FOSTER CARE

HHS Should Help States Address Barriers to Using Federal Funds for Programs Serving Youth Transitioning to Adulthood

Report to the Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107154. For more information, contact Kathryn A. Larin at (202) 512-7215 or larink@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107154, a report to the Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate

HHS Should Help States Address Barriers to Using Federal Funds for Programs Serving Youth Transitioning to Adulthood

Why GAO Did This Study

The transition from adolescence to adulthood is a critical period and can be particularly difficult for youth aging out of foster care. Administered by ACF, the Chafee program supports youth in or formerly in foster care as they transition to adulthood.

GAO was asked to report on how states use Chafee program funds to assist older youth. This report addresses: (1) how selected states support youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood, (2) ACF resources for states on effective Chafee services, and (3) the extent that state and federal funds are used to support services for older youth.

GAO analyzed ACF expenditure data for fiscal years 2018 through 2022, the most recent available. GAO also reviewed federal Chafee allocations for fiscal year 2023. GAO also reviewed ACF’s spending and program guidance for the Chafee program. In addition, GAO interviewed HHS officials and six state child welfare agencies selected for variation in federal Chafee funding, instances of returning unused funds, administrative structures (state vs. county), and geographic region.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making one recommendation to HHS, to document its plan to have regional offices work with states to address any barriers they face in spending federal Chafee funds and ensure the plan includes guidance on how regional office staff can help jurisdictions address these challenges. HHS agreed with this recommendation.

What GAO Found

States generally have flexibility in determining the specific services offered to youth in the John H. Chafee Foster Care Program for Successful Transition to Adulthood. Selected state officials told GAO they decide on their service array by using data, participant feedback, and information from other states. Officials also reported offering youth services based on individual skills and needs. The most widely used services in selected states related to education, health, and housing.

The Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Administration for Children and Families (ACF) provides resources to help states select effective Chafee services. These resources include technical assistance, a database on services provided and youth outcomes, and evaluations of independent living programs. Officials in all six selected states told GAO they found ACF technical assistance helpful, but their use of the database and findings from evaluations varied. ACF officials said they have plans to increase the usefulness of both resources.

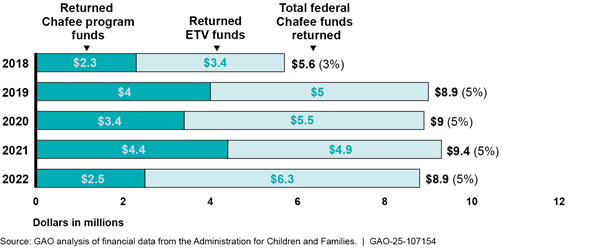

Officials in four selected states said state funds made up the majority of funding for Chafee services. Yet, states did not always spend all available federal funding, despite having unmet needs in serving youth. GAO’s analysis showed that in fiscal year 2022, 12 of 51 states returned Chafee funds, and 28 states returned Chafee education voucher funds for a total of about $8.9 million.

Note: Chafee Education and Training Voucher (ETV) grants support youth attending an institution of higher education. The number of states includes the District of Columbia. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

ACF officials told GAO it is planning to send its regional offices information on which states return funds to facilitate conversations between regional staff and state officials on fully spending federal funds. ACF officials said they would begin this process soon but do not have a documented plan for this initiative, nor have they communicated this plan to regional offices. By documenting its plan and providing guidance to address barriers to spending, ACF can better ensure the Chafee program meets its objective to support youth as they transition from foster care to adulthood.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

ACF |

Administration for Children and Families |

|

Chafee Program |

John H. Chafee Foster Care Program for Successful Transition to Adulthood |

|

ETV |

Education and Training Vouchers |

|

GED |

general equivalency diploma |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

NYTD |

National Youth in Transition Database |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 22, 2025

The Honorable Charles E. Grassley

Chairman

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

Dear Mr. Grassley:

The transition from adolescence to adulthood is a critical period in a young person’s life. This transition can be particularly difficult for youth aging out of foster care who have limited economic and social resources. These youth may have a difficult time acquiring the skills needed to live independently and face challenges leading to higher rates of housing instability and economic hardships compared with the general population.[1] The Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Administration for Children and Families (ACF) manages the John H. Chafee Foster Care Program for Successful Transition to Adulthood.

The Chafee program provides approximately $186 million annually to states, U.S. territories, and Tribes to support youth currently or formerly in foster care as they transition to adulthood.[2] Chafee funding may be used for a variety of purposes.[3] These purposes include assisting with room and board, providing independent living services such as housing and employment assistance, and helping youth participate in age-appropriate activities. As part of their annual allocations, Chafee Education and Training Voucher (ETV) grants can be used to provide older youth up to $5,000 per year for a maximum of 5 years for tuition, fees, books, supplies, transportation, and child care, among other expenses for postsecondary education or training.

You asked us to report on how states use Chafee program funds to assist older youth. This report: (1) describes how selected states support youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood, (2) describes ACF resources available to states for effective Chafee services, and (3) examines the extent to which states use state and federal Chafee funds to support services for older youth.

To address these objectives, we interviewed representatives from child welfare agencies in six states (California, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island). We selected these states for variation in federal Chafee funding allocations, instances of returning unused program funds, administrative structures (state vs. county), and geographic region. In selected states with county-administered child welfare systems (California and Pennsylvania), we also interviewed officials in two counties, which we selected for variation in size. To inform our discussions with state and county officials, we interviewed eight nationally recognized stakeholder groups. We selected these groups due to their prior research on services and outcomes for youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood and their experience working with states. We also interviewed ACF officials responsible for providing assistance to states, including officials from their research clearinghouse and technical assistance center.

To examine the extent to which states use state and federal Chafee funds, we analyzed ACF expenditure data for all states, Tribes, and territories for fiscal years 2018 to 2022, which was the most recent available. We also reviewed federal Chafee allocations for fiscal year 2023 and asked officials in selected states to describe their state spending for that year.[4] In addition, we reviewed relevant ACF documentation, such as Chafee spending and program guidance, and required annual state reports on child welfare.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Youth Transitioning from Foster Care to Adulthood

Children are removed from families and placed into foster care due to incidents of abuse, neglect, or other family crises. Children generally remain in foster care until a permanent suitable living arrangement can be made. This can be through addressing the issues that led to the child’s removal and returning the child to family or through adoption, guardianship, placement with a relative, or another permanent living arrangement.

