PRIVATE HEALTH INSURANCE

Premium Subsidy during COVID-19 Was Implemented under Tight Timeline

Report to Ranking Member, Committee on Education and the Workforce, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107055. For more information, contact John Dicken at (202) 512-7114 or dickenj@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107055, a report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Education and the Workforce, House of Representatives

Premium Subsidy during COVID-19 Was Implemented under Tight Timeline

Why GAO Did This Study

Millions of workers lost their jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic. While COBRA generally provides certain individuals with the right to maintain their employer-sponsored health coverage after certain qualifying events, not all individuals enroll due to its high cost.

GAO was asked to review the responsible federal agencies’ implementation of the COBRA subsidy. In this report, GAO describes (1) EBSA’s and IRS’s implementation of the COBRA subsidy and related challenges identified by selected stakeholders and (2) information on the utilization and effects of the COBRA subsidy.

GAO reviewed agency documents and interviewed officials on how the agencies developed guidance, disseminated information, updated systems, and ensured adherence to ARPA’s requirements. GAO reviewed aggregate data from IRS on the number and type of employers that claimed the COBRA tax credit and the amount of credits claimed. GAO conducted a literature search for studies that examined the effects of the subsidy on enrollment. GAO also interviewed external stakeholders representing employers, administrators, and employees on their experiences with the COBRA subsidy.

What GAO Found

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) was enacted on March 11, 2021, and included a temporary 100 percent subsidy toward continued health care coverage for individuals who lost their jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Employers were to offer continued coverage, free of charge, to individuals after certain qualifying events and could receive tax credits to offset the costs. To implement the subsidy, the Department of Labor’s Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA) and the Department of the Treasury’s Internal Revenue Service (IRS) used existing processes in an expedited fashion to facilitate the offer of subsidized health insurance through the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA). As part of their efforts, both agencies developed guidance for individuals and employers, educated the public, and updated internal systems under a tight timeline. The agencies released six of the eight pieces of guidance within 30 days of enactment of ARPA.

The tight timeline for implementing the COBRA subsidy resulted in challenges for employers and administrators, according to seven of eight selected employer groups and administrators GAO interviewed, with some noting challenges early in the implementation process. These challenges related to the requirement that employers and administrators send COBRA notices to eligible individuals and included uncertainty about the interpretation of the eligibility requirements and shortened timelines for sending the required COBRA notices.

More than 30,000 employers reported to IRS that their former employees utilized approximately $1.2 billion in COBRA subsidies during the pandemic. The number of individuals who received the subsidy is unknown, according to employment tax returns IRS processed as of February 2024 and agency officials. However, IRS is conducting selected audits of employment tax returns for compliance with tax credits including the COBRA subsidy. GAO’s literature review did not find any studies that examined the effects of the COBRA subsidy during the pandemic. However, two of three selected employee groups GAO interviewed said the subsidy benefited those in industries that were disproportionately affected by job loss during the pandemic, such as the entertainment industry.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AHRQ |

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

|

|

ARPA |

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 |

|

|

ARRA |

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 |

|

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

|

COBRA |

Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 |

|

|

EBSA |

Employee Benefits Security Administration |

|

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

|

NAICS |

North American Industry Classification System |

|

|

Q&A |

question and answer |

|

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 12, 2024

The Honorable Robert C. “Bobby” Scott

Ranking Member

Committee on Education and the Workforce

House of Representatives

Dear Mr. Scott:

Under provisions of the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA), eligible individuals who change or lose their jobs generally can maintain their employer-sponsored health coverage for 18 to 36 months at their own expense.[1] However, not all eligible individuals enroll in COBRA coverage due to its high costs.[2] During the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress passed the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA), which provided, from April through September 2021, a 100 percent subsidy for the premium that would otherwise be paid by certain individuals who elected COBRA coverage.[3] These individuals were not required to pay their COBRA premiums during this time period. In lieu of receiving premiums from enrolled individuals, employers were entitled to claim a tax credit equal to the amount of the subsidies they provided to eligible individuals. The COVID-19-related COBRA premium subsidy was available to help individuals who lost their jobs during the pandemic maintain their health coverage.

The Department of Labor Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA) and the Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service (IRS) were responsible for implementing the COBRA subsidy.[4] Information on the implementation of the COBRA subsidy and how it affected parties involved can help policymakers identify ways to improve such subsidies should the need for them arise in the future.

You asked us to examine how responsible federal agencies oversaw the implementation of the COVID-19-related COBRA premium subsidy, and the experiences of employers, third-party companies that administer the COBRA benefit (hereinafter referred to as administrators), and individuals with the subsidy. In this report, we describe:

1. EBSA’s and IRS’s implementation of the COVID-19-related COBRA premium subsidy provisions and related challenges identified by selected stakeholders; and

2. information on the utilization and effects of the COVID-19-related COBRA premium subsidy.

To describe how EBSA and IRS implemented the COBRA subsidy, we reviewed documentation, including EBSA and IRS guidance and manuals; EBSA education and outreach materials; and IRS’s compliance plan. We also interviewed EBSA and IRS officials to understand the agencies’ implementation process and activities related to the subsidy. This included how they developed guidance, disseminated information about the subsidy to the public, updated internal systems, and ensured adherence to ARPA’s requirements.

We also interviewed a nongeneralizable selection of eight external stakeholders representing employers (five groups) and administrators (three administrators) about their experiences implementing the subsidy and any challenges they may have faced.[5] We selected the eight external stakeholders by identifying those that represented or have as clients (1) employers in industries with historically higher COBRA eligibility rates and (2) employers that were likely to offer health coverage to their employees. In addition, we selected employer groups that represented either a large number of employers or employers with a large number of employees, as well as administrators that have a large number of employers as clients.[6] We determined that these groups met these criteria by reviewing publicly available materials about these groups as well as relevant studies on COBRA enrollment.

