UKRAINE

State Should Take Additional Actions to Improve Planning for Any Future Recovery Assistance

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Latesha Love-Grayer at lovegrayerl@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Following Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion, donors of recovery assistance, including the U.S., aimed to help Ukraine build a strong economy and stable democracy on a path to European Union membership. As of December 2024, donors reported having collectively committed more than $130 billion in loans and grants for these objectives. Donors linked their assistance to Ukraine’s implementation of reforms, such as governance for state-owned enterprises.

From February 2022 through December 2024, the Department of State successfully facilitated interagency collaboration as it led early recovery planning for Ukraine but did not fully develop ways to measure progress toward U.S. goals or estimate costs for its assistance strategy. The strategy does not contain indicators for measuring progress toward strategic goals, though State officials said they intended to develop them. In addition, State had not determined the funding resources needed to achieve these goals. Doing so would give the U.S. information it needs to make the most effective use of any future recovery assistance it provides to Ukraine.

Through December 2024, donors and the government of Ukraine (GoU) used a coordination mechanism called the Ukraine Donor Platform to support collaborative decisions and generate support for key recovery initiatives. These initiatives included financing and technical assistance to enhance Ukraine’s ability to prepare and implement recovery projects. Donors cited U.S. leadership during this period as critical for coordination and advancing initiatives.

Ukrainian entities have been building a system for managing public projects and implementing reforms designed to strengthen institutions and spur economic growth, in support of recovery. However, effects of the war, such as population displacement, and continuing corruption risks may interfere with their efforts to manage recovery in an accountable and transparent manner.

Municipalities Present Recovery Projects at the 2024 Ukraine Recovery Conference

Why GAO Did This Study

Ukraine, with support from the U.S. and other donors, has taken early steps toward recovery, despite the ongoing conflict. The World Bank estimated recovery could cost nearly $524 billion over 10 years. The U.S. reported committing more than $56 billion for Ukraine’s recovery from 2022 through 2024. However, the U.S. has paused some assistance amid changes to its foreign assistance priorities.

GAO was asked to evaluate U.S. planning for assisting Ukraine’s recovery. This report examines, from February 2022 through December 2024, (1) U.S. and other donor goals for Ukraine’s recovery, (2) the extent to which U.S. government strategic planning and interagency collaboration for Ukraine’s early recovery incorporated best practices, (3) mechanisms for coordination among donors and the GoU, and (4) Ukrainian efforts to improve transparency and accountability, supporting recovery.

GAO reviewed documents and interviewed officials from State and other federal agencies, the GoU, and other donors. GAO also conducted a site visit to Kyiv, Ukraine.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to State to determine, for any ongoing and future Ukraine recovery assistance, estimated costs and ways to measure progress in achieving U.S. strategic goals. State agreed with both recommendations

Abbreviations

ARMA Asset Recovery Management Agency

EU European Union

EUR/ACE Office of the Coordinator of U.S. Assistance for Europe and Eurasia

G7 Group of Seven

GoU government of Ukraine

HACC High Anti-Corruption Court

IMF International Monetary Fund

MEASURE Monitoring,

Evaluation and Audit Services for Ukraine

Reporting

NABU National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine

NACP National Agency for Corruption Prevention

SAPO Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office

UN United Nations

USAID U.S. Agency for International Development

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 4, 2025

The Honorable James E. Risch

Chairman

Committee on Foreign Relations

United States Senate

The Honorable Brian J. Mast

Chairman

Committee on Foreign Affairs

House of Representatives

The Honorable Michael McCaul

House of Representatives

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has had devastating consequences, creating a humanitarian crisis in Europe and threatening the sovereignty of a democratic country. It has also damaged infrastructure and disrupted Ukraine’s economy. As of December 31, 2024, the World Bank and other entities estimated the cost of Ukraine’s total recovery needs at almost $524 billion over the next 10 years.[1]

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion, Congress appropriated more than $174 billion in supplemental funding across the federal government to respond to the situation in Ukraine.[2] Some of this funding, as well as funding appropriated under other acts, was allocated to the Department of State, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and other U.S. government agencies for programs to support Ukraine’s continued economic stability and early recovery amid the ongoing conflict. We use the term “early recovery assistance” to refer to all non-security foreign assistance that the U.S. and other donors have provided to Ukraine to help it repair damage, address societal impacts brought on by the war, sustain critical government services, develop its economy and infrastructure, reform its institutions to enhance democracy and rule of law, and pursue Euro-Atlantic integration. The United Nations (UN) recommends that early recovery assistance begin before a conflict ends.[3]

This report is part of a series of GAO reports that both describe and evaluate U.S. agencies’ use of the funds appropriated in response to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Among other topics, we have previously reported on State’s and USAID’s use of implementing partners for non-security assistance in response to the invasion of Ukraine.[4] We also previously described the existing oversight of U.S. direct budget support, including the scopes and limitations of these oversight approaches.[5] In April 2024, we issued a Snapshot report that describes lessons from past recovery efforts that could help inform U.S. recovery assistance in Ukraine.[6] The Snapshot cites planning, coordination, political will, and accountability mechanisms as increasing the likelihood of sustainable results.[7]

You asked us to review U.S. recovery assistance to Ukraine, including ongoing early recovery and any planned future recovery assistance. This review examines, for the period from February 2022 through December 2024, (1) U.S. and other donor goals for recovery assistance to Ukraine, (2) the extent to which the U.S. government’s strategic planning and interagency collaboration for Ukraine’s early recovery incorporated best practices, (3) mechanisms for coordination among donors and the government of Ukraine (GoU), and (4) Ukrainian efforts to improve transparency and accountability, supporting recovery.

To address these objectives, we reviewed documents from State, USAID, the European Union (EU), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, among other donors, and from Ukrainian government ministries and Ukrainian civil society groups. We analyzed data on donor commitments reported to the Ukraine Donor Platform. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for describing the level of U.S. early recovery financial commitments as well as commitments provided across all donors. We also interviewed officials from State; USAID; the Departments of the Treasury, Commerce, Energy, and Transportation; the Export-Import Bank of the United States; and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, regarding planning and coordination.

To evaluate strategic planning, we compared State’s planning with the nine key elements and standards for strategy documents outlined in State’s Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM) as well as relevant lessons from our review of recovery assistance lessons from other conflicts.[8] State’s planning included the Ukraine Assistance Strategy, State’s interagency assistance strategy for Ukraine’s recovery.[9] To evaluate interagency collaboration, we determined the extent to which State’s Office of the Coordinator of U.S. Assistance for Europe and Eurasia (EUR/ACE) had demonstrated each collaboration practice in our leading practices to enhance interagency collaboration.[10]

To gather information on early recovery efforts and donor coordination mechanisms, we attended the June 2024 Ukraine Recovery Conference in Berlin, Germany, and traveled to Kyiv, Ukraine in September 2024. We met with Ukrainian government and civil society officials, as well as U.S. government officials at U.S. Embassy Kyiv, to discuss early recovery and coordination with the international community. We selected nine other major donors—the permanent members of the Ukraine Donor Platform Steering Committee and the two financial institutions that provided secondees to the Ukraine Donor Platform—and met with them in person in Kyiv and virtually in Brussels, London, Luxembourg City, and Warsaw regarding coordination mechanisms and successes and challenges.[11] We also met virtually with officials from the Ukraine Donor Platform Secretariat. For more detailed information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

