BANK REGULATION

Agencies Should Finalize Rulemaking on Incentive Compensation

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25-107032. For more information, contact Michael E. Clements at (202) 512-8678 or clementsm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25-107032, a report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Financial Services, House of Representatives

Agencies Should Finalize Rulemaking on Incentive Compensation

Why GAO Did This Study

Incentive-based compensation can motivate good performance but also encourage risky behavior. Bank failures in early 2023 and executive bonuses one bank paid on the day it failed raised questions about compensation practices at large banks.

GAO was asked to review compensation at three failed banks. This report examines (1) executive compensation packages at the failed banks and a peer bank group, (2) executives’ stock transactions at the failed banks, (3) regulators’ review of executive compensation at selected large banks, and (4) efforts to finalize an incentive compensation rule.

GAO analyzed the most recent publicly available annual disclosures for 11 banks (three failed banks and eight peer banks selected for similarity in asset size and business lines); public disclosures on stock transactions by executives at the failed banks (January 2021–March 2023); and examination documentation (2017–2022) on compensation for 21 banks (10 banks with largest asset size, eight peer banks, and three failed banks). GAO also reviewed agencies’ proposed rules and public statements on the incentive compensation rulemaking since 2011.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations—one to each agency required to issue incentive compensation regulations—to jointly prescribe regulations or guidelines as soon as practicable. Each agency agreed with the recommendation.

What GAO Found

The structure and amount of executive compensation packages at three failed banks were similar to those of peer banks GAO reviewed. A median of 86 percent of executive compensation at the failed banks and 83 percent at the peer banks was incentive-based and tied to executive and bank performance. All the packages incorporated risk-mitigating elements that align with practices described in federal compensation guidelines. All the banks used financial measures of performance, such as return on equity and shareholder returns. Most banks also used nonfinancial measures, such as meeting goals for prudent risk management.

All the former top executive officers at the three failed banks received stock awards (totaling about $130 million) and made disposals (totaling about $214 million) from January 2021 through March 2023. Executives at two of the failed banks disposed of more than $17 million in the first quarter of 2023, which was similar to their disposals in the first quarter of the previous year.

Federal banking regulators use supervisory activities, such as ongoing monitoring and examinations, to review compensation issues and risks at large banks. From 2017 through 2022, regulators examined executive compensation at 15 of the 21 large banks GAO reviewed, including two of the three failed banks. Overall, regulators identified 10 supervisory concerns (matters requiring attention) related to compensation issues across eight institutions during this period. This included one supervisory concern in 2022 at the holding company of one of the failed banks, which was taking corrective action when the bank failed.

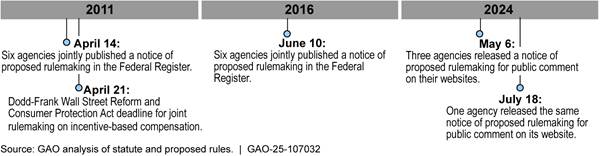

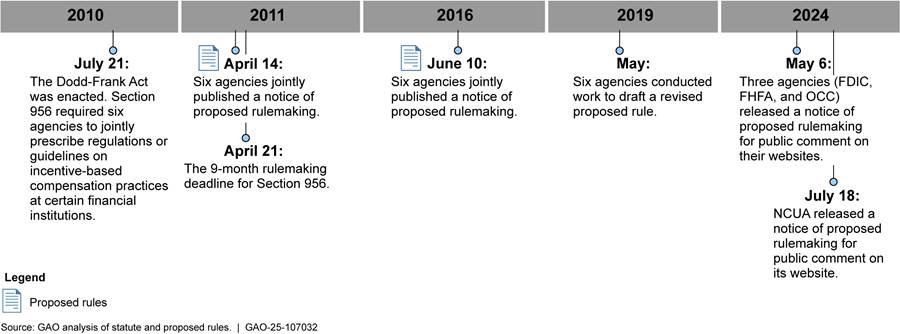

In 2010, Congress required six agencies to jointly prescribe regulations or guidelines on incentive compensation by April 21, 2011. The agencies formed a working group to draft and propose joint regulations but have yet to finalize them (see figure).

Leaders within and across the agencies hold differing views on regulatory approaches for incentive-based compensation arrangements. For example, some agency leaders advocate a principles-based approach that outlines general principles and objectives for discouraging inappropriate risk-taking. Others support an approach with more specific and stringent requirements. Reconciling these differences and jointly prescribing regulations or guidelines would help prevent excessive compensation arrangements at financial institutions that encourage inappropriate risks.

Abbreviations

|

CEO |

chief executive officer |

|

Dodd-Frank Act |

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act |

|

Federal Reserve |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

|

FDIC |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

|

FHFA |

Federal Housing Finance Agency |

|

NCUA |

National Credit Union Administration |

|

OCC |

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency |

|

SEC |

Securities and Exchange Commission |

|

|

|

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 20, 2025

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

Dear Ms. Waters:

Banks often link a portion of their executives’ compensation to individual or institutional performance, increasing pay when certain objectives or metrics are met. While this approach can create incentives for strong performance, it can also encourage risky behavior. The 2007–2009 financial crisis highlighted this issue, revealing that large, short-term profits led to generous bonus payments to bank employees without adequate regard to the longer-term risks they imposed on firms.

To help manage these risks, the banking agencies are required to prescribe standards for banks that prohibit compensation levels that are considered excessive or cause material financial losses to the banks.[1] Additionally, Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) directs six federal agencies to jointly promulgate regulations or guidelines to prohibit certain incentive-based compensation arrangements at large financial institutions, including banks.[2] The act required the six agencies to issue these regulations or guidelines by April 21, 2011. However, they have yet to fulfill this requirement.

In March 2023, state banking supervisors closed Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, followed by First Republic Bank in May of that year. As of June 30, 2024, the estimated total loss for the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank was $22.4 billion.[3] The estimated loss from the First Republic Bank failure was $16.3 billion. These failures, combined with bonus payouts at one bank on the same day as its failure, raised questions from the public and Members of Congress about bank executive compensation and its oversight by banking supervisors.[4]

In April 2023, we issued a preliminary report on the March 2023 bank failures. We issued two additional reports in March and November 2024 on communication and escalation of supervisory concerns at two federal banking regulators—the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve).[5]

You asked us to examine executive compensation at the failed banks. This report builds on our previous work related to the failed banks and examines the:

1. structure of executive compensation packages in 2022 and how they addressed risks at First Republic Bank, Signature Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank (failed banks) and a peer group of banks;

2. date, value, and nature of executive officers’ stock transactions at the three failed banks from January 2021 through March 2023;

3. extent to which federal banking regulators reviewed executive compensation at a selection of large banks in 2017–2022; and

4. efforts federal agencies have taken since 2010 to finalize rules on incentive-based compensation arrangements and any challenges they have faced.

For the first objective, we reviewed public disclosures for the three failed banks and a peer group of eight banks.[6] We analyzed each bank’s proxy statement (Schedule 14A), which includes compensation information for its named executive officers (that is, the chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and the next three highest-paid executives).[7] For Signature Bank, Silicon Valley Bank, and all selected peer banks, we reviewed 2023 proxy statements, which contain information on their 2022 compensation packages. For First Republic Bank, we reviewed its 2022 proxy statement, which contains information on 2021 compensation packages, because this was the most recent publicly available information prior to its May 2023 failure.[8] We also conducted a literature search for studies in peer-reviewed journals that analyzed executive compensation at financial institutions and interviewed stakeholders familiar with the field.

For the second objective, we reviewed publicly available disclosures of stock transactions submitted by the former executive officers of First Republic Bank, Signature Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and FDIC from January 1, 2021, through March 31, 2023.[9] We reviewed information on changes in bank securities holdings, including awards, acquisitions, and disposal dates and values, for executives named in the banks’ 2022 or 2023 proxy statements.[10] We also reviewed relevant laws and regulations on insider trading.

For the third objective, we reviewed examination documentation from 2017 through 2022 provided by the federal banking regulators—Federal Reserve, FDIC, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)—for a selection of 21 banks—three failed banks, eight peer banks, and the 10 largest banks by asset size. We also reviewed examination manuals and other agency documents on oversight of compensation processes.

