DOMESTIC TERRORISM

Additional Actions Needed to Implement an Effective National Strategy

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107030. For more information, contact Triana McNeil at mcneilt@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107030, a report to congressional requesters

Additional Actions Needed to Implement an Effective National Strategy

Why GAO Did This Study

In June 2021, the White House NSC released a Strategy that aims to provide a framework to address domestic terrorism, which it identified as an urgent priority. The FBI Director testified in December 2023 that domestic terrorism investigations had more than doubled since 2020.

GAO was asked to review the Strategy. This report examines, among other things, (1) steps agencies have taken to implement the Strategy, (2) the extent to which the Strategy includes desirable characteristics for an effective national strategy, and (3) challenges identified by federal and nonfederal partners in implementing the Strategy.

GAO reviewed the Strategy and related documents, analyzed NSC information, and interviewed officials from eight federal agencies. GAO also interviewed nonfederal partners and Joint Terrorism Task Force personnel in seven geographically dispersed states that had experience with domestic terrorism incidents, as well as 12 domestic terrorism experts.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that the NSC ensure any domestic terrorism strategy reflects all desirable characteristics and that DHS and DOJ inform nonfederal partners about roles to combat domestic terrorism. In response to comments, GAO modified the recommendations to apply them to any national domestic terrorism strategy as well as DOJ and DHS’s broader missions. NSC did not provide comment and DOJ concurred. DHS did not concur but will work with nonfederal partners to counter domestic terrorism.

What GAO Found

The 2021 National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism (Strategy) tasked the Departments of Homeland Security (DHS) and Justice (DOJ), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and other federal agencies to implement activities to counter domestic terrorism. Agencies have taken steps to implement most of these activities (49 of 58 activities identified by GAO) through both new and preexisting efforts. For example, agencies shared online resources for terrorism prevention with nonfederal partners and the public and updated screening procedures for federal and military personnel. The Strategy also states that nonfederal partners, such as state and local entities, play a role in countering domestic terrorism.

The Strategy, however, does not fully address most of the six desirable characteristics that GAO has previously reported comprise an effective national strategy. For example, the Strategy does not include a risk assessment or clarify which federal entity is responsible for oversight. Further, it does not consistently include milestones, performance measures, or resource information. By including such information in the Strategy, or any national strategy, in effect, to combat domestic terrorism, the National Security Council (NSC) could improve how it oversees activities. In turn, this could enable the NSC and relevant agencies to measure progress in meeting goals to successfully address domestic terrorism and enhance public safety.

Federal and nonfederal partners identified challenges related to the Strategy, such as not knowing which agencies were responsible for specific activities. DHS and DOJ, two agencies with statutory missions to combat domestic terrorism and tasked with the most Strategy activities, have shared some details about Strategy implementation, such as providing domestic terrorism-related information on publicly accessible websites. However, they could further clarify their roles and efforts to counter domestic terrorism and communicate such to nonfederal partners to ensure their contributions effectively assist federal efforts. In doing so, DHS and DOJ would be better equipped to address their missions related to countering domestic terrorism. Also, nonfederal partners could better align their resources to support federal efforts.

Abbreviations

CP3 Center

for Prevention Programs and

Partnerships

DHS Department of Homeland Security

DOD Department of Defense

DOJ Department of Justice

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

I&A Office of Intelligence and Analysis

JTTF Joint Terrorism Task Force

NCTC National Counterterrorism Center

NSC National Security Council

ODNI Office of the Director of National Intelligence

S&T Science and Technology Directorate

2021 Strategy 2021

National Strategy for Countering

Domestic Terrorism

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 9, 2025

The Honorable Bennie G.Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Seth Magaziner

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Counterterrorism, Law Enforcement, and Intelligence

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Daniel Goldman

House of Representatives

In June 2021, the White House National Security Council (NSC) released the nation’s first National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism (2021 Strategy) and identified domestic terrorism as the most urgent terrorism threat facing the United States.[1] In addition, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) testified in December 2023 that the number of domestic terrorism investigations had more than doubled since 2020.[2] The threat posed by domestic violent extremism has risen in recent years, as evidenced by attacks in a number of U.S. cities.[3] For example, in May 2022, a racially motivated individual shot and killed 10 individuals in Buffalo, New York.[4] In October 2024, DHS reported that the likelihood of violence from domestic violent extremists due to ongoing current events, such as the Israel-Hamas conflict, was of particular concern.[5]

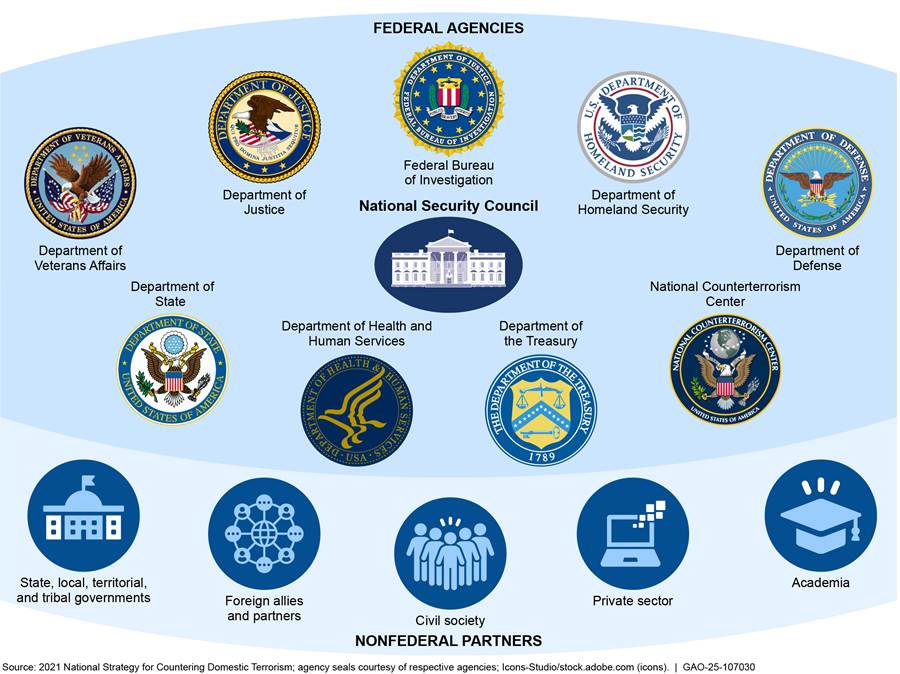

The 2021 Strategy aims to provide a national framework for the U.S. government and its nonfederal partners to specifically address domestic terrorism. The FBI, within the Department of Justice (DOJ), and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) are the main federal entities charged with preventing terrorist attacks in the United States, including attacks conducted by domestic violent extremists.[6] The 2021 Strategy provides that multiple agencies, including DOJ; DHS; the Departments of Defense (DOD), Health and Human Services, State, Treasury, Veterans Affairs, and the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), as well as nonfederal partners such as states and local entities, play a role in countering domestic terrorism.

We have previously reported on federal strategies and initiatives aimed at preventing domestic violent extremist attacks and promoting actions that could reduce the likelihood that attacks are planned in the first place. For example, we recommended in April 2017 that DOJ and DHS develop a cohesive strategy to assess overall efforts for countering violent extremism.[7] In July 2021, we evaluated a 2019 DHS strategy to address targeted violence and terrorist prevention and found that it did not fully include all elements of a comprehensive strategy.[8] Further, we previously reported on federal agency efforts to collaborate and share domestic terrorism information with relevant partners. In February 2023, we found that while DHS and the FBI collaborate to identify and counter domestic terrorism threats, they do not consistently assess the overall effectiveness of these collaborative efforts. We recommended that they implement a process to do so.[9] We also found that DHS and the FBI had not assessed the extent to which formal agreements fully reflect their charge to jointly prevent domestic terrorism attacks. We recommended that DHS and the FBI assess existing agreements and that they update and revise these agreements accordingly. These are priority recommendations that have not been fully implemented as of February 2025.[10]

In September 2023, we found that the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, an office within the Department of the Treasury, was not included in the development of a booklet designed to help law enforcement and the general public identify behavioral indicators associated with domestic violent extremists.[11] We recommended that the NCTC, in consultation with the FBI and DHS, ensure that its process for updating the booklet clarifies that Treasury can and should seek input from the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network when developing future updates.[12]

You asked us to review the development and implementation of the 2021 Strategy. This report examines (1) how the 2021 Strategy aligns with recent domestic terrorism threat assessments, (2) the steps federal agencies have taken to implement the 2021 Strategy, (3) how federal agencies are engaging with federal and nonfederal partners to implement the 2021 Strategy and identify U.S. and international lessons learned, (4) the extent to which the 2021 Strategy includes desirable characteristics for an effective national strategy, and (5) challenges in implementing the 2021 Strategy identified by federal and nonfederal partners.

