WATER INFRASTRUCTURE RESILIENCE

Agencies Could Better Assess Efforts to Assist Communities Vulnerable to Natural Disasters

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Chris Currie at curriec@gao.gov or J. Alfredo Gómez at gomezj@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) provided different types of financial assistance to improve drinking water and wastewater infrastructure in fiscal years 2014 through 2023. Specifically, 14 of the agencies’ programs provided $35 billion in grants (at least 22,000 projects) and $29 billion in direct loans (about 4,800 projects) during this period.

EPA, FEMA, and USDA took steps to reduce barriers to financial assistance faced by vulnerable communities—those likely to face challenges preparing for and recovering from disasters, such as rural and low-income areas. In this report, GAO used the term “vulnerable communities” to refer to communities defined in some programs’ authorizing statutes that may receive additional assistance under these programs. These statutes were not affected by recent executive orders or actions. Agencies provided technical assistance and allowed grantees to use assistance from other federal programs to meet requirements to provide matching funds, known as nonfederal cost share. However, FEMA has not adequately communicated about the option to use assistance from USDA programs to meet cost-share requirements in certain cases.

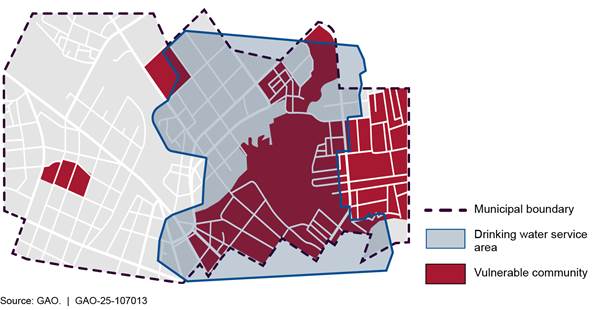

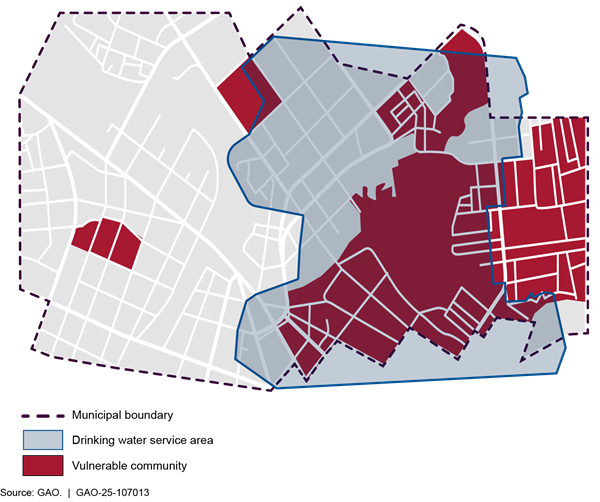

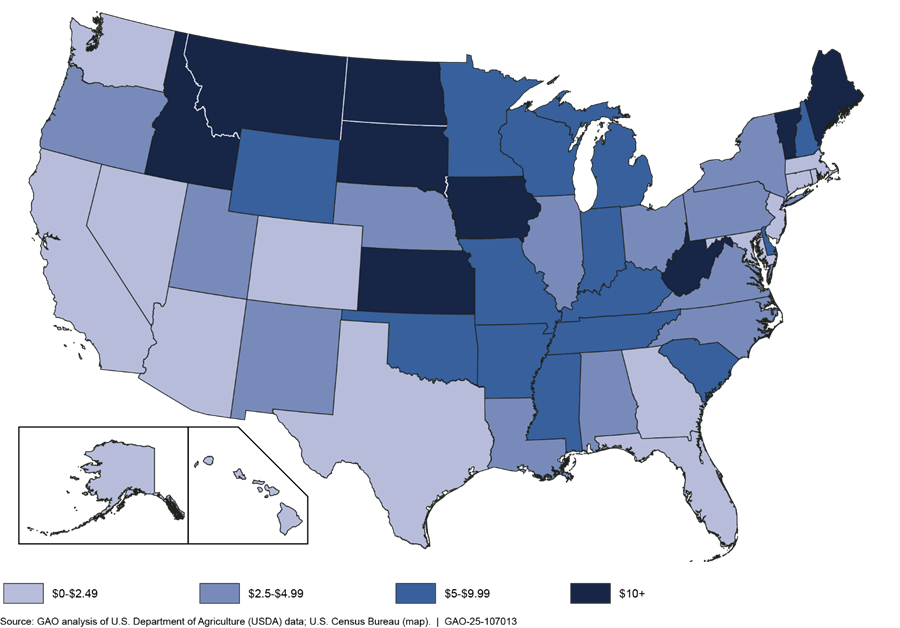

EPA, FEMA, and USDA used national or state measures to assess the extent to which vulnerable communities benefitted from certain programs. However, EPA, FEMA, and USDA officials said that limited data about the geographical areas served by drinking water and wastewater utilities made it difficult to accurately assess who benefited from their programs. EPA created a mapping tool with the geographical service areas of drinking water systems, which may differ from municipal boundaries (see fig.). EPA plans to complete a similar tool for wastewater service areas in summer 2025. Using EPA’s mapping tools could enable EPA, FEMA, and USDA to more accurately identify the communities, including vulnerable communities, their programs are benefiting.

Why GAO Did This Study

Drinking water and wastewater utilities have experienced disruption or failure after disasters, threatening public health. For example, disasters in Mississippi in 2022 and North Carolina in 2024 left residents without potable water for weeks. Federal agencies provide assistance for utilities to build resilience against natural disasters—including communities in rural and low-income areas vulnerable to disasters.

This report examines, among other things, (1) financial assistance that EPA, FEMA, and USDA provided to improve water infrastructure; (2) the extent to which these agencies addressed barriers vulnerable communities face accessing and participating in selected programs; and (3) how these agencies assessed the extent to which assistance reached vulnerable communities.

GAO analyzed fiscal year 2014–2023 data for EPA, FEMA, and USDA programs that provided financial assistance for water infrastructure projects—the most recent data available during the review. GAO also reviewed relevant executive orders and agencies’ plans and actions taken to address barriers faced by vulnerable communities. Finally, GAO interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 14 utilities selected based on factors including vulnerability and disaster experience.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making eight recommendations, including that FEMA communicate about options to meet cost-share requirements, and that EPA, FEMA, and USDA use service area map tools. EPA and FEMA disagreed with using the tools. USDA did not comment. GAO maintains its recommendations are valid, as discussed in this report.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

EPA |

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

August 11, 2025

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Robert Garcia

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

House of Representatives

Drinking water utilities and wastewater utilities can be vulnerable to disruption or failure following natural disasters, leaving communities without service and threatening public health. For example, in August 2022 the largest drinking water treatment plant in Jackson, Mississippi, failed following heavy rains and flooding. As a result, the over 150,000 residents of Jackson were without potable water for more than 2 weeks.[1] This outage was preceded by frequent water service interruptions over many years, with the City of Jackson issuing over 500 boil water alerts per year from 2015 through 2021, according to one study.[2]

More recently, in September 2024 Hurricane Helene caused catastrophic flooding in western North Carolina—including in rural and low-income areas—severely damaging major water transmission lines, reservoirs, and treatment facilities. Over 100,000 residents were left without potable water for nearly 2 months. Restoring drinking water was particularly challenging due to the hurricane’s damage to roads and bridges that, combined with western North Carolina’s mountainous geography, isolated communities and hindered repair crews’ access to damaged infrastructure.

Federal agencies, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) within the Department of Homeland Security, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), administer a variety of programs that provide financial and technical assistance to improve drinking water and wastewater infrastructure. Such assistance can be used to improve the resilience of this infrastructure—in other words, the ability to prepare for anticipated hazards, adapt to changing conditions, and withstand and recover rapidly from disruptions.[3]

Certain communities are disproportionately susceptible to the impacts of disasters and face significant challenges achieving resilience. These communities are located in both rural and urban areas and span diverse social and demographic groups. The terminology used to describe these communities varies. Such communities may be referred to in statutes as “disadvantaged,” “economically stressed,” or “rural,” among other terms, and may be defined in various ways. We use the term “vulnerable communities” throughout this report to refer to communities that are likely to experience heightened challenges in preparing for, withstanding, and recovering from disasters, particularly in relation to water infrastructure. We use program-specific terminology and definitions where applicable. In some cases, a vulnerable community may be the entity that applies for financial assistance—such as a rural, small town. In other cases, the entity that applies for assistance might not meet the program’s definition of vulnerable, but it might contain a vulnerable community within it—such as a city that has low-income neighborhoods within it.

In 2020, FEMA’s National Advisory Council reported that federal disaster relief is often disproportionately provided to larger communities that have considerable resources. The council reported that smaller, less resource-rich, and rural communities often cannot access financial assistance to appropriately prepare for disasters, leading to inadequate disaster response and recovery.[4] This report also stated that disaster vulnerability is associated with income, poverty, race, ethnicity, and physical ability, among other factors. Further, the report states that the same factors that disadvantage members of society on a daily basis increase the exposure of these populations to physical hazards and to the social, economic, political, and psychological impacts of disaster events.