In some cases, youth reach adulthood before leaving foster care, commonly referred to as “aging out.” Historically, aging out occurred at age 18, although many states now allow youth to remain in foster care up to age 21. In fiscal year 2022, approximately 18,500 youth in the U.S. transitioned out of foster care after reaching adulthood, according to ACF data.[5]

Chafee Program Eligibility and Funding

Federal law outlines eligibility for the Chafee program, and states may have additional requirements. Depending on the state, youth ages 14 to 23 currently or formerly in foster care may be eligible for a range of Chafee services. Additionally, older youth may be eligible for Chafee ETV grants to attend an institution of higher education. Research suggests that approximately 440,000 youth were eligible for the Chafee program in fiscal year 2021.[6] Eligible youth who are offered Chafee services are not required to participate in the program.

The Chafee program is funded through formula grants awarded to child welfare agencies in states (including the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) and participating Tribes.[7] Since the program was implemented in 1999, it has provided approximately $140 million annually in grant funding. The Chafee ETV program has provided approximately $43 million annually in additional grants. Allotments for states, U.S. territories, and Tribes are based on the share of youth in foster care relative to their population.

To receive Chafee funds, states must:

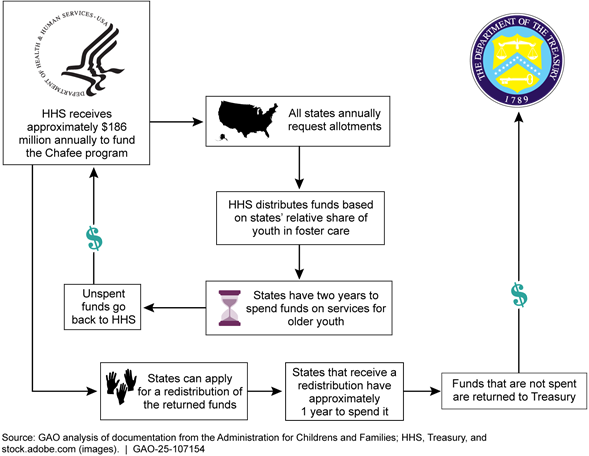

· Annually request Chafee and ETV allotments, which ACF may redistribute to other states if funds are not expended within a 2-year period (see fig. 1).[8] According to ACF officials, states can request redistributed funds even if they did not fully spend their initial allocation because circumstances that lead to underspending can vary year to year. States have an additional year to spend redistributed funds.

· Match Chafee and ETV allotments at 20 percent. States can contribute more than 20 percent towards programs for older youth transitioning out of foster care. The total amount that states spend nationally is unknown.[9]

· Submit a 5-year plan and annual report to ACF that describes how the state will serve Chafee-eligible youth and annual progress towards serving these youth.[10]

Figure 1: Grant Funding Cycle for Allotments and

Redistributions for the Chafee Foster Care Program for Successful Transition to

Adulthood

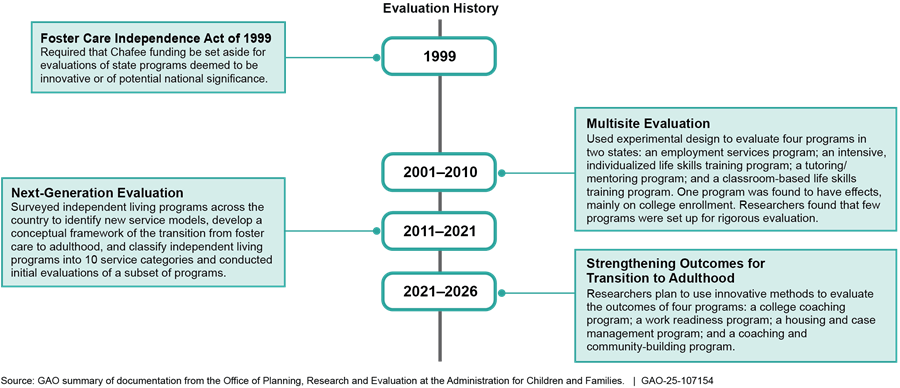

Since 1999, federal law has required ACF to set aside funding for evaluations of Chafee-funded programs that are “innovative or of potential national significance.”[11] According to ACF, a goal of the evaluations has been to assist states and stakeholders in designing services and planning programs that focus on the developmental milestones youth must achieve for successful outcomes.

Selected States Reported Providing a Range of Services for Youth Transitioning from Foster Care to Adulthood Based on Individual Needs

States’ Service Arrays Were Based on Data, Participant Feedback, and Information from Other States

States generally have flexibility in determining the specific programs and services offered as part of their Chafee programs. To make these decisions, officials from selected states told us they consider data, feedback from youth, and information from their peers in other states.

Data

Officials from five of six selected states reported collecting state-level population and outcome data; officials from three of these states said they use the data to inform programming for youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood. For example, California develops a statewide independent living report that compiles multiple outcome measures, highlights best practices and programs of promise across the state, and distributes the report to counties.[12] Officials in Illinois told us that they worked with a university to gather data about the postsecondary college campus experience of older youth who had been in foster care and used that data to design a new program with on-campus peer advocates. Officials from Pennsylvania told us they use site visits to directly collect and analyze data about the impact and quality of independent living services.

Youth and Other Feedback

Officials from all six selected states described how they use feedback from their youth advisory boards. For example, Rhode Island officials told us that, based on feedback from their youth advisory board, they reinstated a grant that provides youth with $300 per year to put toward an activity or item that would facilitate their growth toward independence. Officials in Florida said their youth advisory boards provide input on policies and practices for the independent living program.

Three of six selected states reported using information from youth surveys and focus groups to inform their service array. For example, Kentucky created an independent living exit survey to learn about the experiences of older youth in foster care and the types of services that could improve these experiences. Officials in Illinois told us they use data from a youth experience survey every 5 years to adjust their service and program practices. For example, the housing data from the survey is shared with the state housing authority, which officials said has helped expand housing voucher programs for older youth.

Information from Other States

Officials in three of six selected states told us that collaborating with other states and learning how they operate their programs is helpful. Officials in Florida told us that to determine their service and program offerings, they do research by consulting with other states during quarterly calls. Kentucky officials noted that they benefited from using a listserv to solicit feedback from other states regarding best practices, programming, services, and understanding the law. In addition to state-to-state support, California officials told us that counties learned best from each other by providing information about their independent living programs, such as through comparing state data on county services and outcomes.

