DEFENSE WORKFORCE

Efforts to Address Challenges in Recruiting and Retaining Federal Wage System Employees

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Yvonne D. Jones at jonesy@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107152, a report to congressional committees

Efforts to Address Challenges in Recruiting and Retaining Federal Wage System Employees

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD relies on its blue-collar workforce to perform and support a variety of work. GAO’s prior work found that DOD has faced long-standing workforce challenges in competing with the private sector and other federal agencies for skilled workers.

The Joint Explanatory Statement for the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for GAO to report on the FWS. This report examines (1) challenges in administering the FWS that may affect recruitment and retention at selected DOD services and installations, and (2) the extent to which selected DOD services and installations have taken actions to address FWS recruitment and retention challenges.

GAO selected the services and installations based on factors, such as the size of the FWS workforce, the presence of different types of FWS employees, and geographic dispersion. GAO analyzed DOD data from fiscal years 2018 through 2024 to identify workforce trends; analyzed agency documents; and interviewed agency and union officials. GAO conducted site visits to Edwards Air Force Base, Tobyhanna Army Depot, and Norfolk Naval Shipyard. GAO compared the services’ and installations’ use of goals and targets for the FWS workforce to GAO’s performance management practices.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that the Secretary of the Air Force ensure that Edwards Air Force Base develops and documents staffing targets for its FWS workforce. DOD and Air Force agreed with the recommendation.

What GAO Found

The underlying principles of the Federal Wage System (FWS) are to set hourly pay rates for federal blue-collar workers in line with local prevailing (or market) rates and provide equal pay for substantially equal work. However, these principles have not been met because of several challenges with the FWS. These challenges include:

· effect of the pay adjustment cap on final FWS wage rates and wage schedules;

· inexact match between local wage survey job descriptions used to compare federal FWS and private sector occupations; and

· amount of private sector wage data collected for local wage surveys.

In addition, officials from most selected Department of Defense (DOD) services—Air Force, Army, and Navy—and installations—Edwards Air Force Base, Tobyhanna Army Depot, and Norfolk Naval Shipyard—reported challenges with recruiting and retaining FWS employees, such as competition with the private sector for skilled labor and the lengthy federal onboarding process.

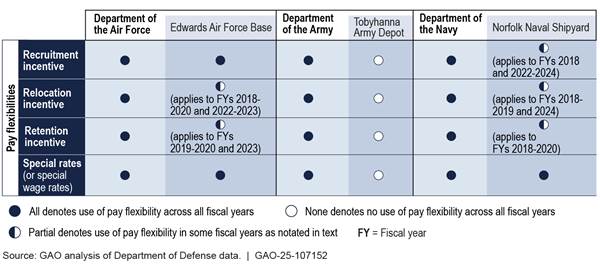

All selected DOD services and installations took actions to address recruitment and retention challenges, including the use of various pay flexibilities, for certain FWS employees.

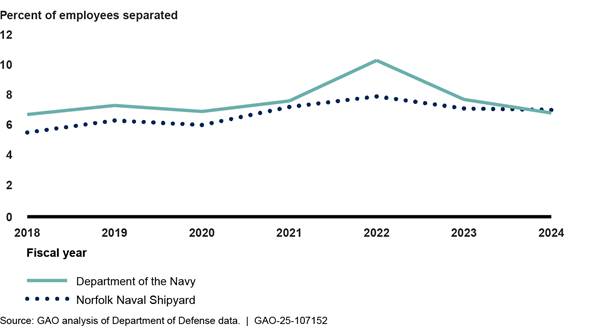

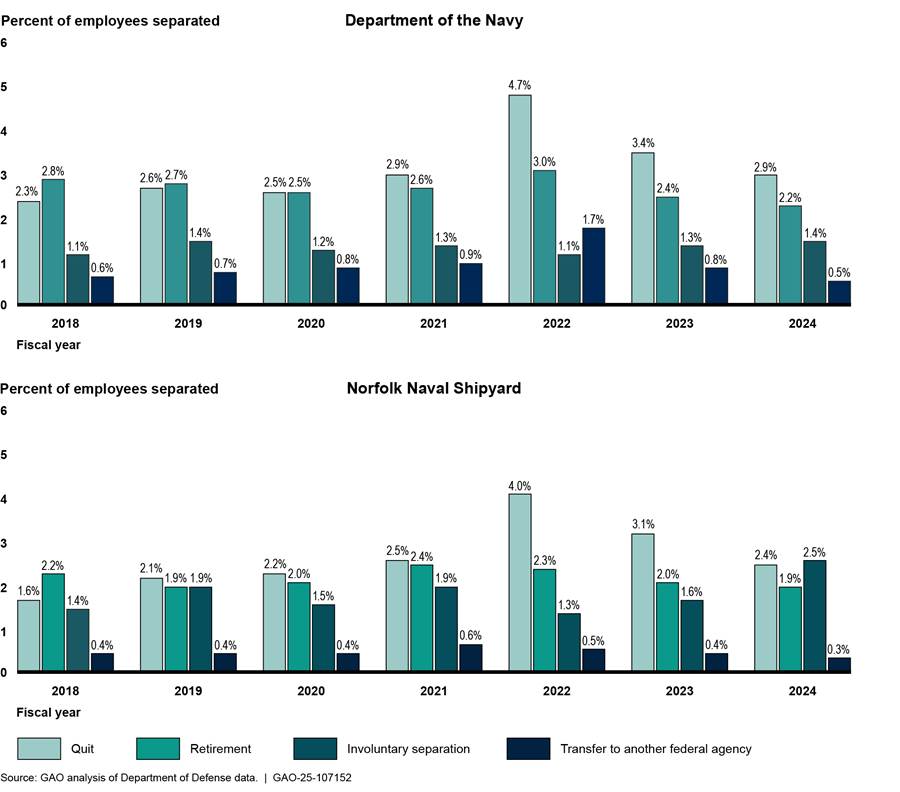

Note: For more details, see figure 5 in GAO-25-107152.

GAO found the selected installations have or are developing goals for the FWS workforce. Norfolk Naval Shipyard and Tobyhanna Army Depot used measurable targets for determining their FWS workload needs. However, Edwards Air Force Base did not have measurable targets for recruiting and retaining its FWS workforce. Establishing measurable targets will help Edwards Air Force Base better assess the results of specific actions and strategies taken to improve FWS recruitment and retention and effectively manage its workforce to meet its mission.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

AF |

appropriated fund |

|

CNIC |

Commander, Navy Installations Command |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

Edwards |

Edwards Air Force Base |

|

FPRAC |

Federal Prevailing Rate Advisory Committee |

|

FWS |

Federal Wage System |

|

GS |

General Schedule |

|

NAF |

nonappropriated fund |

|

NEXCOM |

Navy Exchange Service Command |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

Tobyhanna |

Tobyhanna Army Depot |

|

WG |

wage grade |

|

WL |

wage leader |

|

WS |

wage supervisor |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 3, 2025

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Prevailing Rate Systems Act of 1972 was enacted to establish the Federal Wage System (FWS) for federal blue-collar employees who work in trade, craft, and labor.[1] As the largest employer of federal blue-collar employees under the FWS, the Department of Defense (DOD) relies on its FWS appropriated fund (AF) and nonappropriated fund (NAF) employees to perform and support a variety of work at Army depots, Air Force bases, and Navy shipyards.[2] For example, DOD’s FWS AF workforce maintains and repairs (1) systems for electronics and missile control, (2) air and space weapons systems, and (3) nuclear aircraft carriers and submarines. DOD’s FWS NAF workforce includes automobile mechanics and food service workers who work at facilities within DOD installations. Our prior work on DOD’s depot workforce has found that DOD has faced long-standing workforce challenges when it comes to competing with the private sector and other federal agencies for skilled workers.[3]

The underlying principles of the FWS are to set hourly pay rates for federal blue-collar employees in line with local prevailing (or market) rates and provide equal pay for substantially equal work. However, our prior work on the FWS found that legislation enacted subsequent to the Prevailing Rate Systems Act of 1972, primarily in annual appropriations laws, has placed limits on the pay adjustments granted to certain FWS employees.[4] According to Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and DOD officials, these limits result in deviations from market rates. This is one of several factors that have contributed to DOD’s growing challenges of recruiting and retaining its FWS workforce.

The Joint Explanatory Statement for the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for us to issue a report on the parity between the FWS and prevailing wage rates for employees who perform work at the U.S. Navy public shipyards and domestic naval bases with facilities to maintain or repair U.S. Navy ships or submarines.[5] In addition to the Department of the Navy, we expanded our scope for this review to include the Departments of the Air Force and Army because these services employed the largest number of FWS employees within DOD as of fiscal year 2023 and have reported recruitment and retention issues for the FWS workforce.[6]

This report examines (1) challenges in administering the FWS that may affect recruitment and retention at selected DOD services and installations, and (2) the extent to which selected DOD services and installations have taken actions to address challenges in recruiting and retaining FWS employees.

For both objectives, we judgmentally selected three DOD installations—one each from Air Force, Army, and Navy—as illustrative cases. These three installations were Edwards Air Force Base in California (Edwards), Tobyhanna Army Depot in Pennsylvania (Tobyhanna), and Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Virginia.

We selected the installations based on the following criteria within and across the selected installations: (1) the total number of AF employees, (2) the presence of NAF employees, (3) geographic dispersion, (4) high and low costs of labor using the General Schedule (GS) locality pay area adjustment percentages as a proxy to determine proximity to higher and lower income areas, (5) variety of AF occupations, and (6) the use of selected pay flexibilities according to DOD data. We conducted site visits to each of the selected installations.

We interviewed agency officials and local union leadership that are also FWS employees at each of these installations to understand their perspectives on FWS challenges that may affect recruitment and retention, as well as actions taken to address such challenges. While interviews at selected services and installations provided illustrative examples of the recruitment and retention challenges FWS employees faced, our findings are not generalizable to other services or installations. Additionally, the employee perspectives we collected represent only the views of those who participated in our interviews and are not generalizable to other employees at the selected installation.

To address the first objective, we reviewed relevant federal legislation; OPM regulations; OPM memorandums and guidance, such as the AF and NAF operating manuals; OPM and DOD documentation; and our prior work on the FWS.[7] In addition, we interviewed agency officials from OPM, DOD, and selected DOD services to obtain perspectives on challenges in administering the FWS and how they may affect recruitment and retention of FWS employees. We also interviewed all the Federal Prevailing Rate Advisory Committee (FPRAC) members—representing both agency management and unions—who were on the committee as of April 2024. For our selected installations, we interviewed Local Wage Survey Committee members representing both agency management and unions, and DOD and local agency and union data collectors who conduct the AF and NAF wage surveys, as available.[8] Findings from our interviews with these officials represent the views of those who participated in our interviews and are not generalizable to other Local Wage Survey Committee members and data collectors.

