PUBLIC HEALTH PREPAREDNESS

HHS and Jurisdictions Have Taken Some Steps to Address Challenging Workforce Gaps

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107002. For more information, contact Mary Denigan-Macauley at (202) 512-7114 or deniganmacauleym@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107002, a report to congressional committees

HHS and Jurisdictions Have Taken Some Steps to Address Challenging Workforce Gaps

Why GAO Did This Study

Public health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic, Hurricane Helene, and other threats, have highlighted the importance of a public health workforce that is ready to meet the needs of its citizens.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 includes a provision for GAO to report on the public health workforce in the United States. This report describes, among other topics:

· gaps in the jurisdictional public health workforce and challenges to recruitment and retention, and

· steps HHS and selected jurisdictions have taken to address jurisdictional recruitment and retention challenges.

To address these objectives, GAO reviewed 69 public health workforce research studies and reports, and interviewed HHS officials and officials from 11 stakeholder organizations, including national organizations representing jurisdictions, public health professionals, or educational organizations; public health policy and research organizations; and a national organization focused on public health practice and population health.

GAO also interviewed officials in 11 jurisdictions, selected to obtain variation in health department structure (e.g., centralized vs. decentralized), funding sources, and percent of population in rural areas. The selected jurisdictions included four states, one territory, two tribal organizations, and four localities.

What GAO Found

The U.S. public health workforce serves a critical role protecting community health, such as by tracking disease outbreaks, monitoring water quality, and communicating with the public about health threats. Nonfederal jurisdictions within the U.S. (states, territories, Tribes, and localities, such as counties and cities) have primary responsibility for public health in their geographic areas, and these jurisdictions employ most of the public health workforce—more than 200,000 workers. The federal government, particularly the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), supports these jurisdictions’ workforces and also employs its own public health workforce.

GAO’s review found gaps between the existing public health workforce and the workforce needed. These gaps have existed across multiple occupations and jurisdictions and were exacerbated during public health emergencies. Gaps limit the ability of jurisdictions to conduct key public health functions, such as disease investigation and control, identification of hazards, and readiness to respond to emergencies.

Challenges with recruiting and retaining workers contribute to public health workforce gaps. These challenges are difficult to solve and are likely to persist over time, according to GAO’s review. For example, public health funding can be restricted to limited time frames or specific activities, which makes it difficult to use the funding for hiring. In addition, jurisdictions faced challenges dealing with market competition for workers from other employers offering higher pay, better job security, and more flexibility. Jurisdictions also can have cumbersome hiring processes based on state or local civil service requirements that are difficult to change, and public health work can involve high workloads and stress.

HHS and selected jurisdictions have taken some steps to mitigate challenges. For example:

· HHS has responded to funding challenges by offering jurisdictions greater flexibility in using certain grant funds for workforce hiring and support.

· Selected jurisdictions have addressed the challenges of market competition, cumbersome hiring processes, and stressful workplace environments by offering financial incentives and improving hiring processes. For example, Maine increased pay for public health nurses and expedited hiring processes, which helped the state fully meet its need.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ASPR |

Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response |

|

CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|

FTE |

full-time equivalent |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

HRSA |

Health Resources and Services Administration |

|

IHS |

Indian Health Service |

|

PHS Act |

Public Health Service Act |

|

SAMHSA |

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 29, 2025

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, MD

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

ChairmanThe Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The U.S. public health workforce serves a critical role protecting community health, including by ensuring the nation prepares for, responds to, and recovers from public health emergencies. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, public health workers were on the front lines, monitoring the number of cases and educating the public on how best to limit the spread of the disease. In addition, public health workers help to ensure basic health needs, such as clean drinking water, even when the U.S. is not facing health emergencies.

Nonfederal jurisdictions within the U.S.—states, territories, Tribes, and localities, such as counties and cities—have primary responsibility for public health in the areas they serve. Most of the public health workforce is employed by the more than 3,000 jurisdictional public health departments across the country. A recent study funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that, in 2022, the public health workforce in state and local jurisdictions included a total of 239,000 individuals, with approximately 30 percent of that workforce at the state level and 70 percent at the local level.[1] Jurisdictions employ a wide variety of public health staff, such as nurses and community health workers, and depend on them to deliver essential services, such as vaccine administration.

The federal government, particularly the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), also has a role in supporting the jurisdictional public health workforce. For example, HHS agencies assist jurisdictions through funding and other resources to help support their operations, and jurisdictions may request additional support from the federal government when their public health capabilities become overwhelmed due to disasters or other emergencies.[2] HHS and its component agencies, such as CDC, also employ public health professionals such as epidemiologists, though its public health workforce is smaller than the jurisdictional workforce.[3]

Public health leaders are concerned about gaps in the public health workforce, and challenges hiring and retaining staff, due in part to significant changes in the workforce over the past several years. Recent research shows that the state and local public health workforce generally declined in size following the recession of 2008–2009.[4] This decline generally persisted over the next decade, even as other sectors of the economy recovered, to varying degrees.[5] In response to the urgent needs of the COVID-19 pandemic, many public health departments have expanded their workforce, including by adding short-term employees.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 includes a provision for us to report on what is known about the public health workforce in the United States.[6] This report describes:

1. gaps in the jurisdictional public health workforce and challenges to recruitment and retention, and

2. steps HHS and selected jurisdictions have taken to address jurisdictional recruitment and retention challenges.

In addition to these objectives, Appendix I includes examples of HHS efforts to identify and address gaps in its federal public health workforce.

To describe gaps in the public health workforce and challenges to recruitment and retention, we reviewed related studies and interviewed officials or reviewed written documents from jurisdictions, HHS, and stakeholder organizations. We focused this objective on public health workforce gaps and challenges experienced by jurisdictions at the state, territorial, tribal, and local levels.

Study identification and analysis. We identified studies through a search of research databases, such as MEDLINE and ABI/INFORM. Specifically, we searched for studies on the public health workforce, public health workforce gaps, and challenges to recruitment and retention, as well as for studies that analyzed survey data on the public health workforce. Using these criteria, we identified 35 studies published from January 2022 to April 2024 that were specifically related to public health workforce, public health workforce gaps and challenges, or related data. In addition to these articles, we also identified 34 other studies on the public health workforce, including those published by national stakeholders, research, and policy organizations such as the de Beaumont Foundation, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, as well as government agencies like the CDC and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). In total, we analyzed 69 studies and reports, identified as described above, for information on the public health workforce. See Appendix II for additional detail on our study review.

