DISASTER CONTRACTING

Opportunities Exist for FEMA to Improve Oversight

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107136. For more information, contact Travis J. Masters at (202) 512-4841 or masterst@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107136, a report to congressional requesters

Opportunities Exist for FEMA to Improve Oversight

Why GAO Did This Study

FEMA obligates billions of dollars annually on contracts to respond to natural disasters. These include contracts for providing temporary housing to those affected by disasters.

GAO was asked to review FEMA’s use and oversight of its disaster contracts. This report examines (1) how and to what extent FEMA used contracts to support its response and recovery efforts from fiscal years 2018 through 2023; (2) steps FEMA took to provide oversight of contractor performance; and (3) the extent to which FEMA identified contract oversight staffing needs, among others.

GAO analyzed contracting data on FEMA’s obligations. GAO selected a nongeneralizable sample of 15 contracts and orders across three disasters. At the time of selection, 12 selected contracts accounted for 42 percent of total contract obligations across the three disasters. GAO subsequently selected three additional contracts to review ongoing oversight activities. GAO also reviewed training and staffing documents, conducted site visits to observe contract performance and oversight activities, and interviewed agency officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making seven recommendations, including that FEMA reiterates to oversight staff the importance of documenting contractor performance and takes steps to ensure those performing oversight duties have proper certification and authorization; and that DHS incorporates potential risks into its staffing model. DHS and FEMA concurred with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

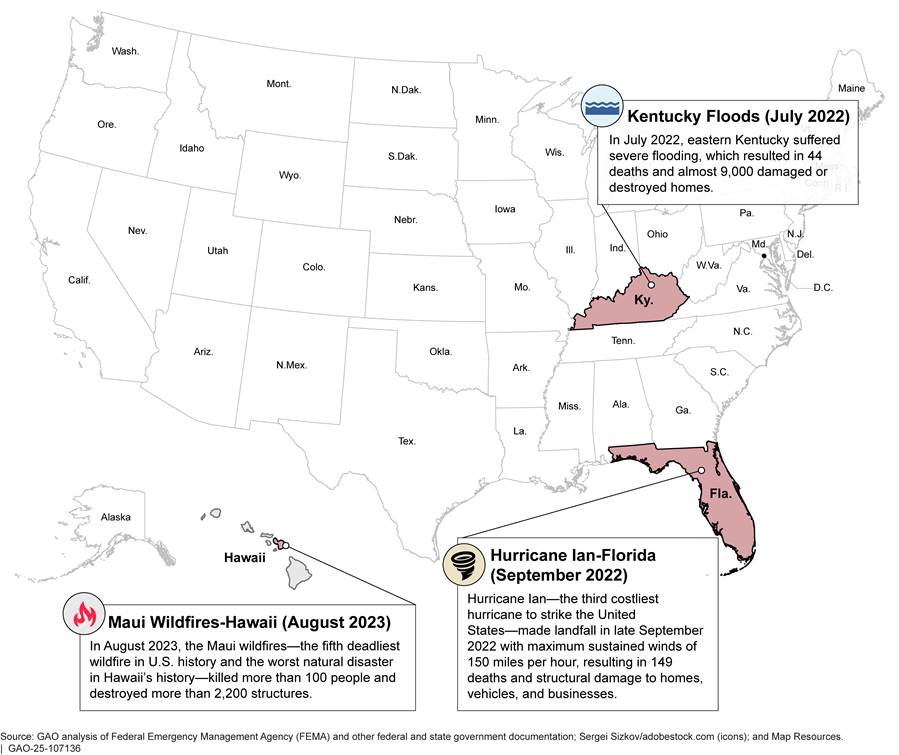

U.S. states and territories have experienced several devastating and costly natural disasters requiring aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). From fiscal years 2018 through 2023, FEMA obligated more than $10 billion on contracts—mostly for services, such as housing inspections—to conduct response and recovery efforts. Three disasters in that time frame include the Kentucky floods, Hurricane Ian, and the Maui wildfires. Contract obligations for these disasters totaled more than $1 billion.

GAO reviewed 15 contracts from the three disasters and found that FEMA took oversight steps, such as assessing contractor reports of work performed and conducting site inspections. However, FEMA did not always document oversight activities or details of contractor performance, such as whether a contractor performed work within the time frame specified in the contract. Without this documentation, FEMA and others may not know whether FEMA received the level and quality of services or goods that it purchased.

Additionally, some FEMA staff performed oversight without the required authorization or certification, which is not in accordance with Department of Homeland Security (DHS) guidance or FEMA policy. For example, some FEMA housing specialists conducted activities like filling out contactor assessment forms without having received certification or authorization for performing such tasks. Without FEMA identifying who across the agency is currently performing contract oversight duties and ensuring they are appropriately certified and authorized, there is increased risk that FEMA has unqualified staff performing contract oversight. These staff may not properly assess the goods and services received in accordance with the contract.

FEMA uses DHS’s staffing model to identify certain contract oversight staff needs. This model, however, does not fully adhere to staffing model key principles. For instance, the model does not incorporate risk factors, such as attrition. Doing so would better position FEMA to retain the staff it needs.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

COR |

contracting officer’s representative |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FAC-C (Professional) |

Federal Acquisition Certification in Contracting |

|

FAC-COR |

Federal Acquisition Certification for Contracting Officer’s Representatives |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

FPDS |

Federal Procurement Data System |

|

OCPO |

Office of the Chief Procurement Officer |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 6, 2025

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Timothy M. Kennedy

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Emergency Management and Technology

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Shri Thanedar

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Oversight, Investigations, and Accountability

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Troy A. Carter, Sr.

House of Representatives

The Honorable Glenn F. Ivey

House of Representatives

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is the federal agency with primary responsibility for coordinating disaster response and recovery activities. FEMA provides direct support to disaster response and recovery efforts and frequently contracts with the private sector to obtain goods and services to carry out its operations. Use of contracts, including advance contracts that are awarded prior to a disaster, can play a key role in the aftermath of a disaster. For example, we previously reported that FEMA obligated over $3.1 billion on contracts to support response and recovery efforts for the 2017 hurricane season.[1]

The contracting officer has the authority to enter into, administer, or terminate contracts, and to delegate certain oversight activities to a contracting officer’s representative (COR), according to federal acquisition regulations and agency policy. These oversight activities can include conducting site inspections and reviewing contractor-produced documentation. After a contract is awarded, effective contract management and oversight are essential to ensuring the government receives the goods and services for which it has contracted. To effectively manage its contracts, FEMA needs a sufficient and properly trained contracting workforce. We and the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Office of the Inspector General previously identified acquisition workforce and contract oversight challenges at FEMA.[2]

You asked us to assess FEMA’s use and oversight of its disaster contracts. This report examines (1) how and to what extent FEMA used contracts related to natural disasters to support its response and recovery efforts from fiscal years 2018 through 2023; (2) the steps FEMA took to provide oversight of contractor performance on selected contracts and any challenges encountered; and (3) the extent to which FEMA identified and monitored contract oversight training and staffing needs.

To assess how and to what extent FEMA used contracts related to natural disasters to support its response and recovery efforts from fiscal years 2018 through 2023 (the most recent year of data available during our review), we merged data from the Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) and FEMA’s contracting writing system, known as the Procurement Request Information System Management. We analyzed the data to identify characteristics of disaster and emergency contracts such as total obligations, contract type, and obligations by product or service code. For the purposes of this review, we excluded FEMA’s COVID-19-related contract obligations.[3] To assess the reliability of the FPDS and Procurement Request Information System Management data, we reviewed FPDS and FEMA documentation, interviewed agency officials, conducted electronic data testing to look for obvious errors or outliers, and compared documentation from contracts and orders we selected for review to FPDS data. Based on the steps we took, we determined that the FPDS data and the Procurement Request Information System Management data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report.

To assess the steps FEMA took to provide oversight of contractor performance on selected contracts and any challenges encountered, we selected a nongeneralizable sample of 15 contracts and orders across three disasters—Hurricane Ian, the 2022 Kentucky floods, and the 2023 Maui wildfires.[4] Our disaster selection factors included selecting recent disasters (fiscal years 2022 and 2023) and those with high contract obligations; and obtaining a mix of natural disaster types, such as a hurricane, flood, and fire. Our contract and order selection criteria included selecting those with the highest obligations and with at least 6 months of contractor performance, to allow sufficient time for contract oversight activities. Hereafter, we refer to these contracts and orders collectively as contracts, unless otherwise specified.[5] See appendix I for more details on the selected contracts.

