HIGHLIGHTS OF A FORUM

Expert Views on the Federal Statistical System

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Jared Smith at SmithJB@gao.gov

What GAO Found

The federal statistical system faces a critical juncture as it works to modernize and adapt to a rapidly changing data landscape, driven by increasing demand for timely, detailed, and relevant information amid declining survey response rates and rising data collection costs. During a forum GAO held in 2024, experts and stakeholders identified various challenges and opportunities facing the system across a range of topics (see figure).

Public Trust. The system faces growing challenges in building and maintaining public trust, particularly as it navigates emerging risks to privacy and confidentiality, according to participants. Suggestions for improving public trust include promoting transparency and advancing privacy enhancing technologies.

Data Access and Support. According to participants, the system faces challenges in meeting the needs of a diverse user base, from highly technical researchers to non-technical data users, and in facilitating access to data products. The system also faces challenges in offering appropriate guidance and tools tailored to users. Potential options for addressing these challenges include expanding data user outreach and training, as well as developing a streamlined data access portal with enhanced analytic capabilities and support.

Alternative Data Sources. Participants highlighted key benefits that alternative data sources—such as private sector data and administrative records—offer for improving federal statistical production and better meeting the needs of data users. Yet participants said that statistical agencies face significant challenges in using alternative data, including legal barriers and dependance on data providers. Participants said that addressing these issues will require strong data security and incentives for provider participation, among other things.

Interagency Coordination. Participants identified effective interagency coordination as key for modernizing statistical production, facilitating outreach to users, and alleviating resource constraints. However, the decentralized design of the system and the absence of a shared framework for interagency data sharing hinder coordination among agencies, creating barriers to data sharing. Suggestions for strengthening interagency coordination include modernizing legislation and establishing shared data infrastructure.

Why GAO Did This Study

The federal statistical system includes 16 statistical agencies and units and over 100 statistical programs that produce data critical for program design, monitoring, and evaluation of federal programs. These data are vital for decisions that directly affect the public. These include the allocation of federal funding to states and localities and the production of key national statistics on health, demographics, and the economy. However, the system faces long-standing challenges that may prevent these agencies from effectively producing timely and accurate information.

In August 2024, GAO held a forum on the federal statistical system. The participants discussed what factors affect the system’s ability to (1) build and maintain public trust, (2) meet the needs of its users, (3) sustain and modernize its data collection, and (4) engage in effective interagency coordination. This report is the first in a body of work to assess opportunities to reduce fragmentation, overlap, and duplication in the system, consistent with a statutory provision for GAO to, among other things, routinely investigate government programs to identify duplicative goals and activities.

Participants included 29 experts and stakeholders from the federal statistical system, other federal agencies, state and local government agencies, a non-U.S. national statistical office, an international organization, academic institutions, the private sector, and professional organizations. GAO also interviewed officials from federal and state government agencies. Participants reviewed a draft of this report, and comments were incorporated as appropriate. Views expressed during the proceedings do not represent the opinions of all participants, their affiliated organizations, or GAO.

Abbreviations

CIPSEA Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act

NSDS National Secure Data Service

OMB Office of Management and Budget

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 24, 2025

Congressional Committees

The federal statistical system includes 16 statistical agencies and units, and approximately 100 statistical programs, tasked with providing data on a range of issues, including agricultural production, education, employment, disaster planning, immigration, and other federal policy areas. The system supports decision-making and policy-setting inside and outside the government by providing accurate, objective data. For example, businesses and individuals rely on statistical products to guide financial and life decisions, from making business investments to choosing where to live or work. Key federal statistical products on inflation, unemployment, interest rates, and mortgage rates help Americans and policymakers, such as the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee, understand the economy and plan accordingly.

The decentralized structure of the system—with over a dozen statistical agencies and units operating under the coordination of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB)—creates both opportunities and challenges. Decentralization may encourage individual statistical agencies to tailor data collection and dissemination to the needs of their subject-matter domains and user communities. Because statistical agencies operate under different departments, they are positioned to be responsive to specific policy, operational, and research priorities within their sectors.

However, decentralization and fragmentation across agencies increases the risk of overlapping efforts, duplication in data collection or dissemination activities, and inefficient resource use.[1] Our prior work has addressed issues relevant to the system, highlighting challenges such as fragmented data collection, barriers to data sharing, lack of coordination and capacity constraints.[2] In February 2012, we stressed the importance of interagency collaboration and data governance within the system to produce timely and high-quality statistical information.[3]

Reforms such as the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 (Evidence Act) have encouraged the system to reevaluate traditional approaches to data collection, product development, and service delivery in response to declining public participation in surveys, rising demand for granular and policy-relevant data, and growing needs for aggregated data and microdata[4] that serve a broader range of analytic uses.[5] The Evidence Act improves the federal statistical system by creating a framework for federal agencies to take a more comprehensive and integrated approach to evidence building, and enhancing the federal government’s capacity to undertake those activities.

In October 2024, OMB issued the Fundamental Responsibilities of Recognized Statistical Agencies and Units rule, often referred to as the Trust Regulation, as part of its responsibilities under the Evidence Act, effective December 10, 2024.[6] The Trust Regulation aims to enhance public trust by codifying the roles, responsibilities, and autonomy of Recognized Statistical Agencies and Units (“statistical agencies”), among other things.[7] These new efforts have the potential to address challenges facing the system by expanding data sharing, access, and collection for statistical purposes.[8]

The Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010 included a provision for GAO to conduct routine investigations to identify programs, agencies, offices, and initiatives with duplicative goals or activities governmentwide.[9] Consistent with these provisions, GAO has initiated a body of work to assess opportunities to reduce fragmentation, overlap, and duplication in the federal statistical system. To identify the most pressing issues facing the system, in August 2024, GAO convened a discussion forum of a panel of experts and stakeholders. In this report, we examine forum participants’ perspectives on factors that affect the system’s ability to (1) build and maintain public trust, (2) meet the needs of its users, (3) sustain and modernize its data collection, and (4) engage in effective interagency coordination.

To prepare the discussion forum and this report, we conducted a systematic literature search and reviewed 51 studies concerning the federal statistical system that met several criteria for inclusion.[10] With assistance from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) we developed a list of experts and stakeholders and administered a questionnaire to them to inform forum topics and participant selection.

On August 21–22, 2024, we convened a group of 29 experts and stakeholders on the federal statistical system for a forum focused on challenges and opportunities faced by the system. The forum was planned and convened with the assistance of National Academies. The participants, selected to represent a range of experience and viewpoints, included representatives from the federal statistical system, other federal agencies, state and local government agencies, a non-U.S. national statistical office, an international organization, academic institutions, the private sector, and professional organizations. The 2-day forum was organized around six main topical sessions related to

· modernizing federal data collection and production;

· public use and accessibility of federal statistical products;

· resources, productivity, workforce, and efficiency in a modern federal statistical system;

· innovation in alternative data sources for federal statistics;

· enhancing data sharing across federal agencies; and

· public trust and objectivity in federal statistics.

· See appendix I for the forum agenda, appendix II for a list of the participants, and appendix III for details on our scope and methodology.

The forum was professionally recorded and transcribed. This report is a summary of the forum based on a thematic analysis of the discussion transcripts. The summary aims to capture the ideas and themes that emerged from the collective discussion of the participants and where appropriate supplemented by prepared written remarks from forum participants.