To describe the utilization and effects of the COBRA subsidy, we reviewed aggregate data from IRS on the number and type of employers that claimed the tax credit associated with the COBRA subsidy and the amount of credits claimed. To assess the reliability of the IRS aggregate data, we reviewed IRS documentation and interviewed agency officials about how the agency collected the data used to provide GAO with aggregate results. This included how the agency processed employment tax returns that employers used to claim the COBRA tax credit and ensured that the data are accurate and complete. We also tested the aggregate data for obvious errors or inconsistencies and interviewed agency officials to resolve any concerns. We determined that the aggregate data from IRS were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of this report.

We also conducted a literature search for studies that examined the effects of the COVID-19-related COBRA premium subsidy on COBRA enrollment. To identify relevant studies, we searched various databases, such as ABI/INFORM, EconLit, Embase, MEDLINE, SciSearch, Scopus, and WorldCat. We performed these searches to identify articles published from 2009 through 2023.[7]

In addition, we interviewed a nongeneralizable selection of three external stakeholders representing employees about their experiences with the COBRA subsidy and any challenges they may have faced.[8] We selected three external stakeholders by identifying groups that represented the interests of (1) employees in industries with historically higher COBRA eligibility rates and (2) a large group of employees. We determined that our selected stakeholder groups met the criteria by reviewing publicly available materials about these groups as well as relevant studies on COBRA enrollment.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

COBRA

In 2022, about 64 percent of individuals aged 19 to 64 in the U.S. had health insurance through an employer, according to Census Bureau estimates. COBRA provides certain individuals and their families with the right to maintain their employer-sponsored health coverage for a limited period of time if they lose their coverage due to qualifying events such as reduction in hours, job loss, death, divorce, and others. Specifically, COBRA requires health plan sponsors, including private-sector employers with at least 20 employees; employee organizations, such as labor unions; and certain state and local government employers that offer health coverage to provide individuals and their families with the option of continuing their employer-sponsored coverage after their qualifying events.[9] Employers can charge COBRA enrollees up to 102 percent of the premium to maintain their coverage. COBRA coverage generally lasts 18 months but can last 36 months for certain spouses or dependents in some circumstances, such as the policyholder’s death, divorce, or eligibility for Medicare.[10]

COBRA requires employers, including the administrators they work with, to provide individuals with (1) an initial general notice informing them of their rights under COBRA and describing the law and (2) a COBRA coverage election notice.[11]

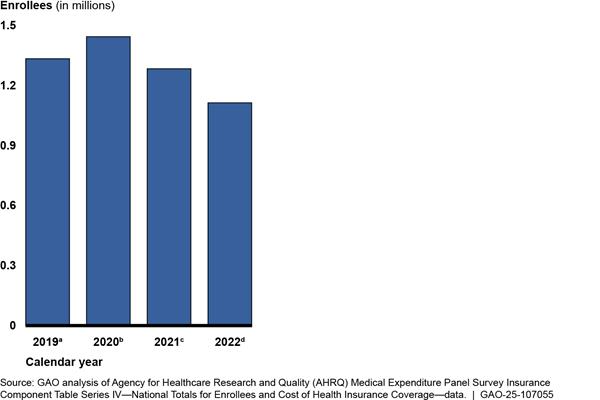

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) within the Department of Health and Human Services estimated that COBRA enrollment ranged from about 1.33 million in 2019 to about 1.11 million in 2022.[12] (See fig. 1.)

Figure 1: Estimated Total Number of Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) Enrollees, Calendar Years 2019–2022

Notes: Enrollees include former employees of private-sector and state and local government employers who are enrolled in COBRA coverage during a typical pay period in each calendar year. Enrollees also include those who worked for employers subject to COBRA or to state continuation coverage laws similar to COBRA. Excludes retirees and dependents. Estimates are rounded to the nearest ten thousand.

a2019: AHRQ’s survey estimated that there were about 1.25 million private-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 41,000 and 82,000 non-federal, public-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 7,000, for a total of about 1.33 million COBRA enrollees in 2019.

b2020: AHRQ’s survey estimated that there were about 1.37 million private-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 164,000 and 64,000 non-federal, public-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 3,000, for a total of about 1.44 million COBRA enrollees in 2020.

c2021: AHRQ’s survey estimated that there were about 1.19 million private-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 45,000 and 84,000 non-federal, public-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 6,000, for a total of about 1.28 million COBRA enrollees in 2021.

d2022: AHRQ’s survey estimated that there were about 1.03 million private-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 39,000 and 75,000 non-federal, public-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 4,000, for a total of about 1.11 million COBRA enrollees in 2022.

Within the federal government, three agencies share responsibility for administering COBRA coverage requirements. EBSA and IRS have jurisdiction over group health plans sponsored by private sector employers, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) within the Department of Health and Human Services has jurisdiction over group health plans sponsored by state and local governments.[13] Specifically, EBSA is the agency within the Department of Labor primarily responsible for ensuring that employer-sponsored group health plans comply with the COBRA coverage requirements, among others. EBSA also has issued model notices in the past for some of the COBRA notice requirements that employers, including the administrators they work with, can adapt for their use. IRS can impose excise taxes on noncompliant employers. EBSA and IRS share enforcement responsibility for COBRA’s requirements. Lastly, CMS administers the COBRA coverage laws as they apply to state and local government plans. If needed, CMS officials told us they also consult with IRS as to its interpretation of the rules.

COVID-19-Related COBRA Premium Subsidy

On March 11, 2021, ARPA was enacted to provide direct relief for the economic and health effects from the COVID-19 pandemic.[14] With millions of workers losing their jobs due to the pandemic, ARPA provided a temporary, 100 percent reduction in the premium that would otherwise be paid by eligible individuals who elected COBRA coverage. The subsidy was available for periods of coverage from April 1, 2021, through September 30, 2021, for eligible individuals who experienced a reduction in hours or involuntary termination of employment.[15] The subsidy applied to COBRA coverage that was sponsored by private-sector employers; employee organizations, such as labor unions; state and local government employers; and applicable employers in states with continuation coverage requirements similar to COBRA. Individuals were not eligible for the subsidy if they were terminated from their employment for gross misconduct or were eligible for either (1) other group health coverage through a new employer or a spouse or (2) Medicare.