For the fourth objective, we reviewed relevant rulemaking requirements in Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act, as well as agencies’ rulemaking agendas, proposed rules, congressional hearings, press releases, and public comments related to these requirements. For all of the objectives, we interviewed agency officials and selected industry stakeholders. For additional details regarding our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Statutes, Regulations, and Guidance Related to Bank Executive Compensation

Banks and their executives are subject to a variety of statutory and regulatory requirements related to executive compensation.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Act addresses executive compensation in several ways:

· The act places restrictions on compensation for executive officers at insured depository institutions. It requires the federal banking regulators to implement standards that prohibit certain bank representatives and employees from receiving compensation that is “excessive” or “could lead to material financial loss to the institution.”[11]

· The act also provides that FDIC may limit or prohibit any payments under severance-related “golden parachute” agreements and indemnification agreements to institution-affiliated parties.[12]

· The act empowers bank regulators to remove institution-affiliated individuals from office and prohibit them from participating in the affairs of any bank in certain circumstances.[13] The removal authority is one of several tools available to federal banking regulators to hold individuals accountable for violations and unsafe or unsound practices.

· Finally, the act provides FDIC the authority to hold senior executives of failed insured depository institutions personally liable for civil monetary damages for “gross negligence” or under state statutes that provide less stringent standards.[14]

In addition, the Internal Revenue Code places limits on compensation that is tax deductible for certain executives at publicly traded corporations, including some banks.[15] Compensation in excess of $1 million for each of certain executive officers is not deductible.

In 2022, SEC adopted a rule that implemented the provisions of Section 954 of the Dodd-Frank Act related to the “clawback” (recovery) of incentive-based compensation.[16] The final rule directs national securities exchanges to establish listing standards that require issuers to (1) implement clawback policies to recover incentive-based compensation received by current or former executive officers in the event that an issuer is required to prepare an accounting restatement and that incentive-based compensation is based on erroneously reported financial information, and (2) disclose their clawback policies and their actions under those policies.

Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act directs FDIC, the Federal Reserve, Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), OCC, and SEC to jointly issue regulations or guidelines that prohibit incentive-based payment arrangements, or any feature of such arrangements, at certain financial institutions that the agencies determine encourages inappropriate risks by financial institutions by providing an executive officer, employee, director, or principal shareholder of the institution with excessive compensation, fees, or benefits or that could lead to material financial loss to the institution. Financial institutions with $1 billion or more in assets are to be subject to the rules and they must disclose information on the structure of incentive-based compensation arrangements to the appropriate regulator.[17]

As further discussed in this report, as of January 2025 the regulators had not issued a final rule to implement Section 956.

In June 2010, the federal banking regulators issued interagency guidance on incentive compensation.[18] The guidance is intended to help ensure that banking organizations’ incentive compensation policies do not encourage imprudent risk-taking. The interagency guidance cites three principles for incentive-based compensation arrangements.[19] They should

1. provide employees incentives that appropriately balance risk and reward;

2. be compatible with effective controls and risk management; and

3. be supported by strong corporate governance, including active and effective oversight by the organization’s board of directors.

Federal Oversight of Financial Institutions

Several federal regulators oversee financial institutions. This includes three federal banking regulators that oversee banking organizations, including banks, savings associations, and bank and savings and loan holding companies:

· Federal Reserve supervises state-chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System; bank and savings and loan holding companies (including any nonbank subsidiaries); nationally chartered and state-chartered banks authorized to engage in international banking under the Edge Act and agreement corporations; and the U.S. operations of foreign banks.

· FDIC supervises insured state-chartered banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System, state-chartered savings associations, and insured state-chartered branches of foreign banks.

· OCC supervises national banks and federal savings associations and federally chartered branches and agencies of foreign banks.

Other regulators oversee other types of financial institutions:

· NCUA charters and regulates federally chartered credit unions, insures deposits, and examines most federal and state-chartered credit unions.

· SEC regulates the securities markets, including participants such as securities exchanges, broker-dealers, investment companies, and certain investment advisers and municipal advisers.

· FHFA regulates Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Bank System.[20] It oversees these entities to ensure they operate in a safe and sound manner to serve as a reliable source of liquidity and funding for housing finance and community investment.

Federal Banking Supervision

The federal banking regulators have broad authority to examine banks subject to their jurisdiction.[21] The Federal Reserve also has supervisory and regulatory authority for all bank holding companies.[22]

To carry out this authority, the federal banking regulators conduct ongoing monitoring as well as full-scope, on-site examinations of each insured depository institution they supervise generally once during each 12-month period.[23]

· Ongoing monitoring activities are designed to develop and maintain an understanding of the bank, its risk profile, and associated policies and practices. They serve to identify current and prospective issues that affect a bank’s risk profile or condition and play a role in determining future supervisory strategies.

· Examinations evaluate bank activities and management processes to ensure banks operate in a safe and sound manner, do not take excessive risks, and comply with laws and regulations. Targeted examinations may focus on one particular bank product, function, or risk and typically involve transaction testing. Horizontal reviews are a series of examinations focused on a single supervisory issue at several banks. They allow examiners to compare risk-management practices among banks, identify gaps in practices at specific banks, and help promote sound practices across the banking sector.

In instances in which regulators determine that bank behaviors or practices are deficient, they may issue supervisory concerns or enforcement actions.[24] Supervisory concerns communicate issues regulators identify during supervision to bank representatives, generally senior management or boards of directors. Under certain circumstances, the regulators may take informal or formal enforcement actions, depending on the severity of the circumstances.[25]

Three Failed Banks’ Executive Compensation Was Similar to Peer Banks, and Included Elements to Mitigate Risks

Structure and Amount of Executive Compensation Were Similar across Banks We Reviewed, and Mostly Performance-Based

The executive compensation at the three failed banks was similar to that of seven peer banks in terms of the structure of compensation packages and the amount of compensation the chief executive officer (CEO) and other executives received.

Structure of Compensation Packages

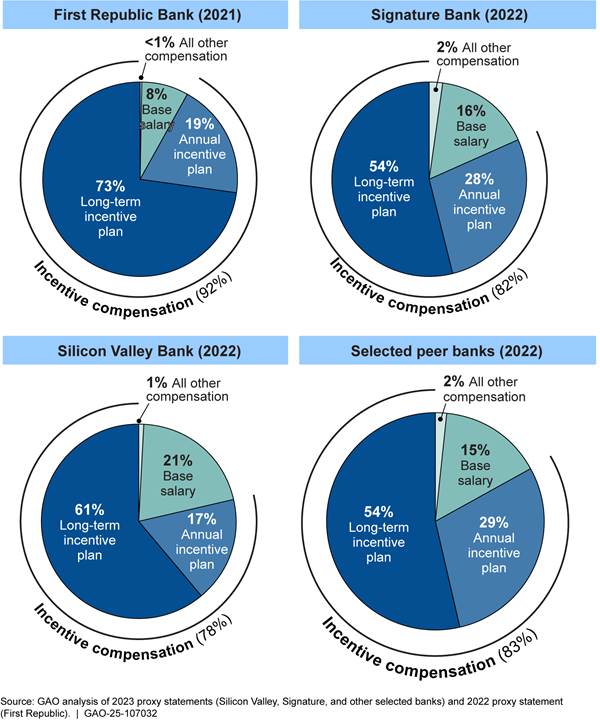

The 2022 executive compensation packages for the three failed banks (First Republic, Signature, and Silicon Valley) and seven peer banks were similar in that they generally consisted of a base salary (the smaller component) and an incentive plan (the larger component).[26] Base salary is fixed and guaranteed to executives. In contrast, incentive plans are performance-based, which means they are variable and not guaranteed.[27]

In 2022, base salary made up about 15 percent of total compensation for the executives at the 10 banks. The portion of executives’ total base salary at the three failed banks ranged from 8 percent at First Republic Bank to about 21 percent at Silicon Valley Bank. The median amount of base salary for the seven peer banks was about 15 percent of total compensation.

