FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE ACT

Federal Agency Efforts to Identify and Mitigate Systemic Risk from the March 2023 Bank Failures

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107023. For more information, contact Michael E. Clements at (202) 512-8678 or clementsm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107023, a report to congressional committees

Federal Agency Efforts to Identify and Mitigate Systemic Risk from the March 2023 Bank Failures

Why GAO Did This Study

In March 2023, the federal government worked to stabilize the banking sector following the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. Based on recommendations from FDIC and the Federal Reserve and in consultation with the President, the Treasury Secretary invoked the systemic risk exception in the Federal Deposit Insurance Act. This decision allowed FDIC to protect all deposits, including uninsured deposits, at both failed banks.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Act includes a provision for GAO to review Treasury’s decision. This report examines (1) steps taken by FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and Treasury to invoke the systemic risk exception for Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank; (2) the likely effects of invoking the exception for these two banks; and (3) potential unintended consequences of the systemic risk exception on the incentives and conduct of insured depository institutions and uninsured depositors and proposals that may help mitigate such effects.

GAO reviewed agency documentation; analyzed financial market and banking data; and reviewed relevant laws, proposed regulatory reforms, proposed legislation, and prior GAO reports. GAO also reviewed 18 academic articles or research studies related to the potential effects of the systemic risk exception. Additionally, GAO interviewed agency staff and four academics (selected for their expertise in financial markets and regulation).

What GAO Found

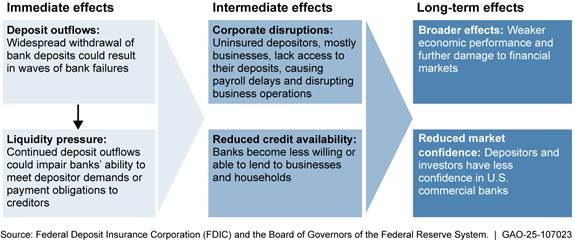

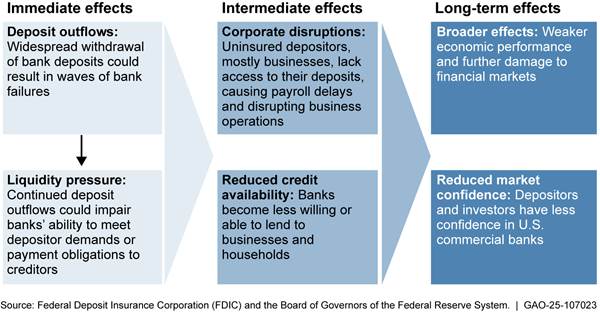

Under the systemic risk exception, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) can provide certain emergency assistance when resolving a failed bank if, upon the recommendation of FDIC and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and in consultation with the President, the Secretary of the Department of the Treasury determines that it would avoid or mitigate serious adverse effects on the economy or financial stability. FDIC and the Federal Reserve established six bases (see figure) to support their recommendations to invoke the exception for Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, which failed in March 2023. The two regulators coordinated to gather information from market participants and corporate firms. They also analyzed financial markets and economic conditions, such as bank liquidity.

GAO’s analysis found that the Treasury Secretary invoked the systemic risk exception for each of the banks after taking into consideration the regulators’ recommendations and consultations with the President. The decision was also informed by a review of Treasury staff analysis of public financial filings data and views of external parties, such as asset management firms. The decision allowed FDIC to protect all deposits at the two failed banks, including uninsured deposits.

GAO’s analysis of selected financial and economic indicators suggests that FDIC’s actions likely helped prevent further financial instability. For example, deposit outflows from commercial banks other than the 25 largest banks slowed in the week after the bank failures and stabilized the following week. How these indicators would have performed without the systemic risk exception is unclear.

Protecting all deposits can create moral hazard by reducing bank and depositor incentives to manage risk, as they may expect future bailouts, according to selected literature. Financial regulatory reforms proposed by regulators and introduced in Congress, including changes to deposit insurance and to capital requirements, may help address these concerns.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

Dodd-Frank Act |

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act |

|

FDI Act |

Federal Deposit Insurance Act |

|

FDIC |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

|

FDICIA |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991 |

|

Federal Reserve |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

|

OCC |

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency |

|

SVB |

Silicon Valley Bank |

|

Treasury |

Department of the Treasury |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 23, 2025

The Honorable Tim Scott

Chairman

The Honorable Elizabeth Warren

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable French Hill

Chairman

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

In March 2023, the federal government worked to stabilize the banking sector following the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank. Based on recommendations from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve), and in consultation with the President of the United States, the Secretary of the Treasury invoked the systemic risk exception in the Federal Deposit Insurance Act (as amended, the FDI Act).[1] This allowed FDIC to protect depositors for more than the insured portion of the deposits at the failed banks.[2]

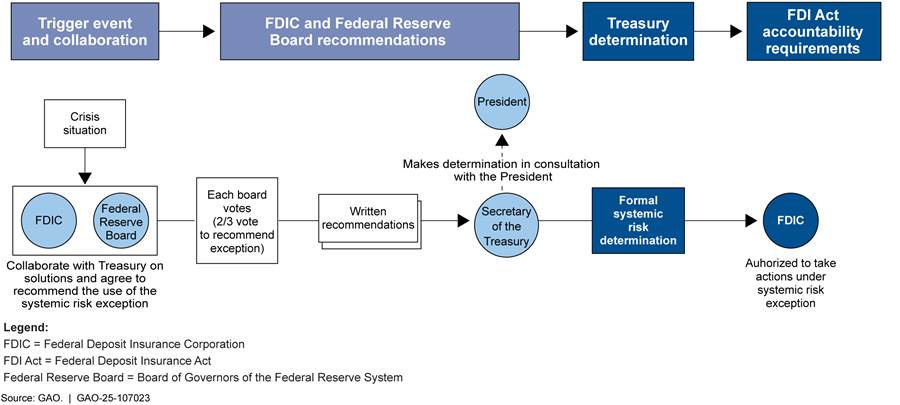

The systemic risk exception exempts FDIC from certain statutory cost limitations when FDIC winds up the affairs of an insured depository institution for which FDIC has been appointed receiver.[3] The exception is only available if the Secretary of the Treasury determines that (1) FDIC’s compliance with such cost limitations would have serious adverse effects on economic conditions or financial stability, and (2) other authorized action or assistance would avoid or mitigate such effects.[4] The Secretary of the Treasury must make the determination on the written recommendation of the FDIC and the Federal Reserve and in consultation with the President.

The FDI Act includes a provision that GAO review and report to Congress on each systemic risk determination made by the Secretary of the Treasury.[5] In this report, we examine (1) steps taken by FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and Treasury related to invoking the systemic risk exception for SVB and Signature Bank; (2) the likely effects of invoking the exception for these two banks; and (3) potential unintended consequences of the systemic risk exception on the incentives and conduct of insured depository institutions and uninsured depositors and proposals that may help mitigate such effects.

To address our first objective, we reviewed and analyzed documentation supporting Treasury’s systemic risk determinations and the recommendations made by FDIC and the Federal Reserve. We also reviewed and analyzed the coordination and communication among the regulators, Treasury, and external entities during the determination process.

To address our second objective, we collected and analyzed selected indicators of financial and economic conditions before and after the systemic risk exception was invoked for the two banks. To assess the reliability of these data sources, we reviewed relevant documentation, interviewed staff, and reviewed prior GAO work. We found that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing financial and economic conditions. We also reviewed prior GAO reports on financial regulation and systemic risk determinations.[6]

To address our third objective, we conducted a literature review on the effects of deposit insurance on moral hazard and regulatory and legislative proposals that may help mitigate such risks. For the purposes of this report, moral hazard refers to the risk that a person or entity will take on excessive risk because they have reason to believe that an insurer will cover the costs of any damages. We also interviewed four selected academics with expertise in financial markets and regulation.

For all objectives, we reviewed relevant laws, rules and regulations, and agency documentation. We also interviewed staff from Treasury, FDIC, and the Federal Reserve to understand their collaboration, decision-making, and rationale on the systemic risk determination, as well as the potential moral hazard risks of making such determinations. See appendix I for additional detail on our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

On March 12, 2023, the Secretary of the Treasury invoked the systemic risk exception with respect to SVB and Signature Bank, in two separate actions. This decision allowed FDIC to protect all deposits greater than the standard maximum deposit insurance amount of $250,000 at each of the two banks.

The process to invoke the systemic risk exception took place over roughly 2 days, as SVB and Signature Bank deteriorated rapidly and Treasury, FDIC, and the Federal Reserve worked to respond. State banking supervisors closed SVB and Signature Bank on March 10 and 12, 2023, respectively, and named FDIC as receiver for both banks. At the time of closure, SVB and Signature Bank were the 16th and 29th largest U.S. banks, respectively, and a large proportion of each bank’s deposits were uninsured.