In addition to regular COBRA notification requirements, ARPA required employers, including the administrators they worked with, to provide (1) an extended COBRA election notice to individuals who had qualifying events before April 1, 2021, and remained eligible for COBRA during the subsidy period, and (2) a notice of expiration of the subsidy to all individuals 15 to 45 days prior to the expiration.

ARPA also added a new penalty for IRS to administer against individuals who became ineligible for the COBRA subsidy and failed to notify their plan of their status change.

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) COBRA Premium Subsidy

|

Key Differences Between the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) Subsidy Available from 2008 through 2010 and the 2021 COBRA Subsidy · Level: the earlier subsidy covered 65 percent of the premium and the later one 100 percent. · Duration: the earlier subsidy was available for 15 months and the later one for 6 months. · Retroactivity: the earlier subsidy’s eligibility period began retroactively on Sept. 1, 2008, (5.5 months before the law was enacted) and the later one began 20 days after the law was enacted. · Coverage options: the earlier subsidy was available before states expanded their Medicaid programs or established individual marketplaces, and the later one was available when individuals may have had these additional coverage options. Source: American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Pub. L. No. 111-5, 3001, 123 Stat. 115, 455-66, as amended, and American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Pub. L. No. 117-2, 9501, 135 Stat. 4, 127-38. | GAO‑25‑107055 |

Congress provided a COBRA subsidy in 2009 as part of ARRA.[16] The ARRA subsidy covered 65 percent of the COBRA premium for certain individuals who were involuntarily terminated from their jobs between September 2008 and May 2010 for a period of up to 15 months. The ARRA subsidy differed from the COVID-19-related COBRA premium subsidy in a few key aspects, and there have been studies that examined the effects of the ARRA subsidy on COBRA enrollment.[17]

Agencies Implemented the COBRA Subsidy under a Tight Timeline; Selected Stakeholders Reported Some Challenges

EBSA and IRS Used Existing Processes to Implement the COBRA Subsidy, including Developing Guidance and Updating Systems

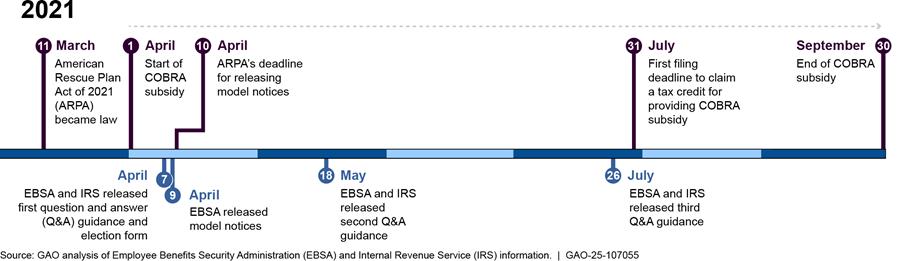

EBSA and IRS used existing processes in an expedited fashion to implement the COVID-19-related COBRA premium subsidy under a tight timeline, according to agency officials. The timing of ARPA’s enactment, just 20 days before the start of the subsidy period, contributed to the tight timeline. Recognizing the need to work quickly, both agencies expedited their implementation efforts concerning the COBRA subsidy. As part of these efforts, the agencies developed guidance for individuals and employers and released six of the eight pieces of guidance within 30 days of ARPA’s enactment. EBSA and IRS also educated the public, updated internal systems, and took steps to ensure adherence to ARPA’s requirements.

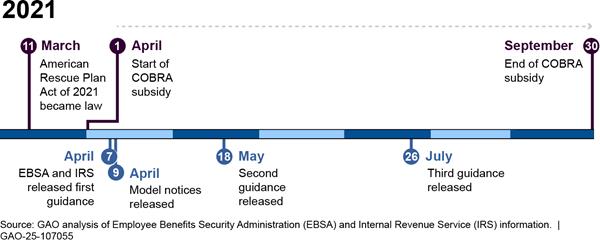

Guidance. The agencies published eight pieces of guidance over a 4.5-month period by expediting their standard processes and coordinating with each other, according to agency officials. (See fig. 2.)

Figure 2: Timeline of Selected EBSA and IRS Guidance on the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) Subsidy from March 11, 2021, through September 30, 2021

|

Emergency Relief Notices In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Departments of Labor and the Treasury issued two notices in May 2020 and February 2021 to provide relief for certain actions related to employee benefit plans, including extending (1) the 60-day initial election period for COBRA continuation coverage, (2) the date for making COBRA premium payments, and (3) the date for plans to provide a COBRA election notice. These notices minimized the possibility of individuals losing coverage because of a failure to comply with certain pre-established time frames. Source: 85 Fed. Reg. 26,351 (May 4, 2020) and the Employee Benefits Security Administration Disaster Relief Notice 2021-01. | GAO‑25‑107055 |

EBSA released four model notices and one election form for employers to use and adapt in notifying individuals of their COBRA eligibility and the availability of the subsidy during the subsidy period.[18] Specifically, EBSA announced the availability of these model notices and form on April 7, 2021, and published them on April 9, 2021. The model notices provided suggested language for employers, including the administrators they work with, to use when notifying COBRA-eligible individuals of their rights to COBRA and the subsidy.[19] EBSA also released an election form for individuals to apply for COBRA coverage with the subsidy.

In addition to the model notices and election form, EBSA and IRS released three question and answer (Q&A) style documents on April 7, May 18, and July 26, 2021, all within 4 and one-half months after ARPA became law. The guidance provided information on the eligibility and notification requirements, the application of the emergency relief notices, and the process for determining the amount of and the mechanics of filing for the COBRA tax credit.[20]

To develop guidance quickly, both agencies expedited their standard processes and coordinated with each other, according to agency officials. Both agencies began the process of determining what guidance would be needed early in the implementation process, with EBSA starting before ARPA became law and IRS starting as soon as ARPA had been enacted, according to agency officials. EBSA also reviewed prior guidance for the ARRA COBRA subsidy when drafting these Q&A documents, which helped the agency provide the public with relevant information as quickly as possible, according to agency officials.

