2020 CENSUS

Coverage Errors and Challenges Inform 2030 Plans

Report to Congressional Requesters

November 2024

GAO-25-107160

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107160. For more information, contact Yvonne D. Jones at 202-512-6806 or jonesy@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107160, a report to congressional requesters

November 2024

2020 Census

Coverage Errors and Challenges Inform 2030 Plans

Why GAO Did This Study

The Bureau assesses the accuracy of its census counts with an independent process—the Post-Enumeration Survey. Results from this survey showed that some states and demographic groups (i.e., populations by characteristics such as race and age) were under- or overcounted in 2020. GAO has previously reported on the long-standing problem of coverage errors for various population groups.

GAO was asked to report on the Bureau’s efforts to assess accuracy of the 2020 Census. This report describes (1) Bureau assessments of the 2020 Census population counts and how they compare to previous censuses; (2) potential causes and implications of coverage errors in the 2020 Census; and (3) steps the Bureau and census stakeholders identified to improve the accuracy of the 2030 Census.

GAO reviewed the Bureau’s Post-Enumeration Survey measures for the 2020, 2010, and 2000 censuses. GAO also reviewed Bureau and other authoritative sources’ reporting on the accuracy of the 2020 Census and its challenges and potential changes to improve the accuracy of the 2030 Census. GAO also interviewed Bureau officials.

GAO provided a draft of this report to the Department of Commerce for its review. The Bureau provided technical comments, which GAO incorporated, as appropriate.

What GAO Found

The U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020 Post-Enumeration Survey estimated that two geographic regions and 14 states had statistically significant net coverage errors in the 2020 Census. Net coverage error is the difference between the census count and the survey estimate of the actual population size. The survey results also showed that under- and overcounts persisted for various demographic groups. For example, in 2020 and 2010, Black or African American and Hispanic persons, young children, and renters were undercounted, while non-Hispanic White persons, adults over 50, and homeowners were overcounted. However, the survey estimated no statistically significant net coverage error for the national population count. The Bureau reported that this estimate was consistent with the survey’s national estimate in 2010.

Note : For more details, see figure 5 in GAO-25-107160.

The COVID-19 pandemic and other long-standing challenges potentially affected the accuracy of 2020 Census counts. GAO previously reported on these challenges, including the Bureau’s late census design changes, staffing issues, and budgetary uncertainty. GAO and others have reported that errors in census data may result in potential implications for uses, including allocating funds.

As of October 2024, the Bureau had plans for over 50 research projects and other efforts to inform the design of the 2030 Census. GAO identified examples of projects and related efforts that leverage insights from 2020 Census coverage challenges to improve accuracy in the 2030 Census across four categories: (1) public engagement, (2) use of data collected by governments while administering programs, (3) Post-Enumeration Survey design, and (4) operations. For example, the Bureau has planned projects to improve data collection to address challenges with counting people in group quarters like prisons and college dormitories.

|

Abbreviations

|

|

|

NASEM |

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine |

|

PES |

Post-Enumeration Survey |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 21, 2024

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Chairman

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Ron Johnson

Ranking Member

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

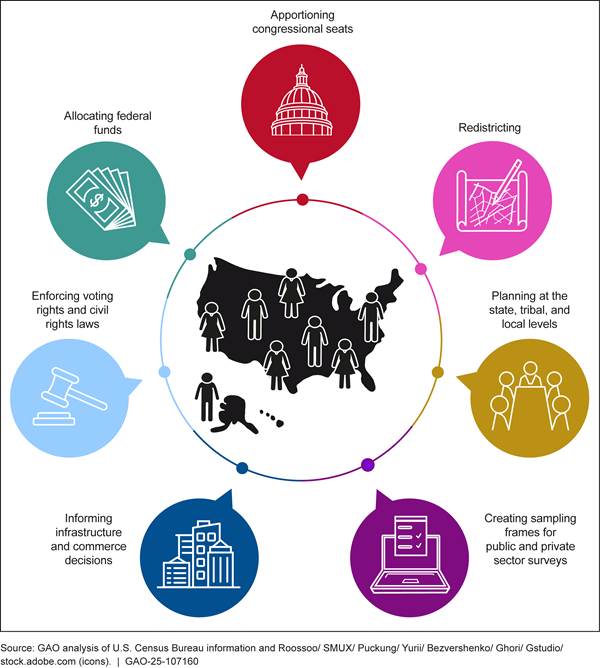

A goal of the Decennial Census is to count everyone once, only once, and in the right place.[1] An accurate count is critical for informing various uses of decennial data, including apportioning congressional seats, redistricting at different levels of government, and allocating billions in federal financial assistance every year.

The 2020 Census was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which posed unprecedented challenges and further complicated an already complex effort. We previously published a series of reports that reviewed U.S. Census Bureau decisions and challenges for 2020 operations, including effects of the Bureau’s late changes to the design of the census, issues hiring and retaining enumerators and other staff, and potential risks to the quality and accuracy of census data.[2]

The Bureau assesses the accuracy of its census counts with a Post-Enumeration Survey (PES)—an independent survey conducted for a sample of the population—to measure errors in the current census and improve future censuses. The Bureau first conducted the PES in 1950 and has done so for each decennial since the 1980 Census. Results from the 2020 PES found that certain states and demographic groups were either undercounted or overcounted in the 2020 Census—a long-standing problem on which we have previously reported.[3]

You asked us to review the Bureau’s efforts to assess the accuracy of the 2020 Census, the causes and implications of undercounts and overcounts as measured by the PES, and what the Bureau can do to improve accuracy in the 2030 Census. This report reviews (1) the accuracy of the 2020 Census population counts and how they compare to previous censuses; (2) potential causes and implications of coverage errors in the 2020 Census; and (3) steps the Bureau and other stakeholders have identified to help improve the accuracy of the 2030 Census.

To address our first objective, we reviewed the Bureau’s measures of population coverage accuracy (i.e., undercounts and overcounts) in the 2020 Census from the 2020 PES. The Bureau reported separate PES estimates for (1) the national population living in the U.S., including the 50 states and the District of Columbia but excluding remote areas of Alaska; and (2) the population living in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. The PES estimates for the U.S. and Puerto Rico excluded persons living in group quarters (e.g., prisons, college dormitories, and nursing homes).[4]

We reviewed published Bureau reports and presentations to document coverage accuracy by various population categories, including race and ethnicity, age, and sex. We reviewed similar PES measures from the 2010 and 2000 censuses and measures from the 2020 Demographic Analysis method to draw comparisons, where methodologically appropriate.[5] In addition, we assessed the Bureau’s report methodologies and interviewed Bureau officials to identify potential limitations for making comparisons across decennials. We determined the measures of population coverage accuracy were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

To address our second objective, we reviewed Bureau reports, assessments, and presentations to summarize operations and challenges for the 2020 Census and 2020 PES, and to identify steps the Bureau takes to address census coverage errors. We also identified relevant reports from authoritative sources, which included ourselves; the American Statistical Association; and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). We reviewed these reports to identify (1) key findings related to how the Bureau carried out the 2020 Census and 2020 PES, (2) implications of coverage errors in the 2020 Census, and (3) Bureau efforts to address census coverage errors. We conducted a systematic literature search to inform our related background understanding. We also interviewed officials from the Bureau to clarify their findings and conclusions in published reports and presentations.

