CARIBBEAN FIREARMS

Agencies Have Anti-Trafficking Efforts in Place, But State Could Better Assess Activities

Report to Congressional Requesters

October 2024

GAO-25-107007

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107007. For more information, contact Chelsa Kenney at (202) 512-2964 or kenneyc@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107007, a report to congressional requesters

October 2024

CARIBBEAN FIREARMS

Agencies Have Anti-Trafficking Efforts in Place, but State Could Better Assess Activities

Why GAO Did This Study

Some Caribbean nations, such as Haiti, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago, have high rates of violence, including homicide. In 2021, Caribbean countries accounted for six of the world’s 10 highest national murder rates, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The United Nations and other organizations monitoring firearms trafficking have reported that a high percentage of the firearms used in these crimes have been trafficked from the U.S.

GAO was asked to report on U.S. efforts to counter firearms trafficking to Caribbean nations. This report examines (1) what data and reporting show about the trafficking and use of firearms in Caribbean countries; (2) U.S. agencies’ efforts to disrupt firearms trafficking in these countries; and (3) agency efforts to track results of key efforts to combat firearms trafficking from the U.S. to the Caribbean.

GAO reviewed federal firearms recovery and trace data, and other related U.S. agency data, analysis, and program information for fiscal years 2018 through 2022, the most recent available at the time of our review. GAO interviewed U.S. and Caribbean officials through in-person site visits in the Bahamas and Trinidad and Tobago, and through video conferences with Barbados, Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Jamaica. GAO selected these countries based on geographic diversity, the percentage of recovered firearms that were of U.S. origin, and U.S. agency efforts in country to combat firearms trafficking.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that State update the CBSI’s Results Framework to establish firearms trafficking specific indicators. State concurred.

What GAO Found

The majority of recovered firearms in the Caribbean were traced to the U.S. and trafficked through various means. The Department of Justice’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) traces the origin of firearms recovered in Caribbean countries at the request of Caribbean law enforcement agencies or ATF officials in the Caribbean. While the political will and capacity of each country impacts the number of recovered firearms each country submits for tracing, ATF processed 7,399 traces of firearms recovered in crimes in the Caribbean from 2018 through 2022 (see figure). GAO analysis of these data showed that 73 percent of these firearms, most of which were handguns, were sourced from the U.S. While Caribbean countries do not manufacture firearms, U.S. and foreign officials said that criminals in Caribbean countries can traffic firearms by air and sea using various concealment techniques and can obtain firearms through illegal markets.

|

Firearms origin |

Total |

Percentage |

|

U.S. origin |

5,399 |

73% |

|

Non-U.S. origin |

1,728 |

23% |

|

Undetermined origin |

272 |

4% |

|

Total firearms recovered and submitted for tracing = 7,399 |

||

Source: GAO analysis of Alcohol,

Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) data. | GAO‑25‑107007

To help disrupt and combat firearms trafficking, the Departments of State, Justice, Homeland Security (DHS), and Commerce have various capacity-building, investigative, and border security efforts in place. For instance, State, working through the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI)—a U.S. security partnership with 13 Caribbean countries—helps fund various trainings and capacity building programs, such as the Crime Gun Intelligence Unit. This unit collects and analyzes intelligence on guns and promotes intelligence sharing with regional international law enforcement partners. DHS’s Homeland Security Investigations, a law enforcement agency, established Transnational Criminal Investigative Units throughout the Caribbean and conducts various interagency operations to uncover criminal networks responsible for trafficking firearms. DHS’s Customs and Border Protection interdicts illicit firearms at U.S. ports of entry enroute to the Caribbean. From fiscal years 2018 through 2023, it conducted hundreds of domestic interdictions, seizing 535 firearms and 3,167 firearm components at U.S. ports destined for Caribbean countries.

U.S. agencies track results of their key efforts to combat firearms trafficking to the Caribbean through various means. However, State does not track results for combatting firearms for the CBSI. Specifically, State’s CBSI’s Results Framework includes intermediate results and indicators for each program objective but does not have specific indicators for its goal of reducing illicit firearms trafficking. Developing such indicators would better enable State to measure progress of its combating firearms trafficking efforts.

Abbreviations

|

AES |

Automated Export System |

|

ATF |

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives |

|

BIS |

Bureau of Industry and Security |

|

CARICOM |

The Caribbean Community |

|

IMPACS |

Implementation Agency for Crime and Security |

|

CBP |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

|

CBSI |

Caribbean Basin Security Initiative |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

HSI |

Homeland Security Investigations |

|

ICE |

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

|

INL |

Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs |

|

PM |

Bureau of Political-Military Affairs |

|

TCIU |

transnational criminal investigative unit |

|

TCO |

transnational criminal organization |

|

UN |

United Nations |

|

UNODC |

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime |

|

UNLIREC |

United Nations Regional Centre for Peace, Disarmament and Development in Latin America and the Caribbean |

|

WHA |

Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

October 15, 2024

Congressional Requesters

The average number of violent deaths in the Caribbean is nearly triple the global average, according to the Small Arms Survey. Firearms are used in more than half of all homicides throughout the Caribbean, and in 90 percent of homicides in some countries, according to a 2023 joint report by the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Implementation Agency for Crime and Security (IMPACS) and the Small Arms Survey, a global center studying small arms and armed violence.[1] In 2021, Caribbean countries accounted for six of the world’s 10 highest national murder rates, according to a report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).[2]

In 2022, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), within the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), reported observing a significant increase in the quantity, caliber, and type of firearms being illegally trafficked from the U.S. to the Caribbean. Further, the flow of illicit firearms into Haiti enables violent gangs and contributes to the displacement of people across the country, according to UNODC 2023 reporting.[3] The escalating gang-related violence in Haiti has heavily disrupted health operations, targeted health workers and facilities, and affected the supply of medicine, according to the Small Arms Survey. Immigration to the U.S. from Haiti has dramatically increased in recent years, caused in part by widespread gang violence, according to the Migration Policy Institute.[4]

The Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives’ (ATF) 2024 National Firearms Commerce and Trafficking Assessment determined that black-market guns sold by unlicensed dealers without a background check are increasingly being found at crime scenes and approximately 60 percent of the users of trafficked firearms in cases which ATF examined were convicted felons.[5] In June 2022, President Biden signed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act into law, which created federal criminal offenses for firearms trafficking and grants the government new authorities to prosecute these offenses.[6] In July 2023, DOJ appointed a Coordinator for Caribbean Firearms Prosecutions to elevate firearms trafficking investigations and prosecutions while also assisting in the implementation of the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act’s provisions. In June 2024, the DOJ reported that it had charged more than 500 defendants under these new provisions. U.S. officials have said that the coordinator position will deepen diplomatic engagement and collaboration on gun prosecutions with our Caribbean partners.

You asked us to review illegal firearms trafficking from the U.S. to the Caribbean.[7] This report examines (1) what data and reporting show about the trafficking and use of firearms in Caribbean countries, (2) the efforts of U.S. agencies to disrupt firearms trafficking in these countries, and (3) agency efforts to track results of key efforts to combat firearms trafficking from the U.S. to the Caribbean.

To address these objectives, we reviewed U.S. agency documents and interviewed officials from ATF, HSI, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and the Departments of State and Commerce, as well as officials of foreign government law enforcement and customs agencies. To examine what data and reporting show about the legal export, trafficking, and use of firearms to the Caribbean, we reviewed the most recent data available from federal agencies, which included ATF data on firearms recovered in Caribbean countries from 2018 through 2022, U.S. Census data on firearms exported from the United States from 2018 through 2023, and CBP data on firearms seized that were destined for Caribbean countries from fiscal years 2018 through 2022. We also interviewed U.S. and foreign law enforcement officials who were familiar with firearms trafficking issues in the Caribbean.

To examine efforts undertaken by U.S. agencies to disrupt firearms trafficking to the Caribbean, we reviewed U.S. agency documentation and interviewed officials at ATF, HSI, State, CBP, and Commerce. In addition, we sent a data request and followed-up with these five agencies regarding their key efforts to combat firearms trafficking in the Caribbean from 2018 through 2023. This data we gathered included information on, among other things, each effort, and its purpose, whether other agencies are participating, and how results of the effort are being tracked, including performance reporting.

