RUSSIA SANCTIONS AND EXPORT CONTROLS

U.S. Agencies Should Establish Targets to Better Assess Effectiveness

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees

For more information, contact: Nagla'a El-Hodiri at elhodirin@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

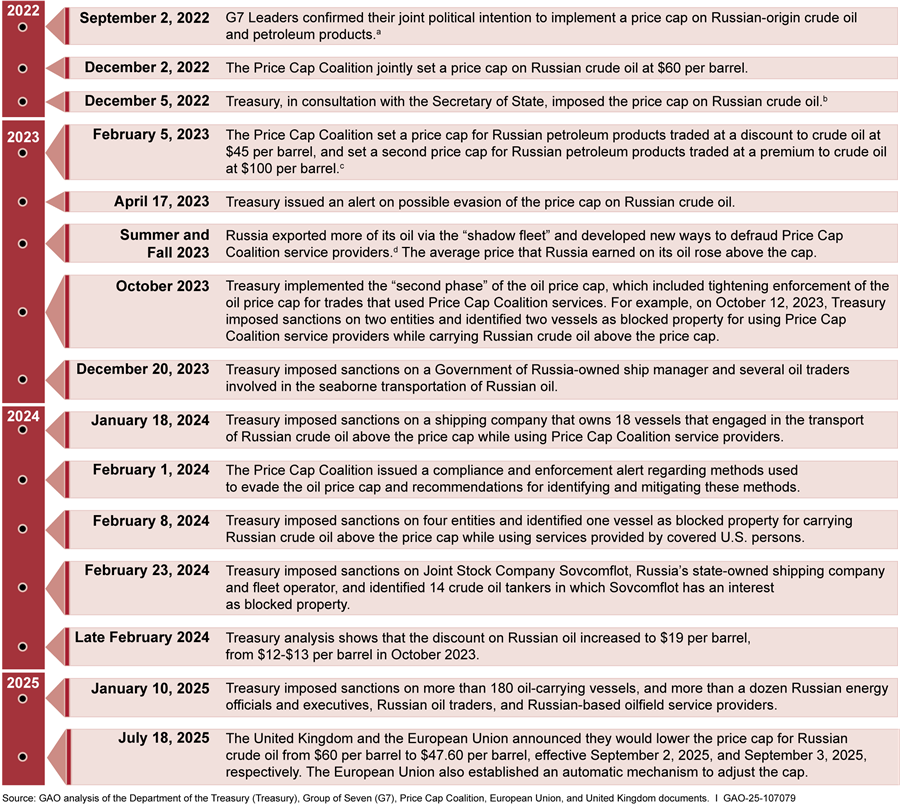

GAO independently identified three broad categories for the objectives of U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia (see figure). U.S. agencies have made progress toward these objectives, but Russia has circumvented some U.S. sanctions and export controls. Specifically, GAO found that Russia’s economic growth was about 6 percentage points lower in 2022 than what might have happened absent the events in 2022, including the invasion of Ukraine and sanctions. However, GAO’s analysis did not find that economic growth was statistically different than expected in 2023 and 2024. A price cap on Russian oil likely kept Russian oil production and exports relatively stable but Russian actions, such as the use of a “shadow fleet” to export oil, limited the cap’s efficacy. U.S. agencies assess that export controls have hindered but not completely prevented Russia’s efforts to obtain U.S. military technologies. While U.S. agencies have taken various actions to hold malign Russian actors accountable, including freezing assets, the agencies reported challenges in assessing their effectiveness.

U.S. agencies primarily responsible for implementing sanctions and export controls on Russia have not established clearly defined objectives linked to measurable outcomes with targets for their activities. As a result, agencies cannot fully assess progress toward achieving their objectives, thus limiting the U.S. government’s ability to determine the effectiveness of its broader sanctions and export controls efforts related to Russia. This information is crucial for improving current efforts and informing the future use of sanctions and export controls.

As of September 30, 2024, U.S. agencies had obligated about $164 million in Ukraine supplemental funding for activities related to sanctions and export controls on Russia. These agencies used this funding for staff and investigative tools, among other uses. For example, a Department of State bureau used supplemental funding to increase the size of its workforce dedicated to identifying Russian sanctions targets. GAO found that two State bureaus have not assessed risks to these sanctions activities when their supplemental funding expires on September 30, 2025. As a result, the bureaus cannot develop an effective plan to sustain or restructure these activities, threatening broader goals.

Why GAO Did This Study

The U.S. and its allies responded to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine with wide-ranging sanctions and export controls, including a price cap on Russian oil. U.S. agencies received additional resources under Ukraine supplemental appropriations acts, some of which they used for sanctions and export controls.

Congress included a provision in Public Law 117-328 for GAO to conduct oversight of Ukraine supplemental funding. For U.S. sanctions and export controls related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, this report examines progress toward objectives and the extent to which U.S. agencies have established objectives with measurable outcomes and assessed risks to activities funded by supplemental resources, among other objectives.

GAO analyzed agency documents and data, performed economic analyses, reviewed relevant literature, interviewed agency officials, and selected and interviewed 11 knowledgeable stakeholders, including former government officials and economists. GAO selected these stakeholders based on their expertise related to U.S. sanctions or export controls.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that U.S. agencies define objectives with targets for sanctions and export controls on Russia, assess progress toward these objectives, and that two State offices assess the risks to their programs without future supplemental funding. Commerce and Treasury agreed with the recommendations. State partially agreed.

Abbreviations

|

BIS |

Bureau of Industry and Security |

|

CHPL |

Common High Priority List |

|

Coalition |

Price Cap Coalition |

|

DRL |

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor |

|

EB |

Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs |

|

EU |

European Union |

|

FinCEN |

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network |

|

G7 |

Group of Seven |

|

GDP |

gross domestic product |

|

IMF |

International Monetary Fund |

|

ISN |

Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation |

|

NSC |

National Security Council |

|

OCE |

Office of the Chief Economist |

|

OFAC |

Office of Foreign Assets Control |

|

OPEC |

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries |

|

REPO |

Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs Task Force |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 8, 2025

Congressional committees

On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, eight years after its 2014 invasion and annexation of Crimea. The war is the largest armed conflict in Europe in decades, has led to a tremendous loss of life and a humanitarian crisis, and threatens the sovereignty of a democratic country. The U.S. government imposed economic sanctions and export controls on Russian entities and individuals in response to Russian aggression in Ukraine in both 2014 and in 2022.[1]

The U.S.’s economic sanctions have included denying Russian companies or other entities access to the U.S. financial system and freezing the assets of individuals, such as Russian oligarchs, under U.S. jurisdiction. Export controls have included restricting the transfer of sensitive or dual-use items, such as semiconductors, to Russia. Understanding the objectives and effectiveness of U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia is critical for making informed decisions about the future of U.S. policy in this area.

The U.S. Departments of State, the Treasury, Commerce, Justice, and Energy, along with other U.S. agencies, have roles in reviewing, implementing, or enforcing sanctions or export controls. U.S. agencies received additional resources that they have used to implement and enforce sanctions and export controls related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, including funding provided under four of five Ukraine supplemental appropriations acts.[2]

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, included a provision for us to conduct oversight, including audits and investigations, of amounts appropriated in response to the war in Ukraine.[3] This report is part of a broader series of reviews we are conducting in response to this provision. This report examines (1) the extent to which U.S. agencies have established objectives with measurable outcomes for their sanctions and export controls on Russia; (2) progress made toward addressing categories of U.S. sanctions and export controls objectives on Russia; (3) supplemental resources U.S. agencies have received and how they used them to implement and enforce sanctions and export controls on Russia; and (4) the extent to which U.S. agencies have developed plans for the use of remaining supplemental funds and assessed risks to their sanctions and export controls activities in the absence of future funding.

To address our first objective, we analyzed documents that agency officials told us provided insight into their objectives for sanctions and export controls on Russia, including nearly 300 relevant State, Treasury, and Commerce press releases issued from February 24, 2022, through January 17, 2025, as well as pertinent agency rules and regulations. We reviewed agency documents related to U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia and interviewed or obtained written responses from relevant officials from State, Treasury, Commerce, Justice, and Energy. We assessed agency actions against federal internal control standards for defining objectives.[4]

To address our second objective, we estimated the impact of the events in 2022 and beyond, including the invasion and sanctions, on economic indicators. Specifically, we used a synthetic control methodology—a technique that enables comparison to a counterfactual situation—to estimate how Russia’s economy might have evolved absent events in 2022 and beyond, including the invasion and sanctions. We also reviewed Treasury analyses of International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts of Russia’s economy to analyze the effects of the 2022 war and sanctions on Russia’s gross domestic product (GDP). We examined data on the volume of Russian oil production and oil export revenues to assess the effect on Russia’s economy from a price cap on Russian oil. In addition, we reviewed Commerce and State analyses to assess agencies’ progress on implementing and enforcing U.S. export controls on Russia. We also reviewed relevant documents from Commerce, State, Treasury, and Justice related to holding accountable those who support Russia’s war or abuse human rights. Lastly, we interviewed State and Treasury officials about sanctions related to human rights and discussed visa restrictions with State officials.

