SMALL BUSINESS PILOT PROGRAM

SBA Has Opportunities to Evaluate Outcomes and Enhance Fraud Risk Mitigation

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Jill Naamane, NaamaneJ@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107067, a report to congressional requesters

SBA Has Opportunities to Evaluate Outcomes and Enhance Fraud Risk Mitigation

Why GAO Did This Study

Racial and ethnic minorities, women, tribal groups, and other communities have historically faced barriers to accessing credit, capital, and other resources necessary to start and grow businesses, according to SBA. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 directed SBA to establish the Community Navigator Pilot Program, a new, short-term business assistance program to serve these communities.

GAO was asked to review the Community Navigator Pilot Program. This report examines (1) how the program reached underserved small business owners, (2) the program’s alignment with leading practices for pilot program design, and (3) the program’s efforts to manage fraud risk.

GAO analyzed SBA documents, interviewed officials, and compared the pilot program design and fraud risk management processes against leading practices. GAO also analyzed SBA and Census data and interviewed 18 navigators (chosen to reflect a mix of grant amounts, regions, and organization types) about their activities. GAO conducted three site visits reflecting a mix of geographic regions and organization types.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that SBA (1) evaluate the Navigator Program, incorporating a scalability assessment and input from a broad array of SBA staff and partner organizations; and (2) implement procedures for competitive grant program application reviews to obtain relevant information from district office staff with knowledge of applicants. SBA agreed with both recommendations.

What GAO Found

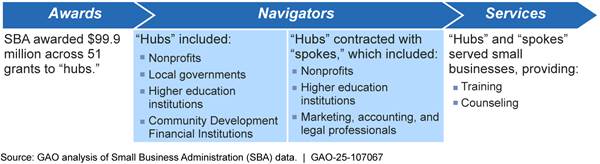

The Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Community Navigator Pilot Program aimed to expand access to small business assistance resources for underserved communities. The program, which operated from December 2021 to May 2024, awarded grants to “hubs”—nonprofits, local governments, and other entities that partnered with smaller organizations, called “spokes” (see figure).

Overview of SBA Community Navigator Pilot Program

SBA data suggest the program served a higher proportion of clients from high-minority, high-poverty, and low-income areas compared to other SBA business assistance programs. Challenges that navigators identified included collecting sensitive client data and building effective partner networks.

The Navigator Program aligned with one and partially aligned with four leading practices for pilot program design. SBA established clear, measurable program objectives, such as increasing use of SBA services among underserved business owners, and developed a data gathering strategy and assessment methodology.

However, GAO identified opportunities for SBA to evaluate the pilot and mitigate broader program risks:

· Evaluation. SBA does not plan to evaluate outcomes of the pilot. However, evaluations play a key role in strategic planning and program management. Conducting an evaluation would capture lessons learned from pilot activities. Additionally, by assessing scalability and incorporating input from a broad array of SBA staff and partner organizations, the evaluation could inform current and future programs and congressional decision-making.

· Fraud mitigation. SBA took steps to address fraud risk for the program, such as completing a fraud risk assessment and training hubs on financial oversight. However, during application reviews, SBA staff did not consult local SBA offices with potential knowledge about applicants’ risks. For example, staff in one district office said they could have flagged a local applicant that overstated its capacity to provide assistance. SBA officials said that to avoid potential bias and inconsistency, its competitive grant programs’ application reviews do not include consultation with local SBA offices. However, GAO identified federal grantmaking agencies that incorporated local staff input while implementing safeguards to mitigate bias and maintain consistency. By developing procedures to obtain relevant information from local agency staff, SBA could improve its ability to assess applicants and address fraud risks.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ARPA |

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 |

|

COMNAVS |

Community Navigator Information Management System |

|

EDMIS-NG |

Entrepreneurial Development Management Information System-Next Generation |

|

LGBTQ+ |

lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

SBA |

Small Business Administration |

|

SBDC |

Small Business Development Center |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

March 27, 2025

Congressional Requesters

Certain communities have historically faced barriers to accessing credit, capital, and other resources necessary to start and grow businesses, according to the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Council on Underserved Communities. These communities may include populations such as American Indians or Alaska Natives, women, racial and ethnic minorities, veterans, and those living in inner cities or rural areas.[1] SBA’s business assistance programs offer training, counseling, networking, and mentoring services to current or prospective small business owners, including those who belong to these communities.

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 directed SBA to create the Community Navigator Pilot Program, a short-term business assistance initiative designed to support recovery from the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.[2] The statute identified historically underserved small business owners as the program’s focus, although all current or prospective small business owners could access its services. SBA selected organizations for grant awards under the program in October 2021 and established a 2-year performance period (December 2021–November 2023). It then offered a 6-month extension for organizations with remaining funds and ended the program in May 2024.

You asked us to review SBA’s implementation of the Navigator Program. This report examines (1) how and the extent to which the program reached underserved small business owners, (2) the program’s alignment with leading practices for pilot program design, and (3) the program’s efforts to manage fraud risk.

For the first objective, we obtained and analyzed SBA client-level data on services provided through the Navigator Program and the demographic composition of clients it served.[3] We also obtained similar data for three other SBA business assistance programs and used SBA and U.S. Census Bureau data to compare clients by zip code characteristics between the Navigator Program and these programs.[4] We calculated the total client-hours of training and counseling services and the estimated cost per client-hour of services delivered for each program during specified periods. We interviewed representatives from a nongeneralizable sample of 18 organizations that participated in the Navigator Program to describe how they reached underserved small business owners. These organizations were selected to reflect a mix of grant amounts, geographic regions, and other factors. They included nonprofits, local governments, and other entities. We conducted some of these interviews during three site visits reflecting a mix of geographic regions and organization types.

For the second objective, we reviewed documentation that included the program’s notice of funding opportunity and implementation plan, and SBA’s evaluation of the program’s implementation. We compared the Navigator Program’s design against leading practices for pilot program design we have previously identified.[5]

For the third objective, we reviewed the fraud risk assessment SBA conducted for the program and the agency’s Standard Operating Procedure for Grants Management, guidance for staff, and training for organizations that received grant awards. We also reviewed selected documentation from a nongeneralizable sample of 10 grant files.

For all three objectives, we interviewed SBA staff on program design and evaluation, data collection, and fraud mitigation. More detailed information on our objectives, scope, and methodology is presented in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2023 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

SBA Business Assistance

SBA’s Office of Entrepreneurial Development aims to help small businesses start, grow, and compete in global markets by providing training, counseling, and access to resources. The office oversaw the Navigator Program. It is also responsible for overseeing SBA’s other business assistance programs, referred to as SBA resource partner programs. These include the Small Business Development Center (SBDC), Women’s Business Center, and SCORE programs. SBA’s Office of Veterans Business Development oversees the Veterans Business Outreach Center program, which is also an SBA resource partner program.[6]

Through these programs, SBA provides technical assistance with preparing and assembling documents small business owners need to apply for small business loan and assistance programs. These documents can include tax records, bank statements, profit and loss statements, and business plans. According to an SBA Information Notice, collecting these documents and completing program applications without assistance can be challenging for small business owners.[7] These challenges can also be more significant for small business owners from minority, immigrant, rural, and other underserved communities, or those with disabilities.

