NATIONAL NUCLEAR SECURITY ADMINISTRATION

Explosives Program Is Mitigating Some Supply Chain Risks but Should Take Additional Actions to Enhance Resiliency

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Allison Bawden at (202) 512-3841 or bawdena@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107016, a report to congressional committees

NATIONAL NUCLEAR SECURITY ADMINISTRATION

Explosives Program Is Mitigating Some Supply Chain Risks but Should Take Additional Actions to Enhance Resiliency

Why GAO Did This Study

NNSA is responsible for maintaining and modernizing the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile. The agency has ongoing and planned efforts to modernize our nation’s stockpile of weapons. NNSA also has plans for newly designed weapons. These efforts require producing new explosive components.

The report accompanying the Senate bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision that GAO assess NNSA’s explosives supply chain, infrastructure, and program management. This report examines: (1) the state of the explosives supply chain; (2) the state of explosives infrastructure; and (3) the extent to which NNSA’s explosives program manages supply chain risks to ensure resilience of the supply chain.

GAO reviewed NNSA documents and data, interviewed NNSA officials and contractor representatives, and conducted site visits to describe the supply chain and infrastructure, and assess the extent to which NNSA’s management of the explosives program is managing risk to ensure supply chain resilience. GAO conducted site visits to four of NNSA’s five key explosives sites.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to NNSA aimed at ensuring it fully or substantially establishes a process for supplier risk reviews, fully develops a resiliency strategy, and has a workforce trained to manage supply chain risks. NNSA agreed with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

According to National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) documentation, the explosives supply chain is vulnerable to risks, such as material supply and manufacturing challenges. GAO found 66 total NNSA-identified risks across the agency’s 11 key explosives products supply chains. Agency officials told us the risks facing the explosives program, if not addressed, could result in delays to nuclear weapons modernization programs and newly designed weapons. NNSA has taken some steps to mitigate these risks, such as maintaining stockpiles of at-risk materials and identifying new domestic suppliers.

NNSA’s nearly $4 billion of existing explosives infrastructure—at five contractor-operated sites that design, produce, and test high explosives—is also facing risks. These include aging facilities, a changing regulatory environment, and budgetary constraints. To mitigate these risks, NNSA is pursuing improvements to some of its explosives infrastructure, including planning between $1 and $2 billion for major construction projects over the next decade, as well as investment in minor construction and recapitalization projects. However, NNSA has paused some of these projects, including two major projects, because of other agency priorities.

GAO found that NNSA’s explosives program generally followed supply chain risk management leading practices. Specifically, NNSA fully or substantially followed five out of eight leading practices and partially followed three. For example, consistent with leading practices, NNSA developed an agencywide supply chain risk management strategy. However, NNSA has not developed a resiliency strategy—a strategy to ensure the supply chain is flexible and adaptable enough to mitigate future adverse events—that comprehensively covers all identified risks. Rather, its strategy covers a more limited set of risks associated with infrastructure and sole-source suppliers. Fully following these risk management practices would help NNSA improve future supply chain resiliency.

|

Leading practice |

Extent followed |

|

|

Establish executive oversight of supply chain risk management activities |

● |

|

|

Develop an agencywide supply chain risk management strategy |

● |

|

|

Establish a process to identify and document agency supply chains |

● |

|

|

Establish a process to conduct agencywide assessments of supply chain risks |

● |

|

|

Establish a process to conduct risk reviews and develop requirements of suppliers |

◒ |

|

|

Develop a resiliency strategy to ensure future supply |

◒ |

|

|

Develop a skilled workforce to manage supply chain risks |

◒ |

|

|

Establish interagency coordination and collaboration on strategic supply chain risks |

● |

|

Legend:

● = Fully or substantially followed—NNSA took actions that addressed most or all aspects of the key questions GAO examined for the practice

◒ = Partially followed—NNSA took actions that addressed some, but not most, aspects of the key questions GAO examined for the practice

○ = Not followed—NNSA did not take actions that addressed aspects of the key questions GAO examined for the practice

Source: GAO analysis of National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) documents and interviews. | GAO-25-107016

Abbreviations

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

HESFP |

High Explosives Synthesis, Formulation, and Production facility |

|

LLNL |

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory |

|

LANL |

Los Alamos National Laboratory |

|

LRSO |

Long Range Standoff weapon |

|

NNSA |

National Nuclear Security Administration |

|

NNSS |

Nevada National Security Site |

|

PNNL |

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory |

|

STRATCOM |

U.S. Strategic Command |

|

TATB |

Triaminotrinitrobenzene |

|

TCTNB |

Trichlorotrinitrobenzene |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

March 12, 2025

Congressional Committees

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA)—a separately organized agency within the Department of Energy (DOE)—is responsible for, among other things, maintaining and modernizing the United States’ nuclear weapons stockpile. NNSA has ongoing and planned efforts to modernize nearly all of its weapons and has plans for newly designed weapons, as well. These efforts will require new explosive components.[1] Explosives serve many functions in nuclear weapons, including creating an implosion that compresses the plutonium core of the weapon, starting the chain of fission nuclear reactions.

