FEDERAL POLICE OFFICERS

Considerations on Retirement and Pay

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107099. For more information, contact Gretta L. Goodwin at GoodwinG@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107099, a report to congressional committees

Considerations on Retirement and Pay

Why GAO Did This Study

Federal police forces play a key role in maintaining the safety and security of federal property, employees, and the general public. Federal law generally does not consider most of these officers to be law enforcement officers for the purpose of receiving enhanced retirement benefits and pay. However, over time, legislation has provided federal police forces at some agencies enhanced retirement benefits, even when they did not meet the legal statutory and regulatory definitions of a law enforcement officer. Some agencies have cited challenges recruiting or retaining federal police officers because of the difference in retirement benefits and pay compared to statutory law enforcement officers.

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 includes a provision for GAO to report on considerations regarding retirement and pay issues for federal police officers. This report provides information on (1) characteristics and duties of the federal police officer workforce; (2) changes agencies can make regarding retirement and pay; and (3) considerations regarding implementation, finance, and workforce planning to help inform congressional decision-making regarding changes to retirement and pay.

To conduct this work, GAO administered two surveys—one to eight departments and another to 17 components within these departments —to gather their perspectives. GAO analyzed past GAO and OPM studies on this topic and used OPM data to conduct analysis.

What GAO Found

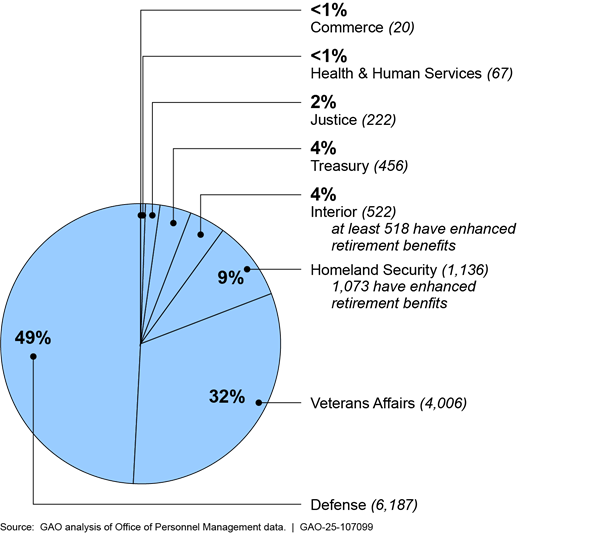

Federal police officer primary duties include the preservation of the peace, crime prevention and detection, and responding to emergencies on or near federal property. At the end of fiscal year 2023, 17 agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, employed approximately 12,600 federal police officers within eight executive branch departments. The majority work for the Departments of Defense (49 percent) and Veterans Affairs (32 percent).

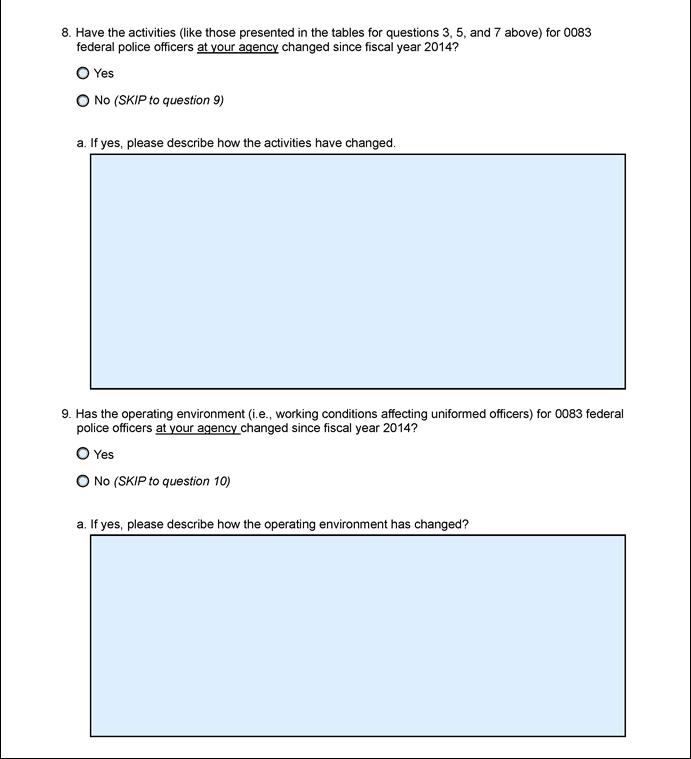

Seven of 17 federal agencies GAO surveyed stated that federal police officer activities have changed since fiscal year 2014. Agencies cited an increased threat environment, civil unrest, and the need for overtime to address staffing shortages as examples of changes in working conditions for federal police officers.

Federal police officers generally do not receive enhanced retirement benefits. These enhanced benefits accrue at a higher rate over a shorter period of time than standard federal employee retirement benefits. However, if a department determines that a group of employees, such as federal police officers, meets certain criteria to receive enhanced retirement benefits, it notifies the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), which will review the decision for statutory compliance. None of the eight executive branch departments GAO surveyed had done so for their federal police officers in the past 10 years. GAO’s analysis of OPM data showed that federal police across these departments are on nine different pay plans and various specialized pay rates within some of those plans, creating variation.

GAO identified a range of considerations regarding potential changes to federal police officers’ retirement and pay provisions. These include whether to account for past service, whether federal police officers need to meet physical suitability standards, and whether to provide opt-in or opt-out options. Additionally, changes regarding retirement or pay could have budgetary effects on departments and agencies. For example, retroactively applying enhanced retirement benefits could be very costly to departments and agencies.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FBI |

Federal Bureau of Investigation |

|

FERS |

Federal Employees Retirement System |

|

GS |

General Schedule |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 2, 2025

The Honorable Bill Hagerty

Chair

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Dave Joyce

Chairman

The Honorable Steny Hoyer

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

Federal police forces play a key role in maintaining the safety and security of federal property, employees, and the general public. Federal police forces include the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) police, Veterans Affairs police, Department of Defense police forces, the U.S. Park Police, and others in the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. While police officers are commonly thought to be law enforcement officers in the broad sense of the term, federal law generally does not consider most federal police officers to be law enforcement officers for the purpose of receiving enhanced retirement benefits and pay.[1] The definition of a “law enforcement officer” is specified by federal law and regulation and generally does not include an employee whose primary duties involve maintaining law and order and protecting life and property.[2]

Federal police officers generally receive the standard Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS) retirement benefit that other federal employees receive, rather than the enhanced retirement benefits that statutorily defined law enforcement officers receive.[3] However, over time, federal police forces at some agencies have been made eligible to receive enhanced retirement benefits through direct legislation, even where they might not otherwise meet the statutory definition of a law enforcement officer, which has created variation. Some agencies have also cited challenges in being able to recruit or retain federal police officers because of the difference in retirement benefits and pay compared to statutory law enforcement officers. Additionally, federal police officer advocates have asserted that federal police officer activities have changed over time, making them more comparable to federal law enforcement officer activities.

