FISHERY DISASTER ASSISTANCE

Process Is Changing, but Challenges Remain to Improve Timeliness and Communication

Report to the Chairman of the Subcommittee on Coast Guard, Maritime, and Fisheries, Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

Reissued on June 25, 2025, to correct information in the sidebar on page 22 on the Snow Crab Disaster.

For more information, contact Cardell Johnson at johnsoncd1@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107076, a report to the Chairman of the Subcommittee on Coast Guard, Maritime, and Fisheries, Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, U.S. Senate

Process Is Changing, but Challenges Remain to Improve Timeliness and Communication

Why GAO Did This Study

Marine fisheries are critical to the nation’s economy, generating $321 billion in production sales and supporting approximately 2.3 million jobs in 2022. The number of fish caught and revenue generated can be subject to disasters, such as hurricanes or oil spills. When a disaster occurs, an eligible entity—such as a Tribe, state, or territory—may request federal assistance from the fishery resource disaster program to help fishers and the community recover.

GAO was asked to review various aspects of this program. This report addresses, (1) the process to provide assistance; (2) the number of disaster requests from January 2014 through June 2024; (3) challenges with the program; and (4) GAO’s past work on selected disaster-related assistance programs and how they compare.

GAO reviewed relevant laws, NMFS policies and documents, and NMFS data on fishery resource disaster requests submitted from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2024. GAO interviewed NMFS officials and stakeholders from 10 states, five tribes, and 11 fishing industry groups and others, selected because of their experience with the program and to reflect different regions. GAO also conducted site visits to Alaska and Louisiana.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations, including that NMFS provide more detailed information to stakeholders about the fishery resource disaster process and assess if staffing capacity is sufficient to administer the program. NMFS agreed with our recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Department of Commerce’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) is responsible for administering the fishery resource disaster program. The process to provide assistance and disburse funds involves several phases. Since January 2014, NMFS received 111 fishery disaster requests. For 56 of the most recently approved requests, NMFS took between 1.3 years and 4.8 years to disburse $642 million. Changes made by 2022 legislation added timelines to the steps; if followed and funding is available, the process should take a little over a year.

Stakeholders cited program challenges like long processing times for requests and inadequate communication about request status. NMFS started to implement the timelines created by the 2022 legislation and use a new data system to track requests. But access to this system is limited. Granting access to NMFS officials working on the program could help them respond to questions about request status. Tribal and state officials told GAO they would like more detailed information on the process, including what to include in requests and spend plans. Providing more detailed information on its website would better inform requesters about the information they need to submit. NMFS’ workload has increased to implement the statutory timelines added in 2022, but NMFS has not assessed staffing levels for the program. Assessing staffing capacity would help NMFS ensure it has sufficient staffing to administer the program.

Some stakeholders said the fishery resource disaster program could learn from other federal programs. GAO reviewed its past work on four disaster-related assistance programs with various design features identified and programmatic challenges compared with the fishery program. Design features included eligible uses of assistance and source of program funding. For example, under the federal crop insurance program, farmers receive financial protection against losses. However, the federal government heavily subsidizes this program and its high cost is a challenge. GAO has made suggestions to Congress to address the program’s costs, but they have not been implemented.

Abbreviations

|

CDBG-DR |

Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

FRDIA |

Fishery Resource Disasters Improvement Act |

|

HUD |

Department of Housing and Urban Development |

|

Magnuson-Stevens Act |

Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act |

|

NFIP |

National Flood Insurance Program |

|

NMFS |

National Marine Fisheries Service |

|

NOAA |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

SBA |

Small Business Administration |

|

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 30, 2025

The Honorable Dan Sullivan

Chairman

Subcommittee on Coast Guard, Maritime, and Fisheries

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

Dear Mr. Chairman:

Commercial and recreational marine fisheries are critical to the nation’s economy, generating $321 billion in sales and supporting approximately 2.3 million jobs in 2022, according to a report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).[1] Fisheries also provide critical subsistence resources for many Indigenous communities who may rely on marine resources for food, cultural connection, and economic security.[2]

The number of fish caught and revenue generated varies each year, as fisheries depend on the productivity of the environment and can be subject to events that can cause sudden and unexpected losses. These events include hurricanes, oil spills, marine heatwaves, and harmful algal blooms, which can decrease the supply of fish or inhibit the ability of fishers to access necessary equipment, like boats, or areas for fishing. These events can affect multiple states and result in large economic or other impacts for affected communities. For example, the 2019 Gulf of Mexico Freshwater Flooding disaster affected Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. In Louisiana, the disaster caused long-term flooding and led to the opening of the Bonnet Carré Spillway twice in 2019, which decreased the salinity levels in the local coastal waters and caused revenue losses for shrimp, crab, and other fisheries. The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries reported there were economic losses of over $101 million for these fisheries.[3]

In response to an event resulting in such losses, under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (Magnuson-Stevens Act),[4] as amended, an eligible entity, such as a Tribe,[5] state, or territory, may submit a request for a determination by the Secretary of Commerce about whether a fishery resource disaster has occurred.[6] If a positive determination is made and funds are allocated for a disaster, fishery resource disaster assistance can be used for activities such as habitat restoration, infrastructure repairs, research, or direct assistance to the affected fishers, fishing community, or businesses. NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) administers the fishery resource disaster program.

Stakeholders in the fishing industry have raised concerns about the administration of the program, and the time it takes to review requests and disburse funds to those affected by disasters. In addition, Congress has passed laws in recent years to make changes to the program. For example, in December 2022, the Fishery Resource Disasters Improvement Act (FRDIA) amended the Magnuson-Stevens Act to, among other things, add timelines for certain steps in the fishery resource disaster process.[7] In February 2025, we added Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance to our High-Risk list because of the need for federal agencies to deliver assistance as efficiently and effectively as possible while also reducing their fiscal exposure.[8]

You asked us to review various aspects of the fishery resource disaster program and compare it to other disaster programs. This report (1) describes the fishery resource disaster process, including recent changes; (2) describes the number of fishery resource disaster requests submitted from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2024, amount of funding disbursed, and time needed to disburse the funding; (3) examines stakeholder-reported challenges related to the fishery resource disaster program and what NMFS has done to address them; and (4) describes our past work on selected federal disaster-related assistance programs to provide some information on how they compare with the fishery resource disaster program.

To describe the fishery resource disaster process, we reviewed relevant federal laws, including the Magnuson-Stevens Act and FRDIA. We also reviewed NMFS’ policy and procedure documents related to fishery resource disaster assistance. In addition, we interviewed officials responsible for administering the program, including officials at NMFS headquarters, all five NMFS regional offices, and all three of the interstate marine fisheries commissions.[9]

To describe the number of fishery resource disaster requests, we analyzed NMFS data for requests received from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2024, the most recent period for which data was available at the time of our analysis. These data included information such as who requested the disaster assistance, which fishery was affected, the date of request, the date of Commerce’s disaster determination, and the date and amount of funding that was disbursed to the requester. To assess the reliability of the data, we reviewed relevant documentation, spoke with NMFS officials responsible for maintaining the data, and conducted logic testing. We determined the data for the 10.5-year period were reliable for our purposes to describe the number of fishery resource disasters and their characteristics. We also selected a non-generalizable sample of funding awards for 14 disaster requests for a more in-depth review of how disaster funding was used. We selected one request for fishery resource disaster assistance submitted by each of our selected states and Tribes.[10]

To examine the stakeholder-reported challenges with the fishery resource disaster program, we interviewed a non-generalizable sample of tribal, state, intertribal, local, and industry stakeholders about their experiences with the program. Specifically, we interviewed officials from four selected Tribes and 10 selected states, representatives from two intertribal organizations, and officials from three local governments. We later interviewed a fifth Tribe for balance and to describe experiences in remote Alaska.

We also interviewed representatives from 11 selected fishing industry organizations representing affected fisheries in the Alaska and Southeastern NMFS regions.[11] We conducted site visits to Alaska and Louisiana to meet with state officials, local government officials, and fishing industry representatives from fisheries that received fishery resource disaster assistance. To identify what NMFS has done to address the challenges that stakeholders identified, we interviewed NMFS headquarters and regional officials to discuss their efforts. We also reviewed documents that provided details on these efforts, such as NMFS’ guidance documents and information provided to requesters.