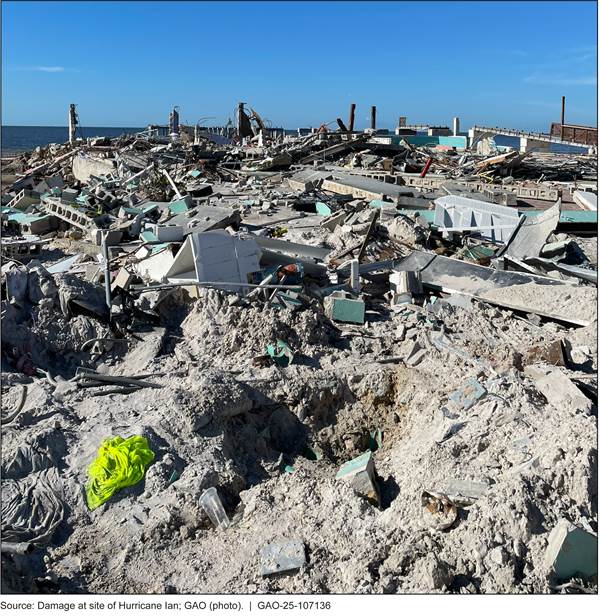

For each selected contract, we identified and analyzed contract oversight documentation, requirements, and performance standards. We considered a contract as incorporating performance-based acquisition methods if it included quantifiable performance metrics, thresholds, and the method of surveillance to measure contractor performance. We interviewed FEMA contracting officers and CORs to understand the oversight steps they took and to identify oversight challenges. We compared the oversight steps in the contract to related documentation; the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR); DHS and FEMA acquisition policies related to assessing contractors’ performance; and standards for internal control in the federal government.[6] We determined that the information and communication and monitoring components of internal controls were significant to this objective. Additionally, we determined that the principles that management should use and internally communicate quality information to achieve objectives, and establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate the results, were also significant. We conducted site visits in April 2024 to areas in Florida damaged by Hurricane Ian and in May 2024 to the site of the Maui wildfires to observe contract performance and oversight activities.[7]

To assess the extent to which FEMA identified and monitored contract oversight training needs, we analyzed contract oversight responsibilities outlined in DHS and FEMA policy and guidance and compared them against required contract oversight training materials. We also reviewed the FAR and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance on Federal Acquisition Certification in Contracting (FAC-C (Professional)) and Federal Acquisition Certification for Contracting Officer’s Representatives (FAC-COR) requirements. To assess the extent to which FEMA identified its contract oversight staffing needs, we analyzed DHS’s staffing model—which FEMA uses—and compared the model against selected staffing model key principles we identified in prior work and standards for internal control.[8] We determined that the control activities component of internal controls was significant to this objective, along with the principle that management should design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks. We interviewed DHS officials responsible for maintaining and validating the staffing model and FEMA officials that used it.[9] We analyzed data on the number of FEMA contracting officers and CORs and the extent to which these staff had the proper certifications. To assess the reliability of the data, we compared the data to the CORs’ certification documentation associated with our sample of selected contracts. We also interviewed FEMA officials that used the data to discuss any potential data reliability issues. We determined that the contracting officer and COR certification data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report. See appendix I for additional details about our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The United States suffered several devastating natural disasters from 2018 through 2023, including hurricanes, floods, and wildfires. Three recent disasters during that time frame that resulted in significant damage included the Kentucky floods and Hurricane Ian in 2022 and the Maui wildfires in 2023. See figure 1 for a timeline and key information about these disasters.

When disasters hit, state and local entities are typically responsible for

carrying out disaster response efforts. The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief

and Emergency Assistance Act, as amended, establishes a process by which the

Governor of the affected state or the Chief Executive of an affected Indian

tribal government may request a presidential major disaster declaration to

obtain federal assistance.[10]

According to the DHS National Response Framework—a guide to how the federal

government, states and localities, and other public and private sector

institutions should respond to disasters and emergencies—the Secretary of

Homeland Security is responsible for ensuring that federal preparedness actions

are coordinated to prevent gaps in the federal government’s efforts to respond

to all major disasters, among other emergencies.[11] The framework also designates FEMA

as the lead agency to coordinate the federal disaster response efforts across

30 federal agencies. The Administrator of FEMA serves as the principal advisor

to the President, the Secretary of Homeland Security, and the National Security

Council regarding emergency management.

FEMA’s Contracting Workforce

In FEMA’s role as the lead coordinator of federal disaster response efforts across federal agencies, its contracting workforce plays a key role in awarding and overseeing contracts. FEMA’s contracting efforts are supported by its contracting workforce within FEMA’s Office of the Chief Component Procurement Officer, located in FEMA headquarters and in its 10 regional offices. The office provides program offices with acquisition support and can allocate contracting resources as needed throughout the regional offices. The office is led by FEMA’s Chief Component Procurement Officer, who oversees FEMA’s contracting officers as the Head of the Contracting Activity.

Contract oversight is largely the responsibility of the contracting officer and the COR appointed to a particular contract. At DHS, contracting officers may also appoint technical monitors to assist in contract oversight. Contracting officers, CORs, and technical monitors all serve important roles in contract oversight, as detailed below.

· Contracting officers. The contracting officer has authority to enter into, administer, and terminate contracts and make related determinations. The contracting officer also has the overall responsibility for ensuring the contractor complies with the terms of the contract. As part of their responsibilities, the contracting officer may delegate certain oversight responsibilities to a COR, such as reviewing contractor invoices.

· CORs. CORs assist in the monitoring and administration of a contract. They are often selected based on their knowledge of the program, and they are required, according to the FAR, to be certified.[12] CORs must complete a variety of classes to achieve this certification, including classes on how to conduct contract oversight.[13] Per DHS policy, a contracting officer must appoint a COR to every contract award that is above the simplified acquisition threshold, which is generally $250,000.[14] CORs do not have the authority to make any commitments or changes that affect price, quality, quantity, delivery, or other terms and conditions of the contract.

· Technical monitors. According to DHS and FEMA policy, in addition to a COR, a contracting officer may appoint a technical monitor. Technical monitors can perform contract oversight duties similar to those of a COR, including monitoring, surveillance, and quality assurance. DHS and FEMA policy state that technical monitors must be certified at the same level as the COR on a given contract, and contracting officers must also issue appointment letters for all technical monitors.

Advance and Post-Disaster Contracts

The Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006 required FEMA to establish advance contracts—those that are established prior to disasters and that are typically needed to quickly provide life-sustaining goods and services in the immediate aftermath of disasters.[15] According to FEMA’s 2007 advance contracting strategy, the agency should maximize the use of advance contracts to the extent they are practical and cost-effective, which should help preclude the need to procure goods and services under unusual and compelling urgency. As of fiscal year 2024, FEMA has 109 advance contracts in place covering goods and services such as tarps, food and water, information technology and communication support, and housing and lodging assistance. In addition to advance contracts, FEMA uses post-disaster contracts, which are those that are awarded after a disaster occurs.[16]

Performance-Based Acquisition and Quality Assurance Surveillance Plans

A key mechanism for oversight of service contracts is performance-based acquisition, which relies on measurable performance standards and a method of assessing a contractor’s performance against those standards.[17] Measurable performance standards and financial incentives are meant to encourage competitors to develop and implement innovative and cost-effective methods of performing the work. The FAR directs federal agencies to use performance-based acquisition to the maximum extent practicable when acquiring certain services.[18] The FAR Council described performance-based contracts as defining agency needs in terms of the desired outcome rather than the manner by which the contractor completes the work. The acquisition’s requirements and desired outcomes should be identified and the contract should include measurable performance standards that enable the government to determine whether the contractor has met the performance objectives.[19]

The Homeland Security Acquisition Manual requires the use of a quality assurance surveillance plan when the government describes the required results from a contract rather than outlining how the work is to be accomplished (referred to as a performance work statement). Quality assurance surveillance plans are meant to specify all of the work that requires surveillance and the method of surveillance the government will use. These plans often include a matrix outlining the performance objectives and metrics the contractor is required to meet and any enforcement penalties the government can levy if the contractor does not satisfy the performance requirements. As such, the elements included in the quality assurance surveillance plans are key to providing the government with the tools to conduct oversight for performance-based service contracts.