To examine agency efforts to track results of key efforts to combat firearms trafficking from the U.S. to the Caribbean, we interviewed U.S. and Caribbean law enforcement and customs officials during in-person site visits conducted in the Bahamas and Trinidad and Tobago. We also conducted video conferences with similar U.S. and Caribbean officials in the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, and Barbados. We selected these countries based on geographic diversity, the percentage of recovered firearms that were of U.S. origin, and U.S. agency efforts in country to combat firearms trafficking. We also reviewed agency responses to our data request noted above, which included information on agency efforts to track results of key efforts to combat firearms trafficking. We also reviewed agency documents on related U.S. efforts and strategies, such as the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI) and Caribbean Firearms Initiative.[8]

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to October 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The countries of the Caribbean are diverse in size, culture, and level of development, and face various interrelated economic and security challenges (see fig. 1). According to a report by the Small Arms Survey, the Caribbean region suffers from homicide rates almost three times the world average, and the majority of these deaths involve the use of a firearm.[9] According to the same report, legal civilian firearm ownership is tightly regulated in the region, with licensing and registration data showing a regional average of 1.63 registered firearms per 100 residents—ratios that suggest CARICOM gun laws and regulations are highly restrictive by global standards.

The Small Arms Survey also reported that while firearms and ammunition are not manufactured in the countries that make up the CARICOM, their wide availability in the region has contributed to high levels of violence and generalized insecurity. The UNODC reported in 2023 that a key factor contributing to the disproportionately high rate of lethal violence in the Caribbean is access to and misuse of firearms.[10] In April 2023, the CARICOM heads of government declared crime and violence a public health issue, fueled by illegal firearms and organized criminal gangs in the Caribbean.

Transnational Criminal Organizations (TCOs) and other criminals operating in the Caribbean take advantage of the region’s weaknesses to further their unlawful activities, according to the White House National Drug Control Strategy Caribbean Border Counternarcotics Strategy. In addition to smuggling drugs into the United States, Europe, and other nations, these organizations traffic firearms and exploit weaknesses in the region’s financial regulatory framework to launder the revenues of their illegal activities.

According to the Small Arms Survey, the schemes used to smuggle firearms to the Caribbean require minimal knowledge, skill, or planning to execute. The trafficker needs to blend the merchandise in with the thousands of other shipments leaving and arriving from international ports daily.

Responsibilities of U.S. Agencies in Combatting Firearms Trafficking in the Caribbean

Combatting firearms trafficking to the Caribbean is a priority for several U.S. federal agencies, including State, ATF, HSI and CBP within DHS, and the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) within Commerce. These agencies work separately and jointly on efforts to combat firearms trafficking to the Caribbean.

State

State maintains U.S. bilateral relations with Caribbean countries and provides capacity-building assistance, including to address firearms trafficking. Several State bureaus carry out these functions, including the Bureaus of Western Hemisphere Affairs (WHA), International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL), and Political-Military Affairs (PM). These bureaus, along with the U.S. Agency for International Development, manage activities under the CBSI. In May 2010, the United States, CARICOM member states, and the Dominican Republic formally launched CBSI to strengthen regional cooperation on security. One of the CBSI’s aims is to reduce illicit trafficking by providing U.S. foreign assistance.

ATF

ATF investigates violations of federal firearms laws and regulations, including the diversion of firearms from legitimate commerce, and enforces these laws and regulations. Specifically, the ATF investigates domestic firearms trafficking, including instances of firearms theft and “straw purchases,” which refer to the illegal acquisition of firearms on behalf of other individuals. Additionally, the ATF conducts inspections of federal firearms license holders. ATF maintains three regional attachés in the Caribbean who work with foreign law enforcement on firearms issues.

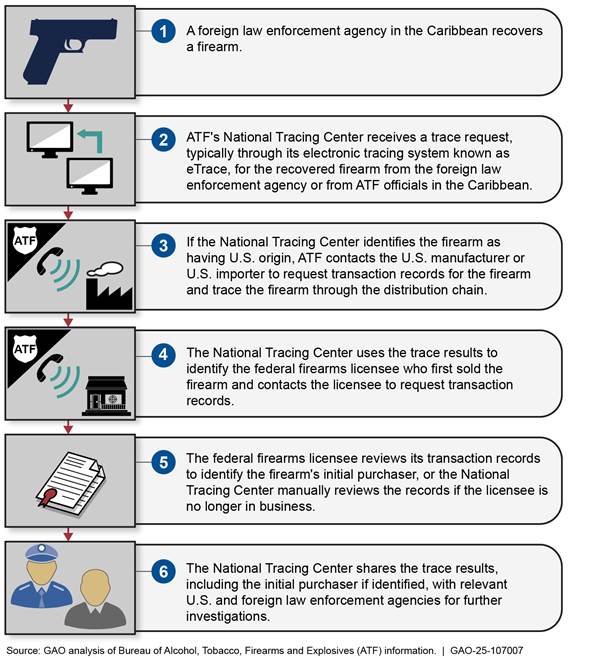

ATF also assists foreign law enforcement with tracing firearms recovered in the Caribbean. For example, ATF helps foreign agencies submit requests to ATF’s National Tracing Center to trace recovered firearms to initial purchasers. Figure 2 shows ATF’s tracing process.

HSI

HSI conducts export control investigations, including investigations of firearms smuggling from the U.S. to the Caribbean. HSI works with U.S. and foreign law enforcement to identify and prosecute traffickers and TCOs and to seize illegal firearms and other dangerous weapons.

HSI works with foreign law enforcement agencies through vetted transnational criminal investigative units (TCIU) in Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti. According to HSI, TCIUs include foreign law enforcement officials, customs officers, immigration officers, and prosecutors who receive HSI training and undergo rigorous background investigations to ensure joint investigative efforts are uncompromised. HSI has attachés in the Bahamas, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Jamaica.

BIS

In March 2020, BIS began conducting oversight of export licenses for most semiautomatic and nonautomatic firearms and related ammunition, parts, and components on the Commerce Control List.[11] According to BIS officials, this oversight includes small arms that are semi-automatic or non-automatic and 50 caliber or less. Export Enforcement serves as an investigative arm of BIS and enforces U.S. export laws regarding the illicit trafficking of firearms and ammunition. It also undertakes end-use checks around the world, such as pre-license checks and post-shipment verifications.[12] According to BIS, pre-license checks establish the legitimacy of involved parties and validate information on export license applications prior to shipment, while post-shipment verifications strengthen assurances that all parties comply with export requirements and monitor illicit diversion of exports after shipment.

Although BIS retains personnel in other countries to assist with end-use monitoring in a defined geographic region, none of them cover the Caribbean region. BIS deploys U.S.-based agents to countries without permanent coverage to perform end-use checks through its Sentinel program. Sentinel deploys agents to visit end users of commodities subject to Commerce jurisdiction and to determine whether these items are being used in accordance with the Export Administration Regulations.

CBP

CBP enforces U.S. customs and trade laws.[13] For example, CBP aims to detect, discourage, and disrupt transnational organized crime that affects national and economic security interests, both domestically and internationally. CBP has the authority to seize firearms, ammunition, explosives, narcotics, and currency that are illegally transported out of the United States. In this capacity, CBP’s Office of Field Operations conducts inspections of articles, including firearms, being transported into and from the United States. DHS’s Office of Inspector General reported that the Office of Field Operations’ total global outbound seizures from fiscal years 2018 to 2022 included 2,306 firearms.[14] CBP assists Caribbean customs and police agencies within host countries and has personnel stationed in the Caribbean with varying responsibilities.

The Majority of Recovered Firearms in the Caribbean Were Traced to the U.S. and Trafficked through Various Means

Available ATF data on firearms recovered in 25 Caribbean countries indicate that about 73 percent of firearms recovered and traced from calendar years 2018 through 2022 were sourced to the United States. The remainder were either traced to 35 other countries or their source was undetermined. U.S. and foreign officials told us that criminals in Caribbean countries can traffic firearms over porous borders by air and sea using various concealment techniques and can obtain firearms through illegal markets.

ATF Tracing Data Indicate Most Firearms Recovered in the Caribbean Came from the U.S., but Several Factors May Limit or Delay Submissions

ATF eTrace Data Indicate the Majority of Firearms Recovered in the Caribbean from 2018 to 2022 Came from the U.S.

