FRAUD IN FEDERAL PROGRAMS

FinCEN Should Take Steps to Improve the Ability of Inspectors General to Determine Beneficial Owners of Companies

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

|

Revised June 9, 2025 to correct pages 10 and 55-57 (Background and Appendix III). The corrected Background section should read: “For the OIGs with law enforcement authority…” The corrected Appendix III, Table 2 under column “OIG has law enforcement authority (yes/no)” should read: “Architect of the Capitol – Yes; Government Publishing Office – Yes; Library of Congress – Yes.” Table 2 source line should also include: “Legislative Branch Inspectors General Independence Act of 2019.” Added Table 2 note should read: “GAO’s OIG, while overseeing a federal agency, was excluded to maintain independence." |

Why GAO Did This Study

Fraud across federal programs is a significant and persistent problem. Some of this fraud is perpetrated by private companies obscuring beneficial ownership information when they compete for government contracts or apply for federal benefits. OIGs conduct oversight through audits and investigations, which include issues related to beneficial ownership.

GAO was asked to review how beneficial ownership information may aid OIGs in their fraud detection and response efforts. This report describes the types of federal program fraud associated with beneficial ownership information, provides OIGs’ perspectives on using the company registry, and assesses FinCEN’s actions to communicate with OIGs.

GAO reviewed relevant laws and agency documentation, interviewed officials from FinCEN and the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency (CIGIE), conducted a roundtable discussion with seven OIGs, and surveyed 72 OIGs to obtain their views on how the registry could affect their efforts to combat fraud.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that FinCEN communicate with OIGs, via CIGIE, regarding OIGs’ company registry access and use. FinCEN had no comment on the recommendation.

What GAO Found

When information is unclear about the identity of the person who ultimately owns or controls a company that is participating in federal programs or operations, there is a heightened risk of procurement-, grant-, and eligibility- related fraud. Offices of Inspectors General (OIG) told GAO that they face challenges using the currently available federal, state, and commercial data sources to identify the “beneficial owners” of companies as part of their fraud detection and response efforts.

A law that took effect in January 2024 directed certain companies to report their beneficial ownership information to a company registry administered by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). FinCEN has begun rolling out a process to allow law enforcement agencies, including select OIGs, to request access. Some OIGs told GAO that they have received information about the company registry, but they were unclear on which OIGs would have access to the data and exactly how company registry data can be used. Nevertheless, most OIGs who responded to GAO’s survey reported that access to company registry data could be useful to their offices’ fraud detection and response efforts (see fig.).

OIGs identified several potential limitations in using company registry data. For example, FinCEN has not yet specified capabilities for bulk downloads of the data, but OIGs noted that such capability could facilitate data matching between the company registry and other data sources. In March 2025, Treasury announced plans to narrow the scope of reporting to foreign companies only. Beneficial ownership risk remains, however. With this change, registry information available to OIGs is more limited. Communicating with OIGs could help clarify the information available, OIGs’ access, and how the data can be used. FinCEN officials said they are open to discussions with OIGs on these issues. Communication with OIGs during the registry rollout would better position FinCEN to identify and address challenges related to the fraud detection and response needs of the OIG community. Further, these efforts support FinCEN’s strategic goal to significantly improve the ability to mitigate illicit finance risk by increasing law enforcement and other authorized users’ access to beneficial ownership information.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

BSA |

Bank Secrecy Act |

|

CIGIE |

Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency |

|

Company Registry |

Beneficial Ownership Secure System |

|

CTA |

Corporate Transparency Act |

|

DOD |

U.S. Department of Defense |

|

FAA |

Federal Aviation Administration |

|

FinCEN |

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network |

|

FMCSA |

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration |

|

Fraud Risk Framework |

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

MOU |

memorandum of understanding |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

PACE |

Pandemic Analytics Center of Excellence |

|

PRAC |

Pandemic Response Accountability Committee |

|

SAM |

System for Award Management |

|

SBA |

Small Business Administration |

|

Treasury |

U.S. Department of the Treasury |

|

USAID |

U.S. Agency for International Development |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 8, 2025

The Honorable Charles E. Grassley

Chairman

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse

Co-Chair

Caucus on International Narcotics Control

United States Senate

Fraud in federal programs is a significant and persistent problem.[1] Some of this fraud is perpetrated by private companies obscuring information on “beneficial ownership”—the person who ultimately benefits from ownership or control of the company—when they compete for government contracts or apply for federal benefits. Our prior work has highlighted examples where private companies obscured beneficial ownership information to fraudulently obtain access to the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Paycheck Protection Program, register aircraft with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and obtain contracts with the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD).[2]

Offices of Inspectors General (OIG) have a unique mission in detecting and responding to such wrongdoing in federal programs. They conduct oversight through audits and investigations, which include issues related to beneficial ownership. For example, a recent National Health Care Fraud Enforcement Action, investigated by the Department of Health and Human Services’ OIG and other law enforcement agencies, has alleged that individuals laundered nearly $5.3 million received from false and fraudulent Medicare and Medicaid claims by transferring the funds to shell companies, which obscured beneficial ownership.[3]

The Corporate Transparency Act (CTA), which went into effect on January 1, 2024, includes significant reforms to anti-money-laundering laws and is intended to help prevent and combat money laundering, terrorist financing, corruption, and tax fraud.[4] One component of the CTA requires select types of companies (reporting companies) to disclose identifying information about their beneficial owners to the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN).[5] FinCEN has established the Beneficial Ownership Secure System (company registry) to collect this information.

The CTA also tasks FinCEN with securely storing this information. The CTA further specifies that company registry information may only be disclosed to support national security, intelligence, and law enforcement activities or compliance with financial institution customer due diligence regulations. FinCEN has begun the planning and early execution phases of rolling out access to information in the company registry.[6]

You asked us to examine how beneficial ownership information may aid OIGs in their investigation of fraud, corruption, financial misconduct, and other risks associated with opaque beneficial ownership information in federal programs and operations. This report (1) describes federal program fraud risks associated with opaque beneficial ownership information and related challenges OIGs face with fraud detection and response, (2) describes OIGs’ perspectives on using the company registry, and (3) assesses FinCEN’s actions to communicate with OIGs about company registry data.

To describe federal program fraud risks associated with opaque beneficial ownership information and related challenges OIGs face with fraud detection and response, we reviewed relevant GAO reports, OIG semiannual reports, and risk assessments from Treasury for illustrative examples of the types of fraud risks and closed cases featuring fraud schemes associated with opaque beneficial ownership information. We also held a roundtable discussion with seven selected OIGs to learn about their views on the challenges involved in identifying beneficial owners within their fraud detection and response efforts.[7] In addition, we interviewed members of the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency (CIGIE) on the federal program fraud risks associated with opaque beneficial ownership and the related challenges OIGs face with federal program fraud detection and response efforts.[8]

To describe OIGs’ perspectives on the use of FinCEN’s company registry, we first surveyed 72 federal OIGs for their views on the utility of company registry data in their fraud detection and response efforts.[9] We then held a roundtable discussion with selected OIGs to obtain their views on opaque beneficial ownership information and the company registry. Roundtable participants identified and voted on the top potential limitations they could face in using information from the company registry in support of their fraud detection and response efforts. We interviewed members of CIGIE to obtain their views on how information from the company registry could impact OIGs’ fraud detection and response efforts. We also interviewed FinCEN officials for their perspectives on OIGs’ reported potential limitations in using company registry data. See appendix I for a full discussion of our scope and methodology, including our survey and roundtable discussion. Complete results of our survey are presented in appendix II.

