CONFLICT MINERALS

Peace and Security in Democratic Republic of the Congo Have Not Improved with SEC Disclosure Rule

Report to Congressional Committees

October 2024

GAO-25-107018

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107018. For more information, contact Kimberly M. Gianopoulos at (202) 512-8612 or gianopoulosk@gao.gov

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107018, a report to congressional committees

October 2024

Conflict Minerals

Peace and Security in Democratic Republic of the Congo Have Not Improved with SEC Disclosure Rule

Why GAO Did This Study

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, enacted in 2010, noted that the trade of conflict minerals was helping to finance violent conflict in the DRC. Section 1502 of the act required SEC to promulgate regulations containing disclosure and reporting requirements for companies that use these minerals. SEC finalized this rule in 2012, requiring companies to begin annually filing disclosure reports in 2014. According to SEC, in requiring it to promulgate the rule, Congress sought to promote peace and security in the DRC by reducing non-state armed groups’ revenue from the mining and trade of conflict minerals.

The act includes a provision for GAO to assess, among other things, the SEC rule’s effectiveness in promoting peace and security in the DRC and adjoining countries. This report examines, among other things, (1) what can be determined about the SEC disclosure rule’s effectiveness in promoting peace and security in the DRC and adjoining countries and (2) how companies responded to the rule when filing with SEC in 2023. GAO conducted statistical analyses of the SEC rule’s effect on violence in the DRC and adjoining countries. GAO also analyzed a generalizable sample of 100 company filings from 2023. GAO interviewed DRC and U.S. government officials; UN officials; experts from nongovernmental and academic institutions; and industry stakeholders and representatives of companies that filed disclosures.

SEC disagreed with some of GAO’s findings and raised concerns about some of its methodology and analyses. In response, GAO made certain adjustments that did not materially affect its findings.

What GAO Found

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) 2012 conflict minerals disclosure rule has not reduced violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and has likely had no effect in adjoining countries. The rule requires certain companies to file reports on their use of tantalum, tin, tungsten, and gold, which are mined in the DRC. GAO found no empirical evidence that the rule has decreased the occurrence or level of violence in the eastern DRC, where many mines and armed groups are located. GAO also found the rule was associated with a spread of violence, particularly around informal, small-scale gold mining sites. This may be partly because armed groups have increasingly fought for control of gold mines since gold is more portable and less traceable than the other three minerals. Further, GAO found that the number of violent events in the adjoining countries did not change in response to the SEC rule.

The SEC disclosure rule has encouraged companies to improve reporting of conflict minerals’ sources by tracking the minerals’ chain of custody, according to experts and industry stakeholders. In addition, though many factors contribute to conflict, stakeholders and experts said the rule has raised international awareness about the risks that minerals will benefit armed groups and thus support violence. Yet efforts to trace the origin of conflict minerals, especially gold, face obstacles such as smuggling.

The number of companies filing conflict minerals disclosures in 2023 increased for the first time since 2014, but many companies continued to report being unable to determine their minerals’ origins. Companies comply with the SEC rule by submitting a disclosure describing their “reasonable country-of-origin inquiries” about the origin of conflict minerals in their products. In certain circumstances, companies must then conduct due diligence to determine their conflict minerals’ source and custody. In 2023, an estimated 63 percent of companies made preliminary determinations, based on their inquiries, about their conflict minerals’ origins. Of those that then performed due diligence, an estimated 62 percent reported being unable to determine the minerals’ source.

Abbreviations

ACLED Armed Conflict Location and Event Data

ADF Allied Democratic Forces

ASM artisanal and small-scale mining

CODECO Cooperative for the Development of the Congo

Dodd-Frank Act Dodd-Frank

Wall Street Reform and Consumer

Protection Act

DRC Democratic Republic of the Congo

DHS Demographic and Health Survey

EDGAR Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval

FARDC Armed

Forces of the Democratic Republic of the

Congo

FDLR Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda

FNL National Liberation Forces

IPSA independent private sector audit

MONUSCO United

Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in

the Democratic Republic of the Congo

MSF Doctors Without Borders

MSPE mean squared prediction error

OECD Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and

Development

RCOI reasonable country-of-origin inquiry

RED-Tabara Resistance for Rule of Law in Burundi-Tabara

RMAP Responsible Minerals Assurance Process

SEC U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

UN United Nations

USAID U.S. Agency for International Development

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

October 7, 2024

Congressional Committees

For more than 20 years, conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has contributed to severe abuses of human rights and the displacement of millions of people, according to the United Nations (UN) and the Department of State.[1] Despite attempts by the U.S. government and the international community to improve peace and security, armed groups from the DRC and neighboring countries continue to clash with Congolese security forces—the DRC national army and police—and with each other.[2] These armed groups and members of the Congolese security forces have also perpetrated violence, including sexual violence, against civilians. Various sources have reported that armed groups also continue to profit from the exploitation of “conflict minerals”—tantalum, tin, tungsten, and gold—by, for example, taxing miners to access the mines.

In July 2010, Congress passed, and the President signed into law, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act).[3] The act included provisions requiring the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to promulgate regulations containing disclosure and reporting requirements on the use of conflict minerals from the DRC and adjoining countries.[4] In response, in August 2012, SEC adopted a rule requiring companies to file specialized reports, beginning in 2014 and annually thereafter, disclosing their use of conflict minerals.[5]

When releasing the disclosure rule, SEC noted that Congress’s intent was to promote peace and security in the DRC by attempting to inhibit armed groups’ ability to fund their activities by exploiting the trade in conflict minerals. Congress expected that reducing the use of such funding would put pressure on the groups to end the conflict, according to SEC.[6] SEC further noted that Congress wished to use the disclosure rule to raise public awareness about the sources of companies’ conflict minerals and to promote due diligence about their supply chains. One of the provision’s cosponsors expressed hope that it would help consumers and investors make more informed decisions. According to SEC, some who commented on its proposed rule predicted the disclosures would help investors understand risks to companies’ reputations.

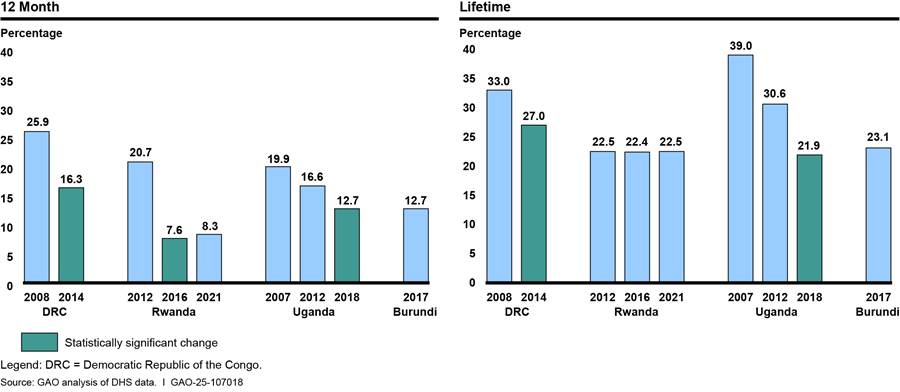

The Dodd-Frank Act includes a provision requiring us to report on the SEC disclosure rule’s effectiveness in promoting peace and security in the DRC and adjoining countries and on the rates of sexual and gender-based violence in war-torn areas of these countries.[7] We have issued 17 related reports; this is our final report in response to the statutory mandate.[8] In this report, we examine (1) what can be determined about the effectiveness of the SEC disclosure rule in promoting peace and security in the DRC and adjoining countries, (2) how companies responded to the disclosure rule when filing with SEC in 2023, and (3) what is known about the incidence of sexual violence in the DRC and adjoining countries since April 2022.

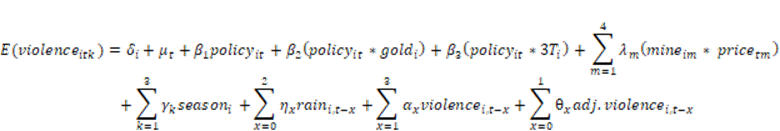

To determine the effectiveness of the SEC disclosure rule in promoting peace and security, we used statistical models to assess the rule’s effect on the number and occurrence of violent events in eastern DRC and the levels of violence in countries adjoining it.[9] To design these models, we identified and reviewed relevant empirical studies; we also interviewed the studies’ lead authors about their methodological choices. For our statistical analyses, we used data for violent events from Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) as well as data for mine locations, mineral prices, and other relevant factors.[10] We assessed the reliability of these data by reviewing relevant documents, testing the data electronically, and reviewing knowledgeable officials’ written responses to a range of questions about the data. We found the data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of conducting these statistical analyses of the rule’s effect on the number and occurrence of violent events in the DRC and the levels of violence in the adjoining countries.

In addition, we interviewed various experts—U.S. and DRC government officials, UN officials, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, and researchers—to gather qualitative information about conflict in the DRC and about the SEC disclosure rule’s effectiveness. Further, we identified and analyzed other relevant literature, including UN Group of Experts reports and studies from nongovernmental organizations, to identify other findings about the SEC disclosure rule’s effectiveness.

