U.S. PORT INFRASTRUCTURE

DOT and DHS Offer Funding and Other Assistance Ports Can Use to Improve Disaster Resilience

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Andrew Von Ah at (202) 512-2834 or vonaha@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107159, a report to congressional committees

DOT and DHS Offer Funding and Other Assistance Ports Can Use to Improve Disaster Resilience

Why GAO Did This Study

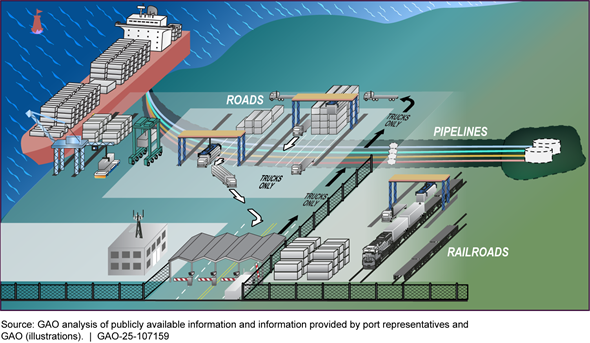

Over 300 American coastal, Great Lakes, and inland water-side ports are critical to national and local economies, handling over $2.28 trillion of U.S. international trade in 2022. Freight that arrives at a port reaches its final destination using “landside connectors” – transportation systems such as roads and pipelines (see figure). Each year, ports are affected by natural disasters such as floods and hurricanes, which can disrupt the global supply chain.

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for GAO to review federal efforts to assist ports in enhancing the resilience of port infrastructure to weather-related disasters. This report describes (1) how DOT and DHS consider disaster resilience when awarding funds to ports and the extent funded projects have improved port disaster resilience; and (2) federal efforts to assist port authorities with identifying vulnerabilities and improving resilience.

To address these objectives, GAO interviewed DOT and DHS officials and representatives from two port associations and seven selected ports, including site visits to ports located in Louisiana and Mississippi. GAO selected ports based on their level of freight traffic and location. Views obtained from ports are not generalizable. In addition, GAO reviewed guidance and notices of funding opportunities for seven federal grant programs that DOT and DHS identified as relevant. GAO also reviewed federal guidance for conducting risk assessments and disaster resilience frameworks.

What GAO Found

The Departments of Transportation (DOT) and Homeland Security (DHS) have provided funding opportunities to ports and their surrounding communities through various grants. For seven such grant programs, GAO identified grant selection criteria in 2024 related to natural disaster resilience in recent funding notices for the five competitive programs that used these types of notices. GAO found the extent that the federally awarded projects at ports improved natural disaster resilience is not fully known. According to DOT and DHS officials, a key reason for this is that port projects often result in increased resilience against natural disasters, even if they have a different primary goal such as combatting terrorism or addressing cybersecurity. For example, one of GAO’s selected ports received a grant to relocate a security checkpoint gate and install a new gate operating system. In doing so, port representatives said the gate was moved away from a flood zone, thus increasing resilience against flooding. Officials added that the statutes authorizing federal funding programs do not require the federal agencies to track whether funded projects improved disaster resilience.

Federal agencies have developed several resilience related frameworks and risk assessment guidance that ports and stakeholders could use to identify natural disaster vulnerabilities and improve port resilience. Some guidance is for port authorities to enable them to score their port’s resilience, while other guidance is for entire communities that may include a port. Ports may choose whether to use federal guidance and tools to create risk assessments. Of the seven port authorities GAO spoke with, five had assessed and documented risks for various reasons. For example, representatives from a coastal port that is affected by hurricanes told GAO they conduct a risk assessment to identify vulnerabilities and determine operational resilience, and for insurance purposes. Representatives from another coastal port said that their plan lists operating procedures based on the severity of an earthquake, since that is their biggest natural hazard. Federal agencies have also established multiple coordination mechanisms and provide training opportunities to ports and their stakeholders that might improve resilience.

Abbreviations

|

CISA |

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency |

|

CMTS |

U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

MARAD |

Maritime Administration |

|

NOAA |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

|

NOFO |

Notice of Funding Opportunity |

|

NSM-22 |

National Security Memorandum 22 |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

March 20, 2025

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

U.S. ports are critical to national and local economies. According to the Department of Transportation (DOT), over 300 American coastal, Great Lakes, and inland waterside ports handled over $2.28 trillion of U.S. international trade by value in 2022.[1] Freight that arrives at a port reaches its final destination using “landside connectors”—that is, transportation systems such as roads, railways, and pipelines. The federal government has a vested interest in the resilience of ports and their landside connectors, to ensure that goods move reliably through the supply chain.[2]

Disruptions at ports, such as natural disasters, can create congestion and economic hardship, with cascading effects on the national and global supply chain. Each year, natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, and earthquakes affect hundreds of U.S. communities—including those surrounding ports. The U.S. Global Change Research Program projects certain extreme weather events to become more frequent and intense in parts of the U.S. The rising number of natural disasters and increasing reliance on the federal government for assistance is a key source of federal fiscal exposure. Accordingly, “Limiting the Federal Government’s Fiscal Exposure by Better Managing Climate Change Risks” has been on our list of high-risk federal program areas since 2013.[3] The complexity of port operations and their landside connectors makes improving resilience to natural disasters difficult.

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for us to review federal efforts to assist ports in enhancing the resilience of port infrastructure to weather-related disasters.[4] This report describes (1) how DOT and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) consider disaster resilience when awarding funds to ports, and the extent to which funded projects have improved port resilience against natural disasters; and (2) federal efforts to assist port authorities with identifying vulnerabilities to natural disasters and improving resilience of port infrastructure.

For both objectives, we focused primarily on the efforts of DOT and DHS, because these agencies have a role in strengthening the resilience of critical transportation infrastructure, including ports and their landside connectors.[5] We reviewed relevant guidance, policies, plans, agreements, reports, and other documentation from DOT, DHS, and the U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System (CMTS) pertaining to improving resilience of ports and their landside connectors against natural disasters. We interviewed agency officials from DHS, including the Coast Guard, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). We also interviewed officials from DOT, including the Maritime Administration (MARAD), the Office of the Secretary, and the Office of Multimodal Freight Infrastructure and Policy. Other DOT operating administrations provided written input on our review, including the Federal Highway Administration, the Federal Railroad Administration, and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. Additionally, we reviewed relevant background documentation from nonfederal entities such as the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine.[6] This report is based on audit work and federal government actions as of December 2024 and references federal policies that may have been rescinded, replaced, or amended.

We also interviewed nine nonfederal entities, including representatives from seven selected ports and two associations representing ports.[7] We selected ports that vary in terms of location, risks of natural disasters, and freight activity. Specifically, we selected ports (1) from across the U.S., with a focus on balancing the number of coastal and inland ports; (2) located in states with a high number of natural disasters, as reported by FEMA from 2019 through 2024; and (3) that varied in freight activity and traffic, as reported by DOT and Army Corps of Engineers. Our report provides perspectives from a range of ports, but these views are not generalizable to all ports. We selected industry associations that represent coastal and inland ports, and that had participated in our prior work on ports.

To describe how DOT and DHS consider disaster resilience when awarding funds to ports, and the extent to which funded projects have improved port resilience, we first asked knowledgeable DOT and DHS officials to identify the discretionary grant programs they deemed relevant to our review. They identified seven grant programs that we determined fit within our scope.[8] For those grant programs, we then analyzed award data, guidance, and notices of funding opportunities from fiscal year 2019 through the most recent year available, which was either fiscal year 2023, 2024, or 2025. Using grant notices of funding and guidance, we determined how the agencies considered natural disaster resilience in the grant awarding process, and whether they documented if funded projects improved port resilience against natural disasters.

