HIGHER EDUCATION

College Student Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Care

Report to the Ranking Member Committee on Education and Workforce

House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107151. For more information, contact John E. Dicken at (202) 512-7114 or dickenj@gao.gov, or Melissa Emrey-Arras at (202) 512-7215 or emreyarrasm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107151, a report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Education and Workforce, House of Representatives

College Student Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Care

Why GAO Did This Study

About 19 million students were enrolled in nearly 3,900 degree-granting colleges across the U.S. during the fall 2022 semester. Many colleges have student health centers that provide health care to the students on their campuses. Among other things, student health centers may offer sexual and reproductive health care, which includes things such as STI testing and prevention; contraception; emergency contraception; pregnancy testing; abortion; and menstrual products. In June 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that the U.S. Constitution does not confer the right to abortion.

GAO was asked to review college students’ access to sexual and reproductive health care. This report describes: (1) the availability of on-campus sexual and reproductive health care at selected colleges; (2) challenges students faced in seeking sexual and reproductive health care at selected colleges and efforts those colleges took to address them; and (3) how the availability of sexual and reproductive health care at selected colleges changed since the start of the 2021-2022 academic year.

GAO interviewed officials from a nongeneralizable sample of 15 colleges, selected on the basis of program length, location, religious affiliation, size, and other factors. GAO also interviewed three professional organizations and four colleges’ health educators. GAO also analyzed data from the American College Health Association’s Sexual Health Services Survey for calendar year 2022, the most recent available.

What GAO Found

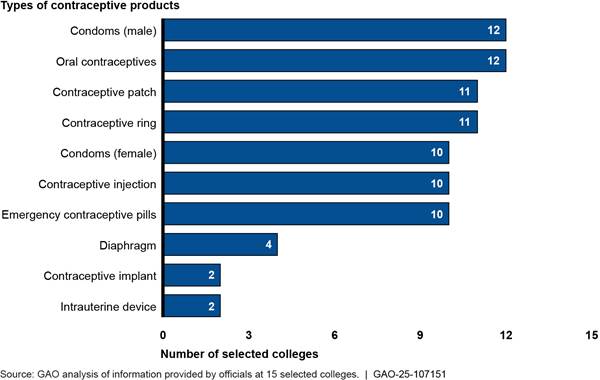

Most of the 15 selected colleges GAO interviewed offered a variety of on-campus sexual and reproductive health care for students through their student health center. For example, officials at all of the colleges said they offered menstrual products and pregnancy tests, and 12 of the 15 colleges offered sexually transmitted infection (STI) tests. Among contraceptives, college officials said male condoms and oral contraceptives were most commonly available (at 12 of the 15 colleges), while contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices were less commonly available. Medication abortion was available at one college and procedural abortion was not available at any, according to college officials. Various factors affected sexual and reproductive health care offered on campus, including costs, colleges’ interpretation of state laws, political sensitivities, and religious affiliation, according to college officials.

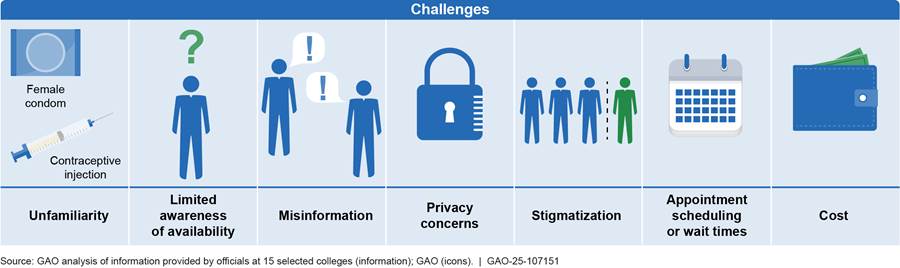

Officials at the selected colleges said students faced challenges seeking sexual and reproductive health care on campus, including unfamiliarity with sexual and reproductive health care, privacy concerns, and cost, among others (see figure). The selected colleges took various actions to address challenges, such as

· holding on-campus educational events;

· using health educators to share information; and

· implementing measures to enhance privacy at their student health center.

Officials at 14 selected colleges said they did not offer any abortion services before or after the start of the 2021-2022 academic year—the year prior to the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization—and officials at one said they began offering medication abortion in February 2021 due to state law. Officials at one college said they discontinued offering off-campus referrals for abortion services due to their state’s political environment. In addition, officials at six colleges said some students asked more questions or otherwise expressed more uncertainty about their ability to access abortion services after the start of the 2021-2022 academic year. Officials at most colleges said availability and demand increased for other on-campus sexual and reproductive health care, such as pregnancy testing and contraception.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

ACHA |

American College Health Association |

|

HIV |

human immunodeficiency virus |

|

HPV |

human papillomavirus |

|

IUD |

intrauterine device |

|

PEP |

post-exposure prophylaxis |

|

PrEP |

pre-exposure prophylaxis |

|

STI |

sexually transmitted infection |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 31, 2025

The Honorable Robert C. “Bobby” Scott

Ranking Member

Committee on Education and Workforce

House of Representatives

Dear Mr. Scott:

About 19 million students were enrolled in nearly 3,900 degree-granting colleges across the United States during the fall 2022 semester.[1] Many colleges have student health centers that provide health care to the students on their campuses. Among other things, student health centers may offer sexual and reproductive health care, such as contraception, sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing, and medication abortion.[2] These health centers may provide the main or sole source of primary health care for some students.

Sexual and reproductive health care can be particularly important for the health and educational outcomes of college students, about two-thirds of whom were aged 24 and younger during the fall 2021 semester.[3] For example, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 58 percent of cases of chlamydia and 40 percent of cases of gonorrhea occurred among individuals aged 15 to 24 in 2022.[4] Left untreated, such STIs, as well as other conditions, can have serious health consequences, such as infertility. Additionally, individuals aged 20 to 24 had the highest rate of unintended pregnancies of all age groups in 2019.[5] While many students with children are able to successfully complete a degree, some face challenges doing so. For example, a 2021 study found that about 52 percent of parenting students left college without a credential compared to 29 percent of students without children.[6]

In June 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (Dobbs decision) that the U.S. Constitution does not confer the right to abortion.[7] Since then, some states have taken actions to change or maintain access to some sexual and reproductive health care.

You asked us to review college student access to sexual and reproductive health care on college campuses. In this report, we describe

1. the availability of on-campus sexual and reproductive health care at selected colleges;

2. challenges students faced in seeking sexual and reproductive health care at selected colleges and efforts those colleges took to address them; and

3. how availability of on-campus sexual and reproductive health care at selected colleges changed since the start of the 2021-2022 academic year.