To describe how companies responded to the SEC disclosure rule when filing in 2023, we generated and analyzed a random sample of 100 disclosure reports from the 1,017 in SEC’s publicly available Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval database.[11] We reviewed the Dodd-Frank Act and the requirements of the SEC disclosure rule to develop a data collection instrument that guided our analysis of the filings. We also interviewed SEC officials and a nongeneralizable sample of 13 industry stakeholders to gather additional perspectives about meeting the requirements of the SEC disclosure rule. We identified stakeholders through our prior work on conflict minerals, background research on companies and organizations involved in responsible sourcing efforts, and their participation in an annual industry conference, as well as an expert referral process that included asking experts to recommend other experts.

To provide information about sexual violence in the DRC and adjoining countries since April 2022, we reviewed and analyzed relevant journal articles and reports that we identified by searching databases, using key terms and concepts.[12] We also identified and reviewed relevant case-file reports. In addition, we interviewed officials from State, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), UN agencies, and six nongovernmental organizations conducting work related to sexual violence in the DRC and adjoining countries. For more details of our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to October 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Recent History of Conflict in DRC

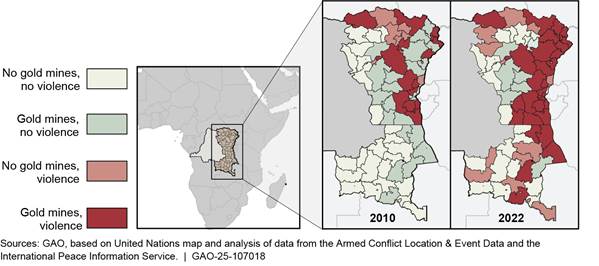

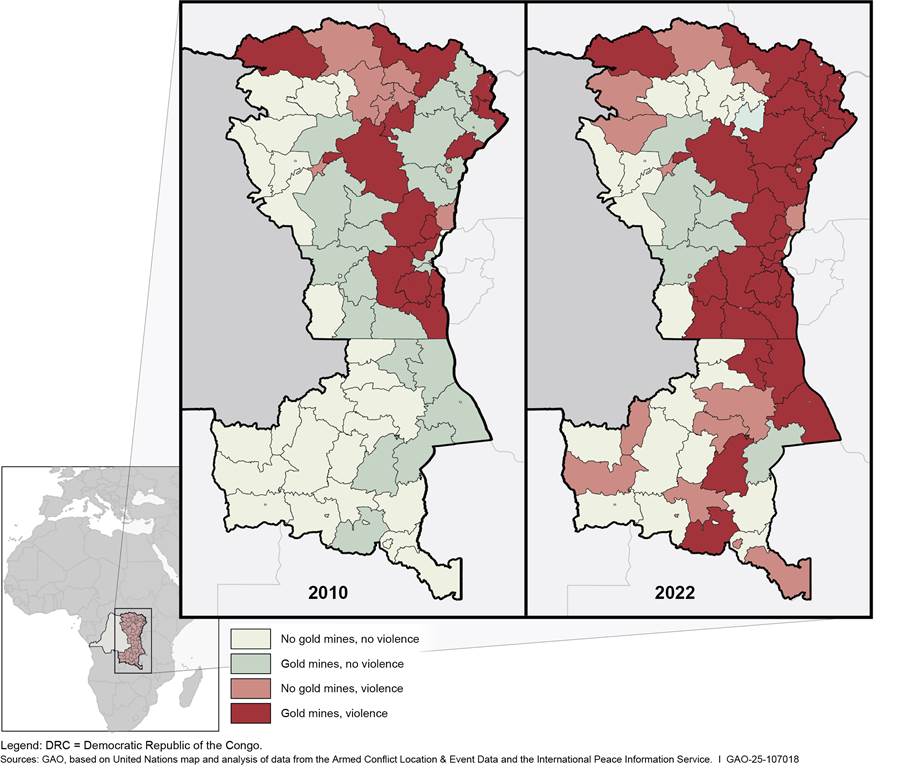

The DRC has experienced decades of political upheaval and armed conflict since achieving independence from Belgium in 1960. From 1998 to 2003, the DRC and eight other African countries fought in the Second Congo War, which resulted in the deaths of at least 3 million people in the DRC.[13] In 1999, the UN deployed a peacekeeping mission now known as the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC, or by its French acronym, MONUSCO.[14] However, armed groups continue to perpetrate violence in eastern DRC, the location of many mines that produce conflict minerals (see fig. 1).[15]

Note: The term “adjoining country” is defined in Section 1502(e)(1) of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act as a country that shares an internationally recognized border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Pub. L. No. 111-203, 1502(e)(1), 124 Stat. 1376, 2217 (2010). The adjoining countries were Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia when the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission issued its conflict minerals disclosure rule. 77 Fed. Reg. 56,274 (Sept. 12, 2012).

The Kivu Security Tracker identified an estimated 120 armed groups in eastern DRC in 2020 (the most recent data available).[16] As we reported in 2022, the size and strength of these groups tend to change over time as groups fracture, disintegrate, collaborate, or form alliances, according to experts we interviewed and reports we reviewed from the UN Group of Experts on the DRC.[17] Various sources have reported that such changes often result from internal fractures or external circumstances, such as targeting by the Armed Forces of the DRC (known by the French acronym FARDC) or by other armed groups. Groups may range in size from very small militias, with 30 or 40 combatants, to groups of more than 1,000, according to the UN Group of Experts.[18] The structure of these armed groups also varies; some groups are well organized, while others are loosely defined self-defense militias. The text box describes selected armed groups operating in eastern DRC.

|

Descriptions of Selected Nonstate Armed Groups in Eastern DRC · Allied Democratic Forces (ADF). Created in opposition to the Ugandan government, ADF established ties with ISIS is in late 2018, according to the Department of State. The U.S. government refers to ADF as ISIS-DRC and formally designated the group as a foreign terrorist organization in 2021. This well-organized group includes recruitment and support networks, according to the United Nations (UN) Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The Ugandan military, in collaboration with the Congolese military, has been fighting ADF in the DRC since late 2021. · Cooperative for the Development of the Congo (CODECO). In 2017, CODECO emerged as a decentralized association of ethnic Lendu militias in Ituri Province, according to the International Crisis Group. In 2024, CODECO’s spokesperson claimed that the group’s various factions were coordinated and commanded by headquarters and that the group would cease hostilities once its rival armed group Zaïre disarmed and the Congolese military stopped targeting the Lendu community, according to the UN Group of Experts. · Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR). Currently operating in North Kivu Province, FDLR was created in 2000 by troops belonging to the Rwandan army and various militias, according to the Kivu Security Tracker. In 2010, we reported that the group’s members included soldiers and officers from the former pro-Hutu Rwandan regime that planned and carried out the Rwandan genocide (see GAO‑10‑1030). · March 23 Movement (M23). M23 is named for the date in 2009 when the National Congress for the Defence of the People signed a peace treaty with the DRC government. M23 captured the capital of North Kivu Province in 2012 before UN and Congolese forces defeated it in 2013. Allegedly supported by Rwanda, M23 reemerged in November 2021, in part, because of a lack of progress in the DRC government’s implementation of the 2013 agreement that ended the initial rebellion, according to the UN Group of Experts. M23 claims to want to defend Congolese Tutsis against threats from Hutu groups, including FDLR, according to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. · Mai Mai militias. Mai Mai militias are numerous, disparate groups that operate as self-defense networks or criminal groups, according to the Congressional Research Service. The Kivu Security Tracker reported that approximately 40 percent of the armed groups in the region were Mai Mai militias in 2020. · National Liberation Forces (FNL). Operating in South Kivu Province, FNL had approximately 250 Burundian combatants in 2021, according to the UN Group of Experts. The Burundian government accused FNL of a coup attempt in September 2022, according to the same source. Some sources refer to the group as the National Liberation Front. · Resistance for Rule of Law in Burundi-Tabara (RED-Tabara). In 2016, the UN Group of Experts reported the RED-Tabara consisted almost entirely of Burundian citizens and was connected to the founder and leader of a Burundian political party. RED-Tabara has used South Kivu Province as a base to organize, plan, train, and launch operations across the border into Burundi and has recently been supported by Rwanda, according to the same source. · Yakutumba. Yakutumba, also known as Mai Mai Yakutumba, is a predominantly ethnic Bembe armed group created by a former Congolese military officer in 2006, according to the UN Group of Experts and Kivu Security Tracker. In 2015, the UN Group of Experts reported that Yakutumba was a well-organized group, with soldiers, a navy, intelligence services, and a political party. In 2018, the same source reported that the group operated a parallel administration, including customs and migration offices to generate revenue. · Zaïre. Zaïre began as a loosely defined self-defense militia in response to violence perpetrated by CODECO in northern Ituri Province, and it became more formalized in mid-2020, according to the Kivu Security Tracker. |

Source: GAO analysis of UN, U.S. government, and nongovernmental organization data and reports. | GAO‑25‑107018

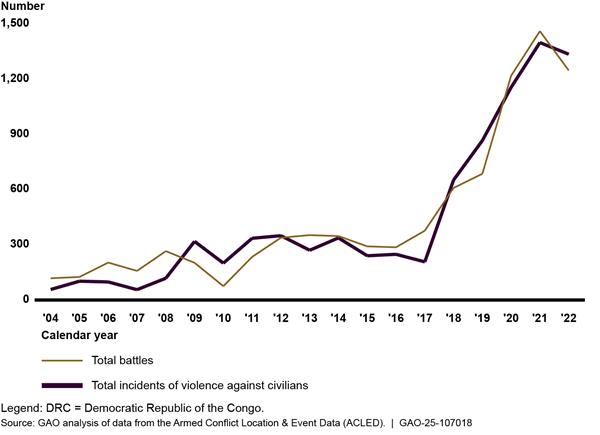

In general, the number of battles and incidents of violence against civilians in eastern DRC, remained relatively constant from 2004—after the Second Congo War—through 2016 and steadily increased from 2017 through 2021 and dropped slightly in 2022, according to ACLED data (see fig. 2).[19] Most battles occurred between armed groups and Congolese security forces.[20] As battles increased, so did incidents of violence against civilians, including attacks, sexual violence, abductions, and forced disappearances. Armed groups committed the majority of this violence against civilians, although Congolese security forces, including the military and police, were also responsible for some violence, according to ACLED data.[21]

Notes: Congolese security forces include the military and national police. According to ACLED, incidents of violence against civilians include attacks, sexual violence, abductions, and forced disappearances and do not include battles between armed groups, explosions, or remote violence.

