CONSUMER PROTECTION

Actions Needed to Improve Complaint Reporting, Consumer Education, and Federal Coordination to Counter Scams

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107088. For more information, contact Seto J. Bagdoyan at bagdoyans@gao.gov and Howard Arp at arpj@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107088, a report to congressional requesters

Actions Needed to Improve Complaint Reporting, Consumer Education, and Federal Coordination to Counter Scams

Why GAO Did This Study

Scams, a method of committing fraud, involve the use of deception or manipulation intended to achieve financial gain. Scams often cause individual victims to lose large sums—in some cases their entire life savings.

GAO was asked to review federal agencies’ and businesses’ efforts to counter scams. This report examines, among other things, the extent to which (1) a comprehensive, government-wide strategy guides agency efforts; (2) selected federal agencies compile scam-related complaint data and agencies’ ability to estimate the total number of scams and related dollar losses; and (3) selected agencies measure the effectiveness of consumer education activities.

GAO analyzed publicly available information, agency documents, and agency consumer complaint data. GAO interviewed agency officials and representatives of relevant industries and advocacy groups.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 16 recommendations to various agencies to develop a government-wide strategy to counter scams, a national scam estimate, a common definition of scams, and evaluate the outcomes of consumer education efforts. The FBI disagreed with three recommendations related to the development of a national estimate, a definition of scams, and evaluating the outcomes of its consumer education efforts. GAO maintains the recommendations are valid, as discussed in the report. FTC neither agreed nor disagreed with the five recommendations made to it.

What GAO Found

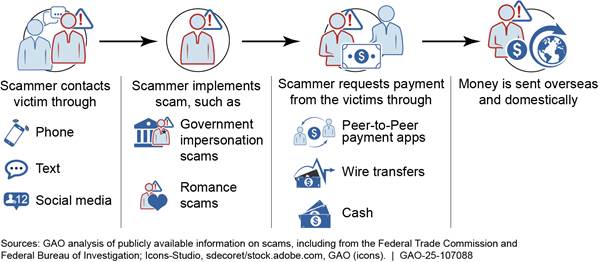

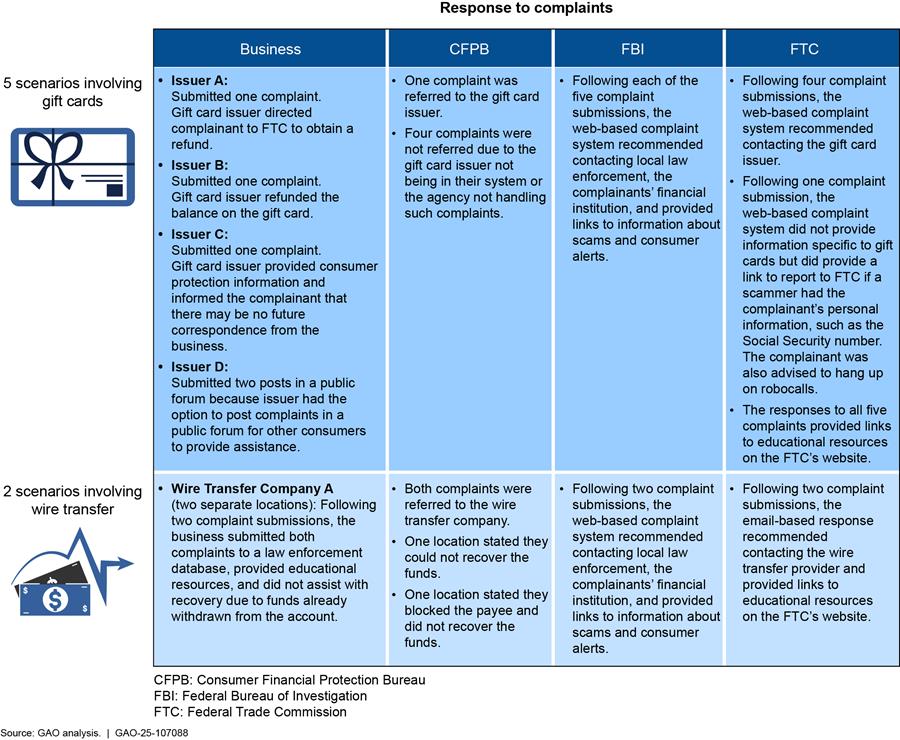

Scams occur in a variety of forms, have evolved with technology, and are a growing risk to consumers. Commonly, scams involve a scammer contacting the victim, engaging the victim with a particular type of scam, and requesting a payment for a false purpose.

Examples of a Scam Execution Process

Note: Other types of contact methods, scams, and payment methods exist.

The 13 federal agencies GAO spoke with engage in a range of efforts to counter scams. However, none were aware of a government-wide strategy to guide those efforts. Existing strategies did not focus on countering scams and did not apply across agencies. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is developing a cyber-enabled fraud strategy. The overlap in issues relating to scams and cyber-enabled fraud could provide FBI with the expertise to develop a government-wide strategy. Developing a government-wide strategy would better position agencies to coordinate and strategically target their efforts to counter scams.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), FBI, and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) receive, compile, and report on consumer complaints pertaining to issues including internet-related crime and scams. Data limitations, such as issues with how data are collected, do not allow agencies to calculate the exact number of scam complaints, but each agency can estimate the number it receives. For example, the FBI estimated that in 2023 it received approximately 589,400 scam-related complaints, resulting in losses of $10.55 billion. In addition, no government-wide estimate of the total number of scams and dollar losses exists. Improved data collection and estimates would better support federal efforts to understand the extent of this type of crime and develop ways to counter it.

CFPB, FBI, and FTC provide a variety of education resources for consumers. However, they do not measure the effectiveness of their education efforts on the consumers that receive them. Doing so would help the agencies understand how their education efforts are affecting consumers’ ability to recognize and protect themselves from scams and how the agencies might adjust their education materials to best help consumers.

Abbreviations

|

|

|

|

BBB |

Better Business Bureau |

|

CFPB |

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

FBI |

Federal Bureau of Investigation |

|

FTC |

Federal Trade Commission |

|

FDIC |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

|

FinCEN |

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network |

|

FCS |

Financial Crimes Section |

|

HSI |

Homeland Security Investigations |

|

IC3 |

Internet Crime Complaint Center |

|

OCC |

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency |

|

MSB |

money services business |

|

PIN |

Personal Identification Number |

|

P2P |

Peer-to-Peer |

|

Sentinel |

Consumer Sentinel Network |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 8, 2025

The Honorable Elizabeth Warren

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Kirsten Gillibrand

Ranking Member

Special Committee on Aging

United States Senate

Scams have been around for many years, have evolved with technology, and are a growing risk to consumers in the United States and around the world. Scams are one method of committing fraud that involve the use of deception or manipulation intended to achieve financial gain.[1] In perpetrating various scams, scammers deceive victims into making a payment or providing information to make a payment to benefit the scammer. These payments are often made via, but not limited to, Peer-to-Peer (P2P) payment apps, gift cards, and wire transfers.[2] In addition to inflicting emotional distress, scams have caused individual victims to lose tens of thousands of dollars, and, in some cases, their entire life savings. Although there is no government-wide estimate of the total amount lost to scams, as discussed later in this report, experts and available data indicate that scams may be costing Americans billions of dollars annually.

Criminal organizations throughout the world operate using networks of scammers. According to the United Nations, organized crime groups that facilitate certain scams continue to expand their operations and increase the sophistication of scams.[3] In an example highlighting the scope and reach of this issue, a 2023 international police operation against online financial crime, including scams, resulted in over 3,000 arrests and the seizure of $300 million worth of assets across 34 countries, including the United States.[4] Likewise, in the United States, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has identified the involvement of transnational criminal organizations that have taken hundreds of millions of dollars from Americans through scams.

Multiple federal agencies seek to prevent and respond to scams through efforts that include educating consumers, receiving complaints, investigating cases, and bringing law enforcement actions. We were asked to review the efforts of federal agencies and businesses to counter scams. This report

1. describes federal agencies’ activities to prevent and respond to scams and evaluates the extent to which there is a comprehensive, government-wide strategy to guide their efforts;

2. evaluates the extent to which federal agencies compile scam-related consumer-complaint data and are able to estimate the total number of scams and related financial losses;

3. describes federal agencies’ efforts to educate consumers about scams and evaluates the extent to which they measure their effectiveness;

4. describes selected private businesses’ efforts to counter scams; and

5. describes actions by federal agencies and selected private businesses to respond to consumer complaints related to scams.

To describe federal agencies’ activities to prevent and respond to scams, we reviewed documentation and interviewed officials from 13 agencies, including the

· Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB),

· Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Executive Office for United States Attorneys within DOJ,

· Federal Trade Commission (FTC),

· Federal Reserve (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and Federal Reserve Payment Services), and

· the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) within the Department of the Treasury.[5]

We identified these agencies by reviewing publicly available information describing their work related to scams.

To evaluate the extent to which a comprehensive, government-wide strategy exists across federal agencies to prevent and respond to scams, we asked officials from each of the 13 agencies if they were aware of any such strategy. We also reviewed existing U.S. strategies, such as those related to cyberthreats and fraud and money laundering, to determine whether any of these strategies may serve as a comprehensive, government-wide strategy to counter scams. Further, we reviewed strategies, developed by foreign countries, specifically intended to counter scams. We reviewed these strategies to understand what types of information had been included in the strategies. We identified these strategies through a review of publicly available information and attendance at the Global Anti-Scam Alliance summit in 2023.[6] We also interviewed the Consumer Federation of America, the Retail Gift Card Association, and a financial institution to discuss federal government coordination and strategies.[7]

To evaluate the extent to which federal agencies compile scam-related consumer complaint data, we obtained information from three federal agencies that told us they receive and report on consumer complaints related to scams: CFPB, FBI, and FTC. We obtained documents, interviewed officials, and reviewed their publicly available data, including reports specifically addressing scams.

To evaluate the extent to which federal agencies use scam-related consumer complaint data to estimate the full extent of scams and dollar losses, we held additional discussions with officials at CFPB, FBI, and FTC. We met with these agencies because they produce publicly available annual reports that contain data on scams and associated losses derived from the consumer complaint data they receive. Further, we reviewed our previous work related to the importance of knowing and understanding the scope of fraud in managing fraud risk.[8]

To describe federal agencies’ efforts to educate consumers about scams and evaluate the extent to which they measure the effectiveness of such efforts, we reviewed documentation from the 13 agencies discussed above. We had additional discussions with officials, specifically from CFPB, FBI, and FTC, to better understand the extent to which they measure the effectiveness of their consumer education activities. We focused on these three agencies because they provide consumer education materials directly to a broad range of consumers. We also reviewed our previous work related to program outcomes that can help federal agencies effectively manage and assess the results of their training efforts.[9]

To describe the efforts of selected private businesses to counter scams, we met with seven businesses. We met with two P2P payment app service providers, two gift card issuers, one money services business (MSB), and two financial institutions.[10] We selected these businesses based on various criteria, such as the ownership structure of the business and efforts to counter scams. The information obtained from these interviews is illustrative and cannot be generalized to other businesses.