To inform our first two objectives, we selected and interviewed 11 nongovernmental stakeholders based on their knowledge of U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia.[5] We also conducted a literature review on sanctions and export controls related to Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. We reviewed numerous studies and identified 87 relevant studies for more in-depth review.[6] We developed a data collection instrument to systematically review these studies to obtain information on sanctions and export controls’ objectives and economic outcomes.

To address our third and fourth objectives, we analyzed Treasury, State, Justice, and Commerce obligations, staffing data, and relevant documentation.[7] We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for our purposes of reporting on the amounts obligated and agencies’ use of their Ukraine supplemental funding. We also interviewed and obtained written responses from Treasury, State, Justice, and Commerce officials. Lastly, we reviewed agency plans and asked for any risk assessments of agencies’ activities supported by Ukraine supplemental funding to determine whether agencies had documentation that met federal internal control standards for identifying, analyzing, and responding to risks.[8] See appendix I for more details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2023 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

U.S. Sanctions and Export Controls on Russia

The U.S. has imposed substantial economic sanctions and export controls on entities and individuals as a key element of its foreign policy response to Russian aggression in Ukraine. According to State officials, as of January 2025, nearly 3 years after the start of the war in Ukraine, State and Treasury had designated over 6,000 entities and individuals under Russia-related sanctions authorities. According to Commerce, it had placed over 900 foreign entities that supported Russia’s military on its list of individuals, companies, and organizations subject to export control restrictions by the end of 2024. Sanctions and export controls on Russia are significant due to the large size of Russia’s economy compared to other countries with much smaller economies where the U.S. has imposed comparable types of restrictions.[9]

U.S. sanctions may include actions which limit transactions involving targeted foreign governments, individuals and entities, including blocking property and interests in property subject to U.S. jurisdiction, and limiting access to the U.S. financial system.[10] U.S. sanctions on Russia include those targeting its financial sector, such as sanctions on Russia’s central bank and other financial institutions. U.S. sanctions have also sought to limit Russia’s access to international capital markets and the international financial system, as well as prevent new U.S. investments in Russia.[11] Lastly, U.S. sanctions have targeted Russia’s energy sector and the overseas wealth and economic activity of Russia’s elites.

U.S. export controls on Russia restrict the export and reexport of certain items subject to U.S. export control jurisdiction, such as electronics; computers; telecommunications; sensors and lasers; navigation and avionics; marine, aerospace, and propulsion technologies; and other equipment and materials.[12] The U.S. government also has prohibited the export to Russia of U.S. dollar-denominated bank notes and luxury goods.[13] See table 1 for examples of U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia.

|

Date Announced |

Examples of sanctions and export controls on Russia |

|

February 24-25, 2022 |

· Treasury imposed sanctions on President Putin and Russia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, and on Russia’s two largest banks and almost 90 financial institution subsidiaries around the world. · Commerce imposed a series of export controls that primarily targeted Russia’s defense, aerospace, and maritime sectors, including export controls on over 45 Russian military end users, which were added to Commerce’s Entity List.a |

|

March 11, 2022 |

· State imposed sanctions on Russian elites, including eight board members of a Russian bank and management company. · Treasury imposed sanctions on Russian elites, including 12 members of Russia’s legislature, and family members of President Putin’s spokesperson who have supported Russia’s war. · Commerce imposed export controls on luxury goods to Russia, including high-end automobiles, alcoholic spirits, tobacco, clothing, and jewelry. |

|

September 15, 2022 |

· State imposed sanctions on over 20 key Russia-installed authority figures in Ukraine territories controlled by the Russian military. · Treasury imposed sanctions on two entities and 22 individuals, including those connected to human rights abuses and leaders of key financial institutions. · Commerce expanded export controls against Russia on items potentially useful for Russia’s chemical and biological weapons’ production capabilities, and advanced manufacturing. |

|

February 24, 2023 |

· State imposed sanctions on over 60 individuals and entities complicit in the administration of Russia’s government-wide operations and policies of aggression toward Ukraine. · Treasury imposed sanctions on 22 individuals and 83 entities in the metals and mining sector, including over 30 third-country individuals and companies connected to Russia’s sanctions evasion efforts, and those related to arms trafficking and illicit finance. · Commerce issued four rules imposing additional export restrictions on Russia, Belarus, and Iran—related to Russia’s use of Iranian drones, as well as entities in third countries. |

|

October 30, 2024 |

· State imposed sanctions on more than 80 individuals and entities, targeting entities in multiple third countries, including the People’s Republic of China, India, Malaysia, Thailand, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates, to disrupt sanctions evasion. · Treasury imposed sanctions on more than 270 individuals and entities involved in supplying Russia with advanced technology and equipment that Russia needs to support its war machine. · Commerce added 40 entities to its Entity List in connection with their support for Russia’s war in Ukraine and tightened restrictions on 49 listed entities to address their procurement of high-priority U.S.-branded microelectronics and other items on behalf of Russia.a |

Source: GAO analysis of the Department of State, Department of the Treasury, and Department of Commerce documents. | GAO‑25‑107079

aThe Entity List is a list of foreign individuals, companies, and organizations reasonably believed to be involved, or to pose a significant risk of being or becoming involved, in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the U.S., subjecting them to export licensing requirements. 15 C.F.R. § 744.16. The Entity List is found at Supplement No. 4 to Part 744 of Title 15.

Oil is a key source of revenue for Russia. On December 5, 2022, the U.S. implemented a price cap on Russian crude oil as part of the Group of Seven (G7) with the 27 member states of the European Union (EU) and Australia.[14] These countries are collectively called the Price Cap Coalition (Coalition).[15] The oil price cap permits service providers in Coalition countries to support the Russian oil trade only if the oil is sold at or below a cap of $60 per barrel.[16] According to Treasury, which is the primary agency that administers and enforces U.S. sanctions related to the oil price cap, completely stopping the flow of Russian oil would have serious consequences for the global economy, including denying energy to the emerging world and raising global oil prices. The stated goal of the price cap is to reduce Russia’s oil revenues while maintaining the stability of global energy markets, according to Treasury officials. The oil price cap is designed to force Russia to sell its oil for lower prices than it could otherwise obtain, according to Treasury documents.

U.S. Sanctions and Export Controls Authorities

U.S. sanctions and export controls are imposed pursuant to statute or other authorities. For example, the President may use authorities granted in the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and the National Emergencies Act to issue executive orders authorizing sanctions.[17] Executive Orders 14024 and 14114 are key authorities that have been used to impose sanctions related to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Executive Order 14024 targets individuals who have carried out various harmful foreign activities on behalf of Russia, including undermining democratic processes or institutions in the U.S. or abroad.[18] Executive Order 14114, in relevant part, amends Executive Order 14024 by adding a new section targeting foreign financial institutions that conducted or facilitated any significant transactions for or on behalf of persons sanctioned for operating in the technology, defense and related materiel, construction, aerospace, or manufacturing sectors of the Russian economy, or other such sectors as may be determined to support Russia’s military industrial base. It also targets foreign financial institutions that conducted or facilitated any significant transactions or provided any service, whether directly or indirectly, involving Russia’s military industrial base.[19]

Key legislative acts used to impose sanctions and export controls on Russia include:

· the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, which targets foreign entities or individuals worldwide connected to certain human rights offenses;

· the Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act, which targets Iran, Russia, and North Korea with sanctions related to various activities, such as human rights abuses, development of ballistic missiles, cybersecurity attacks, and corruption; and

·

the Export Control Reform Act of 2018, which requires the

creation of a list of controlled items and that licenses or other

authorizations be required for exports, reexports, and in-country transfers of

those items, among other things.[20]

Roles of Relevant Federal Agencies in Sanctions and Export Controls

State, Treasury, and Commerce are the primary agencies that review, implement, or enforce sanctions or export controls. Other agencies, including Justice and Energy, have specific roles in sanctions implementation and enforcement based on their expertise and broader duties.[21]

The following State offices are among those that have a role in sanctions, export controls, and visa restrictions on Russia:[22]

· The Office of Sanctions Coordination serves as the principal advisor to the Secretary of State on the development and implementation of sanctions policy, including for sanctions on Russia. It also serves as the coordinator for the development of sanctions policy within State. It acts as the lead representative in diplomatic engagements on sanctions matters to obtain international cooperation with U.S. sanctions.

· The Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs’ (EB) Division for Counter Threat Finance and Sanctions develops and implements sanctions to counter threats to national security posed by specific activities, terrorist groups, and countries. EB also advises the Secretary of State on economic sanctions strategies to achieve U.S. foreign policy objectives and works with other agencies to enact such strategies.