From 2004 through 2022, battles also occurred in eastern DRC between armed groups and foreign or other forces, such as the armed forces of adjoining countries (e.g., Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda), United Nations peacekeeping forces, and private security forces, according to ACLED data. The number of these battles ranged from one to 58 annually, averaging 16 per year. ACLED data for this period also show an annual average of three incidents of violence against civilians by other armed actors, such as the state security forces of neighboring countries.

ACLED data are based on media reports, reports from nongovernmental and international organizations, selected social media accounts, and information obtained through partnerships with local conflict observatories. In 2023, one of the local organizations supplying conflict information to ACLED ceased reporting; as a result, ACLED data on events in DRC for 2023 are not comparable to such data for previous years, and we have therefore not included annual data for years after 2022.

As we reported in 2022, the increase in violence that began in 2017 was attributable in part to shifting alliances among various armed groups, the emergence of the armed group Cooperative for the Development of the Congo (CODECO), and the strengthening of a separate group, Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), according to experts we interviewed.[22] In particular, ADF and CODECO factions tend to attack civilians, whereas other armed groups focus more on theft and taxation, according to experts from a research institution. Experts added that, regardless of armed groups’ stated motives, such groups often prey on local populations and perpetrate abuses, such as raping civilians and destroying villages.

Moreover, the reemergence of the armed group M23 in November 2021 has increased conflict and violence against civilians in eastern DRC.[23] In June 2023, the UN Group of Experts reported that M23 continued to significantly expand the territory under its control and increase its attacks, despite bilateral, regional, and international de-escalation efforts.[24] To assist FARDC in its fight against M23, some armed groups created a coalition, Volontaires pour la défense de la patrie (Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland, sometimes referred to as the Wazalendo), in September 2023, according to a UN Group of Experts report.[25] The report noted that some senior FARDC officers coordinated the military’s collaboration with these armed groups, supporting them with logistics, weapons, and financing.

In December 2023, the UN Group of Experts reported that fighting between M23 and FARDC involved other Congolese and international armed actors and security forces.[26] M23 was supported by the Rwandan military, while FARDC was supported by the Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), private military companies, and the Burundian military, according to the UN Group of Experts report. State officials told us that M23 contributes to conflict in eastern DRC through its own actions and by occupying the attention of FARDC and MONUSCO, giving other armed groups more freedom of action.

As we reported in 2022, violence in eastern DRC has affected the sense of security among civilians, who are often targeted by armed groups and Congolese security forces, according to experts.[27] For example, M23 has perpetrated deadly attacks and gang rapes among civilian populations associated with, or presumed to support, FDLR and other armed groups, according to the UN Group of Experts.[28]

Civilian insecurity has led to an overall increase in the numbers of internally displaced persons and refugees from the region. An estimated 6.7 million people were internally displaced by conflict at the end of 2023, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre.[29] This estimate reflects one of the largest internal displacement crises in the world, according to the UN Group of Experts. The same source reported that M23’s territorial expansion led to the displacement of more than 1 million civilians in North Kivu Province as of April 15, 2023.

SEC Conflict Minerals Disclosure Rule

|

Uses of Conflict Minerals Various industries use the four conflict minerals—tantalum, tin, tungsten, and gold—in a range of products. For example: Tantalum is used mainly to manufacture capacitors that enable energy storage in electronic products, such as cell phones and computers, or to produce alloy additives used in turbines in jet engines. Tin is used to solder metal pieces and is found in food packaging, steel coatings on automobile parts, and some plastics. Tungsten is used in automobile manufacturing, drill bits, cutting tools, and other industrial manufacturing tools and is the primary component of light bulb filaments. Gold is used as money reserves, in jewelry, and in electronics such as cell phones and laptops. Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107018 |

In August 2012, SEC adopted its disclosure rule for conflict minerals in response to Section 1502(b) of the Dodd-Frank Act.[30] The rule requires certain companies to (a) file a specialized disclosure report, Form SD, if they manufacture, or contract to have manufactured, products that contain conflict minerals necessary to those products’ functionality or production and (b) file an additional conflict minerals report, if applicable.[31]

SEC’s Form SD provides general instructions to companies submitting a disclosure report and specifies the information that the form, in addition to a conflict minerals report, must include. According to these instructions, a company must file a conflict minerals report if, after exercising due diligence, it has reason to believe its conflict minerals may have come from covered countries and may not have come from scrap or recycled sources.[32]

The SEC disclosure rule outlines a process for companies to follow, as applicable. To comply with the rule, the process broadly requires a company to take the following steps:

1. Determine whether the company manufactures, or contracts to have manufactured, products with “necessary” conflict minerals.

2. Conduct a reasonable country-of-origin inquiry (RCOI) to determine the origin of those conflict minerals.[33]

3. Exercise due diligence, if appropriate, to determine the source and chain of custody of those conflict minerals and whether they benefited armed groups, and adhere to a nationally or internationally recognized due diligence framework, as available for these necessary conflict minerals.[34]

As adopted, the SEC disclosure rule required companies to, among other things, describe in their conflict minerals reports, if appropriate, any products “not found to be ‘DRC conflict free’” and post this information to their websites. However, an appellate court found that Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act and the rule violated the First Amendment to the extent that the statute and the rule required companies to report to SEC and disclose on their websites that any of their products have not been found to be DRC conflict free.[35]

Following the appellate court decision, the staff of SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance issued guidance in April 2014. This guidance indicated that, pending further action by SEC or a court, companies required to file a conflict minerals report would not have to identify their products as “DRC conflict undeterminable,” “not been found to be DRC conflict free,” or “DRC conflict free.”[36] The guidance also indicated that companies are not required to obtain an independent private sector audit unless they choose to describe their products as DRC conflict free in a conflict minerals report.[37]

In April 2017, after the final judgment in the case, the staff of SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance issued revised guidance.[38] This guidance indicates that, because of uncertainty about how SEC commissioners would resolve issues related to the court ruling, the division would not recommend enforcement action to the commission if companies filed disclosure only for certain items specified under the rule and did not include a description of due diligence.[39]

However, as we previously reported, SEC staff told us that the 2017 staff guidance is not binding on the commission, which can initiate enforcement action if companies do not report on due diligence in accordance with the rule.[40] The SEC Chair released a statement in 2018 confirming that SEC staff statements are nonbinding and do not create enforceable legal rights or obligations of the commission. The statement clarifies a distinction between SEC staff’s views and the commission’s rules and regulations.[41] As we previously reported, SEC staff told us that the 2017 guidance is temporary but remains in place pending the commission’s review of the rule.[42] As of June 2024, review of the rule was on SEC’s long-term regulatory agenda, meaning that any action would likely not take place within the next 12 months, according to SEC staff.

Prior GAO Reporting on Conflict Minerals

We have reported on the DRC and conflict minerals since 2010.[43] The text box summarizes our findings and recommendations from selected prior reports.[44]

|

Recommendations and Findings from Selected Prior GAO Reports about DRC and Conflict Minerals · In 2020, we reported that the Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development had implemented the U.S. conflict minerals strategy but had not established performance indicators for all of the strategic objectives. We recommended State develop performance indicators for assessing progress toward these strategic objectives. In February 2023, State said officials were considering revisions to the strategy and would develop indicators as part of any updates. See GAO‑20‑595. · In 2017, we reported that almost all artisanal and small-scale mined gold from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is produced and traded unofficially and smuggled from the country. Additionally, we reported that incentives for responsible sourcing of artisanal and small-scale mined gold were limited by the relatively small number of gold mines validated as conflict free and the DRC’s relatively high provincial mining taxes, compared with taxes in neighboring countries. See GAO‑17‑733. · In 2016, we reported that processing facilities act as “choke points” in conflict mineral supply chains and present challenges for companies filing conflict mineral disclosures. We recommended that the Department of Commerce take steps to (1) assess the accuracy of independent private sector audits; (2) establish standards of best practices for such audits; and (3) acquire the necessary knowledge, skills, and ability to carry out these responsibilities. As of February 2023, Commerce had not implemented this recommendation. See GAO‑16‑805. · In 2014, we recommended that Commerce develop and report required information about smelters and refiners of conflict minerals worldwide. Commerce sent Congress a list of all known conflict mineral processing facilities worldwide in August 2014 and subsequently published this list on its website. See GAO‑14‑575. · In 2012, we recommended that the Securities and Exchange Commission identify remaining steps and associated time frames to finalize and issue a conflict mineral disclosure rule. The commission subsequently adopted a final conflict minerals disclosure rule and published it in the Federal Register on September 12, 2012. See GAO‑12‑763. · In 2010, we recommended that State develop actionable steps the U.S. could take to help monitor, regulate, and control the minerals trade in eastern DRC. In late 2010, State updated its DRC conflict minerals strategic plan with five objectives to address linkages between human rights abuses, armed groups, mining of conflict minerals, and commercial products. See GAO‑10‑1030. |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107018

SEC Disclosure Rule Generally Has Not Reduced Violence in Eastern DRC or Adjoining Countries but Has Encouraged More Transparent Sourcing

Our statistical analyses found that the SEC conflict minerals disclosure rule has not reduced the occurrence or number of violent events in eastern DRC and was associated with a spread of violence in certain territories containing artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sites for gold.[45] Further, the rule likely had no effect on violence in the countries adjoining the DRC. Armed groups in the DRC fund their violent activities through various sources besides conflict minerals, and a number of interdependent factors, such as influence from neighboring countries and weakness in governance, contribute to conflict in the east, according to experts. The rule has encouraged companies to improve their due diligence and transparency regarding conflict minerals’ origins, according to industry stakeholders. Nevertheless, obstacles associated with smuggling and cost may limit the efficacy of efforts to trace conflict minerals’ origins, according to experts and reports by nongovernmental organizations.

