DEFENSE HEALTH CARE

DOD Should Monitor Mental Health Screenings for Prenatal and Postpartum TRICARE Beneficiaries

Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Alyssa M. Hundrup at hundrupa@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107163, a report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

DOD Should Monitor Mental Health Screenings for Prenatal and Postpartum TRICARE Beneficiaries

Why GAO Did This Study

TRICARE provides health care to about 9.5 million eligible beneficiaries. In fiscal year 2023, there were about 89,000 births among TRICARE beneficiaries. Research shows mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety are the most common complications that develop during the perinatal period. Mental health is a critical part of military readiness. Factors such as isolation from social support networks may place military beneficiaries at risk of developing perinatal mental health conditions.

A report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review issues related to perinatal mental health in the military. This report examines the screening of TRICARE beneficiaries for perinatal mental health conditions in direct and private sector care.

GAO reviewed a generalizable sample of 291 service members’ medical records that had a live birth in a military medical treatment facility in fiscal year 2022—the most recent year for which complete data were available. GAO reviewed DHA documents, two contractor reviews, and relevant laws. GAO also interviewed DHA officials and contractor representatives.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to DHA to routinely monitor the frequency of perinatal mental health screenings for TRICARE beneficiaries and take corrective actions as needed. DOD partially concurred with both recommendations. As discussed in the report, GAO maintains that the recommendations are warranted.

What GAO Found

The Department of Defense’s (DOD) Defense Health Agency (DHA) oversees the TRICARE program that provides health care to beneficiaries—active-duty service members and their dependents. Beneficiaries receive care in military medical treatment facilities (direct care) and through civilian providers, generally administered by two managed care support contractors (private sector care). This care includes addressing mental health conditions that occur during and up to 1 year after pregnancy, known as the perinatal period.

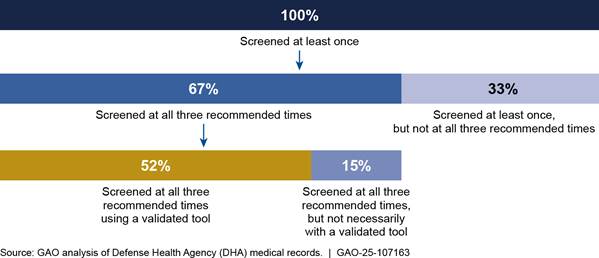

GAO estimates that 52 percent of the 6,151 service members who delivered through direct care in fiscal year 2022 received DHA’s three recommended perinatal mental health screenings. These screenings used one of two DHA-recommended tools and were performed at DHA’s specified time intervals. All service members were screened at least once during their perinatal period.

Note: The percentages in the figure represent those screenings that were conducted in accordance with DHA recommendations. GAO reviewed medical records for a random sample of 291 service members with live births in direct care—in a military medical treatment facility—in fiscal year 2022 out of a total population of 6,151. Estimates in this figure have a margin of error within plus or minus 6 percent at the 95 percent confidence interval.

For TRICARE beneficiaries in private sector care, two 2022 DHA contractor reviews showed significantly lower screening rates than direct care. For example, one contractor found that 30 percent of beneficiaries were screened at least once, and about 6 percent were screened more than once.

GAO found that DHA does not monitor or direct its contractors to monitor the frequency of perinatal mental health screenings in direct or private sector care. DOD has indicated that screening is its main prevention strategy for this high-risk group. Missing screenings could result in undiagnosed and untreated perinatal mental health conditions in TRICARE beneficiaries. By routinely monitoring the frequency of screenings in direct and private sector care, and taking corrective actions as needed to ensure adherence to DHA’s recommendations and evidence-based practices, DHA can help ensure that beneficiaries consistently receive high-quality care.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

DHA |

Defense Health Agency |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

EPDS |

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale |

|

PHQ-2 |

Patient Health Questionnaire-2 |

|

PHQ-9 |

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 22, 2025

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Department of Defense’s (DOD) military health system provides health care services to about 9.5 million eligible beneficiaries—including active-duty service members and their dependents—through the TRICARE program. Within DOD, the Defense Health Agency (DHA) manages and oversees TRICARE for all beneficiaries. These beneficiaries may receive health care, including mental health care, at military-run hospitals and clinics known as military medical treatment facilities or from civilian providers in the private sector. Within this system, pregnancy and childbirth-related care consistently comprise the largest volume of inpatient services, accounting for about 45 percent of all hospital admissions in fiscal years 2020 through 2023. According to DOD, in fiscal year 2023, there were approximately 89,000 births among TRICARE beneficiaries.

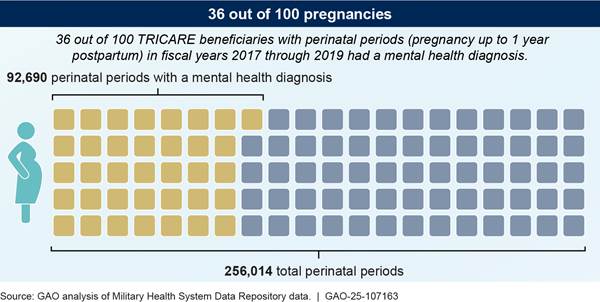

Maternal mental health conditions have reached crisis levels in the U.S. and are the most common complications that develop during and up to one year after pregnancy—known as the perinatal period—according to the Department of Health and Human Services.[1] Research shows that mental health conditions are the leading underlying cause of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States.[2] Untreated mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, that occur during the perinatal period can adversely impact individuals, infants, and their families.[3] For TRICARE beneficiaries, factors such as military assignments, deployments, and isolation from social support networks may place this group at a particular risk for developing these perinatal mental health conditions.[4] In 2022, we found that 36 percent of TRICARE beneficiaries received a mental health diagnosis during their perinatal period.[5] In its 2020 report on access to mental health care, the DOD Inspector General stated that mental health is a critical part of every service member’s medical readiness.[6]

One key way to identify and prevent perinatal mental health conditions is to conduct periodic screenings during the perinatal period, as recommended by national organizations, such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. In a 2024 report to Congress, DOD indicated that periodic standardized screening at three specific intervals is the department’s main effort to identify TRICARE beneficiaries who may be at increased risk of perinatal mental health conditions.[7]

A report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for us to review issues related to perinatal mental health in the military.[8] This report examines the screening of TRICARE beneficiaries for perinatal mental health conditions. Specifically, this report

1. describes how often DHA providers screened active-duty service members for perinatal mental health conditions and evaluates the extent to which DHA monitors this screening; and

2. describes what available data show about how often civilian providers screened TRICARE beneficiaries for perinatal mental health conditions and evaluates the extent to which DHA monitors this screening.

To describe how often DHA providers screened active-duty service members for perinatal mental health conditions, we conducted a medical record review of service members who had a live birth in fiscal year 2022.[9] To design our medical record review, we interviewed relevant DHA officials and reviewed DHA documentation, recommendations, and DOD reports related to the screening and treatment of perinatal mental health conditions.[10] We obtained DHA data on all 6,151 live births for service members who delivered in a military medical treatment facility in fiscal year 2022—the most recent year for which data were available for a full perinatal period at the time of our review. Using these data, we selected a random, generalizable sample of 291 service members’ medical records and used this sample to estimate overall screening rates for all service members with a live birth in a military medical treatment facility in fiscal year 2022.[11]

We reviewed the medical records for the full perinatal period with a focus on (1) whether perinatal mental health screening(s) occurred according to DHA recommendations and (2) the results of those screenings. We assessed the reliability of both DHA’s data on service members who delivered in military medical treatment facilities and the medical records and determined they were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report. We made this determination through interviewing knowledgeable DHA officials, reviewing supporting documentation, and checking for missing data, duplicates, and outliers. See appendix I for more details on the scope and methodology of our medical record review.