To describe selected disaster-related assistance programs, we reviewed our previous relevant reports and consulted with our staff involved in disaster-related assistance work. We selected four programs for closer examination based on the eligibility of businesses to apply for assistance; type of assistance offered by the program, such as grants, loans, or insurance; and factors including the number of our previously published reports related to those programs. The selected programs are Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR), Small Business Administration’s (SBA) disaster loan program, and U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) crop insurance program.[12]

We reviewed our relevant reports published from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2024, and publicly available information to identify the design features of these programs and how they compare with the fishery resource disaster program. We also reviewed the matters for congressional consideration and recommendations for executive action we made for these programs in past relevant reports.

For more details about our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

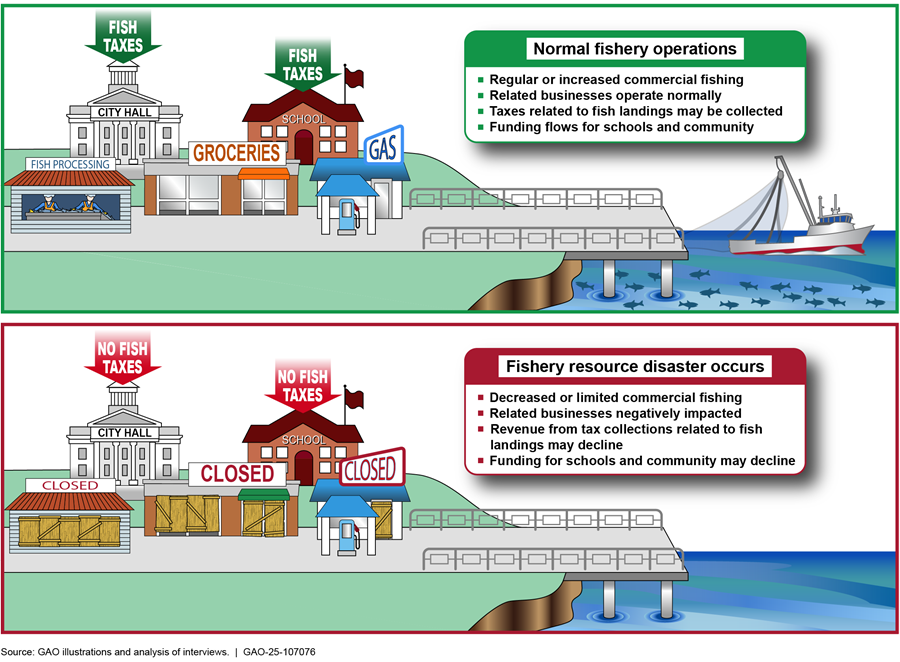

Fisheries play an essential role for Tribes and coastal economies, providing jobs for fishers, fish processors, and related maritime-support industries, such as boat construction and repair. In many communities, the fishing industry is a key economic driver and source of tax revenue. When a fishery resource disaster takes place, there can be large economic impacts on communities (see fig. 1). For example, in the community of King Cove in Alaska, the closure of a processing plant resulted in an estimated loss of 70 percent of the community’s revenue, according to a 2024 NMFS report.[13] Further, the community delayed multiple projects because it relied on the processing facility to purchase hydroelectric power, water, and provide solid waste disposal services.

Note: Some states impose taxes related to fisheries landings and processing. For example, Alaska imposes a fishery resource landing tax on certain fishery resources landed in the state. A percentage of the revenue from the landing tax is then distributed to eligible municipalities.

Many Tribes can face difficulties as a result of fishery disasters, as they can rely on fisheries to meet their subsistence, cultural, and religious needs. For example, in the Kuskokwim River region in Alaska, rural Alaska Native villages sell, barter, and trade salmon resources to support their livelihoods.[14] Disasters, resulting in depleted salmon runs in 2020, 2021, and 2022 for coho, chum, and chinook salmon prevented these communities from participating in these traditional exchange practices. According to the National Congress of American Indians, many rural Alaska Native individuals affected by disasters have been unable to meet their basic needs, including food, electricity, gasoline, and other expenses.[15]

The fishery resource disaster program is governed by the process and requirements outlined in the Magnuson-Stevens Act, as amended.[16] The fishery resource disaster program is one of many federal programs and initiatives that provide resources to communities following disasters. Federal programs have various design features, including offering a variety of types of assistance, such as loans, insurance, or grants.

Recent Statutory Amendments Established Timelines for the Fishery Resource Disaster Process

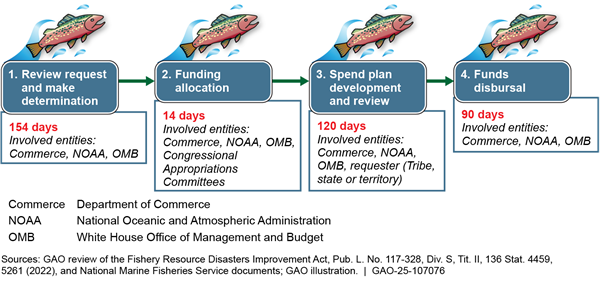

The fishery resource disaster process involves four main phases: (1) determine whether a fishery resource disaster occurred, (2) allocate funds, (3) develop and review the requester’s spend plan, and (4) disburse funds. FRDIA’s recent amendments to the Magnuson-Stevens Act established statutory timelines for the process, revised statutory definitions, and specified additional detail about process requirements.[17]

Fishery Resource Disaster Process Starts with Determination of Whether a Disaster Occurred and Ends with Disbursement of Funds

According to our review of the Magnuson-Stevens Act, as amended, and NMFS’ guidance, the fishery resource disaster process involves four main phases.

· Phase 1: Determine Whether a Fishery Resource Disaster Occurred. In general, the process typically begins when a request is submitted by a state governor or official resolution of a Tribe to the Secretary of Commerce to determine whether a fishery resource disaster has occurred.[18] This request is to include information needed to support a finding of a fishery resource disaster, including significant 12-month revenue loss or negative subsistence impact for the affected fishery.[19] After receiving the request, the Secretary sends a letter to the requester acknowledging receipt of the request. According to NMFS guidance, NMFS headquarters drafts a decision memo to aid the Secretary’s review based on information about the disaster prepared by the relevant NMFS regional office.[20] The Secretary reviews the request. Following the Secretary’s decision, according to NMFS guidance, the decision is sent to the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for review and the requester is notified of the Secretary’s determination.

· Phase 2: Allocate Funds. The amount of funding, or allocation, provided for a fishery resource disaster is determined in one of two ways. First, if appropriated funds are available at the time of a positive disaster determination, NMFS can combine the allocation proposal with the draft decision memo.[21] Second, if appropriated funds are not available, NMFS completes the determination phase first, and then waits to develop the allocation proposal until the agency receives an appropriation.[22] The Secretary then notifies the public and representatives of the affected fishing communities of the allocation decision and the availability of funds. NMFS officials said that the timing and scope of appropriations for fishery resource disasters are up to Congress.[23] As a result, the amount of time that passes between when a positive determination is made and when Congress appropriates funding can vary.[24]

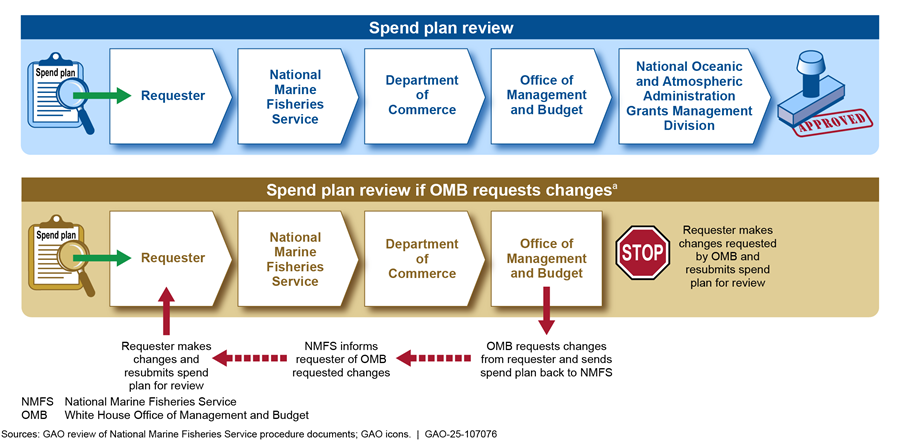

· Phase 3: Develop and Review the Requester’s Spend Plan.[25] To receive an allocation from available funding, the requester must submit a spend plan to NMFS, according to NMFS guidance.[26] A spend plan outlines how the requester will use the allocated funds, such as direct assistance to fishers or other final recipients, infrastructure improvements, or research activities related to reducing adverse impacts to the fishery.[27] Under amendments to the Magnuson-Stevens Act enacted in January 2025, the Secretary is to review a spend plan to determine whether it is complete and provide notice within 10 days.[28] Once a spend plan is determined to be complete, it is reviewed by multiple entities, including NMFS, Commerce, and OMB, according to NMFS guidance. If any reviewers request changes to the spend plan, NMFS informs the requester and returns the spend plan to the requester to make changes (see fig. 2 for an example of this scenario). Once OMB approves the spend plan, NMFS submits the spend plan to NOAA’s Grants Management Division to review and approve the award package and disburse funds.

aComments by any entity reviewing the spend plan, such as NMFS, Commerce, or OMB, can necessitate that the requester revise and resubmit the spend plan for review. This figure shows an example scenario of OMB’s comments on the spend plan requiring the requester to revise and resubmit the spend plan for review and approval by the entities depicted in the “Spend plan review” of the figure.

