AIR FORCE READINESS

Actions Needed to Improve New Process for Preparing Units to Deploy

Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

November 2024

GAO-25-107017

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107017. For more information, contact Diana Maurer at (202) 512-9627 or maurerd@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107017, a report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

November 2024

Air Force Readiness

Actions Needed to Improve New Process for Preparing Units to Deploy

Why GAO Did This Study

More than 2 decades of conflict have degraded the Air Force’s readiness, with wide-ranging effects on personnel, equipment, and aircraft from near constant deployments. To rebuild readiness and restore predictability, the Air Force has begun implementing a new cyclical process to organize and deploy its forces, known as AFFORGEN.

House Report 118-125, which accompanied a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, includes a provision for GAO to examine the implementation of AFFORGEN. Among other things, this report assesses the extent to which the Air Force has addressed any challenges in implementing AFFORGEN, and the Air Force’s efforts to implement AFFORGEN align with selected leading agency reform practices.

GAO analyzed Air Force documentation; interviewed Department of Defense and Air Force officials; and visited selected major commands and units to identify any challenges in implementing AFFORGEN.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations to the Air Force, including that it completes an assessment of minimum U.S. base staffing needs and issues an implementation plan for AFFORGEN that includes goals, a timeline with key milestones, and performance measures. DOD concurred with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Air Force has taken steps to address some challenges in implementing its new process to organize and deploy its forces—known as Air Force Force Generation (AFFORGEN)—but continues to face a variety of ongoing challenges. The Air Force began implementing AFFORGEN in late 2022 to create forces that train and deploy together. To address lessons from early deployments, the Air Force has revised the composition of these forces and tailored the AFFORGEN process to specific types of units, such as bombers.

However, GAO identified several ongoing implementation challenges. For example, the Air Force has not completed an assessment of minimum U.S. base staffing needs. Under AFFORGEN, the Air Force planned to deploy whole units from U.S. bases. However, it has relied on some of these personnel to operate its bases and perform duties like staffing security gates.

The Air Force’s ongoing efforts to implement AFFORGEN partially align with some selected leading reform practices and do not align with others. For example, while the Air Force has released visionary statements, it has not set goals to track implementation progress.

|

Leading reform practice |

Extent Air Force efforts align |

|

Establishing Goals and Outcomes |

◒ |

|

Involving Employees and Key Stakeholders |

◒ |

|

Using Data and Evidence |

○ |

|

Addressing Longstanding Management Challenges |

◒ |

|

Leadership Attention and Focus |

◒ |

|

Managing and Monitoring |

○ |

|

Employee Engagement |

◒ |

|

Strategic Workforce Planning |

◒ |

◒ Partially aligned with leading reform practice ○ Did not align with leading reform practice

Source: GAO analysis of Air Force information. I GAO-25-107017

Air Force officials said they rapidly implemented AFFORGEN to prepare for potential conflict with near-peer competitors. These officials recognized that an implementation plan with goals, a timeline with key milestones, and performance measures would help ensure unity of effort across the service and a shared understanding of the path forward.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ACC |

Air Combat Command |

|

AEF |

Air Expeditionary Force |

|

AEW |

Air Expeditionary Wing |

|

AFFORGEN |

Air Force Force Generation |

|

AFGSC |

Air Force Global Strike Command |

|

AMC |

Air Mobility Command |

|

ATF |

Air Task Force |

|

COCOM |

Combatant Command |

|

DCW |

Deployable Combat Wing |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

GFM |

Global Force Management |

|

HAF A3 |

Headquarters Air Force Deputy Chief of Staff, Operations |

|

ICW |

In-Place Combat Wing |

|

MAJCOM |

Major Command |

|

ReARMM |

Regionally Aligned Readiness and Modernization Model |

|

STRATCOM |

U.S. Strategic Command |

|

UTC |

Unit Type Code |

|

XAB |

Expeditionary Airbase |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 26, 2024

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

More than 2 decades of conflict have degraded the Air Force’s readiness, with wide-ranging effects on its personnel, equipment, and aircraft from near constant deployments, according to our prior work.[1] While the Air Force has worked to rebuild its readiness levels, it has also sought to modernize its forces to meet the needs of the 2022 National Defense Strategy.[2] This strategy prioritizes sustaining and strengthening deterrence against competitors such as China and Russia, and ensuring DOD’s future military advantage by rebuilding readiness and modernizing its forces.

To rebuild readiness and restore predictability and resilience, the Air Force has begun implementing a new cyclical process to organize and deploy its forces, known as Air Force Force Generation (AFFORGEN). The Air Force’s primary focus of the new process is to standardize deployment schedules and meet demand for its units, while providing enough downtime for rest, training, and the preservation and rebuilding of readiness. According to Air Force officials, select units implementing AFFORGEN—including all fighter squadrons, such as F-22 and F-16 squadrons, to date—reached initial operational capability in October 2023. In addition to the active-duty Air Force, the Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve are also implementing AFFORGEN.

House Report 118-125, which accompanied a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, included a provision for us to examine the implementation of AFFORGEN.[3] This report (1) describes the changes the Air Force has made to its process for deploying forces, (2) assesses the extent to which the Air Force has addressed any challenges in implementing this process, and (3) assesses the extent to which the Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN aligns with selected leading agency reform practices.

To identify the changes that the Air Force has made to its process for deploying forces, we reviewed how it used the prior force generation process known as the Air Expeditionary Force (AEF) model to prepare and deploy forces. We also reviewed documentation about AFFORGEN, including why the Air Force developed it. Further, we interviewed Department of Defense (DOD) and Air Force officials to obtain their views on the differences between AEF and AFFORGEN in how the Air Force organizes and deploys its forces.

To determine the extent that the Air Force has addressed any challenges in implementing AFFORGEN, we reviewed documentation such as relevant Air Force instructions and memoranda, and interviewed DOD and Air Force officials. We conducted site visits to selected major commands (MAJCOMs)—Air Combat Command (ACC), Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC), and Air Mobility Command (AMC)—and their respective units. During these visits, we spoke to Air Force officials to identify any challenges they have faced implementing AFFORGEN, including in the areas of organizing, staffing, equipping, or training units.[4] We compared how the Air Force has sought to address these challenges against Air Force instructions, the 2022 National Defense Strategy, and our prior work on Key Questions to Assess Agency Reform Efforts and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[5] Specifically, we reviewed principles concerning how management should use quality information to make informed decisions and how management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving defined objectives.

To determine the extent to which the Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN aligns with selected leading agency reform practices, we analyzed Air Force documents and interviewed officials. We based our selection of the leading reform practices on whether they applied to the Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN and were most relevant for the Air Force to consider as it continues implementing the cyclical process. We assessed whether the Air Force’s efforts to implement AFFORGEN fully aligned, partially aligned, or did not align with the selected leading agency reform practices based on our interviews with Air Force and DOD officials, published Air Force guidance, and other internal Air Force documentation.[6]

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Air Force Organization and Units

The Air Force is generally organized into headquarters staff and MAJCOMs, which include wings—the basic units for generating and employing Air Force combat capability. Headquarters Air Force (HAF) is composed of two major entities—the Secretariat and the Air Staff (A-staff). The A-staff is headed by the Chief of Staff of the Air Force and is responsible for providing plans, recommendations, and advice on a variety of topics to the Secretary of the Air Force, among other tasks.[7] The nine active MAJCOMs are responsible for specific missions or functions supporting the entire Air Force. For example, AFGSC is responsible for worldwide strategic deterrence, while U.S. Air Forces in Europe – Air Forces Africa projects airpower in Europe and Africa from its headquarters in Germany in the service of U.S. interests.