In addition, FEMA has reported that historically disadvantaged populations may be particularly vulnerable to disasters and may require additional support to adequately prepare for and recover from disasters.[5] The number and cost of weather and climate disasters are increasing in the U.S., according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which may further challenge vulnerable communities’ ability to be resilient to disasters.[6]

You asked us to examine how federal agencies have provided assistance to increase the resilience of drinking water and wastewater utilities that are vulnerable to the effects of natural disasters. You also asked us to examine how agencies implemented prior executive orders in these sectors. This report examines (1) financial assistance that EPA, FEMA, and USDA provided in fiscal years 2014 through 2023 to improve drinking water and wastewater infrastructure; (2) financial challenges related to infrastructure resilience faced by selected water utilities, including those in vulnerable communities; (3) the extent to which EPA, FEMA, and USDA addressed barriers that may prevent vulnerable communities from accessing and participating in selected programs; and (4) how EPA, FEMA, and USDA assessed the extent to which financial assistance from selected programs reached vulnerable communities.

To examine financial assistance that EPA, FEMA, and USDA provided to improve drinking water and wastewater infrastructure, we reviewed prior GAO work and publicly available documents, including program authorizing statutes, regulations, program descriptions, and Federal Register notices.[7] We determined that, during the period of our review, 19 programs could provide financial assistance for water infrastructure, and 15 of these programs had done so.[8] We did not analyze data from one of these programs—FEMA’s Public Assistance—because of limitations in the data that made it unfeasible to determine the amount of assistance provided for water infrastructure. We therefore analyzed financial assistance data for 14 programs.

We selected the period of fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2023 to account for variations of natural disasters and to include years before and during the Justice40 Initiative, among other factors.[9] The Justice40 Initiative centered on the goal that 40 percent of the benefits of certain federal investments—including certain investments in water infrastructure—should flow to disadvantaged communities.[10] To examine federal financial assistance, we reviewed and analyzed EPA, FEMA, and USDA budgetary data and compared it to publicly available data when available.

To identify the financial challenges related to infrastructure resilience faced by selected water utilities, including those in vulnerable communities, we interviewed representatives from 14 drinking water and wastewater utilities.[11] We selected utilities to obtain a variety of perspectives based on factors such as geographic location, population size, and recent experiences with natural disasters and the financial assistance programs in our review. Findings from these interviews are not generalizable to other drinking water and wastewater utilities. However, the interviews provided valuable insight into the challenges faced by such utilities.

To examine the extent to which EPA, FEMA, and USDA addressed barriers that may prevent vulnerable communities from accessing and participating in selected programs, we identified 10 of these agencies’ programs that provided financial assistance for water infrastructure during our review period and that were selected to participate in the Justice40 Initiative. We reviewed these programs’ authorizing statutes to identify any requirements to provide assistance to vulnerable communities and any definitions of such communities. We also analyzed documentation of actions the agencies took to address barriers faced by vulnerable communities, such as program policies, technical assistance efforts, and interagency agreements. We interviewed relevant agency officials and technical assistance providers, and we asked the utility representatives that we interviewed about any challenges they experienced when applying for and managing awards from federal assistance programs in our scope.

We assessed EPA, FEMA, and USDA actions against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government related to information and communication.[12] We also assessed the agencies’ actions against selected key practices for effectively managing and assessing the results of federal efforts.[13] We identified the key practice about generating new evidence as relevant to this objective.

To examine how the three agencies assessed the extent to which financial assistance from selected programs flowed to vulnerable communities, we interviewed agency officials and reviewed agency documentation related to analyses they conducted. We assessed the agencies’ actions against selected key practices for effectively managing and assessing the results of federal efforts. We determined that the key practices related to generating new evidence and using evidence to assess program results were relevant to this objective.[14]

We also conducted a statistical analysis of the distribution of financial assistance from two EPA programs from fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2023.[15] Additionally, we analyzed data from two FEMA and USDA programs to describe recipient counties’ socioeconomic characteristics.[16] Appendix I describes our objectives, scope, and methodology in more detail. Appendix II contains details on our methodology for the analyses described in this paragraph.

We assessed the reliability of the data used in our analyses by (1) performing electronic testing for errors in accuracy and completeness, (2) reviewing related documentation about the data and the systems that produced them, (3) interviewing agency officials knowledgeable about the data, and (4) working closely with agency officials to identify and resolve data discrepancies. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of analyzing financial assistance that EPA, FEMA, and USDA provided to improve drinking water and wastewater infrastructure, and the extent to which benefits of selected programs flowed to vulnerable communities from fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2023.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to August 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure

Approximately 50,000 community drinking water systems and 16,500 public wastewater systems provide clean and safe water to communities across the U.S.[17] Drinking water and wastewater infrastructure are the largest financial investments by communities nationwide, according to a 2014 study by the Water Research Foundation.[18] Such infrastructure includes water tanks, pipes, pumps, and buildings that contain electrical, chemical, and mechanical equipment to treat and test water. Local governments and their utilities generally pay the majority of the costs to repair, replace, and upgrade this infrastructure, primarily by charging rates for drinking water and wastewater services. Various federal programs also provide financial assistance for projects that help improve this infrastructure.

In addition to repairing or replacing old or degraded water infrastructure, other types of modifications can improve resilience to the effects of natural disasters. For example, drinking water utilities can improve infrastructure resilience by installing flood stop plates and sealing doors, modifying source water intake pipes to enhance drought and flood resilience, and improving the ability to treat water with high sediment levels after wildfires. Wastewater utilities can improve infrastructure resilience by reinforcing sewer lines that cross rivers, constructing wetlands to improve stormwater management, and relocating facilities outside of floodplains, among other things. In addition, elevating critical equipment and power generators above flood levels and obtaining backup power generators can improve infrastructure resilience for both types of utilities.

Federal Roles in the Water Sector

EPA, FEMA, and USDA have different roles in supporting drinking water and wastewater infrastructure, in accordance with their different missions.

· EPA generally focuses on renewing and maintaining water infrastructure to deliver clean drinking water and to safely treat and discharge wastewater, in accordance with its mission to protect human health and the environment. For example, EPA’s Drinking Water State Revolving Fund and Clean Water State Revolving Fund programs provide grants to states, which then make low-interest loans or grants to local communities and utilities for drinking water and wastewater infrastructure projects, among other eligible activities.[19]

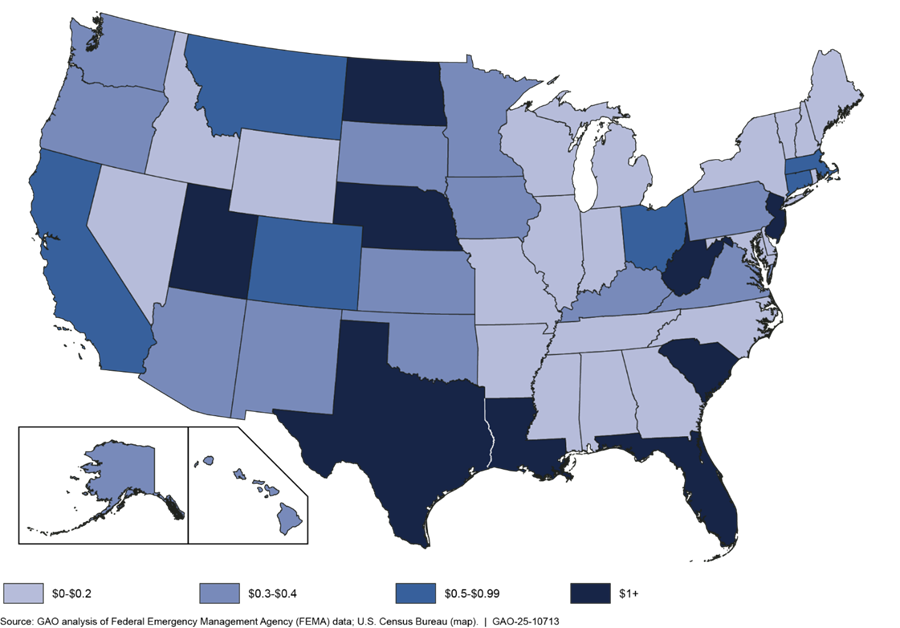

· In accordance with its mission to help people before, during, and after disasters, FEMA’s role in supporting drinking water and wastewater infrastructure focuses on repairing or replacing infrastructure damaged during natural disasters and enhancing resilience against future damage. During the period of our review, FEMA programs that supported this role included the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program, which provided pre-disaster hazard mitigation assistance, and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, which provides post-disaster hazard mitigation assistance.[20]

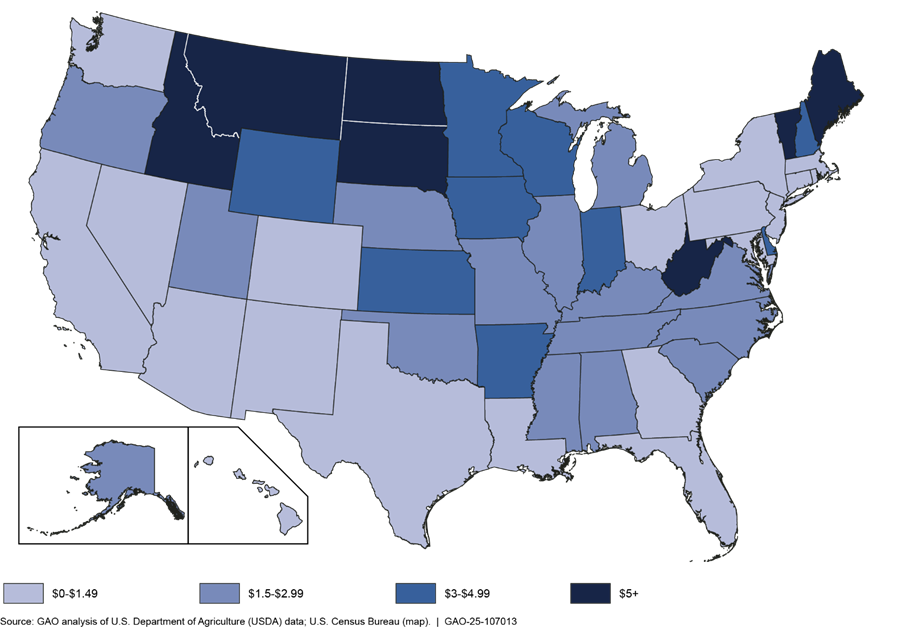

· USDA provides financial and technical assistance to support water infrastructure in communities with a population of 10,000 or less, in accordance with its Rural Development mission area. For example, USDA’s Water and Waste Disposal Loan and Grant Program provides grants, loans, and loan guarantees for eligible drinking water and wastewater projects in rural areas. Direct loans are obligated through three interest rate tiers. Two tiers are subsidized, including one tier for low-income communities impacted by health or sanitary issues, according to USDA officials.