To determine how the 2021 Strategy aligns with recent domestic terrorism threat assessments, we compared domestic terrorism threats identified in the 2021 Strategy against the threats identified in seven threat assessments publicly issued by DHS, the FBI, the NCTC, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) since 2021.[13]

To describe the steps that federal agencies have taken to implement the 2021 Strategy, we reviewed the 2021 Strategy and related documents and identified 58 statements that direct either a federal agency by name, or the federal government in general, to implement a specific activity.[14] We then requested that DHS; DOJ; DOD; the Departments of Health and Human Services, State, Treasury, Veterans Affairs, and the NCTC identify what steps, if any, they have taken to support implementation of 2021 Strategy activities and whether these steps represent new or preexisting efforts that predate the 2021 Strategy.[15]

To describe how federal agencies are engaging with federal and nonfederal partners to implement the 2021 Strategy and identify U.S. and international lessons learned, we interviewed officials from each of the agencies in our review, selected subject matter experts, state and local officials, and foreign government officials. Specifically, we selected 12 subject matter experts familiar with domestic terrorism prevention and other efforts. We conducted semistructured interviews with state and local officials from seven state-run primary fusion centers.[16] These centers serve as a focal point for intelligence gathering, analysis, and sharing of threat information among federal, state, and local partners, including information related to domestic terrorism threats. We also met with federal officials from the DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) assigned to support the fusion centers and officials from the FBI Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTF) in each of the seven selected locations.[17] We further interviewed government officials from Germany and the United Kingdom who are responsible for leading government efforts to counter domestic terrorism.[18]

To evaluate the extent to which the 2021 Strategy includes desirable characteristics for an effective national strategy, we evaluated public documents related to the 2021 Strategy against characteristics described in our prior work.[19] We assessed each of the desirable characteristics as fully addressed, partially addressed, or not addressed.[20] As discussed above, we also interviewed federal officials at relevant departments and subject matter experts on federal efforts to develop, implement, and oversee the 2021 Strategy.

To describe what challenges federal and nonfederal partners identified in implementing the 2021 Strategy, we reviewed documents and interviewed federal and nonfederal partners, as discussed above. We compared DOJ’s and DHS’s efforts to engage with nonfederal partners to implement the 2021 Strategy with the 2021 Strategy and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[21] Appendix I provides additional details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Definition of Domestic Terrorism and Threat Categories

In the 2021 Strategy, the definition of domestic terrorism is an activity that occurs primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States, involves acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any state, and appears to be intended to

· intimidate or coerce a civilian population;

· influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or

· affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping.[22]

The 2021 Strategy uses the terms domestic terrorism and domestic violent extremism interchangeably, as do the FBI and DHS.[23] These entities use the term domestic violent extremism to refer to a variety of domestic terrorism threats. According to the FBI and DHS, the word “violent” is important because mere advocacy or activism for political or social positions or use of strong rhetoric does not constitute violent extremism and may be constitutionally protected.[24]

Following an initial report in 2021, the FBI and DHS are required to annually update and report domestic terrorism threat-related information to Congress.[25] In their first report in response to this requirement, the FBI and DHS jointly identified five domestic terrorism threat group categories the U.S. government uses, as shown in figure 1.[26] These categories are also reflected in the 2021 Strategy and include violent extremism motivated by (1) race or ethnicity, (2) antigovernment or antiauthority sentiment, (3) animal rights or environmental sentiment, (4) abortion-related issues, and (5) other domestic terrorism threats not otherwise defined or primarily motivated by the other categories. The report noted that domestic violent extremists can fit within one or multiple categories of ideological motivation and can span a broad range of groups or movements. According to the report, these categories help the agencies better understand threats associated with domestic violent extremism.[27]

Figure 1: Summary of Federal Bureau of Investigation and Department of Homeland Security Domestic Terrorism Threat Categories

Domestic Terrorism and Domestic Violent Extremism in the United States

According to agency data and our prior work, domestic terrorism has increased in recent years. For example, during fiscal years 2020 through 2022, the FBI and DHS I&A identified 74 significant domestic terrorism incidents in the United States, including high-profile attacks, plots, threats of violence, arrests, and disruptions.[28] In addition, in October 2024, DHS I&A reported that from September 2023 through July 2024, domestic violent extremists who were specifically driven by antigovernment, racial, or gender-related motivations conducted at least four attacks in the United States, and law enforcement disrupted at least seven additional plots.[29] Beyond domestic terrorism incidents, we reported in February 2023 that the number of open FBI domestic terrorism cases grew 357 percent (1,981 to 9,049) from fiscal years 2013 through 2021.[30]

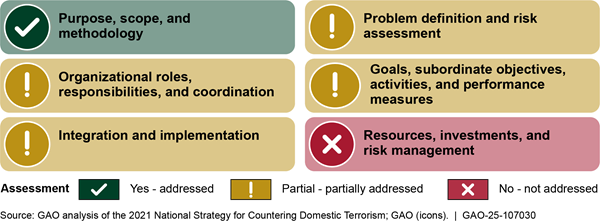

Federal Strategies Related to Domestic Terrorism Since 2011

Since 2011, the White House and DHS have developed national and departmental strategies designed to counter violent extremism and domestic terrorism in the United States. The White House developed a national strategy for countering violent extremism in 2011, and also developed additional national security-related strategies in 2011 and 2018 that included references to countering violent extremism. At the department level, DHS developed a strategy for countering violent extremism in 2016 and replaced it in 2019 with a strategy for preventing targeted violence and terrorism. According to DHS, it broadened the terrorism prevention concept to include targeted violence in 2019 to recognize and address a broader range of current and emerging threats among communities. Figure 2 provides an overview of the White House and DHS strategies related to domestic terrorism since 2011.

Figure 2: White House and Department of Homeland Security Strategies Related to Domestic Terrorism Since 2011

aThe five categories of domestic terrorism threats, as defined by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Department of Homeland Security are (1) race or ethnicity, (2) antigovernment or antiauthority sentiment, (3) animal rights or environmental sentiment, (4) abortion-related issues, and (5) other domestic terrorism threats not otherwise defined or primarily motivated by the other categories. The Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Department of Homeland Security, Strategic Intelligence Assessment and Data on Domestic Terrorism (June 2023).

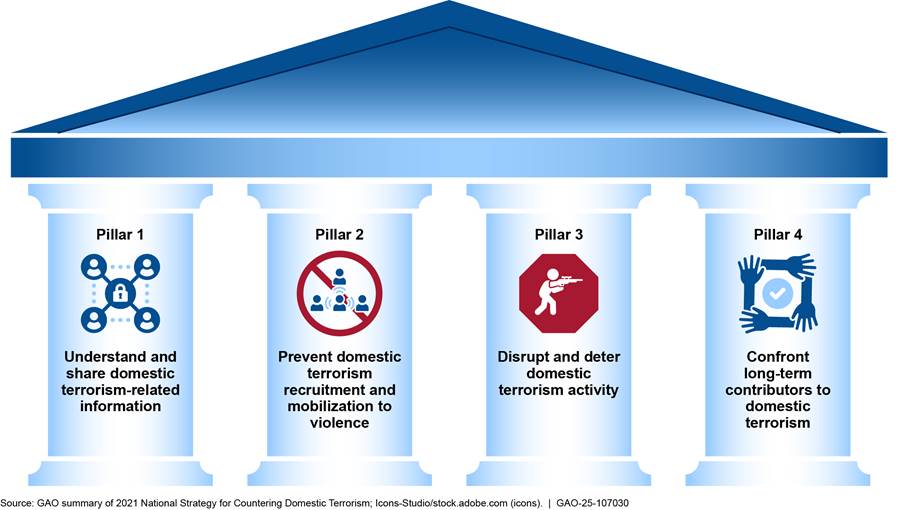

The White House issued the 2021 Strategy in June 2021. The 2021 Strategy aims to provide an overarching approach for the U.S. government and its nonfederal partners to specifically address domestic terrorism through the implementation of four main goals, or pillars, as shown in figure 3. Additionally, the 2021 Strategy identifies subordinate goals that further define the types of efforts that support achieving each of the main goals or pillars. For example, Pillar 1 seeks to understand and share domestic terrorism-related information and has a subordinate goal of enhancing domestic terrorism-related research and analysis.