States Offer Youth Services Based on Participants’ Individual Skills, Needs, and Goals

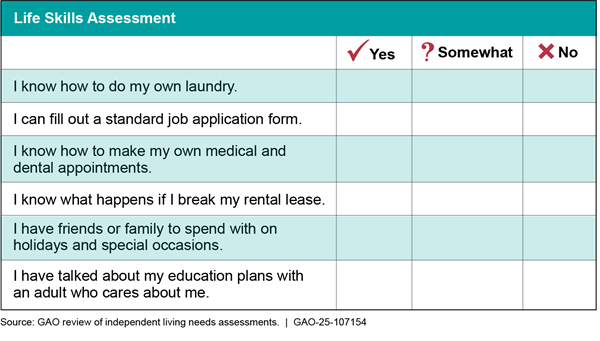

Officials in all selected states told us they used independent living needs assessments to identify the skills, needs, and goals of youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood (see fig. 2). The results of these assessments are used to determine on a case-by-case basis which independent living services to provide to older youth. States varied on when these assessments take place. For example, officials in Illinois told us that youth must complete a skills assessment at ages 14 and 16, and 6 months prior to their case being closed. Officials in Rhode Island told us they automatically referred youth for this assessment at 16 years old and then used those assessment results to make referrals for services.

Figure 2: Examples of Questions on Independent Living

Needs Assessments for Youth Transitioning from Foster Care to Adulthood

Note: An independent living needs assessment identifies a youth’s basic skills, emotional and social capabilities, strengths, and needs to match the youth with appropriate services.

In addition, officials from all selected states described working with older youth to develop transition plans.[13] Youth transition plans are individualized and designed to set goals related to independent living skills and other needs. Along with insight from their caseworker, youth determine their goals and the caseworker makes recommendations based on their needs. For example, officials in Kentucky told us that independent living specialists meet with every youth in care at age 17 to develop an individualized transition plan. Officials in Florida said that all youth are required to create a budget and needs assessment annually to determine the services and financial support they need.

States Provided Education Support, Health Education, Housing, and Other Services to Older Youth

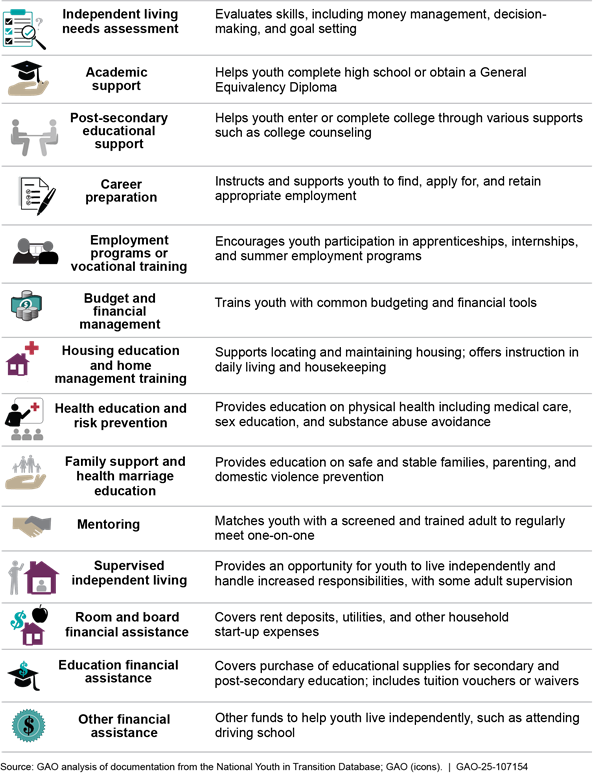

The independent living assessment and transition plan determine the services provided to individual youth among 11 service categories and three financial assistance categories (see fig. 3). Nationally, at least 103,000 youth received one or more independent living services in fiscal year 2022.[14]

Note: Certain services, such as mentoring, are only reportable to the National Youth in Transition Database if they are directly administered by the child welfare agency.

Nationally, the most widely received services were the independent living assessment, academic support, budget and financial management, and health education, according to NYTD data from fiscal year 2022. We found that common independent living services in our selected states were similar and were generally related to education, health, and housing. This included:

· Education support. Officials in three selected states confirmed that supporting youth in obtaining their high school diploma, a general equivalency diploma (GED), or postsecondary education was one of the most common services. According to California officials, they provide a range of educational support, including tutoring, weekly classes, and help applying to college.

· Health education. Officials in three selected states confirmed that health education was one of their most common services. In Kentucky, one program partners with an insurance company to provide health education and health insurance to all youth in foster care.

· Housing. Officials in three selected states confirmed that one of their most common services was housing assistance, such as housing advocacy services and help getting on a waitlist for housing.

In addition to independent living services, states used the Chafee ETV program to support youth pursuing postsecondary education. For example, Illinois officials told us their funds are mostly used for assistance with private or out-of-state colleges because in-state, public, or community college tuition and fees for youth in foster care are covered by a waiver in their state. In California, officials told us that the ETV grant is most commonly used at community colleges alongside other state support, such as a tuition waiver at certain state universities for youth currently or formerly in foster care.

Officials from selected states described different mechanisms for delivering Chafee services. These included offering in-person or virtual classes directly through child welfare agencies, operating drop-in centers, and partnering with service providers. For example, California officials told us many counties offer services through drop-in centers, each of which may have a different focus, such as academic tutoring or housing resources. Officials in Florida told us that throughout the state regional independent living specialists provide services to older youth, as well as specialized case management to youth who choose to stay in care over the age of 18.

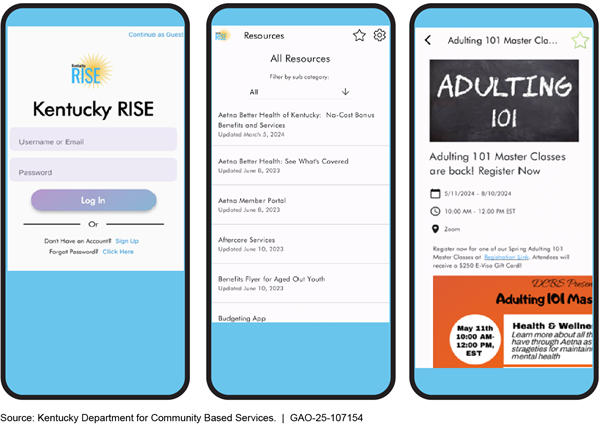

Officials from most selected states also told us that since the pandemic they are offering more services in a virtual or hybrid format to boost engagement. For example, Kentucky developed a phone application that officials described as a way for youth, foster parents, and department staff to locate information on Chafee services and to allow youth to communicate directly with their office (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Phone Application That Delivers Information

about Independent Living Services to Kentucky Youth

All selected states reported challenges in providing services to older youth, particularly low participation rates and limited access to transportation to receive services. For example, Kentucky officials said it is a challenge for youth in rural areas to access services, so they now offer online classes. California officials told us that getting youth to participate in services has always been a challenge because older youth may not trust institutions and therefore choose not to engage. Officials in one California county said the COVID-19 pandemic worsened this issue, citing ongoing mental health concerns and isolation. To combat the lack of participation, California invited youth ambassadors from over a dozen counties to work with their counties to improve participation rates and teach courses.

