UKRAINE

State Should Build on USAID’s Oversight of Direct Budget Support

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Latesha Love-Grayer at lovegrayerl@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The World Bank oversees the Public Expenditures for Administrative Capacity Endurance in Ukraine (PEACE) project that has provided direct budget support (DBS) to Ukraine, while the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) helped oversee U.S. funding to PEACE until this responsibility was transferred to State in July 2025. DBS reimburses Ukraine’s government for eligible salaries and social assistance benefits (see figure). From July 2022 to June 2025, USAID hired contractors to oversee DBS funding and used information from contractors’ reports to enhance this oversight. For example, USAID asked one contractor to review more healthcare worker salaries after they found discrepancies. USAID canceled one of its oversight contracts in February 2025 and State officials said they took over the other in July 2025 as part of the reorganization of foreign assistance. These changes reduced U.S. oversight of DBS funding.

USAID did not regularly verify or use all available data to inform DBS oversight. While USAID reviewed aggregated expenditure data, it did not review the detailed data it received. We analyzed a subset of this data and identified 161 unusual increases out of 5,121 expenditure changes. Finding the cause for these increases would inform any continuing oversight of U.S. DBS funding. Further, information USAID reported to Congress on Ukraine’s use of this funding may be incomplete because USAID did not update this reporting once new data became available. USAID also did not submit one required report to Congress. Ensuring accurate and complete reports would provide Congress with greater transparency about how U.S. DBS funding was used.

USAID and World Bank contractors identified weaknesses in Ukraine’s internal controls for managing PEACE project funding, such as decentralized processes. In response, USAID’s contractor developed 56 recommendations to strengthen related controls. Ukrainian officials GAO met with in Kyiv generally agreed with the recommendations, but said they would take time to implement. USAID did not assess the weaknesses to determine which present the highest risk to managing DBS funding. Taking steps to assess these weaknesses would help Ukraine prioritize its efforts on addressing the highest risks to managing DBS. A World Bank contractor also identified weaknesses in Ukraine’s internal controls for managing DBS. According to the World Bank, although these weaknesses pose risks, they are mitigated by the project’s multi-layered oversight. However, USAID did not consistently request updates on Ukraine’s actions to address the weaknesses which could help focus U.S. oversight priorities on areas more vulnerable to waste, fraud, or abuse.

Why GAO Did This Study

The United States has provided over $45 billion in DBS to Ukraine since Russia's February 2022 invasion. This DBS supports Ukraine’s critical government functions. USAID managed $30.2 billion in appropriated funds, with most provided through the World Bank’s PEACE project. As of December 2024, all of this funding had been disbursed to Ukraine. Treasury also disbursed $20 billion to the World Bank for economic aid to Ukraine, including at least $15 billion for DBS, using revenues earned from immobilized Russian assets. As of July 2025, the World Bank had disbursed $4.64 billion of this funding to Ukraine through the PEACE project.

GAO was asked to evaluate the oversight of U.S. DBS funding provided to Ukraine through the PEACE project. This report examines (1) how USAID’s oversight for U.S. DBS funding changed over time, (2) the extent to which USAID ensured it had quality data to inform its oversight activities and congressional reporting; and (3) weaknesses identified in Ukraine’s processes for managing DBS funding and the extent to which USAID ensured those weaknesses were addressed.

GAO reviewed documents from USAID and the World Bank, their contractors, and the Ukrainian government; met with officials in Washington, D.C.; conducted a site visit to Ukraine; and analyzed PEACE project-related data.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making five recommendations to State to enhance oversight of DBS funding and improve reporting to Congress on the use of DBS funds. State neither agreed nor disagreed with the recommendations.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

AUP |

agreed-upon procedure |

|

DBS |

direct budget support |

|

FORTIS Ukraine FIF |

Facilitation of Resources to Invest in Strengthening Ukraine Financial Intermediary Fund |

|

G7 |

Group of Seven |

|

PEACE |

Public Expenditures for Administrative Capacity Endurance in Ukraine |

|

USAID |

U.S. Agency for International Development |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 24, 2025

The Honorable James E. Risch

Chairman

Committee on Foreign Relations

United States Senate

The Honorable Brian J. Mast

Chairman

Committee on Foreign Affairs

House of Representatives

The Honorable Michael T. McCaul

House of Representatives

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has threatened the country’s sovereignty and created a humanitarian crisis. In response, Congress appropriated more than $174 billion across the federal government under five Ukraine supplemental appropriations acts.[1] From this funding, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) disbursed about $30.2 billion for direct budget support (DBS) for the government of Ukraine from April 2022 to December 2024. Responsibility for oversight of this funding transferred from USAID to the Department of State on July 1, 2025, according to State. Treasury also disbursed $20 billion in funding to the World Bank for economic aid to Ukraine, including $15 billion to be used for DBS, in December 2024. DBS is intended to ensure Ukraine can continue critical operations and deliver essential services to its citizens. For example, the funding has supported Ukraine in paying salaries for school and non-security sector government employees and for some types of social assistance payments. At least 15.8 million Ukrainian citizens have benefited from this assistance, according to our analysis of Ukrainian expenditure reports.

This report is part of a series of GAO reports that both describe and evaluate U.S. agencies’ use of the funds appropriated in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Among other topics, GAO has previously reported on the Department of State’s and USAID’s support for Ukrainian refugees and internally displaced persons, U.S. planning and coordination for assisting in Ukraine’s recovery, and the status of foreign assistance funding appropriated through the Ukraine supplementals.[2] We also previously described the existing oversight of U.S. DBS, including the scopes and limitations of these oversight approaches.[3]

You asked us to evaluate the oversight of the U.S. DBS funding provided to Ukraine through the Public Expenditures for Administrative Capacity Endurance in Ukraine (PEACE) project, a World Bank multi-donor trust fund established in June 2022. This report examines (1) how USAID’s oversight for U.S. DBS funding changed over time; (2) the extent to which USAID ensured it had quality data to inform its oversight activities and congressional reporting; (3) weaknesses USAID identified in Ukraine’s processes for managing DBS funding and the extent to which USAID ensured these weaknesses were addressed; and (4) weaknesses the World Bank has identified in Ukraine’s processes for managing PEACE project funding and any USAID efforts to monitor how these weaknesses are addressed.

To examine the extent to which USAID’s oversight for U.S. DBS funding changed over time, we reviewed documentation from USAID and its contractors, Deloitte and KPMG. We interviewed USAID headquarters and Mission Ukraine officials, as well as Deloitte and KPMG staff as applicable, about their use of information for DBS monitoring, oversight, and any ongoing and planned technical assistance provided from September 2022 to January 24, 2025. We also traveled to Ukraine in June 2024 to meet with many of these officials in person and visit regional Ukrainian government centers and schools to learn about their processes for compiling expenditure information for PEACE project-related reporting. To understand DBS oversight plans following the administration’s foreign assistance pause, we interviewed USAID, State, and Treasury officials, and reviewed relevant documentation.

To examine the extent to which USAID used quality data to inform oversight activities and congressional reporting, we reviewed Ukrainian expenditure verification reports, Deloitte deliverables, and communications between USAID and the World Bank. We interviewed USAID and Deloitte officials about their processes for reviewing Ukrainian expenditure data and any use of data analytics to identify anomalous transactions that warranted further examination. We evaluated USAID’s processes against a leading practice identified in GAO’s Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs—the practice of using data analytics to identify suspicious activities or transactions, including anomalies, outliers, and other concerns in data.[4] To demonstrate the value of such analytics, we independently analyzed detailed expenditure data to identify anomalous expenditures. We also compared the DBS data that USAID had reported to Congress against Deloitte documentation to assess the reliability of reported DBS disbursements, applying federal internal control standards for quality data.[5]

Additionally, we examined how USAID, its contractors, and a World Bank contractor identified and addressed weaknesses in Ukraine’s internal controls for managing DBS and PEACE project funding. This included a review of Deloitte, KPMG, and PwC reports, as well as USAID risk assessments. We interviewed USAID and World Bank officials to understand how these findings were used to guide oversight and technical assistance, in accordance with federal internal control standards to identify, analyze and respond to risk and to use quality information.[6] For more details of our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2023 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Effects of Russia’s Invasion on Ukraine’s Economy and Operating Environment

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, has affected almost every aspect of life in Ukraine. Prior to the start of the war, Ukraine had a population of 41 million people. In early April 2022, the United Nations reported that 11.6 million Ukrainians had left their homes, with 4.5 million recorded as refugees in Europe and another 7.1 million displaced internally. The United Nations had also recorded 3,527 civilian casualties in Ukraine at that time (1,430 killed and 2,097 injured). In late May 2022, the World Bank reported that Ukraine faced sizable non-military financing needs of $31.4 billion in 2022 because of the large civilian salaries and social assistance spending needs and sharply declining revenues following Russia’s invasion.

