CRIMINAL INVESTIGATORS

Program-Wide Evaluations and Clear Oversight Responsibilities Could Enhance Training Programs

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Kristy E. Williams at williamsk@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107063, a report to congressional committees.

Program-Wide Evaluations and Clear Oversight Responsibilities Could Enhance Training Programs

Why GAO Did This Study

Criminal investigators at MCIOs investigate serious and complex crimes involving military service members and civilian personnel. An independent committee, established by the Army in response to the disappearance and murder of a Fort Hood, Texas, soldier, identified deficiencies in criminal investigators’ experience and training to handle complex cases and accomplish investigative missions.

Senate Report 118-58, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, includes a provision for GAO to review criminal investigators’ training. This report assesses the extent to which (1) MCIOs provide and track the completion of investigative training, (2) MCIOs evaluate investigative training effectiveness, and (3) DOD oversees criminal investigative training. GAO reviewed relevant policies, analyzed data and documents on MCIO training, and interviewed cognizant MCIO, DOD, and DHS officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making a total of nine recommendations, seven to DOD and two to DHS. They include developing and issuing guidance for MCIOs to track criminal investigative training completion; developing plans for program-wide training evaluations; and finalizing guidance designating DOD responsibilities for investigative training. DOD and DHS concurred with GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

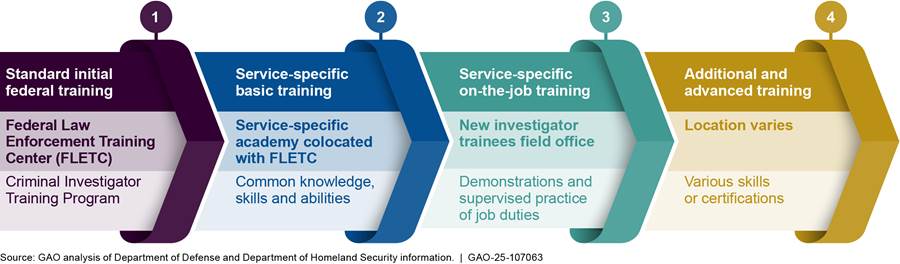

Criminal investigators at military criminal investigative organizations (MCIO) must complete federal and service-specific criminal investigative training (see figure). MCIOs include the Department of the Army Criminal Investigation Division, Naval Criminal Investigative Service, and Air Force Office of Special Investigations—within the Department of Defense (DOD)—as well as the Coast Guard Investigative Service within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

MCIOs track the completion of some service-specific and advanced criminal investigative training to determine investigators’ progress through training. However, MCIOs do not have guidance with requirements or procedures to track completion of criminal investigative training. As a result, MCIOs may not have full information on investigators’ completed training. Tracking training completion ensures compliance with requirements and allows organizations to track progress consistent with identified goals and objectives. Without such information, MCIOs may not have complete information on the qualifications met or retained by their criminal investigators.

MCIOs evaluate their service-specific basic training courses through periodic course reviews and feedback collected from participants and their supervisors. However, MCIOs do not conduct program-wide evaluations to determine the effectiveness of their criminal investigative training. Plans for regular program-wide evaluation with time frames for review, measures of effectiveness, and documented results would provide MCIOs with the ability to demonstrate how their criminal investigative training programs develop criminal investigators and contribute to MCIOs’ missions.

DOD has multiple offices with responsibilities for law enforcement and criminal investigative programs. However, DOD does not regularly monitor and evaluate criminal investigative training programs because responsibility for oversight remains unclear. Without final guidance designating DOD offices’ responsibilities for criminal investigative training programs, DOD oversight of the MCIOs’ investigative training programs may be incomplete, unclear, or delayed. This could limit DOD’s ability to support MCIOs as they develop their programs to ensure criminal investigators are fully qualified to carry out their investigative missions.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

AFOSI |

Air Force Office of Special Investigations |

|

CGIS |

Coast Guard Investigative Service |

|

CID |

Department of the Army Criminal Investigation Division |

|

CITP |

Criminal Investigator Training Program |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

FLETC |

Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers |

|

IG |

Inspector General |

|

MCIO |

Military Criminal Investigative Organization |

|

NCIS |

Naval Criminal Investigative Service |

|

USD(I&S) |

Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

August 22, 2025

The Honorable Roger F. Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The proper handling of criminal investigations involving service members is critically important to protecting the safety and security of both military and federal civilian personnel and ensuring the operational readiness of military forces. The responsibility for investigating serious and complex crimes involving military and civilian personnel—including crimes such as homicide or sexual assault—falls to federal criminal investigators from the military criminal investigative organizations (MCIO). These include the Department of the Army Criminal Investigation Division (CID), the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), and the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) under the Department of Defense (DOD), and the Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS) under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).[1] Effective criminal investigation training for these investigators is essential to help ensure that such investigations are completed in a professional manner.

In July 2020, in response to questions and concerns about command climate and culture raised during the investigation into the disappearance and murder of Army Specialist Vanessa Guillèn, the Secretary of the Army appointed the Fort Hood Independent Review Committee. The Committee was charged with investigating the command climate and culture at Fort Hood, Texas, and their effects on service members’ safety, welfare, and readiness. Among other things, the Committee examined issues of criminal investigations. In its final report issued in November 2020, the Committee stated that Army criminal investigators at the installation lacked sufficient experience and training to handle complex cases that, among other things, adversely affected the accomplishment of its investigative mission.[2] These findings, along with concerns raised in a congressional hearing, raised questions about the preparedness of criminal investigators across the military services.

Senate Report 118-58, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, includes a provision for us to review the investigative training that MCIO criminal investigators receive.[3] This report addresses the extent to which (1) MCIOs provide and track completion of investigative training for criminal investigators, (2) MCIOs evaluate the effectiveness of investigative training for criminal investigators, and (3) DOD oversees investigative training provided to criminal investigators.

To address these objectives, we reviewed training-related policy, guidance, and plans by DOD, DHS, and the military services as well as training opportunities for criminal investigators from each of the MCIOs. We also interviewed relevant DOD, DHS, and military service officials about training requirements, delivery, tracking, evaluation, and oversight. We analyzed information from relevant inspectors general (IG) offices about oversight of MCIOs’ criminal investigative programs including training for criminal investigators. We also conducted a site visit to the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers (FLETC) in Glynco, Georgia, where most initial federal law enforcement training occurs and where MCIOs conduct service-specific follow-on and some advanced training. Our review and analysis focused on criminal investigative training provided to MCIOs’ criminal investigators. We did not review other personnel training requirements that may apply to criminal investigators. See appendix I for additional information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

MCIO Roles and Responsibilities

Each MCIO serves as a federal law enforcement agency with jurisdiction within its respective military service. The MCIOs conduct federal-level criminal investigations for serious and complex crimes, or felonies, among other criminal investigative roles.[4] These investigations would typically include potential crimes involving military service members or involving civilian personnel located at facilities that are under the responsibility of one of the armed forces. CID, AFOSI, and CGIS use both military and civilian personnel as criminal investigators. According to information provided by MCIO officials for fiscal year 2024, military personnel comprised the majority of CID, AFOSI, and CGIS criminal investigators. The NCIS criminal investigators were almost exclusively civilian personnel, according to NCIS information.

