CLOUD COMPUTING

Selected Agencies Need to Implement Updated Guidance for Managing Restrictive Licenses

Report to Congressional Requesters

November 2024

GAO-25-107114

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107114. For more information, contact Carol C. Harris at (202) 512-4456 or HarrisCC@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107114, a report to congressional requesters

November 2024

Cloud COMPUTING

Selected Agencies Need to Implement Updated Guidance for Managing Restrictive Licenses

Why GAO Did This Study

Cloud computing can often provide access to IT resources through the internet faster and for less money than owning and maintaining such resources. However, as agencies implement IT and migrate systems to the cloud, they may encounter restrictive software licensing practices.

GAO was asked to review the impacts of restrictive software licensing on federal agencies. This report (1) describes how restrictive software licensing practices impacted selected agencies’ cloud computing services and (2) evaluates the extent to which selected agencies effectively managed the potential impact of such practices.

To do so, GAO interviewed IT and acquisition officials from six randomly selected agencies and 11 selected cloud investments within those agencies. These investments included a mix of cloud computing types, among other things. GAO also assessed relevant policies and documentation of agency efforts to manage restrictive licensing practices and compared them to key activities for risk and acquisition management identified by industry.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 12 recommendations—two to each agency—to (1) fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices, and (2) assign responsibility for identifying and managing such practices. Five agencies concurred with the recommendations. One agency—DOJ—did not agree with the recommendations. GAO continues to believe its recommendations to DOJ are warranted, as discussed in this report.

What GAO Found

Restrictive software licensing practices include vendor processes that limit, impede, or prevent agencies’ efforts to use software in cloud computing. Officials from five of the six selected agencies described multiple impacts that they had experienced from restrictive software licensing practices. The agencies impacted were the Departments of Justice (DOJ), Transportation (DOT), and Veterans Affairs (VA); the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA); and the Social Security Administration (SSA). Officials from the remaining agency, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), reported that it had not encountered any restrictive licensing practices. The following table summarizes the impacts.

|

Type of impact |

Description of restrictive practice |

Number of agencies experiencing impact |

|

Cost increase (4 agencies) |

Vendor required repurchase of same licenses for use in cloud. |

3 |

|

|

Vendor charged additional fees to use its software on infrastructure from other cloud service providers. |

2 |

|

|

Vendor charged more (e.g., a conversion fee) to migrate its software to the cloud under an agency’s existing licenses used in on-premise systems. |

1 |

|

Limit on choice of cloud service provider or cloud architecture |

Vendor required or encouraged agencies to use its software on that vendor’s own cloud infrastructure (i.e., encouraged vendor lock-in). |

3 |

|

(3 agencies) |

A contractor that migrated an agency’s data into a vendor’s cloud infrastructure required the agency to pay to regain ownership of the data at the end of the contract, which encouraged vendor lock-in. |

1 |

|

|

A vendor for an on-premise private cloud did not allow another vendor’s software to be used with its hardware, thereby creating vendor lock-in. |

1 |

Source: GAO analysis of information provided by agency officials. | GAO‑25‑107114

None of the six selected agencies had fully established guidance that specifically addressed the two key industry activities for effectively managing the risk of impacts of restrictive practices. These activities are to (1) identify and analyze potential impacts of such practices, and (2) develop plans for mitigating adverse impacts. Furthermore, of the five agencies that reported encountering restrictive practices, three agencies partially implemented the key activities to manage those restrictive practices and the other two agencies—DOT and VA—did not demonstrate that they had fully implemented either of the activities.

Key causes for the selected agencies’ inconsistent implementation of the two activities included that (1) none of the agencies had fully assigned responsibility for identifying and managing restrictive practices, and (2) the agencies did not consider the management of restrictive practices to be a priority. Until the agencies (1) update and implement guidance to fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices, and (2) assign responsibility for identifying and managing such practices, they will likely miss opportunities to take action to avoid or minimize the impacts.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CIO |

Chief Information Officer |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

SSA |

Social Security Administration |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 13, 2024

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Chairman

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Joni K. Ernst

United States Senate

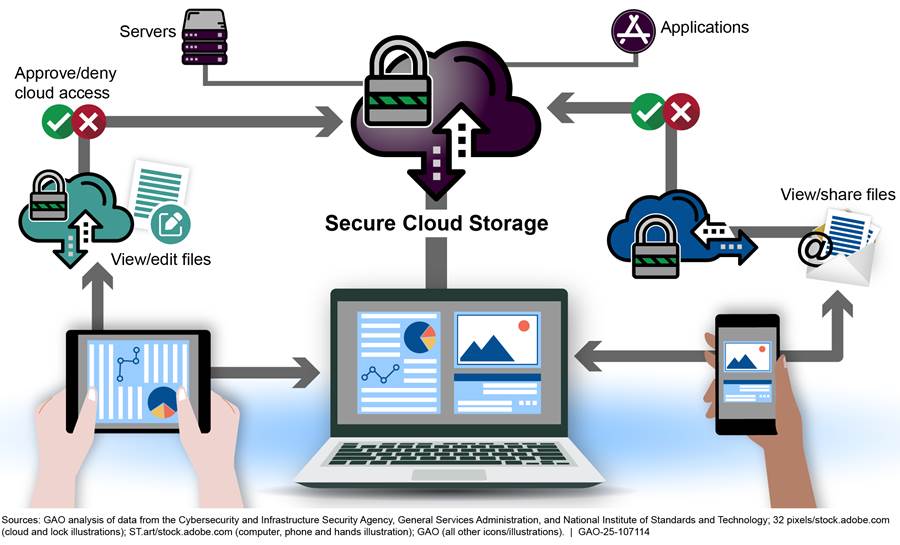

The federal government spends more than $100 billion annually on IT and cyber-related investments. Since 2010, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has required agencies to shift their IT services to a cloud computing option when feasible.[1] The National Institute of Standards and Technology defines cloud computing as a means for enabling on-demand access to shared pools of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications, and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service provider interaction.[2] Cloud computing can often provide access to IT resources—such as servers that store digital files—through the internet faster and for less money than it would take for federal agencies to own and maintain such resources.

Along with its potential to transform agencies’ use of IT, cloud computing also presents specific challenges that may impede agencies’ ability to realize the full benefits of cloud-based solutions. As early as 2012, we reported on the need for agencies to plan carefully as they invested in cloud computing.[3] We noted the importance of preserving agencies’ ability to change vendors in the future by avoiding platforms or technologies that “lock” customers into a particular product (commonly referred to as vendor lock-in).

We have also reported on the impacts of restrictive enterprise software licensing practices on the cost, choice of cloud providers, and other aspects of cloud computing services for selected Department of Defense (DOD) components and investments.[4] In September 2023, we reported that six selected DOD investments we reviewed did not consistently address key industry activities for managing the risk of impacts from restrictive practices, including (1) identifying and analyzing impacts and (2) mitigating those impacts. We recommended that the department update and implement guidance and plans to fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices on cloud computing efforts.

You asked us to review the impacts of restrictive software licensing on federal agencies. Our specific objectives were to (1) describe how restrictive software licensing practices impact selected agencies’ cloud computing services and (2) evaluate the extent to which selected agencies have effectively managed the potential impact of restrictive software licensing practices.