In discussions with DOT and DHS officials about the extent to which their grant programs had improved port resilience against natural disasters, we determined we would not be able to quantify the amount or percentage of federal funding specifically targeted to improve natural disaster resilience. Therefore, we asked the agencies to identify relevant examples of awarded projects that could have improved port resilience against natural disasters. Additionally, we discussed how port representatives may have considered resilience against natural disasters when applying for these grant programs.

To identify other federal funding opportunities that were potentially relevant to ports, landside connectors of ports, or natural disaster resilience improvement, we reviewed CMTS’s Federal Funding Handbook for the Marine Transportation System.[9] We also interviewed CMTS officials about efforts to include, describe, and categorize federal funding in the handbook. For additional information on these funding opportunities, see appendix I.

To describe federal efforts to assist port authorities with identifying vulnerabilities of port infrastructure to natural disasters, we reviewed guidance discussed in interviews with CMTS and agency officials. This guidance included CISA’s Marine Transportation System Resilience Assessment Guide, as well as the CMTS tool matrix, which provides a list of relevant federal and nonfederal guidance for improving port resilience. We also reviewed a number of frameworks, including the National Climate Resilience Framework,[10] the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit,[11] the National Infrastructure Protection Plan,[12] the National Disaster Recovery Framework,[13] and the National Mitigation Framework.[14] We reviewed the requirements for DOT and DHS related to assessing risks to critical infrastructure and coordination contained in National Security Memorandum 22 (NSM-22).[15] Furthermore, we interviewed the previously mentioned agency officials and port representatives to gather their experiences and opinions about currently available federal guidance.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

According to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, ports are commonly recognized as places where cargo is transferred between ships and trucks, trains, pipelines, storage facilities, or refineries. More than 300 waterside ports are located across the U.S., not only along the coasts but also along inland waterways and the Great Lakes. Many waterside ports are governed by port authorities—governmental entities that either own or administer the land or facilities at the port. Port authorities can be an independent entity organized under state law, part of a local or state government, or an interstate authority. Terminal operators at ports may be the port authority itself, or private companies that lease the terminal.

Port operations require coordination among port authorities or other management entities, terminal operators, ocean carriers, shippers, cargo owners, railroad operators, pipeline operators, and motor carriers to efficiently move freight from vessels to ground transport for distribution. In this document, we refer to the railways, roads, and pipelines connecting ports to ground transportation systems as landside connectors (see fig. 1).

Entities that manage port operations and facilities, such as a port authority, handle activities related to ensuring the resilience of their port operations against natural disasters. Ports generally undertake such activities in coordination with a variety of stakeholders. For example, state and local governments are important players in port governance and in overseeing projects that may affect ports. Entities involved in decision-making may include private corporations, such as terminal lessees or owners; regional, state, or local authorities; divisions of state, county, or municipal governments; and independent port or navigation districts, including port authorities.

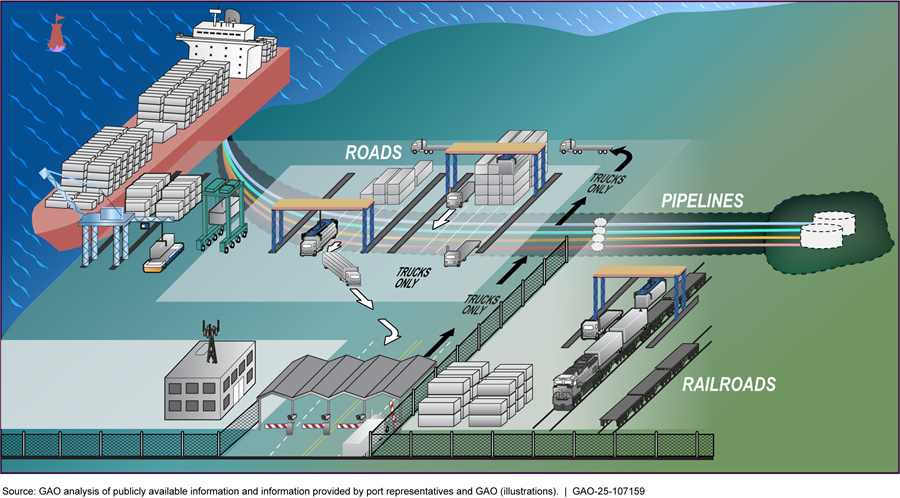

While DOT and DHS generally do not have a role in port ownership and operations, they do support ports through other means, including by providing guidance, participating in training exercises, and providing funding for infrastructure projects (see fig. 2). DOT and DHS officials told us there are no federal statutes authorizing any of their agencies to take responsibility for the disaster resilience of ports or their landside connectors. DOT officials said their role is primarily to advise port stakeholders and provide grant funding. DHS officials said their role primarily concerns ensuring security for waterways into and out of ports and preventing acts of terrorism to protect port infrastructure.

Note: DOT operating administrations have roles related to landside connectors. Through the Federal Highway Administration, DOT works with states to ensure the safety and mobility of the highway transportation network, which serves trucks carrying cargo containers to and from marine terminals. Through the Federal Railroad Administration, DOT works to enable the safe, reliable, and efficient movement of people and goods. Through the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, DOT sets the federal minimum safety standards for pipelines and the movement of other hazardous materials.

We and others have recommended enhancing resilience to help limit the federal government’s fiscal exposure to climate change, because doing so can reduce the need for far more costly steps in the future. Enhancing climate-related resilience means taking actions to reduce potential future losses by planning and preparing for possible climate hazards, including natural disasters. For example, in 2015 we recommended developing a national climate information system.[16] Additionally, in 2020, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine recommended that the federal government (1) build an understanding of the supply chain through mechanisms such as assessment frameworks; (2) support coordination efforts; and (3) provide training on topics such as best practices.[17]

DOT and DHS officials identified seven grant programs that may fund natural disaster resilience projects for ports and their landside connectors as being relevant to our review, as shown in table 1. Of these programs, five provide funding on a competitive basis, with agencies selecting awardees based on assessments of applications against criteria published in the program’s notice of funding opportunity, including any applicable statutory criteria. Additionally, Congress can identify specific projects to receive funding from authorized grant programs to improve port resilience against natural disasters through Congressionally Directed Spending and Community Project Funding. See appendix I for other funding opportunities that could potentially improve port resilience.

Table 1: Grant Programs Identified by DOT and DHS in 2024 That May Fund Projects to Improve the Resilience of Ports and Their Landside Connectors Against Natural Disasters

|

Agency |

Grant name |

Funds available in fiscal year 2023 |

Description |

|

Department of Transportation |

Port Infrastructure Development Program |

Up to $662 million |

Assists in funding projects that improve the safety, efficiency, or reliability of the movement of goods through ports and intermodal connections to ports. |

|

|

Infrastructure for Rebuilding America |

Combined $3-3.1 billion for fiscal years 2023-2024 |

Funds projects that help protect the environment and improve the safety, efficiency, and reliability of infrastructure critical to the movement of freight and people in and across rural and urban areas; and that enhance the resilience of critical highway or freight infrastructure to help protect the environment. |

|

|

Rebuilding American Infrastructure with

Sustainability and Equitya |

$2.3 billion |

Funds capital investments in surface transportation infrastructure that will have a significant local or regional impact. |

|

Department of Homeland Security |

Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities |

$1 billion |

Funds hazard mitigation activities to reduce risks from disasters and natural hazards, with a recognition of growing hazards associated with climate change and the need for mitigation activities that promote climate adaptation and resilience. |

|

|

Flood Mitigation Assistance |

$800 million |

Funds projects and activities that aim to reduce or eliminate the risk of repetitive flood damage to buildings insured under the National Flood Insurance Program and within program-participating communities. |

|

|

Hazard Mitigation Grant Program |

Funding amount is determined after each presidential disaster declaration |

Funds planning and implementation of hazard mitigation measures that reduce the risk of loss of life and property from future natural disasters during the reconstruction process following a disaster. |

|

|

Pre-Disaster Mitigation |

$233 million for 100 congressionally directed projectsb |

Funds Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending projects for state, local, tribal, and territorial government efforts. Members of congress request provisions designating an amount of funds for particular projects, for example, to reduce the risk to individuals and property from future natural hazards, while also reducing reliance on federal funding for future disasters. |

Source: GAO summary of applicable laws and regulations, and Departments of Transportation (DOT) and Homeland Security (DHS) grant program notices of funding opportunities as of December 2024 and officials. | GAO‑25‑107159

Note: All the grant programs listed in the table except the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and the Pre-Disaster Mitigation grant program received additional funding through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Pub. L. No. 117-5, 135 Stat. 429 (2021).

aFor the purpose of our report, we used the name of the program during the time of our review. This program has been named the Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development program before and after our review.

bA previous iteration of the Pre-Disaster Mitigation grant program was competitive. However, funding for the program in fiscal years 2022, 2023, and 2024 was congressionally directed.

