HOMELAND SECURITY

Actions Needed to Address Acquisition Workforce Challenges and Data

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107075. For more information, contact Travis J. Masters at (202) 512-4841 or masterst@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107075, a report to congressional requesters

Actions Needed to Address Acquisition Workforce Challenges and Data

Why GAO Did This Study

Each year, DHS obligates billions of dollars to acquire a wide range of goods and services. Since its inception in 2003, DHS has confronted numerous challenges related to recruiting, retaining, and managing its acquisition workforce.

GAO was asked to review DHS’s management of its acquisition workforce. This report examines, among other things, (1) what challenges, if any, the acquisition workforce reported facing, and the extent to which leadership is mitigating these challenges; and (2) the extent to which DHS and selected components have comprehensive data on this workforce to inform decision-making.

GAO selected four DHS components based in part on the high value of contract obligations and the number of contracts awarded in fiscal year 2023. These components accounted for about 63 percent of DHS’s obligations. GAO randomly selected a nongeneralizable sample of 55 key acquisition staff to interview from these components, and reviewed DHS acquisition program staffing plans and certification data.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations to DHS, including that it assesses whether its mitigation efforts effectively address challenges facing the acquisition workforce, establishes a methodology for identifying personnel in acquisition disciplines, and collects comprehensive data on its acquisition workforce. DHS agreed with one of the recommendations and did not agree with three of them. GAO continues to believe the recommendations are valid, as discussed in the report.

What GAO Found

The Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) acquisition workforce includes government personnel who oversee procurement and related acquisition functions and activities. This workforce includes three key acquisition positions identified in government-wide policy—program managers, contracting officers, and contracting officer’s representatives—in addition to eight other DHS-identified disciplines that support acquisitions.

In interviews with GAO, acquisition staff from four selected DHS components identified various challenges facing the acquisition workforce. GAO found that 41 of the 55 program managers, contracting officers, and contracting officer’s representatives that it interviewed identified heavy workload as their most considerable challenge.

Among acquisition program managers, GAO found that lengthy hiring time frames were also a considerable challenge. Twelve of the 17 program managers that GAO interviewed cited this as a challenge. For context, a fiscal year 2023 DHS report noted that acquisition hiring time frames ranged from 3 to 18 months.

DHS has not evaluated whether it is effectively addressing the challenges that staff identified, such as those related to workload or the lengthy hiring process. GAO found that DHS and its components have implemented a variety of general efforts to mitigate workforce challenges related to hiring, training, and certification. These efforts included programs for career development, mentoring, and training for acquisition leaders. Without evaluating these efforts, DHS lacks reasonable assurance that it is using the most appropriate methods to support its acquisition workforce.

Furthermore, DHS does not have comprehensive data on the size or demographics of its acquisition workforce. DHS entities responsible for the workforce only collect data on certain segments of the acquisition workforce, but have not established a methodology for identifying personnel in the eight other disciplines supporting acquisitions. Without establishing a methodology to identify these personnel and collecting comprehensive data on them, DHS lacks reasonable assurance that its decisions about current and future workforce requirements are based on complete information.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

CO |

contracting officer |

|

COR |

contracting officer’s representative |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

OCPO |

Office of the Chief Procurement Officer |

|

OFPP |

Office of Federal Procurement Policy |

|

PARM |

Office of Program Accountability and Risk Management |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 12, 2024

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Glenn F. Ivey

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Oversight, Investigations, and Accountability

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

Each year, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) obligates billions of dollars to acquire a wide range of goods and services to help it execute its many critical missions. The magnitude and complexity of DHS’s acquisition portfolio demands a sufficient, diverse, flexible, and properly trained workforce. End users depend on DHS’s acquisition workforce to help develop, procure, field, and sustain the technologies that help them accomplish their missions. This acquisition workforce consists of contracting officers and their representatives, acquisition program managers, engineers, logisticians, cost estimators, and many others.

Since its inception in 2003, DHS has confronted numerous challenges related to recruiting, retaining, and managing its workforce. In 2008, we found that DHS had taken steps to recruit, hire, and train contract specialists and acquisition program managers.[1] But, at that time, DHS had not developed a comprehensive strategic acquisition workforce plan to assess its workforce needs and determine whether its efforts were sufficient and prioritized appropriately. In 2011, we identified human capital as one acquisition management area that needed DHS’s attention, as reported in our High-Risk series.[2] In April 2023, we determined that DHS had made significant progress in addressing acquisition outcomes, including for human capital, so we narrowed the High-Risk area to DHS’s IT and financial management.[3]

You asked us to review DHS’s progress in managing its acquisition workforce. This report examines (1) the extent to which DHS has policies that reflect current government-wide training and qualification requirements for its acquisition workforce; (2) what challenges, if any, officials reported facing when performing their responsibilities, and the extent to which DHS or component leadership are taking steps to mitigate these challenges; and (3) the extent to which DHS and selected components have comprehensive workforce data to inform decision-making.

To determine the extent to which DHS policies reflect current government-wide training and qualification requirements for its acquisition workforce, we compared DHS’s policies on certification and training requirements with policies from the Office of Management and Budget’s Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP). OFPP sets standards for those positions across the federal government. For the purposes of our review, we focused on contracting officers (CO), contracting officer’s representatives (COR), and acquisition program managers because they have federal certification requirements.[4] We also interviewed officials from OFPP to learn about current government-wide acquisition workforce training and qualification requirements.

To determine what challenges, if any, the acquisition workforce faces when performing its responsibilities, we selected four DHS components for review that had high dollar contract obligation amounts for fiscal year 2023 and had a range of major and nonmajor acquisition programs.[5] We selected:

· U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement,

· the Transportation Security Administration,

· U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and

· the U.S. Coast Guard.

To identify any challenges facing the acquisition workforce when performing its responsibilities, and related mitigation strategies, we reviewed DHS documents, such as staffing analysis reports, and our prior work. Based on our review, we selected challenges to inform our semi-structured interview questions with a nongeneralizable sample of 55 acquisition staff filling CO, COR, and acquisition program manager roles for major and nonmajor acquisition programs within our selected components. We also analyzed information gathered from staff responses to semi-structured interview questions about the extent to which they faced selected challenges. We compared DHS and component efforts to human capital key principles that we identified in our prior work.[6] We used the term program managers in this review to include both program and project managers.

To identify the extent to which DHS is taking steps to mitigate acquisition workforce challenges, we interviewed DHS headquarters and component acquisition leaders. We also reviewed DHS headquarters and component documents, and other department information on initiatives that were underway. We assessed how, if at all, the initiatives were aimed at addressing the challenges that were identified by DHS acquisition officials.

To identify the extent to which DHS has comprehensive data on the acquisition workforce to inform decision-making, we reviewed DHS annual staffing plans and acquisition workforce reports from DHS’s Office of Program Accountability and Risk Management (PARM) and the Office of the Chief Procurement Officer (OCPO). We also reviewed DHS documentation about PARM’s staffing model. We reviewed available data against relevant DHS instructions, guidance, and OFPP policy for overseeing acquisition management and staffing data. Additionally, we obtained and consolidated DHS’s fiscal years 2022-2023 data from the Federal Acquisition Institute Cornerstone on Demand (Cornerstone) system, including individuals’ names, certification levels, and self-identification as members of the acquisition workforce.[7] In addition to reviewing DHS documentation about PARM’s staffing model, we also reviewed Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[8] Finally, we interviewed officials from various DHS and component offices to discuss their policies and procedures for collecting and maintaining acquisition workforce data, and what data they collect and share within the department.

