WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSIT AUTHORITY

Actions Needed to Safeguard Inspector General Independence and Evaluate Capital Investment Outcomes

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-107104

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107104. For more information, contact Andrew Von Ah at (202) 512-2834 or vonaha@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107104, a report to congressional committees.

November 2024

WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSIT AUTHORITY

Actions Needed to Safeguard Inspector General Independence and Evaluate Capital Investment Outcomes

Why GAO Did This Study

WMATA serves a critical function in the national capital region. Its rail and bus system connects residents and visitors to jobs, housing, and essential services. In recent years, WMATA's operations have come under scrutiny, raising the importance of WMATA's oversight.

The IIJA includes a provision for GAO to report on the implementation of reforms to WMATA’s OIG and capital planning process. This report examines (1) how WMATA OIG’s independence compares to key attributes of an independent OIG, and (2) the extent to which WMATA implemented the IIJA’s requirement to develop performance outcome measures for WMATA’s capital investments, among other objectives.

GAO reviewed WMATA documents and compared WMATA’s OIG to attributes of an independent OIG identified by GAO based on the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, and other information. GAO assessed WMATA’s pilot program to measure capital investment outcomes against GAO’s leading practices.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to WMATA, that (1) the Board develop procedures for IG removal, (2) the Board develop a policy to ensure the IG’s direct communication with Congress, and (3) the WMATA General Manager adopt leading practices to assess its measurement of capital investment outcomes. WMATA neither agreed nor disagreed with GAO’s recommendations, but identified actions it plans to take. GAO stands by its recommendations.

What GAO Found

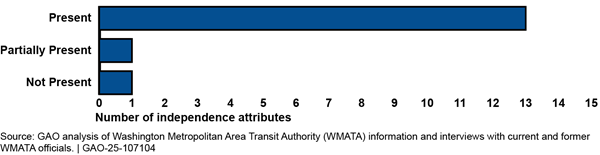

GAO identified 15 key attributes that help ensure the independence of Offices of Inspectors General (OIG). Most (13) of these attributes were present at the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority’s (WMATA) OIG, including the authority to audit and investigate, issue subpoenas, and develop the OIG’s budget. In addition, WMATA has taken actions to carry out the reforms to WMATA’s OIG contained in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), including delegating human resources and procurement authorities to the OIG.

Of the remaining two key attributes of OIG independence, one was not present at WMATA’s OIG and one was partially present.

· Not present: WMATA’s Board of Directors (Board) does not have procedures in place for the removal of an Inspector General (IG), such as advance notice to Congress of a planned removal. Without established removal procedures, an IG may fear termination in response to issuing critical reporting.

· Partially present: The OIG has limited ability to communicate with Congress because the Board has not established a policy that the IG may communicate with Congress at the IG’s discretion. Former WMATA IGs and OIG officials told GAO the Board and management discouraged the IG from communicating with Congress both privately and in public settings, such as hearings. Board officials told GAO the Board has never prevented the IG from communicating with Congress. Without a policy specifying that the IG may communicate with Congress at the IG’s discretion, the OIG will not have assurance that it can inform Congress and respond to Congress’s needs.

The IIJA also contained provisions for WMATA to implement performance measures to assess the effectiveness and outcomes of major capital projects. In 2022, WMATA created a pilot program to measure capital investment outcomes. This program fully met two of five leading practices for the design of pilot programs. This program partially met or did not meet the three remaining leading practices related to 1) a data gathering strategy, 2) criteria to identify lessons learned and inform decisions about scalability, and 3) a data analysis plan to track program performance and evaluate final results. While WMATA is not required to follow these leading practices, adopting them could help WMATA assess whether the pilot program is achieving its objective of measuring the outcomes of capital investments.

Abbreviations

|

AIG |

Association of Inspectors General |

|

APTA |

American Public Transportation Association |

|

COSO |

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations for the Treadway Commission |

|

FTA |

Federal Transit Administration |

|

GAGAS |

Generally accepted government auditing standards |

|

IG |

Inspector General |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

OIG |

Office of the Inspector General |

|

PRIIA |

Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 |

|

WMATA |

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 21, 2024

Congressional Committees

The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) serves a critical function in the national capital region. Its extensive rail and bus system connects residents and visitors across the area to jobs, housing, food, education, health care, essential services, and entertainment. In its fiscal year 2024, WMATA provided an average of nearly 760,000 weekday, non-holiday passenger trips.[1] However, WMATA has experienced a slow recovery from the pandemic, including significant financial hardship with large losses in ridership and revenues. While ridership is recovering, WMATA projected that fiscal year 2025 ridership will be approximately 25 percent below fiscal year 2019, the last pre-pandemic year. As a result, WMATA expects fiscal year 2025 total revenue to be approximately $288 million below pre-pandemic levels.

In addition to fare revenues, WMATA’s operational and capital investment expenses are supported by financial contributions from the communities served by WMATA’s Metrorail and bus lines. WMATA’s fiscal year 2025 capital and operating budget is $5 billion, which covers costs of maintaining WMATA’s extensive rail network, paying employee salaries and benefits, and other costs. Of this amount, $2.8 billion is drawn from Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia and $715.1 million is provided by the federal government. In fiscal year 2025, these regional partners will contribute $463 million in additional funding to help WMATA overcome a $750 million funding shortfall after WMATA exhausted federal pandemic relief funding. While WMATA was able to avoid major cuts to its service in fiscal year 2025, it expects budget shortfalls to continue.

In 2019, we identified several weaknesses in WMATA’s capital planning process that could hinder sound capital investment decisions.[2] In the years since, WMATA has addressed four of the five recommendations in our report, including that WMATA better document its capital planning process.[3] The outcomes of WMATA’s capital planning process are particularly important to WMATA’s continued service to the region.

In recent years, WMATA’s operation and management have come under scrutiny, raising the importance of WMATA’s oversight. WMATA’s Board of Directors (Board) determines WMATA policy and provides oversight for the funding, operation, and expansion of its transit facilities. Additionally, the Board appoints WMATA’s Inspector General (IG). WMATA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) promotes economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in WMATA’s activities, and detects and prevents fraud and abuse. WMATA’s OIG has experienced numerous leaderships changes. The OIG has been led by three different IGs, and one acting IG since 2022. Of these, one resigned in November 2023, saying the OIG’s independence had been compromised and he feared termination in response to issuing a critical report.

In November 2021, Congress and the President enacted the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which identifies specific reforms to WMATA’s OIG and capital planning process. The act makes certain funding contingent on WMATA’s implementation of reforms to its OIG and capital planning process. The IIJA includes provisions for us to report on the implementation of the WMATA OIG and capital planning reforms. This report examines:

1. The extent to which WMATA implemented the reforms to WMATA’s OIG required by the IIJA,

2. How WMATA OIG’s independence compares to key attributes of an independent OIG, and

3. The extent to which WMATA implemented the IIJA’s required reforms to its capital planning process, including IIJA requirements to develop performance outcome measures for WMATA’s major capital investments.

For each of our three objectives, we reviewed federal laws, including the IIJA, and WMATA policies and documents. In addition, we interviewed WMATA officials.