DOT and DHS Consider Disaster Resilience When Awarding Grants, but the Extent to Which Projects Improved Resilience Is Not Fully Known

DOT and DHS Evaluate Grant Applications Using Disaster Resilience Criteria

For the five grant programs we reviewed that are competitive, DOT and DHS considered natural disaster resilience in the latest round of funding when evaluating grant applications. In general, the agencies changed how they considered resilience over the period of our review, as described in table 2. The two non-competitive DHS programs we reviewed that are not included in table 2—the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and the Pre-Disaster Mitigation Program—also help address the risks posed by natural disasters or hazards, as directed by statute.

Table 2: DOT and DHS Consideration of Natural Disaster Resilience for Awarding Competitive Grants in Fiscal Year 2019 and the Latest Round of Funding

|

Agency |

Grant program |

Consideration of natural disaster resilience for fiscal year 2019 or first year fundinga |

Consideration of natural disaster resilience for recent rounds of fundingb |

|

DOT |

Port Infrastructure Development Program |

Not explicitly considered in the fiscal year 2019 notice of funding opportunity (NOFO). |

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 added a provision to the program’s authorizing statute requiring DOT to “give substantial weight” to “a port’s increased resilience as a result of the project” when selecting projects.c In the fiscal year 2024 NOFO, port resilience is included as one of four statutory merit criteria. Port resilience includes “the ability to anticipate, prepare for, adapt to, withstand, respond to, and recover from operational disruptions and sustain critical operations at ports, including disruptions caused by natural or climate-related hazards” as well as resilience to human-made disruptions. |

|

DOT |

Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equityd |

Not explicitly considered in the fiscal year 2019 NOFO. |

The fiscal year 2025 NOFO issued on November 1, 2024, states that DOT seeks to fund projects that “incorporate evidence-based climate resilience measures and features,” among other climate-related impacts and other goals. “Environmental sustainability” is one of eight statutory merit criteria. Projects that improve resilience of infrastructure to extreme weather events and natural disasters can receive a higher rating for this criterion if the application provides clear, data-driven benefits to improve the resilience of at-risk infrastructure. |

|

DOT |

Infrastructure for Rebuilding America |

Not explicitly considered in the fiscal year 2019 NOFO. |

In the fiscal year 2025-2026 NOFO issued on March 25, 2024, for the Multimodal Project Discretionary Grant Program, which included this program, “Climate change, Resilience, and the Environment” was one of six outcome criteria. A project can score highly on this criterion if, for example, the project is specifically identified in a Resilience Improvement Plan or similar plan and advances objectives in the National Climate Resilience Framework or improves disaster preparedness in an area most vulnerable to climate change impacts, such as a FEMA-designated Community Disaster Resilience Zone, among others. A high rating was assigned if either of these descriptions were met, among others. |

|

DHS |

Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities |

The fiscal year 2020 NOFOe— the program’s first year—includes criteria related to resilience and how the project will anticipate future conditions, including climate change and sea level rise. |

The fiscal year 2023 NOFO includes criteria related to and on how the project uses available climate data sets and tools to identify current and future climate risks over the project’s expected service life. |

|

DHS |

Flood Mitigation Assistance |

In the fiscal year 2019 NOFO, none of the seven scoring criteria explicitly focus on resilience, but the program’s focus is on long-term mitigation. Points are awarded to projects improving flood risk for properties with National Flood Insurance Program policies, as well as properties defined as “repetitive loss structure” or “severe repetitive loss structure.” f |

In the fiscal year 2023 NOFO, “Considerations for Climate Change and Other Future Considerations” is one of nine scoring criteria. Points are awarded for this criterion if the application describes how the project will enhance climate adaptation and resilience, as well as addressing how the project is responsive to effects of climate change such as increased risks of flash floods and wildfire. |

Source: GAO analysis of Departments of Transportation (DOT) and Homeland Security (DHS) information. | GAO‑25‑107159

Note: Description of award processes are based on the information presented in each program’s respective NOFO. We did not evaluate other documents or guidance that may provide additional nuance related to the scoring and selection processes.

aWhile related considerations may exist in the NOFOs, this table examines specific mentions of natural disaster resilience in the NOFOs. For example, the 2019 Port Infrastructure Development NOFO mentions resiliency generally, with one of its five potential project outcomes stating, “Improve state of good repair and resiliency by addressing current or projected vulnerabilities in the condition of port transportation facilities,” but did not specifically discuss natural disasters.

bThe most recent funding round for each program varied.

cPub. L. 117-81 3513(a)(1), 135 Stat. 1541, 2239-40 (2021) (codified 46 U.S.C. 54301(a)(6)(B)(iii)).

dFor the purpose of our report, we used the name of the program during the time of our review. The program has been named the Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development program before and after our review.

eAs a result of changes to the Stafford Act enacted via the Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018, FEMA discontinued its previous Pre-Disaster Mitigation grant program and established the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program. See Pub. L. 115-254, tit. VII, div. D, 1234, 132 Stat 3438, 3461 (Oct. 2018); FEMA Policy FP:104-008-05. As a result, the first available NOFO for the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program is fiscal year 2020, which we used for this analysis.

fRepetitive loss structure and severe repetitive loss structure are statutorily defined terms that refer to properties with National Flood Insurance Program policies that have experienced certain kinds of flood-related damage within a certain period. See 42 U.S.C. 4121(a)(7); 4104c(h)(3).

All but one of the grant programs we reviewed are open to infrastructure projects not related to ports; only the Port Infrastructure Development Program is specific to ports. Representatives from an inland port authority we interviewed said it was difficult for ports to compete against large infrastructure projects that may receive more community support, such as large highway projects. Representatives from inland ports stated it was difficult to compete against larger ports, because they do not have the same resources as larger ports to complete requirements for grant programs. They noted that larger ports may have staff dedicated to grant applications or resources for required analyses, such as a cost-benefit analysis.

Moreover, most of the grant programs are competitive, and many of them are oversubscribed, meaning they have more applicants than available funds. For example, according to DOT, the Port Infrastructure Development Program received 158 eligible applications requesting over $2.98 billion in fiscal year 2024, while DOT issued 31 awards for nearly $580 million.

Of the seven ports we selected, five had been awarded a grant from one of these programs; two inland ports had applied but not been selected. Several port representatives said projects would have been delayed or cancelled if they had not received federal funding. One port authority we interviewed said it had also applied for and received financial assistance through the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act for a resilience project. This is a DOT program that provides credit assistance to surface transportation projects, including intermodal freight and port access.[18]

The Extent to Which DOT and DHS Grant Funding Improved Port Resilience Is Not Fully Known

We found that the extent to which DOT and DHS fund projects at ports to improve natural disaster resilience is not fully known. For the identified grants, DOT and DHS do not keep data on the amount of awards that would specifically improve port resilience against natural disasters. Absent such data, we could not determine the amount or percentage of awarded projects that improved port resilience against natural disasters. The statutes we reviewed did not require the agencies to track this information, and as previously noted, the primary purpose of these grant programs is not necessarily to improve natural disaster resilience at ports.