MCIOs within DOD operate under the direction and control of the secretary of the respective military department and the MCIO’s director or commander.[5] Additionally, section 408 of title 5, U.S. Code, part of what is commonly referred to as the Inspector General Act of 1978 as amended, states that the DOD IG shall develop policy, monitor and evaluate program performance, and provide guidance with respect to all DOD activities relating to criminal investigation programs.[6] Since April 2023, the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security (USD(I&S)) was assigned responsibilities for law enforcement as a principal staff assistant. These responsibilities include oversight of the development, implementation, and integration of DOD’s law enforcement policy (separate from those policies under the DOD IG’s responsibilities), mission objectives and training requirements, operating guidance, and resourcing.[7] Also, CGIS operates as an independent entity under the Coast Guard, a component of DHS. Unlike the DOD IG, the DHS IG does not have specific statutory responsibility for the Coast Guard’s criminal investigation program.

CID

CID investigates felony crimes of serious, sensitive, or special interest to support commanders and preserve Army resources and collects and provides criminal intelligence while working to prevent crimes that impact the Army’s operational readiness. CID also provides its investigative information to the responsible command or a U.S. attorney as appropriate. The Army established CID as a major command in 1971. Its first civilian director assumed responsibility in September 2021 along with the organization’s renaming and redesignation as a direct reporting unit to the Under Secretary of the Army. CID established a training division and is also building a training academy located at FLETC.

NCIS

NCIS is the Department of the Navy’s civilian federal law enforcement agency responsible for investigating felonies and major crimes, preventing terrorism, and supporting commands for the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps. It provides its results to appropriate commands or prosecutorial authorities. A civilian law enforcement professional leads NCIS and reports directly to the Secretary of the Navy. NCIS’ Code 12 Training and Workforce Development Directorate administers its criminal investigative training program and the NCIS Training Academy located at FLETC.

AFOSI

AFOSI is the Department of the Air Force’s federal law enforcement agency responsible for conducting independent criminal investigations, criminal investigative activities, and specialized investigative and force protection support on behalf of the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force. The AFOSI Commander executes AFOSI’s mission under administrative guidance and oversight of the IG in the Office of the Secretary of the Air Force. The Air Force Special Investigations Academy, located at FLETC, manages training for AFOSI and conducts criminal investigative courses at FLETC and other sites.

CGIS

CGIS’ mission is to support and protect Coast Guard personnel, operations, and assets. CGIS conducts criminal investigations and other law enforcement activities in support of its mission. Its director serves as the senior federal criminal investigative executive within the Coast Guard. CGIS is the Coast Guard’s criminal investigative branch and falls under the Coast Guard’s Deputy Commandant for Operations. The Coast Guard is a component of DHS but can be transferred to operate as a DOD military service within the Department of the Navy under certain circumstances. CGIS Training Division, located at FLETC, administers its criminal investigative training for criminal investigators.

FLETC

FLETC is the federal government’s primary law enforcement training center. As such, FLETC’s mission is to train and support the training of federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement officers and international partners that are responsible for enforcing laws, treaties, and regulations within the United States and abroad. FLETC, a component of DHS, conducts basic criminal investigative training for most of the federal government at its main campus in Glynco, Georgia.[8]

MCIOs Require Initial and Service-Specific Criminal Investigative Training, but Generally Do Not Track All Training Completion

MCIOs Require New Criminal Investigators to Complete Initial Criminal Investigative Courses, and Additional Training Varies

MCIOs require their military and civilian criminal investigators to complete a standard federal initial training, most often the Criminal Investigator Training Program (CITP), provided by FLETC.[9] MCIOs also require that their criminal investigators complete service-specific basic and on-the-job training, which is provided by and varies across the military services. Most MCIOs do not require additional or advanced criminal investigative training, but MCIOs provide additional and advanced courses that can be given or assigned to criminal investigators based on an individual field office’s needs or a criminal investigator’s interests.

FLETC also offers additional and advanced criminal investigative training beyond its initial training, such as courses on digital evidence collection, advanced forensic techniques for crime scenes, and advanced interviewing for investigators. MCIOs’ criminal investigators can participate in this training as well as identify and participate in relevant training provided by other law enforcement agencies or training providers.[10] See figure 1 for the progression of criminal investigative training for MCIOs’ criminal investigators—collectively referred to as the criminal investigative training program for the purposes of this review.

Figure 1: Criminal Investigative Training for Military Criminal Investigative Organizations’ Criminal Investigators

Standard Initial Federal Training

Each MCIO requires its new criminal investigators, with limited exceptions, to attend the federal government’s initial course—CITP—for civilian and military criminal investigators.[11] CITP is a FLETC-administered, 13-week training course on the skills and knowledge necessary for federal criminal investigators. In fiscal year 2024, FLETC graduated 1,937 students through the program of whom 275 were from the MCIOs. The training provides instruction on basic federal law enforcement skills and other topics through lectures, labs, exams, and practical exercises. During the course, students participate in practical exercises such as interviewing suspects, delivering courtroom testimony, and operating vehicles during emergencies. Instructional topics include behavioral science, counterterrorism, cyber, firearms, investigations, leadership, legal concepts and issues, and physical and tactical techniques (see table 1).

|

Training category |

Selected training topics |

|

Behavioral science |

· Cognitive interview · Cross cultural communications · Interviewing for criminal investigators · Suspect interview |

|

Counterterrorism |

· Operational security · Terrorism · Transportation Safety Administration regulations on flying armed |

|

Cyber |

· Electronic surveillance techniques · First responders to digital evidence · Introduction to mobile device investigations |

|

Driver education |

· Cognitive driver training: crash avoidance · Emergency vehicle operations · Non-emergency vehicle operations |

|

Enforcement operations |

· Active threat response tactics · Basic tactics · Human trafficking · Officer safety and survival |

|

Firearms |

· Law enforcement handgun · Firearms safety rules and regulations · Live fire cover · One hand survival techniques |

|

Investigative operations |

· Description and identification process · Execution of a search warrant · Informants · Prisoner processing · Recognition of clandestine labs · Undercover operations |

|

Leadership training |

· Ethical behavior and core values |

|

Legal |

· Courtroom testimony · Federal court procedures · Fourth Amendment · Officer liability · Use of force |

|

Physical techniques |

· Baton control techniques · Introduction to physical training · Lifestyle management · Tactical medical |