To address our third objective, we reviewed Bureau documentation and reports from authoritative external sources to identify lessons learned, planned operations, and proposed changes to improve the accuracy of the 2030 Census and 2030 PES. We also interviewed Bureau officials to obtain status updates on relevant planned research projects and operations for the 2030 Census.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The U.S. Constitution mandates a periodic census of the population, which the Bureau conducts every 10 years.[6] The counts that result are essential to the various ways in which the Bureau, governments, the private sector, and other stakeholders use census data (see fig. 1).

The PES is an independent survey of a sample of the population that occurs

after the Bureau completes census enumeration. The Bureau conducts the PES to

estimate net coverage error in the census for people and housing units. Net

coverage error is the difference between the census population count and the

PES estimate of the actual population size.[7]

The Bureau published a series of reports on each PES for the 2000, 2010, and

2020 censuses that included estimates of net coverage error for the U.S.

national and Puerto Rico populations and for various subgroups (i.e.,

populations defined by geography or demographic characteristics that include

age, race, and sex).[8]

In these reports, the Bureau identified which net coverage errors were

statistically different from zero at the 90 percent confidence level (which we

refer to as “statistically significant”).

A statistically significant net coverage error with a negative value indicated that the PES estimated that the census omitted more people than the sum of people it imputed and erroneously counted (undercount). A statistically significant net coverage error with a positive value indicated that the PES estimated that the census omitted fewer people than the sum of people it imputed and erroneously counted (overcount).[9] For example, a subgroup with a statistically significant net coverage error of negative 1 percent would indicate that the 2020 PES estimated that the 2020 Census count was 1 percent lower for that subgroup than it should have been.

If a PES coverage error estimate was not statistically significant, the Bureau did not report an undercount or overcount in the census for that population. Our reporting of the Bureau’s estimates of net coverage error is in percentage terms of the national PES estimated population count or respective subgroups.

The populations covered by the 2020 PES samples for the U.S. and Puerto Rico differed from those covered by the 2020 Census.[10] While both the PES and census aimed to cover all people living in the U.S. and Puerto Rico as of April 1 (Census Day), the PES samples excluded people living in group quarters, such as prisons and college dormitories. The PES sample for the U.S. national population also excluded remote areas of Alaska.

According to the Bureau, populations living in group quarter facilities can change considerably between census and PES enumeration operations, and the seasonal nature of addresses and the population throughout the year in remote areas of Alaska made it infeasible to accurately conduct necessary matching and follow-up activities. As a result, the Bureau compares PES estimates to the census counts after removing populations living in group quarter facilities and remote areas of Alaska from the census counts. According to Bureau reporting, that smaller population count for comparison purposes after removing those populations was 323.2 million, about 8 million less than the total population counted in the U.S. in the 2020 Census (331.4 million).

The Bureau has also used its separate Demographic Analysis method to estimate net coverage errors in the decennial census since 1960. Demographic Analysis estimated the national population count by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin independently from 2020 Census data with current and historical vital statistics (i.e., birth and death records), data on international migration, and Medicare enrollment records. The Bureau published its 2020 Demographic Analysis population estimates in December 2020 and the comparisons to the 2020 Census results in March 2022.

In addition, three outside organizations worked with the Bureau to review the quality of the 2020 Census: the NASEM Committee on National Statistics, the American Statistical Association, and the JASON group (an independent group of scientists that advises the U.S. government on science and technology). NASEM published its final report on the quality of the 2020 Census in October 2023.[11] We also previously reported on some of the related findings and recommendations that these organizations made to the Bureau.[12]

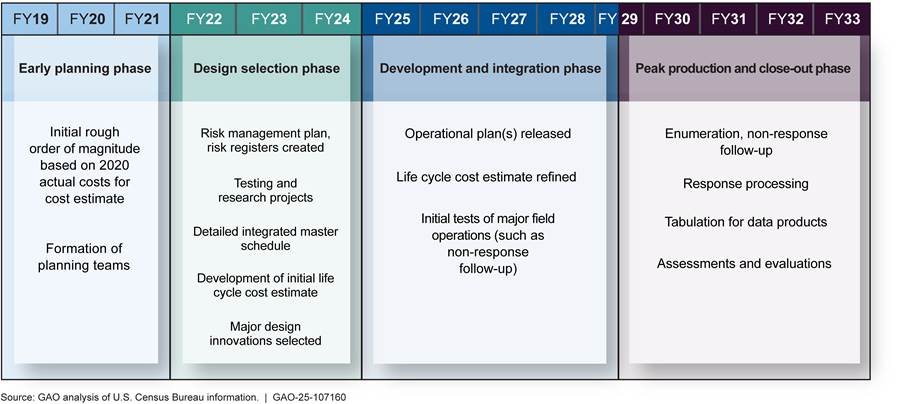

Planning for the 2030 Census has been underway since fiscal year 2019 (see fig. 2). This process includes planning research projects to inform the 2030 operational design.

Accuracy of the 2020 Census National Population Count Was Consistent with the Previous Census, but Subnational Coverage Errors Persist

Coverage Error for the 2020 National Population Count Was Not Statistically Significant

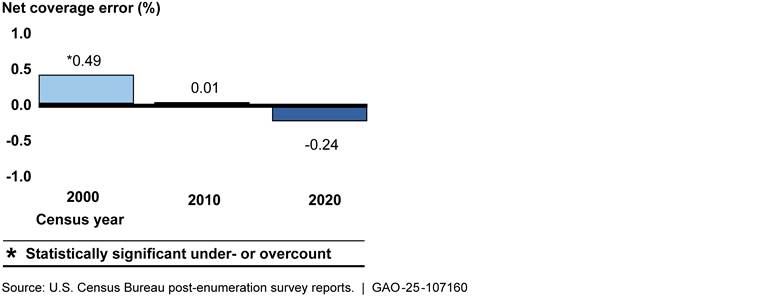

The PES estimated no statistically significant net coverage error in the count of persons at the national level in the 2020 Census.[13] The Bureau reported that this finding was consistent with results in 2010 (see fig. 3). For Puerto Rico, the PES estimated overcounts in 2020 (5.66 percent) and 2010 (4.5 percent). The Bureau did not publish PES estimates for Puerto Rico for the 2000 Census.