Agency officials and port representatives provided the following examples showing why it is difficult for DOT and DHS to quantify the amount of funding awarded for the purpose of improving natural disaster resilience at ports.

· DOT and DHS officials stated that port improvement projects often result in increased resilience, even if the awarded project has a different primary goal. Port representatives we interviewed agreed. For example, one of the ports we visited were awarded $226.2 million to build a new port terminal and increase the port’s capacity to handle more cargo. However, port representatives explained that the construction efforts included a higher wharf height, which made the port more resilient against flooding, and a proposal to elevate the roadway that would connect the new terminal to the interstate system. The new roadway creates more evacuation routes for port workers and local residents to use in the event of an emergency such as a hurricane.

· Similarly, while a grant request might primarily be for increasing resilience against human-caused incidents or cybersecurity issues, in attaining those goals, the port’s resilience against natural disasters may also be improved. For example, one of our selected ports received an $11 million grant to, among other things, relocate a security checkpoint gate and install a new gate operating system. Port representatives said they were moving the gate from a historical flood zone, thus increasing the resilience of security operations against future flooding.

Although DOT and DHS could not quantify the amount of funding used for disaster resilience at ports, they provided examples of awarded projects that improved ports’ disaster resilience, some of which are shown in tables 3 and 4.

Table 3: Examples of Projects Identified in 2024 by the Department of Transportation That Increase Port Resilience Against Natural Disasters

|

Federal grant |

Example of awarded port resilience project |

|

Infrastructure for Rebuilding America |

In 2023, the Georgia Ports Authority was awarded $15 million to replace a port berth and two vessel berths at the Port of Brunswick’s East River Terminal. The decks of the vessel berths will be built 13 feet above mean low water and will withstand projected increases in sea level. |

|

Port Infrastructure Development Program |

In 2022, the Hawaii Department of Transportation in Honolulu was awarded $47.3 million for a project that will, among other things, strengthen port resilience against natural disasters by ensuring full port operations for up to 2 days in the event of a power blackout. |

|

Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Developmenta |

In 2020, the Port of Baltimore was awarded $10 million for critical flood mitigation improvements at one of the port’s terminals. This project is part of a larger, long-term resilience and flood mitigation improvement effort impacting freight movement at the port. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Transportation information and information provided by agency officials. | GAO‑25‑107159

aDuring the time of our review, this program was known as the Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity program.

Table 4: Examples of Projects Identified in 2024 by the Department of Homeland Security That Increase Port Resilience Against Natural Disasters

|

Federal grant |

Example of awarded port resilience project |

|

Hazard Mitigation Grant Program |

The Jose D. Leon Guerrero Commercial Port in Guam was awarded over $600,000 for fiscal year 2019 to fund improvements to certain systems at the port. The project would allow for resilience improvement against earthquakes, typhoons, and storm surge events. |

|

Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities |

Skagway, Alaska, was awarded $19.9 million for fiscal year 2022 to fund rockslide mitigation work on the mountainside east of the Port of Skagway. The project is designed to stabilize the slide zone to allow for the re-opening of the railroad dock. |

|

Pre-Disaster Mitigation |

In 2022, the Port of Portland in Oregon was awarded $3.75 million to help fund a seismically resilient runway at Portland International Airport. The runway is designed to withstand a severe earthquake, allowing the runway to support large-scale medical evacuations and movement of people and cargo immediately following one. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Homeland Security grant documentation. | GAO‑25‑107159

We also found that the extent to which DOT and DHS’s grant programs have addressed identified needs related to port resilience is not fully known, because the agencies do not have an inventory of identified needs or an overall risk assessment of ports’ vulnerabilities to natural disasters. While five of our selected ports conducted risk assessments to identify vulnerabilities, two ports we spoke with had not. Additionally, of the 31 Port Infrastructure Development Program grants awarded in fiscal year 2024, only four recipients included a risk assessment in their application package. We discuss the efforts of federal agencies and ports related to risk assessment in the next section of this report.

Federal Agencies Make Resources Available to Ports to Help Identify Vulnerabilities to Natural Disasters and Improve Resilience

Federal Agencies Developed Frameworks and Voluntary Guidance for Ports to Identify Vulnerabilities

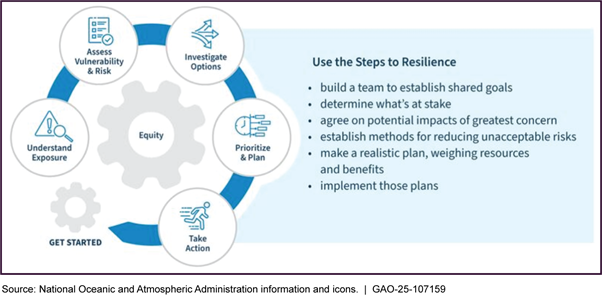

Federal agencies have developed several frameworks related to climate and resilience that ports and stakeholders could use to identify vulnerabilities that threaten port resilience. For example, the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit, a website created by a number of federal agencies and organizations led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), provides information, tools, and best practices for improving local resilience. One framework included in the toolkit describes five “steps to resilience” that communities can use to identify hazards and develop a resilience plan. One of these steps describes the process to assess vulnerabilities. Although these frameworks are not specific to ports, they may be used for ports and their surrounding communities. See appendix II for more information on disaster resilience frameworks that the federal government has developed.

Additionally, federal agencies have developed risk assessment guidance that port authorities and port stakeholders can use to identify vulnerabilities to natural disasters, including the vulnerabilities of ports’ landside connectors. These guides provide ports and maritime stakeholders with various options for addressing resilience, including consulting with stakeholders, identifying hazards and threats, and evaluating port infrastructure. The U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System (CMTS) compiled a list of available guidance relevant to resilience in its “Resilience Tool Matrix” published on its website.[19] Two examples of guidance include CISA’s Marine Transportation System Resilience Assessment Guide and NOAA’s Ports Resilience Index: A Port Management Self-Assessment.