· Phase 4: Disburse Funds to Requester and Final Recipients. NOAA’s Grants Management Division disburses funds to the requester or relevant entity, generally in the form of a grant or cooperative agreement.[29] The requester manages the process of distributing funds to final recipients for eligible uses, such as direct assistance or executing projects in accordance with the approved spend plan.[30] In some cases, the relevant interstate marine fisheries commission implements the spend plan by distributing funds on behalf of the requester, as outlined in the approved spend plan. For example, the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission distributes fishery resource disaster assistance for state and tribal requesters along the West Coast.

Statutory Changes in 2022 Added Timelines, Revised Definitions, and Specified Additional Details About Process Requirements

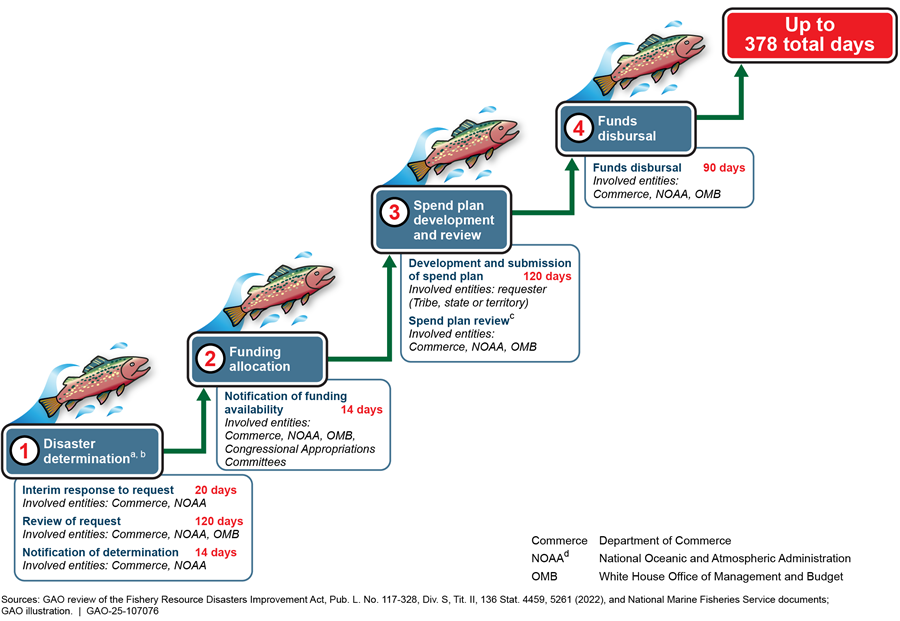

Among other things, FRDIA added statutory timelines, detailed definitions, revenue loss thresholds, and specific information requirements for fishery resource disaster requests. If all the timelines specified in FRDIA are met, the amount of time from when the Secretary acknowledges a complete request to disbursement of funds to the requester should generally be no more than 378 days (see fig. 3).[31] Prior to FRDIA’s amendments, the Magnuson-Stevens Act did not specify statutory timelines for the fishery disaster review process.

Figure 3: Statutory Timelines for the Fishery Resource Disaster Process Established by the 2022 Fishery Resource Disasters Improvement Act

This is a simplified figure of the fishery resource disaster process, and corresponding timelines. It assumes, for example, that the initial request and spend plan are both complete when initially submitted, as well as that appropriations are available when a determination is made. The complete process, including timelines, is set forth at 16 U.S.C. 1861a(a). Additionally, this figure does not reflect amendments made in January 2025 by the Fishery Improvement to Streamline untimely regulatory Hurdles post Emergency Situation Act, which are described elsewhere in this report.

aIn general, a requester can submit a request for a fishery resource disaster determination for up to 1 year (365 days) after the date of the conclusion of the fishing season. See 16 U.S.C. 1861a(a)(3)(A)(ii). The 365-day period the requester has to submit a request is not included in our count of the total number of days for the process.

bRequesters are typically Tribes, states, or territories. Requesters can also include any other comparable elected or politically appointed representative as determined by the Secretary. See 16 U.S.C. 1861a(a)(3)(A)(ii).

cA requester with an affirmative fishery resource disaster determination is to submit a spend plan to the Secretary not more than 120 days after receiving notification that funds are available. 16 U.S.C. 1861a(a)(6)(D)(i).

dVarious offices within NOAA, such as NMFS (including its Office of Sustainable Fisheries), the Grants Management Division, and others, are involved in the fishery resource disaster process. Not all NOAA offices are involved in every step of the process depicted in this figure.

FRDIA did not specify a timeline for the requester to distribute funds to the final recipients, such as fishers or communities affected by the fishery resource disaster, after the requester receives the funds from NMFS.[32] Additionally, while NMFS coordinates with OMB during several phases of the funding process, prior to the January 2025 FISHES Act amendments, the Magnuson-Stevens Act did not address OMB’s role or include any timelines for OMB involvement. During our review, we reached out to OMB officials about the review timelines they follow, if any, but we did not receive a response. In January 2025, the FISHES Act amended the Magnuson-Stevens Act to explicitly allow for OMB review of a completed spend plan—provided the review does not delay the 90-day timeline for the Secretary to make funds available after receiving a complete spend plan.[33]

FRDIA also added and amended some statutory definitions and added more detail regarding requirements for the program.[34] For example, FRDIA

· added a statutory definition of “allowable cause” for the purposes of a fishery resource disaster determination,[35]

· added a statutory definition of “fishery resource disaster,”[36]

· delineated what information is to be included in a complete request for a fishery resource disaster determination and what information is to be included in a spend plan, and

· clarified which entities are eligible to submit requests for fishery resource disaster determinations.[37]

From 2014 to 2024, NMFS Received 111 Disaster Requests and It Generally Took Over 3 Years to Disburse Funds for Approved Requests

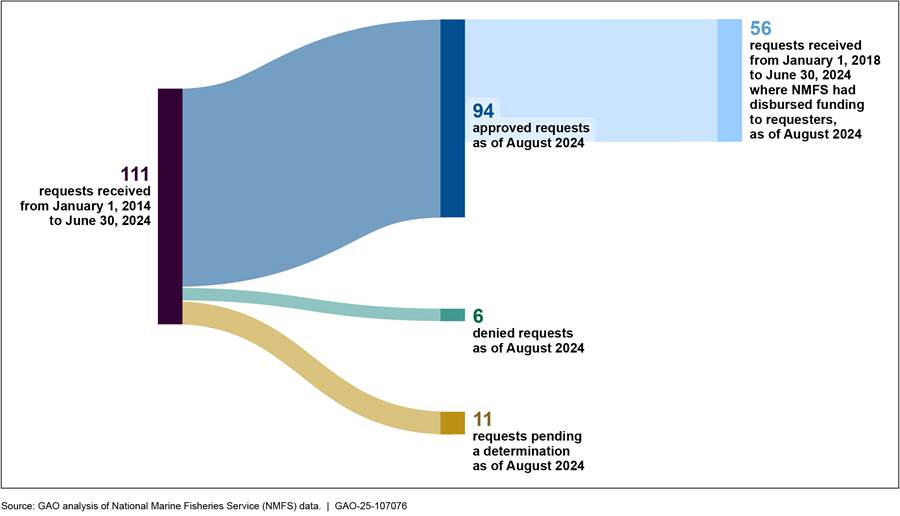

From January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2024, we found that NMFS received 111 requests for fishery resource disaster assistance; 94 of these had been approved at the time of our review. Available data for the 56 approved requests received since 2018 shows that NMFS disbursed over $642 million to these requesters and that it took a median of 3.4 years to disburse funds from the time a request was received. Additionally, our review of 14 selected fishery resource disaster requests found that most of the funds were used for direct payments to fishers.