More than three years later, war continues to affect life in Ukraine as Russian government forces target civilian population centers far from the front line with aerial strikes. As of December 2024, an estimated 6.3 million people had been recorded as refugees across Europe, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and an estimated 3.7 million people in Ukraine remained internally displaced as a result of the ongoing conflict. In addition, as of December 2024, the number of people killed (12,456) or injured (28,382) had increased significantly. According to the United Nations, the estimated number of people needing humanitarian assistance in Ukraine rose from 2.9 million in 2021 to 17.6 million by the end of 2022. Further, approximately 56 percent of Ukraine’s total expenditures for 2025 will be for security and defense, compared to less than 10 percent of expenditures from 2000 through 2021, according to State. State projects that Ukraine will need an estimated $45.1 billion to fulfill its essential expenditures in 2025, based on International Monetary Fund information from June 2025.

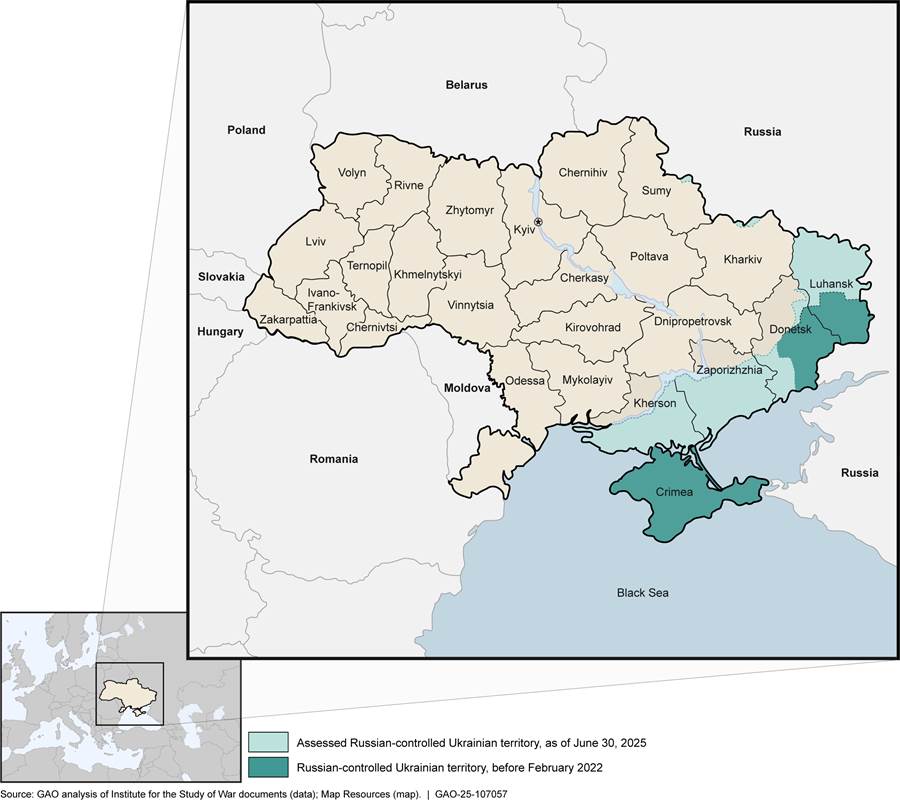

In addition to Ukraine’s immediate and ongoing financial needs, the country has faced operational challenges. Continuous shifts in Ukrainian territorial control have occurred since the start of the war in February 2022. See figure 1 for a map of Ukraine and its regions, including those on the front lines, as of June 2025. Moreover, missiles and drones have destroyed over half of Ukraine’s energy generation capacity, damaging power plants and substations, which has cut electricity and heat in many cities. The shifting front lines of the war, power outages, and other related difficulties have resulted in challenging working conditions for Ukrainian government officials, U.S. government officials, and other entities providing and overseeing support for Ukraine. In addition, many USAID staff from Mission Ukraine worked remotely from other locations from February 2022 through the summer of 2023 because of security conditions in Ukraine.

U.S. DBS Provided to Ukraine

From the start of Russia’s invasion through December 2024, the United States was a leading contributor of DBS to Ukraine. As of August 2025, the United States had disbursed approximately $45 billion in DBS funding to the World Bank to support Ukraine—about $30.2 billion in appropriated funding and $15 billion obtained through a loan that will be serviced and repaid with the revenues from immobilized Russian sovereign assets.[7]

Approximately $30.2 billion of the DBS funding the U.S. disbursed for Ukraine was appropriated by Congress through the Ukraine supplementals. USAID, which manages U.S. DBS, disbursed this funding from April 2022 through December 2024 to the World Bank for Ukraine. USAID disbursed this funding to four World Bank trust funds:

· Financing of Recovery from Economic Emergency in Ukraine (FREE Ukraine) multi-donor trust fund ($1 billion). The U.S. disbursed this DBS funding in April and May 2022 to cover Ukraine’s unanticipated budget financing gap for non-military expenses due to the outbreak of war.

· Single-donor trust fund ($1.7 billion). USAID and the World Bank established this trust fund in July 2022 to allow a rapid, standalone U.S. contribution to support Ukraine. USAID and Ukraine agreed that these funds were to be used to reimburse Ukraine for salary payments made to healthcare workers. The funding was used to reimburse workers at over 2,000 healthcare organizations from January 2022 through July 2022.[8]

· PEACE project multi-donor trust fund ($25.9 billion). The World Bank established this trust fund in June 2022 to reimburse Ukraine for eligible salary expenses, and later expanded it to include other categories as the war continued and donations increased. The U.S. disbursed $25.9 billion to Ukraine through this trust fund between June 2022 and December 2024.

· Special Program for Ukraine and Moldova Recovery ($1.6 billion). USAID disbursed a $1.6 billion contribution to the World Bank’s Special Program for Ukraine and Moldova Recovery, through a trust fund, in November 2024. This contribution allowed Ukraine to secure a $4.8 billion loan from the World Bank through the PEACE project.[9]

In addition, USAID obligated approximately $535 million from funding it received through the Ukraine Security Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2024, to guarantee a $20 billion loan to Ukraine that Treasury secured and disbursed in December 2024. According to Treasury, the proceeds of the U.S. loan were intended for economic aid to Ukraine, including DBS.[10] Funding for this loan was serviced and will be repaid with revenues earned from immobilized Russian sovereign assets held in the European Union,[11] as part of a $50 billion loan package from the Group of Seven (G7) countries. Canada, Japan, and the U.S. are channeling a portion of the loan proceeds to Ukraine through a World Bank fund, the Facilitation of Resources to Invest in Strengthening Ukraine Financial Intermediary Fund (FORTIS Ukraine FIF).

FORTIS Ukraine FIF contribution to PEACE ($15 billion).[12] On December 13, 2024, the Governing Committee of the FORTIS Ukraine FIF approved the use of $15 billion of the $20 billion U.S. contribution to be disbursed to Ukraine as a grant for DBS through the PEACE project.[13]

As of July 2025, the World Bank had disbursed $4.64 billion of this funding to reimburse Ukraine for eligible expenses through the PEACE project, according to Treasury officials, and $10.36 billion remains available for the PEACE project.