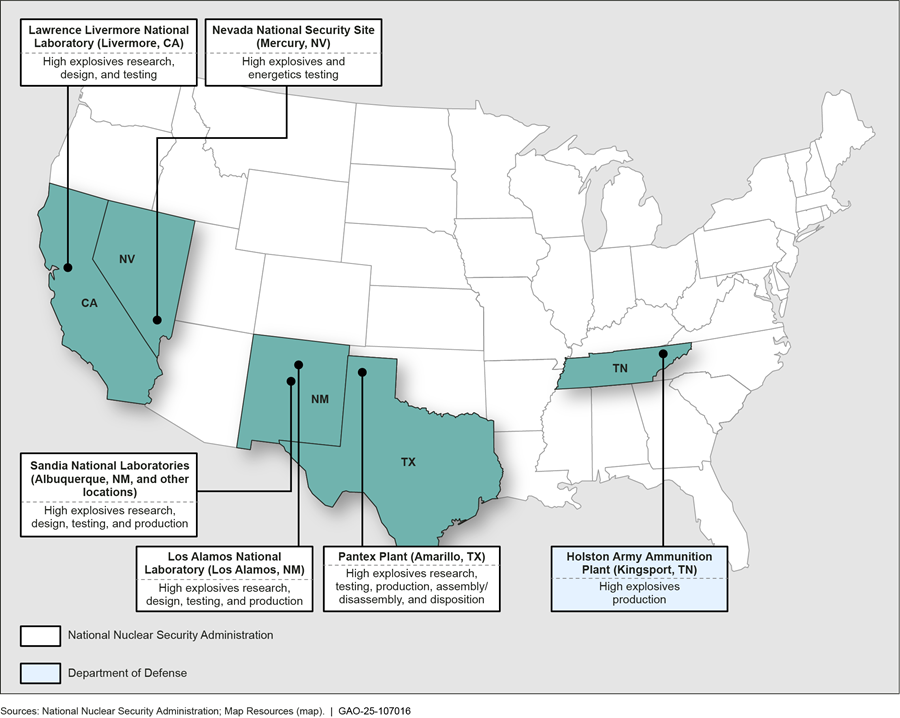

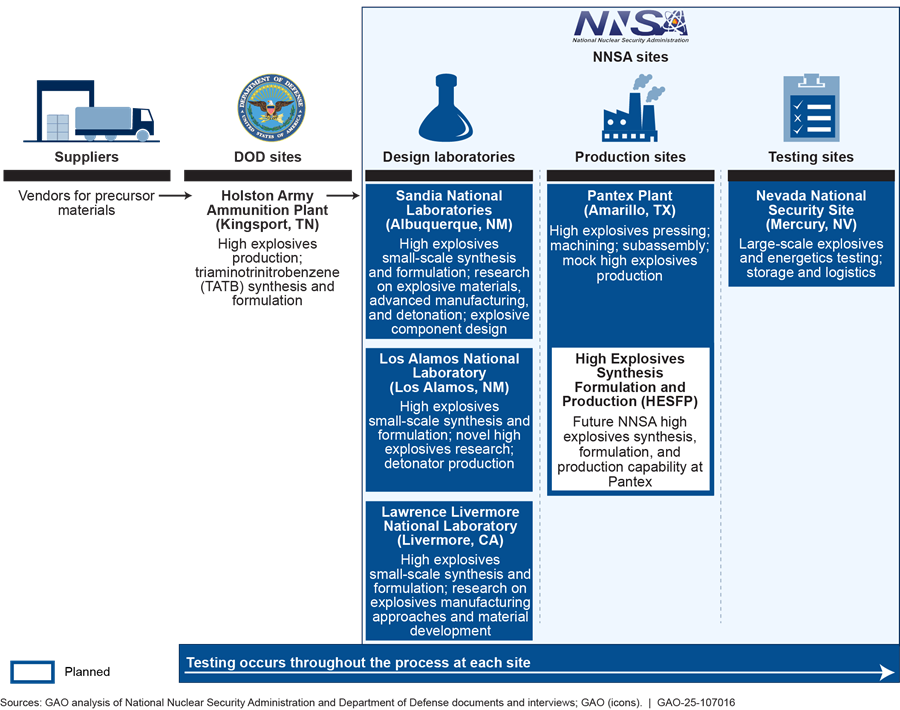

NNSA’s High Explosives and Energetics Program Office is responsible for ensuring a sufficient and reliable supply of explosives for the stockpile as well as coordinating explosives activities across the nuclear security enterprise.[2] Five of the NNSA contractor-operated sites in the enterprise conduct activities to design, produce, and/or test explosive materials or components: (1) Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL); (2) Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL); (3) the Nevada National Security Site (NNSS); (4) the Pantex Plant (Pantex); and (5) Sandia National Laboratories (Sandia). Each site assumes primary responsibility for certain activities, but most activities require collaboration across multiple sites. According to NNSA, the explosives supply chain across these sites is fragile, inadequate, and vulnerable to disruption.

In addition, one Department of Defense (DOD) site—the Holston Army Ammunition Plant (Holston)—is currently NNSA’s major supplier of certain explosives materials. However, Holston’s primary client is DOD. According to NNSA officials, Holston and NNSA are challenged to meet increasing demand for explosive material, especially as demand is at an all-time high because of U.S. support to Ukraine and the nuclear stockpile refurbishment mission. In addition, some material Holston has produced has not ultimately met NNSA’s specifications. To diversify its supplier base, NNSA is currently working with DOD to develop a new explosives capability at another DOD location.[3] NNSA also engages with the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), a DOE laboratory overseen by the department’s Office of Science, to help identify and analyze explosives supply chain issues.

In June 2019, we found that NNSA faced several challenges to its explosives activities, including the agency’s dwindling supply of explosive materials, aging and deteriorating infrastructure, and difficulty recruiting and training qualified staff.[4] Since that time, NNSA has taken steps to improve the management of explosives activities, including establishing its High Explosives and Energetics Program Office as a centralized program office.

Further, NNSA is in the process of updating or replacing several World War II-era facilities related to explosives at each of the five sites active in the program. At Pantex, for example, NNSA planned to replace several aging explosives facilities with the High Explosives Synthesis, Formulation, and Production (HESFP) facility, which completed final design work in June 2023. However, due to budget concerns, including cost increases, competing priorities, and schedule delays for other major construction projects, in fiscal year 2023, NNSA postponed construction of HESFP (though work on the facility subsequently resumed), as well as two other explosives facilities at LANL.[5]

The report accompanying the Senate bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to assess NNSA’s explosives supply chain, infrastructure efforts, and program management approach.[6] Our report (1) describes the state of the explosives supply chain; (2) describes the state of NNSA’s explosives infrastructure and site projects; and (3) assesses the extent to which NNSA’s explosives program manages risks to ensure supply chain resilience.

To address all three objectives, we conducted site visits to four of the five key NNSA sites involved in explosives research, development, and production—LLNL, LANL, Pantex, and Sandia—and two DOD sites. We selected these sites because they conduct or are expected to contribute significantly to nuclear security enterprise explosives activities. We interviewed NNSA and DOD officials and contractor representatives on these site visits and in follow-up meetings about current explosives activities and future plans related to the supply chain, infrastructure, interagency coordination, and the overall management of NNSA’s explosives activities.

To describe the state of the explosives supply chain, we reviewed agency documents and interviewed NNSA and contractor representatives to identify risks facing the explosives supply chain. We also reviewed and analyzed NNSA’s supply chain documentation for all of the 11 explosives products for which NNSA has created supply chain maps and risk registers. Specifically, we analyzed the documents to categorize the types of supply chain risks NNSA has identified as part of characterizing the overall state of the supply chain.

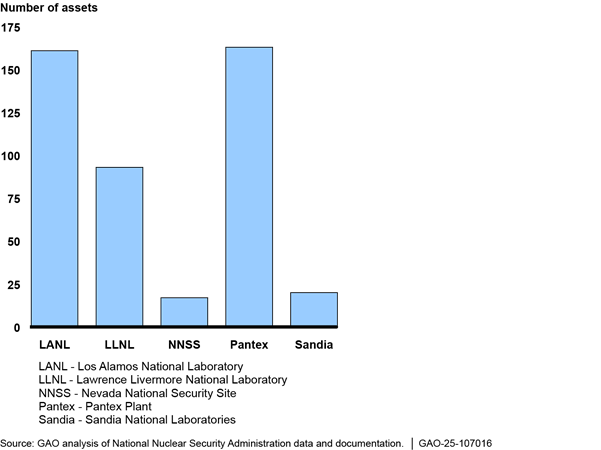

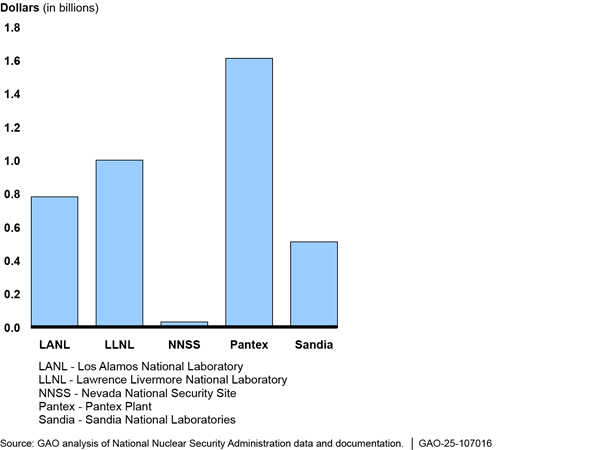

To describe the state of NNSA’s explosives infrastructure and site projects, we reviewed and analyzed infrastructure data and documents from NNSA and its contractors. Specifically, we analyzed the data to determine the total number of explosives-related infrastructure assets as of fiscal year 2024 and those assets’ total replacement plant value, and to verify trends described by NNSA and contractor representatives during interviews and site visits. We took steps to ensure the reliability of these data and found them to be sufficiently reliable to describe the state of the explosives supply chain.

To assess the extent to which NNSA’s explosives program manages risks to ensure supply chain resilience, we first identified eight leading practices for supply chain risk management and resilience. The leading practices, which we have previously relied on to assess supply chain risks for information technology and semiconductors, were derived from National Institute of Standards and Technology guidance applicable to federal agencies, including DOE, as well as an extensive literature review and interviews with industry executives, government officials, and representatives from academia and nonprofits.[7] We previously found that implementing supply chain risk management allows agencies to assess threats and opportunities that could affect the achievement of its goals.[8] Further, the 2021 Executive Order on America’s Supply Chains identifies the need to strengthen the resilience of America’s supply chains.[9] The term supply chain resilience can refer to the ability to prepare for anticipated choke points, adapt to changing conditions, and withstand and recover rapidly from disruptions.[10] We validated the supply chain risk management and resilience leading practices we identified with internal subject-matter experts, as well as relevant NNSA officials. We incorporated any relevant changes into the best practices as a result of these discussions. We then developed interview questions designed to assess the extent to which NNSA’s management of its explosives supply chain followed these practices and used these questions as the basis for interviewing knowledgeable NNSA officials. For more information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. These standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

We are separately issuing a controlled unclassified information annex to this report that provides additional details on certain supply chain risks and further technical detail on specific risks.[11] The annex will be available upon request to those with the appropriate and validated need to know.

Background

Explosives in Nuclear Weapons and Production

Explosives are an essential component of nuclear weapons, serving functions in the main charge and detonators, among other things.[12] Within the main charge of a nuclear weapon, high explosives compress the nuclear (plutonium) core, or pit, to start a nuclear reaction. There are two types of high explosives utilized in nuclear weapons pits: conventional high explosives and insensitive high explosives. Though conventional high explosives meet all safety requirements, insensitive high explosives offer additional safety benefits as they are less susceptible to accidental detonation and are less violent upon accidental ignition. As a result, nuclear weapons designed to use insensitive high explosives are considered to have a safety benefit, particularly with respect to explosive operations, production, transportation, and storage of these weapons. However, there are tradeoffs to using insensitive high explosives in comparison to conventional high explosives that may make one or the other more desirable for a specific weapon’s design.