To address the second objective, we reviewed OPM regulations; OPM guidance on human resources flexibilities and authorities; DOD guidance on hiring authorities; and OPM and DOD documentation. We reviewed guidance and documentation from selected DOD services, commands, and installations to understand their actions taken to address FWS recruitment and retention challenges and how they conduct workforce planning for the FWS AF and NAF workforces. We analyzed the selected services’ and installations’ use of workforce goals and targets to help manage the FWS AF workforce against our evidence-based policymaking practices on setting goals and targets for organizational performance.[9] We also analyzed how selected DOD NAF employers planned for and managed the FWS NAF workforce at the installation level in accordance with respective personnel policies and guidance.

We interviewed agency officials from the selected DOD services and commands and agency and local union officials at the selected DOD installations.[10] We asked about the status of workforce reductions and agency reorganizations since the change in administration in 2025. DOD officials were unable to share definitive information on any of these initiatives given they were in progress as of June 2025. However, they mentioned that there will be a negative effect on DOD’s ability to manage its wage program and meet its overall mission if workforce reductions are permanent.

We analyzed personnel data captured in DOD’s Defense Civilian Personnel Data System database. Specifically, we analyzed data from fiscal years 2018 through 2024—the most recent 7 years of data—to identify selected DOD services’ and installations’ use of direct hire authority and pay flexibilities to address FWS AF workforce challenges.[11] We analyzed these data because agencies (1) may use a direct hire authority to expedite the typical hiring process by eliminating certain steps traditionally required for competitive hiring; and (2) have discretionary authority to use a variety of pay flexibilities to support their employee recruitment, relocation, and retention efforts. We also included data reported by each selected service and installation for the total number of FWS AF positions that were authorized, filled, or vacant from fiscal years 2018 through 2024 (where available).

To assess the reliability of DOD data, we inquired about obvious errors and inconsistencies, such as missing data, duplicate entries, and out-of-range values, and reviewed written responses from DOD officials. We also interviewed DOD officials knowledgeable about the data to understand the source of the data, how they were collected, how they were updated, and any limitations of the data. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of our analysis. For additional information on the selected DOD services and installations, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The FWS pay system covers about 194,400 federal blue-collar hourly employees or about 9 percent of all federal civilian workers.[12] There are about 140,400 FWS employees at DOD—the largest FWS employer government-wide.

These employees are divided into two groups:

· AF employees are generally funded from the Treasury. DOD employs approximately 111,700 of 164,500 AF employees government-wide (68 percent).[13] Examples of AF work include aircraft mechanic, machinist, pipefitter, and welder.

· NAF employees are generally funded by facility-generated dollars, such as exchange services and commissaries on military bases. DOD employs approximately 28,700 of 29,900 NAF employees (96 percent). Examples of NAF work include truck driver, electrician, groundskeeper, and building maintenance worker.

As of April 2025, there are 245 wage areas (130 AF and 115 NAF areas) that cover the U.S. and its territories where FWS employees work.[14] These wage areas are used to help determine the pay rates for FWS employees. Each wage area is covered by one or more wage schedules that set pay rates for FWS employees.

Key entities involved with the administration of the FWS include:

· OPM. OPM issues regulations to implement and administer the FWS, such as provisions on uniform pay-setting; defining the geographic boundaries of individual wage and survey areas; conducting wage surveys; developing wage schedules; establishing occupational groupings, titling, and a job grading system; and developing and issuing job grading standards.[15]

· DOD. Designated by OPM, DOD is the lead agency that conducts the wage surveys, analyzes survey data, and issues wage schedules for all wage areas.[16] Within DOD, the Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service Wage and Salary Division is responsible for conducting annual wage surveys to collect wage data from private sector companies and developing and adjusting wage schedules. Other entities involved in the wage survey and wage schedule processes are:

· the Local Wage Survey Committees, which plan and conduct wage surveys in their designated wage areas and help support the collection of survey data that DOD uses to construct and issue the wage schedules;[17]

· the DOD and local data collectors, which collect wage data from selected private sector companies for the local wage surveys as determined by DOD, upon consideration of the report and recommendations from the Local Wage Survey Committees; and

· the DOD Wage Committee, which considers matters relating to the conduct of wage surveys and the establishment of wage schedules and makes recommendations on wage schedules to DOD.[18]

· FPRAC. Comprised of agency management and labor members, FPRAC is responsible for studying the prevailing rate system and other matters pertinent to the establishment of prevailing rates and for advising the OPM Director on the government-wide administration of the FWS.[19]

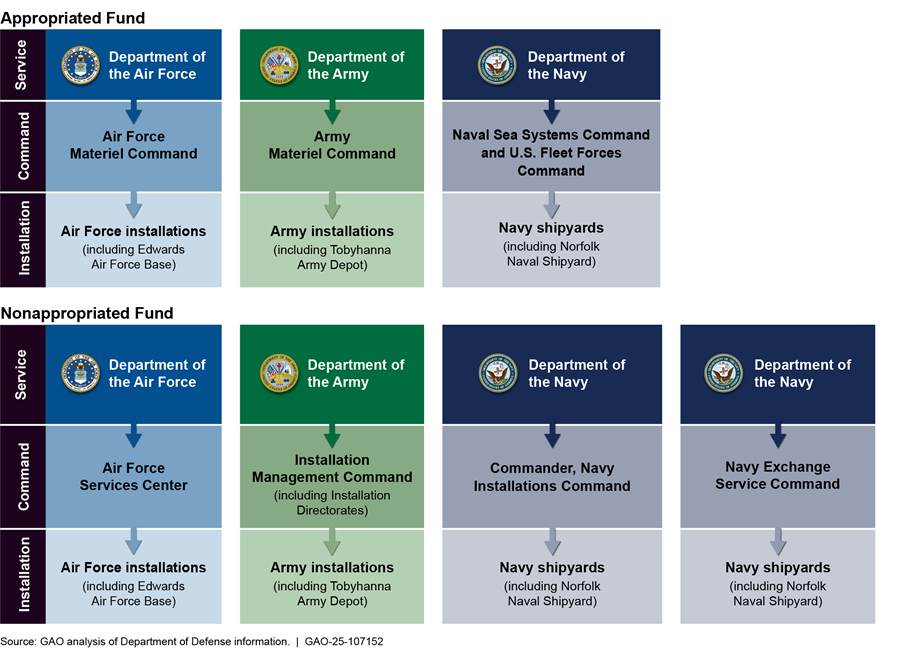

Figure 1 shows how the selected DOD services, commands, and installations generally oversee the management of workforce activities for the FWS AF and NAF workforces.

Figure 1: Organizational Chart for Management of Federal Wage System Appropriated Fund and Nonappropriated Fund Workforces by Selected Department of Defense Services, Commands, and Installations

Each local wage survey must contain wage rate data that are collected for a prescribed list of jobs, which cover a wide range of occupations with common skills and responsibilities in both private industry and the government.[20] The prescribed list of jobs is tied to specific industries that are included in the North American Industry Classification System, which is updated by the Office of Management and Budget every 5 years.[21] OPM officials reported that the most recent update from 2022 did not result in major changes to the types of private sector establishments that are included or excluded from the wage surveys. FPRAC may make recommendations on changes to the jobs and industries included in the wage surveys for the OPM Director’s consideration.[22]

For the FWS AF and NAF wage surveys, the following industries and occupations are used:

· AF wage survey. There are 16 industries surveyed, including, among others, manufacturing, utilities, and warehousing. Within the 16 industries, there are 21 jobs that are required to be surveyed and 34 optional jobs that can be added when relevant to a given wage area. Examples of AF surveyed jobs include janitor, forklift operator, electrician, sheet metal mechanic, pipefitter, welder, and machinist.

· NAF wage survey. There are 27 industries surveyed, including, among others, wholesale trade, retail trade, hotels and motels, restaurants, and recreational establishments. Within the 27 industries, there are 21 required jobs and 11 optional jobs. Examples of NAF surveyed jobs include food service worker, fast food worker, janitor, laborer, truck driver, cook, painter, and electrician.

Challenges with the FWS May Have Affected Recruitment and Retention at Selected DOD Services and Installations

According to OPM and DOD officials and FPRAC members, the underlying principles of the FWS have not been met because of several challenges with the FWS as we previously reported in March 2024.[23] These officials confirmed that these challenges remain and continue to be an issue. The challenges include:

· effect of the pay adjustment cap on final FWS wage rates and wage schedules;

· inexact match between local wage survey job descriptions used to compare federal FWS and private sector occupations; and

· amount of private sector wage data collected for local wage surveys.

In addition, officials from most selected DOD services and installations reported challenges with recruiting and retaining FWS employees, such as difficulty in competing with the private sector for skilled labor, offering competitive wage rates, and the lengthy federal onboarding process.

Legislative and Executive Branch Actions on Pay Have Generally Resulted in FWS Market Rate Deviations

We previously reported that FWS wage schedule rates have deviated from market wage levels.[24] This deviation stemmed in part from legislation enacted subsequent to the Prevailing Rate Systems Act of 1972, which limited the minimum and maximum pay adjustments granted to certain FWS employees by tying them to the average GS pay adjustment.[25] The $15 minimum special rate authorized by OPM also contributed to the deviation between the FWS wage rate and the prevailing rate.[26]

FWS Pay Adjustment Limit

DOD officials said that the effect of the pay adjustment cap was the most consequential challenge with the FWS. That is, even if the other challenges were addressed, they may have little to no effect on the final wage rates while the pay adjustment cap remains in effect. Officials from DOD reported that the cap on FWS pay adjustments affected recruitment and retention for DOD FWS AF employees because the private sector data collected from the wage surveys used to determine the local prevailing wage rates generally had a reduced effect on the final wage rates calculated by DOD.

Conversely, the FWS pay adjustments generally contributed to higher wage rates for NAF employees, according to DOD officials. DOD officials said that the pay adjustments for NAF employees were most likely higher than the prevailing rates because of a combination of the FWS pay adjustment floor—a minimum percentage increase granted to FWS employees—and the $15 minimum special rate. This is consistent with our prior FWS work where we found the FWS pay adjustments helped increase the average NAF nonsupervisory wage rates above the prevailing wage rates for almost all FWS NAF wage areas.[27]

In the fall of 2022, FPRAC recommended by consensus that the OPM Director recommend to Congress eliminating the pay adjustment cap. The Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2025 issued in 2024, included a commitment to addressing the challenges caused by the FWS pay adjustment cap by, for example, establishing a statutory minimum for annual pay rate adjustments. However, the pay adjustment cap remains in place as of July 2025.