Figure 3: The National Population Net Coverage Errors Were Not Statistically Significant in the 2020 and 2010 Censuses

Note: The net coverage error percentages of the populations that we present have standard error percentage points of 0.20 in 2000, 0.14 in 2010, and 0.25 in 2020. Statistical significance is at the 90 percent confidence level.

Coverage Error Varied by Region and State

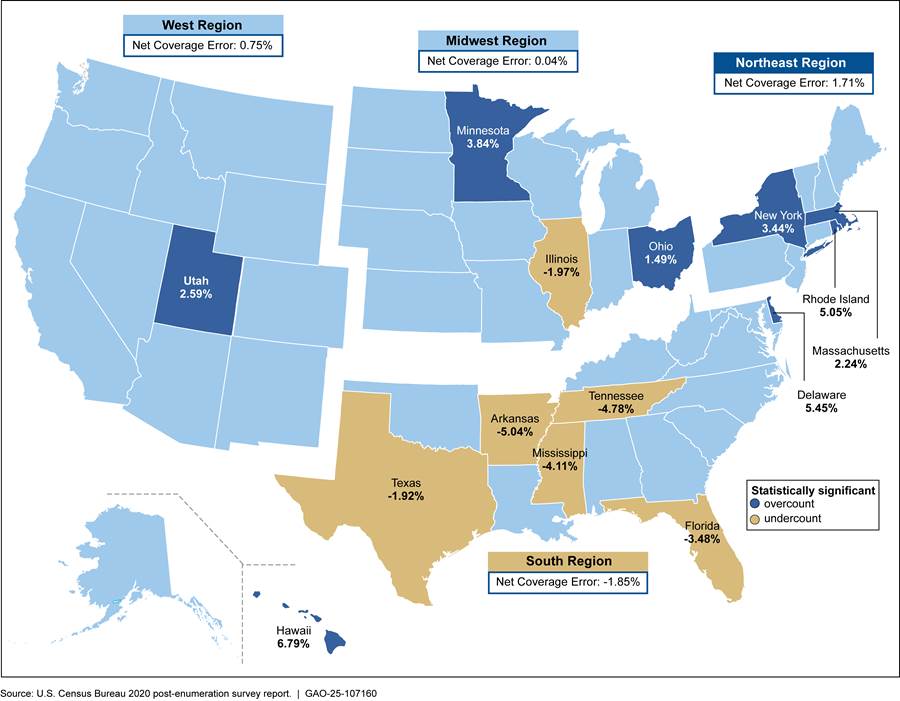

The 2020 PES estimated statistically significant net coverage errors in some regions and states (see fig. 4).[14] The PES estimated that the Northeast region was overcounted and that the South was undercounted in the 2020 Census. In addition, the PES estimated statistically significant net coverage errors in 2020 for 14 states. For the 2010 Census, the PES estimated that the Midwest was overcounted and did not estimate an undercount or overcount for any state.

For the 2020 Census, the PES estimated that

· six states were undercounted (Arkansas, Florida, Illinois, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Texas), five of which were in the South region; and

· eight states were overcounted (Delaware, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Utah).

Figure 4: Two Regions and 14 States Had Statistically Significant Net Coverage Errors in the 2020 Census

Note: The net coverage error percentages of the populations that we present have standard error percentage points of 0.49 or less for regions and 2.82 or less for states. Statistical significance is at the 90 percent confidence level.

Historical Coverage Errors Persisted for Some Subgroups

Subgroups such as racial and ethnic minorities, children, and renters are more likely to be undercounted by the census relative to other subgroups, as we previously reported.[15] The 2020 PES estimated that historical undercounts and overcounts persisted in the 2020 Census for certain subgroups in the U.S. and Puerto Rico.[16] For example:

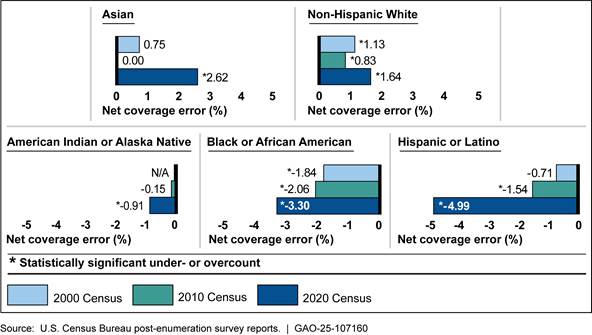

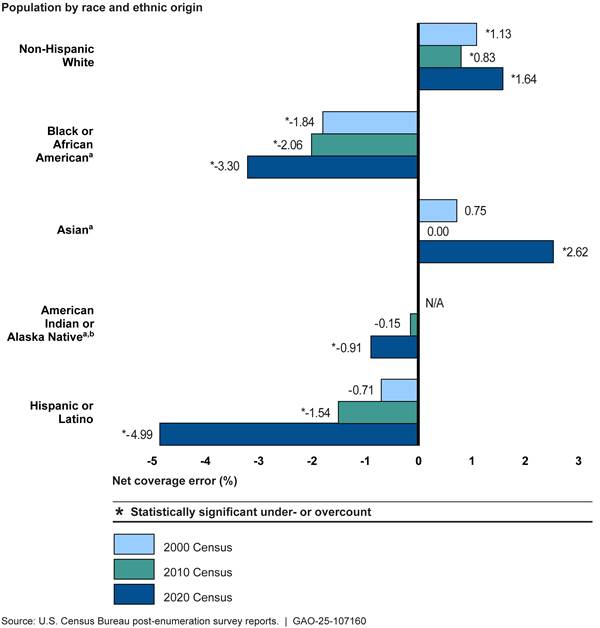

· Race and ethnic origin. The PES estimated statistically significant coverage errors for racial and ethnic subgroups in the 2020 Census (see fig. 5). This included undercounts of Black or African American persons and American Indian and Alaska Native persons on reservations. According to a March 2022 Bureau presentation, overcounts increased for non-Hispanic White persons in the 2020 Census relative to the 2010 estimate.[17] Meanwhile, undercounts increased for Hispanic or Latino persons.