The main explosive molecule utilized in U.S. insensitive high explosives is triaminotrinitrobenzene (TATB). TATB is an insensitive high explosive utilized in NNSA and DOD applications. Holston produces new TATB for use by DOD and NNSA.

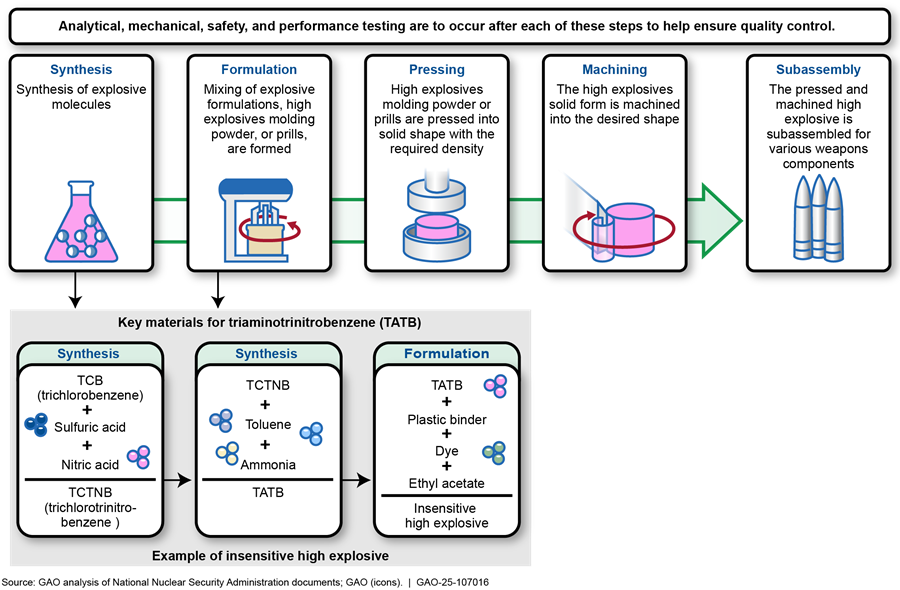

High explosives production for NNSA’s nuclear weapons generally follows five steps: (1) synthesis; (2) formulation; (3) pressing; (4) machining; and (5) subassembly (see fig. 1). Specific materials used in insensitive high explosive synthesis and formulation are also depicted in figure 1.

Synthesis. Chemicals are combined to produce raw explosive molecules. For example, to create TATB, trichlorobenzene, sulfuric acid, and nitric acid are first combined to form trichlorotrinitrobenzene (TCTNB). The TCTNB is then synthesized with ammonia and toluene to create TATB. Some critical technical aspects of synthesis that are difficult to specify to ultimately meet NNSA qualification requirements are particle size, purity, and surface area, according to NNSA documentation.

Formulation. The raw explosives are mixed with a plastic binder and other ingredients to create an explosive mixture in the form of an explosive molding powder or irregularly shaped pebbles, known as prills. For example, to create an insensitive high explosive, raw TATB molecules are formulated with a plastic binder, ethyl acetate, and a dye. Some critical technical aspects of formulation that are difficult to specify to ultimately meet NNSA qualification standards are binder distribution, binder properties, and surface texture, according to NNSA documentation.

Pressing. The formulated high explosive is compacted into a solid form to compress the explosive into a solid shape with required density.

Machining. Equipment is used to cut and shape the pressed explosive into a desired shape.

Subassembly. Explosives and non-explosives parts are joined.

Analytical, mechanical, safety, and performance testing occur after each step of the production process.[13]

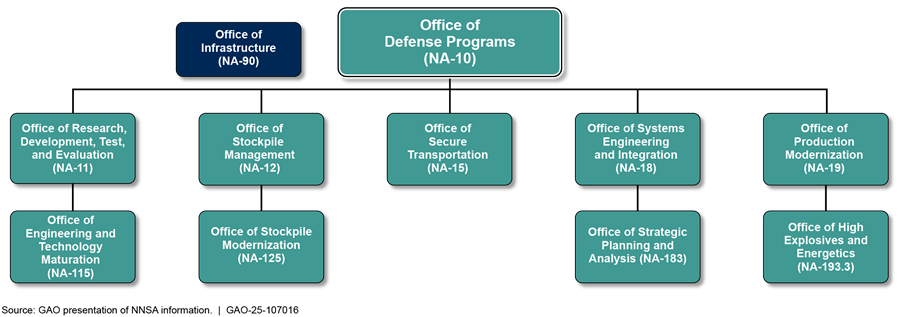

NNSA Offices Responsible for Explosives Activities

NNSA’s explosive activities primarily fall under the Office of Defense Programs. Figure 2 shows the main offices under NNSA’s Office of Defense Programs and the offices primarily responsible for managing and overseeing NNSA’s explosives activities.

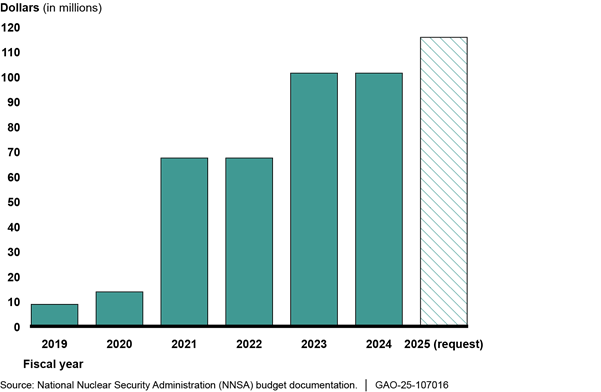

Within the Office of Defense Programs, the Office of High Explosives and Energetics under the Office of Production Modernization is the lead program office responsible for ensuring a sufficient supply of explosives for the nuclear security enterprise. Specifically, the Director of the Office of High Explosives and Energetics is the Energetics Materials Manager for the Office of Defense Programs. The three main roles and responsibilities of the Office of High Explosives and Energetics are (1) providing qualified explosives material for stockpile modernization,[14] (2) ensuring reliable explosives supply chains, and (3) infrastructure modernization, according to NNSA officials and documentation. NNSA established the Office of High Explosives and Energetics in October 2019 to centralize and coordinate enterprise-wide explosives activities. The Office of High Explosives and Energetics had a budget of $101 million in fiscal year 2023 and fiscal year 2024 (see fig. 3). NNSA’s budget justification for fiscal year 2025 included the President’s request for about $116 million.

Figure 3: National Nuclear Security Administration High Explosives and Energetics Office Budget (in Millions), Fiscal Years 2019–2025

Other offices within the Office of Defense Programs have roles in explosives activities. For example, the Office of Stockpile Modernization sets the demand signal for the materials’ explosive requirements, according to NNSA officials we interviewed. The Office of Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation provides novel explosive molecules, formulation methodologies—including binders—and manufacturing methodologies to address stockpile concerns. According to officials, the Office of Engineering and Technology Maturation is currently researching and developing new formulations and mixtures for binders and additively manufactured high explosives, leveraging the labs’ expertise to mitigate supply chain disruptions affecting the stockpile. In addition, the Office of Strategic Planning and Analysis conducts analyses of NNSA’s industrial base and has helped the Office of High Explosives and Energetics explore the viability of new suppliers, NNSA officials said. The Office of Infrastructure also has a role in explosives activities, specifically in managing explosives infrastructure construction, operation and maintenance, and recapitalization efforts.

NNSA’s High Explosives Supply Chain

NNSA oversees eight sites run by management and operating contractors, which constitute the nuclear security enterprise. NNSA’s explosives activities operate across five of the eight NNSA sites and two DOD sites, each of which assumes primary responsibility for certain explosives activities (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: National Nuclear Security Administration and Department of Defense Sites Related to Nuclear Weapons Explosives Activities

The laboratories—LLNL, LANL, and Sandia—conduct research and design activities, as well as testing of explosive materials.[15] For example, LLNL and LANL are actively developing new explosives targeted to meet NNSA mission requirements. Sandia conducts research and development on a variety of explosive materials and components. For example, it conducts electrostatic discharge testing of explosive materials to ensure the materials’ safety for handling (see fig. 5). Pantex and NNSS are the production and testing sites, respectively, involved with explosive activities. Pantex is the large-scale production agency for high explosives production and component manufacturing.[16] NNSS is a high hazard explosive testing site that supports labs’ design work through weapons-integrated experimentation and testing.

In addition to NNSA and DOD sites, NNSA relies on a limited industrial base of suppliers and manufacturers, including commercial vendors, for precursor materials. As depicted in Figure 6, precursor materials from suppliers often pass through Holston for explosives design and production at NNSA sites.