The forum was structured as guided roundtable discussions on each topic where four to six participants provided opening remarks and all participants were invited to openly comment on issues and respond to one another, although not all participants commented on all topics. Participants were given the opportunity to comment on a draft of this summary, and we included their feedback, as appropriate. After the forum, we also conducted three supplementary interviews to gain additional perspectives and to follow up on key themes discussed during the forum. We did not attempt to independently validate the statements expressed by participants.

Comments summarized in this report do not necessarily represent the views of all participants, the organizations with which they are affiliated, or GAO.

We conducted our work from October 2023 to September 2025 in accordance with all sections of GAO’s Quality Assurance Framework that are relevant to our objectives. The framework requires that we plan and perform the engagement to obtain sufficient and appropriate evidence to meet our stated objectives and to discuss any limitations in our work. We believe that the information and data obtained, and the analysis conducted, provide a reasonable basis for any findings and conclusions in this product.

Background

The Federal Statistical System

The federal statistical system is a decentralized network that includes 16 statistical agencies and units in different federal departments or parent agencies.[11] A statistical agency is an entity within the executive branch whose activities predominantly are the collection, compilation, processing, or analysis of information for statistical purposes. The system spans diverse policy areas and provides critical input for program design, monitoring, and evaluation of federal programs (see table 1).

|

Statistical Agency or Unit |

Parent Agency |

Focus Area |

|

Bureau of Economic Analysis |

Dept. of Commerce |

Focuses on economic statistics to produce data on gross domestic product, personal income, and other economic indicators. |

|

Bureau of Justice Statistics |

Dept. of Justice |

Collects, analyzes, and disseminates statistics on crime, criminal offenders, and the criminal justice system. |

|

Bureau of Labor Statistics |

Dept. of Labor |

Provides information on the U.S. labor market and economic conditions by producing labor-related statistics, including the unemployment rate and inflation. |

|

Bureau of Transportation Statistics |

Dept. of Transportation |

Gathers and analyzes data on transportation, including infrastructure, safety, and travel patterns. |

|

Census Bureau |

Dept. of Commerce |

Conducts the decennial census and ongoing surveys, such as the American Community Survey, to provide demographic, economic, and housing information. |

|

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality |

Dept. of Health and Human Services |

Operates within the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to conduct national surveys tracking population-level behavioral health issues. |

|

Economic Research Service |

Dept. of Agriculture |

Produces studies, economic analyses, and market assessments by examining factors such as commodity markets, farm income, and food assistance programs. |

|

Energy Information Administration |

Dept. of Energy |

Specializes in energy-related statistics, including production, consumption, and distribution of energy resources. |

|

Microeconomic Surveys |

Federal Reserve Board |

Operates within the Division of Research and Statistics to conduct research in a variety of areas, including consumer finances, financial markets, and general applied microeconomics. |

|

National Agricultural Statistics Service |

Dept. of Agriculture |

Collects and disseminates agricultural statistics and analyses to provide information on the agricultural sector, crop production, and livestock, among other things. |

|

National Animal Health Monitoring System |

Dept. of Agriculture |

Operates within the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service to conduct national studies on the health and health management of U.S. domestic livestock, equine, aquaculture, and poultry populations. |

|

National Center for Education Statistics |

Dept. of Education |

Focuses on education-related statistics, providing data on schools, educational attainment, and learning outcomes. |

|

National Center for Health Statistics |

Dept. of Health and Human Services |

Operates within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to provide health-related data, including vital statistics, and health surveys. |

|

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics |

National Science Foundation |

Gathers and analyzes data on science and engineering research and development, education, and workforce. |

|

Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics |

Social Security Administration |

Supports research, evaluation, and statistical analyses related to retirement, disability, and survivor benefits. |

|

Statistics of Income Division |

Dept. of Treasury |

Collects, analyzes, and disseminates data on the income, taxes, and financial activities of individuals, businesses, and corporations. |

Source: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. | GAO‑25‑107124

Note: A statistical agency or unit is an entity in the executive branch whose activities are predominantly the collection, compilation, processing, or analysis of information for statistical purposes. The federal statistical system is a decentralized network of 16 statistical agencies and units (listed in table 1), 24 statistical officials (across 24 major cabinet agencies), approximately 100 additional federal statistical programs engaged in statistical activities, and several cross system interagency and advisory bodies.

While statistical agencies are typically embedded within larger parent agencies, they are expected to operate with a degree of autonomy to ensure the integrity, objectivity, and utility of the data they produce.[12] At the same time, these agencies contribute to the missions of their parent agencies by producing data that inform policy, evaluate programs, and support decision-making—demonstrating a dual role of statistical autonomy and institutional alignment with broader departmental goals.[13]

OMB’s Role in Statistical Coordination and Oversight

OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs is charged with overseeing the use of information resources, including statistics, to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of governmental operations to serve agency missions, including burden reduction and service delivery to the public.[14] Within OMB, the Chief Statistician of the United States provides leadership on standards and interagency coordination through disseminating statistical policies and guidance.[15]

Specifically, OMB’s statutory statistical responsibilities include the following:

· Oversight and approval of data collection. OMB is to review and approve proposed federal agency information collections that will be administered to 10 or more people, including minimizing the information collection burden and maximizing the practical utility of information collected by or for the federal government.[16]

· Guidance and standards. OMB is to develop and oversee policies, principles, standards, and guidelines for federal information resources management, such as those for statistical activities, public access to data, and privacy and confidentiality.[17]

· Coordination. OMB is to coordinate the activities of the federal statistical system to ensure the integrity, objectivity, and utility of information, among other things.[18]

· Oversight of budgets. OMB is to ensure that statistical agencies’ budget proposals are consistent with system-wide priorities for maintaining and improving the quality of federal statistics.[19]

As the coordinating body for the federal statistical system, OMB plays a central role in fostering collaboration and consistency across agencies, including through its leadership of the Interagency Council on Statistical Policy. The council is chaired by the Chief Statistician of the United States at OMB and brings together heads of major statistical programs to address cross-cutting issues. For example, the council has coordinated to align statistical agency practices with the Evidence Act and other reforms, which encourages statistical agencies to reevaluate existing approaches to data collection, product development, and service delivery. Specific coordination efforts have included improving data access and advancing interagency data sharing and shared services.[20]

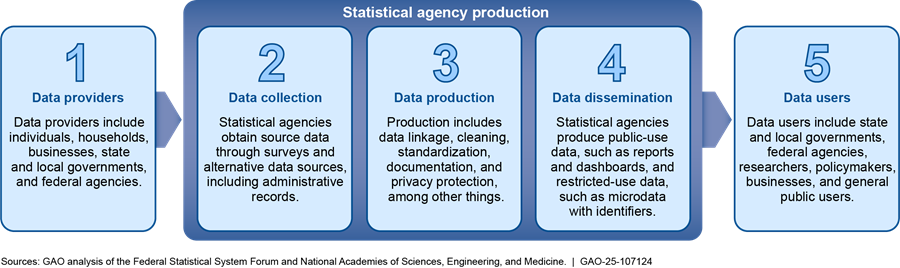

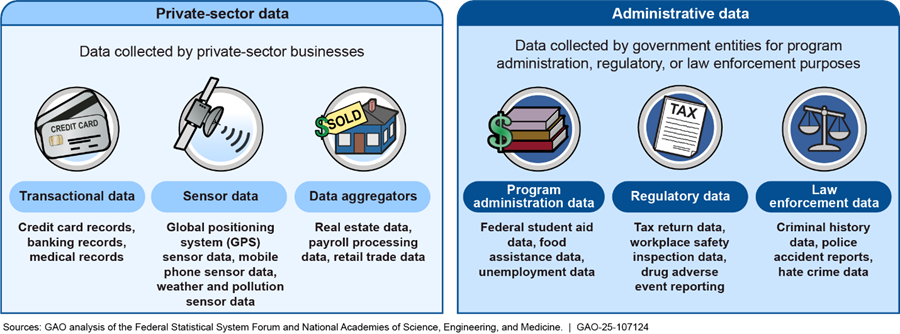

Data Providers and Users

Data providers and users play essential roles throughout the life cycle of federal statistical products—from initial data collection and processing to dissemination and application—ensuring that the federal statistical system both produces accurate information and delivers insights that inform decision-making and public understanding (see fig. 1).