Following the release of the April 7 guidance, the agencies also incorporated additional clarifications identified by industry stakeholders as appropriate in their later guidance, according to agency officials. For example, in addition to addressing the application of the emergency relief notices in the April 7 guidance, the agencies also included additional Q&As with examples on this topic in the May 18 guidance. The May 18 guidance also included additional clarification on the subsidy’s eligibility requirements. This was a topic about which individuals reached out to employers, including the administrators they worked with, according to three of eight selected employer groups and administrators we interviewed.

Once drafted, EBSA and IRS expedited the documents through their standard review processes, according to officials from both agencies. These processes typically involve multiple levels of reviews within the agency and reviews of portions drafted by each other. Officials explained that following the standard processes helped the agencies ensure consistency in their interpretation of the COBRA subsidy provisions within and across the agencies.

Officials from both agencies told us they also leveraged their longstanding relationship when coordinating during the drafting and review processes and concurred that the coordination generally went smoothly. EBSA officials also told us that while some inquiries from the public could not be answered early in the process because they involved IRS’s interpretation of the Internal Revenue Code, the agencies worked together to address these inquiries once IRS provided its interpretation.

Education. In addition to releasing guidance shortly following ARPA’s enactment, the agencies disseminated information about the COBRA subsidy to individuals, employers, and other interested parties through various means. EBSA and IRS provided both verbal and written information to educate the public about the subsidy’s availability, the eligibility requirements, and the process for claiming the tax credit. Doing so helped EBSA and IRS achieve their respective strategic goals of protecting benefits for workers and making it easier for taxpayers to fulfill their obligations and increasing voluntary compliance, according to agency officials.

Specifically, EBSA conducted 1,166 education and outreach events from March 11, 2021, through September 30, 2021, that reached over 17,000 people, according to agency data. Examples of these events included sessions for employers and employees dealing with the effects of layoffs and plant closures and presentations for large audiences. Meanwhile, IRS conducted a webinar and sent 43 outreach emails to small business groups through their stakeholder liaisons, according to agency officials. In addition, IRS officials told us that they shared guidance and education information using several email distribution lists, including Guidewire, Newswire, and e-News for Tax Professionals, each with at least 400,000 subscribers.

EBSA, through an external marketing firm, developed and deployed a nationwide marketing campaign focused on the COBRA subsidy, which resulted in millions of views nationally and successfully reached various target audiences. Specifically, the campaign resulted in more than 490 million views nationally from June 2021 through the completion of the campaign. In addition, the campaign exceeded each of the reach and awareness goals EBSA set out to accomplish. These goals were based on the marketing firm’s research to assess the effectiveness of the campaign against industry standards, such as click-through rates and completion of audio or video ads. (See table 1.) All three selected employee groups we interviewed told us that employees they represented were aware of the subsidy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1: Selected Digital Performance Metrics from Employee Benefits Security Administration’s (EBSA) Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) Subsidy Marketing Campaign

|

Performance metric |

Industry benchmark |

Performance |

|

Programmatic display |

0.10% |

0.17% |

|

Programmatic audio |

95% |

96% |

|

Programmatic video |

70% |

73% |

Source: EBSA document. | GAO‑25‑107055

Notes: Performance is from EBSA’s campaign during the subsidy period. Programmatic display refers to paid advertisements featured on websites, programmatic audio refers to paid advertisements featured on audio streaming services, and programmatic video refers to paid advertisements featured on video streaming services. Click-through rate is the percentage of ads a user clicked on, audio completion rate is the percentage of audio listened to 100 percent completion, and video completion rate is the percentage of videos viewed to 100 percent completion.

In addition, EBSA, through the marketing firm, deployed digital and print advertisements through various platforms such as streaming TV platforms, public billboards and posters, and social media to reach populations that were most affected by the pandemic. The firm identified these populations using nationwide data on unemployment and health coverage, according to EBSA officials. EBSA officials also told us that they launched advertisements as part of the marketing campaign before hiring the marketing firm. (See fig. 3.)

Figure 3: Example of Advertisement Used in EBSA’s Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) Subsidy Marketing Campaign During the Pandemic

EBSA further educated the public through its benefits advisors by responding to COBRA-related inquiries, which increased during the pandemic, and by resolving potential noncompliance issues, according to agency officials. Benefits advisors answered questions and helped resolve issues related to employee benefits, including COBRA coverage. Officials reported that from March 11 to December 31, 2021, EBSA benefits advisors responded to approximately 37,000 COBRA-related inquiries and said that during the peak of the subsidy period the volume of inquiries that benefits advisors addressed was three times higher than the usual volume. EBSA streamlined its hiring process to add 11 temporary benefits advisors in the summer of 2021 to help manage the increased level of inquiries from the public, according to agency officials. Officials told us they trained the temporary benefits advisors to cover more straightforward COBRA issues, which helped the agency manage the flow of inquiries from and provide information quickly to the public.

Benefits advisors also provided dispute resolution between individuals and either their employers or the group health plans these employers established to resolve disagreements over eligibility for the subsidy. EBSA established a multi-disciplinary team to help benefits advisors with particularly challenging or novel issues, officials told us, which helped to ensure consistent interpretation within the agency.

System Updates. EBSA and IRS updated their systems and policies within weeks of ARPA being enacted in order to implement the COBRA subsidy quickly. For example, EBSA updated its phone system to route COBRA-specific inquiries to designated benefits advisors to improve the agency’s ability to respond to an increased volume of inquiries, according to EBSA officials. IRS officials reported that IRS updated its internal systems for processing employment tax returns along with the related forms and instructions, which employers and others used to file for the COBRA tax credit.