ACF Technical Assistance, Data, and Evaluations Can Be Used by States to Identify Effective Chafee Services, and ACF Has Efforts Underway to Improve These Resources

ACF provides a variety of resources that states can use to inform decision-making on effective programs and services for youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood, according to ACF officials and agency documentation. These resources include technical assistance, data, and evaluation projects. While officials in all six states told us they found ACF technical assistance helpful, they noted challenges in using data and evaluation projects to improve their programs. ACF has recognized these challenges and is taking steps to address them.

Technical Assistance

ACF primarily provides technical assistance to state child welfare agencies via its (1) regional offices, (2) Center for States, and (3) Child Welfare Information Gateway, according to ACF officials.

· ACF regional offices provide technical assistance and collaborative forums for states in their region on specific topics based on the region’s needs.[15] According to ACF officials, states may contact regional office staff for assistance on topics such as policies and procedures on allowable uses of Chafee funds, as well as information on other states’ Chafee programs. In addition, based on the needs of the states in the region, some regional office staff conduct monthly or quarterly calls with state Chafee program managers and service providers. Presenters share successes, lessons learned, and future opportunities to design products, services, research, and evaluations.

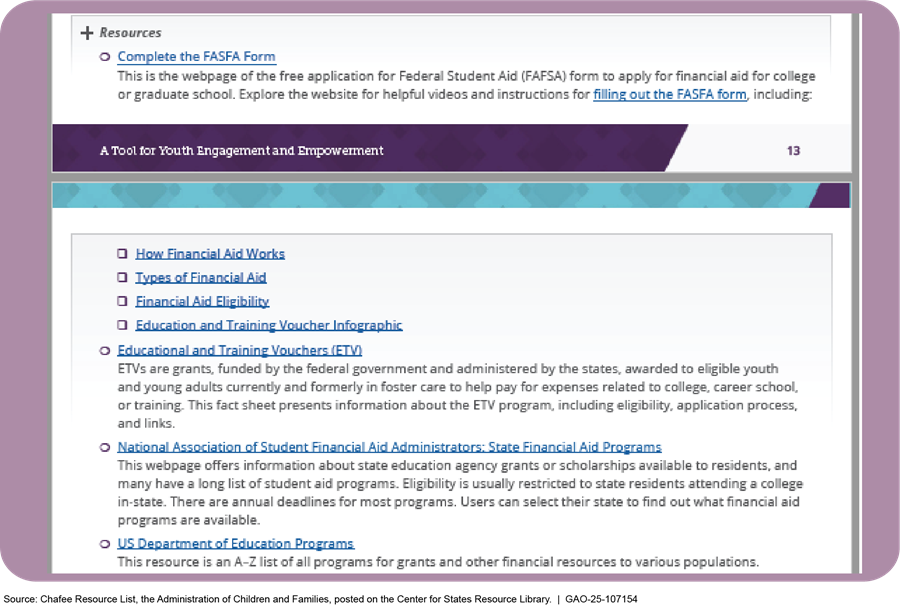

· The Center for States provides a range of technical assistance services to states, according ACF officials.[16] This may include training, coaching, curriculum development, data analysis, and individualized program consultation. For example, the Center is partnering with staff in one region to plan and co-facilitate bimonthly regional independent living services meetings on barriers, supports, solutions, and needs within the region. In addition, the Center offers opportunities for state Chafee coordinators to connect virtually with peers. States can also access a resource library that includes tip sheets, videos, and other resources on topics related to older youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood (see fig. 5).

Figure 5: Example of Chafee Program Resource Posted on ACF’s

Center for States Resource Library Webpage

· The Child Welfare Information Gateway is ACF’s resource library of publications, research, and learning tools. For example, state officials working with Chafee-eligible youth can search for resources in categories such as engaging and involving youth and young adults, or services and interventions for youth. The Gateway also includes a directory of contact information for state officials overseeing foster care, Chafee and ETV programs, as well as other state and community resources.

Officials from all six selected states reported that they had used one or more of the technical assistance resources and found them helpful. Officials in three states said support from their regional office staff was helpful. For example, officials in one state said their regional office staff provided guidance on using Chafee and ETV pandemic funding, such as how much pandemic funding could be spent on housing for youth.[17] Officials in one state said the Center for States facilitated field training in advocacy for their youth advisory board. Another state official told us the Gateway was helpful because legislation around Chafee is very broad and the Gateway has a repository of letters with previously answered questions from ACF.

National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD)

NYTD is another resource that ACF provides for states to inform decision-making on effective programs and services for youth. ACF officials told us they encourage states to use NYTD data to continuously improve programs and services. Since 2010, states have been required to submit NYTD data on independent living services provided by child welfare agencies. States also submit data to NYTD on the outcomes of certain Chafee-eligible youth as they transition to adulthood.[18] In addition, as part of their annual report to ACF, states must describe how they use NYTD and other data and research to improve Chafee service delivery and refine their program’s goals.

Officials in two selected states reported using NYTD data to inform their decision-making. Officials in one county told us that NYTD data was very useful to them, as they were able to incorporate it into their data analytics system. Combining their administrative data from various county agencies with NYTD data enabled them to better analyze outcomes for youth.

However, four of six state officials told us they faced challenges using NYTD data for decision-making, though their reasons varied. For example, officials in one state said that accurately entering data on services received was a challenge because caseworkers prioritize serving youth over entering information on the Chafee services that youth received into the state’s data system. Thus, services were likely underreported in their states, limiting its usefulness. Officials in one county said that the data were not timely enough to be useful to them, and that they preferred to rely on immediate feedback from youth and providers for programmatic decisions.

ACF officials acknowledged that NYTD data has limitations in helping to assess the performance of independent living services, and they are currently working to increase the usefulness of NYTD data. Officials told us they plan to create tip sheets on how states can combine NYTD data with other types of data. In addition, officials told us the NYTD dashboard is being updated to feature data visualization as well as information about data quality and compliance.[19] Finally, officials told us they are supporting and encouraging states in developing new comprehensive data systems for their child welfare programs. This will be an opportunity to design more streamlined and efficient ways for capturing NYTD services data and improve the accuracy of the data.