Data Providers

Data providers—including individuals, households, businesses, state and local governments, and federal agencies—supply critical raw data to the federal statistical system by responding to surveys and contributing to non-survey, alternative data sources.

Agencies are expected to collect data from providers using surveys designed specifically for statistical purposes. These surveys are intended to collect statistical data for the purpose of describing or making estimates on a wide range of topics. However, participation in federal surveys is often voluntary and has been declining over time, driven in part by concerns over privacy and confidentiality, as well as response burden.[21]

For example, according to the Census Bureau, the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns caused major disruptions to the 2020 American Community Survey,[22] resulting in a decline in the response rate (to 71 percent).[23] The National Crime Victimization Survey led by the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the National Health Interview Survey led by the National Center for Health Statistics have also seen significant declines in response rates, with the former dropping from 80 percent in 2011 to 50 percent in 2021, and the latter from 70 percent to 50 percent in the same period. In addition to raising data collection costs, declining response rates have prompted concerns about data quality and representativeness.[24] In general, lower response rates increase the risk of less accurate estimates for statistical products.

Data providers also contribute to alternative data sources—that is, data collected for non-statistical purposes. These alternative data sources include transaction and consumer data from private-sector businesses and administrative records from federal programs, among other sources (see fig. 2). Through administrative records, where the information is provided to receive benefits or comply with the law, the government holds sensitive data about individuals, covering areas such as income, immigration, and health records.

Although alternative data sources were not originally created for statistical purposes, federal statistical agencies are increasingly exploring the blending of these data with traditional surveys to improve the timeliness, granularity, and relevance of national statistics.[25] This blended approach aims to address persistent challenges such as declining response rates and rising data collection costs.[26] For example, in response to initial COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns, the Bureau of Labor Statistics explored using private-sector transaction data, such as web-scraped data, to improve the accuracy and timeliness of price indices when in-person data collection methods (i.e., surveys) were unavailable.[27]

Data Users

Data users—including government entities, businesses, researchers, and the general public—rely on different types of data products, including aggregated data and microdata, to inform decisions, shape policies, and address community needs.

· State and local governments use federal statistical data—such as estimates on population, health, income, or housing—to inform local planning, resource allocation decisions, and to distribute state funding to localities. For example, they may use data from the Census Bureau to target policy interventions by region or demographic group within a state or locality.

· Federal agencies and programs use statistical data to evaluate program performance and allocate funding to various recipients. For example, agencies may integrate statistical data with administrative records to address key policy questions.[28] In addition, several federal assistance programs use Census Bureau data—either in whole or in part—to guide funding allocations for areas such as health care, nutrition, highways, housing, school lunches, child care, and COVID-19 relief.

· Researchers and academics often depend on access to restricted-use microdata (i.e., data at the individual record level) for analysis in areas like public health and education.

· Policymakers may use statistical reports and aggregated findings to understand population needs, shape legislation, and conduct oversight. For example, social or economic statistics can influence decisions on funding formulas or the scope of a policy intervention.

· Businesses use federal statistical data for market analysis, risk modeling, and strategic planning.

· General public users may access summary statistics, dashboards, and public-use microdata to get statistical data relevant to their daily lives, including information on education, commuting, health, crime, and demographics, such as aging in their communities.

Data Privacy Protections

Federal statistical agencies operate under a legal framework designed to protect the confidentiality of the information they collect. Specifically, the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act (CIPSEA) enacted originally in 2002, and reauthorized and expanded in 2018, is a core statute that governs the use of data acquired for exclusively statistical purposes.[29] CIPSEA seeks to safeguard individually identifiable information collected for statistical purposes under a pledge of confidentiality. To do so, it prohibits the disclosure of such data for any non-statistical purposes without the respondent’s informed consent.[30]

CIPSEA authorizes limited sharing of business data among designated statistical agencies for statistical purposes[31] and requires non-statistical executive branch agencies to provide data requested from statistical agencies to the extent practicable, among other things.[32] It also includes direction for OMB to issue regulations to facilitate such sharing while establishing standards, to the extent possible, for complying with applicable laws requiring the protection and confidentiality of individually identifiable information.[33] In December 2022, OMB established a Standard Application Process for researchers, agencies, state and local governments, and other authorized users to apply to securely access confidential statistical data that were acquired for statistical purposes.[34]

Department and office-specific laws provide additional protections that impose confidentiality or use requirements and potential criminal penalties for unlawful disclosure (see table 2).

Table 2: Selection of Department/Office-Specific Statutory Provisions for Confidentiality of Data Collected for Statistical Purposes

|

Department/Office |

Statutory Provision |

Description |

|

Department of Agriculture |

7 U.S.C. 2276 |

Includes limits on disclosure of certain information, including individually identifiable data collected for specific statistical purposes, and potential criminal penalties for violations. |

|

Department of Commerce |

13 U.S.C. 9, 214 |

Includes a prohibition on the disclosure of any information that could identify respondents for any purpose other than the statistical purpose it was provided; potential criminal penalties for violations. |

|

Institute of Education Sciences |

20 U.S.C. 9573 |

Prohibits use of individually identifiable information about students, their academic achievements, their families, and information with respect to individual schools for any purpose other than research, statistics, or evaluation, among other things. It also includes potential criminal penalties for violations. |

|

Internal Revenue Service |

26 U.S.C. 6103, 7213 |

Generally restricts access to and disclosure of tax return information, ensuring taxpayer confidentiality with exceptions that include certain statistical uses by specified federal entities. Willful unauthorized disclosures may result in potential criminal penalties for violation. |

Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑25‑107124

In addition to statutory safeguards establishing legal foundations for protecting confidential information, statistical agencies also use privacy-enhancing technologies—such as synthetic data and differential privacy, among other disclosure avoidance methods—to further strengthen these protections throughout the data life cycle.[35] These technologies include the following:

· Synthetic data. Synthetic data are artificially generated datasets that replicate the statistical properties of real data without including actual respondent-level information. The technique allows users to conduct exploratory analysis and develop models without direct access to sensitive microdata. For example, the Census Bureau has developed synthetic datasets for the Survey of Income and Program Participation to support research use while reducing disclosure risk.[36]

· Differential privacy. Differential privacy introduces mathematically defined noise into statistical outputs that aims to preserve their value for statistical analysis, while limiting the ability to infer individual-level information. The Census Bureau implemented differential privacy for the 2020 Decennial Census through a disclosure avoidance system—the first large-scale use of this technique in a federal statistical product.[37]

The Federal Statistical System Faces Challenges in Building and Sustaining Public Trust, but Responsible Data Stewardship and New Reforms Offer Opportunities

Forum participants identified public trust as a cross-cutting issue that plays an important role in the modernization of the federal statistical system. Participants noted that the system faces growing challenges in building and maintaining public trust, particularly as it navigates emerging risks to the privacy and confidentiality of its data, as well as the autonomy of its statistical agencies. Participants discussed opportunities to reinforce public confidence in the system by embracing responsible data stewardship and public trust initiatives that promote transparency, safeguard privacy, and foster meaningful engagement across the statistical product life cycle.