Source: GAO summary of Federal Law Enforcement Training

Centers’ (FLETC) information. | GAO‑25‑107063

Some MCIOs may not require CITP for criminal investigators who have completed an equivalent course. CID officials stated that, prior to fiscal year 2024, unlike other MCIOs, CID’s criminal investigators did not generally attend CITP for their initial training. Instead, they attended initial and service-specific training at the U.S. Army Military Police School located at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. According to CID officials, as part of a CID transformation beginning in 2021, the organization initiated changes in its training program. These changes included that new civilian criminal investigators attend CITP in line with practices used by other MCIOs and federal law enforcement agencies. However, Army officials stated that new military criminal investigators will continue to attend initial training at the U.S. Army Military Police School due to funding considerations.[12]

Service-Specific Basic Training

Following completion of CITP, criminal investigators advance to service-specific basic training. Service-specific basic training for criminal investigators includes coursework on the respective MCIO’s operating context, including applicable regulations, policies, report writing, and case file navigation practices. This training builds on CITP’s introductory instruction and practical exercises and offers more advanced skills development on topics relevant to work at the MCIOs. According to FLETC officials, most MCIOs coordinate with FLETC to develop and provide curriculum that is relevant to the MCIOs’ specific missions and training requirements. Although some MCIOs share training titles, service-specific basic training courses differ in length and agency context (see table 2).

Table 2: Military Criminal Investigative Organizations’ Service-Specific Basic Training, Selected Topics (fiscal year 2024)

|

Organization |

Course name |

Selected training topics |

Program length (weeks) |

|

Department of the Army Criminal Investigation Division |

Special Agent Basic Training |

Defensive tactics Military law Sexual assault investigations |

8 |

|

Naval Criminal Investigative Service |

Special Agent Basic Training |

Crime scene management Death scene investigations Organization and mission |

12 |

|

Air Force Office of Special Investigations |

Basic Special Investigators Course |

Investigative jurisdiction Military law Organization and mission |

8 |

|

Coast Guard Investigative Service |

Special Agent Basic Training Program |

Case management system Crime scene documentation Mobile device investigations |

8 |

Source: GAO analysis of agency documents. | GAO‑25‑107063

According to CID officials, as a result of changes to CID’s initial training requirements for its civilian criminal investigators, CID piloted a service-specific basic training course at FLETC. CID officials stated that after feedback from three pilot courses conducted during 2024, CID will provide a finalized service-specific basic training course beginning in fiscal year 2025.

In addition, for criminal investigators with relevant experience, some MCIOs offer adapted service-specific basic training. For example, AFOSI offers a 2-week virtual version of the course to criminal investigators with prior federal law enforcement experience. CGIS also provides a shortened course to reservists who serve as criminal investigators because they must have prior law enforcement experience.

Service-Specific On-the-Job Training

Supervised on-the-job training, which typically takes place at a criminal investigator’s assigned field office, follows completion of service-specific basic training. In general, during on-the-job training, supervisors work with criminal investigators to apply classroom learning to their daily work and provide them with guidance, including demonstrations of job duties. MCIOs consider on-the-job training completed by criminal investigators when they demonstrate aptitude in a service-specific list of core skills over a service-determined period of time (see table 3).

Table 3: Military Criminal Investigative Organizations’ Service-Specific On-the-Job Training, Selected Topics (fiscal year 2024)

|

Organization |

Program name |

Selected training tasks and tests |

Program length (weeks) |

|

Department of the Army Criminal Investigation Division |

Special Agent Field Training Program |

Authority and jurisdiction Evidence processing Policies and procedures |

16 |

|

Naval Criminal Investigative Service |

Field Training Evaluation Program |

Digital literacy Interviewing victims and witnesses Search and seizure |

9 |

|

Air Force Office of Special Investigations |

Probationary Agent Training Program |

Case initiation Rules of evidence Use of force |

64 |

|

Coast Guard Investigative Service |

Field Training Evaluation Program |

Interviewing and interrogation Military search authorization Special agent safety |

16 |

Source: GAO analysis of agency documents. | GAO‑25‑107063

When they finish this on-the-job training, criminal investigators have completed the initial and basic training required and provided by CID, NCIS, and CGIS. After three short additional courses, the same is true for AFOSI’s criminal investigators.

Additional and Advanced Courses

After completing on-the-job training, criminal investigators can attend a variety of additional and advanced training that FLETC, MCIOs, or other training providers offer. Training participation can vary depending on mission or developmental needs, or sometimes on a criminal investigator’s interests or professional goals.

Two MCIOs have established additional training requirements for criminal investigators.

· AFOSI requires all criminal investigators to attend three additional AFOSI-administered courses: (1) an online training to familiarize criminal investigators with their unit’s specific responsibilities, (2) a course with initial exposure to counterintelligence topics, and (3) a mission-specific course.

· CID provides a Special Agent Refresher Training Program, revised for fiscal year 2025, that is, according to officials, for criminal investigators with 3 to 5 years of experience. CID officials explained that the training will provide initial exposure or a knowledge refresher on relevant topics to criminal investigators who did not attend CITP.

Each MCIO also offers opportunities for criminal investigators to attend advanced courses in criminal investigative topics. Through the MCIO training academies located at FLETC, MCIOs provide advanced training in topics such as forensics, tactics, and crime scene investigation. FLETC also offers advanced training in a variety of areas, such as case organization and presentation, money laundering and asset forfeiture, and leadership practices. Generally, MCIOs do not require criminal investigators to attend advanced courses, except those that are necessary for obtaining certifications or acquiring specialized skills.

MCIOs may also develop or provide additional training for criminal investigators to respond to needs or requests throughout the organization. For example, NCIS officials stated that field offices can request training from a mobile training team on topics or skills specific to that office’s needs. Similarly, AFOSI officials said that local or regional managers and experts discuss investigative trends and may identify training needs for relevant personnel. CID officials stated that, in addition to developing its MCIO academy at FLETC, the organization may continue to provide some training at the U.S. Army Military Police School. CGIS officials said that they update CGIS’ annual training plan based on input from managers and field personnel and can develop additional training if needed.

MCIOs Do Not Track Completion of All Criminal Investigative Training

MCIOs track the completion of some service-specific and advanced criminal investigative training to determine criminal investigators’ progress through training on skills relevant for conducting criminal investigations.[13] According to MCIO officials, the MCIO training academies—which conduct service-specific and advanced training at FLETC and other geographically separated sites—can track whether a criminal investigator has attended an MCIO-administered course, participated in an exercise, or fulfilled course requirements. AFOSI and CGIS officials stated, for example, that their academies track the completion of student coursework. In addition, MCIO staff located at FLETC can access information on the completion of FLETC-provided training through FLETC’s student administrative and scheduling system. However, MCIOs may not have full information on training completed by investigators outside of FLETC- or MCIO-administered courses, and some information on training completion may be maintained only by MCIOs’ academies or local offices.