Prior GAO Reports on FEMA Contracting

Over the past decade, we have reported on FEMA’s oversight of disaster contracts and found gaps that could impede the agency’s ability to monitor contractor performance. For example, in January 2014, we found that FEMA did not develop quality assurance surveillance plans and did not complete annual contractor performance assessments for some contracts.[20] We recommended that FEMA determine the extent to which quality assurance surveillance plans were not developed for its contracts, determine the reasons why, and develop additional actions to ensure that quality assurance surveillance plans are developed for future awards. We made a similar recommendation to FEMA to ensure that it had complete and timely information about past contractor performance. FEMA concurred and addressed these recommendations by reviewing its contracts to determine the extent to which these issues were prevalent, and taking action to ensure that it followed these oversight steps, such as developing a best practices guide for its CORs.[21]

In September 2015, we reported that FEMA did not have a sufficient process in place to prioritize its disaster workload and cohesively manage its contracting officers.[22] As a result, we issued eight recommendations to FEMA, all of which the agency concurred with. FEMA addressed seven of these recommendations.[23] For example, FEMA updated its standard operating procedures to address how contracting staff prioritize workloads prior to being deployed to a disaster.

We have also reported on FEMA’s workforce, including its contracting workforce. For example, in May 2023, we reported that FEMA had an overall 35 percent staffing gap across different positions within the agency.[24] The contracting staff had a lower staffing gap (15 percent) than some of the other positions. We made three recommendations to FEMA, all of which the agency concurred with and addressed. For example, FEMA took steps to discuss and develop documented plans evaluating hiring efforts to address staffing gaps in the agency’s disaster workforce.

FEMA Obligated Billions of Dollars from 2018 through 2023 to Respond to Natural Disasters

Based on our analysis of FPDS and FEMA procurement system data, FEMA obligated billions of dollars from fiscal years 2018 through 2023, primarily for services to respond to natural disasters. About three quarters of these obligations were used to address damage due to hurricanes (rather than other types of disasters). About 83 percent of these obligations were used to procure services, such as disaster planning support and installation of plumbing, heating, and waste disposal systems. We found that FEMA’s competition rate—the percentage of total disaster-related obligations reported for competitive contracts—was between 78 and 100 percent for the period covered by our analysis.[25] FEMA increasingly relied on fixed-price contracts on which the government pays a fixed, or in appropriate cases, an adjustable price, for a good or service.[26] The proportion of FEMA’s obligations on contracts awarded to small businesses varied over this time, ultimately representing a higher proportion of total obligations in fiscal year 2023 than in fiscal year 2018.

FEMA Obligated More Than $10 Billion on Contracts Related to Natural Disasters

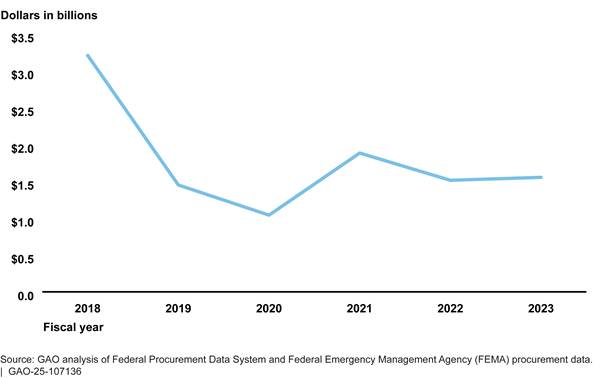

Based on our analysis of FPDS and FEMA procurement system data, FEMA obligated about $1.7 billion annually on contracts related to natural disasters, on average, from fiscal years 2018 through 2023, for a total of more than $10 billion over the 6-year period. See figure 2 for details on FEMA’s annual obligations during this time frame.

Figure 2: FEMA’s Annual Obligations on Contracts Related to Natural Disasters, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: For the purposes of this review, GAO excluded COVID-19-related

obligations.

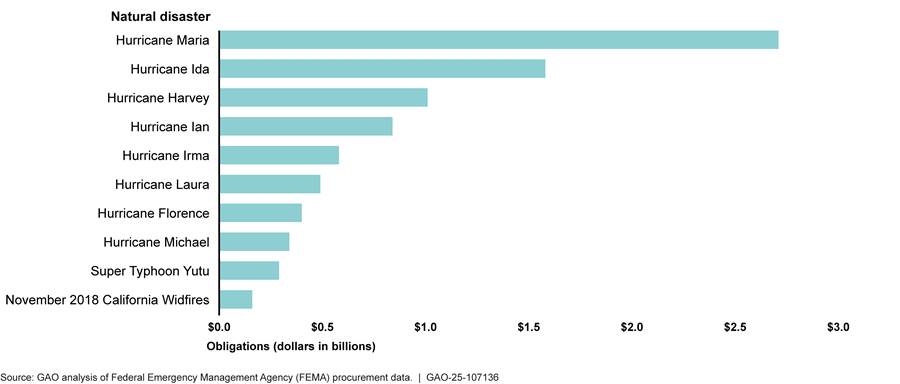

Most of the obligations identified above were for hurricane relief, with Hurricane Maria—which made landfall on Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands in 2017—accounting for $2.7 billion of the total. Three of the top five disasters, as measured by total contract obligations from fiscal years 2018 through 2023, occurred in 2017. These obligations demonstrate the ongoing response and recovery needs for catastrophic disasters years after these disasters occur. See figure 3 for details on the 10 natural disasters with the highest FEMA obligations on contracts ($8.4 billion across all 10 disasters) during this time frame.

Figure 3: Ten Natural Disasters with the Highest Obligations by FEMA on Related Contracts, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: For the purposes of this review, GAO excluded

COVID-19-related obligations. GAO also excluded obligations on disaster-related

contracts awarded by other agencies.

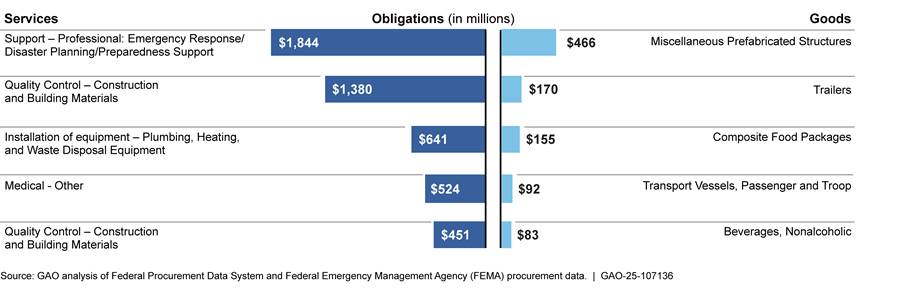

Service contract obligations accounted for about 83 percent of FEMA’s total contract obligations for natural disaster response and recovery for the period covered by our analysis. The remaining 17 percent of the obligations were for goods. See figure 4 for the services and goods with the highest contract obligations during this time frame.

Figure 4: Services and Goods with the Highest FEMA Obligations on Contracts Related to Natural Disasters, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: The types of services and goods in this figure are

derived from the Federal Procurement Data System’s product and service codes.

These codes describe the products and services purchased by the federal

government. For the purposes of this review, GAO excluded COVID-19-related

obligations.

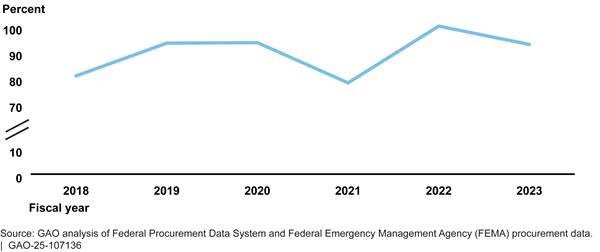

We found that FEMA’s competition rate—the percentage of total obligations reported for competitive contracts—was between 78 and 100 percent for the period covered by our analysis.[27] Competition is a cornerstone of the acquisition system and a critical tool for achieving the best possible return on investment for taxpayers. The benefits of competition in acquiring goods and services from the private sector are well established. Competitive contracts can help save the taxpayer money, improve contractor performance, curb fraud, and promote accountability for results.[28] Federal statute and acquisition regulations generally require that covered contracts be awarded on the basis of full and open competition. See figure 5 for the percent of FEMA’s obligations on competitive contracts from fiscal years 2018 through 2023.