Challenges in Building and Sustaining Public Trust in Federal Statistics

Risks to Privacy, Confidentiality, and Integrity

According to forum participants, public trust is fundamental to the federal statistical system, both from the perspective of data providers and data users. Data providers, including individuals, businesses, and organizations, must trust that their information, such as responses to surveys, will be kept confidential and used solely for statistical purposes. As one participant noted, when a statistical agency approaches individuals for data collection, the respondent must trust that the agency’s confidentiality protections will safeguard their information, allowing them to report truthfully.

However, when trust in statistical agencies erodes due to concerns regarding disclosure risks or data leaks, respondents may refuse to participate in surveys and other federal data collection efforts. This may lead to a decline in survey response rates, and those who do respond may be less willing to provide truthful information, ultimately compromising the accuracy and reliability of federal statistical data.[38]

|

One Participant’s View on Public Trust “If there’s a significant privacy violation then the loss of trust will lead to all of the future statistical product tables being unreliable…one demonstration of this is what I call the January 1st problem that various online services have, which is that a disproportionate number of people report their birthday to be January 1st.” |

Source: Participant in the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

Similarly, data users rely on the integrity and autonomy of statistical agencies to provide accurate and unbiased information. According to one participant, “there’s no real substitute” that provides the same level of rigor, consistency, and national representativeness as federal statistical products. Any perceived external influence or lack of transparency can erode confidence in federal statistical data and products, potentially leading to their diminished use in decision-making.[39] Thus, according to one participant “Trust in federal statistical agencies is extraordinarily important for both the collecting of statistical data and the reporting out of statistical information.”

Participants identified three challenges that statistical agencies face in maintaining public trust, as well as specific risks that may erode confidence in statistical products (see table 3).

Table 3: Reported Challenges Affecting Public Perceptions of Privacy, Confidentiality, and Integrity of Federal Statistical Agencies

|

Challenge |

Description |

|

Evolving data ecosystems |

Evolving data ecosystems, such as expanding users and the use of administrative records, can increase perceived risks to confidentiality. |

|

Use of statistical products outside of intended scope |

Using statistical products outside their intended scope can erode public trust. |

|

Role distinction |

The public may misunderstand the distinct roles between statistical activities and other policy functions. |

Source: GAO analysis of the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

|

Gauging Public Trust in Statistical Activities

Some federal statistical agencies assess public trust in the federal statistical system through surveys and feedback tools designed to gauge perceptions of credibility, transparency, and data stewardship. The Census Bureau includes trust-related questions in several of its efforts, including the Household Pulse Survey, which began collecting insights related to public trust. Additionally, the Census Barriers, Attitudes, and Motivators Study explores public perceptions of federal data collection, including concerns about privacy, data use, and credibility. Similarly, the Bureau of Labor Statistics introduced a customer satisfaction survey on its public website in April 2024. One of the key questions asks users whether they agree or disagree that the Bureau of Labor Statistics is a trusted source of information and to provide direct feedback on the agency’s reputation for reliability. Source: Andrii Yalanskyi/stock.adobe.com (image); GAO analysis of agency documentation and forum follow-up; Kylee McGeeney et al., 2020 Census Barriers, Attitudes, and Motivators Study Survey Report (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). | GAO‑25‑107124 |

Evolving data ecosystems. Participants warned that a breach of confidentiality could affect how the public perceives the statistical system, and that changes in data ecosystems—such as modernization efforts to expand access to statistical data to a range of data users and to create products from data that is blended from a variety of sources—make efforts to implement privacy and confidentiality safeguards more urgent.[40] In addition, expanded use of alternative data sources, such as administrative and proprietary data, to supplement statistical data also raises privacy concerns, as these data often lack the same confidentiality protections and governance frameworks as traditional federal statistical data.

While federal surveys typically include robust consent procedures that clarify how data will be used, such transparency and legal protections are not always present for administrative or proprietary data. In some cases, there is no overarching legal framework ensuring consistent privacy protections for these data when used for statistical purposes, although some safeguards may exist depending on the source or agency.[41] Linking traditional survey data with less-protected sources may heighten data providers’ concerns about misuse or reidentification, leading to skepticism and reduced willingness to share information.

Use of statistical products outside of intended scope. Using statistical products outside of their intended scope can also erode trust in the federal statistical system. For example, a forum participant raised concerns about policymakers’ use of the National Risk Index, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s aggregation of data from the federal statistical system.[42] The Federal Emergency Management Agency developed the National Risk Index using data from the Census Bureau, among other data sources, to identify areas at risk from natural hazards, such as floods, wildfires, and hurricanes.

However, policymakers have used the National Risk Index as a tool to inform mitigation planning and data-driven decision making aimed at disaster preparedness and resilience across localities. The forum participant discussed how a data user told them that the National Risk Index quickly took on outsized importance relative to local data and first-hand observations. Further, the data user found that relying solely on the National Risk Index to allocate funding to localities may be flawed, as the index was not originally designed for that purpose—potentially leading to funding decisions that misalign with actual local needs.

Role distinction. Participants discussed how a general lack of trust in the U.S. government can make it difficult for statistical agencies to maintain public trust in the federal statistical system, particularly when the public may not differentiate statistical activities from other government functions. One forum participant highlighted a key finding from a recurring survey of international, high-income countries, which found that trust in government statistics is closely associated with levels of trust in government.[43] Another participant cited an annual study of public trust in government, which estimated that 16 percent of Americans trusted the government “just about always” or “most of the time”—the lowest in 7 decades of polling.[44]

Participants suggested that public outreach and clearly communicating the difference between statistical activities and other government functions could clarify statistical agencies’ objectivity and lack of outside influence. This distinction helps assure the public that data are used solely for statistical activities and will not be misused. According to participants, public misunderstanding in these roles could raise concerns about how the data are used, potentially affecting perceptions of the system’s reliability and integrity.

Statistical Agency Autonomy Within Parent Agencies

According to participants, the autonomy of statistical agencies within their parent agencies plays a critical role in building and sustaining public trust. Agencies may struggle to ensure the transparency, accountability, and integrity of federal statistical data without sufficient autonomy over how data are collected, processed, and disseminated, which may ultimately affect public confidence in the system. Participants noted that the placement of statistical agencies within larger parent agencies may limit their autonomy in three ways: misalignment of goals, limited interaction with congressional policymakers, and lack of direct budget input (see table 4).

Table 4: Reported Challenges Affecting Statistical Autonomy Within Parent Agencies of the Federal Statistical System

|

Challenge |

Description |

|

Misalignment of goals |

Parent agencies may have policy, operational, or regulatory missions that do not include statistical priorities. |

|

Limited interaction with congressional policymakers |

Statistical agencies may have insufficient mechanisms to communicate directly with congressional stakeholders. |

|

Lack of direct budget input |

Statistical agencies may not have had a mechanism to directly participate with Congress in the annual budget formulation process.a |

Source: GAO analysis of the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

aFollowing the Federal Statistical System Forum on August 21-22, 2024, the Trust Regulation, effective December 10, 2024, requires statistical and parent agencies to jointly coordinate to develop a separate budget request for the statistical agency, submitted as part of the parent agency’s budget to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The regulation also ensures the statistical agency head can participate in related OMB discussions. See 5 C.F.R. 1321.4(g)(1-2).