To address both objectives, we selected a stratified random nongeneralizable sample of six agencies for review. To do so, we categorized the 26 federal agencies listed on OMB’s IT Dashboard as small, mid-sized, and large based on their software and outside services spending in fiscal year 2023.[5] We randomly selected two agencies from each size category for review. The six selected agencies were:

· Large: the Departments of Justice (DOJ) and Veterans Affairs (VA);

· Mid-sized: the Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Social Security Administration (SSA); and

· Small: the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

We also selected a nongeneralizable sample of 11 IT investments from the six selected agencies for review. Specifically, for five of the six agencies—DOJ, DOT, NASA, SSA, and VA—we selected two investments from each for review. The final agency—OPM—had only one investment that met our selection criteria, as discussed later. We therefore selected the one applicable investment from this agency. In selecting the investments, we ensured that they included a mix of cloud computing types, cloud service providers, and representation from various agency components.

We also met with relevant officials from OMB to determine whether there were any federal requirements or guidance on managing restrictive software licensing practices. As of June 2024, there were no such federal requirements or guidance. In addition, we interviewed officials from the General Services Administration to obtain background information and context about federal agencies’ experiences with identifying restrictive practices and managing any related potential or actual impacts.

To address our first objective, we conducted structured interviews with cognizant officials responsible for IT, acquisition management, and cloud computing at each selected agency. Specifically, the interviews focused on identifying any restrictive practices and related impacts that the selected agencies had encountered or experienced, and agency and component responsibility and established processes, if any, for managing restrictive practices. To corroborate information that agency officials described, we obtained and analyzed supporting documentation, where available.

To address our second objective, we reviewed ISACA’s Capability Maturity Model Integration v3.0 and selected relevant practices in the areas of acquisition and risk management.[6] We organized the selected practices into two key activities: (1) identifying and analyzing impacts of restrictive practices during the acquisition process and for established IT investments or projects, and (2) developing plans for mitigating adverse impacts. We had also previously assessed DOD’s efforts to implement these two key activities for managing restrictive software licensing practices.[7]

To determine the extent to which the selected agencies had managed the potential impact of restrictive software licensing practices, we obtained and analyzed relevant documentation, such as agency cloud strategies, IT management policies, acquisition management policies, and relevant risk management artifacts, among other things. We then compared this documentation to the two key activities for managing restrictive software licensing practices and their potential impacts.

Further, we interviewed cognizant IT and acquisition management officials from the selected agencies to obtain additional information about responsibility for, and processes for, managing restrictive software licensing practices. See appendix I for a more detailed discussion of our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

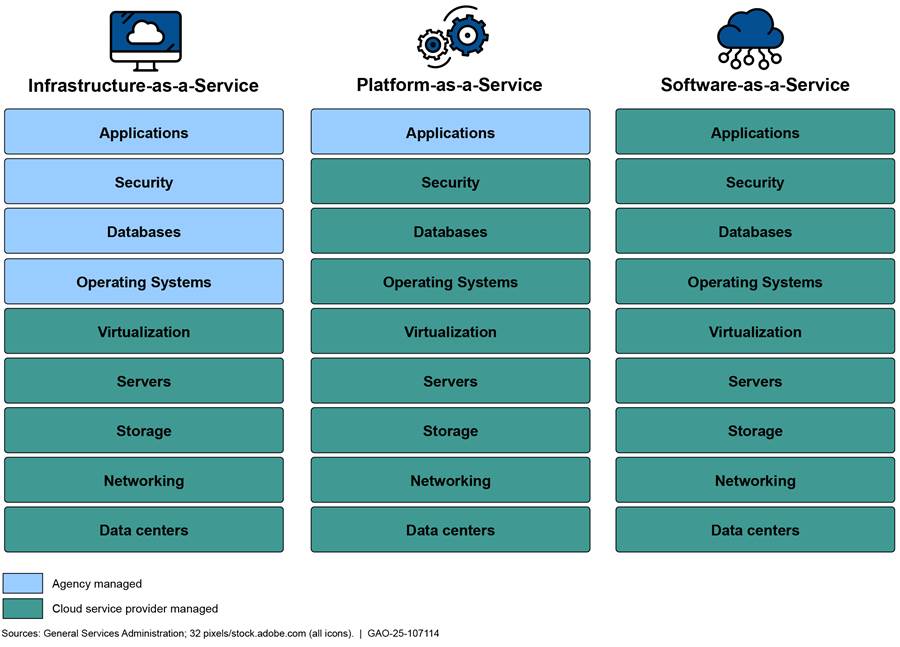

Purchasing IT services through a cloud service provider enables agencies to avoid paying for all the computing resources that would typically be needed to provide such services. As such, cloud computing offers federal agencies a means to buy services more quickly and possibly at a lower cost than building, operating, and maintaining these computing resources themselves. Figure 1 provides an illustration of a cloud computing environment.

Agencies can select different cloud services to support their missions. These services can range from a basic computing infrastructure on which agencies run their own software, to a full computing infrastructure that includes software applications. In defining cloud service models, the National Institute of Standards and Technology identifies three primary models:[8]

· Infrastructure as a Service. The service provider delivers and manages the basic computing infrastructure of servers, software, storage, and network equipment. The consumer provides the operating system, programming tools and services, and applications.

· Platform as a Service. The service provider delivers and manages the infrastructure, operating system, and programming tools and services, which the consumer can use to create applications.

· Software as a Service. The service provider delivers one or more applications and all the resources (operating system and programming tools) and underlying infrastructure to run them for use on demand.

Each type of cloud service offers unique features and carries its own management and security implications that agencies should consider when implementing their cloud systems. For example, agencies have several responsibilities for managing Infrastructure as a Service cloud services, whereas cloud service providers are primarily responsible for managing Software as a Service cloud services. Figure 2 shows the varying responsibilities of agencies and cloud service providers for managing different cloud computing models.

Management of Restrictive Software Licensing Practices

We have previously reported on leading practices for managing software licenses, including the importance of having a centralized management approach for those licenses.[9] Cloud computing adds complexity to the management of such licenses. For example, agencies must track and manage whether, depending on the cloud service model and vendor used, a cloud service includes a license for the agency’s necessary software. Alternatively, the cloud service may be offered as a “bring-your-own-license” model in which the agency may bring its existing, already-purchased software licenses to the cloud platform. In addition, vendors may offer adaptable cloud solutions that allow an agency to scale the number of licenses up or down based on needs. This approach allows an agency to pay only for the licenses used, instead of purchasing a set number of licenses up front that may not be used at all times.

In addition to needing to manage such added complexities of cloud computing licenses, agencies also need to consider restrictive software licensing practices that vendors may have related to the types of cloud services the agencies are acquiring. For example, a software vendor may require the agency to repurchase the same licenses it used on-premise in order to operate the software in the cloud. As another example, a vendor may prohibit an agency from implementing the vendor’s software on infrastructure provided by a different cloud service provider.