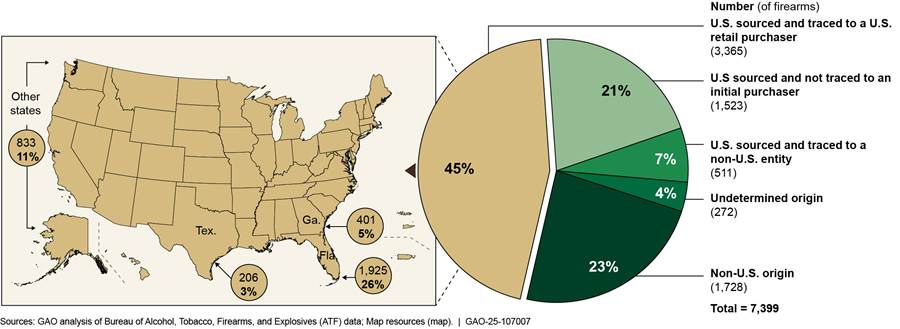

ATF’s eTrace tracing system, used to trace recovered firearms, provides the most reliable and informative data on sources of firearms recovered in the Caribbean, according to U.S. and Caribbean officials. Our analysis of ATF data on firearms recovered in 25 Caribbean countries indicate that about 73 percent of firearms (5,399 out of 7,399) recovered and traced by ATF’s eTrace system in 2018 through 2022 were identified as being sourced from the United States (that is, had been manufactured in or imported into the United States).[15] The remaining 27 percent of recovered and traced firearms were either traced to 35 other countries (23 percent) or their source was of undetermined origin (4 percent).

U.S. sourced firearms fall into three primary categories:

1. U.S. sourced and traced to a U.S. retail purchaser: the firearm is sold by a U.S. federal firearms licensee to an initial purchaser in the United States. This category accounted for 45 percent of the firearms (3,365 out of 7,399) recovered and traced in the Caribbean, according to ATF data we analyzed. Of these 3,365 firearms recovered in the Caribbean that were traced to a U.S. retail purchaser, the majority originated in Florida, Georgia, and Texas.

2. U.S. sourced and traced to a non-U.S. entity: the firearm is transferred from a U.S. federal firearms licensee to a foreign government, law enforcement agency, dealer, or other foreign entity. This category accounted for 7 percent of the firearms recovered and traced in the Caribbean.

3. U.S. sourced and not traced to an initial purchaser: the firearm is known to be U.S. sourced, but ATF could not trace the firearm to the individual who initially purchased it. This category accounted for 21 percent of the firearms recovered and traced in the Caribbean (see fig. 3.)

Note: According to ATF data, no firearms submitted for tracing in the Caribbean were traced to an initial retail purchaser in Wyoming or Vermont. Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands were the only U.S. territories to which an initial retail purchaser was traced.

|

Definitions 1. U.S. sourced and traced to a U.S. retail purchaser: Firearms that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) determined were manufactured in, or imported into the U.S., and were sold by a U.S. federal firearms licensee to a purchaser in the U.S. 2. U.S. sourced and traced to a non-U.S. entity: Firearms that ATF determined were transferred from a U.S. federal firearms licensee to a foreign government, law enforcement agency, dealer, or other foreign entity. 3. U.S. sourced and not traced to an initial purchaser: Firearms that ATF determined were manufactured in, or imported into the U.S., but for which ATF was unable to determine the initial purchaser. 4. Non-U.S. origin: Firearms that ATF determined were manufactured in other countries and not imported to the U.S. or whose importer was not shown on the trace request. 5. Undetermined origin: Firearms for which ATF was unable to identify the manufacturer. Source: GAO analysis of ATF information. | GAO‑25‑107007 |

Our analysis of ATF data also showed that approximately 7 percent of the firearms (511 out of 7,399) recovered and traced in the Caribbean were determined to be U.S. sourced and traced to a non-U.S. entity, meaning they were transferred from a U.S. federal firearms licensee to a foreign government, law enforcement agency, dealer, or other foreign entity (see fig. 3). The recovery of legally exported firearms is an indicator that those firearms may have been diverted for illicit use. For more information regarding legal firearm exports from the U.S. to the Caribbean, see appendix II.

Our analysis of ATF data also showed that 21 percent of the firearms (1,523 out of 7,399) recovered and traced in the Caribbean were determined to be U.S. sourced and not traced to an initial purchaser. This means that ATF determined the firearm was manufactured in, or imported into the United States, but was unable to determine the initial purchaser for the following reasons:

· Data supplied by the law enforcement agency requesting the trace were missing or invalid (such as the firearm model, serial number, or importer)—768 of the 1,523 U.S.-sourced firearms.

· Federal firearms licensee records were incomplete, missing, or illegible—333 of the 1,523 U.S.-sourced firearms.

· Firearms were manufactured before the Gun Control Act of 1968 established marking and record-keeping requirements—107 of the 1,523 U.S.-sourced firearms.

· Other reasons, for example, the firearm was linked to the military, had an eTrace request being processed, or was reported lost or stolen—315 of the 1,523 U.S.-sourced firearms.

Twenty-seven percent of the firearms (2,000 of 7,399) recovered and traced in the Caribbean in 2018 through 2022 were identified as non-U.S. origin or were of undetermined origin, according to ATF data we analyzed.[16] The majority of these firearms (1,728 of 2,000) were traced to non-U.S. manufacturers in 35 other countries, including Brazil, Austria, Italy, and Germany. Some of these firearms were manufactured in countries that were dissolved in the 1990s, such as Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Union, which suggests the firearms are decades old. The remaining 4 percent of the firearms (272) were of undetermined origin.

Table 1 shows that the source of the firearms recovered and traced varied among the 25 Caribbean countries in our scope. According to ATF, Suriname did not recover and trace any firearms for the years of our review. For example, the Bahamas had the highest percentage of recovered and traced firearms identified as being U.S.-sourced and traced to U.S. retail purchasers (85 percent) and Trinidad and Tobago had the smallest percentage (23 percent).

|

|

U.S. Sourced and traced to a U.S. retail purchaser |

U.S. sourced and traced to a non-U.S. entity |

U.S. sourced and not traced to an initial purchaser |

Non-U.S. |

Undetermined origin |

|

Anguilla |

59 |

0 |

22 |

11 |

7 |

|

Antigua and Barbuda |

43 |

9 |

36 |

11 |

0 |

|

Aruba |

33 |

0 |

33 |

33 |

0 |

|

Bahamas, The |

85 |

2 |

11 |

1 |

0 |

|

Barbados |

80 |

0 |

12 |

7 |

0 |

|

Bermuda |

58 |

0 |

25 |

17 |

0 |

|

British Virgin Islands |

78 |

0 |

18 |

4 |

0 |

|

Cayman Islands |

56 |

4 |

15 |

26 |

0 |

|

Curacao |

16 |

19 |

34 |

31 |

0 |

|

Dominica |

53 |

0 |

43 |

5 |

0 |

|

Dominican Republic |

34 |

7 |

16 |

39 |

4 |

|

Grenada |

70 |

4 |

19 |

7 |

0 |

|

Guadeloupe |

73 |

0 |

9 |

18 |

0 |

|

Guyana |

55 |

7 |

18 |

14 |

7 |

|

Haiti |

71 |

4 |

14 |

10 |

1 |

|

Jamaica |

36 |

10 |

24 |

29 |

0 |

|

Martinique |

43 |

5 |

16 |

36 |

0 |

|

Montserrat |

71 |

0 |

29 |

0 |

0 |

|

Saint Kitts and Nevis |

64 |

0 |

15 |

19 |

2 |

|

Saint Lucia |

45 |

5 |

21 |

29 |

0 |

|

Saint Martin |

55 |

7 |

12 |

24 |

3 |

|

Sint Maarten |

60 |

0 |

40 |

0 |

0 |

|

Saint Vincent & The Grenadines |

94 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

|

Trinidad and Tobago |

23 |

8 |

26 |

31 |

12 |

|

Turks and Caicos Islands |

44 |

2 |

25 |

15 |

15 |

Source: GAO analysis of Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) data. | GAO‑25‑107007

Notes: Percentages might not total to 100 due to rounding. Suriname did not recover and trace any firearms for the years of our review.