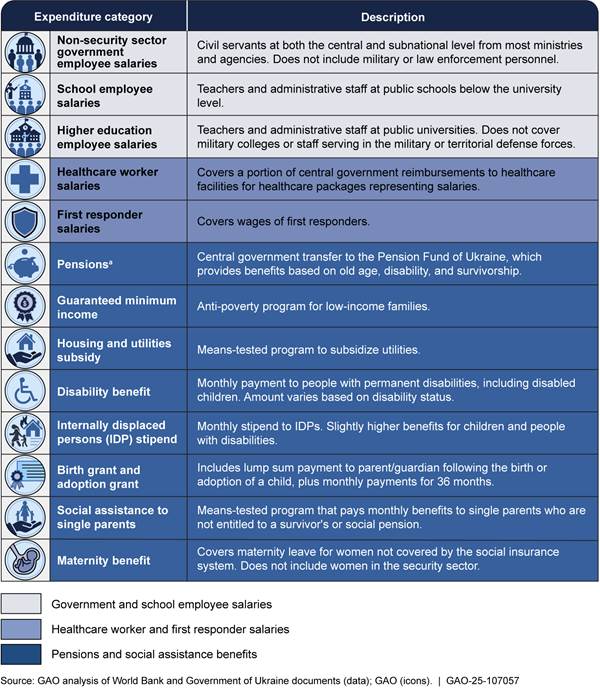

PEACE Project Expenditure Categories

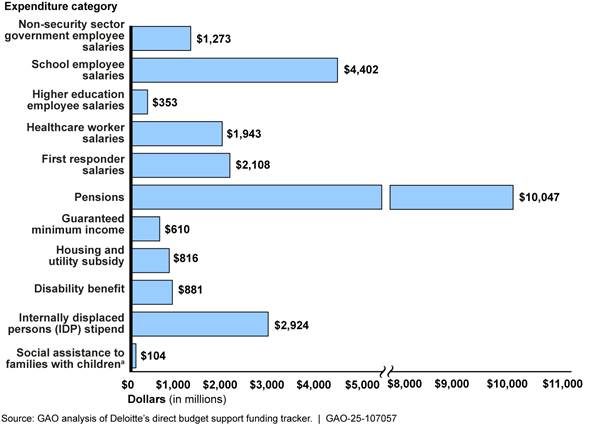

The PEACE project provides DBS to Ukraine on a reimbursable basis for pre-approved eligible expenses. The PEACE project was initially designed to reimburse Ukraine for a portion of salary expenses for school employees and non-security sector government employees. The project has since been expanded to reach other vulnerable populations and includes up to 13 expenditure categories, as shown in figure 2. DBS funding appropriated through the Ukraine Security Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2024, enacted in April 2024, was not allowed to be used for pension payments.[14]

Figure 2: Ukrainian Government Expenditure Categories Covered under the Public Expenditures for Administrative Capacity Endurance in Ukraine (PEACE) Project

aU.S. DBS funding provided through the Ukraine Security Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-50, Div. B, 138 Stat. 895, 914 (Apr. 24, 2024) could not be used to reimburse pension payments.

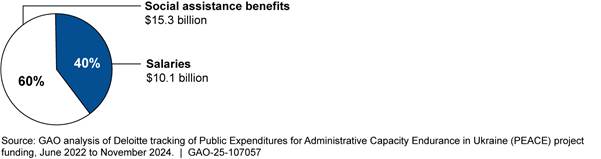

From June 2022 to November 2024, the majority of PEACE project funding disbursed by the U.S. was used to reimburse pension payments and salaries.[15] As figure 3 shows, more than one-third of U.S. funding had been used to reimburse Ukraine for pension payments ($10 billion) and about the same amount had been used to cover salary expenditures across five categories ($10.1 billion), as of November 2024. The remaining funding had been used to reimburse Ukraine for other social assistance benefits, including approximately $3 billion that the Ukrainian government provided to internally displaced persons. Deloitte verified that U.S. funding appropriated through the Ukraine Security Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2024, that USAID allocated for DBS was not used to reimburse pension payments in accordance with legislation.

Figure 3: U.S. Funding Provided to Ukraine through the Public Expenditures for Administrative Capacity Endurance in Ukraine (PEACE) Project, by Category, June 2022 to November 2024

Note: This chart does not include $465 million that USAID disbursed to the PEACE project in December 2024 because Deloitte, USAID’s contractor, could not complete the tracking of how this funding was used due to a stop-work order and subsequent cancellation of the contract, according to Deloitte.

aDeloitte combined the disbursement totals for the (1) birth grant and adoption grant, (2) social assistance to single parents, and (3) maternity benefit categories in its direct budget support funding tracker.

PEACE project funding has helped Ukraine substantially mitigate the negative social impacts of the war, according to World Bank reporting. For example, the World Bank found that more than 85 percent of health clinics were fully operational in 2023 and that at least 89 percent of school-aged children were enrolled in school. While in Ukraine, we met with school officials about their processes for reporting PEACE project-eligible expenditures and observed a bomb shelter that provides safety for enrolled students (see fig. 4). As of February 2025, the World Bank reported that the government of Ukraine was able to pay the salaries for 100 percent of non-security sector government employees and 100 percent of first responders on time. In addition, almost 90 percent of social assistance recipients had received their benefits on time.

Figure 4: Ukrainian Schoolchildren Taking Refuge Inside School Shelter During an Air Raid Alert, June 2024

Entities Involved in Implementation and Oversight of the PEACE Project

Several U.S. government agencies, the World Bank, the government of Ukraine, and other entities have supported the implementation and oversight of DBS funding provided to Ukraine through the PEACE project. The key U.S. agencies involved include USAID, State, and Treasury.

· USAID. USAID managed the U.S. DBS funding appropriated through the Ukraine supplementals. The agency was responsible for ensuring monitoring and oversight of U.S. DBS funds provided to Ukraine. In addition, as the administrator of appropriated U.S. contributions to the PEACE project, USAID assumed specific reporting responsibilities.[16]

· State. State’s Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs led U.S. government policy for providing Ukraine assistance in coordination with Treasury, USAID, and others, according to State officials. As part of this effort, State led interagency discussions to determine the mechanism through which the U.S. would provide DBS to Ukraine and agreed upon World Bank trust funds. In addition, State took on various reporting responsibilities related to the Ukraine supplemental funding, including reporting related to DBS funding.[17] In July 2025, State absorbed USAID's responsibilities for oversight of appropriated U.S. DBS funding, according to State.

· Treasury. For all World Bank projects, including U.S. funding for Ukraine provided through the World Bank, Treasury acts as the primary U.S. government liaison to the Bank and conducts some due diligence activities. These activities include reviewing project-related information and coordinating with other U.S. agencies, as needed, according to Treasury officials. Treasury also works with the International Monetary Fund and the finance ministries of the G7 countries to collectively address Ukraine’s financing needs, which helped to inform administration requests for DBS funding for Ukraine. Treasury, on behalf of the U.S. government, oversees the use of FORTIS Ukraine FIF funding through its role on this fund’s Governing Committee and membership on the World Bank Board.

The World Bank supervises, oversees, and supports the implementation of all World Bank projects, including activities financed under the PEACE project. According to the World Bank, its risk management strategy for the PEACE project seeks to reinforce Ukraine’s systems with multiple layers of controls given the high fiduciary risks resulting from the decentralized nature of PEACE expenditures, the ongoing conflict, and the related loss of experienced government staff. The strategy includes efforts to strengthen Ukraine’s financial management systems, apply project-specific reporting requirements, and monitor project implementation through contractor oversight reviews, and surveys of Ukrainian citizens. In addition, the World Bank reviews expenditure reports from Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance before disbursing PEACE project funding. According to USAID, this review provides accountability and visibility into the use of funds while also providing a substantial safeguard to prevent corruption. Treasury officials said the World Bank plans to follow the same operating and oversight mechanisms for the FORTIS Ukraine FIF funding as for other funding sources for the PEACE project.

In addition, the government of Ukraine provides support to oversight efforts. As the recipient of DBS funding, Ukraine coordinates and implements PEACE project funding. Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance collects and verifies expenditure data from Ukrainian ministries and develops monthly expenditure reports that it submits to the World Bank to validate for reimbursement. As required for World Bank projects, Ukraine maintains a grievance redress mechanism to document any grievances reported by project beneficiaries. Ukraine shares semi-annual reports with the World Bank that include information about Ukraine’s actions to address reported grievances. BDO, an audit firm, conducted financial audits of the PEACE project for Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance. According to World Bank policy, such independent audits are required for World Bank projects. Further, the Accounting Chamber of Ukraine, Ukraine’s supreme audit institution, also conducted audits of PEACE project funding to reimburse pension payments and U.S.-specific DBS funding provided for healthcare worker salaries.

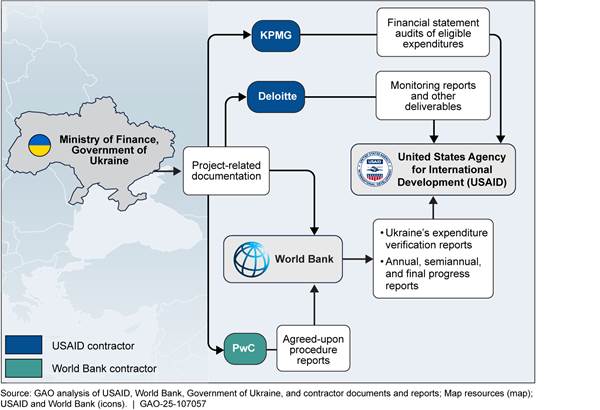

To fulfill their oversight responsibilities, the World Bank and USAID also procured support from contractors to strengthen DBS oversight.