To obtain information for all three objectives, we interviewed officials from a nongeneralizable sample of 15 degree-granting colleges that had student health centers, including officials with expertise in student affairs and services provided through their college’s student health center. We selected colleges to obtain variation in (1) sector (eight public and seven private nonprofit); (2) program length (two 2-year and 13 4-year); (3) affiliation (12 secular and three religiously affiliated); (4) population density of the surrounding area (11 urban and four rural); and (5) size of student enrollment (five with fewer than 5,000 students [“small colleges”]; four with 5,000 to 19,999 students [“medium colleges”]; and six with 20,000 or more students [“large colleges”]).[8] We also selected colleges across states that had varied laws related to access to sexual and reproductive health care. We did not include colleges that offered predominantly or exclusively online programs, or colleges that did not grant degrees, because we found they were less likely to have a student health center.

We interviewed officials at the selected colleges from March 2024 through July 2024. We asked about changes in the availability of sexual and reproductive health care on campuses since the start of the 2021-2022 academic year to capture any changes in the academic year preceding the Dobbs decision, in addition to the time afterward.

For all three objectives, we also interviewed representatives from three key selected professional organizations knowledgeable about health care provided on college campuses and four selected colleges’ health educators.[9]

To supplement the information obtained through interviews for the first objective, we also analyzed nongeneralizable data from the American College Health Association’s (ACHA) 2022 Sexual Health Services Survey. Every two years, ACHA surveys its member colleges about the sexual and reproductive health care offered on their campuses. To assess the reliability of those data, we reviewed related documentation, interviewed ACHA officials about the data, compared the data against published totals, and conducted checks for missing or erroneous data. See appendix I for more information on our methods for analyzing the survey data. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objective.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Sexual and Reproductive Health Care

Sexual and reproductive health care encompasses a broad range of products and services, including, among other things:

· STI testing. Testing is available for a variety of infections that can be transmitted through sexual contact, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, HIV, hepatitis B and C, and human papillomavirus (HPV), among others. Laboratory testing is generally used to diagnose STIs, and could involve testing blood, urine, or a swab of cells or fluids. STIs can cause serious complications if left untreated, such as infertility and organ damage.

· HIV prevention. Medicines are available for individuals who are at risk of exposure to HIV or who may have already been exposed to HIV. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is available for individuals who are at risk of exposure by prescription as a daily pill or an injection taken every 2 months to prevent contracting HIV. Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is a course of daily prescription pills that must be started within 72 hours of a possible exposure to HIV to prevent contraction.

· Contraceptives. Contraceptives are medicines or devices to prevent pregnancy. Some contraceptives are available over the counter, such as male and female condoms, whereas others require a prescription. Some are self-administered, such as oral contraceptives, whereas others are administered by a provider. See table 1 for descriptions of selected contraceptives.

|

Contraceptive |

Description |

|

Male condom |

A thin sheath that covers the penis and collects sperm. May also prevent sexually transmitted infections. Available over the counter. |

|

Female condom |

A thin plastic pouch that is inserted into the vagina before sex and collects sperm. May also prevent sexually transmitted infections. Available over the counter. |

|

Cervical cap |

A small silicone or rubber cup that is inserted into the vagina to cover the cervix before sex. Requires a prescription. |

|

Diaphragm |

A small silicone, rubber, or latex cup that is inserted into the vagina to cover the cervix before sex. Similar to the cervical cap, but larger and shaped differently. Requires a prescription. |

|

Ring |

A small, flexible ring placed in the vagina that releases hormones into the body to prevent pregnancy. Requires a prescription. |

|

Patch |

A small patch placed on the skin that releases hormones into the body to prevent pregnancy. Requires a prescription. |

|

Oral contraceptives |

Pills that contain hormones to prevent pregnancy. Sometimes prescribed for reasons other than contraception, such as to relieve symptoms related to menstrual flow or to control acne. May require a prescription or may be available over the counter. |

|

Injection |

An injection of a hormonal medication to prevent pregnancy. Effective for up to 3 months. Requires a prescription. |

|

Implant |

A small, thin, flexible plastic rod placed under the skin of the upper arm by a health care provider that releases a hormone to prevent pregnancy. Effective for up to 3 years. Requires a prescription. |

|

Intrauterine device (IUD) |

A small plastic T-shaped device inserted into the uterus by a health care provider to prevent pregnancy. Hormonal IUDs prevent pregnancy partially by suppressing the release of an egg, and partially by making it harder for sperm to swim. Copper IUDs prevent pregnancy by interfering with the movement of sperm, making it difficult for them to reach an egg. Effective for up to 3 to 10 years depending on the specific device. Requires a prescription. |

Source: GAO analysis of information from the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, Mayo Clinic, and Cleveland Clinic. | GAO‑25‑107151

· Emergency contraceptives. Emergency contraceptives are used to reduce the chance of pregnancy after unprotected sex, including due to the failure of other contraceptive methods. Over-the-counter emergency contraceptive pills are available and can prevent pregnancy if taken within 72 hours of unprotected sex.[10] Prescription emergency contraceptive pills are also available and can prevent pregnancy if taken within 120 hours of unprotected sex.[11] Additionally, copper intrauterine devices (IUD) can function as an emergency contraceptive.

· Medication abortion and procedural abortion. Abortion is a medical procedure to end a pregnancy. Medication abortion is the use of medication—mifepristone and misoprostol—to end a pregnancy. Procedural abortion is the removal of the fetus and placenta from the uterus to end a pregnancy.[12]

College Student Health Centers

Student health centers vary in numerous ways, such as the health care they offer, the types of providers on staff, and sources of funding, among other things. For example, some offer basic first aid and health education, whereas others provide robust primary care—including sexual and reproductive health care—as well as specialty care and pharmacy services. In addition, according to ACHA, student health centers are commonly funded through any combination of student health fees, funding from the college’s general budget, health insurance reimbursement, grants, or other financial support.[13]

There is no current estimate of how many colleges have a student health center, nor of how many provide sexual and reproductive health care on campus. One prior study, however, estimated that from 2014 to 2015, about 71 percent of colleges had a student health center, including about 85 percent of 4-year colleges and 41 percent of 2-year colleges.[14] That study further estimated that about 96 percent of colleges with a student health center offered health education; 73 percent offered diagnosis and treatment of STIs; 65 percent offered contraception; and 51 percent offered emergency contraceptives. The study found that these sexual and reproductive health care options were more commonly available at 4-year colleges with student health centers than at 2-year colleges. Additionally, the study estimated that most colleges had a mechanism for referring students to off-campus providers for sexual and reproductive health care, and most received some support from a local health department for STI testing.

Most Selected Colleges Offered a Variety of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Through Their Student Health Center

Selected Colleges Offered a Variety of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care; IUDs and Medication Abortion, Among Others, Were Less Commonly Available

The selected colleges offered a variety of sexual and reproductive health care through their student health center, including STI testing, contraceptives, and emergency contraceptives, among others. Officials at all 15 selected colleges said their college routinely made at least two types of sexual and reproductive health care products or services (menstrual products and pregnancy tests) available to students. Contraceptive implants, IUDs, and medication abortion were less commonly available, according to these officials.