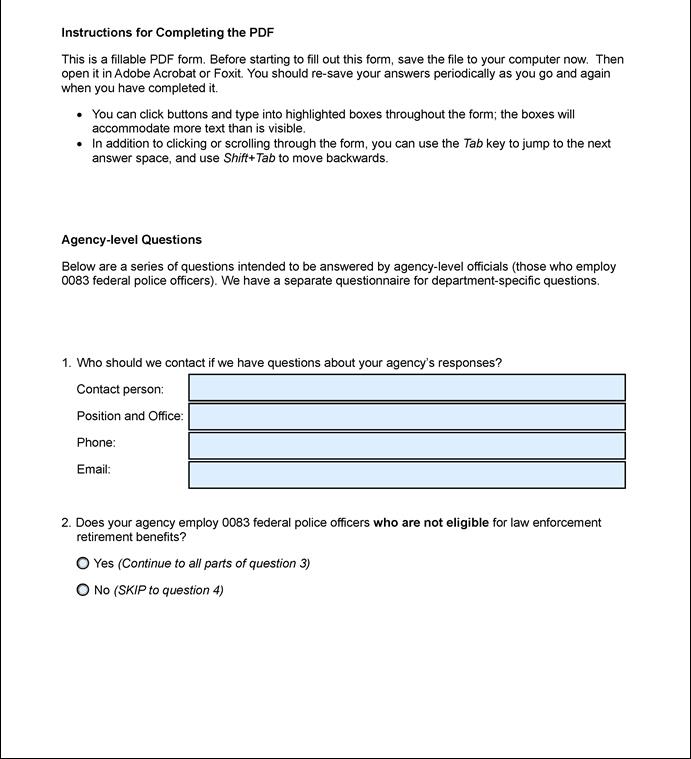

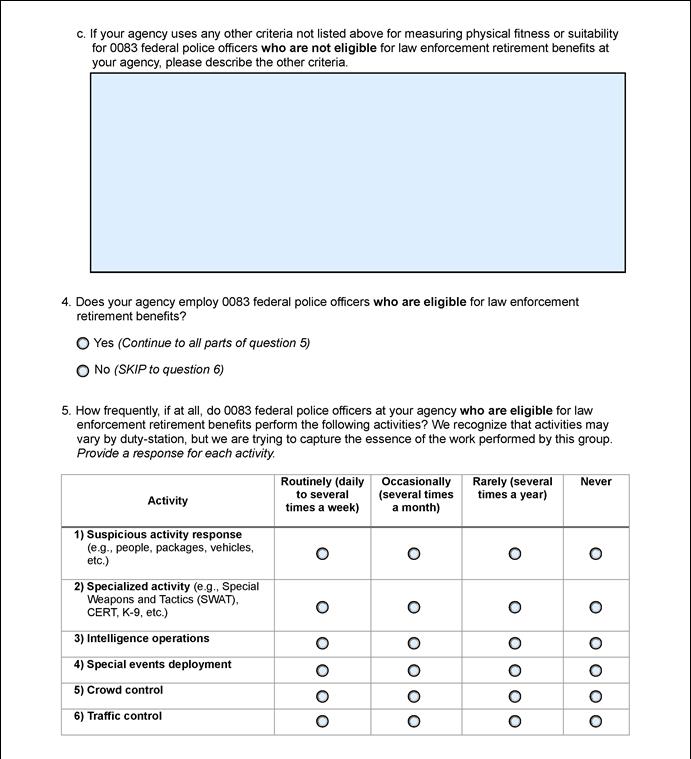

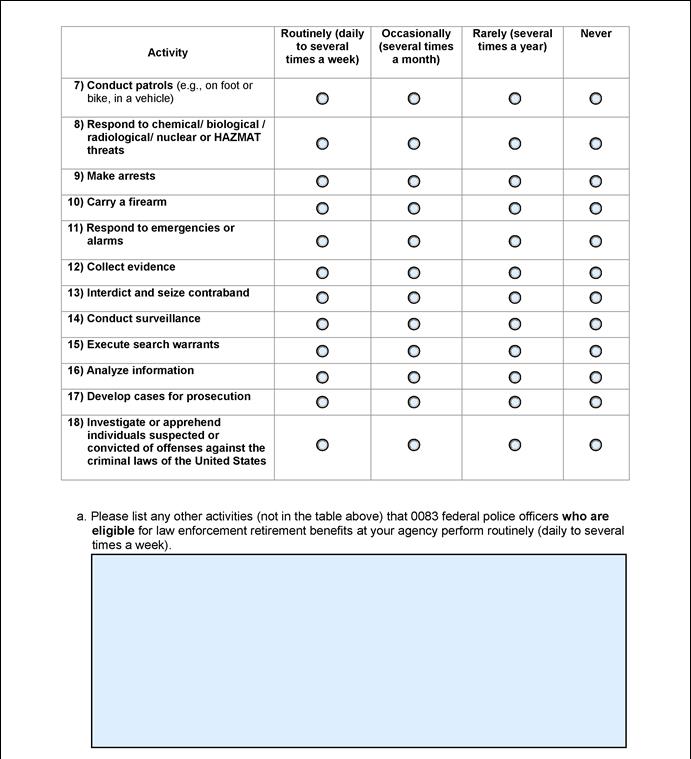

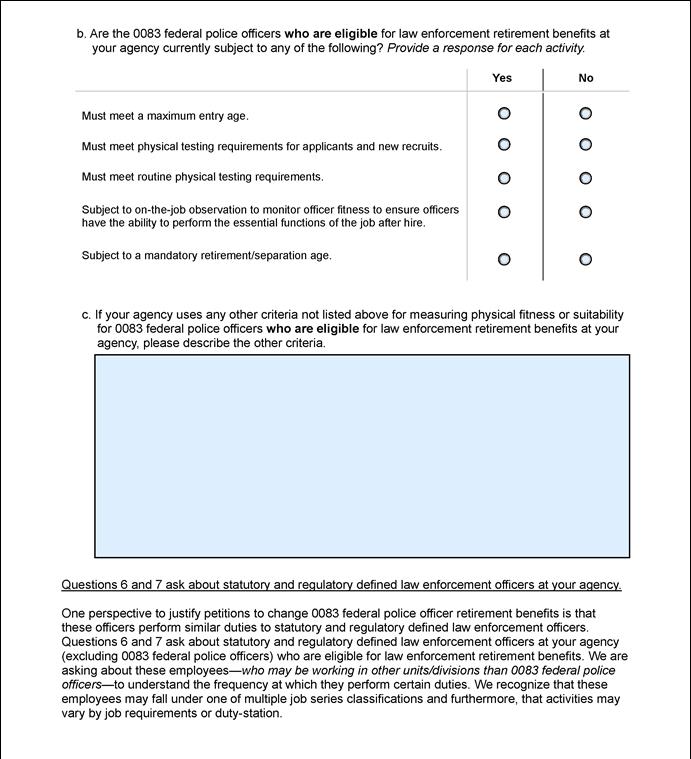

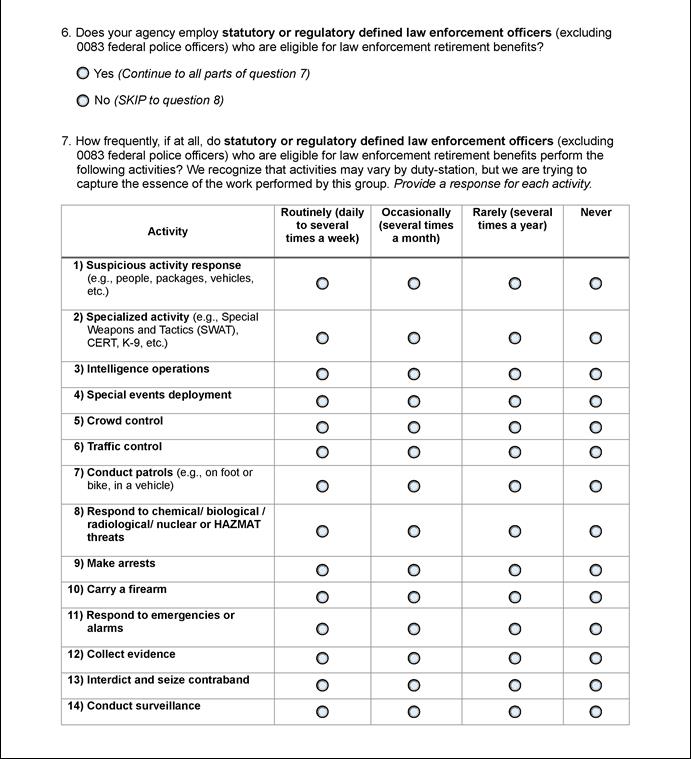

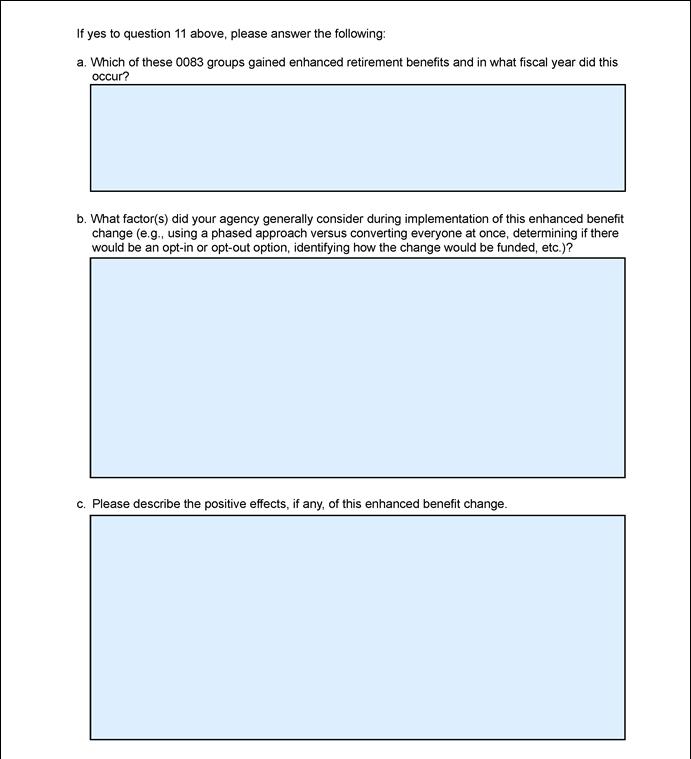

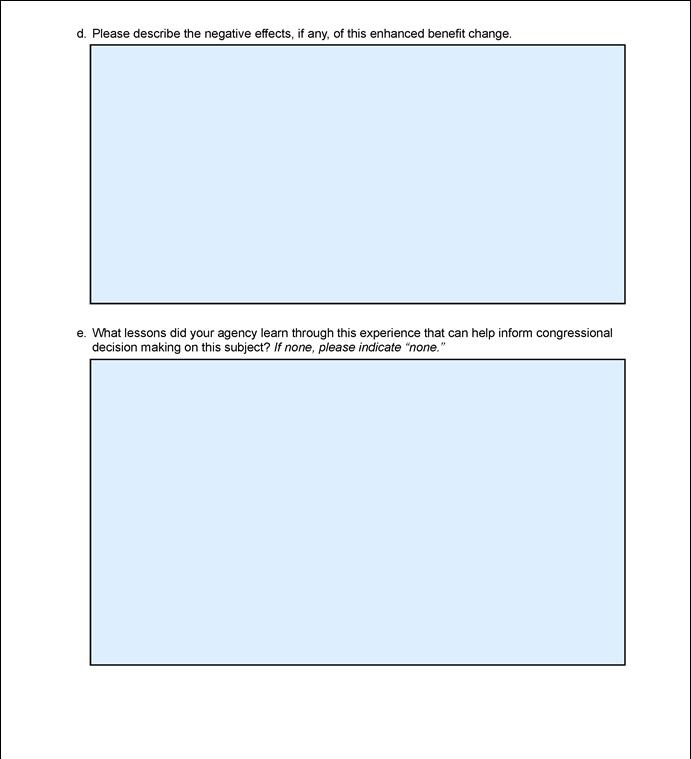

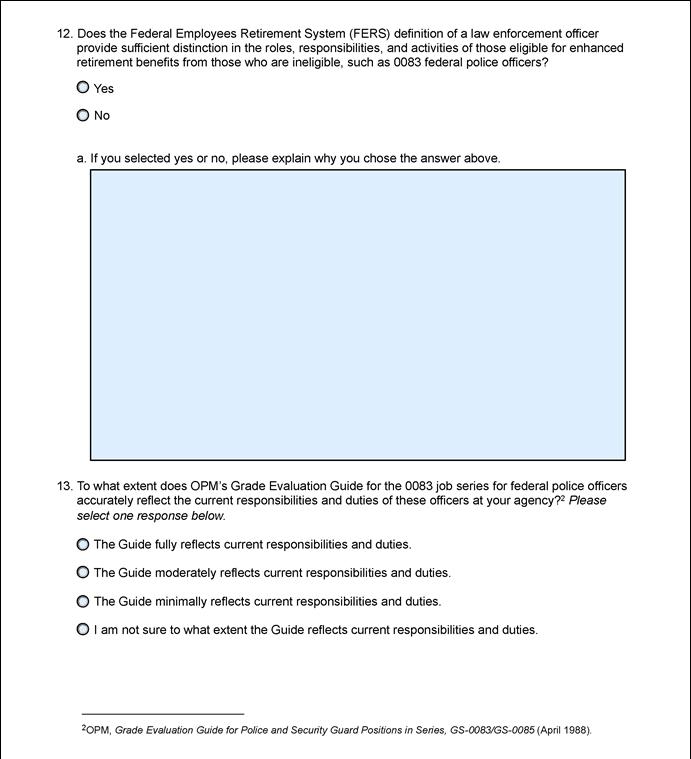

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023,[4] includes a provision for GAO to conduct a study of the FBI and other agencies that employ General Schedule police officers and report to the Committees regarding the issues that would need to be addressed by Congress if it decided to cover police officers under the law enforcement officer retirement provisions and the need for higher pay levels for General Schedule police officers.[5] This report provides information on three areas related to federal police officers (1) characteristics of the federal police officer workforce, including their job activities; (2) changes agencies can make regarding retirement and pay; and (3) considerations regarding implementation, finance, and workforce planning to help inform congressional decision making regarding changes to retirement and pay.

Based on the information in OPM’s database, we identified the following eight executive branch departments employing civilian federal police officers in the 0083 job series: The Departments of Commerce, Defense, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, the Interior, Justice, the Treasury, and Veterans Affairs. Within the eight departments, we identified the following 17 agencies that employ federal police officers: Commerce’s Office of the Secretary, Defense Logistics Agency, Pentagon Force Protection Agency, Air Force, Army, Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, National Institutes of Health, Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Headquarters, Federal Emergency Management Agency, U.S. Secret Service Uniformed Division, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Park Service, Bureau of Engraving and Printing, U.S. Mint, and Veterans Health Administration.[6]

To characterize the federal police forces, we queried the OPM data to identify the federal police officers by department, location, age, years of service, basic pay, and retirement plan. We assessed the reliability of the OPM data through electronic testing to identify missing data, out-of-range values, and logical inconsistencies. We reviewed prior GAO and OPM work assessing the reliability of these data. On the basis of this assessment, we believe the data used are sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

To identify changes agencies can make regarding retirement and pay, and to identify considerations regarding implementation, finance, and workforce planning to help inform congressional decision-making regarding changes to retirement and pay, we reviewed relevant laws and regulations, reviewed relevant studies to identify factors for consideration, administered survey instruments to selected departments and agencies, and interviewed officials at OPM and relevant stakeholders.[7] Additionally, we conducted an attrition analysis for fiscal years 2019 through 2023 to determine whether federal police officers receiving standard FERS retirement benefits voluntarily moved to another federal position with enhanced retirement benefits, by calculating voluntary internal transfers.

For more details on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I. For copies of our survey instruments, see appendices II and III.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Defining Federal Police and Law Enforcement Officers

Police officers are commonly thought of as law enforcement officers. However, for the purpose of receiving enhanced federal retirement benefits, the definition of a federal law enforcement officer is specified in law and regulation and generally excludes some duties typically performed by federal police officers.[8] Federal police officers and statutory law enforcement officers are defined as follows:

Federal police officers. OPM defines the federal police officer series (job series 0083) as positions in which the primary duties are the performance or supervision of work in the preservation of the peace; the prevention, detection, and investigation of crimes; the arrest or apprehension of violators; and the provision of assistance to citizens in emergency situations, including the protection of civil rights.[9] According to OPM, federal police officers may perform or supervise work that is investigative in nature with a primary focus on security and crimes committed on or adjacent to federal property. Because OPM has determined that some of these common duties do not meet the statutory definition of “law enforcement officer,” federal police officers generally do not qualify for FERS enhanced retirement benefits.[10]

Statutory law enforcement officers. The FERS statutory definition of a law enforcement officer generally includes those personnel whose duties are primarily the investigation, apprehension, and detention of individuals suspected or convicted of offenses against the criminal laws of the United States, or the protection of U.S. officials against threats to personal safety.[11] The FERS definition of a law enforcement officer also expressly includes a rigorous duty standard, which provides that the duties of these positions must be sufficiently rigorous such that “employment opportunities should be limited to young and physically vigorous individuals.”[12] More specifically, federal regulation, which defines the rigorous duty standard, states a “rigorous position” means, in part, “a position the duties of which are so rigorous that employment opportunities should, as soon as reasonably possible, be limited (through establishment of a maximum entry age and physical qualifications) to young and physically vigorous individuals.”[13]

Enhanced Retirement Provisions

Statutory law enforcement officers are eligible to receive an enhanced retirement benefit and are generally subject to “mandatory separation” (which we refer to as mandatory retirement) from their law enforcement positions at age 57.[14] The enhanced retirement benefit accrues at a higher rate than standard federal employee retirement benefits and may accrue over a shorter period of time due to the mandatory retirement age.[15] Statutory law enforcement officers are generally eligible to retire with an annuity at age 50 if they have a minimum of 20 years of eligible service and may retire with an annuity at an earlier age if they have at least 25 years of eligible service.[16] However, in some cases, a statutory law enforcement officer may work past age 57 if needed to complete 20 years of law enforcement service.[17]

According to OPM, agencies typically establish a maximum entry age for statutory law enforcement officers based on the age and service requirements for mandatory retirement. The maximum entry age is typically age 37 because it allows an employee to achieve 20 years of service when they reach the mandatory retirement age of 57. In contrast, federal police officers are generally not eligible for these enhanced retirement benefits and are treated as standard employees under FERS. Table 1 below shows the difference in employee deductions and agency contributions for standard FERS employees and those who receive the enhanced retirement benefit.