To determine the extent to which WMATA has implemented the IIJA’s OIG and capital planning reforms, we reviewed WMATA documentation and compared WMATA’s implementation of the reforms to the Internal Control-Integrated Framework from the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations for the Treadway Commission (COSO).[4] WMATA uses this COSO Framework as its standard for internal control. Additionally, we interviewed officials from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA).[5]

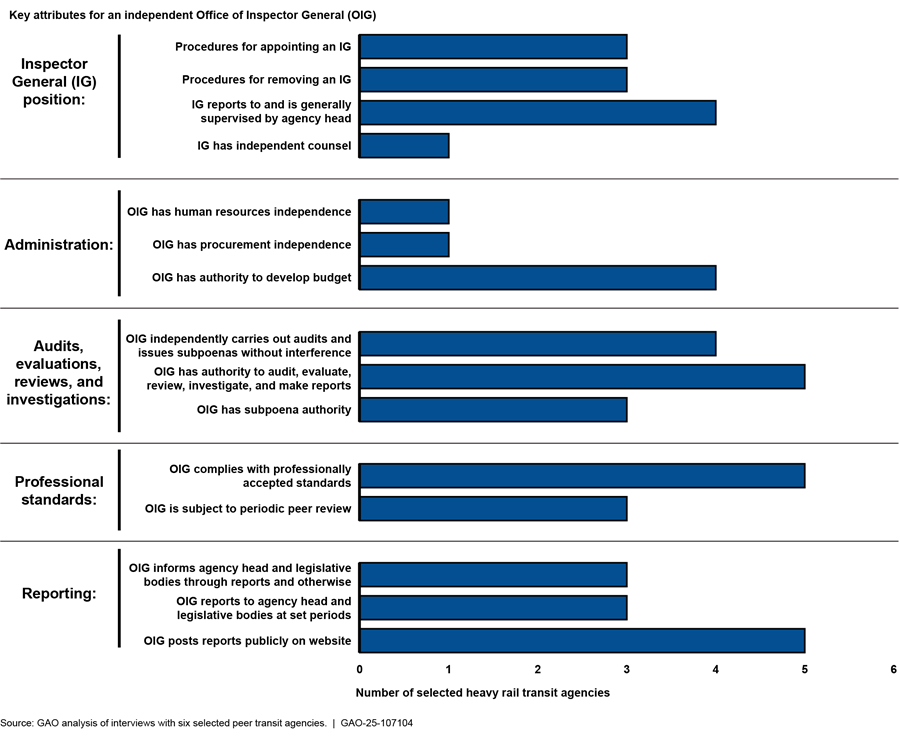

To evaluate how WMATA OIG’s independence compares to key attributes for an independent OIG, we compared WMATA OIG policies and procedures to attributes of OIG independence we identified. We identified these attributes based on the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended (IG Act), IIJA provisions, selected GAO reports, a report from an IG advisory body, and professional standards from an IG professional organization.[6] We also compared WMATA OIG’s policies and procedures to the Association of Inspectors General’s (AIG) Principles and Standards for Offices of Inspector General, which the WMATA OIG uses as its audit standards, and COSO internal control standards. We further compared WMATA OIG policies and procedures to information from interviews with officials at a nongeneralizable sample of six peer transit agencies selected on factors with similarity to WMATA, including operation of heavy rail and the presence of an IG.

To assess the extent to which WMATA implemented the IIJA required reforms to its capital planning process, including IIJA for WMATA to develop performance outcome measures for major capital investments, we reviewed WMATA’s capital planning documents. To assess WMATA’s implementation of specific reforms in the IIJA related to WMATA’s asset inventory and its use of performance measures to assess capital investments, we reviewed WMATA’s procedures for collecting track asset and condition data and interviewed WMATA officials. We also compared WMATA’s pilot program for measuring the performance of its capital investments to GAO’s leading practices for pilot programs. For additional information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

WMATA’s Structure and Office of the Inspector General

The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) is the second largest rail transit agency in the United States. It was created in 1967 through an interstate compact between the states of Maryland and Virginia and the District of Columbia to plan, develop, build, finance, and operate a regional transportation system in the nation’s capital. Congress passed a law authorizing Virginia, Maryland, and D.C. to negotiate and enter into the Washington metropolitan area transit regulation compact. It is governed by a Board of Directors (Board) and has an Inspector General who is appointed by and reports to the Board.

According to WMATA’s Interstate Compact, the WMATA OIG is an independent and objective unit responsible for conducting audits, program evaluations, and investigations of WMATA activities. The OIG promotes economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in WMATA’s activities, and is responsible for detecting and preventing fraud and abuse. Further, the OIG is required to inform the Board about deficiencies in WMATA’s activities and recommend actions to correct them. WMATA OIG’s budget and number of authorized positions has increased since 2020, including after the IIJA’s enactment in 2021 (see Table 1).

Table 1: WMATA Office of the Inspector General’s Budget and Number of Authorized Positions, Fiscal Years 2020 through 2025

|

Fiscal year |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

|

Total budget |

$8,959 |

$10,595 |

$10,474 |

$10,152 |

$12,324 |

$12,001 |

|

Authorized positions |

40 |

44 |

41 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

Source: Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) documents. | GAO‑25‑107104

Note: Dollar amounts are in thousands. Figures for fiscal years 2021 through 2023 represent actual funding and authorized positions. Figures for 2024 and 2025 represent budgeted funding and authorized positions.

WMATA OIG has experienced several changes in recent years, including changes to the IG’s terms of office, and turnover in the position (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Timeline of Office of the Inspector General (OIG) Appointments, Relevant Events, and Policy Changes

The IIJA’s Reforms to WMATA

The IIJA made WMATA’s access to certain federal funds contingent on the implementation of a series of reforms to WMATA’s OIG and capital planning process. Specifically, the IIJA reauthorized the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008’s (PRIIA) capital and preventative maintenance grants to WMATA but made them contingent on certain reforms. These grants provide $150 million annually to WMATA for preventive maintenance and capital improvements for each fiscal year from 2022 through 2030. The IIJA’s reforms included a provision for WMATA’s Board to pass a resolution delegating to the IG the authority to select, appoint, and employ OIG officers and employees (i.e., human resources authority) and contracting officer authority (i.e., procurement authority). Additionally, the IIJA designated $5 million in PRIIA funding for the OIG and required that WMATA designate $5 million in non-federal matching funds for the OIG.

Consistent with recommendations we made to WMATA in our 2019 report, the IIJA’s reforms also required WMATA to implement reforms related to its capital planning process in order to access certain funds. [7] Those reforms include:

· Documented policies and procedures for its capital planning process, including a process aligning projects to WMATA’s strategic goals and a process to develop total project costs and alternatives for all major capital projects;[8]

· A transit asset management planning process that includes asset inventory and condition assessment procedures, as well as procedures to develop a dataset of track, guideway, and infrastructure systems that complies with transit asset management regulations; and

· Performance measures aligned with WMATA’s strategic goals to assess the effectiveness and outcomes of major capital projects.

The IIJA requires the OIG to issue two reports on WMATA’s use of certain funds related to capital improvements and other matters, with reports to be issued no later than 2 and 5 years of the IIJA’s enactment. In November 2023, the OIG issued the first of these reports, which also included information on WMATA’s implementation of IIJA reforms in this report. The report found that WMATA had generally implemented IIJA reforms to WMATA’s capital planning process. However, in the same report the OIG found that WMATA had not implemented all of the IIJA’s reforms to the OIG.[9] Recommendations in the OIG report included that WMATA should update human resources and procurement policies and procedures to reflect the IIJA’s reforms.

Roles of Inspectors General

IGs work at federal, state, and local government levels, and many OIGs adhere to shared professional standards and practices. According to the Association of Inspectors General (AIG), an IG professional group, there are about 200 state and local inspector general agencies nationwide, which take different forms to meet the needs of state legislatures and local governments. These agencies may be established by state constitutions, local charters, statutes, ordinances, or executive orders. AIG officials told us IGs may use their professional experience and judgment to adopt certain quality standards to structure their offices and guide their work, such as AIG’s Principles and Standards for Offices of Inspector General or the Institute of Internal Auditors’ International Professional Practices Framework. According to AIG officials, AIG’s standards are designed to accommodate different types of OIGs and IG roles at the state and local levels.