To evaluate the extent to which DHA monitors screening rates, we interviewed officials from DHA and assessed whether DHA’s oversight efforts were consistent with a national task force’s health strategy, a relevant law, and federal internal control standards.[12] We also reviewed relevant agency documentation, such as a 2023 study of focus groups on women in the services commissioned by DOD.[13]

To describe what available data show about how often civilian providers screened TRICARE beneficiaries for perinatal mental health conditions, we reviewed agency and managed care support contractor documentation and interviewed relevant officials.[14] Specifically, we reviewed two contractor reviews completed in 2022 that assessed the use and frequency of perinatal mental health screening in TRICARE beneficiaries in primary care and obstetrical settings.[15] We also interviewed DHA officials in the Managed Care Support Office responsible for contractor oversight and interviewed representatives from each contractor regarding their 2022 review results.

To evaluate the extent to which DHA monitors this screening through its contractors, we interviewed DHA officials and representatives from each contractor. We also assessed whether DHA’s oversight efforts were consistent with relevant sections of the TRICARE Operations Manual and federal internal control standards on monitoring.[16]

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our objectives.

Background

Perinatal Mental Health Conditions and Risk Factors for TRICARE Beneficiaries

Mental health conditions with perinatal onset can include a range of conditions, such as depression, anxiety, psychosis, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and more.[17] We and others have reported that TRICARE beneficiaries have a higher prevalence of perinatal mental health conditions than those in the civilian population. For example, national organizations estimate that perinatal mental health conditions affect about 20 percent of individuals annually.[18] In contrast, in May 2022, we found that about 36 percent of TRICARE beneficiaries had a mental health diagnosis during their perinatal period.[19] (See fig. 1.)

According to researchers, service members and their dependents may face increased barriers to perinatal mental health care due to military-specific factors, such as a culture that emphasizes “service before self” or the fear that seeking mental health care could negatively impact a service member’s career.[20] Further, in a 2023 study of focus groups commissioned by DOD, service members identified pregnancy as the biggest challenge they faced for a variety of reasons, such as impact on career progression and stigma.[21]

Direct and Private Sector Care for TRICARE Beneficiaries

TRICARE beneficiaries can receive perinatal care in one of two settings: direct care and private sector care. Through direct care, beneficiaries receive care at military medical treatment facilities located on or near military installations. DHA is responsible for managing care provided in these facilities. Through private sector care, beneficiaries receive care provided by civilian providers.[22] Private sector care is generally administered through two contractors that are overseen by DHA.

Within both direct care and private sector care, TRICARE beneficiaries can receive perinatal care from a variety of providers, such as obstetricians and primary care providers.[23] Service members receive priority access to care provided in military medical treatment facilities, or direct care.[24] They may also receive care from private sector providers. TRICARE beneficiaries who are dependents of service members—such as spouses or children—may receive health care services from direct care providers or from civilian providers in private sector care.

Recommendations on Screening and Follow-Up for Perinatal Mental Health Conditions

DHA recommends that direct care providers working at military medical treatment facilities conduct standardized mental health screening at three specific intervals during the perinatal period using a validated tool to detect potential perinatal mental health conditions.[25] DHA recommendations apply to direct care providers working at military medical treatment facilities.[26] The DHA recommendations are not enforceable for private sector care providers, but these providers are generally expected to follow evidence-based practices and the standard of care when administering perinatal mental health services, according to officials. Such practices and standards include routinely screening for mental health conditions like depression and anxiety using validated screening tools throughout the perinatal period and ensuring access to treatment when necessary.

Recommendations for direct care providers on perinatal mental health screening are outlined in two documents: clinical practice guidelines and practice recommendations. Both documents are based on the recommendations for screening in the perinatal period developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which DHA officials told us private sector care providers are also expected to follow.[27]

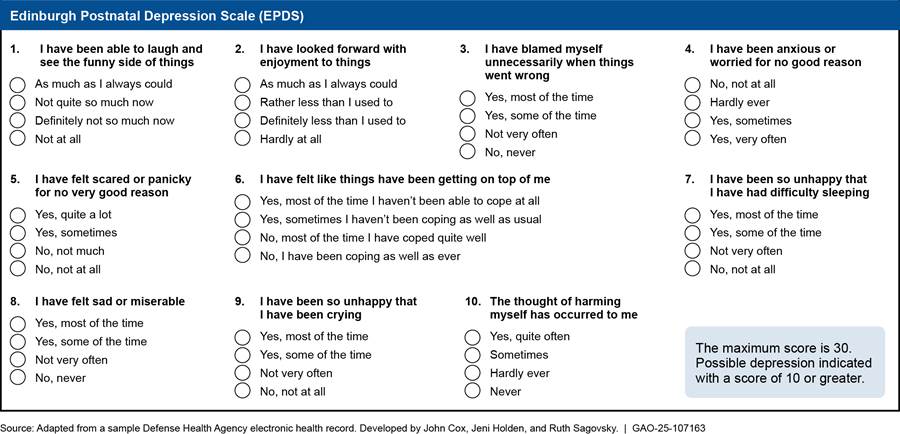

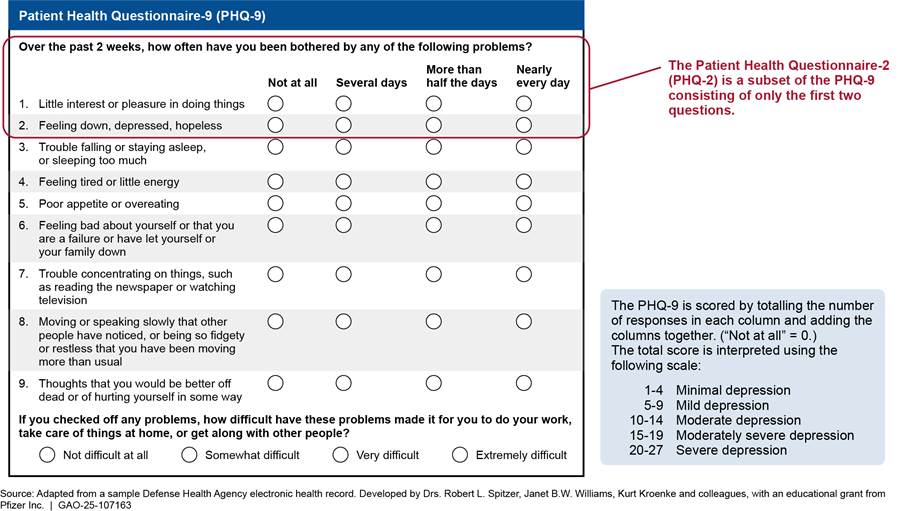

· Clinical practice guidelines. DOD’s clinical practice guidelines for pregnancy—jointly developed with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)—recommend screening for depression during pregnancy using a standardized tool that is validated for use in this population.[28] Specifically, the guidelines recommend using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) or Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) screening tools.[29] The EPDS consists of 10 self-reported questions on how the patient has felt in the past week. The PHQ-9 is a multipurpose tool that consists of nine self-reported questions where the patient rates the frequency of depressive symptoms. (See app. II for a description of these tools.) According to DHA officials, the clinical practice guidelines consolidate available research and evidence for providers.