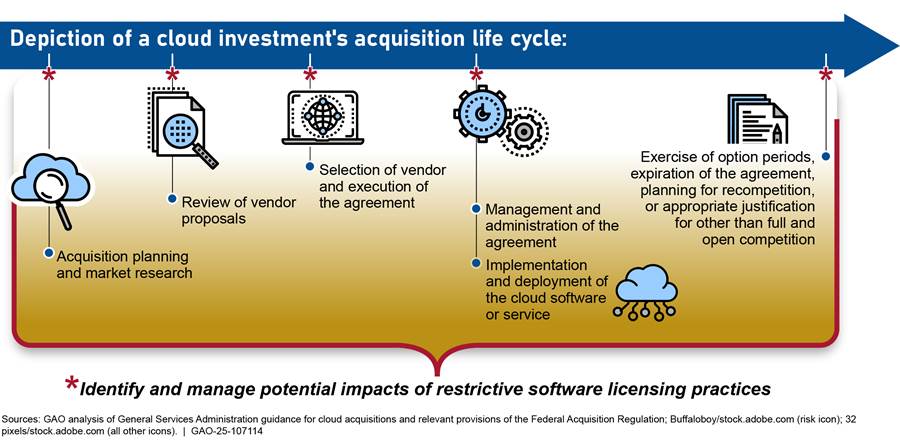

Restrictive software licensing practices may be identified and occur at any point in an investment’s life cycle. If an agency encounters such restrictive practices, it is important for the agency to take effective action to mitigate or avoid potential impacts of those practices, where possible. Figure 3 illustrates how identifying and managing restrictive software licensing practices should occur throughout an investment’s life cycle.

Figure 3: Illustration of How Identifying and Managing Restrictive Software Licensing Practices Should Occur Throughout an Investment’s Life Cycle

As we have previously reported, effectively managing software licenses for cloud computing involves, among other things, applying industry best practices for acquisition and risk management.[10] Key activities for managing impacts of restrictive software licensing practices for cloud computing include (1) identifying and analyzing impacts of restrictive practices during the acquisition process and for established IT investments or projects, and (2) developing plans for mitigating adverse impacts.[11]

Federal Laws and Guidance Related to IT Management and Cloud Computing

As part of a comprehensive effort to transform IT within the federal government, in 2010 OMB began requiring agencies to shift their IT services to a cloud computing option when feasible.[12] Subsequently, in February 2011, OMB issued the Federal Cloud Computing Strategy, which required each agency’s chief information officer (CIO) to evaluate safe, secure cloud computing options before making any new investments.[13]

To reform the government-wide management of IT, in December 2014, Congress enacted the Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act.[14] Among other things, the act strengthens the authority of CIOs to provide needed direction and oversight of covered agencies’ IT acquisitions, which includes acquisitions for cloud services.[15] In June 2015, OMB released guidance describing how agencies are to implement the act.[16] The guidance emphasized the need for CIOs to have full accountability for IT acquisition and management decisions.

In June 2019, OMB issued an update to its Federal Cloud Computing Strategy to accelerate agency adoption of cloud-based solutions.[17] The strategy focused on equipping agencies with the tools needed to make informed IT decisions according to their mission needs. In addition, the strategy included 14 key requirements for agencies to implement within three areas—security, procurement, and workforce—that were intended to help ensure successful cloud implementation.

In 2020 and 2021, the General Services Administration issued guidance for federal agencies on acquiring cloud services.[18] Among other things, this guidance emphasized the importance of establishing service level agreements with cloud service providers.[19] In addition, to assist agencies in planning and managing their cloud computing efforts, the General Services Administration operates the IT Vendor Management Office and supports the Cloud and Infrastructure Community of Practice that is chartered under the Federal CIO Council.[20]

GAO Has Previously Reported on Cloud Computing and Restrictive Software Licensing Practices

As previously mentioned, as early as 2012, we reported on the need for agencies to plan carefully as they invested in cloud computing.[21] We noted that, to preserve their ability to change vendors in the future, agencies may attempt to avoid platforms or technologies that “lock” customers into a particular product (commonly referred to as vendor lock-in).

In addition, in September 2022, we highlighted challenges in four areas that our prior work had shown were impacting the federal government’s adoption of cloud services.[22] Specifically, we reported that agencies faced challenges in procuring cloud services, tracking cloud costs and savings, ensuring cybersecurity, and maintaining a skilled workforce. Among other things, we reported that federal agencies were often using inconsistent data to calculate cloud spending and were not clear about the costs they were required to track. We also reported that agencies had difficulty in systematically tracking savings data and expressed that OMB guidance did not require them to explicitly report savings from cloud implementations. As a result, we reported that it was likely that agency-reported cloud spending and savings figures were inaccurate. In this summary report, we highlighted previous recommendations made in prior reports; we did not make additional recommendations.

In September 2023, we reported on the impacts of restrictive enterprise software licensing practices on the cost, choice of cloud providers, and other aspects of cloud computing services for selected DOD components and investments.[23] We also reported that six selected investments we reviewed did not consistently address key industry activities for managing the risk of impacts from restrictive practices, including (1) identifying and analyzing impacts, and (2) mitigating those impacts. We recommended that the department update and implement guidance and plans to fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices on cloud computing efforts. The department concurred with the recommendation and described plans and time frames for completing actions intended to address it. As of July 2024, the recommendation was not yet implemented.

Further, in January 2024, we reported that agencies faced challenges managing licensing agreements, including those for cloud software and services.[24] We reported, among other things, that federal agencies engaged in thousands of software license agreements each year with vendors to use their products. However, we also reported that certain agencies maintained inconsistent and incomplete data about their software licensing agreements. With limited data, these agencies were challenged in their ability to manage these licenses effectively. We made 18 recommendations to nine agencies to consistently track software license usage and compare the inventories with purchased licenses. Eight agencies agreed with the recommendations and one neither agreed nor disagreed. As of June 2024, the 18 recommendations were not yet implemented.

Most Selected Agencies Described Multiple Impacts from Restrictive Software Licensing Practices

Officials from five of the six selected agencies—DOJ, DOT, NASA, SSA, and VA—identified restrictive software licensing practices that they encountered as part of their cloud computing efforts. Officials from the remaining agency—OPM—reported that the agency had not encountered any restrictive licensing practices.

According to agency officials from DOJ, DOT, NASA, SSA, and VA, the restrictive practices that they encountered included, among other things, a vendor:

· requiring the agency to pay additional fees to use the vendor’s software on infrastructure provided by other cloud service providers;

· charging more for (e.g., a conversion fee) or requiring the agency to repurchase, for use in the cloud, the existing software licenses that the agency had been using in its on-premise systems;

· requiring or promoting vendor lock-in via the cloud service provider’s terms and conditions or acquisition practices;[25] and

· lacking accurate or sufficiently detailed cost data to support agency planning for moving on-premise licenses to the cloud.