· The Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation (ISN) plays a key role in export controls policy to protect dual-use items and to prevent their use in ways that harm U.S. national security or are contrary to U.S. foreign policy objectives.[23] According to ISN officials, ISN is the U.S. government’s lead office for imposing sanctions under the Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act. ISN imposes sanctions on foreign individuals, private entities, and governments that engage in proliferation activities, including Russia. According to ISN officials, ISN focuses on transactions within Russia’s defense sector.

· The Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL) submits nominations for sanctions programs and packages that relate to human rights violations and abuses, as well as efforts to undermine democracy, according to DRL officials. DRL also makes recommendations to the Secretary of State to impose visa restrictions on officials of foreign governments and their immediate family members who have been involved in gross violations of human rights, including violations related to Russia’s war against Ukraine.

· The Office of the Chief Economist (OCE) provides analysis and advice to the Secretary of State and other senior leaders across the department. OCE monitors and explains current economic and financial trends in key countries and regions, including Russia. OCE also analyzes U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia to determine possible sanctions evasion and trade diversion.

· According to State officials, other State offices have roles as well.

· The Bureau of Energy Resources supports the development, coordination, implementation, and monitoring of State’s sanctions against entities involved in the development or expansion of Russia’s energy production and export capacities.

· The Office of the Legal Adviser consults with State bureaus such as EB and ISN on proposed sanctions packages, including those on Russia, to strengthen them against any potential legal challenges.

· The Bureau of Political-Military Affairs’ Directorate of Defense Trade Controls implements an arms embargo on Russia and investigates reports of unauthorized exports of defense articles to Russia.

· The Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs plays a role in developing and implementing sanctions with allies and partners; for Russia, the Bureau has worked on sanctions involving trade, energy, human rights, travel, banking, and nonproliferation, among others.

·

The Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs

provides concurrence on Treasury’s financial sanctions packages related to

transnational organized crime, among others, such as Treasury’s January 2023

designation of the Wagner Group, a Russian private military company. It

also reviews Treasury’s corruption-related financial sanctions packages, such

as those under the Global Magnitsky Act, and makes recommendations to the

Secretary of State to impose visa restrictions on officials of foreign

governments and their immediate family members who have been involved, directly

or indirectly, in significant corruption.

The following Treasury offices have a role in sanctions on Russia:

· The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) participates in all aspects of implementing sanctions, including targeting, outreach to the public, and compliance, according to Treasury officials. OFAC also enforces sanctions by conducting civil investigations of sanctions violators and working with law enforcement agencies. OFAC publishes the Specially Designated Nationals List.[24] Within OFAC, the Sanctions Economic Analysis Division provides economic analyses of U.S. sanctions’ effect on various aspects of Russia’s economy, including its energy sector.

· The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) plays a role in identifying entities and individuals for new sanctions and export controls as well as supporting the enforcement of sanctions and export controls on Russia. According to FinCEN, it analyzes Bank Secrecy Act information to identify trends and patterns related to suspected evasion of Russia-related sanctions and export controls and provides alerts to U.S. financial institutions on such evasion. Its whistleblower incentive program encourages individuals to provide tips related to illegal monetary transactions, money laundering, and other financial crimes.

Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) implements and enforces the Export Administration Regulations, which regulate the export, reexport, and in-country transfer of dual-use, solely commercial and some less sensitive military items.[25] Through its export licensing process, BIS restricts specified countries’ and persons’ access to such items. In response to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, BIS maintains broad export controls on Russia. BIS has also added hundreds of Russian individuals and companies and third-party entities to its Entity List and developed the Common High Priority List to help U.S. industry identify items that are at risk of being diverted to Russia due to their importance to Russia’s war efforts.[26]

In addition, Justice and Energy have a role in sanctions and export controls on Russia.

· Justice investigates and prosecutes violations of sanctions and export controls laws and provides legal reviews of sanctions’ designations. According to Justice officials, Justice enforces criminal violations of sanctions and export controls on Russia and has led or co-led several task forces to prosecute such violations and to seize and forfeit or freeze the assets of Russian oligarchs. For example, from March 2022 to February 2025, Justice led an interagency task force to prosecute violations of sanctions and export controls on Russia.

·

Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration supports

sanctions by providing technical analyses of weapons of mass destruction and

conventional arms transactions that may be subject to sanctions and making

recommendations during sanctions development. The National Nuclear Security

Administration also reviews export license applications for munitions and

dual-use items, which may include parties subject to sanctions. According to

Energy officials, the U.S. Energy Information Administration produces energy market

analysis, data, research, and forecasts. It also prepared market impact

analyses of proposed sanctions on Russia for Treasury and the National Security

Council (NSC). Officials also noted that Energy’s Office of International

Affairs provides feedback on potential sanctions targets related to violations

of sanctions on Russian oil.

U.S. Agencies Have Not Established Objectives Linked to Measurable Outcomes with Targets for U.S. Sanctions and Export Controls on Russia

We identified three broad categories for the objectives of U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia based on our analysis of State, Treasury, and Commerce documents, and other reports and studies. However, we found that these agencies have not established agency-level objectives that are linked to measurable outcomes with targets for their efforts.

Objectives of U.S. Sanctions and Export Controls on Russia Fell into Three Broad Categories

|

Perspectives on the Three Broad Categories for the Objectives of U.S. Sanctions and Export Controls on Russia The 11 knowledgeable stakeholders that we interviewed generally agreed with our broad categories of objectives. One stakeholder said there was an understanding at the NSC that the goals for U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia were going to be about reducing Russia’s resources, degrading the war effort, and holding bad actors accountable. Another stakeholder noted that the three primary objectives of U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia are to reduce Russia’s revenues from commodity exports, such as oil, to cripple Russia’s capability to conduct the war in Ukraine, and to further harm the Russian economy. Holding malign actors accountable is a component of crippling Russia’s capability to conduct the war in Ukraine by preventing such actors from enabling and facilitating Russia. Source: GAO Interviews with selected stakeholders knowledgeable about U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia. | GAO‑25‑107079 |

Based on our analysis of State, Treasury, and Commerce documents, press releases, agency rules and regulations, and other reports and studies, we identified three broad categories for the objectives of U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia. We were able to broadly classify the objectives as

· impacting Russia’s economy, including depriving Russia of revenue;

· inhibiting Russia’s war effort; and

· holding those who support Russia’s war or abuse human rights accountable (“malign actors”).[27]

Officials from State, Treasury, and Commerce noted a variety of sources that provided insight into the objectives of U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia, including the NSC, executive orders, G7 leaders’ statements, agency press releases, and agency rules and regulations.[28] We asked agency officials about information that they obtained from the NSC and reviewed the other sources.[29]

· NSC. NSC provides broad strategic direction to agencies regarding the objectives and goals of U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia. For example, according to State, Treasury, and Commerce officials, they have participated in interagency meetings through the NSC that included a discussion of the objectives and goals of sanctions and export controls on Russia.

· Executive orders. State officials also directed us to Executive Orders 14024 and 14114 as relevant documents that contain objectives of U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia but explained that the objectives are not limited to those in the executive orders.

· G7 leaders’ statements. According to Treasury officials, five G7 leaders’ statements contained the objectives of sanctions and export controls on Russia. While these statements included numerous objectives of sanctions and export controls on Russia, they were not specific to the U.S.

· Agency press releases. State and Treasury officials also told us that the broad objectives for U.S. sanctions and export controls were publicly stated in agency press releases. We identified nearly 100 State press releases and fact sheets, nearly 100 Treasury press releases, and over 90 Commerce press releases from the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine through January 2025. From these, we derived various objectives of U.S. sanctions or export controls.[30]

· Agency rules and regulations. According to Commerce officials, objectives of their export controls can be found in their published rules and regulations. Based on a review of selected Commerce rules, we found that they included a variety of policy statements but were generally consistent with the language provided in associated press releases.[31]

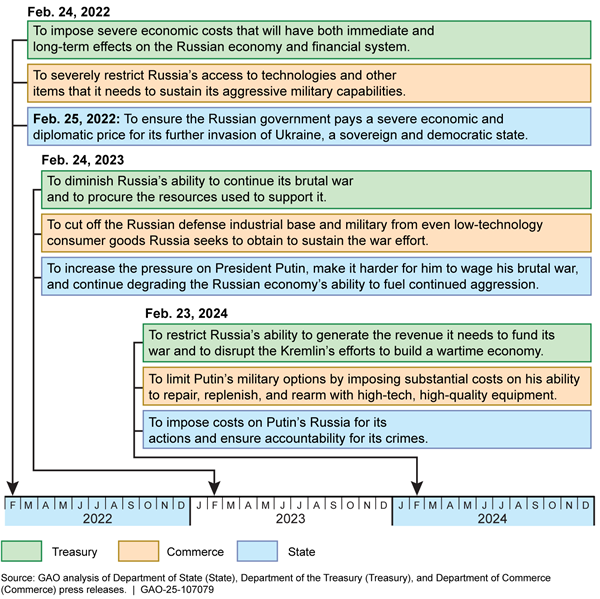

Figure 1 shows examples of objectives from agencies’ press releases beginning the first day of the invasion, February 24, 2022, through February 23, 2024.