Evaluations

Since 1999, ACF has completed two large-scale evaluations of Chafee independent living programs and have started work on a third (see fig. 6). ACF’s previous evaluation work found that large-scale traditional impact evaluations were generally not feasible for many Chafee-funded programs due to issues such as small program size and lack of appropriate comparison groups. There were also implementation challenges such as youth participation. Therefore, there is limited information on which programs and services have been shown to be effective at helping youth successfully transition from foster care to adulthood.

Figure 6: Evaluations of Chafee-Funded Programs by ACF’s Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation

ACF told us they expected that states would consider the information from these ongoing studies as part of their overall evidence base. However, officials in three selected states told us that since there is such limited research on effective programs that serve youth transitioning into adulthood, this is not something they are able to use to determine which services to offer. For example, officials in one state told us they spend a lot of time doing their own research on best practices and which programs are effective, since this information is not generally available. These officials said they have tried to consult research clearinghouses for information on programs, but the research process is too slow, and the list of relevant programs is very limited.[20]

ACF’s current Chafee evaluation, the Strengthening Outcomes for Transition to Adulthood project, launched in late 2021.[21] According to ACF officials, it is designed to address the common challenges identified in ACF’s previous work and broaden the pool of interventions that can be evaluated. They plan to do this by using design methods that they believe are better suited to evaluate these types of programs.[22]

Selected States Spent More Than Required on Programs for Youth Transitioning from Foster Care to Adulthood, While Nationally, Some Federal Funds Went Unspent

Selected States Used More State Funding Than Required on Their Chafee Programs But Youth Continued to Have Unmet Needs

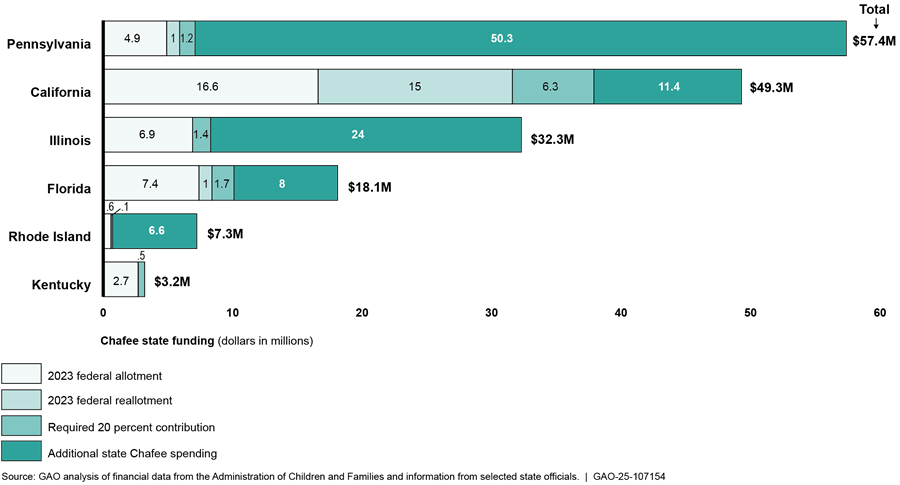

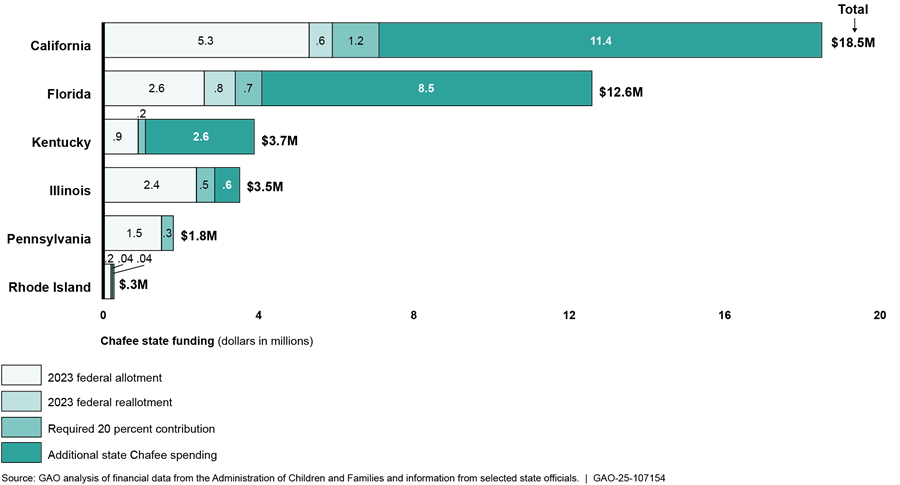

Officials from all six selected states said they contributed significant state and local funding to support programs for youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood, beyond the required 20 percent match. In four states, officials told us that state funds made up the majority of funding for services for Chafee-eligible youth (see fig. 7). In addition, officials in three states told us state funds made up the majority of funding for their ETV programs (see fig. 8).

Figure 7: Selected States’ Chafee Federal Allotment and State Spending on Chafee Programs, Fiscal Year 2023

Note: State spending is self-reported and may also include local contributions. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Figure 8: Selected States’ Chafee Federal Allotment and State Spending on Chafee Education and Training Vouchers (ETV), Fiscal Year 2023

Note: State spending is self-reported and may also include

local contributions. Chafee Education and Training Voucher (ETV) grants support

youth attending an institution of higher education. Numbers may not sum due to

rounding.

Selected states described a variety of initiatives funded solely or in large part with state funds to support this population. Officials in Illinois said that if a youth needed a particular service, they generally tried to provide it, regardless of whether they could use federal funds. For example, officials told us they used state funds to heavily subsidize an employment-incentive program, in which eligible youth can receive a monthly payment of $174 if they are employed or part of a job training program. Officials from Florida told us their state funds an emergency assistance program to help older youth with one-time urgent expenses such as housing security deposits.

Selected states also described a variety of state-funded initiatives to support postsecondary education for older youth. Officials in Kentucky told us they provided a tuition waiver for all eligible youth in foster care to any public college or university in the state. Officials in one California county described how they support youth going to college by having their caseworker accompany them on the trip, and by providing dorm room essentials such as linens, laundry supplies, and desk lamps.