Most federal statutory IGs are authorized by the IG Act, as amended.[10] The IG Act established IG offices as independent units, which is a fundamental element of IG effectiveness. The IG Act also provides specific protections to enable an effective and independent audit and investigative function for IGs notwithstanding their reporting relationship within the agencies being reviewed. The protections in the IG Act include:

· Constraints on IG supervision and removal. Apart from limited exceptions, the IG Act prohibits agency heads from preventing or prohibiting an IG from initiating, carrying out, or completing any audit or investigation, or from issuing any subpoena during the course of an audit or investigation. Moreover, under the Act IGs generally have the authority to make such investigations and reports as they judge necessary or desirable. Additionally, the IG Act requires that any action removing or transferring an IG must be communicated in writing to Congress at least 30 days beforehand, with an explanation of the substantive rationale for the removal. [11]

· IG authority over OIG personnel. The IG Act gives IGs authority to select, appoint, and employ personnel needed to carry out the functions of the OIG. Further, the IG Act requires that IGs obtain legal counsel from counsel reporting directly to the IG or another IG.

· IG compliance with auditing standards. The IG Act requires IGs to comply with standards established by the Comptroller General of the United States for audits of federal establishments, organizations, programs, activities, and functions. These standards are known as generally accepted government auditing standards (GAGAS).[12]

WMATA is not a federal agency, and WMATA is not subject to the IG Act. However, the 2006 Board resolution establishing the OIG states that it is modeled on a federal OIG in order to support WMATA’s goals of transparency and accountability.

WMATA’s Capital Investment Planning

WMATA’s capital investment planning is administered by WMATA’s general manager, subject to policy direction by the Board. In fiscal year 2025, WMATA plans to spend approximately $2.6 billion for capital improvements and maintenance on its rail and bus assets. WMATA’s capital budget is focused on investments including keeping its assets in a state of good repair, acquisition of the next generation of railcars, known as the 8000 series, and improvements to WMATA’s facilities to accommodate future investments in electric buses and other vehicles. WMATA’s capital budget is distinct from its operating budget, which is funded primarily by the fares it collects and contributions it receives from states and local jurisdictions in which it operates.[13] WMATA’s approved operating budget for fiscal year 2025 is about $2.3 billion.

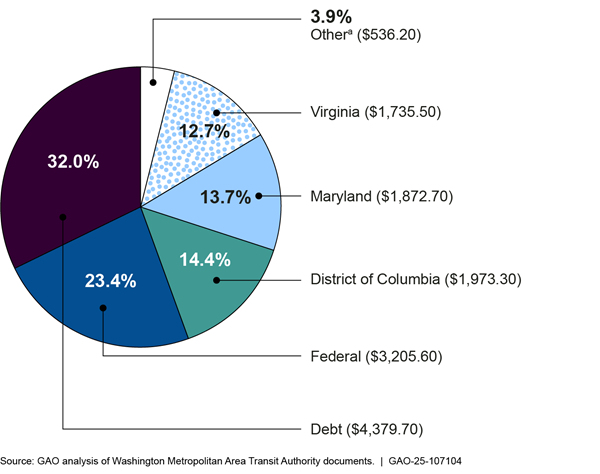

WMATA’s capital investments are funded through multiple sources. WMATA received about $13.7 billion in capital funding for fiscal years 2020 through 2025 (see fig. 2).[14] Of this amount, about 23 percent came from the federal government (about $3.2 billion), and state and local jurisdictions provided about 45 percent (about $5.6 billion). This includes a combined $500 million in dedicated capital funding contributed annually by Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. WMATA also took on about $4.4 billion in debt (32 percent of total funding) to finance its capital program during this period. The federal funding included funding for PRIIA grants reauthorized under the IIJA, as well as other grant awards. As previously described, PRIIA funding under the IIJA included grants providing $150 million to WMATA for each fiscal year from 2022 through 2030.[15] Federal grants under PRIIA are limited to 50 percent of the net project cost with state or local jurisdictions providing additional funds.

Figure 2: Sources of Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Capital Funding, and Debt, in Millions of Dollars, Fiscal Years 2020- 2025

Note: Dollar amounts are in millions.

a”Other” includes various sources of funding, such as reimbursable funding for jurisdiction planning projects.

The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) provides WMATA with funding and direction in the use of federal funds, safety oversight, and transit asset management requirements. FTA provides grants that support capital investment in public transportation, consistent with locally developed transportation plans. FTA regulations require large transit agencies like WMATA to prepare Transit Asset Management plans. These plans contain nine elements, including an inventory of the number and type of capital assets, and a condition assessment of those inventoried assets for which a transit agency has direct capital responsibility.[16] WMATA issued its most recent Transit Asset Management plan on October 1, 2022. This plan describes WMATA’s asset management policy and identifies actions to advance asset management and opportunities for improvement.

In 2019, we reported that WMATA stakeholders (including the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia) did not have reasonable assurance that the agency was following a sound process for making capital investment decisions. We recommended several ways for WMATA to improve its capital planning process, including:[17]

· Establishing documented capital planning policies and procedures. These policies and procedures should include methodologies for ranking and selecting capital projects for funding in WMATA’s fiscal year 2020 capital budget and for the fiscal years 2020-2025 Capital Improvement Program and future planning cycles. In 2022, we confirmed that WMATA had implemented this recommendation by instituting policies and procedures that, taken together, documented its capital planning process, including how projects are prioritized in its capital plans.

· Developing a plan to obtain a complete asset inventory and physical condition assessments. This information should include WMATA assets related to track and structures. In 2021, we confirmed that WMATA had taken several actions that collectively implemented our recommendation.[18] For example, WMATA established guidance and presentations for WMATA project managers on WMATA’s revised capital planning process that emphasized the use of available condition data.

· Developing performance measures. These performance measures should be used for assessing capital investments and the capital planning process to determine if the investments and planning process have achieved their planned goals and objectives. As of September 2024, WMATA has partially implemented this recommendation. In March 2022, WMATA issued a Capital Program Planning Policy. The policy documents the requirements, processes, and staff responsibilities for WMATA to annually develop and update its 10-year capital plan, a 6-year capital improvement program, and an annual capital budget. However, WMATA has not yet developed measures to assess the performance of the overall capital planning process, as we recommended.

WMATA Has Taken Steps to Implement IIJA Reforms to Its OIG

We found that WMATA has implemented policies and procedures for each of the IIJA’s nine provisions for reforming the OIG, including making $5 million in non-federal funds available to the OIG annually through 2030 and delegating contracting officer authority (i.e., procurement authority) to the IG. (See Table 2).

Table 2: WMATA and its OIG have Taken Actions Needed to Carry Out IIJA Reforms Related to its OIG, as of November 2024

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) required reforms related to the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority’s (WMATA) Office of the Inspector General (OIG).

|

IIJA Reform |

Implementation Status |

|

Delegate authority to select, appoint, and employ officers and employees (i.e., human resources authority) to the Inspector General. |

Implementeda |

|

Delegate contracting officer authority to the Inspector General (i.e., procurement authority). |

Implemented |

|

Ensure that the Inspector General is advised by counsel reporting directly to the Inspector General and does not report to WMATA. |

Implemented |

|

Make $5 million in non-federal funding available to the OIG each fiscal year. |

Implemented |

|

Pass a Board resolution adopting the IIJA’s OIG reforms. |

Implemented |

|

Post OIG reports containing recommendations to the OIG website within 3 days after they are submitted in final form to the Board. |

Implementeda |

|

Submit semiannual OIG reports containing recommendations to the Board. |

Implemented |

|

Transmit an aggregate OIG budget estimate and request to the Board each fiscal year. |

Implemented |

|

Transmit the OIG’s semiannual reports on recommendations to Congress. |

Implemented |

Source: GAO analysis of relevant statute and WMATA documents and interviews with WMATA officials. | GAO‑25‑107104

aIn August 2024, GAO presented information to WMATA from a draft of this report, in which we found that WMATA had not fully implemented these two reforms. In September 2024, the WMATA Board took necessary actions to fully implement them, as discussed in this report.