SEC Rule Has Not Reduced and Likely Contributed to Spreading Violence in Eastern DRC and Likely Had No Effect in Adjoining Countries

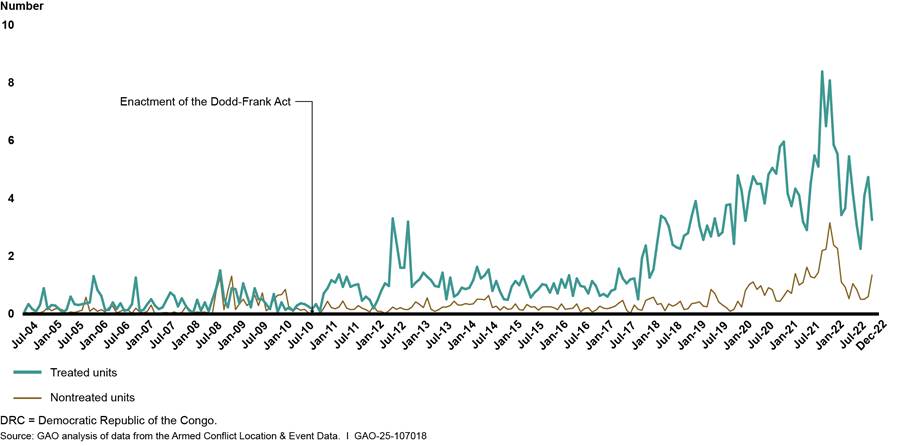

Violence in Eastern DRC Has Not Decreased with SEC Disclosure Rule

Our statistical analysis of ACLED data on violent events, data on ASM locations and mineral prices, and other data found no evidence that the SEC disclosure rule has decreased violence in eastern DRC.[46] Specifically, our analysis of data from July 2004 through December 2022 showed that the disclosure rule was not linked to a decrease in either the occurrence or number of violent events in eastern DRC.

Our analysis compared the territories that were likely to be most affected by the SEC disclosure rule with territories that were likely to be less affected by it.[47] By controlling for specific territories, our model isolated the effects of the SEC disclosure rule from factors in each territory that remained constant or slowly evolved over time, such as geographical characteristics, governance, ethnic tensions, and the presence of natural resources.[48] Additionally, by controlling for each month of the selected period, the model accounted for time-specific factors that affected the territories of eastern DRC equally, such as macroeconomic conditions and temporal proximity to elections. Further, the model controlled for specific factors that varied across territories and time that we identified as likely affecting violence, such as mineral prices, historical violence, spatial proximity of violence, and precipitation patterns. (Fig. 3 shows Congolese miners using artisanal mining techniques.)

The results of our analysis are consistent with previously published studies. For example, a 2023 study found that the probability of conflict in the DRC—specifically, violence against civilians, battles, riots and protests, and deadly conflict—roughly doubled through 2016 because of the Dodd-Frank Act.[49] The study also found evidence suggesting that the act, which required that SEC promulgate the conflict minerals disclosure rule, caused a reduction of workers employed at tantalum, tin, and tungsten mines.[50] The study’s author posits that the ability of armed groups to perpetrate violence may have increased because the labor market shock caused by changes taken in reaction to the act reduced miners’ options for earning income from mining and thus increased their incentive to join armed groups.

Similarly, a study examining the Dodd-Frank Act’s short-term effects (those prior to 2013) found that, rather than reducing violence, it increased the likelihood that armed groups would loot, and commit violence against, civilians.[51] The study’s authors suggest that the act led to displacement of armed groups, which encouraged them to replace lost revenue by looting.

SEC Rule Likely Contributed to a Spread of Violence around Gold Mines in Eastern DRC

Our analysis of ACLED and other data showed that the SEC disclosure rule was associated with a spread of violence in eastern DRC, particularly in territories with ASM sites for gold that were likely to be most affected by the SEC rule.[52] We found that violence spread primarily to these territories; we did not find a similar effect in territories containing ASM sites for tantalum, tin, or tungsten.[53] Figure 4 shows territories where violent events occurred around ASM sites for gold in eastern DRC in 2010 and 2022.

Note: We examined violent events in eastern DRC’s second-level administrative units, which consist of territories and cities. For the purposes of this report, we refer to these administrative units collectively as territories.

The results of our analysis are consistent with other academic research. For example:

· Studies published in 2017 and 2023 found that the likelihood of battles and of the presence of armed groups may have shifted away from tantalum, tin, and tungsten mines to other types of mineral mines, including gold, as a result of the Dodd-Frank Act’s requirement that SEC promulgate the conflict minerals disclosure rule.[54] The studies suggest that the act may have led to more violence around gold mines than around tantalum, tin, and tungsten mines because (1) the majority of gold mined in the DRC supplies jewelry markets in the Middle East and Asia, which are not covered by the SEC disclosure rule, and (2) gold is more difficult to trace back to mines controlled by armed groups because it is easier to melt and separate from the surrounding rock. In contrast, tantalum, tin, and tungsten are extracted with additional rock that can help identify their origins. The studies posit that because of these factors, armed groups looking to maximize their revenue moved away from tantalum, tin, and tungsten mining areas to compete over gold mining areas, thus increasing conflict.

· Another study, published in 2018, found that the Dodd-Frank Act increased battles, looting, and violence against civilians in territories with an average number of gold mines.[55] The study posits that when armed groups moved toward gold mining areas, they may have also looted and committed violence against civilians in those areas.

State reported in a 2017 cable that due diligence and traceability schemes resulting from the SEC disclosure rule led to reforms that reduced armed groups’ presence and overall criminal activity around tantalum, tin, and tungsten mining sites.[56] However, according to the cable, conflict did not decrease around gold mining sites.[57] Similarly, as we reported in 2022, armed groups have had fewer opportunities to benefit from illegal involvement in mining tantalum, tin, and tungsten as due diligence and traceability schemes for these minerals have expanded to more sites, according to the UN Group of Experts. This expansion of due diligence and traceability schemes for tantalum, tin, and tungsten has often led to measures at these sites to prove that the minerals produced are free from armed group interference. However, armed groups have continued to interfere in the mining and trade of gold, according to experts we interviewed in 2022 and the UN Group of Experts.

Security improved around tantalum, tin, and tungsten mines in part because some ASM sites were industrialized following the SEC disclosure rule, according to a conflict minerals expert.[58] Citing the examples of an industrial gold mine and an industrial tin mine, the expert explained that the armed groups left the areas when these mines became industrialized, which improved public security. A 2019 study found that the expansion of industrial mines reduced the number of battles among armed groups.[59] To protect their investments from armed groups, industrial mining companies tend to maintain strong security apparatuses, supported by FARDC and mining police. Figure 5 shows an industrial tin mine in the DRC.

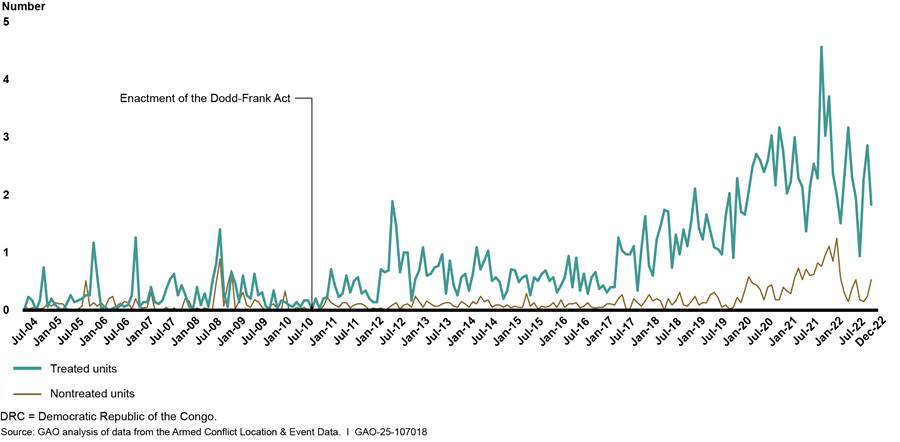

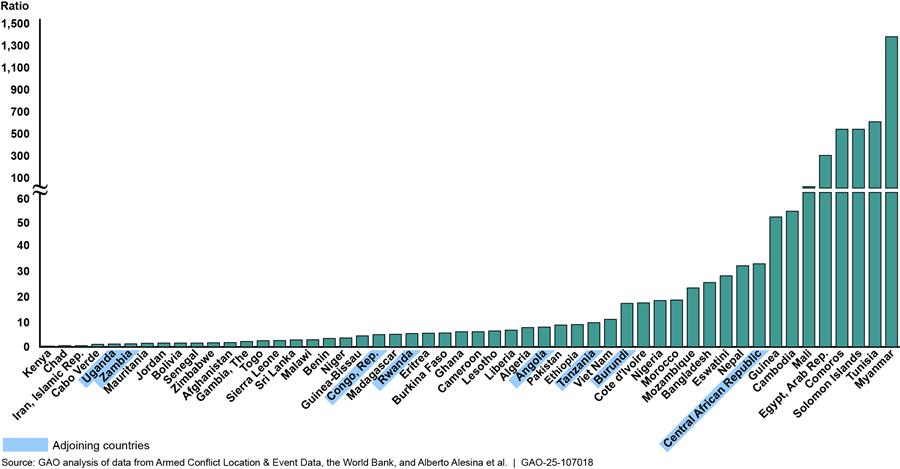

Violence in Countries Adjoining DRC Was Likely Not Affected by SEC Disclosure Rule