Misalignment of goals. Participants noted that it is sometimes hard to determine how a statistical agency’s goals align with its parent agency’s goals. While statistical agencies are expected to function in an environment that is autonomous from other administrative, regulatory, law enforcement, or policy-making activities within their parent agency to ensure objectivity, they are also expected to collaborate with their parent agencies to enhance the relevance and usefulness of statistical products.[45] In addition, statistical agencies are expected to support priorities to maintain and improve the quality of federal statistics as directed by OMB.[46] However, according to participants, the extent to which these statistical priorities are incorporated into the broader goals and priorities of parent agencies is not always clear, which may limit the effectiveness of such collaboration and harm public trust.

For example, one participant cited a 2007 advocacy report that highlighted the lack of clarity regarding how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s public health objectives—emphasizing public health interventions, disease prevention, and preparedness—aligned with the National Center for Health Statistics mission to produce health statistics.[47] The report stated that this lack of clarity raised concerns about whether the National Center for Health Statistics could maintain its independence as a statistical agency, given its location within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. According to forum participants, a lack of alignment and institutional support between a parent agency and its statistical agency can potentially limit the latter’s autonomy and ability to maintain the confidentiality of sensitive data, undercut budget and staffing support, and constrain professional decisions on data production and dissemination.

Limited interaction with congressional policymakers. Participants discussed concerns regarding the ability of statistical agencies to have greater autonomy in the legislative process, whether individually or as a system. One participant noted that congressional hearings on oversight and appropriations often do not include federal statistical representatives. The parent agency generally designates a cabinet secretary or other senior official who may choose to prioritize speaking to the needs of agencies and programs under the parent organization’s jurisdiction, other than the statistical agency. One participant concluded that this may have “impeded the ability of [statistical agencies] to communicate openly about their work and their desired objectives.”[48] For example, participants noted that some smaller statistical agencies, especially those with limited visibility within their departments, often lack both the visibility and opportunity to share their insights on user needs directly with policymakers.

Participants also reported challenges with understanding the needs of policymakers. Participants said that since direct communication with Congress typically occurs through formal mechanisms—such as hearings or briefings—and statistical agencies are rarely invited to participate, they have limited opportunities to build reciprocal relationships with policymakers. As a result, they may struggle to demonstrate the value of statistical products or to gain insight into what public officials and their constituents need from the statistical system.

|

Statistical Agencies and Declining Access to Resources

In its 2024 report, The Nation’s Data at Risk, the American Statistical Association highlighted that while statistical agencies are generally fulfilling their legal responsibilities, their ability to innovate and meet growing data demands is constrained due, in part, to declining access to resources. The report found that over the past 15 years, funding for most statistical agencies has declined 14 percent in purchasing power, which the report attributes to their limited ability to secure authority for multiyear funding and communicate the importance of their work directly to policymakers. These financial constraints have reduced their capacity to innovate, respond to emerging data needs, and even maintain existing operations, which may affect the overall utility and integrity of the data statistical agencies collect and produce. Source: Alexkava/stock.adobe.com (image); GAO analysis of American Statistical Association, The Nation’s Data at Risk: A Call to Secure and Modernize Federal Statistical Infrastructure (Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association, July 9, 2024). | GAO‑25‑107124 |

Lack of direct budget input. At the time of the forum in August 2024, participants said that some statistical agencies did not have a formal mechanism to directly participate in the annual budget request and formulation process with their parent agencies for submission to OMB.[49] This has posed a challenge for statistical agencies embedded within larger departments. In addition, participants noted that some statistical agencies receive funding through their parent agencies’ appropriations rather than having a dedicated line-item appropriation, which could result in statistical priorities being deprioritized in favor of broader departmental objectives. This means that there was not a dedicated way for policymakers to focus on statistical agencies and their specific resource needs.

Effective in December 2024, subsequent to the forum, the Trust Regulation directs joint coordination between the statistical and parent agencies in the development of a budget request for the statistical agency. This request is a separate part of the parent agency’s annual budget request. Parent agencies are also required to ensure that the statistical agency head can participate in discussions with OMB related to that request.[50] However, the practical effects of the regulation remain to be seen, as its implementation is still in the early stages.

Opportunities to Build and Sustain Public Trust in Federal Statistics

Balancing Statistical Utility with Data Privacy

According to participants, strengthening public trust in federal statistics depends on statistical agencies balancing the production of high-quality, accessible data products that meet public and policy needs with data privacy. Forum participants urged statistical agencies to prioritize product development based on the needs of data users, rather than focusing on routine processes or producing outputs without clear value or utility.[51]

|

One Participant’s View on Statistical Product Utility “We’re here to serve people, so that they can make informed decisions about their lives, and their businesses, about the things they care about.” |

Source: Participant in the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

To do this, participants stated that statistical agencies need to better understand and anticipate the various opportunities that could enhance the system’s ability to balance statistical utility with privacy and confidentiality (see table 5).

Table 5: Reported Opportunities for Statistical Agencies to Balance Statistical Utility with Data Privacy

|

Opportunity |

Description |

|

Understand data interests |

Statistical agencies could understand the privacy expectations of data providers and utility needs of data users. |

|

Support secure data enclaves |

Statistical agencies could support access to sensitive data within secure environments. |

|

Incorporate feedback |

Statistical agencies could engage with data providers and users to refine utility and privacy trade-offs. |

|

Increase transparency |

Statistical agencies could clearly communicate data practices, limitations, and protections, which could help statistical agencies increase transparency and build public trust. |

|

Implement privacy-enhancing technologies |

Statistical agencies could implement advanced privacy techniques to safeguard data while maintaining usability. |

Source: GAO analysis of the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

Understand data interests. Participants discussed how the utility concerns of data users may differ from the privacy concerns of data providers, and understanding these differences could assist the federal statistical system’s ability to pinpoint strategies to enhance public trust. For example, data users regularly request more granular data. However, more granularity divides data into smaller subgroups which may risk the reidentification of respondents.

|

One Participant’s View on Understanding Data Interests “It is no longer simply a balance between the accuracy of the statistics and the confidentiality or privacy protection of those statistics. Rather, there is a third component to consider, which is the quantity and granularity of the statistics you release. We call this availability, and statistical agencies need to balance across all three dimensions of this triple tradeoff (accuracy, availability, and confidentiality).” |

Source: Participant in the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

|

Product Utility and Data Privacy: Census Bureau’s Disclosure Avoidance System The Census Bureau’s differential privacy simulation underscored the challenge of balancing data privacy with product utility. In 2018, the Census Bureau conducted an experiment to simulate database reconstruction that demonstrated how published data could be used to recreate confidential individual-level information, risking the reidentification of tens of millions of respondents. In response, the Bureau implemented a new Disclosure Avoidance System for the 2020 Census, incorporating statistical noise, or data uncertainty, through differential privacy to enhance confidentiality. While this approach improves privacy protection, some argue it may reduce the accuracy of demographic and geographic data, particularly at local levels. The agency has continued refining the system and plans to use differential privacy for future products. Following our recommendation, the agency acknowledged the need for a reliable schedule and, as of June 2024, provided updated timelines for disclosure avoidance activities—improving its ability to plan and track progress on protecting respondent data. Source: GAO, 2020 Census: Bureau Released Apportionment and Redistricting Data, but Needs to Finalize Plans for Future Data Products, GAO‑22‑105324 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 15, 2022) and John M. Abowd et al., “A Simulated Reconstruction and Reidentification Attack on the 2010 US Census,” Harvard Data Science Review, vol. 7, no. 3 (2025), accessed September 9, 2025, doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.4a1ebf70. | GAO‑25‑107124 |