See appendix III for descriptions of all 19 EPA, FEMA, and USDA programs we identified that could provide financial assistance for drinking water and wastewater infrastructure during the period of our review.

Statutes and Prior Executive Orders Related to Assistance to Vulnerable Communities

The authorizing statutes for certain federal programs that provide assistance for water infrastructure include provisions to provide financial assistance in various ways for vulnerable communities, as defined in those statutes. For example, the Safe Drinking Water Act, as amended, requires states to use from 12 percent to 35 percent of EPA’s grants for their drinking water revolving funds as additional subsidies for disadvantaged communities if the states receive sufficient loan applications from these communities.[21] Similarly, the Clean Water Act, as amended, requires states to use from 10 percent to 30 percent of EPA’s grants for their clean water revolving funds to provide additional subsidies to municipalities that meet certain affordability criteria if the state receives sufficient applications for assistance from these communities and if EPA capitalization grants to all states for the fiscal year exceed $1 billion.[22]

In addition, the Stafford Act, as amended—which authorizes FEMA’s hazard mitigation assistance programs, including those that provide financial assistance for water infrastructure—states that one of its purposes is to improve the natural hazard resilience of vulnerable communities.[23] It also authorizes FEMA to contribute a greater share of the total cost of mitigation activities under the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program carried out in Economically Disadvantaged Rural Communities[24] or within, or that primarily benefit, Community Disaster Resilience Zones.[25]

Lastly, USDA programs that provide loans and grants for water infrastructure are to prioritize applications from rural communities having a population of 5,500 or less and meeting certain other criteria.[26] Various appropriations acts have directed USDA to allocate at least 10 percent of the appropriations for these loans and grants for assistance in territories or persistent poverty counties, which are counties in which at least 20 percent of the population has lived in poverty over the past 30 years.[27] Further, USDA’s regulation that implements its Water and Waste Disposal Loan and Grant Program states that the program’s purpose is to provide financial assistance for projects serving the most financially needy communities.[28]

Until their revocation, several executive orders had called for federal agencies to prioritize financial assistance for vulnerable communities, including assistance to improve drinking water and wastewater infrastructure. Specifically:

· Executive Order 14008, which established the Justice40 Initiative, was issued in 2021.[29] This initiative centered on the goal that 40 percent of the benefits of certain federal investments—including investments in water infrastructure—should flow to disadvantaged communities. For programs that participated in the initiative, agencies were directed to calculate the percentage of program benefits that flowed to and accrued in disadvantaged communities and report the results to the Office of Management and Budget.[30] This order was revoked in January 2025.

· Executive Order 13985, also issued in 2021, directed the White House Domestic Policy Council to coordinate federal agencies’ efforts to remove barriers to equal opportunity and programmatic benefits for people of color, people who live in rural areas, and other underserved communities.[31] This order was revoked in January 2025.

· Executive Order 12898, issued in 1994, called for all federal agencies to make achieving environmental justice part of their mission by identifying and addressing disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of programs, policies, and activities on minority populations in the U.S.[32] This order was revoked in January 2025.

Prior GAO Work on Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Resilience

In January 2020, we reported that EPA, FEMA, and USDA did not consistently consider climate information when providing financial assistance to improve the resilience of drinking water and wastewater infrastructure.[33] To address this, we recommended that Congress consider requiring climate resilience to be incorporated in the planning of drinking water and wastewater projects that receive financial assistance from these agencies. As of February 2025, Congress had not taken action on this matter. We also recommended that EPA engage a network of technical assistance providers to help utilities incorporate climate resilience into their projects and planning. As of December 2024, EPA officials told us that EPA was building a network of technical assistance providers to help water systems address infrastructure issues, including climate resilience.

We reported in February 2015 on challenges that utilities in rural communities faced at that time related to funding drinking water and wastewater infrastructure.[34] For example, some utilities did not have the number of users needed to share the cost of major infrastructure projects. Also, some utilities lacked the technical expertise needed to apply for financial assistance.

In 2021 we reported that some applicants found the application process for certain FEMA programs to be too complex and lengthy.[35] We recommended that FEMA establish a plan to identify and implement steps to reduce the complexity of, and time required for, its grant applications.[36] In May 2022, FEMA officials said they revised the grant award process for the Flood Mitigation Assistance and Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities programs to provide for “round 1” approvals, reducing the application time frame by 2–3 months for certain applicants.

Also in 2021, we reported that certain FEMA programs did not collect or analyze demographic data to identify or address barriers that vulnerable populations and others experienced in accessing these programs.[37] We made two priority recommendations: (1) that FEMA develop and implement a plan to ensure the availability and use of data to identify such barriers and (2) that FEMA establish routine processes to address any barriers it identifies. FEMA agreed with our recommendations. In February 2025, FEMA officials told us that the agency had developed but had not yet implemented a plan for data collection, sharing, and analysis to identify potential equity issues.

Billions Provided in Fiscal Years 20142023 to Improve Water Infrastructure

EPA, FEMA, and USDA Provide Different Types of Financial Assistance for Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure

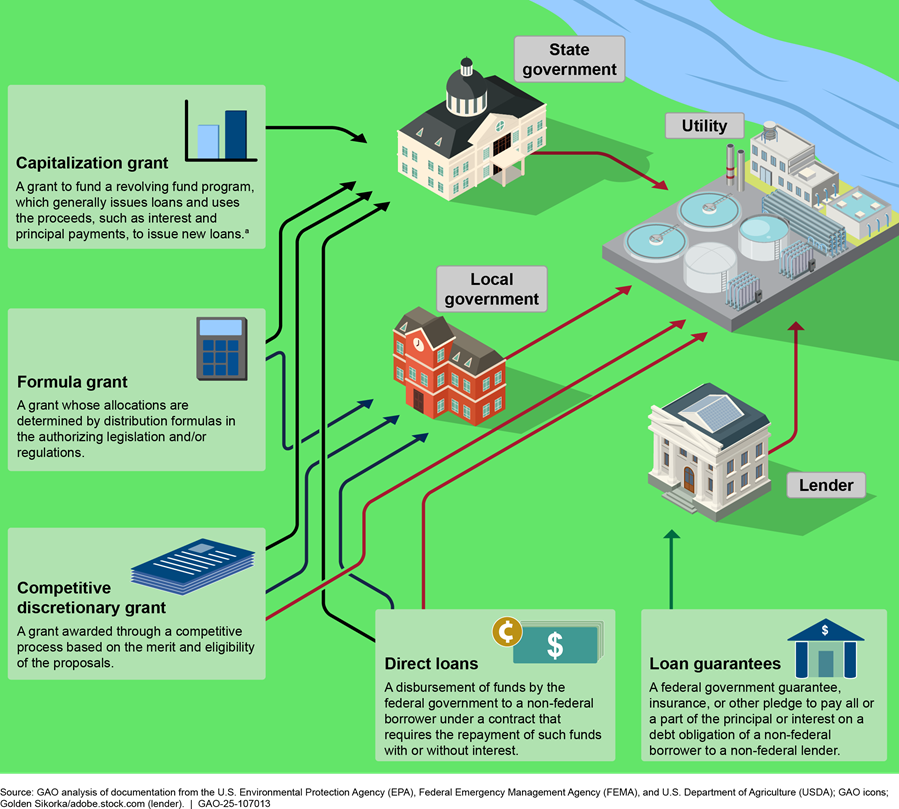

EPA, FEMA, and USDA provide different types of financial assistance for projects focused on building or improving drinking water and wastewater infrastructure, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Types of Financial Assistance Provided by EPA, FEMA, and USDA for Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Projects

aThe defining feature of a revolving fund is its ability to retain and use ongoing receipts after the initial capitalization. Federal law authorizes and provides appropriations to agencies to award capitalization grants to eligible entities such as state governments and nonprofit organizations to establish a revolving fund. These entities use their revolving funds to issue loans and other authorized financial assistance for eligible projects to improve water infrastructure and other activities. Loan repayments and interest flow back into the revolving fund which can be used to provide additional loans and financial assistance.