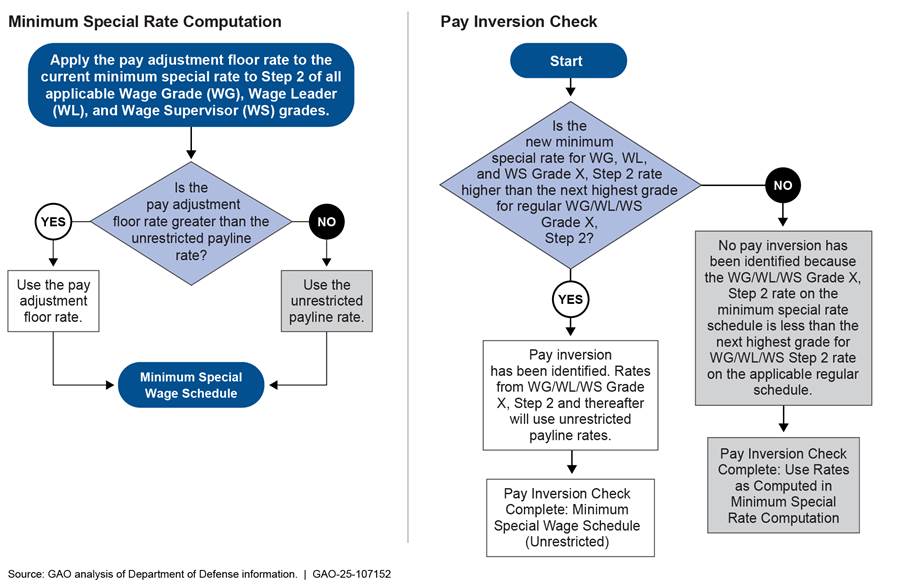

$15 Minimum Special Rate

DOD established 318 special rates in January 2022 to implement a minimum pay rate of $15 per hour for AF and NAF employees in certain wage areas where pay was less than $15 per hour at the time of implementation.[28] DOD established the special rates in response to OPM’s memorandum to implement the $15 minimum special rate. In such cases, the final wage rates are either set at the FWS pay adjustment floor rate (which is the minimum percentage increase) or at the unrestricted rate (which is the local prevailing wage rate as determined by the wage area survey results).[29]

When determining the final wage rates used for the wage schedules, DOD conducts a pay inversion check to fix instances where lower-grade employees are paid at higher rates than higher-grade employees. In such cases, OPM waived the pay adjustment cap to allow agencies to address the pay inversion issue by paying unrestricted rates.[30] According to DOD officials, all cases of inversion were addressed as of October 2023 and any future inversion will be addressed as part of DOD’s annual wage schedule updates. Figure 2 shows how DOD computes the minimum special rate and conducts a pay inversion check to determine the final wage schedule.

Figure 2: Department of Defense’s Process for Applying the $15 Minimum Special Rate and Conducting a Pay Inversion Check to Determine Federal Wage System Wage Rates

Note: Grade X for the pay inversion check is determined by the wage area’s highest grade on the special minimum wage schedule. Department of Defense (DOD) officials explained that they compare the highest grade, step 2 on the special minimum wage schedule against the next highest grade, step 2 on the regular wage schedule to determine whether pay inversion has occurred. For example, the special minimum wage schedule for the Waco, Texas appropriated fund wage area provides coverage up to grade 7. After the next wage survey is conducted, DOD officials will compare the grade 7 step 2 rate on the special minimum wage schedule to the grade 8 step 2 rate for the regular wage schedule to determine whether pay inversion has occurred.

According to DOD officials, FWS AF employees in 38 AF wage areas—including Norfolk, Virginia, that covers Norfolk Naval Shipyard—are on unrestricted wage schedules because of the $15 minimum special rate.[31] Specifically, FWS AF employees at Norfolk Naval Shipyard have been on the unrestricted wage schedule since July 2023. According to officials at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, this has helped with their FWS AF recruitment and retention efforts because they are paying wages that are competitive with the private sector. DOD officials said that most FWS NAF employees are mostly paid above the local prevailing wage rates because of the $15 minimum special rate and the FWS pay adjustment floor provision.

Revisions to the FWS Wage Area Definitions

In January 2025, OPM issued a final rule—effective October 1, 2025—in response to the FPRAC’s recommendation to change the regulatory criteria used to define the FWS AF wage area boundaries and more closely align the wage area boundaries with the GS locality pay areas. This will address most of the differences in pay among FWS AF employees within the same wage area and between FWS AF and GS employees working at the same location.[32] DOD officials said that the revisions to the FWS wage area definitions may help address the perception that differences in FWS and GS boundaries create pay inequities.

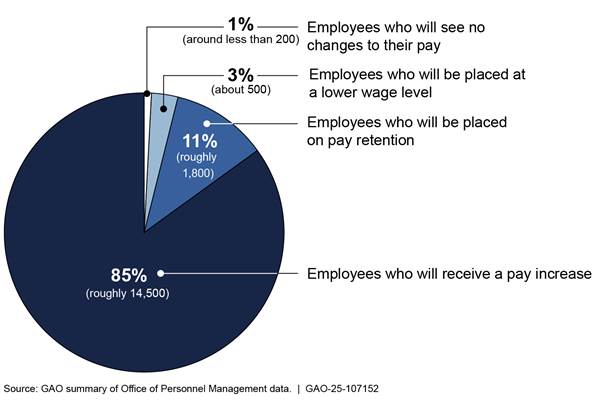

Aligning FWS AF wage areas and GS locality pay areas may change the composition of multiple FWS AF wage areas because the survey area may change, which could result in the removal of existing wage areas and a change in pay rates for affected FWS employees. According to OPM’s final rule, around 10 percent of the FWS AF workforce (or 17,000 FWS AF employees) in up to 30 federal agencies—including DOD—will be affected.[33] Figure 3 shows how the 17,000 FWS AF employees would be affected government-wide.

Figure 3: Total Number and Percent of Federal Wage System Appropriated Fund Employees Estimated to Be Affected by the Office of Personnel Management’s Revisions to Wage Area Definitions in October 2025

Note: This figure only applies to 10 percent of the Federal Wage System (FWS) appropriated fund (AF) workforce that will be affected by the Office of Personnel Management’s (OPM) final rule on Prevailing Rate Systems; Change in Criteria for Defining Appropriated Fund Federal Wage System Wage Areas, 90 Fed. Reg. 7428 (Jan. 21, 2025). OPM estimated the number of affected employees to be about 17,000 out of a total of approximately 170,000 FWS AF employees. Pay retention may apply to employees who are moving to different wage areas where there are lower wage rates than if they had stayed in their original wage areas. The final rule is scheduled to go into effect in October 2025.

OPM estimated that the overall budget effect of the changes to the FWS AF wage area criteria would be at a cost of about $140 million per year (or about 1 percent of the current base payroll for the FWS AF workforce as of January 2025).[34] According to OPM’s final rule and data, while such changes will affect up to 30 federal agencies ranging from large departments to small independent agencies, DOD and the Department of Veterans Affairs would be the most affected given they have the largest number of FWS employees. OPM does not anticipate that there will be a substantial effect on local economies or local labor markets because it will only affect a small number of FWS AF employees.

OPM estimated that about half of the overall cost will be incurred by Army because three large depots—Tobyhanna, Letterkenny, and Anniston—employ a substantial number of the FWS AF employees who will be affected by the changes. For instance, FWS AF employees at Tobyhanna will move from a lower wage area (Scranton) to a higher wage area (New York), ranging from a change of $0.49 per hour at WG-01 (lowest grade) to $7.85 per hour at WG-15 (highest grade).[35] The other two selected DOD installations in our review—Norfolk Naval Shipyard and Edwards—would not be affected by OPM’s final rule because the wage areas they are tied to already align with a single GS locality pay area.[36]

While Army officials reported that there are generally no widespread FWS recruitment and retention issues throughout the service, Tobyhanna officials told us that higher pay rates will help with recruiting and retaining harder-to-fill skill sets, such as tool and die makers and machinists. However, they also raised several concerns because increased payroll costs will need to be offset by charging higher rates for services provided to their DOD and non-DOD customers, such as the U.S. Border Patrol within U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Officials estimate that increases in FWS wages will lead to Tobyhanna increasing its hourly rates for customers by an estimated $9 per hour, which will make Tobyhanna more expensive and less competitive for providing maintenance services.

Tobyhanna is funded through the Army Working Capital Fund, which is a revolving fund that finances the depot’s operations and is reimbursed with payment from the maintenance customers it serves. Specifically, Tobyhanna’s rate is charged hourly to customers for services to reimburse the fund. Charging higher rates lessens the buying power of DOD and non-DOD customers. Therefore, Army’s readiness may be affected because of resulting budget constraints. Tobyhanna officials said such budget constraints prevent them from hiring more FWS employees.

Officials said increased customer rates may also result in a loss of business for Tobyhanna to private sector competitors that perform similar work, but at more competitive rates. Instead of an across-the-board pay increase resulting from OPM’s revised FWS wage area definitions, Tobyhanna officials said that a special wage rate would be the desired alternative because it would allow them to target the harder-to-fill skill sets for FWS employees to help address recruitment and retention challenges.

Federal and Private Sector Job Descriptions Used for Wage Surveys Do Not Exactly Match FWS Work

OPM developed a list of survey job descriptions to define the type of work performed for the required and optional jobs that are derived from OPM’s FWS job grading standards. According to OPM and DOD officials, these descriptions serve as benchmarks for both federal and private sector jobs. Specifically, DOD collects wage data for a prescribed list of benchmark jobs that cover a wide range of occupations common in skill and responsibility across the federal government and the private sector. OPM officials reported that the goal of the FWS wage surveys is to find private sector jobs that are broadly similar or comparable to federal jobs, but job descriptions are not always an exact match between private sector and federal occupations.

Agency and union officials at Tobyhanna also reported that the FWS survey job descriptions were not always an exact match between certain FWS occupations and the private sector occupations. Tobyhanna union officials stated that some of the FWS surveyed private sector jobs included forklift drivers and warehouse workers, which are a mismatch when compared to actual jobs performed at the depot. For example, agency and union officials at Tobyhanna said that the complex electronics work that the FWS employees conduct are not comparable to private industry because it is highly specialized.[37] OPM officials said that DOD has faced difficulties in finding comparable positions in other wage areas. In addition, DOD officials stated that there are no private sector companies that have jobs comparable to Tobyhanna within the local wage area, as well as across the country, from which to draw wage data. DOD officials said DOD uses a benchmark job survey methodology for the FWS to account for not being able to collect every job as well as overcome differences in job duties in the private sector. The benchmark job methodology’s goal is to produce results that provide pay for the appropriate grade level.

