NONPROFIT DRUG COMPANIES

Information on Funding, Drug Types, Challenges, and Reported Effect

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact John Dicken at dickenj@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107153, a report to congressional committees

Information on Funding, Drug Types, Challenges, and Reported Effect

Why GAO Did This Study

In addition to rising drug prices, the U.S. has experienced ongoing drug shortages. Understanding the role that nonprofit drug companies could have in addressing these issues is an interest of Congress and researchers.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for GAO to review what is known about nonprofit drug companies. This report describes (1) their missions, funding sources, and drug types; (2) challenges they reported; and (3) reported effect of their efforts.

GAO defined a nonprofit drug company as an entity that primarily operates to develop, manufacture, and distribute drugs for the U.S. market and that has a federal tax-exempt status. GAO identified seven companies that met its definition.

To describe their missions, drugs, challenges, and effect, GAO interviewed representatives from all seven companies and reviewed company documents and studies. GAO interviewed three hospitals, one distributor, and one health center that purchase drugs from the companies about their experiences. GAO selected them based on recommendations from nonprofit drug company representatives and research. GAO interviewed Department of the Treasury and IRS officials about a reported tax-exempt status challenge.

What GAO Found

Nonprofit drug companies have more recently emerged as an alternative model to for-profit drug companies. While both bring brand-name and generic drugs to market in the U.S., nonprofit drug companies do not focus on achieving certain profit margins, and their drug development efforts are funded in large part by donations, which are not taxed, unlike for-profit companies. In this report, GAO describes seven nonprofit drug companies.

· Five focused their missions on lowering drug prices or making drugs available for specific patients (such as uninsured women), or both. Two focused their missions on ensuring a steady supply of generic drugs.

· Three received funding only from their company founders to support their efforts, two received funding only from organizations, and two received funding from both sources.

· All three companies with drugs on the market—Civica, Medicines360, and Harm Reduction Therapeutics—received funding in the form of grants or loans from organizations to support their drug development and other related work. These organizations included hospitals, charitable organizations, and a for-profit drug company.

· The companies’ current and planned drugs varied and included drugs with a variety of clinical uses.

Company representatives described challenges obtaining funding and expressed concerns about maintaining their tax-exempt status. Representatives from six companies described challenges obtaining enough funding for drug development. For example, representatives from one company described challenges obtaining enough funding from charitable organizations able to donate grants large enough to develop a drug, which the representatives attributed to the limited availability of large grants. Representatives from five companies expressed concerns about maintaining their tax-exempt status when using revenue from their drug sales to support their operations. One drug company reported a concern that revenue from its drug sales could be considered business income unrelated to the company’s charitable purpose by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and thus taxable. IRS officials told GAO the agency has not taken a position on whether the sale of lower-priced drugs or the sale of drugs to specific patients, for example, serves a charitable purpose. Further, they told GAO that the agency has no set percentage or threshold amount of unrelated business taxable income that would result in the loss of an organization’s tax-exempt status.

Representatives from the three companies with drugs on the market described the effect of their ongoing efforts. For example, one company sold a new drug-device combination product at a discounted price to certain hospitals and health centers, and another one provided a steadier supply of generic injectable drugs in shortage to hospitals compared to other manufacturers, according to representatives from the two companies. Representatives from some of the hospitals and the health center GAO spoke with generally agreed with the drug companies’ assessments of their effect.

Abbreviations

FDA Food and Drug Administration

IRS Internal Revenue Service

IUD intrauterine device

OTC over-the-counter

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 1, 2025

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

Prescription drug spending both by consumers and the federal government continues to grow in the U.S., in part because of rising drug prices. For example, Medicare and beneficiary spending for prescription drugs doubled from 2014 through 2022, increasing from $144 billion to $287 billion.[1] In addition to rising drug prices, the U.S. has experienced ongoing drug shortages—primarily among lower-priced generic drugs.[2] For example, from 2020 through 2023 more than twice as many generic drugs were in shortage compared to brand-name drugs.[3] Drug shortages are a significant public health concern as they may limit patient access to essential drugs such as antibiotics and pain medications, lead patients to use less medication than prescribed, or force providers to make difficult choices, such as which patients to prioritize for care.[4] As we have previously reported, drug shortages are often particular to generic drugs because of their low profit margins, which can limit drug manufacturers’ ability to buy more equipment or expand facilities to increase production, leading some drug manufacturers to leave the market.[5]

For-profit drug companies comprise most of the drug industry and play a critical role in developing and bringing the majority of brand-name and generic drugs to market.[6] The profits these drug companies earn from the sales of their drugs are used in various ways, including to fund research and development, provide compensation to company employees and deliver a return on investment to shareholders. Also, these profits are subject to federal income tax. In contrast, nonprofit drug companies have more recently emerged as an alternative model for the drug industry. Nonprofit drug companies also bring brand-name and generic drugs to market, in limited numbers, but, unlike the for-profit drug companies, they do not focus on achieving certain profit margins. Further, nonprofit drug companies’ drug development and other efforts are funded in large part by donations. Those companies that obtain federal tax-exempt status are generally exempt from federal income taxes. Nonprofit drug companies may seek to bring lower-priced drugs to the market and address a public health need; for example, by ensuring the availability of drugs experiencing shortages.

There has been interest from Congress and researchers in understanding the role that nonprofit drug companies could have in addressing the issues of high drug prices and drug shortages. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for us to review what is known about nonprofit drug companies in the U.S. and any challenges such companies have experienced in carrying out their work.[7] This report describes

1) the missions, funding, and drugs of nonprofit drug companies;

2) challenges reported by nonprofit drug company representatives; and

3) how nonprofit drug companies manufacture, set prices for, and distribute their drugs on the market.

To address our three objectives, we first defined a nonprofit drug company and then identified the number of companies that met our definition. We defined a nonprofit drug company as a pharmaceutical entity that primarily operates to develop, manufacture, and distribute human prescription or over-the-counter drugs for the U.S. market and that has a tax-exempt status under section 501(c) of the Internal Revenue Code.[8] To identify the number of nonprofit drug companies that met this definition, we reviewed drug industry and government reports related to nonprofit drug companies.[9] We also asked officials from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and two organizations that had expertise in research in the drug industry including research about nonprofit drug companies to confirm our list of nonprofit drug companies. Further, we interviewed representatives from the drug companies, as described below, during which we asked them to confirm our list of companies and identify any additional ones for consideration. We identified seven nonprofit drug companies that met our definition as of July 2024. The seven companies are Civica, Medicines360, Harm Reduction Therapeutics, NP2, Research Institute for Gender Therapeutics, Drew Quality Group, and Tutela Pharmaceuticals.[10]

To describe the missions, funding, and drugs of nonprofit drug companies, we reviewed documents and interviewed representatives from each company. The documents included company reports (that we obtained from the companies’ websites) and published studies that had information related to their mission statements, current and planned drug portfolios, and sources of funding used to start the companies. We also obtained publicly available tax returns from 2022 for each company to gather additional information related to their missions and the amounts of funding that they received.[11] We asked company representatives for additional information about their missions, drug portfolios, and funding during our interviews.

To describe the challenges reported by nonprofit drug company representatives, we interviewed representatives from all seven drug companies and asked them to describe challenges experienced since starting their nonprofit drug company. We also interviewed officials from the Department of the Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) about their perspectives on a tax-related challenge the nonprofit drug companies reported to us during our interviews, as discussed in this report.