Appendix I provides additional information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Management and Policies for the Civilian Acquisition Workforce

Several governmental organizations play critical roles in assisting civilian agencies in building and sustaining their acquisition workforces. The Office of Management and Budget’s OFPP provides government-wide guidance on managing the federal civilian acquisition workforce. Specifically, OFPP provides overall direction for government-wide acquisition policies, regulations, and procedures with the goal of promoting economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in acquisition processes—including how agencies manage their acquisition workforces.[9]

In 2005, OFPP issued policy letter 05-01 to civilian agencies to provide guidance on defining and identifying their acquisition workforces. The policy letter identifies minimum descriptions of positions that define an agency’s acquisition workforce, which include positions such as COs, CORs, and acquisition program managers.[10] COs are federal employees with the authority to bind the government by signing a contract acting within the limits of their warrant authority.[11] They are permitted to delegate some of their contract administration duties, especially technical assessments, to CORs. CORs may assist with the development of contract work statements and assist COs in administering their contracts. Acquisition program managers are responsible for performing duties such as developing work statements and managing contractor activities to ensure that intended outcomes are achieved for their assigned acquisition programs. Also, acquisition program managers are responsible for conducting acquisition workforce planning activities, remaining within allocated resources, and other required activities to manage the acquisition program. OFPP’s policy letter also establishes government-wide training requirements and refers to certification requirements for acquisition staff filling a CO, COR, or acquisition program manager role.

The OFPP guidance further suggests that agencies may broaden their definition of the acquisition workforce to include all individuals who perform significant functions related to acquisition. For example, the guidance highlights functional positions for test and evaluation, and business and finance. These positions provide key support for the management of programs and extend beyond the few procurement-related positions that have been traditionally considered in OFPP guidance as part of the civilian acquisition workforce.

The Federal Acquisition Institute, managed by the General Services Administration, promotes the development of the civilian acquisition workforce. It is responsible for managing agencies’ use of certain government-wide acquisition workforce data systems, such as Cornerstone. The Federal Acquisition Institute also is responsible for implementing OFPP’s government-wide acquisition certification programs. These programs established the minimum certifications for certain acquisition-related positions in civilian agencies. These certifications serve as the means to demonstrate that employees meet the foundational education, training, and experience requirements for their discipline.

Management and Oversight of DHS’s Acquisition Workforce

The DHS acquisition workforce consists of government personnel who perform, supervise, manage, or oversee procurement and related acquisition functions and activities. In addition to the minimum positions that OFPP outlined for an agency’s acquisition workforce, DHS identified additional disciplines that make up its overall acquisition workforce. The 11 disciplines that make up DHS’s acquisition workforce are:

· COR,

· Contract specialist,

· Industrial engineer/cost estimator,

· IT acquisition specialist,

· Logistician,

· Ordering official,

· Program financial manager,

· Acquisition program manager,

· Systems engineer,

· Technology management, and

· Test and evaluation.

Within DHS, the Chief Procurement Officer is responsible for creating the department-wide policies and procedures for managing and overseeing the acquisition function, as well as procurement.[12] This includes responsibility for the management and oversight of the department-wide acquisition career program, and the definition of certification requirements for the designation of persons qualified in all acquisition career fields. This officer also appoints an acquisition career manager to help identify and develop the acquisition workforce, including training and certification requirements, and other workforce development strategies. The acquisition career manager is also responsible for maintaining and managing consistent agencywide data on those serving in the acquisition workforce.

In addition to the Chief Procurement Officer, other DHS organizations and senior officials support the department’s acquisition workforce function:

· The Chief Human Capital Officer: Responsible for ensuring the integrity of the department’s personnel process and application of any policy related to the hiring of acquisition personnel.

· PARM: Responsible for developing and maintaining acquisition program management policy, procedures, and guidance processes, and provides support and assistance to department acquisition programs and the acquisition workforce. The Executive Director of PARM performs staffing analyses and assessments for major acquisition programs, as required, to identify workforce gaps and provide recommendations for staffing.

· Component heads: Responsible for, among other things, determining and obtaining the acquisition program management staffing and organizational alignment needed to manage acquisition programs based on the available resources and the type, size, complexity, and risks of the component’s respective acquisition portfolio.

· Component Acquisition Executives: Responsible for designing policies and processes to ensure that the best qualified persons are selected for acquisition program management positions. These senior acquisition officials also ensure that the component’s entire acquisition workforce, except for those in contracting, have the proper skills and qualifications and meet the mandatory education, training, experience, and competency standards established for each acquisition career level.

· Head of the Contracting Activity or designees: Responsible, in coordination with certain other individuals, for ensuring that only qualified federal personnel are assigned to DHS contracting or COR positions.

DHS has policies and guidance to manage its acquisition workforce. For example, DHS’s acquisition management staffing instruction outlines requirements for identifying sufficient numbers of trained and qualified program management staff who have the proper skills and experience in the appropriate disciplines.[13]

GAO’s Prior Work on Human Capital Management

We designated strategic human capital management, which includes strategic workforce planning, as a High-Risk area across the federal government in 2001.[14] This designation was due to the federal government’s long-standing challenges with strategically planning for its workforce. In particular, gaps in mission-critical skills, due in part to inadequate strategic workforce planning, persist across the federal workforce in fields such as acquisitions. Strategic workforce planning can help agencies address challenges facing the workforce by providing a mechanism to identify and fill—through hiring, training, and professional development—gaps in the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to oversee the acquisition process. This planning addresses two critical needs: (1) aligning an organization’s human capital program with its current and emerging mission and programmatic goals, and (2) developing long-term strategies for acquiring, developing, and retaining staff to achieve programmatic goals. To help address challenges with strategic workforce planning, in December 2003 we identified five key principles—or leading practices—that strategic workforce planning should address.[15]

DHS’s Acquisition Workforce Policies Generally Align with Government-wide Requirements

We found that DHS’s acquisition workforce policies, including those for its CORs and acquisition program managers, generally align with government-wide requirements established by OFPP. In particular, DHS has developed policies and guidance to manage the acquisition workforce based on the standards set forth by OFPP’s policy letter 05-01. As of September 2024, DHS was in the process of taking actions to update its certification policy for COs and other contracting professionals to align it with recent updates to government-wide CO training requirements.

DHS has two types of acquisition certifications: (1) federal acquisition certifications, which are recognized by all civilian agencies as evidence that a staff member meets foundational continuous learning, training, and experience requirements to perform certain acquisition functions, and (2) DHS acquisition certifications, which are limited to acquisition functions at DHS. DHS based its requirements for whether some staff were to hold certifications on the primary responsibilities of their positions and, in some cases, on government-wide requirements associated with those responsibilities. There are three levels of federal certification for CORs and acquisition program managers, which are described in detail below. In general, certification and training requirements increase from level I to level III as contract risks and complexity increase.

COR certification: Our review of DHS’s policies for COR certification and training found they align with OFPP policy for level II and III CORs. According to DHS acquisition workforce policy, DHS does not certify level I CORs because of the complexity of the department’s contract portfolio. DHS relies on Office of Management and Budget guidance to determine whether a contract is high risk and supports a major investment, and thus needs a level III certified COR. According to OCPO officials, COs are generally aware that certain types of acquisitions may present a significant risk. These can include cost reimbursement contracts, time-and-materials contracts and orders, and hybrid contracts. Table 1 provides a summary of how DHS’s requirements for its CORs align with government-wide requirements established by OFPP.