Jurisdictions. We interviewed officials with responsibilities for public health at 11 jurisdictions—four states, one territory, two tribal organizations, and four localities: California; Maine; Maryland; South Carolina; the U.S. Virgin Islands; Wabanaki Health and Wellness; the California Rural Indian Health Board; Los Angeles County, California; the city of Baltimore, Maryland; Garrett County, Maryland; and the city of Portland, Maine. Where applicable, we also reviewed documents related to jurisdictions’ public health workforce. We selected these state and territorial jurisdictions to reflect variation in health department structure (such as whether state health agencies and local health departments were separate or combined), variation in sources of funding, and percent of population residing in rural areas. We selected tribal organizations and localities within the selected states. These interviews provided insights into the specific workforce gaps and related challenges experienced at each jurisdiction, and they are not generalizable to other jurisdictions. To help ensure the accuracy of the facts and statements presented from our interviews, we provided relevant excerpts of the draft report to the jurisdictions we interviewed. We incorporated, as appropriate, their technical comments.

HHS. We reviewed documents and interviewed officials from HHS agencies or offices to understand the support they provide jurisdictions with respect to the public health workforce. These supporting agencies were the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), CDC, HRSA, Indian Health Service (IHS), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. We reviewed documents and interviewed officials from these agencies and HHS’s Office of Human Resources to understand HHS’s role supporting the jurisdictional workforce, and gaps in HHS’s workforce and efforts to close those gaps.

Stakeholder organizations. We interviewed officials from 11 public health stakeholder organizations we identified based on their knowledge of, research on, and work with the public health workforce. We selected three national stakeholder organizations that represent state, local, territorial, or tribal health departments; two national stakeholder organizations that represent public health professionals; one national network of institutes focused on advancing public health practice and population health; two policy and research institutes; one national public health academic association; one national public health accreditation organization; and, one national advisory committee.[7] These interviews provided insights into workforce gaps and related challenges identified by these organizations, and they are not generalizable to other entities.

To describe ways that HHS and selected jurisdictions have addressed recruitment and retention challenges, we reviewed documents and interviewed officials from the HHS agencies, selected jurisdictions, and stakeholder organizations noted above. These sources identified actions that HHS and selected jurisdictions took to address recruitment and retention challenges. We categorized these actions and determined how they compared to the specific challenges identified for our first objective, but we did not assess HHS’s or jurisdictions’ planning efforts.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Public Health and Jurisdictions

Broadly speaking, public health work seeks to protect and improve the health of populations and communities by promoting healthy lifestyles, researching disease and injury prevention, and detecting, preventing, and responding to infectious diseases. The public health community also seeks to reduce health disparities by promoting health care equity, quality, and accessibility.[8] The United States has 59 state and territorial public health departments, and approximately 3,000 county, city, and tribal health departments.[9] These jurisdictions provide essential public health services, such as communicable disease control, chronic disease and injury prevention, health inspections of businesses, maternal and child health services, and facilitation of access to clinical health care providers.

Jurisdictions vary in the public health services they provide depending on the needs of their populations, the resources available to them, and the availability of health care from other organizations. For example, a county health department may provide certain clinical health services, such as behavioral health care, if these services are not sufficiently available or accessible through local health care providers. Likewise, jurisdictions exhibit wide variation in how their health departments are organized and operated—there is no standard for how they must be structured and thus, wide variation exists across jurisdictions. For example, state public health agencies may be part of larger state departments, or they may be stand-alone state agencies. In addition, in some cases local jurisdictions, which include counties or cities, are units of the state health department, while in other cases they operate more independently.[10] Similar variation exists in how jurisdictions are funded.[11] Jurisdictions vary in their funding sources and amounts they receive. They may receive funds from a mix of different federal or state grants, local property taxes, or other organizations, such as foundations.

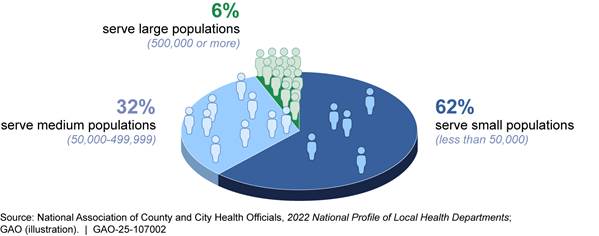

Jurisdictions also vary in the size of the population they serve. For example, according to recent nationwide data, 62 percent of city and county health departments serve small populations of less than 50,000 people, and these health departments serve approximately 9 percent of the U.S. population. In contrast, only 6 percent of city and county health departments serve populations of 500,000 people or more (see figure 1). In total, however, the departments in these larger jurisdictions are responsible for serving more than half the U.S. population.

Figure 1: Percent of City and County Health Departments Serving Small, Medium, or Large Populations (N=2,512)

Public Health Workforce

Jurisdictions employ public health workers in several broad areas, which can overlap:

· Addressing public health issues. Some staff focus on directly addressing public health issues, such as by monitoring disease outbreaks and promoting wellness within a community. For example, epidemiologists and laboratory staff detect and assess community-level health threats, including diseases, genetic disorders, and contaminants or toxins. Staff in these professions may also be employed in other settings, such as academia or private research facilities. For instance, in a hospital setting, laboratory staff might conduct blood tests or pathology reviews of tissue samples on individual patients.

· Providing clinical care to address public health needs. Jurisdictional health departments also have staff, such as nurses or physician assistants, who deliver clinical care services that are not widely available or accessible from medical providers or that are important for community health, such as vaccinations.

· Providing administrative and operational support. Certain staff are responsible for the operation of public health departments, such as human resource specialists responsible for hiring, or grants specialists and contract managers responsible for managing funding sources.

Workforces in each of these areas may help prepare for and respond to public health threats or emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Hurricane Helene. The following are examples of occupations in the public health workforce and descriptions of the work they do:

· Public health nurses. Public health nurses work to prevent disease and promote community health and safety. They may look at health trends, identify health risk factors, and work to improve access to health services.

· Epidemiologists. Epidemiologists use science, mathematics, and statistics to collect and analyze data on public health, including detecting and monitoring disease outbreaks and studying risk factors and causes of disease.

· Health educators. Health educators provide education, resources, programs, and services to improve community health and to share information on health threats. These staff may also be referred to as wellness coordinators, or outreach managers.

· Health inspectors. There are a variety of inspectors working in public health departments, such as those that inspect restaurants for food safety issues. In other cases, inspectors may focus on environmental health issues, such as community water or air quality.

HHS Agencies Involved in Jurisdictional Public Health

HHS and its component agencies lead federal public health efforts, including efforts to support the jurisdictional public health workforce. HHS agencies with significant involvement in supporting the public health workforce include the following:

· ASPR leads the nation’s medical and public health preparedness for, response to, and recovery from disasters and public health emergencies. ASPR collaborates with health care providers, jurisdictions, community members, and other partners to improve readiness and response capabilities.

· CDC’s responsibilities include helping strengthen jurisdictions’ public health infrastructure—the people, services, and systems needed to promote and protect health, including the public health workforce.

· HRSA supports jurisdictional public health needs through programs focused on the nation’s highest-need communities, including programs focused on the health workforce, such as scholarship and loan repayment programs.