In descending order of command, elements of MAJCOMs include such units as numbered air forces, wings, groups, and squadrons that include personnel, equipment, and aircraft.[8] These entities support base operations or specialized missions, among other tasks. In overseeing their missions or regions, MAJCOMs are responsible for the administration, training, and readiness of their subordinate forces. For example, ACC ensures fighter units train and deploy to meet their missions.

The Air Force seeks to ensure that operational forces are properly organized, trained, equipped, and ready to respond to and sustain operations. When the Air Force deploys its forces, it creates force packages made up of important capabilities such as personnel, aircraft, and equipment.[9] Air Force Unit Type Codes (UTCs) make up the basic building blocks for these force packages. UTCs represent capabilities—personnel, equipment, or some combination of both—that can be included in a force package, ranging from a capability as small as a military working dog and handler to a larger and broader unit of security forces.[10] Air Force leadership can select UTCs from several different wings and locations to meet a deployment need, according to Air Force officials.

Figure 1 shows the organization of the Air Force and how it deploys personnel in force packages using UTCs.

aAir Force officials used various terms over the course of our review to refer to groups that deploy, including units of action, force packages, and force elements. In this report, we use the term force packages.

Air Force Process for Preparing Units for Deployment

AFFORGEN is the Air Force’s recently developed cyclical process to organize and deploy its forces.[11] Air Force deployments support the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s (Joint Staff) Global Force Management (GFM) process.[12] According to Air Force documentation, the request for forces process in support of GFM begins when a COCOM identifies a needed capability and the specific requirements of that capability, with a request for forces occurring during this time.[13] The military services with the capacity to fulfill this request submit information to the Joint Staff on the force packages that are ready and available. Using this information, the Joint Staff selects a force package to satisfy the COCOM’s request.

After receiving information from the Joint Staff, the Secretary of Defense then considers and eventually decides on a course of action regarding this force package and request. In addition, the Joint Staff hosts periodic GFM Board meetings to assess the operational effects of GFM decisions and provide strategic guidance during this process.[14] At these meetings, HAF officials representing the Deputy Chief of Staff, Operations (A3) provide an assessment of force availability and capacity, and present an overview of the force generation process, among other topics.[15]

Under New Force Generation Process, Units Train and Deploy Together More Frequently

The Air Force began implementing AFFORGEN in late 2022 to overhaul the previous force generation process it used for over 2 decades, known as AEF. Under AEF, the Air Force brought personnel and equipment—in the form of UTCs—together from several wings located at various bases to meet a COCOM’s request for forces; a process Air Force officials referred to as “crowdsourcing.” The Air Force then created force packages from the UTCs it selected and deployed these packages to COCOMs’ areas of responsibility, or regions, according to Air Force documentation and Air Force officials.

|

Air Force Deployments in the Middle East According to HAF officials, the Air Force has deployed forces to bases throughout the Middle East for over 3 decades to support operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and other U.S. Central Command missions. For example, U.S. Central Command officials stated that it has sent personnel to the largest U.S. base in the region, Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar, to fulfill various mission needs. Air Forces Central officials explained that these deployments are mainly supported by the 9th Air Force (Air Forces Central). Under the AEF process, Air Forces Central could specifically define the composition of forces, in terms of UTCs, it needed to support these bases, according to Headquarters 9th Air Force officials. Since bases in the region are well-established with key infrastructure and support personnel in place, Air Forces Central did not need entire wings to deploy, according to the same officials. Source: GAO interviews. | GAO‑25‑107017 |

The Air Force’s use of UTCs for assigning personnel to force packages has played an important role in its deployment efforts. According to HAF and Air Force Personnel Center officials, under AEF the Air Force created UTCs with fewer and fewer personnel over the years and fine-tuned what specialties the UTCs represented. Joint Staff and Air Forces Central officials stated that changes were made to UTCs so the Air Force could provide very specific types of personnel, often in small numbers rather than entire squadrons or wings, to meet requirements for deployment requests. This effort resulted in a growth of UTCs to over 3,000, many of which averaged one-to-three personnel, according to HAF officials.

According to HAF officials, over the years, the Air Force offered the Joint Staff an “à la carte” menu from which to select its forces. While this allowed the Air Force to be flexible and responsive to COCOMs’ needs with tailored force packages made up of personnel representing numerous UTCs, various Air Force officials stated this presented two key challenges:

· HAF officials stated that the Air Force had a difficult time showing the Joint Staff what capabilities were unavailable to meet the COCOMs’ needs and the readiness effects, if any, of deploying additional forces. Rather than deploying large, standard force packages like a wing, the Air Force built custom force packages based on finely tuned categories of UTCs, often drawn from several wings or squadrons, to fill different requirements, according to HAF A3 Training and Air Force Personnel Center officials. They also stated that doing so made it difficult for the Air Force to show when deploying additional forces would adversely affect the current and future readiness of squadrons or wings.

· Combining various individuals from different wings meant that, in many cases, personnel had never met or worked together prior to deploying. HAF officials said that this had negative effects on unit cohesion—and in some cases performance—when deployed.

The AFFORGEN process seeks to change how the Air Force generates and presents forces to better mirror how the other military services generate and present forces to meet COCOM requirements, according to Air Force documentation and Joint Staff officials. For example, the Navy offers carrier strike groups as a standard force package to the COCOMs.[16] The Navy’s 11 carrier strike groups have established force generation schedules. This allows the Navy to clearly show how many carrier strike groups are available for deployment, and when an aircraft carrier and other ships need to undergo extended maintenance and would not be available for a deployment.[17]

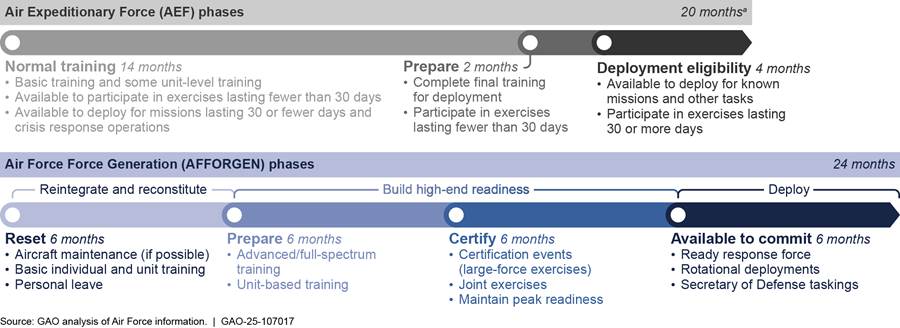

The Air Force expects AFFORGEN to provide greater predictability for its personnel. After being assigned to one of the process’s four, 6-month phases—“Reset,” “Prepare,” “Certify,” and “Available to Commit”—as part of a deployable force package, Air Force personnel should know when they will be available for deployment based on where they are in the cycle. In comparison, while the Air Force designed AEF to have a three-phase, 20-month cycle, in practice these phases could vary in length. Figure 2 shows the differences between the AEF and AFFORGEN processes in terms of notional cycle length and phases.

aThe time frame for AEF phases could vary, according to Air Force documentation.

By implementing AFFORGEN, the Air Force seeks to meet the DOD deployment-to-dwell goal for active-duty units of a ratio of 1:3 or greater, so that forces have adequate time to recover from deployment, train, and rebuild readiness to compete with near-peer competitors.[18]

With greater predictability for future deployments, Air Force officials hope the AFFORGEN process will also help improve personnel morale. For example, Air Force Sustainment Center and 8th Air Force officials explained that if personnel know when and for how long they will deploy, they then could schedule and take leave during the “Reset” phase. Under AEF, many deployments were extended, or individuals were redeployed quickly, according to Air Force officials. Our prior work has found that after years of constant deployments, both Air Force personnel and equipment have not had adequate time to rebuild readiness.[19]

Training has also changed under AFFORGEN as the Air Force has transitioned away from the AEF process. Under AEF, personnel would undergo just-in-time training as individuals prior to deployment, according to Air Force officials. Air Forces Central and HAF A1 officials explained that these individuals would then deploy, often meeting other deploying personnel in their new unit for the first time when they arrived at their deployment site. There was no collective unit training for these airmen prior to deploying, leading to a steep learning curve as they started serving together at the deployment site, according to Air Force officials.