Table 1: DHS’s Requirements for Contracting Officer’s Representatives’ Certification and Training Align with OFPP’s Government-wide Requirements

|

Certification level |

Contract risk |

Required training hours |

Required experience |

OFPP and DHS requirements aligned |

|||

|

OFPP |

DHS |

OFPP |

DHS |

OFPP |

DHS |

||

|

I |

Low-risk contract vehicles |

DHS does not certify level I |

8 |

N/A |

0 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

II |

Contract vehicles of moderate to high complexity, including both supply and service contracts |

Other than high risk or Major Investment Contracts |

40 |

40 |

1 year |

1 year |

Yes |

|

III |

Contracts of moderate to high complexity that require significant acquisition investment. |

High risk or major investments as defined by Office of Management and Budget Circular A-11a |

60 |

60 |

2 years on contracts of moderate to high complexity |

2 years |

|

Legend: N/A = not applicable

Source: GAO analysis of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) information. | GAO‑25‑107075

aHigh risk or major investments as defined by the Office of Management and Budget Circular A-11 can include contracts that are other than firm-fixed-price (e.g., letter contract; cost type contract).

Program management certification: Our review of DHS’s policies for program management certification found that they also align with OFPP’s policies. DHS’s requirements for program managers’ certifications describe minimum competencies and years of experience deemed essential for successful program management. While OFPP policy allows agencies some discretion on the level of certification required for CORs to manage certain contracts, it specifies that acquisition program managers for major acquisition programs be level III certified within 12 months of being appointed.[16] Table 2 summarizes how DHS’s requirements for program managers align with the government-wide requirements established by OFPP.

Table 2: DHS’s Requirements for Program Managers’ Certification Align with OFPP’s Government-wide Requirements

|

Certification level |

Competencies |

Required experience |

OFPP and DHS requirements aligned |

||

|

OFPP |

DHS |

OFPP |

DHS |

||

|

I |

Achieve entry-level |

Level I entry-level |

1 year of project management experience within last 5 years |

Generally, 1 year |

Yes |

|

II |

Achieve mid-level and appropriate lower level |

Level II mid-level |

2 years of program or project management experience in last 5 years |

2 years |

|

|

III |

Achieve senior and appropriate lower level |

Level III senior-level |

4 years of years of program or project management experience which must include a minimum of 1 year of federal project or program experience within last 10 years |

4 years |

|

Source: GAO analysis of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) information. | GAO‑25‑107075

Contracting certification: In February 2023, OFPP transitioned its contracting certification program from three levels to a single-level certification based on the contracting competencies in the Department of Defense’s model. As of September 2024, DHS OCPO officials told us they made updates to the department’s contracting certification policy to align with recent changes, and were in the process of adjudicating feedback on the update. OCPO officials anticipated completing the policy in early 2025. Meanwhile, DHS has transitioned staff who previously achieved at least level I certification in contracting to the new single-level certification.

DHS has also established certification and training programs for the eight other disciplines it includes in its definition of the acquisition workforce. For example, the test and evaluation manager within a major acquisition program must have a level III certification in the test and evaluation career field.[17] In addition, in 2018, OFPP established a specialization in digital services for contracting professionals buying digital services since this skill is not part of the contracting certification curriculum. DHS’s program managers managing major IT investments are also required to have a specialization that requires additional training, experience, and continuous learning requirements. As a result, members of DHS’s acquisition workforce could pursue specializations in certain IT-related contracting areas.

DHS Staff Identified Workforce Challenges but DHS Has Not Assessed Effectiveness of Its Mitigation Efforts

DHS Staff Identified Challenges with Workload and Length of the Hiring Process

DHS acquisition staff we interviewed identified workload and the length of the hiring process as their most considerable challenges. Based on our review of DHS documents and selected position responsibilities, we found that some challenges were relevant to certain acquisition positions and tailored our questions accordingly.[18] For example, we asked acquisition program managers about any hiring related challenges because of their role in the hiring process. Other challenges were relevant to acquisition program managers, COs, and CORs (see table 3).

|

Challenge |

Definition |

Position(s) challenge is applicable toa |

||

|

Acquisition program manager |

Contracting officer |

Contracting officer’s representative |

||

|

Workload |

Excessive responsibilities, tasks, or multiple roles for acquisition staff |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Length of the hiring process |

Length of time associated with DHS or federal hiring processes for acquisition programs from position announcement to entering on duty, including security clearance checks |

ü |

— |

— |

|

Resource allocation |

Validating need, budgeting, selecting the appropriate kind of funding, obtaining positions, and awarding contracts |

ü |

— |

— |

|

Finding qualified individuals |

Difficulty finding and competing for candidates with required certifications, technical experience, specialized skillsets (e.g., IT, cybersecurity, contracting) or other position requirements (e.g., years of experience) |

ü |

— |

— |

|

Retention |

Inability to retain staff due to the competitive nature of the acquisition workforce, promotion potential, retirement, and workload |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Level of certification or training |

Lack of adequate training or certification offered at DHS to prepare staff for designated position(s) |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Staff Planning |

Identify the skills and competencies needed and track human capital goals to ensure programs have the right resources for the current and future workforce |

ü |

— |

— |

|

Communication |

Availability of communication channels and avenues to share innovations, challenges, and successes so that staff are aware of the resources available to them |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Performance management |

Leadership and managers clearly establishing roles and responsibilities; linking performance expectations to performance assessments; and providing reasonable performance expectations |

— |

ü |

ü |

Legend: ✓ = challenge is relevant for the position; — = challenge is not relevant for the position

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) information and prior GAO reports. | GAO‑25‑107075

aWhen GAO determined that a challenge was not applicable to a position, it did not ask staff in that position about it.

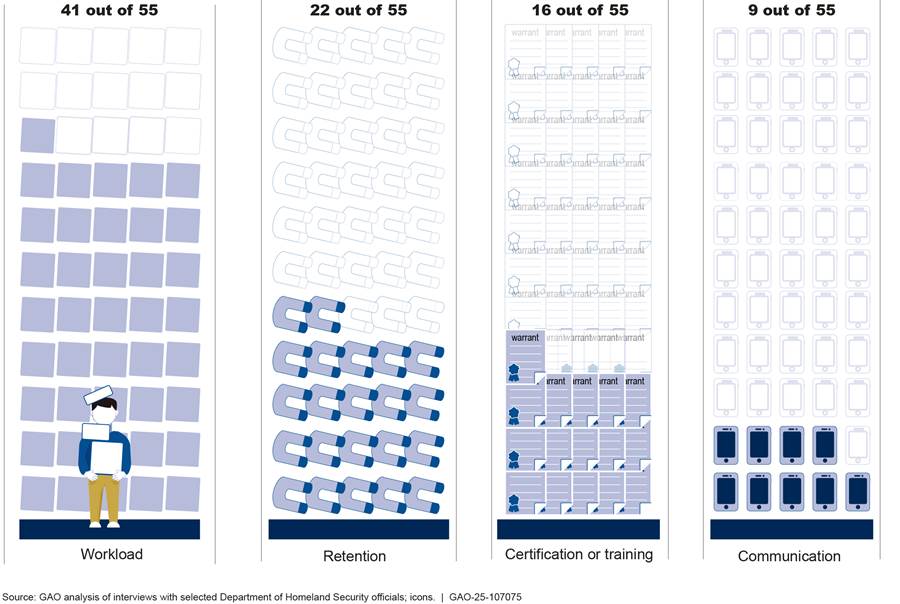

Among all three positions across our selected components, we found that workload was the most considerable challenge, according to the acquisitions staff we interviewed. Specifically, 41 of 55 acquisition staff we interviewed identified workload as a moderate or greater challenge. Most DHS acquisition staff we spoke with identified the other challenges for all positions—certification or training, retention, and communication—as somewhat or little or no challenge. See figure 1 for the most frequently identified challenges among our three key acquisition positions.