The SBDC and SCORE programs were designed to serve all small business owners without targeting specific groups. In contrast, the Navigator Program targeted underserved communities, the Women’s Business Center program targets women entrepreneurs, with an emphasis on socially and economically disadvantaged entrepreneurs, and the Veterans Business Outreach Center program targets veteran and military entrepreneurs.

Navigator Program Targeted Outreach

In accordance with the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, the Navigator Program aimed to expand awareness and increase use of existing SBA services among underserved small business owners, with a focus on women, veteran, and socially and economically disadvantaged small business owners.[8] SBA’s May 2021 notice of funding opportunity for the program identified 10 groups for targeted outreach:

· COVID-19 affected businesses[9]

· Socially and economically disadvantaged small businesses

· Minority entrepreneurs

· Microbusinesses[10]

· Women entrepreneurs

· Rural entrepreneurs

· Entrepreneurs with disabilities

· Veterans and military entrepreneurs (including spouses)[11]

· Tribal communities[12]

· Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) entrepreneurs[13]

To better reach these small business owners, SBA aimed to partner with new and existing partner organizations that had established relationships and experience working in targeted communities, according to the notice of funding opportunity.

Navigator Program Funding and Structure

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 authorized SBA to award $100 million for Navigator Program activities.[14] SBA awarded $99.9 million across 51 grants in three amounts for projects at different scales. SBA funded the 51 grants as follows:

· $5 million for multi-state projects in service areas with more than 500,000 people,

· $2.5 million for state or regional projects in service areas with at least 500,000 people,

· $1 million for local or regional projects in service areas with fewer than 500,000 people.

“Hubs”, who were the grantees, included local governments, nonprofits, community development financial institutions, higher education institutions, and SBA resource partners. SBA required “hubs” to contract with at least five organizations, called “spokes,” and form a “hub-and-spoke” network. Spokes were typically smaller community organizations, such as nonprofits, higher education institutions, and private business service providers, such as marketing professionals, accountants, and lawyers. The staff and representatives of these “hub-and-spoke” networks, collectively referred to as navigators, allowed hubs and spokes to leverage each other’s existing services and relationships—including in underserved communities—and refer current or prospective businesses to the most suitable navigator for their specific needs.[15]

During the program’s two-and-a-half-year period of operation, 51 hubs worked with more than 450 spokes.[16] Hubs’ key responsibilities included selecting and monitoring spokes, coordinating or providing business assistance services including training and counseling, and completing quarterly performance and financial reporting. Spokes’ key responsibilities included conducting outreach, offering clients access to training and counseling services provided by linguistically and culturally knowledgeable experts, and helping collect client data.

The statute also authorized SBA to expend $75 million to develop and implement a program that promoted Navigator Program services to current or prospective small business owners.[17] According to SBA, the agency used these funds for activities such as translating sections of SBA’s website into languages other than English and conducting a national marketing campaign for the program from April through September 2023.[18]

Navigators Provided Training and Counseling to Underserved Small Business Owners, and Noted Benefits and Challenges

Training and Counseling Covered a Variety of Topics and Navigators Reached New and Smaller Businesses

Navigators reported providing approximately 1.37 million hours of training to small business owners under the Navigator Program.[19] These trainings had a median of 13 clients and lasted a median of 2 hours. According to SBA data, training covered topics such as

· business operations and management (24 percent of training hours);

· business financing or capital access (15 percent); and

· marketing (12 percent).

Training that centered on a broad topic sometimes also covered multiple related topics. For example, training centered on business plans sometimes included information about marketing or disaster preparedness. SBA data indicate that 16 percent of navigators’ training hours included information on business startup or preplanning and 12 percent included information on creating business plans. This suggests some trainees were new or prospective business owners.

In addition to training, navigators provided individual counseling sessions. Specifically, we estimated that navigators provided counseling to 37,417 clients and navigators reported delivering 205,167 hours of counseling (for an average of 5.5 hours per client).[20] Those counseling hours generally focused on

· general business assistance (37 percent of counseling hours);

· loan, grant, or other applications (29 percent); and

· financial literacy and use of credit (5 percent).

SBA counseling data also suggest that the Navigator Program’s counseling services helped reach clients new to SBA services. Thirty-eight percent of counseling clients reported not receiving or applying for SBA services in the previous 5 years.[21]

SBA data also show that navigator clients tended to represent smaller businesses. Among navigator clients who reported being currently in business, 60 percent operated microbusinesses (i.e., up to nine employees), with 37 percent identifying as sole proprietors. This aligns with the observations of SBA staff, who noted that navigators primarily served smaller businesses and sole proprietors, whereas other SBA resource partner programs typically served comparatively larger businesses. Navigators we spoke with said they often helped these newer, smaller businesses with foundational issues, such as the steps for accessing loans or grants. Representatives of four navigators we spoke with said they helped explain loan application requirements, such as providing financial statements showing a profit in prior years.[22]

Data Suggest Navigator Program Largely Counseled Clients in Underserved Groups

Characteristics of Navigator Program Counseling Clients

About 95 percent of the Navigator Program’s estimated 37,417 counseling clients self-identified with at least one of the underserved demographic groups or areas targeted by the program, according to our analysis (see table 1). This included 81 percent who self-identified with a minority group.

Table 1: Counseling Hours and Number of Clients SBA’s Community Navigator Pilot Program Reported for Clients Who Self-Identified with Targeted Groups

|

Targeted group |

Total counseling hours provided (N=205,167) |

Number of clients counseled (N=37,417) |

Percentage of clients counseled |

Percentage of

clients missing data or |

|

Underserved |

196,292 |

35,529 |

95% |

4% |

|

Minority |

165,419 |

30,440 |

81% |

1% |

|

Woman |

112,081 |

18,732 |

50% |

17% |

|

Rural |

27,987 |

4,177 |

11% |

5% |

|

Military connected |

12,672 |

2,296 |

6% |

23% |

|

Individual with a disability |

12,356 |

2,382 |

6% |

24% |

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

11,184 |

1,614 |

4% |

22% |

|

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer |

4,131 |

616 |

2% |

75% |

|

Microbusiness |

127,686 |

22,349 |

60% |

14% |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) data. | GAO‑25‑107067

Note: SBA did not collect data on clients with COVID-19 affected businesses because SBA considered nearly all small businesses were likely affected. For the category of underserved clients, we included the categories that aligned with SBA’s data on socially and economically disadvantaged clients. Rural clients were identified using the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Continuum Codes, consistent with SBA’s method. For microbusinesses, we analyzed employee numbers reported by clients currently in business, applying SBA’s definition of fewer than 10 employees. Clients reporting having multiple attributes are represented in multiple targeted groups.

A similar demographic analysis of training clients (as opposed to counseling clients) was not possible because we could not identify individual clients who attended training.[23] In addition, the voluntary nature of the demographic fields resulted in significant missing data, limiting SBA’s ability to measure services provided to certain targeted groups.[24]

Comparison of Client Characteristics with Other SBA Programs

We also conducted a comparative analysis of counseling client characteristics between the Navigator Program and three other SBA resource partner programs: the SBDC, Women’s Business Center, and SCORE programs. Differences in the amount of demographic data these programs collected do not allow for direct comparisons. Therefore, we analyzed clients by zip code characteristics, which allowed for a more indirect but still informative comparison across programs.