Figure 5: Percent of FEMA’s Obligations on Contracts Related to Natural Disasters that Were Competed, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: Competitive contracts included contracts and orders

coded in the Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) as “full and open

competition,” “full and open after exclusion of sources,” and “competed under

simplified acquisition procedures,” as well as orders coded as “subject to fair

opportunity,” “fair opportunity given,” and “competitive set aside.”

Noncompetitive contracts included contracts and orders coded in FPDS as “not

competed,” “not available for competition,” and “not competed under simplified

acquisition procedures,” as well as orders coded as an exception to “subject to

fair opportunity,” including “urgency,” “only one source,” “minimum guarantee,”

“follow-on action following competitive initial action,” “other statutory

authority,” and “sole source.” For the purposes of this review, GAO excluded

COVID-19-related obligations.

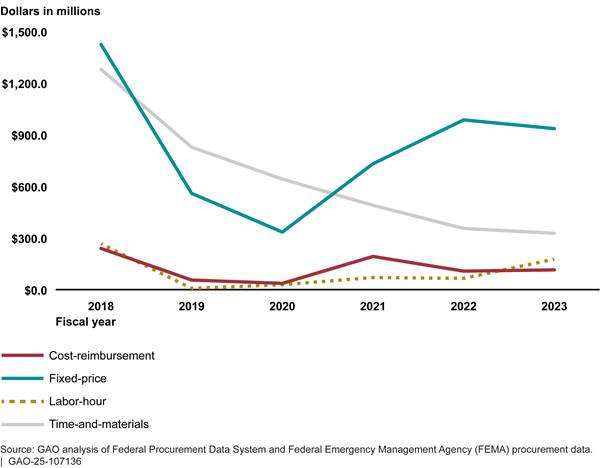

FEMA Has Increasingly Relied on Fixed-Price Contracts

Based on our analysis of FPDS and FEMA procurement system data, FEMA’s obligations on fixed-price contracts grew since fiscal year 2020, while obligations on time-and-materials contracts declined over the time frame we assessed.[29] One type of fixed-price contract—firm-fixed-price—presents the least cost risk to the government as it pays a fixed price for a good or service, and the contractor generally assumes the risk of a cost overrun.[30] Time-and-materials contracts are considered higher-risk to the government than fixed-price contract types because the government is not guaranteed a completed end item or service, and these contracts provide less incentive to the contractor to work efficiently or control costs. A labor-hour contract is a variation of a time-and-materials contract, differing only in that the contractor does not supply materials. Cost-reimbursement contracts involve higher-cost risk for the government because the government pays a contractor’s qualifying costs of performance up to an established ceiling regardless of whether the work is completed.[31] See figure 6 for FEMA’s obligations by contract type from fiscal years 2018 through 2023.

Figure 6: FEMA Obligations on Contracts Related to Natural Disasters by Contract Type, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: For the purposes of this review, GAO excluded

COVID-19-related obligations.

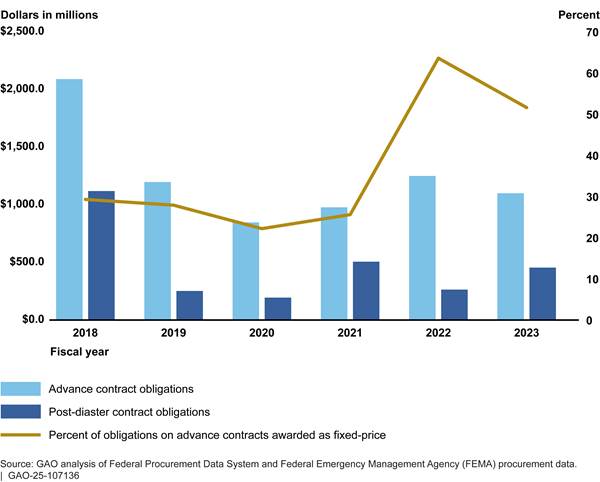

This trend in the obligations on fixed-price contracts can also be seen in the contracts FEMA awarded prior to a disaster—known as advance contracts. In fiscal year 2018, 29 percent of FEMA’s total obligations on advance contracts were on those that used a fixed-price approach—that percentage has since increased to about 52 percent in fiscal year 2023.[32] See figure 7 for FEMA’s obligations on advance contracts and contracts awarded in response to a specific disaster, referred to as post-disaster contracts, and the percent of obligations on advance contracts that were awarded with fixed-price terms during this time frame.

Figure 7: FEMA Obligations on Advance and Post-Disaster Contracts Related to Natural Disasters and the Percent of Advance Contracts Awarded as Fixed-Price, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: For indefinite-delivery contracts or blanket purchase agreements—two contract and agreement types used as advance contracts—obligations occur when the order or call is placed to respond to a disaster. FEMA and other agencies may also award new contracts to support disaster response efforts following a disaster declaration. In GAO’s prior work, FEMA officials said that these post-disaster contract awards may be required, for example, if advance contracts reach their ceilings, or if goods and services that are not suitable for advance contracts are needed. See GAO‑19‑93. For the purposes of this review, GAO excluded COVID-19-related obligations.

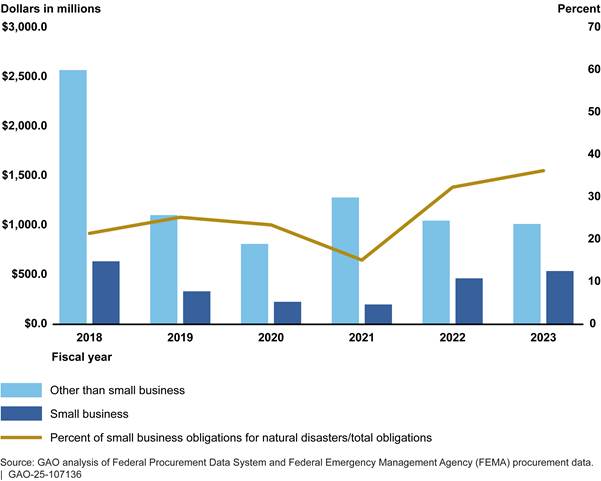

The Proportion of Obligations on Contracts FEMA Awarded to Small Businesses Varied

Based on our analysis of FPDS and FEMA procurement system data, the proportion of FEMA’s obligations on natural disaster-related contracts awarded to small businesses varied over this time frame, ultimately representing a higher proportion of obligations—over 34 percent—by 2023.[33] We previously reported that small businesses are an important driver of the nation’s economic growth.[34] See figure 8 for FEMA’s obligations on natural disaster-related contracts to small and other than small businesses, and small business obligations on natural disaster-related contracts as a percent of total obligations during this time frame.

Figure 8: FEMA Obligations on Contracts Related to Natural

Disasters with Small and Other Than Small Businesses, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: For the purposes of this review, GAO excluded

COVID-19-related obligations.

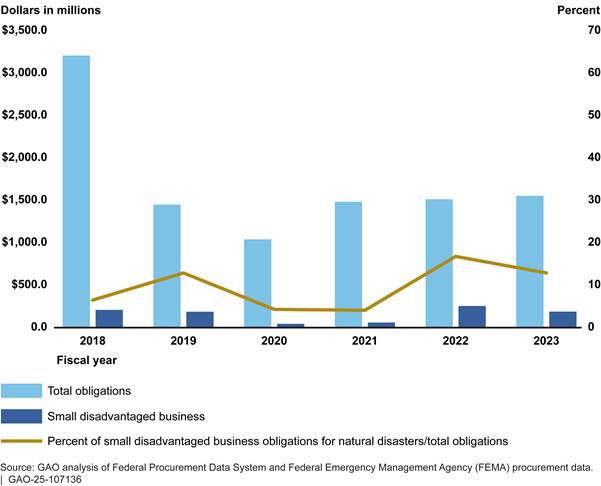

Obligations on natural disaster-related contracts awarded to small disadvantaged businesses were 4 percent of total FEMA obligations in fiscal years 2020 and 2021, but increased to about 13 percent in fiscal year 2023.[35] See figure 9 for FEMA’s obligations on natural disaster-related contracts to small disadvantaged businesses and as a percent of total obligations during this time frame.