Figure 5: Historical Under- and Overcounts Persisted for Some Race and Ethnic Populations in the 2020 Census

Note: The net coverage error percentages of the populations that we present have standard error percentage points of 0.68 or less in 2000, 0.71 or less in 2010, and 0.77 or less in 2020. Statistical significance is at the 90 percent confidence level.

aThis race category includes respondents who selected multiple race options in 2020 or 2010 and may be included in more than one category. In 2000, the Bureau reported estimates for race and ethnic origin categories as mutually exclusive.

bDue to methodological changes in how the Bureau defined and reported this category, the Bureau’s post-enumeration survey report did not include an equivalent estimate of net coverage error for the American Indian or Alaska Native subgroup in 2000.

According to the Bureau, the 2020 PES did not produce estimates for Puerto Rico by race and ethnic origin due in part to almost all people in Puerto Rico being classified as Hispanic.

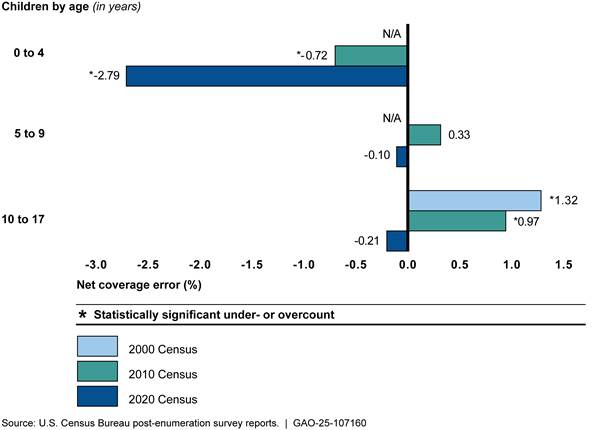

· Age and sex. According to PES estimates, the youngest children (ages 0 to 4) were undercounted in 2020 and 2010 (see fig. 6). The PES estimated no statistically significant net coverage error for children in the 5 to 9 age range in 2020 or 2010. Children in the 10 to 17 age range were overcounted in 2010 and 2000, but the PES estimated no statistically significant net coverage error for the group in 2020.

Notes: The net coverage error percentages of the populations that we present have standard error percentage points of 0.41 in 2000, 0.40 or less in 2010, and 0.64 or less in 2020. Statistical significance is at the 90 percent confidence level.

The Bureau’s post-enumeration survey report included a net coverage error percentage estimate for the 0 to 9 age range (0.46) in 2000, which was not found to be statistically different from zero.

In 2020, the Bureau’s Demographic Analysis method estimated larger net undercounts of children ages 0 to 4 (-5.4 percent) and 5 to 9 (-1.4 percent) than did the PES.[18] According to the Bureau, Demographic Analysis is a better approach for assessing the census counts of younger cohorts of children because the estimate is primarily sourced from official U.S. birth records rather than interviews. Bureau officials consider the birth record system fully complete with limited errors.

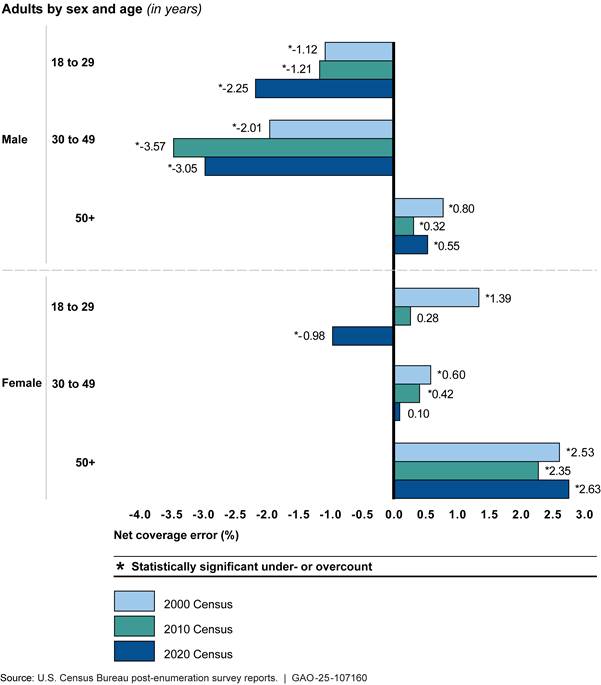

In addition, men and women ages 18 to 29 were undercounted in 2020 according to the PES (see fig. 7). While the PES estimated net undercounts for these subgroups, Demographic Analysis estimated net overcounts. In a 2023 report, NASEM concluded that this difference is likely because the PES excluded university housing (a type of group quarters) from its sample.[19] NASEM concluded that by excluding a segment of the adult population from its sample, the Bureau’s 2020 PES estimates for young adults could not capture problems the Bureau faced in the 2020 Census counting those facilities during the pandemic.

Further, according to the PES, men under 50 years of age continued to be undercounted in 2020, as they were in 2010 and 2000. The PES estimated that overcounts of both men and women over 50 years of age similarly persisted in 2020.

Note: The net coverage error percentages that we present have standard error percentage points of 0.63 or less in 2000, 0.45 or less in 2010, and 0.58 or less in 2020. Statistical significance is at the 90 percent confidence level.

For Puerto Rico, the only age and sex subgroups for which the 2020 PES estimated statistically significant net coverage errors were overcounts of women in the 30 to 49 (4.88 percent) and 50 and over (10.96 percent) age ranges, and of men over 50 years of age (8.26 percent). The 2010 PES also estimated overcounts for these subgroups.

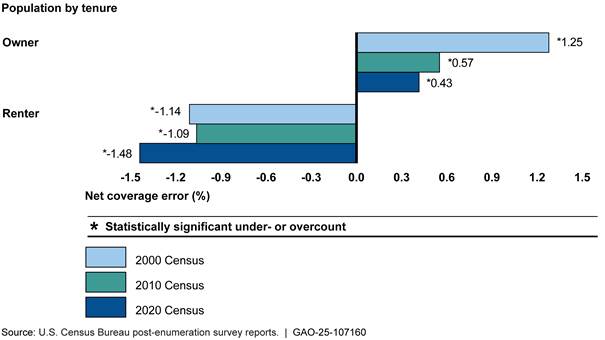

· Tenure. The 2020 PES estimated overcounts and undercounts of subgroups based on homeownership (i.e., owners compared to renters) that were consistent with previous censuses. Owners continued to be overcounted and renters continued to be undercounted (see fig. 8).

Figure 8: Renters Continued to Be Undercounted while Owners Continued to Be Overcounted in the 2020 Census

Note: The net coverage error percentages that we present have standard error percentage points of 0.36 or less in 2000, 0.30 or less in 2010, and 0.53 or less in 2020. Statistical significance is at the 90 percent confidence level.

For Puerto Rico, the 2020 PES estimated an overcount of owners (8.59 percent), and the estimate for renters was not statistically significant. Both owners and renters were overcounted in 2010.