· Practice recommendations. DHA’s practice recommendations further specify the time frames when screening should occur.[30] Specifically, screenings should occur at the first obstetrical visit, the 28-week obstetrical visit (around the start of the third trimester of pregnancy), and the initial postpartum visit. Internal to DHA, these practice recommendations provide actionable clinical guidance for providers, according to agency officials.

DHA recommendations identify certain screening thresholds or scores that indicate a patient may have a potential perinatal mental health condition. If such threshold is met (i.e., a positive screen), DHA recommends that the provider have a follow-up conversation with the patient about their screening results and consider the need for additional screening or treatment.[31] To determine whether a referral to a mental health specialist may be necessary, DHA recommendations encourage providers to consider (1) the screening outcome and threshold of the screening tool, (2) patient behavior and the discussion about the screening results, and (3) the provider’s expertise and ability to provide the needed treatment or evaluation.[32]

Various types of treatment are available for those diagnosed by a provider with a perinatal mental health condition, such as prescription medication and psychological services. For example, in prior work, we found that nearly three-quarters of TRICARE beneficiaries’ perinatal periods included use of prescription medication, psychological services, or both for diagnosed mental health conditions.[33]

About Half of Service Members Received Recommended Screenings in Direct Care, and DHA Does Not Monitor These Screenings

We estimate that about half of the service members who delivered through direct care at military medical treatment facilities in fiscal year 2022 received DHA’s three recommended perinatal mental health screenings using a validated tool. These service members received either the EPDS or PHQ-9 screening at their first pregnancy visit, 28-week visit, and initial postpartum visit. We also found that DHA relies on its providers to implement its recommendations on perinatal mental health screenings and does not monitor how frequently these screenings occur.

An Estimated 52 Percent of Service Members Who Delivered in Direct Care Received DHA’s Recommended Perinatal Mental Health Screenings in Fiscal Year 2022

Based on our medical record review, we estimate that about 52 percent of the service members who delivered through direct care at military medical treatment facilities in fiscal year 2022 received DHA’s three recommended perinatal mental health screenings using a validated tool.[34] Specifically, direct care providers conducted these screenings at the first pregnancy visit, the 28-week visit, and the initial postpartum visit using either the EPDS or the PHQ-9.[35] Additionally, an estimated 37 percent of service members were screened using either the EPDS or PHQ-9 at two of the recommended intervals, but not all three intervals. We further estimate that nearly all service members were screened at least once during the perinatal period using either the EPDS or PHQ-9. We found that screening documentation in the medical records varied, ranging from the service member’s response to a list of every screening question to a shorthand note of the score by the provider in the visit notes (e.g., “EPDS 3/30”).

In addition, we found that for an estimated 15 percent of service members who were screened at DHA’s three recommended intervals, direct care providers did not use one of the validated screening tools recommended by DHA in at least one screening. Rather, providers used a different screening tool—an abbreviated two-question version of the PHQ-9 known as the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2)—for at least one screening.[36] (See fig. 2.) Some researchers have found that the PHQ-2 may have a low sensitivity for detecting potential depression in the perinatal population. Specifically, such screening may give false negatives and fail to identify service members at heightened risk of depression.[37] In our medical record review, we found examples where service members scored low on the PHQ-2 (indicating minimal risk of depression) but scored high on either the EPDS or PHQ-9 within the same month (indicating probable depression) and initiated treatment.

Figure 2: Estimated Percentage of Service Members Screened for Perinatal Mental Health Conditions in Direct Care in Fiscal Year 2022

Note: The percentages in the figure represent those screenings that were conducted in accordance with DHA recommendations. We reviewed medical records for a random sample of 291 active-duty service members with live births in direct care—in a military medical treatment facility—in fiscal year 2022 and used that to estimate the percentage of service members receiving perinatal mental health screening out of a total population of 6,151. Estimates in this figure have a margin of error within plus or minus 6 percent at the 95 percent confidence interval.

DHA officials told us they expect and encourage their providers to implement their screening recommendations. For example, DHA officials stated that they built the validated perinatal mental health screening tools (EPDS and PHQ-9) into their electronic health record to give providers the option to standardize their data entry and documentation related to screening. According to DHA officials, DHA does not require its providers to conduct these screenings—or any other type of pregnancy related screening—which is consistent with DHA’s general practice of making recommendations rather than requirements for providers.[38]

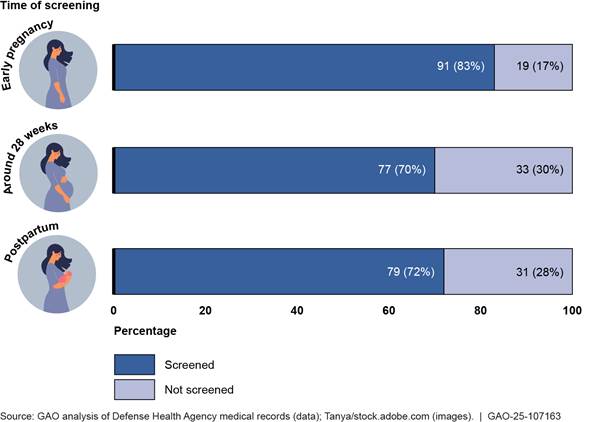

Screening intervals. Of DHA’s three recommended screening intervals, our analysis showed that service members who had a live birth in direct care in fiscal year 2022 were most likely to be screened with a validated tool at their first obstetrical appointment (an estimated 86 percent of service members), followed by the 28-week visit (an estimated 76 percent of service members), and the initial postpartum visit (an estimated 76 percent of service members).[39] For the estimated 20 percent of service members for whom we could not identify any screening (EPDS, PHQ-9, or PHQ-2) at an initial postpartum visit, either (1) the direct care provider did not document screening at the initial postpartum visit or (2) we did not find evidence that the service member attended an initial postpartum visit.[40] Perinatal mental health screening at the initial postpartum visit is important because most episodes of perinatal depression begin within 4 to 8 weeks after the infant is born, according to a publication from the National Institute of Mental Health.[41] Specifically, we did not identify an initial postpartum visit screening for 56 service members in our sample.

· For 21 of these service members in our sample, we found that they attended an initial postpartum visit, but we could not identify evidence that they were screened by their direct care provider as recommended.

· For 35 of these service members in our sample, we did not find evidence of an initial postpartum visit with a direct care provider.[42]

Additionally, we similarly found that service members in our sample with a history of mental illness (110 of 291 service members) were most likely to be screened with a validated tool at their first obstetrical visit from among the three DHA recommended screening intervals.[43] (See fig. 3.) We could not identify any screening (EPDS, PHQ-9, or PHQ-2) at the initial postpartum visit for 25 of these 110 service members. We also found that service members in our sample with a history of mental illness on average had a higher number of total validated screenings during their perinatal periods when compared with service members without a history of mental illness in our sample. This aligns with DHA guidance, which states that service members with a known history of mental health conditions should receive mental health screening more frequently than the recommended three intervals throughout the perinatal period due to the increased risk of relapse with these conditions.