· PwC. The World Bank hired PwC to conduct agreed-upon procedure reviews to assess whether the project’s systems are functioning as intended. According to the World Bank, it hired an independent auditor for this work given the wartime risks and the substantial amounts of funding for the project.

· Deloitte. USAID hired Deloitte to help Ukraine ensure the accountability of DBS funding and to provide technical assistance to build Ukraine’s capacity. Part of this effort included monitoring Ukraine’s use of U.S. DBS funding through analyses of Ukraine’s DBS processes and spot checks of sample expenditures reimbursed with DBS funding. Deloitte also surveyed recipients of PEACE project-related salary payments to verify the timeliness of payments and amount received.

· KPMG. In September 2023, USAID hired KPMG to conduct financial statement audits of PEACE project-related expenditures to ensure DBS funding was used as intended.

Some of the entities involved in the monitoring and oversight of DBS funding share PEACE project-related information that helps inform other entities’ efforts and decisions. Figure 5 shows which entities provided information to USAID.

If oversight entities identify any ineligible expenditures or other

inaccurately reported expenditures, Ukraine is expected to address these

findings. If errors are detected after Ukraine has submitted expenditure

reports to the World Bank, Ukraine must provide an explanation and correct the

amounts recovered by reducing the amount of eligible expenditures in a

subsequent reimbursement request, according to the World Bank. Additionally,

PEACE project agreements we reviewed between the World Bank and Ukraine state

that Ukraine is required to refund any payments if the World Bank determines

they were ineligible.

USAID Used Various Sources to Enhance Its Oversight of DBS but State Is Planning Less Oversight

USAID Supplemented World Bank Oversight of DBS Funding

According to USAID’s legal interpretation, the agency was not legally obligated to conduct detailed monitoring or oversight of the DBS funding it provided to Ukraine through the World Bank, but the agency decided to hire third-party contractors to supplement the World Bank’s oversight efforts. In an April 2022 memorandum, USAID documented the legal theory that the agency typically relies on for project contributions to a public international organization. Applying this legal theory, USAID determined that the disbursement of DBS funding accomplished a significant purpose of the contribution to the World Bank and therefore USAID legal requirements would not apply post-disbursement. In USAID legal parlance, this is referred to as “purpose accomplished upon disbursement.” According to the memorandum, the significant purposes of the award included providing urgently needed liquidity to Ukraine and promoting aid efficiency by utilizing established mechanisms that minimized the administrative burden on Ukraine and the U.S. government. The memorandum also cited a 2012 USAID Office of the General Counsel memorandum which stated that, for programs that meet this “purpose accomplished” principle, once the U.S. government has disbursed funding to the program, U.S. government statutory requirements no longer apply.

Despite USAID’s determination that it was not legally obligated to oversee this funding, USAID hired third-party contractors to supplement the World Bank’s oversight efforts because of the magnitude of U.S.-provided DBS funding, according to USAID officials. Based on interagency discussions, USAID amended its State-Owned Enterprises Reform Activity in Ukraine contract with Deloitte to establish a U.S. effort to monitor Ukraine’s use of DBS funding. Specifically, USAID officials expanded the scope of work in July 2022 for Deloitte to conduct third-party monitoring of U.S. DBS to Ukraine. USAID expanded Deloitte’s scope of work again in September 2022 to include the provision of technical assistance to the Ukrainian Ministry of Finance to ensure that funds received from the World Bank were properly disbursed to recipients, according to officials. Further, in September 2023, USAID hired KPMG to conduct financial statement audits.

USAID Used Information from Various Sources to Enhance Oversight of U.S. DBS

Between September 2022 and January 24, 2025, USAID used information about ongoing oversight to inform the scope of its work and expand its oversight to address some limitations. For example, USAID used findings from Deloitte’s spot checks of sample expenditures reimbursed with DBS funding to inform priorities for additional spot checks. Deloitte’s 2023 spot checks found that the highest proportion of discrepancies were associated with healthcare worker salaries.[18] USAID directed Deloitte to conduct more spot checks on this category in 2024, according to USAID officials. Our analysis of Deloitte’s spot check reports confirmed that Deloitte conducted more checks for the healthcare worker salaries category in 2024 (317) than in 2023 (196). Deloitte conducted more spot checks for this category than any other category in 2024.

In addition, USAID requested that Deloitte investigate the individual DBS recipients selected for spot checks that refused to sign consent forms to determine whether their refusal indicated any potential concerns. Deloitte’s spot checks include testing of salary and social benefits payments to individual recipients that were eligible for DBS reimbursement. Deloitte reported that consent is required for access to personal data, per Ukrainian law. In 2023, Deloitte conducted 443 spot checks of individual salary payments. However, Deloitte was unable to obtain consent forms from 151 individuals in the initial sample.[19] According to USAID officials, the agency requested that Deloitte further examine salary payments to these individuals. Through this review, Deloitte found that 81 of the 151 individuals had resigned or died in the period between when the payment was made and Deloitte’s outreach. For the other 70 individuals that refused consent, Deloitte developed alternative spot check procedures, including a questionnaire for the individual and a certification procedure for their employing institution, to verify whether the selected payments were correct. Deloitte did not identify any discrepancies in the paid salaries for the 70 individuals in this sample.

|

Deloitte Surveys for the PEACE Project Survey purpose: Deloitte used Ukraine’s official e-governance mobile application, Diia, to collect insights on (1) the timeliness of salary payments reimbursed by DBS, (2) the completeness of payments, and (3) feedback on any issues that arose during the reimbursement process. Survey population: Non-security sector government employees and first responders whose salaries were reimbursed by DBS and who were active users of the Diia application. Survey results: Ninety-nine percent of survey respondents that should have received salary payments in March 2022 through at least December 2023 had received all expected payments. At least 97 percent of respondents had not experienced two or more delays with payments. Source: GAO analysis of Deloitte reports. | GAO‑25‑107057 |

USAID also took steps to expand its oversight approach to address some scoping limitations of ongoing oversight efforts. For example, the agency took steps to enhance its spot checks of individual payments made by Ukraine that were later reimbursed with U.S. DBS funding. According to USAID officials, USAID directed Deloitte in 2023 to conduct surveys that could reach a larger population than its spot checks, based on feedback from USAID leadership. Deloitte conducted surveys pertaining to non-security sector government employee salaries and first responder salaries in 2024. Deloitte staff said they selected these two groups because they were the simplest population to survey, in part because their salaries are paid in full by the central government. In contrast, school employees with salaries reimbursed by U.S. DBS funding also receive part of their salary from local budgets, which are not reimbursed by U.S. DBS funding.

See table 1 for a comparison of the number of recipients Deloitte reached through its spot checks and surveys. Deloitte reported that the surveys provided an additional level of confidence that U.S. DBS had been received by its intended recipients.

|

Expenditure Category |

Total Population When Survey Conducted |

Survey Participants, as of October 2024 |

Individual Spot Checks Completed, as of December 2024 |

|

Non-security sector government employee salaries |

170,509 |

6,369 |

170 |

|

First responder salaries |

71,161 |

6,024 |

137 |

Source: GAO analysis of Deloitte reports. | GAO‑25‑107057

|

World Bank’s Listening to Citizens of Ukraine Surveys · Old age pensions – 97 percent · Social assistance benefits – 85 percent · Internally

displaced persons benefits – 91 percent The World Bank stated that these findings do not demonstrate any prolonged delays in payments. The World Bank plans to continue this method of monitoring on an ongoing basis. Source: GAO analysis of World Bank information. | GAO‑25‑107057 |

Between September 2022 and January 24, 2025, USAID also relied on Deloitte to review other oversight-related reports to determine whether Deloitte should make changes to its monitoring approach. For example, BDO conducted a financial audit of the PEACE project in 2023 for Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance, which Ukraine was required to obtain to meet a World Bank project requirement. In February 2024, USAID requested that Deloitte provide a summary of the BDO audit report to USAID. USAID and Deloitte officials further discussed the results of BDO’s report and determined that Deloitte did not need to alter its approach to its DBS-related work due to BDO’s lack of significant audit findings. According to Deloitte, staff also reviewed the published results from the World Bank’s “Listening to Citizens of Ukraine Surveys” and determined that the World Bank’s surveys complemented Deloitte’s survey work because they focused on different expenditure categories.