To assess FinCEN’s actions to communicate with OIGs about company registry data, we (1) reviewed relevant FinCEN documentation on the implementation, time frames, and educational outreach efforts regarding access to the company registry; (2) reviewed Treasury’s Fiscal Year 2022-2026 Strategic Plan for information on the agency’s efforts to aid law enforcement agencies in the detection of illicit financial activity; (3) interviewed FinCEN and CIGIE officials on efforts to communicate with OIGs during the phased rollout to provide access to the company registry; and (4) analyzed OIGs’ survey and roundtable participant responses.[10] We then analyzed the extent to which these documents and actions aligned with the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government - specifically, the principle related to management externally communicating the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[11]

To provide context for the scope of potential OIG oversight, we analyzed USAspending.gov data, supplemented by the General Services Administration’s (GSA) System for Award Management (SAM) data to determine the number of companies participating in federal programs. We considered awards active in USAspending.gov for calendar year 2023 and the entities that held those awards.[12] We also analyzed data from OpenCorporates, a third-party data aggregator of secretary of state records, to supplement our analysis with the number of companies registered to do business in the U.S.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of Beneficial Ownership Information and Company Formation

A “beneficial owner” is the person who ultimately benefits, financially or otherwise, from ownership or control of a company. The CTA defines a beneficial owner as any individual who exercises substantial control or controls at least 25 percent ownership interest of a company (thus there may be up to four beneficial owners of a company).[13] However, the identity of the beneficial owner(s) is not always required when forming or registering a business.

Many companies are formed by registering with secretaries of state or similar state offices. However, most jurisdictions do not require identification of owners when forming a new business or registering an existing business. The amount of company information collected by states and available to the public, including information on owners of record or beneficial owners, varies by state. Further, the vast majority of states require little to no disclosure of contact information or other information about an entity’s officers or others who control the entity. Therefore, opaque information can make it challenging to identify beneficial owners for law enforcement efforts, financial institutions’ customer due diligence compliance efforts, or other purposes.

Further, the structure of certain company types, such as limited liability companies, can obscure information on beneficial owners. Opaque ownership structures may be created and used for legitimate purposes. For example, shell companies—companies that exist only on paper—may be used to transfer assets or facilitate corporate mergers. However, these structures may also be used to facilitate money laundering and other criminal activities by concealing the identities of bad actors. Multiple layers of corporate structures—companies owned by other companies, including shell or shelf companies—can further obscure information on beneficial owners and their relationships to other companies or individuals.[14] With this information and such relationships hidden, bad actors may target federal programs—and by extension, taxpayer dollars—to improperly receive federal contracts or fraudulently access federal benefits.

Our analysis of aggregated secretary of state data showed that as of January 2024, as many as 50.9 million active businesses operated in the U.S., including D.C. and Puerto Rico.[15]

Beneficial Ownership Reporting Requirements and Law Enforcement Access

Beneficial ownership reporting and data availability requirements have evolved, along with understanding of how this information can help fight criminal activity. The landmark anti-money-laundering legislation, the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) of 1970, has been amended over the years. In 2016, the regulations implementing the BSA were updated with a requirement for financial institutions to collect and verify beneficial ownership information when opening new accounts for certain company types.[16] With enactment of the CTA in 2021, certain company types are required to report beneficial ownership information directly to FinCEN.[17] FinCEN must collect the reported data and securely store the data in the company registry, as required by the CTA.

We have previously reported that FinCEN is responsible for BSA administration, has authority to enforce compliance with BSA requirements, and serves as the repository of BSA reporting from banks and other financial institutions.[18] FinCEN also analyzes information in BSA reports and shares its analyses with appropriate federal, state, local, and foreign law enforcement agencies. Federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies can use BSA reports to help investigate and prosecute fraud, drug trafficking, terrorist acts, and other criminal activities. According to Treasury’s Fiscal Year 2022 – 2026 Strategic Plan, FinCEN also aims to increase transparency in the domestic and international financial system to aid law enforcement agencies in the detection of illicit financial activity.[19]

As of January 2024, entities created by filing a document with a secretary of state (or similar office) are required to report beneficial ownership information to the company registry.[20] We identified approximately 47 million companies registered in the U.S. that are likely to report their beneficial ownership information to the company registry.[21] These companies must submit the beneficial owner(s)’ name, date of birth, and address, as well as a unique identifying number from an acceptable identification document (such as a current passport or driver’s license) and the name of the state or jurisdiction that issued the identification document.

FinCEN’s final rule on Beneficial Ownership Information Access and Safeguards, published December 22, 2023, limits disclosure of beneficial ownership information to federal agencies and other law enforcement agencies for use in furtherance of national security, intelligence, or law enforcement.[22] Law enforcement agencies, including OIGs, can use beneficial ownership information, along with related data collected under the BSA, as amended, to combat illicit financial activities by pursuing criminal or civil investigations. Investigations of government procurement matters are among authorized uses of these data.

FinCEN plans to use a phased rollout approach to provide company registry access to authorized users, including OIGs, in five phases. These phases began in spring 2024 and had been planned to be completed by spring 2025. Once each rollout phase is complete with required documents received from interested agencies and institutions, authorized users may access the company registry through the FinCEN beneficial ownership portal. Access rules for beneficial ownership information differ from other FinCEN data.[23]

The CTA has been the subject of ongoing litigation and changes in implementation. There have been multiple challenges to the law that are ongoing at the time of this report’s issuance. Additionally, in March 2025, Treasury announced its plans to narrow the scope of the rule implementing the CTA to foreign-owned reporting companies only.[24] According to Treasury, it is taking this step to ensure that the rule is appropriately tailored to advance the public interest. Treasury announced that, with respect to the CTA, it will not enforce any penalties or fines associated with the beneficial ownership information reporting rule under the existing regulatory deadlines. It also will not further enforce any penalties or fines against U.S. citizens or domestic reporting companies or their beneficial owners after the rule changes take effect. Such implementation changes limit the availability of beneficial ownership information. As a result of the ongoing litigation and implementation changes, the rollout of the company registry is being affected, with the full impacts not known at the time of this report’s issuance.

Roles and Authorities of Offices of Inspectors General

OIGs play an important role in federal program fraud detection and response. There are more than 70 federal OIGs. OIGs can use data analytics or other techniques to proactively detect fraud. OIGs also conduct investigations into potential fraud and may use the results of those investigations to raise fraud awareness and conduct trainings for federal program managers and others involved in program delivery. GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework) calls for program managers to collaborate and communicate with OIGs to improve understanding of fraud risk and align efforts to address fraud.[25]

The Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, outlines responsibilities and authorities for Inspectors General. For example:

· OIGs conduct investigations of their agencies’ programs and operations, including cases of fraud related to ownership misrepresentations. OIGs are also required to report suspected violations of federal criminal law identified while carrying out their duties and responsibilities.[26]

· For the OIGs with law enforcement authority, the Inspectors General and select individuals under their supervision are authorized to perform law enforcement-specific activities including carrying a firearm, seeking and executing warrants for arrest, and making an arrest.[27] See appendix III for a list of OIGs, including OIGs with law enforcement authority.

OIGs are uniquely positioned to investigate violations of law that impact federal agencies. OIGs conduct investigations in relation to the federal programs their offices oversee and are subject matter experts in federal programs. As such, they understand their agencies’ program requirements and how the programs can be defrauded. In addition, OIGs help to promote efficiency within federal programs while saving taxpayer dollars. OIGs do this through audits and investigations which may result in criminal actions or civil settlements, but may also be resolved through administrative actions, such as recoveries, recommendations for government-wide suspensions, or termination of awards to further help create an environment of accountability within programs they oversee.

OIGs may provide training to agency staff and share results of investigations to raise fraud awareness and reinforce requirements to report suspected fraud to the OIG. According to the Fraud Risk Framework, increasing managers’ and employees’ awareness of potential fraud schemes through training and education can serve a preventive purpose by helping to create a culture of integrity and compliance within the program. OIG response efforts can also inform agencies’ fraud prevention activities, such as by using the results of investigations to enhance applicant screenings and fraud indicators.

OIGs conduct investigations into potential fraud in their programs, including programs that award federal funds to companies. Our analysis of USAspending.gov data identified over 168,000 unique companies with active federal contracts or financial assistance in 2023, totaling nearly $6.2 trillion. We determined that over 116,000 of these had a company type that would likely be required to report beneficial ownership information to the company registry.