Federal Agency Roles

Before their March 2023 failures, SVB’s and Signature Bank’s primary federal regulators were the Federal Reserve and FDIC, respectively.

· FDIC is an independent agency created to help maintain stability and public confidence in the nation’s financial system. To accomplish this mission, FDIC insures deposits; supervises insured state-chartered banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System, among others; and resolves banks and other financial institutions for which it is appointed receiver.

· The Federal Reserve is responsible for conducting the nation’s monetary policy, as well as supervising bank holding companies and state-chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System, among others. [7] Additionally, it maintains the stability of the financial system and provides a back stop to systemic risk that may arise in financial markets through its role as lender of last resort.

· The Department of the Treasury acts as a steward of U.S. economic and financial systems, broadly.

The Least-Cost Rule

Congress enacted the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991 (FDICIA) in response to an ongoing crisis among commercial banks and savings and loan associations.[8] Among other things, FDICIA amended the FDI Act to require FDIC to follow the least costly approach when resolving a troubled depository institution.[9] FDIC generally must use the method that is least costly to the Deposit Insurance Fund.[10] In addition, FDIC may not protect uninsured depositors (or creditors who are not depositors) if doing so would increase losses to the Deposit Insurance Fund.[11] We refer to these requirements collectively as the least-cost rule.

FDICIA also prescribes certain steps FDIC must take when determining which approach is the least-costly.[12] For example, FDIC must evaluate alternatives on a present-value basis, using a realistic discount rate. FDIC must also document its evaluation and the assumptions on which the evaluation is based (for example, assumptions related to interest rates or asset recovery rates).

Since the enactment of the least-cost rule, FDIC generally has resolved failed or failing banks by

1. directly paying depositors the insured amount of their deposits and disposing of the failed bank’s assets (deposit payoff and asset liquidation);

2. selling only the bank’s insured deposits and certain other liabilities, and some of its assets, to an acquirer (insured deposit transfer); and

3. selling some or all of the failed bank’s deposits, certain other liabilities, and some or all of its assets to an acquirer (purchase and assumption).

According to our prior work, FDIC has most commonly used purchase and assumption because FDIC often finds it as the least costly and disruptive alternative.[13]

The Systemic Risk Exception

FDICIA created an exception to the least-cost rule, known as the systemic risk exception. Under this exception, FDIC may resolve a troubled depository institution without complying with the least-cost rule, but only if the Secretary of the Treasury determines that (1) FDIC’s compliance with the least-cost rule would have serious adverse effects on economic conditions or financial stability, and (2) other authorized action or assistance would avoid or mitigate such effects.[14] The Secretary of the Treasury must make the determination on the written recommendation of the FDIC’s Board of Directors and the Federal Reserve Board, in each case, on a vote of not less than two-thirds of their respective board members. The Secretary of the Treasury’s determination must also be made in consultation with the President of the United States. In 2010, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) narrowed the systemic risk exception to be used only to wind up the affairs of an insured depository institution for which FDIC has been appointed receiver.[15] Figure 1 provides an overview of the steps federal agencies take when invoking the systemic risk exception.

The systemic risk exception requires FDIC to recover any resulting loss to the Deposit Insurance Fund by levying one or more special assessments on insured depository institutions, depository institution holding companies, or both, as determined by FDIC.[16]

Finally, the systemic risk exception includes requirements that serve to ensure accountability for regulators’ use of the exception. The Secretary of the Treasury must notify relevant committees of Congress in writing of any systemic risk determination and must document each determination and retain the documentation for GAO review.[17] GAO must review each determination and report its findings to Congress.[18]

Silicon Valley Bank

Founded in 1983 and headquartered in Santa Clara, California, SVB was a state-chartered commercial bank and a member of the Federal Reserve System. It was the main bank subsidiary of the SVB Financial Group (SVB’s holding company) and primarily served entrepreneur clients in technology, health care, and private equity. The bank’s deposits were mostly linked to businesses financed through venture capital. SVB had expanded into banking and financing for venture capital, adding products and services to maintain clients as they matured from their start-up phase. SVB had assets of about $209 billion and about $175 billion in total deposits at the end of fiscal year 2022. The California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation served as SVB’s state regulator, with the Federal Reserve serving as the primary federal supervisor for the bank and SVB Financial Group.[19]

On March 10, 2023, the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation closed SVB, citing inadequate liquidity and insolvency, and FDIC was simultaneously appointed receiver of the bank. In its role as receiver, FDIC initially transferred all insured deposits to the Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara and later transferred all deposits and a significant balance of the assets to a bridge bank (Silicon Valley Bridge Bank, N.A.).[20]

Signature Bank

Founded in 2001 and headquartered in New York City, Signature Bank was a state-chartered nonmember commercial bank.[21] The bank offered commercial deposit and loan products and, until 2018, focused primarily on multifamily and other commercial real estate banking products and services. In 2018 and 2019, the bank launched services to the private equity industry, such as lending to venture capital companies. Signature Bank also conducted a significant amount of business with the digital assets industry. As of the end of fiscal year 2022, the bank had about $110 billion in total assets and about $89 billion in total deposits.

As a state-chartered nonmember commercial bank, Signature Bank was regulated by the New York State Department of Financial Services, with FDIC serving as its primary federal regulator.

On March 12, 2023, the New York State Department of Financial Services closed Signature Bank, citing inadequate liquidity and insolvency, and appointed FDIC as receiver. In its role as receiver, FDIC transferred all deposits and a significant balance of the assets to a bridge bank (Signature Bridge Bank, N.A.).

Factors Leading to Bank Failures

In our prior work, we found that before their failures, SVB and Signature Bank both experienced rapid growth, less stable funding, and weak liquidity and risk management.[22]

Rapid Growth

SVB and Signature Bank grew rapidly in the years leading up to 2023. Our prior work found that between 2019 and 2021, their total assets grew by 198 percent and 134 percent, respectively, compared to a median growth of 33 percent among a group of 19 peer banks.[23] Rapid growth can be an indicator of risk for banks. From a regulatory perspective, rapid expansion raises concerns about whether a bank’s risk management practices can maintain pace with rapid growth.[24]

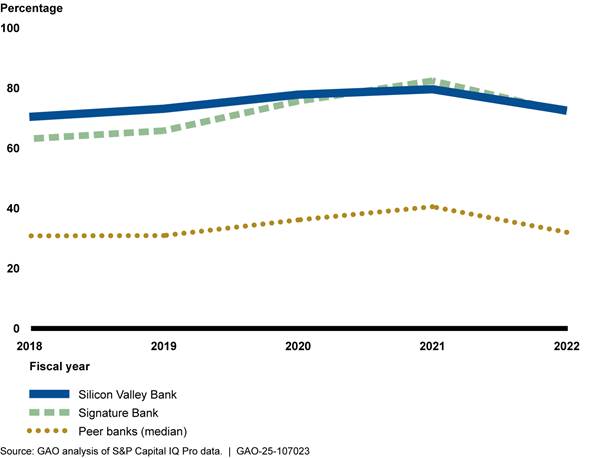

Less Stable Funding

SVB and Signature Bank reported high levels of uninsured deposits, a potentially unstable funding source, as customers with uninsured deposits may be more likely to withdraw funds during times of stress. The banks relied heavily on these deposits to support their rapid growth. At the end of fiscal year 2021, uninsured deposits accounted for 80 percent and 82 percent of total deposits at SVB and Signature Bank, respectively. Since 2018, both banks consistently reported a significantly higher proportion of uninsured deposits to total assets compared to the median for their peer banks (see fig. 2).

The two banks’ higher reliance on uninsured deposits suggests a long-standing concentration of risk. Between 2018 and 2022, SVB’s uninsured deposits ranged from 70 percent to 80 percent of total assets, while Signature Bank’s ranged from 63 percent to 82 percent. In contrast, the median uninsured deposits for a group of peer banks during the same period ranged from 31 percent to 41 percent of total assets.

Figure 2: Uninsured Deposits as a Percentage of Total Assets for Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and Selected Peer Banks, 2018–2022

Note: We developed this graphic using information from GAO‑23‑106736. Our analysis compared Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank to a group of 19 U.S.-based banks that reported deposit balances and had total assets of $100 billion–$250 billion at year-end 2022.

Weak Liquidity and Risk Management

Our prior work found that poor risk management practices and weak liquidity contributed to the banks’ failures.[25] Since 2018, FDIC had repeatedly identified weaknesses related to Signature Bank’s liquidity management framework and contingency planning. FDIC found that Signature Bank’s planning and control weaknesses prevented it from adequately identifying, measuring, and controlling liquidity risk. Additionally, Federal Reserve staff said SVB did not manage the risk from its liabilities, noting that the deposits were highly concentrated and potentially volatile.