Figure 9: FEMA Obligations on Contracts Related to Natural Disasters with Small Disadvantaged Businesses, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: For the purposes of this review, GAO excluded

COVID-19-related obligations.

FEMA Missed Opportunities to Better Assess Performance and Improve Oversight for Selected Contracts

FEMA conducted various oversight steps for the 15 contracts we selected. However, we identified five instances in which FEMA missed opportunities to better assess contractor performance by improving the use of performance-based acquisition methods. Additionally, we found eight instances in which FEMA assigned individuals to conduct contract oversight who lacked the required certification or had not received the contracting officer’s authorization to perform oversight tasks.

FEMA Took Various Approaches to Oversight

FEMA performed various oversight steps for our 15 selected contracts. This included collecting and assessing contractor-produced reports on a recurring basis; outlining performance standards, and holding a contractor accountable for meeting those standards; shadowing contracted inspectors; conducting unannounced site inspections; and reviewing sign-in sheets and invoices. For example:

· For a $47 million call center contract for Hurricane Ian recovery, FEMA used specific, quantifiable performance metrics, thresholds, and a plan detailing the method of surveillance to oversee the contract. The purpose of the contract was to provide surge support to FEMA’s National Processing Service Center staff to help with increased call volume, which FEMA often relies on during periods of high disaster activity. The contractor staff were to answer calls from survivors and organizations and assist them in applying for disaster assistance, such as FEMA’s Individual Assistance and Public Assistance grants.[36] The COR told us that they applied the monetary disincentives specified in the contract when the contractor did not meet the performance metrics, such as deducting 1 percent from the total invoice when the contractor did not meet sufficient staffing levels within required time frames. The contract contained clear and measurable performance metrics, such as expectations for how quickly calls were answered, how many times a caller hung up before receiving assistance, and the number of hours worked. There were thresholds for meeting these metrics and different methods of surveillance that the COR could use to monitor them. The COR for this contract told us that the monetary disincentives for not meeting the performance standards were effective for improving contractor performance. For example, FEMA officials said the contractor made investments to improve its quality control to avoid the disincentives, and the COR told us that the contractor performed well and was responsive.

· For a temporary housing contract with nearly $89 million in obligations that involved installing, maintaining, and deactivating housing units for survivors of the Kentucky floods, FEMA used individual performance standards for each site. The technical monitors scored the contractor in specific areas of performance, such as the level of customer service, the quality of repairs performed, and how thoroughly the contractor deactivated the housing unit and left the site as it was found. FEMA then tabulated monthly averages for all the quality assurance surveillance plan forms. FEMA used these scores to track and understand contractor performance over time and provide specific, detailed evidence of the extent to which the contractor met performance requirements. The COR for this contract informed us that the technical monitors went into the field to fill out the quality assurance surveillance plan forms and graded the contractor’s maintenance in real time.

·

For a housing inspection contract with $2 million in obligations,

the contractor was responsible for conducting housing inspections for survivors

to help inform FEMA’s grant decisions for the Maui wildfires. The COR and

technical monitor graded the contractor’s performance against the quality

assurance surveillance plan’s performance metric, collected biweekly quality

control reports, and had inspection coordinators prepare reports on production

levels. FEMA personnel also told us that they shadowed contracted inspectors on

occasion to monitor their disaster reporting, make corrections, and address any

disaster-specific issues not addressed in guidance. As a result of these

efforts, the COR told us that the contractor met all the performance

requirements for the metric listed in the quality assurance surveillance plan.

FEMA Missed Opportunities to Better Assess Contractor Performance in Selected Contracts

Although 14 of the 15 contracts we reviewed were for services, nine of those 14 were identified as performance-based acquisitions, including the prior three examples.[37] As noted previously, the FAR states that agencies generally must use performance-based acquisition methods to the maximum extent practicable for service contracts. The FAR also requires performance-based service contracts to include measurable performance standards and states that a quality assurance surveillance plan should specify all work requiring surveillance and the method of surveillance. We found that FEMA did not fully implement performance-based acquisition methods in three of the nine contracts that were structured as performance-based acquisitions, such as by failing to fully use the quantifiable performance metrics, thresholds, or the method of surveillance described in the contract to measure performance. FEMA officials we spoke with on these contracts were unaware that the contract’s quality assurance surveillance plan should be prepared in conjunction with the performance work statement, or said they chose not to use it. Additionally, we found two instances where FEMA did not use performance-based acquisition methods on a service contract but told us either it would have been beneficial to do so or they did not consider it. Without reiterating to contracting officers and CORs the preference for and purpose of fully implementing performance-based acquisition methods for service contracts, FEMA is missing opportunities to obtain a more complete and quantifiable understanding of contractor performance and more detailed information to inform how it structures and oversees future contract awards.

Below are some examples where FEMA did not fully implement performance-based acquisition methods:

· On a $185 million public assistance inspections task order in support of the Hurricane Ian recovery identified as a performance-based acquisition, the task order included performance metrics to assess the quality of the inspection and whether the services were completed on time—two of the main performance goals of the task order. However, there is no documentary evidence that the COR assessed the contractor’s performance against these metrics and thus evidence that FEMA officials knew the quality and timeliness of contractor-performed public assistance inspections. FEMA provides public assistance grant funds for a variety of recovery activities and projects, including the repair and reconstruction of damaged schools, hospitals, and other public infrastructure. This contract was for contractor personnel to perform inspections of public infrastructure to determine eligibility for public assistance grant funds.

FEMA officials administering this contract told us they generally focused on reviewing and approving contractor invoices and reports and took action against contractor employees who were not performing well—such as an inspector caught sleeping on the job. A technical monitor staffed to this contract filled out two contractor performance evaluation worksheets during the contract’s period of performance, but they contained no documented use of the performance metrics to develop the ratings. The evaluation worksheets were the only FEMA-produced documentation officials provided us when we asked about oversight. Additionally, the base contract’s quality assurance surveillance plan included additional contractor performance documents that officials agreed could have provided useful information had they been filled out as the contractor performed the work. These documents included a customer complaint record and a discrepancy report. Instead, the COR filled out these documents and provided them to us after our site visit, which was 14 months into the contract’s period of performance.

· Officials on an approximately $1 million cargo flight task order for the Maui wildfires, identified as a performance-based acquisition, did not use the base contract’s quality assurance surveillance plan when administering the task order. This task order involved the use of contracted flights to return cargo from Maui to various states in the continental United States. The COR informed us that due to the task order’s 7-day period of performance, rather than use the base contract’s quality assurance surveillance plan, they decided to assess the contractor on the requirements listed in the task order’s statement of work, such as providing hourly flight status updates and ensuring enough flight crew personnel. FEMA officials told us they conducted their oversight via email, text message, and flight tracking software.

· An $80 million responder lodging contract—which involved the use of contractors to identify and book hotel rooms for FEMA responders in support of the Maui wildfires response and recovery—was not structured as a performance-based acquisition and did not have measurable performance metrics or a quality assurance surveillance plan. The COR informed us that a quality assurance surveillance plan would have been helpful to conduct oversight and to hold the contractor accountable. The COR told us they experienced challenges with contractor invoices that took weeks to fix and received contractor-produced documentation that lacked adequate detail. The contract was not required to have an acquisition plan, which is where the determination to follow performance-based acquisition methods is typically documented, and the contracting officer did not consider structuring the contract as a performance-based acquisition.

In addition to not fully implementing performance-based acquisition methods, we also observed three instances of FEMA not documenting the oversight activities performed. In the examples below, the CORs were unaware of the importance of documenting their oversight of contractor performance or failed to do so.