Figure 1: Workload Was the Most Frequently Identified Challenge by Three Key Acquisition Positions at DHS

Note: GAO asked 55 Department of Homeland Security (DHS) acquisition program managers, contracting officers, and contracting officer’s representatives about a list of challenges: From their perspective, over the past year, how much of a challenge, if any, does each of these areas pose for performing their responsibilities in supporting a level 1-3 acquisition program? GAO asked staff to respond with one of five possible response options: very great, great, moderate, somewhat, or little or no challenge.

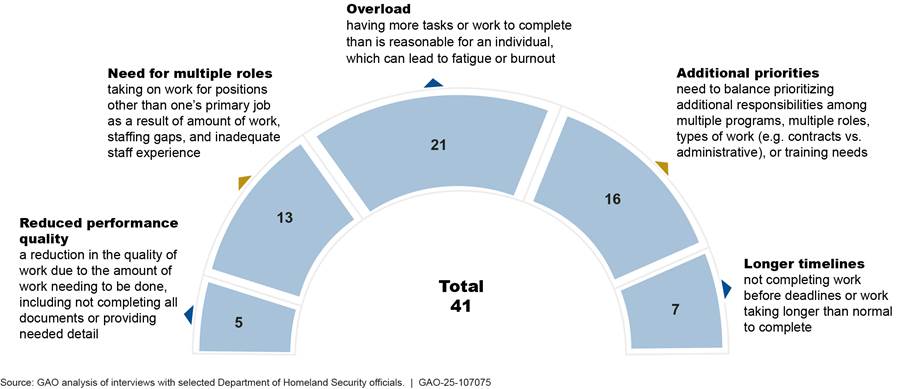

DHS acquisition staff we interviewed that identified workload as a moderate or greater challenge frequently cited task overload—having more work to complete than they thought was reasonable—and the need to take on multiple roles in addition to their primary responsibilities as the two primary effects of heavy workloads. For example, staff we spoke with said they had to fill multiple roles—such as simultaneously serving as a COR and an acquisition program manager—due to a lack of staff or staff with limited experience. Figure 2 illustrates the various effects of heavy workloads described by the acquisition staff we interviewed.

Figure 2: Effects of Heavy Workload Described by Selected Officials from Three Key DHS Acquisition Positions

Note: GAO asked 55 Department of Homeland Security (DHS) acquisition program managers, contracting officers, and contracting officer’s representatives about a list of challenges: From their perspective, over the past year, how much of a challenge, if any, does each of these challenges pose for performing their responsibilities in supporting a level 1-3 acquisition program? GAO asked staff to respond with one of five possible response options: very great, great, moderate, somewhat, or little or no challenge. GAO asked the 41 staff who identified workload as a moderate, great, or very great challenge to describe the effects of the challenge.

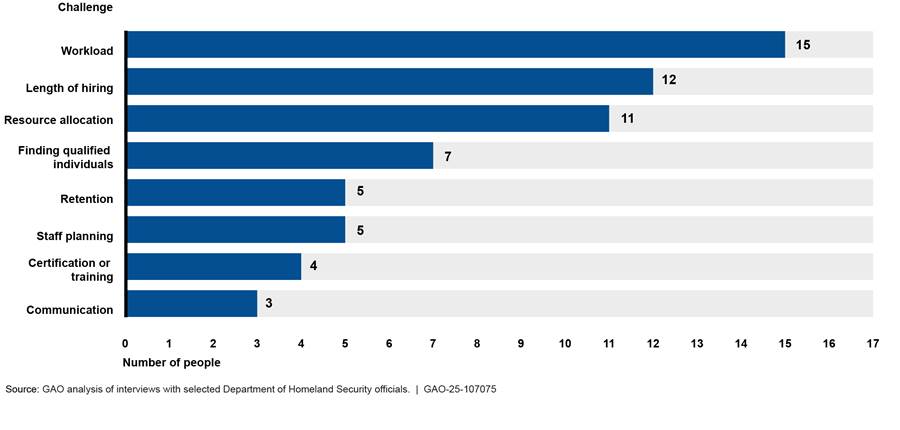

In addition to workload, among the acquisition program managers specifically, we found that the length of the hiring process and resource allocation constraints were the most frequently identified challenges from our selected components. Among the 17 DHS acquisition program managers we interviewed, 12 identified length of hiring and 11 identified resource allocation constraints as a moderate or greater challenge. Most acquisition program managers we spoke with identified the other challenges—certification or training, retention, communication, finding qualified individuals, and staff planning—as somewhat or little or no challenge. Figure 3 presents how acquisition program managers rated the challenges.

Figure 3: Workload and Length of the Hiring Process Were Most Frequently Identified as Challenges by Selected Acquisition Program Managers

Note: GAO asked Department of Homeland Security acquisition program managers about eight types of challenges: From their perspective, over the past year, how much of a challenge, if any, does each of these challenges pose for performing their responsibilities in supporting a level 1-3 acquisition program? GAO asked staff to respond with one of five possible response options: very great, great, moderate, somewhat, or little or no challenge.

Among acquisition program managers who identified length of hiring as a moderate or greater challenge, the most frequently mentioned effect was the loss of job candidates. For example, several acquisition program managers told us that they can lose numerous potential hires because applicants could not wait for the hiring process; the applicants accepted other offers before the component processed their applications. Most acquisition program managers also mentioned the security clearance process as contributing to long hiring time frames. For example, one acquisition program manager told us that it could take an additional 6 months for a candidate to start a new position because the candidate had no current or prior clearances.[19] Acquisition program managers also told us that the long hiring time frames resulted in staff shortages, which contributed to increased workload for existing program staff.

Among acquisition program managers that identified resource allocation constraints as a moderate or greater challenge, the most frequently mentioned effect was difficulty in planning. Program planning included anticipating the number of staff and budget amount a program will need to execute its requirements and goals years in advance. For example, one acquisition program manager told us that it is difficult to plan for IT programs where requirements and scope can change frequently within the 3-year time frame that program managers are expected to plan in advance. Acquisition program managers also told us that resource allocation constraints can result in, among other things, staffing gaps and increased reliance on contractor support, which could put the program at risk of losing institutional knowledge.

DHS headquarters and component acquisition leadership were generally aware of the challenges facing the DHS acquisition workforce. PARM’s fiscal year 2023 Annual Acquisition Staffing Analysis report identified recurring challenges for major acquisition program and component senior acquisition staff across DHS based on quantitative and qualitative data, including the acquisition staffing surveys.[20] For example, PARM’s report identified workload increases due, in part, to the length of the hiring process, which was reported to range from 3 to 18 months. The report also noted that the length of the hiring process can result in losing eligible candidates and lengthy staffing gaps, which can also increase existing workloads. Additionally, most DHS acquisition staff we interviewed stated that their component acquisition leadership was aware of the challenges they were facing. According to PARM’s report, these challenges present significant risks to programs, such as ensuring DHS has staff with the appropriate certification levels to accomplish their responsibilities.