As part of AFFORGEN’s implementation, the Air Force developed four new stages of training divided into 100- to 400- levels that align with the AFFORGEN phases. For example, during the “Reset” phase, personnel begin 100-level training, which focuses on individual skillsets and task-oriented unit training. As personnel follow the AFFORGEN process and move into the “Certify” phase, they will complete 300- and 400-level training for cohesive unit training. These levels include joint training exercises and certification events where selected personnel train together to demonstrate that they are sufficiently prepared to meet the missions for their upcoming deployment. According to Air Force officials, the process of training together as teams prior to deploying will help personnel build trust and can improve unit performance.

Air Force Has Taken Some Steps to Make Implementation Improvements but Faces a Variety of Challenges

The Air Force has taken some steps to address challenges in implementing AFFORGEN, such as allowing MAJCOMs the ability to tailor the AFFORGEN process to specific unit types. However, it faces a variety of other implementation challenges, including ongoing revisions to force packages and uncertainty regarding the number of personnel required to staff U.S. bases when units deploy.

COCOM-Assigned Units Face Mission-Related Challenges as Demand for Forces Exceeds Capacity

The Air Force retains units for its own missions or has units assigned to COCOMs—a dichotomy which has led to challenges in implementing AFFORGEN. Essentially, Air Force units largely fall within two categories. Some, like units within ACC, are Air Force service-retained, meaning that they remain under the service’s direct command. For example, the 1st Fighter Wing, which maintains and operates half the Air Force’s F-22 aircraft, is assigned to ACC.

Other units are part of a second category—COCOM-assigned—and directly support COCOMs’ missions as directed by the Commander of the COCOM. For example, bomber units, such as the 2nd and 5th Bomb Wings, from AFGSC support U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM), among other COCOMs, with strategic nuclear deterrence and bomber missions. Similarly, AMC units such as the 375th Air Mobility Wing support U.S. Transportation Command’s mobility air missions. Finally, Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) units have a comparable relationship with U.S. Special Operations Command, according to AFSOC officials.

Whether they are service-retained or COCOM-assigned, the Air Force initially intended for all MAJCOMs to follow the AFFORGEN process through the four phases over the span of 2 years. Under AFFORGEN, Air Force personnel could be available to deploy for 6 months every 2 years when in the “Available to Commit” phase. However, the demand for some Air Force personnel, units, and aircraft has exceeded the capacity produced in the “Available to Commit” phase, according to Air Force documentation and officials. As a result, the Air Force and COCOMs must use personnel and units that are in other phases of AFFORGEN, such as the “Reset” or “Prepare” phases. For example:

· AMC officials told us that the Air Force uses aircraft such as the C-17 Globemaster III for transporting personnel, completing medical evacuations, providing support for presidential travel, or meeting military airlift needs, among other tasks (see fig. 3). Under AFFORGEN, approximately 16 C-17s are typically in the “Available to Commit” phase at a time, according to AMC officials. However, daily missions—including requirements from U.S. Transportation Command and the Joint Staff—require approximately 40-to-50 C-17s, according to AMC officials. At times real-word events, such as the October 2023 Hamas attack on Israel, lead to greater demand for these aircraft, according to AMC and U.S. Transportation Command officials. As a result, AMC routinely uses personnel, units, and aircraft assigned to AFFORGEN’s “Prepare” and other phases, according to AMC officials.

· Officials from the 2nd Bomb Wing, the largest bomb wing in AFGSC, stated that personnel from that unit cannot fully participate in AFFORGEN’s “Reset” phase because the wing must consistently participate in nuclear deterrence and bomber mission-related tasks from STRATCOM, leading to stress among personnel. In addition, 8th Air Force officials stated that the 6 months allotted to the “Reset” phase do not provide sufficient time to perform some needed aircraft upgrades, given the small size of some bomber maintenance crews and the length of time required for more complicated maintenance or modernization work.

With not enough forces to meet Air Force and COCOM taskings and move through AFFORGEN’s four phases, AMC and AFGSC officials told us that some units face confusion over whether they would participate in AFFORGEN given that they mainly support COCOMs’ missions, not the Air Force’s taskings. Strategic guidance, such as the Unified Command Plan, provides some direction on how the Air Force and COCOMs should use Air Force units.[20] However, under this strategic guidance, some Air Force units may be identified for both COCOM and Air Force taskings, creating confusion in the units as to whether the AFFORGEN process applies to them. While this guidance exists, some units still face confusion over whether they could be eligible for deployments under the AFFORGEN process given that they are part of the Air Force while also assigned to COCOMs, according to Air Force officials. For example, officials from the 2nd Bomb Wing stated that their unit received deployment and other mission requests from both the Air Force and STRATCOM that they are not sure they can meet.

The Air Force acknowledged the limitations associated with the numbers of units available in relevant AFFORGEN phases and has taken steps to address this issue:

· In January 2024, the commander of AFGSC directed that those AFGSC units assigned to STRATCOM would receive the designation of “employed-in-place.”[21] This designation, in turn, would limit the risk of the Air Force including AFGSC units in planning activities, such as Air Force deployments. Because of this, personnel from some units that are part of AFGSC effectively do not follow all phases of AFFORGEN because they likely will not be included in Air Force deployments, according to officials from the 5th Bomb Wing. However, it is unclear if a future commander of AFGSC would adopt a similar position or possibly designate some units as eligible for these deployments.

· In March 2024, the Air Force began a new annual process to designate employed-in-place units that are not eligible for Air Force deployments under AFFORGEN (i.e., “Excepted Forces”).[22] Under this process, MAJCOMs can submit a request to HAF A3 to designate units as “Excepted Forces” to obtain a final decision about these units’ participation in the AFFORGEN process, according to HAF officials. For example, AFGSC officials stated that their command can revise the cyclical process to organize and deploy its forces to account for missions unique to the bomber force and associated support to STRATCOM’s needs. This request process provides MAJCOMs with the ability to tailor the AFFORGEN process to specific unit types, according to the HAF officials.

Air Force Is Revising Its Force Packages to Address Initial Challenges, but Further Work Remains

The Air Force continues to revise its development of integrated units of personnel that train and deploy together, also known as force packages, that will move through the four phases of the AFFORGEN process together. However, further work remains to consolidate its inventory of UTCs to align with these new force packages.

As the implementation of AFFORGEN continues to evolve, the Air Force has created or plans to create several iterations of force packages. Air Force officials stated that the service designed the first two force packages—referred to as Expeditionary Airbases (XABs) and Air Task Forces (ATFs)—to move away from how they used to deploy under AEF. According to Air Force officials, these two new force packages are steps to its overall plan to move towards deploying personnel and equipment largely from one wing using force packages called Deployable Combat Wings (DCWs) and In-Place Combat Wings (ICWs). Figure 4 shows a depiction of the force package transition from AEF to AFFORGEN and how UTCs have been, or are planned to be, selected for each package. Since UTCs are the building blocks for force packages, the Air Force plans to consolidate and decrease its inventory of over 3,000 UTCs available for each force package iteration, according to Air Force officials. They further stated that the Air Force intends to create UTCs that encompass larger groups of personnel and capabilities.[23]

aThe size of each AEW was location-dependent, according to Air Force officials.

bThe information depicted for DCWs and ICWs is subject to change as the Air Force continues to determine which bases will participate in these force packages and the required personnel needed to implement them, according to Air Force officials.