Figure 3: Screening Rates for a Sample of Service Members with History of Mental Health Conditions in Direct Care in Fiscal Year 2022

Note The percentages in the figure represent those screenings that were conducted in accordance with Defense Health Agency (DHA) recommended time intervals. We reviewed medical records for a random sample of 291 active-duty service members with live births in direct care—in a military medical treatment facility—in fiscal year 2022. In our review, we identified 110 service members in our sample with a history of mental health conditions or medication. We counted screening tools recommended by DHA for use in this population. These screening rates apply only to the sample reviewed.

Screening results. We found that an estimated 38 percent of service members with a live birth in direct care in fiscal year 2022 had at least one positive screening during their perinatal period—indicating possible depression or anxiety and the need for follow up—based on our medical record review.[44] DHA recommends that any person with a positive screening have a discussion with their provider and consider evaluation by a mental health provider for additional screening and treatment, depending on patient presentation.[45] For the 112 service members in our sample with at least one positive screening, we found the following:

· Providers followed DHA recommendations for 95 of these service members. For example, in response to positive screenings, we identified provider referrals for service members to begin therapy, attend postpartum support groups, and take new medications. Some service members declined initiating treatment, according to our review of the medical records.

· Providers did not follow up as DHA recommends for 17 of these service members.[46] For these service members, there was no documentation of any follow-up conversation, referral, or other action related to their positive screening within their medical records. While a screening tool does not result in a specific mental health diagnosis, according to DOD, it does help provide early identification of service members most at risk.

DHA Does Not Routinely Monitor the Frequency of Perinatal Mental Health Screening or Provider Response to Screening Results in Direct Care

DHA does not routinely monitor how often service members in direct care are being screened for perinatal mental health conditions or whether its providers are following agency recommendations, both for the three screenings throughout the perinatal period and any appropriate follow-up action.

DHA completed one point-in-time review of perinatal mental health screening in its military medical treatment facilities in 2018. However, officials stated that DHA does not perform ongoing monitoring to ensure that perinatal mental health screenings are occurring in direct care and that providers are acting in response to positive screenings, such as making a referral for treatment when needed. In its 2018 internal quality improvement review, DHA found that around 86 percent of TRICARE beneficiaries who had a live birth during fiscal year 2017 had documentation of at least one screening in the perinatal period. Thirty-three percent of beneficiaries had three or more screenings, including PHQ-2 screenings.[47] DHA took some steps to encourage screening following this review, including adding templates of validated screening tools to its electronic health record. It also updated its recommendations for direct care providers, such as releasing more clinically focused internal practice recommendations with actionable screening guidance for providers.

In July 2024, DOD reported to the Congress that all TRICARE beneficiaries could receive standardized perinatal mental health screening at any military medical treatment facility and that the screening is conducted according to the VA/DOD clinical practice guideline.[48] DOD reported that screening and early intervention is its main strategy for identifying perinatal mental health conditions in this at-risk population.[49]

Monitoring the frequency of perinatal mental health screenings and providers’ responses to the results in direct care would align with Congress’s and DHA’s focus on standardizing the use of evidence-based care across military medical treatment facilities and with national efforts to improve perinatal mental health care.

· The National Strategy to Improve Maternal Mental Health Care, released by the Department of Health and Human Services in May 2024, recommends increased implementation of clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based interventions for perinatal mental health conditions, with universal implementation as a target.[50] The strategy identifies requiring providers in federally funded programs to adhere to clinical practice guidelines as a way to achieve this recommendation. DOD participated in the task force that developed the strategy, and the strategy lists VA/DOD’s clinical practice guidelines on the treatment and management of pregnancy among its example guidelines. However, DHA officials did not identify any current actions or plans related to the strategy.

· The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017 required the Secretary of Defense to implement a program to establish best practices for the delivery of health care, incorporate them into daily operations, and eliminate variability of care at military medical treatment facilities.[51] As part of that program, DOD is required to develop, implement, monitor, and update clinical practice guidelines at military medical treatment facilities.[52] DHA has started to develop compliance monitoring plans for 10 of its most common clinical practice guidelines. However, the guidelines on the management of pregnancy—which include DOD’s recommendations related to perinatal mental health screening—were not selected as part of the initial roll out, according to DHA officials.[53]

Routine monitoring of perinatal mental health screenings and of providers’ responses to the results in direct care would also be consistent with federal internal control standards which state that management should establish and operate monitoring activities, evaluate the results, and take corrective action to address identified deficiencies.[54] For example, if DHA monitoring shows that providers are not consistently following DHA’s perinatal mental health screening recommendations, the agency could take steps to remind providers and encourage adherence to the recommendations. Such efforts would help ensure that its direct care providers are screening TRICARE beneficiaries for perinatal mental health conditions, following up on positive results, and making referrals when indicated, consistent with agency recommendations. This is important given our finding that about half of service members received the screenings as recommended. Missing screenings or referrals for this high-risk group could result in delayed or missed identification of perinatal mental health concerns or conditions, which places both the service member and their infant at risk.

Contractor Data Show Significantly Lower Rates of Screening for TRICARE Beneficiaries in Private Sector Care, and DHA Does Not Monitor This Screening

Data from two DHA contractor reviews completed in 2022 showed significantly lower perinatal mental health screening rates for TRICARE beneficiaries in private sector care. These screening rates were particularly low compared with the screening rates we estimate for service members in direct care over a similar time period, according to our medical record review as described above. We also found that DHA does not routinely direct its contractors to monitor the frequency of perinatal mental health screening in private sector care or civilian providers’ responses to the screening results.

Contractor Data for 2022 Showed Significantly Lower Rates of Perinatal Mental Health Screening for TRICARE Beneficiaries in Private Sector Care

DHA directed its two contractors to each conduct a review to assess the use and frequency of mental health screening in perinatal populations in private sector care.[55] Based on available information in each review completed in 2022, data showed low screening rates for TRICARE beneficiaries screened by civilian providers in private sector care. Overall, data from the contractors’ reviews suggested that screening rates for TRICARE beneficiaries in private sector care were much lower than the rates we estimate for service members in direct care.

The first contractor’s review did not include overall screening rates for TRICARE beneficiaries.[56] Rather, the review analyzed separate samples based on care setting (i.e., care received in primary care or obstetrical offices). In addition, the contractor reported screening rates for beneficiaries that had both a history of mental health issues and documented treatment in their medical record. Among these, the contractor’s data showed that about 17 percent (11 of 66) of beneficiaries in primary care and 18 percent (12 of 66) of beneficiaries in obstetrical care had at least one documented mental health screening during their perinatal period. The first contractor did not provide additional results comparable to our medical record review or the second contractor report, such as the number of beneficiaries who had multiple screenings as part of its review.

The second contractor’s review found the following:

Screening rates. Contractor data showed that 30 percent of TRICARE beneficiaries (42 of 139 beneficiaries) were screened at least once by civilian providers during the perinatal period.[57] In contrast, we found that DHA providers screened 100 percent of service members at least once through our medical record review of direct care. Data from the contractor’s review further showed that about 6 percent of TRICARE beneficiaries (8 of 139 beneficiaries) had more than one screening during the perinatal period.[58] In contrast, we estimate that all service members were screened more than once in direct care, regardless of the screening tool used or time interval of the screening, based on our medical record review.[59]

Treatment results. The contractor’s review showed that about 12 percent of TRICARE beneficiaries who were screened (5 of the 42 beneficiaries screened) had a positive screening, indicating a potential perinatal mental health condition and the potential need for further evaluation. Contractor representatives told us that this is consistent with national depression rates in the civilian population. However, this rate may be lower than expected for TRICARE beneficiaries as our prior work found that 36 percent of TRICARE beneficiaries had a mental health diagnosis during their perinatal period for fiscal years 2017-2019. Additionally, in our medical record review for direct care, we found that about 38 percent of service members had at least one positive screening during their perinatal period. The contractor noted that all five of the beneficiaries who screened positive received treatment as recommended by DHA guidelines, including prescription medication for depression or anxiety and follow-up or referral for counseling with a mental health provider.