Our analysis showed the Navigator Program counseled a higher percentage of clients from majority-minority, high-poverty, and low-income areas compared to these three other SBA programs (see table 2).[25] For SBA’s three resource partner programs, the percentage of counseling clients from these areas remained consistent across fiscal years, both prior to and during the Navigator Program’s performance period.

|

SBA program |

Fiscal years |

Majority-minority |

Rural |

High-poverty |

Low-income |

|

Community Navigator Pilot Program |

2022–2023 |

53% |

11% |

29% |

23% |

|

Small Business Development Center |

2019–2021 |

33 |

17 |

19 |

15 |

|

2022–2023 |

34 |

17 |

19 |

16 |

|

|

Women’s Business Center |

2019–2021 |

46 |

9 |

22 |

17 |

|

2022–2023 |

47 |

10 |

22 |

18 |

|

|

SCORE |

2019–2021 |

38 |

5 |

14 |

11 |

|

2022–2023 |

40 |

5 |

14 |

11 |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) and U.S. Census Bureau data. | GAO‑25‑107067

Note: We characterized areas at the zip code level as: (1) majority-minority, where at least 50 percent of the population identified as a minority in the 2020 Census; (2) rural, using the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Continuum Codes; (3) high-poverty, where the poverty rate was at least 20 percent; and (4) low-income, where the zip code’s median household income was in the bottom 20 percent, according to 2018–2022 American Community Survey data. The estimates for high-poverty and low-income have a margin of error for 95 percent confidence intervals no greater than ±0.3 percentage points. For all estimates, less than 10 percent of clients were missing data for all observations. Individuals with missing data were excluded from the calculations.

In addition, the percentage of clients from rural areas was smaller for the Navigator Program (11 percent) than that of the SBDC program (17 percent), and about the same or somewhat higher than that of the Women’s Business Center and SCORE programs. The difference in reaching rural clients between the SBDC and Navigator programs may be attributed in part to the fact that, as of 2023, there were nearly twice as many SBDCs as navigators. However, SBA staff and representatives of navigators we spoke with described instances where the Navigator Program facilitated outreach in rural areas, increased attendance at rural events, and helped SBA district office staff reach tribal communities in rural areas, some for the first time.

Several factors may have contributed to the differences in the client base served by the Navigator Program compared to other SBA resource partner programs. SBA staff said some potential clients were unfamiliar with the other SBA resource partner programs or did not feel comfortable engaging with them. For example, a representative from one hub noted that the local SBDC (which was not in the navigator network) is on a private college campus, which could intimidate some potential clients.

In addition, representatives from five navigators said that clients in certain underserved communities may be hesitant to engage with state and federal organizations or complete government paperwork. These clients may have preferred working with navigator spokes, who were often already established in underserved communities, according to representatives from one hub. For example, one hub representative said spokes familiar with a minority community helped clients who required translation services or were reluctant to disclose their ethnicity due to concerns about discrimination.

Federal Costs for Selected SBA Programs

To shed light on the comparative costs of selected SBA programs, we analyzed SBA data. We developed program-level cost estimates that help characterize the relative cost to the government of delivering training and counseling services through the Navigator, SBDC, Women’s Business Center, and SCORE programs. Our estimates used the total federal costs SBA reported for each program for fiscal years 2022 and 2023 and do not reflect the matching funds required for some programs.[26] To enhance comparability, we adjusted the Navigator Program’s reported federal cost by removing SBA’s estimated expense of developing the new Community Navigator Information Management System compared to using an existing system.[27] Then, we used SBA data to calculate the total hours of individual counseling and client-hours of training these programs reported providing in these fiscal years (see table 3).[28]

Table 3: Client-Hours of Service Selected SBA Programs Reported Providing in Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023

|

SBA program |

Total hours of individual counseling |

Percentage

service hours |

Total |

Percentage

service hours |

Total |

|

Community Navigator Pilot Program |

205,167 |

13% |

1,366,715 |

87% |

1,571,882 |

|

Small Business Development Center |

1,547,189 |

43% |

2,053,019 |

57% |

3,600,208 |

|

Women’s Business Center |

216,061 |

17% |

1,092,385 |

83% |

1,308,446 |

|

SCORE |

601,134 |

21% |

2,254,569 |

79% |

2,855,703 |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) data. | GAO‑25‑107067

Note: For each program, we calculated hours of client services by combining the total hours of individual counseling and client-hours of training. We calculated the total client-hours of training by multiplying the total hours reported for each training by the number of attendees. The COMNAVS data cover December 1, 2021, through May 31, 2024, and were current as of June 4, 2024. We included outliers.

Our analysis also calculated the approximate cost to the government per client-hour of service each of these four programs reported delivering.

· Navigator Program. The Navigator Program’s federal cost per client-hour of service delivered was around $90 during its performance period.[29] SBA staff said the Navigator Program’s focus on serving socially and economically disadvantaged small business owners resulted in navigators often working with harder-to-reach clients. They said that this led to a lower volume of service. SBA staff also said estimated costs of a new program like the Navigator Program may not be directly comparable to those of established programs, such as the SBDC program, because communities with SBDCs are already familiar with their services. This may result in a higher volume of service for some of the established programs.

Our analysis showed that navigators reported that most of their total service hours were group training services. This approach may have helped lower the program’s cost per client-hour of service, as trainers could reach multiple clients per hour. In addition, navigators told us they delivered training services both in-person and via recorded webinars that did not require live interaction with clients. The use of such webinars may also have lowered the Navigator Program’s estimated cost per client-hour.

· SBDC. The SBDC program’s federal cost per client-hour of service delivered was around $85 in fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2023. Our analysis showed that the SBDC program reported delivering a greater percentage of individual counseling services and served a greater percentage of clients in rural areas compared to the other resource partner programs (see tables 2 and 3). SBA staff said SBDCs’ focus on these services may raise the program’s cost per client-hour of service. This is because staff spend a comparatively higher percentage of service hours working directly with individual clients or traveling to rural areas. SBA staff also said SBDCs have more staff available to counsel clients and typically serve larger geographic areas than other resource partners. When including matching funds contributed by SBDCs, the program’s overall estimated per client-hour training and counseling cost would be higher.[30]

· Women’s Business Center. The Women’s Business Center program’s federal cost per client-hour of service delivered was around $45 in fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2023. Our analysis found that, compared to the Navigator Program, the Women’s Business Center program reported providing similar percentages of training and service to rural clients (see tables 2 and 3). SBA staff said Women’s Business Centers have fewer staff than SBDCs and may focus on providing group training rather than individual counseling to increase the number of clients they reach. SBA staff also said Women’s Business Centers tend to serve cities or counties, where clients are concentrated in smaller geographic areas. This may lower the program’s cost per client-hour of service. When including matching funds contributed by Women’s Business Centers, the program’s overall estimated per-hour training and counseling cost would be higher.[31]

· SCORE. The SCORE program’s federal cost per client-hour of service delivered was around $15 in fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2023. Our analysis showed that the SCORE program reported providing a slightly higher percentage of individual counseling services compared to the Navigator Program. The SCORE program’s reliance on unpaid volunteer counselors likely contributed to lowering the program’s cost per client-hour of service.

According to SBA staff, it is difficult to develop a single program-level cost estimate that encompasses both counseling and training services. Varying amounts of staff time and resources are required to deliver these services, complicating cost estimation. In addition, SBA staff said that even when providing the same type of service, the required staff time and resources can vary. For example, developing certain training programs can be time-intensive, while other training may be developed and donated by organizations such as universities, requiring minimal staff resources.