Table 1: Differences in the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS) for Standard Federal Employees/Federal Police Officers versus Statutory Law Enforcement Officers, as of Fiscal Year 2023

|

|

FERS standard employee, including federal police officers |

FERS law enforcement officer |

|

Contributor |

Deduction from employee pay |

|

|

EMPLOYEE |

|

|

|

Employee retirement deductions-employed before January 2013 |

0.8 percent of basic pay |

1.3 percent of basic pay |

|

Employee retirement deductions-employed during 2013 |

3.1 percent of basic pay |

3.6 percent of basic pay |

|

Employee retirement deductions-employed on/after January 1, 2014 |

4.4 percent of basic pay |

4.9 percent of basic pay |

|

AGENCYa |

Contribution from agency |

|

|

Agency retirement contributions-employed before January 2013 |

18.4 percent of basic pay |

37.6 percent of basic pay |

|

Agency retirement contributions-employed during 2013 |

16.6 percent of basic pay |

35.8 percent of basic pay |

|

Agency retirement contributions-employed on/after January 1, 2014 |

16.6 percent of basic pay |

35.8 percent of basic pay |

Source: GAO analysis of Office of Personnel information. | GAO‑25‑107099

Note: Percentages for those hired before 2014 provided to reflect deductions and contributions for the range of employees discussed in this report. For example, a 30-year-old hired in 2012 would turn 42 years old in 2024. It also shows how deductions and contributions have changed over time.

aAgencies also pay the employer portion of Social Security as well as a Thrift Savings Plan match. Agency contribution does not reflect new changes in Fiscal Year 2024.

Pay Plans and Special Pay Provision for Federal Police Officers and Statutory Law Enforcement Officers

There are multiple pay plans for federal police officers and multiple factors determine pay, such as the basic pay amount, the demands of the work and qualifications, and the locality or duty station.[18] Most federal police forces are covered by OPM’s General Schedule (GS) basic pay plan (i.e., standard basic pay plan). Under the standard basic pay plan, OPM generally sets the basic pay ranges (grades) and pay increases (steps) within each grade for the positions, and employers of federal police officers use these grades and steps to compensate their employees. According to OPM, it may also establish higher rates of basic pay (special rates) for a group or category of GS positions in one or more geographic areas to address significant existing or likely challenges in recruiting or retaining well-qualified employees.

Some federal police forces are covered under non-standard basic pay plans established by law. These provide basic pay rates different from those specified in a standard basic pay plan and thus have the ability to offer higher minimum entry-level salaries than those provided to federal police officers under a standard pay system. For example, the Secretary of the Treasury was authorized by law to establish a pay system for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and U.S. Mint federal police officers that sets pay above GS rates for comparable federal police officers.[19]

Statutory law enforcement officers within the GS system are entitled to higher rates of basic pay at grades GS-3 through GS-10 on the GL pay plan.[20] We reported in 2019 that some statutory law enforcement officers also have the ability to receive premium pay for certain types of overtime worked.[21] These special overtime payments are generally paid as a fixed percentage of the statutory law enforcement officer’s basic pay on a recurring basis (up to 25 percent). For example:

· Law Enforcement Availability Pay can be paid to criminal investigators and other approved law enforcement officers and is a fixed supplement at 25 percent of base pay.[22]

· Administratively Uncontrollable Overtime can be paid at agency discretion to certain law enforcement officers, primarily in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).[23] This is a recurring payment that is generally fixed at a percentage of basic pay ranging from 10 to 25 percent.

The premium pay for these two types of overtime pay may be used in the calculation of retirement benefits for statutory law enforcement officers.

Enhanced Retirement Benefits Have Been Extended to Various Groups Over Time

The definition of “law enforcement officer” can be traced back to as early as 1948. In 1948, legislation was enacted into law that, in general, provided enhanced retirement benefits to certain federal officers whose duties were primarily the investigation, apprehension, or detention of persons suspected or convicted of offenses against the criminal laws of the United States.[24] When legislation established FERS in 1986, its definition introduced and currently includes a rigorous duty standard.[25] According to an OPM report, such benefits were to assist the federal government with encouraging the maintenance of a young and vigorous law enforcement workforce through youthful career entry, continuous service, and early separation.[26]

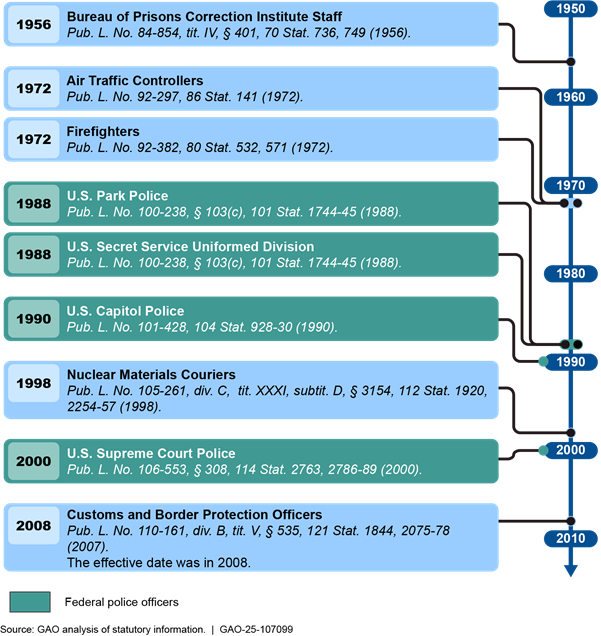

Over time, legislation extended enhanced retirement benefits to certain federal uniformed police groups within the broader federal law enforcement community, even where they did not meet the statutory definition of a law enforcement officer. For example, the House Report accompanying the legislation providing enhanced retirement benefit coverage to the U.S. Park Police and U.S. Secret Service Uniformed Division acknowledged these groups did not meet the definition of a law enforcement officer, but amended the statute to ensure these police officers were eligible for the enhanced retirement coverage.[27] As shown in figure 1, legislation has extended enhanced retirement benefits to certain employees, including U.S. Secret Service Uniformed Division officers, U.S. Park Police, U.S. Capitol Police, U.S. Supreme Court Police, and other groups not considered part of the statutory and regulatory definition of law enforcement officer for the purpose of receiving enhanced retirement benefits.

Figure 1: Timeline of Major Occupational Groups Legislatively Designated Eligible for Enhanced Retirement Benefits

Longstanding Issues Regarding Retirement and Pay

Over the past 2 decades, we and others have reported on various issues regarding retirement and pay for federal police officers. Specifically, in four reports we issued from 2003 to 2019, we reported on issues such as retirement, pay, and attrition for certain federal police forces.

· In 2003, we reported that officials at federal police forces raised concerns that disparities in pay and retirement benefits had caused uniformed police forces in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area to experience difficulties in recruiting and retaining officers. We reported on variation in pay for 13 uniformed police forces in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, the turnover rates for these police forces, and the extent to which their agencies used human capital flexibilities to address recruitment and retention.[28]

· In 2009, we reported on an increase in the number of persons employed by federal agencies performing various law enforcement functions and the inconsistent eligibility of those employees to receive enhanced retirement benefits. We reported ways groups of employees may be granted enhanced retirement benefits and the rationales for doing so.[29]

· In 2012, we reported that officials were concerned that disparities in pay and retirement benefits had caused federal police forces to experience difficulties in recruiting and retaining officers. We issued a report comparing the retirement, pay, duties, and attrition of the U.S. Capitol Police to nine other federal police forces in the Washington, D.C. area.[30]

· In 2019, we reported on the potential effects of raising the retirement age for U.S. Capitol Police officers, who are subject to the FERS mandatory retirement provision described above.[31] The Capitol Police had used temporary waivers of the mandatory retirement age to address various staffing shortages, and this report explored the potential effects of raising the mandatory retirement age across federal executive branch law enforcement agencies.

In response to section 2 of the Federal Law Enforcement Pay and Benefits Parity Act of 2003,[32] OPM published a report to Congress recommending strategies for addressing the discrepancies across agencies concerning law enforcement officers’ job classifications, pay, and benefits, including officers who have been granted law enforcement officer-equivalent benefits.[33] At the time the report was published in 2004, OPM recommended that Congress provide it with broad authority to establish a government-wide framework for law enforcement retirement, classification, and pay systems.[34] The report highlighted the disparities related to changes in these areas as a result of incremental legislation and litigation, and the need to address the modern-day challenges facing agencies with expanding law enforcement missions. Because these same issues persist today, we cite various OPM findings throughout this report.[35]

According to a recent Congressional Research Service report, several employee groups and unions representing individuals not considered to be eligible for enhanced benefits have sought changes through additional legislation.[36] The report cites equity and attrition as two of the primary reasons why these groups support extending enhanced retirement benefits to officers currently excluded. Specifically, advocates believe federal police officers are performing similar duties to law enforcement officer personnel and said there is higher attrition among federal police officers compared to groups of employees with enhanced law enforcement benefits.[37]

The specific legislative actions referenced in figure 1 above that extended enhanced benefits to some police forces and not others have led to inconsistency in how federal police officers are compensated. To help address this issue, Members of Congress have introduced bills they said were designed to create parity for employees and agencies by providing enhanced benefits to specified employee groups. For example, as we reported in 2009, various bills were introduced in the 110th Congress that would have provided enhanced benefits to a variety of employees, including certain federal police, who have not been found to meet the statutory law enforcement officer definition.[38] However, these bills were not enacted into law. More recently, additional bills were introduced in the 118th Congress to include certain federal positions within the definition of law enforcement officer for retirement and other purposes.[39]

Characteristics and Duties of the Federal Police Officer Workforce

Where do federal police officers work?

Federal police officers are employed across eight executive branch departments.[40] OPM’s personnel data showed these departments employed approximately 12,600 federal police officers at the end of fiscal year 2023. Figure 2 shows the Departments of Defense (49 percent) and Veterans Affairs (32 percent) employed the majority of federal police officers. According to our analysis of OPM’s personnel data, the number of federal police officers employed from fiscal years 2019 through 2023 ranged from approximately 12,600 to 13,100 officers.

Note: Bureau of Indian Affairs was excluded from this analysis since its federal police officers transitioned to a different job series in fiscal year 2023. Additionally, due to rounding, estimated values do not equal 100 percent. Data only reflect departments that provide information to Office of Personnel Management. Therefore, it does not include any intelligence agencies within these departments or the legislative and judicial branch agencies.

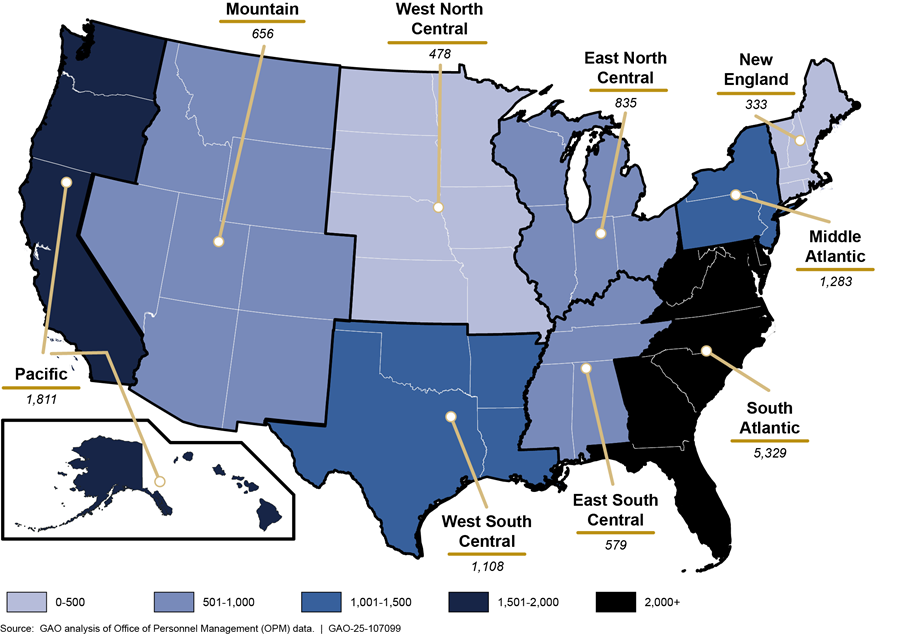

Geographic location varies for federal police officers. We found that at the end of fiscal year 2023, the majority of federal police officers (75 percent) were stationed outside the Washington D.C. Metropolitan area. The highest number of police officers were in the South Atlantic and Pacific regions, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: The Number of Federal Police Officers in the OPM 0083 Job Series, as of the end of Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Bureau of Indian Affairs was excluded from this analysis since its federal police officers transitioned to a different job series in fiscal year 2023. In addition, 204 federal police officers are stationed in two U.S. territories and two foreign countries.

What are federal police officers’ ages and years of service?

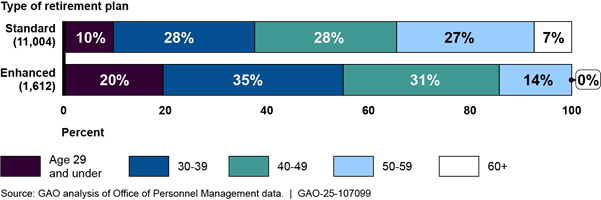

Federal police officer age and years of service vary, but both are key determinants of retirement benefits eligibility. For example, in fiscal year 2023, the majority of the total federal police workforce in our scope—those with and without enhanced benefits—were under the age of 50. As shown in figure 4, age varied among federal police officers with standard FERS and enhanced retirement plans.