Since the issuance of the 2021 Strategy, the White House released two Fact Sheets, in June 2021 and June 2023. These Fact Sheets list examples of some activities that agencies have taken to implement the 2021 Strategy by strategic pillar and serve as updates for the 2021 Strategy.[31]

Key Roles and Responsibilities

The NSC authored the 2021 Strategy and coordinates its implementation through the NSC’s interagency process. The FBI–within DOJ–and DHS are the main federal entities charged with preventing terrorist attacks in the United States, including attacks conducted by domestic violent extremists.[32] The 2021 Strategy further states that multiple federal agencies play a role in countering domestic terrorism.

NSC. The White House leverages the NSC as its principal forum for national security and foreign policy decision-making with senior national security advisors and cabinet officials, according to the NSC.[33] In addition, as noted above, the NSC led the development of the 2021 Strategy and coordinates implementation of the 2021 Strategy. It also coordinates other national security policies across federal agencies through the interagency process.

DOJ. The FBI is responsible for leading law enforcement and domestic intelligence efforts to prevent and disrupt terrorist attacks.[34] Within FBI headquarters, the Counterterrorism Division manages the FBI’s Domestic Terrorism Program. The FBI-led JTTFs are specialized investigative units within the FBI field offices composed of task force officers from federal, state, and local law enforcement that collect and share information and intelligence.

Other DOJ components contribute to DOJ’s efforts to counter domestic terrorism threats through prosecutions, intelligence information sharing, and research, among others. For example, the National Security Division operates the Domestic Terrorism Unit within the Counterterrorism Section by coordinating domestic terrorism cases and supporting DOJ’s work to implement the 2021 Strategy. Additionally, the Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys supports 93 U.S. Attorneys who are responsible for prosecuting federal crimes, including those related to domestic terrorism.[35]

DHS. DHS I&A is the primary component within DHS responsible for accessing, receiving, analyzing, integrating, and disseminating intelligence and other information related to domestic terrorism.[36] Other entities within DHS support domestic terrorism-related activities by providing policy guidance, training, and oversight, among other items. For example, the DHS Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism leads the effort to coordinate counterterrorism activities across the department and with federal and external partners. The DHS Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans develops relevant policy guidance, strategies, and operational plans. In addition, the DHS Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships (CP3) provides grant funding and training for local governments, the private sector, and local communities to support activities aimed at preventing violent extremism and domestic terrorism, including the development of related state strategies. DHS I&A also assigns personnel to partner with state-led fusion centers across the country. Further, DHS Science and Technology Directorate supports research and development activities, including those related to domestic terrorism, with domestic and international partners.

The 2021 Strategy identifies other federal entities, such as DOD, the Departments of Health and Human Services, State, Treasury, and Veterans Affairs that also implement activities to counter domestic terrorism. For example, the State Department and Treasury work with foreign allies and federal government partners to assess if additional foreign entities linked to domestic terrorism can be designated as Foreign Terrorist Organizations or Specially Designated Global Terrorists.[37]

Within the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the NCTC leads and integrates the national counterterrorism effort across the intelligence community. The NCTC is the primary organization responsible for analyzing and integrating all U.S. government intelligence related to terrorism and counterterrorism, except for intelligence that pertains exclusively to domestic terrorism.[38] Although the NCTC’s activities are focused primarily on international counterterrorism, the NCTC is authorized to receive domestic counterterrorism intelligence from other sources, such as DHS I&A, that have a statutory duty to support the NCTC’s mission.[39]

Given the nature of the domestic terrorist threat, the 2021 Strategy states that the federal government should extend its partnerships across the federal government and to nonfederal partners, such as state, local, tribal, and territorial governments, as well as foreign allies and partners, civil society, the private sector, academia, and more. Figure 4 provides an overview of federal and nonfederal partners involved in implementing the 2021 Strategy.

Figure 4: Federal Entities and Nonfederal Partners Identified in the 2021 National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism

Domestic Terrorism Threats in the 2021 Strategy Are Consistent with Recent Threat Assessments

Categories of Domestic Terrorism Threats in Federal Threat Assessments Are Generally Consistent with the 2021 Strategy

We reviewed seven DHS, FBI, NCTC, and ODNI public threat assessments issued since the 2021 Strategy was released and found that the focus of the 2021 Strategy continues to be generally consistent with the threat categories identified in these assessments.[40] Specifically, the threat assessments we reviewed highlight aspects of the five primary domestic terrorism threat categories reflected in the 2021 Strategy.[41] Further, both the 2021 Strategy and most of the threat assessments issued since 2021 reported that the domestic terrorism threat will continue to persist or rise in the future.

Most of the assessments identify racially or ethnically motivated violent extremism as one of the most lethal domestic terrorism threats to the United States. For example, a June 2022 DHS, FBI, and NCTC joint threat assessment noted that since 2010, racially or ethnically motivated individuals have been responsible for the majority of domestic violent extremism-related deaths and pose a significant threat of lethal violence against civilians, particularly of racial, ethnic, and religious minorities.[42] Further, we found that all of these threat assessments, as well as the 2021 Strategy, mention antigovernment or antiauthority threats, such as those from militia violent extremists. For example, a 2023 DHS and FBI joint threat assessment stated that grievances of militia violent extremists are more disjointed than in previous years and that these actors will most likely continue to target specific groups, including government officials, government facilities, and law enforcement personnel.[43] Table 1 provides an overview of the threat categories included in each document.

Table 1: Domestic Terrorism Threat Categories Identified in Selected Threat Assessments Issued from 2021 through 2024

|

Threat assessment |

Source |

Domestic terrorism threat categoriesa |

||||

|

Racially and ethnically motivated violent extremism |

Antigovernment or antiauthority violent extremism |

Abortion-related violent extremism |

Animal rights and environmental violent extremism |

Other domestic terrorism threats |

||

|

2021 National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism |

NSC |

✓* |

✓* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

March 2021 Assessment of the Domestic Violent Extremism Threat |

ODNI, DHS, FBI and NCTC |

✓* |

✓* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

May 2021 Strategic Intelligence Assessment and Data on Domestic Terrorism |

FBI and DHS |

✓* |

✓* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

June 2022 Wide-Ranging Domestic Violent Extremist Threat to Persist |

DHS, FBI, and NCTCb |

✓* |

✓* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

October 2022 Strategic Intelligence Assessment and Data on Domestic Terrorism |

FBI and DHS |

✓* |

✓* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

June 2023 Strategic Intelligence Assessment and Data on Domestic Terrorism |

FBI and DHS |

✓* |

✓* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

September 2023: 2024 Homeland Threat Assessment |

DHS |

✓ |

✓ |

_ |

_ |

✓ |

|

October 2024: 2025 Homeland Threat Assessment |

DHS |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

_ |

✓ |

Legend:

✓ = Document includes threat category

✓* = Specific threat category is identified to either be the most lethal of the categories listed or that the specific threat remains elevated during the reporting period.

— = Specific threat category is not identified in the assessment.

Source: GAO analysis of documentation from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), the National Security Council (NSC), and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI). | GAO‑25‑107030

Note: GAO selected and reviewed a total of seven publicly available threat assessments issued from 2021 through 2024 by the following federal entities: DHS, the FBI, the NCTC, and ODNI. The table shows the different categories—as defined by the FBI and DHS—included in each assessment. While the DHS assessments do not refer to the threat categories by name, we reviewed those reports to identify whether they included any reference to the overall threat type. We found that the assessments highlight some categories as the more lethal threats.

aThe five categories of domestic terrorism threats identified in the chart are defined by the FBI and DHS in the May 2021 Strategic Intelligence Assessment and Data on Domestic Terrorism.

bNCTC officials stated that, consistent with congressional direction, as of December 2022, the NCTC has limited its work to focus on the transnational and international dimensions of the terrorist threats against the United States and did not produce any domestic terrorism-related assessments thereafter.