Our previous report found that SVB’s risk management framework was not commensurate with the bank’s size and complexity. We also found that poor governance and unsatisfactory risk management practices were root causes of Signature Bank’s failure. Additionally, we found that SVB’s business strategy resulted in a concentrated client base and increasing uninsured deposits from the technology and venture capital sector.

Bank Term Funding Program

Following the failure of SVB on March 10, 2023, the Federal Reserve determined the need for an emergency lending program to boost liquidity for operating banks and minimize financial market disturbances. On March 12, Federal Reserve staff sent a memorandum to the Federal Reserve Board outlining the necessity and appropriateness of such a program. The proposed Bank Term Funding Program would allow the 12 Reserve Banks to make loans of up to 1 year to eligible U.S. depository institutions or U.S. branches or agencies of foreign banks. According to our prior work, Federal Reserve staff determined that the requirements for an emergency lending program under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act had been met.[26]

Treasury approved the establishment of the Bank Term Funding Program and pledged $25 billion in credit protection from the Exchange Stabilization Fund to the Reserve Banks in connection with the program.[27] In a memorandum to the Secretary of the Treasury, Treasury staff stated that the program as supported by the pledge would help provide market certainty and prevent broader runs on uninsured deposits by ensuring banks could cover deposit withdrawal demands without realizing losses immediately on their balance sheet. Treasury staff specified that the potential run risk on uninsured deposits posed a broader financial stability concern, rather than a localized issue limited to a small number of regional banks.

Agencies Conducted Analyses to Recommend and Invoke the Systemic Risk Exception

FDIC and the Federal Reserve Established Six Bases for Recommendations through Coordinated Analyses

FDIC and Federal Reserve staff established the bases for recommending the systemic risk exception for SVB and Signature Bank. This involved conducting analyses on financial and economic conditions, including deposit outflow and funding analyses. Staff coordinated across internal departments and with other financial regulators. Additionally, they collected information from external parties, such as market participants and corporate firms, to monitor financial markets and understand the potential effects that deposit runs on the two banks could have on the banking sector and broader economy. In coordination with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), staff focused their monitoring on certain key areas: deposit outflows, depositor behavior, liquidity position, investment portfolio, and borrowing capacity. FDIC and Federal Reserve staff also reviewed public sources to assess financial and economic conditions, such as public reports of payroll and businesses, according to agency officials.

Collectively, these actions helped FDIC and Federal Reserve staff evaluate whether complying with the FDI Act’s least-cost requirements would have serious adverse effects on economic conditions or financial stability. Their analysis found that a least-cost resolution would trigger widespread deposit outflows, potentially leading to other adverse financial and economic effects. Specifically, continued deposit outflows would intensify liquidity pressures, constrain credit availability, and disrupt business operations, as uninsured depositors, including businesses, would not be protected. Agency staff reported that this, in turn, could reduce market confidence in U.S. commercial banks and have broader negative economic effects (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: FDIC and the Federal Reserve Established Six Bases for Recommending the Systemic Risk Exception in 2023

Deposit Outflows

FDIC and Federal Reserve staff were concerned that not guaranteeing uninsured deposits at SVB and Signature Bank could trigger runs on other banks, leading to further bank failures, according to agency documentation. FDIC documentation also noted that on March 10, 2023, several banks with large uninsured deposits were having difficulty meeting customer withdrawal demands. The documentation further noted that this could be attributed either to high demand for withdrawals or losses in banks’ securities portfolios, which limited their access to additional funding.

To assess the risk of deposit runs spreading to other banks, FDIC and Federal Reserve staff also communicated with bank officials and used nonpublic reporting sources, such as information collected through supervisory channels, according to agency documentation of communications we reviewed. For example, Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC staff coordinated to obtain real-time information on deposit outflows, depositor behavior, and liquidity positions from supervised banks during the March 10 weekend. These included global systemically important banks and regional banks. Further, FDIC and Federal Reserve staff told us that they monitored public reporting sources to identify deposit outflows, such as press releases. Federal Reserve staff also collected information on the type of clients withdrawing their funds at certain banks considered susceptible as a result of the two bank failures. Federal Reserve staff also reviewed prior research on financial contagion, according to agency documentation.

Liquidity Pressure

According to agency documentation, FDIC and Federal Reserve staff were concerned that the rapid withdrawal of deposits could intensify liquidity pressure. Liquidity pressure refers to market conditions that can limit a bank’s ability to pay depositors and creditors, posing a risk to a bank’s stability. Agency staff identified liquidity pressure in the banking sector by communicating with supervised banks and analyzing nonpublic reporting sources, according to documentation of their analyses. Federal Reserve documentation indicated that many banks funded largely by uninsured deposits were under considerable pressure and that the disorderly failure of these banks could lead to greater losses in deposit markets.

In response to these concerns, during the March 10 weekend, FDIC’s Division of Risk Management Supervision increased its monitoring of banks deemed to be at higher risk of liquidity pressure. FDIC examiners were in frequent contact with these banks to understand how they were managing liquidity pressure, according to FDIC staff. The examiners also collected updated data on the banks’ securities, liquid assets, and uninsured deposits to discern changes in their liquidity risk. FDIC staff told us that examiners reported their findings to management and discussed them with the Federal Reserve and OCC during meetings.

Federal Reserve staff also coordinated across Federal Reserve Banks to collect information on banks’ use of the discount window, according to documentation we reviewed. Discount window borrowing generally provides relief for short-term liquidity pressures and can be used to gauge liquidity in the overall banking sector.[28]

Reduced Credit Availability

FDIC and Federal Reserve staff determined that a least-cost resolution of SVB and Signature Bank could result in higher lending costs. Federal Reserve staff told us that they anticipated that widespread deposit outflows and subsequent bank failures would reduce the number of banks willing or able to lend to U.S. households and businesses. This would raise lending costs for borrowers.

FDIC and Federal Reserve staff told us they drew on past experiences with liquidity crises to conclude that a least-cost resolution would reduce credit availability. They observed that in similar situations, banks would curb their lending activities as they focused on preserving their liquidity. For example, FDIC documentation shows that the agency coordinated with the Federal Reserve and OCC to monitor certain supervised banks, focusing on areas like discount window borrowing and Federal Home Loan Bank funding. Through these efforts, FDIC found that certain banks had turned to wholesale funding sources to offset deposit outflows. Because wholesale funding sources, such as brokered deposits, are generally more expensive than retail deposits, FDIC staff told us that they expected this would increase banks’ funding cost and, in turn, reduce their lending activities.

Corporate Disruptions

FDIC and the Federal Reserve determined that imposing losses on uninsured depositors at the two failing banks could cause widespread disruption across the U.S. economy and further destabilize U.S. banks, according to agency documentation. Many of these uninsured depositors were businesses, and regulators anticipated that their inability to access funds, even for a short time, would lead to payroll delays and other disruptions.

FDIC and Federal Reserve staff obtained and analyzed real-time information on depositor composition of other regional banks. FDIC found that several uninsured depositors that were initiating significant withdrawals at other banks during the March 10 weekend were corporate depositors. In the event that other large regional banks failed, they concluded that the inability of businesses to access funds would likely lead to similar payroll and payment delays. Further, Federal Reserve staff used information received from corporate firms and public news reports to assess the impact of the SVB failure on corporate operations, according to Federal Reserve staff.

Reduced Market Confidence

FDIC and the Federal Reserve found that a least-cost resolution of SVB and Signature Bank could lead market participants to reassess the risk of similar banks. The regulators expected the sudden failures of SVB and Signature Bank could also erode investors’ and depositors’ confidence in other banks. Further, in their documentation, FDIC staff reported that uncertainty surrounding the banks’ rapid deposit outflows reduced investor confidence, preventing the inflow of private capital needed to restore the industry’s financial health and facilitate new lending. FDIC staff observed that following SVB’s failure, the S&P regional banks index had its worst week since 2009, according to FDIC documentation.

FDIC and Federal Reserve staff analyzed market indicators to identify loss of market confidence in U.S. banks, according to agency documentation we reviewed. They obtained information on the credit spread movement of regional banks, observing a widening of credit spreads for these banks.[29] This indicated that investors perceived large regional banks as riskier.

Our review of documentation found that FDIC staff from the Division of Risk Management Supervision and the Division of Complex Institution Supervision and Resolution also reviewed market indicators, such as credit default swap spreads and bank stock prices, to gauge market confidence in large banks.[30] FDIC staff told us that banks with high concentrations of uninsured depositors and unrealized losses in securities were particularly susceptible to losing investor confidence. Investors wanted these banks to diversify and use different sources of wholesale funding, according to FDIC staff.