DHS Has Taken Steps to Mitigate Workforce Challenges but Has Not Assessed These Efforts

DHS headquarters offices and components have implemented a variety of efforts to address workforce challenges, but have not assessed whether the efforts are aligned with identified challenges or if they are effectively mitigating them. DHS OCPO and PARM officials both identified several mitigation efforts aimed to address acquisition workforce challenges specifically related to training, certification, and hiring. Those efforts include the following:

· Rotation programs are developmental assignments within DHS for employees to broaden their skills, gain organizational knowledge, and enhance professional growth. For example, DHS’s Acquisition Professional Career Program is designed to recruit and develop talent across the acquisition workforce with an emphasis on contracting-related positions. This 3-year program enables participants to rotate through multiple DHS components, directorates, or offices.

· Detail programs are intra- and inter-departmental programs that offer professional and developmental opportunities across the federal government. In its 2023 Acquisition Staffing Analysis report, PARM identified detail programs as a leading practice for components. PARM noted that components could use detail programs to address staffing shortages, increase specialized skills, and provide staff with growth opportunities.

· Hiring events are large, in-person events that aim to fill many open positions for multiple disciplines within a component or across DHS.

· Mentoring programs are reciprocal relationships that provide experiences for personal and professional growth while sharing knowledge, leveraging skills, and cultivating talent. For example, DHS’s Education, Development, Growth and Excellence Mentor Program is a 9-month opportunity designed to leverage the talent and skills of the acquisition workforce by developing a network of relationships that facilitate workforce engagement and strengthen retention.

· Shadowing programs are practical knowledge transfer opportunities for participants to enhance their understanding of a job role.

· Professional development training are programs that provide resources that inform acquisition professionals about developments and leading practices to strengthen their skills. OCPO’s Executive Development Program for Acquisition Leaders is a 1-year program that provides executive-level training opportunities like these to skilled employees.

Senior acquisition and procurement officials at our selected DHS components also identified various mitigation efforts they use to address acquisition workforce challenges.

· Staff reorganization. Officials from three of our four selected components described reorganizing staff assignments to mitigate workforce challenges. For example, officials from one component said they relied on cross-matrixing staff—using staff with needed experience or certifications to support multiple programs—to provide temporary help when there are staffing or competency gaps.

· Streamlined hiring. Officials from two of our four selected components told us they have made efforts to streamline their role in the hiring process to shorten hiring time frames. For example, officials from one component told us they reduced the number of interviews and interview questions depending on the position and associated grade level.

· Acquisition professional development programs. Officials from three of our four selected components used acquisition-specific professional development programs that focus on recruiting and training staff to help mitigate workforce challenges. For example, officials from one component said they offered a training program for junior contract specialists to supplement on-the-job training and offer additional support for the technical challenges of being a contracting specialist.

· Automation. Officials from two of our selected components said that they used automated processes to address workload for contracting staff by automating tasks such as de-obligating unspent contract funds, uploading contract files into the Electronic Contract File System, and uploading congressional notifications to a DHS application.

We asked DHS acquisition workforce staff about the mitigation efforts identified by OCPO and PARM and the extent to which those efforts may effectively address or mitigate the identified challenges.[21] Some of the acquisition staff we spoke with noted positive aspects of DHS’s mitigation efforts and thought such efforts could help with certain challenges. For example, one staff member that participated in a rotation program said they learned IT skills and that the experience increased their work satisfaction and prevented burnout by allowing them to do something different. Other staff also noted that several of the efforts were useful for career development, especially for more junior staff with limited federal work experience.

Although some staff expressed favorable views, others had less favorable views or were largely unaware of the mitigation strategies.

· Unfavorable. Some staff expressed concern that some of the mitigation strategies can exacerbate workload challenges as the programs take staff away from one program to assist with others. For example, staff members across three of our selected components recognized that rotational and detail programs can be effective, but they can also add to the workload of the office from which a person is moved. Several staff did not think the mitigation strategies were effective in addressing the challenges they faced, including one acquisition program manager who said staff reorganization focused on cross-matrixing was a short-term solution that did not address broader departmental needs.

· Limited awareness. Some staff told us that they were either not familiar with the mitigation strategies or had no direct experience with them.

Based on our analysis, DHS’s mitigation strategies are not well aligned to the challenges facing the acquisition workforce. Our review of the goals of the mitigation efforts that OCPO identified as addressing challenges found that most are professional development programs intended to provide staff with knowledge and skills. These efforts are not clearly aligned with the workforce challenges DHS acquisition staff we spoke with identified as considerable, such as workload or the length of the hiring process.

The mitigation strategies PARM identified from the components in its 2023 Acquisition Staffing Analysis report also did not consistently align with identified workforce challenges. The report highlighted detail and rotational programs as component leading practices to address vacant positions and labor shortages. PARM officials told us that although detail and rotational programs are primarily designed for professional development, the programs are also beneficial in providing short-term relief for staffing gaps and added support for workload balancing. PARM officials stated that the mitigation strategies in the report were not intended to be in alignment with the challenge findings. Instead, PARM officials said they presented these efforts to share existing efforts across the department and reduce redundant labor on similar efforts. However, as mentioned earlier, some DHS staff we spoke with noted that the efforts shared by PARM—such as rotational and detail programs—can increase workload challenges.

Further, PARM’s 2023 report attributed excessive workload to program vacancies resulting from hiring challenges. PARM officials acknowledged that the components were best able to identify the root causes of workforce challenges since such challenges may be unique among different components, and the acquisition staff we spoke with cited other factors as the cause for workload issues. According to staff we interviewed who identified workload as a moderate or greater challenge, high volume of work (22 of 41) and limited number of staff (20 of 41) were the most frequently cited reasons for workload challenges.[22] One acquisition program manager told us that there is a need for solutions beyond those related to staffing, such as efforts to reduce tasks and workload on program officials. Staff also cited the complexity of their work and the need to focus time and effort on training inexperienced staff as two other factors creating workload challenges.

DHS headquarters offices and components have not assessed the effectiveness of their mitigation efforts in addressing workforce challenges because they have not developed strategies or methods to track performance measures. OCPO’s acquisition career manager is responsible for coordinating with acquisition leadership and the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer on human capital strategic planning for, among other things, recruitment, retention, and other human capital management issues affecting the acquisition workforce.[23] Further, OCPO officials told us that they track attendance numbers for their professional development programs, collect survey feedback on learning for training courses, and monitor overall certification percentages for the acquisition workforce. While DHS officials told us that the survey feedback they collect tracks learning increases achieved from training, they said that they do not otherwise track whether their programs better prepared staff to accomplish their responsibilities related to any challenge areas.

While the Executive Director of PARM is responsible for providing support and assistance to DHS acquisition programs and the acquisition workforce, PARM officials also stated that they were not tracking any metrics related to mitigation efforts because they were not responsible for those programs. Senior acquisition and procurement officials we spoke with at our selected components said they informally discuss the effectiveness of mitigation efforts at regular meetings with stakeholders, such as human capital staff, acquisition program managers, and acquisition leadership. However, these officials did not identify any formal way to track the effectiveness of their mitigation efforts.