NMFS Received 111 Total Requests during January 2014 through June 2024 from 22 Tribes, 19 States and 2 Territories

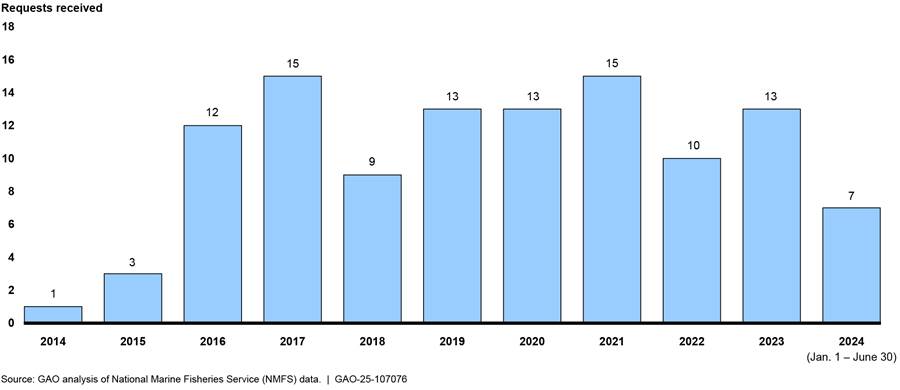

From January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2024, NMFS received 111 individual requests for fishery resource disaster assistance, according to our analysis of NMFS data.[38] Of these requests, 94 were approved, six denied, and 11 were pending a decision, as of August 2024.[39] NMFS received at least nine requests for fishery resource disaster assistance each year from 2016 to 2023 (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Annual Breakdown of 111 Requests for Fishery Resource Disaster Assistance Received by NMFS, by Calendar Year, January 1, 2014–June 30, 2024

Twenty-two Tribes, 19 states, and two territories submitted these requests. Alaska submitted the most fishery resource disaster requests (25), followed by California (10), Yurok Tribe (seven), Florida (six), and Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe (five).[40]

Data for 56 Requests Approved Since 2018 Shows That It Generally Took Over 3 Years for Funds to be Disbursed After NMFS Received a Request

NMFS officials told us that their funding data were more reliable for requests received in 2018 or later, and we confirmed this during our work.[41] As a result, we more closely examined 56 requests beginning in 2018 for which funding had been disbursed at the time of our review in August 2024 (see fig. 5). For these requests, our analysis found it took NMFS a median of 3.4 years to disburse funds after requesters had submitted a request for a fishery resource determination.[42] The amount of time to disburse funds ranged from 1.3 years to 4.8 years. Collectively, NMFS disbursed around $642 million to these requesters.[43] The amounts disbursed per request ranged from $116,806, to Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe for a Coho salmon disaster requested in 2019, to around $97 million, to Alaska for a Bering Sea crab disaster requested in 2022.

Figure 5: Status of Fishery Resource Disasters Requests Received from January 1, 2014 to June 30, 2024

Note: We based the information in this figure on the status of fishery resource disaster requests NMFS received from January 1, 2014 to June 30, 2024, at the time of our review in August 2024.

Most Funds for 14 Selected Disaster Requests Were Provided Through Direct Payments to Final Recipients

Our review of spend plans, status reports, and information from the requesters for our 14 selected disaster requests found that requesters received around $153 million in fishery resource disaster assistance.[44] Of that amount, requesters provided over $117 million, or about 77 percent of the total funds, as direct payments to final recipients, such as fishers and processors. For example, around $54 million was disbursed for a pink salmon disaster in the Gulf of Alaska in 2016, of which over $47 million was used for direct payments.[45] Final recipients with whom we spoke said they commonly use direct payments for boat maintenance and repairs and to pay off fishing-related debts or other expenses.

Final recipients used the remaining $36 million for the 14 selected disaster requests for various research and infrastructure projects, among other things. For example, California received funding for the California Pacific Sardine disaster from 2017 to 2019 and provided $738,426 to an industry group to conduct aerial and acoustic surveys of sardine populations. See appendix II for more information on the 14 selected disasters.

Stakeholders Cited Program Challenges Related to Processing Times and Communication, and NMFS Has Taken Some Actions to Address These

State, tribal, municipal, and industry stakeholders cited challenges with requesting and receiving fishery resource disaster assistance. These challenges include long processing times to receive assistance and inadequate communication as requests are going through the review process. FRDIA’s amendments established timelines for the review process and while our analysis found time frames for the determination phase have shortened, it is too soon to assess the full impact of FRDIA on processing times. In addition to implementing FRDIA, NMFS has taken some other actions to address these and other challenges. However, it could do more to improve the program, such as by communicating more effectively with requesters and other stakeholders. NMFS faces an increased workload due to its implementation of the timelines required under FRDIA. While it has taken some personnel actions to address this change in workload, the agency has not yet assessed its staffing needs.

Stakeholders Cited Challenges with Long Processing Times and Inadequate Communication

Stakeholders cited two main challenges related to the program—namely, long processing times to receive assistance and inadequate communication from NMFS about the status of requests. For example, officials we interviewed from nine states and three Tribes said the review process takes too long.[46] In addition, representatives from five industry groups said the funds are often no longer useful by the time they are distributed to final recipients, and some fishers or processors have gone out of business or transitioned to another job by that time.

|

Effect of a Snow Crab Disaster on Saint Paul, Alaska The City of Saint Paul, a majority Alaska Native community on an island in the Bering Sea 300 miles west of mainland Alaska, saw an 88 percent reduction in allowable catch of snow crab, from 45 million pounds in the 2020–2021 season to 5.6 million pounds in 2021–2022 season. According to city officials, the local government experienced a $2.1 million reduction in tax revenues stemming from the snow crab disaster in 2022. This funding made up more than 60 percent of the city’s general fund. A city official said that without this tax revenue, the city has struggled to maintain essential municipal services. For example, the city government’s workforce has gone from 41 staff down to 16, and the city laid off police officers and its public works director in an attempt to remain financially solvent. Additionally, the city has proposed raising utility rates on residents for water and refuse disposal services. In December 2023, the city’s Mayor, with input from the co-located tribal government, submitted a disaster request for the Alaska Bering Sea Snow Crab Fishery. In January 2024, the Governor of Alaska also submitted a disaster request for this fishery. The National Marine Fisheries Service approved these requests in April 2024 and allocated $39.5 million. The spend plan for this disaster remains under development as of April 2025. Once the spend plan is finalized and approved, payments to final recipients, which may include crab harvesters, processors, and communities, will be determined. Source: GAO analysis of National Marine Fisheries Service documents and interviews with city and tribal government officials. | GAO‑25‑107076 |

Some stakeholders cited significant impacts to communities as a result of NMFS’ long processing times. For example, a fishing industry group in Alaska said that remote communities depend on fisheries for their livelihoods and cannot afford to wait a long time for NMFS to review their requests and disburse funds. The industry group representative added that processors in remote coastal communities create infrastructure to support their business operations, which in turn, benefits the broader community. For example, the processor will provide housing for the employees who live on-site, open a grocery store so its employees can purchase food, and bring in fuel for its operations and for employees to purchase. Community members are also able to shop at the grocery store and purchase fuel. If a fishery resource disaster occurs and the processor shuts down, the community will lose access to these services.

Regarding communication, officials we interviewed from nine state and three tribal fish and wildlife agencies said that communication from NMFS is inadequate. Specifically, the officials said their agencies often do not know the status of their requests for disaster assistance as they move through the review process. This can make it difficult for them to respond to fishers, processors, or communities that call asking for updates. For example, an official from Florida told us that it is impossible to determine the status of a disaster request. Additionally, officials from four states and one Tribe said that they would like a tracking mechanism to be maintained on NMFS’ website for each disaster request and for NMFS to update the status regularly.

|

Some Factors That May Make It Difficult for Tribes to Request Fishery Resource Disaster Assistance Staff capacity of Tribes. An official with an intertribal fish commission in Alaska that represents small Tribes said that many Tribes face workforce capacity issues when attempting to access federal funding. The official said Tribes may not have enough staff to request a disaster determination and monitor the progress of the disaster request through the process. Reimbursement payments. One tribal official said that the funding for the fishery resource disaster program is also largely reimbursement-based, which is difficult for the Tribe. Specifically, Tribes must initially have cash on hand to pay for research projects, and NMFS will reimburse them for these expenses, according to the official. Source: GAO analysis of interviews with tribal officials. | GAO‑25‑107076 |

According to stakeholders, NMFS has not communicated key updates about the review process to all potential requesters. For example, officials we interviewed from four Tribes that have requested fishery resource disaster assistance were not aware of FRDIA or the changes it made to the review process. Officials we interviewed from one intertribal commission were not aware that FRDIA includes language about impacts to subsistence fishing. Additionally, while NMFS held workshops about FRDIA for states and Tribes in the West Coast region and the state of Alaska, NMFS has yet to conduct outreach to Tribes in Alaska.[47] NMFS headquarters officials said that they plan to engage with Tribes in Alaska in 2025, but the details are still being determined.