Figure 1: Examples of Objectives of U.S. Sanctions and Export Controls on Russia from Agency Press Releases, February 24, 2022 – February 23, 2024

Note: According to Commerce officials, the objectives of U.S. export controls on Russia are found in Commerce’s rules and regulations. We reviewed the final rules that are associated with Commerce’s press releases in the figure above and found that these rules included similar language to those found in the press releases.

In addition, we found that the language used in agency press releases to describe certain objectives of U.S. sanctions and export controls evolved slightly over time. For example, the press releases from State and Treasury used language at the start of the war in 2022 that focused on inflicting widespread, severe costs on the Russian economy, such as

· ensuring the Russian government pays a severe economic and diplomatic price for its further invasion of Ukraine (State); and

· imposing severe economic costs that will have both immediate and long-term effects on the Russian economy and financial system (Treasury).

However, in 2023, the objectives in several agency press releases had a more specific focus, such as degrading Russia’s future energy production and export capabilities and reducing Russia’s revenues from the metal and mining sectors. State and Treasury press releases in August 2024 generally continued this narrower focus, including:

· disrupting support for Russia’s military-industrial base and curtailing the Kremlin’s ability to exploit the international financial system and generate revenue in furtherance of its war against Ukraine (State); and

·

holding Russia accountable for its aggression; disrupting Russia’s

military-industrial base supply chains and payment channels; and further

limiting Russia’s future revenue from metals and mining (Treasury).

U.S. Agencies Have Not Established Specific Objectives that are Linked to Measurable Outcomes with Targets

While U.S. agencies receive broad, strategic direction from the NSC, they have not established agency-specific objectives linked to measurable outcomes with targets for their sanctions and export controls activities related to Russia.[32] We asked officials from State, Treasury, and Commerce about the objectives of their agencies’ sanctions and export controls on Russia.[33] We received the following responses, which are not reflected in any agency documents:

· State officials noted that the objectives are to deprive Russia of revenue, hinder its use of the international financial system to conduct its war, disrupt networks that support Russia’s military-industrial base, increase the costs to Russia of perpetrating its war of aggression against Ukraine, and promote accountability for actions that cause harm or enable Russia to continue its war against Ukraine.

· Treasury officials said the objectives are to deprive Russia of revenue and deprive Russia of key inputs needed to sustain and finance its war in Ukraine.

· Commerce officials said the objectives of U.S. export controls on Russia have broadly been to degrade Russia’s ability to wage war against Ukraine and maintain its military force. Officials added that the goals are to stop direct trade in sensitive items to Russia, deny Russia access to sensitive items through third countries, impose measures to diminish the economic resources Russia needs to support its military and defense industrial base, and cut off access by the Russian elite to allied luxury goods.[34]

In addition, we asked agency officials how they tracked and measured progress on sanctions and export controls on Russia. Agency officials referred us to economic evaluation units within each agency.

· A senior official in State OCE told us that the office focused on conducting analyses of the effectiveness of U.S. export controls because it was an area where they could have the most impact. However, these analyses did not include measurable outcomes with specific targets on the effectiveness of U.S. export controls. Further, this office did not conduct other analyses that would help State officials understand sanctions’ impact on Russia’s economy because of the office’s limited resources, according to officials. As of May 2025, the office is no longer analyzing U.S. sanctions or export controls on Russia due to insufficient resources, according to a State official.

· Treasury OFAC examines both macroeconomic and microeconomic indicators for Russia such as Russia’s monthly tax revenue data, GDP, and the oil sector, according to a senior OFAC official. For example, OFAC’s Sanctions Economic Analysis Division issued a monthly oil price cap dashboard that included trends in Russia’s oil revenues. However, this official told us that this division does not have an analytical construct to assess its sanctions programs systematically; rather, they analyze specific sectors, focusing largely on energy. Moreover, Treasury’s assessments did not refer to measurable outcomes with specific targets that the agency was tracking to assess the effectiveness of its sanctions on Russia.

· Commerce’s Office of Technology Evaluation, an office within BIS, monitors open source information, general economic data, and intelligence for developments in Russia’s wartime production and the state of its economy, according to BIS officials. However, these analyses are not linked to measurable outcomes with specific targets for export controls on Russia. For example, Commerce analyzed the increased costs that export controls have imposed on Russia, but this analysis did not include targets, such as a specific percentage increase in Russia’s costs to import critical items, that would enable Commerce to assess its progress in imposing export controls.

Federal internal control standards state that management should define objectives in specific terms so they are understood at all levels of the entity and in measurable terms so that performance toward achieving those objectives can be assessed.[35] Some State and Commerce officials told us that they had defined objectives of sanctions and export controls on Russia and that they had some measures of the outcomes of those sanctions and export controls. However, State and Commerce officials did not provide us with documentation that linked agency-level objectives to outcomes used to measure their progress in achieving their objectives, nor did they provide any specific targets for their desired outcomes. Another State office noted that they had not established objectives linked to measurable outcomes because they received regular, direct feedback from the NSC on the prioritization of sanctions and export controls actions.[36]

Additionally, Commerce officials stated that measuring the efficacy of export controls is difficult. Similarly, Treasury officials noted there are challenges to establishing sanctions objectives that are linked to measurable outcomes, as potential metrics would have to account for limitations such as the availability of trade data and the volatility in, and complexity of, commodities markets. Treasury officials also cited the evolution of foreign policy guidance and national security priorities, which could inhibit the linking of specific objectives to measurable outcomes with targets.

While there are inherent difficulties in assessing the progress of sanctions and export controls, it is nonetheless possible to develop measurable outcomes with specific targets in complex settings. For example, measurable outcomes of U.S. sanctions and export controls could include a targeted percentage decrease in Russia’s oil revenues or a specific decrease in Russia’s imports of products on Commerce’s Common High Priority List that Russia uses for its war effort. Targets guide agencies’ activities and provide a way for agencies to assess progress toward achieving their objectives. Without agency-level objectives that are documented and linked to measurable outcomes with specific targets, the agencies may not have clear direction for their activities. Moreover, they are unable to determine progress toward achieving targeted outcomes. This limits the U.S. government’s ability to determine the effectiveness of its collective Russia-related sanctions and export controls efforts. Such information is crucial for improving current efforts and may provide important lessons learned for future scenarios where the U.S. government is considering the use of sanctions and export controls.

U.S. Agencies Have Made Some Progress Toward Broad Sanctions and Export Controls Objectives, but Challenges Remain

We examined progress U.S. agencies had made toward the three broad categories of sanctions and export controls objectives we identified. We found that various indicators of Russia’s economy declined following the imposition of sanctions and export controls and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, but partially recovered. We also found that Russian actions diminished the effectiveness of the price cap that the U.S. government imposed on Russian oil. In addition, we found that U.S. export controls hindered Russia’s efforts to access military technology but could not completely prevent access due to enforcement challenges. Finally, we identified various mechanisms by which U.S. agencies attempt to hold Russian malign actors accountable, but the agencies have challenges in assessing the effectiveness of those efforts.

Russian Economic Indicators Declined in 2022 Following Sanctions and the Invasion, then Partially Recovered

We found evidence that Russia experienced initial declines and partial recoveries in various economic indicators, suggesting sanctions and the invasion affected Russia’s economy.[37] Our estimate of what might have happened absent the invasion and sanctions in 2022 suggests that Russia’s GDP growth was lower than expected in 2022. Relevant studies report declines in economic indicators in 2022 and partial recoveries afterward.[38] Some recoveries may be related to higher military expenditures, which may have contributed to subsequent increases in Russia’s GDP. However, such high military expenditures and other factors associated with the sanctions and invasion such as Russia’s decreased participation in global markets could affect Russia’s future growth potential, according to agency officials, analyses, and knowledgeable stakeholders. These stakeholders indicated that Russia’s anticipation of and adaptation to sanctions limited the effect of sanctions on economic outcomes.