This report focuses on early recovery assistance provided to Ukraine from February 2022 through December 2024. A January 20, 2025, executive order stated that department and agency heads with responsibility for U.S. foreign development assistance programs shall immediately pause new obligations and disbursements of development assistance funds to foreign countries and implementing non-governmental organizations, international organizations, and contractors pending reviews of such programs for programmatic efficiency and consistency with U.S. foreign policy.[12] This pause included early recovery assistance to Ukraine. In March 2025, USAID and State notified Congress of their intent to undertake a reorganization of foreign assistance programming that would involve separating almost all USAID personnel from federal service, realigning certain USAID functions to State by July 1, 2025, and discontinuing the remaining USAID functions. As of August 2025, some assistance activities were in the process of being closed out and some activities had resumed, according to State officials. Those officials also told us they were prepared to revise State’s Ukraine Assistance Strategy when they receive guidance from State leadership.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2023 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Key Economic and Political Developments in Ukraine

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Ukraine began moving from a command economy—one in which means of production were publicly owned and economic activity was controlled by a central authority—toward a market-based system. The country also began establishing a more democratic government. Ukraine’s location between Russia, which did not fully accept Ukrainian independence, and the EU, which viewed Ukraine as an important part of Europe, heightened the geopolitical significance of events in the country.

Several key economic and political events in Ukraine are described below, illustrating the country’s efforts to reform its economy and government and align itself with Europe amid Russia’s acts of aggression.

· Orange Revolution (2004). In 2004, Russia-backed candidate Viktor Yanukovych was declared President of Ukraine amid allegations of electoral fraud, which led to widespread protests and a re-vote. This resulted in the election of Viktor Yushchenko, the opposition candidate who advocated for closer ties with the West.[13]

· Revolution of Dignity (2013–2014). Viktor Yanukovych was returned to power as President of Ukraine in 2010. During his administration, officials from the EU and the U.S. voiced concerns over human rights violations and corruption. In late 2013, Yanukovych rejected an Association Agreement with the EU, which would have resulted in greater economic alignment with Europe, in favor of closer economic ties with Russia.[14] This led to anti-government protests in Kyiv and other parts of Ukraine. As the protests continued, the government used deadly force against more than 100 protesters, shifting the focus of the protests to human rights. Ultimately, in February 2014, the government collapsed, and Yanukovych and some of his supporters fled to Russia. The Ukrainian Parliament approved a new interim government.[15] In May 2014, Ukrainians elected a new President, Petro Poroshenko, who promised to move the country closer to the West and to fight corruption.

Figure 1: Independence Square in Kyiv, Site of Protests During the Orange Revolution and the Revolution of Dignity

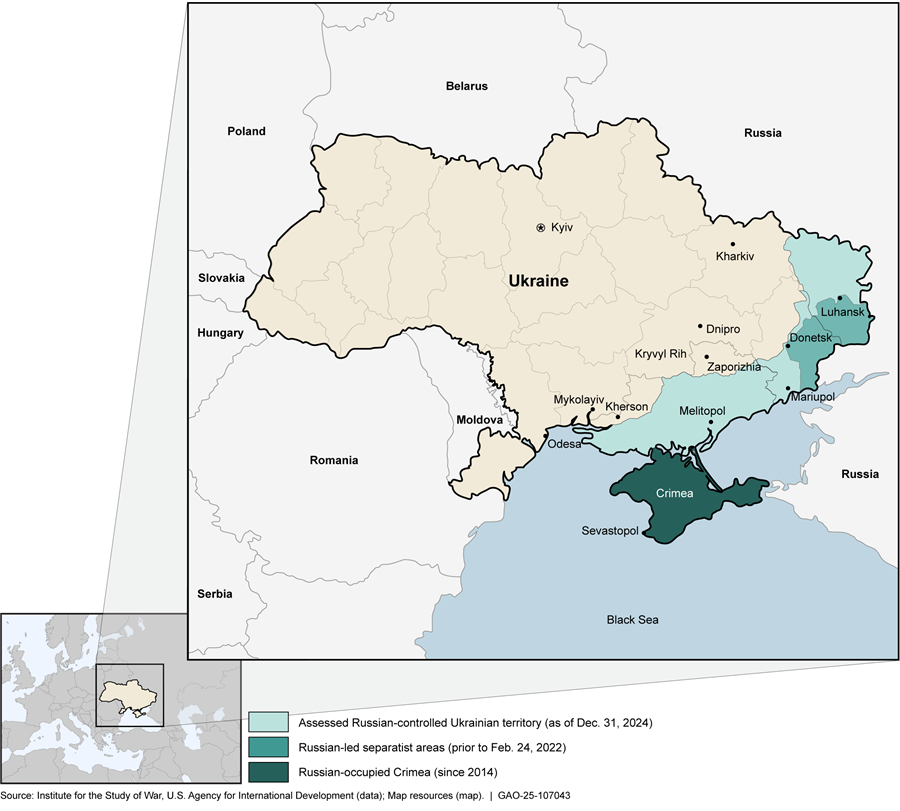

· Russia’s annexation of Crimea (2014). In February 2014, as the government of Ukraine was in crisis amid protests, Russia invaded the Crimean Peninsula, eventually announcing that it was annexing the territory. The Crimean authorities held a referendum on annexation, which the U.S., the EU, and others deemed illegal.[16] Russia signed a treaty with Crimean officials formally incorporating Crimea into Russia, and pro-Russian separatists in Eastern Ukraine began seizing government facilities and territory.[17]

· Creation of anti-corruption institutions (2015–2019). Under President Poroshenko, the GoU began implementing political, economic, and judicial reforms, as part of Ukraine’s goal of moving politically and economically closer to the EU. This included the creation of five key anti-corruption institutions designed to prevent, identify, investigate, and prosecute corruption.

· Russia’s full-scale invasion (2022). Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, with devastating consequences. As of December 2024, over 12,400 civilians in Ukraine had been killed, more than 28,000 had been injured, and millions had lost their homes.[18] An estimated 6.3 million Ukrainians had been recorded as refugees across Europe, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and an estimated 3.7 million people in Ukraine remained internally displaced as a result of the ongoing conflict.[19] Russia occupied large areas of eastern Ukraine (see fig. 2).

·

Ukraine’s EU membership application (2022). On February

28, 2022, several days after Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine applied for

EU membership. Ukraine had previously signed an association agreement with the

EU that included a free trade agreement. Ukraine was granted candidacy status

in June 2022. The EU began formal accession negotiations with Ukraine in June

2024.

Key Agencies Managing U.S. Assistance to Ukraine, 2022 Through 2024

State and USAID were the main U.S. government agencies managing U.S. foreign assistance funding for Ukraine, including early recovery assistance, following the full-scale invasion. State’s Office of the Coordinator of U.S. Assistance for Europe and Eurasia (EUR/ACE) oversaw program and policy coordination among U.S. government agencies providing foreign assistance to Ukraine and 16 other countries in the region. These responsibilities included designing foreign assistance strategies, ensuring program and policy coordination, and resolving policy and program disputes among agencies.[20] As of December 2024, the office was led by an assistance coordinator based in Washington, D.C., and was supported by an embassy-based assistance coordinator in Ukraine.

In September 2023, the President created the position of Special Representative for Ukraine’s Economic Recovery within State. The Special Representative was tasked with boosting U.S. government efforts to help strengthen Ukraine’s economy, specifically focusing on ways to improve the business climate, increase private investment, and promote economic recovery.