Expeditionary Airbase (XAB). The Air Force’s first iteration of a new force package under AFFORGEN is known as the XAB. According to an Air Force tasking order, the service designed XABs to be the default force packages it offered to the Joint Staff to generate airpower for missions.[24] In early 2023, the Air Force originally planned to select personnel from about three-to-four wings to deploy as an XAB on October 1, 2023, according to Headquarters Air Force officials.

However, the Air Force faced challenges implementing XABs as planned. First, leading up to the initial deployment of XABs in October 2023, the Air Force did not attempt to consolidate its inventory of over 3,000 UTCs, according to Air Force officials. They added that the Air Force did not build in enough time or resources in its planning of XABs to complete the consolidation of UTCs prior to XABs deploying. Due to this insufficient time, the Air Force reverted to its pre-existing method of selecting individual UTCs from many wings, as it did under AEF, to meet the deployment date for the first XABs, according to Air Force officials. Overall, HAF and MAJCOM officials noted that the first XABs deployed on-time, but these XABs were similar in composition to force packages that the Air Force used under AEF. Unable to meet its selection target, the Air Force selected UTCs containing personnel from about 60 wings to form the first iteration of XABs in 2023.

The initial XABs also faced a range of other challenges, from late notifications of deployments to inadequate training, according to officials from Air Force units we interviewed and Air Force documentation.

Air Task Force (ATF). Recognizing the challenges with XABs, the Air Force is transitioning to a second iteration of force packages under AFFORGEN, known as the ATF. This force package is like the XAB in that the Air Force designed it to be a cohesive force composed of personnel who will train and deploy together. In addition, Air Force officials stated that ATFs will be smaller than XABs, as an ATF will be composed of personnel selected from about four wings.

Headquarters Air Force Checkmate Directorate (HAF A3K) has led ATF development by holding operational planning team meetings and biweekly steering groups to incorporate feedback from MAJCOMs to aide in the implementation of ATFs, according to officials from that directorate. In addition, they explained that much of the feedback received in these forums is based on the MAJCOMs’ experiences and lessons learned from the planning and execution of XAB deployments. HAF A3K officials stated they have shared this feedback with senior Air Force leadership to inform key decisions about AFFORGEN.

In May 2024, the Secretary of the Air Force identified six locations to host pilot ATFs. According to HAF A3 officials, the ATFs’ command structures became operational in July 2024, and these force packages will begin training under the AFFORGEN process in fiscal year 2025. In addition, they stated that the ATFs will train to deploy to anywhere they are needed, with four assigned to U.S. Central Command and two assigned to U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. The ATFs will progress through AFFORGEN’s four phases together.

In planning the pilot ATFs, HAF A3 has taken steps to proactively address challenges that occurred during its implementation of XABs. For example, according to HAF A3 officials, their office has recently begun its consolidation of UTCs while planning for ATFs. According to 628th Air Base Wing and Air Force Materiel Command officials, HAF A3’s approach to implementing ATFs is an improvement compared to the rollout of XABs, as it has sought ongoing coordination with MAJCOMs during this process.

Deployable Combat Wings (DCWs) and In-Place Combat Wings (ICWs). While the Air Force hopes ATFs will improve its ability to select personnel from fewer wings, it seeks to eventually select an entire wing—including combat and mission support units—for deployment from a single base. In February 2024, Air Force officials announced their plan to accomplish this with a new iteration of force packages known as DCWs and ICWs. According to Air Force documentation and HAF A3K officials, DCWs will be composed of deployable units from a single wing that have their own command-and-control, mission, and support elements. Separate wings, known as ICWs, will perform combat missions from the bases, according to Air Force officials. In addition, supplemental wings, known as Combat Generation Wings, will provide specialized support, such as additional fighter or combat support, to DCWs as needed.[25]

HAF A3 officials stated they recognize it will need to further consolidate UTCs for DCWs, but it has not officially started these additional consolidation efforts as of August 2024. HAF A3 and Air Force Material Command officials noted that the consolidation will take time due in part to technical limitations in the online inventory of UTCs.[26] However, the Air Force has not created a plan that establishes timeframes for the UTC consolidation effort that would ensure completion before the first DCWs deploy.

According to Air Force guidance, one- or two person-UTCs should be avoided unless the UTC represents a highly specialized capability, such as a historian or comptroller.[27] Further, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should use quality information to make informed decisions and evaluate the entity’s performance in achieving key objectives, such as better articulating current and future readiness.[28]

Creating a plan that establishes timeframes for the UTC consolidation effort would help ensure that the Air Force’s refinement of force packages under AFFORGEN align with its UTC inventory before DCWs deploy. With the current version of the UTC inventory numbering over 3,000 UTCs—many of which represent just one to three personnel—the Air Force cannot easily show when deploying additional forces would adversely affect the current and future readiness of squadrons or wings.

Air Force Is Unsure of Number of Personnel Needed to Staff Bases

The Air Force does not know the number of personnel needed to continue operating its U.S. bases when units deploy. It has relied on its uniformed personnel, in addition to DOD civilians and contractor personnel, to run its bases in the United States, according to Air Force officials. These personnel can staff entrances, provide security measures for a base’s perimeter, or support the nuclear mission, among other functions (see fig. 5).

Under AEF, the Air Force selected personnel from multiple bases for deployment, so there were minimal effects to U.S. base operations, according to Air Force officials. However, while developing AFFORGEN, the Air Force planned to include some base operations support personnel in the XABs preparing for deployments, according to HAF and base unit officials. Specifically, they planned for these support personnel to deploy and perform similar functions at overseas bases. For example, the Air Force tasked 169th Air National Guard Fighter Wing personnel to operate from Prince Sultan Air Base, Saudi Arabia during their deployment to that location, according to officials from that unit.

We found there could be risks involved in providing some categories of Air Force personnel—including active-duty and National Guard—to deploying force packages. Specifically, Air Force officials told us there were insufficient numbers of personnel to fill some of these roles (e.g., security, communications) simultaneously at U.S. and overseas bases. For example:

· Officials from the Air Force Personnel Center and Air Force Central told us that they did not have enough personnel to fill positions such as sexual assault response coordinators, civil engineers, and other specialty roles (e.g., supply support) at their U.S. bases if they need to send these personnel on deployments as part of XABs or ATFs. This made it difficult for units to provide personnel in these roles for deployments as part of the Air Force’s force packages like XABs and ATFs.

· Officials from the 1st Fighter Wing at Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Virginia stated that Air Force units must support in-garrison missions at U.S. bases while also providing personnel, assets, and equipment to an XAB scheduled to deploy. This was difficult for the 1st Fighter Wing to do because the unit needs specialized personnel like medical staff and air traffic controllers to perform home base duties in the United States, including operating F-22 aircraft. Deployed forces also need these types of personnel, according to the same officials.

· Officials from the 628th Air Base Wing at Joint Base Charleston, South Carolina described a situation in which the Air Force requested more personnel than they could provide. They stated that the Air Force initially requested personnel from their unit and the 437th Airlift Wing (also located at the base) to be part of one of the first XABs scheduled to deploy in October 2023. However, they stated that providing these personnel would have led to the closure of three out of seven gates at the base due to insufficient numbers of remaining personnel to staff them. These officials explained that the Air Force later reduced its request for personnel. After this change occurred, the 628th Air Base Wing staffed all gates at the base with its reduced numbers by implementing a two 12-hour shift schedule for security personnel and cutting the number of staffed lines at the base’s dining facility, according to the same officials.