According to MCIO officials, some MCIO academies maintain records on their criminal investigative training to meet course accreditation standards, and some MCIOs are developing information systems to track and record training. To track and record information on service-specific and advanced criminal investigative training, MCIOs use or plan to use information systems as well as other methods. Specifically:

Army. According to CID officials, CID uses a temporary database to retain criminal investigator training records until its permanent solution, CID’s adaptation of an Army-wide database, is finalized. According to CID officials, the database was pre-launched to several field offices in the fall of 2024 to test and review, and officials anticipate that it will be fully operational by late 2025. However, CID officials said that CID will not have a single system to track training for its investigators until then. In addition, Army officials said that the database will initially be limited to tracking Army mandatory training. According to CID officials, having a permanent database to track training will help decision makers determine how many criminal investigators have completed required training and help Army officials make informed budget decisions on the number of courses offered.

Navy. NCIS officials stated they track criminal investigative training provided by NCIS to maintain accreditation records. They also stated that the academy records completion of service-specific basic training in the Navy’s service-wide database system for personnel. According to NCIS officials, managers in field offices can access data from the Navy-wide system to determine if an individual is complying with course requirements. Officials stated that criminal investigators can also use the Navy-wide system to update their training records for any training or certification. Officials said that, in those instances, field training coordinators certify training for criminal investigators in the system when they provide proof that the training has been completed. However, NCIS may not have full visibility of service-specific or other training completed by criminal investigators unless investigators consistently provide proof and update their individual records, or unless local training coordinators certify all information on training completion by investigators.

Air Force. Similarly, AFOSI officials said that training components track service-provided training internally and sometimes use service-wide systems to record completion. According to AFOSI officials, AFOSI is developing a system as a central repository for criminal investigator training records. The system was launched in July 2024 but is not yet operating at its full capacity. Officials said that while records from its previous system are being transferred, they are maintaining copies of the data in spreadsheet form to ensure quality of the information. Officials stated that criminal investigators can also use the Air Force’s personnel system to record any training completion in their individual records, with validation from local managers. However, AFOSI officials said that since the Air Force’s system is not designed to automatically record information on training completion, local managers must rely on criminal investigators to properly update their training records in a timely manner to receive validation and ensure that information on training completion is recorded. AFOSI officials also said that managers in the field offices maintain records of criminal investigators’ training and graduation status and, in meeting accreditation requirements, the AFOSI academy maintains training records for 30 years.

Coast Guard. According to CGIS officials, CGIS’ training division is currently using a temporary program application to track training and allow end users, such as supervisors, to manually enter information on courses or tasks, such as on-the-job training requirements, that criminal investigators have completed. However, CGIS officials may have limited visibility of criminal investigators’ training completion because the temporary program application relies on manual entries. According to CGIS officials, CGIS plans to develop a new, permanent information system over the next 18 to 24 months, and they expect the new system to replace the current temporary tracking application.

MCIOs have taken steps to track the completion of some training, but they may not fully capture completion of criminal investigative training. Specifically, some service-specific or advanced training that criminal investigators complete may only be recorded in service-wide systems when MCIOs request the information. For example, CGIS officials stated that local coordinators provide information on a criminal investigator’s advanced level training completion upon request because this information is not readily available in their service-wide systems. In addition, AFOSI officials said that program managers are responsible for tracking external or advanced training completed by criminal investigators, which may limit this information’s availability outside of AFOSI. Other advanced or field-level training that criminal investigators complete may only be tracked or maintained in an MCIO’s systems if a field or unit leader or criminal investigator enters information.

For example, NCIS officials said that local coordinators are responsible for maintaining information on criminal investigators’ participation and completion of the on-the-job training program in NCIS’ field evaluation training program software system. Moreover, in some instances, field offices may maintain information on completion of on-the-job training tasks by criminal investigators but may not record that information in the MCIO’s systems unless requested. As a result, MCIOs may not have a full understanding of the investigative training that criminal investigators have completed. Federal internal control standards state that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives. Among other things, this principle calls for management to identify information requirements and process the data obtained into quality information—information that is appropriate, current, complete, and accurate.[14]

The MCIOs have not taken steps to fully track the completion of required training for criminal investigators because they do not have guidance with requirements or procedures to track completion of such training. Specifically, Army officials noted that the CID training manual does not contain information on the requirements to track the completion of training for criminal investigators. Officials said that the CID is currently revising its training manual and plans to include requirements on tracking training. AFOSI and CGIS officials said that they do not have guidance on tracking training completion. NCIS’ training manual provides guidance for documenting the completion of formal training by criminal investigators; however, the manual or other NCIS guidance is not clear on whether all criminal investigative training is required to be tracked.[15]

MCIO officials stated that tracking criminal investigative training is important. Specifically, CID and AFOSI officials stated that tracking training is necessary to ensure that quality training is provided to fulfill their mission. CGIS officials also stated that without the ability to track training, they would not be able to determine what skills investigators have or need, types of training needed, or required funding. Fully tracking completion of training ensures compliance with requirements and allows organizations to track progress consistent with identified goals and objectives. Without guidance that requires criminal investigative organizations to track the training completion for criminal investigators and outlines procedures for doing so, MCIOs may not have complete information on the qualifications met or retained by their criminal investigator workforce. Having such information would help leadership better identify future training needs and would allow for better alignment of qualified personnel with mission needs. For example, this type of information could help leadership identify and address areas where specific expertise would be beneficial to an office or where an office may experience inefficiencies due to the number of underexperienced personnel, such as inefficiencies reported by the Fort Hood Independent Review Committee.[16]

MCIOs Do Not Fully Evaluate Effectiveness of Criminal Investigative Training

MCIOs generally evaluate service-specific basic training

courses for criminal investigators with surveys to gauge student and supervisor

satisfaction and with periodic course reviews.[17]

MCIOs evaluate on-the-job and advanced training in different ways that may

include feedback on investigator job performance or course surveys. However,

MCIOs do not conduct program-wide evaluations of their criminal investigative

training.[18]

MCIOs Evaluate Some Training Courses

Service-Specific Basic Training

MCIOs evaluate their service-specific basic training courses through feedback collected from surveys and supervisor reports on criminal investigator competence. MCIOs send surveys to criminal investigators after they complete a course to collect their initial feedback. MCIOs then survey the investigators periodically after a course’s completion to collect their feedback over time. The survey feedback may include criminal investigators’ opinions on how well the material was delivered and relevance of tests that are administered during courses. MCIOs send surveys to new investigators’ supervisors to understand the extent to which new investigators are able to apply classroom learning on the job.