USAID provided early recovery assistance primarily through its Bureau for Europe and Eurasia, its USAID/Ukraine mission in Kyiv, and its Bureau for Conflict Prevention and Stabilization. Other U.S. government agencies, including the Departments of Commerce, Energy, Transportation, and the Treasury, the Development Finance Corporation, and the U.S. Export-Import Bank, were allocated foreign assistance funding for providing various types of support to Ukraine.

Establishment of the Ukraine Donor Platform by the U.S. and Other G7 Countries

In January 2023, G-7 leaders launched the Multi-Agency Donor Coordination Platform—renamed the Ukraine Donor Platform the following year—with the goal of coordinating support for Ukraine’s immediate and medium-term financing needs and future economic recovery and directing resources in a coherent, transparent, and inclusive manner. The donor platform used information generated by the Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment process, which aimed to assess the impact of the war and produce estimates of Ukraine’s early recovery and long-term reconstruction needs.[21] As of December 2024, the donor platform did not coordinate humanitarian or security assistance.

The donor platform’s Steering Committee governed on a consensus basis and was co-chaired by Ukraine, the U.S., and the EU. Other permanent Steering Committee members included Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom. The donor platform and its Steering Committee were supported by a Secretariat, which operated in Brussels and Kyiv and provided administrative assistance and coordination.

Ukrainian Government Entities and Civil Society Groups Involved in Early Recovery Efforts

A variety of Ukrainian government ministries and other entities have been involved in early recovery efforts and planning for future activities. Some of these entities existed prior to the full-scale invasion, while others, such as the Ministry for Restoration and the State Agency for Restoration, were created afterward by merging existing entities (see table 1).[22]

|

Type of entity |

Name |

Roles or Mission |

|

Ministry |

· Energy · Economy · Finance · Restorationa |

Provide energy, build an efficient economy, manage public finances and financial oversight, and supervise major recovery projects. |

|

Audit entity |

· Accounting Chamber · State Audit Serviceb |

Combat money laundering, monitor state budget funds on behalf of the parliament, and implement public financial controls. |

|

Anti-corruption entity |

· NACP · SAPO · NABU · ARMA · HACC |

Fight corruption. For example: · NACP develops anti-corruption policies. · ARMA traces assets acquired through criminal activities. · SAPO prosecutes corruption cases that NABU investigates and HACC rules on. |

|

Other government- owned or -operated entity |

· UkrEnergo · Reforms Delivery Office · Bureau of Economic Security · State Agency for Restoration and Infrastructure Development |

Perform tasks such as promoting reforms, mitigating criminal offenses affecting the economy, implementing reconstruction projects, and maintaining the energy grid. |

ARMA = Asset Recovery and Management Agency, HACC = High Anti-Corruption Court, NABU = National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine, NACP = National Agency for Corruption Prevention, SAPO = Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office

Source: GAO analysis of Ukrainian entity webpages and interview responses. | GAO‑25‑107043

aThe full name for the Ministry of Restoration is the Ministry for Development of Communities and Territories.

bThe activities of the State Audit Service are

guided and coordinated by the Cabinet of Ministers via the Ministry of Finance.

Civil society groups focused on transparency and anti-corruption have also played a role in oversight of early recovery. These groups reported working with the Ukrainian parliament to draft legislation aimed at increasing transparency and providing trainings for small and medium-sized companies on how to comply with anti-corruption measures. They have also monitored the status of this legislation, among other activities.

The U.S. and Other Donors Aimed to Help Ukraine Build a Stable Economy and Democracy by Linking Assistance to Reforms

From 2022 Through 2024, Donors’ Efforts Centered on Stabilizing Ukraine and Enabling Its Economic Growth and EU Integration

Ukraine, along with the U.S., the EU, and other donors, established broad international agreement on principles that would guide its recovery at the first Ukraine Recovery Conference in Lugano, Switzerland, in July 2022. The Lugano Principles, shown in table 2 below, emphasized donors’ intent to make Ukraine a primary participant in the recovery process and to focus assistance on the types of reforms that would contribute to the country’s progress toward EU accession.

|

Recovery principle |

Description of how the principle should guide recovery |

|

Partnership |

Led and driven by Ukraine in collaboration with international partners. Based on a sound and ongoing needs assessment process, aligned priorities, joint planning for results, accountability for financial flows, and effective coordination. |

|

Reform focus |

Must contribute to accelerating, deepening, broadening, and achieving Ukraine’s reform efforts and resilience in line with Ukraine’s European path. |

|

Transparency, accountability, and rule of law |

Must be transparent and accountable to the people of Ukraine. Must systematically strengthen rule of law and eradicate corruption. All funding for recovery needs to be fair and transparent. |

|

Democratic participation |

Must be a whole-of-society effort, rooted in democratic participation by the population, including those displaced or returning from abroad, local self-governance, and effective decentralization. |

|

Multi-stakeholder engagement |

Must facilitate collaboration between national and international actors, including from the private sector, civil society, academia, and local government. |

|

Gender equality and inclusion |

Must be inclusive and ensure gender equality and respect for human rights, including economic, social, and cultural rights. Needs to benefit all, and no part of society should be left behind. Disparities need to be reduced. |

|

Sustainability |

Must rebuild Ukraine in a sustainable manner aligned with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement, integrating social, economic, and environmental dimensions including green transition. |

Source: GAO analysis of the Lugano Declaration (2022). | GAO‑25‑107043

As the conflict continued, the U.S. and other major donors articulated slightly different goals for Ukraine depending on their roles and interests. However, these goals were largely aligned and consisted of five main aspects: a strong economy, a stable democracy, rule of law, the ability to defend itself, and integration with the EU.[23] When discussing assistance goals, donors agreed that recovery assistance related to governance, rule of law, and economic reforms would help attract the private sector investment needed for Ukraine’s longer-term recovery.

In planning documents through December 2024, the U.S. articulated that it aimed to help Ukraine become an independent, democratic, resilient, socially connected, politically stable country governed by the rule of law. The U.S. also aimed for Ukraine to be economically viable—that is, able to meet its own financing needs, economically competitive, able to attract private sector investment, and undertaking robust anti-corruption measures. Finally, the U.S. also aimed for Ukraine to be able to defend itself against aggression within internationally recognized borders and to be integrated into the Euro-Atlantic community.

The EU’s stated goals were to contribute to the recovery, reconstruction and modernization of the country and its institutions and to foster social cohesion and progressive integration into the EU, with a view to possible future EU membership.

The U.S. and Other Donors Provided Loans and Grants Linked to Ukrainian Economic and Political Reforms

The U.S. and other donors have provided recovery assistance—in the form of loans and grants—linked to Ukraine’s implementation of economic and political reforms.[24] As of December 2024, according to State, donors reported to the Ukraine Donor Platform that they had collectively committed more than $130 billion in support of Ukraine’s recovery. The majority of those commitments was direct budget support provided to the GoU to help sustain critical government services and operations following the full-scale invasion. The remainder represented economic and other development programs, including technical assistance, which were meant to increase Ukraine’s capacity, promote private sector investment, and create economic growth, among other things.[25]

Donors for Ukraine’s recovery have included the EU, the U.S., and other countries, as well as international financial institutions such as the IMF, the World Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which mobilize, manage, and disburse donor funds. Below are some of the larger examples of assistance provided for Ukraine’s recovery through the end of 2024:

· EU assistance. The EU established a 50 billion euro “Ukraine Facility” with three categories of support: about 38 billion euros in direct budget support linked to the Ukraine Plan,[26] about 7 billion euros through the Ukraine Investment Framework to mobilize investments, and approximately 5 billion euros in technical assistance and other supporting measures.