Officials from all six selected states told us they have unmet needs in serving this population, often related to housing and postsecondary tuition. Further, officials said that if they had additional funds, they would direct them to these categories. For example, officials in Rhode Island told us that the increase in housing costs has been higher in Rhode Island relative to other states. While they have developed partnerships with different programs and housing authorities throughout the states, they said they still struggle to support older youth in affording their housing arrangements. Officials in California told us that they are not able to award the full $5,000 ETV amount to all eligible youth due to insufficient funding and instead provide approximately $3,500 per youth annually.

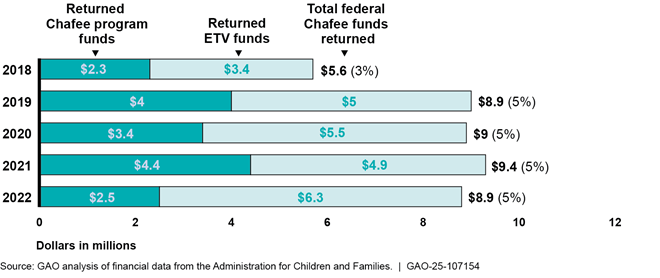

Nationally, States Did Not Spend All Available Federal Funds for Programs Serving Older Youth and ACF Did Not Identify Reasons or Potential Solutions

We found that states did not always spend all available federal funding. This was true nationally and for three of six selected states. According to our analysis of ACF financial data, states returned an average of about 5 percent of Chafee and ETV federal funds between fiscal years 2018 and 2022 (see fig. 9). These returned funds represented an average of about $8.4 million per year. In fiscal year 2022, 12 of 51 states returned Chafee funds, and 28 states returned ETV funds for a total of about $8.9 million.[23] In addition, the Congressional Research Service has reported on states returning federal Chafee and ETV funds since at least fiscal year 2007.[24]

Note: This does not include additional COVID-19 pandemic funds provided in fiscal year 2021. Chafee Education and Training Voucher (ETV) grants support youth attending an institution of higher education. The number of states includes the District of Columbia. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

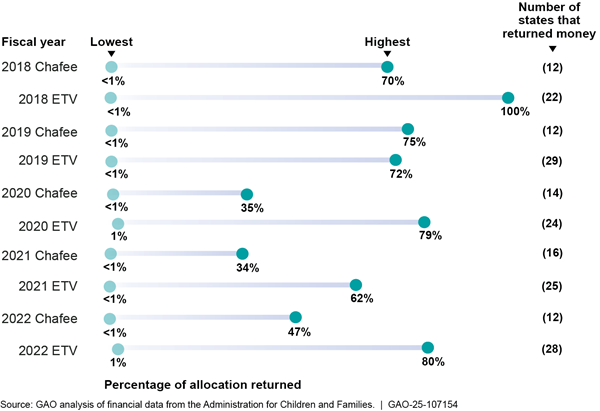

The percent of returned funds each fiscal year ranged widely, with states in some cases returning less than 1 percent and in other cases returning the majority of their allocation (see fig. 10).

Figure 10: Range of Chafee and Education and Training Voucher (ETV) Program Funds Returned by States, Fiscal Years 2018–2022

Note: This does not include additional COVID-19 pandemic funds provided in fiscal year 2021. Chafee Education and Training Voucher (ETV) grants support youth attending an institution of higher education. The number of states includes the District of Columbia. Percentages have been rounded to the nearest whole number. We excluded returned funds of less than $1.

Selected states described a variety of challenges with spending their full

Chafee federal allotment. For example, officials from one state said in

previous years, they did not always know they had funds remaining until they

started having regular meetings between their state financial and program

teams. Officials from another state told us they had delays getting invoices

from contractors and they sometimes did not realize they had a balance until it

was too late to spend it. Officials in one county told us they find it

challenging to spend their full funding because of inadequate staffing and

lengthy unfilled vacancies for staff serving older youth. Similarly, ACF

officials told us that reasons for state underspending included staff turnover,

delays in state and county procurement processes, and issues with contracts

such as serving fewer participants than budgeted for.

As previously described, ACF may redistribute Chafee funds to other states if funds are not expended within a 2-year period and states have approximately one year to spend redistributed funds. In fiscal year 2023, 32 states received reallocated Chafee program funds, with amounts ranging from $35,000 to $15 million, according the ACF data.[25] In addition, 16 states received reallocated ETV funds with amounts ranging from $50,000 to $1.8 million. Three of our selected states applied for and received reallocated funds in fiscal year 2023 to support services for older youth. For example, California used this process to double their federal Chafee funding from $16.6 million to $31.6 million.

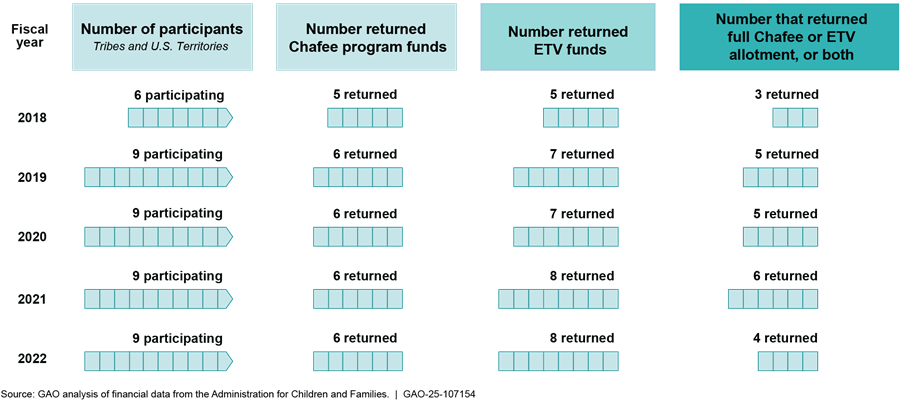

Participating Tribes and U.S. territories also did not spend all of their federal Chafee funds, according to ACF data. Between fiscal years 2018 and 2022, Tribes and U.S. territories often returned 100 percent of their allocation (see fig. 11). In fiscal year 2022, five Tribes and U.S. territories returned at least 60 percent of their Chafee and ETV allocations. Overall, Tribes and U.S. territories returned a total of about $640,000 in fiscal year 2022, 38 percent of the total.

Figure 11: Number of Participating Tribes and U.S. Territories Returning Federal Chafee and Education and Training Voucher (ETV) Funds, Fiscal Years 2018–2022

Note: This does not include additional COVID-19 pandemic funds provided in fiscal year 2021.

ACF officials said they have discussed spending challenges with participating Tribes and U.S. territories as part of their ongoing planning and technical assistance activities. They told us that because Tribes and U.S. territories have smaller populations of eligible youth and fewer staff, fully spending the funds may be more difficult. For example, a Tribe may plan to serve a certain number of young people, but small fluctuations in the number of eligible youth needing services can result in significant portions of their grants not being used. Similarly, turnover in one key staff position may affect their ability to offer services, leading to underspending.