The IIJA required the WMATA Board to resolve to adopt the IIJA’s OIG reforms as a condition of receiving PRIIA funding, which the Board did in a December 2021 resolution. The Board has also taken other steps to implement the IIJA’s requirements. For example, In March 2022, the Board resolved to make $5 million in non-federal funds available to the OIG in each fiscal year. Additionally, Board officials said they began transmitting the OIG’s semiannual report to Congress following the enactment of the IIJA. The Board adopted this requirement in its December 2021 resolution.

According to officials we spoke with, in some cases, the IIJA codified existing WMATA practices. For example, Board officials told us that—prior to the 2021 enactment of the IIJA—the OIG submitted semiannual reports and budget estimates to the Board. OIG officials also said the OIG has employed legal counsel reporting directly to the IG since 2019.

In response to preliminary findings from this report presented to WMATA in August of 2024, WMATA took steps to fully implement two of the IIJA reforms.[19] Those reforms are related to (1) the OIG’s human resources authority and (2) posting reports with recommendations to the OIG website within 3 days after they are submitted in final form to the Board:

· OIG human resources authority. In March 2024 WMATA issued a Staff Notice delegating authority for human resources and procurement decisions affecting the IG to the IG. The Staff Notice was signed by the WMATA General Manager and the Acting IG, and OIG officials told us it was posted to an internal WMATA website accessible to all personnel. However, we found that the Staff Notice was in conflict with an existing WMATA policy, creating ambiguity over the authority of the IG to independently make human resources decisions.[20] The Board resolved this issue in a September 26, 2024 Board resolution. The resolution stated that the March 2024 Staff Notice superseded other WMATA policies that were inconsistent with the Staff Notice. OIG officials also told us that WMATA management has taken additional steps to implement the human resources and procurement reforms since the Staff Notice was issued. For example, officials said WMATA has assigned trained human resources and procurement staff to the OIG and coordinated with WMATA human resources and procurement staff. As a result, we found that WMATA has fully implemented the IIJA requirement for WMATA to delegate authority to select, appoint, and employ officers and employees to the IG.[21]

· Posting reports to the OIG website. The Board’s December 2021 resolution implementing the IIJA’s OIG reforms included a requirement that the IG post all reports with recommendations to the OIG website within 3 days of being submitted to the Board in final form. OIG officials told us they have been able to meet the 3-day time frame to date. However, we found that the Board had an existing policy for accepting OIG reports that could prevent the posting of OIG reports with recommendations within the time frame specified by the IIJA.[22] At a September 26, 2024, Board meeting, Board officials announced the report acceptance process had been revoked as a Board policy. We also found that WMATA had removed information about the acceptance process from its website. OIG officials confirmed for us that OIG reports were no longer required to undergo this process. As a result of this action, we found that WMATA has enabled the OIG to implement the IIJA reform related to posting OIG reports containing recommendations to the OIG website within 3 days after they are submitted in final form to the Board.

WMATA’s OIG Possesses Most Key Independence Attributes, But Gaps Pose Risks to Independence

The WMATA OIG possesses most of the 15 key attributes of OIG independence we identified. However, we found that one key attribute is not present and another is partially present, resulting in gaps that pose risks to the office’s independence.[23] For example, the WMATA OIG has the discretion to independently conduct and supervise audits, program evaluations, and investigations, and to issue subpoenas. However, WMATA OIG faces risks to its independence because the Board has not established policies and procedures for IG removal or to ensure that the IG is able to communicate with Congress as the IG deems appropriate. Table 3 describes the extent to which WMATA’s OIG possesses key attributes of OIG independence identified by GAO, categorized into five issue areas.

GAO identified 15 key attributes to describe independence at the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority’s (WMATA) Office of the Inspector General (OIG).

|

Inspector General (IG) position: The agency should have procedures for appointing and removing IGs, and the agency head should generally supervise the IG. The IG should have authority to obtain legal counsel independent of the agency counsel. |

|

|

Procedures for appointing an IG |

● |

|

Procedures for removing an IG |

○ |

|

IG reports to and is generally supervised by agency head |

● |

|

IG has independent legal counsel |

● |

|

Administration: OIGs should have decisional authority to organize their offices and secure the resources necessary to carry out their duties autonomously and without interference from agency management. |

|

|

OIG has human resources independence |

●a |

|

OIG has procurement independence |

● |

|

OIG has authority to develop budget |

● |

|

Audits, evaluations, reviews, and investigations: OIGs should have full discretion to audit and investigate fraud, waste, and abuse, identify vulnerabilities, and recommend programmatic changes that can strengthen controls or mitigate risks. |

|

|

OIG independently carries out audits and issues subpoenas without interference |

● |

|

OIG has authority to audit, evaluate, review, investigate, and make reports |

● |

|

OIG has subpoena authority |

● |

|

Professional standards: OIGs should comply with professionally accepted standards related to audits, investigations, evaluations, and reviews, and undergo peer reviews on these standards at set periods. |

|

|

OIG complies with professionally accepted standards |

● |

|

OIG is subject to periodic peer review |

● |

|

Reporting: OIGs should have the authority to inform the agency head, legislative bodies, and the public about agency problems and deficiencies through reporting or other means. |

|

|

OIG informs agency head and legislative bodies through reports and otherwise |

◒ |

|

OIG reports to agency head and legislative bodies at set periods |

● |

|

OIG posts reports publicly on website |

●a |

Legend: ● = Present ◒ = Partially present ○ = Not present

Source: GAO analysis of WMATA’s interstate compact, WMATA documents, a report from an IG advisory body, and interviews with current and former WMATA officials. | GAO‑25‑107104

aIn August 2024, GAO presented information to WMATA from a draft of this report, in which we found that these two attributes were not fully present. In September 2024, the Board took steps to ensure the WMATA OIG possessed these attributes.

WMATA OIG Can Independently Conduct Audits and Possesses Other Key Attributes of Independence

We found that 13 of 15 independence attributes are present at WMATA OIG. These independence attributes exist through a combination of provisions in WMATA’s interstate compact, Board bylaws and resolutions, and WMATA and OIG policies and procedures. The attributes are spread across five issue areas, including:

· IG position. Three of the four attributes in this area are present at WMATA OIG. For example, WMATA has procedures in place for appointing an IG, such as establishing qualifications for the IG position in agency policy, developing position profiles for IG searches, and assigning Board members to search committees. Additionally, WMATA’s IG reports to and is supervised by WMATA’s agency head—the Board of Directors—rather than WMATA’s General Manager. Further, as previously described, the OIG has employed legal counsel reporting directly to the IG since 2019.

· Administration. All three attributes in this area are present at WMATA OIG. For example, the WMATA OIG annually develops its own budget estimate for OIG operations based on expenditures it expects to make and funding it expects to receive. The OIG then submits the estimate to the WMATA Finance Department for inclusion in the agency budget as a separate line item, with subsequent review and approval by the WMATA Board. WMATA distributed guidelines for the OIG budget process to all WMATA employees through a Staff Notice in September 2024.

· Audits, evaluations, reviews, and investigations. All three attributes in this area are present at WMATA OIG. For example, WMATA OIG has the authority to independently conduct and supervise audits, program evaluations, and investigations, as well as to subpoena witnesses, papers, records, and documents.