On the other hand, DOD officials and Local Wage Survey Committee members involved with the local NAF wage survey that covers Edwards said that the FWS surveyed jobs generally matched and were comparable to the types of FWS NAF occupations that local NAF entities employed, such as retail and hospitality. They did not attribute FWS NAF recruitment and retention challenges to the FWS surveyed jobs used for the local NAF wage surveys.

OPM officials said that OPM periodically reviews and updates the industries and required and optional survey jobs that are included in the wage surveys. Rather than reexamining the survey job descriptions on a schedule, OPM officials stated that they rely on the FPRAC to initiate such action.

In July 2022, the FPRAC’s proposal to establish a working group outlined several areas of the FWS that it planned to review. One of the identified areas was a review of the current benchmark survey job descriptions used for local wage surveys to determine if they adequately represent FWS work and allow for comparisons to private sector work levels. However, OPM and DOD officials stated that the FPRAC prioritized other areas, such as removing the pay adjustment cap and FWS AF wage area definitions. According to OPM, the FPRAC chairperson position remains vacant as of July 2025 and the committee will not continue any work without a chairperson. DOD officials stated that the FPRAC working group may revisit this topic in the future once the committee reconvenes.

According to Navy officials, outdated FWS job grading standards, which are the source for the FWS wage survey job descriptions, may affect wage rates. This, in turn, could affect FWS recruitment and retention. Navy officials reported that some of the FWS job grading standards were outdated in relation to the types of modern technologies and techniques that are currently used to conduct the work.[38] For example, the FWS job grading standards for electronic integrated systems mechanic and machining that are used for the electronic integrated systems mechanic and machinist occupations in the AF wage surveys were last updated in 1981 and 1999, respectively.

Navy officials stated that the outdated standards may result in an inability to properly grade and compensate some positions, such as a machinist, which has primarily evolved from manual to computer based (or automated). Since the FWS job grading standard for the machining occupation ends at Grade 11, Navy officials said that it may not allow higher-complexity tasks to be classified at higher grades to compensate the level of work performed.

OPM officials stated that the FWS job grading standards are used to determine the grade levels of the jobs and include criteria that generally describes typical grades for the work covered. They noted that the standards do not preclude agencies from classifying positions at levels above or below the grade range that are specifically described in the standard. In addition, OPM officials said that the FWS job grading standards are used to determine grades that are linked to basic pay rate ranges.

Agencies (including DOD and its services and installations) are responsible for classifying their FWS positions, which involves applying the appropriate titles, occupational series, and pay grades of their FWS employees, consistent with OPM job standards. FWS employees may formally appeal the classification of their positions at any time to DOD and can appeal to OPM once they receive DOD’s decision.[39]

Navy officials told us that they have made general inquiries to DOD and OPM in 2023 on updating the current job grading standards and establishing new standards for the machining occupation. However, Navy has not yet submitted a formal request. Officials said it would need to conduct an extensive review prior to obtaining support from DOD and all its components, which would then be escalated to OPM for review and approval. DOD officials said that since the system for job matching is generic, there could be a recruitment and retention problem with specialized positions. They said that using special rates is another option to address recruitment and retention challenges.

OPM officials reported that they update FWS job grading standards based on legislative and administration priorities and agency requests. Because there are over 200 FWS job grading standards, there is no set date on when OPM reviews and updates them. The last major update to an FWS occupation’s job grading standard—government-wide and for DOD—was in 2010 when OPM developed a new job grading standard for the precision measurement equipment calibrating occupation. OPM officials told us that OPM completed a study in 2009 at DOD’s request to review the job grading standard for the electronic measurement equipment mechanic occupation to differentiate repair and maintenance work from work that primarily involved calibration. Since then, OPM officials said they have continued to review and update the FWS job grading standards as needed. For example, OPM canceled FWS occupational series with fewer than 25 employees and reclassified affected positions in March 2017.[40]

Private Sector Response Rates in Local Wage Surveys May Affect the Accuracy of Local Wage Rates

Designated by OPM, DOD is responsible for conducting annual wage surveys to collect wage data from private sector companies to develop the wage schedules. DOD officials and local data collectors covering all selected DOD installations reported that it was a struggle to get complete wage data because not all private sector companies respond to the voluntary survey, including federal contractors, that DOD identified as relevant companies for the local wage surveys.[41]

Local Wage Survey Committee members from the Los Angeles, Scranton, and Norfolk AF wage areas covering our selected installations and local data collectors for the Scranton AF wage area covering Tobyhanna said not having complete market data may affect FWS wage rates because private sector employees who perform similar or comparable work may be paid at a higher rate. DOD officials said that they collect sufficient data for pay setting purposes and have standard weighting procedures to account for nonrespondents but that having a higher response rate would increase the accuracy of wage rates. This may help with FWS recruitment and retention because it could reflect the true market rate for the given wage area.

DOD officials and local data collectors at the selected installations stated that the reasons why private sector companies—including federal contractors—may not participate in the local wage surveys include the following: (1) no participation requirement because it is voluntary, (2) not trusting the federal government, and (3) not understanding the wage survey process. DOD officials said that a higher private sector response rate may help with determining the actual market wage rate because it would add data points reflecting private sector wage rates. However, officials said it may not result in higher market wage rates because wage rates from both lower- and higher-paid companies could be included in DOD’s final calculations for the wage schedules.

Although the DOD-provided lists of selected private sector companies do not identify whether they have federal contracts in place, local data collectors for the Scranton and Norfolk AF wage areas covering Tobyhanna and Norfolk Naval Shipyard said that they were aware of some federal contractors that have participated in the local wage survey and provided wage data.[42] Tobyhanna officials said that the federal contractors included in the Scranton AF wage survey are contracted by the depot and are generally paid higher than the local private sector industry, which is reflected in the AF wage survey results.

FPRAC provides recommendations on the administration of the FWS for the OPM Director’s consideration. OPM officials reported that it is OPM’s long-standing policy to follow the advice of the FPRAC for changes to the FWS regulations, such as potentially requiring private sector companies—including those with federal contracts—to participate in the wage surveys. As part of the FPRAC’s July 2022 proposal to establish a working group, one of the identified areas at that time was to review the laws and regulations governing private industry coverage and establishment size needed to meet the goal of determining prevailing wage levels.

DOD officials reported that they must obtain local wage survey data directly from private sector companies and cannot obtain their pay data through other means, such as a review of federal contracts with the agency. Even if DOD had access to wage rates for federal contractors that were awarded DOD contracts, DOD officials said the private sector companies may not meet the criteria for inclusion in the wage surveys because they may not have the minimum employment size or industries covered under the North American Industry Classification System.

DOD officials involved with the wage survey also reported that they did not have access to contract data at the department level on the total number of private sector companies that receive federal contracts in each FWS wage area. In addition, DOD officials told us that it would be difficult to determine whether any of the private sector companies selected for the local wage surveys have federal contracts because there is no method to identify them.

Even if there were a requirement for private sector companies that receive federal contracts to participate in the FWS wage surveys, officials we met with acknowledged that requiring such information may have no effect unless legislative action is taken to remove the FWS pay adjustment cap—the maximum pay increase granted to FWS employees by law that does not exceed the average GS pay adjustment—from annual appropriations laws.

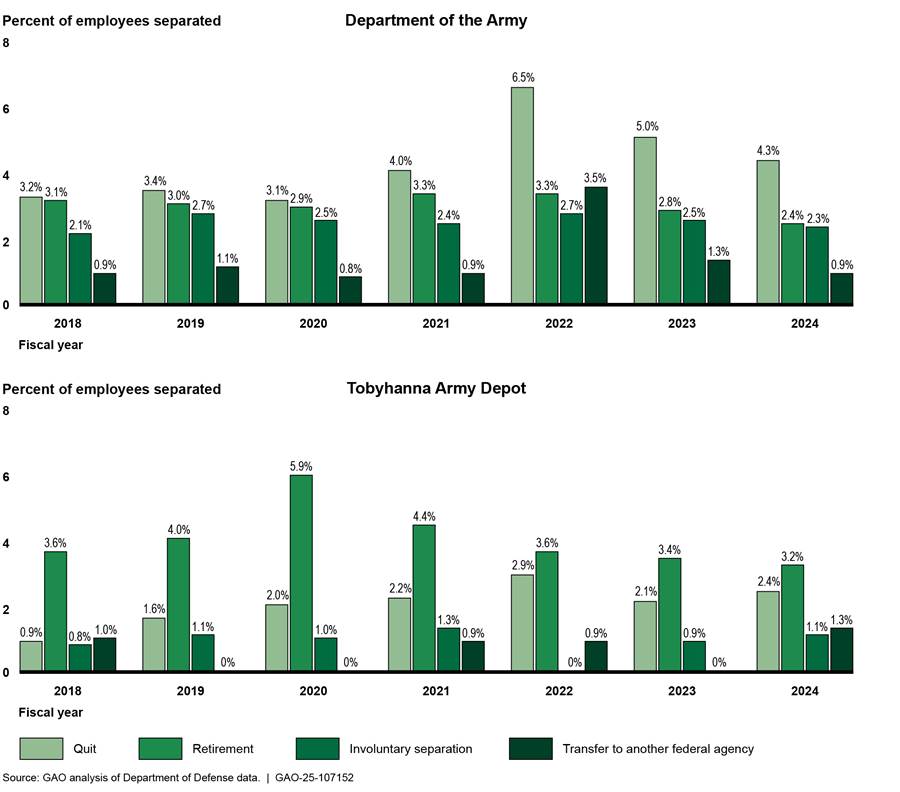

Selected DOD Services and Installations Reported Some FWS Recruitment and Retention Challenges

Officials at two of the three selected services identified some challenges recruiting and retaining their FWS AF employees, such as the inability to compete with the private sector for skilled labor and to offer competitive wage rates. Army officials said that Army did not have widespread FWS AF recruitment and retention issues, but challenges may exist at the local or installation levels. Officials from all three selected services did not report any overall challenges with recruitment and retention for their NAF employees at the service level.

Officials at all three selected installations told us about various FWS recruitment and retention challenges for both AF and NAF employees (see appendix I for more information), including the following challenges specific to each installation:

· Edwards. Officials attributed their challenges with the AF workforce to competition with the private sector and other local Air Force bases, the base’s remote location, and high cost of living. According to officials, NAF recruitment and retention challenges included the base’s remote location, insufficient work hours, and lower wages compared to the private sector.

