO Act agencies reported as using regarding the ways in which they protect sensitive data.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2023 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

In July 2024, Login.gov finalized a pricing structure for its customer agencies for the remainder of fiscal year 2024 and fiscal year 2025. Specifically, agencies are charged a fee based on their level of monthly active users for authentication services.[44] See Table 1 for the new authentication pricing model.

|

Monthly Active User Tier |

Price per Active User |

|

0 – 24,999 |

$0.1000 |

|

25,000 – 49,999 |

$0.0975 |

|

50,000 – 99,999 |

$0.0951 |

|

100,000 – 249,999 |

$0.0927 |

|

250,000 – 999,999 |

$0.0904 |

|

1,000,000 – 4,999,999 |

$0.0881 |

|

5,000,000 + |

$0.0859 |

Source: GAO analysis of Login.gov documentation. | GAO‑25‑107000

In addition, Login.gov also charges a fee for other add-on services. For example, identity proofing is an add-on service, which would cost the agencies $3 per active user in a “proofing” year and $1 per active user in a “non-proofing” year.[45] According to Login.gov’s documentation, this charging cycle is guided by a five-year credential lifecycle, where a user would be required to complete a full proofing process during the initial year and would not be required to repeat the process for five years. Exceptions would include cases of suspected fraud, where the user would be required to repeat the full proofing process (see Table 2).

|

Years |

Cost |

|

1 (need full identity proofing) |

$3 per active user |

|

2 (does not require identity proofing) |

$1 per active user |

|

3 (does not require identity proofing) |

$1 per active user |

|

4 (does not require identity proofing) |

$1 per active user |

|

5 (does not require identity proofing) |

$1 per active user |

|

6 (need full identity proofing) |

$3 per active user |

|

7 (does not require identity proofing) |

$1 per active user |

|

8 (does not require identity proofing) |

$1 per active user |

|

9 (does not require identity proofing) |

$1 per active user |

|

10 (does not require identity proofing) |

$1 per active user |

Source: GAO analysis of Login.gov documentation. | GAO‑25‑107000

In addition to the authentication and identity proofing pricing structure, Login.gov charges a monthly minimum fee of $2,500. The fee covers the first $2,500 of any combination of authentication and identity proofing transactions. If a customer agency incurred less than $2,500 in usage fees, the difference would be billed as the minimum that month. Similarly, if a customer agency incurred fees that are more than $2,500, no minimum fee would be billed for that month.

If a customer agency requests any Login.gov-related technical support that is beyond the agreed-upon scope of work in the interagency agreement, Login.gov charges $275 per hour. These services include consultation beyond the included onboarding support and must be agreed upon through an interagency agreement. In addition, Login.gov offers support for the customer agencies’ users through its contact center, which primarily answers inquiries through email and will escalate to phone support as needed.

GAO Contacts

Marisol Cruz Cain, CruzCainM@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contacts listed above, the following staff made key contributions to this report: Elena Epps (assistant director), Keith Kim (analyst in charge), Tracey Bass, Kami Brown, Kisa Bushyeager, Christopher Businsky, Chase Carroll, Kristi Dorsey, Jonnie Genova, Elizabeth Gooch, Corwin Hayward, Ceara Lance, Michael Lebowitz, Evan Nelson Senie, Sejal Sheth, Andrew Stavisky, and Adam Vodraska.