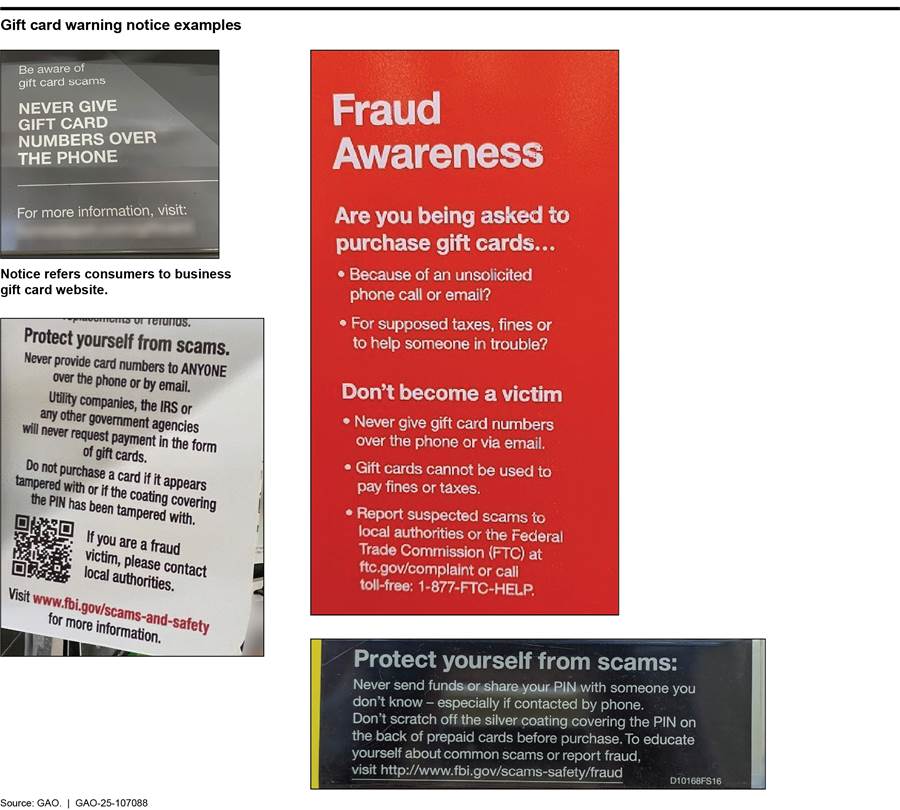

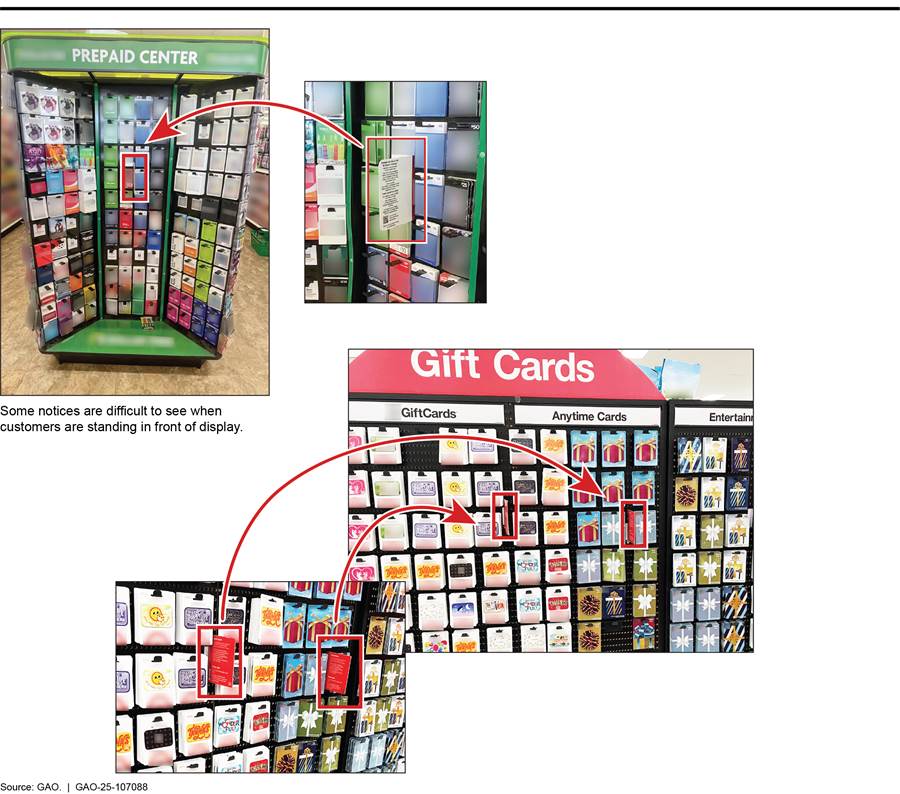

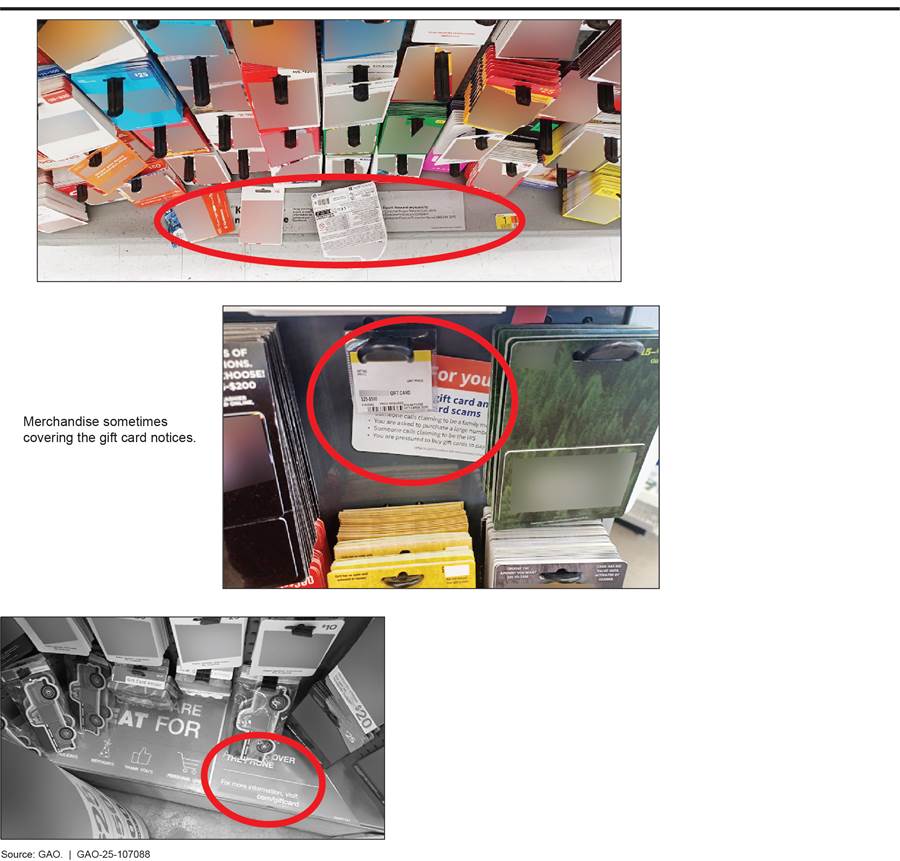

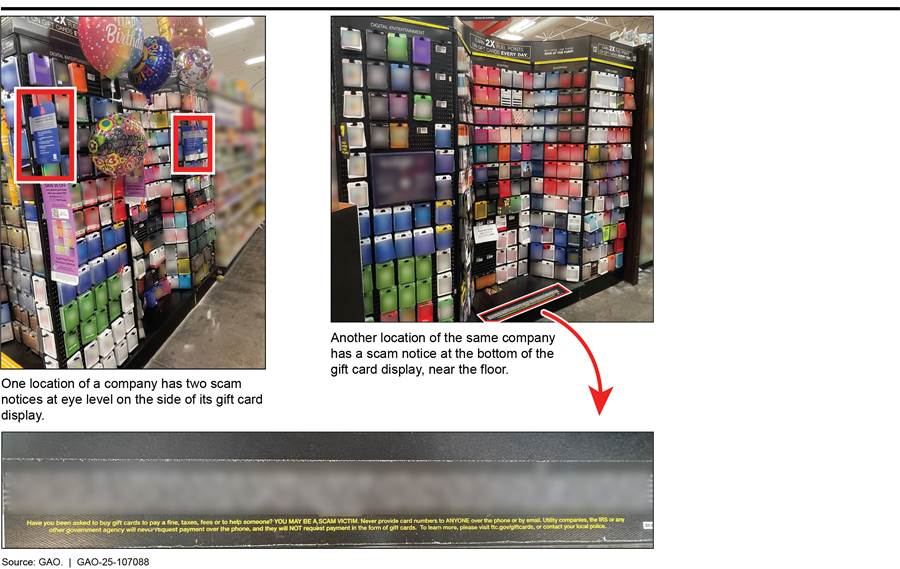

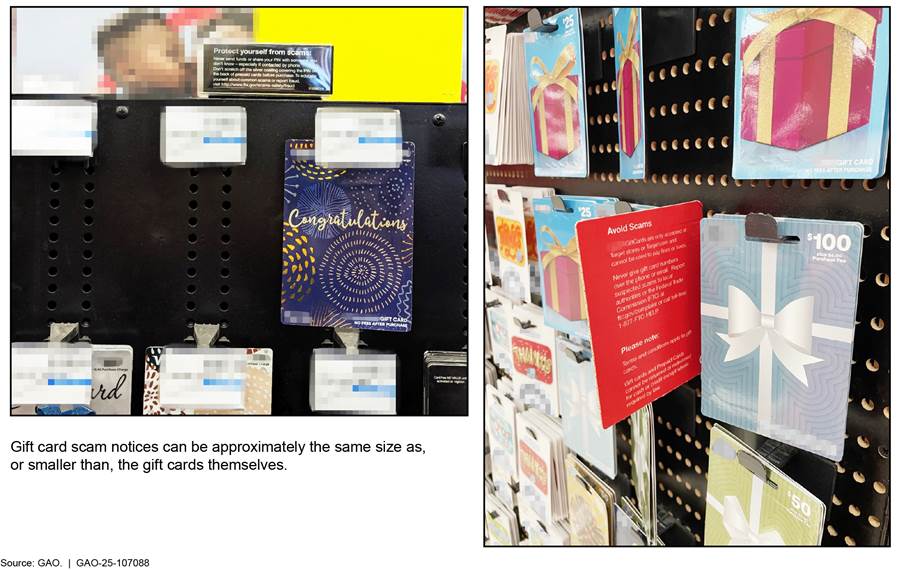

As part of this objective, we selected and visited, unannounced, a nongeneralizable sample of 68 locations of eight different gift card retailers across eight states and the District of Columbia to observe gift card scam warning signs that may be voluntarily posted at gift card displays.[11] These retailers included grocery stores, hardware stores, department stores, and pharmacies. The results of our site visits are specific to the retailer location visited and cannot be projected to all gift card retailers.