Menstrual Products and Pregnancy Tests

Menstrual products and pregnancy tests were the only sexual and reproductive health care products or services routinely available to students through their student health center on campus at all 15 selected colleges, according to officials.[15] Similarly, our analysis of ACHA’s 2022 Sexual Health Services Survey data found that among the 184 participating 4-year colleges that offered sexual and reproductive health care through their student health center, nearly all (182) made pregnancy tests available to students.[16] For more information on our analysis of this survey, see appendix I.

· Menstrual products. Officials at all 15 selected colleges said menstrual products were available for free on campus. Furthermore, officials at 10 selected colleges said menstrual products were available both through their student health center and elsewhere on campus, such as restrooms or food pantries. Officials at one of these colleges also said their student health center offered both disposable and reusable menstrual products for students.

· Pregnancy tests. Officials at 10 of the 15 selected colleges said pregnancy tests were available for free through their student health center, whereas officials at the remaining five selected colleges said pregnancy tests were available at a cost. According to officials, most selected colleges did not offer pregnancy tests outside of their student health center. Officials at one college said pregnancy tests were also available to students at a cost through vending machines throughout campus.

STI Testing and Prevention

At most selected colleges (13 of 15), STI testing for chlamydia, gonorrhea, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, and syphilis was routinely available at the student health center, either for a cost or for free, according to college officials.[17] The other two selected colleges did not routinely offer all six of these STI tests.[18] Similarly, our analysis of ACHA’s 2022 survey data found that among the 184 participating colleges, most (177) offered STI testing at their student health center.

Officials at seven of the 15 selected colleges said their student health center did not charge students to collect test samples for STI tests; however, students’ out-of-pocket costs for STI testing varied because most student health centers relied on external laboratories to test the samples.[19] For example, officials from one college said their student health center collected STI test samples for free, but the samples were tested by an external laboratory, which billed the student or their insurance directly. In some cases, officials said laboratory testing was free for some STIs, but not for others. For example, according to officials at one college, a grant-funded program covered the laboratory testing costs for chlamydia and gonorrhea, so students were not charged for that testing. Similarly, an official at a different selected college said their state laboratory did not charge students for syphilis testing but charged for the other STIs.

Officials at most selected colleges said prescriptions for PrEP and PEP to prevent HIV were routinely available to students—specifically, eight selected colleges offered prescriptions for PrEP and nine offered prescriptions for PEP.[20] Officials at the college that offered PEP but not PrEP said their student health center would refer students to a local provider for PrEP, if needed, because their student health center did not have providers who were trained to offer it. Officials at another of the selected colleges said students could obtain a prescription for PrEP or PEP from their student health center for free but would have to fill the prescription at an off-campus pharmacy.[21] Similarly, our analysis of the ACHA’s 2022 survey data found that among the 184 participating colleges, most offered PrEP (119) or PEP (95) through their student health centers.

Contraceptives and Emergency Contraceptives

Officials at most selected colleges said various contraceptives were routinely available to students through their student health center, though some types of contraceptives were less commonly available (see fig. 1). Additionally, our analysis of ACHA’s 2022 survey data similarly found contraceptives were reported as being available at 171 of 184 participating 4-year colleges that offered any sexual and reproductive health care through their student health center.

Figure 1: Selected Contraceptives and Emergency

Contraceptives Routinely Available at 15 Selected Colleges’ Student Health

Centers

Notes: Routine availability refers to the general availability of the product or service when the college’s student health center is open. Our counts include selected colleges that provided prescriptions for these products, if applicable, and those that provided them directly from the student health center.

Male condoms were among the most commonly available contraceptives at the 15 selected colleges, according to officials at those colleges. Officials at all 12 of the selected colleges that made male condoms routinely available said students could obtain them for free at their student health center.[22] Female condoms were less commonly available and were offered at 10 of the 15 selected colleges, according to college officials.[23] Officials at most selected colleges said condoms were also routinely available at other locations on campus, such as restrooms, dormitories, or other locations across campus where nonresidential students may congregate. A health educator at one selected college said students could request any of a variety of condoms through their student health center’s website, including condoms in different sizes or made from different materials, among other options. Officials at another selected college said resident advisors on campus could request condoms from their student health center, which would then deliver them to the dormitories.

Oral contraceptives were also among the most commonly available contraceptives, according to officials at the 15 selected colleges. Officials at 12 selected colleges said their student health center routinely offered prescriptions for oral contraceptives.[24] According to the officials, providers at most of these 12 selected colleges could prescribe oral contraceptives to students for free, but some of the officials said picking up the prescribed medication from a commercial pharmacy could incur a cost. Officials at one of these colleges said the cost to pick up oral contraceptives from the pharmacy would depend on the student’s health insurance coverage.[25] Among the three colleges that did not routinely offer oral contraceptives, two did not routinely offer most forms of contraception to students, according to college officials. Officials from the third college said oral contraceptives were only available periodically when an external provider visited campus, but the external provider could distribute a 6-month supply to requesting students at each visit.

According to college officials, prescriptions for diaphragms, contraceptive implants, and IUDs were not commonly available among the 15 selected colleges. These prescriptions were available at four, two, and two colleges, respectively. Officials at some selected colleges said their student health center did not prescribe diaphragms because students did not request them, and officials at two of these colleges said they also did not offer contraceptive implants and IUDs due to low student demand. Officials at another selected college said providers at their student health center did not prescribe IUDs because they did not have the equipment needed to administer them. Further, according to ACHA’s 2022 survey, fewer than half of the 184 participating 4-year colleges whose student health center offered sexual and reproductive health care prescribed diaphragms (35) or administered contraceptive implants (73) or IUDs (58). However, a majority of the 97 participating 4-year colleges with an enrollment of at least 10,000 students offered administration of both contraceptive implants (62) and IUDs (54).

Officials at 10 of the 15 selected colleges said prescriptions for emergency contraceptive pills were routinely available to students at their student health center.[26] Furthermore, officials at some selected colleges said emergency contraceptive pills were also offered without a prescription or were available outside of the student health center. For example, officials at one college said emergency contraceptive pills could also be obtained without a prescription from vending machines throughout campus. Officials at another of these colleges said their student health center could prescribe emergency contraceptive pills to students whose health insurance covered them; otherwise, student health centers directed students off-campus to where they could purchase them over the counter.

Medication Abortion and Procedural Abortion

Medication abortion was available at one of the 15 selected colleges, and procedural abortion was not available at any of the selected colleges, according to officials.[27] Officials at the one selected college said medication abortion was available for free to students who were covered by the college’s student health insurance plan, and at a cost to those who were not or who did not want it to be billed to their student health insurance. Officials at eight selected colleges said their student health center could refer students to external providers for medication abortion or procedural abortion.[28] Our analysis of ACHA’s 2022 survey data similarly found that few of the participating 4-year colleges that offered sexual and reproductive health care through their student health center offered medication abortion (15 of 184) or procedural abortion (5 of 184).[29]

Reported Factors That Affected Availability of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care on Campus Included Costs, State Law Interpretation, and Religious Affiliation

The availability of most sexual and reproductive health care varied among selected colleges due to several factors, according to officials. Specifically, college officials said costs, state law interpretation, political sensitivities, and religious affiliation influenced the sexual and reproductive health care offered on campus.