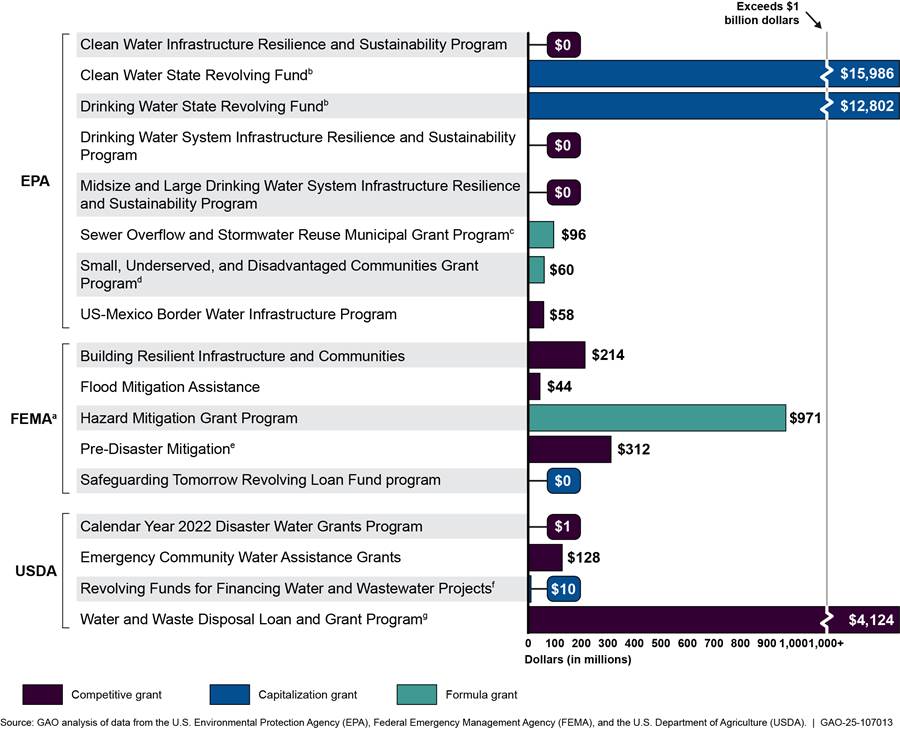

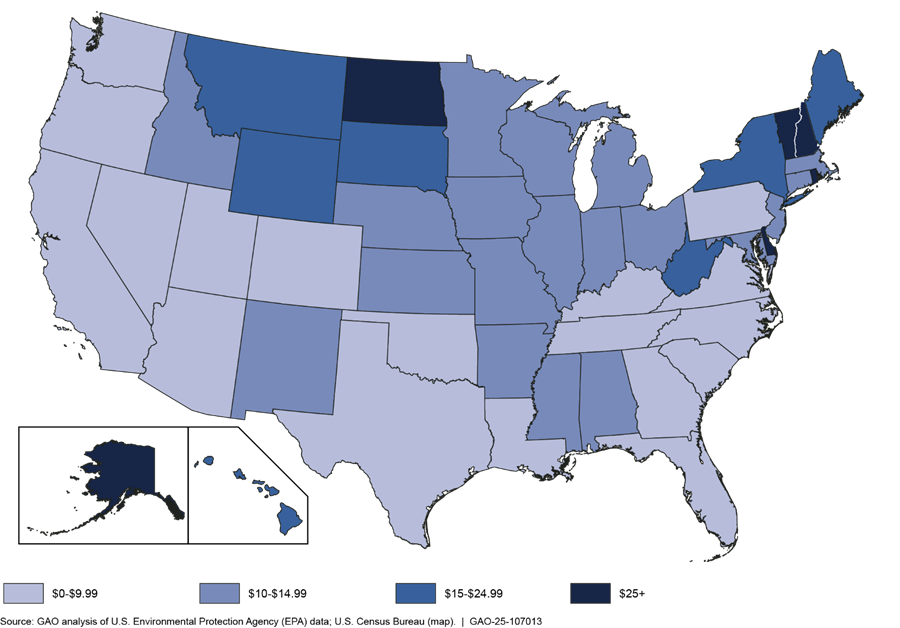

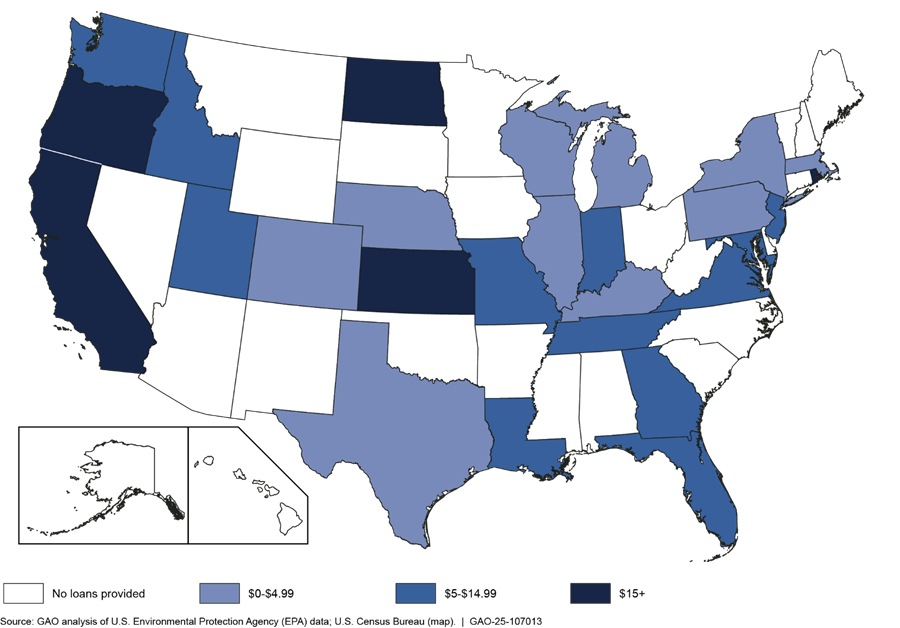

Most Financial Assistance Was Provided as Capitalization Grants and Direct Loans

EPA, FEMA, and USDA provided assistance mainly in the form of capitalization grants and direct loans. Of the 18 programs we reviewed that could provide financial assistance, 17 are grant programs.[38] Thirteen of these grant programs made financial assistance available in fiscal years 2014 through 2023. Specifically, EPA, FEMA, and USDA obligated about $35 billion in grants during this period.[39] Three programs obligated 95 percent of these grant funds: (1) EPA’s Clean Water State Revolving Fund, (2) EPA’s Drinking Water State Revolving Fund, and (3) USDA’s Water and Waste Disposal Loan and Grant Program.[40] About $30 billion of these obligations were in the form of capitalization grants, according to our analysis. States used capitalization grant-funded revolving funds to provide financial assistance for at least 17,121 projects during our review period.[41] The remainder of the grant funds provided financial assistance for 5,348 projects. See appendix IV for maps showing the nationwide distribution of grants and direct loans provided by EPA, FEMA, and USDA for water infrastructure during our review period.

In addition to the 13 grant programs that provided financial assistance, we identified four other grant programs through which the agencies could provide financial assistance for water infrastructure but that had not made any obligations as of the end of fiscal year 2023. These programs are: (1) EPA’s Clean Water Infrastructure Resilience and Sustainability program, (2) EPA’s Drinking Water System Infrastructure Resilience and Sustainability program, (3) EPA’s Midsize and Large Drinking Water System Infrastructure Resilience and Sustainability Program, and (4) FEMA’s Safeguarding Tomorrow Revolving Loan Fund program.[42] For the first of these programs, which was authorized in 2021, EPA officials said that no funds had been appropriated as of March 2025. For the second program, EPA began making obligations in April 2025, according to EPA officials. EPA had not selected its first round of grant recipients for the third program as of the end of fiscal year 2023. For the fourth program, FEMA began selecting recipients in 2023 and began providing funds in April 2024. Figure 2 shows the amount of obligations made from fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2023 for the 17 grant programs we reviewed.

Figure 2: Obligations for Selected EPA, FEMA, and USDA Grant Programs for Projects to Improve Water Infrastructure, Fiscal Years 2014–2023

Note: This figure does not include programs that provide financial assistance for projects focused on water quality improvement activities such as lead removal, emerging contaminants, or watershed quality. Figures are not adjusted for inflation.

aFEMA also made obligations for drinking water and wastewater infrastructure projects, among other types of projects, through its Public Assistance during this period. However, we are not including this program in this figure because we were unable to identify the amount of obligations for water infrastructure projects made through this program due to limitations of the program’s data.

bEPA uses a formula to award a capitalization grant for each state revolving loan fund program. See 33 U.S.C. §§ 1381(a), 1384, 1285 (Clean Water State Revolving Funds); 42 U.S.C. § 300j-12(a)(1) (Drinking Water State Revolving Funds).

cEPA uses a formula to award grants to states that considers the state’s need for municipal combined sewer overflow controls, sanitary sewer overflow controls, and stormwater and any other appropriate information. 33 U.S.C § 1301(g)(2). States then award competitive grants to municipalities for planning, design, and construction of treatment works to intercept, transport, control, treat, or reuse municipal combined sewer overflows, sanitary sewer overflows, or stormwater, among other eligible activities. 33 U.S.C § 1301(a)(1). EPA can also award grants directly to municipalities for these purposes. 33 U.S.C § 1301(a)(2).

dEPA uses a formula to award grants to states to assist communities that are underserved and either small or disadvantaged that are unable to finance activities needed to comply with Safe Drinking Water Act requirements. 42 U.S.C. § 300j-19a. States are to use the grants to award competitive grants to support eligible public water systems within their jurisdiction. See EPA, Small, Underserved, and Disadvantaged Communities Grant Program Implementation Document (Dec. 2021).

ePre-Disaster Mitigation was a competitive grant program through the fiscal year 2019 grant cycle. It was considered to have been replaced by the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program starting in the fiscal year 2020 cycle, but starting in fiscal year 2022, it awarded grants to recipients enumerated in the joint explanatory statements accompanying the relevant appropriations acts. Since then, it has been called Pre-Disaster Mitigation Congressionally Directed Spending.

fUSDA’s Revolving Funds for Financing Water and Wastewater Projects program uses a competitive selection process to award capitalization grants to qualified private or nonprofit entities, which then provide loans to eligible water and wastewater systems for pre-development costs for short-term small capital improvement projects and other projects that are not part of the regular operations and maintenance. See 7 U.S.C. § 1926(a)(2)(B); 7 C.F.R. pt. 1783.

gUSDA uses a formula to allocate funds to each Rural Development state office to issue competitive grants and direct loans. See 7 C.F.R. § 1780.18(a)(2).