Data Quality May Have Declined Somewhat in 2020

According to NASEM’s 2023 report, certain indicators of data quality show that some types of census responses were generally of lower quality in 2020.[20] For example, one such indicator is item nonresponse rate (i.e., when respondents do not answer certain census questions). NASEM reported that during the Bureau’s operation to follow up with people who did not submit a census questionnaire in 2020, item nonresponse rates were higher for questions regarding demographic characteristics such as age or date of birth, race, and ethnicity than they were in 2010. This was especially true for proxy respondents (i.e., someone other than a household member) but also for some household members. Relatedly, NASEM found that the Bureau also had to impute missing information using statistical methods at higher rates in 2020.

According to NASEM reporting, the 2020 Census generally had lower quality data on race, ethnicity, and age relative to 2010.[21] For example, the Bureau reported higher rates of missing and imputed responses in the 2020 Census for race and ethnic origin characteristics, especially for proxy responses, which the Bureau considers to be of lower quality than self-responses. NASEM also reported that the 2020 Census had higher rates of reported ages ending in 0 and 5 than would be expected based on known birth, death, and migration patterns. According to NASEM, this rate was approximately 2.5 times higher for ages between 23 and 62 in 2020 compared to 2010.

NASEM said this was likely due to the phenomenon of proxy respondents estimating the ages of others for whom they are providing a census response. According to NASEM, programs that use these detailed data will be less accurate, and the error in the demographic data is likely to compound when used to produce population estimates and projections, especially for small subgroups or small geographic areas.

NASEM also compared certain operational measures of the PES from 2020 and 2010 and reported that they may indicate that the overall quality of the 2020 PES is lower as well.[22] For example, one measure was the rate of households that PES data collection could not contact or that refused a PES interview. The Bureau reported that this rate was over four times higher in 2020 (16.8 percent) relative to 2010 (3.7 percent).[23] The Bureau also reported that the rate of people in the PES sample having at least one imputed characteristic was higher in 2020 (15.7 percent) relative to 2010 (6.6 percent).[24]

The Pandemic and Long-standing Challenges Potentially Affected 2020 Census Coverage with Implications for Uses of Data

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Other Challenges Affected the Bureau’s and Public’s Actions

The 2020 Census faced a number of long-standing challenges, in addition to ones that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic. These challenges affected the Bureau’s decisions and how the public engaged with the census, as we previously reported. The following list illustrates examples of challenges that may have affected census results and measures of coverage error:

· Lockdowns and travel restrictions. Some states, territories, and tribal lands instituted lockdowns or restricted travel, which affected the Bureau’s access to the public. For example, we previously reported that enumerators could not access some tribal lands for periods of time during the pandemic.[25] As a result, these policies could have contributed to errors in enumerating certain jurisdictions or subgroups.

· Social distancing guidelines. The Bureau implemented COVID-19 social distancing guidelines for its workforce, but some guidelines may have increased the risk for incomplete data. For example, we reported that the Bureau reduced call center staffing levels during periods of high call volume and temporarily closed call centers when staff tested positive for COVID-19.[26] Some callers—particularly callers who speak languages other than English or Spanish—had longer wait times and abandoned calls at higher rates during this time.

· Public reluctance to participate. Some people are reluctant to participate in the census for various reasons, such as mistrust of the government.[27] According to the Bureau’s February 2024 report about how COVID-19 affected census operations, many people were concerned about contracting COVID-19 and it was difficult to persuade them to engage with enumerators.[28] For example, the 2020 PES had higher rates of people not responding to interviews and, as a result, higher rates of imputed data, compared to 2010. According to the same report, the ability to respond to the 2020 Census by internet, phone, or mail may have helped mitigate this challenge. Bureau data show that the national self-response rates were similar in 2010 (66.5 percent) and 2020 (66.3 percent).

· Late design changes and compressed time frames. The pandemic led the Bureau to suspend activities, shift schedules for the PES and other operations, and shorten the time allotted for processing data after collecting them, among other things, as we previously reported.[29] The Bureau also shortened time frames to review data to try to deliver apportionment data to the President by the statutory deadline of December 31, 2020.[30] However, lawsuits and other concerns over the enumeration led to additional schedule changes, with the Bureau releasing the data on April 26, 2021.[31] We previously reported that late design changes and compressed time frames can affect census quality and the ability to ensure an accurate count.[32]

· Hiring and retention issues. Prior to the pandemic, we reported that the Bureau was experiencing ongoing challenges with hiring and recruiting.[33] We also later reported how the pandemic exacerbated staffing challenges across various locations and Bureau operations.[34] For example, Bureau officials told us that some enumerators quit because they were worried about catching COVID-19 and that other enumerators worked more hours to make up for the hiring gap. Hiring and retention issues can lead to delayed operations and higher costs and can adversely affect data quality.

· Enumerating hard-to-count populations. The Bureau has faced a long-standing challenge to count people who can be hard to locate, contact, persuade, or interview, as we have previously reported.[35] The pandemic may have hindered the Bureau’s efforts to count these subgroups, which include young children, racial and ethnic minorities, and people who do not live in traditional housing. For example, the Bureau delayed operations to count persons experiencing homelessness by up to 6 months. The Bureau concluded in a February 2024 report that this change may have led to some of these individuals not being counted where they were located on April 1, which could have affected the accuracy of local or state counts if they moved across local or state boundaries.[36]

· Enumerating people in group quarters. The pandemic further complicated the difficult task of counting people in group quarters, such as prisons and college dormitories. For example, we reported that the Bureau found it challenging to locate points of contact at some group quarters because facilities were closed.[37] Despite recontacting thousands of facilities to get complete data, the Bureau had to impute data for persons living at group quarters for the first time in a census.

· Budgetary uncertainty. An uncertain budget environment can disrupt research and testing without adequate planning. For example, we previously reported that the Bureau cited budget constraints—such as sequestration in 2013 and continuing resolutions (i.e., laws that allow federal agencies to continue operating when their regular appropriations have not been enacted) in fiscal year 2017—as limiting research and tests for the 2020 Census.[38] We also reported that streamlining tests and research reduces the Bureau’s ability to identify and mitigate challenges that could affect data quality and accuracy.[39]

· Natural disasters. The 2020 Census contended with natural disasters such as hurricanes and wildfires. We reported that the Bureau used telephone contact and brought in enumerators from other locations to help reach displaced persons in affected areas, such as Louisiana after it was hit by a category 4 hurricane in August 2020.[40] We also reported that Bureau officials partly attributed lower rates of completion of its follow-up interviews in some geographic areas to challenges with natural disasters.[41]

Some Methodological Choices May Affect Data Quality and Accuracy

The Bureau decides which data sources and statistical methods it will use to complete and interpret census results. These decisions are the foundation for the Bureau’s reporting on the quality and accuracy of the census. For example:

· Administrative records. The Bureau expanded its use of administrative data (i.e., data collected by governments while providing services and administering programs) to conduct the 2020 Census. This expansion helped the Bureau reduce its workload of following up with people who did not submit a census questionnaire, among other benefits, as we previously reported.[42] However, according to Bureau data, enumerations based on administrative data had higher rates of information missing for individual census questions than did enumerations based on responses directly from household members. For example, the data show that 18 percent of enumerations from administrative data were missing race but less than 3 percent of self-responses were missing race.