DHA officials attributed the difference in screening rates between the direct and private sector care settings to differences in management, as military medical treatment facility providers operate under the direct ownership and control of DOD and civilian providers do not. Officials told us that civilian providers are not bound by contract provisions and operate independently on matters of professional practice and judgment.[60] Further, DHA officials said that their administration of the contractors includes the receipt, review, and payment of claims for covered benefits (which include perinatal mental health screenings) but does not include direct oversight of provider practices within the nationwide standard of care. However, given the difference in screening rates we identified between direct and private sector care, the setting in which TRICARE beneficiaries obtain health care may contribute to whether they receive perinatal mental health screening.[61]

Contractor review recommendations. Both contractor reviews described above made recommendations to improve perinatal mental health screening in private sector care. For example, one review recommended a future quality improvement project to disseminate DHA’s clinical practice guidelines on perinatal mental health screening to civilian providers (see text box).

|

Recommendations from Defense Health Agency (DHA) Contractor Reviews Completed in 2022 The first contractor

recommended: 1) educating providers on the importance of screening in

perinatal populations; 2) considering ways to improve screening in the

postpartum population specifically; 3) conducting a future review to explore

the management of mental health issues in the perinatal population; and 4)

exploring strategies to minimize barriers to screening for perinatal mental

health. The second contractor recommended: 1) a future quality improvement project to disseminate the clinical practice guidelines related to mental health screening during the perinatal period, including letters to provider groups on the use of validated screening tools; and 2) additional articles in the provider newsletter to emphasize the importance of adherence to the clinical practice guidelines and increased literature for TRICARE beneficiaries in the prenatal period. |

Source: GAO analysis of DHA contractor reviews. | GAO-25-107163.

Representatives for both contractors told us that DHA did not provide guidance

or instruction regarding their results and did not direct them to implement any

corrective actions for improvement, including the reviews’ recommendations. One

contractor we interviewed voluntarily made some changes to address their

review’s recommendations, such as providing information on postpartum

depression to new parents at well-child visits, including information on when

to get screened and seek treatment. The other contractor made no changes, as

representatives told us they do not implement review recommendations unless

tasked to do so by DHA.

Although the two contractor reviews showed low perinatal mental health screening rates for TRICARE beneficiaries in private sector care, DHA has not followed up with the contractors or sought corrective action for improvement, such as reminding or encouraging civilian providers to follow evidence-based screening practices. Specifically, DHA officials said they have not initiated any quality improvement activities for contractors since the 2022 reviews or requested or conducted any additional reviews related to perinatal mental health.

DHA Does Not Routinely Direct Its Contractors to Monitor the Frequency of Perinatal Mental Health Screening or Provider Response to Screening Results in Private Sector Care

We found that DHA does not routinely direct its contractors to monitor the frequency of perinatal mental health screening in private sector care or civilian providers’ responses to the screening results. While DHA requested a one-time review of perinatal mental health screening from its contractors in 2022, it does not routinely direct its contractors to monitor perinatal mental health screening in private sector care.

According to agency officials, DHA administers TRICARE benefits—which include perinatal mental health screening—through its contractors.[62] However, agency officials told us this does not include direct oversight of how civilian providers conduct their practice (i.e., whether providers are following nationally recommended evidence-based screening practices). Although perinatal mental health screening is a covered TRICARE benefit, DHA officials said that DHA does not regularly monitor through its contractors—such as through regular data collection or other contract mechanisms—the extent to which such screening is occurring in private sector care. According to DHA officials, DHA cannot directly monitor independently operating civilian providers in the private sector. However, DHA could utilize existing contract mechanisms to monitor for quality assurance and incentivize high-quality care.[63] For example, DHA could direct the contractors to collect, monitor, analyze, and report on clinical quality data based on a core set of measures and goals. DHA officials from the office that oversees the contractors told us that perinatal mental health screening is not a currently tracked metric. However, officials told us that if perinatal mental health screening became a priority for DHA, they could require the contractors to report on this metric.

Routinely monitoring perinatal mental health screening in private sector care and providers’ responses to the screening results would align with relevant provisions of the TRICARE Operations Manual.[64] This manual specifies that the contractor shall use evidence-based processes and nationally recognized criteria and standard of care guidelines to identify and monitor all medical services, including mental health care services, as part of its medical management programs.[65] DHA officials told us that while the contractors are required to utilize a medical management program, screening for perinatal mental health conditions is not a specific contract requirement. Although perinatal mental health screening is not explicitly mentioned in the TRICARE Operations Manual, screening for mental health conditions during the perinatal period falls under nationally recognized criteria and evidence-based processes, as recommended by both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

· The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that screening for depression and anxiety take place at least three times during the perinatal period and be conducted using standardized, validated instruments.

· The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for depression in the adult population, including for pregnant and postpartum populations.

DHA officials told us that the standard of care set forth by national organizations—such as those related to perinatal mental health screening above—are recommendations and not requirements, but that civilian providers are expected to follow these recommendations. Agency officials also noted that imposing additional contract requirements may result in providers dropping from the network, which could be particularly harmful in areas already experiencing provider shortages. However, DHA officials noted some strategies or contract mechanisms the agency could take to improve perinatal mental health screening without imposing provider requirements. For example, officials said that DHA could require its contractors to track this screening in private sector care. Such a requirement would make the contractor responsible for educating its providers on an established goal and tracking the screening metrics toward that goal. DHA officials also suggested that a monetary award could be offered to the contractor upon reaching the established goal.[66]

Routinely monitoring perinatal mental health screening in private sector care and providers’ responses to screening results, and taking corrective actions as appropriate, would help DHA prevent undiagnosed and untreated mental health conditions in this particularly vulnerable population.[67] Missing screenings or referrals for this high-risk group could result in delayed or missed identification of perinatal mental health concerns or conditions, which places both the beneficiary and their infant at risk. In addition, routine monitoring of perinatal mental health screening could help ensure that TRICARE beneficiaries are more consistently screened between the direct and private sector care settings, minimizing potential differences based on the location in which an individual seeks perinatal care. This in turn would help DHA ensure its TRICARE beneficiaries in private sector care consistently receive high-quality perinatal health care.

Conclusions

Screening during the perinatal period is critical for identifying potential mental health conditions during and after pregnancy—the leading underlying cause of maternal death—especially for those in the military community, who may be at particular risk. Importantly, DHA has taken steps to increase screening, its main strategy for identifying perinatal mental health conditions. Such steps have included references to validated screening tools in its electronic health record, and screening rates have improved in recent years for service members receiving direct care.

However, direct care and especially private sector providers are not consistently screening TRICARE beneficiaries for perinatal mental health conditions, in accordance with DHA’s related recommendations and evidence-based screening practices. In the absence of routine monitoring for such screening, DHA does not know how often TRICARE beneficiaries are being screened for perinatal mental health conditions or the results of those screenings in direct or private sector care. As a result, it is limited in its ability to seek corrective actions as appropriate if deficiencies are identified.