· Tobyhanna. Officials said that Tobyhanna’s funding structure under the Army Working Capital Fund can pose challenges for recruiting and retaining skilled FWS AF employees, particularly in high-demand trades, such as tool and die makers and machinists. As discussed earlier, Tobyhanna operates on a reimbursable model and needs to recover all costs, including labor, through the rates it charges supported units and customers. Tobyhanna officials identified local private sector competition for higher pay as one challenge that may affect FWS recruitment and retention. Tobyhanna officials noted, however, that increasing employee salaries would also raise costs for customers and may prevent Tobyhanna from hiring more FWS employees.

In addition, Tobyhanna officials said they did not have retention challenges for NAF workers overall, but experienced some challenges recruiting certain positions, such as general laborers, because Tobyhanna could only offer part-time or flexible hours instead of full-time positions with benefits.

· Norfolk Naval Shipyard. Officials highlighted challenges with the lengthy federal onboarding process, private sector competition, and limited work arrangement flexibilities for AF workers. Officials said that they had difficulty recruiting some NAF employees, such as food service workers, because extensive background checks are required to work in Norfolk Naval Shipyard’s restricted areas.

Selected DOD Services and Installations Took Some Actions to Address FWS Recruitment and Retention Challenges, but Edwards Did Not Have FWS Staffing Targets

Selected DOD Services and Installations Used Direct Hire Authority, Pay Flexibilities, and Other Strategies to Address FWS Recruitment and Retention Challenges

Officials at selected DOD services and installations reported they used direct hire authority, pay flexibilities, and other strategies to recruit and retain FWS AF employees. Officials reported that overall, such actions and strategies helped them better recruit and retain their FWS AF employees, as discussed below.

Direct Hire Authority

|

Direct hire authority: allows agencies to expedite the typical hiring process by eliminating certain steps traditionally required for competitive hiring. Source: GAO analysis of hiring authorities. | GAO‑25‑107152 |

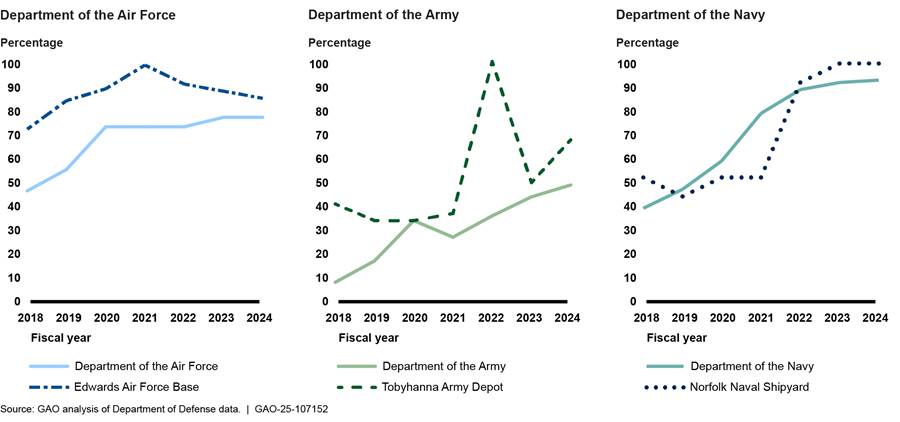

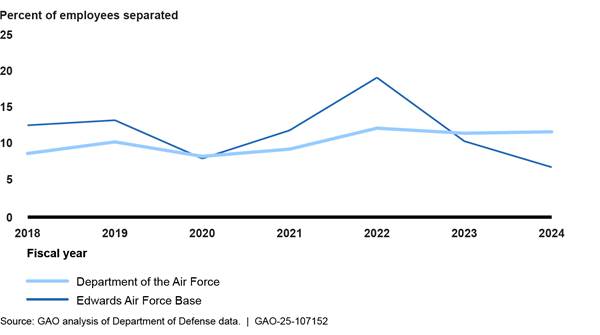

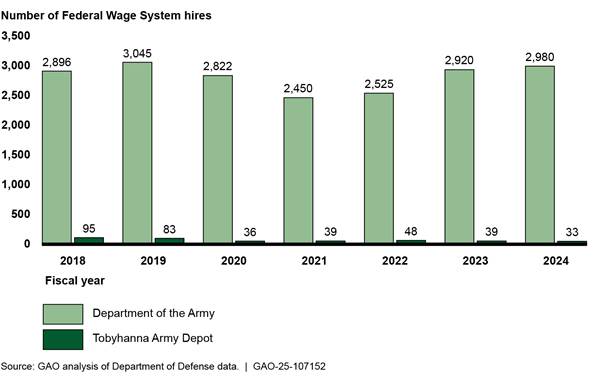

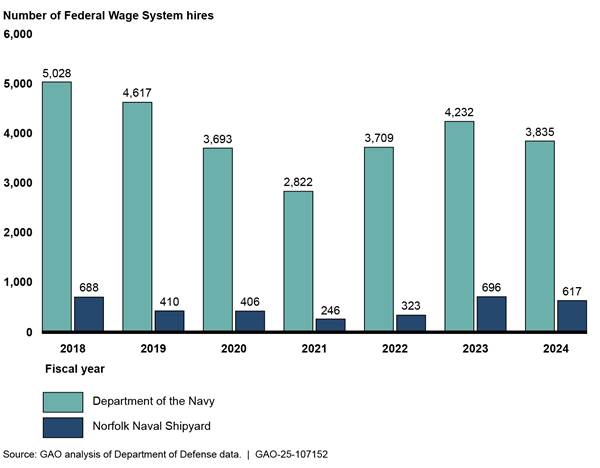

Figure 4 shows that all three selected services and installations used a direct hire authority from fiscal years 2018 through 2024.[43] However, the extent to which they used a direct hire authority varied across installations and over time. In addition, the percent of FWS AF employees newly hired under a direct hire authority generally increased from fiscal years 2018 through 2024 at all three selected services. Among the three selected services, Army had the lowest percentage of newly hired FWS AF employees under a direct hire authority, ranging from 7 percent in fiscal year 2018 to 48 percent in fiscal year 2024.

At the installation level, Tobyhanna and Norfolk Naval Shipyard had the largest increases in the percent of newly hired employees under direct hire authority from fiscal years 2021 through 2022. Edwards used a direct hire authority to employ all newly hired FWS AF employees in fiscal year 2021.

Figure 4: Percent of Federal Wage System Appropriated Fund Hires Using a Direct Hire Authority at Selected Department of Defense Services and Installations, Fiscal Years 2018–2024

Note: The data refer to the percent of newly hired Federal Wage System appropriated fund employees in a given fiscal year (e.g., 2018) who were hired under a Department of Defense (DOD) specific direct hire authority in that year. The DOD data do not differentiate the specific types of DOD-specific direct hire authorities used. The service-level percentages include the selected installations.

Officials at all three selected DOD services and installations cited the Domestic Defense Industrial Base Facilities and the Major Range and Test Facilities Base in the DOD as a direct hire authority that was frequently used when recruiting for FWS AF positions.[44] According to those officials, the direct hire authority for Domestic Defense Industrial Base Facilities and the Major Range and Test Facilities Base in the DOD was useful for hiring FWS AF employees because it provided flexibility and had no waiting requirement to onboard employees. For example, Air Force and Edwards officials said they could quickly fill mission critical occupations and hire retired military personnel.

Similarly, Navy officials said that the direct hire authority reduced onboarding times for new hires because hiring officials could defer preemployment contingencies, such as a physical exam, until after the employee onboarded.

Officials at all three selected DOD services said they did not use a direct hire authority to recruit FWS NAF employees. DOD officials confirmed that the use of direct hire authorities does not apply to individuals applying for FWS NAF positions.

Pay Flexibilities

Pay flexibilities refer to agencies’ discretionary authority to provide additional direct compensation in certain circumstances to support their recruitment, relocation, and retention efforts. According to officials at selected DOD services and installations, most of the selected DOD services and installations used pay flexibilities such as recruitment, retention, and relocation incentives; special rates; increased minimum hiring rate; special qualifications appointments; and the student loan repayment program to help recruit and retain FWS employees.[45]