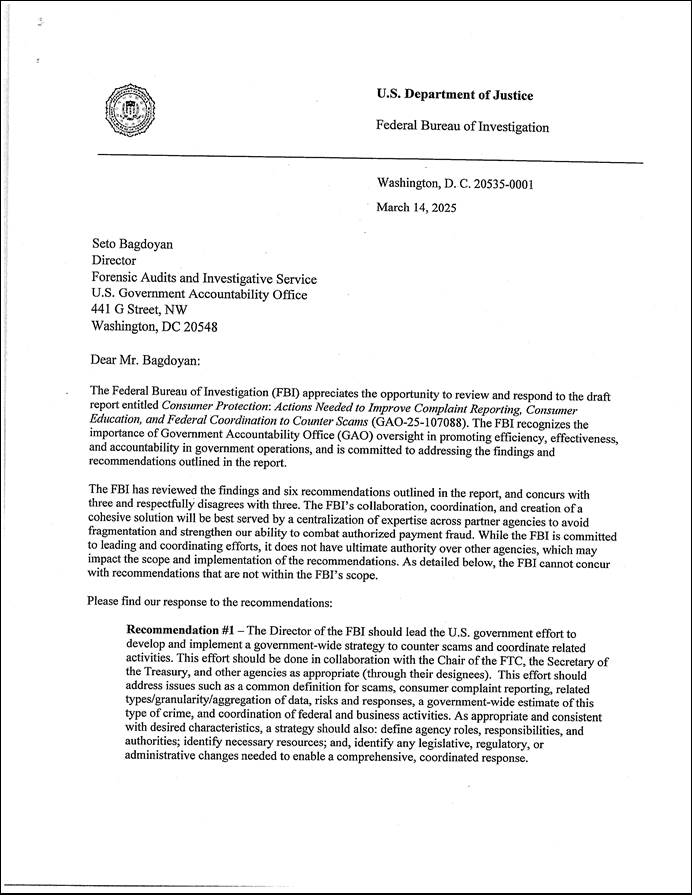

To describe actions taken by federal agencies and selected businesses to respond to consumer complaints related to scams, we interviewed officials from CFPB, FBI, and FTC. We focused on these agencies because they receive complaints directly from consumers and produce reports based on these data. We also interviewed the seven selected businesses about their actions to respond to consumer complaints.

We conducted covert scenarios to obtain information on the experiences of consumers of varying demographics, including older adults, who report scams to selected federal agencies and businesses.[12] As part of implementing our covert scenarios, we filed complaints to agencies and businesses stating that we were deceived into making a payment as part of a scam. We executed different scenarios where we were the victims of different types of scams, such as government impersonation and investment scams, among others. We also selected a nongeneralizable sample of P2P payment apps, gift card issuing companies, and MSBs as scam payment methods used for our covert scenarios. We submitted consumer complaints to CFPB, FBI, and FTC, as well as to a nongeneralizable selection of four gift card issuers and a nonbank wire transfer company.[13] We did this to determine what initial action the agencies and selected businesses take when an individual informs them that they have been the victim of a scam.[14] The results of our covert scenarios are for illustrative purposes and cannot be projected to the outcomes of other consumer complaints or responses by agencies and entities.

See appendix I for a detailed description of our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We conducted our related investigative work in accordance with standards prescribed by the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency.

Background

Characteristics of Scams, Victims, and Scammers

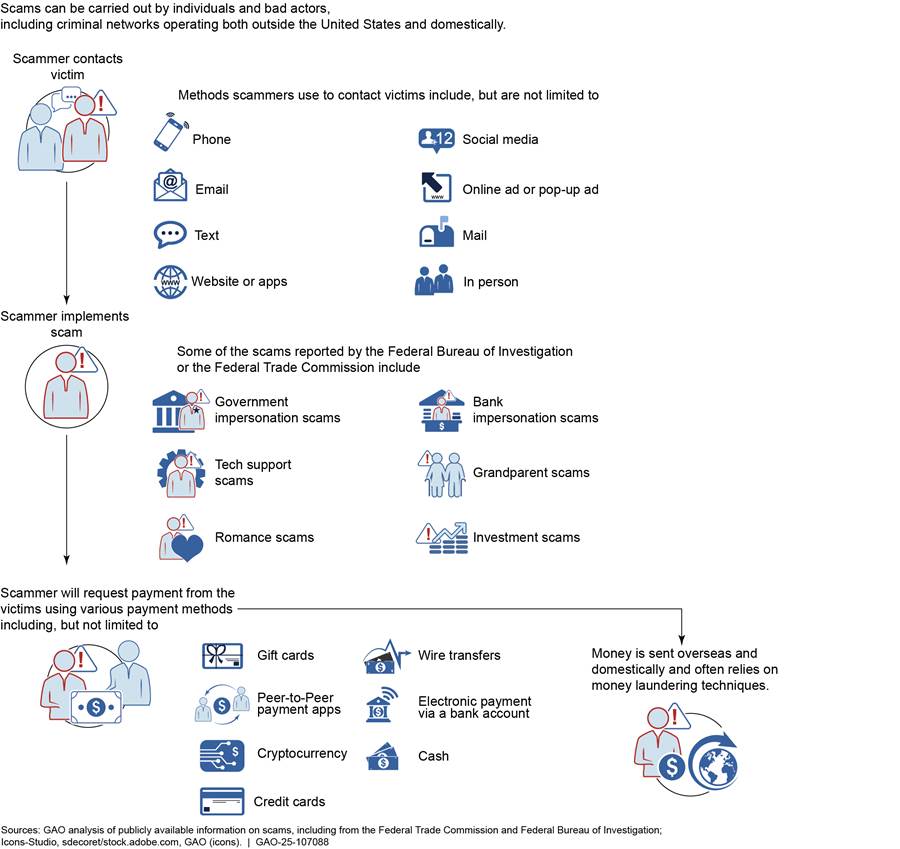

Scams involving the use of information technology have been around for decades. In an early common scheme, text messages were sent to consumers requesting that funds be sent to someone purporting to be a family member. By 2008, tech support scams, as discussed below, began to appear and have proliferated since that time. According to our analysis of publicly available information, scams currently occur in a wide variety of forms. In many instances, scams involve a scammer contacting the victim, through means such as text message or social media; engaging the victim with a particular scam; and requesting a payment, such as a wire transfer, for a false purpose. Figure 1 illustrates how many scams may be conducted.

Victim information. Scammers may obtain victim information, including their name and address, through various sources. These include fake solicitations to the victim via autodialing software (robocalls and robotexts), data breaches, marketing lead lists, social media, open-source information, and information-sharing by scamming networks.[15] In some cases, the scam may seem more believable because the scammer already has some of the victim’s personal information.

A 2024 DOJ study found there was no statistically significant difference between the percentage of persons aged 60 or older and persons aged 59 or younger who experienced fraud in 2017.[16] However, older adults are more likely to experience greater losses and are less likely to report scams. According to FTC, older adults, or persons aged 60 and older are less likely to report losing money to fraud compared with younger adults aged 18 to 59. FTC’s most recent fraud survey, published in October 2019, also found that what it called the “rate of victimization” for the various categories of frauds included in the survey was generally lower for those 65 and older than for younger consumers. However, older adults report greater individual median losses than younger adults.[17] As discussed later in this report, in response to laws enacted by Congress, FTC has initiatives designed specifically to help older adults avoid scams. Additional resources or specialized personnel are sometimes employed by agencies or businesses to respond to older victims, but the resolution process generally remains the same as for other victims.[18]

Contact methods. Depending on the type of scam, the contact method may include phone calls, social media, in-person, email, or text. When phone calls are used, scammers may spoof caller identification information to hide their identity. Specifically, a consumer’s caller identification may incorrectly indicate a call is coming from a government agency or other legitimate entity.

Scam implementation. Scammers may use a script to appear legitimate and create a sense of urgency to pressure or scare individuals into sending money immediately. Alternatively, some scams, such as romance scams, can take months to build a trusting relationship before the scammer asks for money.

In July 2024, we reported on fraudulently induced payments.[19] We noted that the use of artificial intelligence and deepfake technology lend credibility to scams by enabling criminals to hide their identities, and we described how some scammers use artificial intelligence to make scams harder for the victims to detect. This technology can be exploited by scammers to alter voices, images, and video to impersonate family, friends, or business officials.

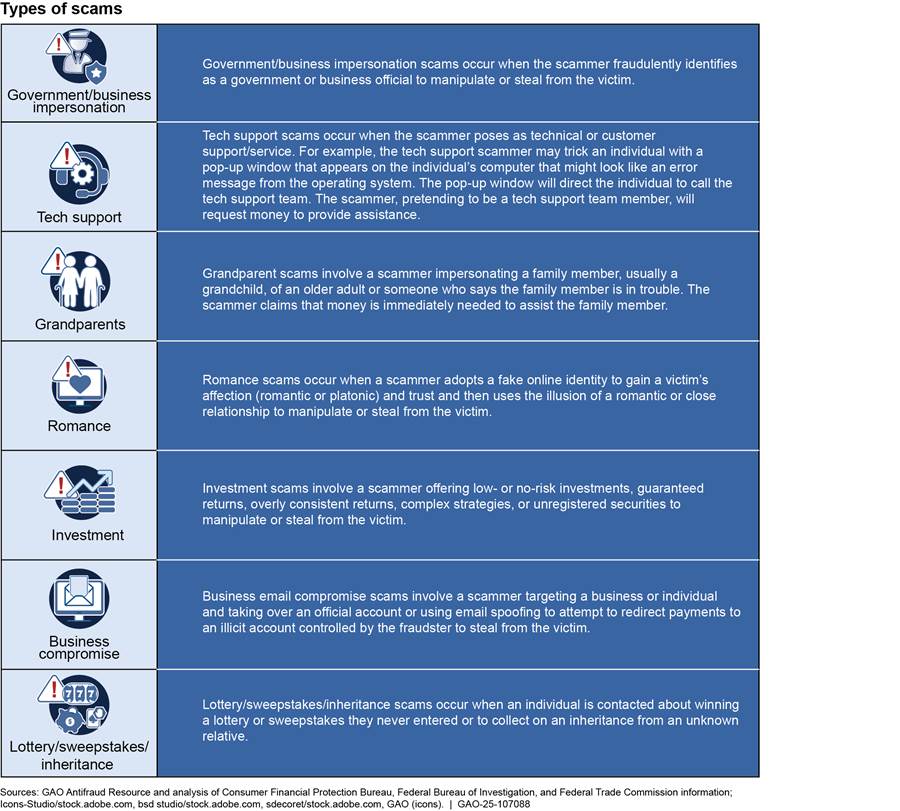

Scam types. Scammers are constantly finding new ways to scam victims. CFPB, FBI, and FTC have identified numerous types of scams. Figure 2 provides a nonexhaustive listing of scam types.