Officials from these five agencies reported that the restrictive practices generally impacted their (1) cost of cloud computing and (2) choice of cloud service provider or cloud architecture. In addition, officials from multiple selected agencies reported that they had encountered the same restrictive practices, while other practices were specific to a selected agency’s software vendor, type of software, or cloud service provider. Table 1 summarizes the impacts that officials from the selected agencies described related to the restrictive practices they had experienced, as well as the number of agencies that reported experiencing each impact.

|

Type of impact |

Description of restrictive practice |

Number of agencies that reported experiencing impact |

|

Cost increase |

Vendor required repurchase of same licenses for use in cloud. |

3 |

|

(4 agencies) |

Vendor charged additional fees to use its software on infrastructure from other cloud service providers. |

2 |

|

|

Vendor charged more (e.g., a conversion fee) to migrate its software to the cloud under an agency’s existing licenses used in on-premise systems |

1 |

|

Limit on choice of cloud service provider or cloud architecture |

A vendor required or encouraged agencies to use its software on that vendor’s own cloud infrastructure. This is an example of encouraging vendor lock-in. |

3 |

|

(3 agencies) |

A contractor that migrated an agency’s data into a vendor’s cloud infrastructure required the agency to pay to regain ownership of the data at the end of the contract. This is an example of encouraging vendor lock-in. |

1 |

|

|

A hardware vendor for an on-premise private cloud did not allow another vendor’s software to be used with its hardware. As a result, the agency investment that had implemented that vendor’s private cloud was effectively locked in to using the vendor’s software, hardware, and support. |

1 |

Source: GAO analysis of information provided by agency officials. | GAO‑25‑107114

· Cost impacts. Officials from four of the six selected agencies—DOJ, DOT, NASA, and VA—described cost increases that they had experienced or expected to experience as a result of restrictive software licensing practices on their cloud computing efforts. Specifically, according to agency officials:

· Licensing costs increased. Four vendors required agencies to repurchase the same licenses that they had been using on premise, in order to use the licenses in the cloud. Officials from three agencies reported experiencing this impact, but they were unable to specify the actual amount of increase for repurchasing the licenses.

· Infrastructure costs increased. Two vendors charged additional fees to use their software on infrastructure from third party cloud service providers. Officials from two agencies reported experiencing this impact. One of these agencies had not tracked the additional costs attributable to the restrictive practice. As such, it was unable to specify the actual amount of increase. Officials from the other agency stated that, as of July 2024, they were in the process of working with the vendor to determine what the additional costs will be.

· Acquisition costs increased. One vendor required an agency to pay a conversion fee to change a license from use on premise to use in the cloud. However, officials from this agency were unable to specify the actual amount of increase associated with the conversion fee.

· Impacts on choice of cloud service provider or cloud architecture. Officials from three of the six selected agencies—DOJ, NASA, and SSA—described impacts of restrictive software licensing practices on their choice of cloud service provider or architecture. Specifically, according to the officials:

· A vendor required or encouraged three agencies to use the vendor’s software on that vendor’s own cloud infrastructure. This is an example of vendor lock-in.

· Another instance of vendor lock-in involved a contractor that migrated an agency’s data into a vendor’s cloud infrastructure, requiring the agency to pay to regain ownership of the data at the end of the contract.

· A hardware vendor did not allow software from another vendor to be used on its hardware. Specifically, officials from one agency explained that the hardware selected for an investment’s on-premise private cloud service did not allow another vendor’s software to be used on it. Investment officials stated that the agency selected the hardware for the private cloud nearly a decade ago. The officials added that, as of July 2024, they were working to implement a hybrid cloud environment with other commercial cloud service providers. However, the investment must continue to use the same software and hardware vendor for its private cloud.

The five agencies that reported they had encountered restrictive practices—DOJ, DOT, NASA, SSA, and VA—also took specific actions that may have limited their exposure to potential impacts from restrictive practices.

· Officials from each of these five agencies reported that the agencies established enterprise-wide cloud contracts with multiple service providers. This structure may enable investments facing a restrictive practice from one vendor to use another cloud service provider that does not have such a restrictive practice.

· Officials from two agencies reported that their agencies purchased licenses from different providers rather than acquiring licenses directly from the original vendors. The officials explained that the original vendors had imposed restrictive practices on the licenses. By considering and selecting alternative solutions that did not include such restrictions, the agencies were able to avoid potential impacts from the restrictive practices.

· Officials from one agency reported that it negotiated terms in a contract that enabled it to avoid cost increases associated with a vendor’s restrictive licensing practices. For example, agency officials stated that one component had to repurchase the same licenses that it had been using on premise, in order to use the licenses in the cloud. However, the officials explained that, because the agency had negotiated other terms as part of the contract, it had mitigated the cost of repurchasing the licenses. As such, the officials stated that there was not an overall cost increase from the restrictive practice.

· Officials from one agency reported that it decided to maintain an existing on-premise system instead of moving it to the cloud, in order to avoid a cost impact from a restrictive licensing practice associated with a particular cloud service. Specifically, the officials stated that to use the cloud solution they would have had to repurchase the existing software licenses that the agency had been using in its on-premise system for use in the cloud.

Officials from the other selected agency—OPM—stated that the agency had not encountered restrictive practices in managing its cloud computing efforts. These officials explained that the agency has used multiple providers for its cloud-based applications and services. However, when developing new cloud applications and systems and migrating on-premises systems to the cloud, the agency attempts to consolidate these services in its enterprise cloud environment, which is operated by one vendor. By using the enterprise cloud environment and its single provider, the agency may have minimized the likelihood that it would experience restrictions in establishing cloud computing services.

However, OPM’s effort to consolidate its cloud applications and services in its enterprise cloud environment using one cloud provider increases the risk that the agency effectively locked itself into that cloud service provider. For example, officials from other agencies reported that their agencies were effectively locked in with certain large cloud vendors because of the substantial enterprise infrastructure services contracts they had established with selected vendors. The officials noted that this lock-in was not due to any explicitly documented restrictive terms and conditions. However, because the agencies configured their software to work with those specific providers, the officials stated it would be cost prohibitive to change from those configurations to different cloud service providers in the future.

Selected Agencies Did Not Effectively Manage Impacts of Restrictive Practices

Effectively managing software licenses for cloud computing involves, among other things, applying industry best practices for acquisition and risk management.[26] Key activities for managing impacts of restrictive software licensing practices for cloud computing include (1) identifying and analyzing impacts of restrictive practices during the acquisition process and for established IT investments or projects, and (2) developing plans for mitigating adverse impacts.

None of the six selected agencies had established guidance that specifically addressed the two key activities for managing impacts of restrictive software licensing practices. Moreover, of the five agencies that reported encountering such practices—DOJ, DOT, NASA, SSA, and VA—none had fully implemented the two key activities to manage those practices. Without updating and implementing guidance for managing impacts from such practices, and prioritizing management of them by assigning responsibility to do so, agencies face increased risk that investment teams’ efforts to manage such impacts will not be effective.

Selected Agencies Did Not Establish Guidance That Fully Addressed Key Activities for Managing Restrictive Practices

None of the six selected agencies had fully established guidance that specifically addressed the two key activities for managing restrictive software licensing practices. Four of the agencies—DOJ, OPM, SSA, and VA—did not have any guidance that addressed the two activities, while the other two agencies—DOT and NASA—had partially developed such guidance.

In particular, one of DOT’s components—the Federal Aviation Administration—had developed procurement guidance that, among other things, directed the component’s contracting officers to review contracts for commercial software licenses to determine whether they include terms and conditions that attempt to charge the agency additional licensing fees or restrict the use of software to specific machines or network locations. However, this guidance—which was only applicable to the component and not department-wide—did not address analyzing or mitigating potential impacts of such terms and conditions. The guidance also did not specifically address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating impacts of other types of restrictive licensing practices. Further, DOT did not establish other guidance for use across the agency that was specifically intended to identify or manage potential impacts of restrictive software licensing practices.