NCIS and AFOSI also conduct periodic reviews of their service-specific basic courses. CGIS officials stated they conduct such reviews as well. CID officials stated that CID plans to conduct its review when its service-specific basic course has run for 3 to 5 years. These course reviews include comprehensive reviews of courses including their requirements and objectives. AFOSI and CID officials also stated that course reviews include consideration of training courses and topics provided through the program. Officials explained that MCIOs may determine whether course changes are needed during these reviews and make related adjustments.[19] Some MCIOs also conduct annual course reviews of the service-specific basic course to identify any improvements, such as updated content or training methods, that can be made for the next course offering, and then modify the course accordingly.

MCIOs may decide to approach course reviews and updates in additional ways. For example, AFOSI officials said that significant policy changes may prompt a course review and update. In another example, NCIS conducted an additional evaluation of service-specific basic training by soliciting and analyzing feedback from criminal investigators who graduated from eight different basic courses. This feedback resulted in a report with analysis of over 100 program graduates’ responses about training quality, course length, and relevance of skills taught in the class. NCIS also collected and analyzed responses to similar questions from participating criminal investigators’ supervisors. Furthermore, CGIS officials said they collaborate with experienced agents to understand what topics should be covered in service-specific basic training. CGIS officials also stated that they generally work independently in evaluating training courses and that CGIS has access to Coast Guard resources, such as experts that can help identify training needs during course development.

Service-Specific On-the-Job Training

MCIOs do not have standardized evaluations for their service-specific on-the-job training. MCIO officials said they evaluate their on-the-job trainings on whether criminal investigators can perform their assigned training duties competently. CID, NCIS, and AFOSI use supervisors’ feedback for criminal investigators in the on-the-job training process to identify criminal investigators’ performance level, proficiency, or training needs. Similarly, CGIS officials stated that they use supervisors’ assessments of criminal investigators during on-the-job training to determine whether relevant training needs adjustments. NCIS also analyzes trends in the feedback from supervisors to help inform training updates. Additionally, NCIS and AFOSI officials said they conduct regular field office inspections that assess the office’s functions including their on-the-job training program.

Additional and Advanced Courses

MCIOs evaluate their additional and advanced criminal investigative training in different ways. MCIOs use surveys and informal feedback to evaluate courses administered by the MCIOs. For training conducted by other providers, some MCIOs stated that they will collect information by administering surveys to participants or sending an experienced agent to audit and report back on the course’s usefulness.

MCIOs Do Not Conduct Program-Wide Evaluations of Criminal Investigative Training Effectiveness

MCIOs conduct course-level reviews and collect feedback that can provide insight into how criminal investigators rate courses and apply relevant skills, but they do not conduct program-wide evaluations of their criminal investigative training. MCIO officials provided information about course reviews and feedback, but they stated that they did not have or had not conducted program-wide evaluations of the criminal investigative training program.

MCIOs have training manuals or comparable documents that could facilitate such evaluations. These documents describe MCIOs’ administration of and requirements for criminal investigative training, but they do not address program-wide evaluations. NCIS and AFOSI manuals describe training responsibilities, curriculum, and assessments of new criminal investigators, among other information. Beginning in fiscal year 2024, CGIS published an annual training plan outlining available and required criminal investigative training. CID’s current training manual is under revision, according to officials. However, these MCIO manuals do not provide information, such as time frames for review or documenting results, for program-wide evaluation for criminal investigative training. In addition, MCIOs’ training documents do not include the MCIOs’ definitions or measures of effectiveness or descriptions of how to determine the extent to which criminal investigative training supports the accomplishment of MCIOs’ goals. MCIOs could facilitate program-wide evaluation by describing how service-specific training expectations support MCIO and training program goals.

Program-wide evaluation of training effectiveness allows an agency to measure their progress toward or ultimate accomplishment of the agency’s goals. Our guide on strategic training and development efforts in the federal government states that it is important for agencies to evaluate their training and development programs and demonstrate how these efforts help develop employees and improve the agencies’ performance.[20] Specifically, evaluation involves, among other things, assessing the extent to which training and development efforts contribute to improved performance and results. It adds that agencies should develop indicators to help make those determinations and include description of measures to be used in such assessments. It also states an agency should have guidelines for determining when and how its training program should be evaluated. Further, the Code of Federal Regulations requires that agencies evaluate their civilian employee training programs annually to determine how well such plans and programs contribute to mission accomplishment and meet organizational performance goals.[21]

In addition, federal internal control standards state that management develops competent personnel to achieve its objectives through, among other things, training to enable individuals to develop appropriate competencies for their roles. Further, these standards state that management should use, evaluate, and document the results of evaluations, among other things, to determine the effectiveness of an internal system. Management also evaluates and documents results to identify potential concerns. Documenting results can also provide a way to retain and communicate organizational knowledge. Management uses evaluations to monitor effectiveness at a specific time.[22]

MCIOs collect information and feedback to evaluate certain criminal investigative training courses, but do not evaluate the overall effectiveness of their criminal investigative training programs because DOD and the Coast Guard do not require MCIOs to develop plans for regular program-wide evaluation for their criminal investigative training programs that include time frames for review, measures of effectiveness, and documented results.

Plans for regular program-wide evaluation with time frames for review, measures of effectiveness, and documented results would provide MCIOs with the ability to demonstrate how their criminal investigative training programs develop criminal investigators and contribute to MCIOs’ missions. Documenting the results of the evaluations would provide MCIOs with the opportunity to further demonstrate those contributions over time. In addition, the results of such evaluations could inform decisions about training programs—such as those about necessary changes, future enhancements, or resources allocations—or identify areas that could be improved. Likewise, if MCIOs conduct and document such program-wide evaluations, DOD and the Coast Guard could use them as a resource in overseeing criminal investigative training programs.

DOD Provides Limited Oversight of MCIOs’ Training Programs

DOD does not regularly monitor and evaluate the criminal investigative training programs of the MCIOs within DOD. Neither the DOD IG nor the Office of the USD(I&S) review criminal investigative training activities of the MCIOs within DOD on a regular basis.[23] These offices are responsible for criminal investigative programs and law enforcement, respectively, but responsibility of oversight activities for criminal investigative training programs remains unclear.

DOD IG has established an annual process for determining its reviews and related oversight activities for DOD and publishes an oversight plan annually, but this process typically does not include training-specific topics for the MCIOs within DOD. The DOD IG’s annual oversight plans for fiscal years 2024 and 2025 include a review of MCIOs’ criminal investigations, but the plans do not include other MCIO criminal investigative topics such as training.[24] A DOD IG official explained that the office must prioritize its reviews to maximize resource usage and that the annual oversight plan outlines its annual priorities. The official also stated that the IG considers training requirements when conducting project-based reviews of topics that include criminal investigations, but typically does not review criminal investigative training programs separately.[25] Moreover, DOD IG’s internal reviews of the defense MCIOs’ criminal investigations also discuss training as a support program for an MCIO’s investigations.[26] DOD IG and MCIO officials stated that they may occasionally discuss policy and law enforcement matters and would coordinate on any reviews involving their entities, but MCIO officials confirmed that they do not work with the DOD IG concerning criminal investigative training topics.