Officials said they implemented these updates within weeks of ARPA’s enactment instead of the months that this process typically takes. Specifically, IRS updated its internal systems to accommodate the three new lines in the forms that the agency used to collect information related to the amount of subsidies employers provided and the number of individuals who received the subsidy, according to officials. The agency also added system checks to identify returns with incomplete information in the three new lines. In addition, IRS updated the forms and instructions associated with the employment tax return and included clarification in the Q&A documents to provide guidance on how to determine the amount of COBRA tax credit and how to claim the tax credit.

IRS’s efforts have enabled the agency to process approximately 43,000 quarterly employment tax returns with claims for the COBRA tax credit as of February 2024, according to aggregated data provided by the agency. Furthermore, IRS officials told us they expect to continue their efforts to process employment tax returns with claims for the COBRA tax credit because employers can submit amended returns with claims for the credit as late as three years after the due date of the original filing (i.e., through April 2025).[21] As of July 2024, IRS officials told us the agency had almost 1.6 million quarterly employment tax returns that had been received but not yet processed, some of which could include claims for the COBRA tax credit. IRS officials stated the agency was working through approximately 144,000 of these outstanding returns as of July 2024, and estimated being able to complete this process by the end of October 2024.[22]

Enforcement. Alongside guidance and education efforts, EBSA and IRS officials told us they worked to ensure adherence to ARPA’s requirements by reviewing potential noncompliance cases, such as those involving employers’ failure to provide COBRA notices or continuation coverage. Specifically, EBSA identified potential cases of noncompliance that the agency further investigated or referred to IRS in accordance with EBSA’s enforcement manual, according to agency officials. For example, of the six such cases that benefits advisors referred to EBSA’s Office of Enforcement, the agency investigated four of the cases but declined two because one was resolved before EBSA opened the investigation and the other involved an issue unrelated to the subsidy that contributed to the delay in extending the COBRA subsidy. As of April 2024, the COBRA subsidy issues in the other four cases had been resolved, according to EBSA officials.[23] EBSA also referred cases involving potentially eligible individuals who were denied COBRA coverage to IRS, which has authority to impose excise taxes on noncompliant employers. According to IRS officials, the agency investigated these as appropriate and did not impose penalties in any of these cases. Two of three selected employee groups we interviewed told us that individuals they represented did not experience challenges accessing the subsidy.

In addition to investigating referrals from EBSA, IRS officials told us they also planned to address noncompliance issues related to the COBRA subsidy on a post-filing basis. For tax year 2021, IRS developed a compliance plan for identifying tax credit refunds that may have been issued in error. The plan lays out the process for reviewing returns and the filters used to select the returns. IRS officials explained that, at the time it implemented the COBRA tax credit, the agency prioritized the implementation of other employer credits that involved higher dollar amounts—estimated to be more than 100 times higher. To address noncompliance issues on a post-filing basis, IRS amended its compliance plan in 2021 to include the COBRA tax credit, with the November 2021 revision being the most current plan. As of April 2024, the agency had selected for audit some returns with claims for the COBRA tax credit but had not yet completed any of these audits, according to agency officials. For the new penalty that ARPA added for individuals who became ineligible for the COBRA subsidy and failed to notify their plan of their status change, officials told us that IRS planned to rely on voluntary disclosure, informants, and discovery through post-filing audits for any information on these violations.[24]

Selected Employers and Third-Party Administrators Identified Challenges Early in the Implementation Process Due to ARPA’s Tight Timeline

The tight timeline for implementing the COBRA subsidy—due to the timing of ARPA’s enactment—resulted in challenges for employers, including the administrators they worked with, according to seven of eight selected stakeholders we interviewed, with some noting challenges early in the implementation process. Three challenges were related to employers’ obligation to send COBRA notices to eligible individuals. These challenges involved uncertainty about the interpretation of ARPA’s eligibility requirements, the application of the emergency relief notices to ARPA’s eligibility requirements, and shortened timelines for sending the required COBRA notices. Another challenge that an administrator mentioned arose from the administrator’s experience claiming the COBRA tax credit from IRS.

Uncertainty about eligibility requirements. Employers and administrators were uncertain as to how to interpret ARPA’s requirements prior to all guidance being available, particularly those requirements related to eligibility, according to six of eight selected employer groups and administrators we interviewed. These six also told us that the uncertainty led to delays in employers’ and administrators’ implementation efforts. For example, one employer group told us that until the May 18, 2021, Q&A guidance came out—about 7 weeks after the start of the subsidy period and 10 weeks after ARPA became law—employers did not have detailed information to understand ARPA’s requirements, such as definitions of certain terms. Three of eight selected employer groups and administrators we interviewed told us that employers and administrators had questions about the definition of involuntary termination and the process for sending the required notices, among others.

In addition, three of eight selected employer groups and administrators we interviewed told us they could not send the required notices informing individuals of their eligibility for the benefit without information that employers and administrators needed to determine who qualified for the COBRA subsidy. One administrator we interviewed told us that it made system changes based on assumptions before all the guidance was available because of the tight timeline and had to revise some of its processes after guidance became available. Four of eight selected employer groups and administrators we interviewed told us that once all of the guidance became available, employers and administrators did not have a lot of time to determine and notify individuals of their eligibility for the COBRA subsidy.

Application of emergency relief notices. The emergency relief notices, which extended certain time frames related to the COBRA benefit, made it more difficult for employers and administrators to implement the COBRA subsidy, according to all eight selected employer groups and administrators we interviewed. Five of the eight reported that these notices made it more difficult for employers to determine how long certain individuals remained eligible for COBRA and how much time these individuals had to elect the benefit, all of which affected employers’ and administrators’ ability to determine eligibility.