With regard to NASA, the agency had developed guidance outlining cloud procurement best practices for use when acquiring Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program-authorized commercial cloud services.[27] One of the identified best practices was to reduce the risk of vendor lock-in (a type of restrictive practice) by ensuring that the statement of work for NASA’s cloud services specifies the approach that it would take if the agency chooses to transfer the delivery of cloud services under the contract to a different reseller, another entity, or to NASA itself. However, this guidance did not address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating other types of restrictive practices.

Officials from each of the six selected agencies stated that they would manage restrictive practices as risks. However, none of the agencies provided supporting documentation demonstrating that such practices are to be managed as risks. Officials from these agencies also stated that their agencies’ existing IT and acquisition management policies and procedures could be used to help identify and manage restrictive practices and their potential impacts. However, none of the agencies were able to identify parts of these policies and procedures that specifically addressed identifying, analyzing, and mitigating impacts from such practices.

Selected Agencies Did Not Consistently Implement Key Activities for Managing Impacts of Restrictive Practices

The five selected agencies that reported they had encountered restrictive licensing practices—DOJ, DOT, NASA, SSA, and VA—did not consistently implement the key activities for (1) identifying and analyzing impacts of restrictive software licensing practices during the acquisition process and for established IT investments, and (2) developing plans for mitigating adverse impacts. Three of the agencies—DOJ, NASA, and SSA—partially implemented the key activities. The other two agencies—DOT and VA—did not implement the key activities. Table 2 depicts the extent to which the selected agencies implemented the two key activities for managing potential impacts of restrictive practices.

Table 2: Assessment of Selected Agencies’ Implementation of Key Activities for Managing Restrictive Software Licensing Practices

|

Selected agency |

Identified and analyzed potential impacts of restrictive licensing practices |

Mitigated impacts from restrictive licensing practices |

|

Department of Justice |

◐ |

◐ |

|

Department of Transportation |

○ |

○ |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs |

○ |

○ |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

◐ |

◐ |

|

Social Security Administration |

◐ |

○ |

Legend: ◐ = Partially implemented; ○ = Not implemented

Source: GAO analysis of information provided by agency officials. | GAO‑25‑107114

· Regarding the first key activity, DOJ, NASA, and SSA partially identified and analyzed the potential impacts of restrictive practices. Specifically, each of these agencies documented certain restrictive practices and analyzed their potential impacts. However, DOJ and NASA did not conduct such analyses for all restrictive licensing practices that they reported they had encountered. In addition, with regard to their selected investments, officials from SSA’s two investments stated that they did not take action to identify any restrictive practices that could have impacted those investments. As such, those investments had not identified or analyzed any such practices nor potential impacts. Officials from the two selected NASA investments and the two selected DOJ investments reported that they took action to identify restrictive practices while conducting market research or during their reviews of vendor proposals when moving to the cloud; however, none of these officials provided documentation demonstrating that they analyzed potential impacts of the practices they identified.

The two other agencies—DOT and VA—did not demonstrate that they analyzed the potential impacts of the restrictive practices they encountered. Officials from these agencies told us that they would manage restrictive licensing practices as risks and these agencies’ risk management policies called for them to analyze the potential impacts of risks. However, as discussed earlier, neither DOT nor VA provided supporting documentation demonstrating that such practices are to be managed as risks. They also did not provide documentation demonstrating that they had analyzed the potential impacts of the restrictive practices they experienced.

Moreover, with regard to their selected investments, officials from DOT’s two investments and one VA investment reported that they did not take action to identify any restrictive practices that could have impacted those investments. As such, those investments had not identified or analyzed any such practices nor potential impacts. Officials from the other selected VA investment identified a restrictive practice, but did not provide documentation demonstrating that they had analyzed potential impacts of this practice.

· Regarding the second key activity, one of the five agencies, DOJ, partially implemented the activity by developing and documenting a plan to address a restrictive practice that one of its investments had experienced. However, DOJ did not develop and document such plans for addressing other restrictive licensing practices that it had encountered. Another agency—NASA—partially implemented the activity by developing a plan that could be used to address a restrictive practice associated with a particular vendor’s cloud product. The officials acknowledged that the original intended purpose of the plan was to address a cybersecurity concern with the cloud product, but noted that the plan could also address the restrictive practice. NASA did not develop plans for addressing other restrictive practices that it had encountered.

Officials from SSA told us that the agency avoided a potential cost impact associated with purchasing software from a particular cloud vendor with restrictive licensing practices. However, SSA officials did not provide evidence that the agency had developed a plan for avoiding this impact and did not provide supporting documentation demonstrating that it had avoided the cost impact.

The other two agencies—DOT and VA—did not demonstrate that they had developed plans for mitigating impacts from the restrictive licensing practices they had experienced. Specifically, neither agency provided documentation demonstrating they had developed such plans.

Gaps in Agency Efforts Resulted in Limited Implementation of Key Activities for Managing Impacts

Key causes for the selected agencies’ lack of guidance addressing the two activities, and inconsistent implementation of them, included that (1) none of the agencies had fully assigned and documented responsibility for identifying and managing restrictive practices, and (2) the agencies did not consider the management of restrictive practices to be a priority.

· Lack of assigned and documented responsibility for managing restrictive practices. Officials from each of the five agencies that reported they had encountered restrictive licensing practices stated that the management of impacts from such practices was either the responsibility of the agency CIO or was a shared responsibility among multiple offices that manage IT and acquisitions or provide legal counsel. However, none of the five agencies had specifically assigned or documented this responsibility. As such, it was unclear who was accountable at each agency for ensuring the consistent implementation of the two key activities for managing restrictive practices.

One of DOT’s components—the Federal Aviation Administration—developed procurement guidance that assigned the component’s contracting officers responsibility for identifying certain restrictive practices, as discussed earlier. However, this guidance—which was only applicable to the component and not department-wide—did not assign responsibility for identifying or managing other types of restrictive practices, and DOT had not assigned such responsibility across the department.

In addition, although OPM reported that it had not encountered restrictive practices, the agency had not specifically assigned or documented responsibility for managing impacts from such practices. Establishing this responsibility would prepare the agency to address situations where it encounters restrictive practices in the future.

· Agencies did not consider the management of restrictive practices to be a priority. According to officials from the five agencies, they had not focused on how to address restrictive licensing practices because, as of July 2024, the agencies had not encountered many instances of such practices. The officials also stated that the impacts from such practices had not been a significant issue impacting their cloud computing services. As such, the officials stated that they either did not consider it necessary or did not consider it a priority to develop or update agency guidance to specifically address the management of such practices and their impacts.

Without implementing comprehensive guidance for managing the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices, the selected agencies are not well positioned to identify and analyze the impact of such practices or to mitigate any risks they present in an efficient and effective manner. Developing and implementing such guidance could improve the quality and consistency of the agencies’ practices for identifying, analyzing, and mitigating impacts of restrictive practices. In addition, without consistently implementing the two key activities for managing restrictive licensing practices, the agencies will likely miss opportunities to take action to avoid or minimize the impacts. Moreover, investment teams will likely take ad hoc steps—or not take any action—to identify and address them, increasing the likelihood that investment teams’ efforts to manage potential impacts are not effective.