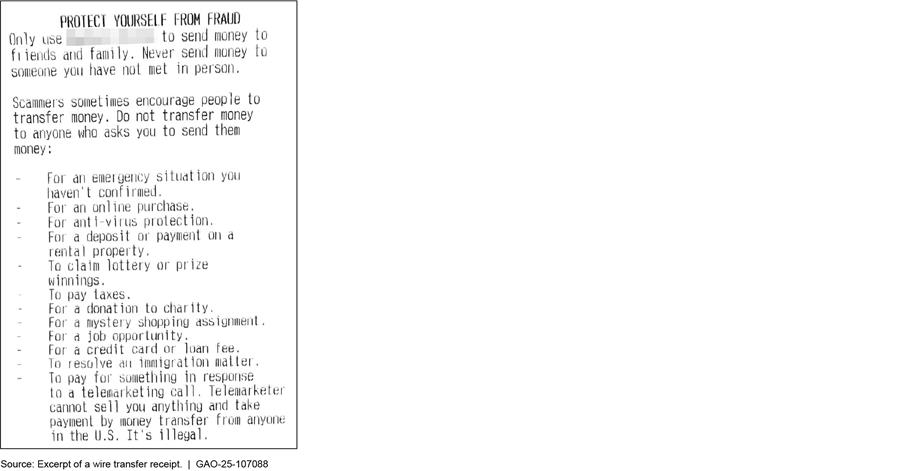

Payment methods. The scammer may obtain funds from the victim by requesting payment through methods such as P2P payment apps; electronic payment via a bank account, wire transfer, check, cash, cryptocurrency, precious metals; or providing gift card numbers and Personal Identification Numbers (PIN).[20] Below are characteristics of some frequently used payment methods employed by scammers to obtain funds from victims, as cited by FTC reports.

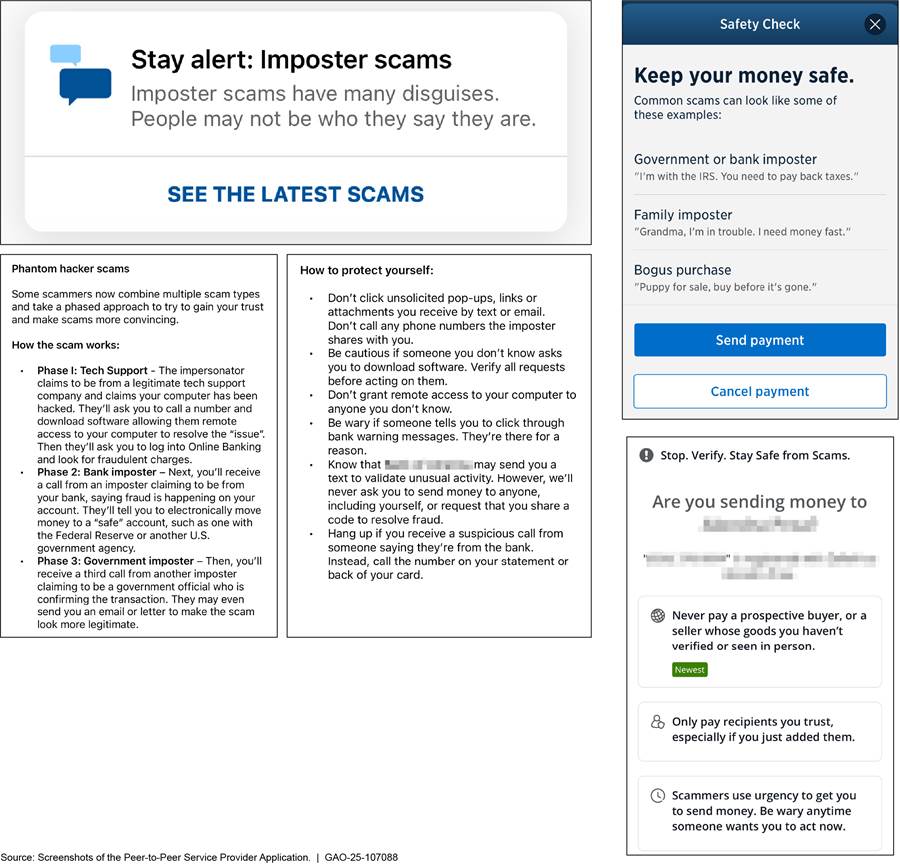

· P2P payment apps allow consumers to quickly send and receive money. Depending on the payment provider, a P2P payment can be initiated from a consumer’s online bank account portal, or a mobile app. According to FTC, scammers rely on P2P payment apps because transfers happen quickly and, once the individual sends the money, it is difficult to get it back.

· Gift cards hold specific cash value that can be used for payments for goods and services. Scammers can request that individuals purchase a gift card and ask for the gift card number and PIN. Scammers deceive their victims by telling them, for example, that the gift card number is to pay the government for taxes or fines, pay for tech support, or for some other fictitious reason. The gift card number and PIN allow the scammers to access the funds that their victim has loaded onto the card.

· A wire transfer occurs where, typically, funds are sent electronically from one person or entity to another. A wire transfer can be initiated through a financial institution or through a nonfinancial institution provider, such as an MSB. The transfer can be domestic or international.

In our July 2024 report, we discussed how fraudulently induced payments occur when a person with payment authority is manipulated or deceived into making a payment for the benefit of the scammer.[21] We found that financial institutions are generally not required under federal law to reimburse consumers for losses stemming from a fraudulently induced payment because the payment was authorized by a person with payment authority on the account (i.e., the owner of the account or other authorized person). Financial institutions and P2P payment companies provide consumer education and staff training to help identify and avoid potential scams. Additionally, some institutions and payment apps have put in place measures to slow down payments to provide the consumer an opportunity to verify the legitimacy of the payment. Industry representatives we interviewed for our 2024 report recommended a multisector approach, to include telecommunications and social media companies, as well as law enforcement, to address fraudulently induced payments.

Scammers. Scams can be carried out by individuals and bad actors, including criminal networks operating both outside the United States and domestically. Multiple domestic law enforcement investigations have identified criminals operating from international call centers working to scam Americans. For example, scammers in foreign-based call centers have called Americans and falsely identified themselves as federal law enforcement officers or other government officials to request that victims send money to avoid arrest or other economic consequences. The funds that criminals obtain from these scams may be linked to other illicit activities, such as human trafficking and drug trafficking.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, transnational organized crime groups have built large organizations to perpetrate sophisticated scams.[22] Specifically, transnational criminals have trafficked hundreds of thousands of victims and forced many of them to work in “scam compounds” and conduct scams through the internet. These criminals also conduct mass recruitment of professionals with information technology expertise and pay them a salary. Some of the scam operations have developed training manuals and scripts that individuals are made to follow to commit the scams, according to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner.[23]

Consumer Complaints About Scams

Multiple federal agencies receive complaints, some of which involve scams, directly from consumers. Different agencies may have authority over different matters impacting the public. Federal agencies receive complaints through their websites and may also receive complaints through phone, fax, or mail.

We identified eight federal agencies (of the 13 total agencies in our review) that receive complaints from consumers about scams:[24]

· CFPB. Receives consumer complaints about financial products or services, including money transfers, cryptocurrency, and prepaid cards. The CFPB complaint process is discussed in greater detail later in the report.

· FBI. Within FBI, the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) receives consumer complaints related to internet crime, including identity theft, data breaches, and scams.[25] FBI officials told us that in addition to submitting complaints to IC3, consumers can file complaints to FBI field offices. The IC3 complaint process is discussed in greater detail later in the report.

· Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Receives consumer complaints about financial institutions that it regulates. Consumer complaints made to the agency could include issues related to scams. Consumers can provide information on the specific financial institution where the victim’s money is held and a narrative with additional information.

· Federal Reserve. Receives complaints about financial institutions and forwards them to the appropriate federal regulator or to the appropriate Reserve Bank.[26] Federal Reserve officials stated that consumers can submit complaints about scams involving financial institutions where the victim’s money is held. According to the Federal Reserve, internet fraud complaints are referred to IC3, consumer fraud complaints are referred to FTC, and mail fraud complaints are referred to the U.S. Postal Inspection Service.[27]

· FTC. Receives consumer complaints about fraud or scams, and bad business practices, including those in the financial services area.[28] FTC receives reports directly from the public via its website and through its call center and from various contributors. Its consumer complaint process is discussed in greater detail later in the report.

· Homeland Security Investigations (HSI). Receives tips from the public through a hotline. Officials stated that tips are sent to specific Department of Homeland Security units based on the nature of the tip or the information provided. The tip hotline allows individuals to report information on any of HSI’s investigative areas, such as financial crime, cybercrime, human trafficking, and narcotics smuggling, and is not specific to scams. In addition, tips and complaints can be reported to local HSI Field Offices. HSI works with task forces, which consist of state, local, federal, and private sector partners in identifying and combatting fraud.

· Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). Receives consumer complaints about financial institutions that it regulates. According to OCC officials, complaints made to the agency could include issues related to scams involving financial institutions where the victim’s money is held. Consumers can provide information on a specific financial institution that is the subject of the complaint and a narrative with additional information. OCC stated that the agency is unable to process complaints where the complainant is not a customer of the financial institution that is the subject of the complaint.

· Secret Service. Individuals can report crimes to a local Secret Service field office. However, Secret Service officials told us they do not have a formal system in place to specifically receive scam complaints like FBI and FTC. The Secret Service’s investigative areas include financial crimes, cybercrimes, and counterfeit currency investigations and are not specific to scams. The Secret Service has field office-based Cyber Fraud Task Forces, whose mission is to prevent, detect, and mitigate cyber-enabled financial crimes. According to the Secret Service, these task forces work with state and local law enforcement agencies and financial institutions to combat cybercrime and scams.