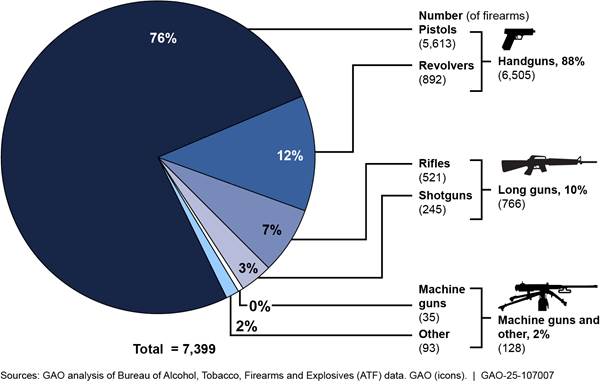

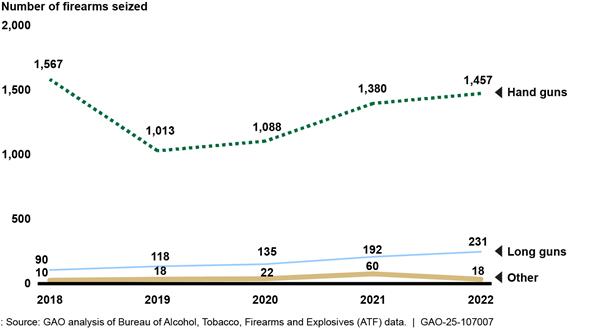

Our analysis of ATF data show that 88 percent of recovered and traced firearms in the 25 Caribbean countries we reviewed were pistols or revolvers, otherwise known as handguns. These data also show that rifles and shotguns, otherwise known as long guns, account for 10 percent of recovered and traced firearms in the Caribbean. Machine guns and other guns account for 2 percent of recovered and traced firearms in the region (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Types of Firearms Recovered in the Caribbean and Traced by U.S. Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, 2018-2022

Our analysis of ATF data shows a growing number of long guns submitted for tracing in the Caribbean from 2018 through 2022 (see fig. 5). For instance, in 2022, long guns accounted for 14 percent of firearms recovered and traced for the 25 Caribbean countries we reviewed, which is up from 5 percent in 2018. In Trinidad and Tobago, long guns accounted for 25 percent of firearms recovered and traced in 2022 and 8 percent in 2018. Of the firearms recovered and traced in Haiti from 2018 through 2022, long guns accounted for 34 percent, which is a greater percentage than all other Caribbean countries. U.S. and Caribbean law enforcement officials we met with also told us they are seeing an increase in the use of long guns in the Caribbean. A State INL official we met with in Barbados told us that the bureau is seeing more high-powered, AK-47 type weapons throughout the region. In addition, a law enforcement official we met with in Trinidad and Tobago told us that police are collecting a greater diversity of types and calibers of bullet casings at crime scenes, indicative of the increasing lethality of the firearms entering the country.

Figure 5: Types of Firearms Recovered in the Caribbean and Traced by U.S. Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, 2018-2022

ATF was able to determine the amount of time between the first retail sale of a firearm and its recovery in a crime—known as “time-to-crime”—for 45 percent (3,345 of the 7,399) of firearms recovered and traced from 2018 through 2022. Of these 3,345 firearms, data indicated that 717, or around 21 percent, were purchased less than 1 year prior to the firearm being recovered in a crime. According to an ATF official, time-to-crime periods of less than 1 year are indicative of illegal trafficking, or that the firearm was initially acquired through a straw purchase. ATF prioritizes cases with time-to-crime of less than 1 year and refers case related information to other U.S. agencies involved investigating straw purchases, including HSI, CBP, and BIS. According to ATF, this information provides crucial intelligence to investigators.

U.S. and Caribbean law enforcement officials said they have seen a rise in privately manufactured firearms[17] and component parts. Law enforcement officials also told us that 3-D printers and their ability to print firearms parts may have contributed to this increase. In August 2023, law enforcement officials uncovered and suspended the operations of a 3-D printing lab that had been used to produce firearms, according to one ATF official in Trinidad and Tobago. According to ATF, investigating crimes that involve privately manufactured firearms that do not have unique serial numbers create difficulty in tracing origins of these firearms and linking them to related crimes.

Caribbean Countries Use of ATF’s eTrace May Be Limited or Delayed by Several Factors

All 25 Caribbean countries we reviewed submitted trace requests to ATF for firearms recovered from 2018 through 2022. ATF officials told us that not all firearms recovered and submitted to eTrace can be completed since the filings may contain incomplete or erroneous information. Table 2 shows the number of recovered and traced firearms for the Caribbean countries we reviewed.

|

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

Total |

|

Anguilla |

6 |

10 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

27 |

|

Antigua and Barbuda |

5 |

3 |

7 |

8 |

21 |

44 |

|

Aruba |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

Bahamas, The |

192 |

247 |

209 |

238 |

331 |

1,217 |

|

Barbados |

33 |

48 |

31 |

28 |

84 |

224 |

|

Bermuda |

5 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

12 |

|

British Virgin Islands |

4 |

1 |

9 |

18 |

18 |

50 |

|

Cayman Islands |

3 |

4 |

6 |

3 |

11 |

27 |

|

Curacao |

82 |

20 |

4 |

13 |

3 |

122 |

|

Dominica |

0 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

65 |

80 |

|

Dominican Republic |

606 |

59 |

76 |

109 |

134 |

984 |

|

Grenada |

6 |

3 |

4 |

7 |

7 |

27 |

|

Guadeloupe |

0 |

1 |

1 |

13 |

7 |

22 |

|

Guyana |

6 |

6 |

2 |

9 |

21 |

44 |

|

Haiti |

2 |

51 |

81 |

125 |

46 |

305 |

|

Jamaica |

375 |

354 |

472 |

576 |

473 |

2,250 |

|

Martinique |

0 |

0 |

10 |

33 |

13 |

56 |

|

Montserrat |

5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

|

Saint Kitts and Nevis |

24 |

18 |

2 |

7 |

8 |

59 |

|

Saint Lucia |

2 |

22 |

2 |

1 |

11 |

38 |

|

Sint Maarten |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

|

Saint Martin |

15 |

23 |

12 |

17 |

9 |

76 |

|

Saint Vincent & The Grenadines |

0 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

11 |

16 |

|

Trinidad and Tobago |

296 |

229 |

298 |

391 |

389 |

1,603 |

|

Turks and Caicos Islands |

0 |

47 |

2 |

14 |

38 |

101 |

|

Total |

1,667 |

1,149 |

1,245 |

1,632 |

1,706 |

7,399 |

Source: GAO analysis of Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) data. | GAO‑25‑107007

Note: Suriname did not recover and trace any firearms for the years of our review.

ATF officials told us they are unable to estimate the scope of firearms recovered in the Caribbean that were not filed in eTrace. ATF indicated that its eTrace goal is for 100 percent comprehensive tracing of recovered firearms. However, not all firearms recovered in the Caribbean are reported or filed in eTrace by Caribbean law enforcement officials for various reasons. Thus, no reliable means exist to assess the percentage of recovered firearms that have been traced. Several factors may limit or delay firearm submissions to eTrace:

· Political Will. Some Caribbean countries have a greater willingness than others to recover and trace firearms, according to one ATF official. ATF’s eTrace data only reflects what is inputted into the system by country representatives, which, among other factors, can be impacted by the country’s political willingness to do so, according to an ATF regional representative.

· Capacity. U.S. and Caribbean officials told us that some Caribbean countries do not have the human and technological capacity to effectively search, seize, process, and trace firearms in a timely manner. For example, U.S. officials told us that Jamaica does not have the manpower and equipment to properly scan the large number of shipments entering the country. ATF officials told us that Suriname has not been tracing recovered firearms, as officials who knew how to use eTrace are no longer working in their positions. ATF officials told us they plan to travel to Suriname and other countries to train individuals on eTrace. In Haiti, the security environment and gang violence pose a threatening environment for individuals that recover and trace firearms, impacting their willingness and capacity for tracing recovered firearms, according to U.S. officials. In addition, most Caribbean governments do not have reliable data systems, which are often paper-based, to track firearms, according to U.S. and Caribbean officials. For example, Jamaican officials said that their firearms records are paper-based and not centralized, making them less accessible and difficult to analyze. Paper-based systems are also vulnerable to loss and accidental destruction due to fire or water damage.

· Interagency Communication. U.S. officials we met with told us that the many foreign government entities involved in seizing firearms, such as customs and law enforcement agencies, have poor interagency communication and trust and often do not coordinate with each other in country. For example, the Cayman Islands law enforcement regularly traces recovered firearms, but some customs officials in country do not share information on the firearms they recover with the police and those weapons go untraced, according to ATF an official.

· Language Barriers. ATF officials told us that, as of 2023, Haitian law enforcement has access to eTrace but does not submit trace requests because eTrace is not available in French or Creole. U.S. officials submit trace requests on behalf of Haitian law enforcement but noted challenges with coordination with Haitian counterparts.

Firearms Are Trafficked from the U.S. to the Caribbean by Air and Sea Using Various Concealment Techniques

Illicit firearms are trafficked into Caribbean countries by air and sea through a variety of methods and concealment techniques, according to U.S. and Caribbean officials. Officials further said that firearms are illicitly trafficked to Caribbean countries most commonly through shipping transport and can be concealed in large items, such as automobiles and televisions, or broken into components and hidden in household items, such as bags of rice or cereal boxes, and packaged in breakbulk cargo.[18] See figure 6 for examples of firearms being concealed among general cargo within a maritime shipping container. For example, officials in Jamaica said that firearms originating from the U.S. can arrive from cargo shipments, commercial air shipments, or through personal luggage.