· U.S. assistance. As of December 2024, the U.S. reported committing a total of $56.8 billion since 2022 in support of Ukraine’s recovery. The U.S. committed about $6.6 billion through State, USAID and other agency programs supporting energy, governance, rule of law, civilian security, and economic reforms. These programs, which included technical assistance, were designed to improve Ukraine’s business environment and lead to greater private sector investment, among other things.[27] The U.S. provided the rest of its assistance to Ukraine through the World Bank. First, the U.S. disbursed about $30.2 billion to World Bank trust funds that provided direct budget support to Ukraine for 13 categories of public expenditures, such as government and school employee salaries.[28] Second, the U.S. provided a $20 billion loan to Ukraine through a World Bank fund, the Facilitation of Resources to Invest in Strengthening Ukraine Financial Intermediary Fund, which is part of a $50 billion loan package from G7 countries.[29] The loan is to be repaid using proceeds from immobilized Russian sovereign assets.[30]

· IMF assistance. The IMF established an extended arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility of $15.6 billion for the GoU to provide support to help secure macroeconomic and financial stability and catalyze external financing through 2027, among other things.

Donors and the GoU largely agreed that Ukraine’s recovery would require implementation of economic and political reforms, such as privatization and governance measures for state-owned enterprises and establishment of a fair system of judicial selection. To promote progress in these reforms, some donors made their assistance conditional on Ukraine taking certain actions (“conditionalities”) meant to advance the country further along its reform path. For example, the U.S. developed a Priority Reform List that formed the basis for a set of conditions linked to disbursement of its direct budget support. The conditions included implementation of personnel management and other reforms to enhance transparency and accountability at specific public institutions, according to State documents. Ukraine met the 2024 U.S. assistance conditionalities by the end of the calendar year, according to State and USAID officials.

To gain access to financial support under the Ukraine Facility, the EU required that the GoU develop the Ukraine Plan, which laid out the GoU’s reform and investment agenda (conditions), described qualitative and quantitative steps to achieve fulfilment of the conditions, and provided a timetable for implementation. The EU’s Ukraine Facility funding was linked to satisfactory fulfilment of the conditions.

The GoU created a Reforms Matrix to inventory and track the status of recommendations, required reforms, and other conditionalities associated with donor assistance and to organize the internal work of the GoU required for implementation.[31] According to donor officials and Ukraine Donor Platform Secretariat staff, as of late 2024, the remaining conditionalities that Ukraine needed to meet were largely aligned and mutually supportive in providing momentum toward bringing Ukraine closer to meeting the extensive requirements for EU membership.

State Did Not Fully Develop Ways to Measure Progress or Determine Costs for Its Assistance Strategy but Facilitated Interagency Collaboration

Within the U.S. government, State led the interagency response to address Ukraine’s early recovery needs following the full-scale invasion, spearheading development of the Ukraine Assistance Strategy and activities to implement it. State’s strategy largely addressed key elements outlined in its guidance, although it did not include milestones and performance indicators for measuring strategic progress.[32] State also did not estimate the costs or resources required to achieve the goals outlined in the strategy. However, State’s strategy and implementation activities successfully facilitated interagency collaboration on early recovery.

State’s Strategy Addressed Some Key Elements but Did Not Fully Develop Others That Would Support Recovery Planning

State’s Ukraine Assistance Strategy, which established the framework for assistance provided from January 2023 through December 2025, addressed key elements identified in State guidance, such as agencies’ roles and responsibilities, desired results, and other key elements. However, State’s EUR/ACE office did not fully develop strategy elements that would allow for (1) measuring progress toward achieving strategic goals and (2) determining the costs of fully implementing the strategy. Development of these two key elements would support strategic and budgetary planning—for any ongoing or future U.S. recovery assistance to Ukraine—by providing information that would clarify potential trade-offs and facilitate a more effective use of funding.

State’s Strategy Specified Agencies’ Roles and Desired Results, Among Other Key Elements, but Did Not Fully Develop Ways to Measure Strategic Progress

State’s guidance requires that strategies include nine key elements. We compared State’s Ukraine Assistance Strategy with these nine elements and found that the strategy generally addressed eight elements and partially addressed one (see table 3).[33]

|

Key element |

Description |

Extent to which the strategy addressed the element |

|

Agencies’ roles and responsibilities |

The strategy must include a clear description of the lead and contributing bureaus’/agencies’ roles and responsibilities |

● |

|

Interagency coordination mechanisms |

The strategy must describe how the strategy was coordinated within the department and with other departments and agencies. |

● |

|

Integration with relevant national, agency, regional, and sectoral strategies |

The strategy should be linked to appropriate higher-level strategies. |

● |

|

Expectations for lower level-strategies |

The strategy must identify expectations for lower-level strategies such as country strategies or for operational/technical plans. |

● |

|

Desired results |

Strategy must describe the end state the strategy is expected to achieve. |

● |

|

Activities to achieve results |

Strategy must describe planned steps and activities to achieve results. |

● |

|

Hierarchy of goals and subordinate objectives |

There must be a logical framework that links a strategy’s goals, objectives, and/or subordinate activities. |

● |

|

Monitoring and evaluation plans |

Strategies must include a plan to assess progress towards achieving goals and objectives, either within the actual strategy or referenced and incorporated as follow-on documents that are regularly reviewed. |

● |

|

Milestones and performance indicators |

Strategies must include, or reference, illustrative milestones and/or performance indicators, which may be derived from existing performance management plans. |

◓ |

● Generally addressed ◓Partially addressed ○ Did not address

Source: GAO analysis of State documentation and interviews. | GAO-25-107043

Note: To evaluate the extent to which U.S. government strategies include key elements, we reviewed State’s Ukraine Assistance Strategy to assess the extent to which it contains the nine key elements identified in State’s Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM). Two GAO analysts reviewed the content of the strategy to determine the extent to which it addressed the nine elements. The strategy “generally addressed” an element when it included all of its characteristics described in the FAM; “partially addressed” when it included some, but not all, of its characteristics; and “did not address” when it did not include any of its characteristics.

As of December 2024, we found that the Ukraine Assistance Strategy generally addressed these eight elements:

· Agencies’ roles and responsibilities. The strategy includes a clear description of the lead and contributing agencies that are involved in early recovery activities in support of assistance objectives. The strategy notes EUR/ACE’s leadership role, and an attachment to the strategy explains that U.S. government agencies are organized into five working groups. For example, as described in the attachment, EUR/ACE established the Energy and Cyber Working Group, with corresponding assistance sectors, and agencies such as USAID and the Department of Energy were involved in the working group’s recovery assistance activities.

· Interagency coordination mechanisms. The strategy identifies interagency coordination mechanisms, including five interagency working groups that EUR/ACE established. The working groups met, periodically, to recommend the allocation of funds to specific partners and implementing mechanisms.[34] These mechanisms could include budget support, projects, contracts, cooperative agreements, and grants. The working groups were intended to ensure that projects were consistent with the strategy, coordinated within the U.S. government and with other donor programs, and complementary.

· Integration with relevant national, agency, regional, international, and sectoral strategies. The strategy states that its development was guided by the National Security Strategy, State-USAID Joint Strategic Plan, State-USAID Joint Regional Strategy for Europe and Eurasia, and the Ukraine Integrated Country Strategy. The strategy provides examples linking its assistance objectives and lines of effort to objectives described in the National Security Strategy, such as:

· support Ukraine in defending its sovereignty and territorial integrity;

· support Ukraine with security, humanitarian, and financial assistance; and

· partner with the European Commission on a plan to reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian oil.