CIGIE was established in 2008 to represent and serve as the coordinating body for the OIG community. According to its strategic plan, CIGIE seeks to advance the OIGs’ collective interests through effective and consistent communication with their stakeholders.[28] For example, one of CIGIE’s goals is to facilitate collaboration and sharing of best practices to increase efficiency and effectiveness; educate stakeholders on CIGIE’s mission and activities; and gather information about their stakeholder’s needs, priorities, and challenges.

Opaque Ownership Information Heightens Program Fraud Risks and Hinders OIG Detection and Response

Federal programs face heightened fraud risks when beneficial ownership information is opaque for private companies that compete for government contracts or apply for grants or benefits. In addition to financial losses, impact from such fraud can be nonfinancial, such as threats to national security or public safety. OIGs face challenges in identifying beneficial owner information when using multiple data sources and analytic tools as part of their fraud detection and response efforts.

Opaque Ownership in Procurement, Grants, and Eligibility Decisions Heighten Program Fraud Risks

Opaque beneficial ownership information heightens the risk of procurement-, grant-, and eligibility-related fraud by hiding improper relationships; illicit access to sensitive government information by foreign actors; or ineligible status, among other wrongdoing.

Procurement Fraud Risks

By hiding improper relationships or illicit activity—such as conflicts of interest, corrupt activity, or unauthorized access—opaque beneficial ownership information heightens the risk for procurement fraud. The changeable nature of contractor relationships further complicates this risk. According to CIGIE members we interviewed, contractors buy each other out, merge, or create joint ventures. Even with available contractor relationship information, officials told us that these practices can make understanding and reconstructing the underlying relationships difficult or impossible.

Beyond hidden relationships between contractors, opaque ownership information facilitated through the use of shell companies can hide conflicts of interest and other illicit activity. For example, an OIG investigation discovered a contract conspiracy involving multiple foreign service national employees of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Southern Africa, according to an OIG semiannual report.[29] In this scheme, a USAID Southern Africa program manager registered a shell company that was awarded 10 contracts over 4 years, with a total value of $150,663. Two additional foreign national employees fabricated invoices, reports, and other documentation in support of the scheme. The three employees confessed to also taking kickbacks on contracts awarded to the shell company and admitted that little-to-no goods were provided to USAID Southern Africa under these contracts.

Opaque ownership information can also be exploited to obscure corrupt federal officials’ relationships to companies receiving federal contracts. CIGIE members we interviewed described investigations of federal employees with contracting authority who also had a beneficial ownership interest in a company receiving federal funds. We reported on a similar type of case in 2019, involving an employee of a DOD contractor.[30] In this case, the employee and his wife formed a company, but listed the names of family members as the managers on company formation documents to conceal their ownership. In his official position within the DOD contracted entity, he wrote letters justifying awards of purchase orders to his own company, and approved recommendations that awards be made to his company. The company received at least $9.7 million. The employee’s wife and co-owner of the company signed the subcontracts using her maiden name, knowing that the use of her married name could reveal the employee’s involvement in the company and affect the awards.

Fraud risks in procurement can also manifest when foreign actors hide behind opaque ownership information to gain unauthorized access, such as to sensitive military data. For example, in November 2019, we reported on a case where a foreign manufacturer created a shell company in the United States for the purpose of contracting with the government and obtaining DOD contracts that foreign-based manufacturers were not permitted to receive.[31] The shell company received payments from DOD from June 2011 to September 2013. The contractor’s owner was a foreign citizen and the president of a foreign manufacturing company, despite claiming to be a domestic company. Contract payments were wired to a foreign bank account, most of which were then transferred to the bank account of the foreign manufacturing company. The contractor’s owner used an alias to receive access to military critical technical data that he was not eligible to access as a foreign citizen.

Grant Fraud Risks

Opaque beneficial ownership information heightens the risk for grant fraud by obscuring relationships between entities. Members of CIGIE told us that an OIG that oversees federal grants was concerned with subgrantees because not knowing who the subgrantees are leads to concerns about related parties and bid-rigging. We’ve previously reported on how opaque ownership structures can play a role in carrying out these types of fraud schemes.[32]

Roundtable participants also highlighted how investigating cases of grant fraud in grant award systems becomes challenging when there is opaque beneficial ownership information. For example, one participant shared concerns that nonprofit organizations change their names and acquire each other, making it challenging to figure out who remains the owner when one nonprofit is absorbed by another. Sometimes nonprofit organizations do not update their registrations in the Internal Revenue Service’s 501(c)(3) database, according to the roundtable participant, which makes it a challenge to research organizations.[33]

Another roundtable participant shared an example from one of their grant programs where a nonprofit organization received an overpayment in its grant award due to a lack of true beneficial ownership information. For example, organizations must disclose their affiliates to be eligible for certain grant programs to ensure that awards are appropriately calculated, according to the participant. Organizations are eligible for a certain amount of award based on the disclosed affiliates across all locations and, without true beneficial ownership information, a grantee could receive a larger award than it is eligible for. One awardee received 3 to 5 times more of the grant funds than it should have received because of the lack of true beneficial ownership information, according to the participant.

Obscuring relationships between businesses can lead to entities receiving grants for duplicative work. For example, in 2024, we reported on a case where an individual and three businesses applied for and received over $1 million in Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer contracts and grants for essentially equivalent work from three different federal agencies on behalf of four related businesses.[34] The individual and businesses involved concealed from each participating agency the existence of the other agencies’ awards and the relationships between the businesses. In proposals for each award, the individual and businesses represented that each business had distinct facilities, equipment, and operations. In reality, the businesses shared a common facility and resources. The individual and businesses further misrepresented in each proposal, among other things, costs, employees, and the eligibility of their principal investigators to perform work under the awards.

Eligibility Fraud Risks

Opaque beneficial ownership information can make eligibility determinations for federal benefits difficult, heightening fraud risk where information associated with an ineligible company or status is deliberately obscured. Participants in our OIG roundtable described the checks in some of the benefits programs they oversee. For example, one participant OIG oversaw an agency providing direct benefits and described the checks that program officials conduct on the owners, such as for criminal history; suspensions and debarments; and federal tax delinquencies, among others. Even if a beneficial owner is disclosed but the owner is a figurehead, the due diligence program may not be able to uncover a company’s ineligibility or an improper relationship.[35]

Our prior work further illustrates how opaque beneficial ownership information can hide ineligibility to participate in programs based on requirements for obtaining contracts and awards set aside for small businesses. For example, in 2019, we reported on a fraud scheme where a company owner’s ineligible status was deliberately obscured to obtain service-disabled veteran-owned, set-aside contracts.[36] The true beneficial owner of the company recruited a disabled veteran to form the company with him and serve as figurehead. The disabled veteran was paid for allowing his name to be used by the business but worked full-time for another company in a different state and, according to a witness, was rarely in the office and did not approve any business decisions.[37] The company received $32.5 million in federal awards by falsely claiming that the company qualified as a service-disabled, veteran-owned small business from 2008 to 2015, when the beneficial owner knew that it did not.

|

Crosscutting Procurement and Eligibility Fraud Risks Associated with Beneficial Ownership Also Enabled Other Illicit Activity According to the information disclosed in late 2024 as part of a $52 million settlement agreement, one of the federal government’s largest providers of security and emergency response services devised a fraudulent scheme to control small businesses to obtain subcontracts reserved for woman-owned or service-disabled veteran-owned small businesses. To hide ineligibility and relationships, the provider company’s executives enlisted relatives and friends to serve as figureheads of the small businesses. For example, one executive’s wife used her middle and maiden name to hide the relationship, and her retired father, an elderly service-disabled veteran, served as a figurehead of a company to obtain service-disabled veteran-owned small business status. The small businesses allegedly paid kickbacks to the executives totaling over $11 million, concealed as consulting payments and made through various shell companies. The settlement further resolved allegations associated with false representations made by some of the small businesses to receive forgivable loans intended as pandemic relief for small businesses. Source: GAO analysis of Department of Justice information. | GAO‑25‑107143 |

By obscuring beneficial ownership information, bad actors can target more than one program, such as when applying for federal benefits and bidding on government contracts. Such crosscutting fraud schemes can have a wider impact on the government than on a single program or agency. We previously reported that during the COVID-19 pandemic, fraudsters targeted more than one pandemic relief program.[38] Specifically, in our analysis of fraud cases involving SBA’s Paycheck Protection Program and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan program, some individuals also allegedly defrauded unemployment insurance programs or offered fraudulent COVID-19 tests or personal protective equipment. Other related crimes included theft of government funds; small business grant fraud; and health care fraud, among others.[39]

By obscuring beneficial ownership information, fraudsters may target multiple programs at once or, by using eligibility fraud to misrepresent a certain status, such as a service-disabled, veteran-owned small business, open doors to fraud and abuse of other programs. See the sidebar for an illustrative example of a crosscutting fraud scheme, highlighting procurement and eligibility fraud risks associated with obscured beneficial ownership information.