One assessment includes an additional subcategory within the antigovernment or antiauthority violent extremism threat category. This category is known as the antigovernment or antiauthority-other category. This category reflects threats from individuals who threatened government or law enforcement officials to whom they were ideologically opposed but who do not fit into the existing antigovernment or antiauthority violent extremism threat subcategories of militia, anarchist, and sovereign citizen extremists.[44] According to a 2023 DHS and FBI joint threat assessment, the threat originating from the antigovernment or antiauthority-other subcategory has increased in the last few years, and a rise in the future will likely be in response to high-profile events, such as elections or campaigns.[45]

In addition, we reviewed annual threat assessments that ODNI issued from 2021 through 2024.[46] Most of these assessments focus on worldwide threats to the United States, such as those coming from global terrorism, organized crime, or foreign governments, among others, and do not specifically focus on domestic terrorism. However, ODNI’s 2021 and 2022 assessments point to the rise of transnational influences on domestic violent extremists based in the United States. For example, the 2021 assessment states that domestic violent extremists are also inspired by like-minded individuals and groups abroad. The 2022 assessment states that individuals and small groups inspired by a variety of ideologies or personal motivations, such as racially or ethnically motivated violent extremism and militia violent extremism, probably present the greatest terrorist threat to the United States.[47]

In addition to reviewing recent assessments, we interviewed officials from seven selected JTTFs and fusion centers.[48] JTTF officials we interviewed noted that the domestic terrorism threat has generally increased since 2021. Most of these officials (five of seven) said that they noticed a specific increase among racially and ethnically motivated violent extremists. For example, JTTF officials from Michigan said they have seen an increase in racially or ethnically motivated violent extremism threats within the United States from individuals responding to the Israel-Hamas conflict and expect that this increased threat will continue. Officials from all seven of the fusion centers told us that they observed changes in the domestic terrorism threat landscape since 2021, including an increase in domestic terrorism threats in general. In particular, they reported an increase in racially and ethnically motivated and antigovernment threats.

Characteristics of Domestic Terrorists in Federal Threat Assessments Are Generally Consistent with the 2021 Strategy

We found that the characteristics of domestic terrorists outlined in the 2021 Strategy are similar to those that DHS, the FBI, the NCTC, and ODNI identified in subsequent public threat assessments from 2021 through 2024. Both the 2021 Strategy and recent assessments note that domestic terrorists are more likely to use technology to advance their beliefs; operate alone or within small groups; and be influenced by a range of factors, such as blended ideologies.[49]

Use of technology. Most of the threat assessments we reviewed, as well as the 2021 Strategy, indicate that domestic terrorists increasingly rely on online platforms, such as gaming and social media platforms, to radicalize and mobilize their views.[50] For instance, a 2023 ODNI assessment notes that racially or ethnically motivated violent extremists use a social media platform (Telegram) to share propaganda and exchange operational guidance.[51] Similarly, the 2021 Strategy notes that domestic terrorists use internet-based communications, such as social media, file-upload sites, and end-to-end encrypted platforms, which can amplify threats to public safety.

Lone offenders. Most of the threat assessments we reviewed, as well as the 2021 Strategy, point to the increase in the number of domestic terrorism-related lone offender attackers, as opposed to structured or organized groups. Specifically, the 2021 Strategy indicates that lone offenders or small groups adhering to a variety of ideologies are more likely to carry out attacks than organizations that advocate one ideology in particular. The 2021 Strategy states that lone offender efforts pose significant challenges for law enforcement to detect or disrupt.

Blended ideologies. The threat assessments we reviewed state that domestic violent extremists are often motivated by a mix of ideologies that can range from conspiracy theories to a blend of varying political ideologies. The 2021 Strategy notes that domestic terrorists are often fueled by ideologies that are fluid, evolving, and overlapping and can intersect with conspiracy theories or other forms of disinformation or misinformation. Specifically, all the seven threat assessments that we reviewed similarly state that domestic violent extremists adhere to a variety of motivations. For example, one assessment states that these individuals tend to develop personalized belief systems based on a mix of political concerns and a range of ideologies.[52] Figure 5 provides an overview on factors that influence domestic terrorists.

Agencies Have Taken Steps to Implement the 2021 Strategy, but Work Remains

Agencies in our review have taken steps to implement most of the activities we identified in the 2021 Strategy, but some work remains under each pillar.[53] These steps include a mix of new and preexisting efforts. They include sharing information (Pillar 1), preventing domestic terrorism (Pillar 2), disrupting and deterring domestic terrorism (Pillar 3), and confronting long-term contributors (Pillar 4). We found that agencies have taken some steps to implement most activities under each pillar.

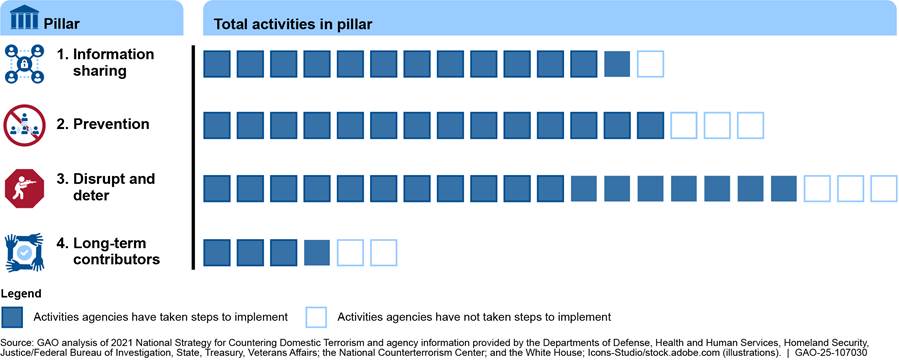

The 2021 Strategy tasks some federal agencies by name to take action to implement the 2021 Strategy and, in other cases, tasks the federal government in general to take certain actions. We reviewed the 2021 Strategy and associated Fact Sheets and identified a total of 58 statements (or activities) that task a responsible entity to take steps to counter domestic terrorism. Of these 58 activities, the 2021 Strategy tasks 31 activities to the federal government in general, 22 activities to specific agencies, seven activities to law enforcement, and two activities to the intelligence community.[54] Figure 6 below provides an overview of the number of activities in which agencies reported taking steps to implement the 2021 Strategy. Appendix II provides a detailed list of 2021 Strategy activities we identified and corresponding examples of steps that federal agencies reported taking to implement the 2021 Strategy.[55]

Figure 6: Number of Activities, by Pillar, in Which Federal Entities Have Taken Steps to Support Implementation of the 2021 National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism, as of March 2025

Note: We reviewed the 2021 Strategy, and the June 2021 and June 2023 White House Fact Sheets related to the 2021 Strategy and identified implementation activities under each pillar that task a specific agency or the federal government in general to take steps to counter domestic terrorism and identified 58 such activities. The 2021 Strategy has four pillars: (1) understand and share domestic terrorism-related information, (2) prevent domestic terrorism recruitment and mobilization to violence, (3) disrupt and deter domestic terrorism activity, and (4) confront long-term contributors to domestic terrorism. The purpose of our review was to identify what steps, if any, agencies took to implement the 2021 Strategy, including both new activities that agencies have implemented since the Strategy was issued in 2021 and preexisting activities that agencies have maintained. Of the nine activities for which we did not find steps that agencies have taken to implement, the 2021 Strategy tasked eight activities to the federal government in general and one activity to law enforcement. We did not evaluate individual agency steps to determine whether the agencies completed implementation of certain activities we identified in the 2021 Strategy.

Agency Steps to Implement the 2021 Strategy Include a Mix of New and Preexisting Efforts

Federal agencies’ efforts to implement the 2021 Strategy’s pillars and goals include a mix of new and preexisting steps. The 2021 Strategy acknowledges that the federal government had preexisting efforts to respond to domestic terrorism. Some 2021 Strategy activities explicitly direct agencies to implement new steps, while other activities do not specify whether agency steps should be new.

New efforts. Agencies undertook some new activities to implement the 2021 Strategy since June 2021. These efforts include the following, for example:

· DOJ and State jointly established the Counterterrorism Law Enforcement Forum in Europe, held annually since May 2022. The forum aims to bring together international governments, law enforcement entities, and other relevant partners to address domestic terrorism and violent extremism, as well as share lessons learned.

· DHS CP3 funded Invent2Prevent, which launched in spring 2021 to help high school and university students develop programs, such as online games and digital content, that prevent targeted violence and terrorism.

· Within DHS, the Science and Technology Directorate funded a research grant with the Institute of Strategic Dialogue to produce a bimonthly report on online trends in U.S. domestic violent extremism.[56] The Institute of Strategic Dialogue published its first report in October 2024.