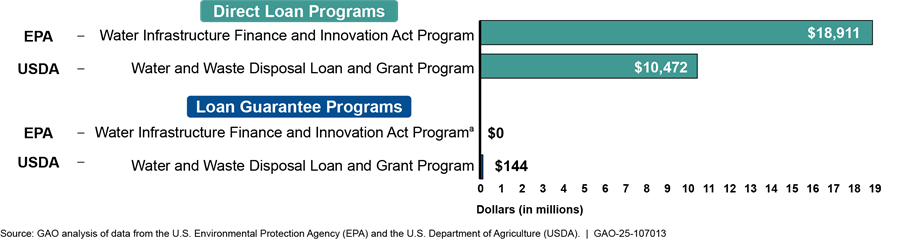

During the period of our review, EPA’s Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program provided financial assistance in the form of direct loans, and USDA’s Water and Waste Disposal Loan and Grant Program provided grants, direct loans, and loan guarantees. For fiscal years 2014 through 2023, these two programs approved direct loans that totaled about $29.4 billion, which accounts for about 46 percent of the financial assistance provided across the programs we reviewed. Direct loans provided financial assistance for 4,848 projects during our review period. Unlike grants, direct loans are to be repaid to the federal government, with or without interest.

These two programs also offer loan guarantees, which are federal guarantees or insurance for the payment of all or part of a debt obligation of non-federal borrowers to non-federal lenders. Loan guarantee programs help borrowers obtain access to credit with more favorable terms than they may otherwise obtain in private lending markets. This is because the federal government guarantees to pay the lender if the borrower defaults, which makes extending credit more attractive to lenders.

Because direct loans are to be repaid and loan guarantees provide insurance that may not be necessary, the loan value of direct loans and loan guarantees, shown in figure 3, is generally larger than the cost to the government for this assistance.

Federal agencies are required to annually estimate the long-term cost, sometimes referred to as subsidy costs, of a new group of loans or loan guarantees based on expected loan performance.[43] Agencies also annually update, or reestimate, the cost of loans made in prior years. These annual updates take into account actual loan performance as well as revised assumptions about economic factors and future loan performance. The full costs of the loans will not be known until the end of the loan terms.

Figure 3: Loan Value of EPA and USDA Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees Approved for Projects to Improve Water Infrastructure, Fiscal Years 2014–2023

Note: This figure does not include programs that provide financial assistance for projects focused on water quality improvement activities such as lead removal, emerging contaminants, or watershed quality. Figures are not adjusted for inflation.

aThe Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act Program may provide loan guarantees in certain cases. See 42 U.S.C. § 3908(e)(1). The program did not issue loan guarantees from fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2023.

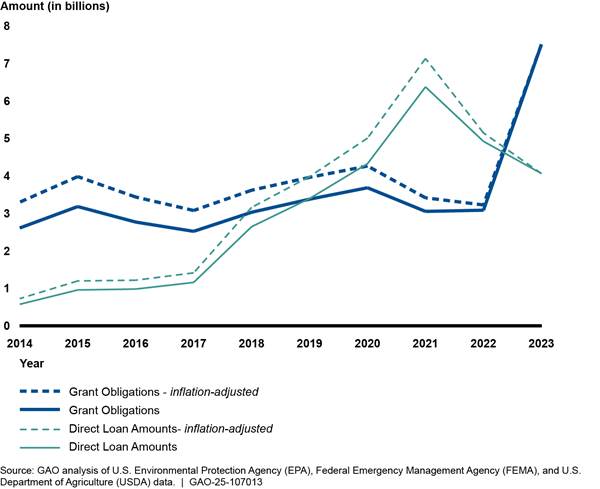

The loan value of direct loans and obligations for grants for water infrastructure generally rose from fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2023 for the programs we reviewed, as shown in figure 4. EPA’s Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program provided 64 percent of direct loans for drinking water and wastewater infrastructure across the two direct loan programs we reviewed. According to program officials, the amount of loans provided by this program increased from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2021 because of an increase in program staff levels and a decrease in interest rates during this period. Loan amounts then decreased in fiscal year 2022 and 2023 because of rising interest rates and greater availability of grant and supplemental funding such as appropriations through the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, according to program officials.[44] Obligations for competitive grants for water infrastructure generally increased in that time as well—from $333 million in fiscal year 2014 to $526 million in fiscal year 2023.

Figure 4: Direct Loan and Grant Amounts for Selected Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Financial Assistance Programs, Fiscal Years 2014–2023

Note: This graphic depicts financial assistance from 12 grant programs, one direct loan program, and one program that provided grants and direct loans. The EPA programs depicted are the Clean Water State Revolving Fund; Drinking Water State Revolving Fund; Sewer Overflow and Stormwater Reuse Municipal Grant program; Small, Underserved, and Disadvantaged Communities Grant program; the U.S.-Mexico Border Water Infrastructure Program; and the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program. The FEMA programs depicted are the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, Flood Mitigation Assistance, and Pre-Disaster Mitigation programs, and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. The USDA programs depicted are the Calendar Year 2022 Disaster Water Grants program, Emergency Community Water Assistance Grants program, Revolving Funds for Financing Water and Wastewater Projects program, and Water and Waste Disposal Loan and Grant Program. This figure does not include programs that provide financial assistance for projects focused on water quality improvement activities such as lead removal, emerging contaminants, or watershed quality.

Utilities Identified Challenges Related to Infrastructure Resilience Costs

Repairing and Replacing Aging Infrastructure

Even with the financial assistance provided by federal government agencies, drinking water and wastewater utilities still face substantial costs to maintain, upgrade, or replace aging and deteriorating infrastructure—approximately $1.3 trillion over 20 years, according to EPA estimates.[45] As previously mentioned, local governments and their utilities generally cover the majority of costs to improve this infrastructure, primarily by charging rates for drinking water and wastewater services.

Utilities that are unable to gather sufficient revenues from rate payers may not be able to repair or replace deteriorating infrastructure. For example, the drinking water system in St. Louis, Missouri uses some equipment from the early twentieth century, according to utility representatives. Representatives said that the system was built to serve a population of 1 million people, but the city’s population has declined over time to less than half that amount, with much of the remaining population having low incomes. As a result, city officials have been reluctant to raise rates, and revenue from rate increases has been used to pay for operations and maintenance rather than to purchase new infrastructure, according to representatives.

Failing to implement infrastructure upgrades can have catastrophic results. For example, officials from Jackson, Mississippi, said that their drinking water system failed during a period of heavy rain because the utility had not been able to update its infrastructure. Specifically, among other factors, the plant did not have backup pumps installed which could have provided additional capacity when its intake pumps became clogged with debris. It also did not have the technology to automatically measure and adjust the chemical composition of the water, according to utility representatives. As previously mentioned, Jackson’s water treatment plant failed following heavy rains and flooding in August 2022, leaving over 150,000 residents without potable water for more than 2 weeks. Parts of St. Louis’ and Jackson’s drinking water treatment plants are shown in figure 5.

Representatives from five of the 14 utilities we met with cited roadblocks to obtaining financing for infrastructure upgrades that can occur at the local level, such as local elected officials denying requests to increase the rates that community members pay to utilities. In addition, two representatives we spoke with said local officials might not approve proposed investments in water infrastructure because, among other factors, the results of such investments are not readily visible to the public.

Operations and Maintenance Costs

Representatives from three of the five technical assistance providers we spoke with said that the cost of routine operations and maintenance can also be a challenge for drinking water and wastewater utilities, particularly those in vulnerable communities.[46] Most of the financial assistance provided by federal agencies cannot be used for maintaining or operating this infrastructure. For example, the statutes authorizing EPA’s Drinking Water State Revolving Fund and Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act programs exclude operations and maintenance expenses from eligible uses of the financial assistance.[47] In addition, the statute authorizing EPA’s Clean Water State Revolving Fund program requires the applicant to have adequate provisions and plans approved by EPA and the state to ensure proper and efficient operation and maintenance after the financed project has been constructed.[48] Together, these three programs provided 74 percent of the total grant and loan amounts for drinking water and wastewater infrastructure from fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2023 across the 14 programs we reviewed that provided financial assistance during this period.

For some federal programs, EPA and USDA are authorized to provide financial assistance for certain operations and maintenance costs. For example, direct loan recipients for the USDA Water and Waste Disposal Loan and Grant Program can generally use loan funds for initial operating expenses for the financed project for up to 1 year if they are unable to pay these expenses.[49] In another example, EPA’s Midsize and Large Drinking Water System Infrastructure Resilience and Sustainability Program may award grants to a public water system serving communities with a population of 10,000 or more for the operation or maintenance of eligible infrastructure projects that increase the system’s resilience to natural hazards and extreme weather events, among other activities.[50] As of January 2025, EPA had not yet made any obligations for this program.