Figure 4: Age of Federal Police Officers with Standard and Enhanced Federal Employees Retirement System Benefits, Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Bureau of Indian Affairs was excluded from this analysis since its federal police officers transitioned to a different job series in fiscal year 2023. Federal police officers with enhanced retirement benefits are eligible to receive an enhanced retirement benefit and are generally subject to mandatory retirement at age 57 with 20 years of qualifying service. In fiscal year 2023, fewer than 11 federal police officers with enhanced retirement benefits were aged 57 and over. According to GAO’s data use agreement with the Office of Personnel Management, data suppression is required for values less than 11.

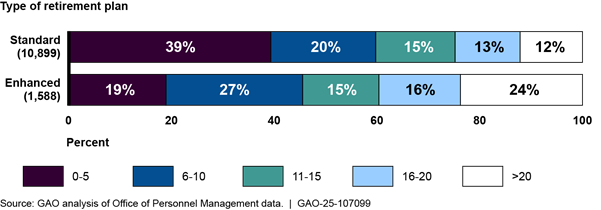

In fiscal year 2023, 39 percent of federal police officers on the standard FERS retirement plan had less than 5 years of federal service. Comparatively, 19 percent of federal police officers with enhanced retirement benefits had less than 5 years of service (see fig. 5).[41]

Figure 5: Years of Service for Federal Police Officers with Standard and Enhanced Federal Employees Retirement System Benefits, Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Bureau of Indian Affairs was excluded from this analysis since its federal police officers transitioned to a different job series in fiscal year 2023. Due to rounding, estimated values do not equal 100 percent. In addition, totals may differ from figure 2 due to missing data (n=129) from the Office of Personnel Management’s database on service computation date for retirement. Federal police officers with enhanced retirement benefits are eligible to receive an enhanced retirement benefit and are generally subject to mandatory retirement at age 57 with 20 years of qualifying service. Estimates are of the total federal service and may not reflect years of service solely in the federal police officer position.

What activities do federal police officers perform?

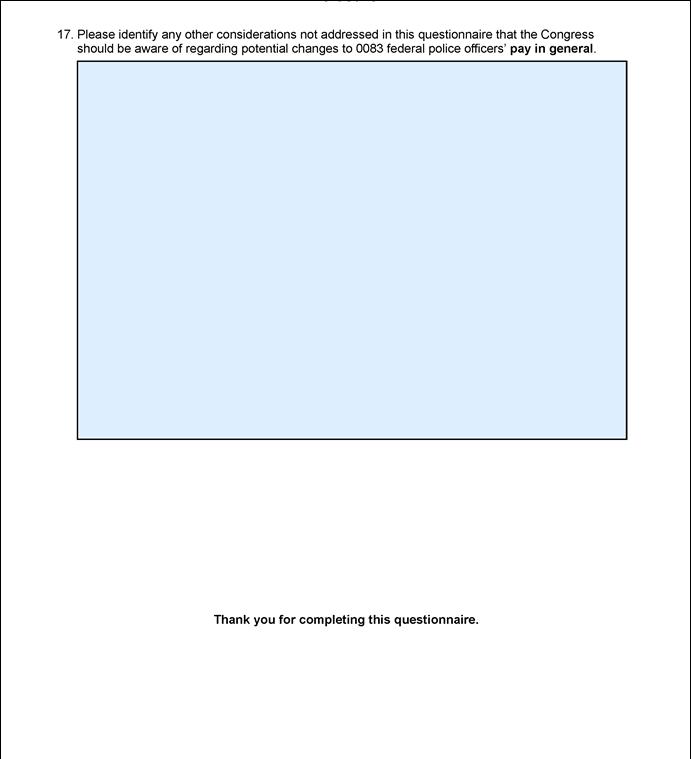

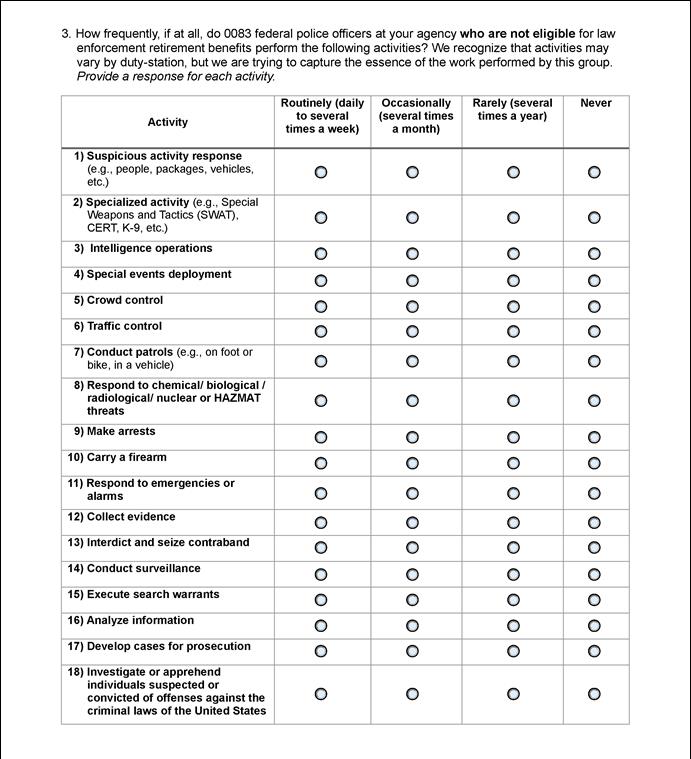

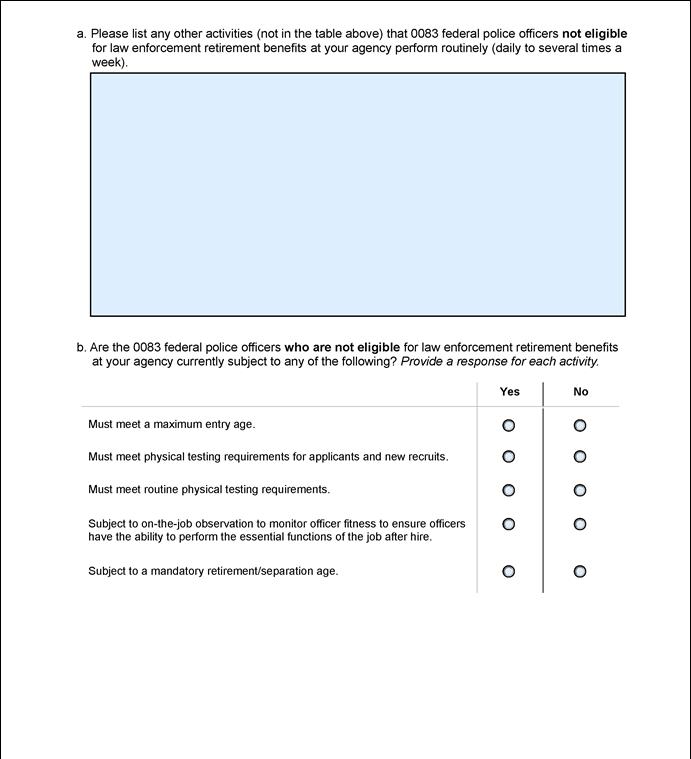

Federal police officers have primary responsibility for protecting federal property, employees, and the general public. OPM officials said agencies have the authority to define the work within a job series and develop specific job descriptions. According to our survey results, federal police officer activities are changing in response to an evolving work environment. However, while federal police officers and law enforcement officers may report conducting similar activities, the nature and complexity of those activities, such as conducting investigations, may vary.

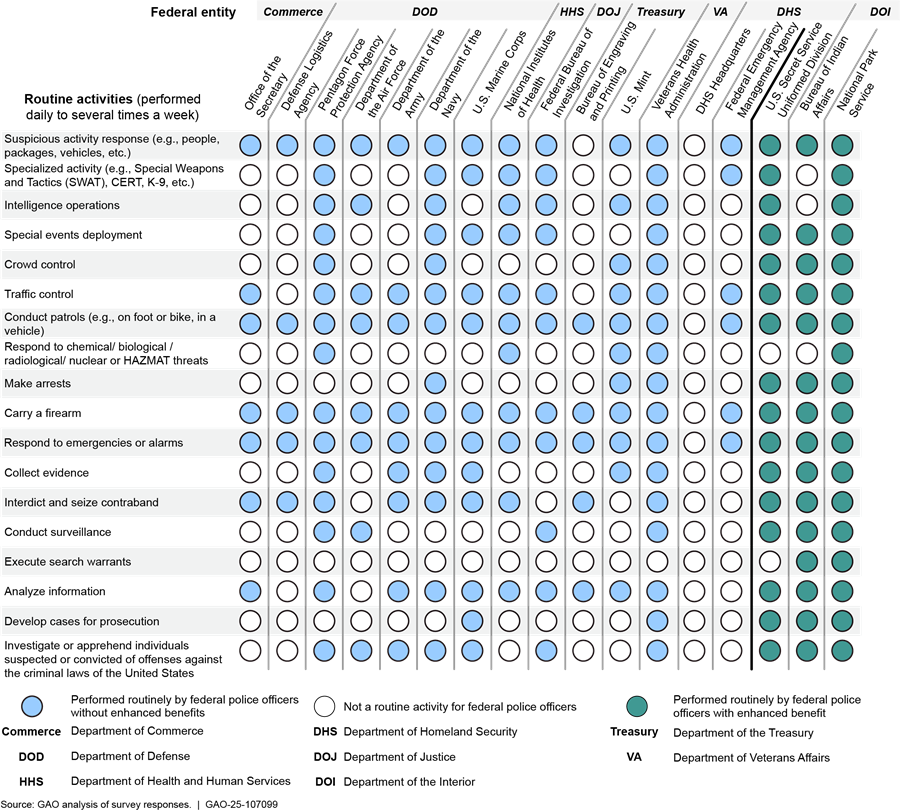

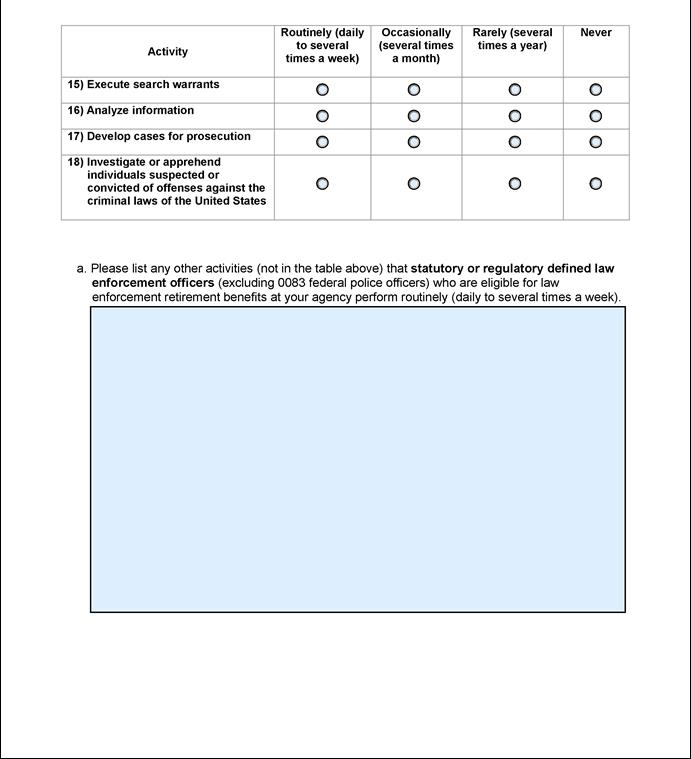

Routine activities. To understand how activities may vary depending on the agency where federal police officers work and whether or not they have enhanced retirement benefits, we surveyed agencies to identify what activities their federal police officers performed routinely. As shown in figure 6 below, the activities police officers performed varied by agency. Additionally, police officers with and without enhanced retirement benefits perform some of the same activities, but not always with the same routine frequency.

Figure 6: Comparison of Activities Federal Police Officers With and Without Enhanced Benefits Performed Routinely, as of October 2024

Note: We asked agencies that employ federal police officers to identify the duties they perform routinely, occasionally, rarely, and never (see appendix III, questions 3 and 5). For example, DHS Headquarters officials indicated federal police officers occasionally (several times a month) performed 16 of 18 activities, but did not perform any routinely.