ACF officials told us they work to ensure federal Chafee allocations are fully spent by reallocating unspent funds to jurisdictions that request it. Further, officials said they prefer to direct their resources to assisting and encouraging jurisdictions to apply for unspent funds instead of working directly with the states that have unspent funds to address underspending. This is because reallocations help to ensure funds remain available to meet the needs of older youth nationally, even if not used by the state originally allocated the funds. However, despite the reallocation process, a total of about $670,000 in federal Chafee funds ultimately went unused and were returned to the U.S. Treasury in fiscal year 2022, according to ACF officials.[26]

Officials told us that before 2018, when funds could not be reallocated, they worked with jurisdictions to encourage full spending of their allotments in future years. They said that this was helpful in some years but not in others, based on the amount of money that was ultimately returned.

Although ACF discontinued the practice of contacting jurisdictions to discuss unspent Chafee funds, officials told us in April 2024 that they plan to reinstate it. Specifically, ACF officials told us they plan to send regional offices information on which states, Tribes, and U.S. territories returned funds. Regional staff would be expected to follow up with the jurisdictions to discuss any challenges that may have led to underspending and provide guidance on how to help jurisdictions address these challenges. As of October 2024, ACF did not have a documented plan to implement this initiative, nor have officials communicated this plan to regional offices. ACF officials said they would begin this process soon, but they have not yet done so due to competing priorities.

The objective of the Chafee program is to support youth in or formerly in foster care in their transition to adulthood. Federal standards for internal control specify that agencies should communicate to external entities the necessary quality information to allow them to achieve their objectives.[27] In addition, ACF has a strategic goal to advance equity by (1) identifying and closing gaps in program outcomes for historically underserved or marginalized populations across all ACF programs, and by (2) eliminating systemic barriers to funding access that applicants to grants and contracts face.[28] Youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood are disproportionately from low-income families and historically underserved groups.[29] In addition, in 2015 we reported that Tribal child welfare agencies may face unique geographical, resource, or other challenges to serving youth in foster care.[30]

By following through with its plan to have regional offices proactively work with participating states, Tribes, and U.S. territories to identify any funding barriers, and providing guidance to address those barriers, ACF can better ensure the Chafee program meets its objective to support youth in or formerly in foster care in their transition to adulthood. Eliminating barriers to funding access could improve the services states, Tribes, and U.S. territories offer to older youth.

Conclusions

The Chafee program is an important part of efforts to serve youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood who face many challenges. ACF provides information to states on how to identify effective programs for this population and is currently updating those resources.

ACF also provides funding to states, Tribes, and U.S. territories to support youth in this transition. However, federal funds for this program have gone unspent for several years despite states reporting many unmet needs. In some cases, Tribes and territories have returned all their federal Chafee program funds, although those communities may be historically underserved and face other unique challenges. Having regional staff proactively work with jurisdictions to identify and address reasons for unspent federal Chafee funds could help ensure all federal funds for services for youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood are used.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Secretary for Health and Human Services should ensure the Administration for Children and Families documents a plan to have regional offices work with states, Tribes, and U.S. territories to address any barriers they face in spending federal Chafee funds and ensure the plan includes guidance on how regional office staff can help jurisdictions address these challenges.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. The agency concurred with our recommendation, and also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. HHS said the agency will develop a plan to share information with regional offices on states, Tribes, and U.S. territories spending of Chafee funds. In addition, HHS said regional offices will use this information to reach out to relevant states, Tribes, and U.S. territories to discuss reasons for underspending and provide technical assistance.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and to the Department of Health and Human Services. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7215 or larink@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Kathryn A. Larin, Director

Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues

As part of COVID-19 pandemic relief efforts, states were appropriated an additional $400 million in Chafee funds in fiscal year 2021. According to ACF, the goal of providing these additional funds was to help older youth recover from the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing public health emergency. These funds had temporary flexibilities compared to regular annual Chafee funds. For example, states were able to use more than 30 percent of the Chafee grant funds for room and board, which is the cap in other years.

About $50 million in pandemic funding was unused by the deadline. According to our analysis of ACF financial data, 29 of 51 states returned Chafee pandemic funds, and 25 returned ETV funds (see table 1). ACF officials told us they heard from states that they were not able to spend the full amount due to delays in gaining authority from state legislatures and the time needed to complete state procurement processes.

Table 1: State Returns of Federal Pandemic Chafee and Education and Training Voucher (ETV) Program Funds, Allotted in Fiscal Year 2021

|

Number of states that returned Chafee funds |

Amount of Chafee funds returned |

Number of states that returned ETV funds |

Amount of ETV funds returned |

Total Chafee pandemic funds returned |

|

29 |

13 percent |

25 |

10 percent |

13 Percent |

Source: GAO analysis of financial data from the Administration for Children and Families. | GAO‑25‑107154

Note: The number of states includes the District of Columbia. Amounts have been rounded to the nearest whole number.

Of the nine Tribes and U.S. territories that received pandemic funds, eight returned some portion of them: about $696,000, or 21 percent of the total (see table 2).

Table 2: Participating Tribes and U.S. Territories Returns of Federal Pandemic Chafee and Education and Training Voucher (ETV) Funds, Allotted in Fiscal Year 2021

|

Number of Participating Tribes and U.S. Territories that returned Chafee funds |

Amount of Chafee funds returned |

Number of participating Tribes and U.S. Territories that returned ETV funds |

Amount of ETV funds returned |

Total Chafee pandemic funds returned |

|

7 of 9 |

16 percent ($467,866) |

8 of 8 |

58 percent ($227,863) |

21 percent ($695,729) |

Source: GAO analysis of financial data from the Administration for Children and Families. | GAO‑25‑107154

Note: Amounts have been rounded to the nearest whole number.

Selected states described a variety of initiatives funded with additional pandemic funds. Officials in Kentucky said they used part of the funding to create an app that allows easy access to services, events, and general information for older youth in foster care. Officials in Rhode Island told us they used the additional funds to provide rent relief for youth, including paying back rent, security deposits, moving costs, furniture, and utilities. Officials in both Pennsylvania and California told us they used the money to provide direct payments to older youth to cover basic needs.

Five of six selected states returned part of their additional pandemic funds. Officials in most selected states said the additional pandemic money was helpful in addressing pandemic-induced needs for older youth but they struggled to spend it all in the limited timeframe. For example, officials in California told us that they had not administered direct payments to youth before, and there was a long learning curve in setting up and executing the payments.