· Further, some federal agencies dedicated new funding and resources to existing programs to counter domestic terrorism. For example, in fiscal year 2021, funding for DHS CP3’s Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention grants program increased from $10 million to approximately $20 million annually.[57]

Preexisting efforts. Agency officials also identified some efforts to counter domestic terrorism that were established before the 2021 Strategy was issued that support the 2021 Strategy’s implementation. These efforts include the following, for example:

· DHS I&A first assigned personnel to fusion centers to share and receive domestic terrorism information in 2006. DHS officials told us that these positions help fusion centers build capacity and share information between federal, state, and local entities and that they continue to do so.[58]

· DHS I&A’s National Threat Evaluation and Reporting Office established a Master Trainers Program in 2020 to certify federal and nonfederal entities in behavioral threat assessment and management techniques to prevent targeted violence, including domestic terrorism.[59]

· FBI officials assigned to JTTF offices told us that, in general, their roles and responsibilities with respect to domestic terrorism were preexisting and already aligned with the 2021 Strategy’s goals.[60]

· NCTC officials stated that while their work is not in direct response to the 2021 Strategy, they reprioritized some existing activities relevant to the 2021 Strategy after it was issued. For example, NCTC officials said some of their unclassified products address general terrorism prevention techniques that may apply to domestic terrorism. These officials also noted that the NCTC supports other agencies that are compiling information and data related to terrorism prevention efforts.

Agencies Have Taken Steps to Implement Most 2021 Strategy Activities Under Each Strategic Pillar

Information sharing (Pillar 1). Federal agencies have taken steps to implement most of the activities we identified in the 2021 Strategy to understand and share domestic terrorism information with nonfederal partners, including state, local, tribal, territorial, and private sector entities. Specifically, as of March 2025, we found that agencies have taken steps to implement 13 of 14 activities under this pillar. The 2021 Strategy tasked five activities to specific agencies (including DHS, the FBI, the NCTC, State, and Treasury).[61] Examples of steps agencies have taken include the following:

|

Pillar 1: Understand and Share Domestic Terrorism-Related Information

The federal government will · enhance domestic terrorism-related research and analysis, · improve information sharing across all levels within, as well as outside, the federal government, and · illuminate transnational aspects of domestic terrorism. Source: GAO analysis of agency information and 2021 National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism; Icons-Studio/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO‑25‑107030 |

· DHS officials reported taking steps to share domestic terrorism-related information by, among other things, assigning DHS I&A personnel to fusion centers to increase local fusion center capacity since 2006. We spoke with officials from JTTFs, fusion centers, and DHS I&A personnel assigned to fusion centers in seven states about their activities that respond to, or align with, the 2021 Strategy. DHS I&A personnel stated that information sharing—their primary role—aligns with Pillar 1 of the 2021 Strategy by sharing intelligence reports, written products, and briefings between federal and nonfederal partners. Some officials reported sharing key practices and lessons learned on domestic terrorism and other threats via regular and informal meetings with fusion centers, JTTFs, and other state and local partners.

· FBI officials in JTTFs stated that they routinely share information with federal and nonfederal partners nationwide on a variety of threats, including domestic terrorism. In particular, FBI, DHS, and the NCTC engaged to update the Mobilization Indicators booklet in 2021 to include information specific to domestic terrorism.[62] Agencies provide this resource to federal, state, and local partners to help determine whether individuals are preparing to engage in violent extremist activities.

· State and Treasury officials reported that they shared information with international partners to designate foreign entities with connections to domestic terrorist activity as Foreign Terrorist Organizations or Specially Designated Global Terrorists.[63] According to State, these designations are part of federal efforts to counter domestic terrorism and bar U.S. individuals from supporting these groups or receiving training from them. For example, in April 2020, State designated the Russian Imperial Movement and, in 2024, designated the Nordic Resistance Movement as terrorist organizations.

None of the federal agencies in our review provided information on steps that they have taken to implement one activity under this pillar: ensuring that they apply the full range of intelligence collection tools to domestic terrorism threats that become international through connectivity to foreign actors.[64] The 2021 Strategy tasked this activity to the federal government in general, rather than to a specific agency.

|

Pillar 2: Prevent Domestic Terrorism Recruitment and Mobilization to Violence

The federal government will: · strengthen domestic terrorism prevention resources and services and · address online terrorist recruitment and mobilization to violence by domestic terrorists. Source: GAO analysis of the 2021 National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism and information provided by federal agencies in our review; Icons-Studio/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO-25-107030 |

Prevention (Pillar 2). Federal agencies have taken steps to implement most of the activities related to preventing domestic terrorism that we identified in the 2021 Strategy.[65] Specifically, as of March 2025, we found that agencies have taken steps to implement 14 of 17 activities under this pillar. The 2021 Strategy tasked DHS to take the greatest number of activities (six of 17).[66] Examples of steps agencies have taken include the following:

· DHS has provided increased resources and funding to federal and nonfederal partners to prevent domestic terrorist activity. For example, DHS CP3’s Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention grants fund state and local efforts to prevent domestic terrorism. Since 2021, DHS has provided approximately $18 million to $20 million to grantees through this grant program annually, such as state emergency management departments, schools and universities, and community programs.[67]

|

Behavioral Threat Assessment and Management (BTAM) Teams Behavioral Threat Assessment and Management teams include law enforcement, mental health and education professionals, and other civil society partners to prevent potential acts of terrorism. Behavioral Threat Assessment and Management teams proactively respond to individuals exhibiting concerning behavior by providing various supportive services. The Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention grants help to fund Behavioral Threat Assessment and Management teams in local communities. For example, in fiscal years 2023 and 2024, DHS awarded Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention grant funding to the Colorado fusion center to develop local Behavioral Threat Assessment and Management teams and related initiatives. Colorado fusion center officials told us they can use this funding to establish four “regional coordinators” who create local Behavioral Threat Assessment and Management teams, share public awareness campaigns, and develop resources for Behavioral Threat Assessment and Management teams.

Source: DHS and Colorado Information Analysis Center; Agency logos courtesy of respective agencies. | GAO-25-107030 |

· In 2023, DHS partnered with several agencies to launch the Prevention Resource Finder website, which provides nonfederal partners with community support, grant information, and evidence-based research, as shown in figure 7.[68] According to the publicly accessible website, it is intended to provide resources to those who may be involved in preventing targeted violence and terrorism, such as law enforcement, mental health professionals, and educators.

· In April 2021, DOD directed the secretaries of the military services to develop training for service members separating or retiring from the military on potential targeting by violent extremist actors.[69] DOJ officials also reported providing training to military personnel and the general public on terrorist recruitment and mobilization.

Agencies have not yet taken steps to implement the remaining three of 17 activities in the 2021 Strategy to prevent domestic terrorism. The 2021 Strategy tasks all three of these activities to the federal government in general. Specifically, the agencies in our review did not identify any activities to

· reduce the supply and demand of online terrorism recruitment materials,[70]

· reduce access to assault weapons and high-capacity magazines,[71] or

· implement a mechanism by which veterans can report recruitment attempts by violent extremist actors.[72]

|

Pillar 3: Disrupt and Deter Domestic Terrorism

Activity The federal government will · enable appropriate enhanced investigation and prosecution of domestic terrorism crimes, · assess potential legislative reforms, and · ensure that screening and vetting processes consider the full range of terrorism threats. Source: GAO analysis of agency information and 2021 National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism; Icons-Studio/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO-25-107030 |

Disrupt and deter (Pillar 3). Agencies have taken steps to implement 18 of 21 of the activities we identified under Pillar 3 that task agencies to take steps to disrupt and deter domestic terrorism, but agencies did not report taking steps to implement the remaining three activities.[73] While the 2021 Strategy does not identify lead agencies for each of the four strategic pillars, the 2021 Strategy specifically identifies the FBI as the lead federal law enforcement and intelligence agency for investigating all forms of terrorism, including domestic terrorism. Therefore, the 2021 Strategy tasked the greatest number of activities (nine of 21) to implement Pillar 3 to DOJ or the FBI.[74] Examples of steps agencies have taken include the following:

· FBI officials reported that JTTFs coordinate with fusion centers to share information about domestic terrorism threats and investigations, as discussed above. Officials from four of seven fusion centers who we spoke with stated that they have observed an increase in the volume of FBI intelligence products since 2021.

· DOJ officials reported providing training to prosecutors. DOJ officials also told us in November 2023 that they plan to hire and train 180 new positions related to domestic violent extremism and violent crime. As of September 2024, DOJ officials reported that they had filled 127 of these positions.

· In December 2021, DOD updated its definition of prohibited extremist activity among military personnel in response to an April 2021 memo from the Secretary of Defense and in alignment with a statement in the 2021 Strategy indicating that DOD is doing so.

· DOD officials reported that they are in the process of responding to recommendations made by its Countering Extremist Activity Working Group, which aligns with the goals of the 2021 Strategy.[75] As of October 2024, DOD officials reported that DOD had implemented 13 out of 27 recommendations made by the working group.