To describe how nonprofit drug companies manufacture, set prices for, and distribute their drugs on the market, we focused on the three companies with drugs on the market at the time of our review. We reviewed available case studies, company reports, and published studies related to their operations. During our interviews with company representatives, we asked them about the approaches they use to manufacture, set prices for, and distribute their drugs as well as the effect of their efforts. We focused our review of the companies’ operations and reported effect on companies that currently have drugs on the market. Further, we obtained information about the experiences of a non-generalizable selection of five entities that purchase drugs from these nonprofit drug companies. We selected these purchasers based on nonprofit drug company representatives’ recommendations and research. These five purchasers included three hospitals, one health center, and one drug distributor.

We asked representatives from these purchasers (which included physicians, health center directors, and pharmacists) to provide their views on the effect described by representatives from the nonprofit drug companies. For published studies directly cited in the report, we performed an in-depth review of the findings and methods to ensure that the methods were appropriate and rigorous. We also provided each nonprofit drug company with a draft summary of findings specific to their company to verify their accuracy, and we incorporated any technical comments as appropriate. The results of our findings are not generalizable to nonprofit drug companies outside of our review.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Nonprofit Drug Company Status and Federal Tax Exemption

In order to obtain and maintain their tax-exempt status under sections 501(c)(3) and (c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code, nonprofit drug companies must be organized and operated exclusively for certain charitable purposes or operated exclusively for the promotion of social welfare, respectively. They must also meet the relevant requirements.[12]

Organizations with a federal tax exemption can receive funding from individuals and corporations in the form of donations as well as from corporations, private foundations, and government in the form of grants, and these funds are revenues of the organization. Income from an organization’s activities, including those substantially related to the organization’s charitable or social welfare purpose (that is the basis for its tax exemption), is also revenue of the organization.

While nonprofit organizations are generally exempt from federal income tax, activities that generate unrelated business taxable income can be taxed at the corporate rate in certain situations.[13] Most nonprofit organizations must file an annual information return.[14] IRS reviews the annual tax forms and the facts and circumstances of a tax-exempt organization’s activities as part of its responsibility to ensure that nonprofit organizations with a federal tax exemption comply with applicable laws and guidance.

Drug Approval Process

Nonprofit drug companies must meet the same requirements as for-profit companies to obtain FDA approval to market a drug for sale in the U.S. That is, they must submit a drug application to FDA that includes information on the drug’s components and composition, the manufacturing process, and location of manufacturing facilities, among other things.[15] For a brand-name prescription drug, a sponsor submits a new drug application to FDA that generally includes data from adequate and well-controlled clinical studies demonstrating the drug is safe and effective for its intended use.[16] For a generic prescription drug, a sponsor submits an abbreviated new drug application to FDA that includes data demonstrating therapeutic bioequivalence to a previously approved drug.[17] For either a brand-name or generic over-the-counter (OTC) drug, a sponsor can obtain approval by submitting either a new drug or an abbreviated new drug application, or it can market a drug without approval if it meets the requirements of the FDA OTC monograph process.[18]

Drug Supply Chain and Drug Shortages

The drug supply chain includes a number of entities, such as drug manufacturers, distributors, and purchasers of drugs such as hospitals.

· A drug manufacturer produces its own drugs that it sells to other entities within the supply chain.

· A drug manufacturer may also produce its own drugs through established partnerships with other companies.[19]

· A contract manufacturer provides manufacturing services such as drug formulation, sterilization, and packaging and labeling for other companies with FDA-approved drugs on a contract basis. Some also provide drug development services such as conducting research.

· A drug distributor purchases drugs directly from a manufacturer and sells them to other entities such as hospitals, health centers, retail pharmacies, and certain community-based organizations.[20]

· Other entities such as government programs, insurers, and employers pay for or contribute to the cost of drugs for consumers.

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act defines a drug shortage as a period of time when the demand or projected demand for a drug within the U.S. exceeds the supply of the drug.[21] Under federal law, FDA has specific responsibilities related to drug shortages, such as maintaining an up-to-date list of drugs experiencing a shortage (referred to as “in shortage”).[22] FDA determines whether a drug is in shortage using information about the production of the drug that manufacturers are required by law to report to the agency.[23]

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists also maintains an up-to-date list of drugs in shortage and defines a drug shortage more broadly than the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act does. That is, they define a drug shortage as a supply issue that affects how a pharmacy dispenses a drug (e.g., switching from a tablet to its liquid form) or that affects patient care when a prescriber must use an alternative drug.[24] A supply issue can result from an increased demand for a drug, a shortage in the drug’s active ingredients, or drug manufacturing problems, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.[25] Their drug shortage list is often used by hospital pharmacists and researchers and is based on data that are collected from several sources including health care providers.

Most Nonprofit Drug Companies Focused Their Missions on Drug Pricing and Availability, Received Funding from Their Founders, and Worked on a Variety of Drugs

Five of Seven Nonprofit Drug Companies Focused Their Missions on Lowering Drug Prices or Making Drugs Available for Specific Patients

Five of the seven nonprofit drug companies in our review focused their missions on either lowering prices, making drugs available for specific patient populations, or both. The other two companies focused their missions on ensuring a steady supply of generic drugs. (See fig. 1). Of the three nonprofit drug companies that currently have drugs on the market in the U.S.—Civica, Medicines360, and Harm Reduction Therapeutics—one focused on ensuring a steady supply of generic drugs and two focused on lowering drug prices and making drugs available for specific patients. (See fig. 1.)

aNaloxone is a medication approved by the FDA to reverse an opioid overdose. It is administered when a patient is showing signs of opioid overdose by intranasal spray (into the nose) or intramuscular (into the muscle), subcutaneous (under the skin), or intravenous (into a vein) injection.

More information about the three companies with drugs on the market follows.

|

Civica: A Member-based Company

Civica was founded by several hospital systems and private foundations. According to company representatives, hospital systems that join Civica as members must commit to purchasing a given share of their expected volume of generic injectable drugs. Company representatives stated that hospital system members participate in the selection of drugs for Civica to manufacture. Additionally, representatives told us that the company sells its drugs only to member hospital systems rather than the broader market. Source: GAO summary of information from the Civica website and statements of company representatives; Bigc Studio/stock.adobe.com (photo). | GAO‑25‑107153 |

· Civica. This company’s mission is focused on preventing and mitigating drug shortages by ensuring a reliable supply of quality, affordable generic injectable drugs. Civica’s drugs include those commonly used during surgeries and other medical procedures and many of them have been in shortage, as defined by FDA or the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. The company is focused on providing a steadier supply of these drugs to its hospital system members. Civica representatives told us they work towards providing a steadier supply both by securing multi-year contracts with its members and maintaining a reserve of the drugs to bridge a supply disruption.[26] Civica representatives told us their target for this reserve of drugs is a 6-month supply. For additional information about Civica’s hospital system members, see the side bar.

· Medicines360. This company is focused on making lower-priced drugs and medical devices available to women who have more limited access to health care, such as those who are uninsured. The company sells its hormonal intrauterine device (IUD)—LILETTA—to 340B Drug Pricing Program participants that include certain hospitals and health centers that care for many medically underserved and low-income patients.[27]

· Harm Reduction Therapeutics. This company’s mission stated that it aims to make a lower-priced naloxone product available to individuals who use opioids, including heroin and fentanyl. Company representatives explained that they sought to provide a more broadly accessible naloxone product, one that is available at a lower price and without a prescription. The company sells its drug RiVive—an OTC naloxone nasal spray that can reverse an opioid overdose—to community-based programs that work directly with people who use opioids and to other organizations.