· Expectations for lower-level strategies. State officials said they had not created lower-level strategies, such as sectoral strategies, to support implementation of the Ukraine Assistance Strategy. Instead, officials used EUR/ACE’s interagency sectoral working group process to make decisions about which programs would get funded and with how much money. State officials have documented working group funding recommendations that provide descriptions of how programs support implementation of the strategy.

· Desired results. The strategy describes desired results which the assistance efforts seek to achieve, including an independent, democratic, politically stable, and economically viable Ukraine governed by the rule of law and integrated into the Euro-Atlantic community that can defend itself against external aggression within its internationally recognized borders.

· Activities to achieve results. The strategy describes lines of effort needed to achieve each of 13 assistance objectives. For example, under the assistance objective of enabling the GoU to provide services while at war with Russia, the strategy identifies activities such as strengthening Ukraine’s public financial management standards and supporting newly integrated areas that have been freed from Russian occupation.

· Hierarchy of goals and subordinate objectives. The strategy describes assistance objectives and lines of effort that are organized in a hierarchy around foreign policy goals. For example, under the foreign policy goal of enabling Ukraine to win the war, the strategy identifies the assistance objective of enhancing civilian security and describes a line of effort related to supporting demining and clearing of unexploded ordnance.

· Monitoring and evaluation plans. The strategy describes a two-level approach where (1) interagency partners that manage assistance to Ukraine must create project-level outcome indicators for monitoring as well as evaluation plans, and (2) the contractor implementing EUR/ACE’s Monitoring, Evaluation and Audit Services for Ukraine Reporting (MEASURE) contract will aggregate project level data to produce monitoring reports and evaluations.

As of December 2024, we found that one element was partially addressed in the Ukraine Assistance Strategy.

· Milestones and performance indicators. State reported that it was developing strategy-level indicators designed to measure progress in achieving the strategy’s objectives. For example, the most recent version of the Ukraine Assistance Strategy stated that strategy-level indicators would be attached to future strategy updates. Representatives of the contractor implementing the MEASURE contract told us that they were developing such indicators. However, as of June 2025, these indicators were still in draft form, and State officials told us they had paused further development of the indicators because of the foreign assistance review and any resulting adjustments to the Ukraine Assistance Strategy.[35] Finalizing strategy-level indicators and establishing milestones would allow State to measure progress related to the strategic goals identified in the strategy and to identify areas where progress may be lacking. Doing so would allow the U.S. to adjust its approach and make more informed decisions about allocating resources to support recovery.

State Did Not Estimate Funding Resources Needed to Achieve the Strategy’s Objectives

Our analysis of State’s Ukraine Assistance Strategy and other activities undertaken in support of strategic planning for Ukraine’s early recovery found that State had not estimated the funding resources needed to achieve its strategic goals. These goals were to support Ukraine in recovering from the war, fighting corruption, deepening rule of law, and integrating into Euro-Atlantic institutions. In our previous work on recovery assistance lessons from other conflicts, we found that U.S. assistance for recovery efforts should be guided by comprehensive strategies that, among other things, clearly define objectives and estimate costs. U.S. strategies should also indicate the funding resources needed to achieve and sustain their objectives.[36]

However, State and USAID officials in Washington, D.C., and Kyiv told us they had not undertaken any efforts to estimate funding resources required to achieve the strategic goals. EUR/ACE developed and released its strategy in 2023, updated it in the same year, and updated it again in 2024, as the conflict continued. EUR/ACE working groups met to allocate appropriated funds for partners and implementing mechanisms linked to the goals and lines of effort described in the strategy, as funds were made available. State officials noted that the Rapid Damage and Needs Assessments were a good reference for overall recovery needs They told us it would be difficult, impractical, and expensive to estimate the specific U.S. resources required to implement the Ukraine Assistance Strategy because of uncertainties regarding the war’s duration, rapidly changing conditions on the ground, and the level of other donors’ future contributions. However, agencies regularly estimate their needs in uncertain environments, including by developing scenarios for varying outcomes, and adjust those estimates when there is more certainty.

Estimating the funding resources required to achieve each of the strategic goals laid out in the strategy would enable State to project what it could achieve in Ukraine with varying amounts of funding and to communicate that information to policymakers, including Congress. This information, along with information on progress toward achieving strategic objectives, would enable State to prioritize activities to ensure the most effective use of appropriated funds.

State Facilitated Interagency Collaboration as It Led Ukraine Recovery Planning

State’s EUR/ACE office, the primary coordinator of U.S. non-security assistance for Ukraine, successfully facilitated interagency collaboration through its creation of the Ukraine Assistance Strategy and its activities to implement the strategy, such as its interagency working group process. We have previously described eight practices that can improve collaboration amongst agencies,[37] and our assessment concluded that EUR/ACE generally followed all eight practices.[38] See appendix II for our full analysis.

Steps that EUR/ACE took to facilitate collaboration included the following:

· Creation of coordination groups involving relevant interagency participants. According to the strategy and our interviews with officials from State and USAID, EUR/ACE created coordination groups at the headquarters and embassy level—for example, working groups organized around specific assistance sectors such as economic recovery or energy. EUR/ACE included relevant participants in these working groups and solicited feedback on its Ukraine assistance strategy, according to our interviews with other government agencies in Washington, D.C., and U.S. Embassy Kyiv. In another example, the U.S. Ambassador in Kyiv held quarterly assistance monitoring group meetings at which government agencies providing assistance could share information, according to State.[39]

· Creation of a data management system. EUR/ACE developed a new data management system, the Strategic Platform for Assistance Resources and Knowledge, to facilitate sharing of budget and project information. The system went online in December 2024, and at that time, the EUR/ACE Coordinator planned to grant access to other agencies so that they could manage and submit budget requests and project performance information, according to State officials.[40]

Donors and the GoU Used the Ukraine Donor Platform for Collaborative Decision-Making and Catalyzing Support for Recovery Efforts

The Ukraine Donor Platform Has Been the Primary Recovery Assistance Coordination Mechanism; Other Groups Have Played Important Roles

According to the U.S., other donors, and the GoU, through December 2024, the donor platform was the main mechanism for donors and the GoU to coordinate efforts to meet Ukraine’s early and longer-term recovery needs. Since its establishment in January 2023, the donor platform’s membership and its Secretariat staff (who are seconded from member countries and international financial institutions) have increased in size. According to the staff, the responsibilities and activities of the platform have increased as well. As of late 2024, these efforts included preparatory work for quarterly meetings of the donor platform Steering Committee; collecting, analyzing, and sharing data on donor recovery commitments; organizing briefings on donor conditionalities; and establishing a project preparation framework and corresponding funding arrangements.

With the donor platform at the center of recovery coordination, U.S., Ukrainian, and other donor officials identified several other groups as having played critical coordination roles and supporting the work of the donor platform through a multi-tiered system, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: The Ukraine Donor Platform and Other Coordination Groups for Ukraine’s Recovery, as of December 2024

Note: The Group of Seven (G7) is an informal grouping of seven of the world’s advanced economies (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the U.S.) as well as the European Union.

G7 groups. U.S. officials and other donors characterized G7 groups, such as the G7 Finance Track, as having provided significant political momentum for initiatives related to Ukraine’s recovery—including decisions regarding use of interest from frozen Russian assets to provide financial support to Ukraine. One donor told us that the group driving coordination in Kyiv was the G7 Ambassadors Support Group, which had been created following a 2015 G7 Summit to advance the reform process in Ukraine. U.S. and other donor officials emphasized the importance of the G7+ Energy Coordination Group, which mobilized billions of dollars in assistance in support of Ukraine’s energy sector.