There are privacy protections and privacy-enhancing technologies that agencies adopt to mitigate these risks. However, one forum participant said some data users believe that statistical agencies are overly degrading the usefulness of the statistics they release as they seek to keep pace with the ever-increasing disclosure risk of those statistics.[52] Stronger confidentiality protections inevitably reduce the usability of statistical products, with greater protection generally leading to greater degradation. Yet participants also emphasized that enhancing the usefulness of statistical data is not necessarily at odds with ensuring confidentiality. Balancing both needs is critical because breaches of confidentiality, such as unauthorized disclosures, and risks of reidentification of individuals from publicly released statistical data by third parties can violate privacy and undermine public trust. Federal statistical products often rely on the goodwill of the public to respond truthfully to surveys and for data providers to provide accurate information. Combined with already decreasing survey response rates, a decline in public trust could reduce the precision and accuracy of statistical products.

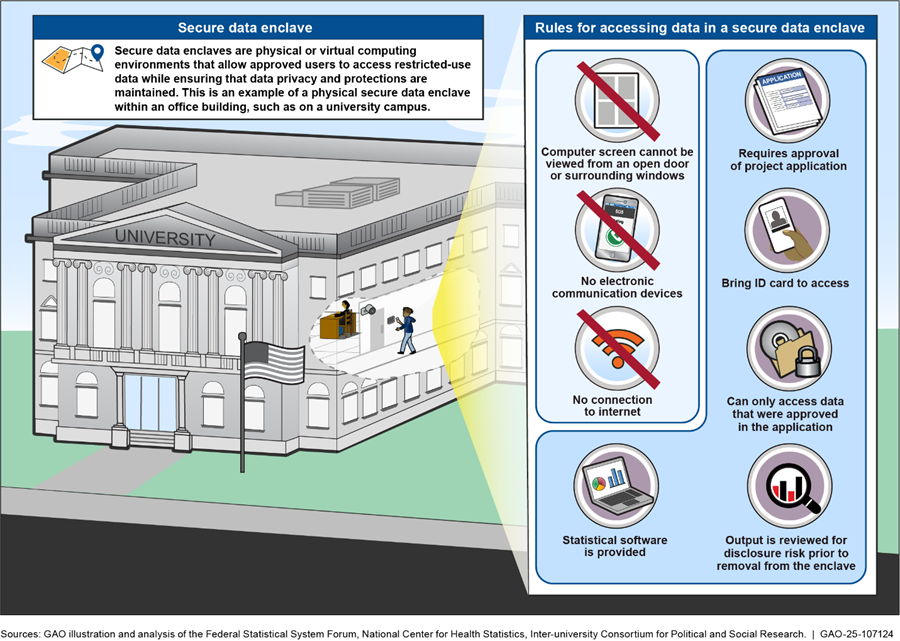

Support secure data enclaves. To strike the right balance between product utility and the goals of confidentiality, participants stressed the importance of using risk mitigation strategies during data collection, analysis, and blending, such as supporting physical and virtual data enclaves to access restricted-use data. Secure data enclaves are restricted-access computing environments that allow approved users, such as researchers at universities or government agencies, to work with confidential or sensitive datasets while ensuring that data privacy and confidentiality protections are maintained. These enclaves have strict access controls, physical and cybersecurity protections, and review processes to prevent the unauthorized use of, or reidentification of individuals within, confidential data. Secure data enclaves are sometimes accessed in a specific building or facility, as shown in figure 3.

Participants provided three illustrative examples of secure data enclaves, both physical and virtual. For example, Federal Statistical Research Data Centers are secure facilities managed by the Census Bureau in partnership with various federal statistical agencies and research institutions. They provide access to restricted-use microdata from numerous government surveys and censuses.[53] One participant also discussed the Administrative Data Research Facility, which is cloud-based platform designed to facilitate the access and analysis of confidential microdata.[54] In a virtual environment, the platform enables government agencies to link their data with other states and agencies. Participants also discussed balancing data utility and confidentiality in the National Secure Data Service, a proposed virtual secure data enclave that seeks to streamline access to restricted-use data across statistical agencies.

Incorporate feedback. Participants stressed the need to incorporate data provider and user perspectives on balancing utility and data protection concerns throughout the product cycle. For example, stakeholder feedback on acceptable risks and the usefulness of statistical products can help inform decision-makers about tradeoffs. As one participant told us, this is necessary, given the unavoidable limitations of risk mitigation.

|

One Participant’s View on Incorporating Feedback “Any data release, blended or not blended, that offers non-trivial usefulness, introduces disclosure risks. There is no method that guarantees zero disclosure risk unless it doesn’t use the data. … We need policymakers, data owners, researchers to provide input on … not only the level of risk they’re willing to accept, but also the level of usefulness of a particular data release.” |

Source: Participant in the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

Participants recommended involving privacy experts and advocates in early discussions on what to collect and what information to publish. Retrofitting products to meet confidentiality standards often results in greater losses of utility, as privacy protections are applied after the fact rather than being integrated into the design from the outset. Another participant also suggested giving data providers “a seat at the table” in decisions on how their data will be used.

Increase transparency. Participants said that greater balance between product utility, privacy, and confidentiality could be achieved through more transparency on the release and access of statistical products, as well as clear communication on how agencies plan to use data provider information and ensure provider confidentiality. A participant discussed

|

An International Example of Privacy-Enhancing Technologies

One participant provided an international example of a model for implementing privacy-enhancing technologies across statistical agencies and programs. According to the participant, Finland supports various statistical agencies by enabling secure, efficient data sharing and management across government departments, including the secure integration of survey data with administrative data. Finland’s infrastructure employs several privacy-enhancing technologies, including the implementation of synthetic data, differential privacy, and masking. Source: Thitichaya/stock.adobe.com (image); GAO analysis of the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124 |

how their agency has communicated with data providers about how data from their communities are used in statistical products and research to foster transparency and trust. Other participants noted that clarifying the difference between publicly available data versus restricted access data would be beneficial, and statistical agencies should communicate how they ensure privacy and confidentiality for both types of data.

Implement privacy-enhancing technologies. Participants raised the need to focus on privacy-enhancing technologies, such as implementing synthetic data and differential privacy techniques, to mitigate public concerns over privacy and confidentiality. As one participant noted, while these technologies are not new to the system, only recently have they been included in discussions regarding ways to balance public trust and utility of statistical products, particularly with regard to the sharing and access of statistical data. In addition to synthetic data and differential privacy methods, participants noted that statistical agencies are exploring the feasibility of secure multiparty computation and secure query systems.[55]

Strengthening Autonomy Through the Trust Regulation

The Trust Regulation aims to clarify the roles and responsibilities of statistical agencies, as well as how parent agencies should support them.[56] The regulation, which was issued in October 2024, specifies how parent agencies should support statistical agencies in carrying out their fundamental responsibilities. At the time of the forum in August 2024, participants expected that the implementation of the Trust Regulation, as proposed in August 2023, would build public trust in federal statistics by establishing a framework for statistical autonomy (see table 6).