Fraud Risks from Opaque Beneficial Ownership Can Result in Financial and Nonfinancial Impacts

Fraud schemes associated with opaque beneficial ownership information can result in financial losses and nonfinancial impacts to federal programs or operations. According to GAO’s Antifraud Resource, one fraud scheme could have a narrow impact on a sole individual, while another could

affect multiple individuals or groups.[40] Impacts of such schemes can be financial and nonfinancial in nature.

Financial Losses

|

Home Health Fraud Scheme Associated with Beneficial Ownership Billed Medicare Over $93 Million for Fictitious Services, Underscoring Loss to the Government and Illicit Financial Gain To conceal their identities, a man and a woman in Florida and their co-conspirators recruited foreign citizens to sign Medicare enrollment documents to appear as the owners of three home health agencies in Michigan. The pair and their co-conspirators used these home health agencies to submit over $93 million in Medicare claims for services that were not rendered using lists of stolen patient identities. Using dozens of shell companies and hundreds of bank accounts, they laundered and converted fraud proceeds into cash at ATMs and check cashing stores. In late 2023, the man and woman were convicted for conspiracy to commit health care fraud, wire fraud, and money laundering. All of the co-conspirators pled guilty. Source: GAO analysis of Department of Justice information. | GAO 25 107143 |

Fraud associated with opaque beneficial ownership information can result in financial losses and illicit financial gain. For example, in 2019 we reported on a case where two employees of a government prime contractor created a sham company to act as an additional subcontractor between the prime contractor and subcontractors, ultimately receiving $33.5 million in awards. The true nature of the ownership and control of the sham subcontractor were concealed by omitting facts and purportedly transferring ownership of the company to another individual who did not actually control the company. The sham subcontractor added no value to the government and carried no inventory but still submitted invoices for payment, causing prime contractors to overcharge DOD by including these fraudulent charges in the prime contractor invoices.[41]

Concealing company ownership can also result in illicit financial gain. For example, in 2020 we reported on a case where an aircraft sales broker fraudulently registered multiple aircraft in a bank fraud scheme.[42] From 2010 to 2011, the broker obtained multiple registration certificates from FAA for aircraft he did not rightfully own or possess. According to court records associated with this case, the broker submitted to FAA fraudulent registration applications and bills of sale with forged signatures for 22 aircraft to use as collateral as part of a multi-million-dollar bank fraud scheme. He used the registration documents that FAA provided as an asset to support a loan application that ultimately resulted in an approximately $3 million bank loan used to float his failing aircraft-sales business. See the sidebar for an illustrative example for a health care fraud scheme involving hidden beneficial ownership that resulted in losses to the government and illicit financial gain.

Nonfinancial Impacts

Although sometimes overlooked, the nonfinancial impacts associated with opaque beneficial ownership information are equally important because they can threaten national security or public safety. For example, in 2017, we reported on the security risks to the federal government regarding leases of foreign-owned space.[43] Leasing space in foreign-owned buildings—particularly where foreign ownership is unknown or undisclosed—presents risks to federal agency operations from espionage; unauthorized cyber and physical access to the facilities; and sabotage, based on our discussions with federal officials and selected real estate company representatives in 2017.

We have also previously reported on national security implications of challenges identifying beneficial owners for foreign transactions under the purview of the interagency Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States.[44] In 2018, we reported that member agency officials serving on the committee explained that it has become more challenging to identify the ultimate beneficial owners for the transactions that involve private and foreign government entities. These officials also noted the additional time and staff required to examine the national security implications of such transactions. In 2024, we found that transactions involving foreign investments in agricultural land can pose national security risks, when such land is located close to a sensitive military base.[45]

National security impacts of opaque beneficial ownership information can also arise from sanctions evasion. For example, we reported in 2023 on World Bank contracts awarded to entities whose true owners may have been listed on selected U.S. sanctions and other lists of parties of concern, according to our analysis of these lists.[46]

Concealing beneficial ownership can further impact national security in the context of U.S. elections as well as access to sensitive military technology. For example, the 2022 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment reported on how corruption could impact U.S. elections because such activity can be difficult to detect as perpetrators seek to conceal their involvement by obfuscating their identity.[47] Specifically, the risk assessment described a case that involved individuals who set up corporate entities to anonymously funnel contributions to a candidate’s reelection campaign. These unlawful campaign contributions were designed to illegally influence elections in the U.S. The individuals were convicted on public corruption and bribery charges for their actions to covertly direct illegal campaign contributions to a candidate for public office in return for a favorable action by the candidate.

We also reported in 2019 on a case that involved a transfer of military technology and sensitive data to individuals in a foreign country.[48] Two shell companies misrepresented the location of their manufacturing facility as domestic when bidding for DOD contracts, contrary to eligibility requirements. As government contractors, the shell companies provided spare parts manufactured in a foreign facility. The companies transferred drawings of military technology and sensitive military data to an individual in a foreign country without the proper license or approval. Quality-control issues with the parts that were ultimately provided to DOD led to the grounding of 47 fighter aircraft, posing safety risks.

Public safety impacts can also arise from hidden ownership. For example, we reported in 2012 on public safety impacts associated with “chameleon carriers,” which refers to the practice whereby motor carriers register using a new identity to avoid enforcement actions from interstate commerce for safety reasons. Carriers may do this to disguise their former identity to evade enforcement actions issued by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA), the federal agency responsible for overseeing motor carrier safety. By disguising beneficial ownership and prior safety violations through a new company identity, the chameleon carrier can continue its unsafe operations, exposing others to potential physical harm. Our 2012 report describes a case where a chameleon carrier operating a bus was involved in a crash in Texas that killed 17 passengers and injured several others.[49] The National Transportation Safety Board investigation found that the FMCSA had ordered this chameleon carrier out-of-service 2 months prior to the crash.

OIGs Face Fraud Detection and Response Challenges in Identifying Beneficial Owners Across Multiple Data Sources

CIGIE members and OIG roundtable participants informed us that they use various federal, state, and commercial data sources to identify beneficial owners as part of their fraud detection and response efforts.[50] They further noted that using these data sources to identify beneficial owners can be time-consuming, unreliable, and require significant resource investments.

Federal Data Sources

CIGIE members and roundtable participants said they use federal data sources as part of their fraud investigations involving beneficial owners. For example, CIGIE members and roundtable participants said these sources include databases from the U.S. Library of Congress; the Federal Procurement Data System – Next Generation; USAspending.gov; and SAM, among others.[51]

Investigators may use SAM during an investigation.[52] According to CIGIE members, OIG investigators may look for common values in certain fields in SAM that can indicate that an owner is a figurehead for a set-aside fraud case, a potential excluded party, or is reinventing themselves as a new company.

According to our review of a GSA OIG report, an investigation determined that an individual, who was debarred from getting U.S. government contracts due to prior misconduct, created multiple companies in SAM using fictitious names to circumvent their previous debarment. The individual obtained more than 1,000 government contracts, valued at more than $2.2 million. As a part of the scheme, the individual defrauded the government by obtaining contract payments from DOD for supplies that were never provided.[53]

One OIG also reported that identifying beneficial owners is time-consuming and costly. One roundtable participant said that, prior to them coming to the OIG, one beneficial ownership investigation required months of researching information from various data sources, including SAM.

State Data Sources

CIGIE members and roundtable participants reported using secretary of states’ information to help identify beneficial owners during an investigation.[54] However, officials identified limitations with state registry data. Identifying beneficial owners of a company generally requires accessing states’ records for registrations, but this data source is not a reliable means of identifying potential fraud or beneficial owners.