We conducted a separate statistical analysis, using data on violent events from January 2004 through August 2015, and found that the number of violent events in the countries adjoining the DRC likely did not change in response to the SEC disclosure rule.[60] Although ASM sites for tantalum, tin, tungsten, and gold, as well as armed groups and conflict, are largely concentrated in eastern DRC, the disclosure rule also addresses conflict minerals sourced from the adjoining countries. Thus, we assessed the rule’s effect on violence in Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia.[61] Our analysis showed that changes in levels of violence in these countries were similar to changes in other low-income and lower-middle-income countries where the SEC disclosure rule does not apply.[62]

Factors Besides Minerals Contribute to Conflict in Eastern DRC

Armed Groups Finance Violent Activities through Various Sources besides Conflict Minerals

Although SEC, in promulgating the disclosure rule, stated that Congress intended for the rule to reduce funding for armed groups in eastern DRC, these groups continue to finance violent activities through a variety of sources, according to experts and UN Group of Experts reports. The reports note that some armed groups continue to benefit from the trade of conflict minerals. For instance, armed groups may tax mine access as well as the mined minerals. A 2023 report from the International Peace Information Service found that armed groups were present at 29 percent of mines and that 42 percent of miners worked under armed group interference.[63] Armed groups, FARDC units, or armed criminal networks interfered at 55 percent of ASM sites for gold and 35 percent of ASM sites for tantalum, tin, and tungsten, according to the report.

In December 2023, the UN Group of Experts reported that armed groups were involved in the mining and trade of tantalum, tin, and tungsten in North Kivu Province.[64] For instance, the report stated that armed groups may charge diggers daily fees for access to mines and “security” and may require traders and pit managers to pay monthly fees.[65] The minerals are then smuggled to Rwanda or laundered into the official supply chain, according to the report.

However, armed groups also obtain funding from sources other than conflict minerals. As a conflict minerals expert explained, the absence of minerals would not end conflict in eastern DRC, because these groups would find other ways to finance their activities. Experts we interviewed for our 2022 report said that armed groups are adaptable in finding ways to fund their activities and that the groups weigh costs and feasibility when considering various revenue sources.[66]

Many armed groups raise funds through extortion unrelated to conflict minerals—that is, by taxing economic activities or transit in areas under their control, according to experts. For example, M23 taxes households, goods, and agricultural crops, either in cash or in kind, in areas it controls, according to a UN Group of Experts report.[67] Armed groups may erect roadblocks to charge for the safe passage of goods and people (see fig. 6). The UN Group of Experts reported in December 2022 that M23 earned an average of $27,000 per month through taxes imposed on pedestrians with goods leaving the DRC at a Ugandan border crossing.[68] As we reported in 2022, armed groups may also extort “protection” fees for providing security services for communities or for businesses involved in illegal trading, according to experts.

Further, armed groups raise revenue by exploiting natural resources besides conflict minerals, according to the UN Group of Experts. Reports published by the UN group have noted that some armed groups raise funds through the trade or control of wildlife products, coal, timber, and agricultural goods. Armed groups may also raise funds through looting, kidnapping for ransom, and other acts of criminality and banditry, according to experts we interviewed in 2022.

Various Interdependent Factors Contribute to Violence in Eastern DRC

Various interdependent factors described in our 2022 report—natural resource exploitation, influence from adjoining countries, ethnic tensions, weak governance, corruption, and economic pressures—continue contributing to violent conflict in eastern DRC, according to experts we interviewed.[69] These factors’ dynamics and interaction, their roles, and their relative significance vary depending on the area, according to State officials. Given the complexity and entrenched nature of conflict in eastern DRC, experts said they would not expect the SEC disclosure rule alone to meaningfully reduce violence.

Natural Resource Exploitation

Competition for land and other natural resources continues to aggravate conflict significantly in eastern DRC, according to experts we interviewed for this report.[70] As a Congolese researcher explained for our 2022 report, armed groups and military and political elites fight for control over territory to benefit from its natural resources.[71] The desire to control land and other natural resources can intertwine with ethnic tensions, influence from adjoining countries, and lack of other economic opportunities.

However, minerals do not primarily drive conflict in eastern DRC; rather, natural resources, including conflict minerals, provide revenue that sustains conflict, according to experts we interviewed. As we reported in 2010, the minerals trade is not the root cause but one of several factors perpetuating conflict in eastern DRC by providing resources to armed groups.[72] In that report, we noted that some research suggests resource exploitation is a consequence of violent conflict, rather than its cause, and may result from the breakdown of the rule of law. Further, experts told us that armed groups often form because of grievances rather than a desire to control and benefit from minerals.

Influence from Adjoining Countries

Influence from adjoining countries, particularly Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda, continues to exacerbate conflict in eastern DRC, according to experts we interviewed. Such influence can be linked to national security concerns, geopolitical aims, economic interests, and ethnic solidarity.

Some armed groups operating in eastern DRC emerged in opposition to the governments of Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda—notably, Resistance for Rule of Law in Burundi-Tabara (RED-Tabara), National Liberation Forces (FNL), FDLR, and ADF.[73] In response, these countries have conducted military incursions into eastern DRC, some without the consent of the DRC government, according to experts. In late 2021, the Ugandan and Congolese militaries began joint operations against ADF.[74] In August 2022, the Burundian and Congolese militaries also began joint operations against RED-Tabara and FNL.

The Rwandan military has provided material, operational, and logistical support to M23 as well as conducted operations in the DRC, State reported on the basis of information provided by the UN Group of Experts.[75] According to State officials, M23 would fail without Rwanda’s support. Experts associated Rwanda’s support for M23 with factors such as natural resource exploitation and competition with other adjoining countries, especially Uganda.

· Natural resource exploitation. A mining belt with one of the world’s major sources of tantalum is located in the DRC along its borders with Rwanda and Uganda. During the wars in the 1990s, the Ugandan and Rwandan militaries entered eastern DRC and seized control of mines to channel profits back to their countries, according to the U.S. Institute of Peace. Rwanda, Uganda, and, to a lesser extent, Burundi are the main conduits for smuggled gold from the DRC, while Rwanda has historically been the main exporter of smuggled Congolese tantalum, tin, and tungsten, according to the International Peace Information Service.

· Geopolitical competition. Experts said Rwanda may feel threatened by the developing Uganda–DRC relationship. For instance, the joint Uganda–DRC military operation against the ADF, together with a project to rehabilitate roads connecting the DRC and Uganda, has strained regional dynamics, according to the UN Group of Experts. In addition, the recent involvement of the Burundian military in the fight against M23 and the Rwandan military has exacerbated tensions between Rwanda and Burundi, according to the June 2024 UN Group of Experts report.[76]

Ethnic Tensions

Tensions between various ethnic groups also continue to contribute to violence in the region, especially when combined with economic pressures and influence from adjoining countries, according to experts. For example:

· Tensions between ethnic Hutus and Tutsis continue to contribute to conflict in the DRC. After Rwanda’s 1994 genocide, approximately 1 million Rwandans migrated into the DRC’s eastern region, including Hutu elements that had participated in the genocide’s planning and execution. According to UN and State officials, Rwanda perceives the DRC as having provided a safe haven for the FDLR and for original Hutu perpetrators of the genocide.

· Ethnic Lendus and Hemas fought in the Second Congo War, and tensions between them have also continued, according to the International Crisis Group. The armed group CODECO, which was formed from Lendu militias, has targeted Hema communities, according to the International Peace Information Service. However, experts have also attributed conflict between the Lendu and Hema communities in the northern part of DRC’s Ituri Province to competition for land and resources rather than ethnic tensions.