Activities most frequently identified as performed routinely (daily to several times a week) by federal police officers across the 17 agencies included responding to suspicious activities (15 of 17), conducting traffic control (14 of 17) and patrols of various types (16 of 17), and responding to emergencies or alarms (16 of 17).[42] Federal police officers at all but one agency routinely carry a firearm, and approximately one-third of agencies (six of 17) indicated federal police officers routinely make arrests. Agencies also responded that their federal police officers routinely conduct anti-terrorism measures or provide high-level dignitary protection to the President, Vice President, and foreign heads of state (seven of 17).[43]

Four of 17 agencies responded that federal police officers are highly trained to perform law enforcement related activities, although they may not perform these activities on a routine basis.[44] For example, the Pentagon Force Protection Agency said while its officers have arrest authority, it is not an activity they perform daily or several times a week. According to our survey results, four of 17 agencies responded they occasionally (several times a month) make arrests. Additionally, FBI officials said since fiscal year 2014, its federal police officers are mandated to maintain additional certifications in Active Shooter Response, Care Under Fire, First Aid and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, Patrol Rifle qualifications, Protective Detail, and De-escalation training.[45]

Evolving work environment. According to the agencies we surveyed, federal police officer activities are changing in response to an evolving work environment. Nearly half of federal agencies (seven of 17) in our review said activities for federal police officers have changed at their agency since fiscal year 2014.[46] Additionally, nearly half of the agencies (eight of 17) reported that working conditions for federal police officers have changed since fiscal year 2014. Examples of changes to the working conditions of federal police officers described by the agencies were an increased threat environment, civil unrest, increasing attrition rates, and the need for overtime to address staffing shortages.[47] In addition, two of the three associations we met with described that the activities of federal police officers have evolved and are comparable to the work of statutory law enforcement officers. For example, one association stated that federal police officers are conducting sophisticated patrol activity and surveillance, as well as responding to spontaneous violent crime without any backup help.

Moreover, 10 of 17 agencies in our review responded that the OPM Grade Evaluation Guide that outlines the duties and responsibilities of federal police officers moderately or minimally reflects the current work environment for federal police officers.[48] All 10 of those agencies reported that the description needs to be revised to reflect the current duties and responsibilities of federal police officers employed by their agency.[49] However, OPM noted that agencies determine the work assigned and performed by employees, as required by the agency’s mission, and that updates to classification criteria may be made, but the duties of a position determine the type of retirement coverage, as defined in statute.[50]

Law enforcement officer activities. Nearly half of federal agencies in our review (eight of 17) employ both federal police officers with standard FERS retirement benefits and statutory law enforcement officers.[51] However, while federal police officers and statutory law enforcement officers may indicate performing similar activities, the nature and complexity of those activities, such as conducting investigations, may vary.[52]

For example, FBI officials stated the activities of statutory law enforcement officers and federal police officers do not lend themselves to a direct comparison without understanding the level of complexity needed based on the position held. Although FBI police officers and Special Agents (who are law enforcement officers) conduct investigative activities, the scope and purpose of those activities varies. Specifically, FBI officials said that their police officers may conduct investigations and file reports for felonies, misdemeanors, and other offenses—including breaking and entering, willful damage of government and private property, and aggravated assault—that occur at or near an FBI facility. In contrast, their Special Agents perform multi-agency, multi-state, and international investigations to resolve significant criminal and national security issues. According to the FBI, the Special Agents are not typically concerned with independent individuals or small, local groups of individuals committing crimes on federal property unless they are germane to larger investigations.

Similarly, regarding intelligence activities, the Pentagon Force Protection Agency reported that its federal police officers routinely conduct intelligence activities that involve compiling, analyzing, and/or disseminating information in an effort to anticipate, prevent, or monitor criminal activity. However, its federal police officers are not involved in performing traditional intelligence activities through means of collecting information against targets, running sources, and operating intelligence collection platforms.

Officials from the National Institutes of Health within the Department of Health and Human Services further characterized some of the differences between federal police and law enforcement officers. They said while statutory law enforcement officers perform investigations, apprehensions and detentions on a much greater scale than federal police officers, they do not respond to active threats or shooters, assaults in progress, domestic violence, felony vehicle stops, and other daily interactions with people experiencing mental health and drug issues. They recognize that both statutory law enforcement and federal police officers face real and dangerous risks that may differ.

We asked agencies employing federal police officers whether the FERS definition of a law enforcement officer provides sufficient distinction in the roles, responsibilities, and activities of those eligible for enhanced retirement benefits from those who are ineligible.[53] The majority of agencies (12 of 17) said it did not.[54] Agencies identified the following shortfalls in the FERS definition of a law enforcement officer:

· The FERS definition encompassed some, but not all, of the duties performed by federal police officers or should be expanded to include police protection duties.

· The definition does not provide a clear enough distinction as to level of investigation/crime that meets the threshold for enhanced retirement or does not provide sufficient distinction between those eligible or ineligible for enhanced benefits.

· The definition is outdated and does not reflect the current operating environment.

· The definition may not adequately account for the specific challenges and complexities faced by federal police officers.

· Further clarity should be provided for the terms “investigation,” “apprehension” and “detention.”[55]

In OPM’s 2004 report, it recognized the difficulty in applying the statutory definition of a law enforcement officer to modern missions and work environments and noted that direct legislation to provide enhanced retirement benefits to some federal police officers has led to inconsistencies in how that definition is applied. Additionally, as part of our current review, OPM officials recognized that the definition of a federal law enforcement officer for retirement purposes is much narrower than what the public commonly considers “law enforcement” positions and does not include the duties typically performed by federal police officers.

Changes Departments Can Make Regarding Retirement and Pay

How can departments request changes to retirement coverage or pay for federal police officers?

Retirement. Heads of federal departments must determine whether the duties of a position or group of employees, such as a police force within the department, meet the statutory and regulatory definitions for a law enforcement officer position.[56] By law, generally, law enforcement officer position duties must be (1) primarily the investigation, apprehension, or detention of individuals suspected or convicted of offenses against the criminal laws of the United States, or the protection of officials of the United States against threats to personal safety and (2) sufficiently rigorous that employment opportunities should be limited to young and physically vigorous individuals.[57] If the department determines that the duties of the positions meet the statutory and regulatory definitions relating to a law enforcement officer, those positions may be eligible to receive enhanced retirement benefits, special pay or salary provisions, and be subject to a mandatory retirement age.

When department heads decide that a position is a law enforcement officer position, they must notify OPM.[58] Generally, the notice to OPM is to include the title of each position, the number of incumbents, whether the position is primary or secondary, if the position is rigorous, and the established maximum entry age.[59] OPM may, at its discretion, review the position description and revoke the department head’s determination.[60] According to OPM, retirement benefits for all federal employees are driven by statutory provisions.

Seven of the eight departments we surveyed said the process for determining who meets the law enforcement officer statutory definition and who receives law enforcement officer retirement benefits meets the needs of their department.[61] The eighth department, Veterans Affairs, said the process did not meet their needs and could benefit from more streamlining procedures, enhanced transparency, and flexibility to address evolving workforce dynamics. It also said that collaboration with OPM and other relevant stakeholders may be beneficial in identifying and implementing solutions to improve the administration of law enforcement retirement benefits and classifications.

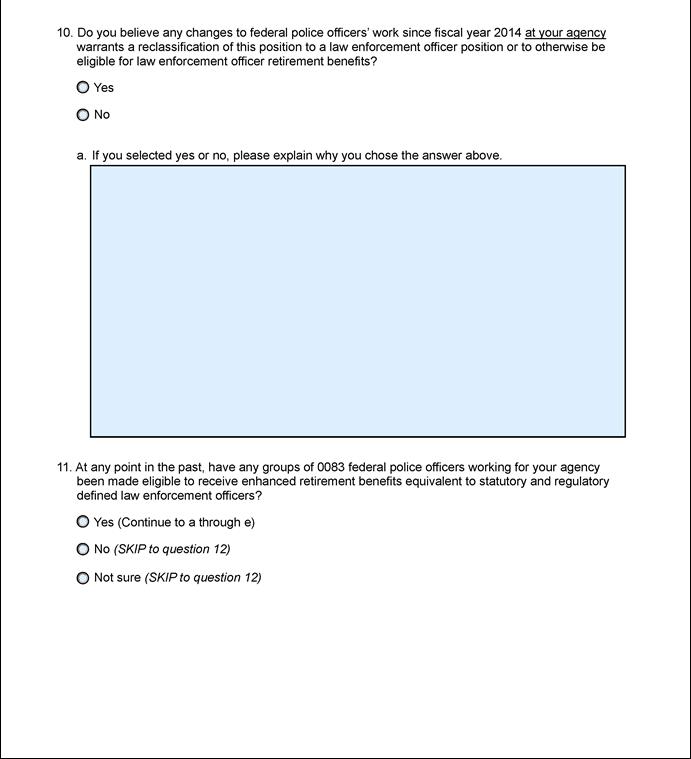

In the past 10 years, none of the eight departments we surveyed had used this process to notify OPM about changes in retirement benefit coverage for their federal police officers.[62] In response to our survey, 10 of the 17 agencies within these departments said changes to federal police officers’ work since fiscal year 2014 at their agency warrants a reclassification of the federal police officer position to a law enforcement officer position or to otherwise be eligible for law enforcement officer retirement benefits.[63] Of those 10 agencies, eight are not currently eligible for enhanced retirement benefits. Two of the eight agencies not eligible for enhanced retirement benefits made a request to their department seeking a change in retirement benefit coverage.[64] Of the remaining six who have not made such requests of their department, reasons provided included not having arrest authority for their federal police officers, still determining whether they have sufficient justification for eligibility, and not understanding the full cost of making the change or the cost would be too great.[65]

Pay. According to OPM, any federal department may make a special pay rate request. OPM may establish higher rates of basic pay for a group or category of General Schedule positions in one or more geographic areas to address existing or likely challenges in recruiting or retaining well-qualified employees.[66] These special rate changes may be made by series, specialty, grade-level, or geographic area, among other things.[67] According to OPM, requests must come to OPM from department headquarters and provide the required data and information, such as specific challenges to recruitment and retention and a description of other pay flexibilities considered.

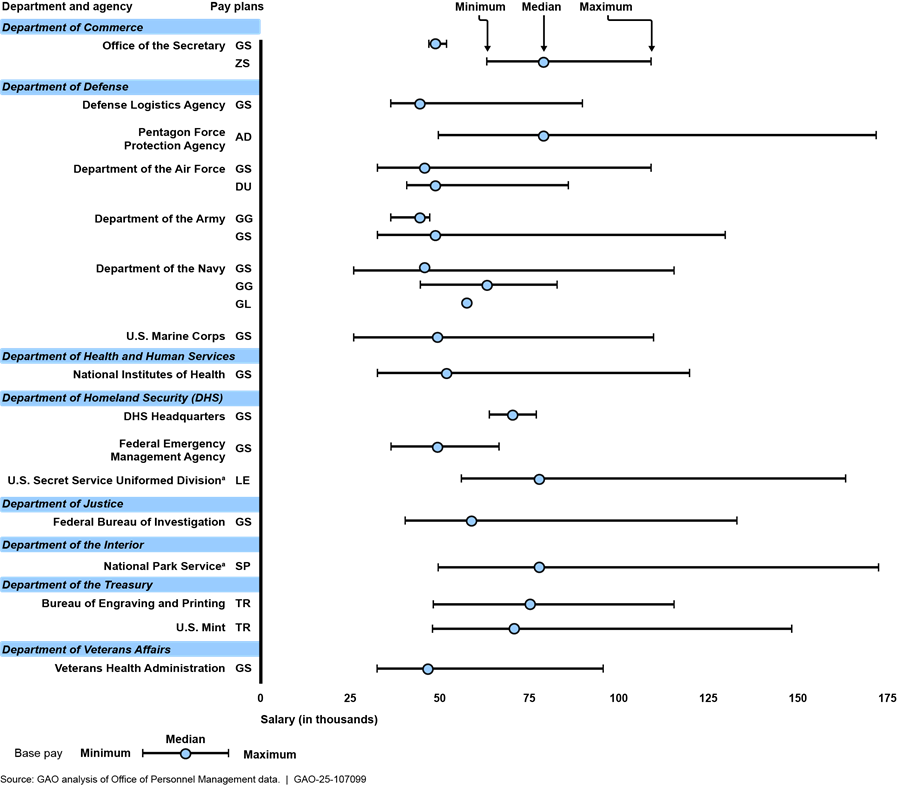

Our analysis of OPM data showed that the federal police at the 17 agencies in our review are on nine different pay plans and various specialized pay rates within some of those plans. When we analyzed the basic pay for federal police officers, we found basic pay varied depending on the pay plan and agency where federal police officers work.[68] The ranges in figure 7 below do not represent the entry-level or maximum possible basic pay. The ranges are for the minimum, median, and maximum basic pay observed in the OPM data for the police officers employed at those agencies at the end of fiscal year 2023.

Figure 7: Comparison of the Minimum, Median, and Maximum Observed Basic Pay for Federal Police Officers by Department, Agency, and Pay Plan at the end of Fiscal Year 2023

Note: According to the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), the pay plan codes are used for agency payroll purposes and are not considered to be acronyms or consistently spelled out in OPM guidance and data standards. Also, because the Department of Interior moved the Bureau of Indian Affairs police officers to a different job categorization in fiscal year 2023, they were removed from this analysis. Minimum basic pay does not refer to starting pay. The minimum and maximum values presented are the lowest and highest basic pay observed in the data for each agency and pay plan. For purposes of OPM’s database, OPM defines “basic pay” as the base rate excluding supplements, adjustments, allowances, differentials, incentives, or other similar additional payments (such as locality payments). Therefore, the pay above does not include locality pay adjustments.

aIndicates agencies that employ federal police officers eligible for enhanced retirement benefits.