Officials told us that traffickers enter Caribbean countries at unofficial ports without being inspected and use several methods and techniques for trafficking firearms. These include:

· Go-fast boats. Trafficking to unofficial ports is often by way of “go-fast boats,” which are designed to go faster than traditional speedboats. U.S. officials told us that traffickers will toss firearms overboard to evade being caught by law enforcement.

· Commercial airlines. Traffickers may pack firearms into personal luggage and transport them on commercial airlines.

· Commercial shipping. Firearms and firearms parts are smuggled in parcels using commercial shipping services, according to U.S. and Caribbean officials.

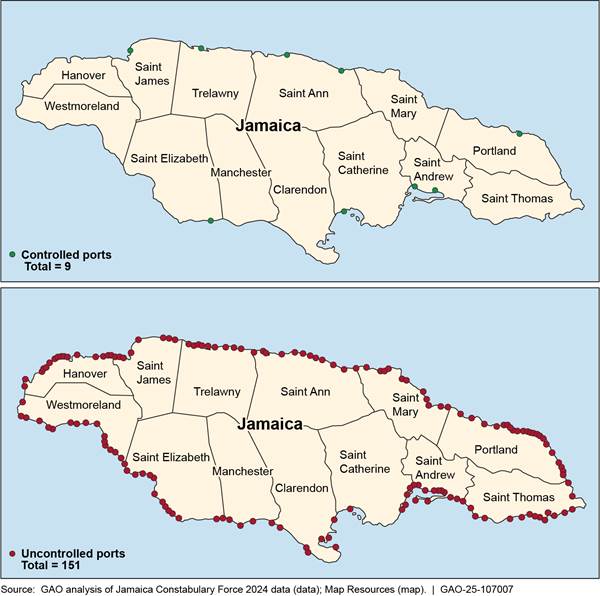

For example, law enforcement officials in Jamaica told us nine ports in Jamaica are government controlled, compared to 151 which are uncontrolled. Figure 7 shows Jamaica’s controlled and uncontrolled ports.

Agency officials said firearms traffickers will conceal firearms in a legal export shipment and will misrepresent the shipment’s value, such as claiming the total value is less than $2,500, to avoid having to electronically file the shipment with the government’s Automated Export System (AES) and evade U.S. government oversight.[19]

U.S. and Caribbean law enforcement officials said their experience shows that many firearms enter countries illicitly and are then sold within them through local illicit markets. Dual nationals from Caribbean countries who live in the U.S. can purchase or facilitate the purchase of firearms and ship them to their home countries as they have extensive contacts in both the U.S. and the destination Caribbean country. While many dual nationals facilitate illegal firearms trafficking, U.S. and Caribbean officials told us that Caribbean gangs and international criminal networks drive the trafficking, which itself is driven by the lucrative business of illicit firearm sales. According to these officials, firearms are available for illegal purchase in illicit markets and resold for higher prices. For example, Bahamian officials told us that a firearm retailing for $350 in the U.S. can be resold illegally in the Bahamas for $1,600.

An ATF official told us that laws for the inspection of inbound shipments vary, and most Caribbean countries do not conduct such inspections to the same extent as the United States. In Trinidad and Tobago, customs laws do not permit customs officials to open suspect packages without the recipient present, according to an ATF official. In addition, U.S. and Caribbean officials told us that corruption within Caribbean government agencies significantly hinders efforts to combat firearms trafficking. For instance, firearms traffickers bribe customs officials to ensure their shipments containing firearms or firearms parts go uninspected, resulting in fewer firearms seizures, according to U.S. and Caribbean officials.

Caribbean firearms importers will also take advantage of corrupt Caribbean customs officials to acquire more firearms than their export permit allows, according to an ATF official. For example, if a firearm export permit allows for 500 firearms to be imported over a certain timeframe, and one shipment includes 200 firearms, Caribbean customs officials are supposed to adjust the export permit to reflect that only 300 more firearms can still be imported. However, sometimes traffickers will bribe Caribbean customs officials to not adjust the permit, enabling traffickers to import more firearms than are allowed under the export permit, according to an ATF official.

U.S. and Caribbean officials also noted that Jamaica and Haiti have a history of bartering firearms for other products. For instance, Haitians and Jamaicans have traded firearms for cannabis, colloquially known as “Guns for Ganga.” Recently, some Haitians have also been known to trade firearms for food, according to a Jamaican law enforcement official.

U.S. officials said that some Caribbean countries have programs that allow individual households to import one duty-free barrel of goods from the U.S. per year. This duty-free barrel program takes place during the late December holiday season. U.S. officials told us that individuals in some instances have concealed firearms within these barrels. ATF told us that it provided gun sniffing dogs to help combat the illicit flows of firearms through this program and had success uncovering firearms. ATF officials told us that they do not plan to continue providing such assistance due to high costs, and since port conditions in country are not safe enough for these operations. According to State officials, in advance of the 2023 holiday season, U.S. agencies increased resources to screen outbound cargo from the United States to the Caribbean via freight forwarders at the Miami River to combat firearms trafficking from the duty-free barrel program.

U.S. Agencies Combat Firearms Trafficking in the Caribbean through Capacity Building, Investigations, and Information Sharing

State, ATF, BIS, CBP, and ICE each conduct efforts related to disrupting firearms trafficking to Caribbean destinations. State provides U.S. security assistance to projects aimed at building regional capacity to disrupt illicit firearms trafficking. State leads or participates in a variety of diplomatic engagement efforts aimed at addressing firearms trafficking. ATF, BIS, CBP, and HSI engage in counter-trafficking activities, such as investigations and information sharing, that contribute to disrupting firearms trafficking.

State Supports Regional and Country-Specific Capacity Building Efforts to Combat Firearm Trafficking

State Supports Regional Capacity Building Partnerships

The CBSI, a U.S. security cooperation partnership with 13 Caribbean countries, works to stem the flow of illegal activities as one of its main objectives. Under the auspices of the CBSI, State has worked with Caribbean experts and CARICOM governments to identify a list of short-term and long-term efforts to address firearms trafficking in the region. In May 2019, the CARICOM heads of government formally adopted these as the Caribbean firearms trafficking priority actions. To address these priority actions, State supports three primary efforts, described below, to develop the capacity of the Caribbean governments to disrupt firearms trafficking and reduce firearm violence.

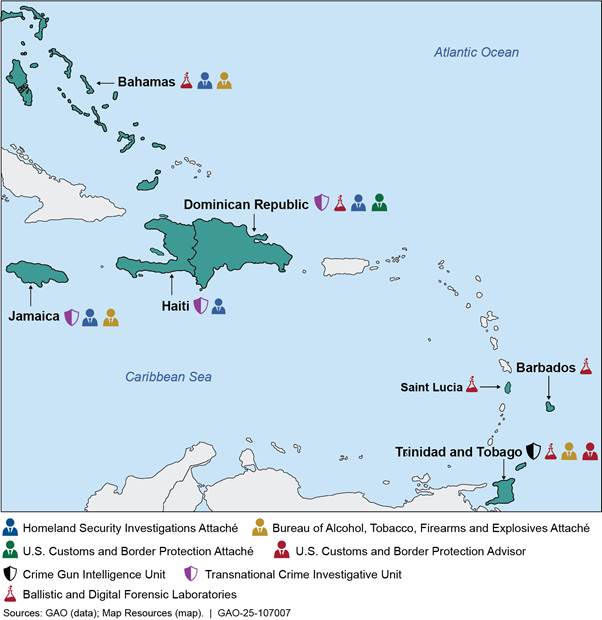

· Crime Gun Intelligence Unit (CGIU). State partnered with CARICOM IMPACS, as well as other U.S. agencies, to establish the CGIU in Trinidad and Tobago, which was inaugurated in November 2022 (see fig. 8). The CGIU is an interagency unit focused on real-time collection, management, and analysis of crime gun intelligence. Its goals are to identify bad actors, provide intelligence on seizures, and develop actionable firearms investigative leads through information sharing among Caribbean and U.S. law enforcement agencies. CGIU serves as a regional conduit of information sharing and seeks to increase cooperation between U.S. partners and Caribbean governments. State provided $1 million in funding assistance to start up the CGIU in 2023 and plans to provide an additional $1.2 million this year to continue support.