When receiving complaints, federal agencies may refer consumers to state and local agencies and businesses.[29] For example, according to FTC, it advises most consumers reporting financial losses to report the problem to the company operating the payment system involved so that the consumer can get a refund, if possible, and to make sure the company knows about the fraudulent transaction on its system and can act accordingly. In addition, according to FTC, depending on the type of report, it may also tell consumers they can contact their state attorney general or local consumer protection agency. Other agencies that take consumer complaints may refer these complaints to one of the eight agencies above.

In addition to filing complaints with federal agencies, older adults can receive assistance reporting scams and other financial crimes from DOJ’s National Elder Fraud Hotline. Further, individuals can report scams to nonprofit consumer organizations, such as AARP and the Better Business Bureau (BBB), that may share information with federal agencies.

Multiple Agencies Engage in Activities to Counter Scams, but No Comprehensive, Government-wide Strategy Guides Their Efforts

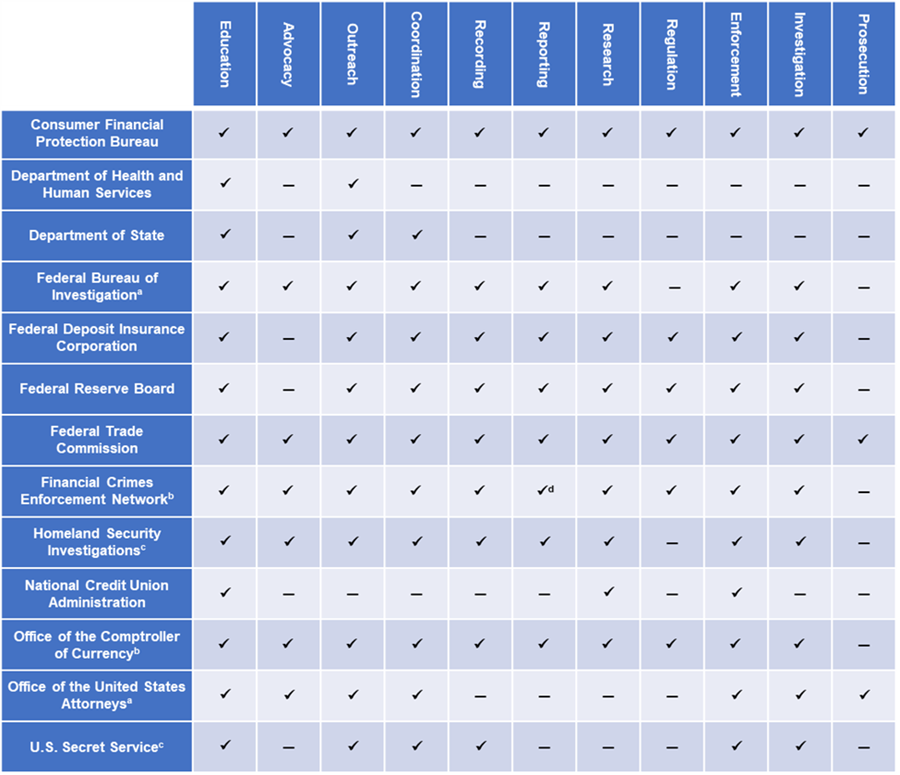

At least 13 federal agencies engage in a range of activities related to countering scams perpetrated against victims. In this regard, each agency has its own mandate and authority, with each largely pursuing independent activities related to countering scams.

Several agencies formally and informally coordinate their efforts with other agencies and consumer and other associations, including when providing consumer education or by sharing consumer-complaint information. However, these efforts are not coordinated across all the agencies we identified on a formal, government-wide basis. Further, there is no single, comprehensive, government-wide strategy for guiding efforts to counter scams.

Selected federal agencies and industry groups offered their views about the need for such a strategy, while some foreign countries, such as the United Kingdom, have developed and implemented strategies to counter scams. The absence of a comprehensive, government-wide strategy poses a risk for potential fragmentation of effort among agencies and overlap of their activities to counter scams, which risks diminishing their efficiency and effectiveness.

Multiple Agencies Engage in Activities to Prevent and Respond to Scams

Officials from the 13 federal agencies we spoke with indicated they were engaged in a range of activities related to countering scams. These activities cover a spectrum of roles intended to prevent, detect, and respond to scams.

We asked officials from these agencies whether their agency engaged in any of 11 different activities specifically related to countering scams. Each agency stated they engaged in some form of preventative activities, such as consumer education or outreach (for example, publishing consumer alerts and articles related to fraud and scams). About half of the agencies stated they engaged in information-gathering activities, such as recording or reporting on scam complaints. Similarly, most of the agencies stated that they take some form of action to respond to or investigate scams. Investigation activities range from reviewing consumer complaints to supporting legal action by the agency to assisting other law enforcement entities with information gathering and research. Figure 3 below shows the activities agencies told us they take to counter scams.

Legend: ü = Yes; — = No

Source: GAO compilation and analysis of agency interview responses. │ GAO‑25‑107088

Note: Activity definitions

Education: Agency provides education materials or programing regarding scams to consumers and businesses.

Advocacy: Agency provides information to policymakers or performs advocacy in policy areas affected by scams.

Outreach: Agency conducts outreach or distributes notifications regarding scams to consumers and businesses (e.g., warnings/advisories).

Coordination: Agency collaborates with other agencies to address scam issues.

Recording: Agency receives and records complaints regarding scams.

Reporting: Agency regularly collects and reports on scams or provides statistics for related issues/scams.

Research: Agency conducts research and produces reports regarding scams.

Regulation: Agency promulgates regulations that affect scam issues.

Enforcement: Agency enforces laws or regulations that affect scam issues.

Investigation: Agency leads, or assists with, the investigations of complaints/scams.

Prosecution: Agency undertakes criminal or civil prosecutions of scams.

aComponent of the Department of Justice

bComponent of the Department of the Treasury

cComponent of the Department of Homeland Security

dAccording to Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) officials, the agency does not receive scam complaints directly from consumers. Rather, FinCEN receives Suspicious Activity Reports from financial institutions that might signal criminal activity, which could include scams.

Some Agencies Coordinate Activities to Counter Scams

Although at least 13 federal agencies engage in activities related to countering scams perpetrated against victims, each agency has its own mandate and authority, with each largely carrying out activities related to countering scams independently. However, in some instances, agencies coordinate efforts, such as by providing consumer education or by sharing consumer complaint information. Some of these efforts are implemented through official bodies intended to address crimes against older adults.

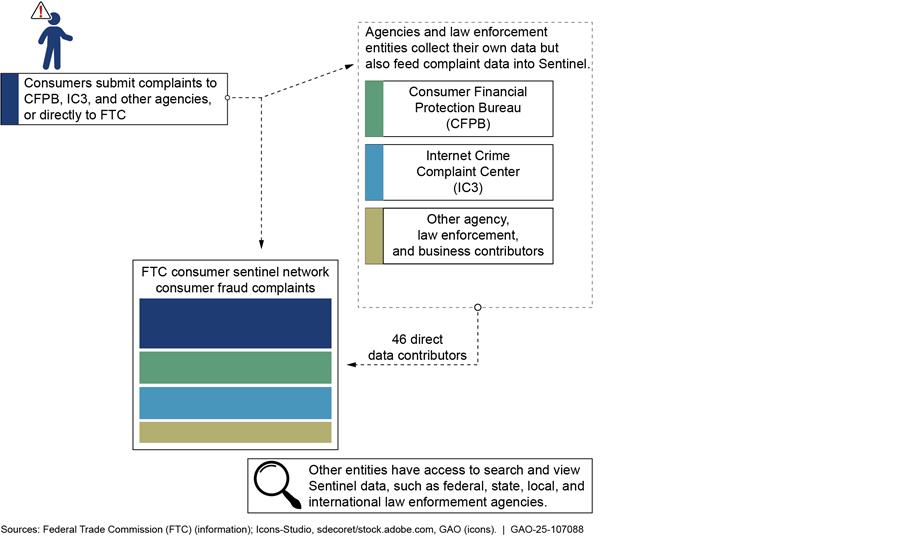

In an example of coordination, FTC maintains the Consumer Sentinel Network (Sentinel). Sentinel, a collaborative effort involving 46 contributors including FBI, is a consumer-complaint reporting database made accessible to law enforcement agencies. (We discuss Sentinel later in this report.) Similarly, Treasury’s FinCEN supports law enforcement investigations by providing financial intelligence and, at times, investigation support. CFPB officials noted that some federal agencies engage in informal discussions and complaint sharing to monitor and identify emerging trends and issues.

Legislation has been enacted to improve formal coordination in countering scams. Specifically, in 2022, Congress enacted the Stop Senior Scams Act, requiring the establishment of an older-adult scam prevention advisory group. The group consists of representatives from across federal government and law enforcement agencies; consumer advocacy organizations; and the gift card, MSB, retail, and telecommunications industries, among others.[30] With a focus on older adults, the advisory group is to collect information on materials that industry uses to educate employees on identifying and stopping scams. The group is then to identify any inadequacies or deficiencies with those materials and create models, best practices, or guidance documents to help address deficiencies.

In response to the Stop Senior Scams Act, in 2022, FTC established the Scams Against Older Adults Advisory Group. The advisory group focused on four main areas, and each area was led by a separate committee: (1) expanding consumer education and outreach efforts, (2) improving industry training on scam prevention, (3) identifying innovative or high-tech methods to detect and stop scams, and (4) reviewing research related to scam prevention messaging and making recommendations for future research.