Affordability of Loan Repayments

|

Wastewater Treatment Plant Improvements Partially Funded by USDA Loan

In 2019, USDA provided assistance through its Water and Waste Disposal Loan and Grant Program to Secretary, Maryland, for improvements to a wastewater treatment plant. This plant also serves East New Market, Maryland. As of March 2024, USDA had obligated $7 million in grants and provided $1.1 million in loans for the project. Source: GAO photo; U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data. | GAO‑25‑107013 |

Representatives from eight of the 14 utilities we interviewed told us that loan repayments for water infrastructure—including repayments of loans available through revolving fund programs—can be costly for some communities to take on. For example, representatives we spoke with from a utility serving a community of fewer than 1,000 people told us that their community’s payments for a $1 million USDA loan for a new wastewater treatment plant represent a significant portion of the community’s entire budget.

In another example, a large municipal utility stated that the cost of its loan repayments disproportionately burdens vulnerable communities within their city because rates must be increased across the utility’s entire service area to cover loan repayments for multiple large capital projects. Further, representatives from another utility told us they had to “pick and choose” which projects and sources of financial assistance to pursue because of the high costs associated with their current federal loan repayment. As previously mentioned, 46 percent of the financial assistance we reviewed from fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2023 (about $29 billion) was from direct loan programs, and an additional $30 billion was from capitalization grant programs, which allow states to issue loans to eligible utilities.

EPA, USDA, and FEMA Took Steps to Address Barriers Faced by Vulnerable Communities, and FEMA Could Take Additional Steps

EPA, FEMA, and USDA have taken steps to address barriers that vulnerable populations may face in accessing and participating in selected programs that provide financial assistance for water infrastructure.[51] For example, all three agencies identified and addressed some barriers that may prevent vulnerable communities from fully benefitting from these programs. The agencies have also provided technical assistance to help potential applicants, including those in vulnerable communities, access and manage financial assistance. However, FEMA could communicate better about options for meeting cost-share requirements and could improve its assessment of program withdrawals.

EPA Took Steps to Address Barriers Faced by Vulnerable Communities

EPA identified barriers that may have prevented vulnerable communities—as defined by each of the programs we reviewed—from fully benefitting from certain programs.[52] Specifically, EPA documentation that we reviewed stated that vulnerable communities often lack technical, managerial, and financial capacity to apply for and implement its loan programs.

To address these barriers, EPA provided increased technical assistance. Technical assistance refers to programs, activities, and services provided by federal agencies to strengthen the capacity of grant applicants and recipients and to improve recipients’ performance of grant and loan functions. For example, in November 2022 EPA selected 29 technical assistance providers, called Environmental Finance Centers, to help vulnerable communities develop and submit project proposals, including for applications for EPA’s State Revolving Fund programs. See appendix V for a list of EPA, FEMA, and USDA programs that provide technical assistance to help communities apply for and manage financial assistance for drinking water and wastewater infrastructure.

In addition, when the Justice40 Initiative was active, EPA’s Drinking Water System Infrastructure Resilience and Sustainability program applied additional points to applications for proposed projects that would benefit certain types of communities.[53] For example, if the project would benefit underserved, small, and disadvantaged communities and would support the Justice40 Initiative, its application could have been awarded up to four points out of a total of 100 possible points.

FEMA Addressed Some Barriers That Vulnerable Communities Face but Could Improve Communication about Cost-Share Options

FEMA documentation identified several barriers that may prevent vulnerable communities from fully benefitting from the financial assistance programs we reviewed,[54] including:

· Some subapplicants lack the administrative capacity needed to complete the grant application process. For example, the environmental and historic preservation review process is complex, sometimes taking over a year to complete, even for well-resourced communities.[55]

· FEMA’s benefit-cost analysis requirement of its application process may be a barrier for communities with smaller populations, who may need assistance navigating the complexity required to complete the analysis and who often cannot reach the cost-effectiveness threshold requirement.[56]

· Vulnerable communities may lack funds to meet FEMA’s requirement for nonfederal cost share—the portion of the costs of a project not borne by the federal government.

Representatives from five of the 14 utilities we interviewed said cost-share requirements can be a challenge.[57] For example, representatives from one utility told us the cost share for a million-dollar infrastructure project could be more than the entire annual operating budget of a small town. We have previously reported that these issues pose barriers to participation in FEMA programs and that they may dissuade some applicants from seeking financial assistance from FEMA.[58]

To help address these and other challenges, FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program launched a technical assistance program in 2020.[59] This technical assistance program provided support from the pre-application through grant closeout phases, with a focus on supporting vulnerable communities.[60] One of the first communities to receive assistance was DePue, Illinois—a town with under 2,000 residents that experienced major flooding in 2008, causing raw sewage to back up into residents’ homes. Officials in DePue told us that FEMA’s technical assistance allowed DePue to complete plans for a project to relocate its current wastewater treatment plant—shown in figure 6—out of a floodplain, which would significantly mitigate the threat posed by floods. In fiscal year 2022, DePue submitted an application to FEMA for funding the relocation of this treatment plant, and FEMA subsequently awarded $23 million to DePue for this project. To further address challenges related to its benefit-cost analysis, in 2022 FEMA lowered the threshold for projects to be considered cost-effective if the project benefitted disadvantaged communities, among other criteria.[61] In June 2025, FEMA officials told us this lower threshold had been discontinued.

Source: GAO photo. | GAO‑25‑107013

To help address challenges related to cost share, FEMA modified cost-share requirements for certain types of recipients, consistent with statutory provisions. For example, the cost-share requirement for FEMA’s hazard mitigation assistance programs is generally 25 percent of a project’s cost. However, FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program had a cost-share requirement of 10 percent for Economically Disadvantaged Rural Communities and for projects within or primarily benefitting Community Disaster Resilience Zones.[62] For the Flood Mitigation Assistance program, FEMA may contribute up to 100 percent of project costs for severe repetitive loss structures and up to 90 percent of project costs for repetitive loss structures.[63] These options help FEMA fulfill the Stafford Act’s stated purpose of improving the natural hazard resilience of vulnerable communities.[64]

In addition, in certain circumstances, FEMA allows applicants to use funds from other federal programs to meet its cost-share requirements. For example, in 2019 FEMA and EPA established a memorandum of understanding stating that non-federal funds from state revolving funds may be used to meet cost-share requirements for FEMA programs if the activities are also eligible under the EPA programs.[65] Similarly, in October 2023 FEMA informed USDA that applicants for certain FEMA programs may use assistance from certain USDA programs to meet FEMA’s cost-share requirements for eligible water infrastructure projects.[66] These FEMA applicants seeking financial assistance from USDA programs must be rural communities and must meet other USDA eligibility requirements.

FEMA has communicated with potential applicants about some options for meeting cost-share requirements but has not adequately communicated about the option to use assistance from USDA programs. Specifically, FEMA’s 2016 guide on cost share for hazard mitigation assistance programs identifies several resources that applicants may use to meet cost-share requirements—including the nonfederal share of the state revolving funds—but it does not mention using assistance from USDA programs for water infrastructure projects. FEMA’s webpage about cost-share also does not contain this information. FEMA officials told us that as they learn of new sources of funds that may be used to meet cost-share requirements, they may add information about them to their guide on hazard mitigation programs. However, these officials did not reference specific plans to do so, nor did they mention plans to share this information through any other mechanism.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that agencies should communicate information externally so that external parties can help agencies meet their objectives.[67] Given that representatives from several of the utilities that we spoke with mentioned FEMA’s cost-share requirements as a barrier, it is possible that utilities and other potential program recipients are not aware of the full range of federal programs they can leverage to meet cost-share requirements. By communicating with potential applicants about the full range of federal programs, such as certain USDA programs, that applicants can use to meet cost-share requirements for FEMA hazard mitigation programs, FEMA would better ensure that it is minimizing the cost share barrier for small, rural communities.

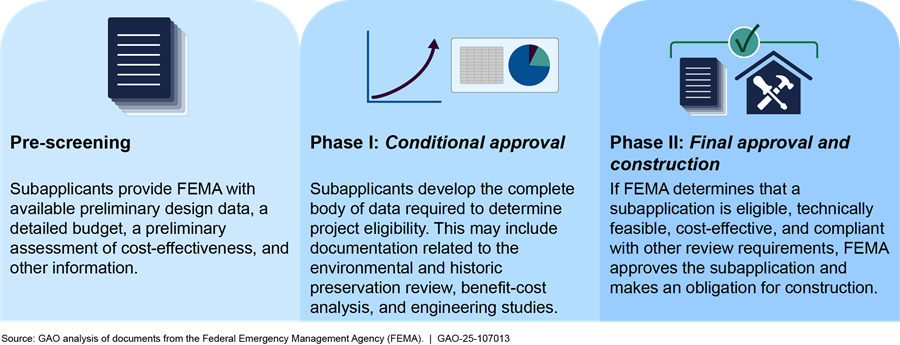

To further support applicants, FEMA offers the option to complete certain project application processes in phases. This process assists communities, including small communities, who lack technical and financial resources to provide the complete set of information required for complex project applications, according to FEMA documentation. A major benefit of this phased process is that FEMA awards grants and provides technical assistance to subapplicants to help them prepare certain technical and complex application materials, as identified in the “Phase I” portion of figure 7. Subapplicants are not required to refund FEMA for these costs if FEMA does not grant final approval for a project. FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program began offering the option for phased applications in its inaugural cycle in fiscal year 2020, and FEMA’s Flood Mitigation Assistance program began offering this option in fiscal year 2022.