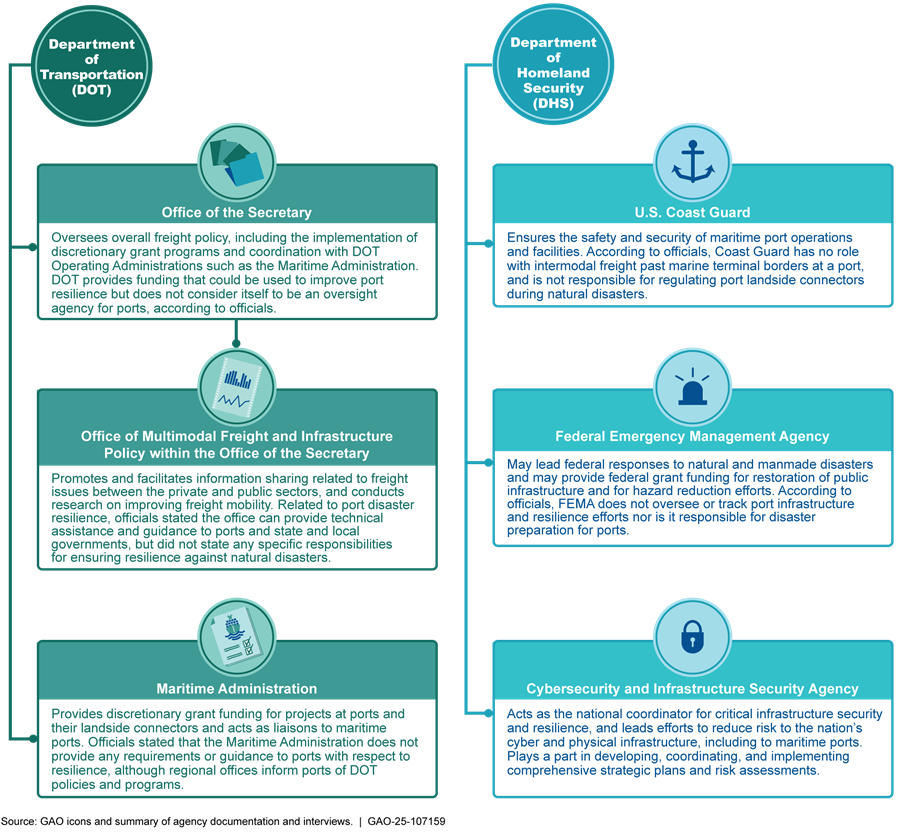

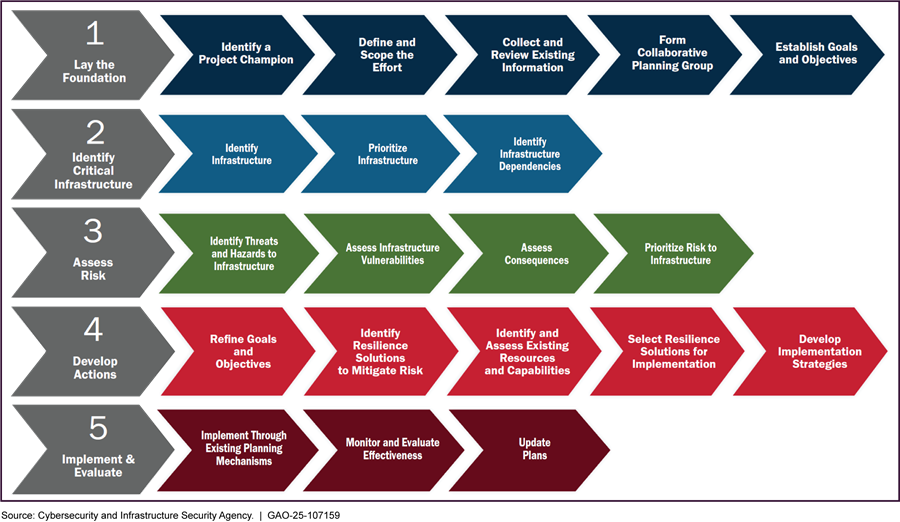

· Marine Transportation System Resilience Assessment Guide. CISA published this guide in spring 2023 and intended it to be used by federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial governments, port authorities, and private sector owners and operators. The document guides users through the process of designing and executing a risk assessment specific to the marine transportation system and includes considerations for consulting stakeholders and identifying critical infrastructure. Figure 3 shows an illustration of the risk assessment process that CISA included in the guide.

Figure 3: Generalized Risk Assessment Process Detailed in the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s (CISA) Marine Transportation System Resilience Assessment Guide

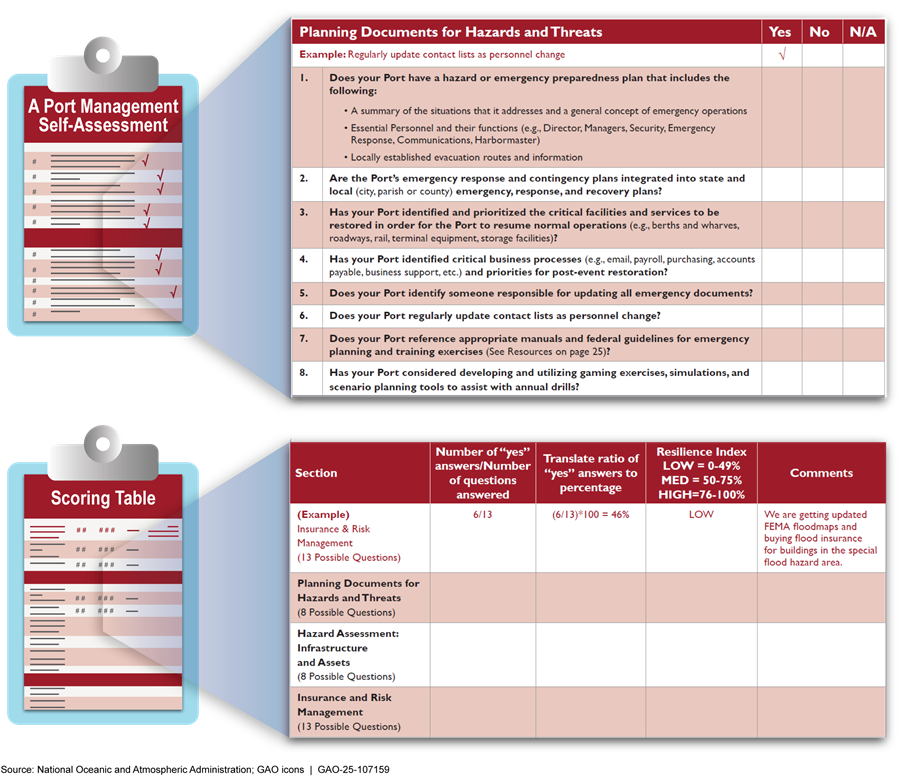

· Ports Resilience Index: A Port Management Self-Assessment. Published by NOAA in coordination with the Gulf of Mexico Alliance in 2016, the index is intended for use by port authorities and port management organizations. The index is a self-assessment tool that allows ports to assess preparedness for maintaining operations during and after a disaster, and to identify actions that stakeholders should pursue to address vulnerabilities and maintain long-term viability. See figure 4 for excerpts of sections included in the index. The index suggests that ports consider large-scale disasters (e.g., natural hazards affecting a widespread area, such as hurricanes) and small-scale disasters (e.g., short-term weather events, or events affecting only the port facility, such as on-site fires or floods) when completing the self-assessment.

Once the port authority or management organization has completed the self-assessment of the port’s processes and vulnerabilities, the index provides them with a total score, or “Resilience Index,” which is an indicator of the port organization’s ability to reach and maintain an acceptable level of functioning and structure after a disaster.

· A LOW Resilience Index indicates that the port should pay specific attention to that category and make efforts to address the areas of low rating.

· A MEDIUM Resilience Index indicates that the port could do more work to improve resilience in that category.

· A HIGH Resilience Index indicates that the port is well prepared for a storm event.

Figure 4: Excerpts of the Planning Documents for Hazards and Threats Section and the Scoring Section of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Ports Resilience Index

Additionally, federal agencies provide guidance to stakeholders that is not specific to particular ports or to natural disasters, but that provides information on assessing risks and threats that may affect ports and their surrounding areas. For example:

· Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment and Stakeholder Preparedness Review Guide. This guide, which FEMA published in May 2018, outlines a three-step risk assessment process to help communities (1) identify the threats and hazards likely to affect them; (2) estimate the impacts of those threats and hazards if they occurred; and (3) identify areas for improvement where the community lacks the resources or skills necessary to mitigate, respond to, and recover from a threat or hazard. These may include potential impacts to ports and other facilities. Threats that the guide assesses include earthquakes, tornados, winter storms, and hurricanes, as well as technological hazards (i.e., dam failure, pipeline explosion) and human-caused incidents. The guide recommends the active community involvement of stakeholders such as emergency management agencies (including fire, police, and medical services), federal agencies, infrastructure owners and operators, port or transit organizations, and supply chain stakeholders.[20]

· For each of its 41 Captain of the Port Zones, the Coast Guard works with port and local authorities to develop a Marine Transportation System Recovery Plan, and through Area Maritime Security Committees to develop an Area Maritime Security Assessment, which is then used to develop an Area Maritime Security Plan.[21] These documents include information that applies to the ports located within the particular zone.