Since its establishment, the full Scams Against Older Adults Advisory Group held two meetings, one in September 2022 and a second in April 2024. According to FTC, the committees met regularly from December 2022 to early 2025. They also issued deliverables, such as (1) a reference sheet on principles to better reach people with messages that help them spot and avoid fraud; (2) a document outlining principles for effective industry training on scam prevention; (3) a report summarizing what research has shown to be effective in scam prevention messaging, challenges to that messaging, and where additional research is needed; and (4) a document identifying state laws that allow banks or brokerages to hold or freeze a transaction when fraud is suspected, which may help prevent a scammer from obtaining consumer funds.[31]

Further, according to FTC officials, other multiagency government-wide initiatives exist to address insidious and pervasive scams. Specifically, FTC participates in government-wide collaboration to address fraud, including through the Global Anti-Fraud Enforcement Network, the Elder Justice Coordinating Council, and the COVID-19 Fraud Enforcement Task Force.[32]

According to FBI, it counters scams through coordinated activity with foreign, federal, state, and local law enforcement through joint investigations, tasks forces, and the public and private sectors through working groups. FBI officials noted that there are initiatives to counter elder abuse, neglect, and financial exploitation, including scams, and that scams are being investigated by other federal agencies, such as HSI. The initiatives to counter elder fraud, including scams, include DOJ’s Elder Justice Initiative. This initiative is a program that works to counter elder abuse, neglect, and financial exploitation, including scams. Additionally, the DOJ Consumer Protection Branch leads a cross-agency domestic elder justice working group, and the Transnational Elder Fraud Strike Force investigates and prosecutes individuals and organizations engaging in foreign-based scams that disproportionately affect American seniors.[33] Further, FBI participates in international law enforcement working groups addressing scams. According to FBI, it has dedicated personnel in the identified epicenters of romance scams and confidence and tech support scams. These personnel lead coordination efforts with local law enforcement and specifically address elder fraud from abroad—intelligence collection, and coordinated operational activity to disrupt, dismantle, and deter the syndicates, and recover victim funds.

According to HSI, the agency is committed in the fight against fraud and has engaged in multi-initiative workforce groups in developing a national strategy. Along with FBI and other law enforcement partners, HSI works with private sector partners, such as financial institutions, and regulatory agencies, such as the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, international partners, and DOJ in combatting scams, to include romance scams, cryptocurrency scams, elder fraud, and other types of scams.

There Is No Comprehensive, Government-wide Strategy to Guide Agency Activities to Specifically Counter Scams

Officials with the 13 federal agencies we spoke to noted that they were not aware of a single, comprehensive, government-wide strategy to guide federal efforts to counter scams. Our own review of existing strategies did not identify any that are specifically focused on countering scams. A national strategy is a type of interagency coordination mechanism—typically, a document or initiative—that provides a broad framework for addressing issues that cut across federal agencies and other levels of government and sectors.[34] Three agencies and the White House have strategies that address various aspects of scams but do not provide government-wide direction.

We identified four strategies—developed by Treasury, FBI, FTC, and the White House—that focus on illicit financing, cyber-enabled fraud, unfair and deceptive acts or practices, and transnational organized crime, respectively. Our review of the four strategies found that, although each addresses activities related to scams, the strategies do not focus on scams. We also found that none of the strategies functions as a single, comprehensive, government-wide strategy to counter scams nor were any of them intended to.

· U.S. Department of the Treasury 2024 National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing. In 2024, the U.S. Department of the Treasury published a national strategy for countering terrorist and other illicit financing, which includes fraud. The strategy identifies efforts to strengthen tools and authorities against illicit finance and outlines specific actions some agencies will take to support these priorities.[35] Unlike the 2022 national strategy, the 2024 strategy explicitly identifies the misuse of money orders, prepaid cards, and P2P payments in its discussion of illicit finance vulnerabilities. However, it does not include a discussion of efforts to counter scams government-wide because the focus of the strategy is illicit financing in general.

· FBI cyber strategy. In September 2020, FBI published a 2-page cyber strategy that presents the agency’s cyber vision and mission to raise risk awareness and impose consequences on cyber adversaries through authorities, capabilities, and partnerships.[36] The cyber strategy does not discuss efforts to counter scams at a government-wide level. According to FBI officials, the agency’s Cyber Division focuses on criminal and nation-state cyber intrusions and also noted that scams were not included as cases to be addressed under the strategy.

According to FBI officials, the agency considers scams to be a financial crime; the primary responsibility for addressing this activity falls under the FBI Criminal Investigative Division, Financial Crimes Section (FCS). However, because scams are often cyber-enabled, crossover exists within the 2020 Cyber Strategy, specifically the descriptions of capabilities and partnerships. The strategy also highlights the asset recovery team, discussed later in this report, which can assist victims that meet certain criteria in recovering financial losses related to cybercrime, which may include scams. Further, the strategy states that no single agency or government can counter cyber threats alone.

· FTC Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years 2022-2026. FTC officials cited Goal 1 of its Strategic Plan for 2022-2026 as its strategy to counter scams.[37] Goal 1 addresses unfair and deceptive acts or practices, which include scams. Under Goal 1, the plan describes several objectives, including

· identifying, investigating, taking actions against, and deterring unfair or deceptive acts or practices that harm the public;

· connecting with individuals, communities, and businesses to provide practical knowledge, guidance, and tools and to learn about key challenges and opportunities for future FTC engagement; and

· collaborating with domestic and international partners to enhance consumer protection.

As described in the plan, FTC stated it provides access to analytical tools through Sentinel to enable law enforcement agencies to target investigations, identify witnesses, and uncover details about scam operations, such as payment methods, contact methods, and sales pitches. However, while the plan does specifically address efforts to counter scams, its focus is limited to the FTC’s efforts. As such, it does not serve as a single, comprehensive, government-wide strategy to counter scams.

· White House Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime. In December 2023, the White House released an update to its 2011 strategy to respond to the shifting strategic environment of transnational organized crime.[38] The strategy targets the dispersions of illicit finance pathways by encouraging law enforcement to increase its use of FinCEN reporting to inform investigations. Additionally, it seeks to counter cyber-enabled fraud capabilities by engaging with the private sector to craft educational messaging to counter fraud schemes. While this strategy has objectives related to elements of scams, the strategy focuses on organizations that engage in transnational crime, with the bulk of its strategic objectives addressing issues, such as intelligence sharing and border security, to counter other aspects of transnational organized crime.

In July 2024, FBI informed us that its FCS is developing a “cyber-enabled fraud strategy” to identify, target, and disrupt the most prolific transnational criminal enterprises defrauding U.S. citizens. FBI noted that the FCS has established resources to contribute to mitigating the cyber-enabled fraud threat across agencies and has working relationships with strategic partners to leverage the cyber-enabled fraud program, such as FinCEN, FTC, CFPB, and several DOJ components. FBI did not have a timeline for when the strategy will be finalized and implemented. Even when completed, the strategy may not serve as a comprehensive, government-wide strategy because, as an FBI-focused strategy, it may not address the roles, responsibilities, and authorities of other agencies or contain all the characteristics of a national strategy.

According to FBI, in December 2024, the FBI’s Criminal Investigative Division established the Cyber-Enabled Fraud & Money Laundering Unit to prioritize and resource FBI cyber-enabled fraud investigations. The Cyber-Enabled Fraud & Money Laundering Unit defines cyber-enabled fraud as traditional fraudulent activities that are facilitated or enhanced by digital technology, the internet, and electronic communications such as cryptocurrency scams, romance scams, tech fraud scams, and other scam typologies. The strategic goal of the Cyber-Enabled Fraud & Money Laundering Unit is to disrupt and dismantle cyber-enabled fraud actors and the ecosystem that supports them by leveraging strategic partnerships with the U.S. Intelligence Community, private sector, and international law enforcement. Public outreach and education are also part of the Cyber-Enabled Fraud & Money Laundering Unit strategy to counter the cyber-enabled fraud threat.

Selected Federal Agencies’ Perspectives on a Comprehensive, Government-wide Strategy to Counter Scams Differ

FTC and Treasury officials shared their view with us on a single,

comprehensive, government-wide strategy to counter scams.

· According to FTC officials, no single agency has the jurisdiction and authorities to tackle the diversity of fraud and scams in the marketplace government-wide. They stated that a government-wide strategy could help overcome those jurisdictional barriers, if significant resources could be applied to tackle multifaceted and evolving scams. FTC added that any comprehensive, government-wide strategy must include a focus on criminal and civil law enforcement.

· Treasury officials noted that many law enforcement and other agencies have overlapping mandates when it comes to fraud and scams, and a fully coordinated law enforcement strategy may in practice be difficult to coordinate and implement between agencies. Further, Treasury officials noted that to have a government-wide strategy to coordinate efforts to counter scams would involve several key agencies, such as CFPB, FBI, FTC, and Treasury.

We also asked CFPB and FBI for their views on a government-wide strategy to counter scams. Neither offered specific views on such a strategy. FBI officials, however, noted that cyber-enabled fraud is a worldwide problem warranting a unified, global response. FBI officials stated that FBI coordinates efforts and activities to counter scams affecting all consumers to the extent possible within available funding and resources. However, FBI officials recognized that there is no formalized mechanism to deconflict (i.e., coordinate between agencies in areas where overlapping investigations occur to avoid compromising those investigations), collaborate, coordinate, leverage assets, and share respective resources among investigations.[39]

Some Industry and Consumer Organizations Have Advocated for a Government-wide Strategy to Counter Scams

Some industry representatives and consumer organizations have advocated for a government-wide strategy to counter scams. For example:

· In its November 30, 2023, meeting, the Federal Advisory Council to the Federal Reserve Board stated in its minutes that a government-wide approach is needed to counter fraud and scams.[40]

· In testimony before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in May 2024, the American Bankers Association stated that a national antiscam strategy needs to be developed.[41] The association said that “fraud and scams are costing consumers billions of dollars each year and current federal activities are disjointed and uncoordinated with no overarching strategy.” The association further stated its belief that a “national anti-scam strategy is critically needed to develop and implement a coordinated federal approach focused on stopping consumers from being scammed in the first place and developing solutions to assist consumers once the scam has been perpetrated.” Further, the association said, “Focusing on only one aspect or one step in the [scam] process will not stop this surge of scams. Rather, a holistic approach to address all the entities and elements of a scam has the best chance of being successful.”

· An official from the Consumer Federation of America we spoke with stated that there is a need for a strategy to help develop a uniform term that defines scams, develop a single estimation of losses associated with scams, and coordinate efforts so federal agencies can work better together and with the banking industry.[42]

· Officials from one of the world’s largest financial institutions told us that a national antiscam strategy and a comprehensive federal government approach are needed to counter these criminals and the scams they perpetrate. This strategy requires a whole-of-government response that partners with financial institutions, telecommunications companies, and social media companies to protect consumers. Further, the officials stated that there is a need for a lead agency to help coordinate efforts and prevent fragmentation.

· The Retail Gift Card Association told us that it values and supports legislation that is focused on inter-agency strategies and data sharing in an effort to counter fraud, while ensuring that gift cards remain accessible, anonymous, and convenient to consumers.

· In July 2024, the Aspen Institute Financial Security Program launched the National Task Force for Fraud and Scam Prevention.[43] According to public information, the task force will bring together stakeholders from the government, law enforcement, and private industry to develop a nationwide strategy aimed at helping prevent fraud and scams. The task force plans to address different aspects of fraud and scams, with a primary focus on prevention. Some of the members that are part of the task force include BBB, American Bankers Association, FinCEN, FBI, FTC, Department of Homeland Security, and Secret Service, among other organizations.