· Officials from the 5th Bomb Wing expressed concerns that the AFFORGEN process requires the use of whole units for deployments, which could degrade the wing’s ability to support its home base. For example, the unit needs personnel certified to handle nuclear weapons—a difficult certification to obtain—at Minot Air Force Base, North Dakota. Potentially sending some personnel on Air Force deployments as part of XABs could pose a risk due to personnel shortages, according to the same officials.

When planning for deployments, HAF assumed that some bases had more Air Force personnel to provide for XABs and ATFs than was the case. Rather than be available for XABs and ATFs, COCOM officials stated that some of these Air Force personnel needed to remain at their home bases to support COCOMs’ missions (i.e., COCOM-assigned forces like those assigned to STRATCOM or U.S. Indo-Pacific Command). The presence of these personnel allowed the bases to function and the missions to continue with fewer interruptions, according to Air Force officials.

Some units on U.S. Air Force bases have recognized these challenges and have worked to identify and assess some in-garrison staffing needs. For example, 633d Air Base Wing officials at Joint Base Langley-Eustis stated that one of the biggest AFFORGEN-related challenges they faced was a lack of clarity concerning the roles for personnel who have in-garrison missions to fulfill, while also having responsibilities to deploy. To address this issue, the unit studied plans and agreements at Joint Base Langley-Eustis to quantify and understand roles and responsibilities for its personnel, according to the same officials. In addition, 628th Air Base Wing officials stated that they also created a readiness brief to provide commanders about the installation’s capabilities during each phase of the AFFORGEN process; the brief included information about which personnel would need to remain at the base to support critical tasks.

While individual units have begun to assess their in-garrison needs at a local level, the Air Force has neither completed a service-wide assessment of U.S. base minimum staffing needs nor assessed the risks associated with reduced in-garrison support for various base-related missions. A 2023 Air Force “lessons learned” report on the first XAB deployments highlighted these issues.[29] It noted that there appears to be no enterprise-wide understanding of the number of personnel performing in-garrison missions and the mission support resources that U.S. bases require. The report also found that base personnel provide significant daily support at U.S. home bases that the Air Force did not consider while planning for its first XAB deployments. The absence of these personnel therefore created risk at Air Force bases for a wide range of mission-related tasks, such as defensive cyber operations, according to the same report.

The 2022 National Defense Strategy states that DOD will ensure that day-to-day requirements to deploy and operate forces do not erode readiness for future missions.[30] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving defined objectives.[31]

The Air Force is aware of these challenges. In February 2024, the HAF Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations discussed plans to create in-garrison wings in the future, but those plans have not been finalized, according to HAF A3 officials.[32] They added that HAF has completed initial site surveys at some Air Force bases to determine how to support home bases when personnel from those bases deploy as part of ATFs. However, Air Force officials noted that bases are completing analyses for personnel needs as part of individual base initiatives, not as part of a larger Air Force-wide effort to analyze U.S. base needs. Further, although HAF and base officials are aware of personnel gaps, the Air Force has yet to assess the risk of not supporting or reducing support for specific missions at these locations.

Completing a service-wide assessment of Air Force base minimum staffing needs would identify any personnel gaps and help the Air Force better manage staffing at U.S. bases as it assigns personnel from those bases to deployment groups like ATFs to serve in overseas locations. Assessing gaps and potential risks from reduced in-garrison support could also help base commanders develop plans and ways to address or mitigate risk to their installations from reduced staffing.

Air Force Efforts to Implement AFFORGEN Partially Align with Some but Not All Selected Leading Reform Practices

The Air Force’s ongoing efforts to implement AFFORGEN partially align with some selected leading agency reform practices and do not align with others. Our prior work on agency reforms and reorganizations provides leading practices for agencies—like the Air Force—to follow during a reform process.[33] Generally, agencies can use these leading reform practices to assess the development and implementation of organizational changes.

The Air Force’s efforts partially aligned with six leading reform practices and did not align with the remaining two (see table 1). For a detailed discussion of the leading agency reform practices and our assessments, see appendix I.[34]

|

Leading reform practice |

Extent Air Force’s efforts aligned |

Summary of findings |

|

Establishing Goals and Outcomes |

◒ |

· The Air Force has issued visionary statements, but it has not codified any of them as outcome-oriented goals of AFFORGEN. · Air Force officials frequently cite the deployment-to-dwell ratio as a potential performance measure, but the Air Force has not codified this metric (or others) as performance measures to assess AFFORGEN. |

|

Involving Employees and Key Stakeholders |

◒ |

· According to Air Force officials, the Air Force initially communicated information about AFFORGEN to personnel mainly through high-level briefings and intermittent emails. However, Headquarters Air Force (HAF) officials noted that the Air Force recently developed a two-way, continuing communications strategy with its personnel by seeking their feedback about the cyclical process. |

|

Using Data and Evidence |

○ |

· The Air Force did not use data or develop a business case or cost-benefit analysis to design and justify the implementation of AFFORGEN. Instead, Air Force officials justified the transition to AFFORGEN by acknowledging that their method of deploying personnel under the Air Expeditionary Force process was not sustainable in preparation for a potential conflict with a near-peer competitor. |

|

Addressing High-Risk Areas and Longstanding Management Challenges |

◒ |

· The Air Force has shown leadership commitment in its implementation of AFFORGEN but has not issued an implementation plan, fully monitored the reform, and showed demonstrated progress. |

|

Leadership Attention and Focus |

◒ |

· Published Air Force guidance designates HAF A3 as the entity to lead the implementation of AFFORGEN. · While HAF A3 and other offices are tasked with implementing AFFORGEN, the guidance has not clearly defined implementation needs, to include staffing, resources, and change management considerations. |

|

Managing and Monitoring |

○ |

· The Air Force has not published an implementation timeline to show its transition to Expeditionary Airbases, Air Task Forces (ATFs), and Deployable Combat Wings (DCWs) as key milestones in AFFORGEN’s implementation. · According to Air Force officials, the service introduced different tools and systems to collect AFFORGEN-related data. However, it has neither officially selected nor codified any of these tools or systems as resources for AFFORGEN. |

|

Employee Engagement |

◒ |

· • According to Air Force officials, the service has shown improvements in engaging personnel during the implementation of ATFs, and HAF A3K officials have stated that this deliberate engagement will continue with DCWs. However, the Air Force has not yet codified its intention to do so. |

|

Strategic Workforce Planning |

◒ |

· According to HAF officials, their office has coordinated with the Air Force Installation and Mission Support Center to conduct ATF site surveys and intends to conduct similar site surveys for DCWs. · However, the Air Force has not completed a service-wide assessment of its minimum base staffing needs. |

● - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN fully aligned with leading reform practice.

◒ - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN partially aligned with leading reform practice.

○ - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN did not align with leading reform practice.

Source: GAO analysis of Air Force information. I GAO‑25‑107017

|

Air Force Major Command Perspectives on AFFORGEN Guidance Over the course of site visits to three major commands—Air Combat Command, Air Force Global Strike Command, and Air Mobility Command—and meetings with their subordinate units, we heard feedback on the limitations of AFFORGEN-related guidance. Here are some examples: “Policy by PowerPoint presentations and emails” “Concept ahead of Air Force processes” “Speed of change faster than speed of communication” Source: GAO interviews. | GAO‑25‑107017 |

Air Force officials at the MAJCOM and wing levels told us that given the magnitude of this major organizational change, they need more comprehensive guidance from HAF. In the absence of such guidance, there has been uncertainty and confusion across the service regarding AFFORGEN. In some instances, there also has been disagreement between the Air Force and some MAJCOMs over whether those MAJCOMs should transition their subordinate units to the AFFORGEN process at all.