Sector working groups. Donors and Ukrainian government officials, including those we spoke to in Kyiv, identified sector working groups as another important piece of the coordination architecture. The 18 working groups, which were revived and reconstituted in 2024 from preexisting groups, were meant to improve coordination and interaction between Ukrainian ministries and donors in Kyiv. The GoU described the working groups as the technical tier of the assistance coordination system. The objectives of the working groups were to assist in identifying and mobilizing funding and matching it with Ukrainian priority needs; supporting implementation of policy reforms and efforts to ensure transparency and accountability in recovery assistance; and facilitating discussions on assistance results, challenges, and solutions. Working groups were usually co-chaired by Ukrainian deputy ministers and one to three donor officials. The U.S. was highly involved in or co-chairing several sector working groups, including Rule of Law, Health, Transportation, Energy, and Veterans, according to State and USAID officials we met with at the embassy in Kyiv.

Business Advisory Council. The U.S.—led by the Special Representative for Ukraine’s Recovery—and Germany advocated for the creation of a Business Advisory Council to the donor platform, which was launched in summer 2024. The council, composed of private sector officials nominated by donor platform Steering Committee members, provided advice and expertise designed to promote improvements in Ukraine’s investment climate to attract private sector investment and to strengthen Ukrainian small and medium enterprises.

Heads of Cooperation. The Heads of Cooperation group was composed of senior representatives from donor countries or institutions charged with leading their respective development cooperation efforts within Ukraine. The group gathered in Kyiv on a semi-regular basis and was led by the Head of Cooperation at the EU Delegation and the UN Resident Coordinator.

Donors Identified the Ukraine Donor Platform and the U.S Leadership Role as Critical to Advancing Recovery Efforts

The donor platform, with the leadership of the U.S., successfully coordinated on recovery efforts, according to officials from donor countries and international financial institutions. The donor platform convened officials at various levels to discuss issues and make collaborative decisions related to prioritizing reforms and assistance, according to donor and Secretariat officials. It also provided a forum for the GoU to communicate its needs and priorities to donors. Additionally, the donor platform provided a mechanism for collecting and sharing information on assistance—a capability that Secretariat officials told us they were discussing ways to enhance, to more effectively utilize funding. Multiple donor officials told us that the U.S. had played a key leadership role in various parts of the coordination system.

The creation of the donor platform’s structure, including the Secretariat’s use of secondees, has strengthened coordination among donors at multiple levels, according to donor officials and Secretariat staff. For example, Secretariat staff said that co-location of officials who were seconded from their national administrations created a unique environment that allowed for direct, informal, working-level conversations conducted in the spirit of consensus. They said that this environment improved the speed and clarity of higher-level conversations between donors. Donor officials from one country noted that the donor platform was particularly helpful in enabling their government to have direct conversations with Ukraine and other major donors. The donor platform also provided a mechanism for the GoU to communicate its needs and priorities to donors and for donors to make collaborative decisions related to prioritizing reforms and assistance. For example, on different occasions, Ukrainian officials presented information on priority recovery needs and gaps.

Donors said the donor platform supported collaborative decisions and provided momentum that catalyzed recovery efforts, particularly in the following areas:

· Addressing Ukraine’s assistance absorption capacity. The donor platform Steering Committee tasked the GoU and Secretariat staff with identifying obstacles to Ukraine’s ability to effectively use, or absorb, recovery assistance and putting forward proposals for addressing the obstacles. The Secretariat’s resulting analysis identified lack of a framework for planning, prioritization and strategic allocation of resources, as well as lack of knowledge, training, incentives, or resources for project management and implementation. The GoU then produced an action plan to address these areas by reforming public investment management, and the donor platform created project preparation facilities to help build Ukraine’s technical capacity to prepare projects. Project preparation includes, among other things, the design and structuring of projects, the creation of detailed feasibility and design studies, and the performance of legal and regulatory due diligence.

· Improving Ukraine’s business climate. Donor officials, including U.S. government officials, told us that the donor platform’s Business Advisory Council had contributed to improving Ukraine’s business climate. For example, the Council provided actionable recommendations, resulting in the creation of new types of insurance, such as insurance for business travelers going in and out of Ukraine, something that had previously impeded private sector engagement.

· Using data to identify gaps and increase transparency. Donor officials noted that the donor platform’s efforts thus far to collect and analyze data from donors had provided transparency over donor funding. The Secretariat staff told us they were considering how they might expand their data analysis activities, such as by performing “deep dives” into specific economic sectors. This might allow them to provide greater insight and transparency into project-level assistance provided by donors and to identify and fill gaps in Ukrainian needs.

· Maintaining recovery momentum through annual conferences. Donor officials told us that the structure and momentum provided by the annual Ukraine Recovery Conferences and the linkage to the work of the donor platform had been important factors for advancing recovery.

Donors also highlighted the leadership role that the U.S. had played in the donor platform and in other coordination groups as an important factor in bringing the GoU and donors together and increasing the pace of critical recovery initiatives, particularly from the early phases of the war through December 2024. For example, donors highlighted U.S. leadership in the energy sector through the G7+ Ukraine Energy Coordination Group, noting that the U.S. brought high-level political support and messaging, encouraged collective support of GoU priorities, and created a good working-level structure to engage on energy issues. Another donor noted that the U.S. was instrumental in setting a fast pace for pushing for Ukraine’s reforms and in using its political capital to encourage international financial institutions to work together in a coordinated manner.

Donor and Ukrainian government officials did identify some coordination challenges. For example, donors and the GoU held differing perspectives on whether the split location of the donor platform Secretariat between Brussels and Kyiv hindered coordination. Ukrainian government officials said that locating all Secretariat staff in Kyiv would improve day-to-day coordination, and some donors, including the U.S., agreed. However, other donors told us they did not view the split location as a challenge. Moving all of the staff to Kyiv could pose security and logistical challenges given the status of the conflict. As of late 2024, the donor platform reported that it was committed to galvanizing support for an increased presence and capabilities in Kyiv, and Secretariat officials told us they had established “points of contact” to participate in the Kyiv-based sector working group meetings.

U.S. and other donor officials said that the capacity and activity levels of the sector working groups had varied since they were restarted, though it was too early to determine their effectiveness in meeting their objectives. Noting that there was constrained capacity on the GoU’s side because of the war and other factors, officials from one donor country said they had decided to build in programmatic support for the working groups they were involved in. The donor officials told us that determining how the linkages between the donor platform and the working groups would function was still a work in progress, as of the end of 2024, and that ensuring effective communication between Kyiv and Brussels would be critical for robust coordination moving forward.

Ukrainian Entities Had Been Taking Steps to Improve Transparency and Accountability but Were Facing Impediments

As of December 2024, the GoU was taking steps toward increasing transparency and accountability to support early recovery efforts. These steps included building a system for more efficient management of public investment projects and implementing reforms designed to strengthen public institutions, reduce corruption, and create conditions conducive to economic growth. Although progress was made, the GoU was facing impediments to its efforts, such as social and economic consequences of the ongoing conflict and risks of continuing corruption.