Broader Negative Economic Effects

FDIC and Federal Reserve staff concluded that a least-cost resolution of SVB and Signature Bank would lead to broader negative economic effects. They based this conclusion on their analysis of banks’ funding sources, investor confidence, and disruptions to third-party corporate operations. Federal Reserve staff told us that they also considered economic theory and prior experience on how bank strains can have spillover effects on the broader economy.

FDIC and Federal Reserve staff shared their analysis on the potential effect of SVB and Signature Bank failures on financial markets and broader economy with their management. FDIC and Federal Reserve management then shared staff analysis and updates of market conditions with their respective Board members and legal division staff. This information helped Board members decide whether to recommend the systemic risk exception to the Secretary of the Treasury. Both regulators’ legal division staff included this analysis in the materials prepared to support the recommendations, according to agency officials. Ahead of the FDIC Board of Directors meeting, FDIC legal staff shared these materials with principal staff from OCC, Treasury, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, incorporating revisions as appropriate.

The FDIC Board of Directors and the Federal Reserve Board unanimously agreed to recommend the systemic risk exception for SVB and Signature Bank. The FDIC and Federal Reserve then sent formal recommendations to the Secretary of the Treasury.

Treasury Made Its Determinations Based on Agency Recommendations and Additional Information

During the March 10 weekend, Treasury staff evaluated the recommendations from FDIC and the Federal Reserve and consulted with these agencies and OCC to assess the systemic risk stemming from the deposit runs at SVB and Signature Bank. Through discussions with the three agencies, Treasury learned that there were deposit runs occurring at additional banks over the weekend, according to Treasury staff.

Treasury staff also used public regulatory filings and other public reporting to assess the condition of the banking sector, according to documentation we reviewed. This included call report data as of December 31, 2022, which staff used to review balance sheet information and deposit profiles of certain banks, including large regional banks.[31]

Between March 10 and March 12, Treasury staff also met with various stakeholders to understand the potential impacts of the SVB failure on the banking sector and the broader economy, according to agency communications we reviewed. This included market participants, asset management firms, and venture capital industry representatives. Treasury staff also told us that representatives of similarly situated banks reached out to them. Additionally, Treasury staff said they met with a venture capital trade association to discuss the implication of losses for uninsured depositors.

Treasury staff said they met frequently with the Secretary of the Treasury during the March 10 weekend to discuss the potential implications of the failing banks on financial markets. Staff also provided the Secretary with their analyses on the FDIC and the Federal Reserve recommendations. According to the agency documentation we reviewed, Treasury staff stated that a least-cost resolution was highly likely to result in losses for uninsured depositors, which could lead uninsured depositors at other banks to withdraw their funds. This could imperil a significant source of funding for many major U.S. financial institutions. Staff recommended that the Secretary of the Treasury, after consulting with the President, invoke the systemic risk exception for both SVB and Signature Bank.

On March 12, 2023, the Secretary of the Treasury determined that FDIC’s compliance with the least-cost resolution requirements for SVB and Signature Bank would have serious adverse effects on economic conditions or financial stability. The Secretary also determined that actions by FDIC under the systemic risk exception would avoid or mitigate those effects.

According to the Secretary’s Determinations, the Secretary made this decision after considering recommendations from FDIC and the Federal Reserve, consultations with the President, criteria in the FDI Act, and other information available to the Secretary at the time.[32]

FDIC Protection of Uninsured Depositors Sought to Avert Adverse Financial and Economic Conditions

FDIC’s Actions Intended to Limit Market Disruptions and Broader Negative Economic Effects

By assisting uninsured SVB and Signature Bank depositors, FDIC intended to address immediate concerns related to deposit runs as noted earlier. The agencies anticipated that the failure of SVB and Signature Bank would result in more outflows in the deposit market. FDIC’s actions under the systemic risk exceptions allowed it to mitigate serious adverse effects on economic conditions or financial stability, according to FDIC.[33]

On March 12 and 13, FDIC transferred all deposits, including uninsured deposits, and substantially all assets of SVB and Signature Bank to newly created FDIC-operated bridge banks. In its 2023 annual report, FDIC reported that it protected and transferred an estimated $119 billion in deposits from SVB and $88.6 billion from Signature Bank.[34] According to FDIC’s final rule on the special assessment pursuant to the systemic risk determinations, approximately 88 percent of SVB’s deposits and 67 percent of Signature Bank’s deposits were uninsured at the time of the banks’ failures.[35]

Financial Conditions Stabilized by the End of March 2023

The economic and financial indicators we examined show that banking and financial conditions worsened sharply immediately after the bank failures but appeared to stabilize by the end of March 2023. We conducted a review of selected indicators to assess how economic and financial conditions performed before and after the 2023 bank failures and subsequent actions taken by regulators.

Our findings suggest that FDIC’s actions likely helped prevent further financial instability. However, it is difficult to isolate the impact of FDIC’s actions because it is not possible to know how the indicators would have performed without the use of the system risk exception. Further, the Federal Reserve’s announcement of the Bank Term Funding Program, an emergency lending facility to boost liquidity at depository institutions, coincided with the systemic risk exception. This overlap makes it impossible to separate the impact of the systemic risk exceptions from that program.

Similarly, FDIC, Federal Reserve, and Treasury assessed the effect of FDIC’s actions on the banking sector. Staff of the three agencies told us they believe that FDIC’s actions contributed to minimizing contagion in the U.S. banking system. However, FDIC and Federal Reserve staff acknowledged that it is difficult to directly attribute changes in economic conditions and depositor behavior to FDIC’s assistance.

Through their monitoring activities, the agencies observed that key contagion risks dissipated or stabilized following the emergency actions taken during the March 10 weekend. For example, the Federal Reserve’s May 2023 financial stability report found that small domestic banks initially experienced rapid deposit outflows after SVB and Signature Bank failed, but these outflows significantly slowed by the end of March.

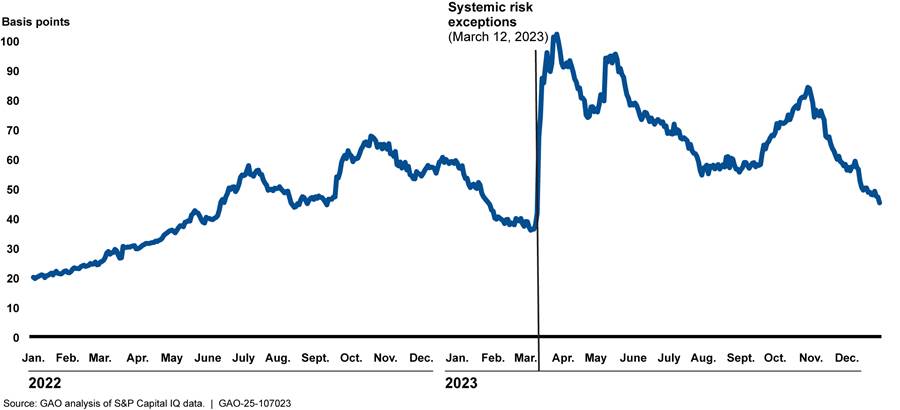

Regional Banks

Regional banks saw a sharp rise in credit risk and a decline in market prices that began after March 8. Our analysis of credit default swap spreads and S&P Regional Banking exchange-traded fund prices show that the drop in confidence in regional banks subsided by the end of March.

However, our analysis suggests that use of the systemic risk exception did not immediately restore market confidence in regional banks. Specifically, we found that credit default swap spreads of a peer group of banks similar to the two failed banks widened sharply after March 8. It continued to widen until the end of March (see fig. 4). Moreover, for the remainder of 2023, credit default swap spreads remained mostly above levels observed in 2022.

Figure 4: Average Credit Default Swap Spreads for Peer Regional Bank Holding Companies, February 2022–December 2023

Notes: The figure reflects the average of 1-year credit default swap spreads for 11 regional-bank parent companies, representing 12 of the 19 peer banks of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank identified in GAO‑23‑106736. A basis point is 1/100th of a percentage point.