As the principal staff assistant for law enforcement, USD(I&S) is responsible for oversight of the development, implementation, and integration of DOD’s law enforcement policy, mission objectives and training requirements, operating guidance, and resourcing. USD(I&S) does not monitor or evaluate MCIOs’ training as part of its law enforcement responsibilities.[27] According to the Office of USD(I&S) officials, in early 2024, USD(I&S) established a law enforcement directorate with responsibility for policy development and oversight related to DOD’s police policy and some of its investigative policy, which is shared with the DOD IG. USD(I&S) officials confirmed the directorate has not taken steps to monitor or evaluate the criminal investigative training programs of the MCIOs within DOD, but they expect it to start conducting oversight for DOD-required training for law enforcement in fiscal year 2025.

While neither the DOD IG nor USD(I&S) regularly monitors or evaluates criminal investigative training programs for criminal investigators, both offices have related responsibilities. Specifically, according to statute and separate from the responsibilities assigned to USD(I&S), the DOD IG is responsible for policy, monitoring, evaluation, and guidance for all DOD activities related to criminal investigative programs.[28] Also, an April 2023 memorandum from the Deputy Secretary of Defense designated the USD(I&S) as the principal staff assistant for law enforcement to ensure proper oversight and governance of DOD law enforcement. The memorandum stated that this designation would not interfere with the DOD IG’s statutory responsibilities, including those related to MCIOs and criminal investigative programs.

The April 2023 memorandum further directs USD(I&S), DOD General Counsel, and Director of Administration and Management in coordination with DOD IG to review and provide recommendations on alignment of law enforcement-related responsibilities between the two offices. USD(I&S) and DOD IG officials stated that they have worked on proposals for the division of law enforcement-related responsibilities and that training program oversight may be designated as a USD(I&S) responsibility, but as of March 2025, full alignment of those responsibilities had not been reached. Further, USD(I&S) officials stated that a draft action memorandum delineating the responsibilities for its office was forwarded to the Deputy Secretary of Defense, where it is awaiting signature, but as of March 2025, they were not certain whether the language in the memorandum had changed or remained the same since it left their office.

Federal internal control standards state that organizations should determine an oversight structure to fulfill responsibilities set forth by applicable laws and regulations, relevant government guidance, and feedback from key stakeholders. In addition, an organization’s oversight body is responsible for overseeing the remediation of deficiencies as appropriate and for providing direction to management on appropriate time frames for correcting these deficiencies.[29]

DOD, in designating USD(I&S) as the principal staff assistant for law enforcement responsibilities, acknowledged that the DOD IG has a statutory responsibility for criminal investigative programs and that the respective DOD offices should coordinate on shared responsibilities. However, DOD does not incorporate regular monitoring and evaluation of MCIO criminal investigative training programs because DOD has not finalized guidance on law enforcement-related responsibilities, which may include oversight of MCIOs’ training programs, that will align under USD(I&S). Without final guidance designating DOD offices’ responsibilities concerning criminal investigative training programs, DOD oversight of the MCIOs’ criminal investigative training programs may be incomplete, unclear, or delayed. This could limit DOD’s ability to support MCIOs as they develop criminal investigative training programs to ensure criminal investigators are fully qualified to carry out their investigative missions.

Conclusions

Proper handling of criminal investigations of serious and complex crimes by the MCIOs is critical to maintaining the safety, security, and readiness of military personnel. Ensuring that these investigations are properly conducted relies upon the MCIOs developing and maintaining qualified, professional criminal investigators. New criminal investigators at the MCIOs receive initial training on federal and service-specific topics and participate in on-the-job training tasks and pursue advanced training throughout their careers. MCIOs have taken steps to track some training completion, and some MCIOs are developing systems to collect training information. However, guidance with requirements and procedures to fully track criminal investigative training for criminal investigators would help ensure MCIOs can identify future criminal investigative training needs. Further, such information would help MCIOs identify expertise throughout their investigator staff to assist with specific criminal investigations.

MCIOs collect feedback on the training they administer and generally incorporate the information into periodic course-level reviews. However, MCIOs could use regular program-wide evaluations with time frames for review, measures of effectiveness, and documented results to demonstrate how effectively criminal investigative training programs contribute to agency goals and the development of criminal investigators. Additionally, such evaluations’ documented results would provide MCIOs with the opportunity to further demonstrate those contributions over time.

DOD has offices with responsibilities for law enforcement and criminal investigative programs, but USD(I&S)’s responsibilities for criminal investigative training programs have not been finalized, and thus, the training is not regularly monitored or evaluated. By finalizing its guidance on responsibilities that may include oversight of MCIOs’ criminal investigative training programs, DOD could improve oversight of the training programs to ensure that criminal investigators are appropriately carrying out their missions.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of nine recommendations, including seven to DOD and two to DHS. Specifically:

The Secretary of the Army should ensure the Department of the Army Criminal Investigation Division develops and issues guidance with requirements and procedures to track the completion of training for criminal investigators. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure the Naval Criminal Investigative Service updates its current guidance with requirements and procedures to track the completion of training for criminal investigators. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of the Air Force should ensure the Air Force Office of Special Investigations develops and issues guidance with requirements and procedures to track the completion of training for criminal investigators. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security should ensure that the Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard and the Coast Guard Investigative Service develops and issues guidance with requirements and procedures to track the completion of training for criminal investigators. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of the Army should ensure the Department of the Army Criminal Investigation Division develops plans for regular program-wide evaluations of its criminal investigative training program that include time frames for review, measures of effectiveness, and documented results. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure the Naval Criminal Investigative Service develops plans for regular program-wide evaluations of its criminal investigative training program that include time frames for review, measures of effectiveness, and documented results. (Recommendation 6)

The Secretary of the Air Force should ensure the Air Force Office of Special Investigations develops plans for regular program-wide evaluation of its criminal investigative training program that include time frames for review, measures of effectiveness, and documented results. (Recommendation 7)

The Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security should ensure that the Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard, as part of its oversight responsibilities, and the Coast Guard Investigative Service develops plans for regular program-wide evaluations of its criminal investigative training program that include time frames for review, measures of effectiveness, and documented results. (Recommendation 8)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Deputy Secretary of Defense finalizes guidance on the law enforcement-related responsibilities, including any oversight responsibilities for military criminal investigative organizations’ training programs, that will align under the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security. (Recommendation 9)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD and DHS for review and comment. In their written comments, reproduced in appendix II and appendix III respectively, DOD concurred with our seven recommendations directed to it, and DHS concurred with our two recommendations directed to it. DOD’s written comments include responses from the relevant DOD components. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

Both DOD and DHS provided comments regarding the recommendations and described actions the departments have taken or plan to take to address them. In its comments on recommendations 1 through 3 and 5 through 7, DOD provided information about the services’ planned efforts on tracking training completion, planning evaluation of training programs, or updating related guidance. DHS provided similar information concerning the Coast Guard’s planned efforts in response to recommendations 4 and 8.