Costs

Officials at 12 selected colleges indicated that the cost of sexual and reproductive health care relative to their student health center funding influenced the health care these colleges offered.[30]

Officials at six of these colleges expressly cited the cost of providing products or services as influencing their decisions to offer certain types of care. For example, officials at one selected college said IUDs were too expensive for their student health center to keep in stock.

Officials at nine selected colleges said their colleges relied in part on donations of sexual and reproductive health care products from state and local governments, private organizations, or others to make them available to students. For example, officials at four selected colleges said the menstrual products offered to students were donated to their college, mainly from local sources. Officials at another selected college said their student health center’s staff applied for donations of sexual and reproductive health care products to distribute for free, such as donations of emergency contraceptive pills they received from a private organization. According to officials at this selected college, those donations helped their student health center stretch its budget further by reducing purchases it would otherwise need to make.

Officials at six colleges said they relied on external providers or funding from state or local governments or grants to provide sexual and reproductive health care to students on campus. For example, officials at one college said they asked a local nonprofit clinic to provide various sexual and reproductive health care to students on campus. Officials at another college said grant funding enabled their student health center to offer free gonorrhea and chlamydia testing—including both the sample collection and laboratory test—to students at its monthly STI testing event. Officials from this college said their student health center would not have been able to offer those tests for free each month without the grant funding.

Colleges’ Interpretation of State Laws

Officials at four selected colleges said their colleges’ interpretation of state law influenced whether they offered abortion services.[31] For example, officials at one college said they did not provide medication abortion on campus because they interpreted a state law to prohibit nurse practitioners—the only clinical staff generally available at their student health center—from providing abortion services without a physician. In addition, officials at another selected college said they interpreted their state law to criminalize the provision of abortion services outside of very specific conditions.

Officials at the selected college that offered medication abortion on campus said a state law required public 4-year colleges in the state to provide medication abortion through their student health center.

Political Sensitivities

Officials at four selected colleges said political sensitivities influenced the sexual and reproductive health care available on campus. For example, officials at one college said their student health center did not offer referrals to off-campus providers for abortion services due to political sensitivities around abortion within their state, and particularly within the state legislature. Officials at another selected college said their college’s administration denied students’ request for medication abortion at their student health center due to the risk of political repercussions that could threaten the college’s state funding. According to representatives from one of the professional organizations we interviewed, the preferences of donors and the local population can also affect the sexual and reproductive health care offered at colleges.

Religious Affiliation

Officials at each of the three selected religiously affiliated colleges said their college’s religious affiliation influenced the sexual and reproductive health care available on campus. These officials explained their colleges did not offer sexual and reproductive health care that the affiliated religious group believed may promote extramarital sex.[32] For example, these officials said condoms were not offered on campus; however, officials at one of the three colleges said their student health center could prescribe oral contraceptives for reasons other than contraception.[33] Although the three religiously affiliated colleges we selected did not offer a wide range of contraceptive options, some religiously affiliated colleges might offer them. For example, our analysis of ACHA’s 2022 survey data found that 25 participating 4-year colleges with religious affiliations offered contraception. For more information, see appendix I.

Officials from Selected Colleges Said Students Faced Challenges Seeking Sexual and Reproductive Health Care on Campus, Which Colleges Took Actions to Address

Officials from Selected Colleges Identified Unfamiliarity, Misinformation, and Privacy as Some Challenges Students Faced

Officials at the selected colleges said that unfamiliarity, limited awareness of on-campus availability, misinformation, privacy concerns, stigmatization, appointment scheduling and wait times, and costs were challenges some students faced in seeking sexual and reproductive health care on campus (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Challenges Students Faced Seeking Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Cited Among 15 Selected Colleges

Unfamiliarity

Officials at 14 of the 15 selected colleges said unfamiliarity with sexual and reproductive health care was a challenge for some students. For example, officials at one college said students commonly expressed unfamiliarity with options for prescription contraceptives other than oral contraceptives and IUDs. Officials at another college said students were generally unfamiliar with PrEP and PEP for HIV prevention. Officials at eight colleges attributed some students’ unfamiliarity with sexual and reproductive health care to receiving little to no sex education prior to coming to college. Representatives we interviewed from one professional organization explained that K-12 schools in some states did not offer robust sex education, so colleges may need to provide that sex education to certain students.

Limited Awareness of On-Campus Availability

Officials at 11 of the 15 colleges said some students had limited awareness of what sexual and reproductive health care was available on campus, despite efforts to advertise availability. For example, officials at one college said that their college continually advertised sexual and reproductive health care availability as new students arrived each year. Officials at another college, however, explained that students often did not pay attention to what was available until they needed it. Officials at a third college said that even though their college took steps to educate students on sexual and reproductive health care, some new students needed time to become familiar with what was available on campus and where to seek out these services or products.

In some cases, officials at selected colleges said they intentionally limited advertisement of sexual and reproductive health care because of political sensitivities or religious affiliation. For example, officials at one public college said their college limited its advertisement of sexual and reproductive health care available on campus to avoid generating controversy within the state. Similarly, officials at a private college explained that advertisement of sexual and reproductive health care was restricted to word of mouth due to the religious affiliation of the college. Those officials said some students may have been less aware of sexual and reproductive health care available on campus than if their college advertised more widely.

Misinformation

Officials at nine of the 15 selected colleges said misinformation about sexual and reproductive health care was a challenge for some students. Officials at five colleges said some students expressed reservations about using hormonal contraceptives, such as oral contraceptives, because they mistakenly believed hormonal contraceptives caused infertility. Officials at one of these colleges said some students mistakenly believed hormonal contraceptives prevented them from getting STIs. Officials and health educators at some colleges described additional misconceptions that some students held, such as that the HPV vaccine caused infertility; condoms were only needed to prevent pregnancy; heterosexual students did not get STIs and therefore did not need to get tested; and that multiple condoms should be used simultaneously. Representatives we spoke with at one of the professional organizations said misinformation about sexual and reproductive health care among students was increasingly common.

Privacy Concerns

Officials at 10 of the 15 selected colleges said some students expressed concerns about their privacy when seeking sexual and reproductive health care at their student health center, either related to physical space or potential disclosure of products or services received. Specifically, officials at six colleges said some students expressed privacy concerns related to the physical layout of their student health center, with officials at three of these colleges identifying concerns about discussions within exam rooms being overheard outside the room. Additionally, officials at eight colleges said that students expressed privacy concerns related to information about the sexual and reproductive health care they received potentially being disclosed to their parents via a health insurance explanation of benefits.[34] In some of these cases, for example, some students opted to pay cash rather than have their insurance billed if their parent was the primary policy holder.