Nonprofit Drug Companies Were Funded by Donations from Their Founders and Grants from Certain Organizations

Of the seven nonprofit drug companies, three received funding only from the individuals that founded the companies, two received funding only from organizations, and two from both.[28] Of the four companies that received funding from organizations, three have drugs on the market—Civica, Medicines360, and Harm Reduction Therapeutics.[29] Specifically, these three companies received funding in the form of grants and loans from organizations that included hospital system members and private foundations. See table 1 for information on the funding sources of the seven nonprofit drug companies in our review as well as information on the types of funds received.

|

Nonprofit drug company |

Funding type and source of funds |

||

|

Individual donations from company founders |

Grants and loans from organizations |

||

|

Civica |

— |

Grants and loans from its seven hospital system members that helped establish Civica and three private foundations. |

|

|

Medicines360 |

— |

Grant from a private foundation. |

|

|

Harm Reduction Therapeutics |

ü |

Grant from a for-profit drug company. |

|

|

NP2 |

ü |

Grants from private foundations. |

|

|

Research Institute for Gender Therapeutics |

ü |

— |

|

|

Drew Quality Group |

ü |

— |

|

|

Tutela Pharmaceuticals |

ü |

— |

|

Legend:

ü = Applicable

— = Not applicable

Source: GAO analysis of interviews with nonprofit drug companies and documents. | GAO‑25‑107153

Note: For some of the nonprofit drug companies, in addition to the founders, members of the board of directors also made individual donations to help start the company, according to nonprofit drug company representatives we interviewed.

The three nonprofit drug companies with drugs on the market received varying amounts of funding from organizations, which they used to start their companies and support their drug development and other related work.

· According to Civica representatives, Civica received a total amount of $100 million in grants and loans from its initial seven hospital system members and three private foundations to start the nonprofit drug company. According to Civica representatives, the company used this funding to purchase drugs to establish its reserve, among other things.

· According to a Medicines360 case study, Medicines360 received over $80 million from a private foundation to start the company.[30] Additionally, according to the case study, the company used this funding to conduct clinical trials to obtain FDA approval for LILETTA, among other things.[31]

· According to Harm Reduction Therapeutics representatives, in addition to a grant from Purdue Pharma, a for-profit drug company, the company received over $30 million in funding from the bankruptcy estate of Purdue Pharma. A company representative told us it used this funding to conduct clinical trials to obtain FDA approval of its drug, RiVive, as well as to set up its manufacturing processes.[32]

Nonprofit Drug Companies Focused on Developing Different Types of Drugs with a Variety of Clinical Uses

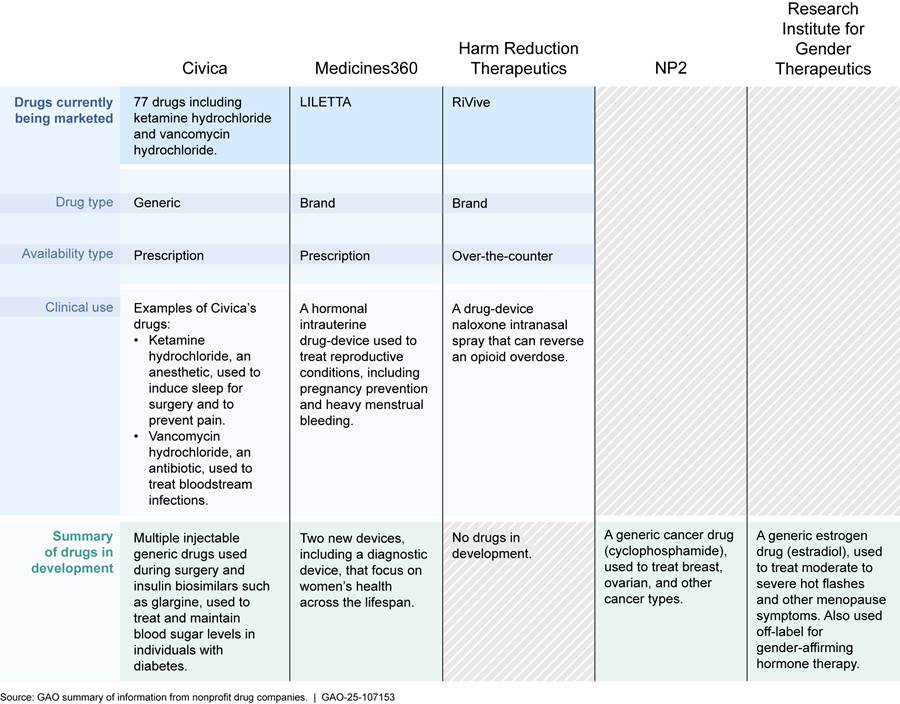

According to company representatives, the nonprofit drug companies in our review focused on developing different types of drugs that have a variety of clinical uses. The types of drugs the companies focused on developing included both brand-name and generic drugs and prescription and over-the-counter drugs. These drugs have various clinical uses such as to prevent pregnancy, treat cancer, and reverse an opioid overdose. As stated earlier, three of the seven nonprofit drug companies—Civica, Medicines360, and Harm Reduction Therapeutics—currently have drugs on the market in the U.S. Two other companies—NP2 and the Research Institute for Gender Therapeutics—have selected drugs to develop and bring to market, and the two remaining companies—Drew Quality Group and Tutela Pharmaceuticals—have not yet selected drugs for development. See figure 2 for additional information about the nonprofit drug companies’ drugs.

Figure 2. Nonprofit Drug Company Drugs on the Market in the U.S. or in Development, by Drug Type and Clinical Use

Notes: For the purpose of this figure, “drugs” include combination products, biological products, and devices. Combination products include products comprised of two or more regulated components (e.g., drug/device) that are physically, chemically, or otherwise combined or mixed and produced as a single entity. See 21 C.F.R. § 3.2(e)(1). They include products such as hormonal intrauterine devices (e.g., LILETTA) and nasal sprays (e.g., RiVive). Biological products are a diverse category of products that includes vaccines and allergenic products, blood and blood components, and proteins applicable to the prevention, treatment, or cure of a disease or condition. A biosimilar is a biological product that is highly similar to an already licensed biological product. See 42 U.S.C. § 262(i). Civica is developing the biosimilars for the broader U.S. market, not just its hospital system members. Medical devices include a wide range of products such as instruments or machines that are intended to prevent, diagnose, cure, treat, or mitigate disease or other conditions. See 21 U.S.C. § 321(h). Devices are regulated under a risk-based framework that is different from drugs or biological products and includes different types of submissions. The two other companies, Drew Quality Group and Tutela Pharmaceuticals, have not yet identified their first drug for development.

Nonprofit Drug Company Representatives Described Challenges Obtaining Funding and Expressed Concerns About Maintaining Their Tax-Exempt Status

Representatives from Six Nonprofit Drug Companies Described Challenges with Obtaining Enough Funding to Pursue Drug Development

Representatives from five of the seven nonprofit drug companies we interviewed provided estimates of funding they needed for drug development and manufacturing. Their estimates ranged from about $4 million to develop a generic drug, which includes the required testing of a drug to demonstrate its clinical equivalence, to about $80 million to develop a brand-name drug, which includes the cost of clinical trials, FDA user fees, and manufacturing.[33]

Representatives from six of the seven nonprofit drug companies in our review told us they experienced challenges obtaining funding. Five of these six companies stated that the challenges included obtaining funding specifically from private foundations for drug development for two primary reasons.[34]

Difficulty communicating the drug development process and risks. Representatives from two nonprofit drug companies in our review said that communicating to private foundations the complex scientific and regulatory procedures and risks associated with drug development was sometimes difficult because private foundations were unfamiliar with this process. As an example, one nonprofit drug company representative said that communicating to private foundations the 90 percent failure rate for FDA approval for a new drug was particularly challenging.[35] This representative also told us that private foundations expressed concerns about their drug’s ultimate approval given the high failure rate for new drugs. According to representatives from another nonprofit drug company, without an FDA-approved drug, private foundations may be unwilling to take such a risk.