Navigators Described Benefits of the Program and Challenges Related to Delivering Services

Navigator representatives said they experienced benefits and challenges while implementing the program. Benefits to navigators included enhanced capacity for outreach and individualized services, as well as opportunities for smaller organizations to build capacity and participate in a federal grant program. Benefits to clients included new tailored services, culturally sensitive and trusted support, services in multiple languages, and accessible services. Challenges included establishing effective hub-and-spoke networks, delays in disbursements of program funds, and collecting client data.

Benefits to Navigators

Representatives from hubs, spokes, and SBA staff described several benefits for navigators, including expanded services, capacity-building for smaller organizations, enhanced collaboration among organizations, and enhanced outreach.

Expanded services. The Navigator Program funding expanded navigators’ ability to provide individualized services, according to representatives of navigators we interviewed. Six navigators we spoke with, including four SBA resource partners, reported being able to provide clients with more in-depth assistance, such as substantial help with market research and business plan development.[32] Eight navigators we spoke with said some of these expanded services continued after the Navigator Program ended. For example, representatives from one spoke reported that rural clients continue to access online resources the spoke created as a navigator.

Capacity-building for smaller organizations. SBA staff and navigators we spoke with said the program’s hub-and-spoke model allowed smaller community organizations, serving as spokes, to participate in a federal program. For example, representatives from one hub noted that most of their spokes were small and did not have the capacity to handle the full range of grant management responsibilities, such as payment management and reporting requirements. The hub-and-spoke model addressed this by tasking the hub with overseeing these responsibilities. Two hubs’ representatives said they also aimed to equip spokes with new skills, such as performance data collection and graphical presentation of accomplishments. Acquiring these skills could enhance spokes’ ability to secure grant funding independently in the future according to the two hubs’ representatives.

Enhanced collaboration among organizations. The Navigator Program also increased connectivity among hubs, spokes, SBA district offices, and SBA resource partners, according to navigator representatives we spoke with. For example, one hub’s representative said the program encouraged collaboration among community organizations that typically competed for funding. Representatives from all nine hubs we contacted said they planned to continue coordinating with their spokes, SBA district offices, or SBA resource partners. SBA district office staff also said they planned to continue including navigators in their communication with other resource partners. One SBA office we spoke with said it planned to establish a formal year-long partnership with a former hub.

Enhanced outreach. Representatives of navigators said they enhanced their outreach by conducting in-person or tailored outreach and leveraging existing relationships among hubs, spokes, and community members and organizations. They said their most effective outreach methods included canvassing businesses, holding events in locations familiar to the targeted community, and soliciting referrals from existing clients. In addition, representatives of one hub stated they enhanced their outreach by hiring a business advisor who was known and trusted within the local Hispanic community. Another hub said it conducted outreach primarily through a Chamber of Commerce that served as a spoke, leveraging its existing relationships with potential clients and other spokes. A third hub reported that more than 30 local community organizations that were not spokes, including religious organizations and libraries, volunteered to promote the hub-and-spoke network’s services.

Benefits to Clients

Navigators and SBA staff also described several benefits for clients, including new tailored services and culturally sensitive and trusted support, services in multiple languages, and accessible services.

New tailored services. Five navigators reported that the program’s resources helped them create new services tailored to their clients’ needs. For example, one spoke created a year-long program providing military-connected business owners with dedicated counseling, training, and networking services. Representatives of this spoke said that after successfully piloting this model during the Navigator Program, they secured alternative funding to continue offering the program. Representatives of another spoke said they created webinars addressing stress management and retirement planning after finding these topics to be in high demand.

Culturally sensitive and trusted support. Ten of the 18 navigators we spoke with said they leveraged their cultural knowledge or took steps to add staff with such knowledge, helping them provide clients with culturally sensitive support. Staff from one SBA district office said they observed effective outreach to American Indians and Alaska Natives by a hub they described as a trusted community advocate and partner. The hub’s spokes focused on tribal-specific business assistance issues, which differ from those of other communities, according to the district office staff. Representatives of one hub told us they used funding to hire staff who conducted in-person outreach to small business owners in a minority community. Some owners, particularly immigrants, were hesitant to engage with government services. By canvassing the area, staff were able to build trust with potential clients and reach those who may be less likely to seek resources online or respond to email outreach, according to the hub’s representatives.

Services in multiple languages. According to our analysis, 11 percent of counseling clients reported needing services in a language other than English.[33] These languages most commonly included Spanish and Chinese, and less frequently included Arabic, Korean, and Somali. According to one SBA staff member, hubs provided culturally competent interpreters who were essential for conveying complex ideas with the correct terminology and context in languages other than English. This was particularly important for business terms that do not translate well, such as “elevator pitch.”

Accessible services. Three navigators and SBA staff we spoke with said the program made small business assistance services more accessible to certain clients. For example, representatives from one hub-and-spoke network said their spokes met with clients at nontraditional times to accommodate small business owners with full-time jobs, such as during the lunch hour or late evening. Representatives from one of the spokes in this network said they offered services in trusted locations because some clients expressed discomfort visiting the city’s downtown area. In addition, SBA staff in one district office reported that collaborating with their regional hub improved their understanding of how to support accessibility for individuals with disabilities. These staff also said local SBA resource partners applied knowledge gained from the hub and its spokes to create more accessible spaces.

Challenges Navigators Described

Representatives from navigators and SBA staff also described some challenges in implementing the Navigator Program, including challenges with establishing a network, delayed disbursements, data collection, and conducting rural outreach.

Difficulty establishing a network. Representatives we interviewed from two spokes told us their respective hubs encountered challenges in establishing an effective navigator network. Both said they became navigators after other spokes left the program and the hub or SBA district office staff requested their assistance. Neither hub fostered connectivity among the spokes in their network or provided adequate training and communication for required reporting, according to these spoke representatives.

Delayed disbursements. Representatives from two of the nine hubs we interviewed reported delayed program fund disbursements from SBA after submitting their quarterly financial reports. An SBA district office identified two other hubs that experienced similar delays. SBA staff attributed delays to unresolved questions about hub reports, requiring clarification before disbursing funds.[34] SBA changed its process for requesting clarification from hubs early in the program’s performance period, but staff said this change did not expedite the review and approval of funds.

Representatives from one hub experiencing delays stated that the hub used its own funds to provide timely payments to spokes. The second hub stated that in one reporting period, it experienced a delay of over 4 months. Delayed payments prevented it from delivering training at a community college, as it could not pay the instructor. This resulted in canceled training and damaged relationships with spokes. SBA’s contracted May 2024 implementation evaluation of the Navigator Program identified several similar examples of delayed disbursements contributing to financial stress among hubs and spokes.[35]

Data collection challenges. Of the 18 navigators we interviewed, 13 stated they had difficulty collecting client data, including 10 who said SBA’s required client intake form requested potentially sensitive information. One navigator noted the form asked for a client’s Social Security number (or Taxpayer Identification Number), implying the navigator would check clients’ tax records. Another navigator encountered resistance from clients when asking for demographic information, like gender identity or sexual orientation, which it felt was inappropriate for the tribal communities it served.