In addition, USAID recognized that while Deloitte’s monitoring work provided information about gaps in Ukraine’s processes for managing DBS, it did not officially constitute an audit that could provide a full assurance of the integrity of Ukraine’s use of U.S. DBS funding. As a result, USAID hired KPMG to conduct financial statement audits. In response to USAID instructions, KPMG initially designed financial statement audits of the three ministries receiving the largest shares of DBS funding: the Pension Fund of Ukraine, the Ministry of Education and Science, and the National Health Service of Ukraine, according to USAID officials.[20] The three audits cover four PEACE project expenditure categories: pensions, school employee salaries, higher education employee salaries, and healthcare worker salaries. As part of this work, KPMG said it plans to test a generalizable sample of payments to verify that the payments were eligible for reimbursement under the PEACE project.

USAID Contractor’s Technical Assistance to Ukraine Was Informed by Its DBS Oversight Work

Deloitte, under contract to USAID, provided technical assistance and other advisory support services to Ukraine that were informed by its review of Ukraine’s processes for managing U.S. DBS funding. According to Deloitte staff, USAID contracted Deloitte to review Ukraine’s processes for managing U.S. DBS funding, highlight areas requiring further attention, and offer recommendations to strengthen those areas. Deloitte’s DBS work was part of a broader contract with USAID to improve Ukraine’s public financial management processes that also included the provision of technical assistance and other support to Ukraine.

|

Deloitte’s Approach to Providing Technical Assistance For each of the four focus areas, Deloitte planned to complete the following four tasks: · Research: A comparative analysis of Ukraine’s processes and capabilities as they compare to other countries to identify areas for improvement. · Recommendations and engagement: Based on Deloitte’s research, it planned to develop recommendations for improvements and engage with Ukrainian stakeholders to identify priorities. · Capacity building: Provide support to relevant ministries to implement recommendations through creation of templates, trainings, and other efforts. · Reform efforts: In some cases, Deloitte determined that Ukraine would need to pass new legislation or undertake other reforms to address Deloitte’s recommendations for improving the four focus areas. Deloitte planned to help develop a road map with milestones to guide reform implementation, draft policies, and other efforts. Source: GAO analysis of Deloitte documents. | GAO‑25‑107057 |

Technical assistance. According to USAID and Deloitte officials, Deloitte provided technical assistance to Ukraine to improve its public financial management processes and help Ukraine implement some of the recommendations Deloitte made through its monitoring of DBS. Specifically, through its DBS-related monitoring efforts, Deloitte identified weaknesses in four areas, some of which pertained to systemic issues that could not be addressed in the short term: internal controls, internal audits, improper payments, and external audits. Deloitte staff described the technical assistance they provided or planned to provide to Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance and other relevant ministries to address these areas. For example:

· Internal controls. Deloitte completed several efforts to improve Ukrainian government managers’ ability to confirm the status of efforts to ensure government payments were used as intended. They drafted a questionnaire and a statement of assurance to help hold managers responsible for evaluating the status of the internal control environment within their offices. Deloitte also developed a brochure to help the Ministry of Finance explain the importance of these documents to various ministries.

· Internal audits. Deloitte proposed 55 recommendations aimed at strengthening Ukraine’s internal audit capacity and developed a roadmap for Ukraine’s implementation of these recommendations based on discussions with relevant officials from Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance.

· Improper payments. Deloitte provided a workshop on improper payments in December 2023 for over 70 Ukrainian non-security government employees to discuss how to identify, prevent, and mitigate improper payments in budget expenditures.

· External audits. Deloitte had planned to help Ukraine’s State Audit Service enhance its external audit capabilities by offering technical assistance, such as helping Ukraine to develop a risk-based approach to prioritize potential audits.[21]

Advisory support services. Deloitte also began providing advisory support services to Ukraine in 2024 to help Ukrainian ministries address DBS-related recommendations that could be implemented in the short term. In June 2024, we asked USAID about the extent to which Deloitte’s technical assistance could support Ukrainian ministries receiving DBS funds. These ministries include the Ministry of Education and Science, which oversees school employee salaries, and the Ministry of Social Policy, which manages social assistance payments. Prior to June 2024, Deloitte principally provided technical assistance to Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance, the primary government agency responsible for reporting to the World Bank for the PEACE project. In response to our inquiries, USAID officials and Deloitte staff said that USAID directed Deloitte to also provide advisory support services to other Ukrainian ministries involved in the management of DBS funding when requested. For example, the Ministry of Social Policy requested help addressing a Deloitte recommendation about verifying Ukrainians’ eligibility for internally displaced persons benefits. Deloitte had found that regional government entities only inspected the place of residence for approximately 0.5 percent of Ukrainians receiving internally displaced persons benefits. Deloitte reported this was not an efficient approach for monitoring eligibility requirements and recommended that Ukraine use geolocation information available in an existing Ukrainian mobile application. Deloitte planned to support the ministry in addressing this recommendation during fiscal year 2025 but could not provide this service due to the January 2025 stop-work order.

State Plans for Less DBS Oversight

Because of ongoing changes to U.S. foreign assistance programs, State has determined that the U.S. will rely on the World Bank and the KPMG contract for oversight of DBS funding. In accordance with an executive order issued in January 2025, USAID issued a stop-work order to almost all USAID-managed foreign aid projects worldwide, including Deloitte’s and KPMG’s contracts for DBS oversight-related work in Ukraine.[22] As a result, USAID’s DBS-related monitoring and oversight work was paused on January 25, 2025, according to USAID. This directive was part of a broader effort to reevaluate and realign U.S. foreign assistance. On February 26, 2025, USAID issued a termination notice to Deloitte instructing them to immediately cease all activities pertaining to their DBS-related contract, which had been set to run through April 2028.[23] USAID officials requested that USAID and State management reconsider the decision to terminate the Deloitte contract, but as of June 11, 2025, the requests had been denied.

The stop-work order for the KPMG award was canceled on March 5, 2025, but according to USAID, KPMG informed the agency that it would take at least 45 days to restart the contractor’s activities because the audit team engaged in the DBS audits had been assigned to another project and would require time to reassemble. The audit team said it resumed its audit of healthcare worker salaries in June 2025. However, KPMG could not resume its audits of (1) school employee and higher education salaries because it would be difficult to obtain necessary information from schools during the summer vacation period, and (2) pensions because KPMG was waiting for needed contract modifications to update the audit’s expected timeframe.

In March 2025, State and USAID notified Congress of their intent to undertake a reorganization of foreign assistance programming that would involve separating almost all USAID personnel from federal service, realigning certain USAID functions to State by July 1, 2025, and discontinuing the remaining USAID functions. In July 2025, the responsibility for the KPMG financial oversight contract had transitioned to State, according to State officials. The initial contract was set to end in September 2025 and, as of August 2025, it was unclear whether State would pursue adding an option year to continue the KPMG contract and whether State or other U.S. agencies would conduct any additional oversight of U.S. DBS funding provided to Ukraine.

According to USAID, the stop-work orders negatively affected (1) ongoing audit and oversight work and (2) ongoing efforts to help Ukraine strengthen internal controls and address related weaknesses observed during the oversight work. Specifically, the U.S. government did not conduct any independent monitoring of PEACE project funding from late January 2025 through early June 2025. A USAID official said that the abrupt disruption to USAID’s contracts severely limited the agency’s ability to effectively track and monitor DBS activity during this period.

Going forward, the U.S. government will not conduct the same level of oversight and support of U.S DBS funding as USAID had from 2022 through 2024. For example, KPMG’s scope of work is for financial statement audits covering DBS-related expenditures Ukraine made in 2022 and 2023, so it would not cover the use of funds appropriated in 2024 or the use of FORTIS Ukraine FIF funding. In addition, State officials said the agency does not plan to restart any ongoing monitoring and tracking of U.S. DBS funding, as Deloitte had previously done, noting that all the appropriated funds have already been disbursed. Moreover, Treasury does not have any planned oversight of FORTIS Ukraine FIF funding beyond relying on the World Bank to ensure the funding is used as intended, according to Treasury officials. Finally, Deloitte did not provide all the planned technical assistance and advisory support to Ukraine prior to the termination of their contract in February 2025, which was intended to help Ukraine improve its internal controls and processes for managing DBS funding. As a result, the U.S. will have less visibility into whether U.S. DBS funding to Ukraine is being used as intended.