This is because state systems are generally not standardized, according to CIGIE members and roundtable participants. For example, the fields and standard business identifiers vary by state. As a result, one CIGIE member explained that it is time-consuming to find and structure the results into a consistent data format for analysis to identify beneficial ownership across multiple companies. In addition, one CIGIE member and roundtable participants told us that some state systems may require special accounts or paid access, which can inhibit fraud detection efforts. We have previously reported how the time it takes to use these systems and obtain beneficial ownership information can delay an investigation.[55]

Commercial Data Sources

One CIGIE member and one roundtable participant described using commercial data sources to help uncover beneficial owners. For example, one CIGIE member told us that they used commercial resources, such as Westlaw®, to help conduct investigations within their office.[56] A roundtable participant told us they rely on commercially available products, such as Accurint, to help investigate fraud associated with opaque beneficial ownership.[57] These resources have associated costs to obtain access.

OIGs Face Challenges in Identifying Beneficial Owners Across Various Analytic Tools

OIGs face challenges in identifying beneficial owners and linkages between them, when using internal and external analytic tools. Specifically, they explained to us that it is difficult to identify hidden connections through unique characteristics, such as bank accounts. Using internal and external data analytic tools can be resource intensive, according to roundtable participants, CIGIE members, and congressional testimony from the Chair of the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee (PRAC), which is a CIGIE committee.

Internal Analytic Tools and Resources

Some OIGs use internal analytic resources to proactively investigate beneficial ownership and detect concealed relationships. However, they explained that identifying concealed relationships between entities is difficult, and some connections may not be detected.

According to one CIGIE member, if OIGs seek to proactively identify beneficial owners, they can look for common values in certain data fields within their investigative case management systems. For instance, one roundtable participant told us that their offices conduct data analytics to link entities via key variables, such as the entity’s address, internet protocol address, and bank account. Because “beneficial ownership” is unlikely to be a keyword present in case management systems, reviewing key variables may provide insight into information on owners that may not otherwise be captured, allowing for data matching across various sources, according to CIGIE members.[58] If an OIG is investigating a fraud allegation related to research grant dollars, according to PRAC Chair congressional testimony, it must engage in a manual process to determine what other agencies may have funded that entity or if the funded program overlaps with other federal funding.[59] Hidden connections between different fraud schemes and bad actors may never be detected because information such as shared bank accounts, email addresses, phone numbers, and other unique characteristics are difficult to compare without a centralized system, according to the PRAC testimony.

External Analytic Tools and Resources

Some OIGs may use external resources—such as contractors and data analytic capabilities provided by the PRAC—to prevent and detect fraud, waste, and abuse. Some resources, such as the PRAC, work with OIGs to ensure that taxpayer money is being used effectively to prevent and detect fraud, waste, and abuse through leading-edge data insights and analytics tools, while other external resources can be expensive.[60] A roundtable participant described a resource-intensive example where external assistance was needed to identify the beneficial owner in a company hierarchy. The participant told us they worked with a team of contractors to conduct the research that ultimately determined that the owner of the company was the government of another country. This process was expensive and time-consuming, according to the participant.

OIGs Expect the Company Registry Could Support Fraud Detection and Response, but Are Concerned About Data Accuracy, Use, and Retrieval

OIGs told us that the company registry could support their fraud detection and response efforts, in response to our survey, roundtable discussion, and interviews with CIGIE members. Specifically, information on beneficial owners could support OIG investigations, data analytics, and fraud awareness and training efforts. However, OIGs also expressed concerns about data accuracy, use, and retrieval of bulk data from the company registry.

OIGs Identified Ways That Company Registry Data Could Support Their Efforts

OIGs identified ways that company registry data could support investigations, data analytics, and fraud awareness and training efforts.

Investigations

Company registry data could support investigations involving opaque beneficial ownership, according to roundtable participants, CIGIE members, and survey results. Company registry data could allow OIGs to use beneficial ownership information in the aggregate to support their investigations. With information in a single dataset, OIGs could more easily identify connections to an individual or entity under investigation in complex fraud schemes. For example, one roundtable participant described a past experience trying to identify the true owner in a company hierarchy. The investigation required months of reviewing disparate sources of information, including public reports, to determine that the registered owner was not the beneficial owner.

Even if the information in the company registry is incomplete, it could support investigations involving opaque beneficial ownership better than what is currently available. One roundtable participant said it is difficult to find beneficial ownership information for entities in the U.S. due to differing state reporting requirements regarding what information entities must report and who can access that information. Further, beneficial ownership information obtained at the state level is also often limited to what is readily available to the general public, according to a roundtable participant.

Company registry data could also reduce time and staff resources required for identifying the beneficial owner during an investigation. For example, one survey respondent noted that company registry data could become a “force multiplier” for smaller OIGs by enhancing oversight capabilities without requiring additional staff resources. The company registry could also help OIGs to scope investigations if the registry has an automated process for reviewing information, according to a CIGIE member.

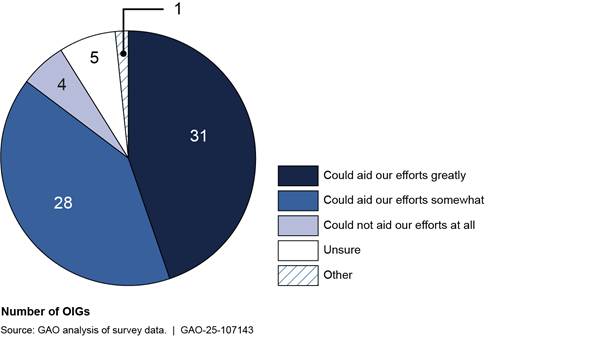

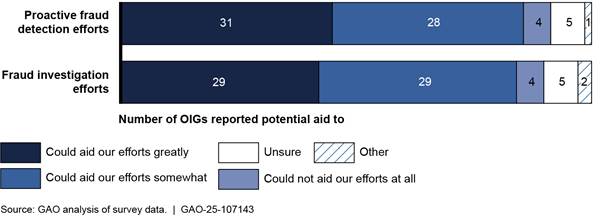

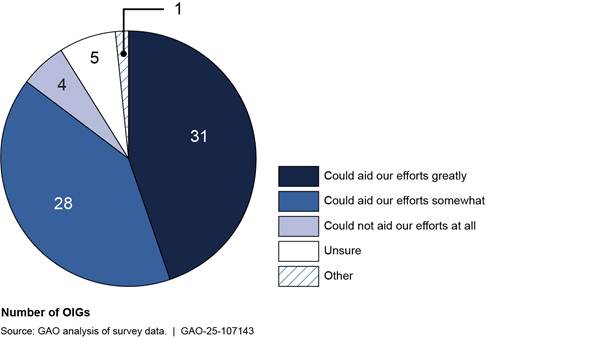

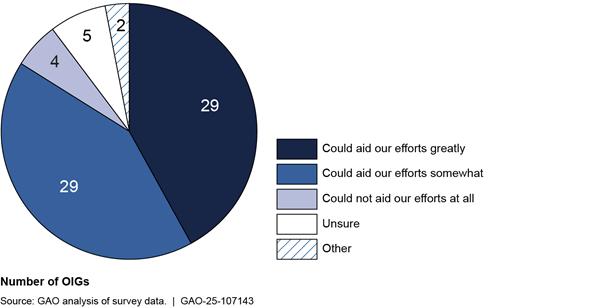

The majority of OIGs responding to our survey saw company registry data as potentially helpful for fraud investigation efforts. Specifically, 58 of 69 OIGs responded that access to such information could greatly or somewhat aid their office’s fraud investigation efforts, as shown in figure 1 below.[61]

Figure 1: Usefulness of Beneficial Ownership Information to Fraud Investigation Efforts, According to Offices of Inspectors General (OIG) Survey Responses

Data Analytics

Company registry data could support OIGs’ efforts to use data analytics to identify beneficial owners in a particular case as well as provide data in a consistent format needed for broader analyses to support fraud detection efforts. For example, set-aside fraud schemes may be easier to detect, according to a roundtable participant, since conducting data analytics activities with company registry data could reveal hidden affiliations between companies that may be cooperating to circumvent requirements for set-aside contracts. Consistently formatted data from the company registry could also enable OIGs to overlay company registry data with their program data. For example, according to a roundtable participant, they could overlay company registry data with their program data on set-aside contracts to identify ineligible individuals.