Limited availability of large grants needed for drug development. Company representatives from one nonprofit drug company said that there are few private foundations able to provide grants large enough to develop a drug. As stated above, nonprofit drug company representatives estimated that they needed to obtain between about $4 to about $80 million in total to fund the development of a drug. Due to such limitations, company representatives said nonprofit drug companies would have to cobble together many small and medium size grants from foundations to have enough funding to bring a drug to market. Representatives from another company also told us that while they were able to raise funding from a few private foundations, the total amount they raised was about $1 million.

Given the limited availability of large grants, three companies relied exclusively on smaller donations from their founders, as previously discussed. Representatives from two of these companies said they used funding from these individual donors for administrative tasks necessary to start their companies, such as filing for their tax-exempt status with the IRS and conducting outreach about their mission online and at in-person events, including conferences.

Representatives from four of the nonprofit drug companies in our review stated that their nonprofit status limited their access to certain federal grants and loans for which they would otherwise be qualified to apply, if they were for-profit companies, such as those from the National Institutes of Health Small Business Programs and from the Small Business Administration loan program. According to these representatives, these grants and loans are available only to for-profit small businesses including, for example, those pursuing drug development.[36]

Nonprofit Drug Company Representatives Expressed Concerns That Drug Sales Could Affect Their Tax-Exempt Status

Representatives from the nonprofit drug companies in our review expressed two concerns about maintaining their tax-exempt status related to the sales of their drugs and took different approaches to address these concerns.

Using drug sales to support company operations. Representatives from five of the seven nonprofit drug companies in our review expressed a concern about maintaining their tax-exempt status when using revenue from the sales of their drugs to support their ongoing company operations.[37] Such operations include manufacturing their drugs and distributing them to purchasers, ensuring compliance with programs, such as the 340B Drug Pricing Program, and monitoring adverse events. One nonprofit drug company reported a concern that revenue from its drug sales could be considered unrelated business income by IRS and subject to taxation. Representatives from two nonprofit drug companies we spoke to said there is some uncertainty about whether the sales of lower-priced drugs or the sales of drugs to specific patient populations could affect their continued tax-exempt status.[38]

Selling drugs below cost to maintain tax-exempt status. Representatives from two of these five nonprofit drug companies also expressed a concern that maintaining their tax-exempt status could be conditional on the sale of a portion of their drugs at a price below their cost, as well as conditional on the donation of a portion of their drugs. According to representatives at these companies, maintaining tax-exempt status under these conditions would not be sustainable over time for their companies as they rely on their drug sales to fund their ongoing operations.

Approaches to address tax-exempt status concerns. Representatives from two nonprofit drug companies told us they took different approaches to address the concerns associated with maintaining their tax-exempt status while engaging in the sale of their drugs.

· Representatives from one company told us they established a commercial licensing agreement with a for-profit drug company whereby the for-profit drug company is solely responsible for the sale of its drug. Because of this agreement, the nonprofit drug company does not receive revenues from the sales of its drug. Rather, the company receives royalties from the for-profit drug company based on the total units of the drug that are sold, which generally are not considered unrelated business taxable income.[39] According to company representatives, the for-profit drug company provides the non-profit company the royalties on a quarterly basis.

· Representatives from another nonprofit drug company told us they established a separate for-profit subsidiary of their nonprofit drug company to carry out the sales of their drug once it is approved by FDA. Representatives explained that they took this step to avoid potential tax issues that may arise from receiving revenue from the sale of its drug.

Representatives from three nonprofit drug companies told us that, from their perspective, guidance from IRS about the kinds of activities, including the sale and distribution of drugs, that their companies may engage in to maintain their tax-exempt status could be helpful. One of these companies also told us that some organizations, with similar missions, may be hesitant to pursue tax-exempt status to become nonprofit drug companies without additional guidance.

Department of the Treasury and IRS viewpoints on maintaining tax-exempt status. IRS officials told us that when determining whether an organization keeps its tax-exempt status, the agency considers all of an organization’s activities.[40] According to IRS officials, an organization is considered as operating exclusively for its exempt purpose under section 501(c)(3) only if it engages primarily in activities that accomplish this purpose.[41] An organization is considered as operating exclusively for the promotion of social welfare under section 501(c)(4) if it is primarily engaged in promoting in some way the common good and general welfare of the people of the community.[42] IRS officials explained that their determination would depend on a review of the specific facts and circumstances of the organization’s activities such as the nonprofit drug company’s drug sales. IRS officials also told us it will use standard tax-exempt review procedures when examining the annual tax filing of nonprofit drug companies.[43]

With respect to organizations exempt under section 501(c)(3), IRS officials told us that the agency has not taken a position on whether the sale of lower-priced drugs or the sales of drugs to specific patient populations serves a charitable purpose. According to IRS officials, the sale of drugs by itself does not categorically serve a charitable purpose. If a company’s drug sales were considered unrelated business taxable income by IRS and therefore subject to taxation, IRS officials stated that there is no set percentage or threshold amount of such income that would result in the loss of an organization’s tax-exempt status.

In response to comments from representatives of the companies suggesting a need for more guidance on the issue of tax-exempt status, IRS officials told us that they would accept public comments to consider adding an item related to nonprofit drug companies to the agency’s Priority Guidance Plan.[44] The Priority Guidance Plan identifies the issues on which the IRS and Department of the Treasury will focus resources during the published guidance plan year. According to officials from the Department of the Treasury, as of October 2024, this plan does not include a guidance topic addressing nonprofit drug companies. As of January 2025, IRS has not received public comments on this topic, according to IRS officials.

Nonprofit Drug Companies with Drugs on the Market Conduct Their Work in Different Ways

The three nonprofit drug companies with drugs on the market—Civica, Medicines360, and Harm Reduction Therapeutics—manufacture, set prices for, and distribute their drugs in different ways. Representatives from the three companies described the effect of their ongoing efforts.

Civica’s Manufacturing, Price Setting, and Distribution Approaches, and Reported Effect

Manufacturing. Civica contracts with 14 manufacturer partners to manufacture 77 sterile generic injectable drugs under the Civica label. Representatives from Civica told us that they selected these manufacturers based on several factors, including their manufacturing procedures and technology, quality manufacturing record, and facility location. Civica representatives also told us they have back-up sources for certain drugs in the event that the primary manufacturing partner stops manufacturing the drug. A company representative explained that the use of a back-up source can help Civica provide to its hospital system members a steadier supply of its drugs.