USAID Did Not Analyze All Available DBS Expenditure Data and Provided Incomplete Reports to Congress

USAID did not regularly verify all available expenditure data that could have helped ensure that Ukraine used DBS funding as intended and informed oversight priorities. In addition, the information USAID included in its required reports to Congress on Ukraine’s use of this funding was incomplete. Following each disbursement of U.S. funding to Ukraine through the PEACE project, the World Bank provided USAID with aggregated summary data and Ukraine’s expenditure verification reports that included detailed data broken down by region or institution. For aggregated expenditure data, USAID either reviewed and requested clarification about the data itself or relied on Deloitte’s monitoring efforts to verify their accuracy. However, neither USAID nor Deloitte reviewed all the detailed expenditure data USAID received from the World Bank. Reviewing these data could have helped USAID identify data anomalies to inform oversight decisions and to help ensure Ukraine’s use of U.S. DBS funding was appropriate. USAID was also required to report to Congress on Ukraine’s use of DBS funding, but the reports were incomplete because USAID did not update its reporting to Congress once new data became available. By ensuring the accuracy of this information, USAID’s reports would provide Congress with better information about whether DBS funds were used as intended.

USAID Reviewed Some Data but Not Detailed Expenditure Data that Provided Greater Insight into Ukraine’s Spending

USAID or Deloitte Reviewed Aggregated Expenditure Data

According to agency officials, USAID followed an informal process for reviewing and requesting clarification about aggregated data from the World Bank. USAID followed this process through the first four Ukraine supplementals and then relied on Deloitte to complete this review for funding from the fifth supplemental. Both USAID’s and Deloitte’s processes were in line with the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, which state that managers should identify, analyze, and respond to identified risks so they are effectively mitigated.[24]

According to USAID, a USAID official reviewed summary information from the World Bank and requested clarification if any concerns were found. After each disbursement of U.S. funding to Ukraine through the PEACE project, the World Bank provided USAID with copies of expenditure verification reports submitted by Ukraine and aggregated summary data that included the expenditure categories and total amounts provided to reimburse Ukraine for each category. The USAID official reviewed the aggregated data to determine whether there were any potential duplicate payments to Ukraine, such as U.S. funding covering a month for a certain expenditure category that U.S. or another donor’s funding had already covered. For example, USAID asked the World Bank for clarification concerning potential duplicate reimbursements for first responder salary payments made in March 2023. The World Bank clarified that it only partially reimbursed Ukraine for these salaries in April 2023 and then reimbursed the remaining portion in a July 2023 disbursement. The official also reviewed the total amounts Ukraine paid for each expenditure category for each month to see whether the aggregate expenditure totals were roughly consistent with prior months. In one example, USAID followed up with the World Bank on expenditures for school employee salaries from June 2023 when officials noticed that the expenditures for that month were more than twice as large as prior months. The World Bank explained that school employees receive additional payments at the end of the school year and that they had discussed the larger June expenditures with Ukraine the prior year.

For monitoring DBS funded through the fifth supplemental, USAID primarily relied on its contractor, Deloitte, according to USAID officials. Agency officials said that their prior efforts to review the aggregate data in the expenditure verification reports duplicated Deloitte’s work to some extent. They pointed to Deloitte’s spot checks and tracking of U.S. DBS funding as efforts to ensure the accuracy of expenditure verification reports. For example, Deloitte staff said they separately tracked the use of U.S. DBS funding at the aggregate level to inform their monitoring efforts, based on updated information it received from Ukraine. To develop and update its tracker, Deloitte relied on documents from the Ukrainian government, such as receipts and withdrawal letters the Ministry of Finance submitted to the World Bank. The Ministry of Finance also provided Deloitte with updated data when it identified corrections.

USAID Did Not Review Detailed Expenditure Data that Provided Insight into Ukraine’s Spending

USAID did not analyze the detailed expenditure data the World Bank provided to identify potentially anomalous expenditures, to help ensure that Ukraine used DBS funding as intended, and to inform oversight priorities. According to USAID officials, the agency did not review the detailed expenditure data in the expenditure verification reports it received because Deloitte was performing spot check reviews of similar disaggregated data. Reports for 10 of the 13 categories included data broken down by region, while reports for the other three categories provided data broken down by institution. For example, the reports for first responder salaries included expenditures for the State Emergency Service units, while the reports for school employee salaries included expenditures by region and school type. This disaggregated data may provide helpful insights that may be harder to observe at the aggregate level. For example, a decrease in one disaggregated category could be balanced by an increase in another.

According to GAO’s Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, using data analytics to identify suspicious activity or transactions, including anomalies, outliers, and other concerns in data is a leading practice.[25] Conducting such analytics can enable programs to identify potential fraud or improper payments. Although USAID’s contractor, Deloitte, reviewed disaggregated data at the institutional and individual levels through its spot checks, Deloitte’s spot checks were not intended to review all the disaggregated data. In addition, neither USAID nor Deloitte completed any data analytics. The spot checks allowed Deloitte to monitor the use of DBS funding and identify potential discrepancies in expenditure reporting, but the sample size was small and non-representative, limiting its use for informing oversight priorities. Deloitte tested less than one percent of all payments, according to Deloitte staff.

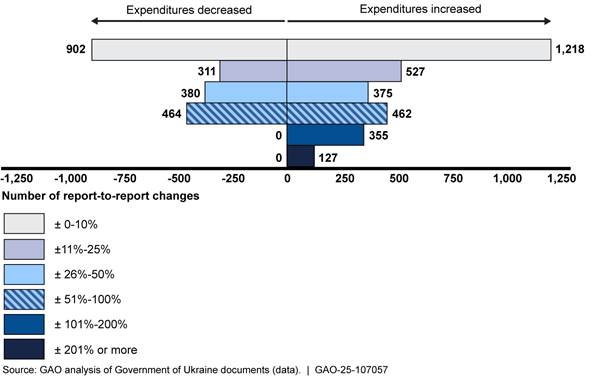

To demonstrate the value of analyzing the disaggregated data, we used several techniques for analyzing the detailed expenditure data we received. We identified anomalous report-to-report increases in expenditure amounts at regional and institutional levels that an agency responsible for continued oversight should further examine.[26] Specifically, we analyzed the detailed expenditure data in 78 expenditure verification reports covering Ukrainian expenditures incurred from March 2022 through August 2023.[27] These selected reports, which constitute our non-generalizable sample, contained 5,121 instances of report-to-report changes at a regional or institutional level. Through our analysis, we found that 42 percent of our sample (2,128 of 5,121) across all 13 expenditures experienced percentage changes of less than 10 percent, while 9 percent of our sample (482 of 5,121) showed report-to-report increases greater than 100 percent. Figure 6 shows the breakdown of percentage changes in report-to-report DBS expenditures for all 13 expenditure categories in our sample.

Figure 6: Breakdown of the Percentage Change in Report-to-report DBS Expenditures for Our Sample, from March 2022 to August 2023

Note: We reviewed all expenditure verification reports we received from USAID prior to October 2024, as well as additional reports USAID sent us in October 2024 for the higher education category, since we had previously received only one report for that category. For these reports, we compared the expenditures listed in each report and its prior report, which may have been from the prior month or multiple months earlier. Ukraine did not receive reimbursements through the PEACE project for each category every month.

As part of this analysis, we found some large percentage changes from report-to-report that merit further examination, while others had reasonable explanations. Some of the report-to-report percentage changes were in the thousands. For example, the largest percentage increase was an 86,802 percent increase (equal to $158,533) between February and March 2023 in Luhansk for social assistance to single parents. Upon reviewing this increase, we determined it would not require further examination because it likely resulted from changes Ukraine made to the processing of this type of assistance during this period.[28] Another large increase was a 2,474 percent increase (equal to $1,067,542) between April and June 2023 for salaries to non-security government employees working at the Ukraine Supreme Court. Although non-security government employees typically receive bonuses in June, this percentage increase was an outlier for June 2023 and merits further examination.

Ukraine included explanations for some of these changes in expenditures in overview reports that accompany the expenditure verification reports, and we took these into account as part of our analysis. For example, the May 2023 overview report for stipends provided to internally displaced persons explained that increases in expenditures were driven by delayed payments from the previous period because of Russian hostilities in certain regions. In addition, we found larger percentage increases for salaries of school employees at public schools below the university level between May 2023 and June 2023. In the accompanying overview report and during our meetings with Ukrainian officials, Ukraine clarified that teachers receive their salaries for the summer months in June. However, our analysis found that the percentage change for school employee salaries for June 2023 varied greatly across regions and school types, from negative 32 percent to 251 percent. This large distribution of changes in expenditures may benefit from further examination, including a review of how schools calculate and report summer salary payments. Through our analysis we determined that 161 of the report-to-report expenditure changes in our sample indicate anomalies, outliers, or other concerns in the data that merit further examination. For more details about our analysis see appendix III.