Shortened timelines. Employers, including the administrators they worked with, that elected to wait for EBSA’s model notices had fewer than 60 days to send the required notices to individuals who experienced qualifying events before April 1, 2021. For these individuals, employers and administrators had until May 31, 2021 (i.e., within 60 days of April 1, 2021) to send the required notices. Although not required to use the model notices, two of three selected administrators we interviewed told us that they waited for EBSA’s model notices to ensure accuracy in the notices that they sent to eligible individuals. Though EBSA met its statutory deadline to release the model notices within 30 days of ARPA’s enactment on April 9, 2021, employers and administrators that waited were left with fewer than 60 days to send some required notices. Moreover, according to one administrator, the shortened time frame within which it had to send out the required notices also was challenging because the volume of notices to be mailed was orders of magnitude greater than the typical volume.

Three of eight selected employer groups and administrators we interviewed said earlier guidance, and two others said clearer guidance, could have helped with the implementation. Six of eight employer groups and administrators told us that once all of the guidance was available (about 16 weeks after the start of the subsidy period on April 1, 2021), they were able to implement the COVID-19-related COBRA premium subsidy.

Delays in receiving the tax credit. In addition to the challenges related to determining eligibility and sending the COBRA notices, officials from one of three selected administrators we interviewed also told us that they experienced some delays when claiming the COBRA tax credit from IRS. Specifically, officials told us that some employers did not receive the COBRA tax credit in a timely manner due to IRS’s backlog of employment tax returns waiting to be processed. In addition, according to two groups that represented the interest of employees, a few multi-employer plans—i.e., those plans to which more than one employer are required to contribute, which are maintained pursuant to one or more collective bargaining agreements, and which must satisfy other regulatory requirements—also experienced delays in receiving their COBRA tax credits from IRS.[25] IRS officials told us that the agency had challenges processing multi-employer plans’ returns because they required manual processing.

Overall, stakeholder perspectives on agency efforts were positive. Five of eight selected employer groups and administrators we interviewed told us they appreciated the agencies’ efforts to implement the COBRA subsidy under a tight timeline.

More than 30,000 Employers Received $1.2 billion in Tax Credits for Providing COBRA Subsidies, but No Studies Have Been Conducted on the Effect of the Subsidy

More than 30,000 employers reported to IRS that their former employees utilized the COBRA subsidy, according to employment tax returns IRS processed as of February 2024. These employers also reported receiving approximately $1.2 billion in tax credits for providing COBRA subsidies to individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic.[26] Of the more than 30,000 employers that reported receiving tax credits for providing the subsidy to eligible individuals, 71 percent engaged in business in one of 10 industry categories, including professional, scientific, and technical services; manufacturing; and health care and social assistance. (See table 2.) More than 85 percent of the employers that reported receiving tax credits for providing the subsidy had at least 20 employees—i.e., the minimum size of private-sector employers that are subject to COBRA—and about 9 percent had fewer than 20 employees.[27]

Table 2: The Number of Employers That Received Tax Credits for providing Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) Subsidies to Eligible Individuals, by Industry Category

|

Industry category |

Number of unique employers receiving COBRA tax credits |

Percent of total |

|

Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services |

4,502 |

14.6 |

|

Manufacturing |

3,752 |

12.1 |

|

Health Care and Social Assistance |

2,491 |

8.1 |

|

Personal Care and Other Services; Civic, Social, and Other Organizationsa |

1,955 |

6.3 |

|

Retail Trade |

1,911 |

6.2 |

|

Construction |

1,751 |

5.7 |

|

Wholesale Trade |

1,640 |

5.3 |

|

Finance and Insurance |

1,490 |

4.8 |

|

Administrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services |

1,443 |

4.7 |

|

Accommodation and Food Services |

1,000 |

3.2 |

|

Subtotal |

21,935 |

71.0 |

|

All Othersb |

8,976 |

29.0 |

|

Total |

30,911 |

100.0 |

Source: GAO analysis of aggregate Internal Revenue Service (IRS) employment tax return data, based on employment tax returns processed as of February 21, 2024. | GAO‑25‑107055

Notes: Includes employment tax return data from IRS Forms 941 and 941X. Employers that filed more than one employment tax return for the second, third, and fourth quarters of calendar year 2021 and the first quarter of calendar year 2022, including those that filed both an original and an amended return, are each counted once. Data used for categorizing the number of employers receiving COBRA tax credits by industry category are subject to taxpayer reporting error, according to IRS officials.

aThe Personal Care and Other Services; Civic, Social, and Other Organizations category includes North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes that start with 81, which IRS labels as “Other Services”. Examples of businesses in this category include automotive repair and maintenance establishments, barber shops, religious organizations, labor unions, among others.

bAll Others also includes employers that reported null or missing values in the NAICS fields.

Employers in 10 industry categories reported receiving almost 82 percent of the $1.2 billion in tax credits for providing COBRA subsidies to eligible individuals, based on information that approximately 30,000 employers reported on their employment tax returns. These 10 industry categories included personal care and other services and civic, social, and other organizations; professional, scientific, and technical services; and manufacturing. (See table 3.)

Table 3: The Amount of Tax Credits Employers Received for Providing Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) Subsidies to Eligible Individuals, by Industry Category

|

Industry category |

Amount of tax credits |

Percent of total |

|

Personal Care and Other Services; Civic, Social, and Other Organizationsa |

$477,031,931 |

39.5 |

|

Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services |

$113,227,143 |

9.4 |

|

Manufacturing |

$88,307,942 |

7.3 |

|

Administrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services |

$66,685,859 |

5.5 |

|

Finance and Insurance |

$53,022,319 |

4.4 |

|

Accommodation and Food Services |

$48,425,376 |

4.0 |

|

Retail Trade |

$44,378,931 |

3.7 |

|

Health Care and Social Assistance |

$36,728,853 |

3.0 |

|

Information |

$31,575,952 |

2.6 |

|

Wholesale Trade |

$28,831,991 |

2.4 |

|

Subtotal |

$988,216,297 |

81.8 |

|

All Othersb |

$220,492,284 |

18.2 |

|

Total |

$1,208,708,581 |

100.0 |

Source: GAO analysis of aggregate Internal Revenue Service (IRS) employment tax return data, based on employment tax returns processed as of February 21, 2024. | GAO‑25‑107055

Notes: Includes employment tax return data from IRS Forms 941 and 941X. Data used for categorizing the amount of tax credits employers reported receiving for providing COBRA subsidies by industry category are subject to taxpayer reporting error, according to IRS officials.

aThe Personal Care and Other Services; Civic, Social, and Other Organizations category includes North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes that start with 81, which IRS labels as “Other Services”. Examples of businesses in this category include automotive repair and maintenance establishments, barber shops, religious organizations, labor unions, among others.

bAll Others also includes COBRA subsidies reported by employers that reported null or missing values in the NAICS fields.