Other Countries Have Developed Strategies and Identified Entities to Counter Scams

Other countries, such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and Singapore, have developed and implemented government-wide strategies and identified specific entities to counter scams, with attributable reductions in the level of scams.

Specifically, in May 2023, the United Kingdom government issued a fraud strategy that provides a plan for how government, law enforcement, regulators, industry, and charities will work together to counter scams.[44] The strategy states that scams continue to be the priority for the Financial Conduct Authority and that it will continue to proactively consider a range of potential policy initiatives to tackle the scale and impacts associated with this type of crime, both for victims and the firms that the authority regulates.[45] Since the launch of the fraud strategy, the United Kingdom saw a decrease of fraud of 13 percent in June 2023, 16 percent in December 2023, and 10 percent in March 2024 year-on-year. However, the United Kingdom saw an increase of fraud of 7 percent in June 2024 and a 19 percent increase of fraud in September 2024 year-on-year.[46]

Similarly, Australia created a National Anti-Scam Centre within its Competition and Consumer Commission that draws on expertise across government, law enforcement, industry, and consumer groups to make Australia a harder target for scammers.[47] Together, the entities collect and share scam data and intelligence, implement scam prevention and disruption initiatives, and provide better awareness alerts and education resources to help consumers identify and avoid scams. The National Anti-Scam Centre supports the work of those agencies. For example, the Anti-Scam Centre provides a central place for consumers to report scams, shares information about scams across the Australian government, and coordinates activities to stop scams.

The Australian government has reported that the National Anti-Scam Centre’s efforts have led to a 13.1 percent decline in reported scam losses from 2022 to 2023. The Australian National Anti-Scam Centre reported that overall scam losses in the fourth quarter of 2023 were down by 43 percent compared with the same quarter in the previous year. Further, in November 2023, the Australian government announced the proposed Scams Code Framework. The proposed framework would set clear roles and responsibilities for industry, with an initial focus on banks, telecommunications providers, and digital platforms, in an effort to fight against scams.

Singapore created the Anti-Scam Command to achieve greater synergy between various scam-fighting units within the Singapore Police Force by integrating scam investigation, incident response, intervention, and enforcement capabilities under a single umbrella.[48] In October 2023, Singapore published a proposal for a Shared Responsibility Framework for sharing responsibility for phishing scam losses among financial institutions, telecoms, and consumers.[49]

The Absence of a Comprehensive, Government-wide Strategy Poses Risk for Fragmentation of Effort and Overlap of Activities

As described earlier in this report, responsibility for countering scams is dispersed among at least 13 federal agencies. Our prior work has shown that in some instances, it may be appropriate or beneficial for multiple agencies to be involved in the same programmatic or policy area due to the complex nature of the issue or magnitude of the federal effort.[50] In other instances, in a situation such as countering scams, having multiple agencies involved in the same programmatic area could create the risk of fragmentation of effort or overlap of multiple activities (such as those described in this report)—especially absent a strategy to coordinate and manage such activities—potentially limiting their effectiveness and impact.[51]

In this regard, the varied aspects of scams, and responses to them, cross the jurisdictions of multiple agencies. Consequently, no one agency can counter the problem alone, and no agency is mandated or required to do so, either individually or collectively.[52] As a result, and absent formal guidance or directive, no agency has taken the lead to explore the need for and develop a comprehensive, government-wide strategy to help guide the various activities agencies employ to counter scams and mitigate the risk for potential fragmentation and overlap.

We have reported that strategies to coordinate programs that address crosscutting issues of broad national need can help identify and mitigate negative effects associated with fragmented, overlapping, and potentially duplicative federal programs.[53] While interagency coordination can help agencies and those they support, broad and challenging goals—in this instance, countering scams—may require a national strategy.

Our prior work has identified desirable characteristics of national strategies, including clear organizational roles, goals, objectives, and performance measures to gauge and monitor results. Defining organizational roles involves identifying entities—for example, specific federal agencies and offices and any other sectors, such as states and private industry—and their respective responsibilities. Goals address what the strategy is trying to achieve, objectives help lay out the steps needed to achieve those results, and performance measures provide accountability for achieving results. Additionally, a strategy should identify necessary resources and any legislative, regulatory, or administrative changes to assist with implementation of the strategy. Further, strategies are most effective when they are regularly updated and monitored.[54]

A single, comprehensive, government-wide strategy to combat scams would facilitate the alignment and coordination of the range of federal agency activities to counter scams and help prevent consumers from becoming victims. In this regard, as discussed earlier, the implementation of similar strategies in the United Kingdom and Australia illustrates their potential impact. Namely, according to these governments, their strategies have helped reduce fraud and scam losses. Some industry and agency officials pointed out that a national strategy to combat scams would be foundational to developing and implementing a coordinated federal approach because no single agency has the jurisdiction, authorities, and resources to tackle the diversity of fraud and scams. A government-wide strategy could help overcome those jurisdictional barriers.

Assigning a federal agency to lead the development of a government-wide strategy to organize and prioritize combating scam efforts could help ensure that related activities are not duplicative or fragmented, do not unnecessarily overlap, and have a greater impact. According to FBI, it is best positioned to lead efforts to mitigate scams due to its expertise regarding cyber-enabled fraud and the collaborative capabilities of its FCS with stakeholders internal and external to FBI.

According to FBI, the FCS has established resources to immediately contribute to mitigating scam threats across agencies via financial crime response and support teams, relationships with national commissions and networks that counter financial and cyber-crimes networks, and dedicated legal attachés located abroad. The FCS also can leverage strong working relationships with strategic partners combating scams, such as other DOJ components, IC3, FinCEN, CFPB, and FTC.

As previously discussed, FBI/FCS is developing a cyber-enabled fraud strategy to identify, target, and disrupt prolific transnational criminal enterprises defrauding Americans. The overlap in issues relating to scams and cyber-enabled fraud could provide FBI/FCS with the expertise to develop a comprehensive, government-wide strategy for the federal government that includes clear organizational roles, goals, objectives, and performance measures across federal agencies to gauge and monitor results. A comprehensive, government-wide strategy could help facilitate and target efforts to combat scams and help prevent consumers from becoming victims.

Federal Agencies Compile Scam-Related Complaint Data, but Limitations Exist in Estimating the Extent of Scams and Related Financial Losses

CFPB, FBI, and FTC collect and report on consumer complaints both directly and, in some cases, from other agencies, as discussed below. Data limitations prevent agencies from determining the exact number of all scam complaints and dollar losses. CFPB, FBI, and FTC can provide limited estimates of the number of complaints and related dollar losses specifically related to scams. Additionally, there is no single, government-wide estimate of the total number of scams and dollar losses that factors in unreported incidents. Similarly, federal agencies have not produced a common, government-wide term for, or definition of, scams.

Agencies Collect and Report on Consumer Complaints, but the Data Collected Have Limitations

Of the eight federal agencies that receive scam-related consumer complaints, three agencies (CFPB, FBI, and FTC) publish annual reports summarizing consumer complaint data. However, the data these reports are based on have limitations.

CFPB

Complaint Collection

When consumers submit complaints to CFPB, they are asked to select one of 11 consumer financial products or services (such as credit reporting, credit card, or prepaid card) with which they have a problem, the issue that best describes the problem, and the company to which they want to direct their complaint. Consumers can further select from a list of issue categories, such as “Fraud or Scam.” The categories vary, depending on the consumer financial product or service selected. Consumers can describe the details of their complaint and their desired resolution, using open narrative fields. Consumers are instructed to describe what happened and to include dates, amounts, and actions taken by the consumer or the company.

CFPB sends the consumer complaints it receives to companies named by complainants for review and response. It also uses information from consumer complaints and company responses to monitor risk in financial markets, assess risk at companies, and prioritize agency action.

Complaint Reporting

CFPB publishes annual reports that include information on the number of consumer complaints it received, by financial product or service. These reports also detail the percentage of complaints that were closed with and without monetary relief from the companies subject to the complaints. These reports do not state the financial loss amount reported by consumers or the total number of complaints and associated dollar losses that were only related to scams.

Data Limitations

The way CFPB complaint data are collected limits their utility in reporting an aggregate count of the total number of complaints CFPB received related to scams. Specifically, if consumers submit complaints under the “Fraud or Scam” issue category, no further categories are available to select, for example, whether a complaint was about a specific scam, such as romance or tech support.

Additionally, consumers do not always have the “Fraud or Scam” option available to select. Specifically, CFPB does not have a predetermined data field that allows consumers to select a scam type, such as impersonation scam, for every financial product or service that consumers can submit a complaint about. For example, an impersonation-related data field is available for consumers who submit a complaint specifically about telecommunications debt (a debt collector trying to collect for a telecom bill, such as an internet, cable, or phone bill) but not for other categories, such as credit card debt and complaints about a checking or savings account. CFPB also does not request dollar loss amounts from consumers in a predefined field. CFPB officials stated that the agency uses narrative information entered by consumers to determine whether a complaint was specifically related to a scam, to the extent such information is provided, and analyzes narrative information as part of its ongoing monitoring activities.

According to CFPB, the agency’s complaint function is designed to collect complaints regarding consumer financial products and services. CFPB officials stated that due to variability and the evolution of market and related issues, the agency provides an open narrative field so that consumers can explain the issue in their own words. They noted that the complaint function was intentionally designed to not duplicate the FTC’s fraud reporting website.

According to CFPB officials, a change to the CFPB complaint form to permit consumers to identify a specific type of fraud or scam would require significant system, reporting, and data publication and sharing changes, among other things. Additionally, such a change would require CFPB to conduct a feasibility assessment to evaluate proposed changes and conduct user testing to ensure that any changes capture the information sought and are clear to complainants and that issues or biases are identified prior to implementation.

The FBI’s IC3

Complaint Collection

All complainants to IC3 are requested to provide name and contact information and details of the transaction they are submitting a complaint about. Consumers are specifically requested to provide information on any financial loss, payment method used, and recipient of any funds in separate data fields. Consumers can describe additional details about their complaint, using an open narrative field, and are instructed to provide a description of the incident and how the consumer was victimized. Instructions for the narrative field inform consumers to provide information not captured elsewhere on the complaint form.

Consumer complaints received by IC3 are analyzed and disseminated to federal, state, local, or international law enforcement or regulatory agencies for public awareness and criminal, civil, or administrative action, as appropriate.