The GoU Had Been Building a System for Managing Projects and Implementing Reforms to Support Early Recovery

The GoU Had Been Building a System for More Efficient Management of Public Projects

As of December 2024, the GoU was building a system to more efficiently manage public investment projects to support recovery efforts. Public investment projects are the capital expenditures of public sector entities for the creation and restoration of fixed assets such as equipment, facilities, and other infrastructure.[41] While the GoU had begun streamlining its existing public investment management system in 2015 to bring it in line with best practices, the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022 changed the scale and nature of Ukraine’s public investment needs.[42] In addition, the government had limited financial resources to address increasing recovery needs.[43] The GoU and the IMF determined that efficient public investment management would be necessary for the country to achieve and maintain economic growth, meet the demand for public services, improve the quality of human capital, and promote even development across different regions. They also determined that Ukraine needed transparent criteria for prioritizing projects.

In 2024, the GoU created a roadmap for building a coherent, sustainable, and effective public investment management system. The GoU designed the roadmap to facilitate the planning of investment projects on the basis of strategic priorities and the medium-term budget framework, selection of projects in accordance with unified and transparent procedures and clear criteria, and implementation within the planned terms and funding. A main goal of the roadmap was the creation of a “single project pipeline”—a prioritized list of public investment projects across sectors. The roadmap also identified the main participants of the public investment management system within the GoU, including the newly created Strategic Investment Council, and defined their respective roles and responsibilities.[44] During our site visit to Kyiv in September 2024, we met with Ukrainian government officials in the building that housed key Ukrainian ministries involved in public investment management reform efforts (see fig. 4).

|

Ukraine, assisted by donors, including the U.S. government, has developed several open-source digital platforms that are being utilized for recovery efforts, among other things. These platforms include: Prozorro. Launched in 2016, Prozorro is an open-source electronic public procurement system for government agencies. Information on public contracts is accessible online for anyone to see, access, and use. Prozorro has helped save Ukraine about $6 billion since 2017, according to the 2021 U.S. Strategy on Countering Corruption.

Digital Reconstruction Ecosystem for Accountable Management (DREAM). Launched as a pilot in 2023, DREAM was developed to provide transparency over planning and implementing recovery projects. As originally envisioned, the system would track identification, preparation, appraisal, funding allocation, implementation, and completion of projects. In 2024, DREAM was formally designated as the platform for the government’s “Single Project Pipeline” of public recovery projects. Source: GAO (data); prozorro.gov.ua; Dream Brandbook (logos). | GAO-25-107043 |

The GoU linked its public investment management system with a group of IT systems, including the digital platforms Prozorro and DREAM, to provide additional transparency and accountability for projects involving public funding, including recovery efforts.

According to the GoU’s roadmap for the public investment management system, Prozorro will be mandatory for all purchases for public investment projects, and DREAM will be used as the integrated IT system for managing these projects (see fig. 5). When we met with them in Kyiv, Ministry of Finance officials told us that their intention is to leverage technology to make transparent decisions about the prioritization of recovery projects in a tight budget environment. As of December 2024, the GoU reported creating a single project pipeline consisting of 787 approved projects, of which 92 had been selected for implementation in 2025.

The GoU Had Been Implementing Reforms Linked to Donor Assistance and EU Accession

As of December 2024, the GoU had been taking steps to implement reforms linked to donor assistance and the EU accession process. These reforms were designed to strengthen public institutions, reduce corruption, and create conditions conducive to economic growth, which also supports Ukraine’s early recovery. The IMF reported in late 2024 that the GoU had gone beyond initial expectations by delivering politically difficult and comprehensive reforms. The IMF reported that the GoU needed to sustain reform momentum and ensure full implementation of the reforms that had already been nominally achieved.[45]

Ukrainian government officials had been using the Reforms Matrix as a tool to manage the reform implementation process. Ukrainian civil society groups also played a large role in advocating for reforms and monitoring their implementation. As of December 2024, some of the reforms that the GoU had been working to implement included the following:

· State Customs Service reforms: According to the IMF and the German Marshall Fund of the United States, in September 2024, the Ukrainian Parliament approved legislation to reform the State Customs Service, one of the country’s most corrupt and least trusted institutions, according to polls.[46] The IMF reported that customs reform was essential for domestic revenue mobilization.[47] The law provided for increased salaries for customs officials and a competitive selection process in which international partners will play a decisive role in vetting the head of the organization as well as determining which staff to retain, according to the German Marshall Fund of the United States. In December 2024, the GoU reported that it planned to appoint a new head of the State Customs Service by June 2025, and that future reforms would include granting customs authorities law enforcement status and centralizing customs information technology in an effort to reduce corruption risks and combat fraud.

· Economic Security Bureau of Ukraine reforms: According to the IMF, the Ukrainian Parliament passed a law in June 2024 to create mechanisms for accountability, transparency, and integrity at the Economic Security Bureau of Ukraine, a law enforcement agency tasked with investigating financial crimes such as fraud, tax evasion, and money laundering.[48] The IMF reported that the law establishes a mandate for the bureau to focus on major economic and financial crimes, establishes processes for the selection of management and staff, and strengthens the bureau’s analytical capacity to prevent crimes using a risk-based approach. These reforms are aimed at increasing revenue for the GoU and creating a more stable business environment. According to the German Marshall Fund of the United States, this reform would not have been accomplished without strong domestic ownership of the issue by Ukraine’s parliament, civil society, and business community, as well as diplomatic pressure from the IMF, the EU, and the U.S.[49] In December 2024, the GoU reported that the selection commission for the new head of the bureau had been approved and the government was on track to appoint someone to the position. The IMF reported that reform momentum needed to continue so that the new head could be appointed within agreed-upon time frames.[50]

· Tax reforms: The GoU and the Ukrainian Parliament have taken various measures to increase tax revenue, which the IMF has deemed critical for Ukraine’s economic stability. These measures include adopting a National Revenue Strategy and enacting legislation to raise personal income and corporate taxes and align fuel and tobacco excise taxes with EU directives, according to the IMF.[51] In December 2024, the GoU reported that it was developing measures to combat tax evasion and build public trust in the State Tax Service of Ukraine.

Impediments to Early Recovery Included Consequences of the War and Continuing Corruption Risks

Ukraine Was Facing Economic and Social Issues, Such as Structural Unemployment, That Affect Recovery

Although the GoU had been making progress in implementing reforms, including reforms designed to increase revenue, the ongoing war created economic conditions that could impede early recovery, according to the IMF. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine resulted in a decrease in gross domestic product and an increase in the country’s deficit. Officials representing UkrEnergo—the entity managing the energy grid—at the June 2024 Ukraine Recovery Conference in Berlin said that Ukraine had lost almost 50 percent of its energy grid to the war and regular “wear and tear.” As of December 2024, damages to the energy and extractives sector amounted to over $20 billion. The UkrEnergo officials also shared that Ukraine needed replacement transformers for the older, Soviet systems that it still relied on and was looking to the private sector to manufacture parts that fit its systems to restore damage. Additionally, Ukraine needed to increase its capacity by building more power generation plants and increase its energy resiliency by diversifying its power generation sources, according to the UkrEnergo officials.

These factors, among others, have resulted in a lack of financial resources to maintain regular government operations, repair immediate damage, and invest in recovery efforts. According to the most recent Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment mentioned earlier in this report, Ukraine’s long-term recovery over the next 10 years will require almost $524 billion. The IMF has reported that the country does not have funding to cover these costs, despite the direct budget support and other foreign assistance provided by other countries. Uncertainty about the duration of the war has worsened Ukraine’s economic outlook.[52] The IMF also identified “reform fatigue” as a high risk, noting that while tax measures and other deeper structural reforms will need to continue, these may prove challenging because of the cost to households and businesses.