|

Topic |

Provision |

How Autonomy Is Strengthened |

|

Coordination |

5 C.F.R. 1321.4(b-c) |

Requires regular communication between the parent and statistical agencies. Ensures parent agency policies support statistical agencies in meeting their requirements to maintain accurate information and produce relevant and timely statistical products. |

|

Branding |

5 C.F.R. 1321.4(e-f) |

Statistical agencies are to maintain distinct branding for specified public-facing communications, including stand-alone websites and statistical products. Parent agencies, in turn, must provide the necessary resources to maintain the statistical agency’s website, as well as the authority and autonomy to allow the statistical agency to manage and update its website. |

|

Budget Proposals |

5 C.F.R. 1321.4(g)(1-2) |

Statistical and parent agencies must jointly coordinate to develop a distinct budget request for the statistical agency, which is submitted as a separate component of the parent agency’s annual budget submission to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Parent agencies must also ensure that the statistical agency head can participate in OMB discussions related to that request. |

|

Resources & Capacity |

5 C.F.R. 1321.4(h) |

With statistical agencies, parent agencies must jointly develop options for addressing identified capacity needs of statistical agencies and make the necessary resources available to the extent practicable. The statistical agency is to notify OMB if it has insufficient capacity. |

|

Publishing Statistics |

5 C.F.R. 1321.5 |

Statistical agencies are to control what, when, and how data are released, consult broadly with external data users, and ensure transparency with public release schedules with the support of the parent agency. |

|

Maintaining Objectivity |

5 C.F.R. 1321.7 |

Parent agencies are to take certain steps to ensure the statistical unit’s statistical work is objective. The statistical agency must ensure equitable data access by data users, and authority to grant access to confidential statistical data. |

Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑25‑107124

Note: Issued in October 2024, OMB’s Trust Regulation, officially referred to as the Fundamental Responsibilities of Statistical Agencies and Units rule, is codified at 5 C.F.R. part 1321, implementing the statutory mandate under 44 U.S.C. 3563.

According to participants, the Trust Regulation can support public confidence in the integrity and objectivity of federal statistics. The regulation would assist statistical agencies in branding themselves as well as conducting outreach by reinforcing their commitment to autonomy, objectivity, and data confidentiality. This can include educational campaigns, transparency initiatives, and clearer messaging on the role of federal statistics in decision-making.

The Federal Statistical System Faces Challenges in Meeting Diverse User Needs That May Be Mitigated by Expanding Data Accessibility

The federal statistical system serves a diverse user base, from highly technical researchers to non-technical data users. According to participants, these users rely on federal statistical data for various applications, yet the federal statistical system faces challenges in meeting user needs. In addition, participants said that the system also faces challenges in offering appropriate support and tools tailored to different user groups. To address these challenges, participants suggested that statistical agencies can expand data access through infrastructure and service-based initiatives, while enhancing data capacity of its users by providing training, guidance, and outreach.

Challenges in Meeting Diverse Data and Accessibility Needs of Users

Meeting Diverse Data Needs

Forum participants identified challenges in meeting data needs among users (see table 7).[57]

|

Challenges |

Description |

|

Gaps in granularity |

Granular or disaggregated data may not be available for small geographic levels or for specific groups. |

|

Gaps in timeliness |

Statistical products may be delayed or may fail to keep up with emerging user needs. |

|

Gaps in relevance |

Existing statistical products may not always meet the evolving or rapidly changing needs of data users. |

Source: GAO analysis of the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

|

Constraints in Providing Granular Data Providing granular data is often limited by privacy concerns and resource constraints. Participants told us that statistical agencies must make tradeoffs between the specificity of the data they release and the risk of a breach of confidentiality. In addition, providing granular data requires significant resources, as it often involves larger sample sizes and enhanced data processing. Multiple participants noted that resource constraints limit the federal statistical system’s ability to provide users access to granular and relevant data. As one participant said, “Budgetary constraints impact our ability to innovate and to meet the growing demand for granular and interconnected data that’s essential for evidence-based policy making.” Source: Dilok/stock.adobe.com (image), GAO analysis of Federal Statistical System Forum, and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report. | GAO‑25‑107124 |

Gaps in granularity. According to participants, policymakers, state agencies, and local officials often require highly granular data—statistics at small geographic levels (e.g., city or neighborhood)—to target resources and craft policies for specific communities. Granular data can reveal local characteristics that state or national averages might conceal, enabling more effective policy interventions. According to participants, users seek more granular data, but federal statistical products often prioritize estimates for larger geographic levels, such as the national, state, and metropolitan area unemployment rates, due to their being broadly useful in supporting policy decisions for the nation and minimizing disclosure risk.[58]

Gaps in the availability of granular data for certain geographic areas present additional challenges in meeting this need. For example, a federal agency official we interviewed discussed how even after agencies blend data from multiple sources—that is, combining previously collected data sources—population, economic, and social estimates relevant to Native American populations or geography are often not represented in public products.[59] As a result, users do not always have sufficient data to support decision-making for policies and programs relevant to these groups and areas.[60]

Gaps in timeliness. Participants discussed user needs for timely data, including more frequent and real-time data updates. However, these needs may be unmet for a variety of reasons. For example, a participant and another agency official we interviewed discussed how the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns disrupted data production and delayed the release of widely used data, such as the 2020 Census.[61] Delays could also be due to less severe issues, such as waiting to receive source data from territories to produce their Gross Domestic Product estimates.[62]

One participant noted that the unanticipated population growth due to increased immigration in 2023 created a gap between published employment statistics and actual labor market conditions, highlighting the need for more dynamic and responsive data collection mechanisms. Specifically, the Current Population Survey, a dataset for employment statistics, relies on population controls—estimates of total population figures that are updated annually based on Census Bureau projections. These controls are used for weighting survey results, but they may not account for unexpected population changes. The participant cited research[63] that suggests the survey may have underestimated the total U.S. population, leading to underestimated employment levels for both U.S.- and foreign-born workers.[64]

Gaps in relevance. One participant from a statistical agency said that policymakers need relevant data and that those needs can evolve, particularly to be responsive and adaptable to rapid change. [65]

|

One Participant’s View on Relevance “Statistical policy directives… guide us as statistical agencies on what to measure and what’s important for policymakers and public and private data users. But as the world changed dramatically and rapidly with the onset of the pandemic, so has the need for a second look at what is important to measure... Users are expecting information on [rapid] change, and they want this information fast and quick…” |

Source: Participant in the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

For example, a participant noted that during the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns, demand increased for relevant data on the method and mode of learning (e.g., in-person, virtual, or hybrid) for students in primary and secondary schools. At the same time, demand continued for existing data products, such as graduation rates. As such, the COVID-19 pandemic illustrated a broader challenge for statistical agencies to maintain data relevance by balancing the production of existing information with the emerging statistics data users need.

Meeting Diverse Accessibility Needs

According to participants, there are two broad groups of data users—technical and non-technical—who differ significantly in their access to tools, expertise, and resources needed to use federal statistical data effectively. While federal, state, and local governments, businesses, and universities may have both technical and non-technical data users, technical users typically have access to computing infrastructure and analytic software and skills to analyze statistical data (see fig. 4). Non-technical users may not have these resources or skills to analyze statistical data.

According to participants, the federal statistical system faces challenges in addressing the accessibility needs of different data users (see table 8).