· Combatting illicit firearms and ammunition trafficking in the Caribbean. State partnered with the UN Regional Centre for Peace, Disarmament and Development in Latin America and the Caribbean (UNLIREC) on a program that provides training, technical assistance, policy guidance, and basic equipment so that partner countries are better able to collect and analyze ballistic evidence in the investigation of a crime and to more effectively present evidence in a court of law. State provided about $2.4 million for this program, which began in 2020. According to State, under this program half of the nations in the Caribbean have completed National Action Plans to govern their ability to manage their own stockpile of weapons, thus lowering the quantity of firearms available for trafficking in the area.

· Caribbean customs small arms, light weapons, and narcotics enforcement. State partnered with the World Customs Organization in January 2022 to train customs officials on their role in security. State is providing about $1.5 million in funding for this project—called Project Bolt—through the end of 2025. Project Bolt supports capacity building activities, such as assessing customs enforcement and security procedures and facilities in five countries, training on effective detection and prosecution of narcotics and weapons detection and trafficking, and by follow-up mentoring. The project has conducted such assessments in Trinidad and Tobago, Antigua and Barbuda, Jamaica, Guyana, and Suriname.

In addition to these efforts, State conducts diplomatic engagement with Caribbean nations on efforts to combat firearms trafficking through a variety of meetings and working groups. These include multilateral coordination meetings with the UN and CARICOM on the development of the Caribbean Firearms Priority Actions and the UN sponsored Caribbean Firearms Roadmap.

State also provides funding to enhance operational effectiveness, such as through the support of ballistic and digital forensics laboratories to track criminal networks online and conduct ballistic analyses. These laboratories are in Barbados, the Bahamas, Dominican Republic, Saint Lucia, and Trinidad and Tobago (see fig. 8).

Figure 8: Examples of U.S Activities and Efforts in Selected Countries to Combat Firearms Trafficking in the Caribbean

State Supports Country-Specific Efforts

State officials told us that, individual country missions work with their respective partner nations to develop and implement programs to address understand partners’ concerns about firearms trafficking. For example:

· A State official in Jamaica noted that coordination with local customs agencies could be improved. In part to address this concern, State is working with the Jamaican government to try to establish a Customs Mutual Assistance Agreement. According to a State official, such an agreement would allow for the sharing of import and export data from the Jamaican customs agency, which would aid HSI in tracking leads and preventing firearms from entering the country.

· In Trinidad and Tobago, State helped to establish and fund a canine breeding program. Canine units are used in Trinidad and Tobago’s Police Service, Prison Service, and Customs and Excise Division, and have been responsible for multiple seizures of narcotics and firearms, according to State officials.

ATF, ICE, BIS, and CBP Support Investigative, Information Sharing, and Enforcement Efforts to Disrupt Firearms Trafficking to the Caribbean

ATF Assists Caribbean Partners with Firearms Investigations and Conducts Related Domestic Investigations

ATF provides foreign law enforcement agencies with access to eTrace, firearms related training, and facilitates information sharing between Caribbean countries. In addition, ATF conducts domestic firearms investigations connected to the Caribbean. ATF has attachés to assist in this work stationed in the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago (see fig. 8).

· Firearms tracing, training, and information sharing: ATF provides law enforcement entities in the Caribbean with access to and training for eTrace. Collaborating with CBSI, CARICOM governments adopted as a priority action a commitment to trace all recovered firearms, using eTrace, to identify intelligence leads, trafficking routes, and traffickers for prosecution in accordance with domestic law. ATF has implemented the use of eTrace with Caribbean partners, except for Haiti, where the deteriorating security and political situations and the lack of an eTrace platform in French or Creole has prevented its full implementation.

ATF has trained enforcement personnel throughout the region in the identification of firearms, the tracing of firearms, and the trafficking of small arms. For example, an official from CARICOM IMPACS said that, in collaboration with ATF, they planned to go to Saint Lucia to provide eTrace training so that local law enforcement could conduct traces on firearms that had been recovered but not traced. That official also said that examining ATF data is the first step in investigations where guns are seized or found, further noting that having ATF tracing data available is critical to such investigations .

ATF officials told us the training plays a vital role in promoting and teaching firearms anti-trafficking techniques. It includes a variety of strategies, such as firearms identification, ballistic imaging value, case studies, undercover practices, trafficking trends, and other best practices. The training also facilitates dialogue between representative countries, strengthening the bonds between those countries so they can work together directly.

ATF attachés provide support for information sharing and coordinating investigations related to firearms trafficking with other U.S. agencies and Caribbean partners. One U.S. official noted that the establishment of the CGIU has helped increase awareness of the benefits of using eTrace and the importance of information sharing regionally. ATF officials also participate in host country multiagency task forces that support information sharing, such as the Anti-Gang and Firearms Task Force in the Bahamas.

ATF funding also supports activities such as trainings for law enforcement. For example, in fiscal year 2023, ATF’s Bahamas Country Office trained 156 students cross the region, according to ATF.

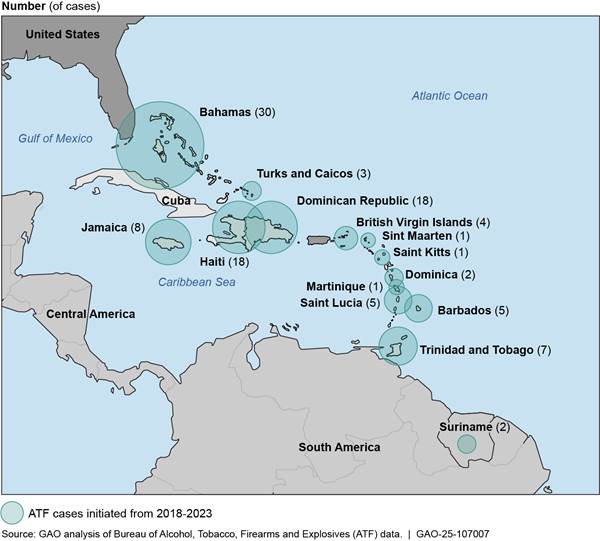

· Domestic Investigations: ATF attachés develop investigative leads for their U.S. counterparts to develop cases for prosecution in the United States. According to ATF officials, from 2018 through 2023, 105 cases related to at least one Caribbean country were referred to a domestic office for investigation, and 109 cases were initiated by the ATF (see fig 9).[20] Additionally, ATF officials can designate for inclusion firearms trafficking investigations for ATF’s Monitored Case Program, which provides additional headquarters oversight of, and support for, investigations that have the potential to pose significant risk to public. According to ATF officials, this program has supported and advanced cases that otherwise may have languished during the prosecution phase or encountered an investigative challenge.

HSI Investigates Firearms Related Crimes

As part of its Caribbean Firearms Initiative,[21] HSI investigates transnational crime with linkages to the U.S. by cooperating with TCIUs, leading various operations, and conducting international controlled deliveries in the Caribbean, as described below.

· TCIUs. TCIUs collaborate with HSI to investigate and prosecute individuals involved in transnational criminal activity. These units are composed of foreign law enforcement officials who have been trained and vetted.[22] HSI works with host nation partners to identify unknown networks and facilitators involved in U.S.-origin firearms smuggling and its associated violence, among other criminal activities. HSI has established TCIUs in Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, and most recently in Haiti (see fig 8). According to an HSI official in Haiti, the TCIU in Haiti has been delayed in becoming fully operational due to the current security environment. He noted the unit did not yet have a secure facility to house itself, which meant that members of the TCIU were stationed in different locations, making communication difficult. Once the TCIU facility is established the unit is expected to be able to conduct more activities such as direct investigations.

· Operations. HSI participates in interagency operations, which often include collaboration with other agencies such as ATF and CBP. For example, Operation Hammerhead is an interagency and international counter-firearms trafficking effort, which includes 12 CARICOM nations, that entails sharing information and surging resources to identify, investigate, and interdict suspicious shipments from the U.S. to the Caribbean. Launched in September 2023, the operation was designed to better understand Caribbean imports by using shared data on such imports to identify those that have originated from or passed through the United States. The operation aims to bolster resources in some key areas, including: (1) initiate and support HSI and CARICOM member state investigations into firearms trafficking; (2) refer for inspection any high-risk exports to CARICOM member states; and (3) refer suspicious, vulnerable, or otherwise high-risk U.S.-based exporters to HSI and CBP for investigation or inspection. The operation is in progress and, according to U.S. officials, has resulted in improved communication between U.S. agencies and Caribbean authorities.