Stigmatization

Officials at four of the 15 selected colleges said stigmatization of sexual and reproductive health care was a challenge for some students, which delayed or prevented them from seeking services, such as STI testing. For example, officials at one college explained that some lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning students on their campus delayed or declined to be tested for HIV due to the stigmatization of being diagnosed as HIV positive. Similarly, officials from another college said some students were reluctant to be tested for STIs because they believed that being tested for STIs reflected poorly on their character. Additionally, officials at another college said that some students felt embarrassed to make an appointment to get emergency contraceptive pills at the student health center. Representatives from one of the professional organizations we interviewed said reducing stigmatization of sexual and reproductive health care was important for improving students’ willingness to access such care.

Appointment Scheduling or Wait Times

Officials at two of the 15 selected colleges said appointment scheduling or wait times was a challenge for some students accessing sexual and reproductive health care. Officials at one college said their student health center did not have enough staff to meet demand for health care in general, including sexual and reproductive health care, whereas officials at the other college said their student health center was especially busy during certain times of day. Officials at the remaining 13 colleges said appointment scheduling or wait times was not a challenge and students were able to easily schedule appointments, such as online, or could generally be seen on a walk-in basis.

Cost

Officials at seven of the 15 colleges cited the cost of certain sexual and reproductive health care as a challenge for some students. Specifically, officials at two of the 15 colleges said cost posed a challenge for some students accessing sexual and reproductive health care provided on campus. For example, officials at one of these colleges said their student health center charged students for products and services on a fee-for-service basis, which could be difficult for some students to afford. Officials at the second college said some students struggled with the cost of care due to differences in their health insurance coverage—or for some students, lack thereof.[35] Officials at five additional colleges said some students expressed concerns about being able to afford the cost of external laboratory fees for STI tests, which were conducted off-campus and billed separately from on-campus sample collection.

Selected Colleges Took Various Actions to Address Challenges to Students Seeking Sexual and Reproductive Health Care on Campus

Officials at selected colleges described a variety of efforts their colleges took to address challenges, such as providing education about sexual and reproductive health care, minimizing the costs of care, referring students to low-cost off-campus providers, and implementing privacy-enhancing measures.

Provided Education

Officials at 14 of the 15 selected colleges said their college took a variety of actions to educate students about sexual and reproductive health care. These officials said educational efforts helped to address multiple challenges to students seeking sexual and reproductive health care, including unfamiliarity, limited awareness, misinformation, and stigmatization. The types of educational efforts included health education, educational events, and discussion of sexual and reproductive health during other types of medical appointments.

Health Educators

Officials at eight of the 15 selected colleges said they used health educators to help educate students about sexual and reproductive health care in a variety of ways, including assisting with educational events and engaging with students in person, over the phone, or through social media. For example, an official at one college said their health educators walked around campus to distribute snacks as well as sexual and reproductive health care informational materials and selected products, such as condoms and menstrual products. A health educator from that college said they brought up health topics with students they encountered, which sometimes included sexual and reproductive health care. Additionally, a health educator at another college said health educators worked shifts answering an informational hotline for students with questions about sexual and reproductive health care. Further, officials or health educators at four colleges said health educators posted information on social media to help spread information about sexual and reproductive health care.

Officials at three colleges said they used student health educators to spread information about sexual and reproductive health care because students were more likely to listen to and ask questions of their peers than student health center staff. In addition, officials at two of these colleges said health educators provided their student health center’s staff with useful feedback about the types of sexual and reproductive health care for which students needed or wanted greater access.

Educational Events

Officials at 12 of the 15 selected colleges said student health center staff, health educators, or external health care experts—such as local health department staff—held events on campus to provide education about sexual and reproductive health care. For example, officials at most selected colleges said students received information or informational materials during student orientation. Officials at nine colleges said student health center staff, health educators, or other staff also set up informational tables on a routine or special basis in areas students frequently passed through. To overcome student hesitation to approach the table and ask questions, health educators at four colleges said student health center staff or health educators sometimes used novelties or games to incentivize students to talk about sexual and reproductive health care. For example, a health educator at one college said health educators distributed condom flowers (i.e., handmade flowers with condoms as the flower petals) to attract students’ attention (see fig. 3). This health educator said the novelty of the flowers made it a popular incentive for students to engage with the health educators, which provided an opportunity to educate students about sexual and reproductive health care.

A health educator at another college said the informational tables they set up for special events included cookies shaped as uteruses or condoms. According to the health educator, the novelty of the cookies incentivized students to approach the table, which then provided an opportunity for health educators to discuss sexual and reproductive health care or share an educational fact sheet. Furthermore, health educators at two selected colleges said hosting trivia games with students at the informational tables incentivized students to talk about sexual and reproductive health care.

Officials at three colleges said they periodically organized informational panels at which student health center staff or external health care experts presented information about sexual and reproductive health care and answered students’ questions. Health educators at two colleges said one popular format enabled students to anonymously submit questions for the panel to answer. Submitting questions anonymously, in particular, helped students avoid potential embarrassment from publicly asking questions about sexual and reproductive health care, according to officials at one of these colleges.

Medical Appointments

Officials at five selected colleges said student health center staff routinely discussed sexual and reproductive health care with students during medical appointments. Officials at one college said their student health center scheduled medical appointments to be longer than they would be elsewhere to provide extra time for staff to discuss sexual and reproductive health when needed. Officials at that college said their student health center’s staff commonly spent time discussing contraceptive options with students and explaining the importance of STI testing even for asymptomatic students. Additionally, officials from another college said that some students came into their student health center to request an IUD because it was one of the few types of contraception they were aware of. Those officials stated that their student health center’s staff provided education by discussing a broader set of contraceptive options to help those students determine their best contraceptive option.

Minimized or Helped Cover Costs

Officials at most of the 15 selected colleges said their college took steps to minimize or help cover the costs of sexual and reproductive health care provided on campus. Officials at 10 colleges said some or all of the sexual and reproductive health care provided through their student health center was available to students for free because it was funded through sources such as student health fees and college general funds. Additionally, as discussed earlier, officials at 11 colleges said they received funding or donations of certain products—such as condoms and menstrual products—from external organizations, which helped keep some of the sexual and reproductive health care on campus free to students.[36]

Officials at six colleges said external providers visited campus to provide sexual and reproductive health care to students for little to no cost. For example, officials at one college said a local nonprofit clinic visited campus each month to provide free sexual and reproductive health care to students, such as STI testing, IUDs, and oral contraceptives. Officials at another college said staff from the county health department provided sexual and reproductive health care on campus two days per week for potentially little to no cost based on a sliding fee scale.[37] In addition, officials at three colleges said their college could potentially use emergency funds to pay for STI testing or other sexual and reproductive health care that a student needed but could not afford.