Our Analysis of Russian Economic Indicators

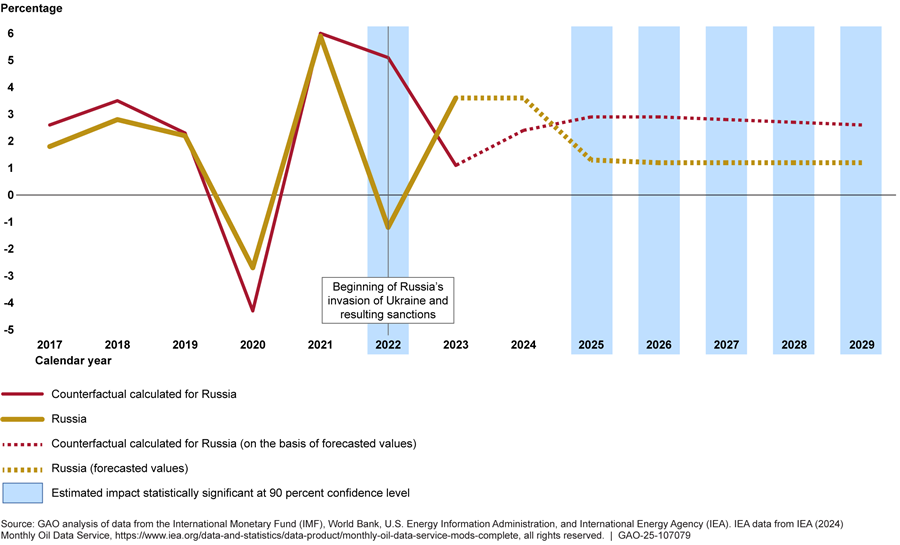

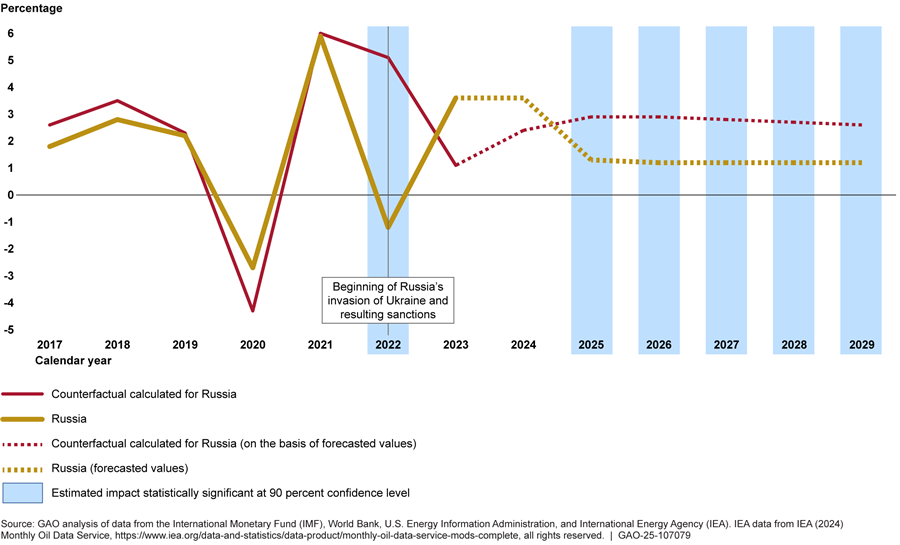

To determine the effect of the events in 2022, including the invasion and resulting sanctions on Russia, we analyzed the following economic indicators: economic growth (real GDP percentage change), per capita real GDP, and inflation.[39] Our analysis found that Russia’s economic growth was lower than expected in 2022.

Specifically, we found that Russia’s economic growth in 2022 was about 6 percentage points lower[40] than what we estimate would have occurred absent the events of 2022, including the invasion and resulting sanctions.[41] Moreover, we also found that Russia’s forecasted economic growth is expected to be lower each year from 2025 to 2029 than what we estimate would have happened absent the events of 2022, but these results may be less reliable because they are based on forecasted data.[42] Our analysis could not isolate the effect of sanctions from the effect of other simultaneous events such as the war in Ukraine, but does suggest that events in 2022 hurt the Russian economy. However, our analysis did not find that Russia’s economic growth in 2023 and 2024 was statistically different from what it might have been absent the events in 2022, including the invasion and resulting sanctions.[43]

|

Methodology to Estimate How Russia’s Economy Would Have Evolved Absent Events in 2022 and Beyond We used a methodology that enables comparison to a counterfactual situation representing how Russia’s economy might have evolved absent events in 2022 and beyond, including the invasion and sanctions. The synthetic control methodology can be used when evaluating interventions where there is no readily available comparison country or countries. The methodology creates a synthetic counterfactual so that the intervention can be evaluated by comparing the outcome of the treated country with the outcome of the synthetic counterfactual country. With the methodology, we calculated a counterfactual for Russia by matching Russia to other countries on the basis of economic indicators from 2017-2021. Specifically, we matched on the following predictors using their average values from the pre-sanctions period, consistent with literature that has used this methodology: inflation percentage change, real GDP percentage change, real GDP per capita, as well as the value of agriculture, value of industry, trade openness, gross capital formation, and oil rents in terms of percentage of GDP. We then compared values of Russia’s actual and forecasted economic indicators to the corresponding values for the counterfactual calculated for Russia. For additional details on the synthetic control methodology, see appendix III. Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑25‑107079 |

To determine the effect of the events in 2022, including the invasion and resulting sanctions, on Russia, we calculated a counterfactual Russia representing what Russia might have experienced had the events in 2022 not occurred (see sidebar). Figure 2 compares Russia’s economic growth to the counterfactual calculated for Russia and indicates when a yearly difference was statistically significant.[44]

Figure 2: Comparison of Russia’s Economic Growth to Counterfactual Calculated for Russia, 2017 – 2029

Notes: We used the percentage change in real gross domestic product (GDP) as our measure of economic growth. Russia values and forecasted values come directly from IMF’s World Economic Outlook data. We implemented the synthetic control methodology to calculate the counterfactual for Russia. There were 20 nations in our pool of comparison countries for which data were available. The countries that we ultimately weighted in our counterfactual calculated for Russia were Poland, Mexico, Azerbaijan, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, and Sudan. Across countries, the IMF data for real GDP percentage change were generally forecasted starting in 2024, though some countries’ forecasted data started earlier. The R-squared, which measures how well the counterfactual calculated for Russia matches Russia’s pre-treatment outcomes, explains 93.3 percent of the variation in the GDP percentage change. We inferred the confidence level by conducting permutation testing that considered other countries to be the treated country instead of Russia if those other countries generally had a pre-2022 fit similar to Russia’s, which we considered for this model as a mean squared prediction error limited to three times that of Russia’s. For additional details on the synthetic control methodology, see appendix III.

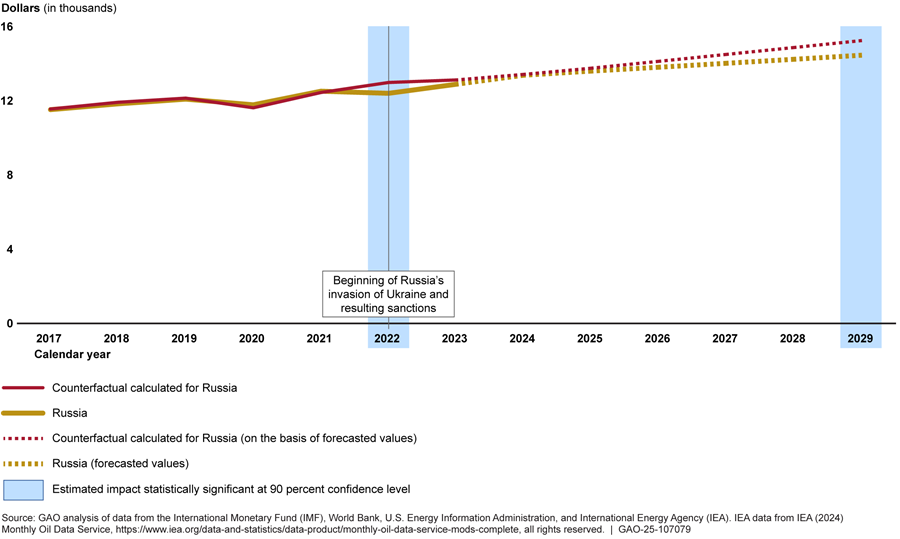

We also examined real GDP per capita.[45] In addition to finding an initial decline in economic growth, we found that Russia’s real GDP per capita in 2022 was about $584 lower[46] than what we estimate would have occurred absent the events of 2022, including the invasion and resulting sanctions.[47] For context, Russia’s real GDP per capita was $11,953, averaged over 2017 through 2021. Most of the knowledgeable stakeholders indicated that sanctions have impacted Russia’s economy but have not caused a major economic crisis.[48] Similarly, studies we reviewed reported initial declines in economic indicators following the invasion and sanctions and subsequent partial recoveries.[49]

Russia’s actions before and after the 2022 sanctions appeared to have limited the decline in its economic outcomes. Knowledgeable stakeholders as well as studies we reviewed suggested that Russia’s economy benefited from the actions of its central bank following the invasion and resulting sanctions, such as raising interest rates and imposing capital controls. In addition, knowledgeable stakeholders explained that Russia’s history with sanctions enabled it to prepare for and adapt to the sanctions following the 2022 invasion.