Note: Phased projects are allowable under the following FEMA programs unless otherwise indicated in the notice of funding opportunity: Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, Hazard Mitigation Grant Program Post Fire, Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, and Flood Mitigation Assistance. FEMA awards grants to applicants, which are generally states, which then distribute the awards to subapplicants, such as local governments.

FEMA Does Not Systematically Collect Data on Program Withdrawals

Although FEMA has taken steps to address barriers faced by vulnerable communities, some subapplicants—including those from vulnerable communities—withdrew from the FEMA programs we reviewed after FEMA had selected their subapplications for further review. FEMA officials said that subapplicants might withdraw their subapplications for reasons such as losing cost-share funding, choosing to pursue financial assistance from a different program, or losing support for the project because of a change in local political leadership.

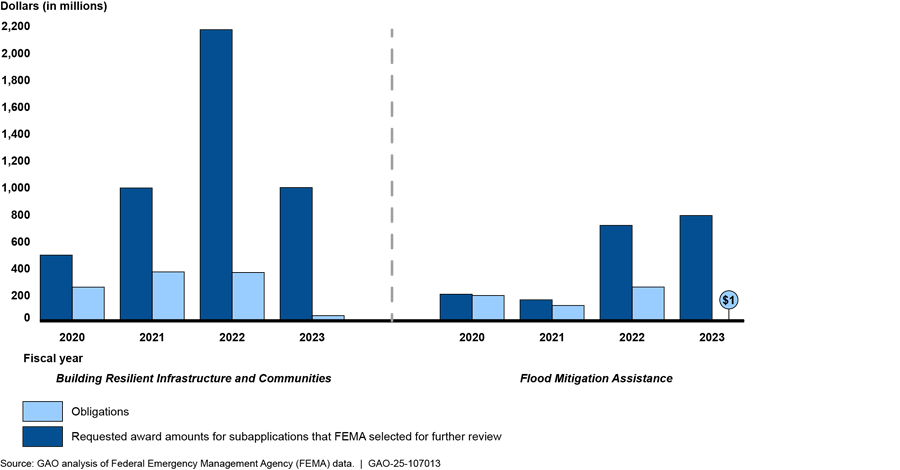

An August 2024 FEMA report states that many program stakeholders reported that the length of time from application to award was a significant barrier. In addition, the report describes feedback from one program stakeholder who stated that the length of time from application to final approval caused some subapplicants to withdraw their applications from one of FEMA’s programs.[68] Additionally, according to FEMA data, there may have been delays between when FEMA selected a subapplication for further review and when FEMA made obligations for that project. Specifically, as of March 2025, FEMA had obligated 22 percent of the award amounts for Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities subapplications that it had selected from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2023, as shown in figure 8. For FEMA’s Flood Mitigation Assistance projects, this figure was 30 percent.

Figure 8: FEMA-Selected Project Award Amounts and Obligations for FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities and Flood Mitigation Assistance Program Subapplications, Fiscal Years 2020–2023, as of March 2025

Note: This graphic depicts data as of March 2025 for subapplications for all types of projects, not just projects related to water infrastructure. The requested award amounts for subapplications that FEMA selected for further review may differ from final obligations because subapplicants may withdraw their applications or be found ineligible for financial assistance.

The FEMA hazard mitigation assistance programs we reviewed did not systematically track how many subapplicants withdrew from the programs prior to obligations being made or their reasons for withdrawal, according to a program official. FEMA officials said that program personnel sometimes add comments in FEMA’s grants management system to indicate that a subapplication was withdrawn. However, this comment field is associated with the field indicating that a subapplication was ineligible for funding and there is no field in the system specific to withdrawals. As a result, withdrawn subapplications appear as ineligible in FEMA’s system, thus overcounting ineligibility and providing no clear data on withdrawals, according to FEMA officials.

GAO’s Practices for Evidence-Based Policymaking says that federal agencies should generate evidence to help assess, understand, and identify opportunities to improve the results of federal efforts.[69] Such evidence should be complete and accurate enough to be able to provide insight into the extent to which the agency is meeting its goals. In addition, as previously mentioned, the Stafford Act calls for FEMA to improve the natural hazard resilience of vulnerable communities.

As previously discussed, vulnerable communities experience particularly pronounced barriers to completing FEMA hazard mitigation applications and meeting requirements for complex projects. These barriers may make vulnerable communities more likely to withdraw from the program than other communities. Generating more complete information about the extent to which subapplicants withdraw from the hazard mitigation assistance programs, and their reasons for withdrawal, could help FEMA identify and reduce barriers faced by program subapplicants, including vulnerable communities. This, in turn, could help improve the resilience of water infrastructure in vulnerable communities and elsewhere.

USDA Identified Barriers and Took Actions to Address Them

USDA identified barriers that vulnerable communities face through its Creating Opportunities through Rural Engagement initiative, created in November 2021. USDA created this initiative to engage with socially vulnerable, distressed, and underserved rural communities.[70] The barriers related to water infrastructure identified through this initiative include a lack of administrative capacity to apply for financial assistance, limited access to engineering firms, and a lack of capacity to manage the financial aspects of the program, according to USDA officials. USDA took actions to address these barriers, such as helping communities identify potential projects and connecting them with relevant financial resources, technical assistance, and partners. As of April 2024, USDA reported having engaged with nearly 700 communities through this initiative.

Other USDA initiatives aim to reduce barriers by providing technical and financial assistance to vulnerable communities and improving the grant application process. For example, in August 2022 EPA and USDA announced the Closing America’s Wastewater Access Gap Community Initiative.[71] This initiative provides no-cost technical assistance to help vulnerable communities identify and pursue financial assistance opportunities to address wastewater needs. Through this initiative, communities have received assistance performing rate studies to evaluate the feasibility of wastewater projects, identifying grants and financing options, and completing engineering and paperwork requirements for financial assistance applications. As of February 2025, this program had served 11 communities as part of a pilot program and planned to expand the initiative to serve 150 communities nationwide.

Further, USDA officials said they expect USDA’s Better Grants Better Service initiative to help reduce barriers for vulnerable communities because this initiative focuses on streamlining grant processes. For example, as of February 2025 this initiative had recommended that USDA revise and streamline certain grant program application forms, create an online grant administration portal and program search tool, and coordinate deadlines for grant programs. USDA’s ability to implement these recommendations is dependent on available resources, according to the initiative’s website.

Agencies Could Use Available Mapping Resources to Assess Program Beneficiaries

EPA, FEMA, and USDA used different measures and methods to assess the extent to which the benefits of selected programs reached vulnerable communities.[72] FEMA and USDA both assessed program beneficiaries using national measures. EPA used national measures for some programs and state-based measures for other programs. We analyzed data from two EPA programs and found statistically significant associations between certain characteristics of social vulnerability and the amount of financial assistance that communities received over a 10-year period. Using EPA’s mapping tool with drinking water service area boundaries could help EPA, FEMA, and USDA more accurately assess program results, including the extent to which program benefits reach vulnerable communities. In addition, when complete, a similar tool on wastewater service area boundaries could help these agencies assess the results of wastewater projects.

FEMA and USDA Used National Measures to Identify and Assess Program Beneficiaries

FEMA used various national measures to identify vulnerable communities and assess the extent to which program benefits went to these communities.[73]

Identifying vulnerable communities

· Some measures FEMA used to identify vulnerable communities are established in statute. For example—for the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program—FEMA is authorized by statute to identify Community Disaster Resilience Zones and Economically Disadvantaged Rural Communities and provide up to 90 percent of the cost share for projects benefitting these communities.[74] The Flood Mitigation Assistance program is authorized by statute—for amounts appropriated under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act for fiscal years 2022 through 2026—to use the Social Vulnerability Index to identify properties located within a vulnerable census tract.[75] FEMA is authorized to provide up to 90 percent of the cost share for projects benefitting these properties.[76]

· In fiscal years 2021 and 2022, to meet requirements for the Justice40 Initiative, FEMA used the Social Vulnerability Index to identify vulnerable communities. Specifically, FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program defined vulnerable communities as census tracts with a Social Vulnerability Index score of 0.6 or higher or Economically Disadvantaged Rural Communities. FEMA’s Flood Mitigation Assistance program defined vulnerable communities as property addresses within a census tract, or across multiple census tracts for certain projects, with a Social Vulnerability Index score of 0.5 or higher. Tribes and communities with census tracts that were designated as Community Disaster Resilience Zones were automatically considered to be vulnerable. FEMA officials said that in fiscal year 2023 they used the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, which was developed for the Justice40 Initiative, to identify vulnerable communities and to calculate the amount of program benefits that went to these communities.[77]

Assessing program beneficiaries

· From fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2023, FEMA calculated the total program benefits reaching vulnerable communities by multiplying the percentage of vulnerable census tracts (as defined by the measures described above) by the total preliminary award amount for each project. For example, if 80 percent of the census tracts benefiting from a project with a $1 million preliminary award were designated as vulnerable, FEMA officials would estimate that $800,000 of that award went to vulnerable communities.

· In March 2025, we asked FEMA officials whether they planned to use the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool going forward to identify and assess vulnerable program beneficiaries, given that the executive order that established the Justice40 Initiative was revoked in January 2025. As of May 2025, when we sent the report to FEMA for official comment, FEMA had not provided a response.