Not Enough Time Has Passed Since FRDIA’s Enactment to Assess the Full Effects on Processing Times

NMFS has started to take some actions in response to FRDIA that may address stakeholders’ concerns about long processing times, but too little time has elapsed since NMFS’ actions to assess the full effects of FRDIA’s amendments. According to NMFS officials, the main approach to speeding up the review process is through implementing FRDIA and following the statutory timelines established for the fishery resource disaster process.

No disaster requests had gone through the entire process to disburse funds to the requester since FRDIA’s addition of timelines, as of August 2024. However, there is some early indication that the time it takes to make determinations is decreasing. Based on our analysis, the median time between NMFS receiving a request and making a disaster determination for the 10 requests submitted in 2022 was 0.8 years (282 days). Following FRDIA’s enactment in December 2022, the median time between NMFS receiving a request and making a determination for the 13 requests made in 2023 was 0.6 years (206 days). The time frame dropped further to 0.4 years (140 days) for the seven requests submitted from January through June 2024. Under FRDIA, the Secretary is to make a disaster determination not later than 120 days after receiving a complete request.[48] NMFS headquarters officials said they have set an internal goal of 60 days for NMFS to complete its review, leaving 60 days for the Secretary to make a determination.[49]

NMFS Has Taken Some Actions to Address Other Challenges, but Issues Remain with Information Access, Guidance, and Assessing Staffing Needs

NMFS has taken some actions to address other challenges, which relate to information access, guidance, and assessing staffing needs. However, issues remain in these areas. Specifically, not all agency officials who work on the program have access to up-to-date information on requests, program guidance does not have complete details, and the agency has not assessed staffing needs despite higher workloads for the fishery resource disaster program post-FRDIA.

NMFS Recently Developed a Tracking System, but Not All NMFS Officials Have Access to It

NMFS officials told us headquarters staff input and track data on fishery resource disaster requests using the agency’s internal tracking system, the disaster grants dashboard. NMFS implemented this system in November 2023, and NMFS headquarters officials said they meet on a weekly basis to discuss any pending and ongoing requests. When a request stalls at any step of the review process, staff elevate the issue to help move it to the next step, according to NMFS headquarters officials.

As of December 2024, only staff responsible for inputting data into the dashboard have full access, while NMFS regional staff can view the data. Other agency staff who work on the program do not have any access, and NMFS’ website does not automatically reflect updates made in the dashboard. NMFS headquarters officials could not explain why other agency staff who work on the program were not given access to the dashboard.

Without access to the tracking system, which now contains the most updated information about requests, NMFS regional officials may not be adequately equipped to respond to requests for status updates. For example, officials from all four NMFS regions with ongoing requests said they use NMFS’ public website as a source to respond to requests for updates. An official from one region said the regional office is the face of the program, but it does not have any more information about the status of disaster requests than what appears on NMFS’ public website. While NMFS officials told us that they plan to start a project in spring 2025 to have NMFS’ website reflect updated information from the dashboard automatically, they are still determining the details of this plan.

GAO’s Key Practices for Evidence-Based Policymaking states that federal agencies should communicate relevant information internally and externally and tailor information to meet stakeholders’ needs.[50] Providing access to its dashboard to NMFS staff working on the program and using this system to update its website would help NMFS staff to provide current information to requesters and help inform the communities affected by a fishery resource disaster about the status of requests.

NMFS Has Updated Public Information but Does Not Provide Complete Details

As part of its implementation of FRDIA, according to NMFS officials, the agency hosted three workshops in different regions during the spring and summer of 2024 to provide information to states and Tribes about FRDIA’s implementation. NMFS also updated the information on its website by adding a “frequently asked questions” page about the program that, among other things, describes changes made by in spring 2025 FRDIA. In addition, in the acknowledgment letters that NMFS sends to requesters after receiving requests, the agency now includes a list of the additional information needed if the original request is considered incomplete.[51]

However, stakeholders cited areas where NMFS could provide additional guidance on the fishery resource disaster review process. For example, officials from six states and one Tribe said that they would like clearer information about what to include in a spend plan, and what NMFS looks for during its review of spend plans. A tribal official in Washington said it is not clear what information is needed in a spend plan, which leads to them getting comments back from NMFS or OMB requesting additional information that causes further delays in the review process. Information to be included in spend plans is described in FRDIA, as well as in Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) letters sent to requesters. There is, however, limited information on NMFS’ website about what should be included in a spend plan and what NMFS looks for during its review of spend plans. Another area where state officials would like more guidance is what to include in their requests for disaster assistance. For example, officials from one state said that NMFS should provide a template for what to include in a request, including the required data.

NMFS headquarters officials said the agency has been waiting on final approval from OMB to publish updated program guidance on FRDIA implementation since the summer of 2023.[52] As of December 2024, while waiting for final approval from OMB, NMFS officials said the agency was re-evaluating the need to update its guidance given that OMB’s review remains pending, the detail in FRDIA, and the updated information on NMFS’ website on FRDIA.

GAO’s Key Practices for Evidence-Based Policymaking states that federal agencies should communicate relevant information internally and externally and tailor information to meet stakeholders’ needs.[53] By providing more detailed information on its website to requesters about what to include in fishery resource disaster assistance requests and spend plans, NMFS will better inform requesters about what information they need to provide. This could lead to the submission of more complete requests and spend plans, which could also help reduce the amount of time it takes NMFS to conduct reviews of both submissions, in turn reducing the amount of time it takes requesters to receive assistance.

NMFS Has a Higher Program Workload but Has Not Assessed Staffing Levels

NMFS received at least nine new requests for fishery resource disaster assistance per year from 2016 to 2023. NMFS officials said that there is uncertainty in the number of annual requests the program may receive, which creates workload planning challenges. NMFS’ workload has also increased due to implementation of the timelines required under FRDIA, according to NMFS officials.

To help address this increased workload, the agency has redirected staff from other programs to work on the fishery resource disaster program, but program staffing levels have not increased overall, according to a senior NMFS official. It is uncertain whether these staffing changes have fully addressed the challenges related to NMFS’ increased workload. As of December 2024, NMFS did not have any full-time headquarters staff that work exclusively on the fishery resource disaster program because staff generally work on multiple programs, according to this senior NMFS official. Based on our conversations with regional officials, only the West Coast region has a full-time staff member working on the program.

NMFS’ Office of Sustainable Fisheries current strategic plan includes an objective focused on providing fishery resource disaster assistance in a timelier way. This document, however, does not mention assessing current staffing levels. In a separate effort, as of December 2024, the Office of Sustainable Fisheries is undergoing a comprehensive review of the current state of its headquarters workforce and developing a 2025–2030 staffing plan, as part of a regular update to the office’s staffing plan. According to NMFS officials however, this review is focused on headquarters staff and will not cover all staff that work on the fishery resource disaster assistance program, such as regional staff.

The Office of Personnel Management (OPM) Human Capital Framework directs agencies to plan for and manage their current and future workforce needs.[54] OPM has reported that one outcome of such actions is a workforce that is positioned to address and accomplish evolving priorities and objectives based on anticipated and unanticipated events. In addition, our principles for effective strategic workforce planning state that agencies should determine the critical skills and competencies needed to achieve their missions and goals.[55] Without assessing its workforce in light of the recent workload changes that have occurred with implementing FRDIA’s timelines, NMFS will not be able to ensure that it has the appropriate staffing levels in place to implement the program.