Access to company registry data could reduce current challenges when searching state records for businesses that may be registered across many states, according to CIGIE members. OIG investigators may need to locate individual business records in each state, and each state offers different data elements, formats, and access to information. From an analytics perspective, this makes it difficult to structure the data in a consistent format for analysis, according to CIGIE members. In the absence of company registry data, OIGs must piece company data together by paying for access to information and using inconsistently formatted search features, variables, and business identifiers for their analytic efforts.

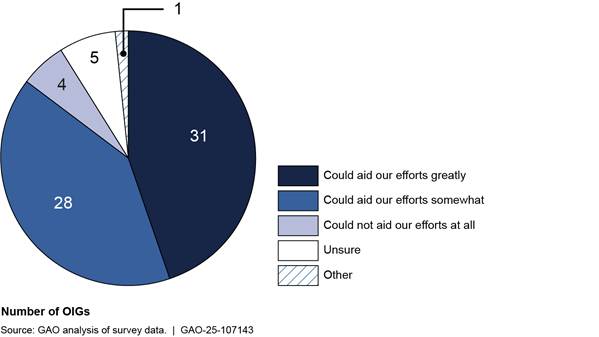

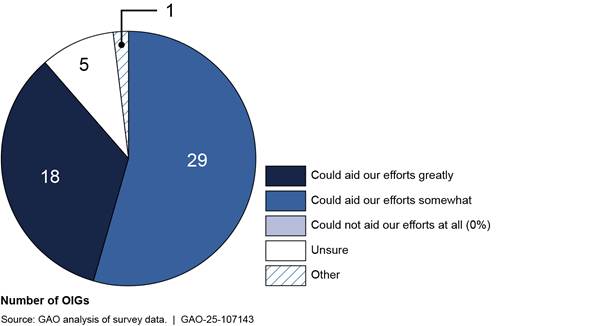

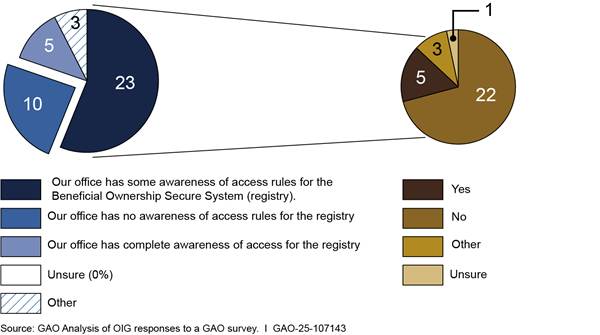

The OIGs we surveyed also noted the potential utility of the company registry for data analytics, such as building proactive fraud analytic models that produce actionable results and assist in active investigations. Specifically, 59 of 69 OIGs responded that access to company registry information could greatly or somewhat aid their office’s proactive fraud detection efforts.[62] See figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Usefulness of Beneficial Ownership Information to Fraud Detection Efforts, According to Offices of Inspectors General (OIG) Survey Responses

Fraud Awareness and Training

Company registry data could support OIGs’ fraud awareness and training efforts. In addition to saving time and resources, as previously discussed, access to company registry data could provide beneficial ownership risk information that OIGs could integrate into their fraud awareness and training efforts for program and agency officials. According to CIGIE members, OIGs see an opportunity to incorporate illustrative use of beneficial ownership information from the company registry into their fraud awareness and training efforts to increase program managers’ understanding of the risks associated with beneficial ownership.

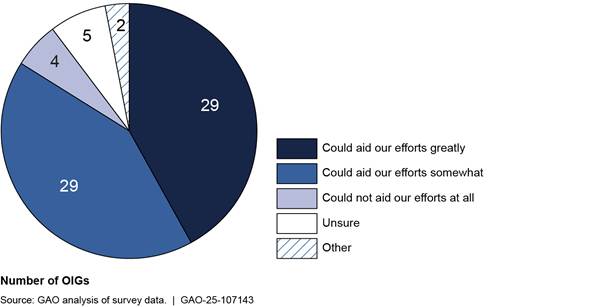

Similarly, the OIGs we surveyed noted the potential utility of the company registry for their fraud awareness and training efforts. Specifically, 47 of 53 OIGs responded that access to company registry information could greatly or somewhat support their office’s fraud awareness and training efforts.[63] See figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Usefulness of Beneficial Ownership Information to Fraud Awareness Efforts, According to Offices of Inspectors General (OIG) Survey Responses

Access to the company registry may also encourage more OIGs to engage in fraud awareness and training efforts with program managers. For example, one survey respondent told us their OIG does not currently have fraud awareness and training efforts aimed at program managers on the risks associated with beneficial ownership information, but it could with future access to the company registry.

OIGs Identified Potential Limitations with Data Accuracy, Use, and Retrieval in Using Company Registry Data

The accuracy and reliability of the data being entered into the company registry, data-use restrictions, and mechanisms for data retrieval are potential limitations in using company registry data, according to roundtable participants and CIGIE members.

Accuracy and Reliability of Company Registry Data

The accuracy and reliability of the information entered into the company registry is a potential limitation OIGs could face in using company registry data. All roundtable participants voted this limitation as a top challenge, since inaccurate information in the company registry could impact its utility. See table 1 for a complete listing of limitations OIGs could face in using company registry data as identified by roundtable participants.[64]

Table 1: Roundtable Discussion Participants’ Reported Potential Limitations in Using the Company Registry of Beneficial Ownership Information

|

Limitation identified during the roundtable discussion |

Number of votes for this limitation |

|

The accuracy and reliability of the information |

7 |

|

Who the data can be shared with |

5 |

|

The ability to download the data in bulk to overlay with program data |

5 |

|

Sourcing the information |

3 |

|

The ability to access bulk data to connect with internal analytic and data systems |

3 |

|

Whether a specific OIG can access the company registry |

2 |

|

Scale |

2 |

|

The instructions for updating the information |

2 |

|

Who within the OIG can access the information |

1 |

|

The repercussions for someone entering invalid information |

1 |

|

Whether the source allows the information to be shared |

0 |

|

The security of the information once shared |

0 |

Source: GAO analysis of roundtable vote responses. I GAO‑25‑107143

Note: Seven Offices of Inspectors General (OIG) voted on potential limitations, but votes may not total 21 votes. Some OIGs sent more than one representative to the roundtable discussion. To count the vote on the potential limitations, we consolidated those representatives as belonging to one OIG office.

One roundtable participant asked if the company registry data are validated. For example, two companies could be owned by the same individual, but the name and address of that individual might be reported differently for the two companies, making it appear they have different owners. This could result in inconsistent beneficial ownership information that further complicates the process of identifying the true beneficial owner. Another roundtable participant told us it is important to know the quality of the data, which can help ensure that a user does not introduce inaccurate or unreliable information into the OIG’s analysis. Verifying the accuracy of the data is further complicated for the OIG because companies can change at any time or could become inactive, according to a roundtable participant.

FinCEN officials acknowledged these accuracy and reliability limitations in company registry data, noting they received comments from the public during the rulemaking process that were similar to the OIGs’ concerns. According to its reporting rule, the structure of the CTA makes a deliberate choice to place this responsibility on the reporting company.[65] In addition, it is unlawful for a reporting company to willfully provide false or fraudulent beneficial ownership information to FinCEN. Any reporting company that does so faces a civil penalty of not more than $500 for each day that the violation continues or has not been remedied and may be subject to a fine of not more than $10,000, imprisonment for not more than 2 years, or both.[66]

During a demonstration of the company registry, FinCEN officials explained to us that there are processes for validating information formats, such as making sure that the image of the identification is in a certain format. They further explained, however, that the accuracy or reliability of the information entered is not automatically verified beyond checking the format and completeness of mandatory fields.[67] According to officials, beginning in May 2024, FinCEN conducted certain manual data validation sampling checks to begin assessing the accuracy and reliability of reported information. In addition, FinCEN officials noted that it entered into a contract to further explore data validation efforts.