USDA also used various national measures to identify vulnerable communities and assess program beneficiaries.

Identifying vulnerable communities

· USDA used the Distressed Communities Index prior to and during the first 2 years of the Justice40 Initiative to identify vulnerable census tracts, according to USDA officials.[78] USDA officials said they shared this information with states and USDA field staff to target outreach and engagement with vulnerable communities.

· In fiscal year 2023, USDA officials used the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool to identify vulnerable census tracts, according to program officials.

Assessing program beneficiaries

· To assess the extent to which program benefits reached vulnerable communities, officials identified projects that received financial assistance and that involved construction or improvement of facilities with a health or sanitary component. Officials then summed the amount of financial assistance received by each facility that was located in a vulnerable census tract, as defined by the Distressed Communities Index or the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool.

· In March 2025, USDA officials said they do not plan to use the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool or any other tools to identify disadvantaged communities. However, as previously mentioned, various appropriation acts have required the USDA to allocate a certain amount of rural water and waste disposal financial assistance for persistent poverty counties, as defined by law.[79]

EPA Used State-Based and National Measures to Assess Program Beneficiaries

Four of the seven EPA programs we reviewed either used national measures to identify vulnerable communities and assess the extent to which program benefits reached them, or they did not conduct such an assessment because the program predominantly or exclusively benefitted vulnerable communities.

· Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program. The Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act of 2014, as amended, authorizes EPA to provide direct loans and loan guarantees to eligible borrowers for water infrastructure projects.[80] Under this program, EPA must use 13 selection criteria for evaluating and selecting among eligible projects to receive financial assistance, including the extent to which the project serves “economically stressed communities.”[81] This program uses standardized national measures, including median household income and poverty rate, to identify whether a prospective borrower is “economically stressed.”[82] The borrower as a whole would be designated as economically stressed—the program does not identify specific communities within the borrower’s area that are economically stressed, according to program officials. Officials said they use this information to track the extent to which vulnerable communities may have benefitted from the program.

· Drinking Water System Infrastructure Resilience and Sustainability program and Small, Underserved, and Disadvantaged Communities program. These two programs provide grants only to eligible public water systems that serve communities that are underserved and either small or disadvantaged, as determined by national measures established by law.[83] Therefore, program officials stated that all program benefits reached vulnerable communities. For both programs, the measures used to identify beneficiary communities include national safe drinking water standards, such as whether the community is served by a public water system that exceeds a regulatory maximum contaminant level.

· U.S.-Mexico Border Water Infrastructure Program. This program provides financial assistance for drinking water and wastewater infrastructure projects in both the U.S. and Mexico that are within 100 kilometers (62 miles) of the southern border.[84] Officials from this program said they do not assess the extent to which the program benefits vulnerable communities because nearly all communities that benefit from this program are vulnerable. According to program documents, this program provides financial assistance for underserved, small, and economically distressed border communities that have inadequate or no access to basic drinking water and sanitation.[85]

Three EPA programs that we reviewed used states’ data to identify vulnerable communities, including two revolving fund programs that provide capitalization grants to states, which then make low-interest loans or grants to local communities and utilities.

· Drinking Water State Revolving Fund. The statute authorizing this program defines a disadvantaged community as the service area of a public water system that meets affordability criteria established by the state in which that system is located.[86] EPA reported in 2022 on the variation in definitions of disadvantaged communities across states.[87] For example, this report stated that nearly all states used data on median household income to help identify disadvantaged communities, 27 states used data on water rates, and 16 states used data on water system size.[88] The program’s authorizing statute requires that states provide between 12 percent and 35 percent of their annual federal capitalization grant as additional subsidization for disadvantaged communities if the state receives sufficient loan applications from these communities.[89]

· Clean Water State Revolving Fund. The statute authorizing this program requires states to establish affordability criteria based on income and unemployment data, population trends, and other data determined relevant by each state to identify municipalities that would experience a significant hardship financing an eligible project if additional subsidization is not provided.[90] This program’s authorizing statute requires that states provide 10 percent to 30 percent of their annual federal capitalization grant as additional subsidies if the state receives sufficient applications for assistance from these communities and if EPA capitalization grants to all states for the fiscal year exceed $1 billion.[91]

· Sewer Overflow and Stormwater Reuse Municipal Grants program. This program provides grants to states, who then award competitive grants to municipalities for planning, design, and construction of treatment works to intercept, transport, control, treat, or reuse municipal combined sewer overflows, sanitary sewer overflows, or stormwater, among other eligible activities.[92] The statute authorizing this program requires states to give selection priority to “financially distressed community” applicants, defined as municipalities that meet affordability criteria established by the state.[93]

Officials from these three programs told us that they do not plan to use national data to assess the extent to which program benefits reached vulnerable communities. Officials from EPA’s Drinking Water State Revolving Fund and Clean Water State Revolving Fund programs said they believe states’ data are optimal for this purpose. Officials from EPA’s Sewer Overflow and Stormwater Reuse Municipal Grants program said states’ definitions and data contain valuable context that a federal definition may omit. Further, officials from EPA’s State Revolving Fund programs said that newly developed national datasets, such as the Water Infrastructure and Capacity Assessment Tool, can be used to generate assessments of the distribution of State Revolving Fund program benefits to communities nationwide.

Available Mapping Resources Could Help Agencies Assess Program Results

The three agencies have limited data on the geographical areas that are served by drinking water and wastewater utilities, which made it difficult to accurately identify which communities benefited from infrastructure projects, according to agency officials. For example, officials from one of the FEMA programs we reviewed said that they asked applicants to submit maps of projects’ benefitting areas as part of the 2023 application cycle, but these maps varied in quality. USDA officials said that a lack of data on service areas leads to inaccuracies in how USDA assesses the extent to which its projects benefit certain communities. As a result, USDA may be underreporting its overall investment in vulnerable communities, according to program officials.

Officials from one EPA program explained that a drinking water system service area may differ from the boundaries of a municipality, and both may differ from the boundaries of vulnerable communities. Specifically, officials said some applicants are large cities that have pockets or neighborhoods of populations that are vulnerable. However, because program officials do not have data on water system service areas, they assess the vulnerability of the applicant city as a whole. Such an assessment might not accurately represent the proportion of beneficiaries within the water system service area who are in vulnerable communities, as shown in figure 9.

Notes: This figure depicts a hypothetical example of how different geographical areas may or may not overlap. It does not represent an actual municipality or service area. The definition of “vulnerable community” varies across federal programs. Such communities may be referred to in statutes and program guidance as “disadvantaged,” “underserved,” “hardship,” or “rural,” among other designations.

In July 2024, EPA released a mapping tool with the geographical service area boundaries of community drinking water systems.[94] It contains the service area boundaries for around 99 percent of the population served by community water systems, according to EPA’s website. EPA officials said they are using a similar approach to develop a mapping tool for wastewater utilities’ service area boundaries, which they estimated would be complete in summer 2025.[95]

An EPA document identified potential uses for this tool, including:[96]

· identifying population groups that may be affected by threats to drinking water infrastructure, such as children, elderly, or low-income populations;

· evaluating and improving drinking water infrastructure planning, including determining grant eligibility and prioritization of state revolving fund allocation;

· analyzing natural disaster risks within a drinking water service area; and

· fostering interagency collaboration related to community water systems.

Officials from FEMA and USDA programs we reviewed said they did not use EPA’s drinking water mapping tool because they were not aware it existed. Once we informed FEMA officials about the drinking water tool and the planned wastewater tool, they said that using them may not be feasible because FEMA does not identify which of its hazard mitigation projects are intended to improve drinking water or wastewater infrastructure. We asked FEMA in March 2025 for more information about the feasibility of identifying water-related projects and using EPA’s mapping tools; as of May 2025, when we sent the report to FEMA for official comment, FEMA had not responded to our questions. Water infrastructure is one of 16 critical infrastructure sectors, meaning that it is “so vital to the U.S. that the incapacity or destruction of such systems and assets would have a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, [and/or] national public health or safety.”[97] Identifying projects that are related to drinking water and wastewater infrastructure—as well as using EPA’s mapping tools to determine which communities are benefitting from these investments, as described below—would enable FEMA to more accurately assess the agency’s investments in this critical infrastructure sector.

When we informed USDA officials about these tools, they expressed a concern that the methods EPA used to develop them might result in inaccurate service area boundary data for the rural communities USDA serves. However, the EPA officials that developed the drinking water service area tool said that the methodology they use performs well in small, rural areas because it is relatively easy to identify a community water system in such areas. This is because these areas are typically served by a single water utility and are spatially isolated from other community water systems and developed areas, simplifying their delineation and identification, according to EPA officials.

In addition, EPA officials said that a certain level of technical skill would be required to use the mapping tools to assess program beneficiaries. In May 2025, EPA officials pointed us to instructions on a public EPA website for federal agencies and other potential users on how to join census data with the service area data from the mapping tools.[98] Joining this data could help users more accurately assess the populations that could benefit or have benefitted from financial assistance, including the extent to which these populations are vulnerable, according to EPA officials. However, these officials said that the instructions alone likely would not be sufficient to enable users to perform such an analysis because each user has unique needs, and EPA could not address each of these needs in its written instructions. To bridge this gap, EPA officials said they provide individualized assistance to potential users of its mapping tools, such as other federal agencies, to help them use the tools to meet their specific needs. As of May 2025, information on how to contact the EPA officials who can provide such assistance was available on a public EPA webpage.[99]