Stakeholders Highlighted Federal Programs the Fishery Disaster Program Could Learn from, Which Have Varying Design Features and Face Challenges

Some stakeholders told us that the fishery resource disaster program could learn from other disaster-related assistance programs. We reviewed our published reports for federal programs that provide assistance to communities affected by disasters. We selected four disaster-related assistance programs, (1) FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), (2) HUD’s Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR),[56] (3) SBA’s disaster loan program, and (4) USDA’s crop insurance program.[57] According to our past reports, these programs have varying design features, such as the type of assistance they provide, eligibility requirements, and how funding may be used. We found these design features may vary when compared to the fishery resource disaster program. Our past reports have found the selected programs all faced various challenges related to design or implementation, and we have previously recommended ways to help address these challenges.

Selected Federal Programs’ Design Features Affect How They Provide Assistance to Beneficiaries

When considering ways to help improve the fishery resource disaster program, some stakeholders we spoke with pointed to other federal disaster-related assistance programs as examples from which to learn. For example, officials from five state agencies, representatives from an intertribal organization, two of three interstate marine fisheries commissions, and five fishing industry groups, among others, highlighted positive attributes of FEMA and USDA programs, including crop insurance.[58] Interviews with a nonprofit organization, a state agency, and two interstate marine fisheries commissions specifically highlighted crop insurance.

According to our previous reports and agencies’ publicly available information, the following programs have different design features, such as eligible uses of assistance and sources of program funding. Design features affect how programs provide assistance to people or businesses after a disaster, known as beneficiaries:

· NFIP is a federal flood insurance program, meaning the federal government assumes liability for insurance coverage and sets rates for beneficiaries.[59] Residential property owners, renters, and businesses in participating communities can purchase federally backed flood insurance from NFIP through a private insurance company or directly from FEMA through NFIP Direct.[60] When a flood-related loss occurs, a beneficiary files a claim through their insurance provider. The insurance provider adjusts the claim and pays the beneficiary based on the policy coverages and deductibles at the time of the loss.[61] According to FEMA’s website, it can take four to eight weeks to finalize a standard claim and pay a beneficiary.[62] As of December 2022, about a third of beneficiaries paid a full-risk premium for NFIP, meaning that about two-thirds of policyholders had part of their insurance premiums subsidized by NFIP.[63] Unlike the fishery resource disaster program, funds paid from NFIP claims cannot be used to replace lost revenue; they can only be used to replace structures and certain personal property (if included in the policy) damaged by floods.

|

Grants and Fishery Resource Disasters Federal grants can be funded in a variety of ways. For example, fishery resource disaster assistance and Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recover (CDBG-DR) are typically funded through congressional appropriations on an ad hoc, or unplanned, basis. Other federal disaster-related assistance programs have reserve funds that can receive annual or supplemental appropriations. For example, the Department of Health and Human Services has the Infectious Diseases Rapid Response Reserve Fund, which allows agencies to rapidly respond to infectious disease threats through activities such as diagnostic testing. To establish a reserve fund, such as for the fishery resource disaster program, Congress would need to include a reserve fund in a budget resolution that was adopted by both the House of Representatives and Senate, according to a Congressional Research Service report. Source: GAO analysis of previous GAO and Congressional Research Service reports. | GAO‑25‑107076 |

· CDBG-DR provides grants to state, tribal, or local governments (grantees) to address needs not met by other disaster-related assistance programs, principally for low- and moderate-income persons. For funding to become available, the President must declare a disaster, and Congress must appropriate funds.[64] HUD then publishes a notice in the Federal Register to allocate the funds to grantees and outline grant processes and requirements. Unlike the fishery resource disaster program, CDBG-DR lacks permanent statutory authority. However, similar to the fishery resource disaster program, Congress appropriates funding for each disaster for CDBG-DR. Specifically, when disasters occur, Congress has often appropriated funding for the program through supplemental appropriations, with the amount of funding and the requirements for the grantees’ use of the funds typically varying by disaster. Another similarity with the fishery resource disaster program is the time for CDBG-DR funds to reach grantees can be lengthy. For example, we reported that following the wildfires in California in late summer 2018, it took 2 months for a CDBG-DR supplemental appropriation to be enacted and another 16 months for HUD to allocate the funding to jurisdictions in the state.[65] Additional time was needed for grantees to disburse funds to beneficiaries.

|

Loans and Fishery Resource Disasters Loans requiring repayment can present a challenge to those experiencing a disaster and may be sensitive to accruing more debt. For example, some fishing industry groups shared that fishers were already in debt from paying for boats, fishing equipment, permits, or other overhead expenses. When asked about applying for a Small Business Administration (SBA) disaster loan after a fishery resource disaster, some fishing groups shared concerns about taking on additional debt or shared a preference for grant payments. Other stakeholders said they may be interested in a loan option. Further, not everyone who experiences a disaster may qualify for a loan. For example, following the 2017 hurricanes, SBA denied approximately 146,000 requests for disaster loans, representing about 51 percent of applicants, according to our previous reports. The primary reasons applicants were denied were a lack of repayment ability and an unsatisfactory credit history. Moreover, some communities may not be aware of the loans they qualify for. For example, several fishers from fishing industry groups told us they were not aware they could qualify for SBA disaster loans if they needed assistance as a result of a fishery resource disaster. The National Marine Fisheries Service, however, informs fishers that have experienced a fishery resource disaster they may be eligible for assistance through SBA on their website, determination letters, and press releases. Source: GAO analysis of interviews with fishing industry stakeholders and previous GAO reports. | GAO‑25‑107076 |

· SBA’s disaster loan program offers low-interest physical disaster loans to help businesses, nonprofits, homeowners, and renters repair or replace property damaged or destroyed in a federally declared disaster. Small businesses and nonprofits are also eligible for economic injury disaster loans, which may cover operating expenses the business could have paid had the disaster not occurred. For disaster loans to become available, the President or the SBA Administrator must declare a disaster.[66] After a disaster is declared, individuals may apply for disaster loans subject to available funds.[67] SBA then reviews the applications to determine if applicants meet certain criteria. Unlike the fishery resource disaster program, this program uses loans to distribute assistance that require repayment. According to our past work, for the 2017 hurricane disasters, SBA took about 70 days on average from loan application acceptance to provide initial loan disbursement.[68]

|

Insurance and Fishery Resource Disasters According to a 2021 Casualty Actuarial Society Research Brief, insurable criteria included the event occur randomly, affect few policyholders simultaneously, and not be financially excessive for the insurance market, among other requirements. Because fishery resource disasters affect multiple fishers for the same event and can have large financial impacts, insurers may have difficulty offering coverage for fishery resource disasters based on these criteria. However, a fishing industry group we spoke to said they would be interested in purchasing fishery insurance if it existed and was affordable. One stakeholder with whom we spoke is researching the possibility of using fishery insurance to provide payments to fishers once specific conditions are met, such as a sea surface temperature change or a drop in revenue for a fishery. Stakeholders who examined the possibility of fishery insurance, however, expressed concerns about offering insurance that covered lost income from a fishery disaster because of the potential for bad incentives, such as fraud. Source: GAO analysis of interviews with insurance stakeholders. | GAO‑25‑107076 |

· Crop insurance helps mitigate the risks of farming from natural disasters and revenue loss by allowing farmers to purchase federally subsidized insurance policies.[69] Farmers can insure against production losses due to natural disasters, such as drought or flooding, or financial losses from commodity price declines. USDA partners with private insurance companies to sell and service insurance policies. When a covered event occurs, a beneficiary files a claim within 72 hours of the beneficiary’s initial discovery of damage or loss of production with the insurance company that handles the claim adjustment and payment process.[70] The insurance company determines if the claim is valid. If the claim is determined to be valid, payments are then made to beneficiaries through the insurance companies. According to at least two crop insurance companies, farmers typically receive payments within 30 days of the claim being finalized.[71]

The federal government subsidizes farmers’ premiums and the insurance companies’ administrative and operating expenses. According to USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA), in 2023 the program cost the federal government $14.6 billion, of which they paid $9.7 billion (66 percent) to farmers and $4.9 billion (34 percent) to insurance companies.[72] Similar to the fishery resource disaster program, crop insurance can help compensate farmers for lost revenue.

For examples of the design features of our selected disaster programs alongside the fishery resource disaster program, see table 1.