· IHS funds and provides medical and public health services, including environmental engineering services and sanitation facilities, to American Indians and Alaska Natives who are members or descendants of federally recognized Tribes.[12] IHS also provides support to students pursuing medical education to staff Indian health programs.

· SAMHSA leads public health efforts to advance the behavioral health of the nation and to promote mental health, prevent substance misuse, and provide treatments and supports to foster recovery while ensuring equitable access and better outcomes.

We previously reported on various aspects of HHS’s workforce planning, and we have made various recommendations for improvements. For example, in 2024 we recommended ways for ASPR to address ongoing workforce planning problems and improve emergency response.[13] In addition, workforce planning issues were part of the reason that we added HHS’s leadership and coordination of public health emergencies to our High-Risk list in 2022.[14]

Jurisdictions Face Multiple Workforce Gaps, and Recruitment and Retention Challenges, Including Those Related to Market Competition and Hiring Processes

Public Health Workforce Gaps Are Found in Multiple Occupations and Skills, and Vary by Location

Jurisdictions face widespread gaps in their existing workforce compared to the workforce needed to provide public health services, based on our review of studies and interviews with selected jurisdictions and stakeholder organizations. In particular, jurisdictions face gaps across multiple occupations and skills, with variation by location. Such public health workforce gaps are exacerbated during public health emergencies, according to our review, with some jurisdictions experiencing gaps in multiple different occupations. HHS also faces gaps in its public health workforce, and we include information on these HHS gaps in Appendix I.

Gaps Overall and across Multiple Occupations

Overall, state and local public health departments across the country would need 80,000 additional full-time equivalent (FTE) workers to deliver certain public health services, according to a 2021 national study by the de Beaumont Foundation, an 80 percent increase above existing staffing levels for those services.[15] Specifically, the de Beaumont Foundation study estimated that 54,000 additional FTEs were needed in local health departments and 26,000 were needed in state health departments for staff in multiple occupations to address such areas as chronic disease and injury, and communicable disease.

Jurisdictions also faced gaps in multiple and varied occupations, according to our review of studies and our interviews.

· Officials we interviewed from 10 of the 11 selected jurisdictions indicated they had workforce gaps across multiple occupations. For example, the Garrett County Department of Health in Maryland faced gaps in nursing staff, social workers, behavioral health therapists, epidemiologists, environmental health specialists, and clerical staff, according to officials. Officials from South Carolina’s Department of Public Health noted workforce gaps in nursing, nutritionists, laboratory staff, and epidemiologists. Officials with the California Rural Indian Health Board cited gaps with nursing, epidemiologists, and business and financial operations staff.

· Officials we interviewed with the California Department of Public Health reported high vacancy rates across multiple occupations in its budgeted staff allocation for 2024, with the highest vacancy rates for medical consultants (55 percent), public health medical officers (37 percent), public health microbiologists (30 percent), and nurse consultants (22 percent). The department issued reports in 2021 estimating the need for 450 additional public health staff at the state level and between 1,490 and 1,815 additional staff at local health departments beyond budgeted staffing levels, to meet state public health demands, an increase of between 10 and 12 percent.[16]

· A 2022 study of 34 New York local health departments found they also had gaps across multiple occupations including nursing, community health workers, health educators and laboratory workers.[17] Vacancy rates were as high as 39 percent for licensed practical or vocational nurses.

· A 2023 study of 72 local health departments in Minnesota found vacancies in a variety of occupational categories for 2022. The most frequently reported categories were public health nurses, public health educators, and administrative staff positions. In addition, beyond those vacancies, local health departments cited the need to create additional positions for occupational categories such as health planners, research analysts, and community health workers.[18]

Gaps in Selected Occupations

While jurisdictions face gaps in multiple and varied occupations, our review of studies and our interviews highlighted particular gaps in three types of occupations: nurses, epidemiologists, and operational support. Officials we interviewed and documentation we reviewed, indicated that public health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighted these occupational gaps as they created new public health needs—such as investigation and testing—and worsened gaps that existed before the emergencies.

Nurses. Studies we reviewed of local health departments in Minnesota (2022) and New York (2021) identified nursing as a particular and substantial workforce gap.[19] Nurses were the second largest occupational group in state and local health departments in 2019, according to one of the studies.[20] In addition, data on the overall nursing workforce—not limited to public health departments—indicate a large shortage of nurses that is projected to continue over time. HRSA’s nursing workforce projections indicate a projected shortage of 350,540 full-time equivalent registered nurses in 2026 and a shortage of 358,170 in 2031.[21] In addition, officials we interviewed from 8 of 11 jurisdictions told us they experienced workforce gaps for public health nurses, including three jurisdictions where officials identified nursing as one of their greatest workforce needs.

Epidemiologists. State health departments need a total of 2,537 additional epidemiologists—about 44 percent more than current levels—to reach full capacity, according to a 2024 survey conducted by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists.[22] In addition, the survey found that state health departments are also expected to lose a total of more than 1,000 epidemiologists that had been supported with funding related to the COVID-19 pandemic, making the need greater. Consistent with this survey, officials we interviewed from 5 of 11 selected jurisdictions said they experienced workforce gaps in epidemiologists. A 2016 survey of state and local health departments also found that state health departments ranked epidemiologists as a “higher priority” occupation than nine other occupation categories listed.[23]

Operational support. Officials we interviewed from 7 of 11 selected jurisdictions said they experienced key workforce gaps in operational functions, such as human resources, grants management, financial operations, and legal services. These occupations are not unique to public health, but stakeholder officials told us that they are essential for successful operation of public health departments. Financial and operations support workers represented one of the four largest occupational groups in state and local public health departments in 2019, according to one study.[24]

Our review of studies and our interviews found that jurisdictions’ experiences responding to the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted gaps in key operational support occupations. The pandemic revealed that jurisdictions did not have sufficient staff in human resources, finance, and procurement, according to one study.[25] Four jurisdictions did not initially have the necessary human resources staff to manage increased hiring and three did not have enough grants management staff, when federal emergency funding became available, according to our interviews and review of documentation. An official with a stakeholder organization noted that historically some jurisdictions had undervalued finance and accounting functions but said that the importance of these positions became clear during the COVID-19 pandemic, when they faced urgent needs to manage increasingly complicated financial resources. Specifically, the insufficient levels of human resources and accounting staff before an emergency adversely affected the jurisdictions’ ability to hire staff quickly, when necessary, for emergency response.

Skill Gaps in Informatics and Leadership

Jurisdictions also face gaps in staff with knowledge of informatics, leadership skills, and training in public health, according to studies and interviews.