In addition to using manufacturer partners, Civica has built a manufacturing facility in Virginia where it plans to manufacture sterile generic injectable drugs for its hospital system members as well as other drugs for the broader U.S. market.[45] Civica representatives said they can better prevent quality manufacturing problems that more commonly occur among generic injectable drugs by owning a manufacturing facility. As an example, contamination can occur during manufacturing due to the presence of particulates (e.g., metal, dust) in an injectable drug, which can cause adverse events in patients. Civica representatives explained that their facility will use manufacturing equipment with new technologies that limit human involvement, thereby reducing the risk of contamination.[46]

Civica representatives reported that the company plans to manufacture at its facility generic injectable drugs for its hospital system members, low-cost insulin for the U.S. market, and drugs to support the federal government’s response to any future pandemics or similar emergencies.[47] Civica representatives added they will continue to use their manufacturer partners to manufacture some of their sterile generic injectable drugs once their own facility is fully operational. As of September 2024, Civica’s manufacturing facility has begun operating as the company works to bring three insulin biosimilars to the broader U.S. market and multiple injectable generic drugs to the market for its hospital system members.

Price setting. Civica representatives told us they set the prices of their drugs based on the costs to manufacture them plus an amount to cover other costs associated with operating their company such as the costs for drug distribution, contract negotiations, and maintaining a reserve of drugs. Civica also sets the same prices for its drugs for all of its hospital system members, and these prices are based on multi-year contracts that the company has with its members for purchasing drugs (the only entities that currently purchase the company’s drugs), according to representatives.[48]

Hospital system members commit to purchase up to 50 percent of the total volume for each drug that they will need for the length of the contract and Civica sets its prices for the length of the contract unless the prices can be reduced during this time, according to representatives. Civica representatives told us the goal of this approach is to stabilize the price of injectable generic drugs.[49] According to two Civica hospital system members we interviewed, the price of a Civica drug may be higher than other manufacturers at the time a member commits to purchasing the drug, but it could be lower, on average, over the contract period.[50] These hospital system members added that they would be willing to pay a little more for Civica’s drugs—which are in shortage—to ensure a steadier supply. As stated earlier, Civica maintains a reserve of its drugs to help stabilize its supply.

Distribution. Civica uses Cencora, a large distributor that delivers drugs to most hospital pharmacies nationwide, to distribute its sterile generic injectable drugs to its hospital system members located across the U.S. A Civica hospital system member we interviewed told us they used Cencora prior to joining Civica, making it relatively easy for them to submit and receive ordered Civica drugs along with the other drugs that Cencora regularly distributes to them. Prior to Cencora, Civica used a different distribution approach that, according to the two hospital system members we interviewed, did not always meet their needs.

Reported effect. Civica representatives reported providing a steadier supply of certain sterile generic injectable drugs in shortage to its hospital system members, gaining additional members and expanding its operations. Representatives from two purchasers of Civica drugs told us they generally agreed with the company’s assessment of its effect, and findings from a recent study (based on another purchaser), were consistent with the company’s reported effect.[51]

· Representatives from one of the purchasers we interviewed highlighted two drugs in shortage that Civica has consistently provided to them as part of their contract with Civica. The two drugs are ketamine hydrochloride and fentanyl.[52] The representatives emphasized that having a reliable supply of these two drugs, which are commonly used in surgery to relieve pain and sedate patients, is critical for their hospital because both are not easily substituted with other drugs.

· Representatives from another purchaser we interviewed said that Civica has consistently provided to them lorazepam, another drug in shortage, as part of their contract with Civica.[53] This drug is commonly used before surgery and medical procedures to relieve anxiety and other health conditions. However, they reported that there have been times where Civica was unable to provide them other drugs in shortage such as piperacillin and tazobactam, a combination antibiotic that is used to treat a wide variety of bacterial infections.

· A recent study of the supply of generic injectable drugs that Civica provided to another purchaser found that it provided a steadier supply of most of the drugs in the study, compared to other manufacturers of the same drugs.[54] Specifically, between 2020 and 2022 Civica provided a higher amount of ordered supply for 15 of the 20 drugs in the study.[55] We conducted a review of the study’s findings and methods and concluded that the findings may not be generalizable to other drugs Civica provided to the one purchaser from 2020 to 2022 or during any other time periods or to other purchasers.

· Civica has also increased the number of its hospital system members from seven in 2018 to 59 in 2024, according to a company representative. Company representatives told us that they attribute this increase, in part, to the ongoing problem of drug shortages and to the new membership options that the company offers to prospective hospital system members (e.g., waiving certain fees). In total, the 59 hospital system members include about 1400 hospitals.

· Finally, Civica has expanded its operations to include two additional entities—Civica Foundation and CivicaScript—and has built a manufacturing facility, as described above. The Civica Foundation is a nonprofit organization that provides financial support for manufacturing low-cost insulin for the U.S. market. CivicaScript is a for-profit corporation that focuses on providing more affordable versions of commonly used but high-priced generic drugs that consumers purchase in retail pharmacies. CivicaScript brought its first generic drug to the market in 2022.[56]

Medicines360’s Manufacturing, Price Setting, and Distribution Approaches, and Reported Effect

|

Medicines360’s Commercial Agreement with AbbVie

Medicines360 established a commercial licensing agreement with AbbVie in 2013 to manufacture LILETTA and bring it to the U.S. market. Under this agreement, Medicines360 conducts all of the drug development work for LILETTA and AbbVie carries out the commercial operations such as the sales and marketing of LILETTA. Medicines360 selected AbbVie as its commercial partner for several reasons including AbbVie’s efforts to address women’s health care. Source: GAO summary of Medicines360 case study report; rocketclips/stock.adobe.com (photo). | GAO‑25‑107153 |

Manufacturing. Medicines360 partners with a for-profit drug company, AbbVie, to manufacture its one drug on the U.S. market, LILETTA, a hormonal IUD. As part of a commercial agreement between the companies, AbbVie is responsible for manufacturing LILETTA. AbbVie manufactures LILETTA at a facility that it owns. For additional information about this commercial agreement, see the side bar.

Price setting. Medicines360 representatives told us they set the price for LILETTA for 340B Drug Pricing Program participants, including certain hospitals and health centers, in 2015 at an amount below the costs to manufacture and distribute the IUD.[57] Specifically, Medicines360 set the price at $50 per unit for these participants, including eligible hospitals and health centers, because it determined that this price point would allow these entities to purchase and more readily keep in stock enough units to offer it to women at the point of care.[58] Representatives explained that having an IUD in stock can help facilitate access to contraception, as the provider can make the IUD available at the time a woman chooses it, without the need for a second appointment after ordering the IUD.

In 2020, Medicines360 increased the price of LILETTA to $100 per unit.[59] Representatives told us that the higher price has helped them to cover a larger portion of their expenses. Specifically, they told us the revenues from the higher price supported their additional clinical work that led to FDA approval for additional years of use for LILETTA, reducing the need to rely as heavily on other funding sources.[60]

Distribution. Medicines360’s for-profit drug company partner, AbbVie, manages the distribution of LILETTA to 340B Drug Pricing Program participants.[61] This arrangement is part of the commercial licensing agreement between the two companies.

Reported effect. According to Medicines360 representatives, their company has expanded women’s access to a hormonal IUD and provided it at a low cost.

· Medicines360 obtained FDA approval for LILETTA in 2015. This approval was based on a clinical study that included a sample of both women who had never given birth and those who had children, as well as women with different body weights. Further, the sample reflected the overall population of women in the U.S. according to race and ethnicity. Specifically, the proportion of Black women, white women, and women of Hispanic ethnicity included in the study sample were similar to proportions in the U.S. population, based on the 2010 U.S. census. The collection of data on the safety and effectiveness of an IUD from a broad range of women was important in helping to expand access to IUDs for women, according to representatives.