· Guidelines for Drafting the Marine Transportation System Recovery Plan. These guidelines provide a template for Coast Guard officials, with the assistance of port stakeholders, to address all hazards, including natural disasters, and to create recovery processes and procedures for ports within each zone. The guide is intended for use by marine transportation recovery personnel and maritime community stakeholders within these sectors.[22]

· Guidelines for the Area Maritime Security Committees and Area Maritime Security Plans Required for U.S. Ports. These guidelines provide instructions for identifying critical infrastructure, including landside connectors, at ports within each of the zones. For example, the Area Maritime Security Assessment and Plan for the New Orleans Area covers at least nine ports and lists critical infrastructure including bridges, railways, and refineries. These assessments focus primarily on responding to security and human-caused incidents (i.e., terrorism), but can include responses to natural disasters. For example, the Area Maritime Security Plan for the New Orleans Area includes information concerning floods. The Area Maritime Security Plans also focus primarily on efforts pertaining to port waterways, and less on efforts pertaining to landside connectors. The guidelines are intended for use by Coast Guard officials, including Captains of the Port, members of Area Maritime Security Committees, and maritime community stakeholders.[23]

According to agency officials, there are no Coast Guard, CISA, FEMA, or MARAD regulatory requirements for individual ports to conduct an all-hazards assessment for their infrastructure. Of the seven port authorities we spoke with, five had assessed and documented risks of their individual port’s vulnerabilities to natural disasters for various reasons. For example, representatives from a coastal port that is affected by hurricanes noted that they conduct a risk assessment to identify vulnerabilities and determine operational resilience for insurance purposes. Representatives from another coastal port said that their plan lists operating procedures based on the severity of an earthquake, since that is their biggest natural hazard.

Port authorities are primarily responsible for working with stakeholders to identify vulnerabilities of their port to natural disasters and choosing which federal tools or guides to use in this process. Representatives from these five ports told us they have not used federal guidance extensively to assess risks of natural disasters, for a variety of reasons. For example, when asked about the CISA Marine Transportation System Resilience Assessment Guide, representatives from one port said they had not yet received training on how to use it effectively, but they would appreciate receiving such training in the future. In addition, they said the guidance might focus on areas that are of concern to CISA but not priority areas for their port. Representatives from a second port told us they had a historical process and documentation, so did not believe it was necessary to consult federal guidance.

CISA officials told us the agency is not authorized to track who downloads or uses the Marine Transportation System Resilience Assessment Guide. They noted that they do track the number of views they receive on the guide’s webpage and provide a tool that directs users to the relevant guidance for their specific needs. Furthermore, at the time of our review, CISA officials told us they were planning to develop anonymous feedback surveys to collect data about the guide’s perceived value, applicability, and accessibility.

Going forward, National Security Memorandum 22 (NSM-22) has requirements for federal agencies related to understanding risks to critical infrastructure. NSM-22, published in April 2024, updates and continues earlier presidential guidance and is intended to strengthen and maintain secure, functioning, and resilient critical infrastructure. It encompasses a comprehensive effort to protect this infrastructure against all threats and hazards, and requires

· the Director of National Intelligence to coordinate with DHS and state, local, tribal, and territorial governments, as well as the private sector, to understand relevant threats to critical infrastructure and integrate sector risk perspectives into analysis; and

· DOT and DHS to conduct biennial risk assessments of the most significant critical infrastructure risks.[24]

At the time of our review, DOT and DHS were conducting their first biennial risk assessment in accordance with NSM-22. CISA and Coast Guard officials said the risk assessment required by NSM-22 will not require a granular understanding of infrastructure risk at the individual port level and will not be negatively impacted if ports do not have individual risk assessments. DOT officials stated that the risk assessment required by NSM-22 will focus on the highest priorities of each mode of transportation, including for the marine transportation system. They noted that the data considered for risk evaluation are primarily derived from the Transportation Security Administration’s Transportation Sector Security Risk Assessment and Cybersecurity Risk Assessment, the Coast Guard Maritime Security Risk Analysis Model and Area Maritime Security Plans, and the DOT Enterprise Risk Report.

Federal Agencies Have Multiple Coordination Mechanisms and Offer Some Training That Might Improve Resilience

Federal agencies have established multiple coordination mechanisms that might improve natural disaster resilience at ports. Federal officials told us the outcomes of these coordination efforts depend, to some extent, on the staffing and interests of stakeholders at the time. Examples of coordination mechanisms include:

· CMTS. Federal law specifically designates this committee and it serves as a federal interagency policy coordinating body for the marine transportation system. At the time of our review, CMTS had 16 voting and eight nonvoting members.[25] The sub-Cabinet Coordinating Board, which handles much of the day-to-day policy coordination and work plan establishment, meets at least quarterly to identify and address needs in the maritime issue area. The members of the Coordinating Board include agency heads and key office directors. The chair of the Coordinating Board rotates annually between the Secretaries of Transportation, Defense, Commerce, and Homeland Security. The Coast Guard, CISA, and MARAD have representatives on the CMTS Coordinating Board; FEMA officials told us they do not have a standing role in CMTS. CMTS also hosts several task teams and a working group to examine topic areas such as supply chain infrastructure and resilience. In all, representatives from about 30 federal entities interact on maritime issues, including resilience, according to CMTS representatives. For example, representatives told us they identified the need for resilience assessment guides through work on their resilience task team. They said CMTS also assisted in the effort that resulted in CISA working with the Army Corps of Engineers to develop the Marine Transportation System Resilience Assessment Guide. CISA officials told us that CMTS provides an appropriate forum to discuss best practices and receive feedback on products such as the resilience guide. CMTS representatives told us the committee relies on agency subject matter experts to actively provide concerns and participate in discussions on behalf of their respective agencies.

· Harbor Safety Committees. These committees comprise local maritime stakeholders and federal government representatives, including the Coast Guard and MARAD’s Gateway Offices.[26] There is no requirement for ports to create these committees and stakeholder participation is voluntary, although the Coast Guard encourages their use. These committees provide port operations stakeholders—which may include terminal operators, port authority staff, shippers, and others—with a local forum as they work to improve the safety, security, mobility, and environmental protection of the port or waterway. According to the Coast Guard, there are 50 Harbor Safety Committees within the 41 Captain of the Port Zones across the country. Representatives from one port we spoke with said they send representatives to participate, but the purpose of the committee at their port is primarily for pollution prevention and safe vessel operation, not natural disaster resilience.

· Area Maritime Security Committees. These 43 Coast Guard committees represent each of the 41 Captain of the Port Zones, which can cover multiple ports per committee. Each committee must have at least seven members with an interest in the security of the area, including individuals from certain state, local, federal, tribal, or territorial governments and subdivisions; law enforcement and security organizations; the maritime industry; and other port stakeholders with special competence in maritime security or who are affected by port security practices and policies.[27] MARAD’s Gateway Directors also work with the Area Maritime Security Committees within their region, while FEMA and CISA officials said they do not regularly attend committee meetings. The committees assist the Captain of the Port in developing an Area Maritime Security Plan and serve as a link for disseminating security information to port stakeholders, among other responsibilities. Representatives from six of the seven ports we interviewed said they regularly attend these committee meetings, and representatives from two ports said CISA’s Marine Transportation System Resilience Assessment Guide was brought up during a meeting. However, a Coast Guard official told us that some port stakeholders do not actively engage in committee meetings or trainings.

Port representatives we interviewed told us they coordinate with federal agencies in various ways. For example, representatives from a coastal port told us that when they are responding to a disaster, they follow the Coast Guard’s Recovery Plan for their area. This plan follows FEMA’s National Incident Management System, which includes communication and notification protocols and procedures for times when communications are compromised.[28] In addition, representatives from several other ports told us that they generally coordinate with emergency management offices within their local and state governments, such as to handle emergency situations involving the landside connectors, rather than the relevant federal agencies. For example, representatives at one port we spoke with explained that they worked with their city emergency management office to develop a hazard mitigation plan for the port that included the landside connectors.