Informatics and data analysis skills. Our review of studies and our interviews indicate that there are gaps in skills related to informatics and data analysis in the public health workforce.[26]

Recent studies indicate that informatics is one of the most significant public health training needs, and can help public health departments improve disease surveillance and better address public health needs and disparities. A 2023 report for HHS by Mathematica, highlighted the importance of informatics skills, especially for responding to public health emergencies.[27] In addition, informatics skills were identified as a higher priority workforce need by 72 percent of state health departments, according to one study.[28] A national survey of 43,695 employees of state and local health departments found that fewer than 5.5 percent of the workforce at state public health departments and 2 percent of the workforce at local public health departments identified as having specialty expertise in informatics or information technology.[29]

Similarly, officials with five of the jurisdictions we interviewed expressed a need for personnel with informatics competencies. In addition, officials with a national stakeholder organization told us there was a gap in the availability of people who understand informatics, and who can use available data to identify community hazards and available assets to address such hazards.

Leadership skills. A national survey of the public health workforce identified gaps in leadership experience and knowledge within public health departments. In particular, this survey found that 32.5 percent of public health department supervisors and managers identified themselves as having low skills in some areas they reported to be somewhat or very important to their work. These included skills related to building cross-sector partnerships and understanding social determinants of health.[30]

According to officials we interviewed and documents we reviewed from national stakeholder organizations, these skills represent key capabilities needed by public health departments. For example, building cross-sector partnerships can provide access to staff and resources that are not available in a particular public health department, and an adequate understanding of social determinants of health can help public health departments to more effectively address the causes of health problems in affected communities. These leadership skills gaps, such as those relating to management skills or how government systems work, result in part from high turnover among experienced management staff, according to officials with three national stakeholder organizations we interviewed.

In addition to these skill gaps, most of the public health workforce—86 percent, according to a national survey—does not have a bachelor’s or more advanced degree in public health.[31] Although such training is not required for many public health occupations, studies have reported on its benefits, such as preparing staff to engage in activities designed to prevent health concerns, like foodborne illnesses.[32]

Gaps in Rural Areas and Regional Variation

Gaps in the public health workforce can be more severe in rural areas, and can vary by region, based on our review.

Gaps in certain rural areas. Rural local public health departments have fewer resources and provide fewer services compared with urban and suburban health departments, according to studies on rural public health.[33] Officials we spoke with in three state jurisdictions and a regional tribal organization reported that workforce gaps were more common in the rural areas they served.

Officials in one jurisdiction said, for example, that people with more specialized skill sets tend to live in urban areas. In addition, rural areas may face greater needs for clinical health services, due to hospital closures or other workforce shortages in the availability of clinical care.[34] Therefore, in addition to staff with expertise in public health, rural public health departments may need to hire clinical staff to provide needed clinical services, such as prenatal and pediatric care.

Gaps and variation across regions. Two studies of the public health workforce found regional variation in workforce supply, indicating that some jurisdictions may have certain workforce gaps while others may not.

· Nursing workforce projections by HRSA found that workforce supply and shortages vary widely across states. While some states are projected to have an adequate supply of nurses in 2036, others, such as Georgia, California, and Washington, are projected to have shortages, with one state projected to have a nursing shortage as large as 29 percent.[35]

· A 2024 study estimating the public health workforce in 2022 found that the ratio of workers to population varied widely across 10 federally defined regional groups of states, ranging from an estimated high of 97 state and local public health workers per 100,000 population for Region 1 (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) to an estimated low of 59 per 100,000 population for Region 6 (Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas).[36]

Gaps Exacerbated during Public Health Emergencies

Gaps found in the public health workforce may be exacerbated during public health emergencies as needs increase, especially when accompanied by staff departures. The public health workforce declined 17 percent from 2008 to 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a 2019 nationwide survey of county and city health officials.[37] Gaps that existed before an emergency arose—for example in emergency preparedness and response—made it more difficult for jurisdictions to increase the workforce when necessary for a public health emergency, according to a 2023 report for HHS by Mathematica, and several jurisdiction officials we interviewed.[38]

These gaps and other factors, such as public mistrust and criticism of public health workers, increased stress among the workforce and contributed to departures during and following the COVID-19 pandemic.[39]

Recruitment and Retention Challenges Related to Funding Restrictions, Market Competition, Hiring Processes, and Work Environment Contribute to Workforce Gaps

Challenges with recruiting and retaining workers contribute to public health workforce gaps, according to our review of studies and interviews with stakeholder organizations and jurisdictions.[40] Specific challenges faced by jurisdictions include short-term and categorical funding restrictions, market competition (including salary disparities), cumbersome hiring processes, and an unfavorable work environment.

Short-term and categorical funding restrictions. Jurisdictions receive a significant portion of their funding through awards from the federal government, states, and other sources. The laws that appropriate this funding may require the funds to be restricted to a short-term time frame, or they may be restricted to specific categories of activities (known as categorical funding)—for example, to address a particular disease (e.g., diabetes) or purpose (e.g., supporting laboratory capacity). However, public health departments often seek to recruit and retain staff for longer time periods, and staff with responsibility for addressing multiple diseases and many purposes. Therefore, public health jurisdictions face challenges using funding with these restrictions for recruiting and retaining their workforce.

Our review identified the following challenges related to short-term funding:

· One recent study funded by HHS reported that a lack of sustained, longer-term public health funding was one of the most common barriers to recruiting and retaining jurisdictional public health workers.[41] According to this study, short-term funding can lead to cycles of hiring temporary workers who cannot be retained beyond award periods. National stakeholder organizations and officials from California Department of Public Health noted that these temporary positions are not attractive to prospective workers looking for stable employment.

· Officials at one local public health department explained that their temporary positions have inferior employment benefits, which they said may make the workers difficult to retain. A national stakeholder organization and other jurisdictional officials further stated that jurisdictions may make significant training investments for some temporary workers, but then lose the benefits of these investments if they cannot retain staff.

· Some jurisdictions may not be permitted to hire permanent public health workers with short-term funding. An official at a national stakeholder organization described one state in which programs must have secured five years of funding to receive approval to hire permanent positions, and the officials stated that such five-year funding is rare in public health.

Our review identified that categorical funding may pose challenges for jurisdictions seeking to hire staff to address local public health priorities or staff to fill crosscutting positions. For example, we and HHS have reported that jurisdictions were unable to use funding or staff hired with COVID-19 response funding to conduct investigations or respond to other emerging infections (e.g., hepatitis and mpox), even though communities were experiencing outbreaks.[42] In addition, officials in the California Department of Public Health told us that categorical restrictions on funding use limits their department’s ability to adequately address growing community needs.

Market competition. Jurisdictions faced challenges dealing with market competition for public health workers from employers outside the government offering higher pay, better job security and more flexibility, our review of studies and our interviews found. Studies noted that this market competition can be especially challenging because public health jurisdictions compete for workers with private health care providers, who generally can offer much higher salaries. For example:

· Several studies cited occupational pay disparities between the private and public sectors. For example, state and local public sector pay was about 10 to 47 percent less than in the private sector for 10 of the occupations reviewed in one study involving data from 2021 and 2022.[43] These occupations included chief executives, epidemiologists, computer and information systems managers, occupational health and safety specialists and technicians, and emergency management directors.