USAID and the World Bank have both taken steps to look into the results of our analysis. According to USAID officials and KPMG staff, USAID provided the lists of expenditures to KPMG and suggested that KPMG examine them as part of its ongoing audits of four of the 13 PEACE project expenditure categories: pensions, school employee salaries, higher education employee salaries, and healthcare worker salaries. As of July 2025, KPMG stated that it planned to follow up with the respective Ukrainian ministries about the expenditures we identified but did not have a timeline for doing so. At that time KPMG staff also told us that they lacked clarity on the timing and scope expectations for their DBS audit work. KPMG staff explained that they expected to obtain new direction from State because they had learned that State would be assuming responsibility for the KPMG contract on July 1, 2025. In addition, the World Bank shared the list of expenditures with Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance, which forwarded it to the relevant line ministries to provide explanations. As of June 30, 2025, Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance had provided the World Bank with initial explanations for many of the increases, as it awaited explanations from some of the other ministries. As of July 2025, the World Bank had not verified any of the explanations.[29] Upon initial review, we determined that some of the explanations provided were already factored into our analysis, such as expected summer pay and other benefits provided to school employees in May and June before the summer break. For these instances, the extent of the increases flagged in our analysis were well above average, even when we evaluated the expenditures for those months separately. In other cases the explanations provided were new and may be reasonable. According to the World Bank, the extent of the increases flagged in our analysis will benefit from further review.

Learning the cause for the unusually large expenditure increases would help inform oversight of the ongoing billions of dollars in disbursements of PEACE project funding from the U.S. contributions to the FORTIS Ukraine FIF. If some part of these unusually large expenditure increases is attributable to fraud, this would need to be addressed.

USAID’s Reports to Congress on DBS Funding Were Incomplete

USAID submitted some of the required reports to Congress on Ukraine’s actual use of and results achieved with DBS funding, but the reports were incomplete because USAID did not update its reporting to Congress once new data became available. The second through fifth Ukraine supplemental appropriations include a requirement for State or USAID to report on the uses of and results achieved with DBS funds.[30] Between September 2022 and May 2023, USAID submitted reports to Congress that addressed this requirement for three of the four Ukraine supplementals. However, USAID did not submit any reports addressing this requirement for the fifth Ukraine supplemental (see table 2). USAID officials told us in December 2024 that the agency had drafted a report. However, after the process of integrating USAID into State and other personnel changes at USAID began in 2025, USAID stated that officials with related knowledge were no longer available within USAID. Completing this reporting requirement in the fifth Ukraine supplemental would strengthen Congress’ oversight by providing more recent information about how Ukraine used U.S. DBS funding. These data can be used to inform future oversight decisions, whether for DBS or Ukraine funding more broadly.

Table 2: Congressional Reports Submitted Regarding Direct Budget Support (DBS) Funds and Select Reporting Requirements

|

Ukraine Supplemental and Section |

Agencies Responsible for Reporting on the Use of DBS Fundsa |

Number of Reports Submittedb |

|

Additional Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2022; Pub. L. No. 117-128, § 507(d), 136 Stat. 1211, 1223 [Second Supplemental] |

State or USAID |

1 |

|

Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2023; Pub. L. No. 117-180, Div. B, § 1302(c), 136 Stat. 2127, 2132 [Third Supplemental] |

State or USAID |

2 |

|

Additional Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2023; Pub. L. No. 117-328, Div. M, § 1705(c), 136 Stat. 5189, 5199 [Fourth Supplemental] |

State or USAID |

1 |

|

Ukraine Security Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2024; Pub. L. No. 118-50, Div. B, § 405, 138 Stat. 905, 916 [Fifth Supplemental] |

State or USAID |

0 |

Source: GAO analysis of the supplementals and USAID reports to Congress. | GAO‑25‑107057

Note: USAID also reported on the results of the use of DBS funding from the first Ukraine Supplemental, even though the agency was only required to report on proposed uses of State and USAID assistance funds provided through the Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-103, Div. N, 136 Stat. 776 (Mar. 15, 2022).

aUSAID, as the agency managing DBS funding, submitted the reports to Congress on the use of DBS funding.

bWhile State told us they cleared additional USAID reports for submission to Congress in response to the second through fourth supplementals, neither State nor USAID were able to provide this documentation to us, as of September 2025.

To report on Ukraine’s actual use of DBS funds appropriated through the first four Ukraine Supplementals, USAID officials said they used summary information from the World Bank. The summary information included the amount of funding the World Bank disbursed to Ukraine through the PEACE project, including total amounts for each expenditure category, based on Ukraine’s reimbursement requests. USAID then used this summary information to create a tracker of U.S. DBS funding provided to Ukraine. Agency officials used this internal tracker to report to Congress on the use of U.S. DBS funding, which, officials said was based on the data available to USAID up to the reporting date.

As previously discussed, Deloitte tracked U.S. DBS funding separately to inform its monitoring efforts. Deloitte relied on documents from the Ukrainian government to track U.S. DBS funding. Deloitte initially provided this tracker to USAID in January 2023 and provided USAID with updated versions following additional disbursements of U.S. DBS funding. USAID officials stated that Deloitte’s tracker was more accurate than its own tracking, which relied only on summary information from the World Bank.

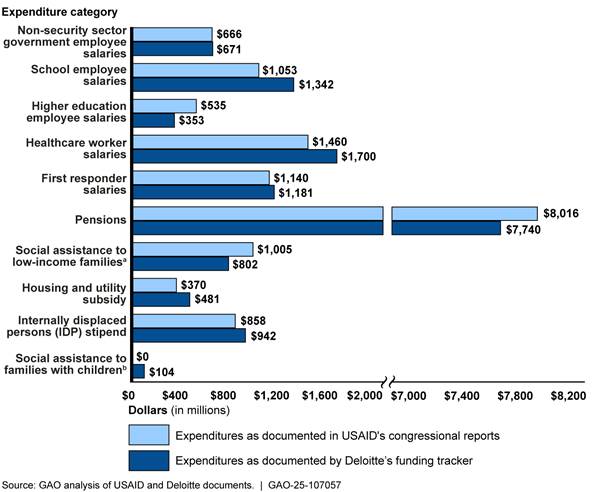

We compared the data in USAID’s congressional reports against Deloitte’s tracker covering U.S. disbursements of DBS made from late June 2022 through the end of May 2023 and identified some inconsistencies. Specifically, we identified 27 instances where USAID and Deloitte documented different expenditure amounts for the same month and category. For example, for disbursements made in late June 2022, USAID documented $471 million in reimbursed expenditures for civil government employee salaries while Deloitte documented $361 million. Figure 7 provides a comparison of the aggregate disbursement amounts that USAID and Deloitte reported for each category in their respective documents between June 2022 and May 2023, which covers funding from supplementals two and three and part of the funding from supplemental four. Overall, we identified approximately $212 million in differences between what USAID and Deloitte recorded across the 13 categories in the timeframe examined.

Figure 7: Comparing Aggregate Expenditures Reported by Different Sources by Expenditure Category, June 2022 to May 2023

aUSAID combined the disbursement totals for the (1) guaranteed minimum income and (2) disability benefit categories in its tracker, so we compared the tracking of this combination of categories across the two trackers.

bDeloitte combined the disbursement totals for the (1) birth grant and adoption grant, (2) social assistance to single parents, and (3) maternity benefit categories in its tracker, so we compared the tracking of this combination of categories across the two trackers.

USAID submitted some of its reports to Congress before Deloitte provided its tracker to USAID. USAID submitted four reports to Congress on the actual uses and results of DBS, including two before Deloitte made the tracker available to USAID—September 2022 and November 2022—and two after Deloitte’s tracker was available in January 2023 and May 2023. According to USAID, they continued to use their internal tracker as the basis for the January 2023 and May 2023 reports to maintain consistency with how the previous reports were prepared and submitted to Congress.

In November 2024, USAID officials stated that they believe the most recent version of the Deloitte tracker is the most accurate accounting of DBS funds, because Deloitte relied on updated information and corrections provided by Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance. According to USAID officials, the DBS expenditure data they received from the World Bank was typically updated later because Ukraine identified and corrected reporting errors or provided new data. Whereas USAID relied on the data available at a specific point in time to report to Congress on the use of funds, Deloitte used the most recent available data for tracking the use of U.S. DBS funding. USAID officials noted that differences between USAID’s reports to Congress and Deloitte’s tracker may be due to timing, data aggregation differences, and data source differences.