We previously identified key principles for effective strategic workforce planning. These key principles state that agencies should develop strategies tailored to address gaps and evaluate progress toward reaching their human capital goals and the contribution of human capital activities toward achieving programmatic goals.[24] A strategy for evaluating progress toward human capital goals can help an agency determine whether it is meeting its workforce planning goals and identify the reasons for any shortfalls. For example, a workforce plan can include measures that indicate whether the agency executed its hiring, training, or retention strategies as intended and achieved its goals for these strategies.

Our past work has also highlighted strategies that agencies can use to develop measures, such as using logic models to demonstrate links to agency goals and selecting outcomes closely associated with the program.[25] OCPO officials agreed it would be beneficial to collect more metrics about their acquisition workforce mitigation efforts to ensure these activities are having the desired effect in accordance with human capital key principles. As of June 2024, OCPO officials told us they were considering collecting specific metrics based on program performance. However, they had not identified what these metrics will be or a time frame for beginning these efforts. Without a strategy to evaluate whether mitigation efforts are aligned with the intended challenges and to monitor whether efforts contribute to programmatic goals, DHS officials lack reasonable assurance the department is using the most appropriate tools to attract, maintain, and grow its acquisition workforce or whether those tools are achieving their intended purpose.

DHS Has Not Fully Evaluated Data Collection Methods or Collected Comprehensive Acquisition Workforce Data

DHS collects various acquisition workforce-related data and has taken steps to streamline data collection methods, but it has not identified if additional efficiencies could be gained or if its data collection efforts are meeting stated goals. Moreover, DHS’s current data collection efforts do not provide the department with comprehensive data on its acquisition workforce to inform decision-making.

DHS Has Streamlined Some Data Collection Efforts for Major Acquisition Programs but Has Not Identified Next Steps

Since 2016, PARM has required major acquisition programs and Component Acquisition Executive offices to submit annual staffing plans. Each plan provides a snapshot of the required positions and qualifications needed for programs to perform effectively and efficiently, and the extent to which these positions are filled. PARM officials review and report these data in staffing plan analysis reports, identifying any critical deficiencies and workforce gaps, and making recommendations for staffing. For example, PARM reported that approximately 15 percent or 115 of DHS’s total acquisition positions supporting major acquisition programs were unfilled in its fiscal year 2023 analysis. PARM developed its staffing plan analysis in part to address acquisition program management outcomes in our High-Risk series related to assessing and addressing that enough trained acquisition personnel were in place to support major acquisition programs at the department and the components.

In addition to the data collected in annual staffing plans, from fiscal years 2022 through 2024, PARM invested approximately $2.4 million into developing a web-based staffing model that requires regular data submissions from the components. Specifically, PARM used the annual staffing plans and a data collection form to gather input for the model. The model currently documents the acquisition work that needs to be conducted, who performed that work, and how much work each staff completed with respect to their assigned tasks. The model compares a program’s current year information against its prior year data, as well as to other major acquisition programs. Its output currently forecasts 1 year.

PARM officials described several intended uses and benefits of the staffing model. They stated that the model was intended to establish a baseline for the appropriate skill sets and staffing levels for major acquisition programs throughout the acquisition life cycle. The benefits of the model include an organized approach to identifying staffing needs and quantifying workload, among other things. PARM officials planned to use this model to generate staffing standards that can be applied to major acquisition programs regardless of component or program type and to bolster overall workforce trend analyses. The February 2022 memorandum describing the staffing model noted that once complete, the model will be used to justify resource requests, long-term program planning, cost estimating, and formulating appropriate program staff compositions for current and future programs.

In December 2023, PARM officials noted that the model’s output could be a helpful metric for programs to cite when considering workforce needs. In August 2024, these officials told us that components could use the model to support the fiscal year 2027 budget cycle, after PARM had collected 3 years of staffing data, which provided a reliable baseline needed to inform the model.

Several component officials we interviewed also cited potential benefits of the staffing model and said that it could be useful in supporting their workforce needs. For example, senior acquisition officials from U.S. Customs and Border Protection said they could use the model to justify the level of certifications needed for their programs and to budget for new positions. Senior acquisition officials from the Transportation Security Administration said the staffing model information could be used to justify resource requests, but that to do so PARM needed to collect additional staffing data for the model. Specifically, these officials said the workload information in the model is solely based on acquisition program documentation—such as acquisition program baselines or life-cycle cost estimates—which does not account for related work that is not tied to these products, such as talking to vendors. These officials said the staffing model would be more viable as a tool to inform budget needs if PARM officials incorporated this related work into the analysis.

Officials from the selected components in our review raised concerns about PARM’s data collection efforts for both its staffing plans and its staffing model. They noted that the dual data collection approach adds work and creates a burden. For example, U.S. Customs and Border Protection senior acquisition officials said the data call for PARM’s annual staffing plan diverted resources from their internal efforts to analyze their own workforce needs, including tracking position vacancies and collecting data on nonmajor programs. U.S. Coast Guard officials said the annual staffing data collection process repeated information in other reports and staffing and certification data that PARM or other DHS offices already received, and, as a result, were an administrative burden for them to provide.

The February 2022 memorandum about PARM’s staffing model acknowledged PARM’s data collection efforts were another task for program officials to complete in addition to the annual staffing plan data request. This memorandum and PARM’s 2022 Acquisition Program Staffing Analysis report identify the goal of streamlining the two data requests, and PARM officials have taken some steps toward that goal. PARM officials said they used the same application that supports the staffing model data call—the Federal Acquisition Staffing Tool—to collect annual staffing plan data for the first time in 2024. PARM officials also said they recently streamlined the two data requests by reducing the number of required staffing plan fields, integrating these required fields into the Federal Acquisition Staffing Tool, and synchronizing the two data sets to ensure they are accurate at the end of each fiscal year. PARM officials cited the lack of funding within the department as an obstacle to further streamlining their data collection efforts.

The February 2022 memorandum about PARM’s staffing model also noted that the effort adhered to DHS policies emphasizing that workforce requirements should come from models, where possible, to provide a credible and consistent method to justify the department’s staffing needs. In addition to PARM, another office within DHS established a staffing model—in fiscal year 2023, OCPO created and accredited a staffing model for the contracting officer and contract specialist positions. OCPO’s model is to be used to identify and guide staffing decisions and advocate for resources.

Despite the goals identified in PARM’s memorandum, PARM officials we spoke to expressed uncertainty about the resources available for the future of the model and have not determined next steps to take. For example, in June 2024, PARM officials told us they were uncertain about whether they would pursue accrediting the model due to funding constraints. However, in August 2024, PARM officials said they are currently resourced to sustain the staffing model and they intend to pursue DHS model accreditation during fiscal year 2025. PARM officials also said program officials can start using the model for resource planning and to support resource request processes, but they are not required to do so. Further, PARM officials told us that while they want to refine and operationalize the model to build data fidelity and ensure that programs can use it without assistance, they do not currently plan on adding any additional data that would increase the functionality of the model at this time. In addition, PARM officials told us they do not currently plan to extend the model’s forecasting past 1 out-year, which may limit the usefulness of its capabilities for budgeting, since DHS’s long range budget planning forecasts out 5 years.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that organizations should design the entity’s information system and related control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks.[26] Further, these standards state that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives. PARM has continued to work toward improving its efforts to assess the acquisition workforce supporting major acquisition programs. However, without identifying next steps for these efforts—including whether further efficiencies can be gained in its data collection efforts or what additional data or resources may be needed to achieve its stated goals—DHS lacks reasonable assurance that the information it collects supports the department’s or the components’ needs.