Ethnicity-based rhetoric by leaders and the media can exacerbate conflict in eastern DRC. For example, in its 2023 Human Rights Report for the DRC, State observed that media reports of Rwanda’s support for M23 have contributed to violence and discrimination against DRC populations thought to have Rwandan origins and against those perceived to support Rwanda or M23.[77]

Weak Governance

Experts we interviewed said that weak governance, often combined with corruption, continues to contribute to conflict. In 2022, we reported that the inability of weak and ineffective DRC government institutions to address citizens’ grievances or negotiate access to resources, such as land, minerals, and local power, often leads to conflict, according to experts.[78] State’s 2022 Integrated Country Strategy for the DRC notes that “decades of poor governance and elite predation have destroyed civic trust.” State officials told us that the DRC’s difficult business environment, combined with a weak judiciary, can impede investment and economic growth that could help alleviate citizens’ economic pressures.

State’s 2022 Integrated Country Strategy for the DRC also notes that the government’s security forces, including FARDC and the national police, are generally ineffective. State officials told us that FARDC has little control over eastern DRC and lacks the capacity to create and implement a strategy to defeat M23 and other armed groups.

Corruption

Corruption continues to contribute to conflict in the DRC, according to experts. In January 2024, Transparency International reported that over the past 5 years, the General Inspectorate of Finance had uncovered numerous cases of mismanagement of public funds. A UN official explained that such corruption can impede the country’s development, as public resources are captured by elites. However, public corruption cases either have not resulted in sanctions or have been overturned, according to State officials.

As we reported in 2022, some FARDC elements behave similarly to armed groups by charging illegal taxes and illegally exploiting natural resources, including gold, according to the UN Group of Experts.[79] The International Peace Information Service has found that FARDC units are the armed actors most often interfere in the mining sector and operate roadblocks.[80] A UN official observed that most FARDC soldiers are young, untrained, poorly paid, and poorly fed and that well-trained, well-equipped, well-paid forces would likely be less corrupt.

Economic Pressures

Economic pressures stemming from the region’s poverty and unemployment also continue to contribute to conflict. As we reported in 2022, legitimate economic activity and employment opportunities in eastern DRC are generally lacking apart from the mining industry.[81] High unemployment leads to increased recruitment by armed groups, according to a MONUSCO official. For example, the UN Group of Experts reported in December 2022 that M23 recruitment tactics have included promises of employment.[82] Further, a USAID official said that disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration processes have failed to provide employment opportunities to former combatants. Without employment, former combatants may be more likely to return to armed groups.

SEC Disclosure Rule Has Encouraged Transparency, but Efforts to Trace Minerals’ Origins Face Significant Obstacles

SEC Disclosure Rule Has Encouraged Companies to Improve Due Diligence and Transparency about Minerals’ Sources

The SEC disclosure rule has encouraged responsible sourcing efforts overall, according to industry stakeholders. Stakeholders said that the rule has raised awareness about minerals’ origins by requiring end-user companies to better understand their supply chains and conduct due diligence, especially when sourcing from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. An industry stakeholder explained that the rule has helped make companies aware that their supply chains can affect conditions on the ground. Some companies report on their efforts to responsibly source nonconflict minerals because the SEC disclosure rule has raised public awareness about responsible sourcing in general and the companies want to respond to their customers’ concerns, according to industry stakeholders.

Moreover, industry stakeholders and conflict minerals experts told us that the SEC disclosure rule has raised international awareness about the risks of minerals’ benefiting armed groups and contributing to conflict in the DRC. A UN official said that the SEC rule and the publicity surrounding it has helped bring attention to the problem of conflict minerals in the DRC. DRC government officials we interviewed in Kinshasa expressed appreciation for the rule’s effect in drawing attention to conflict in the DRC and minerals’ role in the conflict.

In response to concerns about conflict minerals, industry associations and others have developed traceability schemes to track the minerals’ chain of custody. A 2020 report examining the effects of these schemes on mining communities found that households in areas where such schemes operated reported less interference by undisciplined elements of FARDC.[83] Households in these areas also reported a greater presence, and more frequent activities, of state mining agents responsible for oversight, technical support, and taxation.

Incident reports from these traceability schemes can provide information about companies’ supply chain risks, according to industry stakeholders. For instance, one organization that facilitates traceability efforts in the DRC, Rwanda, and Burundi reported identifying, in a single year, 1,613 alleged incidents related to due diligence, chain of custody, corruption, security forces or armed groups, human rights, or health and safety. The organization categorized 159 of these incidents as highly serious, requiring immediate attention and possible disengagement.

According to the organization, incidents indicating supply chain risks include traceability or procedural issues related to establishing minerals’ chain of custody, bribes that influence statements of minerals’ origins, and illegal behavior by armed groups or state security officials. For example, the organization reported being informed by a DRC government agency that a Mai Mai armed group had fired shots around a mine and burnt the house of a mining police officer, kidnapped his wife and children, and stolen several motorcycles, allegedly demanding that the mining police leave the area. (Fig. 7 shows a mining police officer at a mine entrance in the DRC.)

There are also indications that industry efforts have improved transparency about conflict minerals’ sourcing. For example, in May 2024, an industry association, citing a UN Group of Experts report, alerted smelters in its assurance program and others about the risk of armed group interference in the minerals supply chain from the DRC and Rwanda. The industry association noted that, in accordance with international due diligence guidelines, any reasonable risks of direct or indirect support to armed groups through minerals sourcing necessitates mitigation efforts through disengagement.

Industry stakeholders explained that the SEC disclosure rule provides an incentive for companies to require compliance from their suppliers, including smelters and refiners, and to consider removing noncompliant suppliers from their supply chains. Some filing companies indicated in their disclosures that they may cease doing business with suppliers they believe pose a risk of supporting armed groups in the DRC or adjoining countries. In addition, some companies indicated that such provisions were included in their conflict minerals policies. However, representatives said that removing a supplier from a company’s supply chain can be challenging and slow, particularly if the company is several tiers removed from the problematic supplier. As we reported in 2020, companies have indicated that identifying viable alternatives to problematic suppliers and can be difficult and establishing new relationships can be costly and time consuming to.[84]

Some companies may use their leverage to secure cooperation from suppliers and ensure that their mineral purchases do not provide financing to armed groups, according to company representatives we interviewed. They explained that the largest companies have the purchasing power needed for such leverage.

Efforts to Trace Origins of Conflict Minerals, Especially Gold, Face Obstacles That May Limit Efficacy

Efforts to trace the origins of conflict minerals, particularly gold, face implementation challenges associated with cost and smuggling that may limit the efforts’ efficacy, according to experts and reports by nongovernmental organizations. Minerals from mine sites validated as “green” or “blue” through the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region’s regional certification mechanism may be exported legally from the DRC and its adjoining countries, including Rwanda and Uganda, according to the mechanism’s manual.[85] However, implementing this regional certification mechanism exceeds some countries’ economic capacity, according to a DRC government official.[86]

Experts we interviewed explained that validating mine sites as free of conflict or of interference from armed groups is time consuming and expensive. Many mines are located in remote, potentially insecure areas, and coordinating teams to visit and inspect them is difficult, according to experts. According to a DRC government official, inspection teams visited only about two-thirds of the country’s ASM sites from 2017 through 2021, and arranging follow-up visits to observe conditions is onerous.[87] Moreover, training certification auditors is costly, according to the official.[88]

Although traceability schemes exist for tantalum, tin, and tungsten, tracing chains of custody for gold—which is more portable, valuable, and fungible—is more difficult. Experts told us that these properties of gold, in addition to the DRC’s high taxes and fees on gold relative to neighboring countries’, incentivize smuggling. In 2021, IMPACT, a nongovernmental organization, estimated the cost—including the official 3.5 percent export tax—of legally exporting and internationally transporting gold sourced from ASM sites in the DRC at 12 percent or 19 percent of the exports’ value, depending on the province from which it is exported.[89] Although the DRC’s tax structure may appear to align or compete with those of adjoining countries, legal gold exports from the DRC are subject to additional provincial-level taxes and fees, according to IMPACT.[90]