· Studies also found that, among jurisdictional workers who intend to leave their positions, a large share cited pay as one of reasons for considering leaving. One study showed that pay was the most frequently cited reason for considering leaving (63%) among younger jurisdictional public health workers, aged 35 or younger who were considering leaving.[44]

One study of employment data for 2015-2020 public health graduate degree programs found that fewer were employed in government, than in for-profit health care, or non-profit organizations.[45] Representatives we interviewed from national stakeholder organizations told us health departments generally cannot offer public health graduates salaries that are competitive with salaries offered by private sector and some non-profit organizations, and that it is therefore difficult for them to hire such graduates.

Officials we interviewed from our selected jurisdictions also provided examples of recruitment and retention challenges related to market competition and pay. For example:

· Officials in two jurisdictions said that hiring and retaining nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic became especially challenging, as hospitals and other organizations were able to offer substantially higher pay.

· Officials from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health told us that they have a hard time recruiting and retaining staff in certain occupations, especially positions where there is large demand and higher pay in the private sector. Officials said that employees may work at the department long enough to be trained as registered environmental health specialists, and then leave for higher paid positions in private sector environmental or occupational health units.

· At the state level, the California Department of Public Health told us that their most difficult retention challenges—for medical, scientific, administrative, clerical, and laboratory staff—are due to competition from both private and public sector organizations, including competition from some California counties and the federal government.

Cumbersome hiring processes. Our review of studies and interviews with national stakeholder organizations and jurisdictions identified restrictive or cumbersome hiring processes that may delay hiring and hinder recruitment. This can result in applicants accepting other job offers before a jurisdiction can complete the hiring process. Jurisdictions may also not be able to fill vacated positions quickly, leading to workforce gaps and loss of institutional knowledge. For example:

· One national stakeholder organization stated that jurisdictions have different hiring process mandates, rules, and systems that can delay hiring by 6 months and that prospective employees who need jobs are typically not able to wait that long.

· Even when jurisdictions have funding available to hire staff, some have not been able to fill some positions due to the length of time needed for civil service hiring processes, according to an official from a national stakeholder organization representing public health jurisdictions. Similarly, our interviews with jurisdiction officials indicated that many use civil service hiring processes that involve lengthy applications, exams, and background checks.

· Another national stakeholder organization official said that not having sufficient human resource and accounting capacity in jurisdictions contributes to lengthy hiring processes.

· Officials at Maine’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention told us that they paused hiring for multiple years for two key positions—a data modernization director and a workforce director—to classify the new positions through the state Bureau of Human Resources and then obtain approval from the state Department of Administrative and Financial Services.

· Some jurisdictions are required to use standardized job descriptions, which officials noted also contributes to cumbersome processes, according to our interviews. In particular, jurisdictions may be restricted from updating and tailoring job descriptions to specific public health roles. In these cases, jurisdictions may have to use job descriptions that do not adequately explain the position being filled, which may result in a candidate pool not aligned with the skill set needed. For example, officials in California and Maryland told us that they could only post jobs within rigid categories that do not match the needs of the positions, such as an accountant position that used a job description posting titled “Administrator 5.” According to officials from two national stakeholder organizations we interviewed, revising these job descriptions would be a long and challenging process, involving multiple entities across the state governments.

· A 2022 study found that applicants seeking government public health employment may struggle to identify and understand position descriptions and required qualifications, for example, because of job descriptions that do not clearly describe job responsibilities.[46]

· Officials from two national stakeholder organizations also identified that there are problems resulting from job descriptions not reflecting what the actual job entails. One of these organizations told us that inadequate job descriptions often lead to new employees quitting shortly after being hired, if they discover that the actual responsibilities of the job are different than they expected.

Unfavorable work environment. Our review of studies and our interviews identified workload, stress, and burnout; a lack of advancement opportunities; and a lack of remote work options as contributing to an unfavorable work environment for public health. These factors can hinder recruitment and retention.

· Studies identified heavy workload, stress, and burnout as a reason for employees leaving, or considering leaving, work in public health departments. A 2023 study found that in 2021, more than 40 percent of jurisdictional employees cited workload and burnout, and 37 percent cited stress as a reason for considering leaving their jobs.[47] For jurisdictional public health employees under the age of 50, workload and burnout were cited by 46 percent and stress was cited by 42 percent.

· Another study using the same data source found that, among those ages 35 and younger with intent to leave their jurisdictional public health employment, 44 percent cited overload and burnout and 39 percent cited stress as reasons for considering leaving.[48] The length and intensity of the COVID-19 pandemic amplified stress and burnout among public health workers, and made it difficult for jurisdictions to retain staff, according to studies, stakeholders and jurisdictions.

· The same studies of jurisdictional public health workers found that lack of advancement opportunities was among the most frequently selected reasons for considering leaving governmental public health service in 2021. Jurisdiction officials we interviewed said that pathways for advancement may be especially limited among specialized public health occupations.

· Two jurisdictions described how requirements to work in the office every day have made recruitment and retention challenges more difficult. An official from the California Rural Indian Health Board told us that the organization experienced significant turnover when employees wanted to remain remote following the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, officials at the Baltimore City Health Department said that their organization has experienced recruitment and retention challenges because some positions that had been remote began requiring an in-office presence.[49]

Although Some Recruitment and Retention Challenges Are Pervasive and Systemic, HHS and Selected Jurisdictions Have Taken Some Steps to Mitigate Them

Systemic Factors Make Gaps and Recruitment and Retention Challenges Difficult to Fully Address

Some of the challenges to recruitment and retention are pervasive and systemic, making it difficult for HHS and jurisdictions to address gaps fully. Key systemic factors relate to competition in the broader health care industry, jurisdictional employment requirements and decisions about funding levels, and the historic pattern of public health funding structures, according to our review of studies and our interviews with officials from selected jurisdictions, and stakeholder organizations.