By routinely monitoring the frequency of perinatal mental health screenings in direct care, and taking corrective actions as needed according to DHA’s recommendations, DHA can help ensure that TRICARE beneficiaries consistently receive high-quality care. Similarly, such monitoring for private sector care would better enable DHA to ensure provider adherence to evidence-based screening practices and take corrective action if deficiencies are identified. This may be especially important in light of the lower rates of screenings beneficiaries are experiencing in the private sector.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to DHA:

The Director of DHA should routinely monitor the frequency of perinatal mental health screening in direct care and take corrective action as appropriate if deficiencies are identified to help ensure provider adherence to DHA’s screening recommendations. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of DHA should routinely monitor through its contractors the frequency of perinatal mental health screening in private sector care and take corrective action if deficiencies are identified to help ensure provider adherence to evidence-based screening practices. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. The agency’s comments are reprinted in appendix III. In its comments, DOD partially concurred with both of our recommendations, expressing concerns over its ability to fully implement them.

DOD partially concurred with our first recommendation—that DHA monitor the frequency of perinatal mental health screening in direct care and take corrective action as appropriate. DOD stated that it intends to develop a process to monitor provider adherence to the screening recommendations in the department’s clinical practice guidelines. DOD noted that it anticipates implementing this recommendation, but it would require changes to its electronic health record system that may impact its timeliness. We recognize that these efforts may take time, but believe it is important to address our recommendation to ensure adequate perinatal mental health screening for TRICARE beneficiaries in direct care. DOD said DHA will report on the progress of its initiatives by April 2026. We believe that implementation of the initiatives described by DOD will address the recommendation.

DOD also partially concurred with our second recommendation—that DHA monitor the frequency of perinatal mental health screening in private sector care and take corrective action as appropriate through its contractors. DOD stated that DHA does not require its contractors to monitor the frequency of perinatal mental health screenings, but that it would request that they perform a review of a sample of records from clinic visits to assess screenings. However, DOD further stated that private sector care records may not contain complete information on the occurrence of screenings, and therefore there are limitations in what may be determined from such a review. Given these limitations, DOD stated it would conduct a cost-benefit analysis, by April 2026, to explore whether a routine review of sample records would be worthwhile. We believe it is important for DOD to routinely identify and implement a means to monitor the frequency of these screenings.

In addition, DOD stated that DHA cannot take corrective action against providers to help ensure adherence to evidence-based practices with respect to perinatal mental health screenings. DOD explained that private sector care providers are not employees or agents of DOD. Rather, they are independent and not operating under the department’s direction. DOD stated that in response to our recommendation, DHA, through its contractors, would disseminate educational materials to its network of private sector care providers, encouraging the administration of perinatal mental health screenings.

We understand the independent nature of private sector care providers. We also agree that providing educational materials may help increase screenings, which is important to help address the low numbers of screenings. However, we maintain that both recommendations are warranted. Routine monitoring, along with corrective actions as needed—including through certain contract mechanisms—would help DHA better ensure provider adherence to evidence-based perinatal mental health screening practices in the longer term.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at hundrupa@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Alyssa M. Hundrup

Director, Health Care

This appendix describes the scope and methodology for our medical record review of perinatal mental health screening of active-duty service members with a live birth in direct care in fiscal year 2022.[68] This was the most recent year for which data were available for a full perinatal period at the time of our review. We requested and obtained from DHA descriptive data on all live births among service members in direct care—in a military medical treatment facility—in fiscal year 2022. DHA retrieved these data using the Military Health System Data Repository.[69] We asked DHA to retrieve data for service members eligible for care for the full perinatal period, starting 40 weeks prior to being admitted for delivery (their estimated start of pregnancy) and extending to 12 months after discharge from their delivery (postpartum follow-up window). DHA confirmed eligibility using the Defense Eligibility and Enrollment Reporting System. DHA then filtered the data to discharges with a maternal code that indicated at least one live birth.[70] This yielded a sampling frame of 6,151 service members.

We reviewed the data for obvious errors, including duplicates and delivery dates that fell outside of our study window. We met with DHA officials to discuss the data and determined they were sufficiently reliable for our sample selection purposes. From this sampling frame, we randomly selected 300 service members for the medical record review. We excluded a total of nine records that had ongoing file issues, incomplete records, or an actual date of delivery that fell outside of our scope. Our final sample was 291 service members. Results from this sample are generalizable at the 95 percent confidence level within plus or minus 6 percentage points. Due to their smaller respective sample sizes, difference across sub-populations cannot be generalized. We confirmed that the spread of service members across military medical treatment facilities was similar to that of the full population. Our sample covered 35 of the 43 military medical treatment facilities with at least one delivery that met our inclusion criteria.

We requested and obtained the 291 service members’ full medical records for the perinatal period directly from the military medical treatment facilities in portable document format. We reviewed the files provided to ensure they contained complete information on each service member. We followed up with DHA to request additional information due to file errors or incomplete information and received additional documentation in most cases.

In addition, we reviewed both current DHA recommendations related to perinatal mental health screening and the recommendations that were in place during the time of our review and DHA’s similar internal quality review study.[71] We also interviewed officials from DHA, the agency responsible for overseeing the military medical treatment facilities. We focused our analysis on whether screening(s) occurred and at what time frame during the perinatal period, and whether a referral for treatment or further evaluation was indicated upon a positive screening score. DHA recommends screening for depression during pregnancy using a validated tool at the first pregnancy visit, the 28-week visit, and the initial postpartum visit. DHA identifies the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) as the validated tools for screening in this population. The steps that followed were first completed by an analyst and then separately confirmed by a clinical nurse consultant. Any discrepancies identified in the clinical review were discussed and resolved between the analyst and the clinical nurse consultant.

To identify the relevant time periods for each service member, we recorded the estimated date of delivery and actual date of delivery in each service member’s medical record.[72] We developed a protocol to identify each screening with a validated tool (EPDS and PHQ-9) within the perinatal period to see if DHA’s recommendations were met. For each screening identified, we recorded the date of the screening, screening tool used, provider setting type, overall screening score, and whether the service member had a positive response to a screening question related to suicidal ideation or self-harm. If the screening score met the threshold to trigger additional provider action, per DHA recommendations, we recorded whether there were any notes or documentation regarding such provider action.[73] This broadly included any documentation of a conversation, consultation, treatment, evaluation, referral, or new medication prescription related to the screening or the service member’s mental health.

Once all EPDS and PHQ-9 screenings had been identified (up to 10 per service member), we determined if the screening dates fell within DHA’s three recommended screening time frames (first obstetrical visit, around 28 weeks, and initial postpartum visit). We expanded the time frames to account for variability in service members accessing care and to ensure that we did not penalize DHA for visits that did not occur or were late.[74] If the service member’s record did not show that all three recommended screenings were conducted using the EPDS or PHQ-9, the analyst then searched the medical record and documented the details of any two-question Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) screenings that fell within the relevant screening time frames. While PHQ-2 is not listed in DHA’s recommendations specific to pregnancy or postpartum care, it is identified in the VA/DOD joint clinical practice guideline on the management of major depressive disorder. DHA officials told us that any type of provider—such as a primary care provider—can see a service member during the perinatal period. We included the PHQ-2 so that we could better identify non-obstetrics appointments that may have included some type of perinatal mental health screening. Our review was limited to information documented in the service member’s medical record. For the initial postpartum visit, if we were unable to identify a screening during this time frame, we assessed whether there was evidence that such a visit occurred. It is possible that some missed screenings were also due to missed appointments at the other screening time frames.