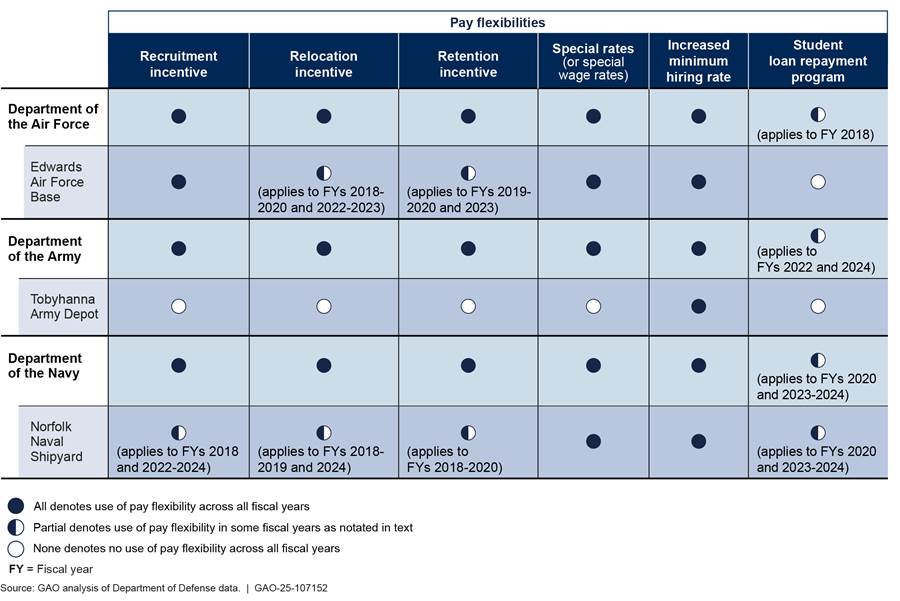

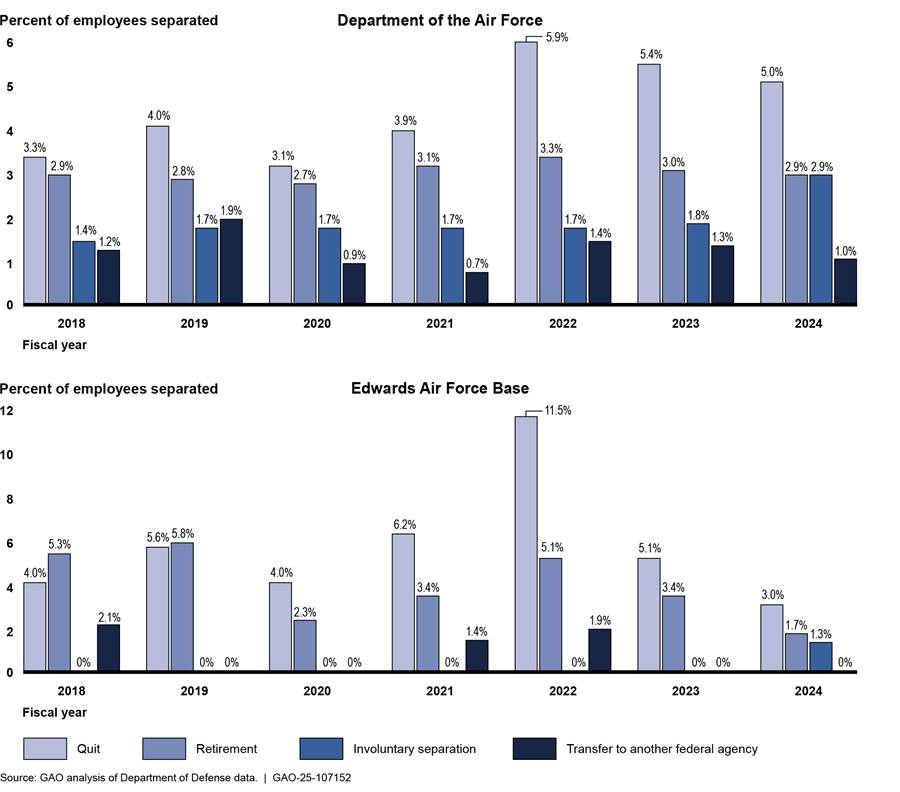

Figure 5 shows that the selected services used pay flexibilities to recruit and retain FWS AF employees, but the use of the flexibilities varied at the three selected installations. Officials at two selected installations described using pay flexibilities to address instances where pay for their FWS AF employees was lower than the pay offered by private sector establishments or other installations in the area. For example, Norfolk Naval Shipyard officials said that they used a retention incentive for nuclear welders to improve the attrition of those employees. Edwards officials said that pay flexibilities, such as special rates, improved retention of FWS AF employees. Moreover, Edwards officials said that they observed FWS employees leaving other installations to come to Edwards for higher pay because of the special rate.

Figure 5: Selected Department of Defense Services’ and Installations’ Use of Pay Flexibilities to Recruit and Retain Federal Wage System Appropriated Fund Employees, Fiscal Years 2018–2024

Note: The special rates column may also include, in addition to special rates, special schedules and unrestricted rates. Department of Defense (DOD) data do not differentiate a special rate versus a special schedule. According to DOD officials, unrestricted rates correspond nearly all the time with special rates and special rates cannot be less than the unrestricted rates. We excluded the use of highest previous rate and special qualifications appointments from the figure because Office of Personnel Management officials told us that the variables that would distinguish their use were unreliable.

Recruitment, Relocation, and Retention Incentives

|

Recruitment incentives: provided to a newly appointed employee if the agency has determined the position is likely to be difficult to fill in the absence of an incentive. Relocation incentives: provided to a current employee who must relocate to accept a position in a different geographic area if the agency determines the position is likely to be difficult to fill in the absence of an incentive. Retention incentives: provided to a current employee if the agency determines the unusually high or unique qualifications of the employee or a special need of the agency for the employee’s services makes it essential to retain the employee and the employee would be likely to leave federal service in the absence of a retention incentive. Source: GAO analysis of Office of Personnel Management regulations. | GAO‑25‑107152 |

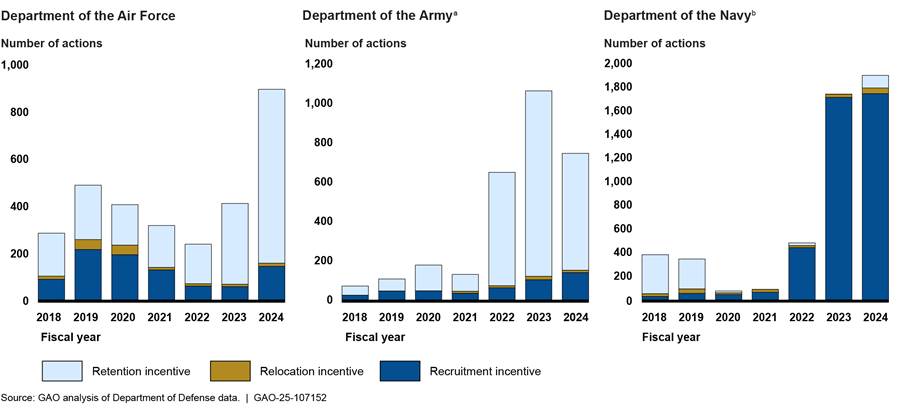

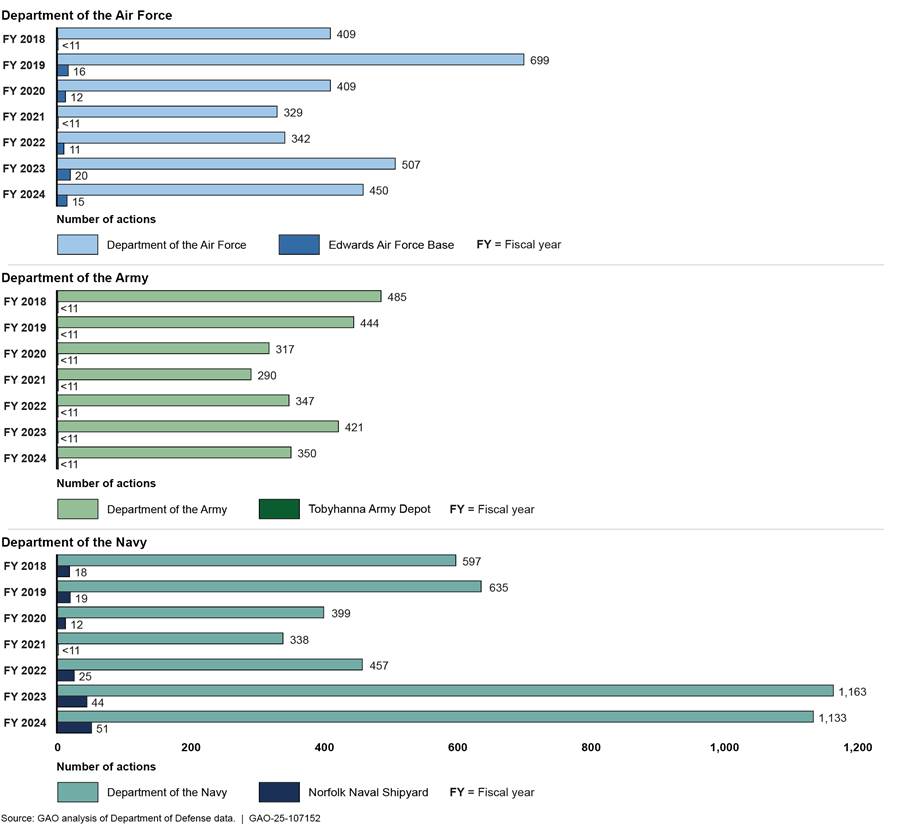

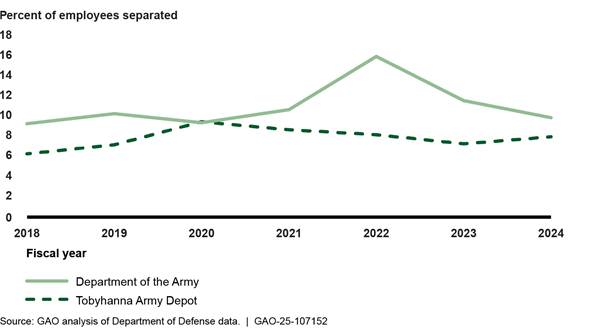

Officials at selected DOD services said they used recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives to recruit and retain FWS employees and delegated use of such incentives to the installations. Figure 6 shows all three selected services used recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives for FWS AF employees from fiscal years 2018 through 2024, but the extent to which they used these incentives varied over time.

Figure 6: Use of Recruitment, Relocation, and Retention Incentives for Federal Wage System Appropriated Fund Employees at Selected Department of Defense Services, Fiscal Years 2018–2024

aThe Department of the Army used 10 or fewer relocation incentives in fiscal years 2018 through 2020. For confidentiality, no employee counts of 10 or fewer are reported.

bThe Department of the Navy used 10 or fewer retention incentives in fiscal years 2021 and 2023. For confidentiality, no employee counts of 10 or fewer are reported.

· Air Force. According to DOD data, Air Force mainly used recruitment and retention incentives. Starting in fiscal year 2023, Air Force increased its use of retention incentives.

· Army. DOD data showed Army minimally used recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives from fiscal years 2018 through 2021. However, from fiscal years 2022 through 2023, Army increased its use of retention incentives. Army had the highest number (1,178) of retention incentive actions among the three selected services in fiscal year 2023.

· Navy. DOD data showed Navy minimally used retention and relocation incentives from fiscal years 2018 through 2024 and experienced an increase in the use of recruitment incentives starting in fiscal year 2022. Moreover, Navy had the highest number (1,744) of recruitment incentive actions among the three selected services in fiscal year 2024.

According to DOD data, use of recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives varied across the selected installations. As shown in table 1, Norfolk Naval Shipyard and Edwards used recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives while Tobyhanna did not use any of the three incentives for FWS AF employees from fiscal years 2018 through 2024.

Table 1: Use of Recruitment, Relocation, and Retention Incentives for Federal Wage System Appropriated Fund Employees at Edwards Air Force Base and Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Fiscal Years 2018–2024

|

|

Edwards Air Force Base |

Norfolk Naval Shipyard |

||||

|

|

Recruitment incentive |

Relocation incentive |

Retention incentive |

Recruitment incentive |

Relocation incentive |

Retention incentive |

|

Fiscal year |

Number of incentives used |

Number of incentives used |

Number of incentives used |

Number of incentives used |

Number of incentives used |

Number of incentives used |

|

2018 |

23 |

<11 |

0 |

<11 |

<11 |

295 |

|

2019 |

37 |

<11 |

<11 |

0 |

<11 |

234 |

|

2020 |

32 |

<11 |

<11 |

0 |

0 |

<11 |

|

2021 |

<11 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2022 |

<11 |

<11 |

0 |

77 |

0 |

0 |

|

2023 |

<11 |

<11 |

<11 |

293 |

0 |

0 |

|

2024 |

13 |

0 |

0 |

286 |

<11 |

0 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense data. | GAO‑25‑107152

Note: Our third selected installation—Tobyhanna Army Depot—did not use any recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives for each of fiscal years 2018 through 2024. For confidentiality, no employee counts of 10 or fewer are reported.