As part of their coordination efforts, federal agencies provide port stakeholders with some training and exercise opportunities related to natural disaster resilience, but such opportunities rely on the interest of parties involved. For example, Captains of the Port are generally required to coordinate with Area Maritime Security Committees to conduct annual tabletop or field exercises to simulate a disaster and test the effectiveness of the Area Maritime Security Plan. Coast Guard officials said that during the planning stage, they have the flexibility to include a natural disaster in the exercise in addition to the required human-caused disasters, such as terrorist attacks, although not all stakeholders actively participate in the exercises. CISA offers to assist with exercises, according to CISA officials. None of the representatives from our seven selected ports recalled DOT or DHS providing an exercise that focused exclusively on responses to natural disasters. Port representatives said most exercises pertained to infrastructure security and cybersecurity responses.

Going forward, NSM-22 requires DOT and DHS, in conjunction with the Director of National Intelligence, to coordinate information-sharing with critical infrastructure owners and operators and improve centralized reporting.[29] It is unknown how this requirement would affect coordination with port owners and operators.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOT and DHS for review and comment. DOT and DHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretaries of Transportation and Homeland Security, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-2834 or vonaha@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Andrew Von Ah

Director, Physical Infrastructure Issues

Appendix I: Federal Funding Available to Potentially Improve Port Resilience Against Natural Disasters

This appendix provides information on federal funding that port authorities, as well as state, local, territorial, or tribal stakeholders, could apply for to improve port resilience against natural disasters as of December 2024. This information is contained in the sixth edition of the Federal Funding Handbook for the Marine Transportation System (handbook), released by the U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System (CMTS) in 2024.[30] According to CMTS members, the handbook is developed by staff as they review grant documentation or information provided by funding agencies. CMTS staff developed categories for “purpose” and “keywords” in the third edition of the handbook to make it easier for users to search for grant opportunities.

Based on our review of federal funding assistance included in the handbook, 94 federal funding opportunities are available to entities within the marine transportation system, including ports. Within that population, CMTS included the word “resilience” in the purpose or keyword of 22 funding opportunities (see table 5). Of those 22 funding opportunities, 10 specifically mention natural disasters in the purpose or keyword categorization of the funding opportunity. To determine if natural disasters were mentioned, we searched for various terms, including but not limited to, “natural hazard,” “natural disaster,” “extreme weather,” “severe weather,” and natural disaster events such as tornado, hurricane, wildfire, and earthquake. Of those 10 funding opportunities, one was listed specifically for ports: the Port Infrastructure Development Program, administered by the Department of Transportation (DOT).

Table 5: Federal Funding for the Marine Transportation System Related to Resilience, According to Keyword and Purpose Funding Labels Used by the U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System (CMTS)

|

Parent agency |

Funding program |

Type of funding |

Do CMTS keywords or purpose categories specifically include natural disasters? |

Do CMTS keywords or purpose categories specifically include ports? |

|

Army Corps of Engineers |

Continuing Authorities Program |

Project development, cost share |

Yes |

No |

|

Department of Commerce |

Coastal Resilience Grants Program |

Grant |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Planning and Local Technical Assistance Program |

Discretionary grant |

No |

No |

|

Department of Homeland Security |

Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities |

Discretionary grant |

Yes |

No |

|

Flood Mitigation Assistance Grant Program |

Discretionary grant |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Hazard Mitigation Grant Program |

Grant, cost share |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Port Security Grant Program |

Grant, cost-match |

No |

Yes |

|

|

Pre-Disaster Mitigation Grant Program |

Grant, cost-match |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Transit Security Grant Program |

Competitive grant |

No |

No |

|

|

Department of the Army |

Corps Water Infrastructure Financing Program |

Loan |

Yes |

No |

|

Department of the Interior |

Clean Vessel Act |

Discretionary grant |

No |

No |

|

Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund / Section 6 Grants |

Grant, cost-match |

No |

Yes |

|

|

Endangered Species Conservation - Recovery Implementation Funds |

Discretionary grant, cooperative agreement |

No |

No |

|

|

Department of Labor |

Critical Sector Job Quality Grants |

Discretionary grant |

No |

No |

|

Department of Transportation |

Marine Highway Program |

Competitive grant |

No |

Yes |

|

Metropolitan Planning Program |

Formula grant |

No |

No |

|

|

Port Infrastructure Development Program |

Competitive grant |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

Diesel Emissions Reduction Act Tribal and Insular Area Grants |

Competitive grant |

No |

No |

|

National Science Foundation |

Civil Infrastructure Systems |

Grant |

No |

No |

|

Cyber Physical Systems |

Discretionary grant |

No |

No |

|

|

Humans, Disasters, and the Built Environment |

Grant |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Small Business Administration |

Disaster Loan Assistance |

Loan |

Yes |

No |

Source: GAO analysis of CMTS information. | GAO‑25‑107159

Note: Information presented is based on program information and funding assistance type provided in CMTS’s federal funding handbook. We did not independently verify program information. U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System, Federal Funding Handbook for the Marine Transportation System, Sixth Edition (Washington, D.C.: March 2024).

This table does not include the Infrastructure for Rebuilding America or Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity grant programs. In 2024, DOT officials identified those two programs as being available to ports to improve the resilience of port infrastructure, specifically their landside connectors, against natural disasters. DOT officials did not specifically identify the Marine Highway Program or Metropolitan Planning Program when asked about funding programs relevant to improving resilience of ports and their landside connectors against natural disasters.

The Department of Transportation (DOT) and others within the federal government have developed several frameworks to guide users through assessing risks and developing mitigation strategies to improve resilience of critical infrastructure to natural disasters and climate change. While these are not specific to ports, these frameworks examine community infrastructure and critical infrastructure, which can include ports and their landside connectors.

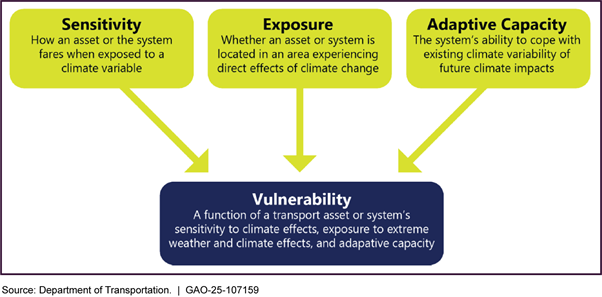

· Building Resilient Infrastructure Toolkit. Published by DOT in November 2022, the toolkit serves as a guide for creating strong and adaptable transportation systems. The toolkit provides governments with information about how they can assess the vulnerability of their transportation infrastructure to the effects of climate change and identify adaptation strategies to make those systems more resilient. See figure 5 for a description of what vulnerability means in relation to the transportation system. It also describes the impacts of climate change on transportation infrastructure, which could impact roads and rail lines via flooding, bridges and port infrastructure via storm surges, and sea level rise.