We also searched the service member’s medical record to determine whether the individual had a history of documented mental health issues (either a diagnosis or a prescription for a related medication). This included searching for “depression,” “anxiety,” “past medical history,” “problem list,” “behavioral health treatment history,” and “mental health history”; searching medication lists for mental health related medications; and documenting any mental health history identified through the search for screenings.

This appendix compares the two mental health screening tools DHA recommends for use in the perinatal population—The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). DHA’s recommendations are based on recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. See figures 4 and 5 below.

GAO Contact

Alyssa M. Hundrup, hundrupa@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Ray Sendejas (Assistant Director), Elaina Stephenson (Analyst-in-Charge), Summar C. Corley, Kaitlin Farquharson, and Jeanne Murphy Stone made key contributions to this report. Also contributing were Kaitlin Asaly, Joycelyn Cudjoe, Kristin Ekelund, Ying Hu, David Jones, Kate Nast Jones, Sang Lee, Amy Leone, Rich Lipinski, Diona Martyn, and Jeffrey Tamburello.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]See Department of Health and Human Services, Task Force on Maternal Mental Health: National Strategy to Improve Maternal Mental Health Care (May 2024). See also GAO, Maternal Health: HHS Should Improve Assessment of Efforts to Address Worsening Outcomes, GAO‑24‑106271 (Washington, D.C.: February 21, 2024).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, behavioral health refers to a person’s emotional, psychological, and social well-being. Mental health is a component of behavioral health, which is a broader term that includes other topics such as substance use. Throughout this report, we use the term “mental health” as we did not include substance use in our scope.

[2]S. L. Trost et al., Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017-2019 (Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). In this study, mental health conditions (including deaths related to suicide and overdose or poisoning related to substance use disorder) accounted for 23 percent of pregnancy-related deaths. The other leading causes of pregnancy-related death were hemorrhage (14 percent); cardiac and coronary conditions (relating to the heart) (13 percent); infection (9 percent); thrombotic embolism (a type of blood clot) (9 percent); cardiomyopathy (a disease of the heart muscle) (9 percent); and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (relating to high blood pressure) (7 percent).

[3]See White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis, June 2022.

[4]See M.A Thiam, ed., Perinatal Mental Health and the Military Family: Identifying and Treating Mood and Anxiety Disorders (New York, NY: Routledge, 2017). See also GAO, Defense Health Care: Prevalence of and Efforts to Screen and Treat Mental Health Conditions in Prenatal and Postpartum TRICARE Beneficiaries, GAO‑22‑105136 (Washington, D.C.: May 23, 2022).

[5]See GAO‑22‑105136.

[6]Department of Defense Inspector General, Evaluation of Access to Mental Health Care in the Department of Defense, DODIG-2020-112 (August 2020).

Medical readiness refers to the physical and mental health and fitness of military service members to perform their missions.

[7]See Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Report on the Military Health Services’ Activities to Prevent, Intervene, and Treat Perinatal Mental Health Conditions of Members of the Armed Forces and Their Dependents (Washington, D.C.: July 10, 2024).

The Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025, enacted in December 2024, requires the Secretary of Defense to carry out a program focused on improving perinatal mental health services in the military health system. This includes enhancing access to resources for identifying symptoms of perinatal mental health, brief intervention by providers, referral to care, and treatment. Pub. L. No. 118-159, tit. VII, subtit. A, § 705, 138 Stat. 1773 (2024).

[8]H.R. Rep. No. 118-125, at 194 (2023).

[9]We refer to active-duty service members as “service members” throughout this report. We focused our medical record review analysis on TRICARE beneficiaries who are service members as the majority of live births (nearly 70 percent) among this group occur in military medical treatment facilities, according to DHA data, and they receive priority access to care in these facilities. Most live births for TRICARE beneficiaries who are dependents occur in private sector care, according to DHA data. As also discussed in this report, we reviewed private sector care data to describe perinatal mental health screening for TRICARE beneficiaries who are dependents, and for the 30 percent of service members who delivered in private sector care.

[10]We reviewed both current DHA recommendations and recommendations that were in effect during the time period of our review. See, for example, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DOD), VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Pregnancy, version 3 (revised 2018); VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Pregnancy, version 4 (revised 2023); and DHA Clinical Quality Improvement Studies Working Group, Screening for Maternal Depression among TRICARE Beneficiaries: A Quality Improvement Project (2018).

[11]Data for the overall sample are generalizable at the 95 percent confidence level within plus or minus 6 percentage points. The results of our analysis of subpopulation data cannot be generalized beyond the sample of records reviewed.

[12]See Department of Health and Human Services, Maternal Mental Health’s National Strategy to Improve Maternal Mental Health Care, and GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014). Internal control is a process effected by an entity’s oversight body, management, and other personnel that provides reasonable assurance that the objectives of an entity will be achieved. We determined that the monitoring component of internal control was significant, along with the underlying principles that (1) management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate the results and (2) management should remediate identified internal control deficiencies on a timely basis, including completing and documenting corrective actions as needed.

[13]Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services, 2023 Focus Group Report (2023).

[14]Throughout this report, we refer to DHA’s two managed care support contractors as “contractors.” DHA oversees these contractors, which generally administer care provided to TRICARE beneficiaries by civilian providers.

[15]One contractor review included data from calendar years 2020-2021, and the other contractor review included data from calendar years 2019-2021. Both contractors completed their reviews in August 2022.

[16]The TRICARE Operations Manual outlines specific requirements for each contractor. DHA officials told us these requirements are periodically reviewed by DHA to determine if the contractor is meeting agency expectations. See Department of Defense, Defense Health Agency, TRICARE Operations Manual 6010.62-M, “Clinical Operations, Chapter 7 Section 4, Utilization Management,” April 2021. See also Department of Defense, Defense Health Agency, TRICARE Operations Manual 6010.59-M, “Medical Management, Utilization Management, and Quality Management, Chapter 7 Section 1, Medical Management/Utilization Management,” April 1, 2015 (Revision: C-26, May 30, 2018). We reviewed two versions of the TRICARE Operations Manual which both contain similar requirements. The 2015 version was in effect during the contract performance period we included in our review, and the 2021 version applies to the current contract performance period that began on January 1, 2025. We also reviewed two versions of the TRICARE Policy Manual over the same contract performance periods, dated 2015 and 2021. These policy manual versions also contain similar requirements. See also GAO‑14‑704G. We determined that the monitoring component of internal control was significant, along with the underlying principles that (1) management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate the results and (2) management should remediate identified internal control deficiencies on a timely basis, including completing and documenting corrective actions as needed.

[17]See GAO‑22‑105136.

[18]See, for example, American Psychiatric Association, “Pregnancy, Mental and Substance Use Conditions and Treatment: Advice from Mental Health Experts” (2023), accessed January 10, 2025, https://www.psychiatry.org/News-room/APA-blogs/Pregnancy-and-mental-health-conditions.

[19]In this report, we found that 36 percent of TRICARE beneficiaries’ perinatal periods included a mental health diagnosis in fiscal years 2017 through 2019. Data from this analysis showed that an additional 5 percent of perinatal periods included mental health prescriptions (without a diagnosis), indicating that as many as 41 percent of TRICARE beneficiaries’ perinatal periods could include a mental health condition. See GAO‑22‑105136.