In addition, representatives of seven navigators said the form requested more information than they would typically collect. For example, a representative from one hub, also an SBA resource partner, said the Navigator Program required tracking significantly more metrics than its own resource partner program. Further, representatives of seven of the nine hubs we spoke with said they found it difficult to navigate the program’s new database management system.

SBA staff said the Navigator Program’s client intake form was similar to the form used by its other resource partner programs.[36] SBA created guidance for hubs on the form’s data fields, including guidance indicating that certain potentially sensitive data fields were voluntary. SBA staff also said they provided training on using COMNAVS and gathered input from representatives of hub organizations both during COMNAVS’ development and after its deployment.

Challenges conducting rural outreach. Representatives we interviewed from two hubs said they faced challenges conducting outreach outside of centralized locations, limiting their reach in rural areas. Spokes were not always geographically dispersed to reach all rural areas within a region, and substantial travel was needed to reach small numbers of rural clients.

Navigator Program Partially Aligned with Most Leading Practices but No Outcome Evaluation Is Planned

Prior to awarding grants, SBA’s Office of Entrepreneurial Development established an implementation plan for the Navigator Program and identified the program’s activities, outputs, and outcomes.

We have previously reported that a well-designed pilot program can help ensure agency assessments produce information needed to make effective program and policy decisions.[37] We identified five leading practices to design pilot programs:

1. Establish well-defined, appropriate, clear, and measurable objectives.

2. Articulate a data-gathering strategy and an assessment methodology.

3. Develop a data analysis and evaluation plan to track pilot performance and implementation.

4. Identify a means to assess lessons learned about the pilot to inform decisions on scalability, and whether and how to integrate pilot activities into overall efforts.

5. Ensure two-way stakeholder communication at all stages of the program.

We found that SBA’s design of the Navigator Program aligned with one of these leading practices and partially aligned with the other four.

Well-Defined, Appropriate, Clear, and Measurable Objectives

We found that SBA’s pilot program design aligned with this leading practice. SBA’s objective was to conduct targeted outreach and increase use of existing SBA services among underserved current or prospective small business owners. This objective was clear, measurable, and consistently reflected throughout program documentation, including the public website, implementation plan, and logic model.[38] The program’s May 2021 notice of funding opportunity defined target groups of underserved small business owners, as discussed previously. In addition, the objective addressed one of SBA’s strategic goals on equity, related to building an equitable entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Data Gathering Strategy and Assessment Methodology

SBA’s pilot program design partially aligned with this leading practice. SBA created a data gathering strategy to capture performance information, but it did not develop an assessment methodology that measured the program’s objective.[39] SBA’s data gathering strategy involved requiring hubs to use a standard form to collect qualitative and quantitative data on their network’s clients and services, and to submit quarterly performance reports.[40]

However, SBA’s assessment methodology did not fully measure the program’s objective. SBA’s notice of funding opportunity identified 11 performance metrics to assess the Navigator Program’s success, but these did not include metrics for evaluating the program’s large outreach component.[41] SBA staff told us outreach metrics could be added if the program were renewed in the future. Further, the Navigator Program’s metrics included outcomes, such as revenue or employee growth, that the agency cannot attribute to program activities and that may not be well-suited to a short-term program like the Navigator Program.

SBA planned to summarize some performance metrics by client characteristics, such as reporting counseling hours navigators provided to military-connected or women small business owners. SBA staff said privacy concerns prevent mandating the collection of demographic data.[42] As a result, it was not possible for SBA to assess navigators’ reach among some of the targeted groups.

SBA’s contracted May 2024 implementation evaluation of the Navigator Program recommended steps that would reflect fuller alignment with this leading practice. Specifically, the evaluation suggested the agency gather data on the nature and intensity of its engagement with underserved clients, such as metrics on client relationships established or referrals or other informal resources provided.[43] However, SBA staff said that adding metrics during the pilot was not feasible, and the evaluation was not published until the program ended in May 2024.

Data Analysis and Evaluation Plan

We found that SBA’s pilot program design partially aligned with the leading practice of developing a data analysis and evaluation plan.[44] In September 2024, SBA awarded a contract for a formal evaluation of Navigator Program outcomes. The contractor had proposed an evaluation design to assess the extent to which the program achieved its intended outputs and outcomes. SBA representatives told us that staff from the agency’s Office of Strategic Management and Enterprise Integrity were to collaborate with the contractor to develop an evaluation plan.

However, in February 2025, SBA officials told us the contract had been canceled and the outcome evaluation would not be conducted. Officials said they canceled the contract because they believed the evaluation would not align with recent executive orders related to government diversity, equity, and inclusion programs.[45]

Scalability

SBA’s pilot program design partially aligned with the leading practice of determining how scalability will be assessed and the information needed to inform decisions about scalability. Scalability refers to whether and how a new program approach can be implemented in a broader context. The Navigator Program’s May 2024 implementation evaluation and SBA’s annual evaluation plan included some consideration of the scalability of the Navigator Program.[46] The implementation evaluation included a research question, findings, and recommendations on program practices that could be integrated into SBA’s other resource partner programs.

Additionally, the outcome evaluation was expected to identify further lessons to inform other programs, according to SBA’s annual evaluation plan. SBA staff said lessons learned from the Navigator Program included insights on program design, payment processes, managing emergency response programs, and using a hub spoke model. The purpose of the evaluation was to ensure that these lessons were not lost.

Because SBA had not finalized a design for the outcome evaluation before canceling the contract, it is unclear how its methodology would have assessed scalability. The contractor’s proposal included plans to meet with certain stakeholders to discuss preliminary findings and collaborate on potential recommendations. However, neither the implementation evaluation nor the proposal clearly identified methods for assessing scalability of lessons learned from Navigator Program practices to SBA’s other resource partner programs.

Two-Way Stakeholder Communication

SBA’s pilot program design partially aligned with the leading practice of obtaining stakeholder input at all stages of the pilot program, including design, implementation, and assessment. According to SBA program staff, during implementation, they maintained regular communication with hub representatives and SBA district office staff through quarterly meetings. SBA directed district office staff to meet with hubs quarterly and provide technical assistance as needed. SBA program staff also said they described the program to SBA resource partner representatives during the Navigator Program’s first year of performance.

For the May 2024 implementation evaluation, the third-party evaluator contracted by SBA gathered information from some key stakeholders, including SBA headquarters staff responsible for the program, navigators, and clients.[47] According to SBA and the contractor’s proposal, the methodology for the outcome evaluation was to do so as well.

However, the contractor’s proposal for the outcome evaluation did not include a plan to gather perspectives from other stakeholders who might have useful insights. These include (1) partner organizations in SBA’s other resource partner programs, including those who also served as navigators; (2) SBA district office staff who worked on the program; or (3) other SBA units, such as the Office of Small Business Development Centers.

These stakeholders might have provided important perspectives, such as identifying Navigator Program practices that might be integrated into other SBA programs. Further, SBA resource partners might have identified potential barriers to implementing these practices in their regions. Similarly, SBA district office staff, having overseen both navigators and resource partners in their regions, could have compared their outreach and service delivery approaches, and the associated benefits or challenges. Finally, other SBA units might have identified opportunities to coordinate services among the agency’s other resource partner programs.

As noted earlier, the Navigator Program ended in May 2024. As of February 2025, SBA staff said there were no plans for a similar program or to implement the outcome evaluation. However, evaluations play a key role in strategic planning and program management, providing insights on program design and execution. An evaluation, while taking into account relevant executive orders, could capture valuable lessons from the Navigator Program, informing the design and execution of future initiatives and congressional decision-making.