· International controlled deliveries. HSI also conducts international controlled deliveries, in which it allows a shipment known to contain an illicit firearm to proceed to its intended recipient, with the intent of bringing the involved parties to justice. According to HSI, before allowing the shipment to proceed, firearms within the shipment are often broken down into components or otherwise modified, rendering them inoperable. HSI also noted all international movement of firearms or firearms components for international controlled deliveries are conducted between participating domestic and international law enforcement agencies and closely monitored for security and criminal prosecution or evidentiary purposes. An HSI official told us that international controlled deliveries are used to identify networks and develop leads both domestically and internationally. Not all Caribbean countries permit this type of activity, but, according to HSI officials, the CGIU is trying to help implement such deliveries in countries where laws permit. In Haiti, HSI officials noted that they are unable to conduct such deliveries because of the lack of stability in the current environment. HSI officials said they have participated with local law enforcement in such controlled shipments in the Bahamas and the Dominican Republic. According to a U.S. official we spoke with, Jamaica recently passed a law allowing International Controlled Deliveries and HSI informed us that it plans to provide the necessary training in these efforts to local law enforcement agencies.

BIS Oversees Export Licenses and Conducts End-use Monitoring

Since March 2020, BIS has been responsible for deciding whether to authorize export licenses of most semiautomatic and nonautomatic firearms, including to the Caribbean, and for conducting any applicable end-use monitoring. An interim final rule effective May 30, 2024, amends the Export Administration Regulations to reduce the general validity period from 4 years to 1 year for all future licenses involving firearms and related items.[23] The interim rule noted some concerns were raised that certain license exceptions may have been used to legally bring to these countries firearms which were subsequently diverted to unauthorized end users. The interim final rule also amends the Export Administration Regulations to limit the eligibility of firearms and related items to be exported to Caribbean countries under a license exception.

The interim final rule reported “high-risk destinations” for firearm exports.[24] State collaborated with BIS, leveraging expertise in foreign policy and relevant subject areas to develop guidance related to identifying “high-risk destinations.”[25] CARICOM destinations receiving the high-risk designation include the Bahamas, Belize, Dominican Republic, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. As such, all license applications seeking to export or reexport firearms and related items to non-government end users in these CARICOM destinations will be subject to a presumption of denial. [26] On July 1, 2024, BIS announced in the interim rule that existing licenses for the export and reexport of firearms and related items to non-government end users in high-risk destinations were revoked. In the interim rule, BIS also announced the modification of certain other valid licenses with validity periods longer than 1 year by rendering them invalid 1 year from the effective date of the interim final rule.

BIS conducts risk-based, end-use checks on exported firearms. These checks aim to prevent diversion of these weapons to unauthorized end-users after being legally exported to another country. BIS officials told us they target end-use checks in areas where the prevalence of firearms exports is a factor and there is a lack of export control office coverage.[27] Among Caribbean countries, BIS conducted end-use checks on firearms or ammunition in Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago between fiscal years 2020 and 2023. During this same period, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago had the highest number of firearms legally exported from the United States.

CBP Interdicts Firearms and Shares Information to Combat Firearms Trafficking

CBP interdicts illicit contraband, including firearms, at U.S. ports of entry enroute to the Caribbean, conducts targeted operations, and shares information with partner country law enforcement entities. Specifically,

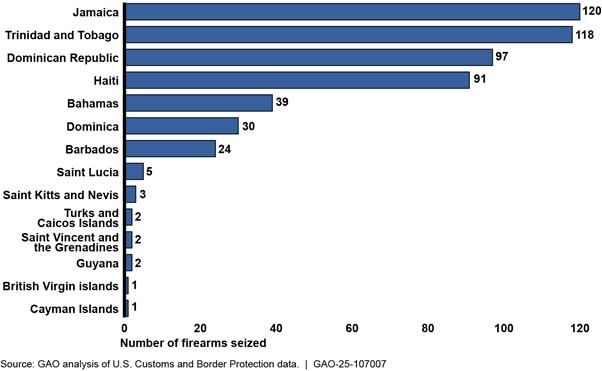

· CBP interdictions. According to CBP officials, CBP conducts examinations of outbound cargo and passenger luggage destined to the Caribbean to interdict weapons and other contraband. Additionally, CBP officials said they rely on information developed by their targeting teams, HSI, and from confidential sources to examine examinations on suspect outbound packages and persons. CBP data we analyzed show that in fiscal years 2018 through 2023 the Office of Field Operations engaged in hundreds of individual seizures, involving 535 firearms and 3,167 firearm components and conversion kits, at U.S. ports destined for Caribbean countries. Of the 535 firearms seized, 44 percent, or 238, were destined for Jamaica or Trinidad and Tobago (see fig. 10). As noted in appendix II, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago received the highest number of legally exported firearms from the U.S. and had the highest number of recovered firearms submitted for tracing.

Figure 10: Destinations of Firearms Seized by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection between 2018 and 2023

· Operation Rolling Thunder. CBP began Operation Rolling Thunder in March 2018 to identify and disrupt the illegal exportation of firearms from the U.S. via commercial air. According to CBP, this operation helped to identify individuals who were flying to the Caribbean on commercial planes while carrying firearms in their luggage. Additionally, some of these individuals would declare their weapons while in the U.S. but fail to do so upon returning. The operation also expanded its scope to detect those attempting to transport weapons covertly. In addition, CBP analyzes various factors, such as the date of ticket purchase, credit-card details, booking method, and any notifications from the airline about the passenger carrying a firearm. According to CBP, most of the individuals declaring firearms were not malicious and carried weapons for their personal safety. However, through this analysis, CBP said it identified malicious actors and established connections between them.

· CBP Information sharing. CBP officials also engage in information sharing to support broader firearms trafficking efforts. CBP has an embedded official with CARICOM’s Joint Regional Communication Center to aid with passenger targeting, maritime security, and information sharing. This center screens passengers entering and travelling within the CARICOM region by airports and seaports. CBP can issue recommendations to host countries to detain, search, or deny entry to such identified persons.

Agencies Track Results of Key Programs, but State Does Not Have Firearms Trafficking-Specific Indicators for Regional Efforts

State’s Efforts to Track Results of Regional Capacity-Building Activities Do Not Have Firearms Trafficking-Specific Indicators

State created the CBSI Results Framework to track initiative-wide results for CBSI, but it does not have indicators specific to firearms trafficking. The Framework includes three pillars, or program objectives—reduce illicit trafficking, improve safety and security, and prevent youth crime and violence—and has specified intermediate results and indicators for each program objective. For instance, under the reduce illicit trafficking program objective, intermediate results include increasing national government and regional control over territorial and maritime domain and reducing transnational crime. Indicators for these intermediate results include, for instance, kilos of narcotics seized, number of INL supported vetted units, and revenue denied to transnational criminal organizations by drug seizures. However, for the reducing illicit trafficking program objective, trafficking indicators are only specific to the seizure of narcotics, and do not include any indicators related to firearms trafficking.

State and the U.S. government at large have identified combatting firearms trafficking to the Caribbean as a strategic priority. We have previously reported that performance measurement gives managers crucial information to identify gaps in program performance and to plan any needed improvements. Developing performance metrics and assessing program performance are key actions agencies can take to define activity goals and to assess activity progress.[28]

State told us the indicators included under the reduce illicit trafficking program objective of the CBSI Results Framework reflect priorities that were identified during its development in 2020. Since then, changing priorities in response to growing crime and violence have made firearms trafficking a more prominent issue in the region. Developing firearms trafficking specific indicators would better enable State to measure progress of its combating firearms trafficking efforts. Further, representatives from CARICOM IMPACS told us they informed State INL that they believed improved performance management for all programs in the Caribbean would improve accountability and reduce duplication of efforts.

State INL uses performance reporting to track results for its primary efforts to develop Caribbean governments’ capacity to disrupt firearms trafficking. For example:

· State INL’s first quarterly report on the establishment of the Regional CGIU effort provides summary information about progress against identified performance indicators, as well as examples of actions taken or required on challenges encountered. For instance, the quarterly report summarized results related to the metric for operationalizing the CGIU and the number of firearm recovery referrals submitted to the CGIU. State INL reported that 15 countries have submitted information to CGIU staff on firearms seizures and recoveries through either direct outreach with CGIU staff or through the submission of initial information forms. The quarterly report also summarizes the number of firearm seizure reports received by the CGIU from member states, such as the Bahamas sharing nine reports, and Trinidad and Tobago sharing 13 reports. The report also provides a list of outcomes and outputs related to CGIU, such as equipping the CGIU to consolidate firearms data and to generate actionable firearms investigative leads. In addition, the report describes progress against identified performance indicators, such as installing a SharePoint system at the CGIU to facilitate information sharing and describing any variance between planned and achieved activities.