· Norfolk Naval Shipyard. According to DOD data, Norfolk Naval Shipyard used recruitment incentives to recruit a variety of occupations, such as electricians and pipefitters, in fiscal years 2023 and 2024. Norfolk Naval Shipyard also used retention incentives for welders in fiscal years 2018 and 2019. Norfolk Naval Shipyard officials said DOD chose to no longer allocate funding for retention incentives during the COVID-19 pandemic. Officials said the $15 minimum special rate reduced retention challenges for FWS employees, including welders.[46]

· Edwards. Edwards officials said they used recruitment incentives prior to the implementation of the special rate that they received in 2023, which increased wages for the applicable FWS employees and helped address challenges related to pay.[47] Officials said Edwards’s remote location helps provide the support needed for using recruitment incentives for harder-to-fill positions. On the other hand, Edwards officials said that finding support for using the retention incentives was difficult because to use them, there must be evidence that employees are likely to leave federal service. Officials said this could occur if FWS positions are affected by a future base realignment and closure action by DOD.

· Tobyhanna. Officials said that while they did not use recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives for FWS employees during the time of our review, they would like more flexibility in using a retention incentive. For example, Tobyhanna officials said that they are unable to use a retention incentive if an employee moves to a different job within Tobyhanna or to a different federal agency, since the employee would remain working within the federal government. Rather, Tobyhanna officials said they used other strategies, such as participating in hiring fairs, partnering with local schools for internships and shadowing opportunities, and using Army’s Pathways Program, to attract potential candidates.

DOD officials said that DOD has the authority to use pay flexibilities, such as recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives for NAF positions, but the use of the flexibilities may vary by service and installation. Air Force and Army officials said that they encouraged the use of recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives to address NAF recruitment and retention challenges as needed. For example, the Air Force lodging program used recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives for its hospitality workers to lower attrition rates. In addition, Norfolk Naval Shipyard NAF officials said they used recruitment incentives for some janitorial positions that were difficult to fill prior to the implementation of the $15 minimum special rate.

Special Rates

|

Special rates (or special wage rates): higher rates of pay for an occupation or group of occupations when recruitment or retention efforts are or would likely become significantly handicapped. $15 minimum special rate: minimum pay rate of $15 per hour as authorized by the Office of Personnel Management’s (OPM) special rate authority. Source: GAO analysis of OPM regulations and guidance. | GAO‑25‑107152 |

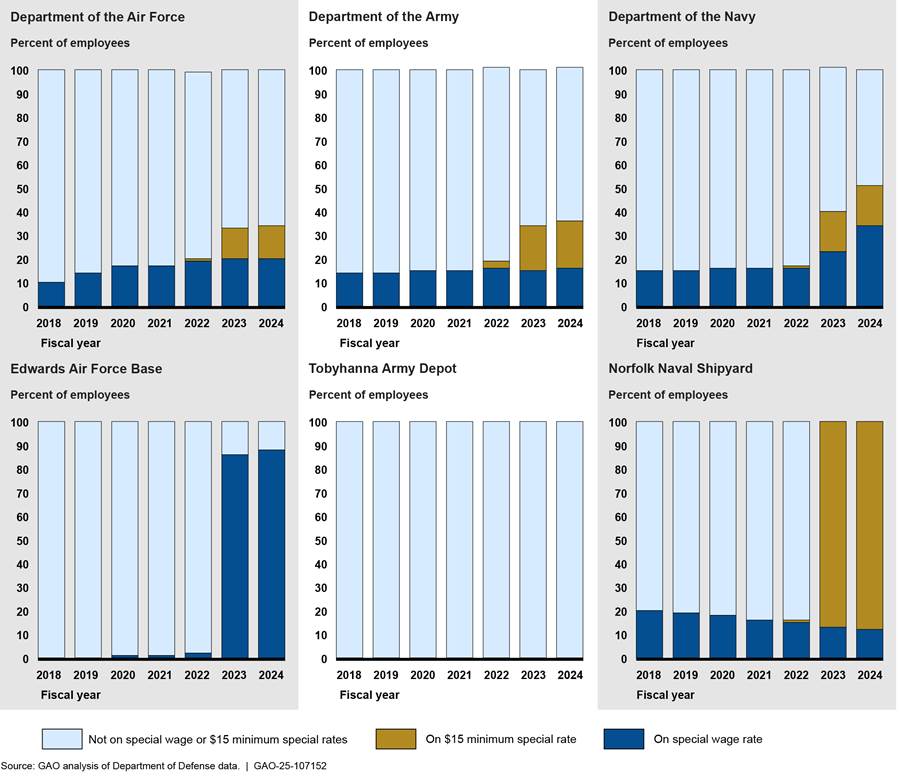

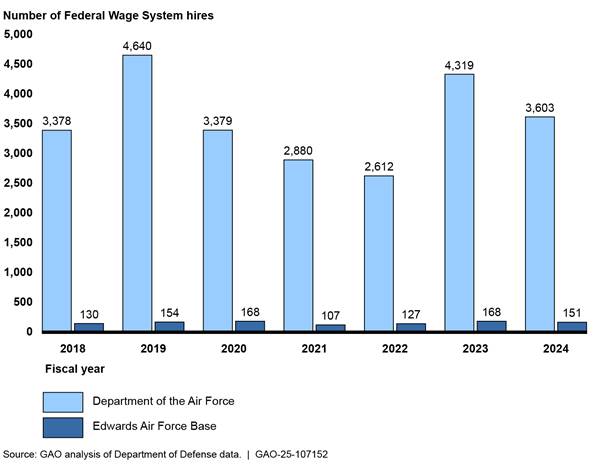

According to DOD data and officials from selected services, all three selected DOD services used special rates to recruit and retain FWS AF employees (see fig. 7).[48] DOD also established special rates in response to OPM’s 2022 memorandum to implement the $15 minimum special rate.[49]

Figure 7: Percent of Federal Wage System Appropriated Fund Employees on a Special Rate at Selected Department of Defense Services and Installations, Fiscal Years 2018–2024

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding. Counts of 10 or fewer are redacted from the output and did not contribute to these percentages. The service-level percentages include the selected installations. In addition, the Department of Defense established the $15 minimum special rate in response to the Office of Personnel Management’s 2022 memorandum to implement a minimum pay rate of $15 per hour for Federal Wage System employees in certain wage areas where pay was less than $15 per hour at the time of implementation.

As shown in figure 7, all three selected services had employees on special rates from fiscal years 2018 through 2024. Air Force officials said that they applied for special rates for FWS occupations that they had difficulty recruiting and retaining, such as aircraft maintenance and civil engineering. Navy officials said that Navy has been aggressively pursuing special rates to help address FWS recruitment and retention challenges. Army officials said that most of the recent special rate requests made have been for aircraft maintenance positions.

According to DOD data, two of the three selected installations, Edwards and Norfolk Naval Shipyard, used special rates. Tobyhanna did not use special rates from fiscal years 2018 through 2024.

· Edwards. Officials told us that OPM approved a special rate in 2023 for most FWS AF occupations at Edwards, such as aircraft maintenance, machinists, and welders, which has significantly improved recruitment and retention of these occupations. Edwards officials said they are applying for another special rate to cover the remaining FWS AF occupations not previously covered under the 2023 special rate, such as painters and maintenance mechanics.

· Norfolk Naval Shipyard. Officials said that some Norfolk Naval Shipyard FWS employees are stationed in Kings Bay, Georgia, to maintain nuclear submarines and Charleston, South Carolina, to train Navy personnel. According to officials, while the Norfolk AF wage area received a substantial pay raise in 2023 because of the implementation of the $15 minimum special rate, Norfolk Naval Shipyard employees stationed in Georgia and South Carolina did not receive the same pay raise. These employees stationed away from the Norfolk Naval Shipyard earn less than FWS employees stationed at the shipyard, despite having a similar cost of living, according to Norfolk Naval Shipyard officials. Norfolk Naval Shipyard officials said that they had difficulty incentivizing employees to work in Georgia and South Carolina because of pay issues. As a result, they are applying for a non-$15 minimum special rate for these employees.

OPM authorized a minimum pay rate of $15 per hour for GS and FWS employees in 2022. DOD established special rates in January 2022 to implement a minimum pay rate of $15 per hour for AF and NAF employees in certain wage areas whose hourly wages were less than $15 per hour at the time of implementation. Among the selected services and installations that used the $15 minimum special rate, officials discussed a range of experiences of how the $15 minimum special rate affected their respective FWS employees. Edwards officials said that the $15 minimum special rate did not affect their FWS AF and NAF employees because the minimum rate was already higher than $15 per hour. Tobyhanna officials said that the $15 minimum special rate did not affect Tobyhanna’s FWS AF employees because the minimum rate was already higher than $15 per hour, but it increased the salaries for FWS NAF employees.

· Navy and Norfolk Naval Shipyard. Navy officials said that the $15 minimum special rate helped with FWS AF and NAF recruitment and retention. Officials said that the $15 minimum special rate had a significant effect for Norfolk Naval Shipyard. Norfolk Naval Shipyard officials said that the $15 minimum special rate pushed wages above the prevailing rate in the Norfolk AF wage area, effectively overriding the pay adjustment cap. Officials said that this caused a substantial increase to FWS wage rates, which generated more interest in working at Norfolk Naval Shipyard and helped recruitment and retention. Norfolk Naval Shipyard NAF officials said that the $15 minimum special rate increased pay for NAF employees, which helped recruitment and retention. However, Norfolk Naval Shipyard NAF officials said that the $15 minimum special rate caused some cases of pay inversion with supervisors and non-supervisors.[50]

· Army. Army officials said that the $15 minimum special rate initially caused confusion for human capital officials because it resulted in a pay inversion where lower-grade employees were paid higher rates than higher-grade employees. Army NAF officials acknowledged that there were challenges with implementing the $15 minimum special rate, but that there has been a positive effect on recruiting and retaining NAF employees. For example, Army NAF officials said that they have observed more qualified candidates applying for jobs and a decrease in special rate requests.

· Air Force. Air Force officials said that the $15 minimum special rate generally helped with FWS AF and NAF recruitment and retention. Air Force NAF officials estimated that over half of Air Force’s NAF workforce was paid less than $15 per hour when the $15 minimum special rate was implemented. Air Force NAF officials said that although the $15 minimum special rate had a positive effect on FWS NAF recruitment and retention, it also raised some concerns of sustaining the costs associated with the $15 minimum special rate.