Complaint Reporting

IC3 publishes annual internet crime reports that provide consumer complaint statistics. The reports state the total number of internet crime complaints and reported associated losses made by consumers to IC3. In 2023, IC3 reported approximately 880,000 internet crime complaints and $12.5 billion in associated potential losses. The reports also include the number of complaints and reported associated dollar losses related to some specific scams taken from consumer complaint narratives. For example, these reports categorize complaints by crime type that include scam-related crimes (such as government impersonation) and non-scam-related crimes (such as harassment and stalking). These reports do not include a single total of the number of complaints and associated dollar losses that were only related to scams.

IC3 also issues an annual report on fraud affecting older adults that provides information on scam complaints submitted by consumers who indicated in their complaints that they were at least 60 years old. DOJ officials acknowledged that these reports also do not include a total of the number of complaints and associated dollar losses that were only related to scams.

Data Limitations

The way IC3 complaint data are collected limits their utility in reporting an aggregate count of the total number of complaints related to scams. IC3 does not collect information from consumers about scams in predefined fields. Specifically, FBI does not provide fraud or scam subcategories, such as imposter scams, that consumers can select from when making complaints. Because IC3 does not request information from consumers about the type of internet crime they encountered in a predetermined data field, it relies on consumers to include this information in an open narrative field. According to FBI officials, analysts review IC3 complaints to determine the crime type and actual dollar losses based on the information provided by the consumer.

FBI officials explained that IC3 had previously provided consumers an opportunity to select the specific type of internet crime they were reporting. At that time, officials stated that consumers predominantly selected an incorrect crime type, which could result in complaints being forwarded to the wrong place for investigation. FBI officials stated that programming could be implemented to add a scam-type data field in the complaint form, but the scope of the addition would be driven by time and cost factors, and an analyst review would still be required to ensure the validity of the provided information.

FTC

Complaint Collection

When consumers submit complaints to FTC, they are asked to select from a list of fraud schemes and other consumer issues. Consumers are specifically requested to provide information on any financial loss and payment method used and how they were contacted, in separate data fields. Consumers can also choose to provide information about their age by selecting an age range. Consumers can describe additional details about their complaint, using an open narrative field, and are instructed to state what happened in the consumer’s own words with specific details they remember.

The agency’s Sentinel database also receives consumer complaints directly from its 46 data contributors that include federal and state agencies; private companies; and nonprofit organizations, such as the BBB.[55] According to FTC, over 50 additional entities, including government and business, inform consumers that they can file complaints through the FTC’s website. Three of the eight federal agencies we identified that receive consumer scam complaints—FTC, CFPB, and FBI—contribute complaint reports to Sentinel.[56] According to FTC, for complaints classified as fraud, the largest Sentinel contributors in calendar year 2024 were FTC, BBB, and FBI, which together made up over 75 percent of complaints received.[57]

FTC uses consumer complaints for investigations in connection with law enforcement efforts, to spot trends on the issues consumers are reporting, and to educate the public. According to FTC officials, these data are also used for other initiatives, including workshops in which developing issues are addressed. FTC provides access to consumer complaint information to members of law enforcement organizations that have entered into a confidentiality and data security agreement with the agency. Figure 4 below shows how consumer complaints are maintained by FTC and subsequently made available to Sentinel members.

Complaint Reporting

FTC publishes annual reports detailing consumer complaint data maintained in Sentinel. These reports include the total annual number of complaints and dollar losses in Sentinel involving fraud including, but not limited to, scams. In 2024, Sentinel received 2.6 million consumer fraud complaints and overall fraud losses of over $12.5 billion.[58] The reports categorize fraud complaint information by schemes that include types of scams, such as imposter scams. The reports do not state a single total of the number of complaints and associated dollar losses that are specific to scams. FTC officials stated that in general, they could not quantify the number of all scam complaints because the agency’s complaint form does not specifically ask consumers if they were scam victims.

Data Limitations

The entities that contribute to Sentinel do not always request fully consistent complaint information from consumers. This potentially limits the FTC’s ability to categorize and summarize contributor information and report on the complaint data FTC receives. The total number of fraud complaints in Sentinel and associated dollar losses could be understated because not all contributors request that consumers provide the dollar amount lost as part of a scam or provide specific information about the type of scam they encountered in predefined data fields.

FTC maps CFPB complaints by type that come into Sentinel, but because CFPB collects the dollar amount lost in a narrative data field and does not have a separate data field for the dollar amount lost, that information is not captured separately. This limits the ability to use fraud reports received from CFPB to calculate a single measure of consumer scam complaints and losses. According to FTC, in 2024, while CFPB was the largest contributor of Sentinel complaint data, it was a source of just 1 percent of fraud complaints. FTC officials noted that FTC assigns contributors’ data that do not match the FTC’s categories to the appropriate category in Sentinel, where possible.

FBI officials also told us that not all IC3 scam complaints are contributed to Sentinel. For example, complaints that are filed with IC3 on behalf of a business with the business name included, or that are referred to a field office, are not provided to Sentinel. FBI officials stated that IC3 complaints filed on behalf of a business include reports about business database intrusions, ransomware attacks, and intellectual property rights and that providing this information to FTC could jeopardize trust in FBI. FBI noted that it shares some of the information it collects with other government agencies in service of its intelligence mission and to contribute to the federal government’s strategic understanding of cyber threats; however, FBI does not share cyber victim information with other government agencies. Excluding complaints that are filed on behalf of a business from Sentinel could also exclude some complaints related to scams.

According to FTC, it has not been seen as necessary for Sentinel contributors to change the data fields collected to match its data fields or to provide consistent data fields, as there are cost considerations for contributors in doing so, and each agency has unique data collection needs. Additionally, contributor databases may predate their decision to become a Sentinel contributor. FTC officials stated that the agency would always welcome more data that could be appropriately formatted into Sentinel data fields and works with its data contributors to improve how data are contributed. Although over 75 percent of 2024 Sentinel fraud data were provided by FTC and two other contributors, FTC officials told us that FTC works with Sentinel contributors to align the data they submit with the fields in Sentinel. These officials stated that the agency has a group that reviews the categories to determine which ones remain relevant over time and which ones need to be retired. They also monitor the information submitted by their contributors to ensure it still aligns with the correct fields. Every year, the volume of information FTC receives continues to increase, so it has started using tools, such as machine learning, to read complaint narratives to ensure the category of the complaint is correct, according to FTC officials.

While such efforts to strengthen the data are helpful, the agencies experience a variety of data limitations, as discussed above. Such limitations affect their ability to report on the types and extent of scams, target preventative efforts, and measure progress in scam prevention.

Agencies Can Estimate the Number of Scam Complaints and Associated Losses

CFPB, FBI, and FTC can calculate an estimate of complaints they receive that are related to scams but not the exact number of scam complaints. However, these agencies do not publicly report these estimates and each of these estimates has limitations.

While CFPB does not publish a count of scam complaints received, agency officials told us that CFPB had developed a model that conducts a text analysis of consumer complaint narratives that can identify complaints likely—but not definitively—related to scams over the P2P platforms only. Based on the CFPB’s modeling, the agency estimates that in 2023, it received 3,210 complaints potentially regarding scams over P2P platforms. CFPB officials stated that they did not have a loss estimate for scam-related complaints because they do not require consumers to include dollar losses when filing a complaint.

FBI officials stated that they could quantify the number of complaints FBI receives about scams wherein the victim specified a dollar loss. Although the officials noted that FBI does not include, in its annual reports, a line item for total scam complaints received and associated dollar losses, it compiled the total at our request. According to FBI officials, in 2023, IC3 estimated that it received over 589,355 complaints related to scams, with losses of $10.55 billion. FBI officials told us that they could consider adding an estimate of scams, and related financial losses, in future annual reports.

FTC officials also told us that they could estimate the number of calendar year 2023 scam complaints and associated financial losses that involved consumers sending payment to a scammer.[59] They said such an estimate could be based on three Sentinel complaint categories that often describe these scenarios and provided an estimate at our request. According to FTC officials, imposter scams (including business, government, and romance imposters), sweepstakes and lottery, and investment-related fraud categories often describe scams involving a consumer making a fraudulently induced bank transfer to a scammer.[60] Based on these three categories in Sentinel, FTC estimates that consumers reported over 280,000 incidents that frequently involved fraudulently induced bank transfer to a scammer in 2023, with reported financial losses totaling over $7.8 billion.

Since CFPB, FBI, and FTC use different, incomplete and, in limited cases, duplicative data and different methodologies to make their estimates of the scam complaints they receive, the estimates cannot be aggregated to make a broader estimate of the total number of scam complaints.

Underreporting of Scams and Lack of a Common Definition Complicate Calculating a Government-wide Estimate of Scams

The underreporting of scams and the lack of a common scam definition complicate calculating a government-wide estimate of scams. According to DOJ and FTC, most consumer fraud goes unreported. For example, in 2015, DOJ estimated that 15 percent of the nation’s fraud victims report their crimes to law enforcement.[61] Consequently, the numbers of instances and loss amounts provided in the annual reports discussed above are likely underestimates. Similarly, a study cited by FTC reported that about 5 percent of people who experienced mass-market consumer fraud complained to a BBB or a government agency.[62] According to FTC officials, the agency has estimated the amount of consumer fraud losses—not specific to just scams—taking into account underreporting, but officials stated more research was needed to accurately extrapolate a single estimate of scams based on consumer complaint data.[63]

FBI and FTC officials cited challenges to providing an overall estimate of the number of scams and associated dollar losses impacting the public. According to FTC officials, it would be difficult for CFPB, FBI, and FTC to work together to estimate the overall number of consumers affected by scams and their losses because consumer underreporting rates are unknown and could vary by loss amount. FBI officials stated that losses reported by FTC and CFPB could be inflated or underestimated, depending on whether they adjust consumer-reported losses. According to FBI officials, many complainants may provide a higher loss to garner faster attention, or inadvertently enter an inflated loss amount.

Moreover, other data sources suggest that the total number of scams affecting the public could be larger than indicated by complaint data. Specifically, in 2024, FinCEN published a report analyzing identity-related suspicious activity involving impersonation, which includes scams, that estimated a higher number than the scam complaint totals provided by FBI and FTC.[64] Even though there are duplicate filings in the data, this report can provide insights on the scale of this suspicious activity. Based on the Bank Secrecy Act data filed with FinCEN in 2021, FinCEN identified a total of $566 billion in suspicious activity. Of this amount, $200 billion was related to impersonation-related suspicious activity, such as romance scams, person-in-need scams, tech and customer support scams, employment scams, and financial institution and government imposter scams.

We have previously reported on the importance of knowing and understanding the scope of fraud in managing fraud risk.[65] Fraud estimates, including those specifically addressing scams, can demonstrate the scope of the problem, could help improve oversight prioritization, and could help determine the return on investment from activities to mitigate fraud.