Further, incorporating a scalability assessment into the evaluation would provide insights into applying the Navigator Program’s lessons across other SBA resource partner programs. In addition, gathering input from a broad array of SBA staff and partner organizations would help ensure the evaluation reflects a wide range of stakeholder perspectives useful for informing current and future programs.

SBA Took Steps to Mitigate Navigator Program Fraud Risks but Did Not Solicit District Staff Input on Applicants

SBA Assessed Fraud Risks for the Navigator Program

In 2022, SBA established a Fraud Risk Management Board to lead and oversee the agency’s fraud risk management efforts. The Board established a strategic plan to develop and communicate an agencywide fraud risk management strategy, including defining roles and responsibilities and developing fraud risk management training for SBA staff.[48] In 2024, SBA established a schedule to assess fraud risk for its major programs every 3 years.[49]

The Navigator Program was among the first SBA programs to undergo a fraud risk assessment. Using a new fraud risk assessment tool, staff identified seven fraud risks associated with Navigator Program activities. Staff then assessed each risk’s likelihood and impact. They also evaluated the extent to which ongoing control activities mitigated these risks. This information formed the Navigator Program’s fraud risk profile. Table 4 provides examples of these risks and control activities in place to mitigate them.[50]

Table 4: Description of Fraud Risks and Control Activities SBA Identified for the Community Navigator Pilot Program’s Fraud Risk Assessment

|

Fraud risk |

Description |

Examples of control activities |

|

Falsifying application |

Hub misrepresents the proposed project in its application with the intent of profiting without performing the duties listed. |

· Designated SBA staff, including grants management staff, conduct separate reviews of application materials. · SBA headquarters staff review quarterly performance reports to identify differences between a hub’s proposed project and current activities. |

|

Fraudulent charges |

Hub charges SBA for costs that are unrelated to the program and with the intent of personal gain. |

· SBA headquarters staff compare activities and accomplishments in hubs’ narrative reports with costs in financial reports. · SBA grants management staff conduct separate reviews of financial reports before approving payments. |

|

Fraud by spoke |

A spoke of a hub commits fraud, but the hub is unaware. |

· SBA headquarters staff require hubs to summarize spokes’ reporting by cost category. · SBA headquarters staff provide training and technical assistance for hubs on completing financial reports. |

|

Falsifying program data |

Hub submits inaccurate, duplicative, or false data on performance and financial compliance reporting to continue receiving payment while out of compliance. |

· SBA headquarters staff review quantitative data to identify outliers or potential errors. · SBA district office staff spot-check qualitative data during annual site visits and quarterly check-ins. |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) data. | GAO‑25‑107067

SBA staff said the Navigator Program’s fraud risk profile was updated by the end of 2024. SBA staff initially determined that each of the fraud risks associated with the Navigator Program scored low on the agency’s fraud risk rating scale.[51] To validate the initial assessment’s low-risk ratings, a fraud risk specialist in the program office planned to review supporting documentation of the program’s control activities, according to staff. SBA staff said the updated fraud risk profile will benefit from improved fraud risk management resources, such as a standardized agency-wide list of possible fraud risks.

SBA verified that staff followed the application review and selection process and later identified a possible improvement to the process for future programs. After selecting grantees, SBA’s Office of Internal Controls reviewed a sample of grant application files to confirm that staff had documented key control activities. The review found that all required documentation was present in each file, including verification of applicant eligibility, checklists confirming application completeness, and signed notices of award.

Additionally, in the program’s second year, SBA identified a potential need to clarify its policy related to contractor payments for similar programs in the future. Specifically, in conversation with one hub, SBA staff learned of two spokes that had received grant funds from the hub for providing contracted services to the Navigator Program network’s clients and also in support of the hub’s operations (such as providing accounting services for the hub).[52] SBA required the hub to replace both spokes and use grant funds to pay the new spokes for only one activity. SBA staff said the agency plans to consider policy changes intended to help ensure future contractors do not receive multiple payments from a single grant.

Other steps SBA took aimed at mitigating fraud risk for the Navigator Program included the following:

· Quarterly financial reports. SBA required hubs to submit quarterly financial reports to confirm that costs were allowable. SBA staff said their reviews of these reports identified and resolved potential instances of fraud, such as costs related to unallowed travel expenses.

· Quarterly performance reports. SBA staff said they reviewed hubs’ quarterly performance reports to confirm that activities aligned with their application’s proposed project. For example, SBA district office staff said they corroborated these reports by verifying that the services described matched performance data in the program’s database.

· Hub training. SBA staff trained hubs on their responsibilities for financial oversight of their spokes.[53] For example, SBA provided hubs with a financial reporting workbook for spokes and guidance on fundamental cost principles, such as how to assess allowability and ensure adequate documentation of costs.

· Communication and site visits. SBA district office staff communicated with and monitored hubs through quarterly check-ins and annual site visits, according to SBA staff. During these site visits, staff gathered information on hubs’ data management systems, interactions with spokes, and best practices and lessons learned. District office staff were also directed to conduct site visits with selected spokes to provide direct oversight support for the largest-scale networks.

SBA’s Assessment of Hub Applicants Did Not Incorporate Input from Local Staff

Navigator Program Grant Application Process

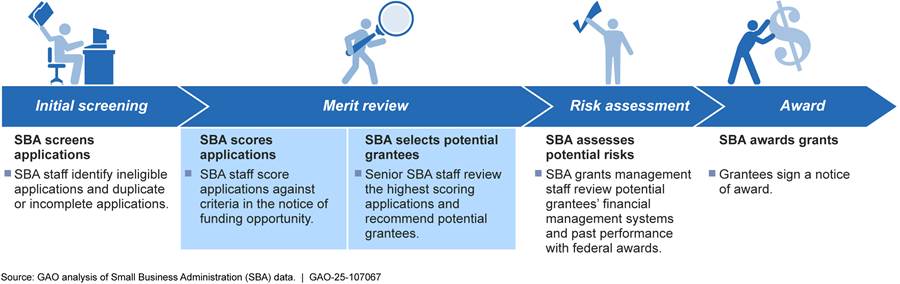

The stages of SBA’s process to select grantees for the Navigator Program included a merit review of eligible applications for organizations to be hubs and a risk assessment of potential grantees (see fig. 1). The program’s notice of funding opportunity outlined criteria for SBA’s merit review, which included applicants’ capacity to execute the proposed project and the reasonableness of their goals. After verifying eligibility, staff evaluated and scored each application based on the information it provided. According to SBA, district office staff participated in these reviews by scoring applications for Navigator Program hub applicants outside their own region.[54]

Next, a panel of SBA staff reviewed the highest scoring applications and selected potential grantees. The program’s notice of funding opportunity identified steps for SBA’s assessment of risks associated with these potential grantees, which included reviewing applicants’ financial management systems and past performance with federal awards.

Figure 1: SBA’s Competitive Grant Application Review Stages for Hubs in the Community Navigator Pilot Program

SBA staff said the Navigator Program sought applications from organizations that had not previously worked with SBA. To assess these applicants’ past performance, staff said SBA grants management staff reviewed available records in federal databases, including the Federal Awardee Performance and Integrity Information System and the Department of the Treasury’s Do Not Pay registry.[55] SBA also instructed applicants to provide examples of their prior experience, including projects with a similar scope and magnitude.