Referred Students to Off-Campus, In-Network or Low-Cost Providers

To address cost and privacy challenges, officials at all of the 15 selected colleges said student health center staff could refer students to external providers who were either in the student’s health insurance plan network or who could provide referred services for little or no cost. For example, officials at 10 colleges said some students expressed concerns specifically about the cost or potential disclosure of a STI test because these colleges sent STI test samples to external laboratories for processing. Officials at some colleges said they had options to alleviate these concerns, including referrals to external providers, such as the local health department, that could provide STI testing for little or no cost without billing insurance.[38]

Furthermore, officials at five colleges said transportation was available to referred external providers, ensuring that students could more readily access them. For example, officials at two colleges said their colleges had ride share vouchers students could use for transportation to off-campus referrals, if needed. Officials at another college said their campus security was available to drive students to and from referred providers to help address transportation challenges.

Implemented Privacy-Enhancing Measures at the Student Health Center

Officials at four colleges said their student health center took steps to enhance the privacy of its physical layout to address challenges to students seeking sexual and reproductive health care. For example, officials at two of these colleges said that, in response to student concerns, their student health center installed acoustic panels or white noise machines to prevent other patients from hearing discussions in exam rooms.[39] Additionally, officials at one college said their student health center sent students notifications via text message when a provider was ready to see them so their names would not be announced in the waiting room.

Most Selected Colleges Did Not Offer Abortion Services Before or After the Start of the 2021-2022 Academic Year, but Availability and Demand Increased for Other Care

Most Selected Colleges Said Abortion Was Not Available on Campus Before or After the Start of the 2021-2022 Academic Year, but Student Uncertainty About Off-Campus Options Increased

Officials at 14 of the 15 selected colleges said medication abortion was not available on campus prior to the start of the 2021-2022 academic year and continued to be unavailable since then.[40] According to officials at the one selected college that offered medication abortion, the student health center began offering medication abortion in February 2021, prior to the start of the 2021-2022 academic year and in response to a state law requiring public 4-year colleges in the state to provide medication abortion through their student health center. Officials at one of the other colleges said they did not expect to offer medication abortion in the future due to a state law they interpreted to criminalize the provision of abortion services outside of very specific conditions.[41]

Officials at one of the 15 selected colleges said their student health center discontinued offering off-campus referrals for abortion services after the start of the 2021-2022 academic year. Officials at that college said following the Dobbs decision, several bills were proposed in the state legislature that resulted in their student health center deciding to cease referring students to providers for abortion services. Officials at that college said that if a student was interested in obtaining medication abortion or procedural abortion, their student health center would informally provide them with contact information for providers within the state and in nearby states who offered the service of interest, along with any eligibility limitations (e.g., only within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy). However, the student health center would not be able to help the student schedule an appointment or share medical notes with the off-campus provider as they would with other medical referrals.

Officials at six selected colleges said some students expressed uncertainty about their ability to access abortion services following the Dobbs decision in June 2022. For example, officials at one selected college said students asked student health center staff more questions about the extent to which off-campus abortion services remained available. Officials at another of these colleges said students had concerns about losing access to medication abortion in general and wanted their student health center to provide that service, though the college decided not to do so.[42] Further, officials at a third college said students stopped visiting their student health center for pregnancy testing for several months following the Dobbs decision. In contrast, officials at five selected colleges said they did not identify changes in the nature of interactions with students following the Dobbs decision.[43] For example, officials at one of these colleges said students likely did not express concerns about losing access to reproductive health care because the state’s laws protected reproductive access, including access to abortion, and students were not concerned that this would change.

According to officials at three selected colleges, student health center providers began sharing less information with students about abortion services, and students’ local options for external providers of abortion services decreased since the start of the 2021-2022 academic year. For example, officials at one selected college explained that state laws, enacted following the Dobbs decision, prevented their student health center providers from providing pregnant students with information about abortion services. Officials at the same college further said students began asking their student health center’s providers hypothetical questions about their options for carrying a pregnancy to term or terminating it prior to receiving pregnancy test results. Additionally, officials at two selected colleges said students’ options for abortion services in the local community decreased following the Dobbs decision. For example, officials at one selected college said multiple local abortion providers closed following the Dobbs decision. Officials at another college said the local hospital closed its labor and delivery department after a state law limiting abortion access went into effect and several obstetrician gynecologists left the state.

Officials at Most Selected Colleges Said Availability and Demand Increased for Other Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Since the Start of the 2021-2022 Academic Year

Officials at nine of the 15 selected colleges said their colleges made more types of contraception and emergency contraception available since the start of the 2021-2022 academic year, largely in response to increased student demand. For example, officials at one college said they began offering emergency contraception after the start of the 2021-2022 academic year partly in response to student demand and partly because they learned that peer colleges were also offering emergency contraception. Officials at another college said they were influenced by student feedback to begin offering pregnancy testing and male condoms after the start of the 2021-2022 academic year. However, not all changes were in response to increased student demand, according to college officials. For example, officials at one college said they began offering generic emergency contraceptive pills through their student health center at a lower cost than a brand-name version available in their campus vending machines to make emergency contraception more affordable for students.

Additionally, according to officials, student demand prompted four selected colleges to take efforts to increase the availability of existing sexual and reproductive health care on their campuses. For example, officials from one selected college said they began bringing a nonprofit clinic to their campus for regular visits to provide lower-cost sexual and reproductive health care, such as STI testing, than their student health center could routinely offer. Officials at two additional colleges said they added dispensers for condoms on campus, increasing availability beyond their student health centers. Officials at the fourth college said they began offering emergency contraceptives in a specific common area on campus and began offering condoms in the recreation center, residential living (e.g., dormitories), libraries, and other locations.

Officials at 11 of the 15 selected colleges said student demand for on-campus STI testing, contraception, or other sexual and reproductive health care increased since the start of the 2021-2022 academic year. For example, officials at one college said their student health center distributed more male and female condoms and administered more HIV and pregnancy tests than they did prior to the start of the 2021-2022 academic year. Officials at another college similarly said they experienced an increase in students requesting contraceptives. Additionally, officials at a different college said their student health center received phone calls from parents requesting contraception for their children enrolled at the college, which had not occurred in earlier years.

Officials generally did not offer reasons why student demand for sexual and reproductive health care increased. However, officials at one selected college stated that the volume of students served at their student health center increased since the start of the 2021-2022 academic year as those colleges resumed in-person instruction following the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Officials from another college said their increase in student demand may have been in part due to the college’s increased efforts to spread awareness about the availability of sexual and reproductive health care on campus.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services for review and comment. Both departments provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional staff, the Secretary of Education, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact John E. Dicken at (202) 512-7114 or dickenj@gao.gov or Melissa Emrey-Arras at (202) 512-7215 or emreyarrasm@gao.gov. Contact points for Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Sincerely,

John E. Dicken

Director, Health Care

Melissa Emrey-Arras

Director, Education, Workforce, and Income Security

Appendix I: Analysis of American College Health Association’s 2022 Sexual Health Services Survey Data

The American College Health Association (ACHA) is an advocacy, research, and education organization that represents about 950 colleges and nearly 12,000 health care professionals who serve college campuses.[44] Every two years, ACHA surveys its member colleges about the sexual and reproductive health care offered on their campuses.[45] The results of the survey are intended to provide participating colleges with data for benchmarking their own services; however, the results of the survey are not generalizable.