Data-Use Restrictions

Data-use restrictions are potential limitations OIGs could face in using company registry data for their fraud investigations and awareness efforts. Several roundtable participants voted on this limitation as a top challenge, since not being able to share company registry data with external partners could impact the data’s utility. Uncertainty on how company registry data can be shared with OIGs’ external partners, such as contractors supporting an OIG investigation, could be a challenge for OIGs, according to one roundtable participant. Traditionally, OIGs work around data-use restrictions by subpoenaing records during an investigation, but it is unclear how this method will work when using company registry data, according to one roundtable participant.

In response, FinCEN officials told us that, as required by the CTA, FinCEN has implemented regulations and strict protocols to protect the sensitive personally identifiable information reported to FinCEN. The regulations specify the circumstances in which authorized users have access to beneficial ownership information, along with data protection protocols and oversight mechanisms applicable to each user category.[68]

Mechanisms for Data Retrieval

Mechanisms for data retrieval, primarily the ability to download beneficial ownership information in bulk, are potential limitations OIGs could face in using company registry data for their fraud investigation efforts. Several roundtable participants voted on this limitation as a top challenge, since not having mechanisms for such data retrieval could impact the company registry’s utility. Specifically, if FinCEN allows bulk downloading, an OIG could overlay company registry data with program data to examine how programs could be affected by issues involving beneficial ownership, according to a roundtable participant. In the context of data analytics across multiple companies, bulk downloading could allow OIGs to overlay company registry data with program data and help efforts to identify ineligible individuals who are receiving set-aside contracts, according to a roundtable participant.

FinCEN officials told us they are exploring mechanisms for data retrieval related to bulk downloading from the company registry. During a demonstration of the company registry for GAO, FinCEN officials stated that it can be feasible for company registry users to download up to 5,000 records of data at a time. Officials also told us that during the phased rollout process to provide company registry access, which we will discuss below, they will solicit feedback on the limitations and challenges identified during our OIG roundtable discussion. Further, FinCEN officials told us that they will continue to study the issue of adding a bulk download capability to the company registry but will need to do so within the context of privacy and disclosure concerns set forth in the CTA and regulations.

Opportunities Exist for FinCEN to Communicate with OIGs About the Company Registry

Communicating with OIGs Before Finalizing Registry Access Plans Can Facilitate Registry Use to Mitigate Program Fraud

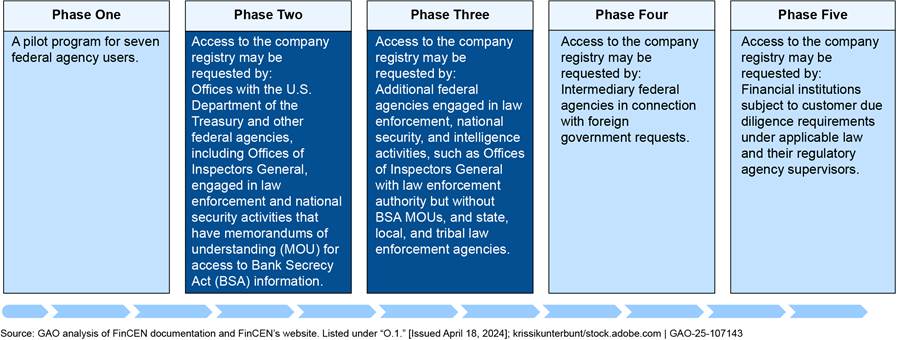

FinCEN plans to conduct outreach to agency participants and other stakeholders, as needed, regarding company registry access, according to FinCEN documentation. According to officials, select OIGs will be included in the early phases of the company registry rollout schedule. Specifically, FinCEN plans to allow OIGs with law enforcement authority to request access in phases 2 and 3, as described in figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s (FinCEN) Phased Approach for Requesting Access to Company Registry of Beneficial Ownership Information

According to officials, FinCEN’s phase two plans include allowing access requests from certain federal agencies, including OIGs, engaged in law enforcement and national security activities that have BSA memorandums of understanding (MOU) on file.[69] At the start of phase two in September 2024, FinCEN sent an announcement instructing agencies on how to initiate a company registry access request. FinCEN officials told us they have communicated with OIGs that have BSA MOUs about their eligibility to access the registry. As of October 2024, officials told us that five OIGs have submitted requests to access the company registry and that FinCEN was in the process of reviewing those requests.[70]

According to officials, FinCEN’s phase three plans include allowing access requests from additional federal agencies engaged in law enforcement, national security, and intelligence activities, including OIGs with law enforcement authority that do not have existing BSA MOUs on file. In October 2024, FinCEN officials told us they were developing outreach plans for phase three.

In March 2025, FinCEN officials told us that once required agreements are in place and required documents have been received from authorized agencies and institutions seeking access to the beneficial ownership portal, FinCEN will allow access to the company registry through the beneficial ownership portal.

As the coordinating body for the OIG community’s collective interests, needs, and challenges, CIGIE has not received communication from FinCEN on information about the company registry and access to the system, according to CIGIE members.[71] Some CIGIE members with existing BSA portal access told us they had received information on the company registry, but they were unclear on who had access to the company registry data. For example, CIGIE members told us they believed company registry data would be available only to OIGs that had existing BSA MOUs on file. However, as discussed above, phase three of the company registry rollout will expand access requests to OIGs with law enforcement authority that do not have existing BSA MOUs on file.

CIGIE members were also unclear on how company registry data could be used and were concerned that the OIG community would need additional information to clarify appropriate use. For example, CIGIE members told us that it has been ingrained within the OIG community that FinCEN data, such as suspicious activity reports, are generally for criminal investigative purposes only. CIGIE members told us that the broader OIG community would need to be made aware of the fact that company registry data can be used beyond criminal investigations. As noted above, law enforcement agencies, including OIGs, can use beneficial ownership information to combat illicit financial activities by pursuing criminal or civil investigations. Similarly, as discussed, OIGs have concerns about the mechanism for company registry data retrieval using bulk data downloading, which has not been resolved.

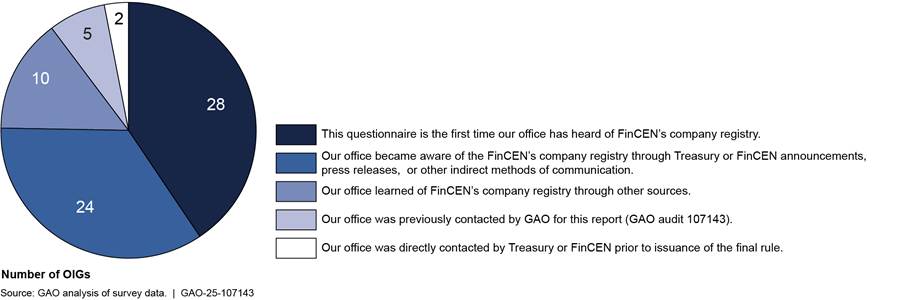

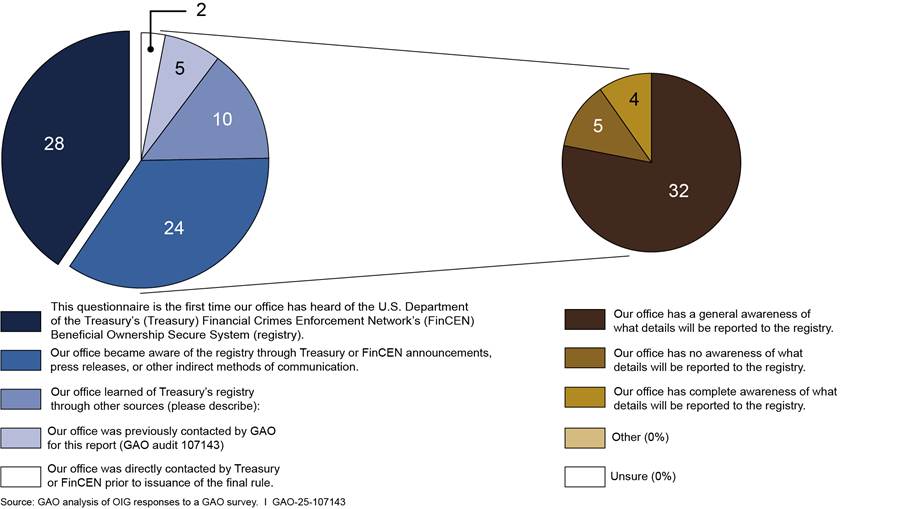

In addition, OIGs responding to our survey reported receiving varying levels of communication from FinCEN about the company registry. Specifically, 26 of 69 OIGs responded that they became aware of the company registry through Treasury or FinCEN sources of information.[72] See figure 5.