Conclusions

Restrictive software licensing practices adversely impacted five of the six selected agencies’ cloud computing efforts. The restrictive practices either increased costs for cloud software or services or limited the agencies’ options when selecting cloud service providers.

However, none of the six selected agencies had sufficient guidance for effectively managing impacts from restrictive practices. Further, the agencies had not assigned responsibility for managing such practices. This resulted in the agencies and selected investments taking varied actions—or no action—to identify and manage such practices. Unless the agencies address these limitations and focus on managing restrictive practices, their investments will likely involve ad hoc, ineffective approaches. Further, the full extent of impacts from such practices on the agencies will remain unknown.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of 12 recommendations—two each to DOJ, DOT, NASA, OPM, SSA, and VA.

The Attorney General should update and implement Department of Justice guidance to fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices on cloud computing efforts. (Recommendation 1)

The Attorney General should assign and document responsibility for identifying and managing potential impacts of restrictive software licensing practices across the department. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Transportation should update and implement guidance to fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices on cloud computing efforts. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Transportation should assign and document responsibility for identifying and managing potential impacts of restrictive software licensing practices across the department. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Veterans Affairs should update and implement guidance to fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices on cloud computing efforts. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of Veterans Affairs should assign and document responsibility for identifying and managing potential impacts of restrictive software licensing practices across the department. (Recommendation 6)

The Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration should update and implement guidance to fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices on cloud computing efforts. (Recommendation 7)

The Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration should assign and document responsibility for identifying and managing potential impacts of restrictive software licensing practices across the agency. (Recommendation 8)

The Director of the Office of Personnel Management should update and implement guidance to fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices on cloud computing efforts. (Recommendation 9)

The Director of the Office of Personnel Management should assign and document responsibility for identifying and managing potential impacts of restrictive software licensing practices across the agency. (Recommendation 10)

The Commissioner of the Social Security Administration should update and implement guidance to fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices on cloud computing efforts. (Recommendation 11)

The Commissioner of the Social Security Administration should assign and document responsibility for identifying and managing potential impacts of restrictive software licensing practices across the agency. (Recommendation 12)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOJ, DOT, NASA, OPM, SSA, and VA for review and comment. Five of the agencies (DOT, NASA, OPM, SSA, and VA) concurred with our recommendations and one (DOJ) disagreed with our recommendations.

The following five agencies concurred with our recommendations:

· In written comments (reprinted in appendix II), DOT concurred with our two recommendations and stated that the department would provide a detailed response to each recommendation within 180 days of the final report.[28] While DOT concurred with our recommendations, it also described two concerns with our methodology and findings.

· First, DOT believes our analysis did not adequately distinguish between (1) Platform as a Service and Software as a Service cloud offerings and (2) traditional software licensing. The agency stated that such cloud services (excluding Infrastructure as a Service solutions) are fully integrated and managed services that are brokered and maintained by the provider. It also stated that these services have a supporting cost model that consists of a variety of elements (e.g., labor and hardware) and any software included is not a discretely managed and priced component exposed to the customer. DOT further noted that traditional software licenses are acquired and managed as discrete assets, and asserted that management of such licenses is not comparable with management of cloud services.

We acknowledge that not all cloud service models require traditional software licenses. However, having a cloud provider manage certain types of cloud services on the agency’s behalf does not eliminate the agency’s responsibility to identify and mitigate impacts of restrictive licensing practices when establishing new cloud agreements or managing existing services. In addition, as discussed earlier in this report and based on examples provided by officials at the selected agencies, impacts from restrictive licensing practices are not limited to cost. As such, agencies should be identifying and managing restrictive practices and other types of potential impacts that may occur. We continue to believe that our analyses are appropriate and that our recommendations apply to the management of all types of cloud computing services.

· Secondly, DOT asserted that our draft report discounted the effectiveness of existing agency controls that account for risks encountered in IT acquisitions and that we treated an absence of specific evidence of "restrictive licensing practices" as an absence of these existing controls. We disagree with this assertion. During our audit, we reviewed DOT's existing policies and procedures for managing IT acquisitions, including the department's risk management policies. We agree that DOT may be able to leverage these existing risk management practices to help address restrictive software licensing practices.

However, as discussed in the report, the department did not provide any evidence that it had used its risk management process, nor other existing agency processes, to analyze the potential impacts of the restrictive practices it had encountered. As such, we maintain that (1) without any assigned responsibility to identify or manage restrictive software licensing practices, and (2) absent any guidance specifically calling for department officials to identify such practices and manage them as risks, the department cannot be assured that it is managing restrictive practices effectively.

In addition, our methodology for assessing whether the selected agencies had implemented the two key activities for managing restrictive practices did not treat an absence of specific evidence of “restrictive licensing practices” as an absence of existing controls. In conducting our assessment, we did determine whether any parts of an agency’s policies or processes were specific to identifying and managing such practices. In doing so, we examined each agency’s relevant IT and acquisition management policies and process documents—as identified and provided by the agencies—for variations of the term “restrictive licensing practices.”

We also looked for and gave credit, where appropriate, for any other evidence that an agency’s existing policies and management controls would apply—and had been applied—to managing restrictive practices. For example, as discussed earlier in this report, we gave credit to DOT because one of its components (the Federal Aviation Administration) had developed procurement guidance that addressed identifying certain types of restrictive practices, even though the guidance did not use that specific term. Given that DOT did not provide evidence that it had (1) developed such guidance for use department-wide, and (2) used its existing agency controls, such as its risk management process, to analyze and mitigate potential impacts of the restrictive practices it had encountered, we continue to believe that our methodology and findings for the department are appropriate and warranted.

· In written comments (reprinted in appendix III), NASA agreed with our two recommendations and described specific actions the agency intended to take to address them. For example, in regard to our recommendation that the agency update and implement guidance to fully address identifying, analyzing, and mitigating the impacts of restrictive software licensing practices on cloud computing efforts, NASA stated that the agency planned to (1) implement guidance to inform users of how to identify restrictive software licensing practices affecting their cloud computing efforts and (2) establish a requirement to report them to the Office of the CIO for further analysis and mitigation. These planned actions, if implemented effectively, should better position NASA to identify, analyze, and mitigate potential impacts of restrictive practices.

· In written comments (reprinted in appendix IV), OPM agreed with our two recommendations and described planned actions to address them. For example, related to our recommendation that the agency assign and document responsibility for identifying and managing potential impacts of restrictive software licensing practices across the agency, OPM stated that OPM's Office of the CIO would take the lead to identify, by the end of fiscal year 2025, a centralized component to be responsible for identifying and managing such impacts. Identifying a centralized component to be responsible for those activities should better position OPM to mitigate potential impacts of restrictive software licensing practices, should they occur.

· In written comments (reprinted in appendix V), SSA stated that the agency agreed with our two recommendations to the agency.

· In written comments (reprinted in appendix VI), VA stated that the agency agreed with our conclusions and concurred with our two recommendations to the agency. VA also stated that it would provide the actions it plans to take to address the recommendations in its 180-day update to the final report.