We analyzed ACHA’s 2022 Sexual Health Services Survey data, which covered calendar year 2022 and represented the most recent data on sexual and reproductive health care available at the time of our review.[46] To assess the reliability of those data, we reviewed related documentation, interviewed ACHA representatives about the data, compared the data against published totals, and conducted checks for missing or erroneous data. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

A total of 207 colleges in the United States responded to the survey, 194 of which were 4-year colleges and 13 of which were 2-year colleges.[47] Because over 90 percent of the respondents were 4-year colleges, we limited our analyses to those colleges. Of the 194 4-year colleges that responded to the survey, 184 reported that their student health center provided sexual and reproductive health care, although some colleges declined to respond to certain questions. We refer to colleges that participated in the survey as “participating colleges.”

The 184 participating 4-year colleges that reported providing sexual and reproductive health care offered a variety of these types of care through their student health center. For example, nearly all of the 184 participating colleges offered pregnancy testing (182), sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing (177), and some type of contraception (171; see table 2). Most also offered both pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP, respectively) for HIV prevention, as well as human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, and cervical cancer screening.

Table 2: Counts of Participating 4-Year Colleges Offering Selected Sexual and Reproductive Health Care at Student Health Centers, by College Characteristic and Product or Service, Calendar Year 2022

|

College characteristic |

Product or service |

Available at student health center |

Not available at |

||

|

Overall (n = 184) |

Cervical cancer screening |

157 |

27 |

||

|

|

Sexually transmitted infection (STI) testinga |

177 |

7 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

182 |

2 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

171 |

13 |

||

|

|

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) |

119 |

65 |

||

|

|

HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) |

95 |

89 |

||

|

|

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination |

116 |

68 |

||

|

Sector |

|

|

|

||

|

Public (n = 112) |

Cervical cancer screening |

105 |

7 |

||

|

|

STI testinga |

111 |

1 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

111 |

1 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

109 |

3 |

||

|

|

HIV PrEP |

77 |

35 |

||

|

|

HIV PEP |

59 |

53 |

||

|

|

HPV vaccination |

72 |

40 |

||

|

Privateb (n = 72) |

Cervical cancer screening |

52 |

20 |

||

|

|

STI testinga |

66 |

6 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

71 |

1 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

62 |

10 |

||

|

|

HIV PrEP |

42 |

30 |

||

|

|

HIV PEP |

36 |

36 |

||

|

|

HPV vaccination |

44 |

28 |

||

|

Affiliation |

|

|

|

||

|

Secular (n = 150) |

Cervical cancer screening |

135 |

15 |

||

|

|

STI testinga |

146 |

4 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

148 |

2 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

146 |

4 |

||

|

|

HIV PrEP |

103 |

47 |

||

|

|

HIV PEP |

81 |

69 |

||

|

|

HPV vaccination |

100 |

50 |

||

|

Religious (n = 34) |

Cervical cancer screening |

22 |

12 |

||

|

|

STI testinga |

31 |

3 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

34 |

0 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

25 |

9 |

||

|

|

HIV PrEP |

16 |

18 |

||

|

|

HIV PEP |

14 |

20 |

||

|

|

HPV vaccination |

16 |

18 |

||

|

Urban or rural |

|

|

|

||

|

Urban (n = 152) |

Cervical cancer screening |

135 |

17 |

||

|

|

STI testinga |

148 |

4 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

151 |

1 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

141 |

11 |

||

|

|

HIV PrEP |

101 |

51 |

||

|

|

HIV PEP |

82 |

70 |

||

|

|

HPV vaccination |

103 |

49 |

||

|

Rural (n = 32) |

Cervical cancer screening |

22 |

10 |

||

|

|

STI testinga |

29 |

3 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

31 |

1 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

30 |

2 |

||

|

|

HIV PrEP |

18 |

14 |

||

|

|

HIV PEP |

13 |

19 |

||

|

|

HPV vaccination |

13 |

19 |

||

|

Student enrollmentc |

|

|

|

||

|

Less than 2,500 (n = 27) |

Cervical cancer screening |

12 |

15 |

||

|

|

STI testinga |

21 |

6 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

26 |

1 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

23 |

4 |

||

|

|

HIV PrEP |

9 |

18 |

||

|

|

HIV PEP |

7 |

20 |

||

|

|

HPV vaccination |

9 |

18 |

||

|

2,500 to 4,999 (n = 21) |

Cervical cancer screening |

16 |

5 |

||

|

|

STI testinga |

21 |

0 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

21 |

0 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

18 |

3 |

||

|

|

HIV PrEP |

10 |

11 |

||

|

|

HIV PEP |

7 |

14 |

||

|

|

HPV vaccination |

12 |

9 |

||

|

5,000 to 9,999 (n = 35) |

Cervical cancer screening |

31 |

4 |

||

|

|

STI testinga |

35 |

0 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

35 |

0 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

33 |

2 |

||

|

|

HIV PrEP |

19 |

16 |

||

|

|

HIV PEP |

15 |

20 |

||

|

|

HPV vaccination |

14 |

21 |

||

|

10,000 or more (n = 101) |

Cervical cancer screening |

98 |

3 |

||

|

|

STI testinga |

100 |

1 |

||

|

|

Pregnancy testing |

100 |

1 |

||

|

|

Contraception |

97 |

4 |

||

|

|

HIV PrEP |

81 |

20 |

||

|

|

HIV PEP |

66 |

35 |

||

|

|

HPV vaccination |

81 |

20 |

||

Source: GAO analysis of data from the American College Health Association’s (ACHA) 2022 Sexual Health Services Survey. | GAO‑25‑107151

Notes: For this table, we analyzed the 184 4-year colleges in the United States that responded to ACHA’s 2022 Sexual Health Services Survey and that reported that their student health center offered sexual and reproductive health care.

aThe survey question did not ask respondents to specify which STI tests the college offered.

bAccording to ACHA representatives, the private 4-year colleges that participated in the survey were all nonprofit.

cStudent enrollment reflects total 12-month enrollment counts for the 2021-2022 academic year.

Among the participating 4-year colleges, 177 generally offered STI testing; however, coverage of chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HIV tests varied. For example, 166 colleges offered chlamydia testing through their student health center. Among those, the cost of the test was fully covered by a mandatory student health fee or other fund at 47 colleges, whereas the cost was fully out of pocket for students at 25 colleges (see table 3). Chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HIV tests offered through student health centers were fully or partially covered at most of the participating colleges.