The portion of compensation that was incentive-based also was similar across the 10 banks and made up the majority of the compensation packages we reviewed. For example, the median of total compensation that was incentive-based at the three failed banks was about 86 percent and ranged from about 78 percent at Silicon Valley to about 92 percent at First Republic. The median amount of incentive compensation among the seven peer banks was about 83 percent of total compensation (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Components of Compensation Packages for Executive Officers at 10 Banks GAO Reviewed, by Median Share, 2021 or 2022

Note: The figure presents the median share of each compensation category for the 10 banks we reviewed. The compensation packages represent the named executive officers, which are the chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and the next three highest-paid executives. Our analysis compared First Republic Bank, Signature Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank to a group of seven U.S.-based banks with similar business lines that each had total assets between $100 and $250 billion at year-end 2022. The 2022 information for First Republic Bank was not publicly available because the bank did not release its 2023 proxy statement or publicly disclose its 2022 executive compensation prior to its failure on May 1, 2023. The banks’ long-term incentive plans generally assessed executive officers’ performance over 3 years and were granted over a vesting period of 3 years.

The structure of incentive plans at the 10 banks also was similar, comprising annual and long-term components with defined performance periods and goals. Long-term incentive plans generally constituted a larger share of total incentive compensation than did annual incentives. In 2022, the median amount of compensation payable under long-term incentive plans for the peer banks was about 54 percent of total compensation for all executives. It was about 61 percent for Silicon Valley, about 54 percent for Signature, and about 73 percent for First Republic (see fig. 1).

These long-term incentive plans were based on performance over a 3-year period. Payment for long-term incentive awards generally was deferred for 3 or 4 years and was delivered in the form of equity (most commonly, stock units) in the bank.[28] All of the 10 banks used stock units that were vested over specified periods of time as a form of equity in their compensation packages.[29]

Annual incentives almost always constituted a smaller proportion of total compensation than did long-term incentive plans. These plans were generally based on 12-month performance periods and paid in cash.[30] In 2022, the median annual incentive compensation was 29 percent of total executive compensation for the peer banks, 17 percent for Silicon Valley, 28 percent for Signature, and 19 percent for First Republic. First Republic was the only bank to include equity in its annual incentive plans. Half of these equity awards were delivered in restricted stock units that vested annually over 3 years.

The use of incentive compensation and equity compensation for executives aligns with certain practices described in the 2010 interagency guidance on sound compensation practices. According to the guidance, compensation arrangements for senior executives at large banks are better balanced when (1) a significant portion of incentive compensation is in equity that vests over multiple years, and (2) that equity is tied to the organization’s performance during the deferral period.[31] The guidance also recommends delaying incentive compensation beyond the performance period to discourage imprudent risk-taking.[32] This allows time for risk outcomes to materialize before payment. For example, if a bank fails, the executive’s stock may become worthless before they can sell it.

Amount of Compensation Packages

In 2022, the total amount of CEO compensation generally was similar at 9 banks we reviewed (see table 1). CEO compensation at two of the failed banks in 2022 was about $8.7 million at Signature and about $9.9 million at Silicon Valley, while the median CEO compensation among the selected peer banks was about $9.2 million. The amount of CEO base salary at all the banks was near $1 million.[33] CEO compensation at First Republic Bank was $17.8 million in 2021. Most of the difference between CEO compensation at First Republic and the other banks can be attributed to higher incentive compensation, both annual and long-term.

Dollars in millions

|

|

|

Incentive plans |

|

|

|

|

Base salary |

Annual |

Long-terma |

Totalb |

|

Failed banks |

|

|

|

|

|

First Republic Bank, 2021c |

$1.0 |

$4.6 |

$11.9 |

$17.8 |

|

Signature Bank, 2022 |

$1.2 |

$2.5 |

$4.9 |

$8.7 |

|

Silicon Valley Bank, 2022 |

$1.1 |

$1.5 |

$7.3 |

$9.9 |

|

Selected peer banks |

|

|

|

|

|

Median for seven banks, 2022 |

$1.1 |

$2.4 |

$5.5 |

$9.2 |

Source: GAO analysis of 2023 proxy statements (Silicon Valley, Signature, and other selected banks) and 2022 proxy statement (First Republic). | GAO‑25‑107032

Note: Our analysis compared First Republic Bank, Signature Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank to a group of seven U.S.-based banks with similar business lines that each had total assets of $100 billion–$250 billion at year-end 2022.

aAmounts shown reflect the fair value on the grant date, as recognized by the bank for financial statement reporting purposes in accordance with Financial Accounting Standards Board Accounting Standards Codification Topic 718. Award fair value is based on the closing price of the bank’s common stock on the date of grant.

bOther types of compensation (such as retirement contributions, use of company aircraft, and relocation expenses) generally make up less than 2 percent of total compensation and are not shown in this table.

cFirst Republic Bank’s 2022 information was not publicly available because the bank did not release its 2023 proxy statement or publicly disclose its 2022 executive compensation prior to its failure on May 1, 2023.

The median compensation of the other four executive officers also was similar at most of the banks we reviewed. The median compensation for the four non-CEOs at nine banks ranged from $3.2 million to $3.9 million. The median non-CEO compensation for First Republic in 2021 was $8.3 million. Most of the difference between First Republic and the other banks can be attributed to higher incentive compensation, both annual and long-term (see table 2). For more details, see appendix II.

Table 2: Median Compensation Package Amounts for Non-Chief Executive Officers at 10 Banks GAO Reviewed

Dollars in millions

|

|

|

Incentive plans |

|

|

|

|

Base salary |

Annual |

Long-terma |

Totalb |

|

Failed banks |

|

|

|

|

|

First Republic Bank, 2021c |

$0.6 |

$1.6 |

$6.0 |

$8.3 |

|

Signature Bank, 2022 |

$0.6 |

$0.9 |

$1.7 |

$3.3 |

|

Silicon Valley Bank, 2022 |

$0.7 |

$0.5 |

$2.0 |

$3.2 |

|

Selected peer banks |

|

|

|

|

|

Median for seven banks, 2022 |

$0.7 |

$1.2 |

$1.9 |

$3.9 |

Source: GAO analysis of 2023 proxy statements (Silicon Valley, Signature, and other selected banks) and 2022 proxy statement (First Republic). | GAO‑25‑107032

Note: Our analysis compared the compensation of four top executive officers, after the chief executive officer, of First Republic Bank, Signature Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank to a group of seven U.S.-based banks with similar business lines that each had total assets of $100 billion–$250 billion at year-end 2022.

aAmounts shown reflect the grant date fair value recognized by the bank for financial statement reporting purposes in accordance with Financial Accounting Standards Board Accounting Standards Codification Topic 718. Award fair value is based on the closing price of the bank’s common stock on the date of grant.

bOther types of compensation (such as retirement contributions, use of company aircraft, and relocation expenses) generally make up less than 2 percent of total compensation and are not shown in this table.

cFirst Republic Bank’s 2022 information was not publicly available because the bank did not release its 2023 proxy statement or publicly disclose its 2022 executive compensation prior to its failure on May 1, 2023.

Banks We Reviewed Used Similar Measures to Determine Incentive Awards, Including Financial and Nonfinancial Measures of Performance

The banks we reviewed used similar measures of performance or risk in designing annual and long-term incentive awards in 2022.[34] Financial measures used at these banks generally were tied to the bank’s financial performance, while nonfinancial measures were focused on a bank’s or an individual employee’s performance or a risk outcome.

In 2022, all three failed banks and seven peer banks used financial measures of performance (such as return on equity or earning per share) in their annual and long-term incentive plans (see table 3). Two of the failed banks and five peer banks used nonfinancial measures in their annual incentives, and two peer banks used them in their long-term incentives.

|

|

Financial measures for annual incentives |

Nonfinancial measures for annual incentives |

Financial measures for long-term incentives |

Nonfinancial measures for long-term incentives |

Financial and nonfinancial measures related to risk |

|

Failed banks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

First Republic Bank, 2021a |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Signature Bank, 2022 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Silicon Valley Bank, 2022 |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Selected peer banks (seven) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of peer banks with the specified measure, 2022 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

2 |

6 |

Source: GAO analysis of 2023 proxy statements (Silicon Valley, Signature, and other selected banks) and 2022 proxy statement (First Republic). | GAO‑25‑107032

Note: Our analysis compared the incentive plans for executive officers of First Republic Bank, Signature Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank to a group of seven U.S.-based banks with similar business lines that each had total assets of $100 billion–$250 billion at year-end 2022.

aFirst Republic Bank’s 2022 information was not publicly available because the bank did not release its 2023 proxy statement or publicly disclose its 2022 executive compensation prior to its failure on May 1, 2023.