· PES design. The Bureau’s choice of estimation method for the PES affects what the PES measures can say about census accuracy. For example, the Bureau explained in a December 2023 blog that its 2020 PES used methods that accounted for each state’s population to estimate state-level coverage errors while the PES in 2010 and 2000 estimated them more indirectly with calculations based on national and regional errors for subgroups, such as by race.[43]

The Bureau said it made this change to estimate coverage errors more accurately, but that as a result some states had large sampling errors that made the 2020 PES estimates appear less certain. A 2023 paper written by Bureau officials demonstrated that the 2010 PES would have estimated some states to be undercounted or overcounted if it had used the 2020 method to assess census accuracy.[44]

The 2023 blog also discussed the Bureau’s methods for estimating coverage errors for counties and other subgroups below the national level, such as estimates by race and ethnicity for states.[45] The Bureau said it could not use the new 2020 method for these estimations because the sample size was too small, but it was able to produce estimates for subgroups at the national level. According to NASEM’s 2023 report, subnational estimates are important because undercounts and overcounts increased for various subgroups between the 2010 and 2020 PES and these subgroups are not distributed equally across the country.[46]

· Disclosure avoidance. The Bureau made methodology changes intended to protect the confidentiality of its respondents and their data. The new technique, called differential privacy, limited statistical disclosure of personal data and helped manage privacy risks in published data products. The Bureau reported in November 2021 that this change helped protect respondent privacy in the 2020 Census, but also made data less accurate.[47] We and other stakeholders have reported on how differential privacy could affect census accuracy, particularly at smaller geographic areas.[48]

Coverage Errors Have Potential Implications for Data Uses, Including Allocating Funds to Population Subgroups

We and others have reported that errors in census data may result in potential implications for uses of the data. For example:

· Effects on apportionment. Large coverage errors at the state level could have implications for apportionment. However, the American Statistical Association in its reporting on the 2020 Census found no major anomalies to indicate census data were not fit to use for apportionment.[49] In addition, NASEM raised caution in its reporting against analyses that simulate apportionment of congressional seats using PES estimates without taking into consideration the PES design changes we discuss above.[50] Bureau officials also told us that simulating reapportionment using reported PES estimates would need to take into account the statistical uncertainty in each estimate, making the calculations much more complex than if relying on actual population counts. Regardless, the PES uses statistical sampling techniques, and the Bureau is statutorily prohibited from using such techniques to determine the population for apportionment purposes.[51]

· Effects on allocating funds. Undercounts or overcounts in decennial data can have minor implications for allocating federal funds, as we previously reported.[52] For example, our 2006 report produced simulations that showed using updated census counts would shift some program funds such as Medicaid overall among the states by a fraction of a percent.[53] However, inaccurate counts may have larger effects below the national level. For example, according to NASEM’s 2023 report, people who reside in prisons and other types of group quarters are approximately 3 percent of the national population but can be a dominant population in small localities.[54] As a result, NASEM concluded it is critical to get accurate counts of group quarters to allocate funds and other fixed resources to those small localities.

· Effects on other uses of subnational data. According to a report from the JASON group in 2022, some census stakeholders would have challenges using 2020 Census data products because of errors that resulted from the new differential privacy method.[55] In a November 2021 report, the Bureau informed users of redistricting data that very small geographic areas may have random data variations that should be aggregated into larger geographic areas before use.[56] The Bureau also informed users that the smallest geographic areas may show inconsistencies between population and housing tables.

In addition, we previously reported that census stakeholders said that the Bureau’s use of differential privacy prevented governmental units from determining population counts in specific group quarters.[57] As a result, stakeholders said it was more difficult for governmental units to challenge population counts in group quarters they believed the Bureau miscounted in the 2020 Census.

The Bureau has taken some steps that mitigate potential implications of coverage errors. Following each decennial census, the Bureau produces annual series of population estimates for the nation that many governmental programs and others use.[58] We previously reported that among other changes to produce these estimates, the Bureau integrated several sources of data—including age and sex results from its Demographic Analysis method—rather than rely solely on results from the last decennial as a basis for estimating, as it had previously.[59] Census stakeholders told us that the Bureau’s new methodology will likely improve estimates for historically undercounted subgroups, such as young children.

In addition, beginning in 2022 and continuing through mid-2023, the Bureau implemented two programs to correct for unexpected census results. These programs enabled tribal, state, and local governments to formally challenge 2020 Census results in their jurisdictions with respect to geographic boundaries, counts of housing units and associated populations, and the populations in group quarters. We previously reported on these programs and their resulting case outcomes.[60]

The Bureau also offers tribal, state, and local governments the opportunity to request and pay for a special census of their population.[61] According to Bureau guidance, a government may request a special census if it believes the community’s population size or demographic composition changed considerably after the most recent decennial census. According to the Bureau’s website, governments may submit requests for a special census through May 2027 in advance of the 2030 Census.

The Bureau’s Plans for 2030 Leverage Insights from 2020 Census Coverage Challenges

As of October 2024, the Bureau’s website describes plans for over 50 research projects and related efforts to help design the 2030 Census. Some of these plans incorporate lessons the Bureau has learned from the 2020 Census, including challenges related to coverage errors. In December 2023, the Bureau provided us with documented lessons learned from the 2020 Census that could help the agency identify areas to improve upon for 2030.[62] We had previously reported that assessing design changes for 2020 operations could help the Bureau determine which decennial processes were efficient and worthy of future consideration and which may have had adverse effects that should be avoided in future censuses.[63]

We identified examples of the Bureau’s planned research projects and other efforts to improve accuracy in the 2030 Census across four categories:

· Public engagement. Further stakeholder outreach could benefit the 2030 effort, according to reports from us and other oversight bodies.[64] The Bureau’s planned research projects for 2030 include engaging various stakeholders to improve its group quarters operations. For example, one Bureau project involves working with organizations on data collection strategies for group quarters and transitory locations (e.g., campgrounds and motels) and developing a web page and advertisements tailored for those locations, among other things. According to the Bureau, this outreach could identify ways to improve data collection efforts and better encourage census participation among people who reside in these areas.