Figure 6: National Nuclear Security Administration and Department of Defense Sites Involved in Explosives Supply Chain

NNSA uses explosives manufactured by Holston. Pantex receives explosives from Holston to test, press, machine, and assemble explosive weapons components. To diversify its supplier base, NNSA is planning to stand up an additional insensitive high explosive production capability at another DOD site and, eventually, the HESFP facility at Pantex. Testing on explosive materials and components occurs throughout the design and production processes at each of the sites. Explosives activities often require coordination between multiple sites.

NNSA’s Existing and Planned Explosives Infrastructure

NNSA explosives infrastructure includes about 450 physical assets across the enterprise.[17] Explosives infrastructure assets include multifunction research or laboratory buildings, production facilities, machining and pressing facilities, materials handling facilities, and hazardous storage facilities, among others. The site with the highest number of assets related to high explosives is Pantex with 163 assets, followed by LANL with 161 assets, and LLNL with 93 assets (see fig. 7).

Figure 7: Number of National Nuclear Security Administration’s Existing Explosives Assets by Site, as of December 2024

These roughly 450 assets have a replacement plant value of nearly $4 billion, according to NNSA data and documentation.[18] The explosives infrastructure at Pantex had the highest total replacement plant value at $1.6 billion (see fig. 8).

Figure 8: Replacement Plant Value of Existing National Nuclear Security Administration Explosives Infrastructure by Site, as of December 2024

To support NNSA’s planned stockpile modernization efforts, NNSA is simultaneously executing major, line-item construction projects, minor construction projects, and other recapitalization efforts, some of which are also intended to modernize its high explosives infrastructure.[19]

Major projects. Across the enterprise, NNSA is designing, constructing, or completing closeout activities for 28 major projects, which individually have an estimated cost of $100 million or more. NNSA must identify each individual major, line-item construction project in its budget justification for congressional authorization and appropriation.

Minor projects. In addition to major projects, NNSA carries out more than 100 minor construction projects across several programs each year at its eight nuclear security enterprise sites.[20] These projects include additions, new or replacement facilities, and installations or upgrades that do not change a facility’s footprint. The minor construction threshold—currently $34 million—limits what NNSA can spend on each of these projects.[21] The funds for minor construction projects are to come from general funds (such as operations and maintenance funds) that are available within a program office’s budget rather than from funds authorized by Congress for specific line-item construction projects. In addition, NNSA officials have reported that they have more flexibility to start new minor construction projects compared with line-item construction projects under a continuing resolution. The Offices of Infrastructure and Defense Programs carry out most of NNSA’s minor construction projects.

Recapitalization. NNSA also undertakes recapitalization projects, such as replacement of building systems or enabling utilities to modernize and sustain its infrastructure. Recapitalization projects are mostly funded by the Office of Infrastructure.

NNSA’s Ongoing and Planned Weapons Modernization Programs

NNSA is spending billions of dollars on ongoing and planned weapons modernization programs over the next several decades. To modernize its weapons systems, NNSA had five Life Extension Programs (LEPs) and weapons modernization programs ongoing as of 2024, as shown in table 1.[22]

Table 1: National Nuclear Security Administration Weapons Modernization Programs and Associated Explosive Type

|

Program |

Description |

Explosive type |

|

Programs in production, as of December 2024 |

|

|

|

B61-12 LEP |

Addresses multiple components of the gravity bomb that are nearing end of life in addition to military requirements for reliability, service life, field maintenance, safety, and use control. Includes refurbishment of nuclear and non-nuclear components. Will replace and extend the service life of three variants (B61-3, B61-4, B61-7) of the original B61 bomb. |

TATB-based insensitive high explosive |

|

W88 Alteration 370 Programa |

Modernizes the warhead’s arming, fuzing, and firing subsystem; improves surety; replaces the conventional high explosive and associated materials; and incorporates additional components. |

Conventional high explosive |

|

Programs in design, as of December 2024 |

|

|

|

W80-4 LEP |

Warhead will deploy with the Air Force’s upcoming AGM-181 Long Range Standoff (LRSO) cruise missile and replace the aging AGM-86 air-launched cruise missile and the W80-1 warhead. The LRSO is intended to improve the Air Force’s ability to defeat an adversary’s integrated air defense systems by improving the bomber force’s delivery and survivability capabilities. |

TATB-based insensitive high explosive |

|

W87-1 Modification Program |

Warhead will be deployed alongside the legacy W87-0 on the LGM-35A Sentinel missile, formerly known as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent, which replaces the legacy Minuteman III missile. Includes updates to nuclear, safety, and nonnuclear components. The W87-1 will replace the aging W78 warhead. |

TATB-based insensitive high explosive |

|

W93 Program |

As a new warhead, it is intended to reduce the Navy’s reliance on the recently modernized W76 warhead, which accounts for a large portion of U.S. deployed nuclear weapons. It is planned to incorporate modern technologies to improve safety, security, and flexibility to address future threats and will be designed for ease of manufacturing, maintenance, and certification. This program will also support the United Kingdom’s nuclear deterrent. |

Conventional high explosive |

Legend:

LEP = Life Extension Program

TATB = triaminotrinitrobenzene

Source: National Nuclear Security Administration documentation. │ GAO‑25‑107016

Notes: Weapons that have certain engineering requirements because they must interface with a launch or delivery system are called warheads and are signified by a W (e.g., W88). Weapons that do not have these interface requirements, such as gravity bombs and atomic demolition munitions (now retired), are called bombs and are signified by a B (e.g., B61).

In addition to the weapons described in the table, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 authorizes two additional nuclear weapon acquisitions. Pub. L. No. 118-31, 1640, 4701, 137 Stat. 136, 595, 924 (2023). According to DOD, the B61-13 is intended to replace some of the B61 variants (B61-7) in the current stockpile, and some of the previously planned production quantity of the B61-12, as well as provide an option to address harder and large area military targets. In testimony before Congress, officials from DOD and NNSA have said that initial activities are underway to explore options for the nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile including whether to develop a variant of the W80-4 warhead for the weapon or pursue a different option.

aAn alteration is a material change to a nuclear weapon or its components that does not alter the weapon’s operational capability. Minor alterations are typically limited in scope and are not considered modernization programs; however, major alterations, such as the W88 Alteration 370, are more akin to a Life Extension Program, which is a refurbishment intended to extend the lifetime of a weapon for an additional 20 to 30 years.

Currently, three weapons modernization programs rely on insensitive high explosives formulated using TATB. To meet near-term modernization production schedules for the B61-12 and W80-4, NNSA is currently allocating its legacy supply of TATB to allow for sufficient time to qualify the new production processes for TATB-based formulations out of Holston and the new DOD site, officials said.

NNSA’s Explosives Supply Chain Faces Risks That NNSA Has Made Some Progress Mitigating

NNSA’s explosives supply chain is vulnerable to potential disruptions from risks such as material supply risks, manufacturing risks, and infrastructure risks. NNSA has taken some actions to mitigate these risks, including identifying new suppliers and developing new production processes. In addition, NNSA is working to mitigate supply chain risks specific to its insensitive high explosives supply chain, including by working with DOD to have a new facility built, conserving material, and better defining its requirements. If NNSA’s mitigation efforts are unsuccessful, these risks could affect ongoing and planned weapons modernization programs, according to NNSA documentation and DOD officials we interviewed.

NNSA’s Explosives Supply Chain Faces Numerous Risks

NNSA, in coordination with involved labs, plants, and sites, has identified numerous risks across 11 key explosive product supply chains. NNSA’s December 2022 High Explosives and Energetics Risk Management Plan categorizes supply chain risks as either a threat or an opportunity. Opportunities are positive events that NNSA should attempt to maximize. Threats are adverse events impacting the cost, schedule, or technical scope of a program’s activities. In addition to threats, issues have a 100 percent likelihood of impacting a program’s objectives, with either detrimental or beneficial impacts. These risks—specifically threats and issues—if realized, have the potential to cause failures in the supply chain that could suspend production of a given explosives material or component.