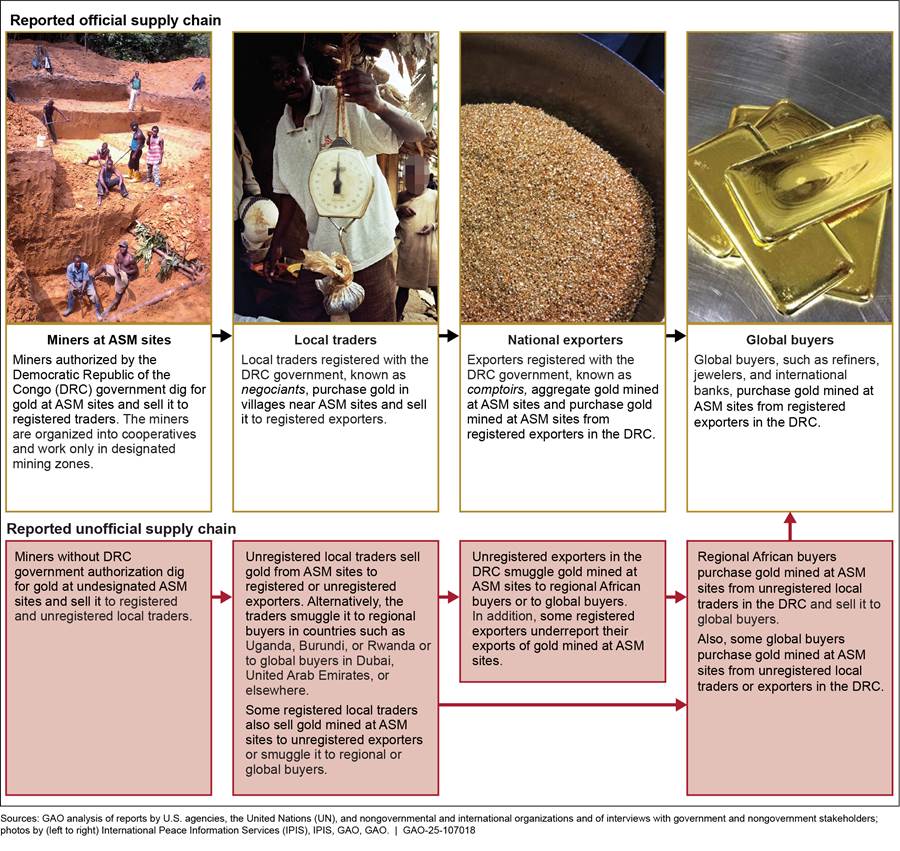

The illicit gold trade is estimated to generate more than a billion dollars annually, according to USAID. In 2019, the UN Group of Experts reported that most gold from ASM sites was smuggled out of the DRC through neighboring countries, usually destined for Dubai, United Arab Emirates.[91] In 2017, we reported that, according to USAID and UN reports and experts, gold illegally mined in or exported from the DRC can enter the official supply chain when unregistered local traders or exporters sell it to regional buyers in Burundi, Rwanda, or Uganda or global buyers in Dubai.[92] As we also reported in 2017, some factors that contribute to smuggling include corruption, inadequate infrastructure, and limited government control over the remote areas where gold from ASM sites is primarily produced, according to reports and DRC government officials. Figure 8 illustrates the official and unofficial supply chains for gold from ASM sites in the DRC.

Notes: Stakeholders we interviewed included, among others, officials of the U.S. and DRC governments and the UN Group of Experts; representatives of international and nongovernmental organizations; and representatives of gold refineries, auditing firms, local traders, and jewelers in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

“Official” refers to aspects of the supply chain where participants register or report to the DRC government. “Unofficial” refers to aspects of the supply chain where participants do not register or report to the DRC government.

Moreover, conflict minerals experts and industry stakeholders expressed concerns about the efficacy of traceability schemes—noting, for example, the persistence of problems such as fraud, corruption, and smuggling despite these schemes. Smugglers are able to circumvent traceability schemes, even those for tantalum, tin, and tungsten, according to experts. For example, the UN Group of Experts has reported evidence of smugglers’ fraudulently using documentation issued by traceability schemes to launder illicit material into the official supply.

In April 2022, Global Witness, an international nongovernmental organization, reported that the most widely used traceability scheme had permitted tantalum, tin, and tungsten from unvalidated mines, including some occupied by armed groups, to be tagged as coming from validated mines in North Kivu and South Kivu Provinces. In December 2023, the UN Group of Experts reported that due diligence for the tantalum, tin, and tungsten sectors in a territory in North Kivu Province had collapsed.[93] Armed groups widely interfered with the mining of these minerals, according to the report. In June 2024, the UN Group of Experts reported that armed groups, including M23, continued to control the minerals trade in this territory.[94] The report noted that some of these minerals were smuggled to Rwanda.[95]

More Companies Filed Disclosures in 2023, but Many Were Unable to Determine Conflict Minerals’ Origins

Number of Companies Filing Conflict Minerals Disclosures Increased for First Time since 2014

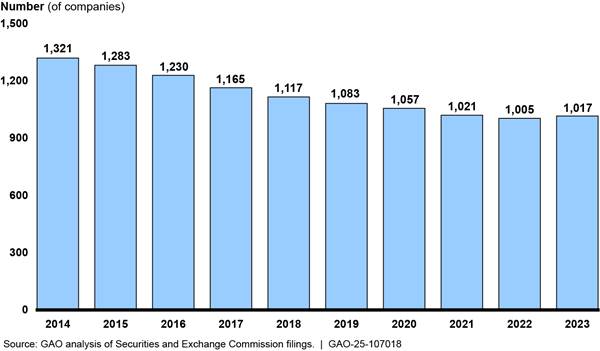

The number of companies that filed conflict minerals disclosures in 2023 was higher than the number that filed in the previous year—the first time this had occurred since 2014, when companies began filing the disclosures in response to the SEC rule (see fig. 9). In 2023, 1,017 companies filed a conflict mineral disclosure with SEC—12 more than in 2022.[96]

As figure 9 shows, the number of annual filings dropped steadily during the first 9 years, from 1,321 in 2014 to 1,005 in 2022. According to SEC officials, the decrease in the number of disclosures may have resulted from a variety of factors, including corporate mergers and acquisitions, transitions from public to private corporate ownership, and changes in business practices by companies that had previously filed. The decrease in disclosures may also reflect some companies’ perception that they are unlikely to face enforcement action by SEC for noncompliance with the disclosure rule, according to industry stakeholders including a firm that services filing companies.[97]

Percentage of Companies Reporting RCOI Determinations about Conflict Minerals’ Origins Has Risen Significantly

Our analysis of a generalizable sample of 100 disclosures filed in 2023 found that a significantly larger percentage of companies reported preliminary determinations, based on RCOIs, of their conflict minerals’ origins than in 2015.[98] Companies comply with the SEC disclosure rule by conducting an RCOI to determine whether any of the conflict minerals in their products may have originated in covered countries and may not be from recycled or scrap sources. Although the rule does not prescribe an RCOI process, many companies described conducting RCOIs in similar ways. For example, one of the filings we reviewed stated that the company had asked its suppliers to collect information about the presence and sourcing of conflict minerals used in the products supplied. We found that an estimated 97 percent of companies reported conducting an RCOI in 2023.[99] This percentage is similar to the estimated percentages that have reported conducting an RCOI since companies began filing in 2014.

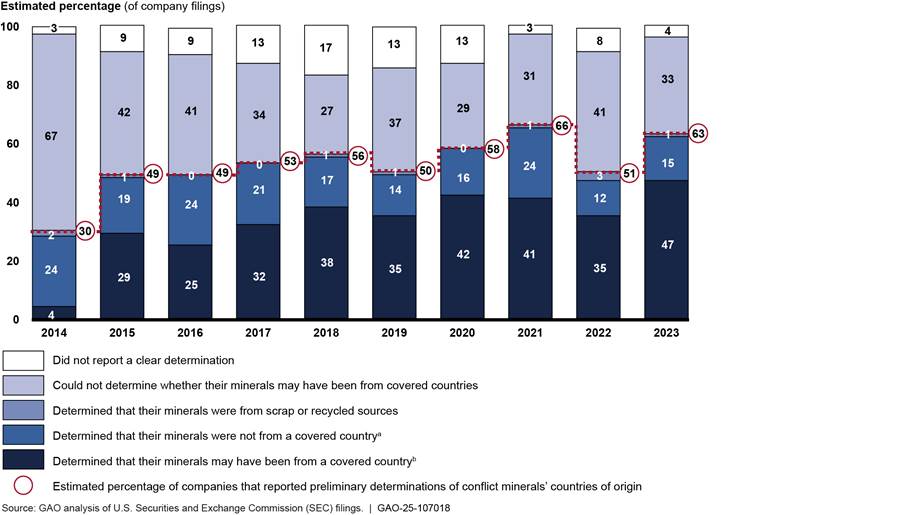

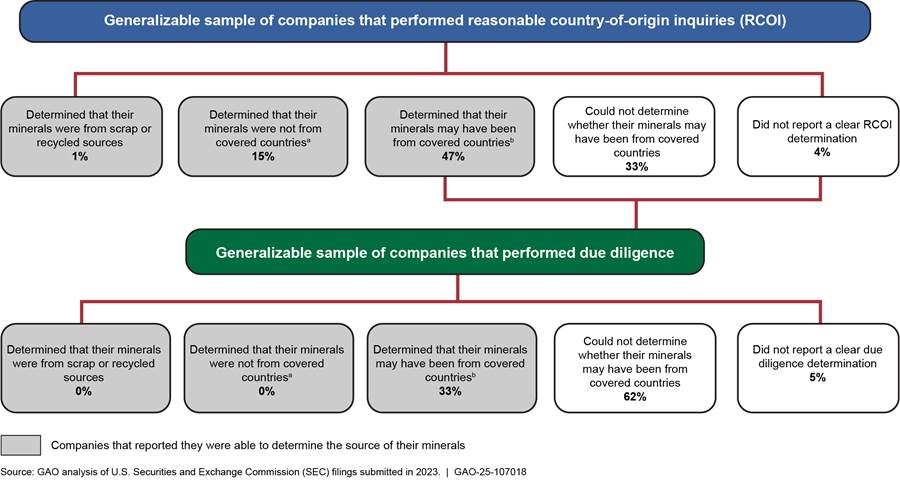

Of companies that filed disclosures in 2023, an estimated 63 percent reported preliminary determinations of their conflict minerals’ origins after conducting an RCOI—14 percentage points higher than the percentage that reported such determinations in 2015. This statistically significant increase has been driven by an increase in the percentage of companies that preliminarily determined their conflict minerals may have originated from covered countries. The percentage of companies that preliminarily determined their conflict minerals were not from covered countries or were from scrap or recycled materials has remained generally consistent since 2015.[100] Figure 10 shows the percentages of companies that reported various determinations about their conflict minerals’ sources after conducting RCOIs from 2014 through 2023.