Russia’s Military Spending in Relation to GDP

Military spending is a component of GDP, and Russia’s higher military spending may affect GDP and forecasts of its economy. Data from Stockholm International Peace Research Institute show an increase in Russia’s military spending as a percentage of GDP from 3.6 percent in 2021 to an estimated 7.1 percent in 2024. In addition, the IMF’s January 2024 World Economic Outlook Update revised Russia’s projected growth upward for 2024 to reflect stronger-than-expected growth in 2023 associated with high military spending and private consumption stemming from wage growth.[50] Treasury also incorporated the revised IMF projections into an updated analysis of Russia’s GDP and found that sanctions may have had a smaller effect than it had previously estimated. In April 2024, Treasury estimated that Russia’s real GDP was over 2 percent lower in 2024 than had been predicted prior to the invasion, whereas in December 2023 Treasury had estimated that Russia’s real GDP was 5 percent lower than pre-invasion.[51] Similarly, a publicly available study we examined noted that although Russia’s GDP growth rate at the end of 2022 was negative, it was not as low as many forecasts had predicted.[52]

An official from State OCE explained that as Russia transforms its economy into a military economy, macroeconomic indices such as GDP are not representative of the economy’s health. For example, the State official noted that while building tanks would increase a country’s GDP, it is not a productive use of a country’s resources. Similarly, knowledgeable stakeholders explained that Russia’s GDP was likely lower because of sanctions but was also inflated because of military spending. Further, knowledgeable stakeholders indicated that military spending and employment has allowed Russia to maintain employment. One stakeholder indicated that military spending and employment constrained Russia’s ability to produce. Moreover, high military spending might come at the expense of investment in economically productive programs, according to an IMF publication.[53] Thus, such high military spending could have implications for Russia’s long-term growth.

Additional Long-Term Implications on Russia’s Economy

Agency assessments and knowledgeable stakeholders indicate that Russia’s long-term economic conditions may be worse following sanctions and the invasion. Knowledgeable stakeholders noted that Russia’s continued heavy reliance on oil as an export may limit the country’s future competitiveness. Similarly, a Treasury analysis noted that Russia’s decreased participation in global markets could harm its potential for growth. According to Bloomberg Economics, sanctions designations on banks such as Gazprombank made toward the end of 2024 could further fracture Russia’s financial market and increase Russia’s reliance on remaining foreign-owned institutions in Russia that still have connections to the global financial system. In addition, a senior Treasury OFAC official and knowledgeable stakeholders noted that the high emigration of skilled workers following the invasion is contributing to labor challenges that could affect long-term growth. Finally, IMF’s October 2024 World Economic Outlook noted a sharp slowdown in Russia’s economy between 2023 and forecasted values for 2025 as private consumption and investment slowed.[54]

Russian Actions and Other Factors Diminished Effectiveness of Oil Price Cap and Other Sanctions

The U.S. government and its partners sought to limit Russia’s revenues by imposing a price cap on Russian oil and implementing financial sanctions, according to Treasury. However, Russia limited the effects of these sanctions by shifting oil away from providers subject to the price cap and developing an alternate payment system with China to reduce its dependence on U.S. assets. In addition, other factors such as high commodity prices for oil and gas—a key source of revenue for Russia—enabled Russia to continue financing the war.

Price Cap on Russian Oil

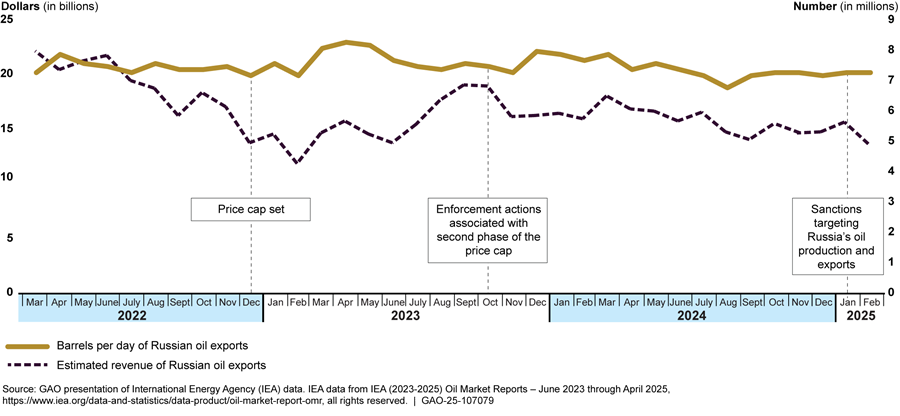

The Coalition (including the U.S.) implemented the price cap in December 2022 in an effort to reduce Russia’s oil revenues while maintaining the stability of global energy markets. A more aggressive policy could have triggered a spike in oil prices and affected the U.S., according to knowledgeable stakeholders. Russia initially responded to the price cap by selling its oil at a significant discount to continue accessing dominant Coalition country service providers, according to Treasury.[55]

However, by summer 2023, Russia began to export more of its oil via a “shadow fleet.” The shadow fleet is composed of oil tankers that are anonymously owned or have opaque corporate structures, are solely deployed to trade oil or oil products from Russia or certain other sanctioned countries, and engage in various deceptive shipping practices such as relying on unknown or fraudulent insurance. These vessels provide Russia an outlet for its oil exports and a means to circumvent sanctions.[56]

Russia’s shadow fleet diminished the effectiveness of the oil price cap by shifting oil exports away from providers subject to the cap, making Russia less dependent on western ships and insurance, according to knowledgeable stakeholders. As Russia invested significant resources to export more of its crude oil and petroleum products with its shadow fleet in the summer and fall of 2023, the discount on Russian oil narrowed, according to Treasury analysis. Reflecting this shift, the percentage of Russian crude exports covered by the price cap on Russian oil declined from 83 percent in October 2022 to about 30 percent in December 2023, according to Energy officials.

In response to Russia’s use of its shadow fleet, the Coalition launched the second phase of the price cap in October 2023 to tighten enforcement of oil trades with Coalition service providers. The U.S. has taken several actions to enforce the price cap, including imposing sanctions on vessels and shipping companies that have violated the price cap and issuing alerts on how to identify and mitigate evasion efforts, according to Treasury.[57] This second phase increased the costs to Russia of selling its oil via the shadow fleet, according to Treasury and State officials. According to State officials, the sanctions against additional entities involved in Russia’s oil trade contributed to increased transportation costs and enabled countries to negotiate greater discounts on Russian oil.

We examined trends in Russian oil production, export, and revenues. We found that Russia’s oil export revenue declined somewhat in 2022, at the start of 2023 following the implementation of the price cap, and at the end of 2023 following the second phase of the price cap’s enforcement actions, but has also recovered to some degree over time (see fig. 3). However, overall oil production has been relatively stable since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Compared with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)+,[58] Russia’s market share has also remained stable.[59]

Notes: Revenue figures represent combined crude and product (including gasoline and diesel) exports. The price caps per barrel set for different types of oil exports include: $60 for crude, $100 for premium products, and $45 for discounted products. On July 18, 2025, the United Kingdom and the European Union announced they would lower the price cap for Russian crude oil from $60 per barrel to $47.60 per barrel, effective September 2, 2025, and September 3, 2025, respectively. The European Union also established an automatic mechanism to adjust the cap. According to the International Energy Agency, data in this figure were derived by granular analysis and estimates of country of origin data in cases where shipments transit via third countries. They may differ from customs information due to calculation methodology and estimates updates. Data presented in this figure generally reflect the newest available data for each month and year.

Energy officials explained that additional factors beyond the price cap influence Russia’s oil revenues. They noted that the global price of oil, multiple import bans on Russian oil, and the general risk in being involved in the Russian oil trade have had a larger effect on Russia’s oil revenues.[60] Studies describe high oil revenues for Russia in 2022, with some decline in 2023 concurrent with the price cap and the EU oil embargo.[61] Studies also noted that high commodity prices, like those for oil and gas, contributed to a large financial surplus immediately after the start of the war. High revenues have enabled Russia to continue financing the war, according to studies and knowledgeable stakeholders. Similarly, the IMF reported that Russia used high oil and gas revenues to finance a larger deficit in 2022.[62]

Russia’s trading partners for oil have changed from European countries to countries such as China, India, Turkey, and others, which do not participate in the price cap coalition. This shift in trading partners may have long-term implications for Russia’s energy sector. According to State officials, Russia’s increased reliance on a limited number of partners represents a strategic and economic vulnerability that gives leverage to a handful of importers to negotiate oil prices. According to State officials, the Russian government is accepting a trade-off between revenue now and investment in future production. Further, Russia reduced or cut off the supply of natural gas to some European countries in 2022 to reduce their support for Ukraine, exposing its unreliability as an energy supplier. As importing countries turn to more reliable sources for energy, there are limited opportunities for Russia to secure additional markets. By trading with countries not honoring the price cap, Russia may be selling above the $60 price cap, but its costs to ship oil have also increased, according to State officials.