Table 1: Examples of Design Features of the Fishery Resource Disaster Program and Selected Federal Programs That Provide Disaster-Related Assistance

|

Program |

Type of disaster-related assistance provided |

Highlights of process to obtain assistance |

Examples of eligible uses of assistance |

Source of program funding |

|

Fishery resource disaster program |

Granta |

Tribe, state, or territory requests disaster assistance. The Secretary of Commerce determines whether a disaster occurred. If so, Congress can appropriate funding for the disaster. Funding is then disbursed to the requester. |

Partially compensate for lost revenue. |

Ad hoc congressional appropriations.b |

|

National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) |

Insurance |

The beneficiary files a claim, and an insurance assessment is completed. If the claim is valid, the beneficiary receives payment based on their policy coverages and deductibles.c |

Replace or repair structures. Replace damaged personal property. |

Insurance premiums paid by beneficiaries and the federal government. Federal borrowing from the U.S. Department of the Treasury when premium revenue from beneficiaries is insufficient to pay for claims. |

|

Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) |

Granta |

President declares a disaster and Congress appropriates funding. The Department of Housing and Urban Development allocates funding to tribal, state or local governments (grantees). Grantees can generally use subrecipients to issue awards to beneficiaries. |

Funding is intended to go to communities with the most unmet need. |

Ad hoc congressional appropriations. |

|

Small Business Administration (SBA) disaster loan program |

Loan |

President or SBA Administrator declares a disaster, and individuals, nonprofits, and businesses submit loan applications for review by SBA. If approved, loans are issued. |

Replace or repair property. Help cover business operating expenses. |

Principal and interest payments. Annual congressional appropriations. Ad hoc congressional appropriations.d |

|

Crop insurance program |

Insurance |

The beneficiary files a claim, and an insurance assessment is completed. If the claim is valid, the beneficiary receives a payment.c |

Partially compensate for lost revenue. |

Insurance premiums paid by policyholders and the federal government. Congressional appropriations.e |

Source: GAO summary of the fishery disaster assistance program and previously published GAO reports and publicly available information on selected programs. | GAO‑25‑107076.

Although CDBG-DR is not a permanently authorized program, for the purposes of this report, we refer to it as a program. All of these programs can be used by businesses.

aThe program may provide assistance through mechanisms other than grants, such as loans, to beneficiaries.

bThe timing of ad hoc congressional appropriations varies.

cThose who purchase insurance policies are policyholders. For the purposes of this report, we will refer to them as “beneficiaries.”

dThe SBA disaster loan program can run out of money and may require additional appropriations. For example, according to SBA’s website, the program ran out of funds in October 2024 after increased demands following Hurricane Helene.

eFunding for crop insurance is permanently authorized by the Federal Crop Insurance Act (FCIA) of 1980, as amended, and funded with congressional appropriations authorized for “mandatory expenses” specified by statute. 7 U.S.C. 1516(a)(2).

We Have Highlighted Challenges and Recommended Ways to Improve Selected Disaster-Related Assistance Programs

We have identified challenges associated with the four selected programs from relevant reports. We have previously made recommendations for executive action and identified matters for congressional consideration to help improve their operations. For example:

· FEMA NFIP. NFIP, which has been on GAO’s High-Risk List since 2006, faces significant challenges due to its competing goals: keeping flood insurance affordable and keeping the program fiscally solvent.[73] Across previous relevant reports, we made three recommendations to FEMA to incorporate actuarially sound practices into the program.[74] In addition, in 2008, we recommended that NFIP premiums fully reflect the actuarially expected losses for the program.[75] In 2021, FEMA implemented our recommendation and established a new ratemaking methodology, which brought NFIP closer to actuarial soundness. Across previous relevant reports, we have also recommended that Congress consider three matters related to NFIP’s solvency and affordability. For example, in 2023, we recommended that Congress consider addressing NFIP’s legacy and potential future debt and to consider the best means for doing so, such as providing funding to make up for the statutorily generated premium shortfall.[76] This matter had not been addressed as of January 2025.

· HUD CDBG-DR. Across previous relevant reports, we made four recommendations related to assessing grantee materials, state and local reported challenges, and fraud risk. For example, in 2021, we recommended that HUD comprehensively assess CDBG-DR for fraud risks because its decentralized structure makes it vulnerable to fraud.[77] This recommendation was partially addressed as of February 2024 when HUD completed an assessment that included questions related to fraud. We also recommended that Congress consider two matters related to disaster recovery across previous relevant reports, including to consider establishing permanent statutory authority for a disaster assistance program that responds to unmet needs in a timely manner.[78] Having permanent statutory authority could help address challenges with CDBG-DR, such as customized grant requirements and delayed funding disbursement for each disaster. This matter had not been addressed as of January 2025.

· SBA disaster loans. Across previous relevant reports, we made four recommendations to SBA related to its outreach efforts. For example, in 2020, we found that SBA did not have metrics for how well its outreach efforts informed potential beneficiaries about the program, and we recommended that SBA establish such metrics.[79] SBA implemented this recommendation in 2020 by incorporating metrics into its 2020 annual customer satisfaction survey.

· USDA crop insurance. Across previous relevant reports, we made three recommendations to help address our long-standing concerns regarding the cost of the program. For example, in 2015, we recommended that USDA, as appropriate, increase premium rates in areas with higher crop production risks by as much as the full 20 percent annually allowed by law.[80] We made this recommendation because USDA did not raise these premium rates to the extent the law allows to make the rates more actuarially sound for the higher risk premium rates. This recommendation had not been addressed as of January 2025.

|

Saving for Disasters The rising number, frequency, and impact of disasters in the U.S. due to changes in the climate combined with a greater reliance on federal assistance has increased the federal government’s fiscal exposure. However, our past work found the federal budget does not generally account for disaster assistance provided by Congress or the long-term impacts of climate change on existing federal programs. The costs of recent disasters have illustrated the need for planning for climate change risks and investing in resilience. We have previously found that most of the selected federal disaster-related programs could reduce their fiscal exposure. Source: GAO analysis of previous GAO reports. | GAO‑25‑107076 |

We also recommended that Congress consider three matters related to reducing the high cost of crop insurance program for the federal government across our previous relevant reports. For example, in 2014, we recommended that Congress consider reducing the level of federal premium subsidies for revenue crop insurance policies to reduce program costs.[81] This matter had not been addressed as of January 2025. According to RMA,[82] the program cost the federal government $14.6 billion in crop year 2023.[83] Crop insurance is projected to cost the federal government an average of $12.4 billion per year from 2024 to 2034, according to the Congressional Budget Office.[84]

Conclusions

Commercial and recreational marine fisheries are critical to the nation’s economy, provide numerous jobs, and can serve as a lifeline for surrounding communities, particularly those in remote locations. Fishery resource disasters can affect large areas and result in large negative economic impacts for affected communities. There have been long-standing concerns among stakeholders about the time it takes to request and receive assistance from the fishery resource disaster program. In addition, Congress passed two laws to make changes to the program recently. NMFS has taken actions to implement FRDIA, which amended the Magnuson-Stevens Act in 2022 to, among other things, add required time frames for processing disaster requests, and initial data indicate that NMFS’ implementation of the act’s statutory timelines may be resulting in faster determinations of whether a disaster occurred.

NMFS has taken some actions to address challenges to accessing information, but challenges continue to exist regarding access to status updates as requests go through the fishery resource disaster process. Specifically, not all agency staff who work on the program have access to the internal system to track requests, and the NMFS’ website does not automatically reflect updates made in the agency’s internal system. NMFS officials said the agency plans to automate this process in 2025, but the details of this plan are still being determined. Improving information access for NMFS staff would enable them to provide current information to requesters and help inform the communities affected by a fishery resource disaster about the status of requests.

As part of implementing FRDIA and sharing information on the changes it made to the fishery resource disaster process, NMFS has hosted workshops and updated its website. However, stakeholders cited areas where NMFS could provide more complete information on the process. For example, NMFS provides information about what to include in a spend plan in correspondence with requesters, but the agency provides limited information on its website about these requirements or what it looks for during its reviews of requests. In addition, the agency is waiting on final approval to issue formal guidance on FRDIA and is re-evaluating whether it will do so. In the meantime, providing more detailed information on its website will allow NMFS to inform requesters to help them better understand the information they need to provide—potentially reducing the amount of time it takes for requesters to receive assistance.