Given that USAID officials consider Deloitte’s tracker to be more accurate and the differences between this tracker and the information reported to Congress, USAID’s reports to Congress are likely inaccurate now. However, USAID did not submit updates to its prior reporting to Congress on Ukraine’s use of U.S. DBS funding even though it had access to updated information throughout 2023 and 2024. USAID said in June 2025 that it would work towards compiling and submitting updated reports to Congress to provide current information about the use of DBS funding, but it did not provide a timeframe for doing so.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that agency managers should use quality information and should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[31] Ensuring that quality information was communicated externally could have improved the accuracy of its reporting to Congress, thereby providing Congress greater confidence that DBS funds were used as intended.

USAID Contractors Have Identified Weaknesses in Ukraine’s DBS Processes but USAID Has Not Assessed Their Risk

USAID Contractors Have Identified Weaknesses in Ukraine’s DBS Processes

USAID’s contractors, Deloitte and KPMG, have identified weaknesses in Ukraine’s processes for managing DBS funding. Deloitte identified weaknesses in Ukraine’s internal controls and processes for managing U.S. DBS funding and made recommendations to address these weaknesses. KPMG was unable to complete its audits as of July 2025, but it reported to USAID on several challenges it has faced in auditing DBS funding in Ukraine.

Deloitte

Deloitte’s monitoring efforts included a review of Ukraine’s internal controls and processes for managing DBS funding. This review identified a variety of weaknesses and resulted in 56 recommendations to Ukraine as of August 2024.[32] To help Ukraine address these weaknesses, Deloitte developed and grouped recommendations into five categories. Some of the recommendations addressed explicit process weaknesses in specific expenditure categories, while other recommendations addressed larger processes across multiple categories. See table 3 for more information about these recommendations.

Table 3: Deloitte Recommendations to Improve Ukraine’s Processes for Managing Direct Budget Support, by Category, as of August 2024

|

Recommendation Category and Description |

Number of Recommendations |

Number Completed |

Expenditure Category/s |

Example of Deloitte Recommendation to Ukraine |

|

Expense controls: Findings related to processes and controls aimed at decreasing the risks of reporting improper and ineligible expenditures. |

19a |

6 |

· Healthcare worker salaries · First responder salaries · Internally displaced persons stipend · School employee salaries · Disability benefit · Pensions |

Improve processes for identifying irregularities, such as improper payments, that enable Ukraine to analyze the payments, determine the root causes, and develop a response to decrease irregular payments. |

|

Hotlines: Findings related to the communication channels and related infrastructure that qualified parties may use for reporting defined categories of concerns. |

18a |

0 |

· Not category specific |

Amend laws related to the protection of personal data and complaints individuals submit via hotlines in ways that would facilitate further cooperation with informants. |

|

IT general controls: Findings related to a set of security measures and protocols that ensure integrity, reliability, and accuracy of information systems within an organization. |

11 |

2 |

· Not category specific |

Develop processes for assessing hardware and software for required updates to ensure sufficient protection against cyber risks. |

|

Reporting controls: Findings related to Ukraine’s processes and controls over accurate reporting of information on DBS at different stages. |

6a |

4 |

· Healthcare worker salaries · School employee salaries · Non-security sector government employee salaries |

Ensure that appropriate instructions for determining the number of eligible employees are in place, such as guidance about ineligible employees that should be excluded from these calculations, to mitigate inconsistencies in reporting. |

|

Reporting transparency: Findings related to the clarity of presentation of information in Ukraine’s expenditure reports. |

2 |

2 |

· Healthcare worker salaries · School employee salaries · Non-security sector government employee salaries |

Clarify the differences between the column headings in the expenditure reports for certain salary categories to ensure the types of data reported for salary expenditures are consistent across categories. |

Source: GAO analysis of Deloitte reports. | GAO‑25‑107057

aDeloitte made several recommendations to Ukraine in its interim report in August 2024. These recommendations pertained to expense controls (two recommendations), hotlines (seven), and reporting controls (one). Since these were identified in Deloitte’s interim report, Deloitte did not have an opportunity to report on Ukraine’s efforts to address these recommendations before a stop-work order and subsequent cancellation of its contract in 2025.

According to Ukrainian officials we met with in Kyiv, they generally agreed with Deloitte’s recommendations, but noted that the effort needed to implement them varied. Some recommendations could be addressed in the short-term. For example, Deloitte found that local school officials did not adequately segregate duties related to maintaining records of working hours, submitting employee timesheets, verifying the accuracy of records, and compiling related documentation. To address this weakness, Deloitte recommended in July 2023 that the Ministry of Education and Science send a letter to the Departments of Education of local governments clarifying the need to segregate duties in the job descriptions of school staff, which the Ministry of Education and Science did in June 2024.

Other recommendations pertain to systemic issues, such as weaknesses related to internal controls, internal audits, and risk management, and require sustained efforts to address, according to Deloitte staff. For example, in July 2023, Deloitte recommended that the Ministry of Health develop measures to reduce the potential for payments to fictitious employees and patients. In August 2024 Deloitte reported that, to address this recommendation, the Ministry of Finance planned to develop an IT platform to verify the validity of information and documents entered in the electronic medical system.

KPMG

KPMG has not completed any of its planned audits, and experienced challenges that led to delays in their work. KMPG started their work in January 2024 and was initially scheduled to complete the first audits in 2024. However, KPMG encountered several challenges that led to delays, such as problems with the quality of data and documentation available. For example, KPMG raised concerns that the 2022 healthcare worker salary data contained errors related to the calculation of salary taxes, and KPMG staff said they could not start the audit of the National Health Service of Ukraine without corrected data. In addition, KPMG struggled to obtain documents from medical and educational institutions located in or near the frontlines. KPMG’s work was then further delayed by a January 2025 stop-work order.

In the interim, KPMG submitted quarterly performance reports to USAID that provided updates based on its ongoing work. In these reports KPMG identified differences between the data it analyzed and the data provided by Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance. For instance, KPMG identified a $777,000 discrepancy when it analyzed sample data for school employee salaries for January 2023 and March through June 2023. KPMG attributed these discrepancies to both technical and human errors, primarily related to confusion around new accounting techniques. In 2023 the Ministry of Education and Science issued new guidance for schools to transition from cash-based to accrual-based accounting for PEACE project reporting, according to KPMG.[33] Although the Ministry of Education and Science and the Ministry of Finance claimed that they had identified and subsequently corrected the discrepancies prior to KPMG’s audit, the ministries were unable to provide KPMG with a detailed breakdown of the misstatements identified and corrected by month. As a result, KPMG concluded that Ukraine may have made some corrections in months for which Ukraine was not reimbursed by U.S. DBS funding, according to KMPG’s reporting.

USAID Monitored Recommendation Status, But Did Not Assess Related Risks

USAID had a process in place to monitor Ukraine’s implementation of Deloitte’s recommendations for addressing weaknesses. However, neither USAID nor Deloitte assessed these weaknesses to determine which present the highest risk to Ukraine’s management of DBS funding. USAID officials told us they relied on Deloitte to monitor Ukraine’s implementation of these recommendations. USAID officials and Deloitte staff told us they met with relevant Ukrainian ministry officials to discuss Deloitte’s recommendations, and Ukrainian officials determined how and when to address the recommendations based on their capacity. When Ukrainian officials requested it, Deloitte would work with Ukrainian officials to develop solutions to address certain recommendations, according to Deloitte staff. Deloitte also periodically requested updates from Ukraine on these recommendations. As of August 2024, Deloitte determined that Ukraine had implemented 14 of 46 recommendations it had made previously and that work on another 26 recommendations was in progress.[34]

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving the defined objectives. This includes analyzing the identified risks to estimate their significance, which provides a basis for responding to the risks.[35] Further, Office of Management and Budget’s guidance on enterprise risk management and internal controls identifies the importance of developing a risk profile that ranks fraud or internal control risks to inform the prioritization of limited resources.[36]

However, neither USAID nor Deloitte assessed the weaknesses or related recommendations to determine which weaknesses present the highest risk to managing and protecting DBS funding. Deloitte staff explained that the nature and type of weaknesses vary significantly and view all their recommendations as important. Moreover, USAID did not ask Deloitte to identify priority recommendations. According to USAID, officials reviewed Deloitte’s recommendations, but the agency did not prioritize the recommendations because they deemed all the recommendations useful for improving Ukraine’s management of DBS funding. USAID stated that because it expected Ukraine to address all the recommendations, there was no need to prioritize them. They further explained that the agency would have needed to reprioritize recommendations every six months because Deloitte identified new weaknesses in semi-annual reports, which they said would result in delays in addressing the weaknesses.