According to OPM officials, if a department determines that its federal police officers do not meet the definition of a law enforcement officer for retirement benefits, it may still be able to increase the pay for recruitment and retention needs through special pay plans or OPM-approved special salary rates. Departments and agencies expressed concern regarding the need to remain competitive with federal and nonfederal agencies that can provide higher pay or enhanced benefits for their federal police officers.[69] For example, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs, it has 159 active special salary rate tables for its federal police officers in most localities to better align pay with state, local, and private sector police officer pay, improving its ability to offer competitive pay and recruit and retain police officers. OPM officials also said that legislation has established special pay authorities that apply to several of the agencies in our scope, as well as other federal police forces outside the executive branch. For example, legislation established special pay authorities for the U.S. Secret Service Uniformed Division,[70] U.S. Park Police,[71] the U.S. Mint,[72] the Bureau of Engraving and Printing,[73] and the Pentagon Force Protection Agency.[74]

We surveyed the eight departments in our review to see if at any point since fiscal year 2014 they had used the administrative process to petition OPM for a change in pay for federal police officers.[75] Four of the eight departments responded that they had petitioned and been approved for changes to pay for groups of their federal police officers.[76] For example, in 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services petitioned OPM for a special salary rate for its federal police officers in the Washington, D.C. locality area, citing expanded duties over time and significant problems with recruitment and retention.[77] In 2022, OPM also approved a DHS request for special pay rates for their police officers in the Washington, D.C. locality area.

OPM officials said factors affecting the range of pay for federal police officers include the differences in duties and responsibilities across the various federal police forces, as they can have different missions, roles, skill requirements, and different facilities or populations to protect. OPM officials said it would require considerable resources to carry out extensive data collection and analysis to create a new classification system that properly evaluates the difficulty and responsibility of the work performed across various agencies.

In our survey, we solicited the perspectives from the eight departments about their anticipated need to determine the effect on federal police officers’ current pay plans or their use of special pay provisions at their department if legislation were to designate all federal police officers as statutory law enforcement officers.[78] Because the departments have specialized pay plans and pay rates, several expressed the need to look at the effect more closely and one said it would need to review on an individual officer basis. The Department of the Treasury also said if officers were moved to the GL pay plan associated with statutory law enforcement officers, its federal police officers’ pay would be lower than the department’s current specialized pay plan.

Factors Affecting Agencies, Federal Police Officers, and the Government in Considering Changes to Retirement Benefits and Pay

What are some implementation considerations regarding changes to retirement or pay?

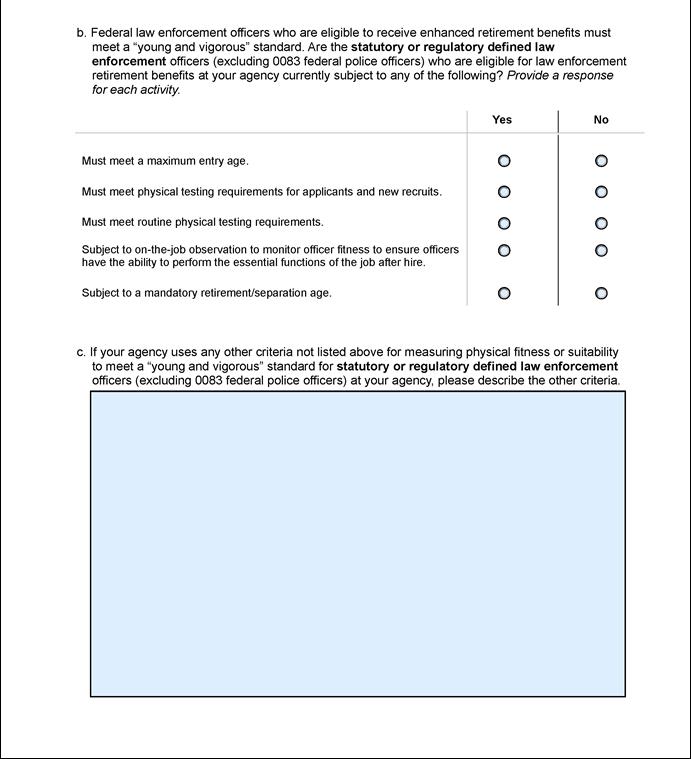

We identified a range of implementation considerations regarding changes to federal police officers’ retirement and pay provisions.[79] These included whether to include past service, whether federal police officers would need to meet certain physical suitability standards, and additional considerations such as opt-in or opt-out provisions.

Retroactive or prospective. OPM’s longstanding policy is that compensation changes should be prospective only, meaning the change would only apply from the point of an enacted legislative change going forward. However, with regard to providing enhanced retirement provisions, it reported that could pose a challenge.[80] That is because, in order to receive the enhanced retirement benefits, statutory law enforcement officers must have completed 20 years of eligible law enforcement service. OPM reported in 2004 that if the enhanced retirement provisions were to be extended to new groups on a prospective basis, employees could have difficulty achieving 20 years of service. For example, federal police officers in the later stages of their career might have to work beyond the otherwise mandatory retirement age of 57 to accrue the 20 years of eligible service if changes were prospective in nature. Consequently, this may not meet the expectation of having a young and vigorous workforce.

As an example of a prospective, or non-retroactive, provision, in 2007, Customs and Border Protection officers were statutorily designated eligible to receive enhanced retirement benefits. However, the law included an express non-retroactivity provision, which meant officers would accrue eligibility for the enhanced retirement benefits from the point of enactment. The law did allow for existing officers to accrue a pro-rated enhanced retirement benefit for years worked after 2008 without having to meet the 20-year service requirement.[81]

By contrast, the three associations we interviewed expressed support for two recent proposals—the Law Enforcement Officers Equity Act and the Law Enforcement Officers Parity Act (2023). The two proposals generally included buy-in provisions that would offer those affected the option to buy back service or deposit a retirement credit to make the benefits retroactive.[82]

Suitability standards. The majority of agencies responding to our survey reported that federal police officers and statutory law enforcement officers employed within their agencies must meet certain physical suitability requirements regardless of the type of retirement benefits they received.[83] For example, 13 of the 17 agencies noted federal police officers must undergo routine physical testing to determine physical suitability.[84] Also, 13 of 17 federal agencies reported they currently do not have maximum entry age limits.

At the department level, we solicited perspectives about departments’ anticipated need to develop or establish a “young and vigorous” standard for federal police officers currently employed if federal police officers were legislatively designated as statutory law enforcement officers.[85] In response, one department stated that requiring annual physical evaluation or assessment standards for federal police officers would ensure the workforce would be more prepared to perform essential functions and effectively respond to emergency situations when needed. However, another department responded that implementing a “young and vigorous” standard would be difficult due to the age of the federal police workforce at that department.

Opt-in or opt-out provisions. Congress could specify opt-in or opt-out provisions through legislation or authorize OPM to implement regulations allowing employees to make informed decisions about special retirement coverage or pay provisions, according to three of eight departments we surveyed.[86] For example, federal police officers could be given the choice to be covered by the new benefit or pay change (“opting in” to the provision) or to remain on their existing benefit or pay plan (“opting out” of the new provision). One department responded to our survey saying it would need to clearly describe for officers the potential effects of opting in or opting out on retirement calculations, career progression, and job responsibilities. Therefore, this department said it would need to provide resources for employees to make informed decisions based on their individual circumstances and preferences.

Opt-in or opt-out provisions related to federal retirement have been used in the past. For example, according to OPM guidance, when FERS became effective in 1987, the legislation included a provision that federal employees with qualifying service under the existing Civil Service Retirement System would have the opportunity to stay on that retirement plan or choose (“opt-in”) to be covered by FERS (the new retirement system).[87]

What are the financial considerations regarding agency budgeting and potential effects on police officers’ FERS benefits?

Changes regarding retirement or pay, including implementation issues, could have budgetary effects on departments and agencies and financial effects on individual officers.[88]

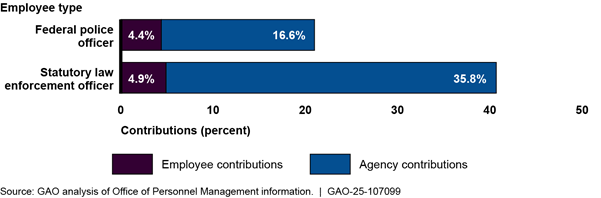

Budgetary considerations. In 2009, we reported that the budgetary resources required by a federal agency for providing enhanced retirement benefits under FERS are higher than providing retirement benefits to regular federal employees.[89] The same holds true today, because the agency contribution for those receiving the enhanced retirement benefits is more than double what the agency contribution is for those receiving the standard FERS benefit. For example, for personnel on the standard FERS retirement plan employed on or after January 1, 2013, agencies contribute 16.6 percent of basic pay to the employee’s FERS retirement. For those eligible for the enhanced FERS retirement, agencies contribute 35.8 percent of basic pay.

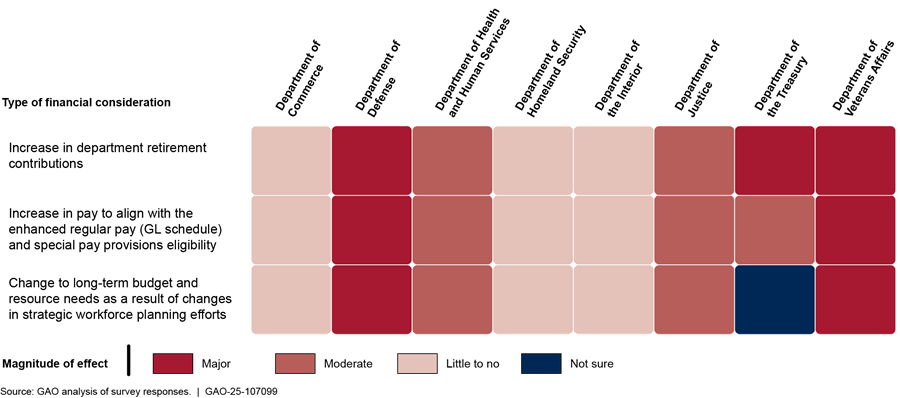

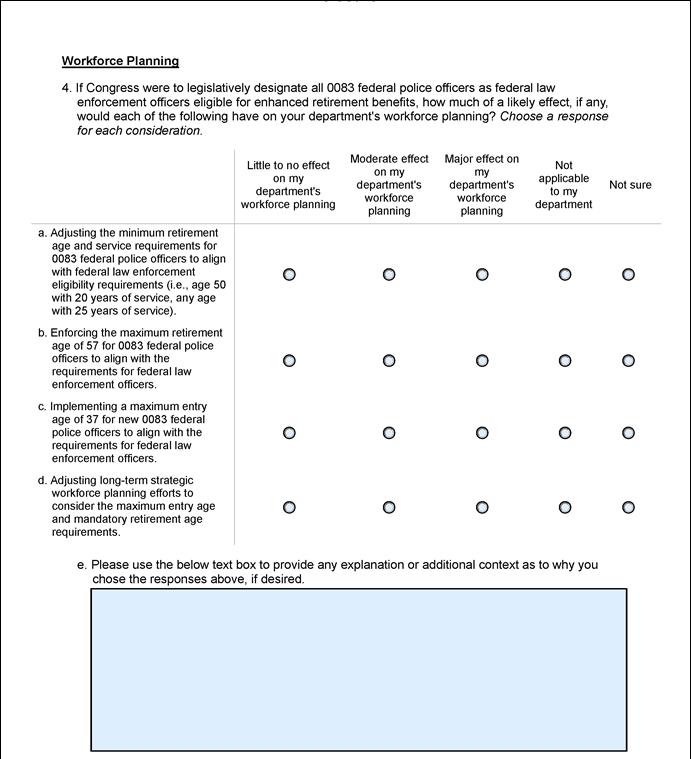

In our survey, responses varied from the eight departments on the magnitude of financial effect various changes would have if Congress were to designate federal police officers as law enforcement officers for the purpose of receiving enhanced retirement benefits. The departments with the largest numbers of federal police officers, the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs, responded that changes in retirement benefits would have a major financial effect and require additional budgetary resources. Department of Veterans Affairs also responded that the change would likely have a significant impact on long-term budgeting and resource allocation. It said the change would necessitate reevaluating staffing levels, training programs, and recruitment strategies to meet the needs of the department. Figure 8 below shows department-level perspectives on the magnitude of financial effect to possible changes.[90]

Figure 8: Department Perspectives on the Magnitude of Financial Effect From Changes in Retirement Benefits

Reasons given for having little to no financial effect were that a department’s federal police officers already received the enhanced retirement benefit or the number of federal police officers at a department was relatively small. However, even a department with few federal police officers across their department recognized that changes could have a significant financial effect for the agencies or offices that directly employ the officers. For example, the Department of Commerce responded that the Office of Security could need about a 15 percent increase in its budget to cover costs associated with a change in retirement benefits.