It its comments on recommendation 9, DOD recognized changes resulting from the designation of the Office of the USD(I&S) as the principal staff assistant for law enforcement. As part of this transition, DOD acknowledged the absence of a signed memorandum to delineate the roles and responsibilities for oversight of criminal investigative training, acknowledged that DOD could clarify oversight responsibilities, and stated it plans to adhere to an existing memorandum while awaiting finalized guidance. As stated in the report, final guidance designating DOD offices’ responsibilities concerning criminal investigative training programs could enhance DOD’s ability to support MCIOs as they develop the programs and improve oversight of them, and such guidance would address our recommendation.

We are sending copies of the report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretaries of Defense and Homeland Security, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at williamsk@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Kristy E. Williams

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

Senate Report 118-58, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, includes a provision for us to review the investigative training that military criminal investigative organizations’ (MCIO) criminal investigators receive. This report addresses the extent to which (1) MCIOs provide and track completion of investigative training for criminal investigators, (2) MCIOs evaluate the effectiveness of investigative training for criminal investigators, and (3) Department of Defense (DOD) oversees investigative training provided to criminal investigators.

For purposes of this review, the MCIOs include the Department of the Army Criminal Investigation Division (CID), the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), and the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) under the Department of Defense (DOD), and the Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS) under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).[30] This review and supporting analysis focused on initial, advanced, and additional criminal investigative training for criminal investigators—including civilian and military personnel—at the MCIOs. We did not address general personnel training requirements that may apply to criminal investigators.

To address our first objective, we collected and analyzed relevant DOD, DHS, and military service policy and guidance to identify criminal investigative training required for and provided to criminal investigators.[31] We also collected and analyzed training-related guidance or plans on criminal investigative training from the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) and each MCIO in order to describe criminal investigative training for the MCIOs’ criminal investigators.[32] We interviewed knowledgeable officials from DOD, each MCIO, and FLETC to obtain additional information about criminal investigative training.

To determine the extent to which MCIOs track the completion of required investigative training for criminal investigators, we reviewed relevant guidance and interviewed knowledgeable officials. Specifically, we analyzed relevant departmental and armed forces guidance to determine (1) any requirements to track all criminal investigative training, including service-specific and some advanced training, and (2) any guidance on the procedures for tracking, recording, and verifying individual criminal investigators’ training completion.[33] We also collected information from each MCIO on information systems or other methods used to track, collect, and record criminal investigative training. We compared this information with applicable agency guidance and federal internal control standards on quality information. Specifically, we used the standard that calls for management to identify information requirements and process the data obtained into quality information that is appropriate, current, complete, and accurate.[34] We did not assess the quality of the information systems MCIOs use to record training information.

To address our second objective, we reviewed DOD, DHS, and military service documents that included information on criminal investigative training programs and evaluating training courses for criminal investigators.[35] Specifically, we collected information from documents and interviews with relevant officials on how and how often MCIOs (1) collect feedback on criminal investigative training; (2) evaluate criminal investigative training courses; and (3) evaluate criminal investigative training programs for effectiveness. We analyzed training manuals or comparable documents that describe MCIOs’ administration of and requirements for criminal investigative training to identify relevant information about evaluations. We also reviewed federal regulations and standards concerning training program evaluations to determine requirements, guidelines, or leading practices for implementing and documenting program-wide evaluations or for measuring program effectiveness.[36] We compared information collected about MCIOs’ training evaluations with applicable regulations and standards, including leading practices on training evaluation and federal internal control standards on management’s commitment to developing competent personnel and its documentation of evaluations and results. We did not assess the quality of the feedback collected by MCIOs.

To address the first two objectives, we also conducted a site visit to FLETC in Glynco, Georgia, where most initial federal law enforcement training occurs and where MCIOs conduct service-specific basic and some additional training. During the site visit, we interviewed relevant officials from FLETC and each MCIO’s training academy about criminal investigative training for federal criminal investigators including training requirements, provision, tracking, and evaluation. We observed training locations, ongoing training sessions, and a demonstration of FLETC’s records system.

To address our third objective, we reviewed and analyzed information—including laws, regulations, and DOD guidance—about responsibilities for law enforcement-related activities, MCIOs’ criminal investigative programs, and training programs, including training for criminal investigators. We reviewed documents describing the DOD IG’s processes for planning reviews and inspections as well as its annual oversight plans to identify relevant reviews of criminal investigative training programs.[37] We interviewed DOD and MCIO officials about (1) DOD activities related to criminal investigative training programs for criminal investigators and (2) coordination between DOD offices and MCIOs on reviews of such programs. We compared the collected information with federal internal control standards stating that organizations should determine an oversight structure and that an organization’s oversight body is responsible for overseeing the remediation of deficiencies as appropriate.[38]

We conducted this performance audit from September 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Kristy E. Williams, williamsk@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, GAO staff who made key contributions to this report include Vincent Balloon (Assistant Director), Rebekah J. Boone (Analyst-in-Charge), Carmen Altes, Latrealle V. Lee, and Meghann Lewis.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]For purposes of this report, we refer to these three entities together with the CGIS as MCIOs, to align with Senate Report 118-58, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024.

[2]Fort Hood Independent Review Committee, Report of the Fort Hood Independent Review Committee (Nov. 6, 2020).

[3]S. Rep. No. 118-58 (2023).

[4]Army Regulation 195-2, Criminal Investigation Activities (July 21, 2020); Secretary of the Navy Instruction 5430.107A, Mission and Functions of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (June 19, 2019); Department of the Air Force Instruction 71-101, Vol. 1, Criminal Investigations Program (Jan. 24, 2025); U.S. Coast Guard Commandant Instruction 5520.5G, Coast Guard Investigative Service Roles and Responsibilities (Jan. 11, 2023).

[5]DOD Instruction 5505.03, Initiation of Investigations by Defense Criminal Investigative Organizations (Aug. 2, 2023).

[6]5 U.S.C. § 408(c)(5).

[7]For this purpose, DOD defines law enforcement as activities dealing with enforcing laws, maintaining public order, and managing public safety.

[8]A few agencies conduct their own training, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation at the Federal Bureau of Investigation Academy.