Agency oversight policies do not require a specific level of documentation of oversight activities; rather, CORs have the discretion to determine what oversight documentation is necessary for a particular contract. Typically, a contract with a performance work statement does not require FEMA officials to produce a specific level of documentation of its oversight activities. However, COR guidance and the COR appointment letter include documenting surveillance activities of contractor performance as one of a COR’s duties. Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should evaluate and document the results of ongoing monitoring and separate evaluations to identify issues.[38] Furthermore, FEMA’s COR training stresses the importance of documentation during contract oversight, including emphasizing that monitoring is not sufficient unless it is documented. The examples in which FEMA did not fully document all of its oversight are as follows:

· Officials overseeing a nearly $51 million responder lodging contract—which involved the use of a contractor to transport, set up, and maintain housing for FEMA staff on the ground responding to the Kentucky floods—did not keep documentation demonstrating that the contractor met all of the performance requirements. FEMA officials developed performance requirements, metrics, and a method of surveillance, in line with the requirements for a performance-based acquisition, but the COR told us they generally did not use them. While FEMA collected evidence demonstrating that the contractor met the requirement to resolve maintenance issues within a set time frame, the COR informed us that most of their oversight was conducted visually with an informal checklist. Additionally, while there were quantifiable metrics for the contractor to set up the sites, such as completing construction within 36 hours of receiving the order, the COR relied mainly on contractor-produced daily reports to supplement the on-site visual inspections they performed of the contractor’s work. However, there was no FEMA-produced documentary evidence showing that the COR used the metrics to assess contractor performance, such as whether the contractor set up the sites within 36 hours of awarding the contract. The COR told us that they included the contractor’s reports in the file as required, but they were not required to create any specific documentation to track contractor performance. The COR told us they did not retain copies of the informal checklists, and agreed that in this instance it would have been appropriate to create and maintain additional documentation to support their oversight.

· In the case of an approximately $118 million responder lodging contract that required the contractor to deliver, set up, operate, and demobilize temporary housing units for FEMA personnel responding to Hurricane Ian, FEMA officials were unable to produce documentary evidence to support their conclusion that the contractor met performance requirements. FEMA officials provided us with emails between the COR and the contractor on minor performance issues. FEMA officials said that the COR assigned to the contract saved all of the oversight documentation on their agency laptop and the documentation was not stored on a shared FEMA server. However, it is impossible to know whether that was the case because FEMA officials told us they removed all data from the COR’s laptop—in accordance with agency policy—after the COR left FEMA after the contract was awarded. FEMA officials told us they developed procedures to ensure CORs store contract oversight documentation on a shared FEMA server going forward to avoid repeating this situation.

· In a previously mentioned approximately $1 million cargo flights task order for the Maui wildfires response, FEMA failed to document its decision and rationale for not applying the monetary disincentives outlined in the base contract’s quality assurance surveillance plan against the contractor for flight delays. Specifically, an outbound flight from Maui on this task order departed 2 days after the period of performance ended. The COR told us that they decided not to recommend that the contracting officer apply the monetary disincentives listed in the base contract’s quality assurance surveillance plan because the cause of the delays was beyond the contractor’s control. For example, individuals responsible for loading the aircraft had access to one cargo loader rather than the two loaders they anticipated. In addition, FEMA officials said that their leadership gave priority to flights inbound to Maui over outbound ones, and the delayed flight was an outbound one. FEMA officials administering this contract added that this decision contributed to the flight delays, but agreed they should have documented their decision to not apply the monetary disincentives. FEMA also failed to issue a contract modification to adjust the task order’s period of performance to account for the flight delays.[39]

FEMA officials told us they plan to reiterate the responsibility, as outlined in the COR appointment letters and training, for CORs to document their oversight activities on future responder lodging contracts, which is one area where we identified the documentation gaps. This is an important step, but it is also important to ensure the CORs overseeing contracts for other goods and services are familiar with the importance of documentation. Without reiterating to CORs their role in documenting contractor performance during contract oversight activities, FEMA and other decisionmakers, such as Congress, may not know whether FEMA received the level and quality of services or goods that it purchased.

Some FEMA Oversight Staff Do Not Have Required Certification or Authorization

In eight of the 15 contracts we reviewed, we found that FEMA had personnel performing oversight functions without proper certification or contracting officer authorization. Staff performing contract oversight included CORs and technical monitors, as well as personnel with other titles such as security managers or manufactured housing specialists.

The DHS COR Guidebook and FEMA’s Acquisition Manual require technical monitors to have the same level of COR certification as the primary COR, a policy that has been in place since 2020. FEMA’s Acquisition Manual also requires contracting officers to issue an appointment letter authorizing technical monitors to serve on a contract. In each of the examples below, FEMA contracting and program office staff told us they were unaware of the technical monitor COR certification and contracting officer authorization requirements.

The oversight duties being performed by uncertified personnel included filling out quality assurance surveillance plans, conducting site inspections, and reviewing contractor-produced documentation. For example:

· In the previously mentioned nearly $51 million FEMA responder lodging contract for the Kentucky floods, the COR informed us that they requested a technical monitor to help manage the workload. FEMA officials told us that the technical monitor assisted the COR and routed responders’ complaints to the contractor to ensure they were addressed. While the COR told us they made the contracting officer aware of the assignment, the contracting officer did not issue an official technical monitor appointment letter as required by FEMA policy. In addition, the individual serving as technical monitor did not have an active COR certification as required by policy. FEMA officials administering this contract told us that they were unaware of the requirement for the technical monitor to receive an appointment letter and be certified at the same level as the COR.

· For a nearly $4 million technical support services contract for the Maui wildfires, FEMA used a technical monitor to assist the COR in performing oversight. This contract involved the preparation of a comprehensive, long-term recovery plan and a detailed implementation plan for the affected communities. The technical monitor on this contract received deliverables from the contractor, and the COR told us they relied on the technical monitor to send updates on the contractor’s performance. The deliverables included status reports of the contractor’s progress in developing the recovery and implementation plans. Officials subsequently informed us that this technical monitor did not have a COR certification and was not nominated and appointed according to agency policy. Officials told us that the COR was not aware that the technical monitor needed to be nominated. Without the technical monitor’s supervisor sending a nomination letter to the contracting office, the contracting officer did not know to issue the appointment letter, and thus the technical monitor was not appointed.

· FEMA awarded an approximately $2.5 million language services contract that involved the use of on-site and on-call interpreters to assist Maui wildfires survivors in applying for individual assistance. The interpreters were for languages commonly spoken in Hawaii, such as Ilocano, Hawaiian, and Japanese. On this contract, FEMA had an individual serving as a technical monitor who did not have a COR certification or contracting officer authorization in the contract file. The COR told us that they deployed to the disaster site for the first 3 months to set up the language services schedule and establish relationships with FEMA managers onsite. The technical monitor told us that they stayed onsite when the COR returned to the continental United States. FEMA officials said having the COR perform oversight remotely and leaving the technical monitor onsite was less costly. The technical monitor for this contract told us they worked with the COR to perform oversight, including duties such as reviewing sign-in sheets, invoices, and assignment trackers, and granting approval for interpreters to work extra hours. The COR and technical monitor told us they relied on this information when recommending whether the contracting officer should exercise the contract’s next option period. FEMA officials involved with the contract were not aware of the requirement for the technical monitor to have COR certification and contracting officer authorization.

FEMA officials told us they have not conducted technical monitor requirements training for their contracting and program office staff. According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, management should internally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives. Without training contract oversight staff (including contracting officers, CORs, and program office staff) on DHS and FEMA requirements for technical monitor certification and authorization, there is increased risk that FEMA has unauthorized or unqualified personnel performing contracting oversight on contracts and may not properly assess the goods and services received in accordance with the contract.

We also identified situations in which individuals with titles other than a COR or technical monitor, such as security managers and manufactured housing specialists, were performing contract oversight, which is not in accordance with FEMA policy. FEMA issued a memorandum in 2020 specifying that contract administration duties are limited to CORs and technical monitors and that these individuals must have the proper level of COR certification and be appointed by the contracting officer. We found that officials with other titles were performing contract oversight duties without certification or authorization.

Moreover, FEMA officials told us they do not have insight into how many staff may be working on active contracts without required contracting officer authorization or COR certification, even though they might be performing contract oversight tasks. We found that developing this insight is complicated by the fact that not all oversight officials are using the COR or technical monitor titles. According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives. Without understanding who in the agency is performing contract oversight and ensuring oversight is performed only by officials that have been appropriately certified and authorized, FEMA may have unqualified personnel performing contract oversight. For example:

· For two security contracts we reviewed, FEMA assigned security managers to assist the primary CORs in performing oversight duties, but not all of the managers had the required contracting officer authorization or COR certification.[40] The primary COR for one contract told us that the other security managers are not required to be certified CORs. However, like technical monitors, security managers supported the COR in contract monitoring and oversight. For example, security managers—other than the primary COR and alternate COR—would travel to sites where contracted armed guards were assigned to collect guard sign-in sheets and activity reports and to perform site inspections. FEMA provided examples of security managers correcting contractor performance, such as directing security guards to use the required firearm holster or wear the correct uniform. A senior FEMA contracting official we spoke with—who oversees the management of armed security guard contracts—acknowledged that some individuals in the security cadre feel they have the right to give the contractor technical direction or performance feedback even though they are not officially authorized to do so.