DHS Does Not Have Comprehensive Data on Its Acquisition Workforce

We found that DHS does not have comprehensive data on the size or demographics (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity) of its acquisition workforce. As previously noted, DHS’s definition of the acquisition workforce aligns with OFPP’s and includes COs, CORs, and acquisition program managers. In addition, DHS identifies staff in eight other disciplines as part of its acquisition workforce.[27] The DHS offices and selected components in our review told us they agreed with the department’s definition. However, these entities apply the acquisition workforce definition differently as it relates to the data they collect. Specifically,

· DHS’s OCPO collects data on all COs and contract specialists, to include staffing levels, attrition rates, certifications, and demographic data, but does not collect any data on acquisition program managers or CORs.

· DHS’s PARM collects data on the disciplines of personnel supporting major acquisition programs as part of its annual staffing plan data call. PARM considers staff supporting these programs from acquisition decision event 1—when a program or increment enters the analyze/select phase to validate needs—to Full Operational Capability as part of its workforce for staffing analysis purposes. PARM officials told us they do not collect demographic data as part of this effort.

· Acquisition and procurement officials from our selected components told us they collect data on the types of staff and certifications in both major and nonmajor programs. Officials representing three of the four components also consider staff in the post-Full Operational Capability/sustainment phase as part of the acquisition workforce.[28]

In addition to what is collected by OCPO, PARM, and the components, the Cornerstone data system contains certification and training data on DHS personnel, including those certified as acquisition program managers, CORs, and contracting professionals, including COs. The system also includes a field to identify members of the acquisition workforce. Cornerstone data are self reported and DHS officials identified limitations with the system. For example, senior acquisition officials and OCPO officials said that because Cornerstone is not connected to any human resource systems, it is difficult to track the status of individuals if they transfer agencies or vacate a position.

However, we found that Cornerstone data capture more acquisition workforce data than other collection tools in the department. According to data in Cornerstone, DHS staff had obtained approximately 16,000 certifications to fill CO, COR, or acquisition program manager roles as of December 2023.[29] The data collected by PARM and OCPO, however, represent a smaller portion of the acquisition workforce population, with PARM focused on major acquisition programs and OCPO focused on COs and contract specialists. For example, as of December 2023, Cornerstone identified 1,858 certifications for contracting professionals including COs. By comparison, OCPO identified 1,399 total COs and contract specialists in its November 2023 operational status report. PARM identified 89 COs and contract specialists for major acquisition programs in its fiscal year 2023 staffing plans.

PARM officials told us that the department does not know which or how many personnel fall under DHS’s 11 acquisition-related disciplines. While PARM officials collect staffing data for 10 of the 11 disciplines, these data are focused on major acquisition programs that have not yet reached sustainment. In August 2024, PARM officials told us that beyond the data they collect on the disciplines supporting major acquisition programs—and the COs and contract specialists that OCPO tracks—the department does not have a process or methodology in place to identify the personnel who are included in its acquisition workforce. These officials also said that because they do not have full information on the entirety of the acquisition workforce, it is difficult to identify the appropriate number and types of positions needed and develop talent within the department. In August 2024, PARM officials told us they are in the process of coordinating an effort to define, identify, and monitor DHS’s acquisition workforce, but it is in the early stages.

In addition to not having comprehensive data on the size and makeup of its acquisition workforce, DHS is not collecting demographic data for its CORs and acquisition program managers. DHS’s fiscal years 2022-2026 Acquisition Workforce Strategic Human Capital Plan identified a goal of hiring and retaining a diverse acquisition workforce. However, OCPO’s efforts to collect demographic data through the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer are focused on COs and contract specialists specifically, limiting DHS’s awareness of demographics for other acquisition positions and disciplines.

OFPP’s policy letter 05-01 states that, at a minimum, the acquisition workforce includes COs, CORs, program managers, and other acquisition specialists. The acquisition career manager is responsible for identifying and developing that workforce and for maintaining and managing consistent agencywide data in Cornerstone on those serving in the acquisition workforce. DHS’s instructions also designate the acquisition career manager as responsible for overseeing and managing the identification, development, and tracking of the acquisition workforce.[30] DHS’s instruction on acquisition program management staffing states that acquisition personnel are responsible for maintaining accurate certification, training, and accounting information in Cornerstone, such as identifying themselves as members of the acquisition workforce.

OCPO officials told us they are taking steps to make Cornerstone data more accurate to assist in collecting better data about the acquisition workforce. According to OCPO officials, they are in the process of updating Cornerstone data records manually after the transition from the legacy system, the Federal Acquisition Institute Training Application System, to Cornerstone in 2021. As part of this effort, OCPO has work underway to verify training and certification data, remove outdated data, and correct errors and inconsistencies, among other things. For example, OCPO officials told us they recently began to reconcile certification data in Cornerstone to correct records about staff who have left the agency or moved between components. In addition, they were working to ensure the appropriate staff were certified; otherwise, expired certifications would be revoked. OCPO officials said they completed the first phase of this process at the end of June 2024.

OCPO officials also told us they use the data collected from PARM on the major acquisition programs as additional data on the entirety of the acquisition workforce. However, OCPO officials acknowledged that these data would not include acquisition staff supporting programs in the sustainment phase of the acquisition life cycle or nonmajor programs. For example, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has 37 nonmajor programs that OCPO does not have complete visibility into because of how data at OCPO and PARM are being reported. Without taking additional actions to establish a methodology for collecting reliable, consistent, and comprehensive information on the personnel included in its 11 acquisition disciplines, DHS is at risk of not having sufficient information to inform its decision-making. This includes the risk of being unable to determine the skills and makeup of its current acquisition workforce, its future workforce requirements, or whether it is meeting its goal of having a diverse acquisition workforce.

Conclusions

Given the billions of dollars DHS invests in its diverse portfolio of acquisitions, having a sufficient, capable, and well-trained workforce is critical to effectively managing its investments. DHS has made progress addressing workforce issues by completing actions in its human capital area that were previously included in our High-Risk area for DHS’s acquisition management, among other actions. Yet the department can take additional steps to further improve its management of the acquisition workforce.

DHS has identified and implemented some efforts to support the needs of its acquisition workforce, such as shadowing and mentoring programs. However, without a strategy to evaluate whether these mitigation efforts are aligned to the key challenges facing the acquisition workforce—which include workload and the length of the hiring process—DHS cannot ensure that its mitigation strategies are effectively mitigating the challenges as intended, or if additional improvements are warranted.

Additionally, PARM’s development of a staffing model for major acquisition programs has the potential to better support DHS’s ability to plan for and justify staffing needs. As DHS continues to refine its acquisition workforce data collection efforts and the development of its staffing model, taking additional steps to identify greater efficiencies is key. Specifically, identifying what, if any, additional data and resources are needed will be critical to meeting the model’s goals of justifying resource requests and generating appropriate staff compositions for current and future programs.