In 2022, the types of financial measures the banks used were similar. For example, all the banks used a measure of return on equity for long-term incentive awards and six banks used it for annual incentive awards. That is, if the bank met a stated goal for return on equity, the executive received the portion of the incentive award determined by this measure. Other common financial measures among the banks we reviewed were total shareholder return, return on assets, and earnings per share.[35] Industry group representatives told us that banks generally use similar financial performance measures and that none of these measures are particularly risky when used together with other performance measures.

Eight of the banks also used nonfinancial measures in either long-term incentives or annual incentives, or both. These nonfinancial measures often included an assessment of risk management. For example, 34 percent of Signature Bank’s annual incentive compensation was determined by a set of nonfinancial measures, including meeting goals for prudent risk management and reputation with regulators. Examples of nonfinancial measures at other banks include meeting goals related to continuous improvement, personnel management, and reputation of the bank. Two banks, including Silicon Valley, did not use any nonfinancial measures relating to risk.[36]

Most of the 10 banks used three or fewer performance measures for designing long-term incentive awards, and they focused largely on financial measures. Two banks, including First Republic, relied on a single financial measure. Industry group representatives told us that the structuring of incentive plans can introduce risk if not balanced—for example, if annual or long-term incentive awards are tied to a single measure. In contrast, most of the 10 banks generally used a combination of more than three financial and nonfinancial measures of performance for designing annual incentive awards.

We also observed similarities in the methods banks used to design incentive awards in 2022. Eight banks, including all three failed banks, used formulas based on financial measures to determine the amount of long-term incentive awards. For example, Silicon Valley’s formula allocated 50 percent of the award for return on equity and 50 percent for total stockholder return. The two banks that did not use formulas considered performance related to nonfinancial measures as well as financial measures in the design of their long-term incentives. For example, one bank evaluated executives’ performance in leadership, strategic planning, customer relations, and management of personnel.

Three banks relied on discretionary decision-making that used financial and nonfinancial measures to determine annual incentive awards. Specifically, banks evaluated bank, business unit, and individual performance against diverse factors to ensure that no single factor disproportionately affected compensation. For example, one bank detailed a comprehensive evaluation of bank and individual performance in categories such as financial, customer, strategic, human capital, and risk. Another bank included factors such as client satisfaction, risk, and leadership executives’ performance. A third included individual efforts in advancing certain goals, such as diversity or recruitment. Industry groups told us that shareholder advisory firms prefer incentive awards based on discretionary decision-making and large banks are more likely to use them.

The literature we reviewed on the relationship between banks’ compensation packages and risks found limited evidence of a relationship between specific performance measures and bank risks.[37] One study found that a higher proportion of pay linked to return on equity was associated with lower bank risk, based on data from 2006 to 2018.[38] The same study also found no robust relationship between specific performance measures and the bank’s performance on that measure. Two studies found that relationships between executive compensation and bank risks have weakened since the 2007–2009 financial crisis.[39]

Dodd-Frank Act Provisions and Other Mechanisms Seek to Mitigate Compensation Risk and Provide Information to Shareholders

The Dodd-Frank Act requires specific corporate governance practices related to the design and review of executive compensation for all publicly traded companies.[40] These practices include shareholder votes on compensation, specific executive compensation disclosures, clawback policies, and independent compensation committees. Additionally, federal banking regulator guidance on incentive compensation describes corporate governance practices that mitigate risks related to incentive compensation, including input from risk-management personnel and independent review from the board of directors or compensation consultants.[41]

“Say-on-pay” votes. The Dodd-Frank Act requires public companies to provide their shareholders with a nonbinding advisory vote (“say-on-pay”) on the compensation of the CEO, chief financial officer, and three other highly compensated executive officers whose compensation is disclosed in the proxy statement.[42] Representatives of industry groups told us that nonbinding say-on-pay votes have allowed stockholders to directly affect compensation packages. For example, one group noted that use of certain equity instruments in executive compensation packages has declined since the Dodd-Frank Act because boards know that stockholders are less likely to approve the package.

In 2022, Silicon Valley Bank reported 89 percent approval for say-on-pay votes and Signature reported 94 percent, while six of the seven peer banks reported results of 92 percent or above. First Republic reported 92 percent in 2021.

Pay disclosures. Shareholders also have access to information on executive compensation through the disclosure of the CEO pay ratio, which is the ratio of total annual compensation for the CEO to that of the median of the annual total compensation of all employees.[43] The three failed banks reported similar or lower CEO pay ratios than any of the selected banks. For example, the CEO pay ratios of the peer banks in 2022 ranged from 111 to 1 to 158 to 1. The ratios for Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank were 83 to 1 and 79 to 1, respectively. The ratio for First Republic Bank in 2021 was 110 to 1.

Clawback policies. All the banks in our review, including the three failed banks, had a clawback policy in their annual public disclosures. These policies typically included provisions for recouping compensation in the event of a material financial restatement.[44] More than half of the banks’ policies also allowed clawback for risk-related activities, such as excessively risky behavior or violations of risk policies and procedures.[45] Federal banking regulator guidance states that boards of directors should have sufficient information to review compensation payments to determine if clawback provisions have been triggered and executed as planned, when such provisions are included in senior executive compensation arrangements.[46]

Independent compensation committees and consultants. As noted in their proxy statements, all 10 banks we reviewed, including the three failed banks, used independent compensation committees and compensation consultants to design and review executive compensation practices.[47] No executive at any of the banks was involved in designing or determining their own compensation. Members of compensation committees included independent board members. The committees met several times a year to design and review executive compensation packages. Compensation consultants were external experts engaged by the compensation committees to provide guidance and advice to the committee on compensation matters, including competitive practices, market trends, and peer group composition.

Representatives from industry groups told us that regulators and banks have placed a greater focus on the individuals involved in designing incentive compensation packages since the 2007–2009 financial crisis.

Risk reviews. In addition to required corporate governance practices, six of the selected banks, including Signature and Silicon Valley, had the chief risk officer participate in compensation design or annual reviews. Federal banking regulator guidance states that risk-management personnel should have input into the bank’s processes for designing incentive-based compensation arrangements and assessing their effectiveness in restraining imprudent risk-taking. Involving risk management personnel in the design and monitoring of incentive compensation also helps ensure that a bank’s risk-management functions are equipped to understand and address the full range of risks facing the bank.[48]

Executives at the Three Failed Banks Were Awarded and Disposed of Stock from January 2021 through March 2023

Aggregate Stock Acquisitions and Disposals

As described previously, stock awards are generally the form of payment for long-term incentive plans, which make up most of executives’ compensation at banking organizations we reviewed.[49] We examined publicly available disclosures on stock acquisitions and disposals by former executive officers at the three failed banks from January 2021, through March 2023.[50]