· UNLIREC summarized State INL’s effort with the UN to combat illicit firearms and ammunition trafficking in a final narrative report following the project’s completion in August 2023. This report provides summary information on key activity areas, such as reinforcing regulatory frameworks governing illicit firearms and ammunition; securing borders and preventing and combating illicit trafficking of firearms and ammunition; and bolstering firearms tracing and investigative capabilities. For instance, the report described, among other things, the UNLIREC’s implementation of interdiction training courses, including on imparting effective practices for the identification of illicit shipments or packages of firearms and ammunition at various points of entry and exit. The report also described all the participants, their numbers, as well as the training content, and concluded that about 30 forensic and investigative officials from the Caribbean, after receiving national tracing and serial number restoration training workshops, were now able to recover serial numbers on firearms and conduct firearms traces. State INL also reported that nearly 200 Caribbean officials have been familiarized with current topics related to the combatting of illicit firearms trafficking, such as identifying privately manufactured firearms and shooting incident reconstruction. The report also concluded that State and the UN’s efforts have advanced the adoption and implementation of the Caribbean Firearms Roadmap, which aims to support Caribbean countries in using sustainable and measurable solutions to control, eradicate, prevent, and prosecute the illicit possession, proliferation, and misuse of firearms and ammunition. For instance, the report indicated that eight of 15 Caribbean countries have approved their National Action Plans to implement the Caribbean Firearms Roadmap.

· A 2023 quarterly report for State INL and the World Customs Organization’s Project Bolt provided summary information on progress made against performance indicators. The report provides information on mentoring efforts and the number of customs officials, police, and other Caribbean officials that received training to build their technical capacity to detect and investigate firearms and narcotics trafficking in courier packages. The quarterly report also outlined those Caribbean countries that received briefings on their border security gaps related to firearms and narcotics in courier packages.

ATF Tracks Results of Efforts to Combat Firearms Trafficking Through Various Means

ATF tracks the results of its primary efforts for developing the capacity of Caribbean governments to disrupt firearms trafficking through performance monitoring, feedback, and surveys. For example:

· ATF tracks results of eTrace in several ways. On its website, ATF publishes eTrace data on firearms recovered in the Caribbean and submitted to ATF for tracing for the top five reporting Caribbean nations. ATF officials told us that their analysis and monitoring of this information contributes to decisions regarding where to place ATF agents in the field and helps them determine whether their eTrace outreach efforts are beneficial. ATF published Volume 2 of their National Firearms Commerce and Trafficking Assessment of Crime Guns report in January 2023. This report provides information on crime guns recovered outside the U.S. and traced by law enforcement; information on ATF’s efforts to conduct international eTrace training; as well as various statistics on firearms recovered and traced, such as international crime gun traces associated with a gun show.[29]

· ATF officials told us that their National Tracing Center, which processes eTrace requests, has performance measures for monitoring workload and evaluating the productivity of conducting traces and supporting ATF with investigative leads. ATF officials also told us that the Center’s ability to support ATF and DOJ strategic goals is evaluated in two specific areas: (1) the percentage of urgent trace requests completed in 48 hours or less, with a target of 95 percent; and (2) the percentage of routine trace requests completed in 7 days or less, with a target of 75 percent. ATF officials told us that they also have a broad goal to increase the use of eTrace and the sharing of intelligence from eTrace information, which would lead to greater cooperation on firearms trafficking and prosecution.

· According to ATF officials, the Monitored Case Program, which provides additional headquarters oversight for cases involving 10 or more firearms, is an assessment tool that evaluates the plans, progress, and challenges associated with those higher-risk investigations and inspections. ATF leadership monitors the Monitored Case Program by continually evaluating and adapting the program based on feedback, experience, and the further identification of operational risks. This process may enable leadership to modify the criteria used to identify cases, inspections, and incidents that fall under the review of the program. For example, according to ATF officials, DOJ’s Office of Inspector General recently identified a potential risk involving the enforcement of settlement agreements between ATF and federal firearms licensees who were cited for violations of regulatory requirements. In response, ATF updated the Monitored Case Program to begin tracking settlement agreements.

· ATF in partnership with State’s International Law Enforcement Academies, conducts surveys, and reviews the survey results, of their small arms trafficking training. This training provides law enforcement with information on firearms identification, tracing, and trafficking. ATF officials indicated that Haiti, Jamaica, the Bahamas, and Trinidad and Tobago all sent representatives to the training in 2023 and 2024.

DHS’s HSI and CBP Report Results of Capacity Building and Firearms Trafficking Disruption Efforts

HSI and CBP use reporting on program results to track their primary efforts to develop the capacity of Caribbean governments to disrupt firearms trafficking. For example:

· The Caribbean Firearms Initiative, which is focused on outreach, education, and capacity building related to firearms trafficking, has led to increased communication between U.S. agencies and Caribbean officials, according to HSI officials. HSI has reported that the initiative in 2023 contributed to regional security through partnerships with Caribbean law enforcement and Customs agencies, collectively seizing 344 firearms, 224,438 rounds of ammunition, and about $391,000 in U.S. currency.

· Operation Hammerhead, an interagency and international counter-firearms trafficking effort, has led to the initiation or support of several international firearms trafficking cases, according to HSI officials. HSI has reported that as of November 2023, Operation Hammerhead reviewed 211,061 Caribbean-bound exports, referred 1,924 with some level of risk, and supported eight firearms trafficking investigations. During Operation Hammerhead’s timeframe, officials seized 48 pistols, 10 rifles, 10 magazines, four revolvers, and 3,371 rounds of ammunition that were already in, or destined for the Caribbean.

· Operation Rolling Thunder, which is in place to identify and disrupt the illegal exportation of firearms from the U.S. via commercial air, has led to the interception of multiple firearms, firearm components and accessories, and ammunition, according to CBP officials. CBP officials told us that they monitor the program through annual reporting. For instance, CBP’s reporting includes information and statistics on the number of firearms, firearm components, and ammunition intercepted, as well as on departure ports and foreign destination ports. It also provides summary information on the status of significant firearms trafficking cases and CBP’s coordination efforts with domestic agencies and foreign countries regarding efforts to educate and train CBP officials at ports that are gateways to countries known to be destinations for illegal firearms. CBP’s report on this program indicated that in the first 6 months of fiscal year 2023, CBP and foreign partners intercepted 25 firearms, 24 firearm components and accessories, and 786 rounds of ammunition. The report also indicates that CBP addressed illegal firearms exportation by strategically coordinating enforcement activity with domestic agencies and with other countries. The report also includes information on CBP’s efforts to identify and track trends and methods related to exporting illegal firearms.

Conclusions

The illegal flow of firearms from the U.S. fuels increasing levels of violence and crime throughout the Caribbean, according to U.S. and Caribbean officials. From 2018 through 2022, most firearms recovered in 25 Caribbean countries were sourced from the United States. U.S. agencies track results of key efforts to combat firearms trafficking to the Caribbean in a variety of ways. However, State’s CBSI Results Framework, used to track initiative-wide results for reducing illicit trafficking, improving safety and security, and preventing youth crime and violence, does not have indicators for firearms trafficking. Developing firearms trafficking specific indicators would better enable State to measure progress of its combating firearms trafficking efforts.

Recommendations for Executive Action

The Secretary of State should ensure that the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement updates the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative’s Results Framework to establish firearms trafficking specific indicators. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to State, DOJ, Commerce, and DHS for review and comment. We received technical comments from State, Commerce, and DHS which we incorporated as appropriate. State provided written comments that are reproduced in appendix III. In its response, State concurred with our recommendation.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Attorney General of the United States, the Secretary of Commerce, the Secretary of Homeland Security, and the Secretary of State. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-2964 or KenneyC@gao.gov. Contact points for our Office of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the

last page of this report. GAO staff who made contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Chelsa Kenney

Director, International Affairs and Trade

List of Requesters

The Honorable Gregory W. Meeks

Ranking Member

Committee on Foreign Affairs

House of Representatives

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Joaquin Castro

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Western Hemisphere

Committee on Foreign Affairs

House of Representatives

The Honorable J. Luis Correa

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Border Security and Enforcement

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Seth Magaziner

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Counterterrorism, Law Enforcement, and Intelligence

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Richard J. Durbin

United States Senate

The Honorable Sheila Cherfilus-McCormick