Employers in one industry category—personal care and other services and civic, social, and other organizations industries—reported receiving almost 40 percent (or about $477 million) of the tax credits for providing COBRA subsidies.[28] Employers with at least 20 employees reported receiving more than 80 percent of the tax credits for providing the subsidies.[29] Employers also reported receiving almost 95 percent of the tax credits for providing COBRA subsidies during the second and third quarters of calendar year 2021, which is also the subsidy period.[30]

Our review of the literature did not find any studies that examined the effects of the COBRA subsidy during the COVID-19 pandemic, and IRS does not have any reliable information available on the number of individuals who received the subsidy, according to IRS officials.[31] As of April 2024, EBSA and IRS also had not studied or planned to study the effects of the COBRA subsidy during the pandemic, according to agency officials. In addition, seven of the eight selected employer groups and administrators and all three selected employee groups we interviewed told us that they did not conduct studies either. One employer group we interviewed conducted a survey of its members during the pandemic when the COBRA subsidy was in effect; however, the survey did not yield robust response rates, according to the group.

Although we did not find empirical information about the effects of the subsidy, the selected external stakeholders we interviewed shared limited observations about individuals who were eligible for the subsidy based on their experiences. For example, two of three selected employee groups we interviewed told us that they believed the subsidy benefited those who worked in industries that were disproportionately affected by job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the entertainment industry. One of these groups also told us that they believed the COBRA subsidy enabled individuals to maintain a place in or close to the middle class and not to slip economically. In addition, four of eight selected employer groups and administrators we interviewed told us that COBRA enrollment increased during the period that the subsidy was available.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Labor and the Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service for review and comment. The Departments of Labor and the Treasury did not have any comments on the report and the Internal Revenue Service provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

As agreed with your office, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies of this report to the Secretaries of Labor and the Treasury, the Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7114 or DickenJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix I.

Sincerely,

John Dicken

Director, Health Care

GAO Contact

John Dicken, (202) 512-7114 or DickenJ@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Kristi Peterson (Assistant Director), Xiaoyi Huang (Analyst-in-Charge), Mikaela Chandler, Eric Chen, Kaitlin Farquharson, Joy Grossman, and Laurie Pachter made key contributions to this report. Also contributing were David Jones and Ethiene Salgado-Rodriguez.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Pub. L. No. 99-272, tit. X, 100 Stat. 82, 222-37 (1986) (codified in relevant part at 26 U.S.C. § 4980B, 29 U.S.C. §§ 1161–1169, and 42 U.S.C. §§ 300bb-1–300bb-8). COBRA also applies to health coverage sponsored by employee organizations, such as labor unions.

[2]Enrollees in COBRA coverage may have to pay for the entire premium (both the employer and employee shares) plus an administrative fee.

[3]Pub. L. No. 117-2, § 9501(a), 135 Stat. 4, 127–34. Hereinafter this provision will be referred to as the “COVID-19-related COBRA premium subsidy” or “COBRA subsidy”.

[4]The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) within the Department of Health and Human Services also administers the COBRA coverage laws as they apply to state and local government plans. In this report, we focus on EBSA’s and IRS’s implementation activities and not CMS’s because EBSA and IRS have responsibility over COBRA’s disclosure, notification, eligibility, coverage, and payment provisions. CMS advises, consults, and coordinates with EBSA and IRS in the administration of the COBRA coverage requirements.

[5]We interviewed American Benefits Council; Automatic Data Processing, Inc.; Business Group on Health; Employee Benefit Research Institute; The ERISA Industry Committee; HealthEquity, Inc.; Society for Human Resource Management; and WEX Inc.

[6]We reviewed publicly available information about the number and size of employers represented or served by these groups and selected those that either represented or served a lot of employers (e.g., groups with over 320,000 members who are human resource professionals, those that serve 1,000 employer clients, etc.) or companies with a lot of employees (e.g., companies with over 10,000 employees, Fortune 100 companies that collectively cover more than 60 million lives, etc.).

[7]We reviewed articles published as early as 2009 because the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) provided a COBRA subsidy for certain individuals who were involuntarily terminated from their jobs between September 2008 and May 2010.

[8]We interviewed the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, and the National Coordinating Committee for Multiemployer Plans.

[9]Although COBRA requires plan sponsors to provide continuation coverage, it requires group health plans to notify eligible individuals of their rights to this coverage, among other requirements. In this report, unless otherwise specified, we describe COBRA’s requirements as applying to employers generally because they are often the plan sponsors of the group health plans. COBRA does not apply to federal employers. Employers in states with continuation coverage laws similar to COBRA also may be subject to those laws.

[10]COBRA coverage can be extended for a total of 36 months for the spouse or dependent child if the initial qualifying event (or a secondary qualifying event) is the death of the covered employee, divorce or legal separation of the covered employee from the covered employee’s spouse, the covered employee becomes entitled to Medicare (i.e., the federal health insurance program for people who are 65 or older, certain people with disabilities, and people with end-stage renal disease), or a dependent child ceases to be a dependent child.

[11]If applicable, employers also must provide a notice of unavailability of coverage or a notice of early termination of coverage. Employers, including the administrators they work with, generally have processes in place for administering the COBRA benefit, according to selected employer groups and administrators we interviewed. Some employers administer the benefit themselves and others hire administrators to fulfill the function.