Broader health care industry competition. The challenge of market competition, discussed earlier, is complicated to solve due to the competitive advantages of other employers in the health care industry, when compared with jurisdictions. Commercial health care delivery systems, as well as health insurers and pharmaceutical companies, may seek workers with the same skills valued by public health jurisdictions, but have greater resources that allow them to offer higher salaries, according to studies and national stakeholders.[50] Competition has been particularly acute for high-demand professions, such as nursing, physicians, and epidemiologists, and during public health emergencies, such as COVID-19 pandemic, according to officials we interviewed. In addition, one study in our review noted a significant increase in hiring of candidates with master’s-level public health training by pharmaceutical firms and health insurance companies from March 2020 through October 2020—during the COVID-19 pandemic—compared to a year earlier.[51]

The challenge faced by jurisdictions in providing competitive salary and benefit packages is further exacerbated by broader economic factors such as rising education costs and related increasing student debt, and the rising cost of living. These factors may influence employees to maximize their salaries through private-sector employment, according to our review of studies and our interviews with some stakeholders. Across 157 schools, the median loan for a master’s degree in public health, based on combined data for academic years 2017-2018 and 2018-2019, ranged from $8,185 to $100,000, according to one study.[52]

Jurisdictional employment requirements. Jurisdictions—which have primary responsibility and decision-making authority for their public health services—may face challenges attempting to change cumbersome hiring processes. In particular, they may be subject to state or local civil service requirements that make it complicated to alter salary structures, job titles, job descriptions, or recruitment processes to improve their effectiveness in hiring public health workforce occupations, according to our review of studies and our interviews. Some of these requirements were designed to accommodate a broad range of civil service positions, thus making it challenging to effectively target the hiring process to the public health workforce. Longstanding civil service and merit-based requirements, while intended to foster fairness, can result in cumbersome, slow hiring processes, according to two studies in our review.[53]

Jurisdictional funding levels. State and local governments vary widely in how much funding they choose to provide for public health, according to our review of studies and our interviews. Further, some jurisdictions have fewer resources to address public health workforce challenges. Funding may vary based on the total amount of resources available to a jurisdiction, and also based on the need to fund other key state or local responsibilities, such as Medicaid and public education.[54] One study found that per capita public health funding varied widely across states in 2021: among 45 states, per capita public health funding ranged from $7 in Missouri to $159 in New Mexico.[55] Another study of 16 local health departments in four states (Minnesota, Missouri, New York, and West Virginia) found that their spending for core public health services ranged from $1.10 to $26.19, per capita.[56]

Public health funding structures. The challenges of short-term and categorical funding, as described earlier, are related to the way that public health has been funded over time. In 2012, the Institute of Medicine issued a report that reviewed funding structures for public health and their use in improving health outcomes.[57] Among other things, the report found that:

· compartmentalized inflexible funding leaves many health departments without financing for key priorities or for needed cross-cutting capabilities, such as information systems and policy analysis; and

· funding from different levels of government is often uncoordinated and has different rules for use.

These findings are consistent with the situation described by officials we interviewed and other studies we reviewed. For example, a 2022 study that reexamined the issues highlighted by the Institute of Medicine’s 2012 report found no significant changes to funding structures that might improve conditions.[58]

HHS and Selected Jurisdictions Use a Broad Range of Actions Aimed at Reducing Recruitment and Retention Challenges That Contribute to Workforce Gaps

While the systemic factors make public health workforce challenges difficult to solve, HHS and the selected jurisdictions in our review have taken a broad range of actions aimed at addressing the recruitment and retention challenges that contribute to jurisdictions’ workforce gaps according to our interviews with jurisdictions, stakeholder organizations, and agencies. We grouped these actions into six broad areas: financial incentives, improved hiring processes, workplace environment improvements, pathway expansion, funding flexibility, and special resources for responding to disasters or public health emergencies. In some cases, an action may be aimed at addressing more than one recruitment and retention challenge, or multiple actions may address the same challenge. (In addition to these actions aimed at reducing jurisdictional public health workforce gaps, HHS also has taken action to address public health workforce gaps in HHS agencies. Appendix I includes examples of these actions.)

Financial incentives. HHS and selected jurisdictions have offered financial incentives aimed at addressing the challenge of market competition. Financial incentives include increased pay, recruitment bonuses, competitive benefits, and student loan repayment or forgiveness. Increased pay can be limited to certain mission critical or hard-to-fill occupations, increasing the likelihood of recruiting and retaining candidates to public health jobs that would otherwise be lower paying. For example, officials in several jurisdictions described their efforts to increase pay for nurses:

· The Baltimore City Health Department added pay incentives for new public health nurses and provided bonuses to existing nurses.

· The South Carolina Department of Health worked to change the state’s job classification system, which resulted in significant pay increases for some nurses.

· Maine’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention received approval to offer an additional 15 percent stipend after demonstrating the difficulty of hiring public health nurses.

Jurisdictions may increase pay, for example, for positions that are especially challenging to fill, as part of their regular budget processes. In this way, they focus salary increases on occupations with large gaps between jurisdiction and market pay. For example, according to officials, the Maryland Department of Health requested that the state Department of Budget and Management conduct a salary review for environmental health professionals. When officials identified significantly lower pay at the state level compared to Maryland counties, the state increased state salaries for the environmental health classification.

Similarly, student loan repayment or forgiveness may improve recruitment efforts by making it feasible for graduates with student loan debt to accept lower paying positions in governmental public health departments. Additionally, scholarship programs can provide incentives to pursue training and careers in public health. For example, to improve recruitment and retention outcomes, beginning in 2022, HRSA’s Public Health Scholarship Program provided training scholarships specifically for public health students. According to HRSA officials, in the program’s first year, 840 students received a total of $5,894,684 in scholarship funding.[59]

Improved hiring processes. CDC helped jurisdictions address the challenges of cumbersome hiring processes and market competition through direct placement of CDC field staff to support public health programs funded through CDC.

For example, the CDC Career Epidemiology Field Officer network provides states and other jurisdictions with senior-level epidemiologists directly, bypassing jurisdictional hiring processes. According to CDC officials, CDC developed this program to strengthen the epidemiology capacity to support emergency preparedness and response in state, local, and territorial health departments, and to build a network among health departments and CDC to aid in a coordinated response to public health threats. CDC data indicate that as of December 2024, 51 field officers had been placed in jurisdictions.

Officials with the Los Angeles County Department of Health created a staff position to focus on recruiting outreach efforts to colleges and non-profit organizations and on communicating with prospective job applicants through social media platforms such as Instagram and LinkedIn. According to officials, this enhanced communication helped potential applicants understand and navigate the county’s cumbersome hiring process requirements. To address similar challenges, Maine’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention expedited its application review process for hiring public health nurses. Maine officials stated that their relatively slow hiring process was placing them at a competitive disadvantage for hiring, and they credited the initiative with enabling them to fully staff the state’s public health nursing team.

Workplace environment improvements. HHS and selected jurisdictions have taken action to improve the work environment in jurisdictions, such as by providing greater workplace flexibility, addressing burnout and heavy workloads, improving supervision and leadership, and providing advancement opportunities, such as through training. In this way, workplace environment improvements and expanded advancement opportunities can help address challenges with market competition and unfavorable work environments. Examples include the following:

· The flexibility of CDC’s Public Health Infrastructure Grant enabled the Baltimore City Health Department to hire a Wellness and Culture Manager to help improve well-being and stress levels among staff, according to jurisdiction officials.