The war has also had social consequences. Millions of Ukrainians have had to leave their homes—as of December 2024, approximately 6.8 million Ukrainians lived abroad as refugees and an estimated 3.7 million people remained internally displaced, including some who had been forced to move as Ukraine lost control of territory to Russia, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Mobilization, which could result in death or disability, has tightened the labor market and created more than a million veterans, who faced several vulnerabilities, according to the World Bank.

These factors have resulted in retention challenges, operational delays, and overall capacity issues, according to officials we met with in Kyiv. For example, the government’s ability to implement reforms has been hindered by high staff turnover and attrition, according to officials from the GoU’s Reforms Delivery Office. Officials from the National Agency for Corruption Prevention (NACP) said that maintaining the number of employees they need and paying their salaries had been challenging and that hiring had become more difficult because of the ongoing war. Similarly, National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) officials said that hiring qualified candidates had been a challenge.[53]

USAID had been assisting the GoU in addressing the economic impediments it faces, including structural unemployment and under-utilized segments of the labor force. Prior to the March 2025 notification of the re-alignment of certain USAID functions to State, the agency’s efforts had become more targeted to internally displaced people, veterans, youth, women, and the disabled who were unemployed for various reasons. USAID was also targeting key sectors such as small and medium enterprises and the technology sector (where there is high interest in youth employees, particularly for cyber security jobs). USAID had been working with the private sector to align the training available with businesses’ needs.

The GoU Faces Continuing Corruption Risks

Ukrainian government, civil society, and donor officials told us that funding flowing into Ukraine for recovery would increase corrupt activities because of increased procurement and other opportunities. NACP and civil society groups have identified continuing corruption risks in procurement and other areas related to recovery. For example, NACP identified inflated pricing as a continuing procurement risk, along with a lack of transparent criteria for selecting reconstruction projects and beneficiaries. According to Transparency International Ukraine, in October 2024, the GoU passed a law that requires procuring entities to publish pricing for construction materials on Prozorro, but that will not eliminate the risk of inflated pricing because contract prices are often not final. According to the group, requiring the publication of final prices would better address the issue. A Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office official added that it was difficult to weed out “bad actors.” One approach to doing so is creating a list of companies to debar from engaging in business with the state. However, according to the officials, it can be challenging to create a functional debarment list because the system enables businesses to set up a new legal entity within 2 weeks and transfer their assets there.

Another challenge to fighting corruption identified by Ukrainian government officials and civil society groups was the lack of an independent wire-tapping capability at NABU. According to NABU officials we met with in Kyiv in September 2024, if officials wanted to use wiretapping in an investigation, they had to request it through the Security Service of Ukraine, which had a monopoly on those capabilities. The officials added that there was competition for limited wire-tapping services, which could delay investigations. In addition, there was a possibility that someone within the Security Service of Ukraine would tip off the subject of the investigation. In December 2024, the GoU reported having passed a law empowering NABU to independently intercept communications. It was still working to provide resources, equipment, and technological solutions to implement the law, as of that date.

Officials from the State Audit Service told us that an additional risk to accountable recovery was no-bid contracts—closed, non-transparent procurement deals between contractors and government entities that bypass the competitive bidding process and leave room for potential corruption. According to these officials, a Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers allows, during martial law, the signing of no-bid contracts in cases of “emergency necessity,” and the list of circumstances that would qualify has expanded over time. The officials said they understand there was space for abuse and misuse under this resolution, and as an organization, the State Audit Service tries to restrict that space.

Conclusions

Even as the conflict in Ukraine continues, the GoU, the U.S. government, and other donors have begun early recovery efforts aimed at strengthening governance, encouraging economic growth, and advancing EU integration. The GoU has been building a system to manage recovery projects and continuing to implement reforms to improve transparency and accountability. Donors and the GoU have used the donor platform to share information, advance recovery initiatives, and determine reform and assistance priorities in a collaborative manner.

State’s EUR/ACE, charged with overseeing program and policy coordination for U.S. government agencies providing foreign assistance to Ukraine, has generally demonstrated key collaboration practices in its interactions with interagency partners. EUR/ACE has developed an interagency strategy to support Ukraine’s early and longer-term recovery, but the strategy, and related activities undertaken in support of strategic planning, is missing two elements. First, the strategy does not contain indicators for measuring progress toward strategic goals. State had begun developing such indicators, but State officials told us they paused this effort because of the foreign assistance review and any resulting revisions to the Ukraine Assistance Strategy. Finalizing strategy-level indicators would allow State to measure progress toward achieving any new or existing strategic goals and identify areas where progress may be lacking.

Second, State has not determined the funding resources needed to achieve the strategic goals outlined in the strategy. According to State officials, this is due to the difficulties of making such a determination amid uncertainties related to the war and other donors’ contributions. However, agencies regularly estimate their needs in uncertain environments and adjust those estimates when there is more certainty. Determining the approximate levels of resources required, and basing them on different scenarios that may arise regarding the war and other donors’ contributions, would provide valuable information. This information would help State prioritize activities, project what it could achieve in Ukraine with varying amounts of funding, and communicate that information to Congress.

The U.S. and the international community have invested billions of dollars in helping Ukraine recover from Russia’s invasion, build a strong democracy, and strengthen its economy. Looking ahead, improving State’s ability to measure strategic progress and estimate costs would better position the U.S. with the information it needs to make the most effective use of any future recovery assistance it provides to Ukraine.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to State.

The Secretary of State should, after completion of the foreign assistance review, ensure that the Office of the Coordinator of U.S. Assistance for Europe and Eurasia (EUR/ACE) finalizes strategy-level indicators to allow for assessment of progress in achieving the strategic goals identified in any revised Ukraine Assistance Strategy. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of State should, for any ongoing and future recovery assistance to Ukraine, ensure that EUR/ACE determines the estimated costs to achieve each of State’s strategic goals outlined in any revised Ukraine Assistance Strategy, basing them on different scenarios that account for changing conditions in the war and other donors’ contributions. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to State, USAID, the Departments of Commerce, Energy, Transportation, and the Treasury, the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and the Export-Import Bank of the United States for review and comment. State and the Export-Import Bank provided written comments that are reprinted in appendixes III and IV, respectively, and summarized below. State and Treasury provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. USAID; the Departments of Commerce, Transportation, and Energy; and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation did not have any comments on the report.

State concurred with both of our recommendations. With regard to recommendation 1, State noted that once the foreign assistance review concludes, it will ensure that strategy-level indicators are crafted and reviewed for its Ukraine programming. With regard to recommendation 2, State agreed that cost estimates can be valuable tools for budget planning and execution and said it will work to incorporate cost estimates for achieving individual goals and objectives into any future strategic planning for Ukraine’s recovery. State also noted that a variety of challenges may affect its ability to act on the second recommendation in the near term. These include the ongoing adjustment of State’s Ukraine recovery programming and associated goals and objectives to align with the administration’s approach to assistance to Ukraine.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution of this report until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretaries of State, Commerce, Energy, Transportation, and the Treasury, as well as the Chief Executive Officer of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, and the Chairman of the Export-Import Bank of the United States. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Latesha Love-Grayer at lovegrayerl@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made major contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Latesha Love-Grayer

Director, International Affairs and Trade

This report examines, from February 2022 through December 2024, (1) U.S. and other donor goals for recovery assistance to Ukraine, (2) the extent to which the U.S. government’s strategic planning and interagency collaboration for Ukraine’s early recovery incorporated best practices, (3) mechanisms for coordination among donors and the government of Ukraine (GoU), and (4) Ukrainian efforts to improve transparency and accountability, supporting recovery.