Table 3: Counts of Participating 4-Year Colleges Offering Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) Testing at Student Health Centers, by Payment Source, Calendar Year 2022

|

|

STI test |

|||

|

Payment source |

Chlamydia |

Gonorrhea |

Syphilis |

HIV |

|

Fully covered by a mandatory student health fee |

30 |

28 |

24 |

28 |

|

Fully covered by a fund other than a mandatory student health fee |

17 |

18 |

13 |

16 |

|

Fully or partially covered by a college-sponsored student health insurance plan |

30 |

30 |

33 |

30 |

|

Fully or partially covered by students’ health insurance |

64 |

65 |

66 |

64 |

|

Fully out of pocket for students |

25 |

24 |

26 |

24 |

|

Did not respond |

11 |

12 |

15 |

15 |

|

Total |

177 |

177 |

177 |

177 |

Source: GAO analysis of data from the American College Health Association’s (ACHA) 2022 Sexual Health Services Survey. | GAO‑25‑107151

Notes: For this table, we analyzed the 177 4-year colleges in the United States that responded to ACHA’s 2022 Sexual Health Services Survey and that reported that their student health center offered STI testing. Full coverage indicates that visits and screenings were covered with no cost sharing for students, whereas partial coverage indicates that students were responsible for cost sharing.

Seventy-six participating 4-year colleges reported that their student health center organized STI testing events in outreach settings on campus. ACHA representatives said such events are commonly held at residence halls, libraries, or student centers. Of those 76 colleges, 59 reported that community organizations or local health department staff helped with or exclusively conducted testing at those on-campus events (see table 4). Sixty-one of the 76 colleges organized STI testing events at least once per academic term, and 69 reported all tests offered at the events were free to students. Participating colleges reported that the specific STI tests offered at such events varied.

Table 4: Counts of Participating 4-Year Colleges Offering Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) Testing Events on Campus and Related Cost, Frequency, Staffing, and Types of Tests Offered, Calendar Year 2022

|

STI testing events |

Number of colleges |

|

Cost of tests during events |

|

|

All tests are free |

69 |

|

Some tests are free |

2 |

|

No tests are free |

5 |

|

Total |

76 |

|

Frequency of testing events |

|

|

Once per academic year |

15 |

|

Once per academic term (quarter or semester) |

33 |

|

Once per month during the academic year |

15 |

|

More than once per month during the academic year |

13 |

|

Total |

76 |

|

Staff responsible for testing |

|

|

Student health center |

17 |

|

Community organization or local health department |

37 |

|

Both student health center and community organization or local health department |

22 |

|

Total |

76 |

|

Tests offered |

|

|

HIV only |

18 |

|

Chlamydia only |

1 |

|

Chlamydia and gonorrhea |

8 |

|

Syphilis and HIV |

3 |

|

Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HIV |

18 |

|

Chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HIV |

28 |

|

Total |

76 |

Source: GAO analysis of data from the American College Health Association’s (ACHA) 2022 Sexual Health Services Survey. | GAO‑25‑107151

Notes: For this table, we analyzed the 76 4-year colleges in the United States that responded to ACHA’s 2022 Sexual Health Services Survey and that reported that their student health center organized STI testing events in outreach settings across campus.

Although most of the participating 4-year colleges offered one or more self-administered contraceptives (cervical cap, patch, ring, diaphragm, or oral contraceptive pills) through their student health center, some were more commonly offered than others. For example, oral contraceptives were both prescribed and dispensed by 100 of the 171 participating 4-year colleges that offered contraceptives through their student health center, and another 67 participating colleges prescribed but did not dispense them on site (see table 5).[48] In addition, most of the 171 participating colleges prescribed oral contraceptives regardless of the college characteristics we examined. In contrast, cervical caps were uncommon, with 162 of the 171 participating colleges reporting that they neither prescribed nor dispensed them.

Table 5: Counts of Participating 4-Year Colleges Prescribing or Dispensing Self-Administered Contraceptives at Student Health Centers, by College Characteristic and Product, Calendar Year 2022

|

|

|

Service provided on campus |

||

|

College characteristic |

Product |

Prescribed and dispensed |

Prescribed but not dispensed |

Neither prescribed nor dispensed |

|

Overall (n = 171) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

9 |

162 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

44 |

87 |

40 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

52 |

81 |

38 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

15 |

20 |

136 |

|

|

Oral contraceptivesa |

100 |

67 |

4 |

|

Sector |

|

|

|

|

|

Public (n = 109) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

7 |

102 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

38 |

56 |

15 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

44 |

51 |

14 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

14 |

13 |

82 |

|

|

Oral contraceptivesa |

72 |

36 |

1 |

|

Privateb (n = 62) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

2 |

60 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

6 |

31 |

25 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

8 |

30 |

24 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

1 |

7 |

54 |

|

|

Oral contraceptivesa |

28 |

31 |

3 |

|

Affiliation |

|

|

|

|

|

Secular (n = 146) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

8 |

138 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

41 |

77 |

28 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

48 |

72 |

26 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

15 |

18 |

113 |

|

|

Oral contraceptivesa |

87 |

56 |

3 |

|

Religious (n = 25) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

1 |

24 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

3 |

10 |

12 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

4 |

9 |

12 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

0 |

2 |

23 |

|

|

Oral contraceptivesa |

13 |

11 |

1 |

|

Urban or rural |

|

|

|

|

|

Urban (n = 141) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

8 |

133 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

40 |

70 |

31 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

47 |

66 |

28 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

15 |

17 |

109 |

|

|

Oral contraceptivesa |

87 |

52 |

2 |

|

Rural (n = 30) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

1 |

29 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

4 |

17 |

9 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

5 |

15 |

10 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

0 |

3 |

27 |

|

|

Oral contraceptivesa |

13 |

15 |

2 |

|

Student enrollmentc |

|

|

|

|

|

Less than 2,500 (n = 23) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

1 |

22 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

0 |

7 |

16 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

0 |

8 |

15 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

0 |

2 |

21 |

|

|

Oral contraceptivesa |

7 |

13 |

3 |

|

2,500 to 4,999 (n = 18) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

1 |

17 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

0 |

9 |

9 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

0 |

11 |

7 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

0 |

1 |

17 |

|

|

Oral contraceptivesa |

8 |

10 |

0 |

|

5,000 to 9,999 (n = 33) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

1 |

32 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

2 |

23 |

8 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

4 |

17 |

12 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

0 |

3 |

30 |

|

|

Oral contraceptivesa |

16 |

17 |

0 |

|

10,000 or more (n = 97) |

Cervical cap |

0 |

6 |

91 |

|

|

Contraceptive patch |

42 |

48 |

7 |

|

|

Contraceptive ring |

48 |

45 |

4 |

|

|

Diaphragm |

15 |

14 |

68 |

|

|