The toolkit walks users through climate change-related risk and vulnerability assessments using the following general steps: (1) articulate objectives and define study scope, focusing on climate change impacts that may have the greatest effects and identifying critical transportation assets; (2) compile asset data (on roadways, tunnels, ports, floodplains, and so on); (3) obtain climate data for the study area; and (4) assess vulnerability.[31]

Figure 5: Description of the Components of Vulnerability from the Department of Transportation’s Building Resilient Infrastructure Toolkit

· Implementing the Steps to Resilience: A Practitioner’s Guide. The Steps to Resilience were developed by a partnership of federal agencies in coordination with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Program Office in 2014 for the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit. The Practitioner’s Guide, published in 2022, provides instructions for implementing the Steps, which includes a framework for assessing risks to increase local infrastructure resilience. Potential users include practitioners and community stakeholders. The guide describes how and when to use climate-related information to inform decisions related to resilience. See figure 6 for the steps in this framework.[32]

Figure 6: Steps to Resilience as Shown in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit

· Infrastructure Resilience Planning Framework. Published by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency in February 2024, the framework provides a guide for incorporating security and resilience considerations into critical infrastructure planning. The framework aims to help communities with (1) understanding and communicating how infrastructure resilience contributes to community resilience; (2) identifying how threats and hazards might impact community infrastructure; (3) preparing governments, owners, and operators to withstand and adapt to evolving threats and hazards; (4) integrating infrastructure security and resilience considerations, including impacts of dependencies and cascading disruptions, into planning and investment decisions; and (5) recovering quickly from disruptions. See figure 7 for an outline of the steps included in the framework.[33]

Figure 7: Steps in the Infrastructure Resilience Planning Framework as Depicted by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency

· National Climate Resilience Framework. Published by the White House in September 2023, this framework acts as a foundation for near- and longer-term climate resilience efforts across the federal government. The framework is intended to be used in coordination with nonfederal partners, including through follow-on implementation of plans and actions. The framework also identifies objectives to strengthening protections against climate change.[34]

GAO Contact

Andrew Von Ah, (202) 512-2834 or vonaha@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Sally Moino (Assistant Director), Abby Volk (Analyst in Charge), Andrew Curry, Emily Crofford, Melanie Diemel, Geoffrey Hamilton, Heather MacLeod, Hugh Paquette, Drew Parent, Amber Sinclair, Justin Snover, Joe Thompson, Michelle Weathers, Lauren Wice, and Alicia Wilson made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 2024 Port Performance Freight Statistics Program: Annual Report to Congress (Washington, D.C.: 2024). At the time of our review, these were the most recent data available.

[2]In this report, we refer to resilience as the ability to prepare for threats and hazards, adapt to changing conditions, and withstand and recover rapidly from adverse conditions and disruptions.

[3]GAO, High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO‑23‑106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023).

[4]Pub. L. No. 117-263, tit. XXXV, § 3256, 136 Stat. 2395, 3081 (2022).

[5]DOT and DHS were designated co-sector specific agencies for transportation in Presidential Policy Directive 21: Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience. The White House, Presidential Policy Directive on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience, (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 12, 2013). This directive was replaced in 2024 by National Security Memorandum 22 (NSM-22). The White House, National Security Memorandum on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience, NSM-22. NSM-22 designates DOT and DHS as “Co-Sector Risk Management Agencies” for transportation systems.

[6]National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Strengthening Post-Hurricane Supply Chain Resilience: Observations from Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2020); National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Making U.S. Ports Resilient as Part of Extended Intermodal Supply Chains (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2014).

[7]We visited the ports located in New Orleans, LA, and Greenville, MS. We held videoconferences with ports located in Long Beach, CA; Los Angeles, CA; Wilmington, DE; Duluth, MN; and Pittsburgh, PA. Three of these ports are inland, and four are coastal. We interviewed industry representatives from the (1) American Association of Port Authorities and (2) Inland Rivers, Ports, and Terminals, Inc.

[8]The agencies identified two additional programs that were outside our scope. Specifically, DOT officials said the Promoting Resilient Operations for Transformative, Efficient, and Cost-saving Transportation Program, known as PROTECT, provided funds that could improve port resilience against natural disasters. However, at the time of our analysis, DOT had not yet awarded grants from that program, so we did not include it in our review. DHS officials stated that the Public Assistance grant program could provide funds for improving port resilience as part of work to restore disaster-damaged public infrastructure. However, they noted that the program is only available following a presidential disaster declaration, unlike the other programs DHS identified, which focus more on proactive investments for community resilience. Therefore, we considered the Public Assistance grant program outside our scope.

[9]U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System, Federal Funding Handbook for the Marine Transportation System, Sixth Edition (Washington, D.C.: March 2024).

[10]White House, National Climate Resilience Framework (Washington, D.C.: September 2023).

[11]U.S. Federal Government, “Steps to Resilience Overview,” U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit, accessed September 25, 2024, https://toolkit.climate.gov/overview-steps.

[12]Department of Homeland Security, 2013 National Infrastructure Protection Plan, Partnering for Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience (Washington, D.C.: December 2013).

[13]Department of Homeland Security, National Disaster Recovery Framework, Second Edition (Washington, D.C.: June 2016).

[14]Department of Homeland Security, National Mitigation Framework, Second Edition (Washington, D.C.: June 2016).

[15]The White House, National Security Memorandum on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience, NSM-22.

[16]GAO, Climate Information: A National System Could Help Federal, State, Local, and Private Sector Decision Makers Use Climate Information, GAO‑16‑37 (Washington, D.C.: November 23, 2015).

[17]National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Strengthening Post-Hurricane Supply Chain Resilience: Observations from Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2020).

[18]Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act projects located within a port terminal must be limited to only such surface transportation infrastructure modifications as are necessary to facilitate direct intermodal interchange, transfer, and access into and out of the port. 23 U.S.C. § 601(a)(12)(D)(iii).

[19]“Tool Matrix,” Resilience Resources, U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System, accessed April 4, 2024, https://www.cmts.gov/Topics-Projects/Resilience/.

[20]Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Comprehensive Preparedness Guide 201: Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA) and Stakeholder Preparedness Review (SPR) Guide, 3rd Edition (Washington, D.C.: May 2018).

[21]Captain of the Port Zones are designated by Coast Guard. Captain of the Port means the officer of the Coast Guard, under the command of a District Commander, who is designated by the Commandant for the purpose of giving immediate direction to Coast Guard law enforcement activities within the general proximity of the port in which they are situated. 33 C.F.R. § 125.05. The boundaries of each zone are outlined in federal regulation. See 33 C.F.R. § 3.01-1 et seq.

[22]Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Coast Guard, Guidelines for Drafting the Marine Transportation System Recovery Plan, Navigation and Vessel Inspection Circular No. 04-18 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 21, 2018).

[23]Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Coast Guard, Guidelines for the Area Maritime Security Committees and Area Maritime Security Plans Required for U.S. Ports, Navigation and Vessel Inspection Circular No. 09-02, Change 6 (Washington, D.C.: July 20, 2023).

[24]The White House, National Security Memorandum on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience, NSM-22.

[25]CMTS includes 14 committee members enumerated in statute, as well as “the head of any other Federal agency who a majority of the voting members of the Committee determines can further the purpose and activities of the Committee,” and “as many nonvoting members as a majority of the voting members of the Committee determines is appropriate to further the purpose and activities of the Committee.” 46 U.S.C. § 50401(c).

[26]MARAD provides critical marine transportation outreach activities at major U.S. gateway ports, which include 10 of the largest ports on the West, East, and Gulf Coasts, the Great Lakes, and the inland river system. Offices located in these areas work with state and local authorities and a broad range of port, shipper, and carrier stakeholders, among others, to cooperate on projects, identify federal and state funding, and work on environmental and community challenges in the ports and their intermodal connections.

[27]33 C.F.R. § 103.305(a).

[28]The National Incident Management System guides all levels of government, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector to work together to prevent, protect against, mitigate, respond to, and recover from incidents.

[29]The White House, National Security Memorandum on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience, NSM-22.

[30]U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System, Federal Funding Handbook for the Marine Transportation System, Sixth Edition (Washington, D.C.: March 2024).

[31]Department of Transportation, Office of the Secretary, Building Resilient Infrastructure, Edition 1 (Washington, D.C.: November 2022).

[32]U.S. Federal Government, “Steps to Resilience Overview,” U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit, accessed September 25, 2024, https://toolkit.climate.gov/overview-steps.

[33]Department of Homeland Security, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, Infrastructure Resilience Planning Framework, Version 1.2 (Washington, D.C.: February 2024).

[34]White House, National Climate Resilience Framework (Washington, D.C.: September 2023).