In addition, the Bureau’s planned projects include researching tailored contact strategies for individual housing units based on their characteristics and the potential for a mass texting campaign to announce Census Day (April 1). These and other planned research projects would target outreach to people who are difficult for the Bureau to locate, contact, persuade, or interview and encourage them to self-respond to the census.

· Administrative records. We and other oversight bodies have reported on the strengths and limitations of the Bureau increasing its reliance on administrative data to conduct the decennial census and how the Bureau should continue researching the use of these sources.[65] The Bureau plans to further expand its research and use of administrative data for the 2030 Census with multiple research projects. For example, the Bureau will research how to use administrative data to add people into households that a census response may have missed. The Bureau will also research how to remove people who were erroneously included in a response. According to the Bureau, benefits from this research could help mitigate the persistent undercount of certain subgroups, such as young children and renters.

· PES design. Unique pandemic-related challenges complicated the Bureau’s ability to collect data in the field, according to our reports and reports from NASEM and the Bureau.[66] In October 2024, Bureau officials said they had not made final decisions for the design of the 2030 PES. However, the Bureau’s planned projects for 2030 include researching how to rely less on in-person interviews during its PES operation to obtain responses to questions, such as by increasing reliance on administrative records and possibly allowing people to use the internet to self-respond.

In addition, the Bureau is considering a range of other ways to redesign the 2030 PES to measure coverage errors and learn more about why people are missed. A preliminary internal Bureau planning memorandum discusses a number of considerations including potential changes in the size of the PES sample and possible additional fieldwork to ask respondents to the PES supplemental questions to help learn why census errors occurred.

· Operations. We previously recommended that the Bureau develop a plan to improve the resiliency of its 2030 Census research and testing activity in response to Bureau-identified budget uncertainty.[67] As of October 2024, the Bureau had taken some steps to improve the development, execution, and oversight of its budget. We will continue to monitor the Bureau’s progress in implementing this recommendation. In addition, the American Statistical Association in its September 2021 report recommended that the Bureau prioritize evaluating and reporting on data quality before releasing data products for the next census.[68] The Bureau subsequently created a new office to oversee the quality efforts in the 2030 Census.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Commerce for review and comment. The Bureau provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Commerce, the Director of the U.S. Census Bureau, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Yvonne D. Jones at (202) 512-6806 or by email at jonesy@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix I.

Yvonne D. Jones

Director, Strategic Issues

GAO Contact:

Yvonne D. Jones, (202) 512-6806 or jonesy@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments:

In addition to the contact named above, Ty Mitchell (Assistant Director), Ralanda Sasser (Analyst-in-Charge), Matthew Holly, Carl Barden, Robert Gebhart, Jeff A. Larson, Lisa Pearson, Robert Robinson, Amber Sinclair, and Peter Verchinski made significant contributions to this report.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]The Bureau is required by law to include each state, the District of Columbia, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands in its nationwide decennial census count. The Secretary of Commerce may also, with the Secretary of State’s approval, include American Samoa. 13 U.S.C. § 191(a).

[2]For examples of prior reports, see GAO, 2020 Census: Bureau Released Apportionment and Redistricting Data, but Needs to Finalize Plans for Future Data Products, GAO‑22‑105324 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 14, 2022); 2020 Census: The Bureau Concluded Field Work but Uncertainty about Data Quality, Accuracy, and Protection Remains, GAO‑21‑206R (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 9, 2020); 2020 Census: Census Bureau Needs to Assess Data Quality Concerns Stemming from Recent Design Changes, GAO‑21‑142 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 3, 2020); 2020 Census: Recent Decision to Compress Census Timeframes Poses Additional Risks to an Accurate Count, GAO‑20‑671R (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 27, 2020); 2020 Census: COVID-19 Presents Delays and Risks to Census Count, GAO‑20‑551R (Washington, D.C.: June 9, 2020); 2020 Census: Initial Enumeration Underway but Readiness for Upcoming Operations is Mixed, GAO‑20‑368R (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 12, 2020); and 2020 Census: Status Update on Early Operations, GAO‑20‑111R (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 31, 2019).

[3]For example, see GAO, 2020 Census: Actions Needed to Address Challenges to Enumerating Hard-to-Count Groups, GAO‑18‑599 (Washington, D.C.: July 26, 2018); 2010 Census: The Bureau’s Plans for Reducing the Undercount Show Promise, but Key Uncertainties Remain, GAO‑08‑1167T (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 23, 2008); and Procedures to Adjust 1980 Census Counts Have Limitations, GGD-81-28 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 24, 1980).

[4]Group quarters are places where people live or stay, in a group living arrangement, that are owned or managed by an entity or organization providing housing and/or services for the residents. These include correctional facilities, nursing homes, college housing, shelters for people experiencing homelessness, and military quarters.

[5]The Bureau has referred to its post-enumeration survey-based coverage measurement program by different names across the decennials. In 2000, it was called Accuracy and Coverage Evaluation. In 2010, it was called Census Coverage Measurement. In 2020, it was called Post-Enumeration Survey (PES). For the purposes of this report, we refer to every such coverage measurement program as a PES.

[6]U.S. Const., art. I, § 2, cl. 3.

[7]To estimate the actual population size, the PES uses a dual system estimation technique that matches information from the independent survey of the sample population to census results. This technique allows the Bureau to determine who was counted in (1) the census only, (2) the PES sample only, and (3) both the census and the PES, which serves as the basis for statistical PES estimates.

[8]The Bureau did not publish PES estimates for Puerto Rico for the 2000 Census.

[9]These imputations generally represent people for whom the Bureau did not obtain information on their relationship to the head of the household, sex, age or date of birth, Hispanic origin, and race. In the Bureau’s 2000 and 2010 PES reports, a statistically significant net coverage error with a negative (positive) value indicated an overcount (undercount). However, for the purposes of this report, all statistically significant net coverage errors with a negative (positive) value indicate an undercount (overcount).

[10]Due to small population sampling constraints, the Bureau does not conduct an independent assessment of the accuracy of decennial data for American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, or the U.S. Virgin Islands as it does for the U.S. and Puerto Rico. As a result, there are no 2020 PES estimates for these territories.

[11]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census: Final Report (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2023).

[13]Statistical significance for estimates of net coverage error percentages was reported at the 90 percent confidence level for the 2020, 2010, and 2000 censuses.

[14]For data presentation purposes, the Bureau treats the District of Columbia as the statistical equivalent of a state.

[16]For Puerto Rico, the PES estimated no undercounts and some large overcounts relative to analogous categories for the U.S. However, the Bureau reported that due in part to its small sample size, there is more uncertainty in the PES estimates for Puerto Rico.