· For the previously mentioned $89 million temporary housing contract in response to the Kentucky floods, FEMA used manufactured housing specialists to perform site inspections and fill out maintenance and deactivation quality assurance surveillance plan forms. Only 25 of the 35 specialists were COR-certified. FEMA officials subsequently told us that while they initially believed that manufactured housing specialists were not required to be COR-certified, they recognize now—in part due to our review—that the specialists perform duties similar to that of a COR and they were out of compliance with DHS and FEMA policies. Going forward, according to the program office, these specialists will be required to have a COR certification and undergo the necessary training.

FEMA Identified and Monitored Required Training and Staffing Needs but Shortcomings Remain in Adhering to Staffing Model Key Principles

FEMA tracks contracting officers’ and CORs’ required trainings and corresponding certifications and notifies CORs when their certifications expire. Additionally, FEMA officials said they attempt to ensure that each of the active contracts only have certified CORs assigned to them. FEMA also uses a DHS staffing model to predict potential contracting officer needs through an annual agency-wide staffing exercise. The staffing model, however, does not fully adhere to key principles for staffing models that we identified in prior work. According to DHS, components such as FEMA could use the staffing model’s outputs as a resource to justify budget needs or to advocate for additional resources to stakeholders, such as agency leadership. The number of FEMA contracting officers has remained both below the annual staffing model outputs and authorized levels for the past two fiscal years.

FEMA Identified and Monitored Required Contract Oversight Training and Staff’s Certification Status

According to agency policies, contracting officials must complete the FAC-C (Professional) or FAC-COR training, depending on their position.[41] These courses provide an overview of contracting officer and COR oversight duties, among other responsibilities. The certifications provide government-wide standards for education, training, and experience for core competencies among several contracting disciplines—creating consistent competencies among individuals performing contracting work.[42]

FEMA tracks FAC-C (Professional) and FAC-COR certifications for contracting officials via Federal Acquisition Institute Cornerstone OnDemand—a training enrollment and acquisition workforce management system. In January 2023, the Office of Federal Procurement Policy updated FAC-C (Professional) requirements and now contracting officers must earn 100 hours of continuous learning within a 2-year period to maintain their certification.[43] Table 1 summarizes the certification status of the FEMA contracting job series, such as contracting officers, contract specialists, and procurement analysts, among others.

|

FAC-C (Professional) certification status |

Totals |

|

Certified contracting officers |

186 |

|

Officials within 36-month certification grace perioda |

12 |

|

Total number of individuals in contracting job series |

198 |

FAC-C (Professional): Federal Acquisition Certification in Contracting; FEMA: Federal Emergency Management Agency

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Acquisition Institute Cornerstone OnDemand data. | GAO‑25‑107136

aAccording to FEMA officials, they consider

these individuals as contract specialists until they meet FAC-C (Professional)

requirements. As such, these individuals do not have warrants or serve in a

contracting officer role.

FEMA had over 2,000 individuals formally certified as CORs as of August 2024, with varying levels of FAC-COR certification. According to DHS policy, the agency limits the type of contracts CORs are qualified to oversee based on their level of certification. Generally speaking, a COR Level II certification allows qualified individuals to oversee lower risk contracts, such as firm-fixed-price contracts, whereas a COR Level III certification allows qualified individuals to oversee higher risk contracts, such as time-and-materials contracts.[44]

Out of FEMA’s total CORs, over 370 had expired certifications as of August 2024. FEMA took steps to notify CORs of their expiring certifications and officials said they took steps to ensure affected individuals did not serve on active contracts. For example, FEMA has an intranet page dedicated to FAC-COR recertification, sent email reminders to individuals who needed recertification, and held multiple information sessions on the renewal process in 2023 and 2024. FEMA told us the reason that these individuals had expired certifications was because employees had not completed their continuous training requirements prior to May 2024, which is the start of a new 2-year continuous learning period.[45] FEMA officials said they provided a list of these individuals to DHS for the Federal Acquisition Institute—the agency responsible for fostering and promoting the development of a federal acquisition workforce—and recommended revoking their COR certifications. Officials said once the certifications are revoked, they will begin to share requirements with the CORs about how to get recertified. Officials also said they complete regular reviews of FEMA’s active contracts to ensure that only certified CORs serve on them.[46] According to FEMA officials, one-third of the certified CORs serve on active contracts, and they feel that the agency has the appropriate number of CORs. Table 2 summarizes the number of FEMA CORs by certification level.

|

FAC-COR certification level |

Total with current FAC-COR certification |

Total with expired FAC-COR certification |

Total |

|

Level II certificationa |

1,137 |

290 |

1,427 |

|

Level III certificationb |

962 |

88 |

1,050 |

|

Total number of CORsc |

2,099 |

378 |

2,477 |

FAC-COR: Federal Acquisition Certification in Contracting for Contracting Officer’s Representatives; FEMA: Federal Emergency Management Agency

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Acquisition Institute Cornerstone OnDemand data. | GAO‑25‑107136

aFAC-COR Level II certifications are for “other than high risk or major investment” contracts, such as firm-fixed-price contracts.

bFAC-COR Level III certifications are for “high risk or major investment contracts,” such as time-and-materials contracts.

cDue to the size and complexity of DHS’s portfolio, the department does not issue Level I certifications. Officials said some CORs may come to FEMA with FAC-COR Level I certification, but they do not issue certifications at this level. As a result, the total number of CORs here does not include CORs with Level I certifications.

We found that the FAC-C (Professional) and FAC-COR training materials and documents generally discussed oversight duties outlined in agency guidance, such as monitoring contractor performance. CORs for nine of the 15 selected contracts in our sample said the required training provided a high-level overview of their required oversight duties. Officials for 10 of the 15 selected contracts also suggested that on-the-job training is essential or necessary to become effective in their position.[47] For example, FEMA officials for one selected contract said no COR training class can prepare someone to be successful on the first day and field experience, on-the-job training, and mentorship are more important.

DHS and FEMA also offer additional contract oversight training classes and resources for contracting officials. For example, in 2023, FEMA provided additional training on contractor performance ratings and general best practices for oversight as part of the agency’s community of practice engagement sessions. Several FEMA officials we spoke with also described receiving or providing additional branch and mission specific training.

FEMA Uses DHS’s Staffing Model but the Model Does Not Fully Adhere to Key Principles

DHS’s Office of the Chief Procurement Officer (OCPO) developed a model to better understand contracting staffing needs and to create a transparent process for supporting budget or additional resource requests. The staffing model is specific to the contracting job series that includes contracting officers.[48] Each DHS component, including FEMA, could contribute to its unique iteration of the standardized model and may use its outputs to help manage staff needs within the contracting job series.[49] DHS OCPO and the components make changes to fixed data in the model, such as the hours required to complete new contract awards, modifications, and additional tasks, to keep the information in the model current during triennial updates. DHS requires components to use the model during its annual staffing exercise, which is an exercise that allows the heads of contracting activity to verify and update the previous year’s historical data to project the next fiscal year workload and staffing requirement.[50] According to DHS, the staffing model’s output can provide officials with the data they need to justify current staffing resource levels to their leadership or to support future staffing requirements.