· South Carolina Department of Public Health officials credited their telework policy with helping the Department recruit and retain employees, while maintaining or improving productivity.

· The California Department of Public Health created the California Public Health Workforce Career Ladder Funding Program, which, to improve worker retention, provides grants to local jurisdictions and reimbursement to state employees, and training opportunities and professional development for existing public health workers, according to documentation provided by officials.

· HRSA supports the Rural Public Health Workforce Training Network Program, which provides assistance with training and job placement services in rural and tribal communities. The program aims to expand health services capacity by supporting public health job development, training, and placement.

· CDC provides workforce development resources and training programs through an online platform, CDC TRAIN. This platform is available to jurisdictional public health professionals and others and provides learning resources and training opportunities on a wide variety of public health topics, according to agency officials. According to agency documentation, the program provided free continuing education through this platform to 232,000 unique health professionals in fiscal year 2023.

Pathway expansion. HHS and selected jurisdictions implemented actions to broaden interest in and exposure to governmental public health employment, intended to help expand pathways into the public health workforce. By expanding these pathways, agencies and jurisdictions aim to address market competition for public health workers. For example, an internship or fellowship program may encourage students or recent graduates of public health-related degree programs to seek employment at public health departments. Similarly, partnering with educational institutions to expose students to public health may translate into greater interest in governmental public health careers, according to interviews and documents provided by agency and jurisdiction officials. Examples include:

· CDC, through six fellowship programs, placed 409 full-time fellows in jurisdictions in fiscal year 2023. These programs included the Epidemic Intelligence Service, Laboratory Leadership Service, Public Health Associates, Applied Epidemiology Fellows, Applied Public Health Informatics Fellows, and Preventive Medicine Residents and Fellows programs.

· HRSA’s Regional Public Health Training Centers Program seeks to expand the public health workforce by coordinating field placements for public health students. In addition to increasing the workforce, according to an evaluation of the program, placing these students in jurisdictions increased participants’ intent to work in such jurisdictions in the future.[60] Officials reported that the program trained 1,107 public health students across a 5-year period (academic years 2015-2020) and that 41.9 percent of the students were from underrepresented minority groups or from disadvantaged backgrounds.

· Officials with the Maryland Department of Health established a Public Health Workforce Internship Program to provide a paid opportunity for students to experience working in public health, and to help develop a pipeline of potential employees.

Funding flexibility. Officials in selected jurisdictions told us that the flexibility of CDC’s Public Health Infrastructure Grant helped to ease recruitment and retention challenges. This grant provides flexible funding and a longer-term grant period compared to other funding sources used by jurisdictions that are short-term and categorical, according to interviews. In 2022, this grant awarded $3 billion in funding for workforce to 107 state, local, and territorial health departments. The funding will be available to recipients until November 2027. Jurisdictions can use this funding to address multiple or crosscutting public health infrastructure needs, including staff salaries or training, without being limited to specific activities or occupations. The grant’s five-year length may also help jurisdictions hire and retain staff beyond typical, shorter-term grant periods.

Examples of how jurisdictions we interviewed have used the Public Health Infrastructure Grants include:

· Officials from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health and California Department of Public Health told us that Public Health Infrastructure Grant funding allowed them to hire staff appropriate for communities’ individual needs and workforce gaps.

· Officials from the Maine and California state public health departments noted that lengthier grant periods, such as the 5-year period of the Public Health Infrastructure Grant, helped them to obtain approval from the state for hiring permanent, rather than temporary, public health staff. In addition, according to officials, candidates are more likely to consider employment when the position is funded for more than a year or two.

Special resources for responding to disasters or public health emergencies. HHS agencies and selected jurisdictions also provided special resources to supplement the workforce for disasters or public health emergencies. These resources are aimed to address challenges, like market competition and slow hiring processes, that can be especially difficult and exacerbate an already stressed workforce during emergencies. Examples of special resources include the following:

· During a declared public health emergency, state or tribal governments may request the temporary reassignment of personnel in their respective public health departments or agencies whose positions are funded under Public Health Service Act (PHS Act) programs.[61] Each head of an HHS agency with programs funded under the PHS Act may authorize requests for temporary reassignment, with ASPR serving as an intermediary between requesting state and tribal governments and the authorizing HHS agency. During the COVID-19 pandemic, all 50 states requested temporary reassignment of PHS Act funded personnel, according to HHS officials.

· The National Disaster Medical System, established in 1984 and overseen by HHS’s ASPR, provides workforce support for patient care, patient movement, and fatality management during or after a disaster or public health emergency, according to agency documentation.[62]

· ASPR also oversees the Medical Reserve Corps, a national network of volunteers organized in local community-based groups to strengthen public health and improve local preparedness, response, and recovery capabilities, according to agency documentation. Volunteers provided support during the COVID-19 pandemic, and were, according to one study, especially useful to small public health departments.[63]

· Officials with the California Department of Public Health said that in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, California created a state Public Health Reserve Corp, which consists of trained teams that provide emergency response for state emergencies. Officials said they used the state’s Public Health Reserve Corp and staff reassignment during emergencies, to meet the need, for example for personnel skilled in epidemiology and information technology.

· Jurisdictional officials we interviewed emphasized the value of CDC staff who are placed to work directly in their jurisdictions’ public health departments during outbreaks and emerging threats. In particular, they cited CDC’s Career Epidemiology Field Officer network as helpful to address their workforce gaps related to epidemiology. CDC also provides workforce support to jurisdictions in other ways. For example, CDC placed 115 fellowship participants in jurisdictions to provide laboratory and other support during outbreaks and emergency events in the 2023 fiscal year.

The public health workforce encompasses numerous jurisdictions within the U.S., many of which face various persistent challenges in recruiting and retaining public health workers. However, the HHS and jurisdictional actions we have described, among others, have helped enable jurisdictions to deal with the challenges, and helped begin to address gaps in the public health workforce.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. HHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, as well as other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov. If your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7114 or DeniganmacauleyM@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Mary Denigan-Macauley

Director, Health Care

In addition to taking steps to address gaps within jurisdictions’ public health workforce, agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have identified and taken steps to address gaps within the department’s own public health workforce in a variety of ways. This appendix provides examples of agency efforts to identify and address workforce gaps in staff and skills, based on agency documentation and our interviews with HHS officials. We did not assess HHS’s workforce planning, or that of its component agencies.

In general, HHS agencies identified gaps by monitoring workforce data and surveying their employees to assess skill gaps. The agencies have taken various steps to address these gaps, for example, by using expedited hiring authorities, creating a new employee deployment program for emergencies, and developing training resources, among other efforts. According to HHS officials, these agency efforts are part of implementing HHS’s Human Capital Operating Plan, which includes a framework for HHS agencies to identify workforce staffing gaps and skill gaps and to address these gaps through targeted recruitment and retention activities.[64] Under this plan, the department provides resources for identifying workforce gaps and for conducting recruitment activities, with HHS’s Office of Human Resources working in coordination with HHS agencies’ human resource offices and other agency officials.