Finally, while DHS officials told us they have begun to improve the accuracy of their acquisition workforce data, DHS has not developed a methodology that would enable the department to identify the individuals that are part of each of its 11 acquisition disciplines. Additionally, DHS has not completed actions to ensure it has accurate, comprehensive data on these personnel to inform its decision-making. With a better understanding of who is part of its acquisition workforce, DHS could leverage demographic information already collected within other parts of the department. Further, taking additional steps to improve its strategic acquisition workforce management will better enable DHS to ensure that its acquisition workforce is capable of supporting its current and future mission needs.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following four recommendations to DHS:

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the Under Secretary for Management develops a strategy to assess whether its mitigation efforts are aligned with the challenges facing the acquisition workforce and to monitor results, such as establishing and tracking performance metrics for the efforts it is using to address workforce challenges. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that as the Office of Program Accountability and Risk Management continues to refine its staffing model, that it continues to identify and implement greater process efficiencies in its data collection efforts on the workforce supporting major acquisition programs, and works with components to identify what, if any, additional data and resources are needed to meet the model’s intended goals, including justifying staffing needs and generating appropriate staff compositions for current and future programs. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the Under Secretary for Management establishes a methodology for identifying information about the personnel supporting the 11 DHS-defined acquisition disciplines that make up DHS’s acquisition workforce. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the Office of the Chief Procurement Officer identifies methods to ensure it maintains comprehensive data across all 11 disciplines that constitute the acquisition workforce, such as identifying additional acquisition workforce data from the components or requiring acquisition personnel to regularly update their records in Cornerstone. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DHS, the Office of Management and Budget, and the General Services Administration for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix II, DHS agreed with the second recommendation and identified steps it plans to take to address it. DHS disagreed with the first, third, and fourth recommendations, and raised questions about the methodology used to identify challenges, as discussed below. DHS and the General Services Administration also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. Specifically, we modified the first and third draft recommendations to include the Under Secretary for Management, as that position oversees the headquarters offices responsible for addressing our recommendations. The Office of Management and Budget had no technical comments on the draft report.

DHS did not agree with the first recommendation that the Under Secretary for Management develop a strategy to assess whether its mitigation efforts are aligned with the challenges facing the acquisition workforce and monitor results, such as establishing and tracking performance metrics for the efforts it is using to address workforce challenges. In its response, DHS stated it disagreed with the methodology we used to identify these challenges, and in particular, that asking a non-generalizable sample from 3 of DHS’s 11 acquisition disciplines did not include a diversity of roles within those disciplines. Further, DHS pointed out that our sample was limited to four components and included staff that worked on predominantly major acquisition programs. Lastly, DHS took exception to asking the staff that we interviewed to rate a list of challenges.

As we noted in our report, we believe our methodology provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. As we also noted in the report, DHS does not have comprehensive information on who is filling the 11 acquisition disciplines at the department level or the overall size of its workforce, which prevents a generalizable sample across all 11 disciplines from being identified. Moreover, we note in our report that our sample focused on program managers, contracting officers, and contracting officer’s representatives because these positions allowed us to assess DHS’s certification requirements against federal certification requirements. Further, to maximize our coverage of the DHS acquisition workforce, we selected components that had among the highest contract obligations and number of contracts and orders. As noted in our report, these four components account for about 63 percent of DHS’s obligations and 66 percent of DHS’s contracts and orders awarded for fiscal year 2023. We also chose components with a range of acquisition programs, and the staff we randomly selected to interview were split across major and nonmajor programs.

Additionally, as noted in our report, the challenges we reference were primarily identified by DHS, based on our review of DHS documents, including DHS’s Acquisition Workforce Strategic Human Capital Plans, PARM’s Acquisition Staffing Analysis Reports, and acquisition program survey data taken from seven components, among other things. From these sources, we identified factors that could be challenges. We provided staff with this list of challenges, and asked staff to tell us from their perspective, how much of a challenge, if any, each of the factors posed to performing their acquisition responsibilities over the past year. We also asked an open-ended question on whether they experienced any additional challenges that affected their ability to perform their responsibilities. We believe this methodology provides a sound basis for identifying the most significant challenges faced by the members of DHS’s acquisition workforce. Lastly, we recommended that the department develop a strategy for assessing whether its mitigation strategies address any challenges facing its acquisition workforce, which would include those DHS had identified through its own efforts.

However, DHS stated that OCPO will conduct an assessment to identify the unique challenges facing the DHS acquisition workforce and, if necessary, identify additional mitigation strategies that can be implemented with existing resources. While conducting an assessment and potentially identifying new or more specific challenges and mitigation steps is a positive step, we maintain that clearly linking any challenges with mitigation efforts and establishing and tracking performance metrics for those efforts would provide DHS assurance that they are achieving their intended purpose.

DHS concurred with the second recommendation to identify and implement greater process efficiencies in its collection of staffing model data and work with components to identify any additional data and resources needed to meet the model’s intended goals. PARM stated it plans to 1) increase efficiency in data collection, incorporating user-centric design, and regular web-based data submission from components; 2) evaluate the model’s effectiveness and define the future of the model, including accreditation based on available resources; and 3) provide us with an interim update on data collection by the end of June 2025. We will review PARM’s update and subsequent actions to determine if they meet the intent of the recommendation.

DHS did not agree with the third recommendation that the Under Secretary for Management should establish a methodology for identifying information about the personnel supporting the 11 acquisition disciplines. In its response, DHS stated that the acquisition certification program—Cornerstone On Demand—managed by OCPO serves as the methodology for identifying personnel supporting the 11 acquisition disciplines. However, Cornerstone is a data source for certification and training information and not a methodology for identifying staff that are currently serving in an acquisition discipline. In addition, during the course of our review, DHS officials stated that there are limitations with Cornerstone data because the information is self-reported, and that just because an individual is certified in a discipline does not mean they currently hold an acquisition position. DHS officials also noted, as we explain in our report, that their way of identifying the acquisition workforce may not account for all staff performing acquisition duties. Their assessment aligns with our finding that DHS does not have a way to accurately identify who is or is not serving in each of the 11 disciplines.

DHS also noted in its response that it disagrees that it is at risk of not having sufficient information on its acquisition workforce to inform decision-making. DHS stated that it can leverage data from the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer and the Office of Personnel Management’s FEDSCOPE to track metrics like retention, attrition, and diversity. These data sources, however, do not provide information about the acquisition workforce outside of the 1102 job series, which is specific to contracting staff such as contract specialists and contracting officers. For example, officials from the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer told us that, while they collect demographic data for DHS’s entire workforce, they cannot provide demographic data specific to the DHS acquisition workforce because of limitations with job series information for acquisition positions. Additionally, PARM officials stated that, outside of the 1102 series and major acquisition staff, DHS has no way to track which staff members are performing acquisition functions and whether they are certified. In its 2023 Acquisition Staffing Analysis report, PARM noted as a challenge that many staff filling temporary roles due to vacancies do not hold the appropriate certification, an issue that would not be identifiable in Cornerstone without first knowing that an individual is serving in an acquisition discipline.

However, DHS stated in its response that OCPO will meet with OFPP to discuss management of its acquisition workforce. In addition, DHS noted that, if OCPO learns that a DHS employee is performing acquisition duties for a major program but is not identified as a member of the acquisition workforce in Cornerstone, it will work with PARM and responsible Component Acquisition Executives to ensure the individual becomes a member of the acquisition workforce at an appropriate certification level. While these are positive steps, we continue to believe that first establishing a methodology to identify information on who is serving in acquisition disciplines is critical to knowing the skills and make-up of DHS’s current acquisition workforce to inform the department’s current and future human capital decisions.