We previously identified key principles for staffing models, and reported that models that reflect those principles can enable agency officials to make informed decisions on workforce planning.[51] We compared DHS OCPO’s staffing model with five of the key principles we previously identified and found that DHS met two, partially met two, and did not meet one (see table 3 below).[52]

Table 3: GAO Assessment of the DHS Office of the Chief Procurement Officer’s (OCPO) Staffing Model Against Selected Key Principles

|

Staffing model key principle |

GAO assessment (Met, partially met, or not met) |

|

Incorporate work activities, frequency, and time required to conduct them Incorporate mission, tasks, and time it takes to conduct activities, incorporate elements mandated by law or key goals into model design |

Met |

|

Involve key stakeholders Ensure staffing model involves key internal stakeholders for their input and establishes roles and responsibilities for maintaining the model |

Met |

|

Ensure data quality Ensure that the staffing model’s assumptions reflect

operating conditions; ensure the credibility of data |

Partially met |

|

Inform budget and workforce planning Use staffing model to inform budget planning,

prioritization activities, and workforce planning (e.g., |

Partially met |

|

Incorporate risk factors Incorporate risk factors, including attrition, and address risks if financial or other constraints do not allow full implementation of the staffing model |

Not met |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) information. | GAO‑25‑107136

Note: Based on agency documents and interviews with DHS officials, GAO defined “met” as DHS incorporated the principle into the OCPO staffing model; “partially met” as DHS incorporated some aspects of the principle into the OCPO staffing model; and “not met” as DHS did not incorporate the principle into the OCPO staffing model. In total, there are six key principles for staffing models that GAO identified in prior work. GAO did not select one key principle related to ensuring the correct number of staff needed and appropriate mix of skills. This principle states that officials use the staffing model to determine the number of staff needed and the appropriate mix of skills needed to accomplish the agency mission. Through its analysis and discussions with DHS officials, GAO determined that this model is specific to the roles and responsibilities of contracting officers and it would not be reasonable for this model to include other positions. As a result, GAO determined this key principle was not applicable to its assessment.

The following sections detail our assessment of DHS’s staffing model against the key principles.

Incorporate work activities, frequency, and time required to conduct them (Met). DHS OCPO’s staffing model provides a breakdown of contracting and additional tasks by the time it takes to complete them or the frequency with which they occur. For example, the model provides a breakdown of the hours required to complete each action per contract type, and values for classified and unclassified actions.[53] This information helps forecast the total contracting labor hours projected for the following fiscal year. The model uses total forecasted labor hours, time available per year, and ratio of nonsupervisory to supervisory employees to calculate the total number of staff needed for the following fiscal year.

The model also factors the time and frequency to complete additional tasks into its staffing estimates, such as completing contractor performance assessment reports, training, and customer meetings. For example, FEMA’s fiscal year 2024 completed model estimated that for every hour spent on awarding contract actions, each contracting officer would spend another 59 minutes on tasks and responsibilities outside of those required to award a contract action.

Involve key stakeholders (Met). DHS involves key stakeholders, such as different offices within OCPO as well as DHS components, as it updates its model and conducts its annual staffing exercise. While DHS owns the model, its components own the projections resulting from the annual exercise. Different offices within OCPO and DHS components (i.e., key internal stakeholders) have defined roles and responsibilities during the triennial and annual updates. Some roles and responsibilities within OCPO during these updates include:

· performing detailed reviews of data sent by components’ heads of contracting activity, and

· determining the standardized hour assumptions in the staffing model.

Some components’ heads of contracting activity roles and responsibilities during these updates include:

· verifying the model data from the previous fiscal year, and

· updating certain data fields within the model to provide a more precise staffing projection for the upcoming fiscal year.

Ensure data quality (Partially met). DHS uses credible data sources and has taken steps to ensure that the staffing model’s assumptions reflect operating conditions. The staffing model incorporates data from the National Finance Center, the Federal Procurement Data System, and Operational Status Reports.[54] We consider these sources as generally authoritative and widely used across the federal government. To reflect current operating conditions, DHS solicits and incorporates component data or input during annual and triennial updates.

· As part of DHS’s annual staffing exercise, component representatives verify model data from the previous fiscal year and update certain fields to create more precise staffing projections. Component representatives are expected to document any changes or updates they make to the model. Components run the current model to project staffing needs for the upcoming fiscal year during this process.

· During the triennial update, DHS updates certain data that remain constant during the annual staffing exercise, such as hours required to complete contracting actions, within the model to help ensure the model’s yearly estimates are accurate. Specifically, components provide data to inform the underlying assumptions of the model, such as hours per action. DHS completed its most recent triennial update in 2022.[55] This update included revisions to include new awards, modifications, and additional tasks data points within the model, among others. Overall, the 2022 update found that nonsupervisory employees had less time available for contracting activities.[56]

However, DHS has not documented all aspects of its staffing model, and officials said doing so is an ongoing process. For example, DHS documented some changes as a result of its 2022 triennial update and the instructions within the model that components follow during the annual staffing exercise. However, DHS has not documented—outside of the model—the steps used to create and maintain the model. DHS officials said this is an ongoing process and did not identify time frames for documenting all aspects of its staffing model. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should clearly document internal control and all transactions and significant events in a manner that allows the documentation to be readily available for examination.[57] Without documenting the steps it used to create and maintain the model, DHS risks losing institutional knowledge to preserve the staffing model’s integrity.

Inform budget and workforce planning (Partially met). DHS officials said four components—including FEMA—used their staffing model to inform workforce planning, but they are not aware of the extent to which components use it for long-term workforce planning or budgetary purposes. According to a DHS memorandum, the intent of accredited staffing models is to create a credible and consistent method for justifying component human capital needs. DHS components could use the OCPO model to justify current or additional staffing resources for contracting officers, track staffing levels, or better understand staffing needs. For example, DHS officials said the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency used the model to support staffing needs when setting up its contracting office.[58]

DHS officials said they are not aware of whether components use the model’s outputs to inform long-term workforce planning. Officials noted that their staffing model is one management tool that can help components assess risks and prioritize resources. The staffing model helps tell the story of why DHS or its components need a certain number of staff, according to DHS officials. Those officials said that determining staffing needs through the model is a good practice, but the ultimate decision comes down to how many contracting staff the department or a component can afford. As a result, DHS does not require its components to meet the staffing model outputs.

DHS officials said all components have a hard time keeping contracting officers onboard and there are a limited number of qualified candidates available. This is supported by FEMA’s current gap between the staffing model outputs and the actual number of contracting job series staff. FEMA’s onboard staff for the contracting job series have remained both below the annual staffing model outputs and authorized levels for the past 2 fiscal years. FEMA’s annual staffing exercise projected that the agency would need 244 employees within the contracting job series for fiscal year 2024—which includes contracting officers. Comparatively, FEMA’s authorized staffing levels for the same fiscal year equated to 215 employees. As shown in table 4, FEMA had 198 individuals under the contracting job series onboard as of August 2024—resulting in a 17-person shortfall from authorized levels and a 46-person shortfall from what the staffing model said FEMA needed. Table 4 also shows FEMA’s staffing model projections, authorized staffing level, total contracting job series onboard, and the difference between the model’s projected output and total contracting job series staff onboard for fiscal years 2023 and 2024.[59]

Table 4: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Staffing Model Projections vs. Onboard Contracting Job Series Staff, Fiscal Years 2023-2024

|

Fiscal year |

Staffing model projection |

Authorized staffing level |

Total contracting job series staff onboarda |

Difference between projected output and total staff onboard |

Difference between authorized and onboard staff |

|

2023 |

215 |

213 |

198 |

17 |

15 |

|

2024 |

244 |

215 |

198 |

46 |

17 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) information. | GAO‑25‑107136

aThe fiscal year 2023 information in this

column is based on data for the entire corresponding fiscal year. The fiscal

year 2024 information is based on data as of August 2024.

FEMA officials said they hire outside support to help with oversight, and competing interests affect the agency’s ability to hit staffing numbers. FEMA officials said the agency contracted for approximately 30 staff to perform duties within the contracting job series to help execute and oversee disaster contracts.[60] According to FEMA officials, they do not account for these contractors in the staffing model’s projections. They said competing budget constraints and interests, such as balancing supervisory and nonsupervisory positions, impact their ability to hit the authorized staffing numbers, which they suggested will continue to be a challenge. Additionally, FEMA officials said the increase in projected staffing needs between fiscal years 2023 and 2024 was due to the staffing model’s inclusion of classified contracting actions.[61]

FEMA officials said the staffing model is one tool they use to justify or manage staffing levels. For example, FEMA officials said they used the staffing model information in FEMA’s Office of the Chief Component Procurement Officer’s November 2023 Resource Allocation Plan, which showed the agency had a deficit of 25 personnel. Further, FEMA’s Office of the Chief Component Procurement Officer workforce analysis from fiscal years 2022 and 2024 shows historical data staffing model results against onboard staff. According to FEMA officials, budget constraints prevented the agency from hiring additional personnel. FEMA officials also said they will continue to use the staffing model for future workforce analysis and staffing requests.