[20]See Thiam, Perinatal Mental Health and the Military Family, 94. See Karen L. Weis, “Pregnancy in the Military: Importance of Psychosocial Health to Birth Outcomes,” Scientific Panel, 2016 Military Women’s Health Research Conference, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md. April 25-27, 2016. See also GAO‑22‑105136.

[21]Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services, 2023 Focus Group Report (2023). The committee collected qualitative and quantitative data during visits to eight military installations representing four of the five branches of the armed services, excluding Space Force. The committee addressed recruitment and retention, physical fitness and body composition assessments, and pregnancy and gender discrimination in the focus groups.

[22]In the private sector, TRICARE beneficiaries can receive care from civilian providers that may be part of a TRICARE provider network employed by regional contractors or may be an authorized non-network provider.

[23]Throughout this report, we use the term “provider” to refer to clinicians, providers, nurses, or other support staff who may conduct perinatal mental health screening.

[24]See 10 U.S.C. § 1074 and 32 C.F.R. § 199.17(d)(1) (2024).

[25]See Defense Health Agency, DHA Practice Recommendation: Behavioral Health Screening and Referral in Pregnancy and Postpartum, version 1 (2022).

[26]DHA does not require providers to have specific training or specialty certification particular to perinatal mental health, according to agency officials. All providers will have completed some type of formal curriculum in perinatal care when getting their original credentialing, which may have included mental health care, but there is no standard training or core curriculum upon hiring at DHA, according to these officials. General specialty training or residency requirements may or may not include training related to perinatal mental health.

[27]The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening for depression and anxiety at least three times during the perinatal period using standardized, validated instruments. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for depression in the adult population, including for pregnant and postpartum populations. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations do not specify how often providers should screen patients or which tools to use for screening.

[28]See Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense, VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment and Management of Pregnancy (2023).

[29]The EPDS is validated by researchers for use in screening symptoms of probable depression and probable anxiety in the perinatal population. The PHQ-9 is not specific to the perinatal population but has been validated by researchers for use in this population. It is validated for use in screening symptoms of depression but not for anxiety.

[30]See Defense Health Agency, DHA Practice Recommendation: Behavioral Health Screening and Referral in Pregnancy and Postpartum, version 1 (2022).

[31]According to DHA officials, the patient’s response to questions related to suicidal thoughts and self-harm can automatically indicate the need for a discussion as well.

[32]According to DOD, a high screening score alone is not a mental health diagnosis but can help provide early identification of those most at risk.

[33]In this report, we noted that the most common type of prescription medication dispensed for perinatal mental health conditions was antidepressants. See GAO‑22‑105136.

[34]We reviewed a random sample of medical records for 291 service members who delivered through direct care at military medical treatment facilities in fiscal year 2022. Our confidence in the precision of the sample’s results is at the 95 percent confidence interval. This is the interval that would contain the actual population value for 95 percent of the samples that could have been drawn. Overall percentage estimates have margins of error at the 95 percent confidence level within plus or minus 6 percentage points, and we note that they are estimates. If a percentage or data point is not generalizable, we note it is specific to the sample reviewed.

[35]While perinatal mental health screenings can occur in any care setting, within our sample, 68 percent of the screenings we identified took place in obstetrics and gynecology settings, and 13 percent took place in mental health settings. In our sample, DHA obstetrics and gynecology providers typically used the EPDS to screen (84 percent of screenings in this setting). In our sample, DHA mental health providers typically used the PHQ-9 screening tool (93 percent of screenings in this setting).

[36]The PHQ-2 is not identified in DHA’s recommendations as a tool validated specifically for use in the perinatal population; however, DHA policy requires the use of the PHQ-2 screening tool at all primary care visits for service members. We counted any EPDS, PHQ-9, or PHQ-2 screening in the perinatal period that met one of DHA’s recommended screening intervals in our medical record review, as DHA officials told us that any direct care provider could conduct a perinatal mental health screening. Some of these PHQ-2 screenings likely occurred at appointments that were not focused on perinatal health, such as physical therapy appointments. See Defense Health Agency, Standardization of Depression and Suicide Risk Screening in Primary Care During and Subsequent to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic, Administrative Instruction Number 6025.04 (2022).

[37]Researchers found lower sensitivity with this population when a PHQ-2 score of greater than or equal to 3 was used to indicate potential depression. The sensitivity improved with a lower score. The clinical guidance that direct care providers who are not in an obstetrics setting may follow—VA and DOD’s clinical practice guidelines related to the management of major depressive disorder—uses a score of greater than or equal to 3 to recommend further assessment.

See, for example, Antonella Gigantesco et al., “A Brief Depression Screening Tool for Perinatal Clinical Practice: The Performance of the PHQ-2 Compared with the PHQ-9,” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, vol. 67, no. 5 (2022), DOI: 10.1111/jmwh.13389 and Valarie Slavin, Debra K. Creedy, and Jenny Gamble, “Comparison of Screening Accuracy of the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 Using Two Case-Identification Methods During Pregnancy and Postpartum,” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, vol. 20, no. 211 (2020), DOI: 10.1186/s12884-020-02891-2. For the related guidance, see VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Major Depressive Disorder, version 4 (revised 2022).

[38]According to DHA officials, they rely on providers to remain current in their professional responsibilities and cannot prescribe how providers conduct their clinical practice.

[39]When we included PHQ-2 screenings—which are not listed as a validated tool in DHA’s recommendations—we found higher rates of screening at each of the recommended screening intervals. An estimated 94 percent of service members were screened using any tool at their first obstetrical appointment, followed by an estimated 89 percent of service members at their 28-week visit, and an estimated 80 percent of service members at their initial postpartum visit.

While we did not systematically assess the timeliness of prenatal care, we identified six service members who were late to care or did not have a documented direct care visit until more than 16 weeks after the estimated start of their pregnancy. We considered these a missed screening because there was not documentation that the service member was screened during the first trimester of their pregnancy.

[40]We considered a postpartum visit to be the initial postpartum visit if it occurred up to 13 weeks after the date of delivery. We determined that a service member did not attend an initial postpartum visit if we could not locate documentation of a postpartum-focused visit that fell within the 13-week period. We excluded from our sample any service members who did not have documentation of care within the year after delivery, indicating that they may have left the military or were no longer receiving care from direct care providers.

[41]National Institute of Mental Health, Perinatal Depression, NIH Publication No. 23-MH-8116 (revised 2023). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/perinatal-depression.

[42]Missed postpartum visits do not align with DHA’s recommendations for postpartum care. These recommendations, which mirror those of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, call for a comprehensive postpartum visit within 12 weeks postpartum that includes a full assessment of physical, social, and psychological well-being. Defense Health Agency, DHA Practice Recommendation: Optimizing Postpartum Care (2022) and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing Postpartum Care (Replaces Committee Opinion Number 666, June 2016. Reaffirmed 2021), (Washington, D.C.: May 2018, reaffirmed 2021).

DHA recommendations also state that service members should have contact with an obstetrics health care provider within the first 3 weeks postpartum. This should be tailored to meet the needs of the parent and infant and may include topics such as physical recovery, wound healing, mood and mental well-being, breastfeeding and infant nutrition, social support, and ongoing or chronic medical problems.