Air Force officials told us that the service implemented AFFORGEN as quickly as possible to respond effectively to potential conflict with near-peer competitors and to align with the 2022 National Defense Strategy and other related doctrine. Due to the desire to rapidly implement change, the Air Force did not issue an implementation plan, according to Air Force officials. HAF A3 officials acknowledged that an implementation plan with clear goals, milestones, and performance measures might have helped them obtain support from Air Force MAJCOMs and personnel on the changes that HAF was making and better track implementation progress.

In July 2024, the Air Force published an update to its operations planning and execution instruction to incorporate the AFFORGEN process.[35] The instruction includes some guidance pertaining to AFFORGEN, including Air Force roles and responsibilities, AFFORGEN capabilities, and how AFFORGEN will be used to support the GFM process, among other information. However, the instruction does not contain a clear implementation plan that addresses leading reform practices, including outcome-oriented goals and performance measures. Furthermore, although Air Force documentation and officials have noted the service’s intention to implement ATFs and DCWs over the next few years, the instruction still describes XABs as the “default” force package that the Air Force will offer to the Joint Staff to run airbases. It does not include any information, such as a timeline with key milestone dates, on the transition to ATFs and DCWs.[36]

Other military services have demonstrated some of these leading reform practices while implementing their force generation processes. For example, our prior work has found:

· The Navy issued an implementation plan in 2014, known as the Optimized Fleet Response Plan, that included goals for its new force generation process.[37] The goals included assigning sufficient and qualified crew by the start of the training phase and limiting individual sailor deployment lengths to acceptable levels, among others. In a 2020 update to the plan, the Navy used crewing targets from pre-existing guidance to establish performance measures to assess these goals.

· The Army has developed timelines to assess progress in implementing its force generation process known as the Regionally Aligned Readiness and Modernization Model (ReARMM).[38] These timelines include: (1) modernization schedules, used to track how Army units have been assigned to ReARMM phases; and (2) timelines that set the desired length for each ReARMM phase.

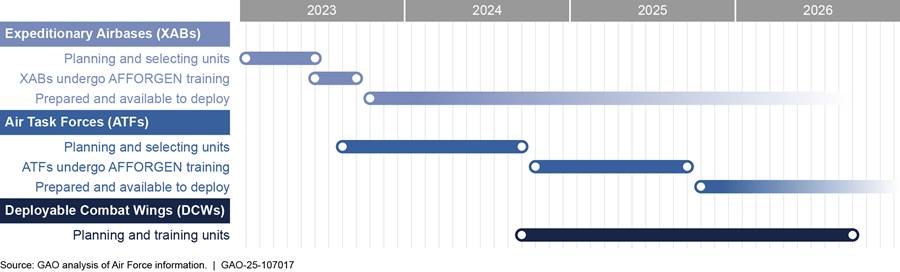

Developing an AFFORGEN implementation plan that includes outcome-oriented goals, a timeline with key milestones, and performance measures is especially important because of the dynamic nature of changing force packages and other facets of AFFORGEN. In the absence of an AFFORGEN implementation plan and timeline, we developed a notional timeline of the planned force package transition with key milestones (see fig. 6). This timeline illustrates that the Air Force will be simultaneously planning for, training, and deploying some combination of XABs, ATFs, and DCWs for at least the next 4 years.

Note: These dates are approximate as Air Force officials told us the service is still finalizing some of these dates, including deployment dates for DCWs.

As the Air Force continues to develop and refine force packages under AFFORGEN, an implementation plan would also provide personnel with an understanding of why the Air Force needs to transition its force packages to meet the goal of deploying an entire wing from the wing’s home base. Developing such a plan that includes outcome-oriented goals, a timeline with key milestones, and clear performance measures for AFFORGEN would help ensure unity of effort across the service and a shared understanding of the path forward, including any obstacles that may arise as it continues its reforms.

Conclusions

To rebuild readiness and restore predictability to its personnel, the Air Force has embarked on a transformational change to how it organizes and deploys its forces. AFFORGEN changes how the Air Force assembles and packages units for deployment, and how it trains its forces. Air Force leadership has emphasized that the Air Force must make these changes as quickly as possible to respond effectively to potential conflict with near-peer competitors.

As the Air Force moves to rapidly implement AFFORGEN, it has made iterative changes to its new force packages based on feedback. This has included taking initial steps to consolidate its UTC library, the building blocks of these force packages. These efforts will move the service towards its goal of deploying one entire wing from an airbase rather than many individual UTCs from multiple wings and airbases.

While the Air Force has made progress, we identified opportunities for the service to take additional steps including creating a plan that establishes timeframes for the UTC consolidation effort, assessing minimum staffing needs on U.S. bases, and incorporating leading reform practices into its implementation of AFFORGEN. Creating a plan that establishes timeframes for the UTC consolidation effort would ensure that the Air Force’s refinement of force packages under AFFORGEN align with its UTC library before the first DCWs deploy. Further, assessing minimum staffing needs at U.S. bases and related risks would aid Air Force leaders in managing the overall staffing on these installations. Finally, incorporating leading reform practices, such as establishing goals and outcomes, into its implementation of AFFORGEN would assist the Air Force in instituting outcome-oriented goals and evaluating its progress.

Taking these actions would help ensure a unity of effort across the service and a shared understanding of the path forward.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making four recommendations to the Air Force.

The Secretary of the Air Force should ensure that Headquarters Air Force creates a plan that establishes timeframes for the UTC consolidation effort before DCWs deploy. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of the Air Force should ensure that Headquarters Air Force, in coordination with the service’s major commands and installations, completes a service-wide assessment of U.S. Air Force base minimum staffing needs as it prepares to create in-garrison wings. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of the Air Force should ensure that Headquarters Air Force, in coordination with the service’s major commands and installations, assesses potential gaps and risks associated with reduced in-garrison support for base-related missions. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of the Air Force should ensure that Headquarters Air Force issues an AFFORGEN implementation plan that includes leading reform practices, such as outcome-oriented goals, a timeline with key milestones, and performance measures. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. In written comments on a draft of this report, DOD concurred with our recommendations, and provided steps and timeframes for implementation. DOD’s comments are reprinted in their entirety in appendix II.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of the Air Force. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-9627 or at maurerd@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Diana Maurer

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

The Air Force’s efforts to implement the Air Force Force Generation (AFFORGEN) process partially aligned with some but not all selected leading agency reform practices from our prior work. Specifically, our prior work on agency reforms and reorganizations provides leading practices for agencies—like the Air Force—to follow during a reform process.[39] The leading reform practices are organized within broad categories, including (1) Goals and Outcomes, (2) Process for Developing Reforms, (3) Implementing the Reforms, and (4) Strategically Managing the Federal Workforce. Generally, agencies can use these leading reform practices to assess the development and implementation of organizational changes.

We evaluated the Air Force’s efforts to implement AFFORGEN against eight selected leading reform practices and subcategories, which fall under all four of the broad categories.[40] We found that the Air Force’s efforts to implement AFFORGEN partially aligned with six leading reform practices: (1) Establishing Goals and Outcomes, (2) Involving Employees and Key Stakeholders, (3) Addressing High Risk Areas and Longstanding Management Challenges, (4) Leadership Focus and Attention, (5) Employee Engagement, and (6) Strategic Workforce Planning. We found that the Air Force’s efforts to implement AFFORGEN did not align with the remaining two leading reform practices of (7) Data and Evidence and (8) Managing and Monitoring.

Reform Category: Goals and Outcomes

Our prior work has shown that designing proposed reforms to achieve specific outcome-oriented goals and performance measures helps decision makers reach a shared understanding of the purpose of the reforms. Further, agreement on performance measures can help agencies determine whether the reform was successful in meeting those goals. The proposed reforms should also align with the agency’s overall mission and strategic plan, and the agency should consider how the upfront costs of the reforms would be funded.