How changes to retirement or pay are to be implemented could also affect department and agency budgets. For example, if Congress were to provide for retroactive application of enhanced retirement benefits, this could be very costly to departments and agencies, as higher retirement benefits would not have been supported by the lower contribution levels prior to a change. To account for any difference caused by retroactive application, the department or agency may need additional funding.

However, the actual effects on departments’ and agencies’ budgets would depend both on specific legislative provisions as well as agencies’ implementation decisions. For example, the fiscal year 2024 Senate Appropriations Committee report “encouraged the FBI to coordinate with OPM and any other relevant agencies to assist with designating the members of the FBI police as law enforcement officers, and to make the rates of basic pay, salary schedule, pay provisions, and benefits for its members equivalent to the rates of basic pay, salary schedule, pay provisions, and benefits applicable to other similar law enforcement divisions.”[91] OPM officials told us that to provide a cost estimate on retirement benefits, OPM would need to know exactly how FBI proposes to amend retirement benefits for their police officers.[92] Once a proposal is developed, OPM would need information on the number of employees anticipated to be covered by the proposal, their ages, years of service, and their pay to provide cost estimates for changing retirement benefits at the FBI. At the time of our review, OPM and FBI were in contact about the cost estimate, but work was ongoing.

According to OPM officials, to produce a government-wide cost estimate projecting the cost of making federal police officers eligible for the enhanced retirement benefits, it would need workforce data on the affected population from the departments and agencies. This information may need a specific proposal to identify the affected population and information on whether or not the benefits would apply retroactively.[93]

Finally, bills have been introduced in Congress aimed at establishing retirement benefit equity among various federal law enforcement-related positions. However, the Congressional Budget Office said it had not produced estimates, or “scoring,” for these bills because it is not required to do so.[94] These cost estimates could describe the likely effects of proposed changes to retirement benefits for federal police officers on the federal budget. However, these estimates would also include uncertainty and rely on assumptions regarding the population affected.

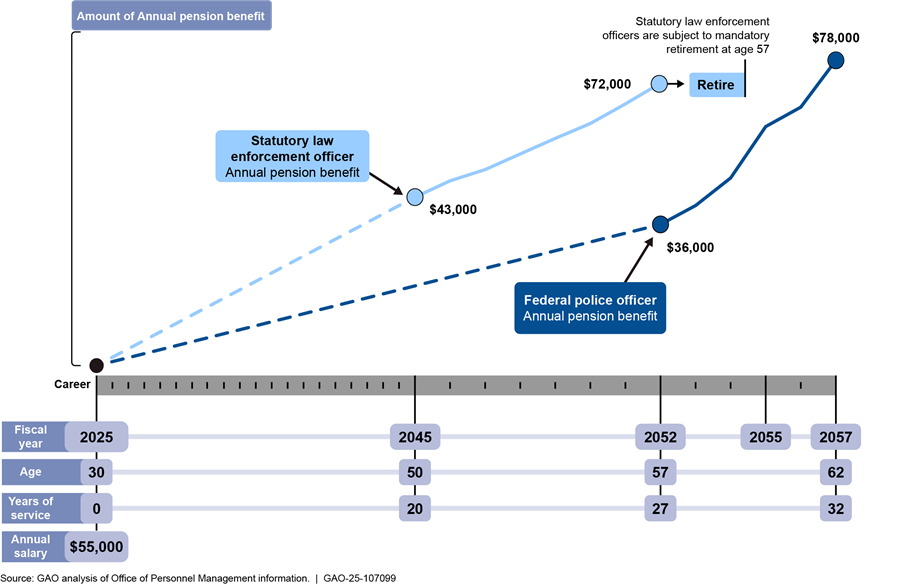

Police officers’ FERS benefits considerations. Changes to retirement and pay would also have financial implications for the employees themselves. The example below illustrates the difference between the standard FERS benefit that many federal police officers receive and what those individuals would have received if they had been eligible for the enhanced retirement benefit (see fig. 9). The illustration assumes a starting salary and standard career progression, highlighting that statutory law enforcement officers receive a higher annual pension benefit at age 57 compared to federal police officers. The federal police officer in this example would need to work past age 61 to attain an annual pension benefit similar to the statutory law enforcement officer who retired at age 57.

Figure 9: Illustrative Projection of Annual Federal Employees Retirement System Annuity Benefits for Employees Entering Federal Service at Age 30, Under the Different Retirement Plans

Note: The annual salary is assumed to increase by 4.7 percent per year, taking into account across-the-board increases, locality pay increases, within-grade increases, and promotion increases. The starting salary and annual increases are based on actuarial valuation assumptions and, as such, are not intended to explicitly model an individual’s projected pay. Rather, the assumptions reflect general expectations for the overall population of active plan participants. Given that the projection extends over more than 30 years, actual pay may vary significantly from the amounts shown here. The calculations account for a pension accrual multiplier for statutory law enforcement officers as 1.7 percent for each year of the first 20 years of service and then 1.0 percent for each year after 20. The multiplier for federal police officers without enhanced retirement benefits is 1.1 percent for each year of service for employees who separate at age 62 or later and have 20 or more years of service. Otherwise, the multiplier is 1.0 percent. The calculations are only for the annuity benefit and do not include Thrift Savings Plan or Social Security benefits.

As shown in figure 10, employees receiving the enhanced retirement benefit have 0.5 percent more of their pay deposited into the FERS pension via employee pay deductions than those who do not have the enhanced retirement.

Figure 10: Difference in Employee and Agency Contribution to the Federal Employees Retirement System

Note: We used current employee and agency annual contribution levels (as of 2022), for employees who entered federal service on or after January 1, 2014.

Those who receive the enhanced FERS retirement are also typically on the GL pay scale, which generally provides enhanced pay relative to the regular GS pay scale. However, as noted above, federal police officers are on nine different pay plans and some of those plans may be higher than the GL pay scale. Therefore, knowledge of individual agency pay plans would be an important part of the decision-making process when considering changes to retirement or pay.

Additionally, certain statutory law enforcement officers are generally allowed to earn premium pay for certain types of overtime that may be added to their basic pay for the purposes of calculating retirement benefits. Therefore, premium pay may be included in an officer’s highest 3 years of earnings used to calculate an officer’s retirement benefits.[95]

However, some groups that receive the enhanced agency contribution to their FERS retirement are not allowed to count premium pay towards their retirement calculation. For example, in response to our survey, the U.S. Secret Service Uniformed Division said its federal police officers work extensive overtime. However, overtime pay is not included in these police officers’ retirement calculations. This is in contrast to the U.S. Secret Service Special Agents (in the OPM 1811 job series) who have Law Enforcement Availability Pay (equal to 25 percent of their rate of basic pay subject to the premium pay cap) counted in their enhanced retirement calculation.

What are the workforce planning considerations regarding changes to retirement or pay?

If Congress made statutory changes to retirement or pay provisions affecting federal police officers, departments and agencies that employ them may have to address administrative changes that could affect workforce planning. These changes may also affect recruitment and retention among federal police and prompt other groups of employees to seek changes to retirement and pay.

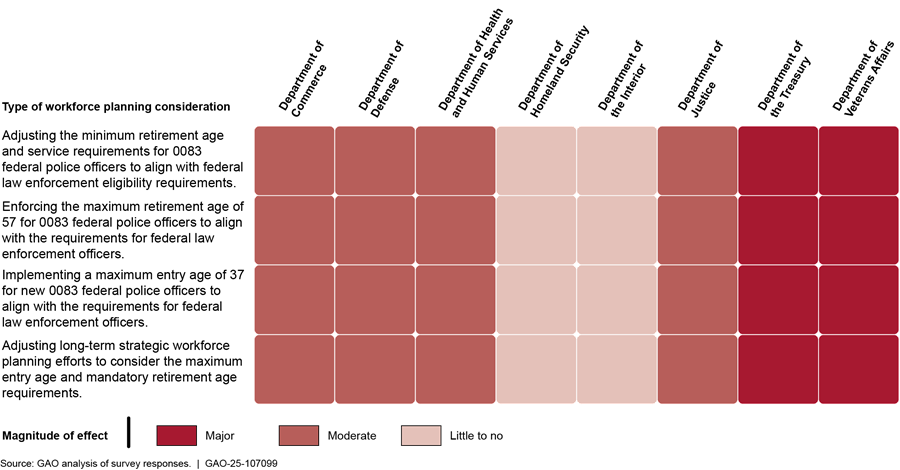

Administrative changes. Depending on the specifics of any statutory changes, agencies may have to adjust age and service retirement requirements, enforce a retirement age of 57, or implement a maximum entry age of 37. For example, one department said its more experienced police officers would potentially be affected by mandatory retirement, which would require backfilling those positions and would drive re-evaluation of existing hiring practices. Another department said changes would necessitate a comprehensive review of recruitment strategies, succession planning, and workforce development initiatives.

Federal police officers without enhanced benefits are not subject to mandatory retirement age requirements and may choose to work past age 57. However, if federal police officers on the standard FERS retirement plan were made eligible for enhanced retirement benefits through legislation, Congress would need to consider the mandatory retirement age and years of eligible service requirements, which federal police officers were not subject to previously. For example, if enhanced retirement benefits were granted to federal police officers on the standard FERS retirement plan in fiscal year 2025, we estimated that at least 14 percent (1,560 federal police officers) may immediately meet or exceed the mandatory retirement age of 57 years old and may not have 20 years of eligible service.[96] If these officers did have the 20 years of eligible service, this could result in the unintended loss of experienced personnel.

As shown in figure 11 below, six of the eight departments anticipated that changes to retirement benefits for federal police officers would have a moderate to major effect on their workforce planning efforts.[97]

Figure 11: Department Perspectives on the Magnitude of Workforce Planning Effects From Changes in Retirement Benefits

Note: “Maximum retirement age” refers to the statutory provision that generally requires federal law enforcement officers to separate from their law enforcement positions at the age of 57 if they have completed 20 years of service.