[12]AHRQ’s Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component estimated that there were about 1.25 million private-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 41,000 and 82,000 non-federal, public-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 7,000, for a total of about 1.33 million COBRA enrollees in 2019. AHRQ’s survey estimated that there were about 1.03 million private-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 39,000 and 75,000 non-federal, public-sector COBRA enrollees with a standard error of 4,000, for a total of about 1.11 million COBRA enrollees in 2022. Enrollees include former employees (excluding retirees and dependents).

EBSA, using different survey data and methodology, also has reported annual estimates of COBRA enrollment. For example, EBSA reported that about 2.6 million individuals enrolled in COBRA in calendar year 2021. According to EBSA officials, the questionnaire used to generate the data EBSA used to impute the number of COBRA enrollees changed in 2014, affecting its estimates from 2018 and onward. Both AHRQ and EBSA’s estimates are subject to limitations of a survey.

[13]EBSA and IRS also have jurisdiction over group health plans sponsored by employee organizations, such as labor unions.

[14]Pub. L. No. 117-2, 135 Stat. 4.

[15]Examples of reduction in hours include a change in the employer’s hours of operations, a furlough, a temporary leave of absence, and work stoppage as a result of a lawful strike or a lockout, according to agency guidance. Examples of involuntary termination include resignation as a result of a material change in the geographic location of employment, resignation as a result of employer’s action or inaction that resulted in a material negative change in the employment relationship analogous to a constructive discharge, and employer’s decision to not renew an employee’s contract if the employee was otherwise willing and able to continue the employment relationship unless the contract was for specified services intended to end after a set term, according to agency guidance.

[16]Pub. L. No. 111-5, div. B, tit. III, § 3001, 123 Stat. 115, 455-66.

[17]See for example David M Zimmer, “Did subsidies included in the 2009 Stimulus Package encourage enrolment in COBRA?,” Fiscal Studies, 43 (2022): 405-419; Asako S. Moriya and Kosali Simon, Impact of premium subsidies on the take-up of health insurance: Evidence from the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 20196, Cambridge, MA, June 2014; and Berk, Jillian and Rangarajan, Anu, “Evaluation of the ARRA COBRA Subsidy: Final Report,” (Feb. 2015), accessed December 26, 2023, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/research/publications/evaluation‑arra‑cobra‑subsidy‑final‑report.

[18]ARPA required the Secretary of Labor, in consultation with the Secretaries of the Treasury and Health and Human Services, to release model notices within 30 days of the law’s enactment. Pub. L. No. 117-2, § 9501(a)(5)(D), 135 Stat. at 131.

[19]These model notices included (1) a general notice and COBRA election notice for individuals who experienced a qualifying event from April 1, 2021, through September 30, 2021, (2) an extended COBRA election notice for those who had qualifying events before April 1, 2021, (3) an alternative COBRA election notice for individuals covered by state continuation coverage requirements like COBRA, and (4) a notice of expiration of the subsidy.

[20]Questions answered in these documents included: which individuals qualify for the COBRA subsidy, can individuals whose qualifying event is a voluntary reduction in hours or a furlough be eligible for the COBRA subsidy, which circumstances constitute an involuntary termination of employment, can the subsidy be applied toward COBRA coverage prior to April 1, 2021, can employers rely on employee attestation for determining eligibility for the COBRA subsidy, when eligible individuals must elect COBRA coverage, which plans the COBRA subsidy applied to, and others.

[21]Employers and others that would have otherwise received the premium payments can claim the COBRA tax credit on their quarterly employment tax returns for the second, third, and fourth quarters of calendar year 2021 and the first quarter of calendar year 2022. April 2025 is 3 years after the filing due date for quarterly employment tax returns for the first quarter of calendar year 2022.

[22]The remainder of the outstanding employment tax returns contain claims for another tax credit and have been held from processing since September 2023 to give IRS time to conduct a study to help inform next steps with respect to this tax credit.

[23]Example of case resolution includes complainant receiving the COBRA notice after EBSA opened its investigation.

[24]ARPA required individuals enrolled in COBRA with the subsidy to notify their group health plan if they became ineligible for the subsidy. Individuals who fail to notify their plan must pay a penalty. Pub. L. No. 117-2, § 9501(b)(2), 135 Stat. at 136-37 (codified at 26 U.S.C. § 6720C).

[25]IRS officials told us that multi-employer plans typically employ a small number of employees and owe less in payroll taxes than the amount of COBRA tax credits they can claim. Thus, instead of just paying a reduced amount of payroll taxes, multi-employer plans have to wait for IRS to process their employment tax returns to issue a refund for the amount of COBRA tax credits that exceeded their payroll tax obligations.

[26]The number of employers that claimed the COBRA tax credit is less than the number of employment tax returns with claims for the COBRA tax credit that IRS processed, because employers were able to claim the COBRA tax credit on their returns for the second, third, and fourth quarters of calendar year 2021 and the first quarter of calendar year 2022. Thus, a single employer could submit more than one return over the four quarters and for each quarter if they needed to amend their original filing.

[27]About 5 percent had missing or unknown information for the number of employees.

[28]Examples of businesses in this category include automotive repair and maintenance establishments, barber shops, religious organizations, labor unions, among others.

[29]The remainder of the $1.2 billion in tax credits for providing COBRA subsidies were received by employers that reported they had fewer than 20 employees or had missing or unknown information for the number of employees.

[30]Although the COVID-19-related COBRA premium subsidy eligibility period was from April 1, 2021, through September 30, 2021, employers who provided subsidies during that period can claim the tax credit from IRS on their employment returns for the second, third, and fourth quarters of calendar year 2021 and the first quarter of calendar year 2022.

[31]Employers who claimed the COBRA tax credit are required to report information on the number of individuals who received the subsidy to IRS. However, IRS officials told us the agency does not use this data to process the employment tax returns.