Input Not Sought from District Office Staff

As part of its application review process, SBA did not leverage the knowledge of district office staff who had potential knowledge about applicants’ risks. SBA headquarters staff told us that the agency’s district offices are knowledgeable about their local entrepreneurial development networks, which could include Navigator Program hub applicants. For example, SBA staff in applicants’ local district offices may have information relevant to assessing applicants that have not previously worked with the agency. These staff may also have information about which applicants and projects are likely to provide services that best meet their local area’s small business needs. However, the program and grants management staff did not consult district office staff about applicants from their local networks when assessing applications’ merit or applicants’ risks before making awards.

Such consultations could incorporate historical and contextual information when assessing applicants, providing SBA with opportunities to proactively identify whether applicants are appropriate for the program and to mitigate risks, including fraud risks, for approved grantees. For example, SBA could offer additional training or require more frequent reporting for grantees who lack a history of performance. Applicant risks include intentional and unintentional misrepresentations by applicants, such as overstating their capacity to execute a proposed project or failing to set reasonable goals in their applications.

For example, SBA staff in one district office told us they were not given an opportunity to share information before applicants were selected and they could have identified potential risks associated with the hub in their region. These district office staff reported that the hub had overstated its capacity to provide assistance and SBA documentation showed the hub had to significantly reduce the number of spokes in its network from 19 to four within the program’s first 6 months. Representatives from one of the hub’s spokes told us the hub did not appear to fully understand the spoke’s business assistance services, which led to miscommunications with navigator clients.

Officials from SBA’s Office of General Counsel stated that, similar to the Navigator Program, none of SBA’s other competitive grant programs solicit the input of district staff at any stage in the application review process. These officials said that limiting input from SBA district office staff helps prevent potential bias and ensure a consistent review process. They said that considering only information sources explicitly listed in the notice of funding opportunity helps ensure that all applicants are evaluated based on the same criteria. The Navigator Program’s notice of funding opportunity did not state that SBA would incorporate information from applicants’ local district offices. However, listing all information sources in notices of funding opportunity is not required.

Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance describes federal grant application review requirements. For merit reviews, agencies must establish standards to evaluate applications using an objective process.[56] For risk assessments, federal agencies must establish and maintain policies and procedures to evaluate the risks posed by applicants before issuing awards.[57] The criteria used when assessing applicants must be described in the notice of funding opportunity.[58] According to OMB staff, however, incorporating feedback from agency staff who are not reviewers would be permissible depending on the review standards set by the agency, the stage of the review, the purpose of seeking or receiving the input, and how the relevant assessment criteria are communicated in notices of funding opportunity. Further, OMB staff said that for merit reviews, agencies generally design standards to ensure the objectivity of the review process. These include ensuring the independence of merit reviewers and avoiding conflicts of interest.

In our prior work, we have identified examples of approaches agencies have taken to gather insights from staff familiar with applicants while mitigating potential bias.[59] For example, the Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration engaged local agency staff for historical and contextual information about applicants with whom they had experience. This information was considered as part of the merit review, alongside other available inputs, to assess applicants and understand associated risks. To mitigate the risk of bias, local staff were not present during deliberation and selection.[60] The notices of funding opportunity issued by the Economic Development Administration to award funds provided by the American Rescue Plan Act noted that application reviews would consider applicants’ past performance and project feasibility.

The Environmental Protection Agency provides another example of gathering local staff input while mitigating bias. At that agency, local staff reviewed and evaluated applications for competitive grant programs within their region. These local offices were directed to maintain documentation reflecting that reviewers and selection staff did not have any conflicts of interest related to the competition or any applicants competing for the award.[61] Similar to the Economic Development Administration, the notices of funding opportunity issued by the Environmental Protection Agency to award American Rescue Plan Act funds noted that application reviews would consider applicants’ past performance and organizational capacity. Communicating these assessment criteria could help ensure consistent reviews.

SBA’s Standard Operating Procedure for Grants Management requires risk management at each stage of the award life cycle to include identifying, analyzing, and responding to risks related to achieving the grant agreement’s objectives.[62] In addition, among the leading practices identified in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework is for agencies to collaborate with internal and external stakeholders to share information on fraud risks.[63] As noted earlier, SBA does not solicit the input of district staff at any stage in the application review process for its other competitive grant programs. By establishing procedures to gather information from district office staff with knowledge of applicants for the agency’s competitive grant programs, SBA could improve its applicant assessments and better manage potential fraud risks, while mitigating potential bias and inconsistency.

Conclusions

The Navigator Program pilot offered SBA the opportunity to partner with organizations serving underserved communities and enhance outreach to those communities. The program has concluded, and SBA officials said the agency canceled its contracted outcome evaluation in response to recent executive orders. However, conducting an evaluation—while taking into account relevant executive orders—remains essential. Evaluations play a key role in strategic planning and program management, providing insights on program design and execution. The Navigator Program pilot was established by law, and an evaluation would help inform Congress and SBA of its effectiveness and key lessons learned. An evaluation could ensure that lessons learned from the Navigator Program are not lost. Additionally, by assessing scalability and incorporating input from a broad array of SBA staff and partner organizations, the evaluation would inform decisions on integrating these insights into other SBA small business assistance efforts.

As part of the Navigator Program’s application review process, SBA did not consult district office staff who had knowledge of some applicants, a practice also absent in other SBA programs. This may deprive SBA of valuable insights for assessing applicant quality and mitigating fraud risk. By developing procedures (which consider items including the stage of the review, communicating assessment criteria, and potential bias) to solicit feedback from district staff for competitive grant applications, SBA would be better positioned to assess program applicants and manage potential fraud risks as its other business assistance programs continue.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making two recommendations to SBA:

The Administrator of SBA should complete an outcome evaluation of the Navigator Program. The evaluation should include an assessment of the scalability of lessons learned from pilot activities and incorporate input from a broad array of SBA staff and partner organizations. (Recommendation 1)

The Administrator of SBA should, for its competitive grant programs, implement procedures to obtain relevant information from district office staff with knowledge of applicants. In doing so, the SBA Administrator should consider the stage of the review at which staff should obtain such information, how staff should identify and address potential bias, and how to communicate relevant assessment criteria in notices of funding opportunities. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