Overall, the Air Force’s efforts to implement AFFORGEN partially aligned with the leading reform practice of Establishing Goals and Outcomes (see table 2).

|

Leading reform practice |

Extent Air Force’s efforts aligned |

Summary of findings |

|

Establishing Goals and Outcomes |

◒ |

· The Air Force has issued visionary statements, but it has not codified any of them as outcome-oriented goals of Air Force Force Generation (AFFORGEN). · Air Force officials frequently cited the deployment-to-dwell ratio as a potential performance measure, but the Air Force has not codified this metric (or others) as performance measures to assess AFFORGEN. · According to Air Force officials, the service did not provide additional funding to its major commands and their associated wings or units to meet new requirements under AFFORGEN. |

Legend:

● - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN fully aligned with leading reform practice.

◒ - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN partially aligned with leading reform practice.

○ - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN did not align with leading reform practice.

Source: GAO analysis of Air Force information. I GAO‑25‑107017

Reform Practice: Establishing Goals and Outcomes. Regarding goals, the Air Force issued several visionary statements for AFFORGEN in its briefing materials and high-level guidance. Some of these statements clearly stated how the service expects AFFORGEN to align with major defense strategies, like the 2022 National Defense Strategy and 2022 National Military Strategy.[41] Other statements define the capabilities of the AFFORGEN process, such as helping the Air Force better articulate its risk to the joint force. However, these statements are not explicitly written or codified as the goals of AFFORGEN and are not outcome-oriented, making them difficult to assess.

Similarly, the Air Force had not codified any performance measures to assess the effectiveness of AFFORGEN, as of July 2024. Air Force officials frequently cited the deployment-to-dwell ratio as being a potentially important measure to assess AFFORGEN.[42] Air Force Instruction 10-401 also states that AFFORGEN “enables” a 1:3 deployment-to-dwell ratio.[43] While the Air Force instruction states that AFFORGEN will support this 1:3 ratio, Headquarters Air Force (HAF) officials acknowledged that they do not track this metric by unit. Additionally, some Air Force officials said that this metric would not be a good measure to track progress since real world events (e.g., Israel-Hamas war) could naturally affect it.

Furthermore, according to several major commands (MAJCOM) and wing officials, the Air Force did not provide additional funding for these entities to meet new requirements under AFFORGEN. For example, Air Combat Command (ACC) officials stated that the Air Force has not provided sufficient funding for training exercises, and that MAJCOMs typically pay those costs from their budgets—not from additional funds from HAF. Likewise, Air Mobility Command (AMC) officials stated that the Air Force did not provide additional funding for new expeditionary airbase (XAB) training requirements and other certification events. AMC officials did not anticipate having to fund these changes, in addition to learning how to effectively implement them.

Reform Category: Process for Developing Reforms

Our prior work has shown that it is important for agencies to directly involve their employees and other stakeholders in the development of any major reforms.[44] It has also shown that agencies are better equipped to address challenges when managers effectively use data and evidence to assess how well the agency is achieving its goals. Further, our prior work has shown that reforms intended to improve the effectiveness of an agency often require addressing long-standing weaknesses in how the agency operates. The reform should provide an opportunity to address high-risk areas, which we evaluate using five key criteria from our prior work: leadership commitment, capacity, action plan, monitoring, and demonstrated progress.

Overall, the Air Force’s efforts to implement AFFORGEN partially aligned with the leading reform practice of Involving Employees and Key Stakeholders, did not align with the leading reform practice of Using Data and Evidence, and partially aligned with Addressing High Risk Areas and Longstanding Management Challenges (see table 3).

|

Leading reform practice |

Extent Air Force’s efforts aligned |

Summary of findings |

|

Involving Employees and Key Stakeholders |

◒ |

· According to officials from major commands, the Air Force initially communicated information about AFFORGEN to personnel through high-level briefings and emails. However, Headquarters Air Force officials noted that the Air Force recently developed a two-way, continuing communications strategy with its personnel by seeking their feedback about the cyclical process. · According to Joint Staff and combatant command officials, the Air Force continued to implement AFFORGEN without formal coordination with these entities, which are key users of Air Force units for their mission needs. |

|

Using Data and Evidence |

○ |

· The Air Force did not use data or develop a business case or cost-benefit analysis to design and justify the implementation of AFFORGEN. Instead, Air Force officials justified the transition to AFFORGEN by acknowledging that their method of deploying personnel under the prior force generation process was not sustainable in preparation for a potential conflict with a near-peer competitor. |

|

Addressing High Risk Areas and Longstanding Management Challenges |

◒ |

· Published Air Force guidance states that AFFORGEN will align force readiness and generation to build whole element capabilities and force modules for major power competition by eliminating the crowdsourcing of individual personnel and aircraft for deployments. · The Air Force has shown leadership commitment in its implementation of AFFORGEN but has not issued an implementation plan, fully monitored the reform, or shown demonstrated progress. |

Legend:

● - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN fully aligned with leading agency reform practice.

◒ - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN partially aligned with leading agency reform practice.

○ - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN did not align with leading agency reform practice.

Source: GAO analysis of Air Force information. I GAO‑25‑107017

Note: Prior to Air Force Force Generation (AFFORGEN), the Air Force brought personnel and equipment together from several wings located at various bases to meet a request for forces; a process Air Force officials referred to as “crowdsourcing.”

Reform Practice: Involving Employees and Key Stakeholders. According to MAJCOM officials, the Air Force initially communicated information about AFFORGEN to its personnel through high-level briefings, PowerPoint presentations, and emails. However, with the upcoming implementation of Air Task Forces (ATFs) and Deployable Combat Wings (DCWs), MAJCOM and wing officials told us that the Air Force improved how it engages its personnel. For example, MAJCOM officials stated that multiple MAJCOMs participated in a HAF-led meeting, known as an operational planning team, to discuss the next iteration of force packages after the first XAB deployments. Air Force officials also told us that HAF continues to use such feedback on XABs provided from MAJCOMs and units to improve ATFs.

According to HAF officials, as the Air Force continues to plan for ATFs, it has started a regular series of meetings for operational planning teams and steering groups in which officials from all MAJCOMs can discuss their views. Moreover, in April 2023, HAF tasked the Air Force Lessons Learned office at the Curtis E. Lemay Center to internally report on observations and best practices about the implementation of AFFORGEN, XABs, and ATFs. The office interviewed officials across MAJCOMs, wings, and other entities to obtain their views and issued a “lessons learned” report in December 2023, with a final report expected in fall 2024 to help inform the Air Force’s ongoing implementation of AFFORGEN.[45]

Conversely, according to Joint Staff and combatant command (COCOM) officials, these entities serve as users of the Air Force’s units to achieve the Department of Defense’s national defense goals. Although the Air Force is changing the way it presents forces to these entities, the service has not formally coordinated with them on these changes beyond high-level briefings, according to those officials. For example, a Joint Staff official told us that they understand why the Air Force changed its deployment process, but they do not understand how the service’s new force packages will align with COCOMs’ requests for aircraft. The Air Force has not clarified these details, which are relevant to the Joint Staff and COCOMs.

Reform Practice: Using Data and Evidence. The Air Force did not use data and evidence to support a business case or cost-benefit analysis of implementing AFFORGEN, or to design and justify the implementation of the cyclical process. According to Air Force officials, they knew that their method of deploying personnel under the prior Air Expeditionary Force (AEF) deployment process was not sustainable in preparation for a potential fight with a near-peer competitor. The same officials used this reasoning to justify the transition to AFFORGEN.