We found that agencies in our review have not yet taken steps to implement some activities under Pillar 3, including one activity tasked to law enforcement, and two activities tasked to the federal government in general. For example, none of the agencies in our review reported taking steps to describe what interim measures federal law enforcement has taken to ensure flexibility in human resources to address domestic terrorism threats.[76]

|

Pillar 4: Confront Long-Term Contributors to Domestic

Terrorism Source: GAO analysis of agency information and 2021 National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism; Icons-Studio/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO-25-107030 |

Long-term contributors (Pillar 4). The White House and DOJ have taken steps to implement four of six activities we identified to confront long-term contributors to domestic terrorism (Pillar 4). The 2021 Strategy tasks the White House Domestic Policy Council with coordinating the federal government’s response to long-term contributors to domestic terrorism, with leadership from relevant agencies. However, it also acknowledges that the federal government cannot solely address these contributors and states that agencies should partner with civil society to implement these activities.

The 2021 Strategy identifies several contributors, including racism and bigotry, gun violence, and the influence of conspiracy theories. However, the 2021 Strategy does not specify which agencies beyond the White House are responsible for implementing particular activities and tasks all six activities to the federal government in general.

The White House has taken some steps to address long-term contributors to domestic terrorism as identified in the 2021 Strategy. For example:

· The White House established an interagency policy committee in December 2022 focused on addressing bias and discrimination. This policy committee subsequently issued the National Strategy to Counter Antisemitism in May 2023 and the National Strategy to Counter Islamophobia and Anti-Arab Hate in December 2024.

· The White House has further hosted the United We Stand summit to address racism and violence since the 2021 Strategy was issued.[77]

In addition, DOJ has taken some steps to address bias in law enforcement, which the 2021 Strategy identifies as a long-term contributor to domestic terrorism. Specifically, DOJ officials reported providing training to law enforcement personnel on mitigating bias in law enforcement operations.

We found that the federal government has not yet taken steps to implement two of six statements related to confronting long-term contributors to domestic terrorism. In general, the agencies in our review did not identify steps they have taken to implement most of the activities related to Pillar 4. For example, agencies did not report taking steps to ensure that domestic terrorism threats are properly identified, categorized, and addressed or to counter the influence and impact of conspiracy theories.[78]

As discussed above, the majority of activities under each pillar for which agencies did not identify taking steps to implement were assigned to the federal government in general, as opposed to a specific agency. Specifically, of the nine activities for which we did not find steps that agencies have taken to implement, the 2021 Strategy tasked eight activities to the federal government in general and one activity to law enforcement. We further discuss our assessment of the 2021 Strategy, including the extent to which it addresses roles, responsibilities, and milestones, later in this report.

Agencies Conducted Joint Activities and Identified Lessons Learned with Federal and Nonfederal Partners

We identified 10 activities in the 2021 Strategy that explicitly task multiple agencies to take steps to counter domestic terrorism.[79] In addition, the 2021 Strategy directs agencies or the federal government to coordinate with other entities, including civil society partners, to implement certain actions.

Federal Agencies Engage to Conduct Joint Activities

The 2021 Strategy directs federal agencies to conduct some joint activities to counter domestic terrorism. For example, the 2021 Strategy states that the FBI and DHS will enhance the public’s understanding of assistance available to the public related to violent extremism, including mental health resources. Further, the 2021 Strategy tasks agencies to develop a website on domestic terrorism prevention resources. To implement these and other activities, agencies took the following steps:

· DHS engaged with several federal agencies to launch the Prevention Resource Finder website in 2023.

· DOJ officials stated that they provided training to DOD personnel on domestic violent extremism.

· State and DOJ cohosted the annual Counterterrorism Law Enforcement Forum in 2022, 2023, and 2024.

· Treasury officials stated that the agency contributed to domestic terrorism investigations by providing financial analysis on suspected terrorist financing.

Federal Agencies Engage with Domestic and International Partners to Identify Lessons Learned

We found that federal agencies engage with domestic and international nonfederal partners to identify domestic terrorism-related lessons learned by participating in conferences, working groups, and other information-sharing venues, such as fusion centers. The 2021 Strategy includes that agencies can and should continue to learn from domestic and international partners to prevent, disrupt, and respond to domestic terrorism. DHS, DOJ, and State officials told us that they continue to incorporate key practices and lessons learned as they engage in activities to implement the 2021 Strategy.[80]

Domestic efforts. To incorporate U.S. lessons learned into federal efforts to counter domestic terrorism, federal agencies engage with domestic nonfederal partners, including through conferences, working groups, and state-run fusion centers. For example:

· Treasury officials stated that they coordinated with private sector companies to share information on the financing of domestic violent extremist activity by conducting a roundtable with nonfederal partners in April 2023. Treasury also developed a webpage of resources on terrorist financing.

· Federal agencies engage with domestic nonfederal partners in several forums, such as JTTF Executive Boards and an annual conference hosted by the National Fusion Center Association, to share ideas and enhance fusion center capabilities.[81] Officials from one fusion center told us that this conference is their primary venue for sharing key practices and lessons learned on domestic terrorism and related threats.

· State and local officials from six of the seven fusion centers we spoke with stated that they have seen improvements in the volume or usefulness of domestic terrorism-related information that the federal government shares with nonfederal partners since 2021.

International efforts. To engage with international partners to counter domestic terrorism and share lessons learned, agencies leverage conferences and working groups.[82] For example:

· DOJ and State co-host the Counterterrorism Law Enforcement Forum, discussed above, to convene international partners to counter the threat of racially and ethnically motivated violent extremism.[83] This annual forum includes representatives from around 40 countries from both governmental and nongovernmental entities.

· Since 2015, DHS Science and Technology Directorate has co-chaired a research working group with the Five Eyes countries to prevent terrorism.[84] DHS officials told us that the working group developed joint priorities in 2022 to address threats related to violent extremism and also convened in October 2024 to identify common policy objectives and shared research priorities. Further, in March 2024, DHS Science and Technology Directorate led the development of the International Academic Partnerships for Science and Security. This project is intended to connect international governmental, academic, and private sector partners to share information about targeted violence and terrorism.

· State Department officials stated that they engage bilaterally with allies to discuss lessons learned and share information about domestic terrorism threats. For example, State and German government partners shared information on domestic terrorism threats, including racially and ethnically motivated violent extremism.

· Representatives we interviewed from the governments of Germany and the United Kingdom confirmed that they partner with the U.S. government to share information and lessons learned related to domestic terrorism and violent extremism. Specifically, German representatives from the Ministry of the Interior’s Division on Countering Right- and Left-Wing Terrorism, Extremism, and Politically Motivated Crime stated that the United States has provided useful intelligence and lessons learned regarding extremist groups operating in Germany.[85] For example, U.S. officials have engaged with Germany to discuss threats, disinformation, and conspiracy theories from racially and ethnically motivated violent extremists. United Kingdom government representatives told us that, in March 2024, officials from the Home Office traveled to the United States to learn more about how DHS, DOJ, the NSC, State, Treasury, and other U.S. entities approach domestic terrorism.[86]

The 2021 Strategy Is Missing Most of the Desirable Characteristics of an Effective National Strategy