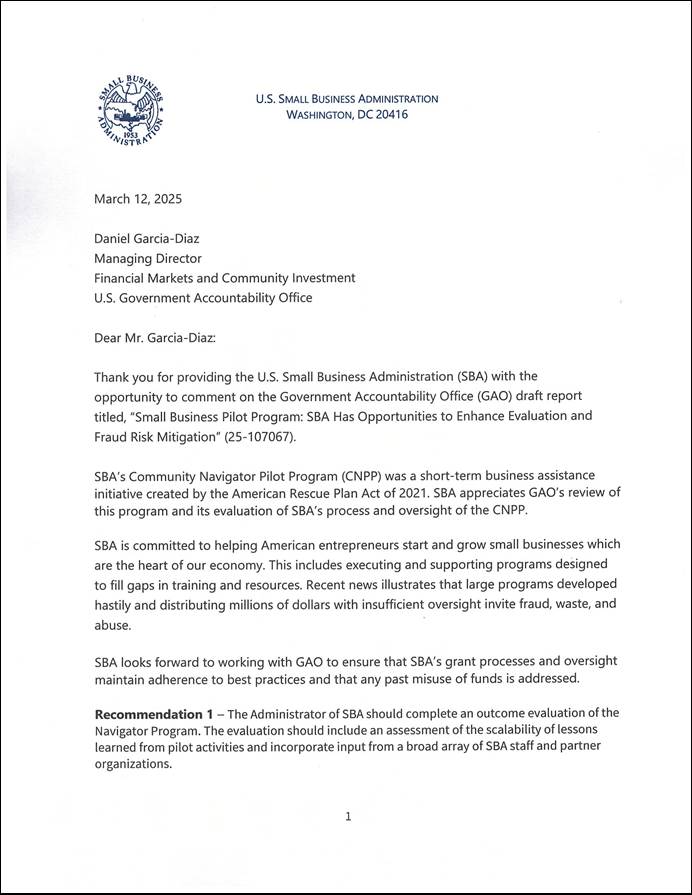

We provided a draft of this report to OMB and SBA for comment. The draft report recommended improvements to SBA’s contracted evaluation of Navigator Program outcomes. During SBA’s review of the draft, SBA officials said the agency no longer intended to conduct the contracted evaluation, and we modified our recommendation.

SBA provided a written response, reproduced in appendix III. SBA concurred with our recommendations. However, its proposed action may not fully address the intent of the first recommendation, which is focused on evaluating the program’s outcomes. SBA stated it would conduct an evaluation to identify any waste, fraud, or abuse. Such an evaluation may provide useful information on program design and execution. However, as stated in our recommendation, an evaluation of the program’s outcomes should include assessing scalability and incorporate input from a broad array of SBA staff and partner organizations. Identifying lessons learned from the Navigator Program through such an evaluation would inform decisions on integrating any insights into other SBA small business assistance efforts.

SBA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. OMB did not provide a formal comment letter or technical comments.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, Administrator of the Small Business Administration, Director of the Office of Management and Budget, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at NaamaneJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Jill Naamane

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

List of Requesters

The Honorable Nydia M. Velázquez

Ranking Member

Committee on Small Business

House of Representatives

The Honorable Judy Chu

House of Representatives

The Honorable Sharice L. Davids

House of Representatives

The Honorable Marie Gluesenkamp Perez

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jared F. Golden

House of Representatives

The Honorable Kweisi Mfume

House of Representatives

The Honorable Chris Pappas

House of Representatives

The Honorable Hillary J. Scholten

House of Representatives

This report examines (1) how and the extent to which the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Community Navigator Pilot Program reached underserved small business owners, (2) the program’s alignment with leading practices for pilot program design, and (3) the program’s efforts to manage fraud risk.

To describe the extent to which the program reached underserved small business owners, we obtained data from SBA’s Community Navigator Information Management System (COMNAVS). COMNAVS included data on training and counseling services navigators reported providing through June 4, 2024. We used all observations in COMNAVS, each of which describes one training session or set of sessions, one counseling session or other client communication. The data included outliers, which we included in our analysis.[64]

We analyzed training observations from COMNAVS, which included the date, number of sessions, number of hours, number of clients, and training topic. We calculated client-hours of training for a single training by multiplying the number of training hours for that observation by the number of individuals who attended that training. To describe training topics, we reviewed the data fields describing the topics of Navigator Program training sessions, identified the most frequently occurring topics, then calculated total client-hours of training that included information about these topics. We also summarized information in the training data’s demographic fields, including the amount of missing data.

We also analyzed data on counseling services navigators reported providing. These observations included (1) information about the counseling service, such as the date, number of hours, and language used; (2) any demographic information the client reported; (3) information about the client’s business, such as the number of employees the client reported; and (4) information about any loan or grant applications. Each observation related either to a specific counseling session or other client communication, such as an email.

We took a number of steps to analyze the demographic composition of counseled clients. First, we determined which counseling observations were for the same client. To do this, we created new versions of data fields, including clients’ email, telephone number, and street address where all letters were lowercase, and we removed all blank characters.[65] We also removed all non-numeric characters from telephone numbers and changed all street addresses without numbers to “missing.” Next, to determine which observations to associate with each unique client, we analyzed whether the following non-missing data fields were the same for any two of the following observations:

1. Email and telephone number

2. Email and street address line 1

3. Telephone number and street address line 1

4. Email and name-state (a concatenation of first name, last name, and state)

5. Email and organization name-state (a concatenation of organization name and state)

6. Telephone number and name-state

7. Telephone number and organization name-state

8. Street address line 1 and name-state

9. Street address line 1 and organization name-state

We then grouped observations based on that determination. For example, if observations A and B matched, and observations B and C matched, we grouped observations A, B, and C as relating to the same client.

To assign demographic attributes to each unique client, we first determined whether each grouped set of observations had an attribute, did not have an attribute, or was missing an attribute. We classified a client as having an attribute if the client

· had the attribute for at least one observation, and

· had the attribute for as many non-missing observations as it did not have the attribute.

For example, if a client received four counseling sessions and reported their gender for only three sessions, we classified the client as female if they reported they were female in at least two of those three sessions. We classified a client as missing an attribute if the client was missing information on the attribute for all observations associated with the client.

We assigned demographic attributes to each unique counseled client using the following categories:

· Gender. Using the gender data field, we classified a client as the gender they reported identifying with. Clients were able to identify as male, female, nonbinary, or could self-describe or not identify their gender.

· Minority. Using the race and ethnicity data fields, we classified a client as being a minority if the client reported identifying as a race other than White or if their ethnicity was Hispanic/Latino.[66]

· Military-connectedness. Using the military status data field, we classified a client as connected to the military if they reported they were either on activity duty, a member of a reserve component, a service-disabled veteran, a spouse of a military member, or a veteran.

· Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ+). We classified a client as LGBTQ+ if they used a sexual orientation or gender data field to identify as such.[67]

· Disability status. We classified a client as an individual with a disability if they used the disability status data field to identify as such.

· Underserved. Using the above determinations, we classified a client as underserved if we classified the client as a woman, American Indian or Alaska Native, minority, military-connected, LGBTQ+, or an individual with a disability. To align with SBA’s definition of socially and economically disadvantaged clients, we also classified clients as underserved if, using the zip code data field, we classified the clients as from a rural area (described in greater detail below).

We also summarized information on other attributes counseled clients reported, including the following:

· Microbusiness. Using data fields on business status and employee number, we classified a client as owning a microbusiness if they reported both that they were currently in business and that their business had between zero and nine employees.

· Served by SBA. Using the data field that asked clients if they had applied for or received SBA services in the past 5 years, we summarized the proportion of clients who reported they had been served, who reported they had not been served, and who did not respond.

· Language used. Using the data field that asked clients whether they needed assistance in a language other than English, we summarized the proportion of counseling clients who reported receiving counseling services in only English, who reported receiving counseling services in languages other than English, and who did not respond.

We also compared characteristics of Navigator Program clients with those of three other SBA resource partner programs’ clients: the Small Business Development Center (SBDC), Women’s Business Center, and SCORE programs. We chose these three programs because they provided services similar to the Navigator Program and used SBA’s Entrepreneurial Development Management Information System-Next Generation (EDMIS-NG) database to store data on their clients’ characteristics.