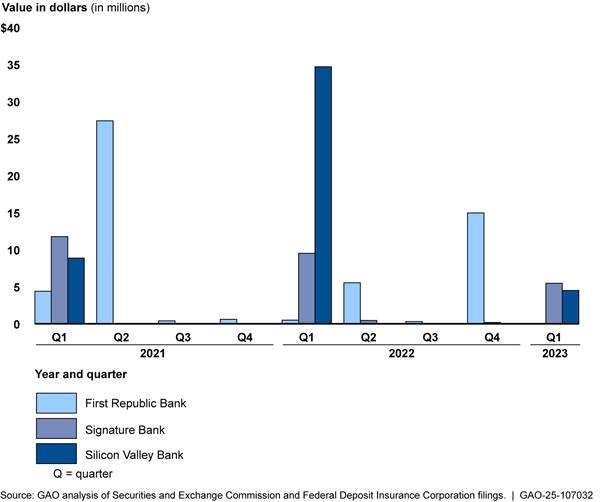

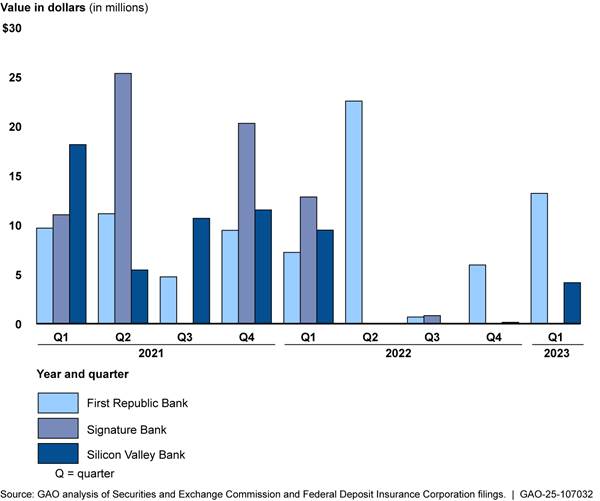

All of the former executives whose trades we reviewed at each bank received stock awards (totaling approximately $129.5 million) and made disposals during our review period, but none made open market purchases of stock. Awards were generally received in the first and second quarters of each year (see fig. 2). In 2023, executives at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank received awards of approximately $4.5 and $5.5 million, respectively. First Republic Bank historically awarded most of its incentive compensation to executives in the second or fourth quarter of the calendar year but was placed in receivership before this occurred in 2023.

Figure 2: Value of Stock Awards to Executive Officers at Three Failed Banks, January 2021–March 2023

Note: The executive officers are the named executive officers in proxy statements, generally the chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and the next three highest-paid executives at each bank.

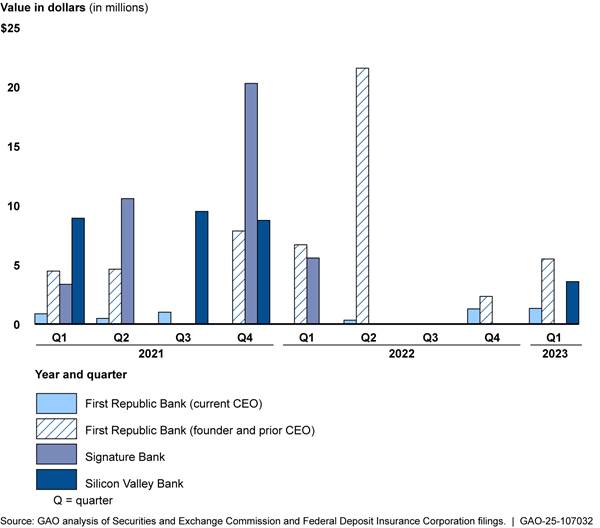

Executives at the failed banks disposed of a total of approximately $214.3 million in company stock from January 2021 through March 2023 (see fig. 3).[51] Three of the 15 former executives accounted for more than half of this amount—the CEOs of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank and the founder and former CEO of First Republic. Similar to the prior year, executives at Silicon Valley and First Republic disposed of stock in the first quarter of 2023. Executives at these two banks disposed of stocks totaling more than $17 million from January 2023 through March 2023.[52] Three of the 10 executives who disposed of stock accounted for almost three-quarters of this amount—one CEO, one former CEO, and one non-CEO executive. No executives at Signature Bank disclosed any disposals in 2023. For more details, see appendix III.

Figure 3: Value of Stock Disposals by Executive Officers at Three Failed Banks, January 2021–March 2023

Note: The executive officers are the named executive officers in proxy statements, generally the chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and the next three highest-paid executives at each bank.

Bank Chief Executive Officer Disposals

Chief executive officers at the failed banks sold a total of approximately $128.7 million in company stock from January 2021 through March 2023 (see fig. 4).[53] For more details, see appendix III.

Figure 4: Value of Stock Disposals for the Chief Executive Officers (CEO) at Three Failed Banks, January 2021–March 2023

Silicon Valley Bank. The CEO of Silicon Valley disposed of approximately $30.7 million in company stock from January 1, 2021, through February 27, 2023. The CEO disposed of approximately $3.6 million in the first quarter of 2023.[54] He owned 98,867 shares when the bank failed, which were worth approximately $22.8 million at year-end 2022.[55]

Signature Bank. The CEO of Signature Bank disposed of approximately $39.8 million in company stock from January 1, 2021, through March 22, 2022. The CEO did not dispose of any stock in the first quarter of 2023. He owned 206,448 shares when the bank failed, which were worth approximately $23.8 million at year-end 2022.

First Republic Bank. The CEO of First Republic—who was appointed in March 2022—disposed of approximately $5.3 million in company stock from January 1, 2021, through February 12, 2023. Of the $5.3 million, approximately $1.3 million was disposed of in the first quarter of 2023. The founder and prior CEO disposed of approximately $53 million from January 1, 2021, through February 28, 2023. Of the $53 million, about $5.5 million was disposed of in the first quarter of 2023. The current CEO owned 58,141 shares when the bank failed, which were worth approximately $7.1 million at year-end 2022. The founder and prior CEO owned 698,836 shares when the bank failed, which were worth approximately $85.2 million at year-end 2022.

Regulators Regularly Review Executive Compensation during Ongoing Monitoring and Occasionally Review It in Examinations

Banking Regulators Take Various Actions to Oversee Executive Compensation

Federal banking regulators review executive compensation practices during bank examinations, and this review contributes to the bank’s “management” rating.[56] The rating is based on an examiner’s assessment of the capability of the bank’s board of directors and management to identify, measure, monitor, and control the risks of a bank’s activities. A bank’s board of directors is responsible for overseeing the bank’s compensation programs. As part of their supervision of banks, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC review the activities of a bank’s board to determine if compensation practices for the bank’s executive officers and employees are safe and sound. Specifically, regulators check for consistency with prudent compensation practices and compliance with laws and regulations governing these practices.[57]

Federal banking regulators use regulations and guidance documents in their reviews of incentive or executive compensation at banking organizations. In 2014, OCC established guidelines for large banks it oversees, outlining minimum standards for designing and implementing a risk-governance framework. The guidelines also contain minimum standards for a bank’s board of directors to oversee design and implementation of the framework.[58]

With respect to compensation, the guidelines require large banks to establish and adhere to compensation programs that prohibit incentive-based payment arrangements that (1) encourage inappropriate risks by providing excessive compensation or (2) could lead to material financial loss. To determine compliance with these requirements, OCC assesses banks’ compensation practices as part of its examinations.

The Federal Reserve finalized supervisory guidance in 2021 for bank holding companies on attributes of an effective board of directors.[59] The guidance emphasizes that boards should review and approve significant policies, including those on performance management and compensation of senior management. Additionally, the 2010 interagency guidance serves as key guidance for the banking regulators when examining executive compensation. That guidance outlines three principles of incentive compensation, as described earlier.[60]

The federal banking regulators review executive compensation at large banking organizations through various supervisory activities, including ongoing monitoring, targeted examinations, and horizontal reviews.[61] Officials from the three banking regulators stated that examiners annually assess executive compensation-related materials, including board involvement, policies, and risks for large banking organizations.[62] For example, FDIC and the Federal Reserve use a management and internal control document to assess a board of directors’ involvement with compensation issues, policies governing compensation programs, and the material risks that compensation practices may pose to the bank.[63] OCC officials stated that during supervisory activities, examiners would seek to identify changes in a bank’s compensation structure or program or changes in management.

Officials from the federal banking regulators stated they may conduct other ongoing monitoring activities, depending on the risk profile or size of the banking organization. Such activities can include a review of a banking organization’s internal audits, SEC proxy statements, meeting materials from a bank’s compensation committee, news and media articles, related past supervisory concerns, and documentation of management salary and stock awards. The information gained from these activities informs regulators’ supervisory plans in multiple ways, the regulators stated. For instance, it may lead to adjustments in planned examinations of compensation-related issues, based on risks identified.