· Professional standards. Both attributes in this area are present at WMATA OIG. For example, WMATA OIG adheres to GAGAS for its performance audits and the AIG Principles and Standards for its investigative, evaluation, and review activities. OIG officials also told us they use the AIG Principles and Standards to standardize OIG practices, policies, and ethics, and to establish professional qualifications, certifications, and development for all OIG staff.

· Reporting. Two of the three attributes within the area of reporting are present at the WMATA OIG. For example, WMATA OIG reports to the agency head and Congress at set periods. This supports OIG independence by creating a channel for external reporting, thereby keeping both the Board and Congress informed about deficiencies in agency programs and operations.

Not all transit agency OIGs that we spoke to possess the independence attributes present at WMATA OIG. For example, officials from five of the six selected peer transit agencies said they did not have legal counsel reporting to the IG, human resources independence, or procurement independence. Officials provided different explanations for this, including agency policy and state laws. Appendix II provides background information and summary results of interviews with the six selected peer transit agencies.

WMATA’s Board Has Not Taken Sufficient Steps to Safeguard OIG Independence, Resulting in Gaps that Pose Risks

We found gaps in WMATA OIG’s independence in comparison with the GAO-identified independence attributes. Specifically, we found the attribute for removing an IG is not present, while the independence attribute related to informing agency heads and legislative bodies is partially present. The WMATA Board has not yet taken action to address these gaps.

· IG removal. In the 2006 WMATA Board Resolution establishing the OIG, the Board stated an intention to develop criteria for IG removal. However, the Board has not established policies or procedures for the removal of an IG. According to WMATA’s interstate compact, the IG serves at the pleasure of the Board, and Board and OIG officials told us the IG can be removed at any time without cause. AIG’s Principles and Standards state that procedures should be established for the removal of an IG only for cause to establish and maintain OIG independence. Some of the six selected peer transit agencies had removal procedures for their IGs. For example, two peer transit agencies told us their agencies require a two-thirds majority vote by their respective boards for IG removal. One of these agencies is required to notify and receive approval from their governor. Procedural safeguards such as a majority vote can prevent IGs from being removed for political reasons or because they have been effective at identifying fraud, waste, and abuse. These requirements are similar to IG Act provisions specifying that certain federal IGs may only be removed through a two-thirds majority vote by members of a board, committee, or commission.

Further, as previously described, the IG Act requires certain agency heads to notify Congress, including the appropriate congressional committees, 30 days before the removal of an IG. Those agency heads are also required to communicate in writing the substantive rationale for removal, including detailed and case-specific reasons, and the details of any open or completed inquiries that relate to the removal or transfer of the IG. As an officer under WMATA’s interstate compact, the IG serves at the pleasure of the Board. The compact does not specify that the IG can only be removed for cause. As previously stated, WMATA is not a federal agency and is not subject to the IG Act. However, the Board’s notification to Congress prior to the removal of an IG could help ensure that an IG removal is based on a clear rationale to safeguard WMATA OIG’s independence.

WMATA Board officials told us that a procedure for IG removal is unnecessary because annual performance reviews are sufficient to determine whether an IG should be removed. However, without established removal procedures, the IG may fear termination in response to issuing critical reporting. For example, a former WMATA IG said he resigned because he believed he would be terminated after issuing a November 2023 report, which found that WMATA had not fully implemented the IIJA’s reforms to the OIG. This former WMATA IG told us the Board responded negatively to the report and that he resigned before he could be terminated by the Board Chair. Establishing policy for the IG’s removal, such as establishing formal procedures for the removal of an IG that include a Board vote and Congressional notification would help safeguard the OIG’s independence.

In a related issue, which WMATA has subsequently resolved, we found that a November 2022 Board decision to change the IG’s terms of office presented risks to OIG independence. In November 2022, the Board passed a resolution changing the IG’s terms of office from a 5-year term with up to two 5-year renewals to a 3-year term with successive 1-year renewals. We found that the annual renewal terms presented risks to the OIG’s independence, in part by potentially leading IGs to avoid undertaking certain work out of concern the Board would not renew their term. We presented this information to WMATA in August of 2024 as part of our process to verify factual information included in this report. In response to this information, the Board passed a resolution in September 2024 that changed the IG’s renewal terms from 1-year renewals to 3-year renewals. As a result of this action, the WMATA OIG should have enhanced assurance to independently pursue the audits and investigations deemed necessary by the IG.

· Informing agency heads and legislative bodies. OIG officials told us that members of Congress, congressional staff, and congressional committees have directly communicated with the IG both in private and at public settings, such as hearings. However, former IGs and OIG officials said the Board and WMATA management discouraged them from proactively communicating with Congress. For example, a former IG told us he had been reprimanded by WMATA management for communicating with Congress about WMATA’s cybersecurity status. AIG’s Principles and Standards state that the IG should prepare work with legislative bodies’ needs in mind. In addition, COSO standards for internal control state that communication between entities, such as WMATA OIG, and external parties, such as Congress, allows for greater understanding of events, activities, or other circumstances.

While the IIJA provided for WMATA OIG to inform Congress through semiannual reports and the Board passed a resolution to adopt the IIJA reforms related to reporting, WMATA does not have a policy to ensure that the IG is able to communicate with Congress as the IG deems appropriate. According to former OIG officials, the OIG’s responsibility to communicate directly with Congress is implicit in the 2006 WMATA Board Resolution establishing the OIG. As previously noted, this resolution states that the OIG is modeled on federal OIGs, and officials said informing Congress is a central duty of federal OIGs.

The WMATA Board has taken some steps to help clarify the OIG communications with Congress, but it has not established a policy to ensure that the OIG has the ability to directly communicate with Congress moving forward. In August 2024, through our process to verify factual information included in this report, we related the concerns of the OIG with communicating directly with Congress. In September 2024, WMATA updated its website to state that the Board’s Executive Committee is responsible for enabling the IG to directly communicate with Congress about findings and recommendations from the OIG. In addition, the Board officials told us the IG is free to communicate with Congress so long as the IG notifies the Board. WMATA Board officials also stated that the Board has never prevented the IG from communicating with Congress. However, in the absence of a clear policy stating that the IG may communicate with Congress at the IG’s discretion, confusion on this issue may continue and the OIG will not have reasonable assurance that it can independently inform and respond to the needs of Congress.

WMATA Has Implemented Asset Management and Capital Planning Reforms, But Could Strengthen Its Program to Assess Investment Outcomes

WMATA Has Established Asset Management Procedures, as Provided by the IIJA

We found that WMATA has implemented the IIJA reforms related to asset management. As a condition for expending amounts from PRIIA grants, the IIJA required WMATA to implement a transit asset management planning process that included asset inventory and condition assessment procedures. The IIJA also required the process to include procedures to develop a dataset of its track, guideways, and infrastructure that complies with transit asset management regulations issued by FTA.

Our review of WMATA documents showed the agency has implemented policies and procedures related to asset inventory and condition assessments:

· Asset inventory. In November 2021 WMATA issued a policy for adding assets to its inventory. In addition, in January 2022 WMATA established standards for preparing asset records and the type of information these records were to contain. It also established standards and procedures for preparing work orders. Our review of documentation found that WMATA had established asset inventory policies and procedures for rail-related departments, including communications and signals and traction power and maintenance.

· Condition assessments. WMATA has also implemented procedures for condition assessments. For example, in June 2022 WMATA established procedures for departments owning assets to prepare Asset Management Lifecycle Plans for their assets.[24] Our review of WMATA documentation found that inspection procedures had been established for rail-related departments such as communications and signals, electrical and traction power systems, and track and structures. WMATA determines asset condition using a variety of methodologies, including visual inspections, modeled data using inspection data and asset age, and fleet management plans.