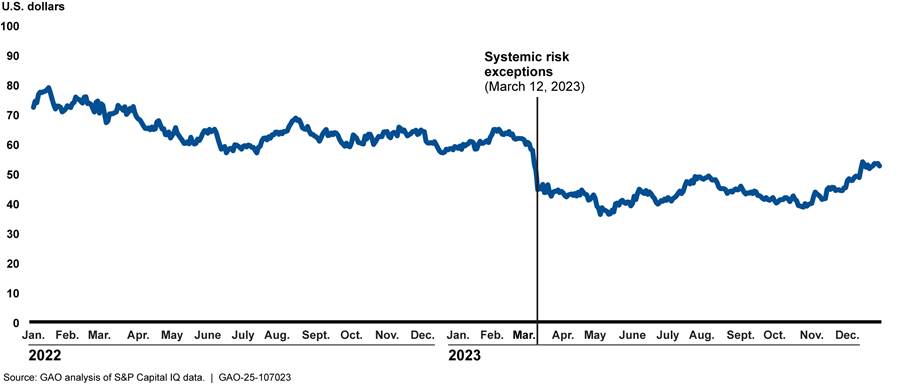

Similarly, the price of a S&P Regional Banking exchange-traded fund, which consists of a large number of regional bank stocks, declined in the days following the failures of SVB and Signature Bank. However, stock prices stabilized after March 13. By the end of 2023, the stock prices appeared to be approaching levels seen in 2022, before the bank failures (see fig. 5). Stock prices and credit default swap spreads suggest that investors still had lingering concerns about the risks and performance of regional banks at the end of 2023.

Notes: The Standard & Poor’s Depositary Receipts S&P Regional Banking Exchange-Traded Fund invests in stocks of companies operating across financial, bank, and regional bank sectors. It tracks the performance of the S&P Regional Banks Select Industry Index by using representative sampling technique.

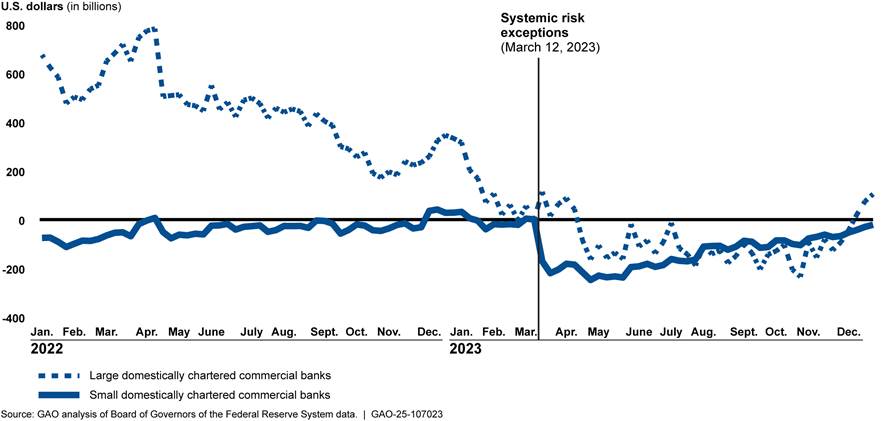

Bank Deposits

Commercial banks other than the largest 25 by total assets experienced a decline in overall deposits in the 2 weeks following March 8, before deposit levels began to recover. Between May and December, small banks saw a steady increase in deposit funding, ending the year at just below pre-bank failure levels. In contrast, large banks initially saw an influx of deposits during the week of SVB’s and Signature Bank’s failures. However, this influx was both smaller than the outflow from small banks and short-lived (see fig. 6). While deposits at large domestically chartered commercial banks had dropped significantly in 2022, they remained relatively stable between the bank failures and December 2023, when they increased slightly. Whether regulators’ actions prevented even higher deposit outflows is unclear. Overall, deposits of domestically chartered commercial banks had recovered to pre-bank failure levels by December 2023.[36]

Figure 6: Change in Deposit Levels of Domestically Chartered Commercial Banks, 2022–2023, Relative to the Week of March 8, 2023

Notes: Large domestically chartered commercial banks are defined as the largest 25 domestically chartered commercial banks, ranked by domestic asset size, based on the commercial bank call reports used to benchmark the Federal Reserve data. Small domestically chartered commercial banks are defined as all domestically chartered banks outside of the largest 25 banks.

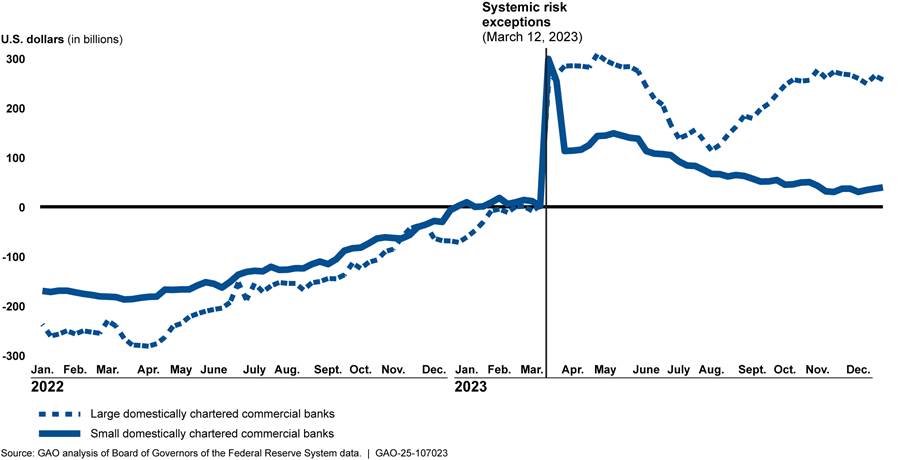

Bank Borrowings

Borrowings by both large and small domestically chartered commercial banks spiked sharply during the week of the bank failures.[37] However, while small banks’ borrowings returned to a much lower level by the end of March, large banks’ borrowings remained elevated. By the end of 2023, small banks’ borrowings had returned to levels similar to those seen in early 2023, before the bank failures. In contrast, large banks’ borrowings remained near the peak levels observed in March 2023 (see fig. 7).

Figure 7: Change in Borrowing Levels of Domestically Chartered Commercial Banks, 2022–2023, Relative to the Week of March 8, 2023

Notes: Large domestically chartered commercial banks are defined as the largest 25 domestically chartered commercial banks, ranked by domestic asset size, based on the commercial bank call reports used to benchmark the Federal Reserve data. Small domestically chartered commercial banks are defined as all domestically chartered banks outside of the largest 25 banks.

The decline in small bank borrowings in the weeks immediately after the bank failures suggests that regulator actions could have helped ease liquidity pressure faced by these institutions. While borrowings did not decrease immediately for large banks, they also did not continue to rise sharply, suggesting a different response to regulator actions. The sustained high level of borrowing by large banks suggests that they decided to take advantage of additional liquidity in the wake of the failures.

Financial Markets

Financial conditions tightened in the 3 to 4 weeks leading up to the bank failures, as measured by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s National Financial Conditions Index, and this tightening continued for another 2 weeks after the failures.[38] By the end of March financial conditions had loosened again (see fig. 8). Whether financial market conditions would have tightened further in the absence of regulators’ actions is unclear. Notably, even during the period of bank failures, financial conditions remained looser than average conditions dating back to 1971.

Notes: The National Financial Conditions Index is a weighted average of 105 measures of financial activity that provides a weekly update on U.S. financial conditions. The adjusted National Financial Conditions Index removes variation in the component indicators that is attributable to economic condition and inflation. Both indicators are constructed to have an average value of zero and a standard deviation of one over a sample period dating back to 1971. Positive values are associated with tighter-than-average financial conditions, while negative values are associated with looser-than-average financial conditions.

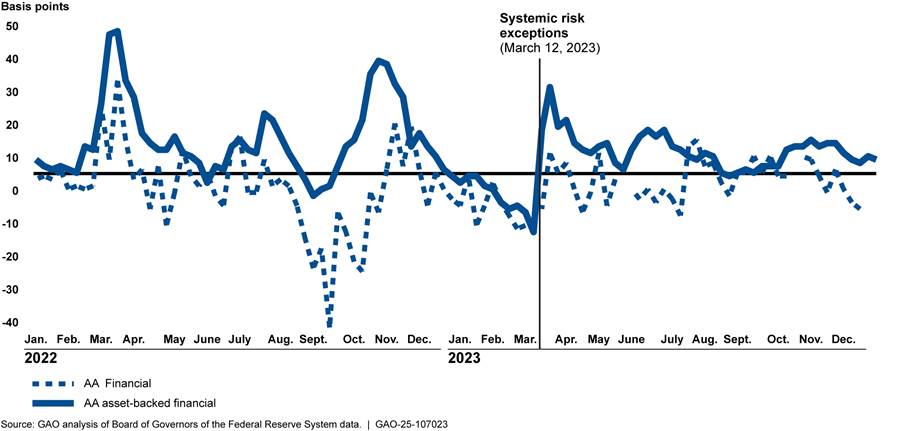

Additionally, spreads on financial commercial paper rose in the week after March 10, continued to increase for another week, and then stabilized. This stabilization suggests that regulator actions could have helped mitigate further credit restrictions for financial institutions.[39] In contrast, asset-backed commercial paper, which is often backed by loans and receivables, showed a larger initial response. This suggests that markets were concerned about potential contagion beyond the financial sector. Nevertheless, the peaks in financial commercial paper spreads in March 2023 were comparable in magnitude to several episodes in 2022, suggesting that the bank failures were not as outsized an event for large financial businesses (see fig. 9).