Federal banking regulators also may review executive compensation using targeted examinations, which focus on a particular banking organization product, function, topic, or risk. Regulators may conduct a targeted examination on executive compensation alone or may include it as a component in a broader targeted examination, such as corporate governance or enterprise risk management.

Officials from the three federal banking regulators stated they did not have any rules or guidance on the frequency of reviewing executive compensation through targeted examinations.[64] Instead, as part of regulators’ risk-based supervisory activities, examiners consider factors such as banking organization risk and complexity, management issues, financial condition, and internal controls (many of which are assessed as part of ongoing monitoring) to determine the frequency of such examinations.

Finally, these regulators may review executive compensation issues through horizontal reviews, which focus on a single issue at several banking organizations. As described later, the Federal Reserve has used this approach to understand the range and evolution of incentive compensation practices across banking organizations and provide guidance to them on improving these practices.[65]

Regulators Examined Incentive or Executive Compensation at Nearly All Selected Banks in 2017–2022

Compensation-Related Examinations and Reviews

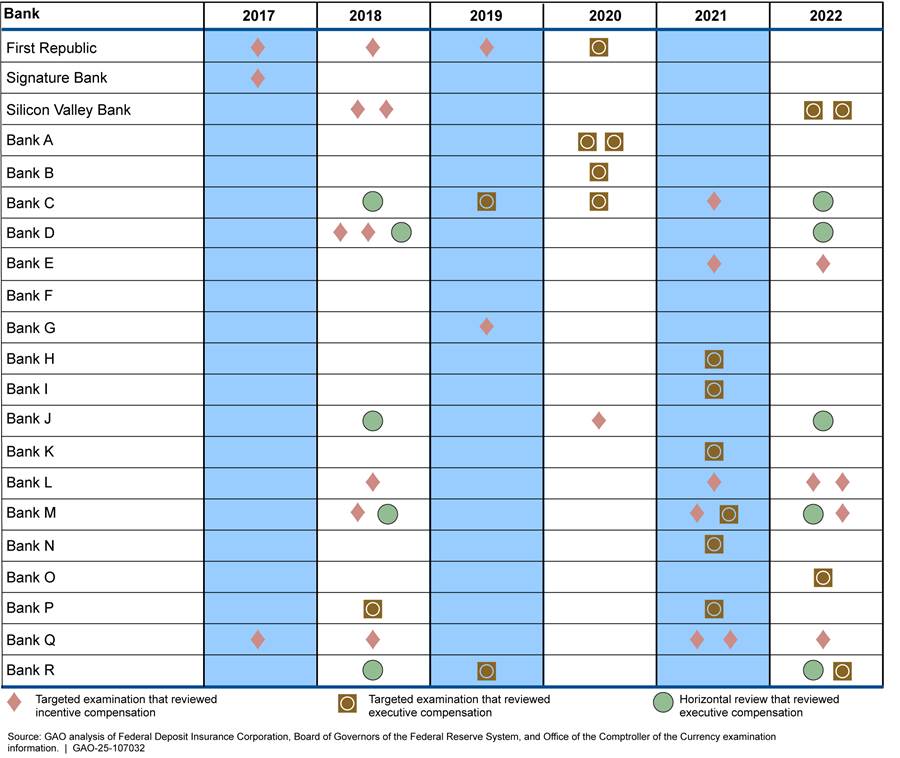

Regulators examined nearly all the 21 the banks in our selection for compensation issues at least once from 2017 through 2022.[66] As shown in figure 5, 20 of the 21 selected banks were examined at least once for executive or incentive compensation during this period.[67]

Figure 5: Targeted Examinations and Horizontal Reviews Related to Incentive and Executive Compensation for 21 Selected Banks, 2017–2022

Note: All reviews of executive compensation also included a review of incentive compensation. Because supervisory activities for the three banks that failed in 2023 have been publicly released, these banks are named in the table above. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s target reviews and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency’s focused reviews (a type of supervisory activity), are categorized as targeted examinations in this figure. With the exception of one examination of Silicon Valley Bank’s bank holding company that was made public, and horizontal reviews related to compensation, this figure does not include bank holding company examinations that were conducted by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Examinations included in the figure were conducted during calendar years 2017–2022, as determined by each targeted examination’s scoping memorandum.

During this period, 15 of the 21 selected banks received at least one examination (a targeted examination or a horizontal review) that included a review of executive compensation (results of these examinations are discussed later).[68] Thirteen of these 15 banks received at least one targeted examination (a total of 18 examinations) and the other two banks were examined as part of horizontal review activities.

Executive compensation more commonly was a component—rather than the main focus—of targeted examinations. For example, regulators considered executive compensation as part of targeted examinations focused on human resources or corporate governance. Of the 18 targeted examinations that reviewed executive compensation, four primarily reviewed executive compensation.

From 2017 through 2022, the regulators more frequently initiated targeted examinations that covered general incentive compensation practices at the 21 banks.[69] Twenty of the 21 banks had at least one targeted examination that included a review of incentive compensation.[70] In addition to examinations by their primary regulator, some banks may have undergone targeted examinations by the Federal Reserve in its capacity as a bank holding company regulator.

For the three failed banks, the frequency of examinations involving review of compensation varied:

First Republic Bank. FDIC conducted four targeted examinations of compensation issues at First Republic from 2017 through 2020. The 2020 examination included a review of executive compensation issues.

Signature Bank. FDIC did not conduct any targeted examinations that reviewed executive compensation issues from 2017 through 2022 at Signature. But FDIC conducted a targeted examination on incentive compensation issues in 2017.

Silicon Valley Bank. The Federal Reserve conducted a targeted examination of Silicon Valley in 2022 that focused on executive compensation and two targeted examinations that reviewed incentive compensation issues in 2018. Additionally, the agency conducted a targeted examination of its bank holding company that included executive compensation in 2022.

Practices, Issues, and Functions Reviewed

Targeted Examinations

Examiners at the three banking regulators reviewed multiple aspects of banks’ incentive and executive compensation practices during targeted examinations.[71] Most targeted examinations we reviewed assessed issues relating to the following areas:

· Board of Directors duties. For example, examiners reviewed whether and how banks’ boards of directors approve the compensation of bank executives. They also reviewed the activities of banks’ compensation committees, such as overseeing the design and implementation of any incentive-based compensation arrangements and working with other committees to appropriately balance risk and reward.

· Duties of nonboard functions. For example, examiners reviewed how banks’ human resources and internal audit functions designed or reviewed performance-based compensation systems.

· Effects of performance reviews on incentive compensation. For example, examiners reviewed the effectiveness of banks’ executive performance-management standards and metrics. Specifically, they examined whether the documentation or decision-making authority related to performance reviews were problematic, potentially leading to inappropriate compensation.

· Risks related to employee compensation. For example, examiners reviewed how banks’ reviewed employees’ incentive compensation plans for alignment with their risk appetite and risk-management objectives.

Areas covered by the targeted examinations of the three failed banks included the following:

· First Republic Bank. Of the four targeted examinations related to compensation for First Republic in our review period, the 2020 examination included a high-level review of the bank’s incentive compensation program, including its governance framework and financial impact. A second targeted examination reviewed incentive compensation issues related to accounts, products, and services. The last two examined the incentive compensation program as a component of corporate governance effectiveness.

· Signature Bank. The targeted examination Signature received on incentive compensation in 2017 reviewed the appropriateness of incentive compensation tied to the opening of customer accounts.

· Silicon Valley Bank. As previously discussed, Silicon Valley and its holding company were subject to targeted examinations that included executive compensation issues in 2022. These examinations reviewed aspects of the board of directors’ involvement in compensation decisions. Silicon Valley Bank also had two other targeted examinations that reviewed incentive compensation issues in 2018. These examinations reviewed the internal audit department’s reporting on incentive-based compensation arrangements, including organizational structure and risk-mitigation strategies related to loan production or volume.

Examination documentation for many of the targeted examinations we reviewed indicated that examiners referenced compensation-related guidance, such as the 2010 interagency guidance.[72] Examiners frequently referred to guidance when evaluating whether a bank’s practices were consistent with safe and sound conduct and risk-management practices. For example, one examination found the bank’s policies and programs aligned with practices described in the 2010 guidance by prohibiting incentive-compensation arrangements that encourage inappropriate risk-taking, establishing strong corporate governance on incentive compensation issues, and ensuring that compensation plans and decisions appropriately consider the level and severity of issues identified by internal audit.