[17]U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Census Data Quality Results: Post-Enumeration Survey and Demographic Analysis, March 10, 2022, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/newsroom/press-kits/2022/20220310-presentation-quality-news-conference.pdf.

[18]The Bureau’s Demographic Analysis method estimates a range of population counts (low, middle, and high) to account for uncertainty in the data, methods, and assumptions used. The numbers cited here are middle estimates for the 0 to 4 and 5 to 9 age ranges, but the statement is true for all estimates in the range.

[19]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census.

[20]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census.

[21]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census.

[22]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census.

[23]U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Post-Enumeration Survey Estimation Methods: Missing Data for Person Estimates (Washington, D.C.: May 19, 2022).

[24]U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Post-Enumeration Survey Estimation Methods: Characteristic Editing and Imputation (Washington, D.C.: May 19, 2022).

[28]U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Census Topic Report: Potential Quality Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 28, 2024).

[29]GAO‑21‑142; 2020 Census: A More Complete Lessons Learned Process for Cost and Schedule Would Help the Next Decennial, GAO‑23‑105819 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 2, 2023).

[30]The Bureau is required by law to count the population as of April 1 (Census Day) and deliver state population counts to the President by December 31 in order to determine the number of congressional seats apportioned to each state. 13 U.S.C. § 141(a)-(b). The Bureau is also required by law to deliver population counts to the states within 1 year of Census Day for redistricting purposes. 13 U.S.C. § 141(c).

[31]For example, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California required the Bureau to extend its operation that follows up with people who did not submit a census questionnaire. See Ross v. National Urban League, 141 S. Ct. 18 (2020).

[35]GAO, 2020 Census: Update on the Census Bureau’s Implementation of Partnership and Outreach Activities, GAO‑20‑496 (Washington, D.C.: May 13, 2020).

[36]U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Census Topic Report.

[37]GAO, Decennial Census: Bureau Should Assess Significant Data Collection Challenges as It Undertakes Planning for 2030, GAO‑21‑365 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 22, 2021).

[38]GAO, 2020 Census: Lessons Learned from Planning and Implementing the 2020 Census Offer Insights to Support 2030 Preparations, GAO‑22‑104357 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 11, 2022).

[42]GAO, 2020 Census: Innovations Helped with Implementation, but Bureau Can Do More to Realize Future Benefits, GAO‑21‑478 (Washington, D.C.: June 14, 2021).

[43]U.S. Census Bureau, “Recommendations Regarding the Use of the 2020 Post-Enumeration Survey Coverage Results in the Vintage 2023 Population Estimates” (Dec. 18, 2023), accessed September 17, 2024, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2023/12/recommendations-2020-pes-coverage-results-in-vintage-2023-pop-estimates.html.

[44]Kennel, Tim, Scott Konicki, and Krista Heim, “Impact of Synthetic Bias on Estimates of State-Level 2010 Census Coverage Error” (in proceedings of the 2023 Joint Statistical Meetings, American Statistical Association, Washington, D.C., August 2023).

[45]U.S. Census Bureau, “Recommendations Regarding the Use of the 2020 Post-Enumeration Survey Coverage Results in the Vintage 2023 Population Estimates.”

[46]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census.

[47]U.S. Census Bureau, Disclosure Avoidance for the 2020 Census: An Introduction (Washington, D.C.: November 2021).

[48]GAO‑22‑105324; JASON, Consistency of Data Products and Formal Privacy Methods for the 2020 Census, (McLean, VA: The MITRE Corporation, 2022); and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census.

[49]American Statistical Association, “2020 Census State Population Totals: A Report from the American Statistical Association Task Force on 2020 Census Quality Indicators” (September 2021), accessed September 18, 2024. https://www.amstat.org/asa/files/pdfs/pol-cqi-task-force-final-report.pdf.

[50]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census.

[51]13 U.S.C. § 195; see Utah v. Evans, 536 U.S. 452 (2002); Department of Commerce v. United States House of Representatives, 525 U.S. 316 (1999).

[52]See GAO, Formula Grants: Census Data Are among Several Factors That Can Affect Funding Allocations, GAO‑09‑832T (Washington, D.C.: July 9, 2009); 2010 Census: Population Measures Are Important for Federal Funding Allocations, GAO‑08‑230T (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 29, 2007); Federal Assistance: Illustrative Simulations of Using Statistical Population Estimates for Reallocating Certain Federal Funding, GAO‑06‑567 (Washington, D.C.: June 22, 2006); Using Census Data for Funds Allocations, GAO/GGD‑98‑132R (Washington, D.C.: May 29, 1998); and Formula Programs: Adjusted Census Data Would Redistribute Small Percentage of Funds to States, GAO/GGD‑92‑12 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 7, 1991).

[54]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census.

[55]JASON, Consistency of Data Products.

[56]The Bureau said this was also the case in 2010 and 2000. U.S. Census Bureau, Disclosure Avoidance for the 2020 Census.

[57]GAO, 2020 Census: The Bureau Adapted Approaches for Addressing Unexpected Results and Developing Annual Population Estimates, GAO‑24‑106594 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 1, 2024).

[58]Annual population estimates are authorized by 13 U.S.C. § 181, which requires, to the extent feasible, the production of “current data on total population and population characteristics” for each state, county, and local unit of general purpose government which has a population of 50,000 or more. The Bureau produces population estimates of the U.S., its states, counties, cities, and towns, as well as for the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Additionally, the Bureau produces demographic components of population change (births, deaths, and migration) and housing unit estimates at the national, state, and county levels of geography.

[61]According to the Bureau’s website, the following types of governments are eligible for a special census so long as their state legislation allows for it: (1) tribal areas, including federally recognized Tribes with a reservation and/or off-reservation trust lands, Alaska Native Regional Corporations, and Alaska Native villages; (2) states or equivalent entities (e.g., D.C., Puerto Rico); (3) counties or equivalent entities (e.g., boroughs, parishes, municipios); (4) minor civil divisions (e.g., townships); (5) consolidated cities; and (6) incorporated places (e.g., villages, towns, cities).

[64]GAO‑22‑104357; American Statistical Association, “2020 Census State Population Totals;” and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census.

[65]GAO, 2020 Census: Bureau Is Taking Steps to Address Limitations of Administrative Records, GAO‑17‑664 (Washington, D.C.: July 26, 2017); U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Inspector General, Lessons Learned from the 2020 Decennial Census, OIG-22-030 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 14, 2022); and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census.

[66]GAO‑21‑365; GAO‑21‑478; and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Assessing the 2020 Census; and U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Census Topic Report.

[68]American Statistical Association, “2020 Census State Population Totals.”