WMATA has also developed a dataset of its track, guideways, and infrastructure. WMATA uses an enterprise asset management system called Maximo that serves as the database of record for all asset inventory. According to WMATA officials, the agency has several active business systems and mobile applications to support this asset management system and track defects and work management. WMATA officials said these datasets are continuously updated as assets are added, replaced, rehabilitated, or decommissioned and ultimately feed data to or draw data from Maximo. According to WMATA officials, Maximo and its business systems form WMATA’s dataset of track, guideways, and infrastructure.[25]

WMATA officials said they plan to take additional actions to help improve asset information. These include:

· Upgrading Maximo. WMATA officials told us it is necessary to upgrade Maximo because the current version of Maximo will no longer be supported by the manufacturer after 2025, although they said budget constraints and other priorities may delay this project. According to the officials, this upgrade will allow for greater standardization of business processes and work orders, improve long term support for WMATA’s system to manage track assets, and help standardize a mobile application for asset maintenance and inspections.

· Standardizing condition assessment methodologies. WMATA officials said they are also working to standardize condition assessment methodologies across all asset classes. These methodologies would then better align with a computer-based model offered by FTA to transit agencies to forecast capital investment needs over long-time horizons.[26] In general, FTA’s model uses a five-point scale ranging from excellent (5) to poor (1) to assess the condition of assets. WMATA currently uses the five-point scale to assess the condition of its facilities. WMATA officials said they are about halfway through the process of developing a five-point scale that can be applied to all WMATA asset classes. This is expected to be a multi-year project and, according to WMATA officials, will require a significant effort to convert all asset data in Maximo to the five-point condition scale.

WMATA Has Implemented IIJA Capital Planning Reforms Which Should Enhance Transparency of the Process and Increase Accountability for Results

WMATA has also taken action to implement IIJA reforms related to capital planning. We found that these reforms should enhance both the transparency of the process and accountability for results. As a condition to expend certain funds, the IIJA required WMATA to implement documented policies and procedures for the capital planning process. This included documenting a process that aligns projects with WMATA’s strategic goals and develops total project costs and alternatives for all major capital projects.

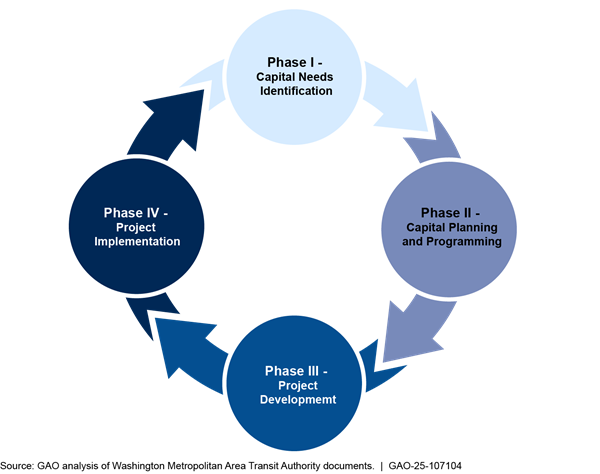

In March 2022, WMATA published a policy documenting its capital planning process and the requirements related to this process. The policy is applicable to WMATA’s Annual Capital Budget, Capital Improvement Program, and forecasted capital investment needs—collectively the framework of WMATA’s capital planning process.[27] The policy established requirements for capital investment plans and budgets, defined the process, and delineated roles and responsibilities for WMATA’s capital program. It also included program accountability and reporting requirements. Further, the policy stated it is WMATA’s goal to prioritize capital investments that are aligned with agency strategic goals. The policy also requires that projects develop total project costs. Finally, the policy states that assessments or business case analyses may be recommended for selected capital investment needs that require further refinement or a review of alternatives to address the need.[28] More information about WMATA’s capital planning process can be found in appendix III.

In May 2022, WMATA published a project cost manual to better ensure total project costs are developed.[29] This manual is intended to ensure a standardized approach is used when identifying and estimating project costs and to ensure that all cost factors are considered, including both direct and indirect costs. Among other things, the manual identifies the roles and responsibilities for preparing cost estimates and provides a template for use in developing and reviewing costs at different stages of project development. Our review of 10 selected capital projects and programs contained in WMATA’s Capital Improvement Program for fiscal years 2025 through 2030 showed the projects and programs included specific agency goals they were intended to support, as well as estimated total project costs.

WMATA documentation also included provisions to better ensure the execution of capital projects and instill accountability for results. This included requirements that capital projects have implementation plans and performance accountability measures. Implementation plans serve as the baseline for project execution and performance monitoring and define the scope, schedule, and total project costs of a capital investment. Under the March 2022 policy, WMATA’s Office of Capital Planning and Program Management is required to monitor and report on the progress of projects against approved implementation plans. Specifically, the policy requires this office to conduct a lessons-learned review or post-operations evaluation of selected capital projects to implement continuous improvements to the capital planning process. The policy does not specify how these projects will be selected and WMATA officials said the lessons-learned reviews and post-operations evaluations are still being developed.

Implementation of the IIJA’s capital planning reforms should enhance the transparency of the process and accountability for results. Externally, the new policies and procedures have acted to increase transparency by making more information about the capital planning process available to the public. For example, capital projects included in the Capital Improvement Program now identify such things as agency goals they are expected to support and total expected costs over the life of the projects. WMATA also publishes quarterly progress reports on its capital projects, which allow the public and others to track the progress of capital projects. Internally, the reforms should increase accountability for results. The March 2022 policy better defines what the capital planning process is, who is responsible for what, and what is expected of participants. Project implementation plans should also better facilitate expectation setting for project managers and establish accountability for achieving project results.

WMATA’s Program to Assess Capital Investment Outcomes Does Not Follow Leading Practices for Pilot Programs and Could Be Strengthened

The IIJA also made the expenditure of certain funds contingent on WMATA’s capital planning procedures including performance measures that are aligned with agency strategic goals to assess the effectiveness and outcomes of major capital projects. In 2022, WMATA created the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program. According to program documents, this program was intended to develop an inventory of performance measures and align those measures with agency strategic goals and objectives, measure investment-specific outcomes, and identify the benefits and effects of capital investments. The program was established as a pilot program and initially identified 10 capital projects—five completed and five ongoing—to develop a proof-of-concept approach for establishing performance measures and outcomes. The proof-of-concept was focused on major capital investments, which were defined as capital projects with a total project cost of $300 million or more or $100 million in federal investment. WMATA subsequently expanded the program to include strategic initiatives and projects with a total project cost of $100 million or more. Following guidance from WMATA’s Board and other sources, the program was further expanded in 2023 (covering the capital plan for fiscal years 2024 through 2029) to include 24 projects and expanded again in 2024 (covering the capital plan for fiscal years 2025 through 2030) to include 40 projects. Program documents indicate WMATA plans to continue expanding investments included in the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program in future years.

In 2016, GAO identified leading practices for the design of pilot programs.[30] These included establishing well-defined, appropriate, and clear objectives and clearly articulating an assessment methodology and data gathering strategy that addresses all components of the program. WMATA officials told us the Capital Performance Outcome Measurement Program was established as a pilot program. WMATA subsequently rolled the program out to include all new capital projects with an investment of $100 million or more and support WMATA strategic goals. However, we found the program continues to exhibit characteristics of a pilot program. For example, the program has not been rolled out to WMATA’s entire capital investment program and WMATA has not conducted an evaluation of the program. WMATA officials indicated they anticipate making improvements to the program as they continue to implement it. As they do so, WMATA would benefit from applying leading practices for pilot programs.