Horizontal Review

In 2018, the Federal Reserve began a horizontal review at eight large banking organizations that included an examination of executive compensation practices. The review aimed to evaluate the organizations’ risk management and controls for evaluating senior management performance and awarding incentive compensation. The review also evaluated whether boards of directors (or their compensation committees) adequately used performance management and incentive compensation programs to hold senior management accountable.

In 2020, the Federal Reserve began another horizontal review of the same banking organizations, which concluded in 2023. The review found that all organizations had established performance-assessment programs for covered employees that linked some risk and control aspect to incentive compensation decisions. However, the scope and quality of these assessment programs varied significantly across the organizations, as did the type of information provided to compensation committees.

Regulators Identified Some Deficiencies in Banks’ Documentation, Monitoring, and Controls Related to Compensation

Supervisory Concerns

Banking regulators identified 10 supervisory concerns related to compensation issues at eight banking organizations, according to documentation we reviewed for targeted examinations and horizontal reviews. OCC issued five matters requiring attention to five banks in 2019, 2021, and 2022.[73] The Federal Reserve issued a matter requiring immediate attention to Silicon Valley Bank’s holding company in 2022. The Federal Reserve also issued three matters requiring immediate attention to one bank holding company and one matter requiring attention to another during its 2020 horizontal review on incentive compensation.[74]

These supervisory concerns were frequently related to aspects of employee compensation issues broadly, and not always specific to executive employees. For example, supervisory concerns were related to topics that included managing compensation-related risks, clawback policies in compensation plans, and the performance-management practices:

· One bank had clawback and forfeiture policies that were insufficient and not adequately updated.[75] OCC issued a matter requiring attention that required bank management to review related policies to discourage excessive risk-taking and reinforce the desired bank culture, as well as continue to review and approve these policies annually.

· Another bank lacked sufficient documentation to support final discretionary payout decisions for incentive plans. Existing documentation did not make it clear whether payout decision-makers had a process to consider issues and concerns identified by bank stakeholders. OCC’s related matter requiring attention required the bank to develop and implement revised monitoring and validation processes that ensured appropriate consideration of these issues.

· A matter requiring immediate attention that the Federal Reserve issued against Silicon Valley Bank’s holding company in 2022 stated that the board did not hold senior management accountable through appropriate performance management practices. Specifically, senior management’s performance objectives and incentive compensation practices did not clearly link to risk-management objectives. Further, the holding company did not adequately consider the impact of risk-management deficiencies on its incentive compensation program. The matter required the holding company to develop a plan to effectively oversee senior management. At the time of Silicon Valley Bank’s failure, it was in the process of redesigning its incentive compensation program in response to this supervisory concern.[76]

Although they did not rise to the level of a supervisory concern, the regulators also noted additional concerns related to executive compensation issues. Of the 18 targeted examinations that included review of executive compensation, 11 noted the need for improvement related to the banks’ incentive or executive compensation practices.[77] For example, one examination noted that clawback procedures were used inconsistently in the bank’s executive agreements. Other examinations noted that banks did not sufficiently document incentive compensation procedures and that incentive compensation payment processes needed more internal oversight and stronger controls.

Enforcement Actions

For the 21 banks we selected, only OCC took enforcement actions related to compensation practices from 2017 through 2022. In 2020, OCC initiated several formal enforcement actions against senior bank employees involved with overseeing incentive compensation at Wells Fargo.[78]

These actions were related to, among other things, the officer’s role in overseeing Wells Fargo’s incentive compensation plans for branch personnel, which were based on unreasonable sales goals. These goals led employees to open accounts for customers without their knowledge or consent. The enforcement actions sought or required the senior bank official to pay a civil monetary penalty (in one case, resolved in 2023, as high as $17 million). The actions also prohibited these officials from participating in the banking industry or imposed limitations on their activities.

Agencies Have Not Finalized Rulemaking on Incentive Compensation and Differ on Approaches

Agencies Jointly Proposed a Rule on Incentive Compensation Multiple Times but Have Not Finalized One

The six agencies charged with issuing regulations or guidelines on incentive compensation have taken steps to address Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act but as of January 2025 had not issued a final rule or guidelines.[79] The statutory deadline for implementing Section 956 was April 21, 2011.[80] To date, these agencies—FDIC, Federal Reserve, FHFA, NCUA, OCC, and SEC—included their plans for the rule in their semiannual rulemaking agendas, established an interagency working group, and considered or published multiple rule proposals (see fig. 6). In addition, since 2011, FHFA, NCUA, and SEC individually adopted their own rules related to enhanced executive compensation disclosures or the regulation of compensation at financial institutions.[81]

Note: The six agencies required by Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) to jointly prescribe regulations or guidelines are the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and Securities and Exchange Commission.

Unified Agenda. Since 2011, all six agencies have consistently cited Section 956 rulemaking in their submissions to the Unified Agenda of Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions, which provides information on regulations under development or review twice a year.[82] From fall 2011 through spring 2024, the six agencies periodically shifted the rulemaking between the active actions and long-term actions on their agendas.[83] As of the spring 2024 agenda, published in July 2024, FDIC, NCUA, OCC, and SEC listed the rulemaking as one on which they expect to take action within the next 12 months and the Federal Reserve and FHFA listed it as a long-term action.[84]

Working group. In 2010, the agencies formed an interagency working group (consisting of staff from each agency) to support the joint rulemaking effort, according to agency officials. Officials said the group generally meets monthly, but frequency may increase to weekly when working on a new proposal. Officials said the working group facilitates information sharing among agencies, including supervisory experiences related to incentive compensation, economic analyses results, and summaries of public comments on proposed rules.

According to officials, one agency generally has taken the lead in drafting versions of the proposed rules, sharing drafts with other agencies, and proposing timelines for review and input. Staff from other agencies provide written comments or discuss them orally during meetings. Each agency participates equally in rulemaking efforts, according to officials from all six agencies.

Agency officials said they also engage in internal rulemaking review efforts. They elevate draft rule proposals and certain working group discussions to agency leadership and escalate unresolved issues to agency principals for final decisions.

2011 proposed rulemaking. In April 2011, the six agencies published a proposed rule for public comment.[85] The proposed rule was principles-based—that is, focused on general principles and objectives rather than detailed, prescriptive requirements. It would have required covered financial institutions to adhere to three key principles outlined in the 2010 interagency guidance on sound incentive compensation policies.[86] Additionally, the institutions would have been required to establish policies and procedures to ensure compliance. The proposal included additional requirements for larger financial institutions, including deferring at least 50 percent of executive officers’ incentive compensation over a minimum of 3 years.[87]

The six agencies received over 10,000 public comments in response to the 2011 proposed rule. According to the agencies, most were identical comment letters of two types. The first type urged the agencies to implement requirements that would minimize incentives for short-term risk-taking by executives. The second type suggested various methods to improve incentive compensation practices, such as linking incentive compensation to measures of a financial institution’s safety and stability. Other commenters urged the agencies to strengthen the proposal or expressed disagreement with specific aspects. For instance, some disagreed with the proposed requirement to defer incentive compensation, arguing it could undermine a firm’s ability to attract and retain key employees.

2016 proposed rulemaking. In June 2016, the six agencies published another proposed rulemaking for public comment.[88] The 2016 proposed rule was similar to the 2011 proposal in prohibiting incentive-based compensation arrangements that did not meet the three key principles in the 2010 interagency guidance. However, rather than being mainly a principles-based rule, it specified various requirements for covered financial institutions. These included specific factors for determining whether such arrangements appropriately balanced risk and reward, a key principle in the 2010 guidance. The arrangements would have been required to (1) include financial and nonfinancial measures of performance; (2) allow nonfinancial measures to override financial measures, when appropriate; and (3) be subject to adjustment to reflect actual losses, inappropriate risks taken, compliance deficiencies, or other measures of performance.