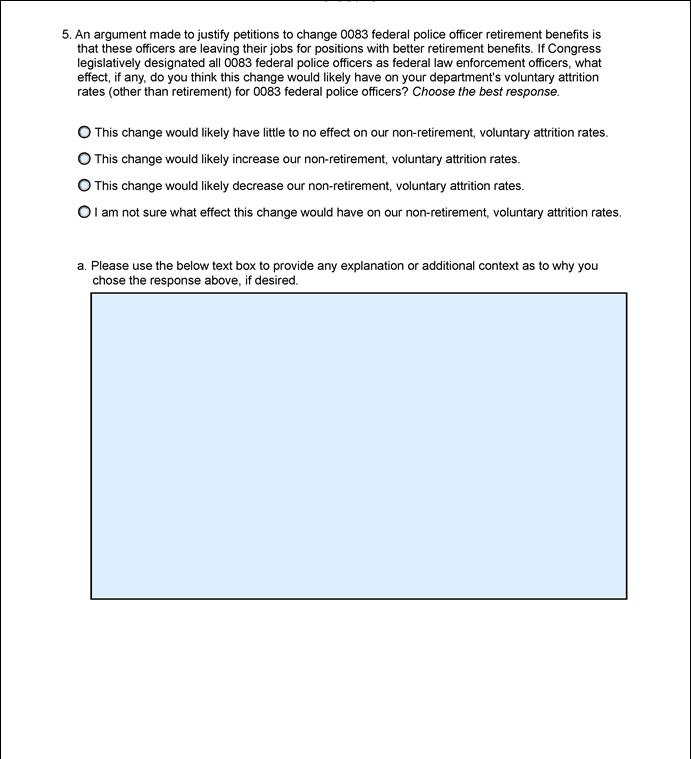

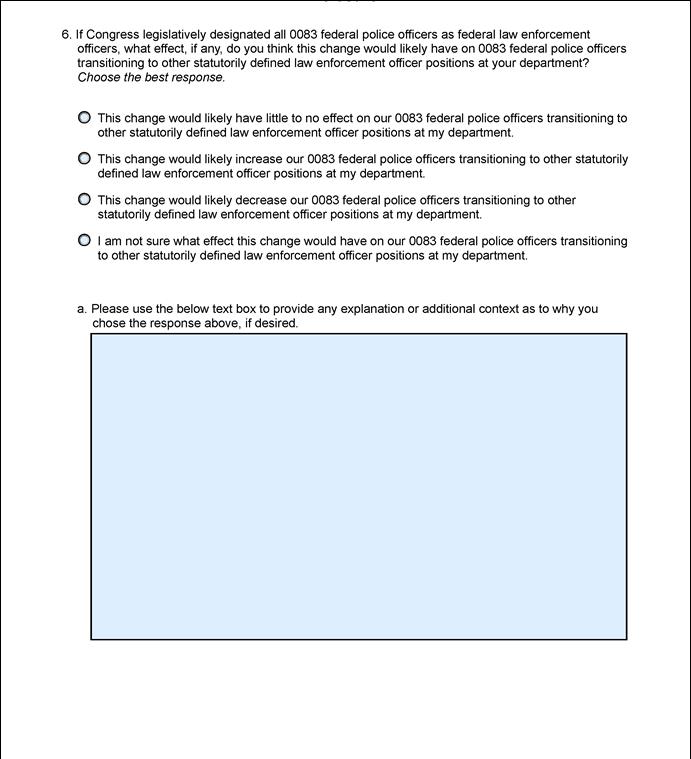

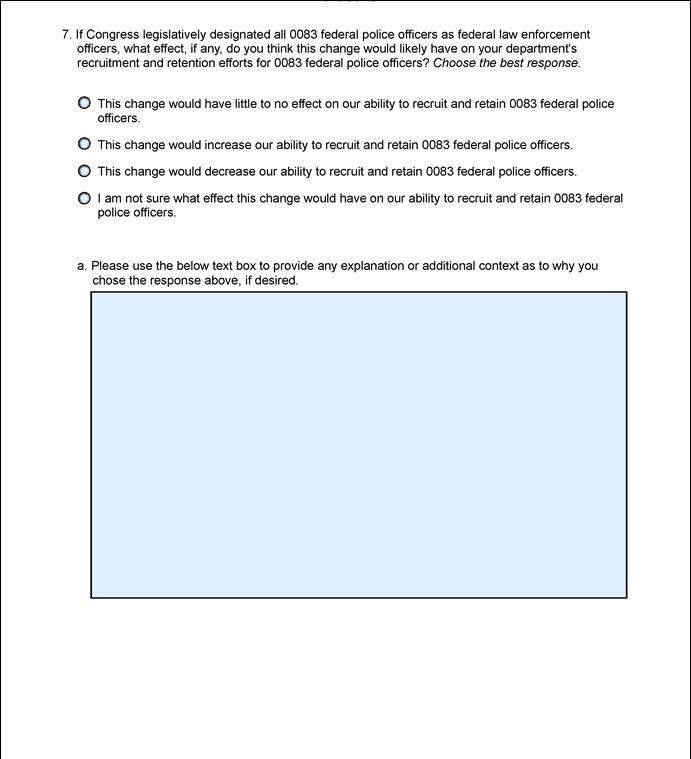

Recruitment and retention. Statutory changes could also affect departments’ ability to recruit and retain federal police officers. As described above, a process already exists to determine changes for retirement or pay, and the departments in our review have used that process to varying extents to accommodate their workforce planning needs. Nevertheless, the ability to recruit and retain federal police officers remains a challenge. For example, all three associations we interviewed stated the recruitment and retention of federal police officers is challenging when agencies compete with other federal agencies or state and local departments offering similar positions with more enhanced retirement benefits.[98]

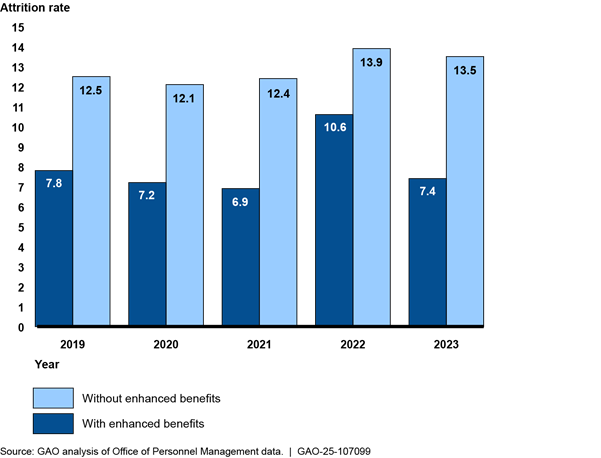

To gain an understanding of recent trends in attrition among federal police officers, we used OPM data to compare the attrition rates of federal police officers with standard FERS retirement benefits to that of federal police with enhanced retirement benefits.[99] While providing important context, our analysis of OPM data is descriptive, and we did not control for any variables. We have previously reported that people leave their jobs for a variety of reasons.[100] Because we did not control for factors that could influence attrition, such as job satisfaction or type of retirement plan, we were not able to isolate potential causes of the differences between police officers with and without enhanced retirement benefits.

As shown in figure 12, we found that between fiscal years 2019 and 2023, federal police officers with standard FERS retirement benefits typically had higher attrition rates than federal police officers receiving enhanced retirement benefits.[101]

Figure 12: Annual Voluntary Attrition Rates for Federal Police Officers With and Without Enhanced Retirement Benefits, Fiscal Year 2019 Through 2023

Note: Bureau of Indian Affairs was excluded from this analysis since its federal police officers transitioned to a different job series in fiscal year 2023.

We also evaluated whether those federal police officers with standard FERS retirement benefits voluntarily moved to a different position within the federal government that had the enhanced retirement benefit. According to our analysis of OPM data, we estimated that 2,725 federal police officers voluntarily transferred to a new position within the federal government between fiscal years 2019 and 2023. Of those federal police officers that voluntarily transferred to another federal position, about 15 percent voluntarily transferred to a position that receives enhanced retirement benefits. The majority of voluntary transfers (85 percent) resulted in federal police officers staying in the same standard FERS retirement plan.

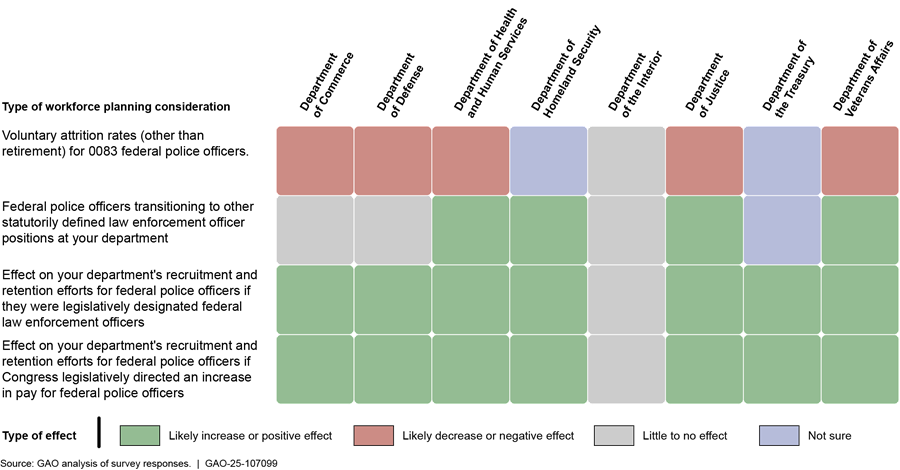

In our survey, we asked departments to consider the likely effects of legislatively designating federal police officers as federal law enforcement officers on various workforce planning issues, such as the effect on departments’ voluntary attrition rates (other than retirement), recruitment and retention, and whether it would make federal police officers more or less likely to take another federal law enforcement position. Figure 13 below shows the departments’ perspectives on these issues.[102]

Figure 13: Department Perspectives on the Magnitude of Effect on Various Recruitment or Retention Efforts If Changes in Retirement Benefits Were Made

The Department of Homeland Security responded that it had uncertainty regarding the effect on voluntary attrition because it did not know if it would have the ability to credit overtime compensation for retirement purposes, and it was unsure if exemptions from the mandatory retirement age would be allowed. The Department of the Treasury responded that an increase in pay would increase its ability to recruit and retain federal police officers. However, it also responded that if officers were moved to the GL pay plan associated with statutory law enforcement officers, its federal police officers’ pay would be lower than the department’s current specialized pay plan, which could negatively affect recruitment and retention.

Even if Congress legislatively designated all federal police officers as federal law enforcement officers for the purpose of receiving enhanced retirement benefits, four of the eight departments responded that they anticipated increases in the number of federal police officers transitioning to other statutorily defined law enforcement officer positions at their department. Reasons they identified included: opportunities for upward mobility and prestige, or to have overtime compensation credited towards retirement. In our prior work, OPM officials stated enhanced retirement benefits are not intended to be a tool for retaining personnel, and that alternative options to address retention challenges may include using human capital tools or leveraging special authorities (e.g., retention incentives or student loan reimbursement) to compete in the labor market for top talent.[103]

Other groups of employees. We also solicited input from the eight departments about whether changes to federal police officer retirement or pay may encourage other groups of employees at their department to seek compensation changes. Two of the eight departments said there was high likelihood other employee groups at their departments would seek compensation changes, and the other departments’ responses were evenly split between having a moderate likelihood and little to no likelihood. The groups (or job series) identified by the departments that may seek compensation changes were: the Federal Protective Service,[104] officials in the Security Administration (0080), Inspection, Investigation, Enforcement, and Compliance (1800 and 1801), and Criminal Investigation (1811) series; and other non-specified groups with similar duties.[105]

Another consideration regarding other groups of employees is that while our work focuses on those departments and agencies that provide employment data to OPM, it does not represent all federal police officers, even within the OPM 0083 federal police officer job series. For example, although outside our scope, we received survey responses from several intelligence agencies within the Department of Defense that would likely be affected by any changes made to retirement and pay for federal police officers.

Concluding Observations

Over the past 2 decades, we and others have reported on the differences in activities, pay, and retirement benefits between federal police officers and statutory law enforcement officers. Additionally, officials from agencies that employ federal police officers, as well as advocacy groups, reported that federal police officers’ work environments are evolving and current retirement benefits or pay structures may no longer align with federal police officer activities and the risks they face. However, due to the wide variation in agency missions and responsibilities, it is not easy to directly compare federal police officer activities to those of statutory law enforcement officers.

Some departments have worked with OPM to adjust pay for federal police officers. Congress has also introduced various legislative proposals to make a variety of changes that would affect pay and retirement for federal police officers. Such changes are complex, and the effects will vary based on the specific proposals. Our work has identified several key considerations regarding implementation, finance, and workforce planning that can serve to inform agencies and Congress as they continue to contemplate additional changes to retirement and pay for federal police officers.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Commerce, Defense, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, the Interior, Justice, the Treasury, and Veterans Affairs; and to the Office of Personnel Management for review and comment. The Departments of Commerce, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and the Office of Personnel Management provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. The Departments of Defense, the Interior, Justice, the Treasury, and Veterans Affairs did not have any comments on the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees; the Secretaries of the Departments of Commerce, Defense, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, the Interior, the Treasury, and Veterans Affairs; the Attorney General, and the Director of the Office of Personnel Management. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at GoodwinG@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Gretta L. Goodwin

Director, Homeland Security & Justice

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for us to conduct a study of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and other agencies that employ General Schedule police officers.[106] This report provides information on three areas related to federal police officers: (1) characteristics of the federal police officer workforce, including their job activities; (2) changes agencies can make regarding retirement and pay; and (3) considerations regarding implementation, finance, and workforce planning to help inform congressional decision making regarding changes to retirement and pay.

Scope

To identify the other agencies that employ police officers similar to those employed by the FBI, we used the Office of Personnel Management’s (OPM) Enterprise Human Resources Integration database (OPM data) to identify the job series for FBI police officers (OPM job series 0083 “federal police officer”) and the other departments and agencies that employ officers in the same job series. Through review of OPM documentation and discussions with OPM officials, we learned that the OPM database only contains information on executive branch departments and does not include information on legislative or judicial branch agencies. According to OPM officials, the OPM data also excludes military personnel, and OPM officials said agencies within the intelligence community do not provide employment data to OPM.[107]

Based on the information in OPM’s database, we identified the following eight executive branch departments employing civilian federal police officers in the 0083 job series: The Departments of Commerce, Defense, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Interior, Justice, Treasury, and Veterans Affairs. Within the eight departments, we identified the following 17 agencies that employ federal police officers: Commerce’s Office of the Secretary, Defense Logistics Agency, Pentagon Force Protection Agency, Air Force, Army, Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, National Institutes of Health, Department of Homeland Security Headquarters, Federal Emergency Management Agency, U.S. Secret Service Uniformed Division, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Park Service, Bureau of Engraving and Printing, U.S. Mint, and Veterans Health Administration.

Data analysis

To identify characteristics of the federal police officer workforce, we used OPM’s database to identify the number of federal police officers in the 0083 job series by department and agency. We limited our counts to federal police officers designated as full-time, non-seasonal, permanent positions. We also limited our counts to those employees receiving Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS) benefits, as there are few employees covered under the Civil Service Retirement System that predated FERS retirement system.

We used fiscal year 2023 data (the most recent available) to calculate descriptive statistics on federal police officers employed by federal departments from OPM’s data. Our counts derived from OPM data are as of September 30th of each year to provide a snapshot focusing on a point in time. According to GAO’s data use agreement with the Office of Personnel Management, data suppression was required for values less than 11. We queried the data to identify the federal police officers by department, location, age, years of service, basic pay, and retirement plan. To provide the most recent data available, we largely used fiscal year 2023 data to calculate the frequency and percentages of federal police officers by department. U.S. Census Bureau’s geographic divisions of the 50 states and District of Columbia was used to provide the location of federal police officers: New England, Middle Atlantic, East North Central, West North Central, South Atlantic, East South Central, West South Central, Mountain, Pacific, and other/U.S. territories.