Across the 11 supply chains, we found NNSA’s most recent risk documentation available at the time of our review identified 66 total risks (64 total threats, two issues, and zero opportunities). Of the 66 total risks, we found that the risks fell under three general categories: (1) material supply risks, (2) manufacturing risks, and (3) infrastructure risks—all of which could disrupt the production of some explosives (see table 2). Additional details including information on the two supply chain issues NNSA identified are provided in a controlled unclassified information annex to this report.[23]

|

Category of risk |

Definition |

Presence in number of supply chains (out of 11) |

|

Material supply risks |

All risks under this category involve a risk with a material that may make it unavailable |

|

|

Procurement risk |

A risk related to the search and qualification of a new vendor |

8 |

|

Foreign supplier risk |

A vendor NNSA relies on to obtain a material is foreign-owned or has a foreign base of operations |

7 |

|

Legacy material risk |

A material is running out or has already run out because legacy stock was used |

6 |

|

Sole-source supplier risk |

Only one vendor is available to supply the material to NNSA |

6 |

|

Single supplier risk |

NNSA is only using one supplier but there are potentially other suppliers available for the material |

5 |

|

Manufacturing risks |

All risks under this category involve a risk with a step in the production process |

|

|

Testing requirements risk |

A product is not meeting quality requirements or other performance metrics |

7 |

|

Operational delay risk |

Production is at risk of being slowed because of capacity constraints or misunderstood demand signals |

7 |

|

Legacy process risk |

A new process is needed for a step in the production of a high explosive because the legacy process is not well understood |

4 |

|

Infrastructure risks |

All risks in this category involve a risk with equipment or facilities |

|

|

Equipment risk |

Equipment is antiquated, or difficult to maintain or replace, or has other maintenance needs |

7 |

|

Facility risk |

A facility is aging or deteriorated or has other maintenance needs |

3 |

Source: GAO analysis of National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) documentation. │ GAO‑25‑107016

· Material supply risk. Risks associated with certain suppliers and their ability to provide material that meets rigorous specifications can result in material supply shortages that disrupt explosives’ production. These risks include procurement risks related to qualifying new vendors,[24] the dependability of foreign suppliers, a reliance on legacy materials to meet specifications, single suppliers, and sole-source suppliers.[25] For example, we found that eight out of 11 explosives supply chains involve a precursor material that is at risk of being unavailable in the future because of challenges to NNSA identifying and qualifying a new vendor. NNSA’s process for identifying new suppliers and bringing them online includes a qualification process that often begins after the current supplier fails to provide material. However, if new suppliers are not identified early enough, it can disrupt material supply. In one example, NNSA is searching for a material that is chemically close to a legacy material but will need time to qualify a new vendor. Additionally, we found that seven out of 11 explosives supply chains rely on foreign-owned suppliers or suppliers with production operations based in foreign countries. Foreign suppliers present a risk if a geopolitical situation affects international commerce (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic), resulting in material supply disruptions, or if a potentially adversarial country decided to cut off NNSA’s supply of the material.

· Manufacturing risk. Manufacturing risks can disrupt the production of certain explosives. These risks include testing requirements, operational delays, and legacy processes. For example, we found seven out of 11 explosives supply chains experienced difficulty with the explosive product itself not meeting testing requirements. If the materials or product are not testing to the required specification at any time in the production process, NNSA has to rework the material or adjust the specifications, both of which can be time-consuming processes that carry their own risks. Additionally, we found that seven out of 11 explosives supply chains faced risks due to operational delays. In one instance, a component required for qualification of an explosive has a long production lead time and failure to accurately assess or anticipate the date by which the component would be needed could lead to delays in qualifying the explosive.

· Infrastructure risk. Infrastructure risks, including facility and equipment risks, have the potential to disrupt the production of certain explosives because a specific tool or building used in the production of an explosive may be unavailable due to age, safety, or maintenance issues. We provide additional information on specific facility and equipment risks NNSA is experiencing later in this report.

NNSA Is Working to Mitigate Supply Chain Risks

NNSA is taking steps to mitigate supply chain risks stemming from material supply risk and manufacturing risk. These steps include: (1) identifying and developing potential new domestic suppliers and conserving and stockpiling remaining legacy material; and (2) developing new production processes, respectively. We discuss the steps NNSA is taking to mitigate infrastructure risks later in the report.

· Identifying and developing new suppliers and stockpiling material. To mitigate the risks posed by some specific material supply chain risks, NNSA is working to identify and develop potential U.S.-based vendors for materials and is stockpiling legacy material. In several instances, NNSA has begun the process to find and qualify a new vendor for a given material but has encountered hurdles in the process. For example, NNSA is identifying new domestic vendors for a precursor material that currently is sourced from a foreign country, but, according to NNSA officials, the qualification process is lengthy and ongoing. NNSA is also conserving and stockpiling remaining legacy material, as well as purchasing reserve material in bulk. For example, NNSA plans to purchase additional reserves of a material currently sourced from a foreign supplier to keep as a backup ahead of eventually replacing the supplier with a U.S.-based supplier.

· Developing new production processes. To mitigate manufacturing risks, NNSA is also researching and developing new production and testing methods for several precursor materials and final explosives. Production process development can include reworking materials to meet specifications or, in some cases, rewriting the specifications themselves to ensure producibility. In the case of legacy products and processes, NNSA sites are exploring new production methods, sometimes with the help of suppliers. For example, several NNSA sites are working to finalize a joint specification for a precursor material used in one explosive production supply chain.

NNSA Is Working to Mitigate Specific Supply Chain Risks Related to Insensitive High Explosives That Could Affect Weapons Modernization Programs

NNSA currently faces specific near-term risks in producing and supplying insensitive high explosives.[26] Specifically, the production of insensitive high explosives used in certain nuclear weapons systems faces supply chain risks associated with the production and supply of TATB, the explosive molecule utilized in all U.S. war reserve insensitive high explosives. NNSA identified the risks facing the TATB supply chain as one of two issues that have a 100 percent likelihood of impacting the explosives program’s objectives.[27] The risks to the TATB supply chain, if not addressed, have the potential to delay Life Extension Program and modernization schedules, according to both DOD and NNSA representatives we interviewed.

Based on our review of NNSA documentation and interviews with NNSA officials, there are three key risks facing the insensitive high explosives supply chain: (1) the sole-source supplier of a material used in the formulation of insensitive high explosives is discontinuing production; (2) testing challenges with material specifications; and (3) manufacturing challenges at Holston.

· Sole-source supplier discontinuing production for needed material. In 2022, NNSA was informed that the vendor that supplies a material used in insensitive high explosives production will be ceasing operations. NNSA and site representatives stated that this supply chain challenge surprised them and there was no established risk plan to address the issue. The vendor’s cessation of operations has resulted in delivery delays, NNSA contractor representatives said. Moreover, according to an NNSA risk document, if NNSA is unable to identify material to extend its current inventory or an alternative source of the material is not identified and qualified prior to fiscal year 2026, three weapons programs will have to implement other mitigation strategies or risk not having the material necessary to meet their respective war reserve production requirements.

· Testing challenges with material specifications. Final components containing newly produced insensitive high explosives do not yet consistently meet performance and mechanical specifications, according to NNSA documentation. For example, Holston produces TATB and TATB-based formulations to current NNSA specifications, but the material may not perform correctly after it leaves Holston, according to Holston and NNSA representatives. Specifically, NNSA’s current specification may not be precise enough to consistently produce parts with the required material properties after pressing.

· Manufacturing challenges at Holston. Holston produces explosives for NNSA, and the site faces several manufacturing challenges that may affect its ability to provide insensitive high explosives on time. For example, DOD demand for high explosives used in conventional munitions has the potential to compete with NNSA’s needs. Additionally, Holston is constrained in its ability to meet both DOD and NNSA material delivery schedules because of its current emissions systems and toluene emissions limit. Specifically, using its current technologies, the plant could reach its toluene emissions limit before producing needed amounts of explosives, which can result in production delays.[28]

NNSA has adopted several mitigation strategies to address risks to the insensitive high explosives supply chain and ensure sufficient supply to support stockpile modernization programs. These steps include: (1) conserving, recycling, and exploring alternatives to the material for which the vendor has ceased production; (2) re-examining and defining the TATB requirements; and (3) paying for some equipment and facility upgrades at Holston, developing a new TATB synthesis and formulation capability at another DOD site, and pursuing construction of HESFP at Pantex.

· Conserving, recycling, and exploring alternative materials. NNSA leadership worked closely with the company that discontinued production of the required material, and officials told us that they obtained a commitment from the company to produce enough material to meet current program needs.[29] Prior to attaining this commitment, the Office of Stockpile Modernization chartered an Insensitive High Explosives Issues Resolution Group that identified three mitigation strategies for the key material, and these mitigation strategies are still being pursued regardless of the company’s commitment to produce additional material, according to NNSA officials. These mitigation strategies are reuse, recycle, and reclaim.[30] However, according to NNSA officials, the recycle and reclaim mitigations have been deemphasized due to environmental concerns with previously used material. In addition, multiple NNSA sites are working to find and test potential new material suppliers and to develop novel alternative materials.