We found that WMATA’s Capital Investment Performance Outcome Program met some of the leading practices for the design of pilot programs, but not all (see table 4).

Table 4: Comparison of Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program Practices to Pilot Program Leading Practices

|

Leading practice |

Status |

|

Establish well defined, appropriate, clear, and measurable objectives |

● |

|

Clearly articulate an assessment methodology and data gathering strategy that addresses all components of the pilot program and incudes key features of a sound plan |

◒ |

|

Identify criteria or standards for identifying lessons about the pilot to inform decisions about scalability and whether, how, and when to integrate pilot activities into overall efforts |

◒ |

|

Develop a detailed data analysis plan to track the pilot program’s implementation and performance and evaluate the final results of the project and draw conclusions on whether, how, and when to integrate pilot activities into overall efforts |

○ |

|

Ensure two-way stakeholder communication and input at all stages of the pilot project, including design, implementation, data gathering, and assessment |

● |

Legend: ● = Met ◒ = Partially met ○ = Not met

Source: GAO‑16‑438 and analysis of WMATA documents. | GAO‑25‑107104

· Establish objectives. WMATA has met this leading practice because the documents underlying the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program established the goal of setting expected performance outcomes for capital investments that contribute to WMATA’s strategic goals and objectives. WMATA officials said they establish performance measures based on factors including a review of implementation plans and scopes of work. These include both quantitative and qualitative measures. For example, quantitative measures include such things as increasing on-time performance of its rail and bus services and reducing costs. Qualitative measures include “improving customer experience and promoting equity.”

· Articulate an assessment methodology and data gathering strategy. WMATA has partially met this practice by establishing an assessment methodology for the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program that includes comparing performance outcomes 1 year before and 1 year after completion of capital investments. However, WMATA has not yet met the leading practice of articulating a data gathering strategy. Leading practices indicate a data gathering strategy would include a clear plan that details the type and source of the data necessary to evaluate a pilot, and methods for data collection to conduct this evaluation, including the timing and frequency. In October 2024, WMATA officials provided us with a document that they described as a data gathering strategy. This document discusses the types of data that WMATA plans to collect (quantitative or qualitative), potential data sources, and data collection methods for assessing individual capital investments. However, the document does not identify specific data that will be needed to evaluate the final results of the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program or a strategy for collecting the necessary data to do this evaluation.

· Identify criteria or standards for identifying lessons to inform decisions about scalability. WMATA has partially met this practice because it has established criteria for scaling up the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program based on whether capital investment projects meet certain dollar thresholds. Specifically, the IIJA required that performance measures, aligned with strategic goals, be developed to assess the effectiveness and outcomes of major capital projects. The FTA generally defines major capital projects as those with a total project cost of $300 million or more, receiving $100 million or more in federal funding, or projects the FTA Administrator determines meet certain criteria.[31] WMATA has included such major capital projects in its Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program and established performance measures for those projects.

However, WMATA has not established criteria or standards for identifying lessons learned to inform its plans to continue expanding investments included in the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program. As we have reported, criteria and standards should be observable and measurable events, actions, or characteristics that provide evidence the pilot objectives—in this case, to measure investment outcomes—have been met.[32]

· Develop a detailed data analysis plan and evaluate final results. WMATA has not met this leading practice because it has not developed a detailed data analysis plan to track the implementation of the program, or a plan to evaluate final results. While WMATA documentation described a general framework for conducting an overall evaluation of the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Program, WMATA has not established a plan for how it will collect and analyze data and conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the program. WMATA officials said they monitor the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program on an annual basis and meet with internal stakeholders to ensure the program is supporting the capital planning process. WMATA has indicated it plans to evaluate the program in 2027.

· Ensure two-way stakeholder communication. WMATA has met this leading practice because program documents indicate that WMATA included stakeholders, such as the various departments that manage WMATA’s capital assets, in developing the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program. In addition, we found that WMATA has used this stakeholder input to shape the program and capital investment performance measures.

We found that WMATA did not fully meet these leading practices because these leading practices are not required within WMATA. WMATA officials told us that in developing the pilot program they contacted other agencies, including transit agencies, to assess how they measure performance of their capital projects. According to WMATA, these contacts were helpful but did not provide a clear path for exactly how this program should be designed. As discussed earlier, WMATA’s capital planning policy requires that performance measures be prepared and included in project implementation plans. However, this policy does not specifically address the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program or a data gathering strategy, criteria or standards for lessons-learned, or a data analysis plan for this program. Program documents we reviewed also did not address these issues.

WMATA officials told us that measuring the outcomes of capital investments is a challenging task, and one they will need to address as they continue to expand the program. Accordingly, WMATA’s Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program could benefit from adopting these leading practices. Specifically, by developing an evaluation plan that includes a data gathering strategy, criteria and standards to identify lessons learned from the pilot, and a data analysis plan, WMATA will have the information to assess whether WMATA’s capital investments, including major capital projects, are achieving their expected outcomes. Without such actions, WMATA will not have the information needed to assess whether the program is achieving its objectives or whether program results can be integrated into the entire capital investment program.

Conclusions

The significant investments made by federal, state, and local jurisdictions into WMATA’s rail and bus system in recent years underline WMATA’s importance to the region’s economy and a shared goal of ensuring WMATA has the resources to continue its recovery from the pandemic. Similarly, the reforms contained in the IIJA to strengthen WMATA’s OIG and enhance its capital planning process further demonstrate the federal government’s commitment to help WMATA better meet and be accountable to the needs of its riders and the region. Because WMATA has implemented the IIJA reforms, it has established a good foundation for enhancing the trust between WMATA and the federal, state, and local jurisdictions that rely on WMATA’s service. However, WMATA’s Board could further ensure the independence of its OIG and engender greater trust between WMATA and the jurisdictions that help fund the system and whose support will be necessary to address WMATA’s future budget shortfalls. Specifically:

· Establishing a Board policy to ensure that the IG can directly communicate with Congress as the IG deems appropriate could help the IG respond to congressional needs.

· Establishing procedures for an IG’s removal to include a Board vote and Congressional notification could provide IGs with confidence to pursue work and issue critical reporting without fear that they will be removed from their position.

WMATA also has opportunities to improve its assessment of capital investments. Applying leading practices for pilot programs to the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program could help WMATA collect the information needed to make program decisions and evaluate whether the program is achieving its objectives. This could in turn improve WMATA’s ability to determine whether its capital investments are achieving their intended outcomes. By taking steps to better safeguard the independence of its OIG and ensure that capital investments are achieving their intended results, WMATA will be better positioned to achieve its strategic goals effectively and efficiently.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of three recommendations, two to the Chair of the WMATA Board of Directors, and one to the General Manager of WMATA.

The WMATA Board Chair should work with the Board members to develop formal procedures for the removal of an IG that include a Board vote and advance notification of Congress, for example by providing Congress with the Board’s rationale for removing the IG 30 days in advance. (Recommendation 1)

The WMATA Board Chair should work with the Board members to establish a policy providing that the IG may communicate directly with Congress about findings and recommendations from the OIG’s work, at the IG’s discretion. This would include communication with committees, subcommittees, members, and staff. (Recommendation 2)

The General Manager of WMATA should adopt leading practices for the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program. This includes (1) preparing and implementing an evaluation plan that clearly articulates an assessment methodology and data gathering strategy for all components of the program, (2) identifying criteria and standards to inform decisions about scalability, and (3) preparing and implementing a data analysis plan to track program progress and facilitate evaluation of final results of the program. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this product to DOT and WMATA for review and comment. WMATA provided written comments that are reprinted in appendix IV and summarized below, as well as technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. DOT had no comments.