One agency, DOJ, did not concur with our recommendations. Specifically, a DOJ Audit Liaison Specialist communicated via email that DOJ did not concur with the recommendations because the two key activities we used in our assessments—and on which our recommendations are based—are leading practices for IT acquisition and risk management, instead of federal policy or guidance.[29] DOJ further noted that the source of these leading practices (ISACA’s Capability Maturity Model Integration v3.0) does not have governing authority over federal agencies.

We acknowledge DOJ’s point that leading industry practices do not have governing authority over federal agencies. We also discuss earlier in the report that, as of June 2024, there were no federal requirements or guidance on managing restrictive software licensing practices. However, we maintain that our findings and recommendations to DOJ are valid and appropriate. In the absence of relevant federal policy or guidance—or when such guidance is not comprehensive enough to address our objectives—GAO identifies criteria from other credible sources, in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. These standards state that suitable criteria are relevant, reliable, objective, and understandable and do not result in the omission of significant information, as applicable, within the context of the audit objectives.[30] The standards also identify examples of suitable criteria, such as technically developed standards, expert opinions, and defined business practices. We maintain that the two key activities that are based on leading industry practices in ISACA’s Capability Maturity Model Integration v3.0 are suitable and appropriate for this review. We also affirm their relevance as a sound basis for the recommendations to DOJ. As such, we continue to believe that the recommendations to DOJ are appropriate and warranted.

Finally, we received technical comments from DOJ and OPM, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Attorney General, Commissioner of the Social Security Administration, Director of the Office of Personnel Management, Secretary of Transportation, Secretary of Veterans Affairs, and other interested parties. In addition, this report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Carol Harris at (202) 512-4456 or HarrisCC@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VII.

Carol C. Harris

Director, Information Technology Acquisition Management Issues

Our objectives were to (1) describe how restrictive software licensing practices have impacted selected agencies’ cloud computing services and (2) evaluate the extent to which selected agencies have effectively managed the potential impact of restrictive software licensing practices.

To address both objectives, we selected a stratified random nongeneralizable sample of six agencies for review. To do so, we categorized the 26 federal agencies listed on the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) IT Dashboard as small, mid-sized, and large.[31] Specifically, we used the following cost ranges to categorize the agencies based on their software and outside services spending in fiscal year 2023 (these budget categories are known to include cloud computing services):

· Large: greater than $1 billion;

· Mid-sized: greater than $500 million to $1 billion; and

· Small: $300 million to $500 million.

We then excluded the following agencies:

· Those that had spent less than $300 million on these services (this included nine agencies);

· the Department of Defense, which was included in a recent review with similar objectives;[32] and

· the General Services Administration, which we met with to discuss the agency’s role in advising agencies about cloud computing, as discussed later.

From the 15 remaining agencies, we randomly selected two agencies from each size category for review, for a total of six agencies. The selected agencies were:

· Large: the Departments of Justice (DOJ) and Veterans Affairs (VA);

· Mid-sized: the Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Social Security Administration (SSA); and

· Small: the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

We also selected a nongeneralizable sample of 11 IT investments from across the six selected agencies for review. Specifically, for five of the six agencies—DOJ, DOT, NASA, SSA, and VA—we selected two investments from each for review. The final agency—OPM—had only one investment that met our selection criteria, as discussed later. We therefore selected the one applicable investment from this agency.

To select the 11 investments for review, we used the data from OMB’s IT Dashboard. Specifically, for each selected agency, we sorted the agency’s list of IT investments on the Dashboard in decreasing order based on the sum of its fiscal year 2023 software and outside services spending. We then excluded any investments where spending was below $3 million.

From the remaining investments, we assigned random numbers to each agency’s IT investments and then ranked them in descending order. After excluding any Office of Inspector General investments, we selected up to 16 investments at each agency. OPM and SSA had fewer than 16 IT investments whose fiscal year 2023 software and outside services spending was at least $3 million. As such, we selected all of their applicable IT investments that were over the $3 million threshold.

Specifically, for each agency, we first selected the agency’s 10 investments that had been assigned the largest values in our random number assignment. We then selected up to six additional investments from each agency. In making those selections, we ensured that the selected investments included various agency components.

We sent the set of selected investments to each agency and asked officials to identify, for each investment: (1) whether it included cloud computing and (2) which component was responsible for it. For the investments that agencies identified as including cloud computing, we requested additional information about the cloud services, including cloud type (e.g., Infrastructure as a Service) and cloud service provider. We also asked whether the investments included software or services in production in the cloud and excluded investments that did not. We used the data the selected agencies provided on these investments to select a nongeneralizable sample of two cloud investments per agency for detailed review (except for OPM, which had only one investment that met our selection criteria, as discussed earlier). In selecting the investments, we ensured that they included a mix of cloud computing types, cloud service providers, and representation from various agency components.

We also met with relevant officials from OMB to determine whether there were any federal requirements or guidance on managing restrictive software licensing practices. As of June 2024, there were no such federal requirements or guidance. In addition, we interviewed officials from the General Services Administration to obtain background information and context about federal agencies’ experiences with identifying restrictive practices and managing any related potential or actual impacts.

To address our first objective, we conducted structured interviews with cognizant officials responsible for IT, acquisition management, and cloud computing at each selected agency. This included agency- and component-level officials, as well as officials responsible for the 11 selected investments. Specifically, the structured interviews focused on identifying any restrictive practices and related impacts that the selected agencies had encountered or experienced, and agency and component responsibility and established processes, if any, for managing restrictive practices.

To corroborate information about the restrictive practices and related impacts that agency officials described, we obtained and analyzed supporting documentation, where available. As discussed earlier in the report, such documentation was not available from all agencies.

To address our second objective, we reviewed ISACA’s Capability Maturity Model Integration v3.0 and selected relevant practices in the areas of acquisition and risk management.[33] We organized the selected practices into two key activities: (1) identifying and analyzing impacts of restrictive practices during the acquisition process and for established IT investments or projects, and (2) developing plans for mitigating adverse impacts. We had also previously assessed the Department of Defense’s efforts to implement these two key activities for managing restrictive software licensing practices.[34]

To determine the extent to which the selected agencies had managed the potential impact of restrictive software licensing practices, we obtained and analyzed documentation of relevant agency strategies, guidance, and processes. For example, we analyzed, among other things: agency cloud strategies, IT management policies, risk management policies, and acquisition management policies. During our analysis of these documents, we determined whether any parts of the policies or processes were specific to identifying and managing restrictive practices. We also obtained and analyzed documentation of agency efforts to manage restrictive licensing practices—such as relevant risk management artifacts—where such documentation existed. We then compared this documentation to the two key activities for managing restrictive software licensing practices and their potential impacts.

Regarding our assessments of whether the selected agencies had implemented the two key activities for managing restrictive software licensing practices, we focused on the five agencies that reported they had encountered such practices—DOJ, DOT, NASA, SSA, and VA.[35] We assessed those agencies’ efforts to implement the first key activity as follows:

· Fully implemented: The agency provided supporting documentation that demonstrated that it had analyzed the impacts of all such practices it had encountered. In addition, the agency provided documentation that all of its selected investments had taken action to identify any restrictive practices that may have impacted those investments.