Other Effects of Sanctions on Russia’s Finances

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the U.S., EU, and partner sanctions immobilized $280 billion in Russian reserves in its National Wealth Fund and Central Bank sovereign assets, according to a Treasury analysis as of December 2023. One knowledgeable stakeholder highlighted the immobilization of Russian assets as a success. Other knowledgeable stakeholders cited the success of sanctions in forcing Russia to spend available reserves and sovereign wealth funds, including the savings from oil revenues over the years. As of late 2023, Russia’s National Wealth Fund held about $146 billion, nearly half of which ($72 billion) was in gold and liquid yuan assets, according to Treasury.

However, Russia took actions that were likely in preparation for sanctions. According to the IMF, Russia’s efforts to reduce fiscal deficits after the invasion of Crimea and following sanctions in 2014 resulted in lower public debt relative to GDP, providing a significant buffer to the government’s finances.[63] Additionally, inflation targeting brought down inflation from double digits to 4 percent.[64] Russia also took steps to reduce its reliance on the U.S. dollar by developing alternate payment platforms with China, according to knowledgeable stakeholders. Russia’s reduction of holdings in U.S. dollars was one factor that contributed to reduced external liabilities and bank vulnerabilities, according to the IMF.[65] However, while reduced reliance on the U.S. dollar partially shielded the Russian economy from the effects of sanctions, it also isolated Russia’s economy and increased its reliance on a small number of countries.

U.S. Export Controls Have Hindered Russia’s Efforts to Access Military Technology, but Enforcement Challenges Remain

U.S. export controls have hindered Russia’s efforts to access military technology for the war in Ukraine but have not completely prevented it from obtaining U.S. technologies. U.S. agencies face various challenges in enforcing export controls on Russia, such as third-party procurement networks that enable Russia to circumvent export controls.

Export Controls on Military Technologies

According to Commerce officials, export controls have degraded Russia’s ability to take advantage of high-level military technologies from the U.S. and its allies, either by cutting off reliable access, increasing prices, reducing quantity and quality, or delaying Russia’s acquisition of these technologies. According to State officials, the lack of access to modern, high-tech components leaves Russia reliant on stockpiles of decades-old military equipment. Russia cannot manufacture enough of its own munitions or purchase from modern economies, so it depends on imports of lower-quality replacements from Iran and North Korea.

Commerce assesses that export controls have diminished the economic resources Russia needs to support its military and defense industrial base by increasing its costs to procure items for its war effort. Specifically, because of Russia’s increased costs attributable to U.S. export controls, Commerce estimates that there is a $5 billion gap between the critical items that it likely sought to import in 2023 and the items that it was actually able to import that year. Russia is also paying more than double the amount on average for microelectronics following the invasion of Ukraine than it did in the years prior to the invasion.[66]

Nearly all of our 11 knowledgeable stakeholders noted that U.S. export controls on Russia have achieved some success. One stakeholder stated that Russia has fundamentally reshaped its economy to supply its war effort, including repurposing factories for military production, while another said that it takes Russia a large amount of time, effort, and cost to bypass export controls. The cost of circumventing these controls hinders Russia’s war effort, according to another knowledgeable stakeholder.

Studies that we examined also found some evidence that export controls initially hindered Russia’s ability to acquire technology for its war effort. Using 2022 data, two studies found evidence of a decrease in exports to Russia in certain high-tech sectors, such as electronics and precision machinery, which were relatively more targeted by export controls.[67]

Trade Trends Related to Export Controls on Russia

Export controls have not completely prevented Russia from obtaining products that it sought. Some of these products are categorized by the four tiers of the Common High Priority List (CHPL), a set of 50 product codes for classifying categories of items that Russia seeks to procure for its war effort that was developed by the EU, Japan, U.S., and the United Kingdom.[68] Product categories in tiers 1 and 2 are of highest concern for diversion to Russia based on their capability to fuel Russia’s war effort, according to Commerce.[69] Analyses from Commerce and State show that global exports of the four tiers of CHPL products to Russia declined sharply following the Russian invasion of Ukraine but rebounded somewhat in late 2022 and 2023.[70]

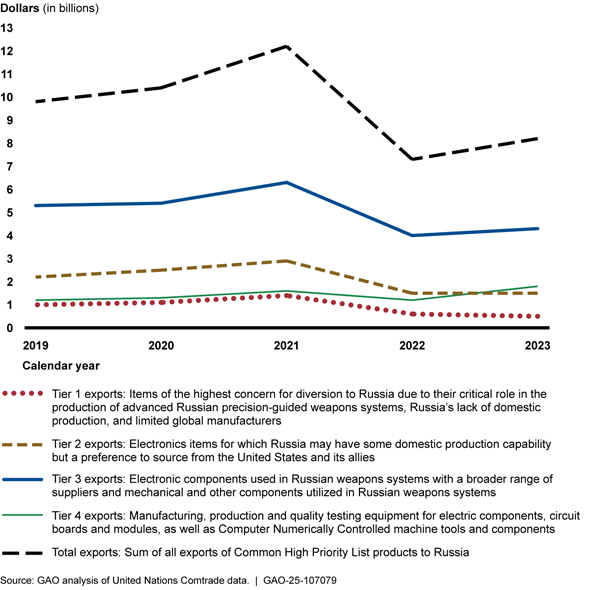

Our analysis of annual export data shows similar trends.[71] Between 2021 and 2022, world real exports to Russia of CHPL products declined from $12.2 billion to $7.3 billion, then increased slightly in 2023 to $8.2 billion.[72] Figure 4 shows that the slight increase in real exports in 2023 was due to higher exports of tier 3 and 4 products, while real exports in tier 1 and 2 products were lower in 2023 than 2022.

Figure 4: Dollar Value of World Exports to Russia of Common High Priority List (CHPL) Products, 2019 – 2023

Notes: This figure is based on United Nations (UN) Comtrade data and is reported in inflation-adjusted 2024 dollars. The EU, Japan, U.S., and United Kingdom developed the CHPL, a common set of 50 product categories related to products that Russia seeks to procure for its weapons programs. The data include reported exports to Russia from 51 countries and Hong Kong, covering 95 percent of total reported exports to Russia in the pre-invasion period of the figure (2019 to 2021). Data from 2023 were the most recent available for all 51 countries and Hong Kong at the time of our analysis. Russian import data are not available in the United Nations Comtrade database after 2021.

Trends in exports to Russia of products subject to U.S. export controls also vary by country and region of origin. Commerce analyses show that exports of such products from some regions remain lower than they were prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, while others are above pre-invasion levels.[73] As of July 2023, according to Commerce analyses, exports of products subject to U.S. export controls from the EU, East Asia, and Southeast Asia declined after the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and had not returned to pre-invasion levels.[74] However, such exports from India, China, and Hong Kong declined immediately following the invasion but returned to pre-invasion levels by early 2023. Commerce analyses showed that Central Asian countries’ exports of products subject to U.S. export controls to Russia increased sharply after February 2022 and remained above pre-invasion levels through July 2023.[75] The increased exports from these countries to Russia may indicate circumvention of U.S. export controls, according to Commerce.

State analyses from February 2024 show that exports of all CHPL products to Russia from the U.S. and partner countries that imposed similar export controls on Russia have been reduced, but some products from these countries are still reaching Russia.[76] Moreover, some of these products have been found in Russian weapons, according to a State document. State reported that the majority of CHPL products from the largest U.S. and EU firms arriving in Russia were either produced in or shipped from China. China accounted for nearly 80 percent of exports to Russia of CHPL products since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, according to State and Commerce analyses. In addition, since the early days of the invasion, China has significantly increased its support of the Russian defense industrial base. According to a State analysis of Russian customs data, average monthly Russian imports of CHPL products from China increased by 87 percent in dollar value in the final six months of 2023 compared with the first six months of the war. From the start of the invasion through January 2024, Chinese intermediaries supplied more than $2.3 billion worth of CHPL products to Russia that were produced by the U.S. and partner countries, according to State.[77]

Challenges for Export Controls Enforcement

State and Commerce analyses suggest that one reason Russia can still access products subject to export controls is that Russia actively develops procurement networks in third countries. As of November 2023, evidence suggested this circumvention was increasing and Russia’s procurement networks were continuing to evolve, according to State officials. Commerce officials noted that lower-level technologies now subject to export controls on Russia tend to have greater foreign availability, and thus it is easier for Russia to obtain them. This makes it more challenging for Commerce to counter export controls circumvention of those items compared to higher technology items that have lower foreign availability. According to Commerce, it continued modifying its export controls throughout 2024 to target circumvention, including by expanding controls on third country procurement networks, imposing controls targeting shell companies in transit jurisdictions like Hong Kong, and by expanding the reach of controls on CHPL products.