Notes: To comply with the SEC’s conflict minerals disclosure rule, companies conduct a “reasonable country-of-origin inquiry” to preliminarily determine whether conflict minerals used in their products may have originated in covered countries—that is, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and adjoining countries—and may not be from recycled or scrap sources. 77 Fed. Reg. 56274 (Sept. 12, 2012). “Adjoining countries” is defined in section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Pub. L. No. 111-203, 1502(e)(1), 124 Stat. 1376, 2217 (2010). For the purposes of the SEC disclosure rule, SEC refers to the DRC and its adjoining countries as “covered countries.”

Data shown are estimates with a margin of error of no more than plus or minus 10 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level.

Percentages shown for each year may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

aA determination that conflict minerals are not from a covered country means that the filing company determined either that (1) the conflict minerals in its products did not originate in a covered country or (2) it had no reason to believe the conflict minerals originated in a covered country.

bA preliminary determination that conflict minerals may have been from a covered country means the company conducted a reasonable country-of-origin inquiry and determined that it knew or had reason to believe the conflict minerals in its products originated in a covered country.

Our analysis of disclosures filed by companies that conducted an RCOI in 2023 found the following:

· An estimated 47 percent of the companies reported having preliminarily determined that conflict minerals in their products may have come from covered countries.

· An estimated 33 percent of the companies reported that after conducting an RCOI, they were preliminarily unable to determine whether any of their conflict minerals may have originated in covered countries.

· An estimated 15 percent of the companies reported having determined that the conflict minerals in their products did not come from covered countries.

· An estimated 1 percent of the companies reported having determined that all conflict minerals in their products came from scrap or recycled sources.[101]

Most Companies That Performed Due Diligence in 2023 Could Not Determine Origin of Conflict Minerals

A majority of the companies that conducted due diligence to determine the source of their conflict minerals reported being unable to make such a determination. The SEC disclosure rule requires a company to exercise due diligence on the source and chain of custody of its conflict minerals and provide a conflict minerals report, if its RCOI gives reason to believe that any necessary conflict minerals may have originated from covered countries and may not have come from recycled or scrap sources. Our analysis of disclosures filed in 2023 found that an estimated 94 percent of the filing companies conducted due diligence after conducting an RCOI.[102] This percentage is higher than the percentages that conducted due diligence in 2022 and 2021, although the differences are not statistically significant.

As figure 11 shows, our analysis determined that an estimated 62 percent of companies that conducted due diligence reported being ultimately unable to determine whether the conflict minerals in their products originated in covered countries. An estimated 33 percent of companies that conducted due diligence determined that their minerals may have originated in covered countries, and an estimated 5 percent did not clearly report a determination. None of the companies that conducted due diligence reported that their minerals were not from covered countries, and none reported that their minerals came from scrap or recycled sources.

Notes: To comply with the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) conflict minerals disclosure rule, companies conduct a “reasonable country-of-origin inquiry” to preliminarily determine whether conflict minerals used in their products may have originated in covered countries—the Democratic Republic of the Congo and adjoining countries—and may not be from recycled or scrap sources. 77 Fed. Reg. 56274 (Sept. 12, 2012). “Adjoining countries” are defined in section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Pub. L. No. 111-203, 1502(1), 124 Stat. 1376, 2217 (2010). For the purposes of the SEC disclosure rule, SEC refers to the DRC and its adjoining countries as “covered countries.”

We randomly sampled 100 of the 1,017 Forms SD submitted in 2023 to create estimated results generalizable to the population of all companies that filed in response to the SEC disclosure rule. Data shown are estimates with a margin of error of no more than plus or minus 10 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level. In addition to the data shown, an estimated 0 percent of companies that performed due diligence determined that their minerals were not from covered countries, and an estimated 0 percent reported that all of their conflict minerals were from scrap or recycled sources.

aA determination that conflict minerals were not from a covered country means the company determined that (1) the conflict minerals in its products did not originate in a covered country or (2) it had no reason to believe the conflict minerals originated in a covered country.

bA determination that conflict minerals may have been from a covered country means the company determined that it knew or had reason to believe the conflict minerals in its products originated in a covered country.

Of companies that performed due diligence, 15 percent reported that they were able to determine whether conflict minerals in their products benefitted or financed armed groups. This percentage is higher than the percentage that reported this information in 2022 and 2021, although the difference is not statistically significant. All companies that reported such a determination also reported that their conflict minerals did not benefit armed groups.

Most Companies Used Standard Tools and Programs in 2023 to Support Due Diligence Efforts, but Limitations Persisted

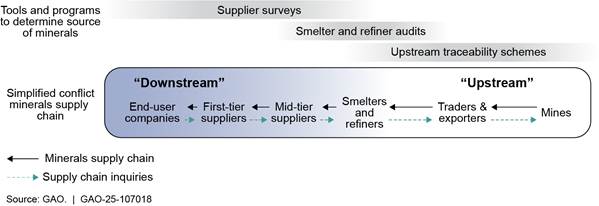

Most companies that submitted disclosures in 2023 used standardized tools and programs to determine the sources of their conflict minerals and to assess the risk that the trade of these minerals had benefitted armed groups, according to our analysis and industry stakeholders. These tools and programs generally fall into one of three categories:

· Supplier surveys. Companies may survey their suppliers to trace conflict minerals back through the supply chain to the smelters or refiners that processed them.

· Smelter and refiner audit programs. Companies may use smelter and refiner audit programs to ascertain whether the processing smelters and refiner sourced the conflict minerals responsibly.

· Upstream traceability schemes. Companies may use these schemes to trace minerals through the upstream portion of their supply chain—that is, from the mines, traders, and exporters to the smelters and refiners. They may also use the schemes to identify risks such as human rights abuses and interference by armed groups.

Figure 12 shows these three categories of tools and programs in relation to a simplified conflict minerals supply chain.

Supplier Surveys

To collect information about the presence and source of conflict minerals in their products, some companies survey the suppliers in the downstream portion of their supply chains. According to our analysis, an estimated 95 percent of companies reported surveying suppliers. Among companies that reported using a supplier survey, 93 percent indicated using the Conflict Minerals Reporting Template.[103]

However, using supplier surveys to determine minerals’ origins may involve challenges, according to industry stakeholders and filings we reviewed. Our analysis of companies’ 2023 disclosures found that an estimated 66 percent of companies identified navigating complex supply chains or not receiving product-level information as a challenge. For example:

· Collecting supply chain information, including through a supplier survey, can be difficult for companies that are many tiers removed from the processing smelter or refiner, according to industry stakeholders. We have previously reported that, according to an industry stakeholder, companies may work with about 1,000 suppliers throughout many tiers in the supply chain.[104] Industry stakeholders told us that some supply chains, such as those for electronics components, feature arrangements in which products cycle between two or three facilities repeatedly before advancing to the next stage, making it difficult to identify minerals’ chain of custody.

· Some suppliers completing the survey provide information about all of their products, regardless of whether they supplied these products to the company requesting the survey, according to industry stakeholders. Consequently, the company may receive sourcing information that is not relevant to its products.

· Suppliers’ lack of response to survey requests may hamper the use of surveys. An industry stakeholder told us that some distributors did not complete the surveys, arguing they did not need to participate because they were not the manufacturer. Our analysis of companies’ 2023 disclosures found that among companies that conducted a survey, an estimated 42 percent reported a response rate of less than 100 percent.

· Suppliers may respond to survey requests but provide incomplete or erroneous information. Our analysis of 2023 disclosures found that an estimated 43 percent of companies identified incomplete or inaccurate survey responses as a challenge. Some companies that reported receiving such responses described directing the suppliers to training resources to improve their understanding of reporting requirements.

Smelter and Refiner Audit Programs

To better understand risks associated with smelters and refiners, many companies refer to information provided by smelter and refiner audit programs. These programs provide companies with reasonable assurance that conflict minerals sourced from a particular smelter or refiner did not benefit or finance armed groups. As we reported in 2016, smelters and refiners represent a “choke point” in the supply chain because a limited number of such facilities process conflict minerals worldwide.[105]

Some smelter and refiner audit programs, such as the Responsible Minerals Assurance Process (RMAP), maintain lists of facilities found to conform to the program’s responsible sourcing standards.[106] Filing companies often cross-reference audit program conformance lists against lists of smelters and refiners in their supply chain to determine which facilities source responsibly. According to our analysis, an estimated 79 percent of companies that filed in 2023 reported using data from a smelter and refiner audit program, such as the RMAP, as part of their efforts to determine the source of conflict minerals in their products. Further, an estimated 42 percent of companies reported the number or percentage of smelters and refiners in their supply chains that conformed to the RMAP standards.

However, industry stakeholders said that the withdrawal of some smelters and refiners from audit programs creates uncertainty about supply chain risks. An industry stakeholder told us that some smelters and refiners argue they do not need to participate in audit programs because the SEC disclosure rule does not apply to many companies that purchase conflict minerals directly from smelters and refiners. Another stakeholder said downstream companies that conduct due diligence may be putting less pressure on smelters and refiners to participate in the audit programs. On the other hand, we heard that some companies continue to require conformance from smelters and refiners. For example, one company reported removing from its supply chain all processing facilities that did not conform to RMAP standards.

In addition to providing lists of conforming processing facilities, some audit programs provide information about the countries from which smelters and refiners source minerals. This information can help companies identify the countries from which they ultimately sourced their conflict minerals and, as relates to the rule, determine whether they sourced their minerals from any covered countries.