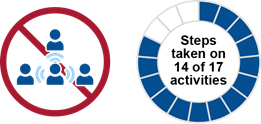

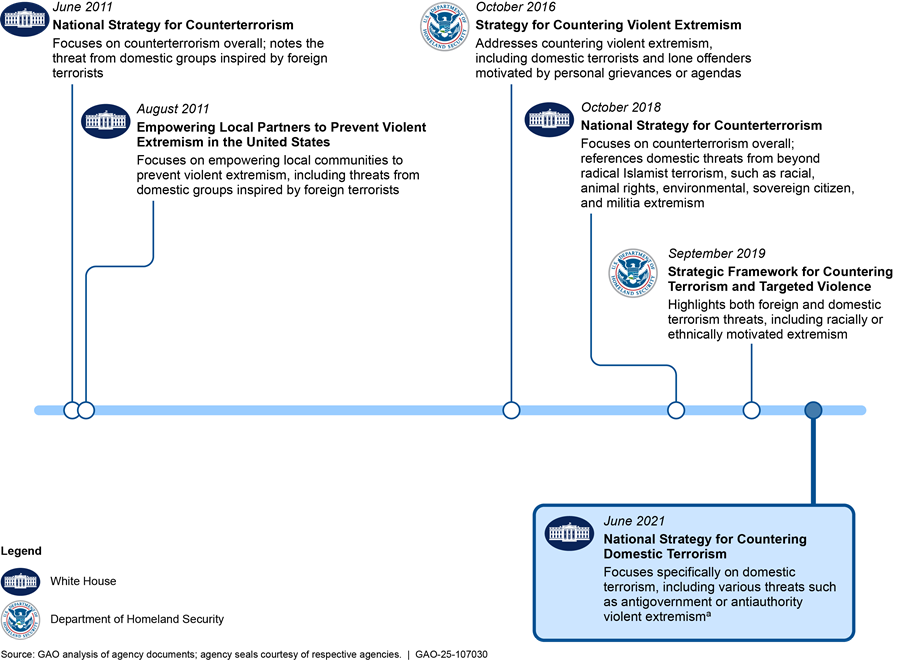

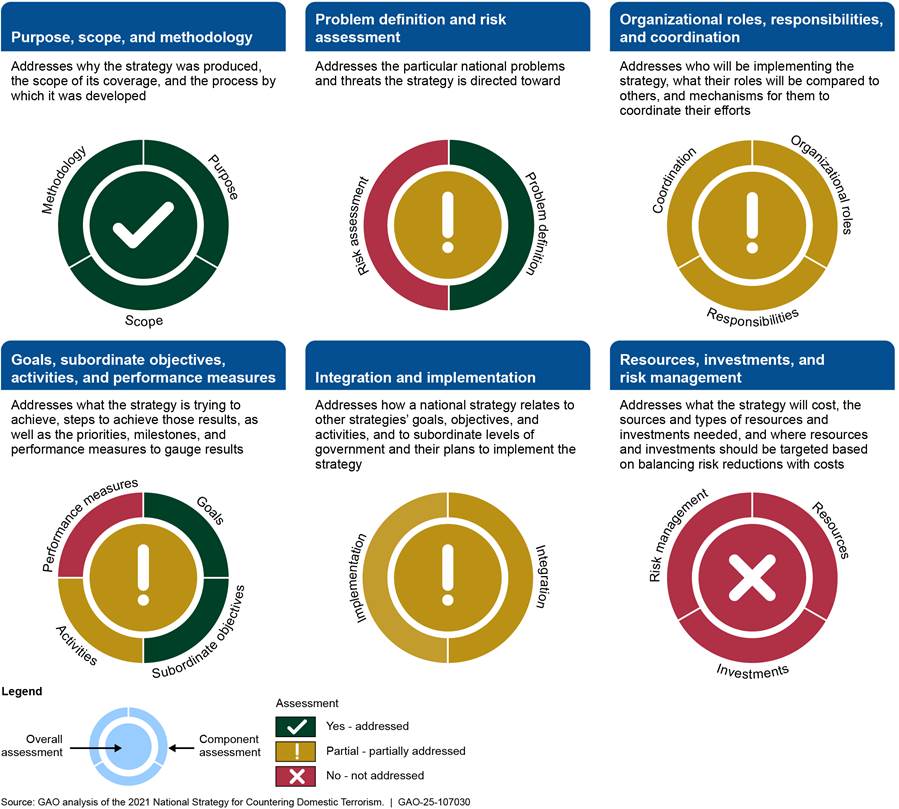

Although we were able to identify a number of steps that agencies have taken to implement 2021 Strategy activities, the 2021 Strategy is missing most of the desirable characteristics of a national strategy. These characteristics would help guide the whole-of-government effort to counter domestic terrorism. Specifically, we found that the 2021 Strategy and its supporting documents fully address one of our six desirable characteristics for effective national strategies, lacked some elements of four characteristics, and did not address any element of one characteristic.[87]

We previously identified a set of six generally desirable characteristics to aid responsible parties in developing and implementing national strategies, to enhance such strategies’ usefulness in resource and policy decisions, and to better assure accountability.[88] In our prior work, we noted that a national strategy should ideally contain all these characteristics. Figure 8 provides a summary of our evaluation of the 2021 Strategy against these characteristics.

Figure 8: Extent to Which the 2021 National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism Addresses GAO’s Desirable Characteristics of an Effective National Strategy

The 2021 Strategy Fully Addresses One Desirable Characteristic

The 2021 Strategy fully addresses the purpose, scope, and methodology characteristic.

Purpose, scope, and methodology. This characteristic addresses why the 2021 Strategy was produced, the scope of its coverage, and the process by which it was developed. Regarding the purpose, or why the 2021 Strategy was produced, the 2021 Strategy articulates the need for a comprehensive, government-wide approach to address domestic terrorism while protecting the rule of law and safeguarding individuals’ civil rights and civil liberties. It also states that the 2021 Strategy’s approach will help reduce the factors contributing to inciting domestic terrorism online that exacerbate the spread of calls to violence. Additionally, the 2021 Strategy outlined its scope by organizing how the federal government will address the domestic terrorist threat around four pillars, or main goals and subordinate goals.[89] It also acknowledges that the federal government needs to work with critical partners in state, local, territorial, and tribal governments in civil society; the private sector; academia and local communities; and foreign partners.

Although the 2021 Strategy itself does not include a section on the methodology used for its development, the June 2021 White House Fact Sheet indicates that the White House consulted with stakeholders to develop the Strategy. A subject matter expert familiar with the 2021 Strategy’s development stated that such consultations sought to understand what support and resources were needed to address domestic terrorism, among other things. NSC officials stated that they have met with nonfederal stakeholders repeatedly to understand their views on the domestic terrorism threat.

In addition, subject matter experts and agency officials we interviewed stated that White House officials sought their input and those of other relevant stakeholders, both domestic and foreign, in 2021 during the 2021 Strategy’s development. For example, DHS and DOJ officials stated that they attended meetings hosted by the NSC to discuss details related to the 2021 Strategy during the Biden Administration’s comprehensive review of domestic terrorism in early 2021.[90] In addition, some subject matter experts noted that the administration’s efforts to obtain their perspectives on the 2021 Strategy improved in comparison with previous efforts to elicit similar input to support the development of the national strategy for countering violent extremism in 2011.

The 2021 Strategy Partially Addresses Four Desirable Characteristics

The 2021 Strategy partially addresses the following four characteristics: (1) problem definition and risk assessment; (2) organizational roles, responsibilities, and coordination; (3) goals, subordinate objectives, activities, and performance measures; and (4) integration and implementation.

Problem definition and risk assessment. Our desirable characteristics state that strategies should include a detailed discussion or definition of the problems the strategy intends to address, their causes, and the operating environment. In addition, this characteristic entails a risk assessment, including an analysis of the threats to, and vulnerabilities of, critical assets and operations.

The 2021 Strategy defines the problem of domestic terrorism by acknowledging that domestic terrorism poses a serious and evolving threat. The 2021 Strategy incorporates a federal law definition of domestic terrorism.[91] In addition, the 2021 Strategy offers an assessment of threats identified by the intelligence community as of March 2021.[92] For example, it states that racially or ethnically motivated violent extremists and militia violent extremists present the most lethal domestic violent extremism threats, with racially motivated violent extremists most likely to conduct mass casualty attacks against civilians and militia violent extremists typically targeting law enforcement and government personnel and facilities.

However, while the 2021 Strategy incorporates threat assessment information, the NSC did not include a risk assessment in either the 2021 Strategy or in the supporting documents that we reviewed that examines how the threats relate to the potential consequences to, and vulnerabilities of, critical assets and operations.[93] Our prior work states that conducting risk assessments is important because they can help policy leaders identify a broader range of considerations than those identified by threat assessments alone.[94]

A risk assessment could help agencies make more informed management decisions about the resource allocations required to minimize risks and maximize returns on resources expended to support the 2021 Strategy.

Organizational roles, responsibilities, and coordination. Our desirable characteristics state that a national strategy should identify which organizations will implement the strategy, their roles and responsibilities, and mechanisms for coordinating their efforts.

The 2021 Strategy addresses organizational roles by acknowledging that the federal government and other members of civil society need to play a role in addressing domestic terrorism, such as by partnering with foreign allies and professionals from the technology, education, and public health sectors, among others. Further, the 2021 Strategy includes that these partners provide critical analysis and expertise needed to help address the multifaceted nature of the domestic terrorism threat. The 2021 Strategy also reinforces the FBI as the lead federal law enforcement and intelligence agency for investigating all forms of terrorism, including domestic terrorism.

The 2021 Strategy states that it will ensure rigorous oversight and accountability but does not specify which entity is responsible for doing so. DHS and DOJ agency officials stated that they believed the NSC was responsible for overseeing the effort and ensuring accountability. However, officials from most other agencies that we interviewed did not know how the NSC ensures accountability and oversight of agencies’ 2021 Strategy-related activities as a whole.[95] The 2021 Strategy and its supporting documents do not clearly identify which organizational entity, if any, is responsible for leading or overseeing the implementation of the whole effort.