Notes: The figure is for weekly average of the daily rates because the rates were not reported for some days in some weeks. A rating of AA is for issuers with at least one “1” or “1+” rating, but no other ratings than “1” according to the rating agencies Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s. A line is broken if there are no data for the category on that date. A basis point is 1/100th of a percentage point. The spread is the difference between the commercial paper rate and the overnight indexed swap of the same maturity.

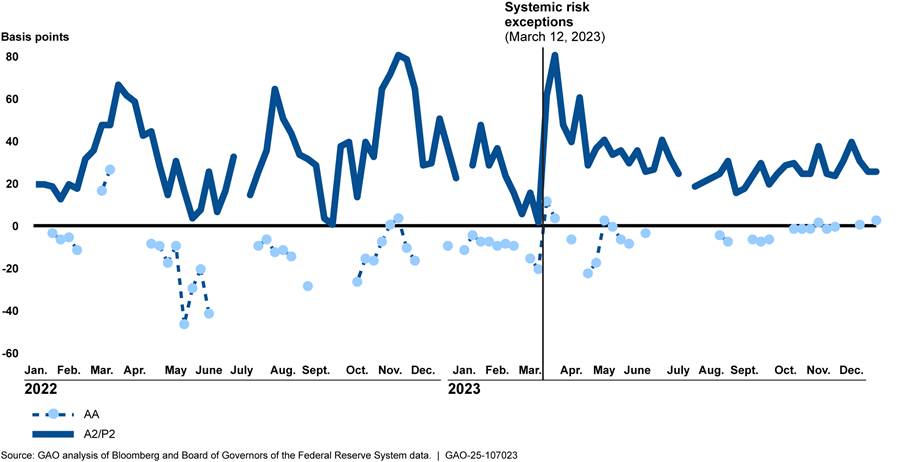

Broader Economy

Nonfinancial commercial paper spreads jumped in the week after the bank failures, continued to rise the following week, and then largely stabilized. While the initial response was large, the spread narrowed relatively quickly (see fig. 10). This rapid stabilization suggests regulators’ actions could have helped prevent further increases in borrowing costs for nonfinancial businesses. In addition, this suggests that the March 2023 bank failures may not have had an unusually severe impact on liquidity constraints faced by nonfinancial corporations. However, whether access to credit would have worsened in the absence of regulators’ actions remains unclear.[40]

Notes: The figure is for weekly average of the daily rates because the rates were not reported for some days in some weeks. A rating of AA is for issuers with at least one “1” or “1+” rating, but no other ratings than “1”, according to the rating agencies Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s. An A2/P2 rating is for issuers with at least one “2” rating, but no ratings other than “2.” A line is broken if there are no data for the category on that date. A basis point is 1/100th of a percentage point. The spread is the difference between the commercial paper rate and the overnight indexed swap of the same maturity.

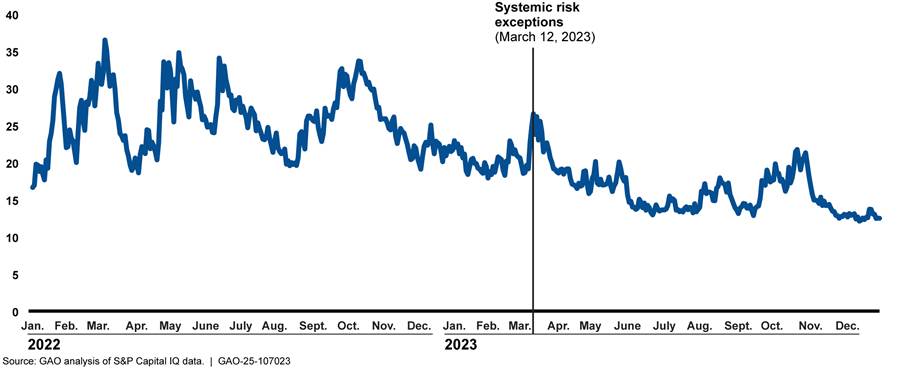

To assess broader effects on the economy, we analyzed the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index. Our analysis indicated a jump in expected volatility of the S&P 500 index beginning on March 9, 2023, which peaked on March 13 and subsequently declined (see fig. 11). This pattern suggests regulators’ actions could have helped mitigate additional volatility in the stock market. However, the jump in volatility at the time of the bank failures was smaller than several episodes of increased volatility in 2022. This suggests that the bank failures may not have had an outsized impact on expected volatility in the stock market. Nevertheless, whether there would have been higher volatility in the absence of regulators’ actions remains unclear.

Notes: The index estimates 30-day expected volatility of the S&P 500 Index by aggregating weighted market prices of S&P 500 options.

Proposed Changes May Help to Address Risks Associated with Use of the Systemic Risk Exception

Experts Suggest the Systemic Risk Exception Could Exacerbate Moral Hazard and Weaken Market Discipline

We conducted a literature review and interviewed four academics about the likely effects of invoking the systemic risk exception. These sources generally agreed that while covering all deposits by invoking the exception may mitigate immediate adverse and systemic effects, it can also have unintended consequences.

Specifically, the systemic risk exception can increase moral hazard and the risk of bank failures.[41] By providing explicit deposit guarantees and implicit guarantees, such as backing uninsured deposits, FDIC may create incentives for banks to engage in riskier behavior, such as investing in riskier assets or increasing risky lending, according to literature and academics.

Furthermore, the systemic risk exception may reduce depositor monitoring of their bank’s activities, encouraging banks to take on excessive risk, according to literature.[42] This is because deposit insurance expansion may cause depositors to be less careful in selecting and monitoring their banks. If depositors feel less afraid of losing their deposits, they may also be less likely to withdraw their funds from risk-taking banks weakening the relationship between risk and bank funding.

Proposed Changes Might Address Risks Posed by Use of Systemic Risk Exception

In the aftermath of the 2023 bank failures, some regulators and lawmakers proposed changes to the financial regulatory framework and legislation to help limit excessive risk-taking by large banks and depositors. These changes include deposit insurance reforms, enhanced capital requirements for large banks, long-term debt requirements, and executive compensation legislation. Additionally, reforms to improve resolution plans seek to help mitigate the need for future systemic risk exceptions and reduce moral hazard.

Deposit Insurance Reform

FDIC issued a report on May 1, 2023, evaluating proposed options for reforming the deposit insurance system. The report identified targeted coverage as the most promising option.[43] Targeted coverage allows for different levels of deposit insurance coverage across different account types, with a focus on higher coverage for business payment accounts. This approach may help alleviate corporate disruptions by bringing financial stability benefits with fewer moral hazard costs.[44]

However, the report stated that extending deposit insurance to business payment accounts also poses challenges. It can be difficult to distinguish which accounts merit higher coverage and prevent depositors and banks from circumventing those distinctions. Also, extending higher deposit insurance to business payment accounts may require a significant increase in assessments to support the Deposit Insurance Fund.

Enhanced Capital Requirements for Large Bank Organizations

In July 2023, OCC, FDIC, and the Federal Reserve jointly issued a proposed rule to revise capital requirements for banks with $100 billion or more in assets.[45] According to the Federal Reserve Vice Chair for Supervision, the proposal aims to align bank capital requirements with risk, making banks responsible for their own risk-taking, among other things. It would implement recommendations previously proposed by the Vice Chair, addressing issues that arose from the 2023 bank failures and implementing proposed bank capital rules known as the Basel III Endgame.[46] The proposal would require banks with over $100 billion in assets to include unrealized gains and losses on certain securities in their capital levels, among other things.[47] This proposal is designed to improve the transparency into banks’ risk-taking and financial conditions. However, some officials from regulatory agencies and industry representatives see the proposal as inadequate for addressing some causes of the 2023 bank failures, while also imposing unnecessary burden and costs for banks.