According to Commerce officials, the continual evolution of third-country supply networks has made it challenging to apply export controls without affecting the broader global economy. Nearly all the knowledgeable stakeholders that we interviewed cited third-party diversion as a challenge to enforcing export controls on Russia. Some of these stakeholders noted that once a company is identified and sanctioned for export controls violations, others take its place.

Knowledgeable stakeholders also noted the following challenges:

· Financial institutions such as banks have a better understanding of how to comply with sanctions, rather than export controls, as banks have less experience complying with new export controls on Russia.[78] Banks see financial transactions, rather than the item being purchased, so it is difficult for a bank to know if someone is using its systems to evade export controls;[79]

· Manufacturing companies are not required to know all the customers of their products after the initial sale;

· Small items, such as semiconductors, are easier to smuggle due to their size, making it more difficult to enforce export controls;

· Products made overseas and exported to Russia may be subject to export controls but do not show up in U.S. customs data. As a result, BIS is unaware of whether the companies that manufacture these products may have violated U.S. export controls on Russia.

|

Knowledgeable Stakeholders’ Suggestions for Improving U.S. Export Controls Enforcement “The U.S. government must do more to push semiconductor firms and others to tighten up on who they are selling to a couple of layers down the chain since we are seeing a lot of leakage. The U.S. government needs to cooperatively work with companies to tighten up their vendor screening.” “The U.S. government could make an example of companies whose products end up in Russia through public enforcement actions.” “Putting export controls on selected items produced in G7 countries might be a more efficient approach to create additional complications for Russia, rather than placing export controls on everything at once.” “Specialists at BIS should be working with the Department of Defense and the Department of Energy to figure out what components are critical. More resources are needed to create a more focused approach to export controls on Russia. The U.S. government could have a database of violators on the export controls side and place high fines on export control violations. These steps will encourage companies to invest in compliance.” “The U.S. government would do better to focus on things that the West has a near monopoly on, such as microchips, and to try to interdict the flow of those items to Russia. The U.S. government could impose more secondary sanctions to address items reaching Russia from China.” Source: GAO Interviews with selected stakeholders knowledgeable about U.S. sanctions and export controls on Russia. | GAO‑25‑107079 |

Studies also noted other challenges to enforcing export controls such as the complexity of global supply chains, the absence of large economies such as China imposing similar controls on Russia, and the limited experience of partner countries with implementing and enforcing export controls.

Commerce and State officials noted that improvements could be made to export controls enforcement. Commerce officials noted that export controls overall could be more effective with broader third-country commitment to prevent diversion of controlled items and improved transparency in global trade data. Export controls have become more difficult to analyze over time because third-party procurement networks are becoming more elaborate and data are less available, according to a State document and State officials.[80] State also acknowledged that it must increase pressure on, and provide more information to, U.S. firms to prevent their goods from fueling the Russian war effort.

State and Commerce have taken steps to address enforcement challenges. For example, Commerce has worked with international partners in the G7 Sub-Working Group on Export Control Enforcement, as well as the Export Enforcement Five group to share information and best practices on enforcing export controls, according to Commerce officials.[81] Commerce has also issued alerts and guidance for industry on third-party diversion and export control evasion, and met with leaders of U.S. companies whose products have been found in Russian weaponry to discuss the importance of ensuring that they know the ultimate end users of their products, according to a Commerce document. State has engaged with countries such as the United Arab Emirates on sanctions evasion concerns and imposed sanctions on over 40 entities associated with third-country support for Russia’s war effort since 2022, including those in China, Belarus, and Iran, according to State officials.

Agencies Have Taken Actions to Hold Russian Malign Actors Accountable, but Have Challenges in Assessing Their Effectiveness

According to our analysis, Justice, Commerce, Treasury, and State have held malign actors accountable by using task forces to seize and forfeit or freeze assets and prosecute sanctions and export controls violations, placing restrictions on exports of luxury goods, and imposing sanctions designations and visa restrictions. However, agencies face challenges in assessing the effects of their efforts to hold Russian malign actors accountable for actions related to the 2022 war in Ukraine, making the broader effect of these actions unclear.

Task Forces to Freeze, Seize, and Forfeit Assets and Prosecute Sanctions and Export Controls Violations

|

Seizures of Sanctioned Russian Oligarchs’ Yachts Justice’s Task Force KleptoCapture coordinated the seizure of the two yachts described below to hold Russian oligarchs accountable for their attempts to evade U.S. sanctions. 1. The motor yacht Tango is a 255-foot luxury yacht owned by a sanctioned Russian oligarch. Justice officials coordinated with Spanish law enforcement to seize the Tango on April 4, 2022, marking the first seizure of an asset belonging to a sanctioned individual with ties to the Russian regime after the creation of the task force. The Tango is valued at approximately $90 million. 2. The motor yacht Amadea is a 348-foot luxury vessel owned by another sanctioned Russian oligarch. Justice officials coordinated with Fijian law enforcement to seize the Amadea in an operation announced on May 5, 2022. The Amadea is valued at approximately $230 million. Source: Department of Justice press releases. | GAO‑25‑107079 |

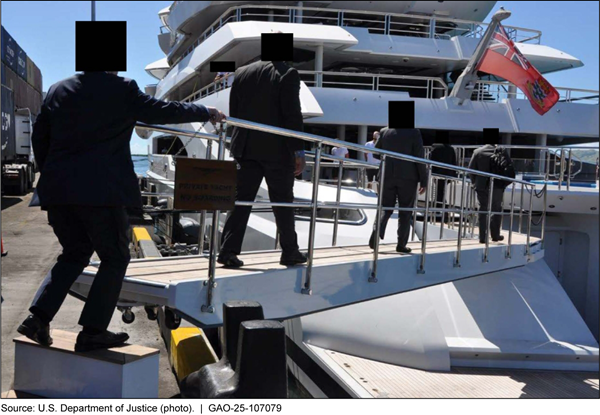

From March 2022 to February 2025, Justice led Task Force KleptoCapture, a U.S. domestic interagency task force dedicated to enforcing the sanctions, export restrictions, and economic countermeasures that the United States imposed in response to Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine. Task Force KleptoCapture’s mission was to use law enforcement tools, including criminal prosecutions and asset seizures and forfeitures, to enforce sanctions and export controls on Russia. According to Justice officials, the task force did not set quantitative goals or performance metrics, but it did track cases charged, arrests, dispositions, and assets seized, restrained, or otherwise subject to forfeiture. As of November 2024, Task Force KleptoCapture had restrained, seized, and obtained judgments to forfeit about $650 million in assets from Russians and charged more than 100 individuals with violating international sanctions or export controls levied against Russia or for related criminal conduct, according to Justice officials. Figure 5 below shows the seizure of the Amadea yacht, coordinated by Task Force KleptoCapture.

Figure 5: Task Force KleptoCapture Coordinated the Seizure of the Yacht, Amadea, Owned by a Russian Oligarch, Announced on May 5, 2022

Treasury and Justice are the lead U.S. agencies for the Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs Task Force (REPO), a multilateral task force established in March 2022 composed of representatives from the U.S., Australia, Canada, Germany, France, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the European Commission.[82] According to a Treasury official, the goal of the REPO Task Force is to enforce sanctions on Russian oligarchs’ assets. To this end, the task force tracks assets across the globe and restricts Russians from accessing the global financial system, according to this official. It also investigates and works to counter Russian sanctions evasion, including attempts to hide or obfuscate assets, according to a REPO Task Force document.

While REPO Task Force officials said that the task force does not measure success in terms of the number of targets or actions, a March 2023 Treasury press release noted some of the task force’s accomplishments. For example, it:

· blocked or froze more than $58 billion worth of sanctioned Russians’ assets in financial accounts and economic resources;

· seized or froze luxury real estate and other luxury assets, such as yachts, that are owned, held, or controlled by sanctioned Russians; and

· restricted sanctioned Russians’ access to the global financial system.

The Disruptive Technology Strike Force, launched in February 2023, is co-led by

Justice and Commerce to counter hostile nation states’ efforts to illicitly

acquire sensitive U.S. technologies that advance their authoritarian regimes

and facilitate human rights abuses, according to a Justice press release. As of

December 2024, the strike force had publicly charged 26 cases involving alleged

sanctions and export control violations and smuggling, among others, by actors

connected to Russia, China, and Iran, according to a Commerce document. The

cases brought by the strike force include the prosecutions of individuals and

entities accused of illicitly providing microelectronics and other advanced

technologies to companies affiliated with the Russian government and military,

according to a Justice press release.

Restrictions on Luxury Goods