Table 8: Reported Challenges for the Federal Statistical System in Meeting Accessibility Needs of Certain Users

|

Challenge |

Description |

|

Streamlined access to restricted microdata |

Microdata used for research and policy evaluation are difficult for users to access. |

|

High-performance computing capacity |

Users need a high level of computing capacity to efficiently analyze and link large, complex datasets. |

|

Data integration tools |

Users need tools that facilitate the integration of statistical data with federal administrative data. |

|

Technical support from the statistical system |

Users need support to find, use, and interpret statistical products. |

|

Outreach from the statistical system |

Regular input from the broadest range of data users ensures statistical products are relevant. |

Source: GAO analysis of the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

Streamlined access to restricted microdata. According to participants, technical users may require streamlined access to microdata for detailed research and policy evaluation.[66] For example, researchers analyzing workforce trends make extensive use of microdata from surveys like the Current Population Survey and American Community Survey to study employment patterns, wages, and demographic breakdowns. The ability to access individual-level responses—stripped of personal identifiers—allows researchers to conduct in-depth research, such as obtaining custom estimates that cannot be obtained from pretabulated tables.

According to participants, while agencies produce public-use microdata, access to restricted-use data is limited. Due to confidentiality requirements, access to restricted-use data often requires approval processes and access only within secure data enclaves—making it difficult for researchers to obtain the granular person- or household-level data needed for advanced analysis. In addition, some users may be unfamiliar with the procedures for requesting access to statistical microdata, or may lack the necessary authorization, credentials, or technical infrastructure required to use secure data systems.

High-performance computing capacity. Participants said that current computing capacity of secure data enclaves does not fully serve the needs of technical users beyond the ability to access restricted microdata to create custom estimates. Technical data users need high-performance computing capacity to efficiently access and analyze large, complex datasets, enabling activities such as advanced modeling and linking different datasets. One participant noted that secure enclaves run by the Census Bureau have not fully addressed the capacity needs of technical users—including both the computational resources and system flexibility required for linking large, complex federal and state datasets.

Data integration tools. Participants called for better tools from the federal statistical system that could facilitate integration of state and local administrative records with federal administrative data to inform decision-making—a common need among technical users. According to one participant, states experienced challenges implementing the COVID-19 Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program.[67] Among other things, this program provided unemployment benefit assistance to specified workers who were not covered under existing state or federal unemployment laws, such as self-employed and gig workers. States would have benefitted from federal administrative data—such as historical employment and earnings data for individual applicants—to support unemployment claims but could not easily access these data from the sources accessible to state governments.

In addition, a participant we interviewed told us that some state programs would like to integrate individual-record level data within the state, across states, and between states and the federal government but lack the ability to do so. For example, there is no way to analyze longitudinal changes in employment when people move to a different state because states cannot access the individual-record level data of another state.

Technical support from the statistical system. According to participants, non-technical users may struggle with using the statistical products they need. For example, they may struggle to properly use geospatial data to generate estimates, which can be complex and require specific training, as well as the funds to purchase access to specialized software. Non-technical users may require enhanced support and resources to effectively navigate statistical data products, ensuring they can interpret and utilize available microdata and statistical estimates accurately; however participants told us that providing such support may be costly.

One forum participant noted that localities would like to rely on publicly available estimates from federal survey data for local management tasks, conducting needs assessments, and applying for federal grants. However, non-technical users may encounter obstacles, such as lack of access to necessary software, limited expertise, or lack of tools, such as data visualization dashboards, infographics, and interactive tools, to access these estimates.

|

One Participant’s View on Providing Technical Support “Right now, our statistical agencies primarily disseminate information in two distinct modes, public use statistics and confidential data at research data centers. There is a huge space in between these extremes. How do we develop more intermediate tiers of access that enable more people to have efficient, responsible, and secure access to versions of our data (whether aggregate statistics or extracts of microdata) in new and different ways?” |

Source: Participant in the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

Outreach from the statistical system. OMB policy calls for statistical agencies to seek input regularly from the broadest range of data users.[68] While some statistical agencies regularly engage with technical users—such as researchers—through research conferences, advisory committees, and secure data enclaves, participants told us they may need different strategies to engage with other types of users who may not regularly interact with the system, such as non-technical users.

|

One Participant’s View on Outreach “We invest a ton of money in data collection and acquisition and in statistical product development. But do we invest enough, and in the right type of resources, in helping stakeholders and users of all sorts (even those we don’t know about) who are trying and struggling to use our statistical products?” |

Source: Participant in the Federal Statistical System Forum. | GAO‑25‑107124

One participant told us that statistical agencies struggle to connect and assess the needs of non-technical data users, in part because these users may lack the time, resources, or awareness to participate in outreach efforts by statistical agencies. As a result, public engagement may not fully reflect the needs of all users, since certain groups—like researchers and other frequent data users—may have more influence in shaping priorities and in how information is communicated. In addition, limited visibility into how statistical products are used restricts statistical agencies’ ability to effectively identify and address the diverse needs of data users.

Opportunities to Expand Data Accessibility

User Access

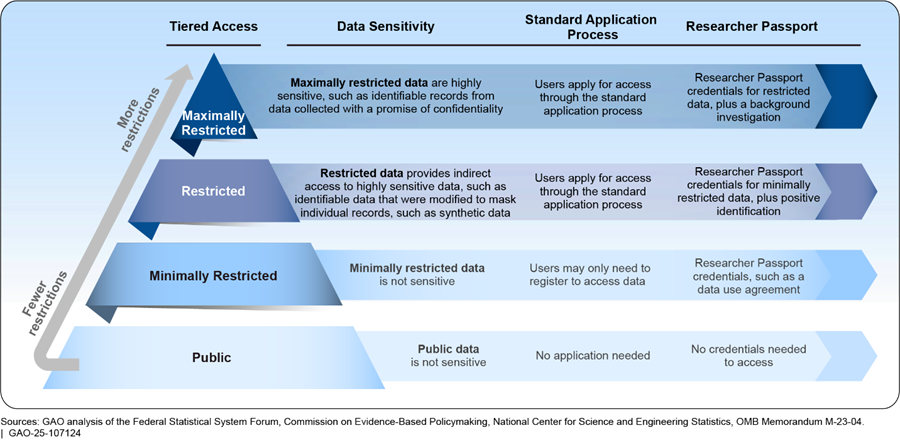

Participants said that a tiered-access model, as envisioned through a potential National Secure Data Service (NSDS), could enhance statistical data access, and could offer varying levels of data access based on users’ needs and the sensitivity of the data. The NSDS Demonstration Project, established under the CHIPS Act of 2022, provides a phased approach to test the tools, services, and processes needed to implement such a system.[69] The project is being led by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics within the National Science Foundation. Looking beyond the Demonstration Project, participants discussed potential components of a full-scale NSDS, acknowledging that these remain tentative at this stage (fig. 5).

Participants said that tiered access could allow agencies to offer multiple levels of access depending on the sensitivity of the data, which would potentially offer more flexibility than the two access levels (public-use and restricted-use) currently available. For example, participants discussed that restricted tiers could include the ability to link statistical data with administrative data and analyze restricted-use microdata at more restricted tiers and access aggregated datasets and use synthetic data for exploratory analysis at less restricted tiers.

In addition to tiered access, a potential NSDS could include a modified approach to the current Standard Application Process[70]—to standardize the process for users to apply for access to data—and Researcher Passport—to standardize credentials for specific levels of access.[71] Once credentialed, data users with approval to access restricted data from multiple agencies could do so without having to repeat the application and credentialing process for each agency.

For non-technical users, participants said a potential NSDS could offer concierge services to provide a pathway to ask questions about finding, using, and interpreting public federal statistical products through an online portal. Specifically, the services could provide tailored guidance and technical support to help non-technical users navigate complex statistical products based on their specific needs.