· Re-examining and defining TATB specifications. The final specification for TATB is continually assessed as material properties are refined. Currently, LANL and LLNL are proposing changes to the TATB specification to refine the explosive’s properties to address testing challenges with material specifications, according to NNSA officials and documentation.

· Facility upgrades at Holston, new capability at another DOD site, and planning HESFP. According to NNSA documentation, the agency’s main strategy to mitigate risks facing insensitive high explosives production and supply is the three-pronged effort of DOD’s modernization efforts at Holston, establishing TATB production at another DOD site, and eventually constructing the HESFP at Pantex. For example, Holston is planning several modernization projects to address risks facing insensitive high explosives production. Specifically, Holston is planning to modernize its emissions systems, capturing more toluene and allowing higher rates of TATB production under its current toluene emissions limit.

While explosives risks such as material supply and manufacturing challenges have not yet impacted the schedules for any weapons systems, some modernization programs in the pipeline will be affected by current risks if those risks are not sufficiently mitigated, according to NNSA documentation and DOD officials. High explosives are under increasing demand because they are required for every weapon in the nation’s stockpile, which exacerbates high explosives supply chain constraints and forces DOD and NNSA to make difficult decisions regarding program priorities. According to NNSA documentation, if Holston has to further reduce or halt operations, production of insensitive high explosives will be negatively impacted and affect weapons modernization schedules. NNSA’s reliance on a single supplier for the nuclear security enterprise’s explosives needs constitutes a programmatic risk for the entire enterprise, touches almost every aspect of production modernization, and poses a global security risk for the nation, according to NNSA site representatives we interviewed.

Overall, the current industrial base for explosives manufacturing is insufficient to meet the demand for the nuclear security enterprise, according to NNSA documentation. Similarly, the U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) commander identified high explosives as an area of concern in his annual assessment of the stockpile.[31] According to NNSA documentation, unless the nuclear security enterprise successfully implements its risk mitigation plans, NNSA will fall short on insensitive explosives for main charges.

NNSA Is Taking Steps to Mitigate its Explosives Infrastructure Risks, but Some Efforts Are Paused Due to Competing Priorities

NNSA’s existing infrastructure faces risks from aging and deteriorating conditions, a changing regulatory environment, and budgetary constraints. To address these risks, NNSA is in the process of updating or replacing several of its facilities and undertaking other infrastructure efforts. However, NNSA has paused some of these efforts due to competing priorities. We discuss additional infrastructure risks facing DOD sites involved in producing explosives for NNSA in a controlled unclassified information annex to this report.[32]

NNSA’s Existing Infrastructure Faces Three Risks

According to NNSA officials, data, and documentation, NNSA’s nearly $4 billion in existing explosives infrastructure faces risks. These risks include (1) aging and deteriorating conditions that increase maintenance costs and pose safety concerns; (2) a changing regulatory environment; and (3) budgetary constraints.

· Aging and deteriorating conditions. According to NNSA documentation, the average age of explosives infrastructure assets across the nuclear security enterprise is about 50 years. Of the roughly 450 assets related to the explosives program, NNSA rated about 60 percent as insufficient (either poor or very poor) in its 2023 Master Asset Plan.[33] According to NNSA documentation, the explosives program had about $225 million in deferred maintenance for its assets in 2022.[34] For example, an explosives pressing and machining facility at LANL dates to the 1950s, and LANL needs to constantly repair utilities and equipment in this aging facility, according to LANL representatives. Additionally, at Pantex, existing facilities are capable of synthesizing and formulating small batches but have degraded to the point that they pose operational and safety risks, according to NNSA documentation.

· Changing regulatory environment. According to NNSA officials, a changing regulatory environment also presents a risk to NNSA’s explosives infrastructure. NNSA site representatives and DOD officials mentioned a new environmental regulation that could affect their explosives infrastructure. Specifically, a proposed Environmental Protection Agency rule revising the standards for open burning/open detonation of waste explosives could limit explosives facilities’ production capacity if their waste disposal options are limited.[35] For example, LANL, LLNL, and Sandia all conduct open burning of waste explosives, and these operations could be limited with the new Environmental Protection Agency rule and eventually result in a waste backlog. At Sandia, open burn/open detonation is the only feasible disposal method at one high explosives facility, according to NNSA officials. Holston representatives also expressed concern about the rule impacting their operations.

· Budgetary constraints. According to agency officials we interviewed, NNSA’s existing and planned explosives infrastructure is often subject to annual budgetary constraints that can make starting new projects or programs difficult. For example, NNSA’s HESFP project was paused in fiscal year 2023 and part of fiscal year 2024 due to budgetary constraints across the enterprise. While NNSA resumed HESFP project activities in August 2024, agency officials expressed concern that they might not be able to restart work on other paused line-item construction projects when ready if DOE is under a continuing resolution. Continuing resolutions have frequently been enacted to provide temporary funding across the government until action is completed on regular appropriations acts.[36] As we have previously reported, continuing resolutions can create uncertainty about which projects or programs will be funded and at what level.[37] In particular, amounts appropriated under a continuing resolution are not available to initiate or resume projects or activities for which appropriations, funds, or authority were not available during the prior fiscal year.

NNSA Is Pursuing Infrastructure Improvements but Paused Some Efforts Due to Competing Agency Priorities

To mitigate the risks posed by aging and deteriorating explosives infrastructure, NNSA is in the process of updating or replacing several explosives facilities built in the 1940s and 1950s through (1) major, line-item construction projects, (2) minor construction projects, and (3) other recapitalization efforts. However, NNSA has paused some of these efforts due to competing priorities.

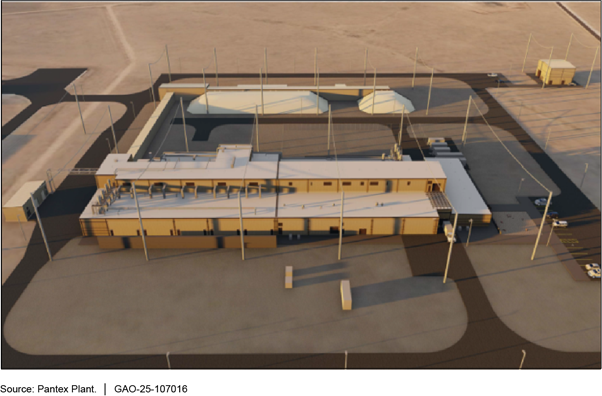

· Major, line-item construction projects. NNSA’s plans include four major, line-item explosives construction projects that could cost between $1 billion to $2 billion over the next decade (see table 3).[38] For example, NNSA is diversifying the nuclear security enterprise’s TATB production source by building the HESFP facility at Pantex, establishing an internal capability that creates an additional TATB production stream. However, in fiscal year 2023, NNSA had placed three of its four planned explosives major construction projects on pause, including HESFP, primarily due to competing priorities across the enterprise.[39] Representatives at several NNSA sites said that pausing HESFP, in particular, would prolong NNSA’s dependence on DOD for main charge explosives. As of August 2024, NNSA officially restarted the HESFP project, according to NNSA officials. See figure 9 for a rendering of HESFP.

Table 3: NNSA’s Explosives Program’s Planned and Ongoing Line-Item Construction Projects, Fiscal Year 2024

Dollars in millions

|

Project name |

Site |

Status |

Estimated cost (low range) |

Estimated cost (high range) |

Planned completiona |

|

High Explosives Science & Engineering |

Pantex Plant |

Under construction |

$300 |

$300 |

November 2028 |

|

High Explosives Synthesis, Formulation, and Production |

Pantex Plant |

Final design approved/pause lifted |

$523 |

$721 |

2034 |

|

Energetic Materials Characterization |

Los Alamos National Laboratory |

Mission need approved/paused |

$284 |

$396 |

2030s |

|

Radiography Assembly/Disassembly Complex Replacement |

Los Alamos National Laboratory |

Mission need approved/paused |

$458 |

$574 |

2030s |

|

Total |

|

|

$1,565 |

$1,991 |

|

Source: GAO analysis of National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) documentation. │ GAO‑25‑107016

aThe planned completion dates listed in the table above are reported based on each project’s most recent schedule estimate as of January 2025.