· Further, Medicines360 has continued to develop LILETTA after it was approved by FDA. The company obtained additional clinical data that supported FDA approval for additional years of use for preventing pregnancy. This same clinical data also supported FDA approval for a new indication for use—treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.[62]

· Medicines360 representatives stated that it has sold LILETTA to 340B Drug Pricing Program participants at a significantly lower price compared to the discount required by the 340B Drug Pricing Program. As of March 2024, Medicines360 has sold about half a million units of LILETTA to 340B Drug Pricing Program participants, according to representatives. They also stated that the company’s sales of LILETTA to 340B Drug Pricing Program participants have likely resulted in some federal government savings given its discounted price.

Representatives from two purchasers of LILETTA told us they had somewhat different experiences with the use of LILETTA and on the potential savings from its discounted price. Representatives from one purchaser of LILETTA we interviewed told us that before LILETTA came to the market in 2015, their health center paid significantly more to purchase and stock another hormonal IUD. The representatives told us that because of LILETTA’s lower price, the health center purchased only LILETTA and used its savings to help fund public health initiatives related to family planning. However, in comparison, representatives from another purchaser told us that its hospital continues to purchase a higher number of units of another hormonal IUD despite the lower price of LILETTA. They explained that this is because some patients and providers found the other hormonal IUD easier to insert.

Harm Reduction Therapeutics’ Manufacturing, Price Setting, and Distribution Approaches, and Reported Effect

Manufacturing. Harm Reduction Therapeutics uses one contract manufacturer to manufacture RiVive, an over-the-counter naloxone nasal spray that is used to reverse opioid overdose. Representatives from Harm Reduction Therapeutics told us that the manufacturer met their needs, in part, because it has the specialized manufacturing equipment required to produce nasal spray products such as RiVive.

Price setting. Representatives from Harm Reduction Therapeutics told us they set the price for RiVive based on the costs to manufacture it plus an amount to cover other costs associated with operating their company. RiVive is purchased by several entities, including community-based programs that work directly with people who use opioids, city and state governments, and colleges, according to representatives.[63] Representatives from the company also told us that these entities all pay the same price for RiVive and that the price does not depend on the volume that is purchased.[64]

Distribution. Harm Reduction Therapeutics uses both large and small distributors to distribute RiVive to the entities that purchase it. For example, company representatives told us that it works with Cardinal Health, a large nationwide distributor, to deliver RiVive to state governments because many require the use of this distributor to provide RiVive and other naloxone drugs. Company representatives also reported that they work with Remedy Alliance, a smaller distributor, to provide RiVive to community-based programs that work directly with people who use opioids across the U.S. and Puerto Rico.

Reported effect. Harm Reduction Therapeutics representatives stated that they have expanded the availability of naloxone and provided it at a low price. In July 2023, FDA approved RiVive to prevent opioid overdose death, and at the time of its approval, there was only one other OTC naloxone nasal spray on the market. As of February 2025, there were three other OTC naloxone nasal sprays on the market. According to FDA, the availability of naloxone—which is considered the standard treatment for opioid overdose—without a prescription is especially important because it can help address the ongoing public health issue of drug overdose by increasing consumer access to naloxone.[65] Harm Reduction Therapeutics representatives told us the approval of RiVive may have contributed to other manufacturers of naloxone nasal sprays seeking to obtain FDA approval to market them as OTC drugs. They also stated that RiVive’s approval along with the availability of other OTC naloxone sprays on the market may have contributed to their overall lower prices for the medication. Representatives from a purchaser of RiVive told us that the availability of OTC naloxone sprays on the market has helped to increase access to naloxone among people who use drugs in certain cases. For example, they stated that community-based programs that work with people who use drugs in one state are not authorized to provide prescription naloxone to them. However, these programs can now provide OTC naloxone sprays to people who use drugs.[66]

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of the Treasury, and IRS for review and comment. Each provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, the Secretary of the Treasury, the Commissioner of the IRS, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at dickenj@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix I.

John E. Dicken

Director, Health Care

GAO Contact

John E. Dicken, dickenj@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Pamela Dooley (Assistant Director), Bianca Eugene (Analyst-in-Charge), David Lichtenfeld, Romonda McKinney, Laurie Pachter, and Ravi Sharma made key contributions to this report. Also contributing were Sauravi Chakrabarty, Eric Lee, Ying (Sophia) Liu, Rhiannon Patterson, Ethiene Salgado-Rodriguez, MaryLynn Sergent, and Amogh Singhal.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program (Washington, D.C.: July 2024). Medicare is the federally financed health insurance program for persons aged 65 and over, certain individuals with disabilities, and individuals with end-stage renal disease.

[2]When referring to drugs, we are including biological products and combination products unless stated otherwise. Biological products are a diverse category of products that includes vaccines and allergenic products, blood and blood components, and proteins applicable to the prevention, treatment, or cure of a disease or condition. See 42 U.S.C. § 262(i)(1). Combination products include products comprised of two or more regulated components (e.g., drug/device) that are physically, chemically, or otherwise combined or mixed and produced as a single entity. 21 C.F.R. § 3.2(e)(1). They include hormonal intrauterine devices (known as IUDs) and nasal sprays.

[3]J. Daniel McGeeney, Emily McAden, and Aylin Sertkaya, “Analysis of Drug Shortages, 2018-2023,” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, January 2025).

[4]Mariana Socal and Joshua Sharfstein, “Drug Shortages—A Study in Complexity”, JAMA Network Open, vol. 7, no. 4 (2024).

[5]GAO, Drug Shortages: Certain Factors Are Strongly Associated with This Persistent Public Health Challenge, GAO‑16‑595 (Washington, D.C.: July 7, 2016). GAO, Drug Shortages: Public Health Threat Continues, Despite Efforts to Help Ensure Product Availability, GAO‑14‑194 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 10, 2014).

[6]For the purpose of our report, brand-name drugs are those drug products that have been approved under section 505(c) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S.C. § 355(c). A generic drug is approved by the Food and Drug Administration under section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act as therapeutically equivalent to a previously approved brand-name drug that works in the same way and is expected to have the same clinical effect and safety profile when administered to patients under the conditions specified in the labeling; generic drugs are generally marketed under a nonproprietary name. 21 U.S.C. § 355(j); 21 C.F.R. § 314.3.

[7]Pub. L. No. 117-328, § 3207, 136 Stat. 4459, 5820 (2022).

[8]26 U.S.C. § 501(c).

[9]We excluded nonprofit drug companies that are outside of the 50 states and the District of Columbia and those that primarily focused on other efforts such as manufacturing an active pharmaceutical ingredient—the substance responsible for a drug’s clinical effect—rather than the finished drug, or that primarily focused on drug research.

[10]We reviewed Internal Revenue Service (IRS) tax determination letters for all seven companies to determine when IRS recognized the tax-exempt status of each company. For the purposes of our report, we consider the date the company received their tax-exempt status as the date the company was founded. IRS recognized the tax-exempt status for each company in the following years: Civica (2020), Medicines360 (2009), Harm Reduction Therapeutics (2021), NP2 (2019), Research Institute for Gender Therapeutics (2023), Drew Quality Group (2014), and Tutela Pharmaceuticals (2020). Each company has a tax-exempt status under either section 501(c)(3) or (c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code. For the purposes of this report, we will specifically discuss the requirements for those sections. 26 U.S.C. §§ 501(c)(3); (c)(4).