· Partially implemented: The agency provided supporting documentation that demonstrated that (1) it had analyzed the impacts of at least one, but not all, such practices it had encountered, or (2) at least one, but not all, of the agency’s selected investments had taken action to identify any restrictive practices that may have impacted those investments.

· Not implemented: The agency did not provide supporting documentation that demonstrated that (1) it had analyzed the impacts of any such practices it had encountered and (2) any of the agency’s selected investments had taken action to identify restrictive practices that may have impacted those investments.

Similarly, we assessed the five agencies’ efforts to implement the second key activity as follows:

· Fully implemented: The agency provided supporting documentation that demonstrated that the agency had developed plans for mitigating adverse impacts from all of the restrictive licensing practices it had encountered.

· Partially implemented: The agency provided supporting documentation that demonstrated that the agency had developed plans for mitigating adverse impacts from at least one, but not all, of the restrictive licensing practices it had encountered.

· Not implemented: The agency did not provide supporting documentation that demonstrated that the agency had developed plans for mitigating adverse impacts from any of the restrictive licensing practices it had encountered.

We also interviewed cognizant IT and acquisition management officials from the selected agencies and investments to obtain additional information about responsibility and processes for managing restrictive software licensing practices. This included interviews with agency- and component-level officials, as well as officials responsible for the 11 selected investments.

As part of our overall assessment of the selected agencies’ efforts to manage the potential impact of restrictive software licensing practices, we assessed the relevance of standards for internal control.[36] We determined that the control environment, risk assessment, control activities, and information and communication components of internal control were significant to this objective. Of specific relevance were internal control principles that emphasize that management should (1) establish an organizational structure, assign responsibility, and delegate authority to achieve the entity’s objectives; (2) identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving the defined objectives; (3) design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks; (4) implement control activities through policies; and (5) internally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Carol C. Harris at (202) 512-4456 or HarrisCC@gao.gov

In addition to the contact named above, the following staff made key contributions to this report: Emily Kuhn (Assistant Director), Amanda Gill (Analyst-in-Charge), Christopher Businsky, Jillian Clouse, Rebecca Eyler, Elizabeth Gooch, India Sharpe, Elizabeth Simonelli, Andrew Stavisky, and Adam Vodraska.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Office of Management and Budget, 25 Point Implementation Plan to Reform Federal Information Technology Management (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 9, 2010).

[2]National Institute of Standards and Technology, Special Publication 800-145 (Gaithersburg, MD: September 2011).

[3]GAO, Information Technology Reform: Progress Made but Future Cloud Computing Efforts Should be Better Planned, GAO‑12‑756 (Washington, D.C.: July 11, 2012).

[4]We defined restrictive software licensing practices as any software licensing agreements or vendor processes that limit, impede, or prevent agency efforts to use software in cloud computing. GAO, DOD Software Licenses: Better Guidance and Plans Needed to Ensure Restrictive Practices Are Mitigated, GAO‑23‑106290 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2023).

[5]OMB’s IT Dashboard is a public website that provides detailed information on IT investments at 26 federal agencies. See https://itdashboard.gov/. On the federal IT Dashboard, the “outside services” category includes consulting, managed service providers, and cloud service providers.

[6]ISACA, CMMI Model V3.0 (Pittsburgh, PA: Apr. 6, 2023). CMMI Model and ISACA ©[2023] All rights reserved. In particular, we reviewed and selected relevant practices from the CMMI practice areas of supplier agreement management, service delivery management, risk management, and causal analysis and resolution.

[7]See GAO‑23‑106290.

[8]National Institute of Standards and Technology, Special Publication 800-145.

[9]GAO, Federal Software Licenses: Better Management Needed to Achieve Significant Savings Government-Wide, GAO‑14‑413 (Washington, D.C.: May 22, 2014).

[11]ISACA, CMMI Model V3.0 (Pittsburgh, PA: Apr. 6, 2023). CMMI Model and ISACA ©[2023] All rights reserved. Used with permission.

[12]OMB, 25 Point Implementation Plan (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 9, 2010).

[13]OMB, Federal Cloud Computing Strategy (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 8, 2011).

[14]Carl Levin and Howard P. ‘Buck’ McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015, Pub. L. No. 113-291, division A, title VIII, subtitle D, 128 Stat. 3438 (Dec. 19, 2014).

[15]The provisions of section 11319(b) apply to agencies covered by the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990, 31 U.S.C. § 901(b). The Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act has generally limited application to the Department of Defense.

[16]OMB, Management and Oversight of Federal Information Technology, M-15-14 (Washington, D.C.: June 10, 2015).

[17]OMB, Federal Cloud Computing Strategy (Washington, D.C.: June 2019).

[18]Since 2010, the General Services Administration has played a role in supporting federal agencies in the development and deployment of federal cloud computing technology. As part of this, the agency operates a Cloud Information Center that, among other things, shares information about cloud computing best practices and common cloud acquisition challenges across the federal government. The agency also supports government-wide acquisition contracts, including those used by agencies to acquire cloud software and services.

[19]General Services Administration, Federal Cloud Strategy Guide Agency Best Practices for Cloud Migration (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 2021); and General Services Administration, Cloud Adoption Center of Excellence Playbook (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2020).

[20]The Federal CIO Council—established by Executive Order 13011 and codified by the E-Government Act of 2002—is the principal interagency forum to improve agency practices related to the design, acquisition, development, modernization, sustainment, use, sharing, and performance of federal government IT. The council’s Cloud and Infrastructure Community of Practice provides a platform for federal employees and mission-supporting contractors to share insights, ask questions, and learn from their peers on topics such as cloud migration best practices, among other things.

[22]GAO, Cloud Computing: Federal Agencies Face Four Challenges, GAO‑22‑106195 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 28, 2022).

[23]GAO, DOD Software Licenses: Better Guidance and Plans Needed to Ensure Restrictive Practices Are Mitigated, GAO‑23‑106290 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2023).

[24]GAO, Federal Software Licenses: Agencies Need to Take Action to Achieve Additional Savings, GAO‑24‑105717 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 29, 2024).

[25]Agency officials at three selected agencies reported that they had encountered restrictive practices that required or promoted vendor lock-in. We discuss these restrictive practices in more detail later in this report.

[26]ISACA, CMMI Model V3.0 (Pittsburgh, PA: Apr. 6, 2023). CMMI Model and ISACA ©[2023] All rights reserved. Used with permission.

[27]OMB established the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program in 2011 to safely accelerate the adoption of cloud computing products and services by federal agencies. The program is intended to provide a standardized approach for selecting and authorizing the use of cloud service offerings that meet federal security requirements.

[28]Under 31 U.S.C. § 720, when GAO makes a report that includes a recommendation to an agency head, the agency head is to provide to GAO, among others, a written statement on action taken or planned on the recommendation. This written statement is to be submitted to GAO, among others, within 180 days of the date of the report.

[29]The two key activities were (1) identifying and analyzing impacts of restrictive practices during the acquisition process and for established IT investments or projects, and (2) developing plans for mitigating adverse impacts.

[30]GAO, Government Auditing Standards: 2018 Revision Technical Update April 2021 (Supersedes GAO-18-568G), GAO-21-368G (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 14, 2021).