Figure 9: Major Construction Project Rendering for High Explosives Synthesis, Formulation, and Production Facility, Pantex Plant

· Minor construction projects. In fiscal year 2024, NNSA had five active minor construction projects supporting the explosives capability, totaling around $100 million, with most of these on track for completion in fiscal year 2024 or 2025. For example, the Light Initiated High Explosives Test Facility Upgrades project at Sandia was on track for completion by the first quarter of fiscal year 2025 for a total project cost of $23.4 million, according to Sandia representatives. These officials said the original Light Initiated High Explosives building was small, cramped, and crowded, and the new building is an annex attached to the old building that expands both the office space and the testing capability. NNSA officials said an additional 10 minor construction projects supporting the high explosives capability are in various stages of planning and readiness to execute. The estimated costs for these project proposals, according to NNSA officials, total about $137 million, to be incurred between fiscal years 2025 and 2028, subject to any future changes in requirements, priorities, or appropriations.

· Other recapitalization efforts. NNSA has also supported all five explosives sites’ infrastructure recapitalization efforts.[40] Officials with the Office of Infrastructure estimated having spent about $15 million on these efforts over the last 5 fiscal years. For example, at NNSS, the Office of Infrastructure allocated $2.3 million in recent years to purchase equipment to help modernize the site’s testing facilities. NNSA officials said they have plans for an additional eight recapitalization projects totaling about $56 million over the course of fiscal years 2025–2028.

In recent years, NNSA has also used other methods to mitigate risks to explosives infrastructure, including (1) alternative acquisition methods, (2) alternative construction methods, and (3) rescoping projects.

· Alternative acquisition methods. NNSA entered into an interagency agreement with DOD to stand up a new TATB synthesis and formulation capability to mitigate several infrastructure risks. NNSA believes this capability can be brought online to mitigate risks posed by budgetary constraints for major construction projects as well as risks posed by existing aging infrastructure. Specifically, DOD is using its Other Transaction Authority (OTA) to establish the TATB facility at another DOD site as a prototype project.[41] However, this means it is DOD’s responsibility to manage the contract for building the new TATB synthesis capability, including managing cost and schedule. This also means that NNSA will have less control over and insight into any cost or schedule issues with the facility. We and others have previously reported that the use of OTAs carries the risk of reduced accountability and transparency.[42]

· Alternative construction methods. To mitigate the risks posed by budget uncertainty and a changing regulatory environment, NNSA has employed alternative construction methods in recent years. Specifically, NNSA initiated a minor construction project to construct a “building within a building” in what used to be an open, outdoor atrium at one of LLNL’s research and testing buildings (see fig. 10). According to LLNL representatives, because this addition was an independent building, the site was not required to perform a seismic evaluation of the existing building. Had the buildings been connected, LLNL would have had to perform a seismic evaluation on the combined buildings and resolve any deficiencies, which would have likely cost more and taken more time, LLNL representatives said.

Figure 10: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Built a New Laboratory Building in an Existing Atrium

· Rescoping projects. Responding to budgetary uncertainties or risks, NNSA has used certain project planning techniques to make obtaining funding for infrastructure modernization easier. Specifically, NNSA has asked sites to consider the smallest project needed to achieve their mission instead of major line-item construction projects. For example, the Energetic Materials Characterization and Radiography Assembly/Disassembly Complex Replacement projects at LANL have been paused due to funding prioritization decisions. As a result, LANL representatives said they are breaking off some aspects of these projects’ scopes into what are known as general plant projects to try to build small project elements faster, without the pressures of seeking line-item funding.

LANL representatives said they believe this approach will lead to a smaller total project cost, as they will not have to follow DOE’s rigorous project management criteria for capital asset acquisitions if the individual general plant projects remain below certain thresholds.[43] However, LANL representatives also noted that general plant projects still generally need to compete for funding internally within site budgets.

NNSA Has Taken Some Steps to Improve Explosives Risk Management to Enhance Supply Chain Resiliency

NNSA’s management of its High Explosives and Energetics Program fully or substantially followed five of the eight leading practices we identified for managing supply chain risks, based on our analysis of NNSA documents and information provided during interviews with agency officials (see table 4). NNSA partially followed the other three of the eight leading practices. Further action consistent with the three leading practices that were not fully or substantially met could improve future supply chain resiliency, consistent with the policy established by the 2021 Executive Order on America’s Supply Chains.[44] The order defines resilient supply chains as secure and diverse—facilitating greater domestic production, a range of supply, built-in redundancies, adequate stockpiles, and safe and secure digital networks, among other things.[45]

Table 4: Extent to Which National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA) Management of its High Explosives and Energetics Program Followed Leading Practices for Supply Chain Risk Management

|

Leading practice |

Extent followed |

|

Establish executive oversight of supply chain risk management activities |

● |

|

Develop an agencywide supply chain risk management strategy |

● |

|

Establish a process to identify and document agency supply chains |

● |

|

Establish a process to conduct agencywide assessments of supply chain risks |

● |

|

Establish a process to conduct risk reviews and develop requirements of suppliers |

◒ |

|

Develop a resiliency strategy to ensure future supply |

◒ |

|

Develop a skilled workforce to manage supply chain risks |

◒ |

|

Establish interagency coordination and collaboration on strategic supply chain risks. |

● |

Legend:

● Fully or substantially followed—NNSA took actions that addressed most or all aspects of the key questions GAO examined for the practice.

◒ Partially followed—NNSA took actions that addressed some, but not most, aspects of the key questions GAO examined for the practice.

○ Not followed—NNSA took no actions that addressed the aspects of the key questions GAO examined for the practice.

Source: GAO analysis of National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) documents and interviews with NNSA officials. | GAO‑25‑107016

· Establish executive oversight of supply chain risk management activities. We found that NNSA fully or substantially followed the best practice of establishing executive oversight of supply chain risk management activities. Both NNSA’s December 2022 High Explosives and Energetics Risk Management Plan and its September 2021 High Explosives and Energetics Mission Strategy identify NNSA’s Office of High Explosives and Energetics Director as responsible for leading the explosives risk management process.[46] These documents also outline the roles and responsibilities of senior leadership for risk management activities. During our review, though, leadership of the program was unstable, as both the director and deputy director left their positions, and leadership was provided by acting personnel. However, continuity in responsibility for the program was provided by contractor support and agency-level leadership. In addition, NNSA officials said they hired a new director in June 2024 and a new deputy director in December 2024.

We have previously reported on the importance of continuity in leadership in federal agencies facing complex, long-term management challenges.[47] Frequent turnover in top leadership positions can result in difficulty building relationships with external stakeholders, inconsistent and incomplete initiatives, and a focus on short-term actions over long-term priorities.

· Develop an agencywide supply chain risk management strategy. We found that NNSA fully or substantially followed this leading practice by developing the explosives program’s Risk Management Plan that outlines its risk management strategy. The Risk Management Plan explains how the program will identify, assess, and respond to explosives modernization and supply chain-related risks. Explosives program officials coordinate with other program offices and site contractors to develop supply chain risk management plans for 11 key explosives, including annually updated supply chain maps and associated risk registers, according to NNSA officials. NNSA also has a Supply Chain Risk Management Team Charter looking at the entire industrial base. This charter lays out three phases for the development of supply chain best practices and supply chain risk evaluation requirements to continue assisting programs and site contractors with supply chain risk management across the enterprise.

· Establish a process to identify and document agency supply chains. We found that NNSA fully or substantially followed this leading practice by engaging with labs and production facilities to create supply chain maps that identify and document 11 key explosives supply chains. According to NNSA officials, PNNL supports the high explosives program enterprise-wide for NNSA by coordinating updates of the maps and associated risks at least annually and providing a quarterly report to the explosives program on a subset of supply chain risks that require more frequent review. Additionally, the Risk Management Plan provides guidance on how site contractors can identify and document supply chain risks. According to the plan, site contractors are to identify and elevate to NNSA’s central Office of High Explosives and Energetics those risks that are not within their power to effectively manage. For example, Pantex representatives said they elevate risks identified at the site level to NNSA headquarters, when appropriate, so NNSA can help manage the risks enterprise-wide.

· Establish a process to conduct agencywide assessments of supply chain risks. We found that NNSA fully or substantially followed this leading practice because the current agencywide risk assessment process identifies and tracks risks through annual risk registers and supply chain maps. According to the Risk Management Plan, the supply chain risk assessment process involves analyzing issues, threats, and opportunities to rank or prioritize risks. The plan describes two assessment phases: an initial assessment that does not consider mitigation responses, or a handling strategy; and a second assessment that does account for a handling strategy, actions, or responses. This agencywide assessment process results in the annual supply chain maps and risk registers. In addition, NNSA officials said they used Failures Modes Effects Analysis, which evaluates possible supply chain failure modes and identifies redundant modes, to aid in their supply chain map creation.