Long-Term Debt Requirements

In August 2023, FDIC, Federal Reserve, and OCC proposed a rule requiring certain insured depository institutions with at least $100 billion in assets to maintain a minimum amount of long-term debt.[48] According to the FDIC Chairman, this requirement would mitigate challenges encountered when large regional banks fail and would promote financial stability. This is because long-term debt can absorb losses in the event of bank failure, providing flexibility for FDIC to resolve the bank. Additionally, long-term debt investors are incentivized to monitor their bank’s risk, as they cannot quickly withdraw their money.[49] However, the proposed rule could increase bank funding costs and place smaller banks at a competitive disadvantage relative to the largest banks, according to a regulatory official, industry representatives, and market participants.[50] Further, banks with less than $100 billion in assets and high levels of uninsured deposits could still pose a threat to contagion and market stability, according to the director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.[51]

Executive Compensation Legislation

In June 2023, the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs advanced S. 2190, the Recovering Executive Compensation Obtained from Unaccountable Practices Act of 2023, to the full Senate.[52] The bill is designed to boost executive accountability following the 2023 bank failures. For example, it would authorize regulators to remove or prohibit senior bank executives who managed risks and governance inappropriately. It would also require banks to adopt forward-looking corporate governance and accountability standards. Additionally, it would authorize FDIC to recover certain compensation—such as profits from selling bank stock—from senior executives responsible for the failure of certain banks. However, some academics believe that executive compensation reform could be difficult to implement, for example, because executive compensation and employment contracts could be hard to break.

Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act directed federal financial regulators, including FDIC and the Federal Reserve, to jointly issue regulations or guidelines relating to incentive-based compensation at certain financial institutions by April 21, 2011.[53] The act requires that the regulations or guidelines prohibit incentive-based payment arrangements that could encourage inappropriate risks, such as excessive compensation. As of September 2024, the regulators have not issued a final rule to implement Section 956.[54]

Reforms on Resolution Plans for Large Bank Organizations

In August 2023, FDIC proposed a rule to revise its regulatory requirement that insured depository institutions with $50 billion or more in total assets submit resolution planning information.[55] The proposed rule aimed to enhance FDIC’s resolution readiness in cases of material distress or failure of these large institutions. In doing so, it sought to incorporate lessons learned from the 2023 bank failures. However, some market participants and industry representatives expressed concerns that some of the requirements, such as the frequency of resolution plan submissions and bank asset valuation exercises, may be impractical and burdensome. An FDIC Board Member also questioned FDIC’s statutory authority to prescribe and enforce certain requirements in the proposal.[56]

The final rule was approved by the FDIC board in June 2024 and went into effect in October 2024.[57] It requires insured depository institutions with $100 billion or more in assets to submit resolution plans that facilitate a least-cost resolution and address potential adverse effects on U.S. economic stability. Institutions with at least $50 billion but less than $100 billion in total assets must submit informational filings. The rule also enhances FDIC’s assessment of resolution submissions and provides for testing of an institution’s key capabilities, such as continuation of critical services needed in a bank’s resolution.

In August 2024, FDIC and the Federal Reserve finalized guidance to assist certain large banking organizations with submitting resolution plans required under Section 165 (d) of the Dodd-Frank Act and related regulations.[58] According to the guidance, plans that contemplate FDIC’s resolution of a failed bank should not assume the use of the systemic risk exception.[59] Rather, such plans should explain how FDIC can resolve the bank consistent with statutory least-cost requirements.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and Treasury for review and comment. FDIC, Federal Reserve, and Treasury provided technical comments that we incorporated as appropriate. The agencies did not provide formal comments.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Secretary of the Treasury, and interested parties. In addition, this report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff members have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-8678 or clementsm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Office of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributors to this report are listed in appendix III.

Michael E. Clements

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

The systemic risk exception in the Federal Deposit Insurance Act (as amended, the FDI Act) exempts the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) from certain statutory cost limitations when FDIC winds up the affairs of an insured depository institution for which FDIC has been appointed receiver.[60] In this report, we examine (1) steps taken by FDIC, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve), and the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) related to invoking the systemic risk exception for Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank; (2) the likely effects of invoking the exception for these two banks; and (3) the potential unintended consequences of the systemic risk exception on the incentives and conduct of insured depository institutions and uninsured depositors and proposals that may help mitigate such effects.[61]

Document Reviews

To identify steps taken by FDIC, the Federal Reserve and Treasury related to the systemic risk exception, we reviewed the FDIC and Federal Reserve recommendations, the Secretary of the Treasury’s determinations, and other agency documentation. We reviewed FDIC and Federal Reserve documentation related to the analyses conducted by staff to support the recommendations to invoke the systemic risk exception. These documents included agency workpapers related to their monitoring of supervised banks in key areas, such as deposit outflows, depositor, and funding composition. We also reviewed documentation on Treasury staff analysis of FDIC and Federal Reserve recommendations, criteria set forth in the FDI Act and other sources of information, such as Call Report data.

We also reviewed and analyzed documentation on coordination and communication that occurred among Treasury, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, other federal stakeholders, and external parties from March 9, 2023, to March 12, 2023. These documents included meeting appointments and email correspondence related to agencies’ efforts to monitor and assess financial markets and the broader economy.

To describe the actions taken pursuant to the systemic risk exception, we reviewed and analyzed documentation related to FDIC’s transfer of uninsured deposits at the failed banks. This included reviewing documents related to the bridge bank agreements, purchase and assumption agreements as well as reviewing public sources.

Data Analyses

We reviewed selected indicators to assess how economic and financial conditions performed before and after the 2023 bank failures and subsequent actions taken by regulators. To identify potential indicators, we reviewed prior GAO work; reports and data from the Federal Reserve, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago; and data from private organizations, including S&P Capital IQ and Bloomberg. We analyzed trends in these indicators, as described below, before and after the March 2023 bank failures and subsequent regulator actions.

The indicators we selected included market confidence and credit risk of regional banks. To measure this, we used the stock market performance of a regional banking exchange-traded fund and credit default swap spreads for a group of peer banks, using data from S&P Capital IQ. To assess the effect on deposit outflows and liquidity pressure, we analyzed deposit levels and borrowings of commercial banks, using data from the Federal Reserve. We assessed financial and corporate credit market conditions using the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s National Financial Conditions Index and credit spreads, with data from the Bloomberg Terminal. To gauge the broader effects on the economy, we examined the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility S&P 500 Index, using data from S&P Capital IQ.

Our analysis covered the period from January 2022 through December 2023. We chose 2022 as the starting point to establish a baseline for comparison with the variations observed in March 2023. We used December 2023 as the end point to capture a potentially longer recovery period for some indicators. We focused on frequently reported data (i.e., daily or weekly) to capture the immediate impact of regulators’ actions within days or weeks.

To assess the reliability of these data sources and indicators, we reviewed relevant documentation on data collection methodology, interviewed Federal Reserve and Federal Reserve Bank of New York staff, and reviewed prior GAO work. We found these indicators to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of serving as indicators for banking and other economic conditions.

To describe the likely effects of FDIC’s actions protecting all uninsured deposits for SVB and Signature Bank, we collected and analyzed data related to the financial and economic conditions at the time the systemic risk determinations were made and the actions taken pursuant to the systemic risk exception.

Literature Review and Expert Interviews

To identify the likely effects more generally of invoking the systemic risk exception, we conducted a literature search for studies that addressed (1) the likely effects of systemic risk exception (protecting uninsured depositors) on incentives for banks and depositors; (2) mitigations to changes in incentives on behavior of banks and depositors due to increased deposit insurance coverage; or (3) options for mitigating systemic risk in general. To do so, we searched the following databases: EBSCO, ProQuest, Harvard Kennedy School Think Tank, SCOPUS, Policy File Index, and Google Scholar.

We identified 18 studies on these topics published between 2013 and 2023. We reviewed the methodologies of these studies to ensure that they were sound and determined that they were sufficiently reliable for describing the three areas of focus noted above.

We also interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of four academics:

· Alan S. Blinder, Gordon S. Rentschler Memorial Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Princeton University

· Richard Carnell, Associate Professor Law, Fordham University School of Law.

· Thomas Hoeing, Distinguished Senior Fellow Mercatus Center, George Mason University

· Simon Johnson, Ronald A. Kurtz (1954) Professor of Entrepreneurship and head of the Global Economics and Management Group, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

These individuals were chosen for their expertise in financial stability and moral hazard, and their diverse backgrounds in business, public policy, finance, economics, and law.

We also reviewed recent regulatory reforms proposed by financial regulators and academics, along with legislation introduced in Congress as a result of the 2023 bank failures. We selected aspects of proposals and legislation that could potentially help to mitigate moral hazard.

We also reviewed public comments that regulators, industry stakeholders, and market observers made during the public comment period for the proposed regulatory reforms.