[11]The 2022 tax returns were the most recent tax returns available for all seven companies at the time of our review.

[12]See 26 U.S.C. §§ 501(c)(3); (c)(4).

[13]26 U.S.C. § 511(a); see also 26 C.F.R. §1.511-1 et seq.; see also, e.g., Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, Tax on Unrelated Business Income of Exempt Organizations, Publication 598 (3-2021) (Washington, D.C.: March 2021).

[14]26 U.S.C. § 6033. Certain tax-exempt nonprofit organizations, including nonprofit drug companies, are required to file a Form 990 annually. The type of Form 990 generally depends on the financial activity of the organization. The form requires organizations to report certain information about their operations, such as governance, compensation, revenue and expenses, and specific organizational issues (e.g., lobbying by charities and private foundations).

[15]For combination products, a sponsor submits an application to FDA based on the product’s primary mode of action. The application must include information to demonstrate the product meets the relevant approval or clearance standard, including information on each constituent part of the combination product. See 21 U.S.C. § 353(g). Two nonprofit drug companies in our review have combination products on the market, as described later.

For biological products, a sponsor must submit a biologics license application to FDA. See 42 U.S.C. § 262(a). A sponsor must also submit a biologics license application to FDA for a biosimilar, which is a biological product that is highly similar to an already licensed biological product. The application must include information demonstrating that the biosimilar is highly similar to the reference product notwithstanding minor differences in clinically inactive components and that it has no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety purity or potency from the reference product. The sponsor must also submit to FDA information about the manufacturing process and manufacturing facilities, among other things. One nonprofit drug company in our review is developing biosimilars, as described later.

One nonprofit drug company in our review is developing devices, as described later. Medical devices include a wide range of products such as instruments or machines that are intended to prevent, diagnose, cure, treat, or mitigate disease or other conditions. See 21 U.S.C. § 321(h). Devices are regulated under a risk-based framework that is different from drugs or biological products and includes different types of submissions.

[16]21 U.S.C. § 355(b)(1).

[17]21 U.S.C. § 355(j).

[18]See 21 U.S.C. § 355h. Under the monograph process, OTC drugs can be marketed without prior FDA review and approval. FDA issues monographs to establish conditions—such as active ingredients, dosage forms, indications for use, and product labeling—under which an OTC drug in a given therapeutic category (e.g., sunscreen, antacid) is generally recognized as safe and effective for its intended use.

[19]One of the nonprofit drug companies in our review uses several manufacturing partners to produce drugs for the company, as described later.

[20]For example, community-based programs that work directly with people who use opioids purchase a drug from a drug distributor that we interviewed, as described later. This distributor first purchases the drug from one of the nonprofit drug companies in our review.

[21]21 U.S.C. § 356c(h)(2).

[22]See 21 U.S.C. § 356e.

[23]See 21 U.S.C. § 356c(a). Among other things, the law requires manufacturers to notify FDA of a permanent discontinuance or interruption in the manufacture of a drug that is likely to lead to a meaningful disruption in the supply of that drug in the U.S. and the reasons for the discontinuance or interruption.

For more information, see also GAO, Drug Shortages: HHS Should Implement a Mechanism to Coordinate Its Activities, GAO‑25‑107110 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 9, 2025).

[24]“Drug Shortages FAQs,” Drug Shortages, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, accessed January 31, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/drug-shortages-faqs#.

[25]“Guidelines and Tools,” ASHP Guidelines on Managing Drug Product Shortages, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, accessed January 31, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/policy-guidelines/docs/guidelines/managing-drug-product-shortages.pdf.

[26]Civica also has multi-year contracts with the manufacturers of its drugs, another way it works toward ensuring a steadier supply of drugs. Supply interruptions can occur for a variety of reasons, for example, because a manufacturer slows production to address quality issues or because of an interruption in the supply of a drug’s active pharmaceutical ingredient.

[27]The 340B Drug Pricing Program requires drug manufacturers to sell outpatient drugs at discounted prices to covered entities for the manufacturers’ drugs to be covered by Medicaid. See 42 U.S.C. § 256b. For the purposes of this report, we refer to those covered entities as 340B Drug Pricing Program participants.

[28]For some of the nonprofit drug companies, in addition to the founders, individual members of the board of directors also made donations to help start the company, according to nonprofit drug company representatives we interviewed.

[29]According to company representatives, company founders comprised the primary source of funding for three of the four nonprofit drug companies without drugs on the market. Grants from private foundations were the primary source of funding for the fourth company.

[30]According to the Medicines360 case study, this funding came from a grant. Medicines360, Nonprofit Pharma, Advancing a New Model for Equitable Access to Medicines (San Francisco, Calif.: July 29, 2022). https://medicines360.org/wp-content/uploads/M360_CaseStudy_FINAL_v4_single.pdf.

[31]According to company representatives, Medicines360 also received an additional $20 million grant from the same private foundation to support additional clinical testing for LILETTA once it was on the market.

[32]According to the Harm Reduction Therapeutics website, these funds were approved by the bankruptcy court administering Purdue Pharma’s chapter 11 proceedings, with the support of Purdue’s creditors including state and local governments. See Harm Reduction Therapeutics. “Frequently Asked Questions about RiVive,” accessed February 14, 2025, https://www.harmreductiontherapeutics.org/faq/.

[33]Federal law authorizes FDA to collect user fees to supplement the annual funding that Congress provides for the agency for the purposes of conducting specified activities. The Prescription Drug User Fee Act of 1992 authorized user fees for brand-name drugs. Pub. L. No. 102-571, tit. I, 106 Stat. 4491. The Generic Drug User Fee Amendments of 2012 authorized user fees for generic drugs. Pub. L. No. 112-144, tit. III, 126 Stat. 1008. Each must be reauthorized every five years.

[34]Private foundations are charitable organizations that typically have a single major source of funding (usually gifts from one family or corporation rather than funding from many sources) and may have as their primary activity the making of grants to other charitable organizations and to individuals, rather than the direct operation of charitable programs. See 26 U.S.C. § 509(a); see also “Exempt Organization Types,” Charities and Nonprofits, Internal Revenue Service, last modified September 27, 2024, https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/exempt-organization-types.

[35]Chi Heem Wong, Kien Wei Siah, and Andrew Lo, “Estimation of Clinical Trial Success Rates and Related Parameters,” Biostatistics, vol. 20, no. 2 (2019): 273-286.

[36]According to the National Institutes of Health website, the Small Business Programs provide support to early-stage small businesses with a focus on high-impact technologies including drugs and medical devices. Companies often use this funding to secure additional investors and the funding can range from approximately $300,000 to $2 million. See National Institutes of Health SEED, “Understanding SBIR and STTR,” accessed March 4, 2025. https://seed.nih.gov/small-business-funding/small-business-program-basics/understanding-sbir-sttr. According to the Small Business Administration website, Small Business Administration loans are guaranteed and can be used for long-term fixed assets, operating capital, the purchase or construction of new facilities, or the modernization of existing facilities. Loans range from $50,000 to $5.5 million. See U.S. Small Business Administration, “Loans,” accessed March 4, 2025, https://www.sba.gov/funding-programs/loans.

[37]Representatives from the other two companies told us that they do not have concerns about maintaining their tax-exempt status.

[38]While all five nonprofit drug companies that expressed this concern were recognized by IRS as tax exempt, none of their annual tax filings to date have reported drug sales as revenues. This is because the companies either do not yet have drug sales, or their drug sales began in calendar year 2024.