Because about $50 million in pandemic funds were returned and available for redistribution, fiscal year 2023 allotments were higher than usual, totaling about $191 million for the Chafee program and about $51 million for ETV grants.

GAO Contact

Kathryn A. Larin, Director, (202) 512-7215 or larink@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Andrea Dawson (Assistant Director), Alexandra Squitieri (Analyst-in-Charge), Vernette G. Shaw, and Christina Liu Puentes made key contributions to this report. Charlotte Cable, Alicia Cackley, Elizabeth Calderon, Serena Lo, and Mimi Nguyen provided additional support.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]See GAO, Foster Care: States with Approval to Extend Care Provide Independent Living Options for Youth up to Age 21, GAO‑19‑411 (Washington, DC.: May 21, 2019) and Mark Courtney, Michael Pergamit, Marla McDaniel, Erin McDonald, Lindsay Giesen, Nathanael Okpych, and Andrew Zinn, Planning a Next-Generation Evaluation Agenda for the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program, OPRE Report #2017-96, (Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017).

[2]For the purposes of this report, we use the term “Tribes” to refer to federally recognized Indian Tribes. Federally recognized Tribes have a government-to-government relationship with the United States and are eligible to receive certain protections, services, and benefits by virtue of their status as Indian Tribes.

[3]For the purposes of this report, we use the terms “youth” and “older youth” to refer to youth in foster care who are eligible for the Chafee program. Populations who are eligible for the program, as outlined in federal law, include youth in foster care, ages 14 and older; young people in or formerly in foster care, ages 18 to 21, or 23 in some jurisdictions; youth who left foster care through adoption or guardianship at age 16 or older; and youth “likely to age out of foster care.” Eligible older youth can receive assistance to participate in age-appropriate and normative activities.

[4]States have 2 years to spend this allocation.

[5]Approximately 370,000 youth were in foster care as of September 30, 2022, according to ACF data.

[6]The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Fostering Youth Transitions 2023: State and National Data to Drive Foster Care Advocacy (City, State, if available: 2023). According to the report authors, the estimate of 444,348 for fiscal year 2021 should not be regarded as an exact calculation due to limitations in the public data, such as masking of children’s date of birth. We are reporting a rounded estimate to account for potential undercounting and overcounting, as well as state variation in how they continue to support or track individuals in foster care and others who are Chafee-eligible once they turn 18.

[7]Tribes with a Tribe-state agreement for receipt of certain federal foster care funding and Tribes approved by ACF to directly operate their own foster care program are eligible to receive Chafee and/or ETV funding directly from ACF. Some Tribes may prefer to enter into an agreement with a state agency or have the state agency provide services to Tribal children. Between fiscal year 2018 and 2022, between four and seven Tribes received Chafee and/or ETV funding.

[8]The Family First Prevention and Services Act granted HHS the ability to redistribute unexpended funds.

[9]ACF collects data on state spending to ensure compliance with the 20 percent match requirement and does not have information on state spending beyond this, according to agency officials.

[10]The 5-year plan is known as a Child and Family Services Plan. The annual report is known as an Annual Progress and Services Report.

[11]Foster Care Independence Act of 1999, Pub. L. No. 106-169, 113 Stat. 1822, 1828.

[12]California’s child welfare system is county administered, meaning counties have flexibility in determining the specific services that comprise their Chafee programs.

[13]Federal law requires states to assist and support youth with developing transition plans 90 days before they age out of care. 42 U.S.C. § 675(5)(H).

[14]This estimate is from ACF’s National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD). In 2019, we reported that NYTD was insufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report on independent living options for older youth in foster care due to concerns about the completeness of the data (see GAO‑19‑411). In that report, stakeholders, including ACF officials, said that NYTD data may be incomplete since use of independent living services are underreported. More recently, ACF officials told us the data likely do not reflect all services received by older youth because youth may be receiving services from contracted independent living service providers, caseworkers, and/or other child welfare agency staff. We are including limited fiscal year 2022 NYTD data in this report as context. However, it does not form the basis of our conclusions.

[15]ACF’s Office of Regional Operations has 10 regional offices that serve states, territories, Tribes, and other grantees throughout the U.S.

[16]The Center for States is part of the Child Welfare Capacity Building Collaborative, which is run through ACF. It is a partnership of three centers: the Center for States, the Center for Tribes, and the Center for Courts.

[17]See app. I for additional information on Chafee funds allocated in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

[18]States collect NYTD outcome information by surveying eligible cohorts of youth at ages 17,19, and 21. The survey includes questions to assess youth’s financial self-sufficiency, experience with homelessness, educational attainment, positive connections with adults, high-risk behavior, and access to health insurance.

[19]ACF expects the system updates to be completed by spring 2025.

[20]There are research clearinghouses with publicly available information on the effectiveness of child-welfare programs and services, such as the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse and the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare.

[21]ACF is also sponsoring other research relevant to this population. This includes the Child Welfare Evidence Strengthening Team, which is evaluating LifeSet, an intensive case management program for youth with behavioral challenges, as well as programs that provide housing vouchers and substance-use treatment for families involved in the child welfare system. Officials at ACF told us that states may also find information on employment-related interventions for youth ages 16-24 in ACF’s Pathways to Work Evidence Clearinghouse.

[22]For example, ACF officials said that to overcome small sample sizes, they may employ single case design methods, utilize administrative data from a larger pool of potential sample members to supplement main impact study findings, or use statistical methods to report the probability that the service has an impact on specific outcomes.

[23]In this section, we use the term “states” to refer to the 50 states and the District of Columbia. We discuss U.S. territories and Tribes receiving Chafee funding later in the section.

[24]See Congressional Research Service, Youth Transitioning from Foster Care: Background and Federal Programs, RL34499, Washington, D.C.: May 29, 2019). States also returned federal Chafee funds that were allocated in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. See app. I for more information.

[25]Fiscal year 2023 allotments were higher than usual because about $50 million in 2021 pandemic funds were returned and available for redistribution. See app. I for more information.

[26]The majority of this funding was for the ETV program.

[27]See GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G. (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2014).

[28]See Administration for Children and Families, Strategic Plan, January 2022.

[29]See Administration for Children and Families, Child Welfare Practice to Address Racial Disproportionality and Disparity, April 2021.

[30]See GAO, Foster Care: HHS Needs to Improve the Consistency and Timeliness of Assistance to Tribes, GAO‑15‑273. (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 2015).