Examples of ASPR Efforts to Identify and Address Workforce Gaps

The Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) leads the nation’s medical and public health preparedness for, response to, and recovery from disasters and public health emergencies. ASPR became an operating division of HHS in 2022, and we previously reported on ways to strengthen the agency’s workforce planning.[65] In March 2024, ASPR awarded a contract to perform an agency-wide workforce assessment, which is expected to be completed before the end of fiscal year 2025. In addition, ASPR identified the need to recruit 38 additional staff in human resources during 2024 and 2025. Officials told us they have used a variety of social media in their recruitment activities, and they have sought to establish an awareness of ASPR as a positive place to work because of its mission, work-life balance, and the recognition and rewards provided to employees, among other things.

We also previously recommended actions to help ASPR ensure it has an adequate number of effectively trained emergency responders within the National Disaster Medical System.[66] ASPR identified a staffing gap in the system through a 2023 assessment of the National Disaster Medical System workforce.[67] In an effort to help address this gap, ASPR officials told us that they continued to use a direct hire authority to hire new intermittent employees. A direct hire authority allows federal agencies to fill positions for which the Office of Personnel Management has determined there is a critical hiring need or severe shortage of candidates without regard to certain rating, ranking, and veterans’ preference requirements.

In addition, ASPR officials told us that they have taken a range of steps to attract candidates to the National Disaster Medical System, including participation in networking and professional events, having teams conduct personal outreach, and using social media to highlight the program’s training and mission to a wider audience.

Examples of CDC Efforts to Identify and Address Workforce Gaps

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is responsible for protecting the public health of the nation through the prevention and control of diseases and other preventable conditions, and responding to public health emergencies. The agency identified gaps in certain occupations that it considers to be mission critical—essential for the success of CDC programs—and addressed some of these gaps using direct hire authorities, according to CDC officials. Examples of mission critical occupations identified by the agency include data science, information technology management, microbiology, chemistry, and mathematical statistics.

According to CDC officials, the agency addressed gaps in some of these occupations through direct hire authority for its Data Modernization Initiative, authorizing hiring of up to 596 positions. The agency also hired staff in these occupations through a government-wide direct hire authority for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics positions, according to our review of documentation. In addition to direct hire authorities, CDC officials indicated that the agency offers recruitment, retention, and relocation incentives and offers “above the minimum pay” to attract qualified talent, to the maximum extent possible.[68]

CDC officials also told us that the agency initiated the CDC Career Ready program in 2023 to conduct an agency-wide assessment of skills and potential skill gaps in its existing workforce and to organize career development and training. The program is overseen by a centralized governing board and is supported by training resources and support teams to facilitate workforce development across the agency.

Through the program, CDC identified specific gaps in the areas of emergency preparedness and response, data analysis and interpretation, and workforce development, among others. To address these gaps, CDC plans to provide training and professional development opportunities and ongoing skills assessment to existing CDC staff, officials told us. In addition, through the program, CDC has developed analytical tools that provide information about staffing levels and competencies to help CDC identify recruitment targets.

CDC officials said that the agency established the CDC Ready Responder program in 2022 to address gaps in its internal workforce that responds to public health emergencies, and to help ensure that the agency had appropriate, trained, and available staff needed during an emergency. Beginning in 2020, the agency gathered data on the type and number of positions needed during emergencies, and on the length of time its staff spent deployed in those positions during emergency responses to COVID-19 and other emergencies. Officials reported that only a core group of certain staff volunteered to be deployed, with many of them deployed multiple times, for different emergencies.

To expand the staff available for emergency response, CDC developed the CDC Ready Responder program as a more structured approach to preparing and deploying its workforce during emergencies, according to officials. One aim of the program is to provide education for CDC staff on what it means to serve during an emergency response at CDC, to ease the uncertainty potential responders in its workforce may have about joining such a response.

According to CDC officials, the program also includes expanded training, planning, and deployment procedures for positions including epidemiologists, laboratory workers, statisticians, health communicators, and emergency management staff. CDC staff who participate are enrolled into one or more cadres—groups of employees with specific knowledge, skills, and experience that can fill certain roles in an emergency response. As of April 2024, more than 2,500 CDC staff had enrolled in one or more of 15 cadres in the CDC Ready Responder program, representing about 20 percent of CDC’s civil servant and Commissioned Corps workforce.

Examples of HRSA Efforts to Identify and Address Workforce Gaps

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) is responsible for supporting health care in the nation’s highest-need communities. The agency has identified mission critical occupations based on difficulties it has faced in hiring and retention, according to officials. These mission critical occupations include public health analysts, nurses, information technology specialists, acquisitions staff, medical officers, health scientists, and human resource specialists.

HRSA officials stated that the agency has used direct hire authority for some mission critical occupations and has taken other steps to address workforce gaps. For example, the agency establishes hiring procedures that can be used jointly by multiple offices, such as joint scheduling of interviews with job candidates. To facilitate these procedures, the agency shares a recruitment calendar with key recruiting time frames across HRSA bureaus and offices. According to officials, this collaborative approach streamlines the recruitment process and yields efficiency gains by reducing the administrative burden on human resources staff, hiring managers, and applicants.

HRSA also attends virtual and in-person recruitment fairs targeting specific workforce groups, to improve their outreach to candidates, according to officials. In addition, officials told us that the agency has recruited graduates of the Peace Corps, who can be hired efficiently for jobs otherwise restricted to federal employees.[69]

Examples of IHS Efforts to Identify and Address Workforce Gaps

The Indian Health Service (IHS) funds and provides medical and public health services to American Indians and Alaska Natives, who are members or descendants of federally recognized Tribes. The agency has identified gaps in multiple occupational areas, including for example epidemiology, behavioral health, nursing, physician care, and laboratory science, according to agency officials. They said that efforts to attract staff in these occupations have included offering loan repayments, increased leave, and premium pay. IHS has also piloted efforts to provide housing subsidies and flexible work schedules.

IHS officials also said that the agency plans to complete a full assessment of public health needs. In addition, IHS established a National Public Health Council, which includes a subcommittee on epidemiology and workforce development, according to our review of documentation.

Examples of SAMHSA Efforts to Identify and Address Workforce Gaps

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) leads public health efforts to advance the behavioral health of the nation and to promote mental health, prevent substance misuse, and provide treatments and supports to foster recovery. The agency identified a gap in its workforce for grants disbursement and management after the agency received increased appropriations in 2022 to support grants, according to agency officials. SAMHSA applied for and received direct hire authority to hire up to 149 positions including public health advisors, grants management specialists, and social science analysts, according to our review of documentation. SAMHSA also used other strategies to fill critical positions, such as hiring staff through temporary 2-year appointments, according to officials.