NMFS faces higher workloads due to implementing the required processing timelines under FRDIA. While the agency has redirected staff from other programs to work on the fishery resource disaster program, it has not assessed staffing levels for the program. NMFS is currently undergoing a comprehensive review of its workforce and developing a staffing plan, but this effort is not focused on the fishery resource disaster assistance program. Assessing staffing levels for the program in light of the programmatic changes that have occurred in recent years will allow NMFS to ensure that it has the appropriate staff and workforce structure in place. This would also allow the agency to provide timely assistance to businesses and communities affected by fishery resource disasters.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to NMFS:

The Assistant Administrator for NMFS should provide access to the tracking system to staff working on the fishery resource disaster program and use information from this system to update the program website. (Recommendation 1)

The Assistant Administrator for NMFS should provide more detailed information on NMFS’ website about the fishery resource disaster process to clarify the requirements for documents submitted by requesters, such as requests for fishery resource disaster assistance and spend plans. (Recommendation 2)

The Assistant Administrator for NMFS should assess whether staffing capacity is sufficient to administer the fishery resource disaster program. (Recommendation 3)

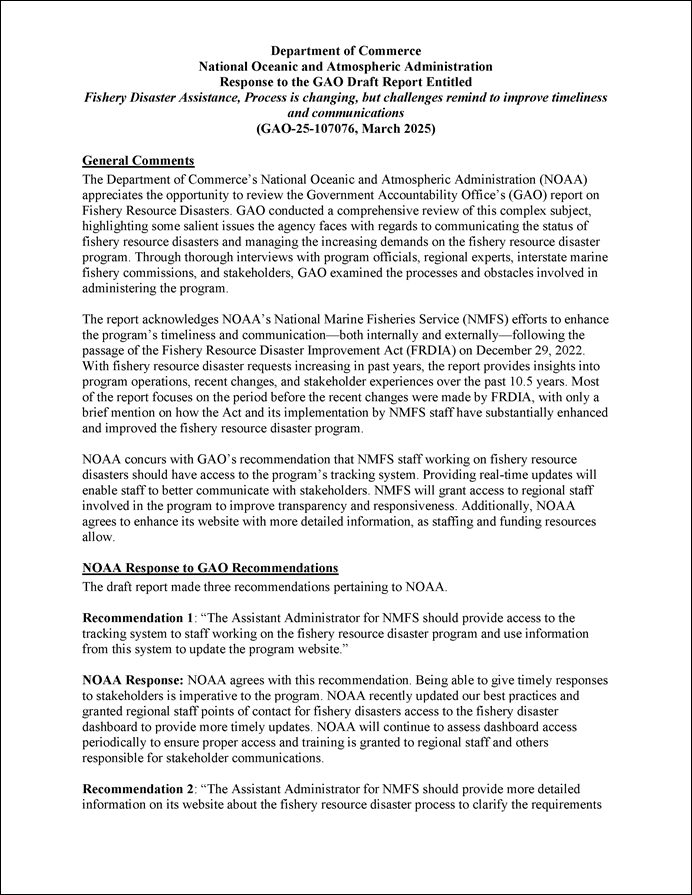

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Commerce for review and comment. NOAA, on behalf of Commerce, provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix IV, and which we summarize below. NOAA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

In their written comments, NOAA agreed with our recommendations and described actions they plan to take to address them. These actions include granting access to the tracking system to regional staff involved in the fisheries resource disaster program to improve transparency and responsiveness. Additionally, NOAA agreed to enhance its website with more detailed information and stated that it is working to ensure that up-to-date information is readily available on its public website, as resources allow. NOAA stated that it will evaluate whether the staffing capacity across the agency is sufficient to administer the fishery resource disaster program as resources allow noting that the agency is operating under a hiring freeze and is preparing for a likely reduction in force across the agency.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Commerce, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at JohnsonCD1@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff members who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Sincerely,

Cardell D. Johnson

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

This report (1) describes the fishery resource disaster process, including recent changes; (2) describes the number of fishery resource disaster requests submitted from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2024, amount of funding disbursed, and time needed to disburse the funding; (3) examines stakeholder-reported challenges related to the fishery resource disaster program and what the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) has done to address them; and (4) describes our past work on selected federal disaster-related assistance programs.

For our first objective, we reviewed relevant federal laws, including the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (Magnuson-Stevens Act). We also reviewed the Fishery Resource Disasters Improvement Act (FRDIA) and Fishery Improvement to Streamline untimely regulatory Hurdles post Emergency Situation (FISHES) Act, both of which amended the Magnuson-Stevens Act.[85]

We identified information related to the fishery resource disaster program such as statutory review timelines, disaster assistance eligibility requirements, acceptable uses of disaster funds, and information required to be included in a complete spend plan. We also reviewed relevant agency documents and information, including NMFS’ November 2023 standard operating procedures for the fishery resource disaster program, and information on NMFS’ website as of March 2025. In addition, we interviewed officials responsible for administering the program, including officials at NMFS headquarters, all five NMFS regional offices, and all three of the interstate marine fisheries commissions.

For our second objective, we analyzed NMFS’ data on fishery resource disaster assistance requests received from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2024, the most recent 10.5-year period at the time of our analysis. These data included information such as who requested the disaster assistance, the fishery affected, date of request, date of disaster determination, and date and amount of funding that was disbursed to the requester.

NMFS started using a new system—the disaster grants dashboard—to track its fishery resource disaster assistance process in November 2023. Prior to the dashboard’s introduction, NMFS used a legacy data system and did not track all phases of the process.[86] To assess the reliability of the data, we reviewed relevant documentation such as the data entry instruction manual and spoke with NMFS officials within the Office of Sustainable Fisheries and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

NOAA’s Grants Management Division is responsible for updating the data and the website on disaster requests. We conducted logic and electronic testing on the data to identify obvious errors. To populate the dashboard, NMFS officials said that they entered information about previously requested fishery resource disasters into the disaster grants dashboard prior to its introduction in November 2023. NMFS officials said they were very confident in the accuracy of the data for requests for fishery resource disaster assistance received in 2018 or later, which includes the majority (80) of the 111 requests received from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2024. As such, we restricted our analysis about the timeliness of fund disbursal to requesters to the 56 requests that were approved since 2018.

To assess the accuracy of the data for the 31 requests for fishery resource disasters that were received before 2018, we compared the information available on NMFS’ public website to the information about those requests in the dashboard. We did not find any obvious discrepancies. We determined the data for the 10.5-year period in our scope were reliable for our purposes to describe the number of fishery resource disasters and their characteristics.

We also reviewed a non-generalizable sample of funding awards for 14 fishery resource disaster assistance requests for a more in-depth review of how disaster funding was used. We selected one request for assistance for each of our selected 10 states and four Tribes. Six of our selected states (Louisiana, Maine, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, and South Carolina) and two of our selected Tribes (Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe and Squaxin Island Tribe) each had one disaster request for which funding was disbursed. The remaining four states (Alaska, California, Florida, and Washington) and two Tribes (Quileute Tribe and Yurok Tribe) had multiple disaster requests for which funding was disbursed. For those requesters, we selected the most recently completed request for fishery resource disaster that reached the end of its financial award. For each of the 14 awards, we reviewed NMFS data about funding amounts; documents such as spend plans, budget narratives and status reports to NMFS about grant activities; and requested information from requesters about direct payments to final recipients.

For our third objective—to identify what NMFS has done to address challenges identified by stakeholders—we reviewed documents, such as information that NMFS provides to requesters. We also interviewed officials responsible for administering the program, including officials at NMFS headquarters, all five NMFS regional offices, and all three of the interstate marine fisheries commissions.

We also identified a non-generalizable sample and conducted semi-structured interviews with representatives from 10 states and four Tribes that had requested assistance. To select state officials to interview, we considered the NMFS regions that received requests for fishery resource disaster assistance from January 1, 2014 to June 30, 2024. Four of the five NMFS regions had ongoing requests during that time.[87] Within each of those regions, we selected three states in total: the two states that had the largest number of requests for fishery resource disaster assistance, and one state that had the smallest number of requests for disaster assistance. [88] To select our four Tribes, we reached out to the Tribes that had submitted the largest number of requests for fishery resource disaster assistance.[89]

We identified common themes from our discussions with stakeholders about challenges they experienced and changes they would suggest making to fishery resource disaster assistance. We interviewed an additional Tribe to provide greater balance to describe the experiences of Tribes in remote Alaska.[90] We also met with representatives from two intertribal organizations and officials from three local governments that received fishery resource disaster assistance.[91] Finally, we interviewed representatives from 11 selected fishing industry organizations representing affected fisheries in the Alaska and Southeastern NMFS regions. We reached out to fishing industry groups in the other two regions that had requests but did not receive a response.[92]

We conducted site visits to Alaska and Louisiana to meet with state fish and wildlife agency officials, local government officials, and fishing industry representatives from fisheries that received fishery resource disaster assistance. We conducted site visits to these states based on the number of requests made and amount of funding received from the fishery resource disaster program, their geographic diversity, and the size of their respective fishing industries.