[39]See 26 U.S.C. § 512(b)(2). Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, Tax on Unrelated Business Income of Exempt Organizations, Publication 598 (3-2021) (Washington, D.C.: March 2021). Payments for the use of trademarks, trade names, or copyrights are ordinarily classified as royalties for federal tax purposes.

According to Medicines360, AbbVie licensed the company’s U.S. commercial rights for LILETTA, and therefore pays Medicines360 royalties for the units of LILETTA sold. Medicines360, Nonprofit Pharma.

[40]GAO has previously examined IRS oversight of other tax-exempt organizations, such as tax-exempt hospitals. See GAO, Tax Administration: Opportunities Exist to Improve Oversight of Hospitals’ Tax-Exempt Status, GAO‑20‑679 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 17, 2020).

[41]See 26 C.F.R. § 1.501(c)(3)-1(c)(1).

[42]See 26 C.F.R. § 1.501(c)(4)-1(a)(2)(i).

[43]IRS’s Internal Revenue Manual outlines its standard procedures for examining any tax-exempt organization’s annual tax filing to determine its compliance with tax-exemption requirements. According to officials from IRS, similar to any other exempt organization, IRS conducts the examination of a nonprofit organization’s tax filing by applying the relevant laws to the facts of the company’s operations. Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, Internal Revenue Manual 4.70.13.2 (Washington, D.C., November 2023).

[44]The IRS and Treasury solicit recommendations from the public for items that should be included and interested parties may submit recommendations for guidance at any time during the year. The Priority Guidance Plan is updated as needed. Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, Internal Revenue Manual 32.1.1.4.1 (08-02-2018) (Washington, D.C.: November 2019).

[45]Civica also has another entity that provides drugs to the broader market—that is, not just to its hospital system members—as noted later in the report.

[46]In a recent GAO report, FDA stated that advanced manufacturing—innovative technologies that improve product quality and process performance—may help avoid supply disruptions. Supply disruptions can lead to drug shortages. See GAO Drug Manufacturing: FDA Should Fully Assess Its Efforts to Encourage Innovation, GAO‑23‑105650 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 10, 2023).

[47]The Department of Health and Human Services partnered with the Phlow Corporation, Civica, and others to support the federal government’s response to COVID-19 and future public health emergencies by expanding drug manufacturing in the U.S. The department awarded the Phlow Corporation an initial 4-year $354 million contract to manufacture active pharmaceutical ingredients and sterile generic injectable drugs. To help build a manufacturing facility, Civica representatives told us it received a portion of these funds from the Phlow Corporation as well as funding from other sources that include Civica hospital system members and the Virginia and California state governments. For more information about this partnership, see the Department of Health and Human Services’ Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, “HHS, Industry Partners Expand U.S.-Based Pharmaceutical Manufacturing for COVID-19 Response,” accessed January 6, 2025, https://medicalcountermeasures.gov/newsroom/2020/phlow-us-manufacturing/.

[48]Civica representatives told us that beginning in 2024, the company no longer contracts with its members for a 5-year period—the length of the contracts that Civica previously established with its members. However, it still maintains multi-year contracts with the members.

[49]We and others have reported that generic injectable drugs often spike in price—defined as at least a doubling in price over the course of one year—during periods of shortage. See GAO, Generic Drugs Under Medicare: Part D Generic Drug Prices Declined Overall, but Some Had Extraordinary Price Increases, GAO‑16‑706 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 12, 2016) and Aayan N. Patel, Aaron S. Kesselheim, and Benjamin N. Rome, “Frequency of Generic Drug Price Spikes and Impact On Medicaid Spending,” Health Affairs, vol. 40, no.5 (2021).

[50]Two studies compared Civica’s average drug prices to other manufacturers between 2020 and 2022 and reported inconsistent results. One study found that, on average, Civica’s drug prices were about three percent lower, but at times Civica’s prices were higher than other manufacturers. See Carter Dredge et al., “Vaccinating Health Care Supply Chains Against Market Failure: The Case of Civica Rx,” New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst, vol. 4, no.10 (2023): 10-14. The other study found that the average prices for Civica’s drugs were lower at times (as much as about 38 percent lower), and higher at other times (as much as about 200 percent higher) than those of other manufacturers. See Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Impacts of a Nonprofit Membership-Based Pharmaceutical Company on Volume of Generic Drugs Sold and Drug Prices: A Case Study (Washington D.C.: July 2024).

[51]See Dredge et al., “Vaccinating Health Care Supply Chains Against Market Failure.”

[52]Both ketamine hydrocholoride and fentanyl have been in shortage multiple times since 2018 and are in shortage as of February 2025, according to both FDA and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. See “FDA Drug Shortages,” Current and Resolved Drug Shortages and Discontinuations Reported to FDA, Food and Drug Administration (website), accessed February 10, 2025, https://dps.fda.gov/drugshortages, and “Drug Shortage List,” All Drug Shortages Bulletins, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (website), accessed February 10, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/drug-shortages-list?page=All.

[53]Lorazepam has been in shortage multiple times since 2015 and is in shortage as of February 2025, according to both FDA and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. See “FDA Drug Shortages,” Current and Resolved Drug Shortages and Discontinuations Reported to FDA, Food and Drug Administration (website), accessed February 10, 2025, https://dps.fda.gov/drugshortages, and “Drug Shortage List,” All Drug Shortages Bulletins, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (website), accessed February 10, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/drug-shortages-list?page=All.

[54]See Dredge et al., “Vaccinating Health Care Supply Chains Against Market Failure.” This study analyzed the first 20 drugs in Civica’s portfolio.

[55]Specifically, Civica provided a higher amount than that which was committed to in its contract with the hospital system member.

[56]The name of CivicaScript’s first drug is abiraterone acetate and it is used to treat prostate cancer.

[57]Medicines360 representatives stated that, as part of its commercial licensing agreement, the company sets LILETTA’s price for 340B Drug Pricing Program participants. AbbVie sets LILETTA’s commercial price, that is, for other entities that purchase LILETTA. Under the agreement, Medicines360 receives milestone payments and royalties from AbbVie for all LILETTA sales.

[58]In 2015, LILETTA was approved by FDA for 3 years of use.

[59]In 2019, LILETTA was approved by FDA for 6 years of use.

[60]In 2022, LILETTA was approved by FDA for 8 years of use.

[61]Medicines360 representatives told us that participants of the 340B Drug Pricing Program purchase LILETTA from AbbVie.

[62]In 2023, FDA approved LILETTA for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. Medicines360 representatives told us that they have continued to develop new products for women since LILETTA was approved for extended years of use and a new indication.

[63]The community-based programs, referred to as harm reduction programs, work directly with people who use opioids and other drugs to help prevent overdose and offer options for treatment.

Representatives from Harm Reduction Therapeutics told us that, unlike other OTC drugs, RiVive is not available for purchase in a retail setting, such as a chain or online pharmacy.

[64]Typically, for-profit drug companies often provide discounts to entities that purchase a higher volume of drugs. Their drug prices can also vary depending on the entity that purchases the drug.

[65]“FDA Approves Second Over-the-Counter Naloxone Nasal Spray Product,” FDA News Release, Food and Drug Administration, accessed March 2024, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-second-over-counter-naloxone-nasal-spray-product.

[66]This representative from a purchaser of RiVive added that expanding the availability of naloxone for people who use opioids is critical because evidence-based interventions to prevent fatal opioid overdose are focused on access to naloxone among those people known to use opioids who are at risk of an overdose rather than the general public.