Figure 5: Awareness of the U.S Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s (FinCEN) Company Registry, According to Inspectors General (OIG) Survey Responses

FinCEN officials explained that they have not communicated with OIGs about the company registry outside of public announcements and what is publicly available on FinCEN’s company registry website. Officials said that FinCEN answers questions about company registry access on an individual basis. However, FinCEN officials reported that they are open to discussions with the OIGs and suggestions as to how they could best communicate with the OIGs. According to those same officials, they are also open to OIGs sharing their knowledge with FinCEN on the indicators of potential fraud associated with beneficial ownership in federal programs.

Further, CIGIE members told us they would be interested in communicating with FinCEN on OIGs’ access to the company registry, including the data retrieval concerns discussed above. CIGIE members also noted their interest in sharing information broadly within the OIG community on how company registry data can be used beyond criminal investigations.

In rolling out the company registry, FinCEN has opportunities to externally communicate quality information, consistent with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government and Treasury’s Fiscal Year 2022 – 2026 Strategic Plan.[73], [74] As noted above, according to Treasury’s Strategic Plan, FinCEN aims to increase transparency in the domestic and international financial system to aid law enforcement agencies in the detection of illicit financial activity. Communicating information about the company registry to OIGs aligns with this goal.

As mentioned above, the CTA has been subject to ongoing litigation and implementation changes. In March 2025, Treasury announced plans to narrow the scope of the rule implementing the CTA to foreign-owned reporting companies. As a result, the ongoing litigation and implementation changes are affecting the rollout of the company registry and will limit beneficial ownership information available to OIGs.

By communicating with CIGIE—which represents the OIG community, facilitates collaboration, and gathers information about its members’ needs and challenges—FinCEN would be better positioned to identify and address current and future crosscutting challenges related to the fraud detection and response needs of the OIG community. During the registry rollout, such communication could help clarify (1) access for OIGs with and without BSA MOUs to the registry; (2) the OIGs’ use of company registry data beyond criminal investigations; and (3) mechanisms for data retrieval, such as bulk downloading.

Further, such communication could position FinCEN and the OIG community, through CIGIE, to better mitigate federal program fraud risks involving beneficial ownership information. These actions also support Treasury’s strategic goal to significantly improve the ability to mitigate illicit finance risk through law enforcement and other authorized users’ access to beneficial ownership information.

Conclusions

Fraud in federal programs remains a significant and persistent problem and reinforces the importance of federal program oversight. This oversight includes the efforts of OIGs to detect and respond to fraud risks associated with opaque beneficial ownership information. Such risks appear across procurement, grant, and federal benefit programs.

With access to FinCEN’s company registry data, OIGs would be better positioned to break through opaque ownership information that heightens the risk of procurement-, grant-, and eligibility- related fraud in federal programs and operations. For example, use of company registry data can result in less time spent on an investigation identifying the true owner of a company and in cost and time savings within OIGs’ fraud detection and response efforts.

However, OIGs identified a number of potential challenges in using the company registry data. Communication from FinCEN to OIGs, through CIGIE, can raise awareness among OIGs about the company registry and help address challenges related to the fraud detection and response needs of the OIG community. Overall, such communication could help FinCEN to better achieve its goal to increase transparency in the domestic and international financial system to aid law enforcement agencies in the detection of illicit financial activity. This could help OIGs to execute their mission to detect and respond to potential fraud perpetrated by private companies obscuring beneficial ownership, thus enhancing oversight across the entire federal government. Lastly, Treasury’s plans to narrow the scope of the rule implementing the CTA to foreign-owned reporting companies will reduce the amount of beneficial ownership information available in the company registry for OIGs, while fraud risks posed by obscured beneficial ownership information remain. This heightens the need for clarity from FinCEN on information available for OIG fraud detection and response purposes.

Recommendations for Executive Action

The Secretary of the Treasury should ensure that the Director of FinCEN communicates with CIGIE on OIGs’ use of company registry for fraud detection and response during the registry rollout. Specifically, FinCEN should communicate with CIGIE regarding OIGs’ (1) access to the company registry, (2) use of company registry data beyond criminal investigations, and (3) reported limitations in using company registry data. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to Treasury and CIGIE for review and comment. FinCEN provided technical comments on our report, which we incorporated as appropriate. In a letter to GAO, reproduced in appendix IV, FinCEN did not comment further on our report or our recommendation. FinCEN stated that it would be premature to provide further feedback given the proposed rulemaking that Treasury plans to issue to narrow the scope of the beneficial ownership information reporting rule.[75]

In its comments, reproduced in appendix V, CIGIE agreed with our recommendation, stating that it concurred with our findings. CIGIE urged FinCEN to collaborate closely with CIGIE and the OIG community to develop a more effective data access and exchange framework. Additionally, CIGIE noted that our review of USAspending.gov identified 168,000 unique companies receiving federal contracts of financial assistance in fiscal year 2023, amounting to nearly $6.2 trillion. CIGIE observed, however, that USAspending.gov lacks detailed information on all entities conducting business with the Federal government, which we also acknowledge.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 20 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of the Treasury, and the Executive Director of CIGIE. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Rebecca Shea at SheaR@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VI.

Rebecca Shea, Director

Forensic Audits and Investigative Service

This report (1) describes federal program fraud risks associated with opaque beneficial ownership information and related challenges that Offices of Inspectors General (OIG) face with detection and response, (2) describes OIGs’ perspectives on the use of the Beneficial Ownership Secure System (company registry), and (3) assesses the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s (FinCEN) actions to communicate with OIGs about company registry data.

As part of this work, we determined that internal controls were significant to our work. Specifically, the principle that management should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives, as outlined in the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, was significant to our third objective.[76] To assess the control activity in the third objective, we analyzed relevant company registry documentation, interviewed FinCEN officials and members of the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency (CIGIE) on efforts to communicate with OIGs during the phased rollout to provide access to the company registry, and analyzed OIGs’ survey and roundtable participant responses.[77] In sections below, we provide more detailed information on the steps taken to conduct our OIG survey and roundtable discussion and to perform our data analysis.

To describe federal program fraud risks associated with opaque beneficial ownership information and related challenges OIGs face with fraud detection and response, we reviewed relevant GAO reports, OIG semiannual reports, and risk assessments from Treasury for illustrative examples on the types of fraud risks associated with opaque beneficial ownership information and examples of closed cases featuring fraud schemes associated with opaque beneficial ownership. We also obtained information from our roundtable discussion with seven selected OIGs to learn about their views on the challenges faced to identify the beneficial owner within their fraud detection and response efforts. In addition, we interviewed CIGIE members on the federal program fraud risks associated with opaque beneficial ownership and the related challenges OIGs face with federal program fraud detection and response efforts.

To describe OIGs’ perspectives on the use of the company registry, we conducted a survey of federal OIGs, held a roundtable discussion with selected OIGs, and interviewed members of CIGIE and FinCEN officials.

1. We surveyed the 72 federal OIGs from April 2024 through August 2024 to capture OIG views on how information from a company registry could aid their fraud detection and response efforts.[78] We obtained 69 responses, for a response rate of 96 percent. See below for further details on our survey methodology. Appendix II contains the survey questions and complete results with response percentages for applicable questions.