In its written comments, WMATA neither agreed nor disagreed with our three recommendations. However, WMATA described some actions it has taken and plans to take related to our recommendations:

Regarding our first recommendation that the WMATA Board develop formal procedures for the removal of an IG that include a Board vote and advance notification of Congress, WMATA said the Board’s existing practice is to take a public vote when making a change to the IG’s appointment, which requires a majority Board vote that is subject to jurisdictional veto. However, over the course of our review, the WMATA Board was unable to provide a written policy describing its formal procedure for removing an IG. In its written comments, WMATA acknowledged the importance of documenting such a procedure in policy, saying that the Board is working to memorialize its existing practice in policy.

Our report also found that a policy requiring the Board to notify Congress prior to the removal of an IG could help ensure that an IG’s removal is based on a clear rationale and help protect the WMATA OIG’s independence. This is particularly important because, as stated in our report, according to WMATA’s interstate compact, the IG serves at the pleasure of the Board, and Board and OIG officials told us the IG can be removed from office at any time without cause. For example, our report states that a former WMATA IG said he resigned in November 2023 because he believed he would be terminated after reporting that WMATA had not fully implemented the IIJA’s reforms to the OIG. Without established removal procedures that include a Board vote and advance notification of Congress with the Board’s rationale for removing the IG, the IG may fear termination in response to issuing critical reporting.

Regarding our second recommendation that the WMATA Board establish a policy providing that the IG may communicate directly with Congress about the OIG’s work, WMATA said the Board’s Executive Committee was responsible for enabling the IG to directly communicate with Congress at the IG’s discretion. In our report, we note that WMATA updated its website in September 2024 to specify that the Board’s Executive Committee is responsible for enabling the IG to directly communicate with Congress about findings and recommendations from the OIG.

While this is a step in the right direction, updates to the Board’s website do not provide a reasonable assurance that these updates will remain in place without an established policy clearly stating that the OIG can directly communicate with Congress, at the IG’s discretion. Our report notes the areas of disagreement on this issue within WMATA. Former WMATA IGs and OIG officials said the Board and WMATA management discouraged them from proactively communicating with Congress, while Board officials told us the IG is free to communicate with Congress so long as the IG notifies the Board. Without an established policy providing that the IG may communicate directly with Congress about findings and recommendations from the OIG’s work, at the IG’s discretion, confusion on this issue is likely to persist. Further, unless this is specified in policy the OIG will not have reasonable assurance that it can independently inform and respond to the needs of Congress.

In its written response, WMATA also recommended revisions to wording in our report, including revising our assessment that WMATA has taken steps to implement IIJA reforms. We believe this language accurately reflects our work which was not a legal compliance audit. We also believe the language accurately reflects WMATA’s actions, including actions taken by the Board on September 26, 2024, in response to findings we presented to WMATA from a draft of this report. Those steps, including revisions to the OIG’s human resources authority and the process for posting reports to the OIG website, are described in this report. Similarly, for the reasons outlined above, we stand by our assessments that the GAO-identified independence attribute for removing an IG is not present at WMATA, while the independence attribute related to informing agency heads and legislative bodies is partially present. By addressing our first and second recommendations in this report, WMATA could help ensure that those independence safeguards are in place.

WMATA’s written comments did not address our third recommendation, that WMATA adopt leading practices for the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program. Applying leading practices for pilot programs to the Capital Investment Performance Outcome Measurement Program could improve WMATA’s ability to determine whether its capital investments are achieving their intended outcomes.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation, the WMATA Board Chair, the WMATA Inspector General, the General Manager of WMATA, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-2834 or vonaha@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Andrew Von Ah

Director, Physical Infrastructure Issues

List of Committees

The Honorable Sherrod Brown

Chairman

The Honorable Tim Scott

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Chairman

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Accountability

House of Representatives

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

This report addresses

1. The extent to which WMATA implemented the reforms to WMATA’s OIG required by the IIJA,

2. How WMATA OIG’s independence compares to key attributes for an independent OIG, and

3. The extent to which WMATA implemented the IIJA’s required reforms to its capital planning process, including IIJA requirements to develop performance outcome measures for WMATA’s major capital investments.

For each of the objectives we reviewed pertinent federal statutes and regulations as well as provisions contained in the interstate compact that created WMATA. We also reviewed applicable WMATA Board of Directors (Board) resolutions and agency policies and instructions from April 2006 to September 2024. Further, we interviewed the Chair and Vice-Chair of the WMATA Board.

To assess the extent to which WMATA has implemented the IIJA’s OIG reforms, we reviewed the IIJA and WMATA documentation such as budget documents for fiscal years 2019 through 2025. Further, we interviewed WMATA officials, including from the OIG and Board, and officials from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA). We assessed WMATA’s implementation of the reforms in comparison to the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations for the Treadway Commission (COSO) Internal Control-Integrated Framework, which WMATA uses as its standard for internal control.[33]

To evaluate how WMATA OIG’s independence compares to key attributes for an independent OIG, we identified such attributes based on the IG Act, IIJA provisions, selected GAO reports, a report from an IG advisory body, and professional standards from an IG professional organization.[34] To develop an initial pool of independence attributes, we reviewed the IG Act.[35] The IG Act is a statute applicable to most federal OIGs that contains statutory elements of OIG independence which protect the objectivity of OIG work and safeguard against efforts to compromise that objectivity or hinder OIG operations. While the WMATA OIG is not a federal OIG—and is not subject to the IG Act—we used the IG Act to identify and select attributes of OIG independence because: (1) the WMATA Board Resolution establishing the WMATA OIG stated that the WMATA OIG is modeled on federal OIGs and WMATA OIG officials affirmed the intent of the resolution;[36] and (2) previous GAO work uses the IG Act to derive attributes to describe the independence of military service IGs and command IGs, which are not subject to the IG Act.[37] To identify independence attributes described in the IG Act, two analysts reviewed the act and identified an initial pool of 21 attributes of independence. A third analyst separately verified this identification.

From this initial pool of 21 attributes, we selected attributes for inclusion in our report if they were also described in at least two out of three other sources on OIG independence: (1) IIJA provisions; (2) at least one of two previous GAO reports on OIG independence;[38] and (3) a report by the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency that describes the authorities, responsibilities, and independence of statutory IGs.[39] To make this selection, one analyst identified that the attributes were described within at least two of the three sources on OIG independence, and a second analyst separately verified this identification. Based on these criteria, we selected 15 of the initial pool of 21 attributes to include in our report. Table 5 shows the 15 selected and six non-selected attributes.

The 21 attributes of Office of the Inspector General (OIG) independence GAO identified in the Inspector General Act of 1978 (IG Act), as amended. The attributes are separated in the table into one group of the 15 we selected for inclusion in this report and a second group of the six we did not select for inclusion in the report.

|

Selected attributes |

|

1. Authority to conduct investigations and make reports |

|

2. Authority to develop budget |

|

3. Authority to select, employ, and appoint employees and officers |

|

4. Cannot be prevented or prohibited from carrying out audits or issuing subpoenas during the course of an audit or investigationa |

|

5. Comply with Comptroller General standards for audits |

|

6. Established appointment procedures |

|

7. Established removal and transfer procedures |

|

8. Independent legal counsel |

|

9. Informing agency head and Congress |

|

10. Posting on website |

|

11. Procurement independence |

|

12. Semiannual reports to agency head and transmitted to Congress |

|

13. Publish the results of any external peer reviewb |

|

14. Subpoena authority |

|

15. Supervision by and report to agency head which maintains operational independencec |

|

Non-selected attributes |

|

16. Authority to administer to or take from any person an oath, affirmation, or affidavit |

|

17. Authority to have direct and prompt access to the agency head |

|