The 2016 proposed rule grouped covered institutions into three size categories, compared to two in the 2011 proposed rule.[89] It also applied more rigorous requirements to larger institutions. For example, the largest institutions would have had to defer at least 60 percent of a senior executive’s incentive compensation for at least 4 years. Institutions in the next largest category would be required to defer at least 50 percent of a senior executive’s incentive compensation for at least 3 years.[90] Certain employees in the largest two categories also would have been subject to clawback provisions.[91]

The agencies received over 100 public comments in response to the 2016 proposed rule. The preamble to the 2024 proposal indicated that many commenters expressed concerns about the overall proposal and many recommended strengthening it. For example, some commenters suggested adopting the 2010 interagency guidance or a similar principles-based approach. Commenters also opposed specific aspects of the proposed rule—for example, believing the incentive compensation deferral requirement was too complicated. Some urged that the rule establish stricter deferral requirements and longer deferral periods.

2019 drafting of proposed rule. According to agency officials and statements made by OCC’s Comptroller, the six agencies drafted and circulated among the agencies another version of a proposed rule in 2019, but it was never issued for public comment.[92] Officials from one agency and OCC’s Comptroller generally described this proposal as principles-based. The officials stated that the proposal was aimed at achieving broad consensus among the agencies.

2024 proposal for public comment. Four of the six agencies (FDIC, FHFA, NCUA, and OCC) released an informal notice of proposed rulemaking between May and July 2024 and have been accepting public comments on their websites.[93] As of January 2025, this proposal had not been published in the Federal Register because not all six agencies had taken action to approve the May 2024 version.[94] The Federal Reserve has not taken action on this proposal, with officials stating that it should be updated to reflect current banking conditions and developments related to incentive compensation practices since 2016. They stated they plan to conduct additional analysis to better understand these issues. Additionally, SEC has not taken action to approve a proposal. In a September 2024 hearing, the Chair of SEC stated that SEC has collaborated with the other five agencies on the rulemaking, but that it can only propose a rule if it is a joint rulemaking.[95]

The 2024 proposal used the same regulatory text as the 2016 proposed rule, but it added numerous questions seeking public comment on alternative provisions. For example, the agencies requested feedback on alternative asset thresholds for covered institutions, simplifying the structure from three levels to two by treating banks with assets over $50 billion and those over $250 billion similarly.[96] In addition, the proposal seeks comments on revising requirements and prohibitions for certain large institutions, such as how long a clawback provision should be in place.

Differing Views on Regulatory Approaches Impede Joint Rulemaking on Incentive-Based Compensation Arrangements

Agency leaders hold differing views on regulating incentive-based compensation arrangements, posing a challenge to finalizing a rule. The 2011 proposal adopted a principles-based approach, whereas the 2016 proposal had more specific and stringent requirements. The 2024 proposal largely mirrored the 2016 proposal but solicited public comments on key provisions, such as clawbacks.

Agency leaders have publicly stated preferences for one or the other of these approaches, most recently when four of the agencies released a proposal in May 2024:

FDIC. Public statements made by the FDIC Chair and Vice Chair in May 2024 indicate differing opinions on regulatory approaches to the rule. The Chair supports the regulatory requirements in the 2016 proposal, while the Vice Chair does not.[97] Instead, the Vice Chair supports the principles-based approach in the 2010 interagency guidance on incentive compensation, which was the basis of the 2011 proposed rule.[98] He added that implementation of the 2010 guidance, along with other supervisory efforts at the time, contributed to meaningful changes in incentive compensation practices at financial institutions.

Federal Reserve. As noted earlier, the Federal Reserve did not join the 2024 proposal issued by FDIC, FHFA, NCUA, and OCC. In May 2024, the Vice Chair for Supervision publicly stated that the Federal Reserve would be conducting further analysis before doing so.[99] Additionally, in congressional testimony in both 2015 and 2018, the then Federal Reserve Chairs stated that although the rulemaking had not been finalized, the approach in the 2010 interagency guidance and ongoing supervision had served to limit incentive-based compensation arrangements that encouraged inappropriate risk-taking.[100]

SEC. SEC did not join in issuing the 2024 proposal, as noted earlier. In June 2024, an SEC Commissioner stated that Section 956 was an important provision, and that “while supervising financial institutions and conducting exams are essential, it helps to have clear bright-line rules, and not just principles-based concepts.”[101]

NCUA. The NCUA board voted to adopt the 2024 proposal in July 2024, as previously discussed. However, the NCUA Vice Chairman, one of the three voting members of the NCUA Board, voted against the proposal and publicly stated that he did not support the proposal. He commented that the proposal went beyond the congressional intent of the mandate. He also cited the FDIC Vice Chairman’s statement supporting the principles-based approach in the 2010 interagency guidance.[102]

Officials from all six agencies said that differences in statutory authorities and the types of entities they regulate posed challenges to progressing on the rulemaking. FDIC officials noted the diverse range of covered financial institutions under Section 956, including depository institutions, bank holding companies, broker-dealers, credit unions, investment advisers, and government-sponsored enterprises. SEC officials stated that some of the agencies historically have regulated these entities differently, making it challenging to develop a joint rule. Federal Reserve officials noted that the complexity of compensation structures across bank holding companies also has posed a challenge for this rulemaking. Some companies set compensation at the holding company level, while others do so at the subsidiary level, which can involve different regulators. However, officials from most of the agencies noted that such challenges are common in interagency rulemakings and they regularly work through them.

As discussed earlier, supervisory concerns and enforcement actions indicate ongoing issues with the incentive compensation practices at some large financial institutions. By jointly prescribing regulations or guidelines to implement Section 956, the agencies would help prevent excessive compensation arrangements at these institutions that encourage inappropriate risks and could threaten their safety and soundness.

Conclusions

Incentive-based compensation arrangements can serve as critical tools for financial institutions to attract and retain skilled executives and promote better performance. However, these arrangements can also incentivize inappropriate risk-taking. To address this risk, Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act directed the Federal Reserve, FDIC, FHFA, NCUA, OCC, and SEC to jointly develop regulations or guidelines prohibiting incentive-based compensation arrangements that could lead to material financial loss.

While the act required the regulations or guidelines to be issued by April 21, 2011, more than 13 years have passed without finalized regulations. Instead, the agencies have employed other strategies, such as interagency guidance and supervision. However, the numerous supervisory concerns identified related to incentive compensation underscore the need for the agencies to reconcile differences in their regulatory preferences. By finalizing regulations or guidelines, the agencies would ensure compliance with Section 956, and better prevent compensation practices that can undermine the safety and soundness of large financial institutions.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of six recommendations, one each to the Federal Reserve, FDIC, FHFA, NCUA, OCC, and SEC:

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System should jointly prescribe regulations or guidelines with the five other agencies that are directed to implement Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act, as soon as practicable. (Recommendation 1)

The Board of Directors of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation should jointly prescribe regulations or guidelines with the five other agencies that are directed to implement Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act, as soon as practicable. (Recommendation 2)

The Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency should jointly prescribe regulations or guidelines with the five other agencies that are directed to implement Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act, as soon as practicable. (Recommendation 3)

The Board of Directors of the National Credit Union Administration should jointly prescribe regulations or guidelines with the five other agencies that are directed to implement Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act, as soon as practicable. (Recommendation 4)

The Comptroller of the Currency should jointly prescribe regulations or guidelines with the five other agencies that are directed to implement Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act, as soon as practicable. (Recommendation 5)

The Securities and Exchange Commission should jointly prescribe regulations or guidelines with the five other agencies that are directed to implement Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act, as soon as practicable. (Recommendation 6)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Federal Reserve, FDIC, FHFA, NCUA, OCC, and SEC for review and comment. All the agencies provided written comments that are reprinted in appendixes IV–IX. In their comments, each agency agreed with the recommendation addressed to it and stated its commitment to continue working with the other agencies to implement Section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Act. The Federal Reserve added that further work on this issue should be based on updated analysis to reflect current banking conditions and practices, which it has been focused on conducting. The Federal Reserve, FDIC, FHFA, and SEC also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committee, the Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Acting Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Acting Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, Chairman of the National Credit Union Administration, Acting Comptroller of the Currency, Acting Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.