· Establish a process to conduct risk reviews of and develop requirements for suppliers. We found that NNSA has partially followed this leading practice because its official policy document setting forth the factors to be used for assessing suppliers and establishing a process for supplier risk assessments is still in draft. Best practices suggest establishing an organizational process for conducting a supply chain risk management review of a potential supplier prior to entering into a contract with a supplier as well as developing tailored supply chain risk management requirements for inclusion in contracts. The agency has drafted a policy document with eight factors to consider before contracting with a supplier, but the policy is not yet finalized, according to NNSA officials. As we reported above, NNSA officials have identified foreign, sole-source, and single suppliers as key risks. If NNSA finalizes its policy documenting its process for assessing suppliers, the explosives program should be better positioned to identify risks early on and to accurately prioritize the risks posed by different suppliers.

· Develop resiliency strategy to ensure a future supply. We found that NNSA partially followed this leading practice because the agency has a resiliency strategy focused on ensuring a future supply, but the strategy does not address all known explosives supply chain risks.[48] Our prior work on semiconductor supply chains found that policy options to support supply chain resiliency would include strategic action to build resiliency in addressing risks, including larger geopolitical risks.[49] We earlier identified the 10 main types of risks faced by NNSA’s explosives supply chains across 64 threats and two issues, but NNSA’s primary resiliency plan addresses only sole-source supplier and infrastructure risks.

Specifically, NNSA’s January 2023 plan, Building a Resilient Multi-Source Supply Chain for Insensitive High Explosives, identifies the agency’s current infrastructure efforts, such as modernizing Holston, establishing the new DOD capability, and planning for HESFP as its resiliency plan. This resiliency plan aims to ensure adequate production capacity. If successful, this plan to have multiple suppliers could also address certain infrastructure (facility and equipment) challenges, as well as operational delays the explosives program currently faces. Yet, the plan does not include strategies to develop more resiliency in the other risk categories, such as testing challenges, or legacy materials and processes that may be difficult to reproduce. A comprehensive resiliency strategy that addresses all 10 risk categories could help ensure that the explosives supply chain is adaptable and flexible enough to respond to risks by minimizing potential disruptions to the supply chain.

· Develop a skilled workforce to manage supply chain risks. We found that NNSA partially followed this leading practice because agency officials said they encourage individual sites to share best practices. However, it has not established expectations for site contractors to train their employees on supply chain risk management. The 2021 Executive Order on America’s Supply Chains identifies the need to develop workforce capabilities to ensure a resilient supply chain.[50] NNSA officials told us the agency is developing risk policies and procedures for the enterprise and allows site contractors to develop their workforces based on the skills needed at each site. NNSA officials told us that the sites do not officially train people in supply chain risk management. An agencywide supply chain risk management framework document is currently in draft, and an accompanying contractor requirements document includes a responsibility for contractor supply chain risk management team leads to provide annual supply chain risk management awareness training for contractor employees at its sites. If NNSA finalizes this contractor requirement for providing supply chain awareness training, the explosives program should be better positioned to identify and address supply chain risk management issues.

· Establish interagency coordination and collaboration on strategic supply chain risks. We found that NNSA fully or substantially followed this leading practice because NNSA and DOD are coordinating and collaborating on enterprise-wide supply chain risks through working groups, communication efforts, and infrastructure projects. NNSA and DOD have established a long-standing interagency effort to modernize the nuclear deterrent. DOD and NNSA’s partnership aims to increase responsiveness to meet stockpile needs with a defined set of capabilities and capacities. For example, according to NNSA officials, NNSA’s explosives program is an active member of the Critical Energetic Materials Working Group with DOD that meets monthly to discuss supply chain issues.

The explosives program also collaborates with DOD’s Joint Services, Industrial Base Policy, and STRATCOM to liaise on supply chain issues affecting the stockpile. Additionally, STRATCOM’s commander highlighted high explosives as an issue of concern in his annual stockpile memo to Congress, according to a STRATCOM official. The official said that while high explosives risks and limitations have not yet impacted weapons systems production, they pose a future threat if not resolved. DOD does not interfere with or advise NNSA on how to determine requirements for securing high explosives or re-establish a reliable supply of insensitive high explosives, according to the STRATCOM official. According to DOD and NNSA representatives we interviewed, it is NNSA’s responsibility to engage with DOD to ensure risks are communicated and develop solutions to address concerns.

Conclusions

NNSA is undertaking a multi-billion-dollar effort to sustain and modernize U.S. nuclear weapons over the next several decades. Explosives are essential to the operation of these weapons. However, NNSA’s explosives supply chain is facing risks. These include material supply, manufacturing, and infrastructure risks that collectively could impact the success of its weapons modernization programs.

NNSA is taking steps to mitigate risks to its supply chain by engaging in efforts that fully or substantially followed five of the eight leading practices we identified for managing supply chain risks. However, NNSA only partially followed three others. Further action, consistent with leading practices that are not yet fully or substantially met, would better enhance supply chain resiliency into the future.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to NNSA:

The NNSA Administrator should finalize the policy that includes a process to conduct supplier risk reviews and risk-informed requirements for qualifying suppliers to safeguard the explosives program from supplier-based risks. (Recommendation 1)

The NNSA Administrator should ensure that its strategy for supply chain resiliency within the explosives enterprise is comprehensive and addresses all identified risks. (Recommendation 2)

The NNSA Administrator should finalize plans to require supply chain risk management training for contractor staff responsible for explosives supply chain risk management. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to NNSA and DOD for comment. In NNSA’s comments, reproduced in appendix II, NNSA agreed with our recommendations and described plans to address them. NNSA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. NNSA indicated in its technical comments to our draft report that high explosives infrastructure data had been updated since the time of our review. Although the site-specific numbers of assets may have fluctuated slightly since our review, the general context the data provides did not change significantly. As we were unable to verify NNSA’s latest data provided prior to publishing, we determined that our data were complete and accurate as of December 2024. DOD did not provide a formal comment letter or technical comments.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Energy, the NNSA Administrator, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-3841 or bawdena@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Allison Bawden

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger F. Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable John Kennedy

Chair

The Honorable Patty Murray

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Chuck Fleischmann

Chairman

The Honorable Marcy Kaptur

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

This report (1) describes the state of the explosives supply chain; (2) describes the state of the National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA) explosives infrastructure and site projects; and (3) assesses the extent to which NNSA’s explosives program manages risks to ensure supply chain resilience.

To address all three objectives, we conducted site visits to four key NNSA sites involved in explosives research, development, and production—Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), Pantex Plant (Pantex), and Sandia National Laboratories (Sandia)—and two Department of Defense (DOD) sites. We selected these sites because they conduct or are expected to contribute significantly to the nuclear security enterprises’ explosives activities. We interviewed NNSA and DOD officials and contractor representatives on these site visits and in follow-up meetings about current explosives activities and future plans related to the supply chain, infrastructure, interagency coordination, and overall management of NNSA’s explosives activities. On the site visits, we toured both existing and planned (under construction) explosives infrastructure assets to better understand the purpose and condition of such assets.

To describe the state of the explosives supply chain, we reviewed agency documents and interviewed NNSA and contractor representatives to identify risks facing the explosives supply chain. We also reviewed and analyzed NNSA’s supply chain documentation for all of the 11 explosives products for which NNSA has created supply chain maps and risk registers. Specifically, we analyzed the documents to categorize the types of supply chain risks NNSA has identified, as well as the actions NNSA planned to take to respond to those risks.

To describe the state of NNSA’s explosives infrastructure and site projects, we reviewed and analyzed infrastructure data and documents from NNSA and its contractors. Specifically, we analyzed the data to determine the total number of explosives-related infrastructure assets as of fiscal year 2024 and those assets’ total replacement plant value, and to verify trends described by NNSA and contractor representatives during interviews and site visits. We took steps to assure the reliability of these data and found them to be sufficiently reliable to describe the state of the explosives supply chain. Specifically, we assessed the reliability of the contractor infrastructure data by: (1) performing electronic testing; (2) reviewing existing information about the data and the systems that produced them; and (3) interviewing agency officials knowledgeable about the data.

To assess the extent to which NNSA’s explosives program manages risks to ensure supply chain resilience, we first identified eight leading practices for supply chain risk management and resilience based on our prior work.[51] Specifically, we reviewed leading practices from our prior work, the workpapers and literature sources used to develop these practices, and any additional GAO reports. The leading practices, which we have previously relied on to assess supply chain risks for information technology and semiconductors, were derived from National Institute of Standards and Technology guidance applicable to federal agencies, including the Department of Energy, as well as an extensive literature review and interviews with industry executives, government officials, and representatives from academia and nonprofits.[52]