Increased Minimum Hiring Rate

|

Increased minimum hiring rate: used to establish any Federal Wage System-scheduled rate at step 2, 3, 4, or 5 as the minimum rate at which a new employee can be hired where the hiring rates prevailing for an occupation in private sector establishments in the wage area are higher than the step 1 rate and it is not possible to recruit qualified employees at the step 1 rate. Source: GAO analysis of Office of Personnel Management regulations. | GAO‑25‑107152 |

According to DOD data, all three selected services and installations used the increased minimum hiring rate from fiscal years 2018 through 2024 (see fig. 8).

Figure 8: Selected Department of Defense Services’ and Installations’ Use of Increased Minimum Hiring Rate for Federal Wage System Appropriated Fund Employees, Fiscal Years 2018–2024

Note: For confidentiality, no employee counts of 10 or fewer are reported. The service-level percentages include the selected installations.

Student Loan Repayment Program

|

Student loan repayment program: covers certain types of federally made, insured, or guaranteed student loans and is provided to attract job candidates or retain current employees. Source: GAO analysis of Office of Personnel Management regulations. | GAO‑25‑107152 |

According to DOD data, all three selected services and Norfolk Naval Shipyard minimally used the student loan repayment program to help address FWS recruitment and retention challenges from fiscal years 2018 through 2024 (see table 2).

Table 2: Selected Department of Defense Services’ and Installations’ Use of Student Loan Repayment Program for Federal Wage System Appropriated Fund Employees, Fiscal Years 2018–2024

|

Total number of student loan repayment program actions taken |

||||

|

|

Department of the Air Force |

Department of the Army |

Department of the Navy |

Norfolk Naval Shipyard |

|

Fiscal year |

|

|

|

|

|

2018 |

<11 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2019 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2020 |

0 |

0 |

<11 |

<11 |

|

2021 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2022 |

0 |

<11 |

0 |

0 |

|

2023 |

0 |

0 |

<11 |

<11 |

|

2024 |

0 |

<11 |

<11 |

<11 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense data. | GAO‑25‑107152

Note: For confidentiality, no employee counts of 10 or fewer are reported. Our two other selected installations—Edwards Air Force Base and Tobyhanna Army Depot—did not use the student loan repayment program from fiscal years 2018 through 2024.

Other Strategies to Recruit and Retain

Officials at all three selected installations described other FWS AF recruitment and retention efforts, such as:

· Job fairs and school recruiting events. Officials at all three selected installations said they used job fairs and recruiting events at local schools to recruit FWS AF employees.

· Training programs and career development. Tobyhanna and Norfolk Naval Shipyard officials said they offered training and career development opportunities for FWS AF employees. For example, Tobyhanna offers shadowing opportunities for FWS AF employees to explore different careers.

· Online and in-person advertisements. Edwards and Norfolk Naval Shipyard officials stated that they advertised open positions through a variety of online and in-person platforms, such as LinkedIn and freeway billboards.

Selected DOD Installations Supplemented FWS Workforce with Private Contractors to Help Address Workload Changes

Officials at the selected services and installations told us that they used contractors to supplement work performed by FWS employees as needed. Specifically, Tobyhanna and Norfolk Naval Shipyard officials told us that the use of contractors varied depending on their workload. Officials at the selected services told us that there is no guidance or justification for using contractors in lieu of FWS employees performing similar or comparable work.

At the selected installations, officials described various reasons for hiring contractors, such as balancing workload and the availability of FWS employees.

· Edwards. Officials said that private contractors work alongside FWS employees and that the base does not lose FWS positions to the contractors because there are distinct responsibilities for aerospace development and testing and support functions.

· Tobyhanna. Officials said that hiring private contractors can provide a quick and flexible workforce to accommodate Tobyhanna’s changing workload. Tobyhanna relies on federal contractors to provide qualified labor to support its maintenance mission because contractors are quicker to onboard and cheaper to use overall.

· Norfolk Naval Shipyard. Officials said that they use FWS employees on more complex tasks and contract lower skilled labor for simpler tasks. For example, FWS employees at the shipyard perform complex tasks, such as valve and pump repairs, electrical and electronic repairs of equipment, shipfitting, and welding. On the other hand, officials said they use private contractors for less complex work, such as painting and stagebuilding.

Selected DOD Services Set Workforce Goals and Delegated FWS Workforce Planning, but Edwards Did Not Have FWS AF Staffing Targets

We found that Air Force and Navy set overall workforce goals, such as recruitment and retention goals, in their service-wide civilian workforce plans which included FWS employees. In February 2025, Army rescinded its 2019 service-wide civilian workforce plan and the associated workforce goals which included FWS employees. According to Army officials, the civilian workforce plan was rescinded due to workforce changes implemented by the new administration. Officials said Army has paused the development of a new plan because of recent executive actions and DOD guidance related to workforce reduction.

The plans for Air Force and Navy had a similar goal to attract qualified civilian employees to fulfill the selected services’ mission. The services also outlined initiatives to support those workforce goals in separate implementation plans, including some initiatives specific to FWS AF employees. For example, Air Force’s implementation plan included initiatives related to workforce development and training opportunities for its AF employees.

According to the three selected services, workforce planning specific to the FWS AF workforce occurs either at the command or installation level. Officials from the selected services and commands told us that the commands are responsible for developing plans and analyzing their workload, budget, and mission to determine civilian personnel requirements.[51] Additionally, installations may also identify and plan for their workforce needs.[52]

According to our evidence-based policymaking practices, goals articulate what an organization wants to achieve to advance its mission and address relevant problems, needs, challenges, and opportunities.[53] They guide the organization’s activities and allow decision-makers to assess performance by comparing planned and actual results. Targets are levels of performance that can include measurable objectives to be accomplished within a time frame.

Norfolk Naval Shipyard and Edwards set overall goals for the FWS workforce in their civilian workforce plans. However, Edwards did not have measurable staffing targets for recruiting and retaining its FWS workforce in its workforce plan or other documents that it uses to manage its workforce. Tobyhanna is developing a human capital framework structure that includes strategic planning and talent management goals and manages its FWS workforce using staffing targets based on Army’s workload requirements.

· Norfolk Naval Shipyard. According to Navy officials, U.S. Fleet Forces Command sets the budget and Naval Sea Systems Command determines workforce capacity for the naval shipyards, including Norfolk Naval Shipyard. Shipyards are responsible for determining personnel requirements based on their budget and workload in coordination with both commands to determine the necessary workforce to complete their missions. According to a 2021 memorandum, Naval Sea Systems Command requires the shipyards to develop a Command Operations Plan that is intended to help management align on workload, hiring, and workforce development, among other things. Our review of Norfolk Naval Shipyard’s fiscal year 2026 Command Operations Plan found that it included FWS AF workload and staffing goals and targets.

Naval Sea Systems Command established targets for shipyards to optimize the productivity of its workforce, including a target for FWS employees in the wage grade, wage leader, and worker trainee (or apprentice) pay plans as a share of the total workforce. Norfolk Naval Shipyard’s Command Operations Plan includes a detailed discussion of its workload and the workforce requirements, including its FWS target, to complete its mission. Norfolk Naval Shipyard officials said they submit a monthly workforce staffing plan to U.S. Fleet Forces Command and Naval Sea Systems Command that includes planned and actual FWS employee hires and attritions. The monthly staffing plan showed the number of non-supervisory FWS employees employed at the shipyard compared to the monthly staffing target and tracks progress towards the command’s hiring targets.

· Edwards. Edwards follows a civilian workforce plan covering fiscal years 2017 through 2021 that included five human capital goals, such as recruiting and retaining mission-critical occupations.[54] Two of these occupations included FWS occupations in aircraft maintenance and munitions and maintenance. Officials said that the 2017-2021 workforce plan was still in effect at the time of our review and would be until they develop a new plan. The COVID-19 pandemic and other priorities disrupted the development of a new civilian workforce plan. Moreover, in February 2025, officials said that executive actions affecting the federal workforce will further delay Edwards’s workforce planning efforts, and they were unable to provide a time frame for when a new plan would be developed.

While Edwards set overall workforce goals in its 2017-2021 civilian workforce plan, the plan may not reflect the current needs of its civilian workforce—including for FWS AF employees—because it has not been updated since it was released in January 2017. In addition, we found that Edwards did not have measurable staffing targets for recruiting and retaining FWS AF employees in its 2017-2021 workforce plan or other documents that it uses to manage its workforce. Edwards officials said they determine staffing levels based on workload and budgetary requirements. Officials said they track some data related to recruitment and retention, such as gains and losses over time, but do not set measurable staffing targets for individual pay plans, such as FWS employees. Edwards officials said they conduct workforce planning from a “total force” perspective, meaning they consider all employees as a group regardless of pay plan, and do not focus specifically on FWS AF employees when planning for their workforce. However, as previously discussed, Edwards has taken actions, such as using direct hire authority and special rates, to specifically address FWS AF recruitment and retention challenges.

Although Edwards conducts workforce planning using a “total force” perspective, establishing measurable targets for its FWS AF recruitment and retention goals will help Edwards better assess the results of specific actions, such as using direct hire authority, and strategies taken to improve recruitment and retention. Measurable targets could also help Edwards determine if actions taken to improve recruitment and retention of FWS employees are working as intended. This, in turn, would help ensure that Edwards is effectively managing its resources, including personnel, to meet its mission.

· Tobyhanna. As of May 2025, Tobyhanna is drafting a human capital framework that outlines strategic planning and talent management goals for Tobyhanna’s civilian workforce, including FWS employees. For example, the framework identified FWS occupations that Tobyhanna plans to target in a hiring pilot initiative. Officials told us that Tobyhanna plans and manages its FWS employees in a workforce plan developed during its annual budget estimate submission process and according to workload requirements (or staffing targets) set by Army headquarters. The budget estimate submission includes estimates for expenses and on-board strength requirements for its workforce, including FWS employees, over 3 fiscal years.

Selected DOD Services and Installations Conducted NAF Workforce Planning in Accordance with Guidance

While we found that Air Force, Army, and Navy set overall workforce goals in their service-wide civilian workforce plans, DOD’s NAF leadership confirmed there is no DOD civilian workforce plan covering its NAF workforce. DOD’s NAF leadership said there could be civilian workforce plans at each DOD NAF instrumentality.[55] According to DOD guidance, heads of components with NAF employees are responsible for providing oversight of the application of NAF personnel policies.[56]

Each NAF component maintains separate human resources policies to supplement and implement DOD and OPM policy. Officials at the selected services said they do not require a civilian workforce plan with overall goals and targets related to recruitment and retention for the FWS NAF workforce. Officials said that local installations with NAF employees manage their workforces in accordance with their business needs, budget constraints, and how many employees they can afford to hire.