For all objectives, we reviewed relevant laws, rules, and regulations. We also interviewed FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and Treasury officials about steps taken to invoke the systemic risk exception, likely effects of invoking the systemic risk exception on SVB and Signature Bank, and potential unintended consequences of the systemic risk exception on incentives and conduct of insured depository institutions and uninsured depositors.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Acharya, Viral V., and Matthew P. Richardson, Kermit L. Schoenholtz, Bruce Tuckman, Richard Berner, Stephen G. Cecchetti, Sehwa Kim, Seil Kim, Thomas Philippon, Stephen G. Ryan, Alexi Savov, Philipp Schnabl, and Lawrence J. White. SVB and Beyond: The Banking Stress of 2023. White Paper, New York University Stern School of Business (2023).

Acharya, Viral V., and Hamid Mehran and Anjan V. Thakor. “Caught between Scylla and Charybdis? Regulating Bank Leverage When There Is Rent Seeking and Risk Shifting.” Review of Corporate Finance Studies, vol. 5, no. 1 (2016): 36–75.

Allen, Franklin, and Elena Carletti, Itay Goldstein, and Agnese Leonello. “Moral Hazard and Government Guarantees in the Banking Industry.” Journal of Financial Regulation, vol.1, no.1 (2015): 30–50.

Anginer, Deniz, and Asli Demirgüç-Kunt. Bank Runs and Moral Hazard: A Review of Deposit Insurance. Policy Research Working Paper No.8589, World Bank Group (2018).

Ben-David, Itzhak, and Ajay A. Palvia and René M. Stulz. How Important Is Moral Hazard for Distressed Banks? Finance Working Paper N° 681, European Corporate Governance Institute (2020).

Calomiris, Charles W. and Matthew Jaremski. “Deposit Insurance: Theories and Facts.” Annual Review of Financial Economics, vol. 8 (2016): 97–120.

Claassen, Rutger. “Financial Crisis and the Ethics of Moral Hazard.” Social Theory and Practice, vol. 41, no.3 (2015): 527–551.

Crawford, John. “The Moral Hazard Paradox of Financial Safety Nets.” Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, vol. 25, no.1 (2015): 95–140.

Danisewicz, Piotr, and Chun Hei Lee and Klaus Schaeck. “Private Deposit Insurance, Deposit Flows, Bank Lending, and Moral Hazard.” Journal of Financial Intermediation, vol. 52 (2022): 1–24.

Hogan, Thomas L., and Kristine Johnson. “Alternatives to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.” The Independent Review, vol. 20, no. 3 (2016): 433–454.

Hott, Christian. “Leverage and Risk Taking under Moral Hazard.” Journal of Financial Services Research, vol. 61 (2022):167–185.

Kress, Jeremy C., and Matthew C. Turk. “Too Many to Fail: Against Community Bank Deregulation.” Northwestern University Law Review, vol. 115, no. 3 (2020): 647–716.

Murray, Noel, and Ajay K. Manrai and Lalita Ajay Manrai. “The Financial Services Industry and Society: The Role of Incentives/Punishments, Moral Hazard, and Conflicts of Interests in the 2008 Financial Crisis.” Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, vol. 22, no. 43 (2017): 168–190.

Pernell, Kim, and Jiwook Jung. “Rethinking moral hazard: government protection and bank risk-taking.” Socio-Economic Review, vol. 22, no.2 (2024): 625–653.

Schwarcz, Steven L. “Too Big to Fool: Moral Hazard, Bailouts, and Corporate Responsibility.” Minnesota Law Review, vol. 102, no. 2 (2017): 761–802.

Sharma, Padma. “Government Assistance and Moral Hazard: Evidence from the Savings and Loan Crisis.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, vol.107, no.3 (2022): 37–53.

Strahan, Philip E. “Too Big to Fail: Causes, Consequences, and Policy Responses.” Annual Review of Financial Economics, vol. 5 (2013): 43–61.

Wall, Larry D. So Far, So Good: Government Insurance of Financial Sector Tail Risk. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Policy Hub, no. 2021-13 (2021).

GAO Contact

Michael E. Clements, 202-512-8678 or clementsm@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Karen Tremba (Assistant Director), Akiko Ohnuma (Analyst in Charge), Kyle Abe, Yiwen (Eva) Cheng, Wes Cooper, Rachel DeMarcus, Genesis Galo, Garett Hillyer, Jill Lacey, Kirsten Noethen, Jena Sinkfield, Asia Thomas made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]§ 13(c)(4)(G), 12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(G). The Federal Reserve System consists of the Board of Governors (a federal agency headed by seven board members and supported by staff) and 12 Federal Reserve Banks (one for each of 12 regional districts). We use “Federal Reserve” to refer to the Board of Governors generally and “Federal Reserve Board” to refer specifically to the agency’s seven-member board.

[2]The standard maximum deposit amount insured is $250,000.

[3]The FDI Act defines a receiver as an agent that has been charged by law with winding up the affairs of a bank or certain other institutions. § 3(j), 12 U.S.C. § 1813(j). The statutory cost limitations are referred to as the least-cost rule, which we discuss in more detail later in this report.

[4]In this report, we refer to these determinations as systemic risk determinations.

[5]§ 13(c)(4)(G)(iv), 12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(G)(iv).

[6]See GAO, Bank Regulation: Preliminary Review of Agency Actions Related to 2023 Bank Failures, GAO‑23‑106736 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 28, 2023).

[7]The Federal Reserve accomplishes this by influencing the monetary and credit conditions in the economy in pursuit of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.

[8]Pub. L. No. 102-242, 105 Stat. 2236 (codified in scattered sections of titles 5, 12 and 15 of the United States Code).

[9]Pub. L. No. 102-242, § 141(a)(1), 105 Stat. 2236, 2273-2276 (codified as amended at 12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)).

[10]12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(A). This provision also specifies that FDIC may act only to the extent necessary to meet its obligation to provide insurance coverage for the institution’s insured deposits. The Deposit Insurance Fund is funded by assessments levied on insured depository institutions and is used to cover deposits (such as checking and savings accounts) at such institutions, up to the insurance limit.

[11]12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(E).

[12]12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(B).

[14]12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(G)(i).

[15]See Pub. L. No. 111-203, tit. XI, § 1106(b)(1), 124 Stat. 1376, 2125 (codified as amended at 12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(G)(i)).

[16]12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(G)(ii). Assessments against depository institution holding companies must be made with the concurrence of the Secretary of the Treasury.

[17]12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(G)(iii), (v).

[18]12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(G)(iv).

[19]Federal Reserve, Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 2023).

[20]A bridge bank is a temporary bank chartered to carry on the business of a failed institution until a permanent solution can be implemented.

[21]Nonmember refers to banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System.

[23]Our analysis compared SVB and Signature Bank to a group of 19 banking institutions with reported deposit balances and that each had total assets between $100 and $250 billion at year-end 2022.

[24]See GAO, Financial Institutions: Causes and Consequences of Recent Bank Failures, GAO‑13‑71 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 3, 2013).

[26]See GAO‑23‑106736. These requirements include unusual and exigent circumstances; broad-based program eligibility; protection of taxpayers from losses; lack of adequate credit accommodations from other banking institutions; and exclusion of insolvent borrowers. 12 U.S.C. § 343(3).

[27]The Exchange Stabilization Fund was originally established in the 1930s to stabilize the exchange value of the dollar by buying and selling foreign currencies and gold. The Secretary of the Treasury has authority to use the stabilization fund to deal in gold, foreign exchange, and other instruments of credit and securities.

[28]Federal Reserve Banks extend discount window credit to U.S. banks, including U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks, under three programs. One of these programs is the primary credit program, which offers credit to generally sound banks without restrictions on the use of the funds.

[29]Credit spreads are financial market indicators that compare the yield of a financial security to the yield of a benchmark security, such as a Treasury security.

[30]A credit default swap is a type of credit derivative that allows the buyer of protection to transfer credit risk associated with default on debt issued by a corporate or sovereign entity, known as a reference entity.

[31]A call report is a quarterly report that collects financial data from financial institutions, including commercial banks, such as a bank’s liabilities, total deposits, and assets.

[32]According to a White House press release, the Secretary met with the President on the afternoon of March 12. The Secretary also met with the White House Chief of Staff and Director of the National Economic Council over the March 10 weekend to keep the President informed about market developments, according to documentation we reviewed.

[33]On March 26, FDIC announced that it entered into a purchase and assumption agreement for certain assets and liabilities of Silicon Valley Bridge Bank with First Citizens Bank & Trust Company. First Citizens agreed to assume an estimated $56 billion in deposits according to a First Citizens press release. On March 19, FDIC announced that it entered into a purchase and assumption agreement for certain assets and liabilities of Signature Bridge Bank with Flagstar Bank, National Association. According to New York Community Bancorp, its bank holding company, Flagstar agreed to assume an estimated $34 billion in deposits of the Signature Bridge Bank.

[34]See Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Annual Report 2023 (Feb. 22, 2024)