Reform Practice: Addressing High Risk Areas and Longstanding Management Challenges. According to Air Force officials, a longstanding management challenge that the service has faced in its deployment process is its inability to effectively articulate risk and capacity. HAF officials stated that this is due to crowdsourcing individual personnel from multiple wings and creating an extensive Unit Type Code inventory over time. With that, several Air Force officials, including those at the MAJCOM- and wing-levels, said that they recognize AFFORGEN as the service’s effort to improve its force presentation to address this longstanding challenge. The Air Force has also formalized in published guidance its intention to use AFFORGEN to address this challenge.[46]

In addition, to further assess the Air Force’s efforts to implement AFFORGEN against this leading reform practice, we evaluated whether the service’s efforts were consistent with criteria that GAO uses to resolve high-risk issues. Such criteria include demonstrating leadership commitment and capacity, having an action plan, and monitoring efforts to demonstrate progress. Overall, the Air Force has demonstrated leadership commitment in its implementation of AFFORGEN. The Secretary of the Air Force, the department’s highest-ranking official, has shown this commitment by directing HAF A3 in published guidance to lead the implementation. The Secretary of the Air Force and other high-ranking officials have also promoted the transition to AFFORGEN in several public forums and press releases. However, the Air Force has not met the other criteria for resolving high-risk issues. For example, MAJCOM and wing-level officials stated that the Air Force has not considered its internal capacity to sustain AFFORGEN (in terms of personnel and resources). Furthermore, the Air Force has not built monitoring capabilities to demonstrate continued progress, according to HAF officials.

As previously stated, another criterion for resolving high-risk issues is the development of an action (or implementation) plan. Specific to this criterion, Air Force officials at the MAJCOM- and wing-levels told us they need more comprehensive guidance from HAF, given the magnitude of this major organizational change. According to officials, the resource that could provide such guidance would be Air Force Instruction 10-401, which is the main guidance that the Air Force historically has used to codify its deployment process.[47] A December 2006 version of the instruction contained information on AEF, the prior deployment process.[48] When the Air Force began implementing AFFORGEN, it updated the instruction in January 2021 to remove AEF terminology.[49] However, this update did not include any new guidance on AFFORGEN.

In July 2024, the Air Force published an update to its instruction that has historically described how it deploys forces to incorporate the AFFORGEN process.[50] The instruction includes some guidance pertaining to AFFORGEN, including Air Force roles and responsibilities, AFFORGEN capabilities, and how AFFORGEN will be used to support the Global Force Management (GFM) process, among other information. However, the instruction does not contain a clear implementation plan that addresses leading reform practices, including outcome-oriented goals and performance measures. Furthermore, although Air Force documentation has noted the service’s intention to implement ATFs and DCWs over the next few years, the instruction still describes XABs as the “default” force package that the Air Force will offer to the Joint Staff to run airbases. It does not include any information, such as a timeline with key milestone dates, on the transition to ATFs and DCWs.[51]

Reform Category: Implementing the Reforms

Our prior work has shown that implementing major reforms can span several years. Reforms must be carefully and closely managed by designating leaders and establishing a dedicated implementation team with sufficient staffing, resources, and change management capacity to manage the reform process. Our prior work also has shown that agencies should manage and monitor the reform process using an implementation timeline with key milestones and establishing processes to collect data and evidence in accordance with the agency’s outcome-oriented goals for the reform.

Overall, the Air Force’s efforts to implement AFFORGEN partially aligned with the leading reform practice of Leadership Focus and Attention and did not align with the leading reform practice of Managing and Monitoring (see table 4).

|

Leading reform practice |

Extent Air Force’s efforts aligned |

Summary of findings |

|

Leadership Focus and Attention |

◒ |

· Published Air Force guidance designates Headquarters Air Force (HAF) A3 as the entity to lead the implementation of Air Force Force Generation (AFFORGEN). · While HAF A3 and other offices are tasked with implementing AFFORGEN, the guidance has not clearly defined implementation needs, to include staffing, resources, and change management considerations. |

|

Managing and Monitoring |

○ |

· The Air Force has not published an implementation timeline to show the transition of Expeditionary Airbases, Air Task Forces, and Deployable Combat Wings as key milestones in AFFORGEN’s implementation. · According to Air Force officials, the service has introduced different tools and systems to collect AFFORGEN-related data. However, it has neither officially selected nor codified any of these tools or systems as resources for AFFORGEN. |

Legend:

● - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN fully aligned with leading agency reform practice.

◒ - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN partially aligned with leading agency reform practice.

○ - Air Force’s implementation of AFFORGEN did not align with leading agency reform practice.

Source: GAO analysis of Air Force information. I GAO‑25‑107017

Reform Practice: Leadership Focus and Attention. As discussed earlier, the Secretary of the Air Force designated HAF A3 as the lead entity to manage the implementation of AFFORGEN. Specifically, the July 2024 update to Air Force Instruction 10-401 codified a description of the roles and responsibilities of HAF A3 and other subordinate offices as it pertains to AFFORGEN. However, although this governance structure has been clearly defined, the instruction did not describe considerations given to staffing, resources, and change management.

Reform Practice: Managing and Monitoring. As of 2023, the Air Force issued an AFFORGEN implementation timeline in its briefing documents. The timeline showed the use of force elements, to include XABs, from its initial deployment in October 2023. However, as of July 2024, the Air Force has not issued an updated implementation timeline to show the transition to ATFs and DCWs as major milestones in AFFORGEN’s implementation. Without this updated timeline with key milestone dates, the Air Force is unable to track its progress in implementing these force packages under AFFORGEN. A timeline would also inform Air Force personnel about when to expect the forthcoming changes.

In addition, the Air Force has introduced various tools and systems to collect data and evidence related to AFFORGEN, according to officials from the service. However, it has neither selected nor codified any of these tools to assess the cyclical process. For example, HAF officials told us about the Force Element Assessment Tool that the Air Force developed in 2022. These officials also stated that the Air Force conducted research and development to create this tool, which was intended to assess force element readiness under AFFORGEN. However, HAF officials acknowledged that the Air Force may no longer use the tool once it transitions to ATFs. When this transition occurs, it might then develop another tool at that time to assess unit readiness, according to the same officials.

Separately, HAF officials told us about another data system known as Envision. According to HAF officials, Envision has multiple AFFORGEN-related capabilities. For example, it leverages data analysis to help HAF make strategic decisions about the GFM process, cleans up MAJCOM-level force element data, and streamlines the AFFORGEN certification process by compiling certification data from multiple Air Force entities in a single location. While both the Force Element Assessment Tool and Envision could be beneficial tools for AFFORGEN’s purposes, the Air Force has neither selected nor codified either tool to monitor the progress of AFFORGEN’s implementation.

Reform Category: Strategically Managing the Federal Workforce

Our prior work has shown that increased levels of employee engagement can lead to better organizational performance. Essentially, agencies should plan to sustain and strengthen employee engagement both during and after a reform. Additionally, our prior work has shown that agencies should conduct strategic workforce planning preceding any staff realignments, so that changed staff levels do not inadvertently produce skills gaps or other adverse effects. In other words, such strategic workforce planning will help the agency determine if it has the needed resources and capacity, including the skills and competencies, in place for the proposed reforms.

Overall, the Air Force’s efforts to implement AFFORGEN partially aligned with the leading reform practice of Employee Engagement and partially aligned with the leading reform practice of Strategic Workforce Planning (see table 5).

|

Leading reform practice |

Extent Air Force’s efforts aligned |

Summary of findings |

|

Employee Engagement |

◒ |

· The Air Force has shown improvements in engaging personnel during the implementation of Air Task Forces (ATF), and Headquarters Air Force (HAF) A3K officials have stated that this deliberate engagement will continue with Deployable Combat Wings (DCW). However, the Air Force has not yet codified its intention to do so. |

|

Strategic Workforce Planning |

◒ |