Further, several subject matter experts whom we interviewed indicated that they were not aware of which federal entity was leading the effort. For example, one academic expert said that they thought DOJ might be the lead entity in theory but did not know if a federal entity was in charge in practice. NSC officials stated that they established an interagency policy committee in 2022 to address antisemitism, Islamophobia, and related forms of bias and discrimination and that they also worked with the Domestic Policy Council within the NSC to examine ways to reduce hate-fueled violence.[96] While these efforts support some pillars within the 2021 Strategy, the NSC did not clarify whether these entities or any other entities within the NSC are responsible for leading the 2021 Strategy as a whole.

With regard to responsibilities, the 2021 Strategy names eight federal agencies and, as discussed earlier, provides some details on specific activities that they are conducting. It also identifies some agency roles and responsibilities. For example, the FBI’s general responsibilities include leading law enforcement and domestic intelligence efforts to disrupt and deter terrorism, as well as collecting, analyzing and sharing intelligence related to domestic terrorism (as reflected in Pillars 3 and 1), and DHS produces and shares domestic terrorism-related analysis and content with its federal and nonfederal government partners (as reflected in Pillar 1).

However, while the 2021 Strategy mentions other federal entities, such as the Department of Veterans Affairs, it does not include any explicit statements about what other activities the agency may be responsible for leading or implementing. As discussed above, the 2021 Strategy tasks more than half (31 of 58) of the activities we identified to the federal government in general and does not include clear agency roles and responsibilities for these activities. According to DHS and DOJ officials, the implementation plan does assign additional roles and responsibilities to federal agencies, but officials from other agencies, such as DOD, Veterans Affairs, and Health and Human Services told us they were unaware of an implementation plan.

With regard to coordination, the 2021 Strategy specifies that the federal government should coordinate and collaborate their program activities at the policy level, and the NSC reported that it coordinates 2021 Strategy-related activities through the interagency process. The 2021 Strategy states that the Domestic Policy Council within the NSC shall coordinate activities related to addressing long-term contributors to domestic terrorism under Pillar 4. DHS, DOJ, and FBI officials stated that the NSC initially hosted regular meetings focused on coordinating domestic terrorism activities in the months following the 2021 Strategy’s release.[97] DHS officials stated that these efforts are now held on an annual basis. However, when we spoke with other agencies, such as Health and Human Services and Veterans Affairs, officials could not describe how the NSC coordinated with them to implement the 2021 Strategy.

The NSC’s level of coordination with all relevant agencies to implement the 2021 Strategy varies. For example, DHS, DOJ, FBI, and NCTC officials indicated that they respond to an annual request by the NSC to submit a list of their 2021 Strategy-related activities to coordinate departmental efforts to implement the 2021 Strategy with the NSC. However, other federal partners, such as DOD, Veterans Affairs, Treasury, and Health and Human Services, said they were not aware of a similar request. NSC officials stated that they meet with relevant federal entities to discuss domestic terrorism threats and how it relates to the four pillars of the 2021 Strategy. However, NSC officials did not specify details, such as which agencies are responsible for how these activities are coordinated among all relevant agencies, nor did they explain why the 2021 Strategy does not include this information.

In addition to being one of our desirable characteristics of a national strategy, clearly defining and communicating roles and responsibilities—particularly in cases where more than one federal agency (or more than one organization within an agency) must coordinate—is an important step in reducing the potential for fragmentation. Fragmentation can occur when multiple federal agencies are seeking to achieve the same goal. Without clarifying which entity is responsible for overseeing the effort as a whole and consistently identifying lead entities responsible for each activity, it is difficult to hold agencies accountable for meeting the goals and objectives of the 2021 Strategy, or any national strategy, in effect, to counter domestic terrorism, that they are responsible for implementing.

Goals, subordinate objectives, activities, and performance measures. Our desirable characteristics state that a national strategy should include what the strategy is trying to achieve (goals and objectives); steps to achieve those results (activities); and priorities, milestones, and performance measures to gauge results. The 2021 Strategy identifies and organizes its goals under four pillars, includes subordinate objectives, and identifies some 2021 Strategy-related activities. For example, the main goal of Pillar 2 is to prevent domestic terrorism recruitment and mobilization to violence and the 2021 Strategy identifies strengthening domestic terrorism prevention and resources as a subordinate goal. Within this subordinate goal, we identified 14 activities that agencies should take steps to implement. However, we found that the 2021 Strategy does not include other elements of this characteristic, such as consistently specifying milestones for when these activities are to be achieved, or performance measures to measure the overall progress of the 2021 Strategy.

The 2021 Strategy itself does not include milestones for implementation activities. The NSC stated that it established some milestones (or timeframes) for the implementation of 2021 Strategy-related activities in 2021. DHS and NCTC officials also told us that the NSC provided milestones for some activities in its implementation plan. However, neither the NSC nor any of the other agencies in our review provided details on any specific milestones related to 2021 Strategy activities.

The 2021 Strategy also does not include performance measures. DHS officials stated that they have provided some performance information to the NSC upon request, such as the number of intelligence products related to domestic terrorism and the number of trainings delivered to partners. However, DHS officials stated that some activities do not lend themselves to quantitative measures. The NSC stated that its efforts to establish milestones, as discussed above, allow NSC staff to track and assess the resources that agencies are assigning to 2021 Strategy-related activities and evaluate agencies’ progress in implementing these activities. However, in its response to us, the NSC did not identify any specific 2021 Strategy-related milestones or performance measures. In addition, officials from the other federal agencies that we interviewed indicated that they were not aware of, nor do they report, any specific performance measure information to the NSC to help oversee the performance of the 2021 Strategy or to guide their efforts in evaluating any activities.

Some of the subject matter experts we interviewed told us that it is not clear how 2021 Strategy-related activities are evaluated, if at all. While these experts acknowledged that developing performance measures to assess activities designed to address domestic terrorism may be difficult because one cannot prove that an event did not occur, they pointed to a growing body of research exploring the use of proxy indicators to gain insights on the progress of activities and to gauge success. For example, DHS Science and Technology Directorate evaluates local programs designed to prevent domestic terrorist activity to identify ways that may assist in evaluating the effectiveness of these activities.[98] DHS CP3 also indicated that the number of states and territories that are developing their own strategies could be used as a measure to gauge progress in terrorism prevention. Consistently identifying and developing milestones and performance measures for activities related to the 2021 Strategy or any national strategy, in effect, to combat domestic terrorism would help agencies to achieve results within specific timeframes and to assess the extent to which their efforts are addressing domestic terrorism.

Integration and implementation. Our desirable characteristics state that national strategies should address how they relate to (1) other strategies’ goals, objectives, and activities; and (2) subordinate levels of government and their plans to implement the strategy. The NSC identified the 2023 National Strategy to Counter Antisemitism as a new effort that complements the 2021 Strategy’s main goal of confronting long-term contributors to domestic terrorism (Pillar 4). However, neither the 2021 Strategy nor its accompanying documents further define how they may integrate with other national strategies’ goals, objectives, and activities or how they relate to other subordinate levels of government and their plans to implement the 2021 Strategy. NSC officials did not explain why the 2021 Strategy does not include this information.

For example, the 2021 Strategy could discuss how its scope complements, expands upon, or overlaps with other national strategies, such as those for cybersecurity or international counterterrorism.[99] The 2021 Strategy could also discuss, as appropriate, various strategies and plans produced by the state, local, private, or international sectors. According to DHS CP3, seven states have developed strategies to address domestic terrorism and violent extremism, and about 36 states and territories have expressed interest in doing so.[100] Yet the 2021 Strategy does not indicate how these efforts may contribute to define the roles, responsibilities, and capabilities of implementing parties more effectively. By identifying and addressing how activities related to the 2021 Strategy or any national strategy, in effect, to combat domestic terrorism may relate or overlap, if at all, to other strategies’ goals, objectives, and activities, the NSC could better position itself to integrate and oversee agency efforts.

Regarding implementation, as discussed above, we found that the 2021 Strategy includes 58 activities assigned to either specific federal entities or to the federal government in general. For example, it specifies that DOD is incorporating training for service members who are separating or retiring from the military on recruitment by violent extremist groups. While the 2021 Strategy itself contains limited additional information on specific implementation steps, officials from DHS, DOJ, and State told us that the classified implementation plan includes some additional guidance for classified activities. As discussed later, subject matter experts and nonfederal partners we interviewed identified challenges related to obtaining information about federal implementation activities.