[9]In addition to criminal investigative training requirements, criminal investigators are required to follow applicable DOD, DHS, and armed force personnel training requirements. This review discusses criminal investigative training. Initial training for federal criminal investigators is separate and distinct from military services’ basic training for military personnel.

[10]We did not identify any recurring criminal investigative training requirements.

[11]As we will discuss further in this report, some MCIOs adapt requirements for criminal investigators with former law enforcement experience, and Army’s military personnel attend alternate training.

[12]According to Army officials, CID hired only civilian personnel as new criminal investigators in fiscal year 2024 and plans to hire primarily civilians as criminal investigators for its investigative mission. Officials said that CID plans to staff its protective missions with military investigators, or agents, and expects to hire new military agents who will train at the U.S. Army Military Police School. CID’s “Special Agent Course” is a 15-week course taught by the Military Police Investigations Division at the U.S. Army Military Police School and is an accredited course by the Federal Law Enforcement Training Accreditation Board. Topics include law, crime scene processing, interview and interrogation, and crimes against persons, among others.

[13]Our review did not assess the quality of the information systems that MCIOs use to record training information.

[14]Principle 13, Section 13.02, 13.03, 13.04, and 13.05. GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

[15]DOD and the military services may have requirements to track certain training courses that are not unique to criminal investigators. This report focuses on criminal investigative training.

[16]In its final report issued in November 2020, the Committee stated that Army criminal investigators at the installation lacked sufficient experience and training to handle complex cases which, among other things, adversely affected the accomplishment of its investigative mission.

[17]Our review did not evaluate the quality of the information that MCIOs obtained through course feedback.

[18]This section of our review focuses on evaluations of effectiveness conducted by MCIOs. For this reason, we do not discuss FLETC’s evaluations of its training courses and programs, including CITP. Because of coordination between FLETC and MCIOs’ training academies colocated with FLETC, MCIOs may have access to relevant information from FLETC.

[19]Agencies that evaluate their training using the Kirkpatrick model or an equivalent approach and hold course reviews every 5 years may also seek accreditation from the Federal Law Enforcement Training Accreditation Board or other accrediting bodies for some or all their training programs and academies. AFOSI’s and NCIS’ service-specific basic courses are accredited by the Board. CID officials said they would like to have the new service-specific basic course accredited in the future and are developing their evaluation practices with this goal.

[20]GAO, Human Capital: A Guide for Assessing Strategic Training and Development Efforts in the Federal Government, GAO‑04‑546G (Washington, D.C.: March 2004).

[21]5 C.F.R. § 410.202.

[23]DOD IG and the Office of the USD(I&S) are offices within DOD that are responsible for issues related to the mission of the MCIOs within DOD and that could conduct related oversight activities. DHS IG does not have specific statutory responsibility for criminal investigation programs. CGIS conducts criminal investigations under the purview of the Coast Guard. However, DHS IG included related criminal investigative training topics in a 2017 report on CGIS as part of the planned periodic review of DHS components’ internal affairs offices. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General, Oversight Review of the United States Coast Guard Investigative Service (June 23, 2017).

[24]The fiscal year 2025 plan identifies 101 planned projects and 153 ongoing projects, which represent work initiated in prior fiscal years. DOD Inspector General, Fiscal Year 2025 Oversight Plan (Nov. 15, 2024). The fiscal year 2024 plan identified 83 planned projects and described 93 ongoing projects. DOD Inspector General, Fiscal Year 2024 Oversight Plan (Dec. 20, 2023). DOD IG’s oversight responsibility includes the full scope of DOD programs and activities. Its plans address a range of categories such as financial management, military readiness, quality of life for service members and families, infrastructure, and workforce, among others.

[25]For example, a DOD IG review on special victims’ investigations or sexual assault investigations may include consideration of training on those topics. In addition, in 2013, DOD IG completed a specific review of the MCIOs’ sexual assault investigation training (DOD IG, Evaluation of the Military Criminal Organizations’ Sexual Assault Investigation Training (DODIG-2013-043)(Feb. 28, 2013)).

[26]DOD IG published its most recent internal administrative review in 2020 for NCIS and in 2023 for CID and AFOSI.

[27]DOD law enforcement entities include military police, personal protective agencies, and defense criminal investigative organizations.

[28]5 U.S.C. § 408.

[30]For purposes of this report, we refer to these three entities together with the CGIS as MCIOs, to align with Senate Report 118-58.

[31]DOD Instruction 5505.03, Initiation of Investigations by Defense Criminal Investigative Organizations (Aug. 2, 2023); Department of the Air Force Instruction 71-101 Vol. 1, Criminal Investigations Program (Jan. 24, 2025); Army Regulation 195-2, Criminal Investigation Activities (July 21, 2020); Secretary of the Navy Instruction 5430.107A, Mission and Functions of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (June 19, 2019); U.S. Coast Guard Commandant Instruction 5520.5G, Coast Guard Investigative Service Roles and Responsibilities (Jan. 11, 2023).

[32]Department of the Army Criminal Investigation Division, Field Training Agent Handbook (undated); NCIS Special Agent Career Program, Chapter 13 (March 2008); Department of the Air Force CFETP 7S0X1/71SX/1811-0 Part I and II, Special Investigations, Career Field Education and Training Plan (June 21, 2023); Coast Guard Investigative Service, CGIS Strategic Training Plan FY 24 (undated); FLETC Directive 500-06, Training Management (May 5, 2021).

[33]Army Regulation 195-2, Criminal Investigation Activities (July 21, 2020); Secretary of the Navy Instruction 5430.107A, Mission and Functions of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (June 19, 2019); NCIS N-1, CH-14, Appendix E Training Requests and Recording of Completed Training (June 4, 2024); AFOSI Manual 36-2209-O, Agent Training Program (Apr. 11, 2018); U.S. Coast Guard Commandant Instruction 5520.5G, Coast Guard Investigative Service Roles and Responsibilities (Jan. 11, 2023).

[34]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

[35]Department of the Army Criminal Investigation Division, Field Training Agent Handbook; NCIS Special Agent Career Program, Chapter 13; Department of the Air Force CFETP 7S0X1/71SX/1811-0 Part I and II, Special Investigations, Career Field Education and Training Plan; Coast Guard Investigative Service, CGIS Strategic Training Plan FY 24; FLETC Directive 500-06, Training Management.

[36]5 C.F.R. § 410.202; GAO, Human Capital: A Guide for Assessing Strategic Training and Development Efforts in the Federal Government, GAO‑04‑546G (Washington, D.C.: March 2004); GAO‑14‑704G.

[37]DOD IG, Fiscal Year 2025 Oversight Plan (Nov. 15, 2024) and Fiscal Year 2024 Oversight Plan (Dec. 20, 2023).